Abstract

The co-inoculation of Bradyrhizobium with other non-bradyrhizobial strains was already assessed on cowpea, but the co-inoculation of two Bradyrhizobium strains was not tested up to now. This study aimed to evaluate the cowpea growth, N accumulation, and Bradyrhizobium competitiveness of the elite strain B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 when co-inoculated with other efficient Bradyrhizobium from the Brazilian semiarid region. Three potted-plant experiments were carried out. In the first assay, 35 efficient Bradyrhizobium isolates obtained from the semiarid region of Brazil were co-inoculated with the elite strains B. pachyrhizi BR 3262. The experiment was conducted in gnotobiotic conditions. The plant growth, nodulation, N nutritional variables, and nodular occupation were assessed. Under gnotobiotic and non-sterile soil conditions, ten selected bacteria plus the elite strain B. yuanmingense BR 3267 were used at the second and third experiments, respectively. The cowpea was inoculated with the 11 bacteria individually or co-inoculated with BR 3262. The plant growth and N nutritional variables were assessed. A double-layer medium spot method experiment was conducted to evaluate the interaction among the co-inoculated strains in standard and diluted YMA media. The co-inoculation treatments showed the best efficiency when compared to the treatments inoculated solely with BR 3262. This strain occupied a low amount of cowpea nodules ranging from 5 to 67.5%. The treatments with lower BR 3262 nodule occupancy showed the best results for the shoot nitrogen accumulation. The culture experiment showed that four bacteria inhibited the growth of BR 3262. In contrast, seven strains from the soils of Brazilian semiarid region were benefited by the previous inoculation of this strain. In the second and third experiments, the results indicated that all 11 co-inoculated treatments were more efficient than the single inoculation, proofing the best performance of the dual inoculation of Bradyrhizobium on cowpea.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-020-02534-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Biological nitrogen fixation, Dual Bradyrhizobium inoculation, Inoculant, Strain selection, Vigna unguiculata (L.) walp

Introduction

Cowpea [Vigna unguiculata L. (Walp)] is an important crop in the tropics. In Brazil, this species is grown mainly in family-based rainfed agricultural systems, mainly in the North and Northeast regions (Freire Filho 2011). In the last few years, the crop spread to Central Brazil, grown after the soybean in large and high technological farms (Batista et al. 2017; Silva Júnior et al. 2018). In the Brazilian semiarid region, cowpea is grown without fertilizer application during the short rainy season, and the average production is low, below 400 kg ha−1 below than those in the North (around 800 kg ha−1) and Central Brazil (above 1300 kg ha−1) (IBGE 2019). Nevertheless, the development of low-cost and environmentally safe technologies is needed to improve cowpea yield in the Northeast Brazilian region.

The inoculation of cowpea rhizobia is a promising technology to improve cowpea production in the Brazilian northeast region (Marinho et al. 2014). Isolation and selection of native rhizobia have been reported in the field conditions in Brazilian drylands (Martins et al. 2003; Fernandes Júnior et al. 2012; Marinho et al. 2014, 2017; Xavier et al. 2017). More recently, the bioprospection of new cowpea rhizobia from the same region indicated the existence of high efficient Bradyrhizobium and Microvirga strains, showing better performance than those officially recommended strains for inoculant production (Oliveira et al. 2020; Sena et al. 2020).

Four Bradyrhizobium strains are authorized for inoculant production in Brazil (Brasil 2011). Among that highly efficient N2-fixing and competitive strains, two have been extensively studied by our research group in the last few years: B. yuanmingense BR 3267 native from the semiarid region of Pernambuco state (Martins et al. 2003); and B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 isolated from an agroecological production system in Rio de Janeiro state. Both strains are highly efficient in Brazilian drylands (Marinho et al. 2014; Xavier et al. 2017). Besides its efficiency, BR 3262 strain also presents in vitro the ability to produce auxins (Menezes et al. 2016), a remarkable characteristic of plant growth promoter bradyrhizobia (Ferreira et al. 2020b). Although, the interaction of the elite strain B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 with members of the bradyrhizobial community of the soils of Brazilain drylands was not studied.

Inoculation of non-rhizobial plant-growth-promoting bacteria and rhizobia can increase the plant growth and nodulation of several legumes such as cowpea (Rodrigues et al. 2012), soybean (Glycine max) (Hungria et al. 2013, 2015; de Naoe et al. 2020; Moretti et al. 2020; Rondina et al. 2020), peanuts (Arachis hypogaea) (Ibáñez et al. 2009; Vicario et al. 2016), common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) (Figueiredo et al. 2008; Hungria et al. 2013; Ferreira et al. 2020a) among others. Recently, the growth promotion and nitrogen fixation were improved by the co-inoculation of Bradyrhizobium elkanii 29w or B. diazoefficiens USDA 110T and Rhizobium tropici CIAT 899T in common bean (Jesus et al. 2018; de Carvalho et al. 2020). In these studies, the authors co-inoculated an agronomically efficient common bean R. tropici CIAT 899T with its non-preferred symbionts (Bradyrhizobium spp.). These results support that Bradyrhizobium could act as a plant-growth promoter, helping the common bean nodulation by its preferential microsymbiont (CIAT 899T).

Compared to the single inoculation, the co-inoculation of two Bradyrhizobium strains was positively related to the growth, chlorophyll content (Vargas-Díaz et al. 2019), and nitrogen accumulation on soybean (de Carvalho et al. 2005) but not on cowpea (Xavier et al. 2017; Silva Júnior et al. 2018). In cowpea, the strains probably compete with each other and occupy the nodulation sites and are efficient in N fixation, whatever the nodule-occupying bacteria. In this case, it is not expected that the co-inoculation of two efficient and competitive Bradyrhizobium could increase the cowpea nodulation, growth, and N fixation. The plant growth promotion abilities of Bradyrhizobium on legumes (Jesus et al. 2018; Ferreira et al. 2020a) and non-legumes (Machado et al. 2016; Cavalcanti et al. 2020; Ferreira et al. 2020b) indicate that when co-inoculated with two Bradyrhizobium, the lower nodulating bacteria could act as an efficient plant growth promoter.

Therefore, we hypothesized that the co-inoculation of two efficient Bradyrhizobium could promote cowpea growth and nodulation better than a single strain inoculation. This study aimed to evaluate the cowpea growth, N accumulation, and Bradyrhizobium competitiveness of the elite strain B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 when co-inoculated with other efficient Bradyrhizobium from the Brazilian semiarid region.

Materials and methods

Bradyrhizobium strains and cowpea material

Bradyrhizobium spp. from the semiarid region of Brazil were used in this study. The strains were previously isolated, identified, and confirmed to be symbiotically efficient in different cowpea genotypes. The strains ESA 124, ESA 125, ESA 132, ESA 138, ESA 144, ESA 147, ESA 151, ESA 158, ESA 162, ESA 163, ESA 166, ESA 167, ESA 168, ESA 173, ESA 180, and ESA 192 were isolated and selected by Oliveira et al. (2020). The bacteria ESA 366, ESA 369, ESA 371, ESA 372, ESA 373, ESA 376, ESA 378, ESA 379, ESA 380, ESA 381, ESA 382, ESA 383, ESA 384, ESA 385, ESA 386, ESA 387, ESA 388, ESA 389 and ESA 390 were isolated and characterized by Sena et al. (2020). The strains B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 (Zilli et al. 2009) and B. yuanmingense BR 3267 (Martins et al. 2003) are elite strains recommended to the production of cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.] inoculants in Brazil (Brasil 2011). The cowpea cv. BRS Pujante was used in the three plant experiments.

First plant experiment: co-inoculation of 35 Bradyrhizobium spp. and the elite strain B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 under gnotobiotic conditions

In the first experiment, co-inoculation of B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 with 35 strains Bradyrhizobium spp. obtained from the semiarid region of Brazil ("ESA" isolates above-mentioned) were evaluated in a greenhouse under gnotobiotic conditions.

The cowpea seeds were surface disinfected with ethanol 96% (v v−1) for 30 s, sodium hypochlorite 2.5% (v v−1) for five minutes followed by eight washes in distilled and autoclaved water (DAW) (Somasegaran and Hoben 1994). The experiment was implemented in 500 mL polystyrene pots filled with around 600 g of twice-autoclaved sand (120 °C and 1.5 atm for 1 h, with no less than 72 h between the sterilizations). The pots were disinfected by rinsing with sodium hypochlorite 2.5% (v v−1). After disinfection, the pots were washed three times, with DAW, and filled carefully with the sterile sand. Then, three seeds were sowed per pot.

The bradyrhizobia grew in YM medium (Vincent 1970) in the constant stirring of 120 rpm for six days at room temperature (25 ± 3 °C) in an orbital shaker (Tecnal, TE-145, Brazil). After growth, the optical density was adjusted to 0.6 at 600 nm of wavelength (OD600 = 0.6) in a spectrophotometer (Thermo-Scientific, Multiskan GO, USA). After sowing, one milliliter of culture broth was inoculated over each seed. In the co-inoculated treatments, the seeds received 1 mL of B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 and 1 mL of the other bradyrhizobial strain. In the treatments inoculated only with B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 or B. yuanmingense BR 3267, 2 mL of the culture broths were inoculated over each seed. Besides the inoculated treatments, two uninoculated treatments were assessed: the "negative control" treatment, without inoculation or N application, and the "N-fertilization” treatment, with the application of 80 mg of N-NH4NO3 week−1, from the second to the fifth week. In the sowing, the uninoculated treatments received 2 mL of sterile YM medium per seed.

The pots were supplied with 50–100 mL of DAW daily up to the cotyledon fall off, at 10 days after the emergence (DAE). At 10 DAE, the spare plants were cut and removed, leaving one plant per pot. From the 14 DAE to the end of the experiment, the plants received around 50–100 mL of DAW daily, and 100 mL of a nitrogen-free nutrient solution (Norris and Mannetje 1964) was applied once a week. The experiment was conducted between September to October of 2018. The plants were harvested at 45 DAE.

The roots were separated from the shoots and washed carefully with current tap water. The nodules were detached and counted. Roots, shoots, and nodules of each plant were placed separately in paper bags and left to dry in an airflow chamber at 65 °C for 7 days and weighted for determination of shoot dry mass (SDM), root dry mass (RDM) and nodule dry mass (NDM). Shoots were also milled and sieved (2 mm) for determination of the nitrogen concentration in the shoots (NCS) by the dry combustion method in a TruSpec CN elemental analyzer (Leco, USA) following the manufacturer instructions. These values were used to calculation of the nitrogen accumulation in the shoots (NAS) by the multiplication of NCS (mg N g plant−1) to the SDM.

The competition of the BR 3262 strain was evaluated by the PCR amplification using strain-specific primers according to the methodology proposed by Osei et al. (2017) briefly described below. Ten nodules of the crown region of each cowpea root (each pot) were randomly selected in all inoculated treatment, totalizing 1480 nodules. The DNA of the nodules was extracted individually for all nodules. The extraction was conducted by manual maceration of each nodule in sterile 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes using sterilized plastic pestles. The DNA was stored at − 20 °C until the performance of PCRs.

The PCRs were adjusted to 15 µL with 1X buffer, MgCl2 1.5 mM, dNTP 0.75 mM, 0.10 µM of the primers 2645-F (TAGAGGGCTGCTATCATGTC) and 2645-R (GAGATGATTACCGCAATGAG), 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 2 µL of nodule DNA as the template. To the PCR, an initial denaturation step of 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (30 s, 95 °C), annealing (30 s, 60 °C), and extension (30 s, 72 °C) followed by a final cycle of extension of five minutes at 72 °C. The reactions were performed in a Veriti 96 well thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, USA). The PCR products were subjected to horizontal electrophoresis in 1% (w v−1) agarose gel at 100 V for 60 min.

Each nodule was considered occupied by the BR 3262 strain by a clear amplicon around 200 bp, characteristic of the strain-specific amplification. In all reactions, one sample with the DNA of BR 3262 strain and other with DNA extracted by a nodule induced by BR 3262 in gnotobiotic conditions were as positive controls. The negative controls were the DNA of BR 3267 strain and other with DNA extracted by a BR 3267 nodule, in addition to the non-template control. As a quality control, in all rounds of DNA extraction, two nodules of cowpea inoculated with BR 3262 or BR 3267 (gnotobiotic conditions) were used, as positive and negative controls, respectively, to assure the correct extraction procedure.

Second and third plant experiments: co-inoculation of 11 Bradyrhizobium spp. and the elite strain B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 under gnotobiotic conditions and in non-sterile soil

In the second and third experiments, the strains ESA 124, ESA 162, ESA 168, ESA 173, ESA 192, ESA 369, ESA 376, ESA 380, ESA 386, ESA 387, and BR 3267 were selected to be assessed in single inoculation and under co-inoculation with the elite strain BR 3262. These strains were selected because they had the best performance when co-inoculated with BR 3262 in first experiment. For both experiments, the bacteria grew in the YM medium and were OD600 = 0.6 adjusted, as described above. Besides, co-inoculated treatments received 1 mL of OD600 broth for each bacteria per seed. The treatments inoculated with one strain received 2 mL of the broth. For both assays, the cowpea seeds were surface disinfected, as described in the first experiment. The second experiment was conducted in a greenhouse under gnotobiotic conditions, as described for the first assay. The pots, substrate, and inoculation procedures were the same above-described. The experiment was conducted between January to February of 2019. The plants were harvested at 45 DAE.

The third experiment was conducted in forest-nursery using non-sterile soil as a substrate. The soil was collected in 0–0.2 m of a Ultisol in the Bebedouro Experimental Field (09º08’13” S; 40°18°24” W), in the dependencies of Embrapa Semiárido, in Petrolina, Pernambuco state. The chemical composition of the soil was assessed, according to Teixeira et al. (2017) (Table S1). 3-L polypropylene pots were filled with the soil (around 3.5 kg pot−1), and the cowpea seeds were sowed after that. The plants were irrigated daily with 200–300 mL for each day of distilled water. This experiment was conducted between March and May of 2019, and the plants were harvested at 52 DAE. The N-fertilization treatment plants in this experiment received 100 mg of N-NH4NO3 week−1, from the second to the fifth week.

The variables assessed in the second and third experiments were the shoot (SDM), root (RDM) and nodule number per plants (NN), nodule dry mass (NDM), the nitrogen concentration in the shoots (NCS) nitrogen accumulation in the shoots (NAS) according to above-mentioned.

Assessment of the Bradyrhizobium spp. growth pattern in a double-layer medium experiment

The synergy/antagonism between the 10 Bradyrhizobium spp. from the semiarid region of Brazil and the strain B. yuanmingense BR 3267 were assessed against the elite strain B. pachyrhizi BR 3262. We used the spot test method for this assay, according to Schwinghamer (1971), with modifications, briefly described below.

All bacteria grew in the YM medium for 5 days. Then, 1 mL of each bacterial broths were centrifuged at 6000 g for five minutes. The supernatants were discarded, and the pellets were resuspended in DAW. This procedure was repeated twice. Three aliquots with 10 µL were dropped in three equidistant points of YMA dishes. We used both original YMA and 1/5 strength YMA medium (reducing all nutrients and carbon source by 1/5). Therefore, this medium will be called oligotrophic YMA (oYMA). The use of the oYMA medium was applied to evaluate the bacterial behavior under standard culture conditions (YMA medium) and oligotrophic conditions, close to the bacterial conditions when just inoculated in the sowed seeds.

The YMA and oYMA dishes inoculated solely with all bacterial broths (10 Bradyrhizobium spp., BR 3267, and BR 3262) were incubated at room temperature for 6 days. For the second layer, we produced YMA and oYMA media using a low melt point agar. All bacteria grew in YM medium, and the OD600 = 0.6 adjusted as described before, and the broths were mixed in the low-temperature YMA and oYMA media. After the mixture (OD600 adjusted broth + medium), the second layers were overlayed in the Petri dishes.

The inoculation strategy consisted of: (1) YMA medium at both layers—BR 3262 inoculated in the spots at the bottom layer overlayed separately with the 12 strains (BR 3262, BR 3267, and the ten strains isolated from the semiarid region of Brazil); (2) oYMA medium at both layers—BR 3262 inoculated in the spots at the bottom layer overlayed separately with the 12 strains; (3) YMA medium at both layers—the 12 strains inoculated in the spots at the bottom layer overlayed with BR 3262; and (4) oYMA medium at both layers—the 12 strains inoculated in the spots at the bottom layer overlayed with BR 3262.

The dishes were incubated for 6 days after the inoculation of the second layer. The evaluation, we observed the growth pattern of the bacteria in the second layer: Inhibition of the bacterial growth by the bacteria in the bottom layer (translucent zone surrounding the colonies of the bottom layer); No interference in the bacterial growth; Stimulation of the bacterial growth (intense growth in the edges or on the colonies of the bacteria in the bottom layer).

The experiment was conducted in three replications in a completely randomized design. The results were assessed in the three replications. The experiment was repeated twice, and the data compared. No discrepancies were observed in both assays.

Statistical analysis

The potted-plant experiments were set up in a completely randomized design with for replications per treatment. The normal distribution of data from greenhouse experiments was verified through of Shapiro–Wilk test. Data were evaluated through one-way ANOVA using the transformation (x + 1)0.5 to NN, NDM, and TNC. The data of BR 3262 nodule occupancy in the first experiment, the transformation arcsin (x/100)0.5, was used. Following the ANOVA, the Scott–Knott average range test (p < 0.05) was applied.

The statistical analysis was carried out using the Sisvar software v. 5.0 (Ferreira 2011). The principal component analysis (PCA) carried with the second and third experiment compiled data was conducted with the correlation matrix in the PaSt v. 4.02 software (Hammer et al. 2011). NN and NDM variables were not used in PCA to avoid bias due to the absence of nodules (gnotobiotic assay) and low nodulation (non-sterile soil assay) as intrinsic characteristics of the non-inoculated treatments. Before PCA, the data were normalized by subtracting the average of the treatment on each experiment.

Results

Co-inoculation of B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 and 35 Bradyrhizobium spp. in gnotobiotic conditions

The non-inoculated treatments did not nodulate, while all the plants of the 37 inoculated treatments nodulated equally (Table 1). The co-inoculation of BR 3262 and 28 Bradyrhizobium spp. improved the dry mass of cowpea shoots (15–64%) compared to the single elite strains BR 3262 and BR 3267. For the dry mass of roots, 30 co-inoculation treatments and the single inoculation of BR 3262 and BR 3267 were clustered in the highest statistical cluster, based on the Scott-Knott mean range test, highest than the N-fertilized and non-inoculated treatments.

Table 1.

Shoot (SDM), root (RDM), and nodule (NDM) dry mass, number of nodules per plant (NN), nitrogen content in the shoots (NCS), nitrogen accumulated in the shoots (NAS), and nodule occupancy of Bradyrhizobium pachyrhizi BR 3262 of cowpea cv. BRS Pujante inoculated or co-inoculated with symbiotically efficient Bradyrhizobium at 45 days after the emergency

| Inoculation treatment | SDM | RDM | NN | NDM | NCS | NAS | BR 3262 nodule occupancy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g plant−1 | nod plant−1 | mg plant−1 | mg N g plant−1 | mg N plant−1 | |||

| ESA 124 + BR 3262 | 1.61a | 1.86a | 154a | 122a | 68b | 110b | 35.0d |

| ESA 125 + BR 3262 | 1.87a | 2.76a | 131a | 126a | 59c | 109b | 17.5d |

| ESA 132 + BR 3262 | 1.71a | 2.04a | 113a | 115a | 53c | 91c | 50.0c |

| ESA 138 + BR 3262 | 1.62a | 3.74a | 129a | 123a | 46d | 76c | 15.0d |

| ESA 144 + BR 3262 | 1.33a | 2.39a | 133a | 118a | 52c | 70c | 55.0c |

| ESA 147 + BR 3262 | 1.17b | 1.07b | 107a | 108a | 51d | 60d | 67.5b |

| ESA 151 + BR 3262 | 1.85a | 2.31a | 155a | 123a | 76a | 143a | 40.0c |

| ESA 158 + BR 3262 | 1.55a | 2.25a | 201a | 144a | 82a | 128b | 20.0d |

| ESA 162 + BR 3262 | 1.49a | 1.38a | 100a | 103a | 49d | 73c | 7.5e |

| ESA 163 + BR 3262 | 1.71a | 1.22a | 107a | 101a | 49d | 83c | 12.5e |

| ESA 166 + BR 3262 | 1.11b | 2.01a | 138a | 113a | 48d | 51d | 50.0c |

| ESA 167 + BR 3262 | 1.86a | 2.19a | 153a | 131a | 78a | 146a | 5.0e |

| ESA 168 + BR 3262 | 1.52a | 1.90a | 152a | 125a | 74a | 112b | 50.0c |

| ESA 173 + BR 3262 | 1.91a | 2.76a | 110a | 120a | 64b | 124b | 32.5d |

| ESA 180 + BR 3262 | 1.82a | 1.63a | 141a | 127a | 55c | 100b | 55.0c |

| ESA 192 + BR 3262 | 1.67a | 1.61a | 143a | 124a | 49d | 83c | 35.5d |

| ESA 366 + BR 3262 | 1.54a | 1.09b | 147a | 132a | 60c | 91c | 42.5c |

| ESA 369 + BR 3262 | 1.69a | 1.43a | 161a | 140a | 53c | 89c | 42.5c |

| ESA 371 + BR 3262 | 1.49a | 1.32a | 117a | 102a | 69b | 105b | 32.5d |

| ESA 372 + BR 3262 | 1.07b | 1.85a | 109a | 116a | 49d | 51d | 22.5d |

| ESA 373 + BR 3262 | 1.70a | 1.71a | 125a | 113a | 48d | 82c | 67.5b |

| ESA 376 + BR 3262 | 1.77a | 1.61a | 118a | 113a | 58c | 102b | 17.5d |

| ESA 378 + BR 3262 | 1.92a | 1.87a | 144a | 130a | 55c | 105b | 25.0d |

| ESA 379 + BR 3262 | 1.20b | 1.62a | 106a | 88a | 50d | 62d | 25.0d |

| ESA 380 + BR 3262 | 2.02a | 1.78a | 135a | 112a | 82a | 166a | 17.5d |

| ESA 381 + BR 3262 | 1.92a | 2.48a | 137a | 129a | 64b | 126b | 15.0d |

| ESA 382 + BR 3262 | 1.55a | 1.28a | 128a | 129a | 57c | 87c | 7.5e |

| ESA 383 + BR 3262 | 1.20b | 1.16b | 96a | 94a | 45d | 54d | 27.5d |

| ESA 384 + BR 3262 | 1.76a | 1.39a | 110a | 119a | 54c | 96c | 57.5c |

| ESA 385 + BR 3262 | 1.97a | 1.56a | 101a | 97a | 43d | 86c | 55.0c |

| ESA 386 + BR 3262 | 1.26b | 1.17b | 132a | 100a | 47d | 59d | 27.5d |

| ESA 387 + BR 3262 | 1.84a | 1.53a | 144a | 129a | 49d | 92c | 25.0d |

| ESA 388 + BR 3262 | 1.47a | 1.24a | 118a | 121a | 52d | 76c | 22.5d |

| ESA 389 + BR 3262 | 1.82a | 2.34a | 108a | 124a | 46d | 84c | 10.0e |

| ESA 390 + BR 3262 | 1.31b | 1.02b | 99a | 100a | 58c | 76c | 15.0d |

| BR 3262 | 1.23b | 2.02a | 118a | 134a | 74a | 93c | 100.0a |

| BR 3267 | 1.28b | 2.01a | 113a | 123a | 70b | 90c | 0e |

| N-fertilization* | 2.30a | 1.19b | 0b | 0b | 88a | 202a | – |

| Negative control | 0.73c | 0.23c | 0b | 0b | 31e | 23e | – |

| CV (%) | 18.2 | 16.9 | 12.5 | 10.1 | 14.9 | 13.1 | 11.5 |

Experiment under gnotobiotic conditions. Data are an average of four replications

Means followed by the same letter, in the same variable, do not differ by the Scott–Knott mean range test (p < 0.05). CV coefficient of variation

*80 mg of N-NH4NO3 week−1, from the second to the fifth week

The co-inoculation of BR 3262 with the strains ESA 151, ESA 158, ESA 167, ESA 168, and ESA 380 (74–82 mg N g plant−1), in addition to the single inoculation of the elite strains BR 3262 (74 mg N g plant−1) and BR 3267 (70 mg N g plant−1) resulted in the same nitrogen concentration in the shoots then the N-fertilization treatment. The co-inoculation treatments of BR 3262 with the strains ESA 151, ESA 167, or ESA 380 showed the same averages for the variable N accumulation (143–166 mg N plant−1) in the shoots when compared to the N fertilization (202 mg N plant−1). To the same variable, in 13 co-inoculation treatments, the averages ranged from 100–166 mg N plant−1, being superior to the single inoculation treatment with BR 3262 that reached 93 mg N plant−1.

The co-inoculation of the native strains from the Brazilian semiarid region reduced the nodule occupancy of B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 in the co-inoculated treatments. The co-inoculation of the isolates ESA 162, ESA 163, ESA 167, ESA 382, and ESA 389 resulted in the lower occupation of the BR 3262 (5.0–12.5%). The co-inoculation of the isolates ESA 147 and ESA 373 allowed the highest nodule occupancy of the strain BR 3262, with an average value of 67.5% for both treatments.

Individual inoculation of 11 Bradyrhizobium isolates and their co-inoculation with BR 3262 under gnotobiotic and non-sterile conditions

The single inoculation of the elite strains BR 3262, BR 3267, and 10 selected cowpea Bradyrhizobium from the Brazilian semiarid region induced high nodulation in all experimental replications (Table 2). The single inoculation of the bacteria ESA 124, ESA 162, ESA 168, ESA 173, BR 3262, and BR 3267 resulted in the same dry mass of shoot of the cowpea plants with mineral N. The same result was observed in all 11 co-inoculated treatments. The single inoculation of 10 Bradyrhizobium and 10 co-inoculated treatments improved the root dry mass of the cowpea plants when compared to both non-inoculated controls (improvements until 104%).

Table 2.

Shoot (SDM), root (RDM) and nodule (NDM) dry mass, number of nodules per plant (NN) nitrogen content in the shoots (NCS), nitrogen accumulated in the shoots (NAS) of cowpea cv. BRS Pujante inoculated individually with 12 Bradyrhizobium spp. or co-inoculated (dual inoculation) with B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 and 11 Bradyrhizobium spp. of two experiments under the gnotobiotic condition (45 days after the emergence) and in non-sterile soil (52 days after the emergence) as substrates

| Inoculation treatment | SDM | RDM | NN | NDM | NCS | NAS | SDM | RDM | NN | NDM | NCS | NAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g plant−1 | nod plant−1 | mg plant−1 | mg N g−1 | mg N plant−1 | g plant−1 | nod plant−1 | mg plant−1 | mg N g−1 | mg N plant−1 | |||

| Gnotobiotic experiment (sterile sandas substrate) | Non-sterileconditions experiment (soilas substrate) | |||||||||||

| ESA 124 | 2.06a | 1.66a | 212b | 307a | 45c | 94c | 2.00a | 1.06b | 134c | 197c | 40b | 82b |

| ESA 162 | 2.30a | 1.29a | 189b | 289a | 52c | 119b | 1.25a | 0.89b | 142c | 219c | 55b | 64b |

| ESA 168 | 2.04a | 1.22a | 164b | 208a | 49c | 106b | 1.98a | 1.12b | 200c | 277b | 71a | 150a |

| ESA 173 | 1.94a | 1.30a | 118b | 173a | 41c | 79c | 1.47a | 0.62b | 46d | 96d | 35b | 50b |

| ESA 192 | 1.43b | 1.22a | 164b | 222a | 48c | 69c | 1.55a | 0.93b | 195c | 259b | 78a | 121b |

| ESA 369 | 1.12b | 1.14b | 205b | 167a | 45c | 51c | 1.32a | 0.93b | 149c | 221c | 61b | 82b |

| ESA 376 | 1.19b | 1.34a | 197b | 302a | 48c | 57c | 2.26a | 1.26a | 255b | 381a | 70a | 165a |

| ESA 380 | 1.12b | 1.21a | 137b | 132a | 49c | 55c | 1.79a | 0.99b | 235b | 378a | 46b | 89b |

| ESA 386 | 1.13b | 1.13b | 109b | 166a | 47c | 53d | 1.61a | 0.81b | 189c | 286b | 47b | 77b |

| ESA 387 | 1.51b | 1.23a | 173b | 244a | 52c | 78c | 1.43a | 0.57b | 162c | 298b | 57b | 83b |

| BR 3267 | 1.94a | 1.38a | 166b | 172a | 62b | 118b | 1.59a | 1.51a | 165c | 162c | 42b | 67b |

| BR 3262 | 1.80a | 1.50a | 169b | 206a | 61b | 111b | 1.99a | 1.58a | 146c | 205c | 54b | 113b |

| ESA 124 + bR 3262 | 2.42a | 1.72a | 170b | 202a | 63b | 153a | 1.90a | 1.52a | 315b | 296b | 76a | 145a |

| ESA 162 + bR 3262 | 2.39a | 1.85a | 195b | 190a | 64b | 154a | 1.81a | 1.54a | 308b | 513a | 74a | 132a |

| ESA 168 + bR 3262 | 2.13a | 1.90a | 191b | 176a | 65b | 133b | 1.21a | 1.51a | 268b | 234c | 90a | 109b |

| ESA 173 + bR 3262 | 2.23a | 1.33a | 170b | 172a | 63b | 141b | 2.02a | 1.42a | 271b | 270b | 73a | 149a |

| ESA 192 + bR 3262 | 2.48a | 1.40a | 172b | 191a | 67a | 165a | 1.99a | 1.46a | 284b | 318b | 77a | 155a |

| ESA 369 + bR 3262 | 2.28a | 2.22a | 306a | 333a | 61b | 139b | 2.69a | 1.26a | 275b | 285b | 68a | 194a |

| ESA 376 + bR 3262 | 2.26a | 1.10b | 156b | 200a | 56c | 127b | 2.18a | 1.38a | 291b | 307b | 81a | 176a |

| ESA 380 + bR 3262 | 2.47a | 1.26a | 192b | 211a | 61b | 152a | 2.04a | 1.20a | 373a | 417a | 86a | 177a |

| ESA 386 + bR 3262 | 2.18a | 1.70a | 192b | 219a | 54c | 121b | 2.08a | 1.18a | 417a | 406a | 95a | 194a |

| ESA 387 + bR 3262 | 2.43a | 1.36a | 156b | 186a | 72a | 172a | 2.68a | 1.29a | 322b | 290b | 90a | 247a |

| BR 3267 + bR 3262 | 2.43a | 2.19a | 266b | 338a | 76a | 185a | 2.44a | 1.17a | 149c | 252b | 60b | 145a |

| N-fertilization* | 2.62a | 1.30b | 0c | 0b | 64b | 166a | 2.08a | 0.83b | 6d | 3d | 85a | 179a |

| Negativecontrol | 0.54c | 1.09c | 0c | 0b | 30d | 34 e | 1.44a | 0.98b | 34d | 60d | 28c | 40c |

| CV (%) | 13.7 | 16.5 | 18.2 | 13.4 | 12.2 | 14.7 | 13.9 | 12.9 | 16.4 | 10.4 | 13.4 | 18.2 |

Data are an average of four replications

Means followed by the same letter, in the same variable and in the same experiment, do not differ by the Scott–Knott mean range test (p < 0.05). CV coefficient of variation

*80 mg of N-NH4NO3 week−1, from the second to the fifth week; ** 100 mg of N-NH4NO3 week−1, from the second to the fifth week

The co-inoculation treatments ESA 192 + BR 3262, ESA 387 + BR 3262, and BR 3267 + BR 3262 resulted in the same N in the shoots observed in the N fertilized treatment under gnotobiotic conditions. Furthermore, all inoculated and co-inoculated treatments resulted in a higher nitrogen concentration in cowpea shoots than the negative control. The plants of the treatments ESA 124 + BR 3262, ESA 162 + BR 3262, ESA 192 + BR 3262, ESA 380 + BR 3262, ESA 387 + BR 3262, and BR 3267 + BR 3262 accumulated high amounts of N in their shoots, with the averages ranging from 153 to 185 mg N plant−1, and were comparable to the mineral N treatments (166 mg N plant−1). All treatments were higher than the negative control treatment.

Twenty-two out of 23 inoculation treatments improved the cowpea nodulation in non-sterile soil, compared to the non-inoculated treatments. No differences were observed in the dry mass of shoots. The dry mass of roots on all co-inoculated treatments (1.18–1.54 g plant−1) and the single inoculation of ESA 376 (1.26 g plant−1), BR 3267 (1.51 g plant−1), and BR 3262 (1.58 g plant−1) was higher than the other treatments. The N content in cowpea shoots inoculated with ESA 168, ESA 192, and ESA 376, plus all the co-inoculated treatments, were the same observed in N fertilized plants and higher than found in the negative control. In except to co-inoculation treatment ESA 168 + BR 3262, all co-inoculated treatments and the single inoculation of ESA 168 or ESA 376, the nitrogen accumulation in the shoots was the same as that in plants supplied with mineral N, been higher than that in the negative control treatment.

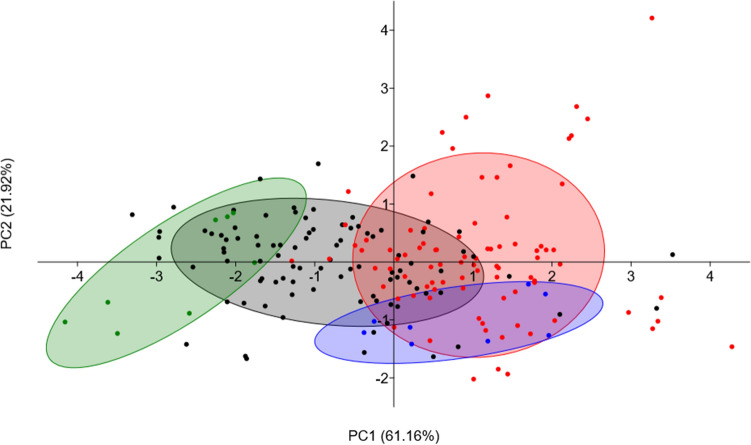

In the principal component analysis, the PC1 and PC2 explained 83.08% of the variance (Fig. 1). The biplot clustered the co-inoculated treatments partially correlated to the treatments with a single inoculation. The N-fertilization treatment with mineral N was related to the co-inoculation. The negative control treatment was positioned apart from co-inoculation and N-fertilization treatments and partially related to the single inoculation cluster.

Fig. 1.

Biplot of the principal component analysis (PCA) conducted with the data (all replications) of the experiments with the inoculation of 10 Bradyrhizobium spp. and the elite strains B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 and B. yuanmingense BR 3267, and co-inoculation of these 11 strains with and B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 under gnotobiotic (experiment 2) and non-sterile soil (experiment 3) conditions. Red dots: co-inoculated treatments (n = 88); Black dots: inoculated treatments (n = 96); Blue dots: N fertilized control treatment (n = 8); Green dots: non-inoculated and non-N fertilized treatment (n = 8). PC1 and PC2 are the principal components one and two, respectively

Bradyrhizobium spp. growth pattern in the double layer medium assay

The inoculation of the Bradyrhizobium spp. in the top layer of the medium (overlayed) with the elite strain B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 previously inoculated in the spots of the bottom layer did not show any negative influence of BR 3262 on the 11 Bradyrhizobium spp. both in standard and in the oligotrophic YMA media (Table 3). In contrast, in the YMA medium, the strains ESA 124, ESA 162, ESA 168, ESA 173, ESA 192, ESA 376, and ESA 386 grew better surrounding the colonies of BR 3262 in the bottom layer. In the oYMA medium, the strains ESA 173, ESA 192, ESA 386, and BR 3267 also grew better under the influence of BR 3262 in the bottom layer. The other strains were not influenced by the strain BR 3262 in the conditions assessed.

Table 3.

Growth pattern of Bradyrhizobium spp. in the double layer spot test with two strains

| Strain | BR 3262 in the bottom layer* | BR 3262 overlayed** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YMA | oYMA | YMA | oYMA | |

| ESA 124 | + | + | ± | − |

| ESA 162 | + | ± | ± | ± |

| ESA 168 | + | ± | ± | − |

| ESA 173 | + | + | ± | − |

| ESA 192 | + | + | ± | − |

| ESA 367 | ± | ± | ± | ± |

| ESA 376 | + | ± | ± | ± |

| ESA 380 | ± | ± | ± | ± |

| ESA 386 | + | + | + | ± |

| ESA 387 | ± | ± | ± | ± |

| BR 3267 | ± | + | ± | ± |

| BR 3262 | ± | ± | ||

+ Synergism (positive growth of the second layer near the first layer colonies); ± no influence of the strain in the bottom layer on the overlayed strain; − Antagonism (bacteria in the bottom layer inhibiting the growth of the overlayed strain). YMA = standard YMA medium; oYMA = 1/5 strength YMA medium

*BR 3262 in the spots of the bottom layer and the bacteria in the first collum overlayed (in this case, testing the antagonism/synergism of BR 3262 on the other strains);

**The strains in the first collum in the spots of the bottom layer and BR 3262 overlayed (in this case, testing the antagonism/synergism of the strains on BR 3262)

Assessing the influence of the 11 strains in the growth pattern of BR 3262, antagonisms were caused by the strains ESA 124, ESA 162, ESA 168, ESA 173, and ESA 192 in the oYMA medium. In the traditional YMA medium, only the strain ESA 386 positively influenced the growth of BR 3262. The other ten strains did not influence the growth of the slite strain.

Discussion

The first experiment allowed us to assess the cowpea growth, nodulation, and N nutrition under the influence of two efficient rhizobial isolates, screening several combinations of efficient Bradyrhizobium isolates selected previously under interaction with BR 3262 and cowpea BRS Pujante. This screening showed that the co-inoculation of two Bradyrhizobium improved the plant biomass and N accumulation as well as the single inoculation of elite strains of Bradyrhizobium BR 3262 and BR 3267, in agreement to previous reports on soybean (de Carvalho et al. 2005; Vargas-Díaz et al. 2019), but not on cowpea.

Research results showed that the co-inoculation of efficient strains of Bradyrhizobium spp. and Microvirga vignae did not result in the best plant growth and grain yield than the single inoculation of those strains in the Brazilian Semiarid region (Xavier et al. 2017). Bradyrhizobium + Bradyrhizobium co-inoculation did not improve the cowpea growth and development under organic farming systems in Minnesota, USA (Abou-Shanab et al. 2017). Our results agree with the previous soybean results reported by de Carvalho et al. (2005) in southern Brazil and Vargas-Díaz et al. (2019) in Mexico, being the first systematic report of co-inoculation benefits for cowpea with two Bradyrhizobium strains under potted-plant conditions.

The co-inoculation treatments with higher nodule occupancy of BR 3262 (67.5% when co-inoculated with ESA 147 and ESA 373) did not result in higher N accumulation in the shoots of cowpea when compared to the other treatments. On the other hand, in the treatments with higher N accumulation in the shoots, the BR 3262 strain nodule occupancy was lower than 40%, showing the highly competitive ability and efficiency of the isolates tested against the elite strain. Native strains of soils in semiarid regions are highly competitive to the nodule infection sites, even when competing against proven high efficient strains (Xavier et al. 1998; Martins et al. 2003; Mathu et al. 2012; Marinho et al. 2014).

Among the 35 bacteria assessed in this study, 34 belong to the B. japonicum genomic superclade (Oliveira et al. 2020; Sena et al. 2020), contrasting to the taxonomic position of B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 in the B. elkanii superclade. The biodiversity studies of cowpea in Brazil (Silva et al. 2012; Guimarães et al. 2015; Oliveira et al. 2020; Sena et al. 2020), Venezuela (Ramirez et al. 2020), and the African continent (Mohammed et al. 2018; Jaiswal and Dakora 2019) indicated the preference of cowpea to nodulate with the B. japonicum-like bradyrhizobia in the tropics, what probably influenced in the nodule occupancy of BR 3262.

However, BR 3262 is a strain authorized for commercial inoculants to cowpea; for this reason, this is highly efficient and competitive, highlighting to the other native B. elkanii-like bacteria. Despite being highly competitive, the nodulation of BR 3262, should be changed by the edaphoclimatic conditions that naturally occur in the Brazilian semiarid region. For example, the nodulation of Nepalese B. elkanii-like bacteria is altered by the soybean incubation and growth temperature (Suzuki et al. 2014). However, there are no data about the influence of the edaphoclimatic conditions in the Brazilian Semiarid region on the dynamics of bradyrhizobial populations in soils, opening a new research question in this area. Nevertheless, the other two experiments data reinforce that our strains are competitive and more efficient under co-inoculation conditions on cowpea.

The compatibility of the strains in the double layer spot tests showed important findings of the co-inoculated strains interaction. Under oligotrophic conditions, somewhat those found in the seed surface just sowed in the soils, four out of 11 strains inhibited the BR 3262 growth. Some of these strains induced very low nodule occupation in the first assay. The reduction of the population of BR 3262 in the cowpea seeds should probably be partially responsible for the low nodule occupancy of the elite strains, as observed in the first experiment, and the performance of these strains observed in the other two experiments. The inhibition patterns of rhizobia observed in the double layer assays should be observed due to the production of antibiotics or bacteriocins by the strain in the bottom layer of the medium (Schwinghamer 1971; Goel et al. 1999). Further studies are needed to assure the nature of the antagonism observed in the present study.

In addition to antagonism against BR 3262, seven out of ten strains from the Brazilian semiarid region were benefited from the previous culture of BR 3262 in oligotrophic YMA medium. Together with the antagonism observations, these results indicate that, after the inoculation of two strains, even in the same concentration on cowpea seeds, both population dynamics decrease the proportional cell number of BR 3262. Nodulation of an inoculated strain in cowpea depends on the rate of active cells in the seeds and root primordia (da Silva et al. 2012). In this case, the nodulation of BR 3262, when co-inoculated with the other strains in the present study, is not favored. In addition to reducing the proportion of B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 active cells (by antagonism and increasing the cell density of the co-inoculated strain), this strain does not belong to the taxonomic superclade usually associated with cowpea in tropical conditions, as discussed before.

These findings support the hypothesis that, under co-inoculation conditions with the present study strains, this elite strain should act as a plant growth promoter, rather than the primary N2-fixing strain in symbiosis with cowpea. Several Bradyrhizobium can promote the root growth by other mechanisms, even in non-nodulating species (Machado et al. 2016; Cavalcanti et al. 2020; Ferreira et al. 2020b). Bradyrhizobium also could act as an active common-bean growth promoter when co-inoculated with R. tropici CIAT 899T (Jesus et al. 2018). BR 3262 as a high auxin producer in vitro (Menezes et al. 2016), a characteristic of plant-growth-promoting bradyrhizobial. The findings reported in the present study give the first evidence of a B. elkanii-like bacteria acting as a plant-growth promoter on cowpea.

The second and third experiments reinforced the co-inoculation advantage compared to the single inoculation since the co-inoculation treatments induced the best plants. These observations were highlighted by the PCA given in Fig. 1 since the co-inoculation treatments were apart from the negative control treatments and closer to the N application than the single inoculation treatments. Multivariate analytical techniques are poorly exploited to experiments of inoculation of rhizobia and plant-growth-promoting experiments. These tools should help indicate inoculation and co-inoculation strategies for further studies (Vicario et al. 2016).

The production of commercial inoculants with two or more strains is required for soybean in Brazil (Brasil 2011), different from cowpea. The soybean recommendation is not to increase the inoculant performance, but to increase the probability of success of, at least, one strain in the different edaphoclimatic conditions in Brazil. According to the data observed in the present study, the recommendation to use two isolates in cowpea inoculant should be an approach to improve the field efficiency of the rhizobial inoculant. Therefore, field assays in different edaphoclimatic conditions are needed to assure the co-inoculation efficiency of cowpea.

Conclusions

Bradyrhizobium spp. isolated from soils of the Brazilian semiarid region, and the inoculant strain B. pachyrhizi BR 3262 interact and improve the growth and N nutrition of cowpea both in gnotobiotic and in non-sterile soil conditions, better than the inoculation of a single strain. The improved efficiency of the co-inoculation approach should be a promising strategy for developing more efficient cowpea inoculants.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), INCT-Plant Growth Promoting Microorganisms for Agricultural Sustainability and Environmental Responsibility (CNPq/Fundação Araucária STI/CAPES INCT-MPCPAgro 465133/2014-4) and the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa 23.16.05.016.00.00) as financial support. The thanks are also given to the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) awarded scholarships to the first three authors (Code 001). The Pernambuco State Science Foundation (FACEPE) for awarded scholarships to the fourth and fifth authors (IBPG 0603-5.01/18 and PBPG 0941-5.01/15, respectively). The sixth and last authors are research productivity fellows of CNPq (306812/2018-5 and 311218/2017-2, respectively). Thanks to Ms. Viviane Siqueira Lima Silva to the technical support in the experimental work.

Author contributions

LMVM, ADSF, and PIF-J conceived the research project. TRN, PTSS, GSO, MAMD, and TRS conducted the experimental work. TRN, ADSF, LMVM, and PIF-J analyzed the data. PIF-J wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This paper does not contain any studies with human participants or animals.

References

- Abou-Shanab RAI, Wongphatcharachai M, Sheaffer CC, et al. Competition between introduced Bradyrhizobium japonicum strains and indigenous bradyrhizobia in Minnesota organic farming systems. Symbiosis. 2017;73:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s13199-017-0505-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batista ÉR, Guimarães SL, Bonfim-Silva EM, Polizel de Souza AC. Combined inoculation of rhizobia on the cowpea development in the soil of Cerrado. Rev Cienc Agron. 2017;48:745–755. doi: 10.5935/1806-6690.20170087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brasil (2011) Instrução Normativa no 13/2011 - Normas sobre especificações, garantias, registro, embalagem e rotulagem dos inoculantes destinados à agricultura, das especificações, garantias mínimas e tolerâncias dos produtos

- Cavalcanti MIP, de Nascimento C, Rodrigues DR, et al. Maize growth and yield promoting endophytes isolated into a legume root nodule by a cross-over approach. Rhizosphere. 2020;15:100211. doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2020.100211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva MF, Santos CE, de Sousa CA, et al. Nodulação e eficiência da fixação do N2 em feijão-caupi por efeito da taxa do inóculo. Rev Bras Ciência do Solo. 2012;36:1418–1425. doi: 10.1590/s0100-06832012000500005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho FG, Selbach PA, Bizarro MJ. Eficiência e competitividade de variantes espontâneos isolados de estirpes de Bradyrhizobium spp. recomendadas para a cultura da soja (Glycine max) Rev Bras Ciência do Solo. 2005;29:883–891. doi: 10.1590/s0100-06832005000600006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho RH, da Conceição JE, Favero VO, et al. The co-inoculation of Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium increases the early nodulation and development of common beans. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s42729-020-00171-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Naoe AML, Peluzio JM, Campos LJM, et al. Co-inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense in soybean cultivars subjected to water deficit. Rev Bras Eng Agric e Ambient. 2020;24:89–94. doi: 10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v24n2p89-94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes Júnior PI, da Silva Júnior EB, da Silva JS, et al. Performance of polymer compositions as carrier to cowpea rhizobial inoculant formulations: survival of rhizobia in pre-inoculated seeds and field efficiency. Afr J Biotechnol. 2012;11:2945–2951. doi: 10.5897/AJB11.1885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira DF. Sisvar: a computer statistical analysis system. Cienc e Agrotecnologia. 2011;35:1039–1042. doi: 10.1590/S1413-70542011000600001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira LVM, de Carvalho F, Andrade JFC, et al. Co-inoculation of selected nodule endophytic rhizobacterial strains with Rhizobium tropici promotes plant growth and controls damping off in common bean. Pedosphere. 2020;30:98–108. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(19)60825-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira NS, Matos GF, Meneses CHSG, et al. Interaction of phytohormone-producing rhizobia with sugarcane mini-setts and their effect on plant development. Plant Soil. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11104-019-04388-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo MVB, Burity HA, Martínez CR, Chanway CP. Alleviation of drought stress in the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) by co-inoculation with Paenibacillus polymyxa and Rhizobium tropici. Appl Soil Ecol. 2008;40:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2008.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freire Filho FR. Feijão-caupi no Brasil: produção, melhoramento genético, avanços e desafios. Teresina: Embrapa Meio-Norte; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goel AK, Sindhu SS, Dadarwal KR. Bacteriocin-producing native rhizobia of green gram (Vigna radiata) having competitive advantage in nodule occupancy. Microbiol Res. 1999;154:43–48. doi: 10.1016/S0944-5013(99)80033-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães AA, Florentino LA, Alves KA, et al. High diversity of Bradyrhizobium strains isolated from several legume species and land uses in Brazilian tropical ecosystems. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD, et al. PaSt: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaentologia Electron. 2011;4:5–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hungria M, Nogueira MA, Araujo RS. Co-inoculation of soybeans and common beans with rhizobia and azospirilla: strategies to improve sustainability. Biol Fertil Soils. 2013;49:791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00374-012-0771-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hungria M, Nogueira MA, Araujo RS. Soybean seed co-inoculation with Bradyrhizobium spp. and Azospirillum brasilense: a new biotechnological tool to improve yield and sustainability. Am J Plant Sci. 2015;6:811–817. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2015.66087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez F, Angelini J, Taurian T, et al. Endophytic occupation of peanut root nodules by opportunistic Gammaproteobacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2009;32:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBGE (2019) Censo Agropecuário - 2017. https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/21814-2017-censo-agropecuario.html?edicao=25757&t=resultados. Accessed 14 May 2020

- Jaiswal SK, Dakora FD. Widespread distribution of highly adapted Bradyrhizobium species nodulating diverse legumes in Africa. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:310. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesus EC, de Leite R, Bastos do RA, , et al. Co-inoculation of Bradyrhizobiumstimulates the symbiosis efficiency of Rhizobium with common bean. Plant Soil. 2018;425:201–215. doi: 10.1007/s11104-017-3541-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Machado RG, de Sá ELS, Hahn L, et al. Rhizobia symbionts of legume forages native to South Brazil as promoters of cultivated grass growing. Int J Agric Biol. 2016;18:1011–1016. doi: 10.17957/IJAB/15.0201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marinho RCN, Nóbrega RSA, Zilli JE, et al. Field performance of new cowpea cultivars inoculated with efficient nitrogen-fixing rhizobial strains in the Brazilian Semiarid. Pesqui Agropecu Bras. 2014 doi: 10.1590/S0100-204X2014000500009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marinho RCN, Ferreira LDVM, da Silva AF, et al. Symbiotic and agronomic efficiency of new cowpea rhizobia from Brazilian Semi-Arid. Bragantia. 2017;71:273–281. doi: 10.1590/1678-4499.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martins LMV, Xavier GR, Rangel FW, et al. Contribution of biological nitrogen fixation to cowpea: a strategy for improving grain yield in the semi-arid region of Brazil. Biol Fertil Soils. 2003;38:333–339. doi: 10.1007/s00374-003-0668-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathu S, Herrmann L, Pypers P, et al. Potential of indigenous bradyrhizobia versus commercial inoculants to improve cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) and green gram (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek.) yields in Kenya. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2012;58:750–763. doi: 10.1080/00380768.2012.741041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes KAS, de NunesSampaio GFAA, et al. Diversity of new root nodule bacteria from Erythrina velutina Willd., a native legume from the Caatinga dry forest (Northeastern Brazil) Rev Ciencias Agrárias. 2016;39:222–233. doi: 10.19084/RCA15050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed M, Jaiswal S, Dakora F. Distribution and correlation between phylogeny and functional traits of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.)-nodulating microsymbionts from Ghana and South Africa. Sci Rep. 2018;12:1–19. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36324-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti LG, Crusciol CAC, Kuramae EE, et al. Effects of growth-promoting bacteria on soybean root activity, plant development, and yield. Agron J. 2020;112:418–428. doi: 10.1002/agj2.20010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norris DO, Mannetje L. The symbiotic specialization of African Trifolium spp. in relation to their taxonomy and their agronomic use. East Afr Agric For J. 1964;29:214–235. doi: 10.1080/00128325.1964.11661928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira GS, Sena PTS, Nascimento TR, et al. Are cowpea-nodulating bradyrhizobial communities influenced by biochar amendments in soils? Genetic diversity and symbiotic effectiveness assessment of two agricultural soils of Brazilian drylands. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2020;20:439–449. doi: 10.1007/s42729-019-00128-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osei O, Simões Araújo JL, Zilli JE, et al. PCR assay for direct specific detection of Bradyrhizobium elite strain BR 3262 in root nodule extracts of soil-grown cowpea. Plant Soil. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s11104-017-3271-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez MDA, Espana M, Lewandowska S, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of symbiotic bacteria associated with two Vigna species under different agro-ecological conditions in Venezuela. Microbes Environ. 2020;35:1–13. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME19120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues AC, Antunes JEL, de Medeiros VV, et al. Resposta da co-inoculação de bactérias promotoras de crescimento em plantas e Bradyrhizobium sp. em caupi. Biosci J. 2012;28:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Rondina ABL, dos Santos Sanzovo AW, Guimarães GS, et al. Changes in root morphological traits in soybean co-inoculated with Bradyrhizobium spp. and Azospirillum brasilense or treated with A. brasilense exudates. Biol Fertil Soils. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00374-020-01453-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwinghamer EA. Antagonism between strains of Rhizobium trifolii in culture. Soil Biol Biochem. 1971;3:355–363. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(71)90046-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sena PTS, Nascimento TR, Lino JOS, et al. Molecular, physiological, and symbiotic characterization of cowpea rhizobia from soils under different agricultural systems in the semiarid region of Brazil. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s42729-020-00203-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva FV, Simões-Araújo JL, Silva Jínior JA, et al. Genetic diversity of Rhizobia isolates from Amazon soils using cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) as trap plant. Braz J Microbiol. 2012;43:682–691. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822012000200033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva Júnior EB, Favero VO, Xavier GR, et al. Rhizobium inoculation of cowpea in Brazilian Cerrado increases yields and nitrogen fixation. Agron J. 2018;110:722–727. doi: 10.2134/agronj2017.04.0231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Somasegaran P, Hoben HJ (1994) Methods in legume-Rhizobium technology. In: Garber RC (ed) Handbook for Rhizobia, Spinger Verlag Publications, New York

- Suzuki Y, Adhikari D, Itoh K, Suyama K. Effects of temperature on competition and relative dominance of Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Bradyrhizobium elkanii in the process of soybean nodulation. Plant Soil. 2014;374:915–924. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1924-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira PC, Donagemma GK, Fontana A, Teixeira WG, editors. Manual de métodos de análise de solo. 3. Brasilia: Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Díaz AA, Ferrera-Cerrato R, Silva-Rojas HV, Alarcón A. Isolation and evaluation of endophytic bacteria from root nodules of Glycine max L. (Merr) and their potential use as biofertilizers. Spanish J Agric Res. 2019;17:e1103. doi: 10.5424/sjar/2019173-14220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vicario JC, Primo ED, Dardanelli MS, Giordano W. Promotion of peanut growth by co-inoculation with selected strains of Bradyrhizobium and Azospirillum. J Plant Growth Regul. 2016;35:413–419. doi: 10.1007/s00344-015-9547-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JM. A manual for the practical study of root-nodule bacteria. Hoboken: International Biological Programme/Blackwell Scientific; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier GR, Martins LMV, Neves MCP, Rumjanek NG. Edaphic factors as determinants for the distribution of intrinsic antibiotic resistance in a cowpea rhizobia population. Biol Fertil Soils. 1998;27:386–392. doi: 10.1007/s003740050448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier GR, Runjanek NG, de Santos CE, et al. Agronomic effectiveness of rhizobia strains on cowpea in two consecutive years. Aust J Crop Sci. 2017;11:1154–1160. doi: 10.21475/ajcs.17.11.09.pne715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zilli JÉ, Marson LC, Marson BF, et al. Contribuição de estirpes de rizóbio para o desenvolvimento e produtividade de grãos de feijão- caupi em Roraima. Acta Amaz. 2009;39:749–758. doi: 10.1590/S0044-59672009000400003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.