Abstract

Purpose

Darunavir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide can be used as a single-tablet regimen (STR, DRV/c/FTC/TAF) or multiple-tablet regimen (MTR, DRV/c+FTC/TAF) to treat patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). This study described treatment patterns and predictors of adherence among patients with HIV initiated on DRV/c/FTC/TAF or DRV/c+FTC/TAF.

Patients and Methods

A retrospective longitudinal study was conducted using linked claims and electronic medical records from Decision Resources Group’s Real World Data Repository (7/17/2017–6/1/2019). Treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced virologically suppressed adults with HIV-1 prescribed DRV/c/FTC/TAF or DRV/c+FTC/TAF (index date) were included. Six-month persistence (no treatment gaps >60 and >90 days) and adherence (proportion of days covered [PDC]) to the index regimen were evaluated among patients with ≥6 months of observation post-index. Predictors of low adherence (PDC<80%) were evaluated using a logistic regression model.

Results

Among 2633 eligible patients (49.5 years old, 29% female, 37% African American/Black), 12% were treatment-naïve pre-index and 88% switched from a previous antiretroviral therapy; 84% initiated DRV/c/FTC/TAF and 16% initiated DRV/c+FTC/TAF. Among 822 DRV/c/FTC/TAF patients with ≥6 months of observation post-index, 80% and 86% had no >60- and >90-day gaps in DRV/c/FTC/TAF coverage, respectively, while among 204 DRV/c+FTC/TAF patients with ≥6 months of observation post-index, 69% and 75% had no >60- and >90-day gaps in DRV/c+FTC/TAF coverage, respectively. Mean (median) PDC for the index regimen was 81% (93%) for patients treated with DRV/c/FTC/TAF and 73% (83%) for patients treated with DRV/c+FTC/TAF. Predictors of low adherence included younger age (odds ratio [OR]=2.36, p=0.017), higher Quan-Charlson comorbidity index (OR=1.32, p=0.012), use of MTR regimen at index (OR=1.69, p=0.022), and prior low adherence (OR=2.56, p<0.001).

Conclusion

Among patients initiating a DRV/c-based regimen, those initiating STR had higher 6-month adherence/persistence than those initiating MTR, highlighting the potential benefits of the STR formulation, particularly among younger patients with multiple comorbidities and prior low adherence.

Keywords: HIV, protease inhibitors, treatment adherence and compliance, patient compliance, administrative claims, healthcare, electronic health records

Introduction

While human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) remains ineradicable, the introduction of highly effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) has substantially improved the prognosis of people living with HIV.1 However, ART use remains suboptimal and <60% of HIV patients were reported to be virologically suppressed in 2016 in the United States (US).2,3 More recent estimates are available for smaller groups of patients which exceed the national viral suppression average, such as among those who received medical care from the Ryan White HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) Program whereby 87% reached viral suppression in 2018.4 Nevertheless, a recent real-world study showed a mean proportion of days covered (PDC) of only ~50% among Medicaid and commercially insured patients.5

The recommendation by consensus for patients with HIV was to achieve ≥95% adherence to ART.6–9 Recently, the Pharmacy Quality Alliance, a nationally recognized organization which provides consensus-based measures for medication safety, adherence and appropriate use, recommended ≥90% adherence to be considered as optimal for ART.10 Suboptimal adherence to ART has been associated with an increased risk of virologic failure and drug resistance, resulting in a high burden for the healthcare system.7,11,12 The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines therefore recommend multiple strategies to improve adherence and persistence, including the use of tolerable and less complex ART regimens, such as single-table regimens (STRs).13 Among patients with adherence problems, the DHHS guidelines recommend using a darunavir (DRV)-based regimen because of its high genetic barrier to resistance.13 Approved on 1/29/2015, DRV/cobicistat (DRV/c) is a boosted protease inhibitor (PI) which can be prescribed with emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (FTC/TAF) as a once daily multiple-tablet regimen (MTR) for the treatment of HIV-1 among treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced adults. On 7/17/2018, DRV/c/FTC/TAF (Symtuza®) became the first PI-based STR approved for HIV-1 treatment among treatment-naïve patients and virologically suppressed adults stable on ART for ≥6 months.14

While factors such as race, gender, and social determinants of health play an important role in adherence to ART,15–18 studies show that STRs confer benefits with regards to adherence5,19–27 and persistence25,28–30 compared to MTRs. However, whether DRV/c/FTC/TAF STR improves adherence and persistence compared to the 2-pill MTR formulation with the same components (ie DRV/c+FTC/TAF) remains to be assessed in a real-world setting. Therefore, this study aimed to describe the characteristics and treatment patterns, including adherence and persistence, of patients in the US insured through multiple payer channels and initiated on DRV/c-based STR or MTR, as well as identify predictors of adherence in these patients.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

The Decision Resources Group’s (DRG) Real World Data Repository (7/17/2017–6/1/2019) was used for this study. The database is made up of open source claims data from multiple electronic data interchanges and electronic medical records (EMR) data from a major EMR vendor in the US. DRG’s Real World Data Repository, which includes patients from all states in the US (including beneficiaries of the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Drug Assistance Program), is broadly representative of the entire US population. Of note, reasons for ART discontinuation are not available in the database. Data are de-identified and comply with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). As this was an analysis of claims data, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not required. Per Title 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Part 46.101(b)(4),31 the administrative claims data analysis of this study is exempt from the IRB review for two reasons: (1) it is a retrospective analysis of existing data (hence no patient intervention or interaction), (2) no patient-identifiable information is included in the claims dataset.

Study Design

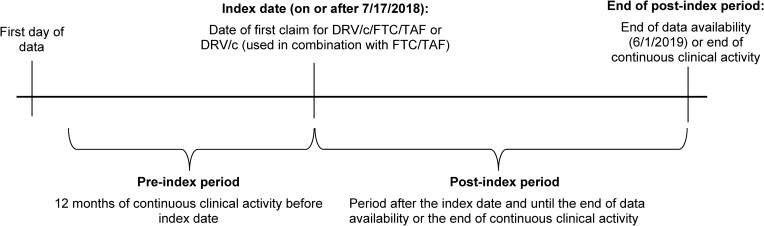

A retrospective longitudinal study design was used (Figure 1). The index date was the date of initiation of DRV/c/FTC/TAF or DRV/c+FTC/TAF on or after 7/17/2018. Priority was given to DRV/c/FTC/TAF followed by DRV/c+FTC/TAF when identifying the index date. For DRV/c+FTC/TAF, the index date was anchored at the date of the first claim for DRV/c, and FTC/TAF had to be claimed within ±14 days of the index date. The pre-index period was the 12-month period of continuous clinical activity before the index date. The post-index period spanned from the index date until the earliest among end of continuous clinical activity or end of data availability. Continuous clinical activity was defined as a consecutive period of time where patients had ≥1 claim in each 3-month interval. Since an intent-to-treat approach was used, patients could switch to another ART regimen during the post-index period.

Figure 1.

Study design scheme.

Abbreviations: c, cobicistat; DRV, darunavir; FTC, emtricitabine; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide.

Study Population

Patients were included if they had ≥1 claim for DRV on or after 7/17/2018, used DRV as part of an ART regimen with c, FTC, and TAF (either DRV/c/FTC/TAF or DRV/c+FTC/TAF), had ≥12 months of continuous clinical activity pre-index, ≥1 claim with a diagnosis for HIV-1 on or before the index date, and were ≥18 years old on the index date. Patients were considered treatment-naïve if they had no claim for ART during the pre-index period, while ART switchers had ≥1 claim for ART during the pre-index period. Patients were excluded if they had history of ART and were not virologically suppressed during the 6-month period pre-index (ie ≥1 viral load test result ≥50 copies/mL during the 6-month period pre-index; viral load test results were obtained from EMR data), or had ≥1 claim with a diagnosis for HIV-2, liver disease, chronic renal insufficiency, pregnancy, or cancer during the 12-month pre-index period.

Study Measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics were described during the 12-month pre-index period. Treatment patterns were evaluated pre-index and over the post-index period (including switch to another ART). Among patients with ≥6 months of continuous clinical activity post-index, persistence to the index regimen was evaluated during the first 6 months post-index using the proportion of patients with no gap >60 and >90 days in index regimen coverage. For patients initiated on DRV/c+FTC/TAF, both DRV/c and FTC/TAF had to be taken to be considered persistent. If one of the medications from the regimen was missing, the patient was considered to have a gap in treatment. If one of the medications from the regimen was missing for >60 or >90 days, the patient was considered non-persistent.

Among patients with ≥6 months of continuous clinical activity post-index and ≥1 ART claim during the 6 months pre- and post-index, adherence to the index regimen during the 6 months post-index and adherence to any ART during the 6 months pre- and post-index were evaluated. Adherence to the index regimen was measured using PDC, defined as the sum of non-overlapping days of supply for the index regimen divided by 6 months. The following PDC thresholds were reported: PDC<80% (non-adherence), PDC≥80% and <95% (suboptimal adherence), PDC≥95% (optimal adherence). Additionally, given the recent change in the recommended adherence threshold,10 PDC≥90% was also reported. For DRV/c+FTC/TAF, PDC by the index regimen was defined as the sum of non-overlapping days during which patients had a simultaneous supply of DRV/c and FTC/TAF.32

Statistical Analysis

Pre-index demographic and clinical characteristics as well as treatment patterns (including adherence and persistence) were descriptively evaluated using means, standard deviations (SDs), and medians for continuous variables, and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to evaluate pre-index predictors of low adherence to the index regimen, defined as PDC for the index regimen <80% at 6 months. Results were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals and p-values.

Results

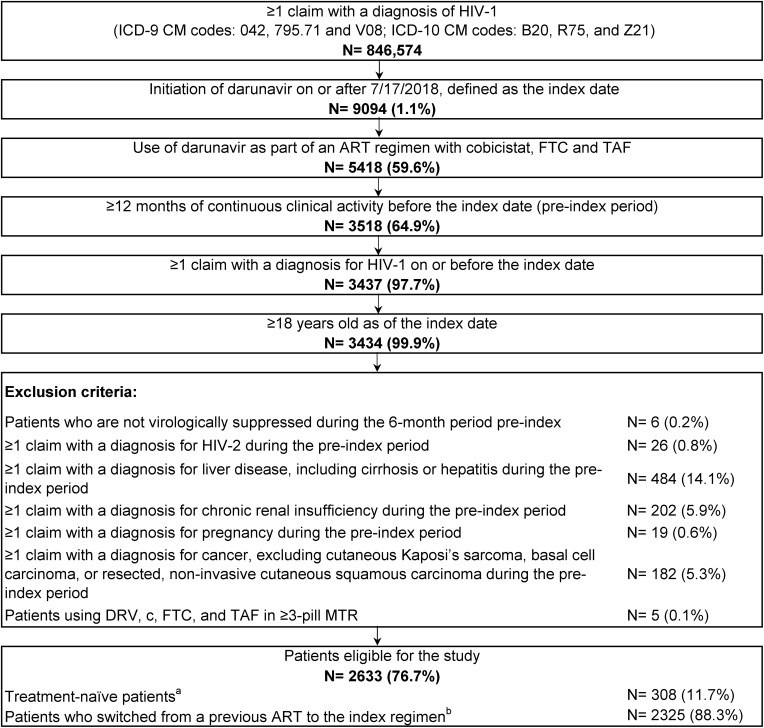

Among 846,574 patients with ≥1 claim with an HIV-1 diagnosis, 2633 were included in the study. A total of 308 (12%) patients were treatment-naïve pre-index and 2325 (88%) switched from a previous ART (Figure 2). At the index date, 2218 (84%) and 415 (16%) patients initiated DRV/c/FTC/TAF and DRV/c+FTC/TAF, respectively. Overall, patients were observed for an average of 148 days (SD=85) post-index.

Figure 2.

Identification of the study population.

Notes:aPatients with no claims for an antiretroviral prior to the index date. bPatients with ≥1 claim for an antiretroviral prior to the index date.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; c, cobicistat; DRV, darunavir; FTC, emtricitabine; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICD-9 CM/ICD-10 CM, International Classification of Disease, Ninth/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification; MTR, multiple-tablet regimen; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide.

Pre-Index Characteristics

During the 12-month pre-index period, mean age was 49.5 years and 29% were female (Table 1). Among 795 (30%) patients with EMR data, 37% were African American/Black; 60% commercially insured, 20% covered by Medicare, and 16% covered by Medicaid. The 5 states with the highest proportions of patients were New York (19%), Florida (13%), Texas (8%), California (8%), and Michigan (6%). The mean time from first HIV diagnosis to index date was 53.6 months among patients with available information on HIV disease onset (N=196 [7%]). The mean Quan-Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score33 (excluding HIV symptoms) was 0.5. Hypertension (30%), substance-related and addictive disorders (24%), depression (17%), chronic pulmonary disease (17%), and anxiety (13%) were commonly observed comorbidities. Characteristics were similar for patients initiated on DRV/c/FTC/TAF (mean age: 49.7 years; 28.8% female; 36.9% African American/Black) and DRV/c+FTC/TAF (mean age: 48.5 years; 33.0% female; 38.3% African American/Black).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics in the 12-Month Pre-Index Period

| Patient Characteristics | All Patients |

|---|---|

| N= 2633 | |

| Age at index date (years), mean ± SD [median] | 49.5 ± 11.8 [51.0] |

| Female, n (%) | 775 (29.4) |

| Patients in EMR data, n (%) | 795 (30.2) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| African American/Black | 295 (37.1) |

| White | 190 (23.9) |

| Hispanic | 31 (3.9) |

| Other | 6 (0.8) |

| Unknown | 273 (34.3) |

| US geographic regiona, n (%) | |

| South | 1135 (43.1) |

| Florida | 339 (12.9) |

| Texas | 213 (8.1) |

| Northeast | 666 (25.3) |

| New York | 489 (18.6) |

| Midwest | 388 (14.7) |

| Michigan | 155 (5.9) |

| West | 387 (14.7) |

| California | 202 (7.7) |

| Unknown | 57 (2.2) |

| Insurance plan/payer typea, n (%) | |

| Commercial plans | 1574 (59.8) |

| Medicare | 526 (20.0) |

| Medicaid | 426 (16.2) |

| Other | 68 (2.5) |

| Unknown | 39 (1.5) |

| Year of index date, n (%) | |

| 2018 | 1274 (48.4%) |

| 2019 | 1359 (51.6%) |

| Patients with HIV disease onset information in EMR data, n (%) | 196 (7.4) |

| Time (in months) between HIV disease onset and index date, mean ± SD [median] | 53.6 ± 77.0 [28.2] |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 778 (29.5) |

| Substance-related and addictive disorders | 624 (23.7) |

| Depression | 456 (17.3) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 456 (17.3) |

| Drug abuse | 370 (14.1) |

| Anxiety disorders | 353 (13.4) |

| Obesity | 315 (12.0) |

| Type II diabetes | 301 (11.4) |

| Psychoses | 293 (11.1) |

| Opportunistic infections | 61 (2.3) |

| Quan-CCI, mean ± SD [median] | 4.7 ± 3.1 [6.0] |

| Quan-CCI (excluding HIV symptoms), mean ± SD [median] | 0.5 ± 1.0 [0.0] |

Note: aEvaluated on the date closest to the index date.

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; EMR, electronic medical records; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SD, standard deviation; US, United States.

Treatment Patterns

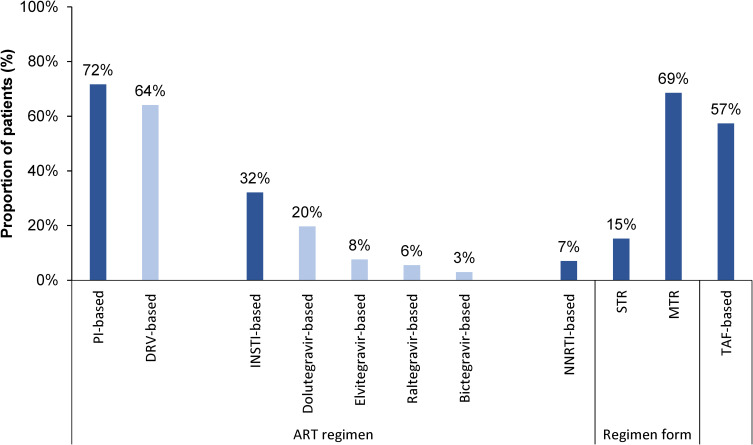

During the pre-index period, 72% of the 2633 patients received a protease inhibitor (PI)-based regimen, including 64% who received a DRV-based regimen; 32% received an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI)-based regimen, 7% received a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)-based regimen, and 57% had TAF as a component in their ART regimen (Figure 3). During the post-index period, 25% of patients switched to an INSTI-based regimen and 4% switched to an NNRTI-based regimen following the index regimen. The proportion of patients using STR during the pre-index period was 15%, and increased to 86% on or following the index date. The proportion of patients using MTR during the pre-index period was 69%, and decreased to 43% on or following the index date.

Figure 3.

ART regimens received during the 12-month pre-index period.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; DRV, darunavir; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; MTR, multiple-tablet regimen; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; STR, single-tablet regimen; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide.

Persistence to Index ART

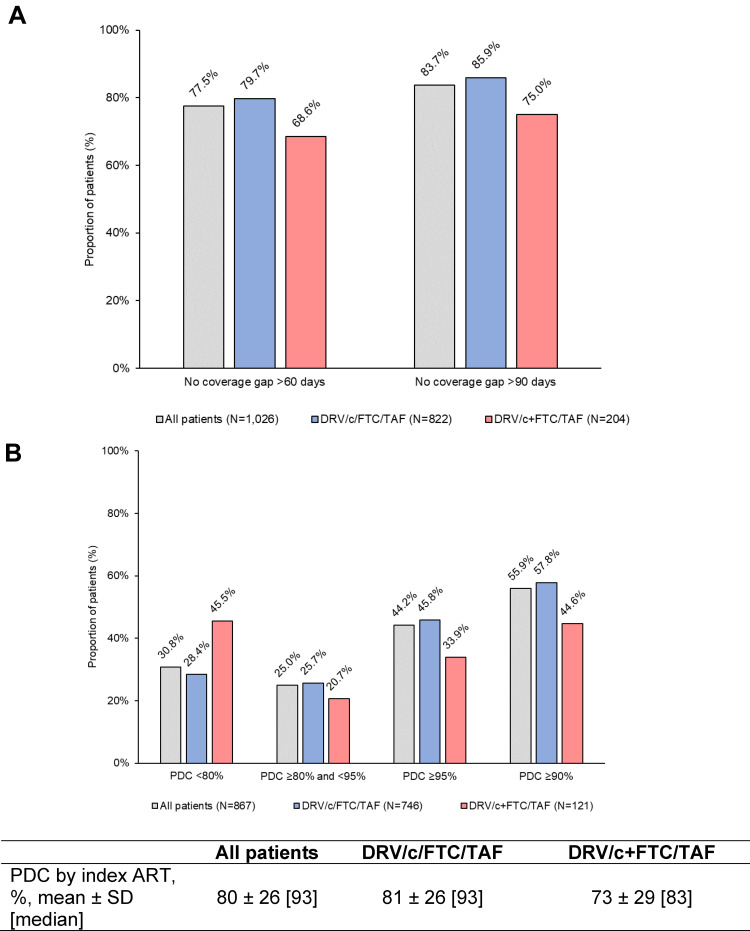

Among 1026 patients with ≥6 months of continuous clinical activity post-index, 78% had no gap in index regimen coverage for >60 days and 84% had no gap in index regimen coverage for >90 days (Figure 4A). Persistence was higher among DRV/c/FTC/TAF users than DRV/c+FTC/TAF users, as seen by the larger proportion of DRV/c/FTC/TAF users without coverage gaps >60 days (DRV/c/FTC/TAF=80% and DRV/c+FTC/TAF=69%) and >90 days (DRV/c/FTC/TAF=86% and DRV/c+FTC/TAF=75%).

Figure 4.

(A) Persistence and (B) adherence to the index ART regimen during the first 6 months post-index.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; c, cobicistat; DRV, darunavir; FTC, emtricitabine; PDC, proportion of days covered; SD, standard deviation; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide.

Adherence to Index ART Regimen and to Any ARTs

Among 867 patients with ≥6 months of continuous clinical activity post-index and ≥1 ART claim during the 6 months pre- and post-index, 86% were initiated on DRV/c/FTC/TAF and 14% on DRV/c+FTC/TAF. Mean (median) PDC by index ART was 81% (93%) among DRV/c/FTC/TAF users and 73% (83%) among DRV/c+FTC/TAF users post-index. Non-adherence (ie PDC<80%) was more common among DRV/c+FTC/TAF users (46%) than DRV/c/FTC/TAF users (28%; Figure 4B). Optimal adherence (ie PDC≥95%) was more common among DRV/c/FTC/TAF users (46%) than DRV/c+FTC/TAF users (34%). Similarly, the proportion of patients with PDC≥90% was higher among DRV/c/FTC/TAF users (58%) than DRV/c+FTC/TAF users (45%).

Among the 867 patients identified for the evaluation of PDC, mean (median) PDC by any ART increased from 77% (86%) during the 6-month pre-index period to 89% (97%) during the 6-month post-index period, with most of the observed PDC post-index being associated with the use of the index regimen (ie DRV/c/FTC/TAF or DRV/c+FTC/TAF; mean [median] PDC by index ART=80% [93%]). The proportion of patients with a PDC <80% by any ART decreased from 36% during the 6-month pre-index period to 17% during the 6-month post-index period, the proportion of patients with a PDC≥80% and <95% decreased from 43% to 26%, and the proportion of patients with a PDC≥95% increased from 21% to 57%. Similarly, the proportion of patients with PDC≥90% increased from 38% pre-index to 69% post-index.

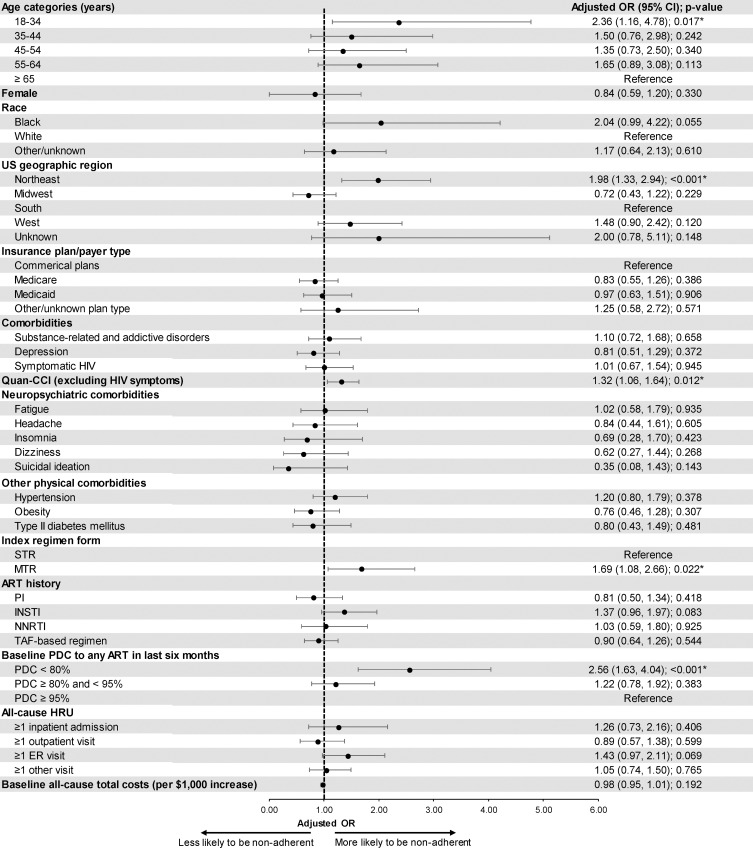

Predictors of Low Adherence

The odds of non-adherence were significantly higher among patients aged 18–34 years (adjusted OR=2.36, p=0.017), patients residing in the Northeast region (adjusted OR=1.98, p<0.001), patients with a higher Quan-CCI (adjusted OR=1.32, p=0.012), patients initiated on an MTR at the index date (adjusted OR=1.69, p=0.022), and patients with a PDC to any ART <80% during the 6 months pre-index (adjusted OR=2.56, p<0.001; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Predictors of low adherence.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; ER, emergency room; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HRU, healthcare resource utilization; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; MTR, multiple-tablet regimen; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; OR, odds ratio; PDC, proportion of days covered; PI, protease inhibitor; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; STR, single-tablet regimen; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; US, United States.

Discussion

This study is the first to assess real-world persistence and adherence associated with DRV/c/FTC/TAF or DRV/c+FTC/TAF. Included patients represented a diverse population (ie 37% African American/Black, 29% females, 16% Medicaid) with various comorbidities. The majority of patients used DRV/c/FTC/TAF and had previously received another ART. On average, patients initiated treatment 53.6 months (4.5 years) after their first HIV diagnosis.

Patients using STR had higher persistence and adherence to the index regimen than those using MTR, consistent with prior studies.25,28–30 Regardless of the drug formulation, persistence rates remained high 6 months after the index date, corroborating adherence results for treatment-naïve patients rapidly initiated on DRV/c/FTC/TAF in the DIAMOND study, where mean (median) adherence as measured by pill count was 95% (99%) over a 48-week study period.34 Post-index, a higher proportion of patients achieved PDC≥95% or PDC≥90% with DRV/c/FTC/TAF than with DRV/c+FTC/TAF, consistent with previous literature showing that adherence is higher with STRs than MTRs,5,19–27,30,35 even when the components of the regimens are the same, as is the case in the current study (2-pill MTR versus STR). Additionally, >50% of patients achieved PDC to any ART ≥95%, higher than the 14–20% who achieved this threshold in a previous study.5 Given the known association between optimal adherence and lower rates of drug resistance and virologic failure7, the results of this study suggest that DRV/c/FTC/TAF may help decrease these risks.11,12 The proportion of patients achieving PDC to any ART ≥95% at 6 months substantially increased from pre- to post-index (21% vs 57%). While many demographic factors may impact adherence, evidence from prior published work suggests that one challenge that may prevent a higher proportion of patients from reaching PDC≥95% is weight gain, which has been associated with some ART regimens such as INSTIs36–39 (in the current study, 32% of patients previously received an INSTI-based ART regimen). Weight gain has been shown to further compound non-adherence issues40 and lead to an increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.41

Predictors of non-adherence were aligned with previous literature. Younger patients aged 18–34 years were more likely to be non-adherent to their index ART regimen than older patients, similar to a previous study.16 African American/Black patients were also associated with a strong – though borderline statistically non-significant – increase in the odds of non-adherence compared with White patients (OR=2.04, p=0.055). This result validates a previous study in which race was associated with a near-significant difference in self-reported adherence to ART (p=0.0558),15 and another which reported the odds of 100% medication adherence were 40% lower among African Americans/Black patients compared to White patients.17 Furthermore, the observation that patients with a higher Quan-CCI had higher odds of non-adherence is consistent with a previous study showing that the use of medications for other comorbidities in addition to ART was a predictor of ART non-adherence.42 Together, our data suggest that greater consideration for STRs should be placed among the younger, non-White patients (representing the majority of new HIV diagnoses in the US)43 who have multiple comorbidities. The multivariable analysis also confirmed that receiving DRV/c+FTC/TAF was associated with significantly higher odds of non-adherence than receiving DRV/c/FTC/TAF. Other factors that could potentially impact adherence and persistence to ART but could not be assessed in this claims database are social and behavioral traits.

This study is subject to certain limitations. First, it was descriptive in nature and did not adjust for potential differences in characteristics between patients initiated on DRV/c/FTC/TAF or DRV/c+FTC/TAF. Indeed, some differences may exist between the two patient groups which could influence their adherence and persistence to ART. Second, DRG is a provider-based data source that does not capture the services patients received from a provider that is outside of the network. However, even if patients change providers to obtain different medications, they tend to obtain all claims for the same medication through a single provider. Third, as with all claims data sources, DRG’s Real World Data Repository may contain inaccuracies or omissions in diagnoses, billing, and other variables. Fourth, since the study was conducted on US patients, the results may not be generalizable to patients in other countries as there may be differences in patient characteristics, treatment practices, and healthcare systems. Finally, ART claims are assumed to indicate their use; however, patients may not adhere to the treatment regimen as prescribed.

Conclusion

In the current study, >85% of patients were treatment-experienced and switched from a previous ART. Adherence to any ART increased following the initiation of DRV/c/FTC/TAF or DRV/c+FTC/TAF and 6-month persistence and adherence were higher for the STR DRV/c/FTC/TAF than for the 2-pill MTR DRV/c+FTC/TAF. Predictors of low adherence included younger age, higher Quan-CCI, initiation of an MTR regimen on the index date, and low adherence to previous ART regimens. Further research with longer follow-up period is needed to confirm persistence and adherence trends over time.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by Samuel Rochette, MSc, and Loraine Georgy, PhD, employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The sponsor was involved in the study design, interpretation of results, manuscript preparation, and publication decisions.

Abbreviations

ART, antiretroviral therapy; c, cobicistat; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CFR, Code of Federal Regulations; CI, confidence interval; DHHS, US Department of Health and Human Services; DRG, Decision Resources Group; DRV, darunavir; EMR, electronic medical record; ER, emergency room; FTC, emtricitabine; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HRU, healthcare resource utilization; ICD-9 CM, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification; ICD-10 CM, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; IRB, Institutional Review Board; MTR, multi-tablet regimen; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; OR, odds ratio; PDC, proportion of days covered; PI, protease inhibitor; SD, standard deviation; STR, single-tablet regimen; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; US, United States.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from DRG but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used pursuant to a data use agreement. The data are available through requests made directly to DRG, subject to DRG’s requirements for data access.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

Data are de-identified and comply with the patient requirements of the HIPAA. As this was an analysis of claims data, IRB approval was not required. Per Title 45 of the CFR, Part 46.101(b)(4),31 the administrative claims data analysis of this study is exempt from the IRB review for two reasons: (1) it is a retrospective analysis of existing data (hence no patient intervention or interaction), (2) no patient-identifiable information is included in the claims dataset.

Consent for Publication

All authors confirm that the contents of this manuscript can be published.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Dr Wing Chow is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, during the conduct of the study; and owns stocks/shares at Johnson & Johnson, outside the submitted work. Ms Prina Donga is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. Ms Aurélie Côté-Sergent is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. Dr Carmine Rossi is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. Mr Patrick Lefebvre is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript, and funded additional HIV researches in the past 36 months. Ms Marie-Hélène Lafeuille is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company, that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC to conduct this study; and has provided paid consulting services to Pharmacyclics and GlaxoSmithKline, outside the submitted work. Dr Hélène Hardy is an employee of Johnson and Johnson. Mr Bruno Emond is an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(8):e349–e356. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30066-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Z, Purcell DW, Sansom SL, Hayes D, Hall HI. Vital signs: HIV transmission along the continuum of care - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(11):267–272. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6811e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HIV Care Continuum. What does the HIV care continuum show? 2020. Available from: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/policies-issues/hiv-aids-care-continuum. Accessed May13, 2020.

- 4.Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. Annual Client-Level Data Report. 2018.

- 5.Kangethe A, Polson M, Lord TC, Evangelatos T, Oglesby A. Real-world health plan data analysis: key trends in medication adherence and overall costs in patients with HIV. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(1):88–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forstein M, Cournos F, Douaihy A, Goodkin K, Wainberg ML, Wapenyi KH. Guideline Watch: Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients with HIV/AIDS. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wutoh AK, Elekwachi O, Clarke-Tasker V, Daftary M, Powell NJ, Campusano G. Assessment and predictors of antiretroviral adherence in older HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(Suppl 2):S106–114. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies G, Koenig LJ, Stratford D, et al. Overview and implementation of an intervention to prevent adherence failure among HIV-infected adults initiating antiretroviral therapy: lessons learned from Project HEART. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8):895–903. doi: 10.1080/09540120500329556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pharmacy Quality Alliance. PQA measure overview; 2019. Available from: https://www.pqaalliance.org/assets/Measures/2019_PQA_Measure_Overview.pdf. Accessed April29, 2020.

- 11.Harrigan PR, Hogg RS, Dong WW, et al. Predictors of HIV drug-resistance mutations in a large antiretroviral-naive cohort initiating triple antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(3):339–347. doi: 10.1086/427192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meresse M, March L, Kouanfack C, et al. Patterns of adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV drug resistance over time in the Stratall ANRS 12110/ESTHER trial in Cameroon. HIV Med. 2014;15(8):478–487. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. Available from: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arv/37/whats-new-in-the-guidelines. Accessed January24, 2020.

- 14.US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing information - SYMTUZA®; 2019. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/210455s004lbl.pdf. Accessed November22, 2019.

- 15.Beer L, Skarbinski J. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults in the United States. AIDS Educ Prev. 2014;26(6):521–537. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2014.26.6.521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Lee E, Park BJ, Bang JH, Lee JY. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and factors affecting low medication adherence among incident HIV-infected individuals during 2009–2016: a nationwide study. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):3133. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21081-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simoni JM, Huh D, Wilson IB, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities in ART adherence in the United States: findings from the MACH14 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(5):466–472. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825db0bd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross IM, Hosek S, Richards MH, Fernandez MI. Predictors and profiles of antiretroviral therapy adherence among african american adolescents and young adult males living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(7):324–338. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altice F, Evuarherhe O, Shina S, Carter G, Beaubrun AC. Adherence to HIV treatment regimens: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:475–490. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S192735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakraborty A, Qato DM, Awadalla SS, Hershow RC, Dworkin MS. Antiretroviral therapy adherence among treatment-naive HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2020;34(1):127–137. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Chen K, Kalichman SC. Barriers to HIV medication adherence as a function of regimen simplification. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(1):67–78. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9827-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clay PG, Yuet WC, Moecklinghoff CH, et al. A meta-analysis comparing 48-week treatment outcomes of single and multi-tablet antiretroviral regimens for the treatment of people living with HIV. AIDS Res Ther. 2018;15(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12981-018-0204-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hines DM, Ding Y, Wade RL, Beaubrun A, Cohen JP. Treatment adherence and persistence among HIV-1 patients newly starting treatment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1927–1939. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S207908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohd Salleh NA, Richardson L, Kerr T, et al. A longitudinal analysis of daily pill burden and likelihood of optimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV who use drugs. J Addict Med. 2018;12(4):308–314. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raffi F, Yazdanpanah Y, Fagnani F, Laurendeau C, Lafuma A, Gourmelen J. Persistence and adherence to single-tablet regimens in HIV treatment: a cohort study from the French National Healthcare Insurance Database. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(7):2121–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutton SS, Hardin JW, Bramley TJ, D’Souza AO, Bennett CL. Single- versus multiple-tablet HIV regimens: adherence and hospitalization risks. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(4):242–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yager J, Faragon J, McGuey L, et al. Relationship between single tablet antiretroviral regimen and adherence to antiretroviral and non-antiretroviral medications among veterans’ affairs patients with human immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017;31(9):370–376. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cotte L, Ferry T, Pugliese P, et al. Effectiveness and tolerance of single tablet versus once daily multiple tablet regimens as first-line antiretroviral therapy - Results from a large french multicenter cohort study. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis JM, Smith C, Torkington A, et al. Real-world persistence with antiretroviral therapy for HIV in the United Kingdom: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. J Infect. 2017;74(4):401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen J, Beaubrun A, Bashyal R, Huang A, Li J, Baser O. Real-world adherence and persistence for newly-prescribed HIV treatment: single versus multiple tablet regimen comparison among US medicaid beneficiaries. AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12981-020-00268-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Department of Health and Human Services. Human research protections: regulations and policy. Available from: www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html#46.101. Accessed July15, 2020.

- 32.American Pharmacists Association. Measuring adherence. Available from: https://www.pharmacist.com/measuring-adherence. Accessed January24, 2020.

- 33.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hardy H, Luo D, Israel D, Simonson RB, Dunn K. Treatment adherence and virologic response over 48 weeks among patients rapidly initiating darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (D/C/F/TAF) in the DIAMOND study [Poster 606]. Presented at: 14th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence17–19 June 2019; Miami, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sax PE, Meyers JL, Mugavero M, Davis KL, Ross JS. Adherence to antiretroviral treatment and correlation with risk of hospitalization among commercially insured HIV patients in the United States. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourgi K, Rebeiro PF, Turner M, et al. Greater weight gain in treatment naive persons starting dolutegravir-based antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karam M, Laurence B, Ricky H, et al. Changes in BMI associated with antiretroviral regimens in treatment-experienced, virologically suppressed individuals living with HIV. Presented at: IDWeek2019; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerchberger AM, Sheth AN, Angert CD, et al. Weight gain associated with integrase stand transfer inhibitor use in women. Clin Infect Dis. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norwood J, Turner M, Bofill C, et al. Brief report: weight gain in persons with HIV switched from efavirenz-based to integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based regimens. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76(5):527–531. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plankey M, Bacchetti P, Jin C, et al. Self-perception of body fat changes and HAART adherence in the women’s interagency HIV study. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(1):53–59. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9444-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar S, Samaras K. The impact of weight gain during HIV treatment on risk of pre-diabetes, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:705. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cantudo-Cuenca MR, Jimenez-Galan R, Almeida-Gonzalez CV, Morillo-Verdugo R. Concurrent use of comedications reduces adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(8):844–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2018 (Preliminary); vol. 30; 2019. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed April29, 2020.