Abstract

Helleborus cyclophyllus Boiss is a rhizomatous plant species, with strong allelochemical properties, that has been used since ancient times for its therapeutic properties. In the present study we investigated the ability of an aqueous-soluble fraction of the methanol extract of H. cyclophyllus Boiss leaves, to induce apoptotic cell death on A549 human bronchial epithelial adenocarcinoma cells. A primary human lung fibroblasts’ cell line was used as a model of normal-healthy cells for comparison. Cell morphology was examined after appropriate staining, cytotoxic activity of the extract was determined by the MTT assay, the type of cell death was analyzed by flow cytometry, confirmation of apoptosis was evaluated with the analysis of caspase-3, PARP1 by western blotting, while the chemical composition was assessed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). H. cyclophyllus Boiss extract was selectively active on A549 cells inducing significant morphological changes, even at low concentrations. Characteristic morphological alterations included the release of vesicular formations from A549 cell membranes (ectosomes), detachment of cells from their substrate, generation of a large vesicle into the cytoplasm (thanatosome) and the formation of apoptotic bodies. The selective apoptotic action on treated cells was also confirmed by biochemical criteria. Low concentrations, however, did not affect normal cells. The phytochemical analysis of the extract revealed the presence of cardiac glucosides, bufadienolides and phytoecdysteroids. To the best of our knowledge, the above-mentioned sequences of events leading selectively cancer cells to apoptosis, has not been reported before.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10616-020-00425-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Helleborus cyclophyllus, Apoptosis, Thanatosomes, Caspase-3, PARP1, A549

Introduction

Cancer is one of the major health problems in developed countries. Tumors are characterized by an abnormal increase of cell proliferation. This phenomenon may be due to loss of growth control, possibly accompanied with loss of differentiation. Target of a successful chemotherapy is the selective elimination of cancer cells without serious side effects for the patient.

The plant kingdom has been an attractive source of new anticancer drugs (Pan et al. 2012). About 50% of anticancer drugs are natural products which are directly derived from them or are semi-synthetical modified natural products (Newman and Cragg 2007). Due to the development of drug resistance and to the side effects caused by commonly used chemotherapeutic drugs, nowadays the discovery of anticancer agents derived from natural sources has become increasingly popular (Faraone et al. 2020). The natural products offer more opportunities for discovery of new active substances with antitumor activity due to their greater diversity compared to those produced by combinatorial chemistry (Harvey 2000).

The genus Helleborus (Ranunculaceae) includes approximately 20 perennial, herbaceous, rhizomatous species, which are distributed in different regions of Europe and Asia (Tutin et al. 1993). H. cyclophyllus Boiss grown in rocky and shady mountains in Greece is locally known as “skarfi”. Τhis species, whose distribution is restricted in Balkans, was known for its therapeutic properties since ancient times. Rhetoricians and politicians used it to improve their memory and to strengthen their voice and until the end of the nineteenth century it was used in the treatment of mania (Maior and Dobrotă 2013). In the folk medicine in the region of Zagori (Northwesten Greece, Epirus) it was used for treating liver and skin diseases, against tooth ache and as anthelminthic (Vokou et al. 1993). According to recent studies, fractionated extracts from H. cyclophyllus were found to have antitumor potential (Lindholm et al. 2002), although the mechanism of action and specificity is still unclear. Also, other species of the genus Helleborus as H. purpurascens (Segneanu et al. 2015), H. niger (Schink et al. 2015), H. caucasicus (Martuciello et al. 2018) were investigated for their biological activities and found to possess anticancer properties. The chemical analysis of extracts derived from Hellebore plants has shown that they are characterized by the presence of alkaloids, steroidal saponins bufodienolides, phytoecdysones (Rosselli et al. 2009; Stochmal et al. 2010; Maior and Dobrotă 2013).

The aim of the study was to investigate the characteristics and the possible selectivity of the anticancer activity of H. cyclophyllus leaves on cancer cells. In this regard, we compared the effects on A549 human bronchial epithelial adenocarcinoma with those on normal human lung fibroblasts cell lines. We examined the morphological changes and the type of cell death that was induced, through biochemical and morphological criteria.

Materials and methods

Plant material and preparation of methanol extract

Wild grown plants were located on mount Xyrovouni (Epirus, Greece) at 1100 m altitude. The identification was conducted at the flowering stage according to Flora Europaea Asia (Tutin et al. 1993). A voucher specimen (Νο 28031001) has been deposited in the Herbarium of the Department of Agriculture, University of Ioannina, Greece. Leaves were collected on September, the plant material was lyophilized, pulverized and extracted with methanol after sonication, as previously described (Yfanti et al. 2015).

Cell cultures

A549 cell line (ATCC CCL-185) was used as a model of cancer cells, while a primary human lung fibroblasts’ cell line (PHLF) was used as a normal cells’ control. The cells were cultured in Ham’s F-12K medium (Gibco) and DMEM (Gibco) respectively in 5% (v/v) CO2 incubator set at 37 °C (Yfanti et al. 2015).

Preparation of treatment solutions

Portions from the green colored stock methanol extract, 100 mg dry weight (dw) mL−1, were successively diluted with methanol to achieve the desired concentrations. Equal volumes of methanolic solutions were added to the Petri dishes, methanol was evaporated under N2 at 40 °C and the residue was re-dissolved with Ham’s F-12K or DMEM serum free, to achieve concentrations of 0.010, 0.015, 0.020, 0.040, 0.050, 0.080, 0.10, 0.50, 0.60, 1.00, 3.00 and 6.00 mg dw mL−1. Negative control samples, without H. cyclophyllus extract, prepared under the same conditions were included in the study.

Cytotoxic activity

The cytotoxic effect of H. cyclophyllus leaves extract on A549 cancer cells and PHLF was determined using the MTT assay (Mosmann 1983). Before seeding cells into the wells, the trypan blue cell counting method was used in order to determine the number of living cells per mL of medium. A549 and PHLF cells (1 × 104/well in 96 well culture plate) were treated with the following concentrations: 0, 0.010, 0.015, 0.020, 0.050, 0.10, 0.60 mg dw mL−1 for A549 and 0.02, 0.04, 0.08, 0.10, 0.50, 0.60 mg dw mL−1 for PHLF. Briefly, cells were left overnight to adhere and then they were treated with the above extract concentrations. Subsequently, incubation followed with 10 µL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), 5 mg mL−1 in PBS (final concentration 0.5 mg mL−1), for 4 h. After that, the medium was carefully removed, 100 µL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were added to each well and the plates were shaken to dissolve the formazan crystals, while the absorbance was measured at 540 nm by an ELISA plate reader (Lambda E, MWG Biotech, Germany). Untreated control cell samples and samples without cells were used as negative controls. Each concentration test was repeated 4 times. Cell viability was expressed as percentage of the control after subtraction of blank absorbance. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for A549 cancer cells was determined from the dose–response curve.

Flow cytometric analysis

For the flow cytometric analysis, A549 cancer cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells on 55-mm culture dishes in F-12 K medium, while lung fibroblasts at a density of 2 × 105 cells on 20-mm 6-well plates in DMEM. The cells were left to reach 80% of confluence and then incubated for 24 h with concentrations of plant extract (0, 0.010, 0.015, 0.020, 0.050 mg mL−1 for A549 and 0, 0.10, and 0.60 mg mL−1 for PHLF) in serum-free medium. After treatment, cells were observed with an inverted microscope and prepared for flow cytometric analysis as previously described (Yfanti et al. 2015). Propidium iodide (PI) and annexin-V FITC (Pharmingen detection kit) were used to determine apoptotic, necrotic and living cells, by a FACS flow cytometry (Accuri C6 plus, Becton Dickinson).

Western blot analysis

After treatment with the various H. cyclophyllus Boiss concentrations, cells were harvested by a cell scraper, centrifuged at 1.500×g for 10 min and washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The supernatant was discarded, while the pellet was resuspended into 250 µL radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing freshly-prepared protease inhibitors and centrifuged in a refrigerated centrifuge at 11,260×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was stored at − 80 °C. After protein determination by Bradford assay, analysis of procaspase-3 and PARP1 was performed by western blotting, as described (Yfanti et al. 2015). In brief for the separation of procaspase-3 and PARP-1, 15% and 8% polyacrylamide gel were used, respectively. Αnti-caspase-3 (Santa Cruz, USA), anti-PARP1 (Santa Cruz, USA) and anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz, USA) were applied as primary antibodies, at a 1:500 dilution. Anti-mouse IgG antibody (Pierce Biotechnology, USA) was used as secondary antibody at a 1:10,000 dilution.

Cell staining for morphological analysis

The effect of H. cyclophyllus Boiss treatment solutions on the morphology of A549 cells and PHLF was observed microscopically after appropriate staining. In particular, after treatment, cells were collected by trypsinization, washed with cold PBS, centrifuged at 1100×g for 5 min. The cell pellet was suspended in the drop remaining after discarding the supernatant and spread over a microscopic slide. The smear was allowed to dry in air. Haematoxylin–eosin and DAPI staining were performed as described earlier (Yfanti et al. 2015). For May–Grűnwald Giemsa staining, a few drops of May Grűnwald (Merck) solution were applied to the slide with the dry cell smear. After 3 min, an equal amount of water was added, and the dye–water mixture was allowed to act for 1 min. The mixture was discarded and replaced until complete coverage with Giemsa staining solution (Merck) (4 drops Giemsa in 2 mL of water), for 5 min. After washing with water, the stained cells were covered with a coverslip using DPX mountant (Atom Scientific). For oil red O staining the slides with the dry cell smear were placed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde (Panreac) for 30 min, washed with dd H2O and covered with isopropanol (Sigma-Aldrich) 60% for 2–5 min. Then, isopropanol was removed, cells were stained with oil red O (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min, washed with warm water and prepared for observation under light microscope. For Papanikolaou staining the dry cell smear was fixed in 95% ethanol for 30 min, hydrated through consecutive concentrations of ethanol solutions 80%, 70%, 50%, washed by dd H2O and immersed in haematoxylin solution (Atom Scientific) for 5 min. After washing with dd H2O, the slides were immersed in hydrochloric acid solution 1%, washed with water, dehydrated through consecutive concentrations of ethanol solutions, 50%, 70%, 80%, 96%, immersed for 5 min in an Orange G (Atom Scientific) solution, rinsed off in 95% ethanol and stained in ΕΑ 50 (Atom Scientific) for 5 min. Finally, the slides were immersed in 96% ethanol, a 96% ethanol–xylol (1:1, v/v) solution and the cover slip was mounted with DPX mountant (Atom Scientific). Cells stained by haematoxylin–eosin, May–Grűnwald Giemsa, oil red O and Papanikolaou staining (PHLF) were observed using a Nikon Eclipse 50i, Light Microscope and photographed with an adapted digital camera, while cells stained by DAPI were observed by a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse E400, Nikon), equipped with ultraviolet illuminator.

Analysis of H. cyclophyllus Boiss working solution by LC–MS/MS

A portion of the prepared methanol extract was dried under nitrogen stream (N2) at 40 °C and resolved in the same amount of distilled water. The analysis was performed using an ESI-LTQ-ORBITRAP XL unit (Thermo Scientific, Germany). The Orbitrap Unit was operated in positive and negative mode, with a spay voltage of 3.7 and 2.8 kV respectively. The capillary voltage and the tube lens voltage were set to 30 and 110 V for positive polarity and to − 30 and − 120 V for negative polarity, respectively. The scan ranged from m/z 1500 up to 1500. For fragmentation study, a data-dependent scan was performed. The normalized collision energy of the Collision-Induced Dissociation was set to 35 eV. Separations were performed on Hypersil Gold-C18 column, 150 × 2.1 mm, 5 µm (Thermo Scientific, Germany). The mobile phase consisted of (A) 0.1% formic acid, 5 mM ammonium formate in water and (B) 0.1% formic acid, 5 mM ammonium formate in methanol. The gradient was 0 min: 95%A; 0–10 min: 0%A; 10–12 min: 0%A; 12–15 min: 95%A. The flow-rate was adjusted to 450 µL min−1, the oven temperature was set to 27 °C and the injection volume was 10 µL. Data processing for high-resolution MS and MSn were carried out using the Xcalibur software (version 2.1.0-Thermo Scientific) and commercially available software’s.

Statistical analysis

The flow cytometric and the cytotoxicity assay results were expressed as mean ± standard error of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis of data was performed using oneway Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni and Dunnett’s post hoc test for flow cytometry and the MTT, respectively. The significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Morphological alterations caused by H. cyclophyllus extract

A549 cancer cells

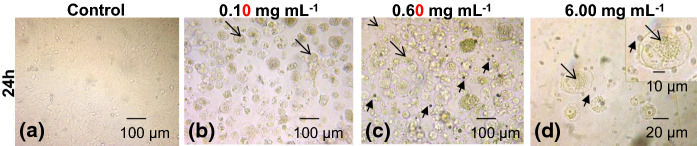

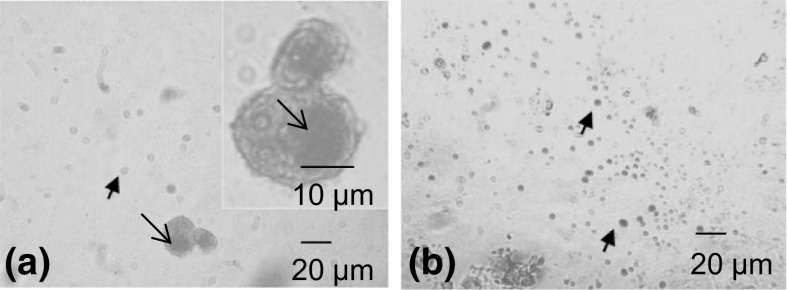

A549 cancer cells were initially examined by phase contrast microscopy. Control A549 cells showed a typical polygonal shape and intact appearance (Fig. 1a). After incubation with H. cyclophyllus Boiss extract for 24 h, a high percentage of the cells was detached after treatment with all the concentrations of H. cyclophyllus Boiss extracts applied, (0.10, 0.60 and 6.00 mg mL−1), floated in the medium and were characterized by a swollen round shape (Fig. 1b–d). Moreover, green colored ingredients, probably related to the plant extract, were gathered into a spherical vesicular area located next to the nucleus, as shown in magnification in Fig. 1d. Apart from cells with the above characteristics, small-sized round green-colored extracellular vesicles appeared in the supernatants (Fig. 1c, d). Oil red O staining showed that the large intracellular vesicle in the treated cells as well as the extracellular micro vesicles isolated from the cell supernatants after 4 h of exposure to 6.00 mg mL−1, were positively stained by Oil red O (Fig. 2a, b). These data indicate that plant extract ingredients possibly penetrated into the cell cytoplasm, without evident rapture of the membrane.

Fig. 1.

Effect of H. cyclophyllus leaves extract on A549 cancer cells morphology in dose-dependent experiments (0, 0.60 and 6.00 mg dw mL−1), 24 h after treatment of confluent A549 cells. Cells were observed with an inverted microscope (a–c ×100, d ×400 magnification) (A. Krüssoptronic, Germany): a untreated control cells; b 0.10 mg mL−1; c 6.00 mg mL; d 0.60 mg mL−1. Arrows ( ) indicate the formation of small sized of round particles (ectosomes); Arrows (

) indicate the formation of small sized of round particles (ectosomes); Arrows ( ) indicate the formation of a large vesicle (thanatosome) into the cytoplasm

) indicate the formation of a large vesicle (thanatosome) into the cytoplasm

Fig. 2.

Oil red O staining of A549 cancer cells after treatment with H. cyclophyllus leaves extract. Representative pictures of: a A549 cells, (0.60 mg mL−1, 24 h); b vesicles isolated by centrifugation from the supernatant of A549 cells treated with 6.00 mg mL−1 for 4 h, as observed by inverted microscope (magnification ×400). Arrows ( ) indicate the positive oil red O staining of ectosomes; Arrows (

) indicate the positive oil red O staining of ectosomes; Arrows ( ) indicate the positive oil red O staining of the thanatosomes

) indicate the positive oil red O staining of the thanatosomes

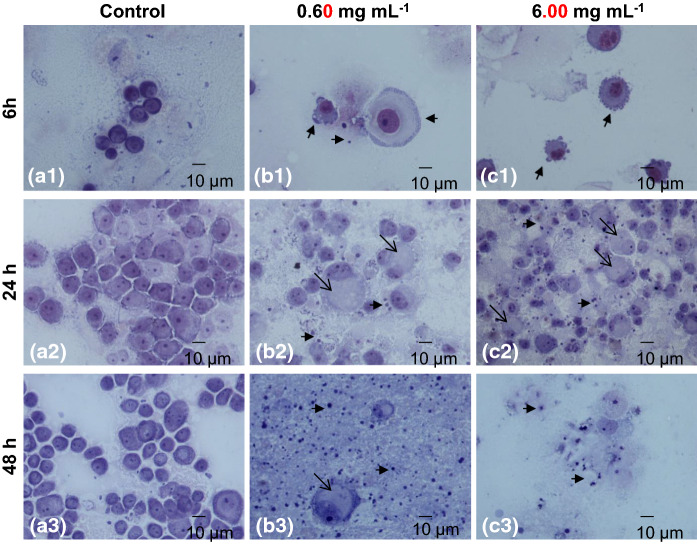

In order to investigate the particular morphology of A549 cancer cells after treatment, time and dose dependent experiments were conducted and treated cells were examined after appropriate staining. At first, A549 cells were treated for 6, 24 and 48 h, in a time-course experiment, with 0.60 and 6.00 mg mL−1 H. cyclophyllus Boiss extracts and stained with May–Grünwald–Giemsa (Fig. 3). After 6 h of exposure, intracellular material, probably from the plant extract was gathered at the periphery of the cell membrane, which was distorted, becoming wavy (ruffled) (Fig. 3b-1). Moreover, this material was finally enclosed in a membrane bilayer and eventually shed to the extracellular space in the form of vesicles (Fig. 3b-1, c-1). At 24 h of exposure, cells presented major morphological alterations. Indeed, a big vesicle was formed into the cell cytoplasm, causing the margination and compression of the nucleus at the periphery of the cell, while the presence of binucleated cells and the formation of apoptotic bodies (Fig. 3b-2, c-2) became apparent. The intracytoplasmic vesicle appeared as a spherical ball and it was homogenously stained. Numerous apoptotic bodies and cell debris were observed after 48 h of exposure (Fig. 3b-3, c-3). Similar results to those observed by May Grünwald staining were obtained with hematoxylin–eosin staining. Representative pictures of hematoxylin–eosin stained A549 cancer cells after time- and dose-dependent experiments are given in Online Resource 1.

Fig. 3.

Effect of H. cyclophyllus leaves extract on A549 cancer cells in dose- (0, 0.60 and 6.00 mg dw mL−1) and time-dependent (for 6, 24, 48 h) experiments. Cells were stained with May–Grünwald Giemsa staining and observed with an optical microscope (Nikon eclipse 50i), at ×600 magnification. Representative pictures of Α549 cancer cells morphological changes were obtained from 3 independent experiments after treatment with H. cyclophyllus leaves extract: a-1, a-2, a-3, untreated control cells; b-1, b-2, b-3, 0.60 mg mL−1; c-1, c-2, c-3), 6.00 mg mL−1 after 6, 24, 48 h respectively. Arrow ( ) indicates the wavy cell membrane of treated A549 cancer cells and gathered intracellular material at the periphery of the cell; Arrows (

) indicates the wavy cell membrane of treated A549 cancer cells and gathered intracellular material at the periphery of the cell; Arrows ( ) indicate the formation of ectosomes; Arrows (

) indicate the formation of ectosomes; Arrows ( ) indicate the formation of thanatosome; Arrows (

) indicate the formation of thanatosome; Arrows ( ) indicate the formation of apoptotic bodies

) indicate the formation of apoptotic bodies

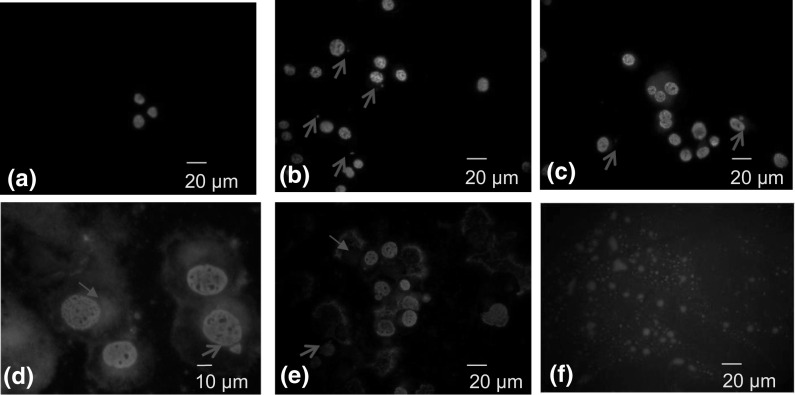

Finally, an insight into the nucleus morphology was achieved after DAPI staining. Control A549 cells comprised homogenously stained nuclei with a less bright blue color compared to cells treated with H. cyclophyllus Boiss extracts (Fig. 4a). However, nuclear condensation and fragmentation was observed after 6 h of A549 cell treatment with 0.10 mg mL−1 in a few cells (Fig. 4b). The formation of micronuclei was also observed after exposure to 0.60 and 6.00 mg mL−1, (Fig. 4c, d, respectively), for 12 h. These morphological changes are compatible with apoptosis. Furthermore, at the above concentrations, two or even three nuclei of various sizes were observed in a number of cells. However, after longer exposure (24 h) to 6.00 mg mL−1, some nuclei of semilunar shape appeared emarginated at the periphery of the cell, while in others, the nuclear membrane was destroyed and the nuclear content was shed at the surrounding cytoplasm (Fig. 4e). This morphology was compatible with karyolysis. It is worth mentioning that ingredients of the extract exhibited red fluorescence emission under the fluorescence microscope (Fig. 4f). This material was incorporated into the cell cytoplasm and was accumulated in a region next to the nucleus (Fig. 4d) forming a large vesicle which was referred above as a spherical ball.

Fig. 4.

Effect of H. cycloplyllus leaves extract on the nuclear morphology of A549 cells in dose- (0, 0.10, 0.60 and 6.00 mg dw mL−1) and time-dependent (for 6, 12, 24 h) experiments. Cells were stained with DAPI and observed by fluorescent microscopy: a–c, e, magnification ×400; d magnification ×600. Representative pictures were obtained from 3 independent experiments. A549 cells were incubated: a in the absence or in the presence of; b 0.10 mg mL−1 for 6 h; c 0.60 mg mL−1 for 12 h; d 6.00 mg mL−1 for 12 h; e 6.00 mg mL−1 for 24 h; f MeOH dried extract. Arrows ( ) indicate the formation of micronuclei; Arrows (

) indicate the formation of micronuclei; Arrows ( ) indicate the formation of thanatosome

) indicate the formation of thanatosome

Primary human lung fibroblasts (PHLF)

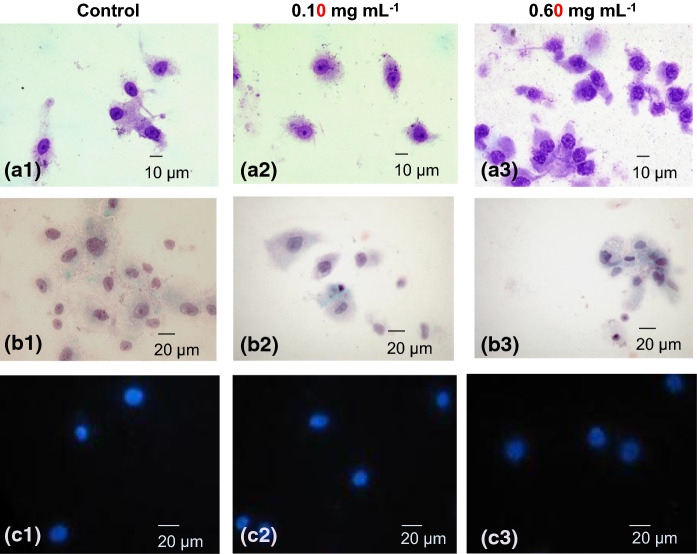

The effect of H. cyclophyllus Boiss extract on PHLF morphology was quite different from the effects on A549 cancer cells. A macroscopic difference was that after treatment, the PHLF preparation did not adopt high viscosity. Control cells (Fig. 5a-1, b-1, c-1) and cells treated with 0.10 mg mL−1 presented a normal morphology after staining with May–Grünwald–Giemsa (Fig. 5a-2), Papanikolaou (Fig. 5b-2) and DAPI staining (Fig. 5c-2). However, at a concentration of 0.60 mg mL−1, the morphology was affected, accompanied by granulation and blurring of the nuclear membrane (Fig. 5a-3, b-3, c-3), indicating an effect on PHLF viability without inducing apoptosis.

Fig. 5.

Effect of H. cyclophyllus extracts on the morphology of lung fibroblasts and their nuclei. Representative pictures (triplicate experiment) of various staining conditions (0–0.10–0.60 mg mL−1, 24 h): a-1 control, a-2, a-3, after May–Grünwald–Giemsa staining; b-1, control, b-2, b-3 after Papanikolaou staining; c-1, control; c-2, c-3 after nuclear DAPI staining. Stained cells with May–Grünwald–Giemsa and Papanikolaou were observed with an optical microscope, cells stained with DAPI were observed by fluorescent microscopy

Determination of cell cytotoxicity by MTT assay

Our results showed that A549 cancer cells viability was significantly affected by all the concentrations tested in comparison to the untreated control cells (p ≤ 0.000). Treatment with different concentrations of the extract showed a significantly high cytotoxicity (> 97%) even at the lowest concentration tested (> 0.020 mg mL−1). Figure 6a shows the effect of the extract on A549 cancer cells viability revealing an IC50 value of 0.014 mg mL−1. In contrast, the viability of normal cells (PHLF) treated for 24 h with concentrations from 0.020 to 0.100 mg mL− 1 did not show any difference compared with the untreated control cells (95–91% respectively, p = 1.000). Higher concentrations (0.50 and 0.60 mg mL−1) were found to reduce the viability of normal cells compared to the control (80%, 76% respectively, p < 0.005). It is worth mentioning that the early apoptotic cells were not taken into account with the MTT technique applied in our experiments.

Fig. 6.

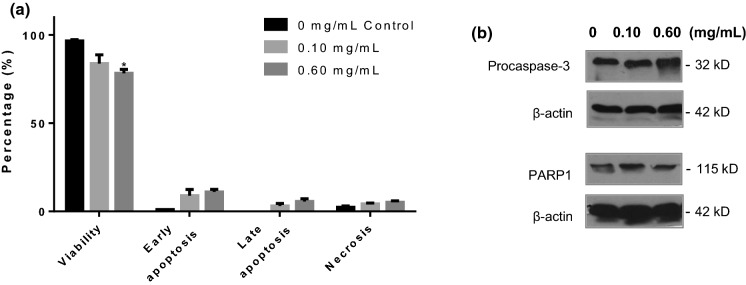

A549 cancer cells apoptosis after treatment with H. cyclophyllus methanol leaves extracts, a diagram of cytotoxic effect and dose–response curve (MTT assay) after 24 h of exposure to concentrations 0, 0.010, 0.015, 0.020, 0.050, 0.10 and 0.60 mg/mL. The mean values ± SE were calculated from three independent experiments (*p < 0.05), while the IC 50 value was determined by the log of µg/mL H. cycllophylus concentration, versus normalized response variable slope, using GraphPad software; b diagram and representative histograms of the type of cell death and apoptotic rates determined by flow cytometry in dose-response experiments using 0, 0.010, 0.015 and 0.020 mg/mL for 24 h. The cell death was classified into Early Apoptosis (Annexin V+, PI−), Late Apoptosis (Annexin V+, PI+), Necrosis (Annexin V−, PI+). The mean values ± SE were calculated from three independent experiments (*p < 0.05); c representative western blots show the decrease in procaspase-3 levels with increasing concentrations of the plant extract and the cleavage of PARP1, after 24 h of exposure at concentrations 0, 0.10 and 0.60 mg/mL. Beta-actin (β-actin) was used as a control of equal loading

Determination of cell viability by flow cytometry

In order to determine apoptosis with flow cytometry, cells were collected after trypsinization and centrifugation. As shown in Fig. 6b the flow cytometric results confirm the pro-apoptotic activity of the extracts on a dose dependent manner. In particular, A549 cancer cells exposed to 0.020 mg mL−1, underwent apoptosis at an extremely high percentage (97 ± 1.9%). It must be noted that for concentrations greater than 0.020 mg mL−1, the cell pellet became viscous, sticky and green-colored, rendering the analysis by flow cytometry, impossible. In contrast to A549 cells, flow cytometry was feasible on lung fibroblasts treated with H. cyclophyllus Boiss extracts, since they did not exhibit such morphology. For concentrations greater than 0.10 mg mL−1, the flow cytometric results indicated that the extract affected normal cells (PHLF) (Fig. 7a), by reducing their viability (78.0 ± 2.3%, 0.60 mg mL−1), (p = 0.019), while at 0.1 mg mL−1 the effect was not significant (84.0 ± 4.9%, p = 0.312).

Fig. 7.

Effect of H. cyclophyllus leaves extracts on Primary Human Lung Fibroblasts (normal cells): a diagram of the cells viability as analyzed by flow cytometry, after treatment with 0, 0.10 and 0.60 mg/mL for 24 h. Mean values ± SE from 3 independent experiments are shown (*p < 0.05); b representative western blots show unchanged procaspase-3 levels and intact PARP1 signals. Beta-actin (β-actin) was used as a control of equal loading

Investigation of cell death by Western blotting analysis

When A549 cells were treated with various concentrations of H. cyclophyllus Boiss extracts (0.10 and 0.60 mg mL−1), a significant, dose-dependent decrease in the signal of pro-caspase-3, compared to the control was observed (Fig. 6c), indicating its cleavage to caspase-3, which is an executioner step for apoptosis. On the other hand, PARP1, a downstream preferred substrate of caspase-3, showed a cleavage product after 24 h of treatment, even after treatment with 0.1 mg mL−1 (Fig. 6c). These results are compatible with cell apoptosis. In the control A549 cells, no decrease in procaspase levels or cleavage of PARP1 was observed. On the contrary, when normal PHLF were treated with increasing concentrations of H. cyclophyllus Boiss extracts, (0.10 and 0.60 mg mL−1) for 24 h, no effect on procaspase-3 or PARP1 levels was detected (Fig. 7b).

LC–MS/MS analysis

Having shown a distinct activity of H. cyclophyllus extract on A549 cancer cells compared with the non-cancer PHLF cells, we proceeded with the LC–MS/MS analysis of the working-treatment solution, which corresponded to a water-soluble fraction of the methanol extract, using the Orbitrap High Resolution and Mass accuracy analyzer. Table 1 shows the corresponding retention times, experimental and theoretical mass information and mass error deviation of the proton or sodium adducts of the secondary metabolites identified. For the identification of the metabolites three data points were used, the mass accuracy (for all measurements the mass tolerance error was set to < 5 ppm), the retention time and the MS2 spectra. Representative total and extracted ion chromatograms are given in Online Resource 2.

Table 1.

Corresponding retention times (RT), elemental composition, experimental and theoretical mass information, mass error deviation and double bond and ring equivalent number (RBD) of compounds identified in the water-soluble fraction of the dry methanol extract of H. cyclophyllus leaves

| Compound | RT (min) | Accurate mass | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elemental composition | Experimental | Theoretical | RBD | Error (ppm) | ||

| 2-Deoxy-d-ribono-1,4- lactone | 1.14 | C5H9O4+ | 133.0490 | 133.0495 | 1.5 | − 3.72 |

| 20-Hydroxyecdysone | 6.00 | C27H45O7+ | 481.3152 | 481.3160 | 5.5 | − 1.62 |

| Polypodine b | 5.93 | C27H45O8+ | 497.3095 | 497.3109 | 5.5 | − 2.91 |

| Hellebrin | 6.64 | C36H52O15Na+ | 747.3195 | 747.3198 | 10.5 | − 0.43 |

| Degluco-hellebrin | 6.83 | C30H43O10+ | 563.2840 | 563.2851 | 9.5 | − 1.91 |

| Hellebrigenin | 6.83 | C24H33O6+ | 417.2267 | 417.2272 | 8.5 | − 1.00 |

Discussion

In the present study it was found that the aqueous fraction of the methanol extract obtained by H. cyclophyllus Boiss leaves induces a special sequence of events on A549 cancer cells in vitro and leads them selectively to apoptosis, compared to non-cancer cells. The particular sequence of events includes vesicles formation (ectosomes) and their secretion from the cells, detachment of cells from their substrate, formation of a large vesicle into the cytoplasm, a structure resembling to thanatosome and finally, the formation of apoptotic bodies. The induction of apoptosis was confirmed through the decrease in procaspase-3 levels and cleavage of PARP1. Such effects were not observed in the non-cancer PHLF cultures that were used as normal control cells in our experiments. According to our best knowledge, the above sequence of events leading A549 cells to apoptosis after in vitro treatment with plant extracts and particularly the formation of ectosomes prior to thanatosomes, has not been reported before.

The MTT assay showed that even low concentrations of H. cyclophyllus Boiss extracts affected significantly the viability of Α549 cancer cells in a selective manner, compared with PHLF. These findings are in accordance with Lindholm et al. (2002), who reported that fractions of H. cyclophyllus Boiss extract exhibited a highly selective cytotoxicity on the cancer cells tested, although they did not investigate the mode of action. The flow cytometric analysis indicated that the extract induces apoptosis on treated A549 cancer cells at concentrations lower than 0.020 mg mL−1. The immunoblotting analysis clearly showed the induction of apoptosis on A549 cancer cells by H. cyclophyllus Boiss extracts, based on the reduction of procaspase-3 levels, and the cleavage of PARP1, which indicate the activation of caspase-3 even at higher concentrations, i.e. 0.10 and 0.60 mg mL−1, where flow cytometric analysis was not feasible. Caspase-3, is a cysteine protease, which is normally present in cells as an inactive proenzyme that is activated through a precisely controlled proteolytic cleavage during apoptosis (Boldingh Debernard et al. 2011). Activated caspase-3 is an executioner caspase in apoptosis, which leads downstream to PARP1 cleavage, a nuclear enzyme involved in DNA repair.

Microscopic examination of A549 cancer cells revealed that morphological alterations started appearing a few hours after the exposure to H. cyclophyllus Boiss extract. The first event was membrane blebbing and the formation of vesicles by the cell membrane of cancer cells (ectosomes) (Sadallah et al. 2010), which were released into the extracellular space after 4–6 h treatment. These ectosomes were observed as small round green particles in the supernatants of A549 cancer cells. The morphological evaluation of A549 cancer cells after 24 h of exposure showed that the survived A549 cancer cells stopped secreting ectosomes and were detached from their substrate, adopting a swollen round shape. Moreover, the formation of the large, homogenously stained vesicle in the cytoplasm of the detached cells, that emarginated the cell nucleus at the periphery of the cell, resembles to hyaline globules also known as thanatosomes. Papadimitriou et al. (2000) observed that hyaline globules are formed into cells of different tumors which are located in areas with apoptotic characteristics. These tumor cells presented increased cell membrane permeability and obvious micronuclei formation into the cytoplasm. In order to emphasize on the association of hyaline globules formation with cell death, the authors used the term thanatosomes, which was also adopted by us in this work. Finally, after the formation of thanatosome in the cytoplasm of A549 cancer cells, numerous apoptotic bodies and cell debris appeared. Considering the information obtained by the microscopically observation of treated cells, it seems that the plant-derived ingredients penetrated through the cell membrane into the cytoplasm of cancer cell. At first, the A549 cancer cells shed these constituents outside the cell through the formation of ectosomes, but subsequently these compounds were regained and deposited near the nucleus, formed the thanatosome and the cancer cells were detached from their substrate. Finally, the formation of micronuclei into the cytoplasm of treated A549 cells, as well the numerous apoptotic bodies observed confirms the induction of apoptosis by the extract. This sequence of events has never been reported before, as far as we know.

Apoptosis is an energy dependent process, accomplished within 2 h after induction (Elmore 2007). In the present study, the formation of the majority of apoptotic bodies was observed 48 h after treatment, which means that apoptosis was not induced immediately after exposure to H. cyclophyllus extract. In normal epithelial cells that are detached from their substrate, a specific type of apoptosis, known as anoikis, can occur. This procedure is essential for the maintenance of tissue homeostasis. Cancer cells acquire resistance to anoikis and so they can spread, survive and proliferate at metastatic sites. The fact that the programmed cell death was induced after the detachment of cancer cells from their substrate, indicates that H. cyclophyllus Boiss may render A549 cancer cells sensitive to anoikis.

The chemical analysis of the compounds included in the working water-soluble fraction of the methanol extract revealed the presence of two cardiac glucoside (hellebrin, degluco-hellebrin), a bufadienolide (hellebrigenin), two ecdysones (20-hydroxyecdysone, polypodine b) and a carbohydrate (2-deoxy-d-ribono-1,4-lactone). These compounds have also been identified in the underground parts of H. cyclophyllus Boiss by other researchers (Tsiftsoglou et al. 2018). Hellebrin and hellebrigenin have the capacity to bind to the potassium-sodium pump ATPase of cancer cells (alpha subunits) and to suppress cancer cell viability (Banuls et al. 2013). Furthermore, Prassas et al. (2011) have proposed that cardiac glycosides have the ability to induce selectively apoptotic cell death on cancer cells compared with normal cells by altering the expression of potassium-sodium pump subunits. Potassium-sodium pump ATPase participates in a variety of biological functions including osmotic regulation of the cell volume and cell adhesion (Mijatovic et al. 2007). The fact that A549 cells, after 24 h treatment, were detached and swollen, could be related to this effect. Clinical observations in patients undergoing treatment with cardiac glucosides as well as in vitro studies have indicated that cardiac glucosides induce apoptosis on resistant to anoikis cancer cells through the inhibition of potassium-sodium pump ATPase and reduce metastasis (Simpson et al. 2009). A recent study indicated that the cardiac glucoside degluco-hellebrin and, at a lower degree, the phytoexdysone 20-hydroxyecdysone, components of the Helleborus caucasicus rhizomes, caused apoptotic cell death on Calu-1 lung cancer cells via the endoplasmic reticulum stress inducing intrinsic pathway of apoptosis (Martrucciello et al. 2018) approximately 24 h of exposure. According to our results, when Α549 cells were treated with high concentrations of the extract (6.00 mg mL−1), besides apoptotic nuclei formation, some nuclei appeared compressed at the periphery of the cell, showing indications of karyolysis, a phenomenon associated with cell necrosis. These findings suggest that at higher concentrations, the extract can also induce necrotic cell death. Similar results were reported for the effect of Helleborus niger on various cancer cell lines (Schink et al. 2015).

The present study demonstrates that the tested extract of H. cyclophyllus Boiss was particularly active on A549 cancer cells. Primary human lung fibroblasts did not undergo apoptosis after treatment with H. cyclophyllus Boiss, contrary to A549 cells. This was confirmed by the morphological evaluation and the lack of procaspase-3 and PARP1 cleavage. In particular, at concentrations lower than 0.10 mg mL−1, the tested extract did not affect significantly these cells, although, at higher concentrations, indications of cell death were observed, but without indications of apoptosis.

Conclusions

To conclude, in vitro experiments provided strong evidence for a potent anticancer activity of H. cyclophyllus Boiss leaves’ extracts on A549 cancer cells leading them to apoptosis at low concentrations. Such concentrations are appropriate for considering a plant as promising source for further evaluation (Butterweck and Nahrstedt 2012). Depending on the concentration and the treatment period, cancer cells formed ectosomes, underwent progressively detachment from their substrate, formed a cytoplasmic vesicle similar to thanatosome, nuclei fragments, apoptotic bodies and showed signs of necrosis. Primary human lung fibroblasts did not undergo apoptosis, showing a much higher resistance to H. cyclophyllus Boiss, than A549 cancer cells, since significantly higher concentrations of H. cyclophyllus Boiss were required for showing evidence of cell death.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of this work by the project “An Open-Access Research Infrastructure of Chemical Biology and Target-Based Screening Technologies for Human and Animal Health, Agriculture and the Environment (OPENSCREEN-GR)” (MIS 5002691) which is implemented under the Action “Reinforcement of the Research and Innovation Infrastructure”, funded by the Operational Programme “Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation” (NSRF 2014–2020) and co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund). The authors would also like to thank the “Unit for characterization and testing of bioactive compounds” and the “Unit of high resolution analysis ORBITRAPLC-MSn” of the University of Ioannina for the access to the facilities. Acknowledgments are due to Dr D. Kletsas, Research Director in the National Center for Scientific Research “Democritos” for his kind remarks and the donation of primary human lung fibroblasts.

Funding

The work was supported by the project “An Open-Access Research Infrastructure of Chemical Biology and Target-Based Screening Technologies for Human and Animal Health, Agriculture and the Environment (OPENSCREEN-GR)” (MIS 5002691) which is implemented under the Action “Reinforcement of the Research and Innovation Infrastructure”, funded by the Operational Programme “Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation” (NSRF 2014–2020) and co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund).

Availability of data and materials

All the data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no competing interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Paraskevi Yfanti, Email: pyfanti@uoi.gr.

Athanassios Karkabounas, Email: akarkab@uoi.gr.

Anna Batistatou, Email: abatista@uoi.gr.

Eleni Leneti, Email: elleneti@uoi.gr.

Marilena E. Lekka, Email: mlekka@uoi.gr

References

- Banuls LMY, Katz A, Miklos W, Cimmino A, Tal DM, Ainbinder E, Zehl M, Urban E, Evidente A, Kopp B, Berger W, Feron O, Karlish R, Kiss R. Hellebrin and its aglycone form hellebrigenin display similar in vitro growth inhibitory effects in cancer cells and binding profiles to the alpha subunits of the Na+/K+-ATPase. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:33. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldingh Debernard KA, Aziz G, Gjesvik AT, Paulsen RE. Cell death induced by novel procaspase-3 activators can be reduced by growth factors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;413:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterweck V, Nahrstedt A. What is the best strategy for preclinical testing of botanicals? A critical perspective. Planta Μed. 2012;78:747–754. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone I, Sinisgalli Ch, Ostuni A, Armentano MF, Carmosino M, Milella L, Russo D, Labanca F, KhanH Astaxanthin anticancer effects are mediated through multiple molecular mechanisms: a systematic review (Review) Pharmacol Res. 2020;155:104689. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey A. Strategies for discovering drugs from previously unexplored natural products. Drug Discov Today. 2000;5:294–300. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(00)01511-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm P, Gullbo J, Claeson P, Goransson U, Johansson S, Backlund A, Larsson R, Bohlin L. Selective cytotoxicity evaluation in anticancer drug screening of fractionated plant. Extracts J Biomol Screen. 2002;7:333–340. doi: 10.1089/108705702320351187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maior MC, Dobrotă C. Natural compounds with important medical potential found in Helleborus sp. Cent Eur J Biol. 2013;8:272–285. doi: 10.2478/s11535-013-0129-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martucciello S, Paolella G, Muzashvili T, Skhirtladze A, Pizzad C, Caputoa I, Piacented S. Steroids from Helleborus caucasicus reduce cancer cell viability inducing apoptosis and GRP78 down-regulation. Chem Biol Interact. 2018;279:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mijatovic T, Van Quaquebeke E, Delest B, Debeir O, Darro F, Kiss R, Mijatovic T, Van E, Quaquebeke B, Delest Debeir O. Cardiotonic steroids on the road to anti-cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1776:32–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Chai HB, Kinghorn AD. Discovery of new anticancer agents from higher plants. Front Biosci. 2012;4:142–156. doi: 10.2741/257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou JC, Drachenberg CB, Brenner DS, Newkirk C, Τrump BF, Silverberg SG. “Thanatosomes”: a unifying morphogenetic. Concept for tumor hyaline globules related to apoptosis. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1455–1465. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2000.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prassas I, Karagiannis GS, Batruch I, Dimitromanolakis A, Datti A, Diamandis EP. Digitoxin-induced cytotoxicity in cancer cells is mediated through distinct kinase and interferon signaling networks. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:2083–2093. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosselli S, Maggio A, Bruno M, Spadaro V, Formisano C, Irace C, Maffettone C, Mascolo N. Furostanol saponins and ecdysones with cytotoxic activity from Helleborus bocconeis sp. intermedius Phytother Res. 2009;23:1243–1249. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadallah S, Eken C, Schifferli JA. Ectosomes as modulators of inflammation and immunity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;163:26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schink M, Garcia-Käufer M, Bertrams J, Duckstein SM, Müller MB, Huber R, Stintzing FC, Gründemann C. Differential cytotoxic properties of Helleborus niger L. on tumour and immunocompetent cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;159:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segneanu AE, Grozescu I, Cziple F, Berki D, Damian D, Niculite CM, Florea A, Leabu M. Helleborus purpurascens-amino acid and peptide analysis linked to the chemical and antiproliferative properties of the extracted compounds. Molecules. 2015;20:22170–22187. doi: 10.3390/molecules201219819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CD, Mawji IA, Anyiwe K, Williams MA, Wang X, Venugopal AL, Gronda M, Hurren R, Cheng S, Serra S, Zavareh RB, Datti A, Wrana JL, Ezzat S, Schimmer AD. Inhibition of the Sodium potassium adenosine triphosphatase pump sensitizes cancer cells to anoikis and prevents distant tumor formation. Cancer Res. 2009 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stochmal A, Perrone A, Piacente S, Oleszek W. Saponins in aerial parts of Helleborus viridis L. Phytochemistry Lett. 2010;3:129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2010.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiftsoglou O, Stefanakis M, Lazari D. Chemical constituents isolated from the rhizomes of Helleborus odorus subsp. cyclophyllus (Ranunculaceae) Biochem Syst Ecol. 2018;78:8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2018.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tutin TG, Burges NA, Chater AO, Edmondson JR, Heywood VH, Moore DM, Valentine DH, Walters SM, Webb DA, editors. Flora Europaea vol 1: Psilotaceae to Platanaceae. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Vokou D, Katradi K, Kokkini S. Ethnobotanical survey of Zagori (Epirus, Greece), a renowned centre of folk medicine in the past. J Ethnopharmacol. 1993;39:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(93)90035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yfanti P, Batistatou A, Manos G, Lekka ME. The aromatic plant Satureja horvatii ssp. macrophylla induces apoptosis and cell death to the A549 cancer cell line. Am J Plant Sci. 2015;6:2092–2103. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2015.613210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.