Highlights

-

•

Acute appendicitis and appendiceal diverticulosis can present with pain in the right lower quadrant, which makes differential diagnosis difficult.

-

•

Preoperative imaging tests do not contribute to the definitive diagnosis because the diagnosis is mainly determined by the histological study.

-

•

The perforation rate of appendicitis diverticulitis is four times higher than the perforation rate of acute appendicitis.

-

•

In addition, there may be a risk of developing peritoneal pseudomyxoma in some patients with appendiceal diverticulosis.

-

•

Laparoscopic appendectomy is considered a safe and appropriate treatment for simple appendiceal diverticulitis.

Keywords: Appendiceal diverticulum perforated, Appendicitis

Abstract

Background

Appendiceal diverticulosis disease is a rare entity. An perforated appendiceal diverticulosis mimicking acute appendicitis is a extremely unusual surgical finding and the reported prevalence is between 0.014 and 3.7%.

Case report

We report the case of an elderly man, who presented with a typical clinical image of acute appendicitis and underwent laparoscopic surgery. Intraoperative an acute appendicitis with localized peritonitis was identified and a laparoscopic appendectomy was performed, but pathologic analysis demonstrated a type 2 appendiceal diverticulitis.

Conclusion

Appendiceal diverticulosis disease should be included in differential diagnosis of patients presenting with clinical signs of an acute appendicitis and prompt surgical treatment is essential in order to avoid severe complications.

1. Introduction

Appendiceal diverticulosis disease is a rare entity. The first description was published by the pathologist Kelynack in 1893 [1]. The reported prevalence is between 0.014 and 3.7% [2,3]. The size of most appendiceal diverticulosis is less than 0.5 cm. Therefore, they can be easily neglected during macroscopic examination [4]. Acute appendicitis is the most common appendix disease. Both acute appendicitis and appendiceal diverticulosis can present with pain in the right lower quadrant, which makes differential diagnosis difficult.This condition may be associated with neuroendocrine tumours (carcinoids), mucinous adenomas, tubular adenomas and adenocarcinomas [4]. There is no association between colon diverticulosis and appendiceal diverticulosis [2]. A case of perforated appendiceal diverticulosis mimicking acute appendicitis is reported, diagnosed only in postoperative surgery based on histopathological features.

2. Case presentation

A previously healthy 68-year-old man presented to the emergency department because of an 5- day history of bandlike lower abdominal pain. The pain was progressive in severity and was associated with constipation and fever. Physical examination revealed a man with a toxic appearance in moderate distress with a temperature of 38 °C.

The abdomen was soft with bilateral lower quadrant tenderness, worse on the right than on the left side. The leukocyte count was 14 × 109/L The computed tomography CT with intravenous und rectal contrast shows the full length of a distended appendix, appendiceal wall thickening with enhancement, periappendiceal free fluid, findings that indicate appendicitis (Fig. 1Fig. 1,2). Diverticula of the sigmoid colon was highlighted, but without signs of inflammation.

Fig. 1,2.

Abdominal computed tomography demonstrating enlarged appendix in diameter and periappendiceal free fluid..

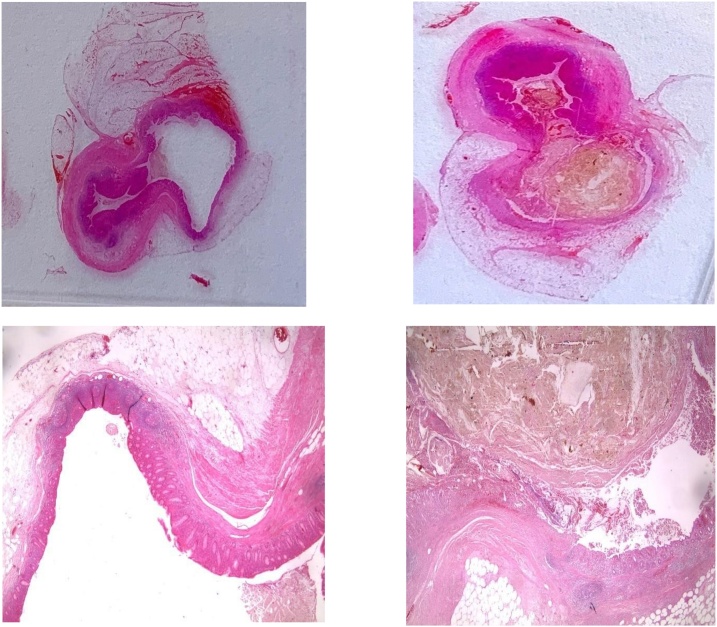

After the radiological diagnosis the patient was transferred to the operating room. Intraoperative an acute appendicitis with localized peritonitis was identified and a laparoscopic appendectomy was performed, but pathologic analysis demonstrated a type 2 appendiceal diverticulitis; histologically, a single appendiceal diverticulum was identified, with acute inflammation and perforation. A neutrophil infiltration was also identified in the appendicular mucosa as a sign of acute inflammation (Fig. 3Fig. 3,4,5,6). The patient was treated for 6 days with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, and he recovered without complications.

Figs. 3,4,5,6.

Histological section of appendiceal diverticulum at the tip of the appendix. Herniation of appendiceal mucosa through muscularis propria in an perforated diverticulum..

3. Discussion

Although acute appendicitis is one of the most common acute abdominal conditions [12], diverticulosis of the appendix is an uncommon entity [13]. Similar to diverticula occurring in other parts of the intestine, these can be classified as congenital or acquired. Congenital diverticula tend to be single and located at the antimesenteric margin of the appendix, while acquired cases tend to be multiple and located at the mesenteric border, most commonly at the distal third of the appendix and are usually small in size (2–5 mm). Several risk factors are associated with acquired appendiceal diverticulosis. These include male sex, an age older than 30 years, and a diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease or cystic fibrosis. Patients are typically diagnosed with cystic fibrosis at adolescence (on average at 13 years) and have up to a 14% incidence of acquired appendiceal diverticulosis [2]. Congenital diverticulosis has also been associated with other diseases such as Down syndrome or Patau syndrome [5]. True diverticulosis, which is rarer (incidence 0.014%), contains all layers of the intestinal wall while in acquired cases it lacks a muscle layer [2,6]. The average age of patients with congenital diverticulosis is 31 years and the average age of patients with acquired diverticulosis is 37 years. Multiple diverticulosis is present in patients with acquired diverticulosis, while only one diverticulum has been identified in people with congenital diverticulosis [2]. Appendiceal diverticulosis can be complicated by inflammation and morphologically classified into four types depending on whether the inflammatory process involves the diverticulum and/or appendix (Table 1).

Table 1.

Four morphological types of diverticular disease of the appendix [2].

| Type 1 | Appendiceal diverticulitis + normal appendix |

| Type 2 | Appendiceal diverticulitis + acute appendicitis |

| Type 3 | Uncomplicated diverticulum + acute appendicitis |

| Type 4 | Uncomplicated diverticulum + normal appendix |

In 1989, Lipton et al. [8] reported the morphological classification of diverticular disease of the caecal appendix. There are 4 different types, and type I (classical) is themost frequent, with a prevalence of around 40–50%.

The perforation of acquired diverticulosis occurs quite easily (up to 66% of cases) due to the lack of a layer of the muscularis propria. Congenital diverticulosis have a thick muscle layer (i.e. muscularis propria) and therefore do not perforate easily (perforation occurs only in 6.6% of cases). Increased intraluminal pressure in an intra-abdominal appendix is believed to be the pathological mechanism underlying the development of acquired diverticula [6].

On examining the pathogenesis of congenital diverticula, Favara et al. found that trisomy 13 e 21 affected seven of eight congenital diverticulum patients [13]. This suggests the importance of genetic or chromosomal factors. Other possible mechanisms include failed recanalization of the appendiceal lumen, duplication of the appendix, remnants of epithelial inclusion cysts in the appendiceal wall, failed obliteration of the vitelline duct, and wall traction caused by adhesions [14].

Hypotheses on the development of acquired diverticula advocate either inflammatory causes or advocate noninflammatory causes. The inflammation hypothesis states that several episodes of inflammation or infection lead to atrophy of lymphoid tissues, resulting in a weaker and thinner residual wall [2]. The noninflammation hypothesis holds that increased intraluminal pressure causes acquired diverticula to develop [2]. The combination of luminal obstruction and muscular contractions drive this development. Secondary obstructions after inflammation, stricture, fecaliths, and tumors cause increases in muscular activity and luminal pressure [2]. Nearly 60% of diverticula are located in the distal third of the appendix [4].

Diverticules accompanying epithelial neoplasms have been reported in literature. Dupre et al. [4] demonstrated a statistically significant association between the presence of diverticulosis of the vermiform appendix and neoplasms (47.8%), especially carcinoid tumours and mucinous adenomas [8]. In the Medlicott and Urbanski series, a primary appendiceal neoplasm was detected in 30% of acquired diverticulosis cases [7]. In the study of Lamps et al. diverticules were determined in 8 out of 19 patients with low-grade mucinous neoplasm (LGMN) (42%) [9]. Marcacuzco et al. in their study reported appendiceal neoplasm in 7.1% [11] of a total of 42 (0.59%) patients with appendix-associated diverticulum. In the study Pasaglou et al. [10] they found accompanying diverticula in 23 out of 38 cases of LGMN (60.5%). The diverticula were coated with neoplastic epithelium in all cases. One of the reasons for this coexistence could be the increased intraluminal pressure caused by the production of mucin, which thinned the musculature itself and caused the mucinous epithelium to proliferate through weak points where vessels penetrate. The other possible cause is the development of LGMN in the pre-existing diverticulum. Also in the Pasaglou study [10] pools of serosal and/or mesoappendicular mucin were detected in 78.3% of cases with diverticulum and 33.3% of NGMLs without diverticula, and this difference was statistically significant. Detecting the accumulation of mucin on the mesoappendix in cases of LGMN with diverticulum more frequently, has led to the hypothesis that diverticulosis may play a role in the pathogenesis of periappendicular mucin deposition and peritoneal pseudomyxoma. The rupture of a diverticulum may cause mucin losses in the intraabdominal space and may be the basis for the development of a pseudomyxoma.

There are very few studies that study the relationship between diverticulum rupture in LGMNs and pseudomyxoma peritoneas. In the study by Lamps et al. the accumulation of acellular mucin was detected around the inflamed and perforated diverticulum in three out of eight LGMNs. However, no accumulation of mucin was observed on the serosal surface or mesoappendix [9]. Of the 13 cases reported by Pasaglou, which showed mucin accumulation on the mesoappendix and monitored over a period of eight months to seven years, none developed pseudomyxoma peritoneum. In the study by Lamps et al., diverticulum rupture was related to pseudomyxoma peritoneum in only one case [9]. The incidence of neoplasms associated with diverticular disease was 7.1% in the study by Marcacuzo et al. [11]. Moreover, there are studies, such as the article by Stockl et al., that report a 42% association between the presence of Schwann cell proliferation in the mucosa and the presence of appendiceal diverticulitis [20]. Distinguishing appendicular diverticulitis from acute appendicitis is difficult; however, some differences have been observed. Compared to appendicitis symptoms, symptomatic appendicitis diverticulitis has a longer duration of pain (1–14 days); it develops mainly in adults (over 30 years of age); it has a lower frequency of accompanying abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting; and it has a greater presence of pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant [2,15]. The complications of appendiceal diverticulitis vary from chronic pain, acute inflammation and perforation to the risk of developing neoplasms [7]. It is curious that the age and incidence of perforation of an inflamed diverticulum are greater in type I than in the rest. 42% of low-grade mucinous neoplasms of the appendix are associated with this disease, so it is therefore recommended that all appendectomy specimenss that present diverticula be thoroughly examined to exclude concomitant neoplastic disease [[16], [17], [18]]. Image studies can facilitate preoperative diagnosis. However, CT imaging results (e.g., appendecular thickening, pericardial inflammation, abscess, phlegmone and increased pericardial fat density) have not sufficiently distinguished appendecular diverticulitis from cecal diverticulitis or appendicitis [13]. Many authors believe that multidetector CT can be very useful because it has detected acute appendiceal diverticulitis in 86% of cases with pathologically confirmed appendiceal diverticulitis [19,20]. According to other authors [21,22], preoperative imaging tests do not contribute to the definitive diagnosis because the diagnosis is mainly determined by the histological study.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, appendiceal diverticulosis disease is generally an accidental finding. Appendiceal diverticulosis debuts with abdominal pain in the right iliac fossa, with symptoms in the acute phase that are indistinguishable from those of acute appendicitis.

The preferred treatment is appendectomy. For symptomatic appendiceal diverticulosis, an appendectomy is the optimal treatment. Regardless of whether or not patients have symptoms, most surgeons suggest prophylactic appendectomy because, even in patients without symptoms, the risk of perforation and mortality is higher in these patients than in the general population [2]. The perforation rate of appendicitis diverticulitis is four times higher than the perforation rate of acute appendicitis [2]. The mortality rate is 30 times higher in patients with perforated appendicitis compared to patients with uncomplicated appendicitis [2]. In addition, there may be a risk of developing peritoneal pseudomyxoma in some patients with appendiceal diverticulosis as they have a higher incidence of appendiceal mucinous tumors. Laparoscopic appendectomy is considered a safe and appropriate treatment for simple appendiceal diverticulitis.

SCARE checklist

The work has been reported in line with the SCARE checklist [23].

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Sources of funding

No source of funding or sponsors.

Ethical approval

This is a Case Report for which the patient provided written informed consent.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Authors contribution

Michele Fiordaliso: Study design, data collection, writing.

Flavia Antonia De Marco: Data collection, writing.

Raffaele Costantini: Data collection, writing.

Michele Fiordaliso: Writing, study design, Surgeon, who performed the operation.

All authors have approved the final article.

Registration of research studies

N/A.

Guarantor

Michele Fiordaliso.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Contributor Information

Michele Fiordaliso, Email: michele.fiordaliso@gmail.com.

Antonia Flavia De Marco, Email: flavia91189@hotmail.it.

Raffaele Costantini, Email: rcostantini@unich.it.

References

- 1.Kelynack A. Lewis HK; London, UK: 1893. Contribution to the Pathology of the Vermiform Appendix. 60–1 [Google Scholar] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AbdullGaffar B. Diverticulosis and diverticulitis of the appendix. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2009;17:231–237. doi: 10.1177/1066896909332728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins D.C.A. Study of 50,000 specimens of the human vermiform appendix. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1955;101:437–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dupre M.P., Jadavji I., Matshes E., Urbanski S.J. Diverticular disease of the vermiform appendix: a diagnostic clue to underlying appendiceal neoplasm. Hum. Pathol. 2008;39:1823–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.06.001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escobar F., Valentín N., Valbuena E., Barón M. Diverticulitis apendicular, revisión de la literatura científica y presentación de 2 casos. Rev. Colomb. Cir. 2013;28:223–228. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgiou G.K., Bali C., Theodorou S.J. Appendiceal diverticulitis in a femoral hernia causing necrotizing fasciitis of the right inguinal region: report of a unique case. Hernia. 2013:125–128. doi: 10.1007/s10029-011-0822-0. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medlicott S.A.C., Urbanski S.J. Acquired diverticulosis of the vermiform appendix. A disease of multiple etiologies. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020;6:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipton S., Estrin J., Glasser I. Diverticular disease of the appendix. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1986;168:13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamps L.W., Gray G.F., Dilday B.R. The coexistence of low-grade mucinous neoplasms of the appendix and appendiceal diverticula: a possible role in the pathogenesis of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Mod. Pathol. 2000;13:495–501. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasaoglu E., Leblebici C., Okcu O., Boyaci C., Dursun N., Hande Yardimci A., Kucukyilmaz M. The relationship between diverticula and low-grade mucinous neoplasm of the appendix. Does the diverticulum play a role in the development of periappendicular mucin deposition or pseudomyxoma peritonei? Pol. J. Pathol. 2016;67(4):376–383. doi: 10.5114/pjp.2016.62829. PMID: 28547966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcacuzco Alberto A., Manrique Alejandro, Calvo Jorge, Loinaz Carmelo, Justo Iago, Caso Oscar, Cambra Felix, Fakih Naim, Sanabria Rebeca, Jimenez-Romero Luis C. Clinical implications of diverticular disease of the appendix. Experience over the past 10 years. Cir. Esp. 2016;94(1):44–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaser S.A., Willi N., Maurer C.A. Mandatory resection of strangulation marks in small bowel obstruction? World J. Surg. 2014;38:11–15. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Place R.J., Simmang C.L., Huber P.J., Jr. Appendiceal diverticulitis. South. Med. J. 2000;93(76):e79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin C.H., Chen T.C. Diverticulosis of the appendix with diverticulitis: case report. Chang Gung Med. J. 2000;23(711):e715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabiri H., Clarke L.E., Tzarnas C.D. Appendiceal diverticulitis. Am. Surg. 2006;72:221–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bianchi A., Heredia A., Hidalgo L.A., García-Cuyàs F., Soler M.T., del Bas M. Enfermedad diverticular del apéndice cecal. Cir. Esp. 2005;77:96–98. doi: 10.1016/s0009-739x(05)70815-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yantiss R.K., Shia J., Klimstra D.S., Hahn H.P., Odze R.D., Misdraji J. Prognostic significance of localized extraappendiceal mucin deposition in appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2009;33:248–255. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31817ec31e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pai R.K., Beck A.H., Norton J.A., Longacre T.A. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: clinicopathologic study of 116 cases with analysis of factors predicting recurrence. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2009;33:1425–1439. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181af6067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee K.H., Lee H.S., Park S.H., Bajpai V., Choi Y.S., Kang S.B. Appendiceal diverticulitis: diagnosis and differentiation from usual acute appendicitis using computed tomography. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2007;31:763–769. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3180340991|Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osada H., Ohno H., Saiga K., Watanabe W., Okada T., Honda N. Appendiceal diverticulitis: multidetector CT features. J. Radiol. 2012;30:242–248. doi: 10.1007/s11604-011-0039-2|Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaboury I.A. Diverticulitis of the vermiform appendix. ANZ J. Surg. 2007;77:803–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04240.x. | Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson J., Lobo D.N., Spiller R.C., Scholefield J.H. Diverticular abscess of the appendix: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2003;43:46832–46834. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6664-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]