Abstract

The evolutionary trajectories of early lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) have not been fully elucidated. We hypothesize that genomic analysis between pre-invasive and invasive components will facilitate the description of LUAD evolutionary patterns. We micro-dissect malignant pulmonary nodules (MPNs) into paired pre-invasive and invasive components for panel-genomic sequencing and recognize three evolutionary trajectories. Evolutionary mode 1 (EM1) demonstrates none of the common driver events between paired components, but another two modes, EM2A and EM2B, exhibit critical private alterations restricted to pre-invasive and invasive components, respectively. When ancestral clones harbor EGFR mutations, truncal mutation abundance significantly decrease after the acquisition of invasiveness, which may be associated with the intratumoral accumulation of infiltrated B cells. Harboring EGFR mutations is critical to the selective pressure and further impacts the prognosis. Our findings extend the understanding of evolutionary trajectories during invasiveness acquisition in early LUAD.

Subject terms: Cancer genomics, Non-small-cell lung cancer, Preclinical research, Non-small-cell lung cancer

Invasive early stage lung adenocarcinoma has a heterogeneous prognosis. Here, the authors microdissect malignant pulmonary nodules to invasive and preinvasive components and study the mutations that are common or private between the lesions, allowing them to understand the evolutionary path of the tumours.

Introduction

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most commonly diagnosed subtype of lung cancer and the leading cause of cancer deaths, both globally and in China1. Although high-resolution computed tomography (CT) screening has resulted in a drastic increase in malignant pulmonary nodules (MPNs)2, LUAD is still considered a heterogeneous prognosis disease, even in the early stage3. Tumor invasive status has a notable impact on prognosis for LUAD, especially in early-stage cases4. Although surgical resection was reported to yield an almost 100% 5-year survival rate for pre-invasive status (AAH, atypical adenomatous hyperplasia and AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ), early invasive LUAD had a worse prognosis with a certain recurrence rate5.

The invasive components in MPNs, including minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) and invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC), are demonstrated to be an important precise prognostic discriminator and better than the T descriptor of the TNM staging system6,7. However, there is still little understanding of the initiation, early progression, and evolutionary patterns of invasive components in MPNs8,9. Genome-wide somatic mutation analysis has advanced our understanding of critical molecular events in cancer progression and evolution. Although it was proposed that AAH may progress to AIS, MIA and, eventually, IAC in a linear manner5, the evolutionary trajectory from pre-invasive to invasive LUAD has not been fully elucidated10. Previous studies demonstrated significant genetic differences among AAH, AIS, and MIA; however, pre-invasive and invasive LUAD have never been investigated within a single MPN10–14.

EGFR and KRAS are two frequently mutated driver genes of LUAD. Early-stage EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases usually have a better prognosis than wild-type or KRAS-mutated cases, even without tyrosine-kinase inhibitor (TKI) application15–17. Additionally, EGFR mutation is considered a positive prognostic marker of both disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in T1-2aN0M0 patients without adjuvant and TKI treatments15. This evidence implies that EGFR mutations may contribute differently to clonal selection in early-stage LUAD evolution compared to KRAS and other mutations18. However, to date, little is known regarding whether and how these dominant driver genes affect early progression from pre-invasive to invasive LUAD.

To delineate the driver molecular events and early invasive progression in MPNs, we included 53 T1 stage LUAD cases of the ChiCTR1900022521 cohort of Jiangsu Cancer Hospital (JSCH) with micro-dissection and panel-genomic-sequencing methods, as well as 496 T1 stage patients with long-term follow-up from the Boston Lung Cancer Study (BLCS) cohort. We focused on genetic heterogeneities between pre-invasive and invasive components, early invasive patterns, and the prognosis of MPN patients. Phylogenetic analyses showed the differences among evolutionary trajectories, and the results further elucidated strong selective pressure and enhanced B cell infiltration during invasiveness acquisition of MPNs harboring truncal EGFR mutations.

Results

Study workflow and genetic landscape

A total of 53 cases were included for the genomic sequencing and data analyses (Supplementary Fig. 1a). All 53 LUAD patients were diagnosed with MPN ≤ 3 cm and pathologically confirmed adenocarcinoma, and lymph node metastasis was found in three cases (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Data 1). Sixty-one of 69 MPNs were conducted with microdissection to separate pre-invasive and adjacent invasive components, including 52 paired components (Supplementary Fig. 1b; Supplementary Data 2). Out of sequenced the 113 MPN components, 8 whole MPNs, 5 metastatic lymph nodes (MLNs), and 79 cfDNA specimens, somatic mutations were found in all MPNs and MLNs and in 23 cfDNA samples (Supplementary Fig. 2a; Supplementary Data 3).

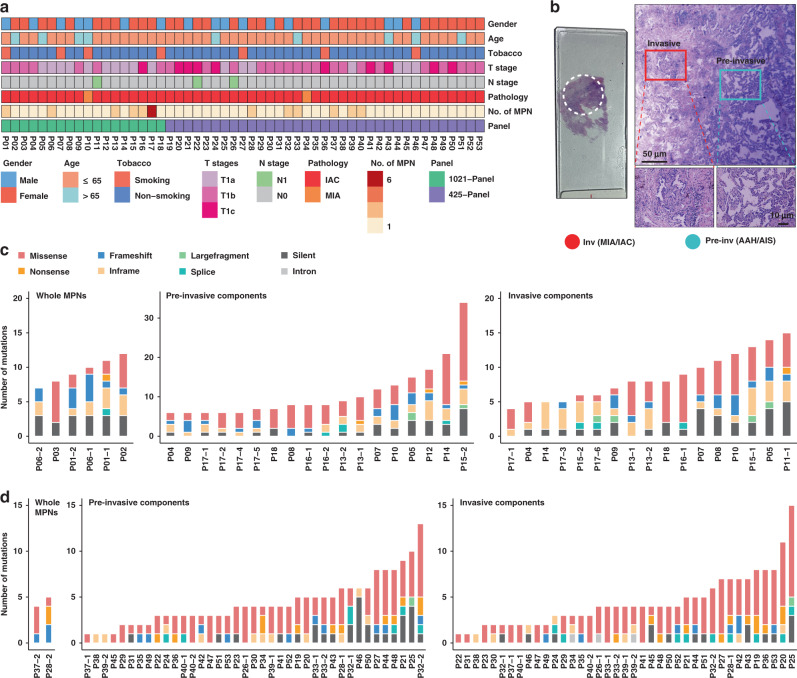

Fig. 1. Clinicopathological characteristics and genomic sequencing of micro-dissected MPNs.

a Clinicopathologic characteristics of the included 53 T1 stage LUAD patients. b Micro-dissection was performed to separate pre-invasive and invasive components within MPNs. c, d Number and type of somatic mutations detected in 6 whole MPNs and 35 micro-dissected MPN components of the cases using 1021-panel (Phase 1; c), and somatic mutations detected in 2 whole MPNs and 78 micro-dissected MPN components of the cases using 425-panel (Phase 2; d). Inv Invasive, Pre-Inv pre-invasive, AAH atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, AIS adenocarcinoma in situ, MIA minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, IAC invasive adenocarcinoma.

Globally, 1–34 somatic mutations (median: 8) were identified in each MPN component of the phase 1 study (Fig. 1c), and 1–15 somatic mutations (median: 4) were observed in the subsequent phase 2 study (Fig. 1d). In addition to the most frequently mutated gene EGFR, TP53, MED12, and ERBB2 were the top mutated driver genes in tissue samples (Supplementary Fig. 2b). EGFR L858R was to be the most recurrent variation in this cohort (Supplementary Fig. 2c), and EGFR had higher mutation rates in female cases (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Notably, no significant differences in these driver genes were observed between pre-invasive and invasive MPN components (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The proportions of all six mutation groups showed a greater proportion of C > G transversions in the invasive components (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Phylogenetic analyses within MPNs revealed three evolutionary trajectories

To investigate the evolutionary relationship between early pre-invasive and invasive LUAD within the MPNs, we analyzed on 52 paired pre-invasive and adjacent invasive MPN components using phylogenetic methods (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 4; Supplementary Data 4). First, five MPNs from three cases revealed no truncal driver mutations between pre-invasive and adjacent invasive components (Supplementary Fig. 4a), which indicated that pre-invasive and invasive LUAD were driven by different driver events in this situation (Evolution Mode 1, EM1). Second, a total of 45 MPNs harbored truncal critical alterations between pre-invasive and adjacent invasive components (Evolution Mode 2, EM2), and we detected key mutations restricted to pre-invasive branches in 26 of these MPNs, which were classified as EM2A (Supplementary Fig. 4b). In the remaining 19 pairs we observed branch driver mutations only in the invasive components, which revealed a potential linear progression for pre-invasive and adjacent invasive LUAD (classified as EM2B; Supplementary Fig. 4c). Third, no private mutations were discovered in the remaining two MPNs (Supplementary Fig. 4d), which suggests the limitation of our approach to detect other potential key alterations in branches. We also performed phylogenetic analyses of the pre-invasive, invasive components, and MLNs in JSCH P26 of EM2B, which buttressed the supposed linear evolution (Supplementary Fig. 4e).

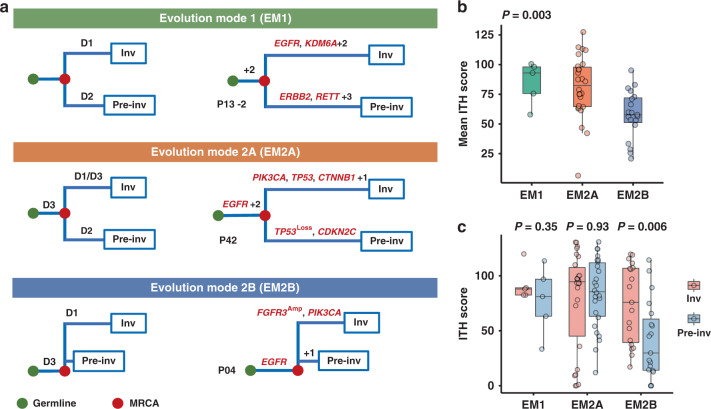

Fig. 2. Phylogenetic analyses within MPNs.

a Evolutionary trajectories of pre-invasive and adjacent invasive MPN components. For each of the three evolutionary patterns, D1, D2, and D3 indicate three hypothetical key molecular events in trunk and branches of phylogenetic tree; green dots represent the germline and red dots represent the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) for each pair of components. In evolution mode 1 (EM1), none of driver mutations are shared and D1 and D2 indicate different private driver alterations (Supplementary Fig. 4a), and JSCH P13-2 is a representative MPN. In evolution mode 2 (EM2), MRCA harbors critical common events (D3). Private driver alterations of D2 and D1 are restricted to the pre-invasive component (EM2A; Supplementary Fig. 4b) and the invasive component (EM2B; Supplementary Fig. 4c), respectively. Phylogenetic trees of JSCH P42 and P04 are shown to represent EM2A and EM2B separately. b Mean intratumor heterogeneity (ITH) score of 50 paired pre-invasive and adjacent invasive components suggests phenotypic differences including EM1 (MPNs, n = 5), EM2A (MPNs, n = 26), and EM2B (MPNs, n = 19). The differences were assessed using Kruskal–Wallis H test. c Comparisons of ITH levels between 50 paired pre-invasive and invasive components were performed using two-sided Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. The box plot displays the first and third quartiles (top and bottom of the boxes), median (band inside the boxes), and lowest and highest point within 1.5 times the interquartile range of the lower and higher quartile (whiskers). Inv, Invasive and Pre-Inv, Pre-invasive.

To estimate genetic relatedness, we quantified the intratumor heterogeneity (ITH) of paired components within each evolution mode. The results demonstrated that EM1 got the highest ITH level, and EM2B had the lowest ITH level, as expected (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 5a). The ITH level of invasive components was significantly higher than the adjacent pre-invasive components in EM2B (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Fig. 5b), which indicates clonal expansion during the early progression19. Notably, we observed differential tumor sizes among EMs (Supplementary Fig. 5c), and we supposed that a strong interclonal competition of EM1 would lead to a relatively smaller tumor size compared with EM2.

Dominant driver genes in truncal mutations

The truncal mutations profile indicated that EGFR, TP53, KRAS, and STK11 were recurrently mutated driver genes, and almost all truncal mutation genes were known drivers (Fig. 3a). EGFR, CDK4, and TP53 were the top frequently altered driver genes of the invasive branching mutations (Supplementary Fig. 6a), and TP53 carried the highest number of alterations in the pre-invasive branch mutation profile (Supplementary Fig. 6b). We also found that RTK-RAS pathway-related genes (i.e., EGFR, KRAS, and ERBB2) contributed mostly to truncal mutations both in two-phase studies (Supplementary Fig. 6c). As expected, the decreased ratio of pre-invasive branching mutations (dN/dS ratio) suggested a relaxed ability of promoting progression in pre-invasive branches (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. 6d). We also considered the potential function of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) in affecting tumor evolution20, and the results demonstrated that critical double-hit events of TSGs, including gene loss, homozygotic mutation, and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) plus mutation, contributed differentially to EM2A and EM2B (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Data 6).

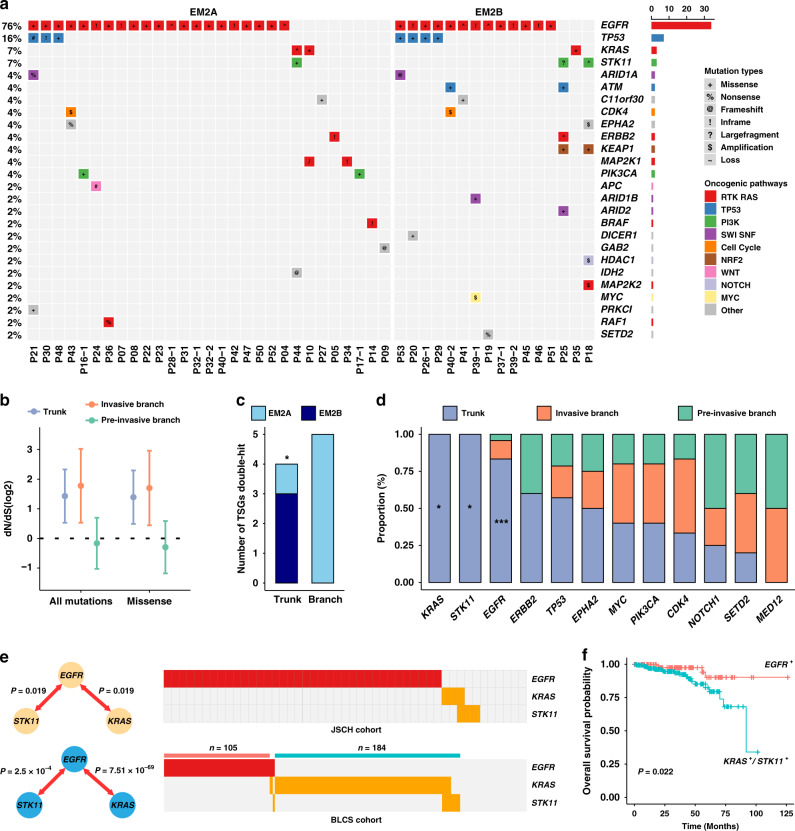

Fig. 3. Dominant drivers in truncal genes are associated with clinical outcomes.

a Mutational spectrum of recurrent non-synonymous truncal mutations. Truncal genes were defined according to known oncogenic pathways identical to those previously reported (see “Methods” section). b The ratios of nonsynonymous to synonymous mutations among trunks, pre-invasive, and invasive branches among all MPNs (n = 52). The dN/dS ratios of all nonsynonymous mutations or missense mutations relative to synonymous mutations are shown (on log2 scale). Circles and vertical lines correspond to the mean and 95% confidence intervals of the dN/dS ratio, respectively. c Differences in tumor suppressor gene (TSG) double-hit events, including gene loss, homozygotic mutation and LOH plus mutation, between EM2A (MPNs, n = 26) and EM2B (MPNs, n = 19) were compared using two-sided Fisher’s exact test (P = 0.048). d The proportions of truncal and branching mutations in each of the recurrent driver genes of EM2 (MPNs, n = 45). Corresponding P values calculated by two-sided Fisher’s exact test in KRAS, STK11, and EGFR were 0.035, 0.035, and 6.96 × 10-8, respectively. e Mutually exclusive analyses of truncal mutations in the JSCH cohort and driver mutations in the BLCS cohort, which suggest two typical clusters of LUAD patients. P value was calculated using pair-wise Fisher’s exact test. f Kaplan–Meier curves using the BLCS cohort to compare the prognosis between EGFR- and KRAS/STK11-mutated T1 stage cases in BLCS cohort. P value was calculated using log-rank test is indicated. ***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05.

EGFR, KRAS, and STK11 were three dominant truncal driver genes (Fig. 3d). Somatic interaction analysis indicated that EGFR was mutually exclusive from the other two truncal drivers, which was validated in the BLCS and TCGA cohorts (Fig. 3e; Supplementary Fig. 6e; Supplementary Data 7). Importantly, survival analysis indicated a better prognosis of EGFR-mutated patients than KRAS/STK11-mutated patients in the BLCS cohort (Fig. 3f), and the TCGA data suggested a consistent trend (Supplementary Fig. 6f).

Truncal EGFR mutation is associated with strong selective pressure and B cell infiltration

We compared the abundance of identified truncal EGFR mutations between pre-invasive and adjacent invasive components. Intriguingly, the results demonstrated that the abundance of EGFR mutations in the invasive component was significantly lower than that in the adjacent pre-invasive component (Fig. 4a). We subsequently analyzed the abundance change of truncal mutations between MPNs harboring or not harboring truncal EGFR mutations, and the results suggested that truncal mutation abundance in EGFR-mutated MPNs was significantly reduced (Fig. 4b). These results indicated a strong selective pressure on EGFR-mutated tumor cells during the acquisition of invasiveness. The decreased dN/dS ratios of mutations in the MPNs harboring truncal EGFR mutation buttressed these findings (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Fig. 6d).

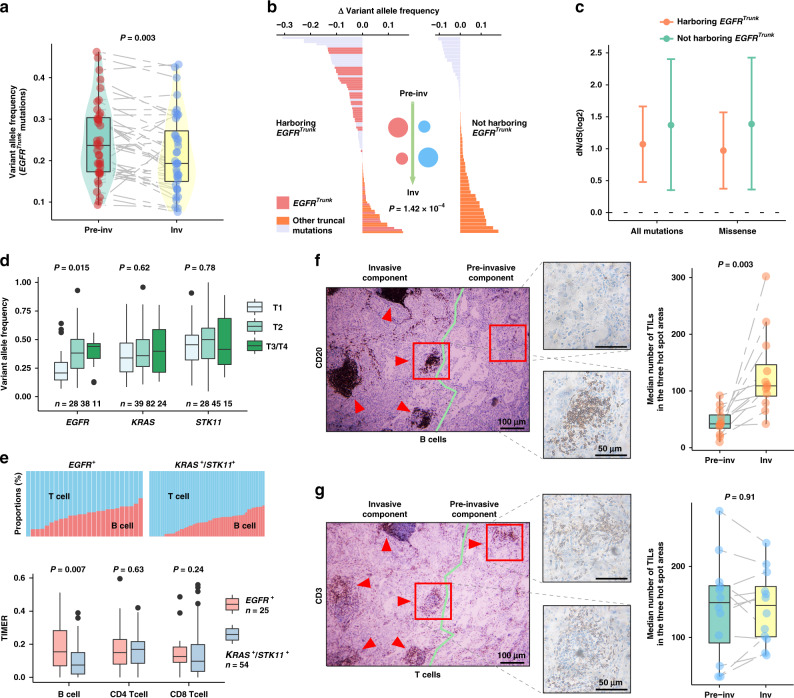

Fig. 4. Strong selective pressure derived from B cell infiltration in MPNs harboring truncal EGFR mutation.

a Variant allele frequency (VAF) of identified truncal EGFR mutations in 36 paired pre-invasive and adjacent invasive components. Differences were assessed using the two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. b Mutant abundance change of identified truncal mutations between two components in EM2, according to whether they harbored truncal EGFR mutations. Red and blue circles represent the putative truncal clone abundance of two groups during the invasive progression, respectively. P value was derived from two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. c The dN/dS ratios inferred for 36 MPNs harboring and 11 MPNs not harboring truncal EGFR mutations. These ratios were obtained as described for Fig. 3b. Circles and vertical lines correspond to the mean and 95% confidence intervals of the dN/dS ratio, respectively. d Mutation abundance in EGFR, KRAS, and STK11 mutations in the TCGA LUAD data for patients of stages T1–4. Differences among stages were assessed by Kruskal–Wallis H test. e Comparisons of T cells and B cells between EGFR- and KRAS/STK11-mutated groups using TIMER inflammatory infiltration in T1 stage cases of TCGA. P value, two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. f, g Representative sliced IHC images of B cells f and T cells g in 12 EGFR-mutated patients. Two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for paired invasive and pre-invasive components. Bar, median; box, 25th–75th percentiles (interquartile range, IQR); vertical line, data within 1.5 times the IQR. Inv Invasive and Pre-inv Pre-invasive.

Our previous study observed an association between EGFR mutation and inflammatory infiltration in NSCLC patients21. Therefore, we proposed that the selective pressure from inflammatory infiltration contributed to the differential prognosis in T1 stage LUAD patients. We analyzed the TCGA cohort and found that the mutation abundance of EGFR was significantly decreased in T1 stage, which was different from the exclusive driver genes KRAS and STK11 (Fig. 4d). Additionally, EGFR mutation was found to be associated with specific high B cell infiltration in the T1 stage (Fig. 4e; Supplementary Fig. 7c,d). To validate this hypothesis, we further performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays to evaluate the microenvironmental B and T cell infiltration of EGFR-mutated cases. The results confirmed that B cells (CD20+) were present at higher levels in the invasive component than the adjacent pre-invasive component (Fig. 4f), while no significant differences of T cells (CD3+) between the two components were observed in the serial histological sections (Fig. 4g).

In addition, we identified somatic mutations in 12 prior-operation and 11 post-operation cfDNAs (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b), and no significant differences in mutation abundances were found between prior-operation and post-operation cfDNA samples (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Notably, we did not detect EGFR mutations both in prior-operation and post-operation cfDNAs (Supplementary Fig. 8d; Supplementary Data 8).

Discussion

There is little understanding of the histological continuum preceding early invasive progression in LUAD. Multi-region sampling and genomic sequencing revealed significant ITH, even in the pre-invasive AIS14,22. Evaluating the evolutionary trajectory of early invasive LUAD is critical to elucidate the mechanism of early invasive progression, classify molecular genotypes, and provide potential strategies for early intervention. However, conflicting findings were obtained in investigations of early invasive driver events10,11,14,22. Evgeny et al. found that KRAS, TP53, and EGFR mutations were indicators of malignant transition from AAH to AIS/MIA22. Sivakumar et al. demonstrated that BRAF and KRAS were initiated as driver events in AAH, but EGFR and TP53 were secondary driver events in LUAD11. Xin et al. observed truncal EGFR and KRAS mutations between pre-invasive and invasive LUAD in multifocal MPNs from the same patients10. Zhang et al. demonstrated that EGFR, ERBB2, NRAS, and BRAF were early clonal genomic events in AIS, but TP53 was only found in MIA and IAC14. Consistent with previous studies, we revealed that trunk mutations of common driver genes (i.e., EGFR, TP53, KRAS, and STK11) played a dominant role in early invasive LUAD. Although we did not observe different proportions of driver genes between pre-invasive and invasive components, driver mutations have direct effects on different evolution trajectories. A greater proportion of C>G transversions was found in invasive components than in pre-invasive components, which indicated potential differences in mutation signatures.

Evolution is always branched23,24, and our results demonstrated that pre-invasive and adjacent invasive LUAD arose from branching evolution in 62% (31 in 50) of MPN samples (EM1 and EM2A). As expected, 19 MPNs (EM2B) demonstrated the linear evolution model, which suggests a canonical early invasive progression of the stepwise process from preneoplasia to IAC5. To the best of our knowledge, invasive progression in a single lesion was never investigated. Performing a thorough phylogenetic analysis within the MPN is important to demonstrate the evolutionary process from pre-invasive to invasive LUAD. Based on the micro-dissection, we investigated genomic relationships between pre-invasive and invasive components in one MPN. Previous reports revealed significant ITH in AAH/AIS, and the results implied a trend of branched evolution10,25. The results of the present study indicated that pre-invasive and invasive components were mostly evolutionary results of branched evolution, which support the findings of the previous studies10,22. Additionally, we noted that either pre-invasive or invasive branch was not detected in JSCH P38 and P49, which suggests that our approach could not detect additional differences, such as rare genetic events, epigenetic alterations, and tumor microenvironment infiltration11. All of these findings indicated a high complexity of invasive progression in early stage LUAD.

Notably, the EGFR dual hotspot variants were found in MPNs JSCH P33-1 and P33-2 of EM1. These findings revealed that dual EGFR hotspot mutations derived from pre-invasive and invasive components separately in early invasive LUAD, which may explain the biology of this rare EGFR mutation distribution26. Approximately 80% (36 in 45) of trunks in EM2 contained EGFR exons 19, 20, and 21 variants (Fig. 3a), suggesting a dominant role of EGFR variants in LUAD initiation. In addition to high mutation frequency, tumor clones harboring EGFR mutations interacted with the tumor microenvironment21, even in AAH10. Truncal EGFR mutations exhibited significantly lower mutation abundance in the invasive component compared to the pre-invasive component within the same MPN. According to the analysis results, we hypothesized that tumor ancestors harboring EGFR mutations would undergo negative selective pressure from B cell infiltration during the acquisition of invasiveness. We suppose that indeterminate B-cell-derived cytokines contribute to this biological process27. Furthermore, this tumor microenvironment cross-talk may provide an explanation for the inefficiency in detecting EGFR mutations in cfDNA samples in this T1 stage cohort.

Our research results serve to elucidate the relationship among genetic heterogeneity, tumor evolution, and long-term prognosis in early invasive LUAD. The major limitation of this study was the hotspot sequencing method, which limited the depiction of comprehensive genomic alterations. Whole exome or genome sequencing and a larger sample size in micro-dissection are needed for follow-up research. Importantly, the mechanism of evolutionary selection during the acquisition of invasiveness warrants further research.

Methods

Patient samples and study design

Patients enrolled in this study belonged to a cohort study (A Non-Interventional Systematic Study for the NSCLC Tempo-spatial Heterogeneity; ChiCTR1900022521, http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=34204)28. Fifty-three cases were pathologically confirmed as T1 stage LUAD with MPN ≤ 3 cm (American Joint Committee on Cancer, AJCC, 8th edition; clinical data available in Supplementary Data 1). Two pathologists identified and reviewed all patient samples to characterize the histopathological features, and a total of 61 MPNs were micro-dissected under the stereomicroscope to separate pre-invasive and invasive components. The Institutional Review Board of JSCH approved the study, and all the patients provided written informed consent.

In the phase 1 study, 80 specimens of the first 18 cases were subjected to wide panel-genomic sequencing (pan-cancer 1021-gene panel, Geneplus Technology Inc.) at the coverage depth of 1800×. In the phase 2 study, 125 specimens of 35 cases were subjected to hotspot panel-genomic sequencing (GeneseeqOneTM pan-cancer 425-gene panel, Geneseeq Technology Inc.) at the coverage depth of 1500×. Finally, a total of 126 tissue samples and 41 prior-operation and 38 post-operation cfDNA samples from 53 patients were included in the analysis (Supplementary Data 2). We integrated the clinical data and the Snapshot mutation data from the BLCS cohort (https://sites.sph.harvard.edu/blcs/), who were primarily recruited in Massachusetts General Hospital and enrolled a total of 496 T1N0M0 stage LUAD patients for further prognosis analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1a; Supplementary Data 7). TCGA data were queried from the GDC data portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov)29.

Targeted next-generation sequencing and data processing

DNA from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of the same patients served as a germline DNA reference. Peripheral blood (5–10 mL) was collected from each patient in EDTA-coated tubes (BD Biosciences). Plasma was extracted within 2 h of blood collection and shipped to the central testing laboratory within 48 h. Genomic DNA from FFPE sections or biopsy samples and whole blood samples were extracted with a QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue kit and DNeasy Blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, USA), respectively. Circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from plasma was extracted using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid kit (Qiagen). Sequencing libraries were prepared using the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (KAPA Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for different sample types. The target-enriched library was then sequenced on the HiSeq4000 NGS platform (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In brief, Trimmomatic30 (v0.36) was used for FASTQ file quality control. Paired-end reads were then aligned to the reference human genome GRCh37 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/) using the Burrows–Wheeler aligner (BWA)31. PCR deduplication was performed using Picard, and local realignment around indels and base quality score recalibration were performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK v3.2)32. Furthermore, somatic single nucleotide variant (SNV) and insertion/deletions (INDELs) calling was performed using the Mutect2 mode of GATK. All mutations were manually inspected using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV)33.

Determination of copy number variation (CNV)

CNV analysis was performed using Control-FREEC34, which indicated CNV gain or loss for genes within panel coverage. Sequenza35 (v2.1.2) was used to estimate the total copy number (CNt) and allele-specific copy number (CNA and CNB) profiles in the gene locus, then we defined the high genomic amplification (CNt ≥ 6)36 and gene loss (CNt = 0). TSGs were defined according to previous reports37, and LOH events (CNB = 0) were screened for TSGs38. The results are shown in Supplementary Data 5 and 6.

Construction of phylogenetic tree and determination of driver events

We derived phylogenies for each set of micro-dissected MPNs using Treeomics (v1.8.1)39 to estimate the truncal and branching alterations. Each phylogeny was rooted at the pre-invasive and adjacent invasive components using the Treeomics algorithm, which used the Bayesian inference model and determined the probability that a variant was either present or absent. The somatic alterations were considered truncal events when the present probabilities in two components were both >99.9%, and the somatic alterations with present probabilities >99.9% in only one component were identified as branching events. In addition, mutations with low variant allele frequency (VAF) would be excluded during phylogenetic processing for a low level of confidence. The driver alterations in trunk and branches were annotated and adjusted using driver gene and Cancer Gene Census (v84) annotation parameters within the Treeomics program.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)

To analyze inflammatory infiltration in the TCGA cohort, we queried gene expression data from the GDC data portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov)29. Then we applied the tumor immune cell deconvolution method TIMER40 to predict TILs. Six types of immune infiltrates were estimated (B cell, CD4+ T cell, CD8+ T cell, neutrophil, macrophage, and dendritic cell), and B cells and T cells were considered into further analyses. Immunohistochemistry was used to validate the infiltration of B cells and T cells using the expression of CD20 (M075501; Dako, CA, USA) and CD3 (A045201; Dako, CA, USA), respectively. Truncal EGFR-mutated cases were selected to test B cell and T cell infiltration in the preinvasive and invasive components of MPN, and two pathologists independently estimated the results. The final results are presented as the median number of tumor-infiltrating cells in the three randomly selected hotspot areas.

ITH and dN/dS estimation

We estimated the ITH using the mutant-allele tumor heterogeneity (MATH) method41. The MATH score was calculated using the formula , where VAFi is a vector of the VAF of all mutations from sample i and median absolute deviation (MAD) was denoted. A constant factor (1.4826) was used to scale MAD such that the expected MAD of a sample from a normal distribution equaled the standard deviation. To estimate the selective pressure in each group, dndscv (https://github.com/im3sanger/dndscv)42 was used to compute the relative ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous mutations (dN/dS ratio), and the calculation was only used full-length covered genes within panels.

Oncogenic signaling pathway annotation and mutually exclusive analysis

According to the previous study43, somatic alterations in tumors were classified into canonical pathways, RTK-RAS, TP53, PI-3-kinase/Akt, SWI-SNF, cell cycle, Nrf2, β-catenin/Wnt, Notch, and Myc, to reveal the potential mechanisms and patterns of truncal and branching mutations. To distinguish among recurrent driver alterations, mutually exclusive analysis was performed separately on truncal driver variations in the JSCH cohort, and driver mutations in BLCS and TCGA cohorts. Pair-wise Fisher’s exact test was used in the “somaticInteractions” function of R package Maftools44.

Statistical analysis and figures

Statistical analyses were performed using R (v3.5.1). For comparisons of continuous variables between groups, Mann–Whitney U tests and Kruskal–Wallis H tests were used. For comparisons of categorical variables between groups, chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests were employed. To compare survival between groups, we used the log-rank test. All reported P values were two-sided. The differences were considered significant when the P value was <0.05. Other figures were generated using the R package ggplot2 and RColorBrewer.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jiangsu Cancer Hospital and all the other participating institutions. This work was supported by Key Project of Cutting-edge Clinical Technology of Jiangsu Province (BE2016797), National Science Foundation of China (81872378, 81672295, 81572261, 81501977), NIH (NCI) grant (U01CA209414), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M640465), and the Project of Jiangsu Provincial Medical Talent (ZDRCA2016033).

Author contributions

R.Y., H.S., and L.X. initiated, conceived, and supervised the study. S.W. performed bioinformatics and statistical analysis with M.D., W.X., Q.Y., Y.W. and C.W., and drafted the manuscript with M.D., J.Z., and R.Y. W.X. performed the panel-genomic sequencing with J.W., Y.G. and X.W. J.Z. conducted immunohistochemistry analysis with W.X. and H.Z. J.Z., M.L., D.C.C. and L.X. contributed pathology assessment and/or samples. W.X., Z.H., and D.C.C. proofed the manuscript.

Data availability

The sequencing data reported in the study have been deposited in the EGA database as EGAD00001006457. The data is deposited under controlled access for access to the data contact Dr. Rong Yin, rong_yin@njmu.edu.cn. Data that support the findings of this study are available from BLCS (https://sites.sph.harvard.edu/blcs/) and TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov). All the other data supporting the findings of this study are available within supplementary files and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Siwei Wang, Mulong Du, Jingyuan Zhang, Weizhang Xu.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-19855-x.

References

- 1.Bray F, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Church TR, et al. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1980–1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okami J, et al. Demographics, safety and quality, and prognostic information in both the seventh and eighth editions of the TNM Classification in 18,973 surgical cases of the Japanese Joint Committee of Lung Cancer Registry Database in 2010. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019;14:212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi M, et al. Tumor invasiveness as defined by the newly proposed IASLC/ATS/ERS classification has prognostic significance for pathologic stage IA lung adenocarcinoma and can be predicted by radiologic parameters. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014;147:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travis WD, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Classification of Lung Adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011;6:244–285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kameda K, et al. Implications of the Eighth Edition of the TNM proposal: invasive versus total tumor size for the T descriptor in pathologic stage I-IIA lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018;13:1919–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsutani Y, et al. High-risk factors for recurrence of Stage I lung adenocarcinoma: follow-up data from JCOG0201. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2019;108:1484–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teixeira VH, et al. Deciphering the genomic, epigenomic, and transcriptomic landscapes of pre-invasive lung cancer lesions. Nat. Med. 2019;25:517–525. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0323-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu X, et al. Multi-region exome sequencing reveals genomic evolution from preneoplasia to lung adenocarcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2978. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10877-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sivakumar S, et al. Genomic landscape of atypical adenomatous hyperplasia reveals divergent modes to lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017;77:6119–6130. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qian J, et al. Genomic underpinnings of tumor behavior in in situ and early lung adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019;201:697–706. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201902-0294OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H, et al. Genomic and immune profiling of pre-invasive lung adenocarcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07882-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, et al. Genomic landscape and immune microenvironment features of preinvasive and early invasive lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019;14:1912–1923. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izar B, et al. The impact of EGFR mutation status on outcomes in patients with resected stage I non-small cell lung cancers. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013;96:962–968. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Onozato R, Kuwano H, Mitsudomi T. Prognostic implication of EGFR, KRAS, and TP53 gene mutations in a large cohort of Japanese patients with surgically treated lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009;4:22–29. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181914111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marks JL, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic implications of EGFR and KRAS mutations in resected lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2008;3:111–116. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318160c607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unni AM, Lockwood WW, Zejnullahu K, Lee-Lin S-Q, Varmus H. Evidence that synthetic lethality underlies the mutual exclusivity of oncogenic KRAS and EGFR mutations in lung adenocarcinoma. Elife. 2015;4:e06907. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turajlic S, Sottoriva A, Graham T, Swanton C. Resolving genetic heterogeneity in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019;20:404–416. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The I, of Whole TP-CA, Consortium G. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature. 2020;578:82. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang C, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals genomic signatures associated with the inflammatory microenvironments in Chinese NSCLC patients. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2054. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04492-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izumchenko E, et al. Targeted sequencing reveals clonal genetic changes in the progression of early lung neoplasms and paired circulating DNA. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8258. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turajlic S, Sottoriva A, Graham T, Swanton C. Resolving genetic heterogeneity in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019;20:404–416. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch M, et al. Genetic drift, selection and the evolution of the mutation rate. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016;17:704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, et al. Comprehensive analysis of EGFR-mutant abundance and its effect on efficacy of EGFR TKIs in advanced NSCLC with EGFR mutations. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017;12:1388–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yatabe Y, Matsuo K, Mitsudomi T. Heterogeneous distribution of EGFR mutations is extremely rare in lung adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:2972–2977. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorusso G, Rüegg C. The tumor microenvironment and its contribution to tumor evolution toward metastasis. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2008;130:1091–1103. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang S, et al. The spatiotemporal evolution of early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019;37:8539–8539. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.8539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature511, 543–550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boeva V, et al. Control-FREEC: a tool for assessing copy number and allelic content using next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2011;28:423–425. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Favero F, et al. Sequenza: allele-specific copy number and mutation profiles from tumor sequencing data. Ann. Oncol. 2015;26:64–70. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohshima K, et al. Integrated analysis of gene expression and copy number identified potential cancer driver genes with amplification-dependent overexpression in 1,454 solid tumors. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:641. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00219-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris LG, Chan TA. Therapeutic targeting of tumor suppressor genes. Cancer. 2015;121:1357–1368. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maxwell KN, et al. BRCA locus-specific loss of heterozygosity in germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:319. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00388-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reiter JG, et al. Reconstructing metastatic seeding patterns of human cancers. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14114. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li B, et al. Comprehensive analyses of tumor immunity: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Genome Biol. 2016;17:174. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mroz EA, Rocco JW. MATH, a novel measure of intratumor genetic heterogeneity, is high in poor-outcome classes of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martincorena I, et al. Universal patterns of selection in cancer and somatic tissues. Cell. 2018;173:1823. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanchez-Vega F, et al. Oncogenic signaling pathways in the cancer Genome Atlas. Cell. 2018;173:321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayakonda A, Lin D-C, Assenov Y, Plass C, Koeffler HP. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 2018;28:1747–1756. doi: 10.1101/gr.239244.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data reported in the study have been deposited in the EGA database as EGAD00001006457. The data is deposited under controlled access for access to the data contact Dr. Rong Yin, rong_yin@njmu.edu.cn. Data that support the findings of this study are available from BLCS (https://sites.sph.harvard.edu/blcs/) and TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov). All the other data supporting the findings of this study are available within supplementary files and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.