Highlights

-

•

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) is a benign disease that can mimic cancer.

-

•

Management is complicated by uncharacteristic presentation and imaging findings.

-

•

Surgeons must ensure counselling includes the possibility of both XGC and carcinoma.

Keywords: Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis, Gallbladder cancer, Chronic cholecystitis, Surgery, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) is a rare and benign chronic inflammatory disease of the gallbladder that can mimic carcinoma on presentation, imaging, and gross pathology. The aim of this case report is to describe the considerations involved in navigating the diagnostic and surgical dilemma of managing XGC in a patient with findings equivocal to gallbladder cancer.

Presentation of case

A 64-year-old female patient presented with an incidental, suspicious gallbladder mass on imaging. Due to her asymptomatic presentation and high risk features for carcinoma on imaging, an oncologic, en-bloc resection of the mass involving the gallbladder, liver, wall of duodenum, and hepatic flexure of the colon was performed. On pathological examination, the gallbladder specimen showed marked lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate of XGC that extended into adjacent structures without dysplasia. The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative course.

Discussion

Considerations around management of XGC must include the potential consequences associated with overtreating a benign entity or undertreating a potentially curable malignancy. Imaging findings that may be more suggestive of XGC include continuous mucosal lines and the presence of pericholecystic infiltration or fat stranding. Pitfalls of biopsy include potential tumour spillage and false negative results, especially when both XGC and cancer are present. Intraoperatively, macroscopic examination of the mass can also be misleading.

Conclusion

Surgeons must ensure that preoperative counselling includes the possibility of both XGC and gallbladder carcinoma, especially when findings are uncharacteristic. XGC must be managed with careful consideration of all findings and multidisciplinary input from a team of surgeons, radiologists, and pathologists.

1. Introduction

When confronted with a suspicious gallbladder mass on imaging, a surgeon must consider the possibility of carcinoma versus benign infectious or inflammatory conditions [1]. One such entity includes xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) which is characterized by infiltration of macrophage-laden and foamy histiocytes with marked proliferative fibrosis. The clinical presentation and findings on investigation of XGC are variable and often overlap with gallbladder cancer, complicating diagnosis and management [1,2]. Furthermore, the true incidence of XGC is unknown, ranging widely from 0.7% to 13.2% of all inflammatory gallbladder pathology [3]. Geographical variations in incidence are also considerable, with most cases being reported from East and Southern Asian populations while there is very limited research in North America [4].

This report presents a unique case of XGC in a gallbladder mass that was incidentally discovered in an asymptomatic patient who presented to a tertiary care hospital with findings raising suspicion for carcinoma on presentation, imaging, and intraoperative examination. To raise awareness around the management of XGC, we describe the considerations involved in navigating the diagnostic and surgical dilemma between oncologic resection for gallbladder cancer and cholecystectomy alone for XGC.

This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [5].

2. Presentation of case

A 64-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the hepatobiliary surgery clinic after being referred by her family physician for cholelithiasis and a 2.3 cm gallbladder lesion on ultrasound obtained during investigation of elevated ferritin levels. She had a history of breast cancer which was treated with lumpectomy and radiotherapy 13 years ago. She was otherwise healthy with no signs or symptoms such as jaundice, weight loss, fever, gastrointestinal symptoms, or abdominal pain. The patient was not on any medications and she did not report any family history of gastrointestinal cancers. The patient was retired and lived at home with her husband.

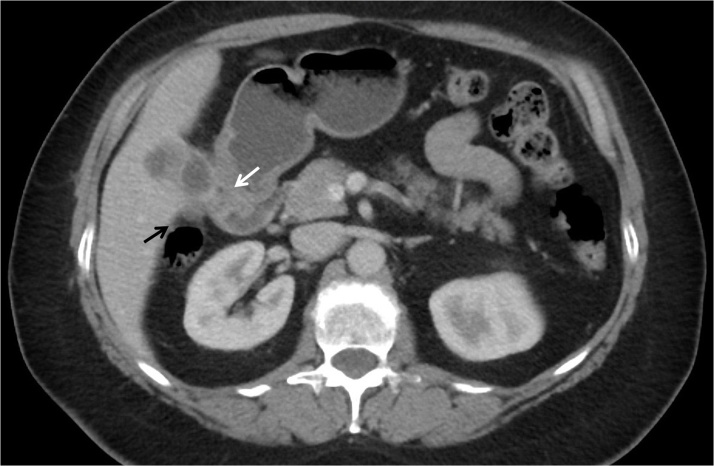

To better characterize the abnormal lesion found on ultrasound, CT and MRI scans were performed; both confirmed a gallbladder mass with an ill-defined interface with the liver, raising concern for an invasive neoplastic process (Fig. 1). Also noted were prominent upper abdominal lymph nodes and an enlarged periportal lymph node measuring 11 mm. These findings were thought to be high risk for gallbladder carcinoma, and an exploratory laparoscopy and potential surgical resection by the hepatobiliary surgeon were recommended. The patient was agreeable and was informed of the procedure including the possibility of multivisceral resection given the potential spread into adjacent organs.

Fig. 1.

Axial computed tomography scan showing gallbladder wall thickening with an indistinct border with the liver and abutment to the duodenum (white arrow) and colon (black arrow).

The patient had a normal (0–35 kU/L) CA19-9 level of 12 kU/L preoperatively. In the operating room, initial diagnostic laparoscopy demonstrated multiple 1–2 cm lesions in the left upper quadrant of the peritoneum. These were biopsied and sent for frozen section analysis which showed benign fibrosis with no evidence of malignancy. The duodenum and colon appeared adherent to the gallbladder but the extent of involvement was difficult to assess on laparoscopy. A laparotomy was performed and upon inspection, the gallbladder was hard with a mass-like lesion encompassing the fundus and mid-body which were adherent to the duodenum and colon. The lesion was also abutting the liver which was suspicious for invasion. Unable to completely rule out carcinoma, an en bloc cholecystectomy, partial hepatectomy, wedge excision of the colon, and partial duodenectomy were performed. The cystic margin was assessed as a frozen section which showed reactive atypia but no evidence of high-grade dysplasia or malignancy. A portal lymphadenectomy was undertaken as would be the standard for gallbladder malignancies. An esophago-gastroduodenoscopy and air leak test confirmed a satisfactory repair of the duodenum without significant narrowing, and the patient was taken to the postoperative care unit in stable condition.

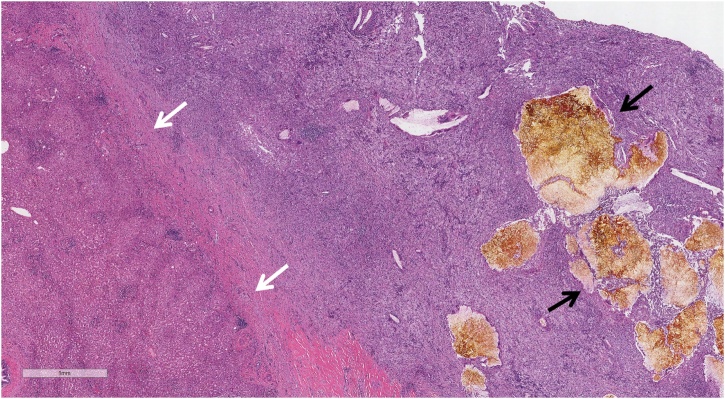

The postoperative course was uneventful. A CT scan with oral contrast on postoperative day 3 demonstrated an intact duodenal repair. The patient was discharged home the next day with a planned outpatient clinic follow-up three weeks later. On follow-up, physical examination was unremarkable except for a superficial surgical site cellulitis which was treated with oral antibiotics. The pathology report confirmed XGC with marked lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate, multifocal abscesses, and numerous multinucleated giant cells, including Touton-type giant cells (Fig. 2). No dysplasia or carcinoma was identified. The xanthogranulomatous inflammation extended into the liver, duodenum, and colon specimens. All resected lymph nodes were negative for carcinoma. Another visit was scheduled a week later to confirm resolution of the surgical site infection. The patient recovered fully and no further follow-up was required.

Fig. 2.

Lymphohistiocytic inflammation extending from the gallbladder bed into the liver. White arrows indicate transition into the liver (tissue on left). Black arrows indicate large yellow gallstone fragments within the inflammation. 20× magnification.

3. Discussion

Management options of a suspicious gallbladder mass include: (1) a preoperative biopsy, (2) cholecystectomy for chronic cholecystitis such as XGC, or (3) an oncologic procedure with en bloc resection of involved viscera. Fine needle aspiration and cytology can differentiate malignant masses from XGC [6], but there is a risk of seeding metastases which affects prognosis, and yielding false negative results in the case of carcinoma [7]. Intraoperative frozen sections can inform surgical strategy but risk perforation and tumor spillage, and the presence of cholecystitis on frozen section does not necessarily exclude concomitant carcinoma [8,9]. In fact, up to 20% of cases of XGC have been associated with carcinoma which may be easily overlooked when both are present [4]. The intraoperative decision-making remains to be the dilemma around overtreating a benign entity or undertreating a potentially curable malignancy. Cholecystectomy alone is the definitive treatment for XGC but is typically inadequate in the case of carcinoma [10]. An oncologic, en bloc resection of the gallbladder, liver, and any involved viscera and regional lymphadenectomy is commonly performed when suspecting malignancy. However, for patients with XGC mimicking cancer, this approach may be overly aggressive and can subject a patient to morbidities associated with multivisceral resection.

3.1. Clinical presentation

The incidence of XGC in males and females largely appears equal and occurs mostly in patients between 50–60 years old [3,4]. Clinical presentation of XGC is variable and often non-specific. A majority of patients present with chronic cholecystitis while others have acute cholecystitis or Mirizzi’s syndrome [8,11]. Almost all patients with XGC report abdominal pain, while nausea, vomiting, and anorexia occur in 18%–38% of patients [4]. About half of patients also have a positive Murphy’s sign on examination. As this case study demonstrates, however, XGC cannot be ruled out in asymptomatic patients, making it challenging to distinguish from early stage carcinoma. Given that jaundice only occurs in about 20% of patients with XGC [4], its absence in patients with concurrent abdominal pain may help differentiate XGC from gallbladder cancer with biliary obstruction. Jaundice in XGC may develop as a result of choledocholithiasis or excessive inflammation and transmural fibrosis that extends to the common bile duct.

3.2. Imaging

Accurate differentiation of XGC and gallbladder cancer based on radiological features is limited. Findings on ultrasound are variable, but more characteristic features of XGC include diffuse gallbladder wall thickening with hypoechoic nodules or bands [2]. Gallstones are often found concomitant with XGC. On CT, findings include diffuse, or less often, focal wall thickening, intramural hypoattenuating nodules, luminal surface enhancement in the presence of continuous mucosal lines, loss of interface between the gallbladder and liver, and other features of local inflammation [2,4]. These findings are also associated with gallbladder cancer, but features such as continuous, rather than disrupted, mucosal lines and the presence of pericholecystic infiltration or fat stranding are thought to be especially suggestive of XGC [2,4]. On MRI, areas of hyperintensity on T2-weighted images correspond to regions of abundant xanthogranulomas but can indicate necrosis and/or abscesses in the absence of enhancement [2]. Other features that can be seen on MRI include mucosal line continuity and enhancement, and blurring of interface between the liver and gallbladder.

3.3. Histopathology and gross pathology

XGC is thought to result from mucosal ulceration or rupture of occluded Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses, followed by intramural extravasation of inspissated bile and mucin [3,11]. This can be caused by elevated intraluminal pressure secondary to gallbladder or cystic duct obstruction. Extravasation of bile and mucin further attracts histiocytes that phagocytize insoluble cholesterol and bile salts, resulting in characteristic macrophage-laden and foamy histiocytes. In response, a chronic granulomatous inflammatory process leads to gallbladder wall thickening that can be mistaken for carcinoma [3,11]. Inflammation and rupture of the gallbladder serosal lining and the resulting fibrous reaction and scar formation lead to adhesions to neighbouring tissues including the liver, colon, and duodenum. Other complications from inflammation include perforation, abscesses, and cholecystoenteric or cholecystocutaneous fistulas.

On intraoperative gross pathology, the gallbladder can appear soft-to-firm with diffuse gallbladder wall thickening or destruction of the gallbladder borders. XGC can form intense fibrous adhesions and fistulous tracts with the adjacent organs, as does carcinoma [8]. Yellow nodules or streaks, which represent lipid-laden macrophages, may also be present. Regional lymphadenopathy can be present in 10%–26% of patients with XGC but occurs more frequently in gallbladder cancer in about 60% of patients [2,8]. Overall, macroscopic examination to diagnose XGC is misleading as there could be significant overlap with findings seen in gallbladder carcinoma. In fact, accuracy of a surgeon’s macroscopic differentiation between carcinoma and XGC has been reported to be only 50% [8].

4. Conclusion

Despite being a benign entity, the diagnostic dilemma surrounding XGC can be a significant cause for concern for patients and clinicians. Clinical presentation and imaging findings are often insufficient to make a clear diagnosis and dictate appropriate surgical management. Surgeons must ensure that gallbladder cancer is not missed but should prepare for the morbidity and complications that can result from aggressive treatment, with careful consideration of all findings and multidisciplinary input from a team of surgeons, radiologists, and pathologists.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

This study is exempt from ethical approval in the University of Ottawa.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Alex Lee – Study conceptualization, Data collection, Data review, Drafting manuscript.

Catherine L. Forse – Data review, Revision of manuscript.

Cindy Walsh – Data review, Revision of manuscript.

Kimberly Bertens – Study conceptualization, Data review, Revision of manuscript.

Fady Balaa – Study conceptualization, Data review, Revision of manuscript, Finalization of manuscript.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Dr. Fady Balaa is the Guarantor for the work and/or the conduct of the study, has access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- 1.John S., Moyana T., Shabana W., Walsh C., McInnes M.D.F. Gallbladder cancer: imaging appearance and pitfalls in diagnosis. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0846537120923273. May; 846537120923273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh V.P., Rajesh S., Bihari C., Desai S.N., Pargewar S.S., Arora A. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: what every radiologist should know. World J. Radiol. 2016;8(2):183–191. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v8.i2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolukbasi H., Kara Y. An important gallbladder pathology mimicking gallbladder carcinoma: xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: a single tertiary center experience. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutaneous Tech. 2020;30(3):285–289. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hale M.D., Roberts K.J., Hodson J., Scott N., Sheridan M., Toogood G.J. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: a European and global perspective. HPB. 2014;16(5):448–458. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A.J., Orgill D.P. The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hijioka S., Mekky M.A., Bhatia V., Sawaki A., Mizuno N., Hara K. Can EUS-guided FNA distinguish between gallbladder cancer and xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis? Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010;72(3):622–627. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misra S., Chaturvedi A., Misra N.C., Sharma I.D. Carcinoma of the gallbladder. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4(3):167–176. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng Y.L., Cheng N.S., Zhang S.J., Ma W.J., Shrestha A., Li F.Y. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis mimicking gallbladder carcinoma: an analysis of 42 cases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015;21(44):12653–12659. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i44.12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houston J.P., Collins M.C., Cameron I., Reed M.W.R., Parsons M.A., Roberts K.M. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Br. J. Surg. 1994;81(7):1030–1032. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J.M., Kim B.W., Kim B.W., Wang H.J., Kim M.W. Clinical implication of bile spillage in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallbladder cancer. Am. Surg. 2011;77(6):697–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yucel O., Uzun M.A., Tilki M., Alkan S., Kilicoglu Z.G., Goret C.C. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: analysis of 108 patients. Indian J. Surg. 2017;79(6):510–514. doi: 10.1007/s12262-016-1511-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]