Abstract

The COVID19 pandemic has forced the world to be closed in a shell. It has affected large population worldwide, but studies regarding its effect on children very limited. The majority of the children, who may not be able to grasp the entire emergency, are at a bigger risk with other problems lurking behind the attack of SARS-CoV-2 virus. The risk of infection in children was 1.3%, 1.5%, and 1.7% of total confirmed COVID-19 cases in China, Italy and United States respectively which is less compared to 2003 epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), when 5–7% of the positive cases were children, with no deaths reported while another recent multinational multicentric study from Europe which included 582 PCR (polymerase chain reaction) confirmed children of 0–18 year of age, provide deeper and generalize incite about clinical effects of COVID19 infection in children. According to this study 25% children have some pre-existing illness and 8% required ICU (intensive care unit) admission with 0.69% case fatality among all infected children. Common risk factor for serious illness as per this study are younger age, male sex and pre-existing underlying chronic medical condition. However, we need to be more concerned about possible implications of indirect and parallel psychosocial and mental health damage due to closure of schools, being in confinement and lack of peer interaction due to COVID19 related lockdown and other containment measures. The effects can range from mood swings, depression, anxiety symptoms to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, while no meaningful impact on COVID19 related mortality reduction is evident with school closure measures. The objective of this paper is to look at both the positive & negative effects in children due to COVID19 related indirect effects following lockdown and other containment measures. There is a need to gear up in advance with psychological strategies to deal with it post the pandemic by involving all stakeholders (parents, teachers, paediatricians, psychologists, psychiatrists, psychiatric social workers, counsellors), proposing an integrated approach to help the children to overcome the pandemic aftermath.

Keywords: Children, COVID19 Pandemic, Mental Health, School Education, Nutrition

1. Introduction

Classified by WHO as a pandemic, COVID-19 the Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) has affected life of millions worldwide, but data on how it is affecting children is still evolving. Although clinical part following COVID19 infection of any child is taking care by all health care systems similar to adults and many recent studies reported that children (upto 18 years) are making 1–5% cases of total infected cases and out of them 25% have pre-existing chronic medical illness and 8% require intensive care admission (Castagnoli et al., 2020, Gudbjartsson, 2020, Götzinger et al., 2020 Sep). The case fatality rate reported as 0.69% of infected children.3 Common risk for serious clinical illness reported are younger age group, underlying chronic medical condition and male sex (Götzinger et al., 2020). In children the clinical presentation of COVID19 infection have varied presentation from asymptomatic spreader to very severe life threatening diseases like acute respiratory distress syndrome, multiorgan dysfunction syndrome and multisystem inflammatory Syndrome in children(MIS-C) (Gudbjartsson, 2020, Götzinger et al., 2020 Sep, Dong et al., 2020, Radia et al., 2020).

However, we need to be more concerned about possible implications of indirect and parallel psychosocial and mental health damage due to closure of schools, being in confinement and lack of peer interaction due to COVID19 (Mitigating the effects of the COVID-19, 2020). Due to emergency pandemic measures more than 50% of student population are unable to attend their schools and colleges (Viner et al., 2020 May, India, 2020). Xie et al and other reviewed the long term adverse effects of home confinement following school closure. (Xie et al., 2019) They highlighted various adverse effects on child’s physical and mental wellbeing like excessive use of electronic gadgets, disturbed sleep pattern, unhealthy diets resulting obesity, and poor stamina. Data on quarantine and other measures of isolation for children during earlier various disasters have supported increased risk of long term post-traumatic stress disorder. (Brooks, Webster, Smith et al., 2020, Singh et al., 2020, Röhr et al., 2020, Ribeiro et al., 2020, Saurabh and Ranjan, 2020 Jul, Liu et al., 2020 May, Xin et al., 2020, Tomori et al., 2020 May 26, Wang et al., 2020). Sprang and Silman in their study reported mean post-traumatic stress scores were four times higher in children who had been quarantined than in those who were not quarantined (Sprang and Silman, 2013).

Elementary School teachers from 16 schools post a major earthquake in Central Java, Indonesia in 2006 identified concerns in children even two years post the event. They reported behavioral problems, with negative school-based behaviors (e.g. lack of academic motivation) reported as the most common symptom. They also identified posttraumatic stress as being a common finding. (Siswa Widyatmoko et al., 2011)

Stressors such as quarantined for prolonged duration, fears of infection, loss of routine, frustration and boredom, inadequate information, lack of in-person contact with classmates, friends, and teachers, lack of personal space at home, and family financial loss can have even more problematic and enduring effects on children and adolescents. (Xie et al., 2019, Brooks, Webster, Smith et al., 2020, Hamadani et al., 2020, Fitzgerald et al., 2020 Sep, Jiao et al., 2020)

Children respond to stress in different ways most common of which include having difficulties in sleeping, bedwetting, stomach-aches and headaches, and being anxious, withdrawn, angry, clingy, or afraid to be left alone. (Beazley, 2020, Ramaswamy and Seshadri, 2020, Kar, 2009) Studies have also shown depressive & anxiety symptoms in children who were confined in the Wuhan province (India, 2020). Consistent with findings data from Bangladesh also reported large proportions of children suffering from mental health disturbances in their survey (Yeasmin et al., 2020).

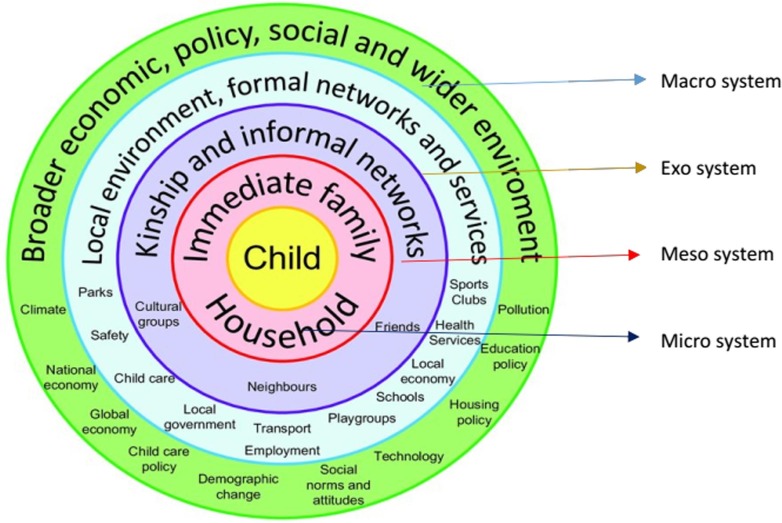

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory talks about the dependency of living creatures on their surroundings - the ecological systems and stresses on how human development is influenced by the different types of environmental systems. (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, Bandura, 1977) It explains the influence of the interaction between the inherent qualities of children & their environments on their growth & development. Urie discusses the effects of the four systems - microsystem; mesosystem, exosystem, and macro system and their interaction on a child’s development (Fig. 1 ). The more encouraging and nurturing these relationships and places are, the better the child can grow.

Fig. 1.

Bronfenbrenner's ecological model. Diagram by Joel Gibbs based on Bronfenbrenner’s (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) ecological model28,157 (Scott et al. 2016.P −7, used with permission).

It’s important to note here, that the most crucial supporting system, the microsystem, is intact for most children in times of this crisis which make it different from previous disasters and the effect this can have on development is a subject for research and early data can give us a plan to move ahead and act fast. (Sim and How, 2020 Jul, Liu and Doan, 2020 Sep, Chin et al., 2020)

Microsystem-Children & adults living in a joint family may have an advantage over those who are restricted to a nuclear family which provides lesser opportunities for them to interact. Confinement to home can also expose them to maltreatment and abuse in conflict-ridden families, the lockdown has also increased symptoms of depression and anxiety, and exposed more women to intimate partner violence, which can traumatize the child. (Hamadani et al., 2020, Marshan et al., 2016, COVID-19, xxxx, Fraser, 2020, Reidy, 2020)

There has been an increased risk of teenage pregnancy and child marriage for girls post pandemic as seen post previous disasters. (Hamadani et al., 2020, WHO, 2020, WORLD VISION, xxxx, UNESCO, xxxx, United Nations Children’s Fund, 2020, Plan International, 2020, Santos and Ghazy, 2020, Children, 2020)

For many children school environment provides an escape and a better environment for growth. Children of health care workers and other front-line workers spend prolonged periods uncared for, away from parents, which can lead to negative impact. These parents may behave harshly with their kids due to prolong COVID19 duty hours related mental stress and other mental health issues. (Ramaswamy and Seshadri, 2020, COVID-19, xxxx, UNICEF, xxxx, Dubey et al., 2020 Sep, India Today Coronavirus: doctor returns home, 2020, Pandey and Sharma, 2020, Spoorthy et al., 2020, Matsuo et al., 2020, Gupta and Sahoo, 2020, ThapaB and Chatterjee, 2020, Souadka et al., 2020, Stigma, 2020, The, 2020, Sahoo et al., 2020 Jun) These negative effects can be minimized by having balanced parenting, with both parents at home, sharing & caring during such crisis. A positive finding was reported by a study done in South Korea, they reported there was no change in the quality of relationships with spouses and children, approximately 20% of the sample reported a positive change in relationships with spouses and children indicating that there is hope to use the additional time amidst the lock down to strengthen the bond among family members. (Singh et al., 2020, Chin et al., 2020, Sahoo et al., 2020 Jun)

Social domain (Meso-System) - SARS-CoV-2 acts as an antisocial element as it has forced the family to shut itself indoors, instilling fear in the children and keeping their inborn yearning for human touch and affection from dear ones at bay. (Ramaswamy and Seshadri, 2020, Children among biggest victims of Covid-19 lockdown with multiple side-effects: Child Rights and You (CRY) report, 2020) Socialization, an important protective factor for emotional wellbeing, is being weakened when social distancing is propagated as the new norm. There is a need to emphasize physical distancing instead of social distancing to avoid emotional distancing and ensure learning social skills is not hampered. (Singh et al., 2020, Bandura, 1977, Dalton et al., 2020 May, Laor et al., 2005, Stark, xxxx, Cheng, 2020 Jul, Ribeiro et al., 2020, Saurabh et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2020 May, Xin et al., 2020, Tomori et al., 2020, Röhr et al., 2020) Those children who were tested positive and admitted in hospital responded better when they were allowed to interact with parents, caregivers through video calls. (Sahoo et al., 2020 Jun)

Cognitive/Emotional domain- Emotional development of any child depends upon the overall environment of the family, school, and society. Family members at home watching COVID19-related news leads to discussions creating excessive negativism and fear making them emotionally vulnerable and mental health issues. (Ramaswamy and Seshadri, 2020, Liu and Doan, 2020 Sep, COVID-19, xxxx, UNICEF, xxxx, Children among biggest victims of Covid-19 lockdown with multiple side-effects: Child Rights and You (CRY) report, 2020) Uncertainty about the reopening of school and normalization of life makes their mental agony worse. A child infected by SARS-CoV-2 and hospitalized or quarantined for a long time, with or without their family member, is affected adversely if it isn't taken care of appropriately by healthcare professionals. (Singh et al., 2020, Sahoo et al., 2020 Jun, Saurabh et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2020 May, Xin et al., 2020) For some children, where the adults teach them self-help skills and spend quality time with them, it results in boosting their cognitive development.

Due to lockdown, children start living in the virtual world which may lead to addiction in the worst scenario. The positive effects of using gadgets in some can lead to improved motor skills & cognitive skills aiding in keeping them occupied (a respite for parents), gamified learning, building competitive skills, and entertainment. (Sundus, 2018) Watching age-appropriate, high quality programming may promote certain cognitive benefits. “Co-viewing” (i.e. engaging in screen time with a parent or caregiver) can enhance infant attention and their propensity to learn from on-screen content. (Gottschalk, 2019)

However, we cannot turn a blind eye to the large negative impact it has, like speech & language delay, refractive errors, attention deficits, loss of interest in traditional teaching, academics, and social interaction. It can lead to a sedentary lifestyle, poor moral development, exposure to inappropriate content, and mental health issues. (Bento and Dias, 2017) Children may also be exposed to disinformation about COVID-19 that can spread virally and can cause them increased anxiety and fear, as children can have different interpretations of what makes a news outlet credible and reliable. (Children among biggest victims of Covid-19 lockdown with multiple side-effects: Child Rights and You (CRY) report, 2020, Livinsgtone, 2020, OECD, 2020) The sexual exploitation has seen an exponential increase. (Ramaswamy and Seshadri, 2020, Children among biggest victims of Covid-19 lockdown with multiple side-effects: Child Rights and You (CRY) report, 2020, Ecpat International, 2020, Wu et al., 2017 Nov 9, OECD, 2020) It’s advisable to set up parental supervision and a specific time for users to make optimal use of technology. (Bento and Dias, 2017) It is better to serve as a good model for children by staying without gadgets and showing their limited use for necessary things.

Physical domain (Exo-system) - The role of outdoor activities is important for the physical growth & mental wellbeing of any child. The restriction on this and closure of school leads to a sedentary lifestyle, irregular sleep patterns, less favourable diets, and excessive gadget use thereby hampering their physical & mental growth and making them prone to weight gain, obesity, poor stamina, and bony weakness. (Xie et al., 2019, Bento and Dias, 2017, Wu et al., 2017 Nov 9, Rundle, et al., 2020) It can be minimized if children play outdoor games in the garden and if physical activity is innovatively introduced as simple games at home and on the rooftop. (Indoor play ideas, xxxx)

Nutrition and Food - Many poor children get part of their food and nutrition through midday meals at schools and from Anganwadi centres. More than 35 crore school students have deprived of basic supply of food through schools due to complete lockdown in various countries. (Mitigating the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on food and nutrition of school children, 2020, COVID-19, xxxx, UNICEF, xxxx, Management, 2020, Futures of 370 million children in jeopardy as school closures deprive them of school meals – UNICEF and WFP, 2020) Pandemic-related restriction leads to the loss of their parent’s livelihood. (Cheng, 2020 Jul, Van Lancker and Parolin, 2020, Nicola, xxxx, Golberstein et al., 2019a, Farmer, 2020) Thus, their minimum basic needs are unfulfilled, worsening their nutritional status. India already suffers from malnutrition making children more prone to infection like tuberculosis, measles, and COVID19 itself, leading to increased preventable mortality and morbidity. (Children among biggest victims of Covid-19 lockdown with multiple side-effects: Child Rights and You (CRY) report, 2020, Management, 2020, Futures of 370 million children in jeopardy as school closures deprive them of school meals – UNICEF and WFP, 2020, Roelen, 2020)

Vaccination and other health problems - Hunger, malnutrition, pneumonia and other health-related shocks and stresses compound vulnerability to the virus and contribute to a vicious cycle of disease, destitution and death.(Children among biggest victims of Covid-19 lockdown with multiple side-effects: Child Rights and You (CRY) report, 2020, Roelen, 2020, Bramer et al., 2020 May 22, Olorunsaiye et al., 2020, Graham et al., 2020) Near-complete diversion of the public health care system and complete/partial closure of private health facilities,(Bramer et al., 2020 May 22, Graham et al., 2020, Enyama et al., 2020) leads to ignoring routine immunization and chronic ailment care for children paving way for increased risk & suffering due to common health problems and chronic health ailments leading to overall increased morbidity and mortality of children. (Children among biggest victims of Covid-19 lockdown with multiple side-effects: Child Rights and You (CRY) report, 2020, Bramer et al., 2020 May 22, Olorunsaiye et al., 2020, Graham et al., 2020, Enyama et al., 2020, More than 117 million, xxxx, Babu et al., 2020 Aug, McDonald et al., 2020 May, Hungerford and Cunliffe, 2020) It’s even more challenging for developing countries having compromised public health systems, making it unfavourable for paediatricians. Restriction of school and public gatherings prevent children from acquiring natural immunity against common childhood infections leaving them vulnerable to more severe illness, complications and even death in adulthood. (More than 117 million, xxxx, Djuardi et al., 2011) The government must consult concerned authorities to provide sufficient nutrition & necessary vaccinations as it may become a bigger problem after the pandemic. (Graham et al., 2020, More than 117 million, xxxx, Hungerford and Cunliffe, 2020) The pandemic will leave behind increased awareness about precautionary hygiene such as handwashing in children helping them in the long-run.

Educational domain (Exo-System) - Due to emergency pandemic control measures by various governments forced more than 1.5 billion children to stay at home. (India, 2020, Van Lancker and Parolin, 2020, Adverse consequences of school closures, xxxx) India declared complete lockdown with indefinite closure of all education on 16 March. Children lose the opportunity to learn new things from their peers and teachers at school. Though the compensatory online education platforms have been initiated in some government schools as well, a large majority of children from disadvantageous backgrounds are excluded further widening the gap in academic achievement. (India, 2020, Children among biggest victims of Covid-19 lockdown with multiple side-effects: Child Rights and You (CRY) report, 2020, Djuardi et al., 2011, Adverse consequences of school closures, xxxx, Van Lancker and Parolin, 2020, Nicola, xxxx, Golberstein et al., 2019a) Though its benefit can’t be denied, online teaching lacks the warmth of interactive teaching making it especially difficult for children below grade III who need excessive stimulation. Also undeniable, is the anxiety the board and competitive examination-takers are in due to prolonged uncertainty. The centre has allowed for states to decide re-opening of schools post October in some states & post November 17th for 9th & 10th grade in some states but the outcome this will generate is uncertain as was reported in Israel, when schools reopened in June it became highest place for infection. Other countries like Germany, Norway have adopted a ‘cohort model’ which has been quite hopeful, in which students arrive at different times limiting interaction. (IASC, xxxx, World Bank, xxxx, Johansen et al., 2020, Academy, 2020, Measures to maintain regular, xxxx)

Macrosystem - Due to the financial crisis resulting from the pandemic, livelihoods have been lost, emergency savings consumed and loans borrowed to meet basic requirements leading to an excessive financial burden on earning family member. Growing up in poorer neighbourhoods increases the risk of catching the virus and be a carrier, experience underlying health issues and reduced coverage of vaccination among children. It also affects access to a range of necessities such as good nutrition, quality housing, sanitation issues, space to play or study, and opportunities to engage in on-line schooling. (OECD, 2020, Van Lancker and Parolin, 2020, Nicola, xxxx, Golberstein et al., 2019a)

A higher level of poverty following any crisis significantly increases the risk of child marriage and teenage pregnancies especially in low income countries. (Marshan et al., 2016, Cas et al., 2014 Apr Apr; Indonesia and UNICEF. (2016). Kemajuan yang Tertunda: Analisis Data Perkawinan Usia Anak di Indonesia [Progress on pause: Analysis of child marriage data in Indonesia].Jakarta: Statistics Indonesia. Group, U, 2020) There may be an increase in child trafficking and pornography. (Children among biggest victims of Covid-19 lockdown with multiple side-effects: Child Rights and You (CRY) report, 2020, Ecpat International, 2020) The total effect of the COVID-19 pandemic is projected to result in 13 million additional child marriages.(Fraser, 2020, WORLD VISION, xxxx, UNESCO, xxxx, Plan International, 2020, Santos and Ghazy, 2020, UNPFA, 2020, CARE, COVID-19’s gender implications examined in policy brief from CARE, 2020, Golberstein et al., 2019b)Prior studies suggest that experiencing mass disasters and economic recession are associated with increased risk for mental health disorders.(Brewin et al., 2010)

The trend of increased domestic abuse, intimate partner violence is particularly worrisome in this context. Domestic violence services and children’s helplines report increased levels of risk for vulnerable children and families. (Women’s Safety NSW, 2020; Women’s Safety NSW, 2020) Children observe the behaviour of models - individuals observed in society, parents, TV characters, peers, teachers etc. and imitate or model the people they perceive as similar to themselves in terms of behaviours, values, beliefs & attitudes. Children pay close attention to the models around and encode their behaviour, at a later time they may replicate it. (Indoor play ideas, xxxx) Reinforcement or punishment that follows decides on the continuity of the behaviour. Parents worried about handling their children’s anxiety could play good role models for them to observe and process how the stress of lockdown and a family member being diagnosed is dealt with positively. Being optimistic and less worried was found to be one of the protective factors, from increased risk of depressive symptoms in students studied in Wuhan. (Xie et al., 2019) It would be burdensome and unrealistic to expect parents to be at their best behaviour in a crisis like this but parents must become aware of active–passive ways they influence the child around them. We stress it’s important to learn to manage one’s anxiety first & seek help when it’s difficult.

1.1. Looking for the vulnerable group

For those who may require some type of intervention, understanding risk factors can inform screening and tailoring of programs.(Goenjian et al., 2005 Dec, Holmes et al., 2020 Jun) In a systematic review it was discussed that the risk factors that appear strongest are severe exposure to the event (especially injury, threat to life, and extreme loss), living in a highly disrupted or traumatized community, little previous experience relevant to coping with the disaster, ethnic minority, poverty or low socioeconomic status, the presence of children in the home, psychiatric history, secondary stress, weak or deteriorating psychosocial resources, avoidance coping, and assignment of blame. Witnessing domestic violence, overcrowding, parental unemployment, exposure of substance misuse, influences of peers and school, degree of loss, being evacuated or displaced, separation from a primary caregiver, extent of post disaster stresses and adversities, frequency of exposure to trauma and loss reminders, and on-going exposure to media coverage. (Holmes et al., 2020 Jun, Hunt, 2019, Hale, 2020, Beazley, 2020, Kar, 2009, Goenjian et al., 2000 Jun, OECD, 2020)

For children with higher needs, disruption to schooling and respite care placements have the potential to push some families into crisis. The presence of a sibling with a disability in the home will compromise parents’ abilities to meet the new demands of home schooling for other children and to manage family stress. Many families lack guidance and information about available services and the types of assistance they are eligible for which is particularly problematic in a period of widespread confinement like homeless children, refugees, children in single-parent families. (Reidy, 2020, Hale, 2020, Beazley, 2020, OECD, 2020, OECD, 2020, Brackbill et al., 2009) Children of migrant workers, students due for board examinations.

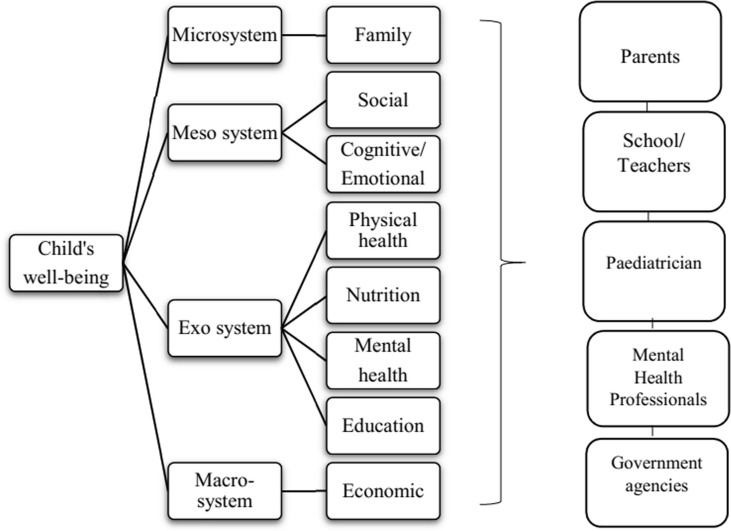

Although Chinese Health Commission issued some instructions about how to decrease psychological morbidities in children kept under quarantined, but these can’t fulfil the need of current scenario. We need more integrated planning (Fig. 2 ) to deal with this crisis.

Fig. 2.

Integrated approach involving all stakeholders.

1.2. Managing the crisis-

When caring for children & adolescent’s mental health in the aftermath of emergencies and disasters, it is important to appreciate the uniqueness of each event as the actions taken to identify and support affected children may vary based on the context. (Watson et al., 2011) In their review Watson et al,(Bryant et al., 2009) discuss certain principles to keep in mind while preparing for managing the aftermath. (a) promoting a sense of safety, (b) promoting calming, (c) promoting a sense of self-efficacy and community efficacy, (d) promoting connectedness, and (e) instilling hope. (Bisson et al., 2010, Everly and Flynn, 2006)

The aim of screening is to identify the most vulnerable children in the community, namely those at greatest risk of developing psychopathology. Most children exposed to traumatic events develop fleeting psychological responses, these are normal and are not psychiatric disorders, and children may worry about it. Hence in an initial phase of watchful waiting is recommended rather than immediate clinical involvement. Intervention to work at different levels.

There is a growing consensus that Psychological First Aid (PFA) a set of actions (contact and engagement with survivors, promoting safety and comfort, information-gathering on needs and concerns of survivors, practical assistance, information on normative psychological responses to traumatic experiences and on coping strategies, linking with available support), is the most appropriate first level intervention for children, adults, and families exhibiting distress or decrements in functioning in the acute aftermath of disasters and mass violence. It is delivered by trained non-health professionals to provide assistance to affected populations within days/ weeks after the event with the aim of reducing the initial distress and fostering adaptive functioning and coping. (Bisson et al., 2010, Everly and Flynn, 2006, McCabe et al., 2014, Disaster Mental Health Subcommittee, 2009, National Commission on Children and Disasters, 2010, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2018)

Second focus on the prevention of psychopathology in trauma-exposed children who have developed some psychiatric symptoms, through early detection and appropriate screening measures. (Meiser-Stedman et al., 2017)

Third level involves treatment of psychopathology; For example, treatment of children with PTSD with trauma-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy delivered by clinicians within 2–6 months after trauma reduced the likelihood of PTSD at follow-up, was found to be cost-effective. Cognitive-behavioural approaches for use among children and adolescents have received the most empirical support in improving child traumatic grief, PTSD, depression, and anxiety, suggesting that this intervention is acceptable and efficacious for this population. (Shearer et al., 2018, Brymer et al., 2009, Silverman et al., 2008, Cohen et al., 2006, Danese et al., 2019, Ali et al., 2019)

Generally, after the aftermath of an event the intervention focus on short term needs but the mental health needs of children and families involved can be enduring and hence the plan should focus on long term needs. (Danese et al., 2019, Ali et al., 2019)

The evidence also highlights the need to work in multiple systems may include capacity building by providing family-based, trauma-informed trainings for current mental health

trainees who will be joining the workforce, and also for school based personnel, who serve as the primary point of service for mental health care for many children in the United States.(Danese et al., 2019, Ali et al., 2019) Studies have shown classroom-based psychosocial intervention show improvement in PTSD symptoms compared with controls and need for intervention to be catered in school to be effective.(Berger et al., 2007, Tol et al., 2008, Jaycox et al., 2010, Dayton et al., 2016) Similarly, provision of mental health services through primary care settings may also be considered.(Dayton et al., 2016) There is a need for designing interventions on the basis of need and available local resources; Staying updated on the evidence base regarding effective practices. Planning intermediate interventions that can be implemented by paraprofessionals focussing on problem solving skills, positive activity scheduling, managing reactions, promoting helpful thinking, and rebuilding healthy social connections, (National Commission on Children and Disasters, 2010, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2018, Meiser-Stedman et al., 2017, Forbes et al., 2010) this Psychological recovery programme was implemented and favourably received for its feasibility in countries like USA & Australia. (Fairbrother et al., 2004)

Research on service utilization indicates that the majority of individuals exposed to a terrorist attack or other disasters do not seek mental health care or use available services. Hence it is important that mental health professionals reach out to other service providers, including spiritual providers, school personnel first responders, public health and health professionals, and volunteers. (Goenjian et al., 2005 Dec, Jayasinghe and C, Difede, J., Spielman, L, A. & Robin, L, 2006, Public Health England, 2020)

In this view we propose an integrated model to work with (Fig. 2). Keeping the prior suggestions, we listed few recommendations for Parents, school authorities, Paediatricians, Mental health professionals and for Governmental agency. (Singh et al., 2020, Stark, xxxx, Bryant et al., 2009, National Commission on Children and Disasters, 2010, Brewin et al., 2010, Dalton et al., 2020, Blue, 2020, CDC, 2020, NHS, 2020, UNICEF. How to talk to your child about coronavirus disease, 2019, WHO, 2020)

Parents(Singh et al., 2020, Laor et al., 2005, Bryant et al., 2009, NHS, 2020, WHO, 2020)

Mitigating mental health problems and cushioning the social impacts of confinement for children and adolescents. Many countries and international organizations are taking steps to safeguard the mental wellbeing of children and young people during the COVID-19 outbreak, for example by issuing basic guidance for parents and carers on how to talk about the outbreak with their children in an age-appropriate way which lowers anxiety. (Liu et al., 2020 May, Dalton et al., 2020, Blue, 2020, CDC, 2020, NHS, 2020, UNICEF. How to talk to your child about coronavirus disease, 2019, WHO, 2020, Ruzek et al., 2004) Most guidance focuses on supporting children when they show stress or distress, to find positive ways to express their feelings, such as through playing or drawing, guidance on maintaining familiar routines, ways to maintain contact between children and carers if they are separated, and maintaining social contact with peers.

-

•

Providing assurance realistically, explaining the nature of the pandemic, assuring that its impermanence, discussing post-pandemic holiday plans/goals for later to instil hope in the child.

-

•

Engaging the child in recreational and physical activities, simple meditations; teaching them minor chores to feel more empowered; Leaving no room for helplessness or boredom.

-

•

Collaborating with teachers to keep them engaged academically and prevent losing touch and also motivation in the long run.

-

•

Adapting useful parenting strategies from friends/relatives

-

•

Trying to do as much as possible within their capacity and if the need arises not to hesitate to take professional help for their child & themselves

-

•

Especially taking care of oneself while dealing with specially-abled children

-

•

Discussing religious/spiritual stories for comfort and hope

-

•

Remembering the best way to instil hope & reduce fear is being a good role model as discussed above

School Authorities(Berger and Gelkopf, 2009, Berger et al., 2007, Tol et al., 2008, Jaycox et al., 2010)

School authorities & Teachers can play a major role in helping children deal with the trauma as discussed. It has been well documented that services for children need to take place in schools. Teachers can serve as an effective first-line resource for assessing the psychological state of children exposed to natural disasters. (Siswa Widyatmoko et al., 2011)

-

•

The school authorities need to revamp their mode of teaching, their curriculum to meet the needs of the current scenario.

-

•

The first responsibility would be taking care of the needs of the teachers, help them cope with their anxieties, reassuring them of their employment status, providing them required remuneration. As they serve as the bridge, in connecting students to school.

-

•

Having full-time psychologists in the school to manage the upheaval, schools have to deal with once it reopens.

-

•

It’s a must for every school to train their teachers in identifying children who may be suffering from depression, anxiety.

-

•

Equipping them with simple psychological techniques to deal with children, to ease their anxiety comfortably, like simple counselling techniques, relaxation exercises, art therapy, mindfulness training. Turning a blind eye towards it can have far-fetching ugly implications.

-

•

Extra training for teachers who can act as gate-keepers for the warning signs

-

•

Special interest in children who have special needs, increasing assistance to cover the widened gap

-

•

Looking at the high-risk vulnerable group more closely as discussed above.

-

•

Having a continuous liaison with parents & health authorities.

-

•

The importance of making mental health mandatory as part of the curriculum for children at all levels cannot be more stressed as not only it’s the need of the hour but will aid in making resilient adults for the future.

-

•

Need to talk with parents about how they are managing things during this crisis specifically parents of disadvantageous groups, students admitted under the right to education (RTE).

Paediatrician (Liu et al., 2020 May, Fairbrother et al., 2004, Jayasinghe and C, Difede, J., Spielman, L, A. & Robin, L, 2006, Brewin et al., 2010, Dalton et al., 2020)

Previous evidence highlights, psychologists need to work with multidisciplinary teams, lead it in providing training and consultation. By expanding their role beyond providing direct care, psychologists can expand access to care for those survivors who do not typically seek

or receive mental health services. There is need to train other health specialists. (Blue, 2020, NHS, 2020)

-

•

Any child with a health concern first comes in contact with a paediatrician, it’s important to have an SOP for every health centre on how to comprehensively manage the post-pandemic cyclone of psychological concerns.

-

•

Providing telephonic consultation or other consultations through other electronic media platforms to minimize their exposure to COVID19 infection. More so for children suffering from chronic health problems like haematological and solid malignancies, nephrotic and other chronic renal diseases, cystic fibrosis and other chronic respiratory disease and neurodevelopment disorders, etc.

-

•

Screening every child who comes for consultation for red flags

-

•

Get trained in administering, simple psychological assessments, identifying the psychological needs of the child and providing psychological first aid

Mental health professionals (Liu et al., 2020 May, Stark, xxxx, Bryant et al., 2009, Dayton et al., 2016, Berkowitz et al., 2010, Jayasinghe and C, Difede, J., Spielman, L, A. & Robin, L, 2006, Elhai et al., 2009, Blue, 2020)

-

•

The role of psychological intervention is immense & the most needed for everyone, more so for children, as some even have trouble comprehending the pandemic scenario

-

•

Psychologists, counsellors, Psychiatric social workers, NGO’s referring children needing pharmacological assistance to a psychiatrist

-

•

Need to start online services, modifying to suit it culturally, many cities have initiated helplines, planning more friendly ways to connect to children

-

•

Getting trained through online workshops to improve & upgrade their skills accordingly

-

•

Coming up with brief interventions not only for children seeking treatment but to make training programs for parents, teachers, paediatricians other health care people coming in touch with children

Policy options to strengthen food assistance(Liu et al., 2020 May, Laor et al., 2005, Public Health England, 2020, Dalton et al., 2020, NHS, 2020, UNICEF. How to talk to your child about coronavirus disease, 2019, Ruzek et al., 2004, Ruzek et al., 2008, Kichloo et al., 2020)

-

•

Every economy relies on its backbone for support and a strong government is most critical to mitigate the effects of any societal danger

-

•

Ensuring not only the safety of the citizens but also their basic rights to education, food, employment, decent living

-

•

Planning measures to curb violence towards women & children; associating with national and international level child-caring agencies like UNICEF, WHO

-

•

Support children’s access to the digital environment to make sure that no child is left behind.

-

•

Planning to cover the economic gap created & ways to cover it so it does not result in further damage

-

•

Provide grants for research on the psychological, social, economic and physical effects of the pandemic

1.3. The way forward

Although most children may not suffer deleterious psychological outcomes because of a temporary loss of access to these opportunities, the impact of prolonged uncertainty and lack of socialization, skill-based learning, social support, and reduced physical activity may increase children’s emotional distress and parenting challenges. There is a need to develop adequate methods for early identification of those at risk for long term problems. (Bryant et al., 2009)

As the target is to provide services to those who need it more, it’s become imperative to refine our screening for the early identification of those at risk for long-term problems, assessment, clinical evaluation and services. Further documenting the effectiveness and efficacy of acute, intermediate, and long-term mental health treatment interventions and especially in this context enhancing the understanding of delayed onset reactions and relapse

This unprecedented pandemic demands more solidarity, within local communities, national communities and medical & scientific research community. Mental health professionals must devote increased attention to the delivery of evidence-based interventions and evidence-informed services and work in liaison with other stake holders as discussed. Telemedicine has been initiated by various organisations at different levels; however its effectiveness needs to be evaluated. Need to take action by adopting the best practices already adopted by several governments to ensure children’s wellbeing both during the pandemic and after it ends. (Monaghesh and Hajizadeh, 2020, Andrews et al., 2020, Scott and Patricia, 2016)

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105754.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Critical Updates on COVID-19/Clinical Guidance/COVID-19 Planning Considerations:Guidance for School Re-entry. 2020 [last accessed 2020 Jun25]. Available from: https://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/covid-19-planning-considerations-return-to-in-person-education-in-schools.

- Adverse consequences of school closures. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/consequences.

- Ali, M. M., West, K., Teich, J. L., Lynch, S., Mutter, R., & Dubenitz, J. (2019). Utilization of mental health services in educational setting by adolescents in the United States. Journal of School Health, 89, 393–401.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/josh.12753. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Andrews E., Berghofer K., Long J., Prescott A., Caboral-Stevens M. Satisfaction with the use of telehealth during COVID-19: An integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2020.100008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu N., Kohli P., Mishra C., Sen S., Arthur D., Chhablani D. To evaluate the effect of COVID-19 pandemic and national lockdown on patient care at a tertiary-care ophthalmology institute. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2020;68(8):1540–1544. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1673_20. PMID: 32709770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. Social learning theory. [Google Scholar]

- Beazley H. Children’s Experiences of Disaster: A Case Study from Lombok, Indonesia. Natural Hazards and Disaster Justice. 2020:185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bento G., Dias G. The importance of outdoor play for young children's healthy development. Porto Biomed. J. 2017;2(5):157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pbj.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger. R., & Gelkopf. M. (2009). School-based intervention for the treatment of tsunami-related distress in children: A quasi-randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78, 364-371. doi:1O.I159/O<X)235976. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berger R., Pat-Horenczyk R., Gelkopf M. School-based intervention for prevention and treatment of elementary-students' terror-related distress in Israel: A quasi-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:541–551. doi: 10.1002/jts.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, S., Bryant, R., Brymer, M., Hamblen, J., Jacobs, A., Layne, C et al. (2010). Skills for Psychological Recovery: Field operations guide. Washington. DC:National Center for PTSD (U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs) and National Child Traumatic Stress Network (funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and jointly coordinated by the University of California. Los Angeles, and Duke University).

- Bisson, J. I., Tavakoly, B. Witteveen, A. B., Ajdukovic, D., Jehel, L. Johansen, V. A Olff. M. (2010). TENTS guidelines: Development of post-disaster psychosocial care guidelines through a Delphi process. British Journal of Psychiatry, 196, 69-74. doi:10.ll92/ bjp.bp. 109.066266. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Beyond Blue (2020), From toddlers to teens: How to talk about the coronavirus, https://coronavirus.beyondblue.org.au/i-am-supporting-others/children-and-young-people/from-toddlers-to-teens-how-to-talk-about-the-coronavirus.html (accessed on October 29, 2020).

- Brackbill R.M., Hadler J.L., DiGrande L., Ekenga C.C., Farfel M.R., Friedman S. Asthma and posttraumatic stress symptoms 5 to 6 years following exposure to the World Trade Center Terrorist Attack. JAMA. 2009;302(5):502–516. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramer C.A., Kimmins L.M., Swanson R., Kuo J., Vranesich P., Jacques-Carroll L.A. Decline in Child Vaccination Coverage During the COVID-19 Pandemic - Michigan Care Improvement Registry, May 2016-May 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020 May 22;69(20):630–631. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6920e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin, C. R. Fuchkan, N., Huntley, Z. Robertson. M., Thompson. M., Scragg, P Ehlers, A. (2010). Outreach and screening following the don bombings: Usage and outcomes. Psychological Medicine, 40. 2049-2057. doi:10.1017/S003329171(KX)0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brewin, C. R. Fuchkan, N., Huntley, Z. Robertson. M., Thompson. M., Scragg, P Ehlers, A. (2010). Outreach and screening following the 2005 London bombings: Usage and outcomes. Psychological Medicine,40. 2049-2057. doi:10.1017/S003329171(KX)0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1979. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al.The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020; published online Feb 19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bryant R.A., Litz B.T. Mental health treatments in the wake of disaster. In: Neria Y., Galea S., Norris F., editors. Mental health and disasters. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 321–335. [Google Scholar]

- Brymer, M. J., Steinberg, A. M. Vemberg, E. M., Layne. C. M. Watson, P. J. Jacobs, A Pynoos, R. S. (2009). Acute interventions for children and adolescents. In E. Foa, T. Keane, M. Friedman, & J. Cohen(Eds.), Effective treatments for PTSD (2nd ed., pp. 106-116 & 542-545). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- CARE, COVID-19’s gender implications examined in policy brief from CARE, 2020.

- Cas A.G., Frankenberg E., Suriastini W. The impact of parental death on child well- being: Evidence from the Indian Ocean tsunami. Demography. 2014;51(2):437–457. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagnoli R, Votto M, Licari A, et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. Published online April 22, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467. [DOI] [PubMed]

- CDC (2020), Coronavirus DIsease 2019 (COVID19) - Manage Anxiety & Stress, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prepare/managing-stress-anxiety.html.

- Cheng S.O. Xenophobia due to the coronavirus outbreak - A letter to the editor in response to “the socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review”. Int J Surg. 2020;79:13–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Children among biggest victims of Covid-19 lockdown with multiple side-effects: Child Rights and You (CRY) report. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/children-among-biggest-victims-of-covid-19-lockdown-with-multiple-side-effects-cry-report/story-6seNNglhflnQt6IAVV036K.html (accessed Oct1, 2020).

- End Violence Against Children. (2020). Protecting Children during the COVID-19 Outbreak. https://www.end-violence.org/protecting-children-during-covid-19-outbreak.

- Chin M., Miai Sung M., Seohee Son S. Changes in Family Life and Relationships during the COVID-19 Pandemic and their Associations with Perceived Stress. Fam. Environ. Res. 2020;58(3):447–461. doi: 10.6115/fer.2020.032. Published online 2020 Aug 20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino. A. P., & Staron, V, R. (2006). A pilot .study of modified cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood traumatic grief. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45. 1465-1473, doi:10.1097/01.chi,0000237705,43260,2c. [DOI] [PubMed]

- COVID-19: Children at heightened risk of abuse, neglect, exploitation and violence amidst intensifying containment measures. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/covid-19-children-heightened-risk-abuse-neglect-exploitation-and-violence-amidst.

- Dalton L., Rapa E., Stein A. Protecting the psychological health of children through effective communication about COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(5):346–347. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30097-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton L., Rapa E., Stein A. “Protecting the psychological health of children through effective communication about COVID-19”, The Lancet Child & Adolescent. Health. 2020;Vol. 0/0 doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30097-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A., Smith P., Chitsabesan P., Dubicka B. Child and adolescent mental health amidst emergencies and disasters. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2019 doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.244. published online Nov 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton L., Agosti J., Bernard-Pearl D., Earls M., Farinholt K., Groves B.M. Integrating mental and physical healthservices using a socio-emotional trauma lens. Current Problems inPediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 2016;46:391–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disaster Mental Health Subcommittee. (2009), Disaster mental health recommendations: Report of the Disaster Mental Health Subcommittee of the National Biodefense Science Board. Retrieved from http:www.phe.gov/Preparedness/legal/boards/nbsb/Documents/ nsbs-dmhreport- final.pdf.

- Djuardi Y., Wammes L.J., Supali T., Sartono E., Yazdanbakhsh M. Immunological footprint: The development of a child’s immune system in environments rich in microorganisms and parasites. Parasitology. 2011;138:1508–1518. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011000588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y., X. Mo and Y. Hu (2020), “Epidemiological characteristics of 2143 pediatric patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in China”, Journal: Pediatrics Citation, http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0702.

- Dubey S., Dubey M.J., Ghosh R., Chatterjee S. Children of frontline coronavirus disease-2019 warriors: Our observations. Journal of Pediatrics. 2020;224:188–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecpat International (2020), why children are at risk of sexual exploitation during covid-19, https://ecpat.exposure.co/covid19? fbclid=IwAR3Z7DgyDZ8NeKwfa N6fkB6zwXdFYnQ-Ouk5D8A55S-t_cN1x2igwPpfkzo.

- Elhai. J. D., & Ford, J, D. (2009). Utilization of healthcare services after disasters. In Y. Neria, S. Galea, & F. Norris (Eds.). Mental health and disasters (pp. 366-386). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Enyama D, Chelo D, Noukeu Njinkui D, Mayouego Kouam J, Fokam Djike Puepi Y, Mekone Nkwele I, Ndenbe P, Nguefack S, Nguefack F, Kedy Koum D, Tetanye E. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatricians' clinical activity in Cameroon. Arch Pediatr. 2020 Sep 23:S0929-693X(20)30203-7. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2020.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Everly G.S., Jr., Flynn B.W. Principles and practical procedures for acute psychological first aid training for personnel without mental health experience. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health. 2006;8:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother, G. Stuber. J. Galea, S. Pfefferbaum. B. & Fleischman. A. R. (2004). Unmet need for counseling services by children in New York City after the September 11 th attacks on the World Trade Center: Implications for pediatricians. Pediatrics, 113, 1367-1374. doi: 10.1542/peds, 113.5.1367. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Farmer, B . Long-standing racial and income disparities seen creeping into COVID-19 care. Published April 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020. https://khn.org/news/covid-19-treatment-racial-income-health-disparities/Google Scholar.

- Fitzgerald D.A., Nunn K., Isaacs D. Consequences of physical distancing emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic: An Australian perspective. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 2020 Sep;35:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D., Fletcher S., Wolfgang B., Varker T., Creamer M., Brymer M. Practitioner perceptions of Skills for Psychological Recovery: A training program for health practitioners in the aftermath of the Victorian bushfires. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44:1105–1111. doi: 10.3109/(X)048674.2010.513674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E. Fraser Fraser, E. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Violence Against Women and Girls (Helpdesk Research Report No. 284; p. 16). VAWG Helpdesk. https://bettercarenetwork.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/vawg-helpdesk-284-covid-19-and-vawg.pdf.

- Futures of 370 million children in jeopardy as school closures deprive them of school meals – UNICEF and WFP.https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/futures-370-million-children-jeopardy-school-closures-deprive-them-school-meals (Assessed Nov2,2020).

- Goenjian A.K., Steinberg A.M., Najarian L.M. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depressive reactions after earthquake and political violence. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000 Jun;157(6):911–916. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goenjian A.K., Walling D., Steinberg A.M., Karayan I., Najarian L.M., Pynoos R. A prospective study of posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among treated and untreated adolescents 5 years after a catastrophic disaster. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(12):2302–2308. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Mental Health for Children and Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. Published online April 14, 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Golberstein E., Gonzales G., Meara E. How do economic downturns affect the mental health of children? evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. Health Economics. 2019;28(8):955–970. doi: 10.1002/hec.3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk, F. (2019), “Impacts of technology use on children: Exploring literature on the brain, cognition and well-being”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 195, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/8296464e-en.

- Götzinger F., Santiago-García B., Noguera-Julián A. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: A multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(9):653–661. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham W.J., Afolabi B., Benova L. Protecting hard-won gains for mothers and newborns in low-income and middle-income countries in the face of COVID-19:Call for a service safety net. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudbjartsson, D. et al. (2020), “Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic Population”, New England Journal of Medicine, p. NEJMoa2006100, http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa2006100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gupta S., Sahoo S. Pandemic and mental health of the front-line healthcare workers: A review and implications in the Indian context amidst COVID-19. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33 doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale, J. (2020), The politics of Covid-19: government contempt for disabled people, Red Pepper, https://www.redpepper.org.uk/covid-19-disabled-peoples-rights/?fbclid=IwAR3DcIEKZHbMZCney2aAagVTWoU7Bq9Oy9WZFxLLcYRw5CUI7wCIuCaSi-M.

- Hamadani J.D., Hasan M.I., Baldi A.J. Immediate impact of stay-at-home orders to control COVID-19 transmission on socioeconomic conditions, food insecurity, mental health, and intimate partner violence in Bangladeshi women and their families: An interrupted time series. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;S2214–109X(20):30366–30371. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jun;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. Epub 2020 Apr 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hungerford D., Cunliffe N.A. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) - impact on vaccine preventable diseases. Eurosurveillance Weekly. 2020;25(18):2000756. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.2000756. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.2000756. PMID: 32400359; PMCID: PMC7219030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt P. European Commission; Brussels: 2019. Target Group Discussion Paper on Children with Disabilities - Feasibility Study for a Child Guarantee. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1428&langId=fr&moreDocuments=yes. [Google Scholar]

- IASC, Guidance on COVID-19 Prevention and Control in Schools https://www.unicef.org/reports/key-messages-and-actions-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-prevention-and-control-schools.

- India Today Coronavirus: doctor returns home, breaks down after stopping son from hugging him. Emotional video. 2020. www.indiatoday.in/trending-news/story/coronavirus-doctor-returns-home-breaks-down-after-stopping-son-from-hugging-him-emotional-video-1660624-2020-03-28.

- In India, over 32 crore students hit by Covid-19 as schools and colleges are shut: UNESCO. https://theprint.in/india/education/in-india-over-32-crore-students-hit-by-covid-19-as-schools-and-colleges-are-shut-unesco/402889/ (accessed Oct29, 2020).

- Statistics Indonesia & UNICEF. (2016). Kemajuan yang Tertunda: Analisis Data Perkawinan Usia Anak di Indonesia [Progress on pause: Analysis of child marriage data in Indonesia].Jakarta: Statistics Indonesia.Group, U. (ed.) (2020), The Impact of COVID-19 on children, United Nations, New York, https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-impact-covid-19-children (accessed on September 29, 2020).

- Indoor play ideas to stimulate young children at home. https://www.unicef.org/parenting/coronavirus-covid-19-guide-parents/indoor- play-ideas-stimulate-young-children-home.

- Jayasinghe, N. Giosan, C, Difede, J., Spielman, L, A. & Robin, L, (2006), Predictors of responses to psychotherapy referral of WTC utility disaster workers. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 19, 307-312, doi:l0.1002/jts.201l3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jaycox. L. H., Cohen, J. A. Mannarino, A. P., Walker, D. W., Langley, A. K., Gegenheimer. K. L Schonlau, M. (2010). Children's mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: A field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23, 223-231. doi: 10.l002/jts.205l8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jiao W.Y., Wang L.N., Liu J., Fang S.F., Jiao F.Y., Pettoello-Mantovani M. Behavioral and Emotional Disorders in Children during the COVID-19 Epidemic. Journal of Pediatrics. 2020;221(264–266) doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen T.B., Astrup E., Jore S. Infection preventionguidelines and considerations for paediatric risk groups whenreopening primary schools during COVID-19 pandemic, Norway, April 2020. Eurosurveillance Weekly. 2020;25(22):2000921. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.22.2000921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar N. Psychological impact of disasters on children: Review of assessment and interventions. World Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;5:5–11. doi: 10.1007/s12519-009-0001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kichloo A, Albosta M, Dettloff K, et al. Telemedicine, the current COVID-19 pandemic and the future: a narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA Family Medicine and Community Health 2020;8:e000530. doi: 10.1136/fmch-2020-000530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Laor N., Wiener Z., Spiriman S., Wolmer L. Community mental health in emergencies and mass disasters: The Tel-Aviv model Journal of Aggression. Maltreatment and Trauma. iO. 2005;681–694 doi: 10.1300/JI46vl0n03_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.J., Bao Y., Huang X., Shi J., Lu L. Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(5):347–349. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.H., Doan S.N. Psychosocial Stress Contagion in Children and Families During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2020;59(9–10):853–855. doi: 10.1177/0009922820927044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livinsgtone, S. (2020), Coronavirus and #fakenews: what should families do?, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/medialse/2020/03/26/coronavirus-and-fakenews-what-should-families-do.

- Nutrition Information Management, Surveillance and Monitoring in the Context of COVID-19. https://www.unicef.org/documents/nutrition-information-management-surveillance-and-monitoring-context-covid-19. (Assessed Nov1, 2020).

- Marshan, J. N., Rakhmadi, F., & Rizky, M. (2016). Prevalence of child marriage and its determinants among young women in Indonesia. Paper presented at 2016 conference on child poverty and social protection, Jakarta.

- Matsuo T., Kobayashi D., Taki F., Sakamoto F., Uehara Y., Mori N. Prevalence of health care worker burnout during the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Japan. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, O. L., Everly, G. S., Jr., Brown, L. M., Wendelboe, A. M., Abd Hamid, N. H., Tallchief, V. L., & Links, J. M. (2014). Psychological first aid: A consensus-derived, empirically supported, competency-based training model. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 621–628.http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McDonald H.I., Tessier E., White J.M., Woodruff M., Knowles C., Bates C. Early impact of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and physical distancing measures on routine childhood vaccinations in England, January to April 2020. Eurosurveillance Weekly. 2020;25(19):2000848. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.19.2000848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measures to maintain regular operations and prevent outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 in childcare facilities or schools under pandemic conditions and co-circulation of other respiratory pathogens. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344394316_Measures_to_maintain_regular_operations_and_prevent_outbreaks_of_SARS-CoV-2_in_childcare_facilities_or_schools_under_pandemic_conditions_and_co-circulation_of_other_respiratory_pathogens [accessed Nov 18 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Meiser-Stedman R., Smith P., McKinnon A., Dixon C., Trickey D., Ehlers A. Cognitive therapy as an early treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: A randomized controlled trial addressing preliminary efficacy and mechanisms of action. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2017;58(5):623–633. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitigating the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on food and nutrition of school children.https://www.unicef.org/documents/mitigating-effects-covid-19-pandemic-food-and-nutrition-school-children. (Assessed Oct31, 2020).

- Monaghesh E., Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: A systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1193. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- More than 117 million children at risk of missing out on measles vaccines, as COVID-19 surges.https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/more-117-million-children-risk-missing-out-measles-vaccines-covid-19-surges.

- National Commission on Children and Disasters. (2010). National Commission on Children and Disasters: 2010 report to the president and congress. Retrieved from http://www.childrenanddisasters.acf.hhs.gov.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder NICE Guideline. NICE, 2018. [PubMed]

- NHS (2020), Coronavirus (COVID-19): How To Look After Your Mental Wellbeing While Staying At Home, https://www.nhs.uk/oneyou/every-mind-matters/coronavirus-covid-19-staying-at-home-tips/ (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A et al. The Socio-Economic Implications of the Coronavirus and COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review, International Journal of Surgery, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- OECD . OECD Publishing, Paris; Policy Brief on Affordable Housing: 2020. Better data and policies to fight homelessness in the OECD. http://oe.cd/homelessness-2020. (accessed on October 20, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2020), OECD Draft Recommendation on Children in the Digital Environment: Revised Typology of Risks, https://one.oecd.org/document/ DSTI/CDEP/DGP(2020)3/en/pdf.

- OECD (2020), Supporting people and companies to deal with the COVID-19 virus: Options for an immediate employment and social-policy response, OECD, Paris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=119_119686-962r78x4do&title=Supporting _people_and_companies_to_deal_with_the_Covid-19_virus (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- OECD (2020), CO2.2: Child poverty, OECD Family Database, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- OECD (2020), CO2.2: Child poverty, OECD Family Database, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed on October 20, 2020).

- Olorunsaiye CZ, Yusuf KK, Reinhart K, Salihu HM. COVID-19 and Child Vaccination: A Systematic Approach to Closing the Immunization Gap. Int J MCH AIDS. 2020;9(3):381-385. doi: 10.21106/ijma.401. Epub 2020 Sep 15. PMID: 33014624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pandey S.K., Sharma V. A tribute to frontline corona warriors––Doctors who sacrificed their life while saving patients during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2020;68:939–942. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_754_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plan International, ‘Living Under Lockdown: Girls and Covid-19’, Plan International, 29 April 2020, <https://plan-international.org/publications/living-under-lockdown> accessed September28, 2020.

- Public Health England . Public Health England; London: 2020. Guidance for parents and carers on supporting children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-guidance-on-supporting-children-and-young-peoples-mental-health-and-wellbeing/guidance-for-parents-and-carers-on-supporting-children-and-young-peoples-mental-health-and-wellbeing-during-the-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak (accessed on October 22, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Radia T, Williams N, Agrawal P, Harman K, Weale J, Cook J, Gupta A. Multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children & adolescents (MIS-C): A systematic review of clinical features and presentation. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2020 Aug 11:S1526-0542(20)30117-2. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2020.08.001. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32891582; PMCID: PMC7417920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ramaswamy S., Seshadri S. Children on the brink: Risks for child protection, sexual abuse, and related mental health problems in the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;62(9):pages 404. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_1032_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy E. The New Humanitarian; 2020. How the coronavirus outbreak could hit refugees and migrants. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro V.V., Dassie-Leite A.P., Pereira E.C., Santos A.D.N., Martins P., Irineu R.A. Effect of Wearing a Face Mask on Vocal Self-Perception during a Pandemic. Journal of Voice. 2020;S0892–1997(20):30356–30358. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelen, K. (2020), Coronavirus and poverty: we can’t fight one without tackling the other – Poverty Unpacked, https://poverty-unpacked.org/2020/03/23/coronavirus-and-poverty-we-cant-fight-one-without-tackling-the-other/ (accessed on Oct 20,2020).

- Röhr S, Müller F, Jung F, Apfelbacher C, Seidler A, Riedel-Heller SG. Psychosoziale Folgen von Quarantänemaßnahmen bei schwerwiegenden Coronavirus-Ausbrüchen: ein Rapid Review [Psychosocial Impact of Quarantine Measures During Serious Coronavirus Outbreaks: A Rapid Review]. Psychiatr Prax. 2020 May;47(4):179-189. German. doi: 10.1055/a-1159-5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Röhr S, Müller F, Jung F, Apfelbacher C, Seidler A, Riedel-Heller SG. Psychosoziale Folgen von Quarantänemaßnahmen bei schwerwiegenden Coronavirus-Ausbrüchen: ein Rapid Review [Psychosocial Impact of Quarantine Measures During Serious Coronavirus Outbreaks: A Rapid Review]. Psychiatr Prax. 2020 May;47(4):179-189. German. doi: 10.1055/a-1159-5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rundle, A. et al. (2020), “COVID‐19–Related School Closings and Risk of Weight Gain Among Children”, Obesity, p. oby.22813, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/oby.22813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ruzek J.I., WaLser R.D., Naugle A.E., Litz B.T., Mennin D.S., Polusny M.A. Cognitive-behavioral psychology: Implications for disaster and terrorism response. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2008;23:397–410. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00006130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzek J.I., Young B.H., Cordova M.J., Flynn B.W. Integration of disaster mental health services with emergency services. Prehospitat and Disaster Medicine. 2004;19:46–53. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00001473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo S., Mehra A., Suri V., Malhotra P. Handling children in COVID wards: A narrative experience and suggestions for providing psychological support. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Jun;13(53) doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos N D, Ghazy R. COVID-19 places half a million more girls at risk of child marriage in 2020. https://www.savethechildren.net/news/covid-19-places-half-million-more-girls-risk-child-marriage-2020.

- Saurabh K, Ranjan S. Compliance and Psychological Impact of Quarantine in Children and Adolescents due to Covid-19 Pandemic. Indian J Pediatr. 2020 Jul;87(7):532-536. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03347-3. Epub 2020 May 29. PMID: 32472347; PMCID: PMC7257353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Saurabh K., Ranjan S. Compliance and Psychological Impact of Quarantine in Children and Adolescents due to Covid-19 Pandemic. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2020 Jul;87(7):532–536. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03347-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, K, Patricia L, Julie P. 2016.Housing Children: South Auckland the Housing Pathways Longitudinal Study.Auck-land: Department of Anthropology, University of Auckland.http://cdn.auckland.ac.nz/assets/arts/schools/ anthropology/rale-06.pdf (Used with permission).

- Shearer J., Papanikolaou N., Meiser-Stedman R., McKinnon A., Dalgleish T., Smith P. Cost-effectiveness of cognitive therapy as an early intervention for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: A trial based evaluation and model. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2018;59(7):773–780. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, W. K., Ortiz, C. D., Viswesvaran, C, Burns, B. J., Kolko, Putnam, F. W., & Amaya-Jackson, L. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatment for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37,156-183. doi:10.1080/15374410701818293. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sim H.S., How C.H. Mental health and psychosocial support during healthcare emergencies - COVID-19 pandemic. Singapore Medical Journal. 2020 Jul;61(7):357–362. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2020103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Roy D., Sinha K., Parveen S., Sharma G., Joshi G. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: A narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Research. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siswa Widyatmoko C., Tan E.T., Conor Seyle D., Haksi Mayawati E., Cohen Silver R. Coping with natural disasters in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: The psychological state of elementary school children as assessed by their teachers. School Psychology International. 2011;32(5):484–497. doi: 10.1177/0143034311402919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souadka A, Essangri H, Benkabbou A, Amrani L, Majbar MA. COVID-19 and Healthcare worker's families: behind the scenes of frontline response. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;23:100373. Published 2020 May 3. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Spoorthy M.S., Pratapa S.K., Mahant S. Mental health problemsfaced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic-a review. Asian. J. Psychiatr. 2020;51(102119) doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprang G., Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2013;7(1):105–110. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, A. M., White, A. E., Rotter, N. S. & Basu, A. Shifting from survival to supporting resilience in children and families in the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons for informing U.S. mental health priorities. Psychol. Trauma 12, S133–S135 (202l). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sharma N. Stigma: the other enemy India's overworked doctors face in the battle against Covid-19. Quartz India. 2020 https://qz.com/india/1824866/indian-doctors-fighting-coronavirus-now-face-social-stigma/ published online March 25. (accessed August 29, 2020) [Google Scholar].

- Sundus M. The Impact of using Gadgets on Children. J Depress Anxiety. 2018;7:296. doi: 10.4172/2167-1044.1000296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ThapaB GitaS, Chatterjee K. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of the society & HCW (healthcare workers): A systematic review. International Journal of Science & Healthcare. Research. 2020;5(2):234–240. [Google Scholar]

- The L. COVID-19: Protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tol W.A., Komproe I.H., Susanty D., Jordans M.J., Macy R.D., De Jong J.T. School-based mental health intervention for children affected by political violence in Indonesia: A cluster randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(6):65562. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomori C, Gribble K, Palmquist AEL, Ververs MT, Gross MS. When separation is not the answer: Breastfeeding mothers and infants affected by COVID-19. Matern Child Nutr. 2020 May 26;16(4):e13033. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13033. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tomori C., Gribble K., Palmquist A.E.L., Ververs M.T., Gross M.S. When separation is not the answer: Breastfeeding mothers and infants affected by COVID-19. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;16(4) doi: 10.1111/mcn.13033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO, COVID-19 school closures around the world will hit girls hardest, 2020.

- UNICEF says COVID-19 pandemic requires comprehensive action to protect children’s safety, well-being and futures. https://www.unicef.org/azerbaijan/ press-releases/unicef-says-covid-19-pandemic-requires-comprehensive-action-protect-childrens-safety.

- UNICEF. How to talk to your child about coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.unicef.org/coronavirus/how-talk-your-childabout-coronavirus covid-19 (accessed October 28, 2020).

- United Nations Children’s Fund, ‘COVID-19: Number of children living in household poverty to soar by up to 86 million by end of year’, Press release, UNICEF, 27 May 2020, <https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/covid-19-number-children-living-household-poverty-soar-86-million-end-year> accessed 28 August 2020.

- UNPFA (2020), Interim Technical Note Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender-based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage, UNPFA, https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/COVID-19_impact_brief_for_UNFPA_24_April_2020_1.pdf (accessed on September 29,2020).

- Van Lancker W., Parolin Z. cOVid-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e243–e244. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner R.M., Russell S.J., Croker H. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: A rapid systematic review. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health. 2020 May;4(5):397–404. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(20)30095-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Zhang Y., Zhao J., Zhang J., Jiang F. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395:945–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson P.J., Brymer M.J., Bonanno G.A. Postdisaster psychological intervention since 9/11. American Psychologist. 2011;66:482–494. doi: 10.1037/a0024806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . WHO; Geneva: 2020. Helping children cope with stress during the 2019-nCoV outbreak. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/helping-children-cope-with-stress-print.pdf?sfvrsn=f3a063ff_2 (accessed on 23 March 2020) [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2020). Adolescent pregnancy. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy.

- Women’s Safety NSW (2020), New Domestic Violence Survey Shows Impact of COVID-19 on the Rise, Media Release, https://www.womenssafetynsw.org.au/impact/article/new-domestic-violence-survey-shows-impact-of-covid-19-on-the-rise/ (accessed on Nov 05, 2020).

- World Bank, We should avoid flattening the curve in education – Possible scenarios for learning loss during the school lockdowns, https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/we-should-avoid-flattening-curve-education-possible-scenarios-learning-loss-during-school?CID=WBW_AL_BlogNotification_EN_EXT).