The combination between visualization nanozyme and tumor vascular normalization contributes to the therapy of breast cancer.

Abstract

Nanozymes as artificial enzymes that mimicked natural enzyme–like activities have received great attention in cancer therapy. However, it remains a great challenge to design nanozymes that precisely exert its activity in tumor without producing off-target toxicity to surrounding normal tissues. Here, we report a synergetic enhancement strategy through the combination between nanozyme and tumor vascular normalization to destruct tumors, which was based on tumor microenvironment (TME) “unlocking.” This nanozyme that we developed not only has photothermal properties but also can produce reactive oxygen species efficiently under the stimulation of TME. Moreover, this nanozyme also showed remarkable imaging performance in fluorescence imaging in the second near-infrared region and magnetic resonance imaging for visualization tracing in vivo. The process of combination therapy showed remarkable therapeutic effect for breast cancer. This study provides a therapeutic strategy by the cooperation between multifunctional nanozyme and tumor vascular normalization for intensive combination therapy of breast cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most frequent malignancy in women worldwide and is a heterogeneous disease on the molecular level (1). The heterogeneity of breast cancer tissue usually makes it easy to cause multidrug resistance of tumor, tumor recurrence, or metastasis, which leads to the decline of therapeutic effect (2). The principal reason is that there are differences from genotype to phenotype in the same tumor, resulting in different sensitivity, growth speed, invasion ability, prognosis, and other aspects of tumor cells to drugs (3–5). A more accurate combination therapy based on tumor heterogeneity could give full play to the maximum effect, produce minimum side effects, and avoid the occurrence of multidrug resistance (6–8). Recently, combination therapy has been extremely advocated in clinical application. For instance, the simultaneous administration of two or multiple therapeutic agents would modulate different signaling pathways involved in the tumor progression (9, 10), bringing many advantages including synergetic responses, reduced drug resistance, and mitigatory side effects. Therefore, it is of great significance to develop a multimode tumor cooperative therapy system to improve the therapeutic effect of breast cancer.

In the early 1970s, as a young surgeon who frequently encountered cancer in patients, Judah Folkman observed that tumor tissue was enriched by an extraordinarily high number of blood vessels that were fragile and often hemorrhagic (11, 12). The angiogenesis translational research started at that time and has lasted for nearly 50 years. At present, the results show that blocking angiogenesis can retard tumor growth, but it may also increase metastasis paradoxically (13, 14). This issue may be solved by vessel normalization, including increasing pericyte coverage, improving tumor vessel perfusion, reducing the permeability of blood vessels, and mitigating hypoxia consequently (15). Therefore, the normalization of tumor blood vessels is closely related to the regulation of tumor microenvironment (TME). Both humanized monoclonal antibody bevacizumab as the first anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents and plasmid expressing interfering RNA targeting VEGF (shVEGF) have been used in cancer therapy (16). In 2017, Zhang elucidated an unexpected role of T helper 1 (TH1) cells in vasculature and immune reprogramming. This finding confirmed that tumor blood vessels and immune system can affect each other’s functions and proposed that TH1 cells may be a marker and a determinant of both immune checkpoint blockade and anti-angiogenesis efficacy (15). Thus, the combined therapy with tumor vessel normalization is expected to improve the therapeutic effect of breast cancer.

Since Gao et al. (17) reported the first evidence of Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NPs) as peroxidase mimetics in 2007, various nanomaterials have been identified that have intrinsic enzyme-like activities (18, 19). Because of the similar enzymatic kinetics and mechanisms of natural enzymes under physiological conditions, this kind of nanomaterials is called “nanozyme” (20). The past decade have witnessed the rapid development of nanozymes in biomedical applications including immunoassays, biosensors, antibacterial, and antibiofilm agents (21, 22). Tailored to the specific TME, including the excessive production of acid and hydrogen peroxide, the introduction of highly active nanozyme, through Fenton and Fenton-like reactions to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), has been used in the chemodynamic therapy (CDT) of cancer (23). A great challenge for in vivo application of nanozyme is the precise control of the selective execution of the desired activity because off-target activity will lead to unpredictable side effects. For instance, Fe3O4 NPs have peroxidase-like activity to increase reactive ROS under acidic pH. However, these NPs exhibit catalase-like activity in neutral condition, which will lead to removal of ROS (24). In the process of ROS-related treatment, the former is beneficial to improve the therapeutic effect, while the latter should be inhibited. Therefore, it is necessary to design a strategy to coordinate the activity of nanozyme through the regulation of TME for optimal functioning upon entering of the nanozyme into its target cell.

As a proof of concept, we have constructed a previously unknown strategy to regulate TME by tumor vessel normalization to optimize the anticancer effect of visualizational nanozyme. Primarily, monodisperse core-shell Ag2S@Fe2C heterogeneous NPs were synthesized by seeded growth-based thermal decomposition method in organic phase. Afterward, to improve the tumor targeting, we designed a precise targeting NP-based nanozyme system (Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD) by coating a tumor-homing penetration peptide–modified Distearoyl phosphoethanolamine-PEG-iRGD peptide (DSPE-PEG-iRGD) on the surface of Ag2S@Fe2C NPs. This nanozyme showed remarkable intracellular uptake, good fluorescence performance, and up-regulation of ROS production in 4T1 cells. Furthermore, this nanozyme displayed high-resolution bioimaging effect in vivo in 4T1 breast cancer–bearing mice, which included fluorescence imaging in the second near-infrared region (NIR-II) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Moreover, the improved therapeutic effect was observed by the treatment of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD after combination with the tumor vascular normalization based on bevacizumab during the treatment in 4T1 breast cancer–bearing mice. Our study provides a new therapeutic strategy by the cooperation between catalysis of imaging-guided nanozyme and tumor vascular normalization for intensive combination therapy of breast cancer.

RESULTS

Synthesis and characterization

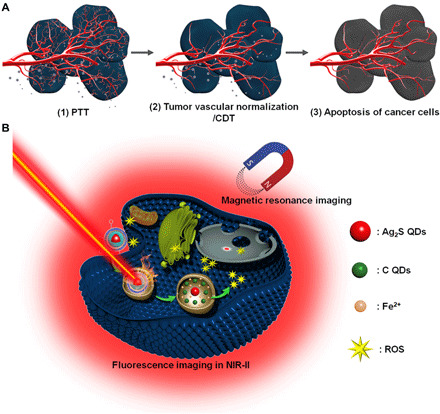

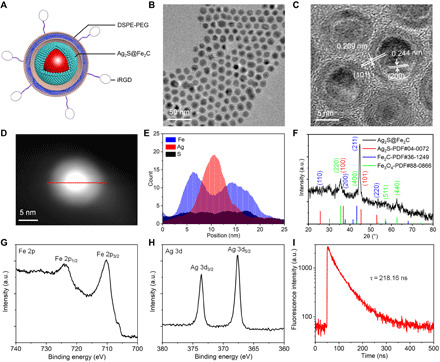

The scheme of the combination therapeutic strategy was shown in Fig. 1, including the schematic illustration of combination therapeutic strategy (Fig. 1A) and biochemical process for multifunctional Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD in breast cancer cell (Fig. 1B). Subsequently, the schematic design of core-shell Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD is presented in Fig. 2A. First, monodispersed Ag2S@Fe2C NPs were synthesized by seed-mediated growth method with thermal decomposition in organic phase. The synthesis of Ag2S@Fe2C NPs comprises two steps: (i) the preparation of Ag2S quantum dots (QDs) (fig. S1) and (ii) the iron carbide coating on the surface of Ag2S QDs to obtain Ag2S@Fe2C NPs (Fig. 2B). Ag2S QDs were prepared by thermal decomposition of a source precursor of Ag(DDTC) [(C2H5)2NCS2Ag]. (25). Fe2C phase around Ag2S QDs is regulated by ammonium bromide (NH4Br), which has been reported in our previous studies (26, 27). Because the selective adsorption of Br ions weakened the bonding between Fe and C atoms, the process could promote the formation of low-carbon iron carbide phase. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images in Fig. 2B have shown that Ag2S cores were semisurrounded by the Fe2C domains with a thickness of ~3 nm. The high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image depicted in Fig. 2C shows a lattice spacing between two (200) adjacent planes in Ag2S of 0.244 nm and distance of 0.209 nm corresponding to the (101) planes of hexagonal Fe2C. Furthermore, energy-dispersive x-ray (EDX) line scan of Ag2S@Fe2C NPs was shown in Fig. 2 (D and E), which has confirmed the composition and core-shell structure of Ag2S@Fe2C NPs. The results of x-ray diffraction (Fig. 2F) patterns were consistent with the characterization of TEM. However, the Fe2C shell was protected from further oxidization by a ∼1-nm Fe3O4 shell with a spacing of 2.97 Å between the (220) planes of magnetite. The x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) of Fe 2p (Fig. 2G and fig. S2) has confirmed the main existence of Fe0 in Ag2S@Fe2C NPs, and the weak satellite peaks are due to the local oxidation of NPs (26). The existence of Ag+ was confirmed by the XPS of Ag 3d (Fig. 2F and fig. S2). DSPE-PEG-iRGD was synthesized by covalent bonding between DSPE-PEG-NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) and tumor-homing penetration peptide iRGD (CRGDKGPDC) subsequently (fig. S3) (28). Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD were formulated using water/oil (W/O) emulsion method (29). The formation of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD nanozyme was confirmed by the Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (fig. S4). The red shift of the absorption peak for the stretching vibration of the C═O from carboxyl group (1635 cm−1) to amide bond (1689 cm−1) proves the amination of DSPE-PEG-NHS and iRGD (fig. S4, i and iv). The existence of vibration absorption peaks (3410 and 1480 cm−1) for N─H bond (fig. S4, iv) proved the obtaining of DSPE-PEG-iRGD. The hydrodynamic diameters of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD were 90.1 ± 20.3 nm (fig. S5A), and the zeta potential of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD was −12.2 mV (fig. S5B). The lifetime decays of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD (τ = 218.16 ns, λexcitation = 808 nm) were shown in Fig. 2I, which has proved that the NPs exhibit good luminescent property. The field-dependent magnetization curve of Ag2S@Fe2C NPs and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD was measured at room temperature. After the modification of DSPE-PEG-iRGD, the magnetic saturation value is reduced from 116.97 to 50.12 electromagnetic unit (emu) g−1 (fig. S5C). This result proves that Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD can be used as contrast agent in T2-MRI. Besides, better absorption capacity for light in the NIR was observed in Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD compared to Ag2S@Fe2C in fig. S5D.

Fig. 1. Scheme of the combination therapeutic strategy between visualization nanozyme and tumor vascular normalization for breast cancer.

(A) Schematic illustration of combination therapeutic strategy. (B) Schematic diagram of biochemical process for multifunctional Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD in breast cancer cell. PTT, photothermal therapy.

Fig. 2. Morphological and structural characterization.

(A) Schematic illustration of the designed Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD core-shell heterojunctions. (B) TEM image of Ag2S@Fe2C NPs. (C) HRTEM image of Ag2S@Fe2C NPs. (D and E) EDX line scan of Ag2S@Fe2C NPs: Fe (blue), Ag (red), and S (black). (F) X-ray diffraction patterns of Ag2S@Fe2C NPs. High-resolution XPS spectra of (G) Fe 2p and (H) Ag 3d obtained from Ag2S@Fe2C. (I) Lifetime decays of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD (λexcitation = 808 nm). a.u., arbitrary units.

Biodegradation and enzymatic activity of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG nanozyme in vitro

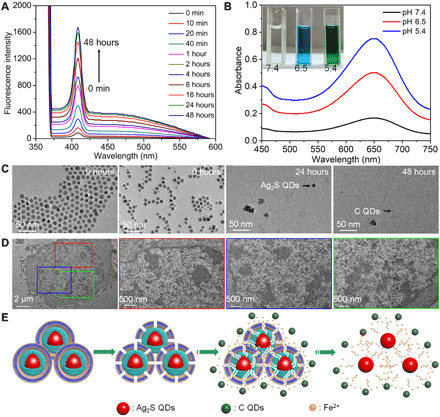

The biodegradation performance of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG was evaluated by time-dependent fluorescence spectra in 48 hours (Fig. 3A). With the prolongation of dispersion time of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (pH 5.4). The fluorescence intensity increases with time at the emission wavelength of 410 nm, which has demonstrated that carbon QDs (C QDs) are produced during the degradation of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG (30). The fluorescence spectra of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG were dispersed in PBS buffer (pH 7.4), and PBS buffer (pH 5.4) after 7 days further confirmed the stability of pH-dependent Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG in fig. S6A. Subsequently, the evaluation of peroxidase-like activity of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG with different pH values was shown in Fig. 3B and fig. S6B. The peroxidase-like activity increases with the decrease of pH value. Moreover, TEM images of the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG after degradation in PBS with pH value of 5.4 in 48 hours was revealed in Fig. 3C. After 6 hours, the NPs maintain the integrity generally with only slight morphological changes (arrow indicated). After 24 hours, degradation occurred in most of NPs from morphology and size. In addition, the free state of Ag2S QDs can be observed in the TEM image. After 48 hours, the morphology of the NPs is completely disrupted and residues of the C QDs can be observed (arrow indicated). Since C QDs and graphene oxide (GO) have a similar structure, the fluorescence property can be determined by the π states of the sp2 sites (31). Moreover, the samples that were obtained from Ag2S@Fe2C NP degradation in HCl solution (1 M) before and after 12 hours (fig. S7A) were characterized by XPS (fig. S7B). Normalized high-resolution XPS spectra of C 1s proved the existence of low-valence carbon. Moreover, as shown in fig. S7C, the carbon K edge spectrum of samples collected above shows a clear sp2 signal with energy loss peaks at 283 eV (1s → π*) and 293 eV (1s → σ*), which proved the existence of sp2-hybridized carbon in Ag2S@Fe2C NPs (32). Therefore, we can infer that these sp2-hybridized carbons were obtained during the thermal decomposition synthesis of Ag2S@Fe2C NPs. To further prove the above speculation, the biodegradation behavior and structural evolution of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG were further evaluated in 4T1 cells. After 24 hours of intracellular coincubation, Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG was almost degraded into ultrasmall NPs. These results were exhibited in bio-TEM images in Fig. 3D.

Fig. 3. Biodegradation performance.

(A) Time-dependent fluorescence spectra of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG dispersed in PBS buffer solution (pH 5.4, λexcitation = 370 nm, λEm = 410 nm). (B) Peroxidase-like activity of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG with different pH values (5.4, 6.5, and 7.4). Photo credit: Zhiyi Wang, Peking University, China. (C) TEM images (scale bars, 50 nm) of the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG after degradation in PBS (pH 5.4) for 0, 6, 24, and 48 hours. (D) Bio-TEM images (scale bar, 2 μm) of 4T1 cells incubated with Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG for 24 hours (scale bars, 500 nm) of different regions enlarged. (E) Schematic representation of the degradation process of the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG in the physiological environment.

On the basis of the above experimental results, Fig. 3E illustrated the degradation process of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG. The external DSPE-PEG degraded gradually because of hydrolysis of the ester linkage into segments (reduced molecular weight), oligomers and monomers, and lastly carbon dioxide and water (33) after the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG were dispersed in the physiological environment. Degradation of DSPE-PEG disrupts the NPs and triggers release of Fe2+ and C QDs from the Fe2C shell, which degrades rapidly if it is not protected by DSPE-PEG. After the degradation of Fe2C shell, Ag2S QDs were commonly found in bio-TEM images. Because the C QDs and Ag2S QDs are relatively stable in physiological environment, it is beneficial to be metabolized out of the body through the kidney and liver (34, 35). The unique biodegradability of the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG not only circumvents rapid degradation of the optical performance but also enables harmless clearance from the body in a reasonable period after the end of therapeutic functions in vivo.

Evaluation of enhanced cellular uptake, ROS-generation, and 4T1 cell killing ability

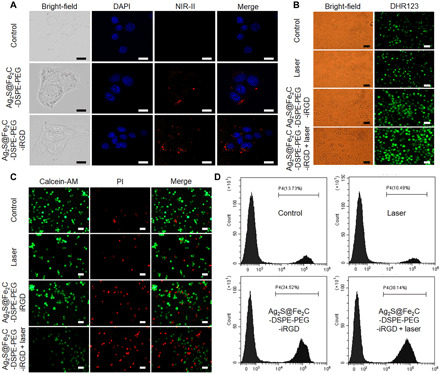

The modification by DSPE-PEG-iRGD enhanced the biocompatibility of NPs under physiological conditions, which was proved by cell counting kit-8 (CCK8) assay in fig. S8. The cellular uptake of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD in 4T1 cells was evaluated by multidimensional confocal microfluorescence imaging system in Fig. 4A (λexcitation = 808 nm). These results revealed that a minority of red fluorescence could be observed in 4T1 cells treated with Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG, indicating the limited cellular uptake. However, much stronger red fluorescence could be found after coincubation with Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD, which is mainly located in cytoplasm, instead of nuclei [staining by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), λexcitation = 405 nm]. These results suggested that the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD performed higher cellular uptake after the modification with tumor-homing penetration peptide iRGD.

Fig. 4. Cell experiments.

(A) Confocal laser scanning microscopy images (scale bars, 5 μm) of in 4T1 cells treated with saline, Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG, and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD in NIR-II. (B) Singlet oxygen generation evaluated by DHR123 in 4T1 cells treated with saline only, laser only, Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG, and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG + laser (scale bars, 50 μm). (C) Fluorescence images (scale bars, 100 μm) of the 4T1 cells stained with calcein-AM (live cells, green fluorescence) and PI (dead cells, red fluorescence) after incubation with saline only, laser only, Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG, and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG + laser. (D) Corresponding flow cytometry data of the 4T1 cells stained with PI (dead cells, red fluorescence) after incubation with saline only, laser only, Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG, and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG + laser.

Subsequently, we further evaluated the nanozyme activity of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD in cancer cells. Because nonfluorescent dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR123) can be oxidized by ROS into green fluorescent rhodamine 123, DHR123 was used as an intracellular ROS indicator (36). Fortunately, the strongest fluorescence intensity was shown in the group of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD under the irradiation of 808-nm laser, which demonstrated that the nanozyme activity of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD was also enhanced compared with other groups (Fig. 4B). In the previous study, we reported the evaluation method of photothermal efficiency of nanomaterials (27, 37, 38). These results in fig. S11 demonstrated that Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD is a highly efficient photothermal therapy agent. The 4T1 cell killing ability was evaluated in fluorescence micrographs in Fig. 4C [costained by calcein-AM and propidium iodide (PI)]. The group of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD under the irradiation of 808-nm laser showed the maximum range of dead cell markers, which proved that it has the strongest killing efficiency of 4T1 cells. Furthermore, corresponding flow cytometry data of the 4T1 cells stained with PI (dead cells, red fluorescence) was shown in Fig. 4D after incubation with saline only, the irradiation of 808-nm laser only, Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD, and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD under the irradiation of 808-nm laser. These results are consistent with above.

Biodistribution imaging and biocompatible in vivo

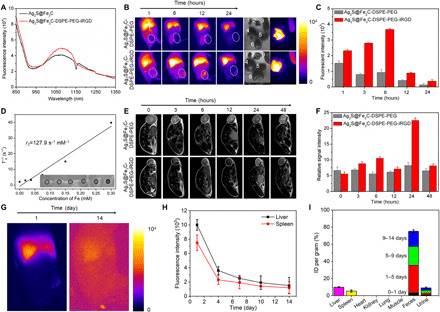

The fluorescent emission spectrum of Ag2S@Fe2C and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD in NIR-II was shown in Fig. 5A. Under the excitation of 808-nm laser, the fluorescent emission wavelength is 1071 nm. Subsequently, fluorescence imaging in NIR-II was carried out to track the in vivo behaviors of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD (20 mg kg−1, 200 ml) after intravenous injection into 4T1 breast cancer–bearing nude mice, with the excitation wavelength of 808 nm (Fig. 5B). The tumor site of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD group showed strong luminescence signals after 12 hours (Fig. 5C). In contrast, no obvious fluorescence signal appeared in the tumor site for Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG even after 24 hours. Moreover, the targeting capacity of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD was evaluated by ex vivo imaging of main organs (liver, spleen, lung, heart, and kidney) and tumors of mice after intravenous injection for 24 hours. Obvious fluorescence signals were clearly observed in the liver, tumor, and the main blood vessels near the tumor (Fig. 5B). The real-time movie of fluorescence imaging in NIR-II has been improved during the tail vein injection of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD (movie S1), which demonstrated that the nanozyme could achieve high-resolution microscopic imaging of blood vessels in mice, especially at the tumor site. These results reflect not only the advantages of fluorescence imaging in NIR-II with deeper tissue penetration but also the remarkable targeting effect of the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD for 4T1 breast cancer.

Fig. 5. In vivo imaging and evaluation of biocompatibility for rapid-excretable Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD.

(A) The fluorescent emission spectrum of Ag2S@Fe2C and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD in NIR-II under the excitation of 808-nm laser. (B) Real-time NIR-II fluorescence images of 4T1 breast cancer–bearing mice after intravenous injection of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD. Ex vivo fluorescence images of heart (i), kidney (ii), spleen (iii), liver (iv), lung (v), and tumor (vi), which were obtained at 48 hours after injection. Photo credit: Zhiyi Wang, Peking University, China. (C) The fluorescence intensities of the tumor after intravenous injection of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD, respectively. (D) T2 relaxation rate (1/T2) as a function of Fe concentration for the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD. (E) Real-time MRI of 4T1 breast cancer–bearing mice after intravenous injection of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD. (F) The relative MRI signal intensities changing at the tumor site after intravenous injection of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD, respectively. (G) The wide-field images show the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD luminescence signals in liver and spleen at 1 and 14 days. (H) The excretion of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD from mouse liver and spleen can be seen by plotting the signal intensity in these organs (normalized to liver signal observed at 1 day) as a function of time over 2 weeks. (I) Biodistribution of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD in main organs and feces of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD–treated mice at 14 days. Error bars, means ± SD (n = 3).

After calculation, the r2 value of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG was around 127.9 mM−1 s−1 when dispersed in water (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, we assessed the T2-weighted MRI capability in vivo after intravenous injection of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD (20 mg kg−1, 200 ml) into 4T1 breast cancer–bearing nude mice. Figure 5E clearly indicates that the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD show stronger signal intensity and make the tumor darker than Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG after 24 hours of injection. These results suggest higher accumulations of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD at the tumor sites owing to the active targeting by tumor-homing penetration peptide iRGD. Therefore, Ag2S@Fe2C NPs have the potential to be the agents for T2-weighted MRI.

The luminescence signal intensity in the main organs of mice, including liver and spleen, kept decreasing within the monitored time period of 14 days (Fig. 5, G and H). All the urine and feces excreted from mice were collected, and Ag was quantitatively detected by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry, revealing that ~90% of injected Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD was excreted from the body in 14 days (Fig. 5I). This rapid, high-degree excretion could promote clinical translation of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD.

Evaluation of tumor vascular normalization by bevacizumab

As mentioned before, angiogenesis as a physiologically complex process of proliferation and migration of endothelial cells could be suppressed by bevacizumab, which will benefit more for the tumor vascular normalization. We evaluated angiogenesis suppression effect of murine bevacizumab by fluorescence imaging in NIR-II and immunohistochemical analysis of CD31. Figure 6A showed the experimental diagram of 4T1 breast cancer angiogenesis by bevacizumab, which was imaged in NIR-II by intraperitoneal injection of low-dose Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD in 4T1 breast cancer–bearing mice. Comparing to the group of saline injection, tumor angiogenesis inhibition effect by bevacizumab was demonstrated in the tumor site in the first 10 days (Fig. 6, B and C, and fig. S10). Then, tumor grew rapidly. Furthermore, the real-time movie of fluorescence imaging in NIR-II was provided in 0 and 20 days for each group (movies S2 to S5). These results also proved that bevacizumab cannot be used as a single drug for tumor. Moreover, CD31 immunohistochemical staining of harvested 4T1 tumor after 20 days was shown in Fig. 6D. We can clearly observe that the tumor vascular density in bevacizumab injection group is notably less than the control group, which is consistent with fluorescence imaging results. Therefore, bevacizumab could influence the tumor vascular normalization of 4T1 breast cancer.

Fig. 6. Self-monitoring for inhibition of tumor angiogenesis.

(A) Schematic illustration of self-monitoring for inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD after intraperitoneal injection of saline and bevacizumab. (B) Real-time NIR-II fluorescence images of 4T1 breast cancer–bearing mice after intraperitoneal injection of normal saline and bevacizumab by Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD. (C) Representative photograph for volume change of tumor after intraperitoneal injection of normal saline and bevacizumab in 20 days. Inset: Corresponding harvested 4T1 breast cancer after 20 days. Photo credit: Zhiyi Wang, Peking University, China. (D) CD31 immunohistochemical staining of harvested 4T1 breast cancer after 20 days. Error bars, means ± SD (n = 5).

In vivo cancer therapy and biosafety evaluation

Combination therapy (i.e., photothermal therapy, CDT, and tumor vascular normalization) was investigated by treatment of 4T1 breast cancer–bearing mice in vivo. Figure 7A showed the schematic illustration of the therapy process. When laser irradiation is applied to Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD–injected mice, the local temperature of the tumor site rapidly increases from 37° to 54.7°C within 5 min, but for the mice treated with Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG, the temperature only reaches to 46.8°C (Fig. 7B and fig. S10A). These results confirmed the superior targeting capability of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD, which is consistent with the above results of bioimaging. Furthermore, the biodistribution of Ag after intravenous injection for 3 days was detected by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, which confirmed the targeting capacity of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD in vivo (fig. S10B). Comparing with other groups, the remarkable antitumor efficiency of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD was demonstrated by tumor volume with significant inhibition and elimination in vivo (Fig. 7, C and D, and fig. S10C). The growth status of representative nude mice in each group at the time interval of 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, and 30 days throughout the treatment period was observed (Fig. 7C and fig. S10D). The tumor of harvested mice injected with Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD and bevacizumab under the laser irradiation (808 nm, 0.3 W cm−2) was completely eradicated after treatment. An obvious damage was evidenced to the tumor cells of mice by cell necrosis and apoptosis in the group of injection with Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD and bevacizumab after laser irradiation. Mice treated with other groups showed less necrotic areas (Fig. 7E). These results showed that Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD was an efficient nanozyme as targeting nanomaterials with antitumor capacity in 4T1 breast cancer–bearing mice.

Fig. 7. Evaluation of combination therapy effect.

(A) Schematic illustration of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD nanocapsule-based tumor therapy. (B) Real-time thermal infrared images of 4T1 breast cancer–bearing mice after intravenous injection of saline, Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG + laser, Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG + laser + bevacizumab, Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD + laser, and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD + laser + bevacizumab under 808-nm laser irradiation (0.3 W cm−2, 5 min). (C) Representative photograph for volume change of tumor in the different treatments in 30 days. Photo credit: Zhiyi Wang, Peking University, China. (D) Volume change of tumor in the different treatments. (E) H&E-stained images of tumor regions with different treatments. Error bars, means ± SD (n = 5), unpaired t test.

Subsequently, toxicity analysis of these NPs was investigated in vivo. There was no decrease in the weight of the mice in each group during the treatment, which demonstrates the low toxicity of the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD (fig. S10C). The histological analysis was done by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the main organs after the treatment to study the damage in acute and chronic stages. No tissue necrosis was observed in the main organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) for the seven groups (fig. S12), demonstrating that the Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD have no significant side effects in vivo.

DISCUSSION

The complicated TME has brought great challenge to the therapeutic effect of nanomedicine for a long time. As mentioned above, it is almost impossible for specific nanoagents to penetrate the tumor through targeted effect to achieve effective accumulation and cell uptake and then excrete through metabolism after treatment. To overcome the multiple biological barriers during the drug delivery, nanomedicine should be rationally designed. In this work, a precise targeting NP-based nanozyme system (Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD) was developed for theranostics of breast cancer. At the cellular level, the nanozyme showed the efficient capacity of cell uptake and ROS production. In addition, this nanozyme has developed prominent luminescence in NIR-II and MRI contrast properties, which will be helpful to the visual tracking in vivo. As a result, the improved therapeutic effect was observed by the treatment of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD after combination with the tumor vascular normalization based on bevacizumab during the treatment in 4T1 breast cancer–bearing mice. Furthermore, ~90% of injected Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD was excreted from the body in 14 days. This rapid, high-degree excretion could promote clinical translation of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD. Hence, this study presents a new therapeutic strategy by the cooperation between catalysis of smart nanozyme system and tumor vascular normalization for intensive combination therapy of breast cancer, which would accelerate exploitation and clinical translation of nanomedicine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of monodisperse Ag2S@Fe2C NPs

Ag2S@Fe2C NPs were synthesized by a facile seed-mediated growth method. First, Ag2S QDs were synthesized following our previously reported method. In the typical synthesis, Ag2S QDs (10 mg liter−1 in hexane, 1 ml), 1-octadecene (ODE) (62.5 mmol), NH4Br (0.1 mmol), and Oleamine (OAm) (1 mmol) were mixed under a gentle N2 flow for 30 min in a four-necked flask. Then, the solution was heated to 120°C and kept for 30 min to remove the organic impurities. Fe(CO)5 (5 mmol) was injected into the reaction system when the temperature reached 180°C and kept for 10 min, and the system was raised up to 300°C for another 30 min. After the system cooled down to room temperature, 27 ml of acetone was added to the system. After centrifugation, the product was washed by ethanol and hexane.

Synthesis of Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG and Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD

Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG was formulated using W/O emulsion method. Typically, DSPE-PEG-NH2 (250.0 mg, 0.05 mmol) was dissolved in 12 ml of deionized water. Subsequently, Ag2S@Fe2C NPs (10 mg ml−1 in dichloromethane, 3 ml) was added to the system. Then, the mixed system was kept for 10 min by using ultrasound. The organic solvent in the obtained W/O emulsion was evaporated using a rotary evaporator at 25°C for 2 hours. Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG was obtained after centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 min. This synthesized Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG was dispersed in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) for further use. Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD was synthesized by using the same method as Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG; the only difference was the addition of DSPE-PEG-iRGD.

In vitro photothermal ablation of 4T1 cells

The cell LIVE/DEAD assays were also studied to investigate photothermal therapy in vitro. The 4T1 cells grown to 80% confluence in glass bottom 24-well plate were incubated with Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG for 4 hours, respectively. After washing the free NPs with Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS), fresh culture medium was added. Laser (808 nm, 0.3 W cm−2) was used to irradiate the adherent cell solution. After the Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium was removed, the cells were washed with PBS three times. Calcein-AM (100 μl) and PI solution (100 μl) were incubated with 4T1 cells for 15 min. Living cells were stained with calcein-AM (green fluorescence), and dead cells were stained with PI (red fluorescence) solution. The cells were then visualized using an inverted microscope (Olympus IX71) with a 10× under laser excitation at 475 and 542 nm.

In vivo antitumor efficiency evaluation

Mice bearing 200-mm3 4T1 breast cancer were randomly divided into nine groups: (i) Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD, laser irradiation, and bevacizumab; (ii) Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD and laser irradiation; (iii) Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG, laser irradiation, and bevacizumab; (iv) Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD and laser irradiation; (v) Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG-iRGD; (vi) Ag2S@Fe2C-DSPE-PEG; (vii) bevacizumab; (viii) laser irradiation only; and (ix) control (only saline). Nine mice were contained in each group. After 200 ml of saline or NPs (20 mg kg−1) were intravenously injected into nude mice bearing the 4T1 breast cancer for 24 hours, mice were exposed to 808-nm laser (0.3 W cm−2) for 5 min and tail vein–injected with bevacizumab. The changes of body weight and tumor volume during 30 days of treatment period were recorded.

Histological evaluation

Immunohistochemical was stained using anti-CD31 antibody, according to the corresponding protocols. Mice from each group were euthanized; then, major organs and tumor were recovered, followed by fixing with 10% neutral-buffered formalin after 18-day treatment. The organs were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 mm. H&E or Prussian blue staining was performed for histological examination. The slides were observed under an optical microscope.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical differences were determined by two-tailed Student’s t test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Ethical approval

All experiments involving animals were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Peking University, Beijing, China.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing Municipality (L72008), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51672010, 81421004, 51631001, 51590882, and 51602285), the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0206301 and 2016YFA0200102), the Key Laboratory of Biomedical Effects of Nanomaterials and Nanosafety, National Center for Nanoscience and Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (NSKF201607), and China Postdoctoral Science Fund (2019M660315). Author contributions: Z.W. and Y.H. conceived and designed the experiments. Z.W., Z.L., Z.S., S.L., S.Z., S.W., Q.R., and F.S. performed the experiments. Z.W. and Y.H. analyzed the results. Z.W., Z.A., B.W., and Y.H. wrote and revised the manuscript. Z.W. and Y.H. supervised the entire project. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/48/eabc8733/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Harbeck N., Penault-Llorca F., Cortes J., Gnant M., Houssami N., Poortmans P., Ruddy K., Tsang J., Cardoso F., Breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 5, 66 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J., Lau S. K., Varma V. A., Moffitt R. A., Caldwell M., Liu T., Young A. N., Petros J. A., Osunkoya A. O., Krogstad T., Leyland-Jones B., Wang M. D., Nie S., Molecular mapping of tumor heterogeneity on clinical tissue specimens with multiplexed quantum dots. ACS Nano 4, 2755–2765 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Q., Cai J., Zheng Y., Tan Y., Wang Y., Zhang Z., Zheng C., Zhao Y., Liu C., An Y., Jiang C., Shi L., Kang C., Liu Y., NanoRNP overcomes tumor heterogeneity in cancer treatment. Nano Lett. 19, 7662–7672 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ling D., Park W., Park S.-j., Lu Y., Kim K., Hackett M. J., Kim B., Yim H., Jeon Y., Na K., Hyeon T., Multifunctional tumor pH-sensitive self-assembled nanoparticles for bimodal imaging and treatment of resistant heterogeneous tumors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 5647–5655 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma A., Lee M.-G., Won M., Koo S., Arambula J. F., Sessler J. L., Chi S.-G., Kim J. S., Targeting heterogeneous tumors using a multifunctional molecular prodrug. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 15611–15618 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melgar K., Walker M. M., Jones L. M., Bolanos L. C., Hueneman K., Wunderlich M., Jiang J.-K., Wilson K. M., Zhang X., Sutter P., Wang A., Xu X., Choi K., Tawa G., Lorimer D., Abendroth J., O’Brien E., Hoyt S. B., Berman E., Famulare C. A., Mulloy J. C., Levine R. L., Perentesis J. P., Thomas C. J., Starczynowskil D. T., Overcoming adaptive therapy resistance in AML by targeting immune response pathways. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaaw8828 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan W., Yung B., Huang P., Chen X., Nanotechnology for multimodal synergistic cancer therapy. Chem. Rev. 117, 13566–13638 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma Y., Zhang Y., Li X., Zhao Y., Li M., Jiang W., Tang X., Dou J., Lu L., Wang F., Wang Y., Near-infrared II phototherapy induces deep tissue immunogenic cell death and potentiates cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano 13, 11967–11980 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu L., Leng D., Cun D., Foged C., Yang M., Advances in combination therapy of lung cancer: Rationales, delivery technologies and dosage regimens. J. Control. Release 260, 78–91 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Meel R., Sulheim E., Shi Y., Kiessling F., Mulder W. J. M., Lammers T., Smart cancer nanomedicine. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 1007–1017 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao Y., Arbiser J., D’Amato R. J., D’Amore P. A., Ingber D. E., Kerbel R., Klagsbrun M., Lim S., Moses M. A., Zetter B., Dvorak H., Langer R., Forty-year journey of angiogenesis translational research. Sci. Transl. Med. 3, 114rv3 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi O., Komaki R., Smith P. D., Jürgensmeier J. M., Ryan A., Bekele B. N., Wistuba I. I., Jacoby J. J., Korshunova M. V., Biernacka A., Erez B., Hosho K., Herbst R. S., O’Reilly M. S., Combined MEK and VEGFR inhibition in orthotopic human lung cancer models results in enhanced inhibition of tumor angiogenesis, growth, and metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 1641–1654 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebos J. M. L., Lee C. R., Cruz-Munoz W., Bjarnason G. A., Christensen J. G., Kerbell R. S., Accelerated metastasis after short-term treatment with a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 15, 232–239 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pàez-Ribes M., Allen E., Hudock J., Takeda T., Okuyama H., Viñals F., Inoue M., Bergers G., Hanahan D., Casanovas O., Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer Cell 15, 220–231 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian L., Goldstein A., Wang H., Lo H. C., Kim I. S., Welte T., Sheng K., Dobrolecki L. E., Zhang X., Putluri N., Phung T. L., Mani S. A., Stossi F., Sreekumar A., Mancini M. A., Decker W. K., Zong C., Lewis M. T., Zhang X. H.-F., Mutual regulation of tumour vessel normalization and immunostimulatory reprogramming. Nature 544, 250–254 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang S., Shao K., Liu Y., Kuang Y., Li J., An S., Guo Y., Ma H., Jiang C., Tumor-targeting and microenvironment-responsive smart nanoparticles for combination therapy of antiangiogenesis and apoptosis. ACS Nano 7, 2860–2871 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao L. Z., Zhuang J., Nie L., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Gu N., Wang T., Feng J., Yang D., Perrett S., Yan X., Intrinsic peroxidase-like activity of ferromagnetic nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 577–583 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei H., Wang E. K., Nanomaterials with enzyme-like characteristics (nanozymes): Next-generation artificial enzymes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 6060–6093 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Y., Ren J., Qu X., Nano-gold as artificial enzymes: Hidden talents. Adv. Mater. 26, 4200–4217 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao L. Z., Yan X. Y., Nanozymes: An emerging field bridging nanotechnology and biology. Sci. China Life Sci. 59, 400–402 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X. Y., Hu Y. H., Wei H., Nanozymes in bionanotechnology: From sensing to therapeutics and beyond. Inorg. Chem. Front. 3, 41–60 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 22.He W., Warner W., Xia Q., Yin J.-j., Fu P. P., Enzyme-like activity of nanomaterials. J. Environ. Sci. Health C 32, 186–211 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang Z., Liu Y., He M., Bu W., Chemodynamic therapy: Tumour microenvironment-mediated Fenton and Fenton-like reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 946–956 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan K., Xi J., Fan L., Wang P., Zhu C., Tang Y., Xu X., Liang M., Jiang B., Yan X., Gao L., In vivo guiding nitrogen-doped carbon nanozyme for tumor catalytic therapy. Nat. Commun. 9, 1440 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du Y., Xu B., Fu T., Cai M., Li F., Zhang Y., Wang Q., Near-infrared photoluminescent Ag2S quantum dots from a single source precursor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1470–1471 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Z., Zhao T., Huang X., Chu X., Tang T., Ju Y., Wang Q., Hou Y., Gao S., Modulating the phases of iron carbide nanoparticles: From a perspective of interfering with the carbon penetration of Fe@Fe3O4 by selectively adsorbed halide ions. Chem. Sci. 8, 473–481 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ju Y., Zhang H., Yu J., Tong S., Tian N., Wang Z., Wang X., Su X., Chu X., Lin J., Ding Y., Li G., Sheng F., Hou Y., Monodisperse Au–Fe2C Janus nanoparticles: An attractive multifunctional material for triple-modal imaging-guided tumor photothermal therapy. ACS Nano 11, 9239–9248 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen L., Yu S., Wang H., Xu J., Liu C., Chong W. H., Chen H., General methodology of using oil-in-water and water-in-oil emulsions for coiling nanofilaments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 835–843 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Y.-P., Zhou B., Lin Y., Wang W., Fernando K. A. S., Pathak P., Meziani M. J., Harruff B. A., Wang X., Wang H., Luo P. G., Yang H., Kose M. E., Chen B., Veca L. M., Xie S.-Y., Quantum-sized carbon dots for bright and colorful photoluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 7756–7757 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avgoustakis K., Beletsi A., Panagi Z., Klepetsanis P., Karydas A. G., Ithakissios D. S., PLGA–mPEG nanoparticles of cisplatin: In vitro nanoparticle degradation, in vitro drug release and in vivo drug residence in blood properties. J. Control. Release 79, 123–135 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Semeniuk M., Yi Z., Poursorkhabi V., Tjong J., Jaffer S., Lu Z.-H., Sain M., Future perspectives and review on organic carbon dots in electronic applications. ACS Nano 13, 6224–6255 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egerton R. F., Whelan M. J., Electron energy loss spectra of diamond, graphite and amorphous carbon. J. Electron. Spectros. Relat. Phenomena 3, 232–236 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhong Y., Ma Z., Wang F., Wang X., Yang Y., Liu Y., Zhao X., Li J., Du H., Zhang M., Cui Q., Zhu S., Sun Q., Wan H., Tian Y., Liu Q., Wang W., Garcia K. C., Dai H., In vivo molecular imaging for immunotherapy using ultra-bright near-infrared-IIb rare-earth nanoparticles. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 1322–1331 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du B., Yu M., Zheng J., Transport and interactions of nanoparticles in the kidneys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 358–374 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J., Cho H. R., Jeon H., Kim D., Song C., Lee N., Choi S. H., Hyeon T., Continuous O2-evolving MnFe2O4 nanoparticle-anchored mesoporous silica nanoparticles for efficient photodynamic therapy in hypoxic cancer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10992–10995 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z., Ju Y., Tong S., Zhang H., Lin J., Wang B., Hou Y., Au3Cu tetrapod nanocrystals: Highly efficient and metabolizable multimodality imaging-guided NIR-II photothermal agents. Nanoscale Horiz. 3, 624–631 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z., Ju Y., Ali Z., Yin H., Sheng F., Lin J., Wang B., Hou Y., Near-infrared light and tumor microenvironment dual responsive size-switchable nanocapsules for multimodal tumor theranostics. Nat. Commun. 10, 4418 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Y., Chen Q., Li S., Ma W., Yao G., Ren F., Cai Z., Zhao P., Liao G., Xiong J., Yu Z., iRGD-mediated and enzyme-induced precise targeting and retention of gold nanoparticles for the enhanced imaging and treatment of breast cancer. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 14, 1396–1408 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y., Hong G., Zhang Y., Chen G., Li F., Dai H., Wang Q., Ag2S quantum dot: A bright and biocompatible fluorescent nanoprobe in the second near-infrared window. ACS Nano 6, 3695–3702 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/48/eabc8733/DC1