Abstract

Dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) of a biomolecule tagged with a polarizing agent has the potential to not only increase NMR sensitivity but also to provide specificity towards the tagging site. Although the general concept has been often discussed, the observation of true site-specific DNP and its dependence on the electron–nuclear distance has been elusive. Here, we demonstrate site-specific DNP in a uniformly isotope-labeled ubiquitin. By recombinant expression of three different ubiquitin point mutants (F4C, A28C, and G75C) post-translationally modified with a Gd3+-chelator tag, localized metal-ion DNP of 13C and 15N is investigated. Effects counteracting the site-specificity of DNP such as nuclear spin-lattice relaxation and proton-driven spin diffusion have been attenuated by perdeuteration of the protein. Particularly for 15N, large DNP enhancement factors on the order of 100 and above as well as localized effects within side-chain resonances differently distributed over the protein are observed. By analyzing the experimental DNP built-up dynamics combined with structural modeling of Gd3+-tags in ubiquitin supported by paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) in solution, we provide, for the first time, quantitative information on the distance dependence of the initial DNP transfer. We show that the direct 15N DNP transfer rate indeed linearly depends on the square of the hyperfine interaction between the electron and the nucleus following Fermi’s golden rule, however, below a certain distance cutoff paramagnetic signal bleaching may dramatically skew the correlation.

Direct DNP transfer rates can be used to measure electron-nuclear distances and to provide site-specificity in NMR.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) is a powerful method capable of increasing the generally low NMR sensitivity by up to several orders of magnitude.1, 2 This sensitivity enhancement is achieved by transferring the relatively high polarization of endogenously present or exogenously added electron spins to surrounding nuclear spins at high magnetic field and under microwave (μw) irradiation. The theoretical maximum NMR signal enhancement corresponds to the ratio of the Larmor frequencies of the electron and the polarized nucleus that is 658 for 1H, or 2630 and 6480 for 13C and 15N, respectively. Nevertheless, concurrent loss of nuclear hyperpolarization by spin-lattice relaxation leads to a reduced achievable enhancement in experiment.3

Under solid-state conditions encountered in a vitrified solution, the solid effect (SE) or cross effect (CE) typically contribute to the net signal enhancement.4, 5 Of these DNP mechanisms, the SE potentially allows for a rather straightforward geometrical analysis of the involved electron–nuclear (e-n) spin pair,4, 6, 7 whereas in the (electron–electron–nuclear) three-spin system required for CE the DNP efficiency intricately depends on the individual spins’ anisotropies and orientations.4, 8 The complexity is even exacerbated in rotating samples during magic-angle spinning (MAS).9, 10

Paramagnetic high-spin metal ions Mn2+ and Gd3+ have been utilized as DNP polarizing agents,11–13 particularly for direct DNP of nuclei with a small gyromagnetic ratio γ (henceforth called low-γ nuclei).14–17 In comparison to the bulky trityl or BDPA radicals,7, 18 these metal ions can be bound by relatively small chelator tags for paramagnetic labeling of proteins by site-directed spin labeling.19, 20 Furthermore, through their electronic high-spin state, Gd3+ features large EPR transition moments which result in competitive DNP efficiency,7, 13 particularly when deleterious effects such as broadening of the EPR line due to zero-field splitting are minimized by choice of a highly symmetric ligand.11, 14, 21

Generally, the overall DNP process can be separated into three individual steps: (i) the direct e–n transfer of polarization described by one of the abovementioned mechanisms; (ii) the (spontaneous) propagation of built-up hyperpolarization by homonuclear spin diffusion or heteronuclear cross relaxation; (iii) the utilization of hyperpolarization received on the analyte by a read-out pulse sequence or further evolution during a typical NMR experiment.1 Each of these three steps are influenced by spin relaxation to a certain degree. In particular step (i) may underlie strong paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) which limits the maximum amount of polarization accumulated on the nuclear spins.22–24. In contrast, step (ii) may even benefit from transverse PRE as it may facilitate transport of polarization through the spin-diffusion barrier,25 whereas step (iii) most certainly suffers if significant paramagnetic line broadening is present during detection or transverse mixing.24, 26 In light of this complex interplay of mechanisms, spectroscopists can make optimal use of the available electron spin polarization by a combination of experimental design choices within each of these steps and thus control the overall transfer pathway.

Several attempts have recently been made to utilize the locality of the e–n transfer process in order to create specificity or additional spatial information. In localized or targeted DNP, a polarizing agent tag is specifically attached to an analyte with the goal of selectively enhancing the NMR signal of the molecular species or site of interest while other non-targeted sample constituents remain at or near thermal polarization. Successful demonstrations have been presented by covalently attaching nitroxide or metal-ion polarizing agents to proteins or lipids,14, 27–30 by non-covalently targeting proteins with high-affinity ligands functionalized with polarizing agents,31, 32 or by incorporating metal-ion polarizing agents in endogenous binding sites.33, 34 However, efficient spin diffusion within the 1H network may quickly cause a bleeding of hyperpolarization from the labeled analyte to the surrounding bulk and thus a loss in spatial information. One approach to retain 1H hyperpolarization on the biomolecular analyte is to perform targeted or localized DNP within a fully deuterated matrix.31, 32 Thus, a direct transfer pathway exists from the bound polarizing agent tag to the proton-bearing analyte while the absence of 1H in the matrix prevents the leakage or draining of polarization to the bulk. However, perdeuteration of the matrix in excess of ~90 % might not be possible in all cases, particularly when cellular environments are concerned.

In this regard, direct DNP of nuclei with a gyromagnetic ratio smaller than 1H has shown significant potential recently in the context of biomolecular DNP.35 The absence or sparseness of relevant low-γ nuclei in the matrix naturally leads to spatial conservation of polarization on isotope-enriched targeted/tagged biomolecules. At the same time, spin-diffusion is naturally retarded in comparison to 1H due to the significantly smaller coupling between magnetic moments in combination with MAS, while the density of these nuclides can additionally be controlled for (e.g., by uniform or specific/selective labeling). This can further limit the spatial propagation of enhanced nuclear polarization and may lead to true site-selective DNP effects where nuclei only within a certain radius around the polarizing-agent label are affected. Even though it has been demonstrated that DNP can act over distances of 8 Å or longer,36 and that transfer from a molecular polarizing agent to a sparsely 19F labeled protein is possible without relay,37 the quantitative distance dependence of the polarization dynamics has never been elucidated experimentally.

Direct and potentially localized DNP can be achieved within uniformly [13C,15N]-labeled ubiquitin using Gd3+-tags via site-directed spin labeling (SDSL).14 To extend this initial proof-of-concept, we introduce cysteine residues as single point mutations at different positions to covalently attach the spin label into the protein ubiquitin that does not contain native cysteine residues. We compare direct and localized DNP for three different ubiquitin mutants, F4C, A28C, and G75C, which have each been labeled with a Gd-DOTA-M tag. This cyclic chelate label is much more stable than that based on 4MMDPA,38 not only due to the much smaller complex dissociation constant, but also due to the non-hydrolysable sulfide bond formed by the thiol-Michael addition as compared to the disulfide bond.39 The three different labeling positions have allowed us to investigate the influence of the distance between the Gd3+ ion and the protein core. As is shown in Figure 1, F4C is located within the central N-terminal β-sheet and leads to relatively short distances between metal ion and protein core, allowing for many strong e–n contacts. A28C sits on the outwards-facing side of the α-helix, still allowing for sufficiently close contacts. G75C, on the other hand, is located within the C-terminal region and as a result the label can adopt conformations where the metal ion is much more removed from the core and only the next neighbors along the peptide chain are in direct dipolar contact. This variety of different labeling positions has allowed us to investigate the potential of site-specificity of DNP in (indirect) 1H DNP as well as (direct) 13C and 15N DNP in detail.

Figure 1.

Graphical depiction of Gd-labeling positions F4 (green), A28 (brown), and G75 (purple) as well as the positions of the amino acid side chains with 15N signals resolved from the amide signal: Lys (blue), Arg (red), and His (yellow). The spheres mark the position of the Cα of the respective labeling site.

Theory

The SE DNP transition moment

Since the underlying theory has already been treated elsewhere,4, 6, 7 we will directly introduce the SE transition moment, which is the basis for the SE transition probability under Fermi’s golden rule (see below). As the SE relies on dipolar hyperfine interaction (HFI), the direct DNP transfer rate is strongly dependent on the interconnecting vector between the electron and nuclear spin. In detail, the pseudo-secular component of the HFI is the driving interaction with the effective coupling strength depending on the e–n distance r and the angle θ, defining the angle between the e–n connecting vector and the direction of the external magnetic field of magnitude B0. Under irradiation with a μw field of frequency ωμw matching the SE condition (i.e., at ωμw =ω0S ±ω0I; ω0S and ω0I are the electron and nuclear Zeeman frequencies, respectively) this results in the SE transition moment:

| (1.2) |

where μ0 is the vacuum permeability, g is the electron g factor, μB is the Bohr magneton, and h is the reduced Planck constant. We see from Equation (1.2) that the effective DNP transition rate does not depend on the gyromagnetic ratio of the nucleus to be polarized, but only on its position relative to the electron spin. Even though a nucleus with a larger gyromagnetic ratio is subject to a larger HFI (for the same e–n connecting vector) the penalty imposed by the larger nuclear Larmor frequency in the mixing coefficient is compensating this factor. For a more detailed explanation of this situation and a full derivation of Equation (1.2), see SI.

DNP transfer dynamics

Next, we describe the polarization dynamics within the e–n pair. In the case of SE DNP under MAS the build-up of coherences between eigenstates can be neglected (i.e., the decoherence rate is much larger than any μw-driven transition rate). Therefore we can express the specific case of direct μw excitation of the ZQ SE DNP transition, namely , with a simple differential equation:

| (1.3) |

Here, Pe and Pn are the electron and nuclear polarizations, respectively, are the respective values in thermal equilibrium (i.e., the Boltzmann polarizations); R1e and R1n are the electron and nuclear longitudinal relaxation rate constants and kDNP is the DNP transfer rate constant. In the limit where electron relaxation is sufficiently fast in order to always maintain , we get:

| (1.4) |

With . From this rate equation we can derive two measures: (i) the steady-state enhancement factor ε∞, as well as (ii) the initial DNP rate .

ε∞ is reached in a dynamic equilibrium at sufficiently long (ideally infinite) polarization time. Therefore, it may be expressed as a function of an equilibrium constant KDNP =kDNP/R1n :7

| (1.5) |

Since R1n is depending on the e–n distance in a non-trivial manner, KDNP is expected to also depend on r. In order to analyze this dependence, we first derive kDNP which is proportional to the respective SE transition probability following Fermi’s golden rule and thus scales as the square of the transition moment given in Eq. (1.2). Therefore, kDNP is expected to follow an r−6 law for a direct e–n transfer:

| (1.6) |

Next, we assume the overall nuclear relaxation rate R1n is consisting of additive contributions of the dipolar paramagnetic relaxation rate and a “diamagnetic” relaxation rate where the latter does not depend on the presence of the electron spin:

| (1.7) |

The dipolar paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) rate can in the most general case be described by:40–42

| (1.8) |

where gn and μn are the nuclear g factor and magneton, respectively.

As both PRE and DNP rates depend on the squared HFI coupling, they follow the same theoretical distance law. Therefore, as long as dipolar PRE is the only nuclear relaxation mechanism, the DNP equilibrium constant (and thus the steady-state enhancement) is in theory independent of the interspin distance within the e–n pair:

| (1.9) |

with . This theoretical independence of the steady-state enhancement has very recently already been discussed and experimentally confirmed in the context of statistical doping of crystalline materials.43

In contrast, the initial DNP rate is directly depending on the DNP transition moment and may be directly obtained by analyzing the build-up of nuclear polarization immediately after initiating the DNP transfer:

| (1.10) |

This guides us to the conclusion that the steady-state enhancement factor is a fundamentally unsuited measure to probe the e–n distance, but rather the initial DNP rate should be directly proportional to r−6.

In the strictest sense, the system has to be initialized in thermal equilibrium in order for Eq. (1.10) to be valid. However, it is easily shown (see SI) that as long as a significant DNP enhancement is observed, the contribution of may be neglected and can be reliably measured through the build-up of DNP after a saturation sequence.

Results and Discussion

Effect of protein deuteration

In Figure 2, we show the 13C MAS NMR spectra of two ubiquitin mutants A28C and G75C which have each been labeled with a Gd-DOTA-M tag with and without μw irradiation at the direct Gd3+–13C SE matching condition (note that due to instrumental reasons, the negative DNP condition had to be chosen which leads to an inversion of the DNP-enhanced NMR spectra). By careful substitution of all exchangeable protons and preparation in a fully deuterated DNP matrix we have effectively increased the direct 13C DNP enhancement for the [CN]-Gd-A28C-Ub sample as compared to our earlier work,14 and have now achieved a DNP enhancement factor of ε = −3 through direct Gd3+–13C SE. In stark contrast, no sensitivity enhancement is observed for [CN]Gd-G75C-Ub; in fact, the polarization is effectively destroyed with ε ≈ 0 (i.e., the polarization transfer by DNP at the negative SE condition is only able to counteract the thermal polarization).

Figure 2.

Direct 13C DNP-enhancement of MAS NMR spectra for Gd-A28C-Ub (top) and Gd-G75C-Ub (bottom). The protein was overexpressed from protonated medium but all exchangeable protons have been deuterium exchanged prior to preparation in fully deuterated DNP buffer. DNP-enhanced spectra are shown in blue (lower trace, μw on), spectra without μw irradiation are shown in red (upper trace, μw off). Spectra were recorded at 10 s polarization delay and normalized for accumulated transients for each mutant, the spectra of the two mutants were scaled for similar off-spectrum intensity. The resonance from the silicone plug is marked by an asterisk.

This difference suggests two hypothetical scenarios (or a combination of both): (i) DNP from the chelate tag to the protein is less efficient for G75C-Ub; or (ii) once transferred from Gd3+ to the cysteine and neighboring residues, the spreading of enhanced nuclear polarization via spin-diffusion is less efficient. On the one hand, the compact protein folding around the A28 position (see Figure 1) could lead to the polarizing agent tag occupying a more defined conformational space resulting in direct contacts between chelate tag and protein surface while for G75—the penultimate residue in the 76 amino acid sequence and thus part of the rather flexible C-terminus—the propensity for such contacts is significantly diminished. On the other hand, ubiquitin has a large ratio of methyl-bearing residues (i.e., Ala, Val, Leu, Ile, Thr, and Met) such that 30 out of the 76 amino acids introduce a total of 57 CH3 groups. This large methyl concentration leads to very efficient heteronuclear dipolar relaxation of 1H and 13C induced by the thermally-activated reorientation dynamics even at 110 K.44 This causes a short 13C spin-lattice relaxation constant and efficient draining of enhanced relaxation before it can spread over larger distances by spin diffusion.40, 45 Both effects in combination could lead to the observed behavior.

In order to investigate this effect, we have systematically varied the proton concentration within the protein by recombinant expression in partially or fully deuterated growth media. This resulted in a series of protein samples grown from M9 medium with 30/70, 60/40, and 90/10 % 2H2O/1H2O content (i.e., [.3DCN], [.6DCN], and [.9DCN] as well as a fully deuterated sample grown from OD2 CDN medium ([DCN]), in addition to the above mentioned control sample grown from non-deuterated M9 medium ([CN]). Note that all samples have been freeze-dried and dissolved in D2O three times and all DNP samples have been prepared in fully deuterated D8-12C3-glycerol/D2O mixture; thus we assume near-quantitative deuteration of all exchangeable hydrogens for all samples. After expression and purification, we have determined the deuteron content by mass spectroscopy; see Table 1 for a full comparison of all samples.

Table 1.

Overview of ubiquitin samples recombinantly overexpressed from different isotope-labeled media. Deuteration levels have been determined by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry after exchange of labile hydrogens by triple lyophilization and resuspension from H2O or D2O.

| Sample | Expression medium | Deuteration level (%) by MALDI-TOF MS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| from H2O | from D2O | ||

| [CN]-G75C-Ub | M9 | 0 % | 10 % |

| [.3DCN]-G75C-Ub | M9 30 % D2O | 21 % | 31 % |

| [.6DCN]-G75C-Ub | M9 60 % D2O | 45 % | 55 % |

| [.9DCN]-G75C-Ub | M9 90 % D2O | 58 % | 67 % |

| [DCN]-G75C-Ub | OD2 CDN medium | 74 % | 87 % |

| [DCN]-F4C-Ub | OD2 CDN medium | 74 % | 86 % |

| [DCN]-A28-Ub | OD2 CDN medium | 73 % | 89 % |

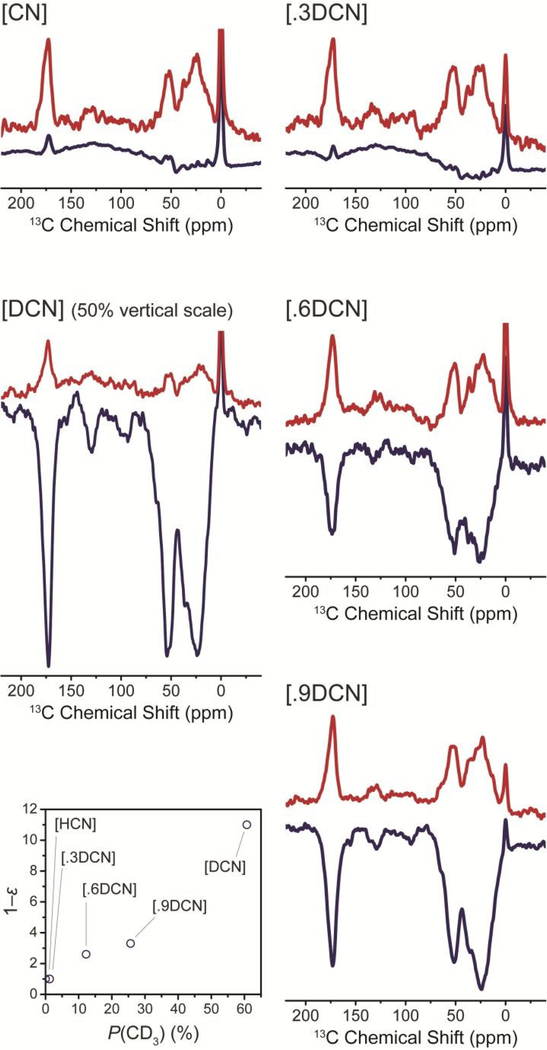

In Figure 3 it can be seen that for G75C-Ub, a significant DNP enhancement is only achieved for samples with a nominal deuteration ratio of at least 60 % ([.6DCN]) where we find a complete inversion of the NMR spectrum by DNP under μw irradiation. For [.9DCN] we recover a DNP enhancement of –2 to –3. Very interestingly, this factor is further increased approximately three-fold by complete protein deuteration ([DCN]). In Figure S2 we also show the absolute NMR signal intensity increase normalized to the sample amount which shows a more than four-fold increase from [.9DCN] to [DCN]. We have observed similar enhancement factors of −6 to −7 for the other fully deuterated mutants (i.e., [DCN]-A28C-Ub and [DCN]-G75C-Ub), however, the relative improvement from the protonated samples seems less pronounced.

Figure 3.

Comparison of direct 13C DNP enhancement for different deuteration levels. Left: Fully protonated [CN] and fully deuterated [DCN] Gd-G75C-Ub sample. Right: intermediate deuteration levels. Spectra without μw irradiation are shown in red (upper trace, μw off). Spectra were recorded at 10 s polarization delay and normalized for accumulated transients for each mutant, the spectra of the two mutants were scaled for similar off-spectrum intensity (the spectra of [DCN] were scaled by a factor 0.5 for better visibility). The inset in the lower left corner shows the dependence of the DNP enhancement factor on the statistical abundance of fully deuterated methyl groups.

Influence of dipolar relaxation and spin diffusion

We have also found that the 13C polarization build-up time constant strongly increases with higher deuteration level (see Figure S2). For [.6DCN] we have measured a value of ~4 s which monotonically increased to ~10 s at highest deuteration ([DCN]). This is in agreement with our hypothesis that 1H–13C dipolar relaxation is limiting the accumulation of 13C polarization in the case of a highly-protonated protein whereas DNP transfer is allowed more time to build up polarization on the 13C network if the 1H concentration is diminished. A rather simple statistical approach (see Figure 3, bottom left) shows that the DNP parameters correlate well with the number of fully-deuterated CD3 groups in relation to methyl groups containing at least one proton (i.e., CH3, CH2D, and CHD2). We are supporting this explanation with experiments on all possible 13C-methionine methyl-isotopomers (i.e., –CH3, –CH2D, –CHD2, and –CD3). Employing specific cross-relaxation enhancement by active motions under DNP (SCREAM-DNP) as a measure for dipolar relaxation efficacy,35, 46, 47 we have found similarly strong 1H–13C heteronuclear Overhauser effect for all isotopomers except –CD3 (see Figure S3). In the latter case this cross-relaxation effect is completely suppressed due to the absence of any time-dependent C–H dipolar coupling.

Interestingly, for the highly protonated samples (Gd-[CN]-G75-Ub and Gd-[.3DCN]-G75-Ub) a peculiar lineshape with a strong background signal is visible (Fig. 3, top). The carbonyl spectral region, in particular, shows that the signal is composed of two overlapping parts: a small, positive signal which is significantly reduced in intensity (i.e., with a DNP enhancement factor 0 < ε < 1) and a drastically broadened contribution centered around the same chemical shift but with an emissive phase. We hypothesize that this signal is caused by residues within short distance around the Gd3+-tag which are severely broadened by the paramagnetic metal ion but nevertheless experience rather strong DNP enhancement.14 Due to the efficient 13C relaxation by methyl groups this large polarization quickly decays before it can be effectively transferred to the protein bulk which consequently only experiences a small reduction of polarization without full inversion by DNP. We have observed further indications of this polarization gradient’s propagation when carefully analyzing the spectral shape of the [.9DCN] protein for which a fully inverted NMR spectrum is obtained under DNP. In Figure 4 we can follow the propagation of enhanced polarization by adjusting the polarization time, i.e., the time during which polarization is transferred via DNP and can spread from the directly polarized residue(s) over the 13C network. For very short delays (e.g., 1 s) we have observed a significant effective broadening which is very well visible in the aliphatic signal region. For these short time periods, the residues close to Gd3+ are expected to contribute to a larger (relative) degree to the NMR signal whereas after longer periods (e.g., 8 s) sufficient polarization has reached more distant residues which do not experience the same degree of paramagnetic broadening.

Figure 4.

Comparison of direct 13C DNP-enhanced MAS NMR spectra of [.9DCN]-Gd-G75C-Ub at different polarization delays. Spectra were normalized to equal maximum negative intensity.

Direct 13C vs. 15N DNP

For 13C, a maximum enhancement factor on the order of 10 has been observed. We expect that this factor can be further increased with either larger μw power or at lower sample temperature. However, this limited enhancement does not provide sufficient fidelity for analysis with regards to selective 13C DNP of labeled proteins with the current commercial DNP instrumentation. Interestingly, we have found much larger enhancement factors for direct DNP of 15N. For example, for [.9DCN]-Gd-G75C-Ub, we have measured a ~100-fold DNP enhancement of the amide resonance (see Figure 5). For the same but fully deuterated [DCN] protein an even larger DNP efficiency may have been reached—as estimated by a signal intensity comparison with the [.9CDN] sample (see Figure S2), however, it was impossible to determine the enhancement factor because the NMR sensitivity without μw irradiation was too small for the limited sample amount. This larger ε of 15N in comparison with 13C is in part explained by the 2.5-fold smaller gyromagnetic ratio; however, the greatly reduced spin-lattice relaxation losses of 15N due to the small gyromagnetic ratio most likely allow for the accumulation of a larger amount of hyperpolarization over a longer polarization time.

Figure 5.

Direct 15N DNP-enhancement of MAS NMR spectra for [.9DCN]-Gd-G75C-Ub. DNP-enhanced spectra are shown in blue (lower trace, μw on), spectra without μw irradiation are shown in red (upper trace, μw off); for better visibility of the off-spectrum a 10-fold vertical magnification is shown in a light trace. Spectra were recorded at 500 s polarization delay and normalized for accumulated transients.

We have measured DNP build-up time constants of the dominating amide resonance which are on the order of ~200 s for [CN] and slightly decrease with increasing deuteration to ~160 s for [DCN] as is shown in Figure S2. The inverse effect of 1H concentration in comparison to 13C is indicative that proton-driven spin diffusion is not a major contributor to polarization propagation between the electron and the observed 15N spins. Rather, we conclude that, in fact, a significant fraction of the enhanced polarization is transferred from the Gd3+ to the 15N giving rise to the NMR signal without any relay.

Experimental observation of specific direct 15N DNP dynamics

In order to test the above hypothesis, we have further investigated the polarization dynamics of the amino acid residues carrying 15N in their side chains. In addition to a dominant signal which corresponds to protein backbone and side chain amide groups, we have also found DNP-enhanced signals of Arg as well as Lys, and a less intense 15N signal corresponding to the side chain of the single His residue in ubiquitin. There are four Arg and seven Lys residues in ubiquitin, however, no discrimination could be made between the overlapping side chain resonances of each amino acid type, preventing us from identifying individual Gd3+–15N pairs (with the exception of the single His). Nevertheless, we have been able to directly compare the collective behavior of all amino acid residues of each type of side chain signal for the three different Gd-labeling positions. We have observed significant spectral differences between the three labeling positions at short polarization times (see Figure 6, 10 s) whereas longer polarization times have resulted in fairly similar signal intensities for all three labeling positions (512 s). Interestingly, for F4C-Ub, a strong but broadened signal of Lys and a weak signal of His are already present at 10 s while no signal of Arg can be observed. In contrast, for G75C-Ub, the situation is practically opposite; the Arg signal is prominent, but the signal of Lys is difficult to detect and the signal of His is absent. For A28C-Ub no such clear distinction is found and both Arg and Lys are only weakly visible after 10 s.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the direct 15N DNP-enhanced spectra of all three Gd-labeling positions for 10 s polarization delay (top) and 512 s polarization delay. Resonance positions for the analyzed side chain signals are highlighted by vertical lines. 512 transients were accumulated at 10 s, 32 transients at 512 s for each spectrum.

When inspecting the spatial distribution of these three amino acid types in ubiquitin with respect to the individual tagging positions as is shown in Figure 1, we have observed the following pattern: Arg residues cluster near G75 at the C-terminus, whereas Lys residues are located mostly on the opposite side close to F4, which is also fairly close to the single His residue; A28 is situated in the center of the α-helix in the protein’s core and is generally in intermediate distance to either Arg or Lys side chains. This indicates that the DNP signal intensity at short polarization times inversely correlates with the apparent proximity between Gd3+ and the effective center of mass of the amino acid side chains.

Distance calibration of site-specific DNP rates by computational structural modeling

In order to quantify that correlation, we have analyzed the early signal build-up of the bulk amide as well as the Arg, Lys, and His resonances after saturation pulses and fitted these data with a linear function (Figure S4). According to equation (1.10) we have interpreted the slope of these build-up curves as the mean DNP transfer rate of these nuclei (see Table 2). For a detailed description of our analysis, see the Supplementary Information, where also a full set of spectra for all measured polarization delays as well as the generated build-up curves are shown in Figure S4.

Table 2.

Experimental mean initial DNP rates in comparison with average effective distances calculated from Eq. (1.11) and DNP-effective inverse distances 〈r−6〉 between Gd3+ and the side chain 15N system for Arg, His, and Lys in Gd-F4C-Ub, Gd-A28C-Ub and Gd-G75C-Ub. Distances were calculated from structural models as explained in more detail in the text and given for all Gd3+–15N pairs (no cutoff) as well as only including pairs outside a 12 Å cutoff distance.

| no cutoff | 12 Å cutoff | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (s−1) | (Å) | 109 〈r−6〉 (Å−6) | (Å) | 109 〈r−6〉 (Å−6) | ||

| Arg | F4C | 13 | 26.85 | 2.7 | 26.85 | 2.7 |

| A28C | 86 | 18.15 | 28.0 | 19.69 | 17.2 | |

| G75C | 236 | 11.01 | 561.4 | 16.50 | 49.5 | |

| His | F4C | 179 | 12.84 | 223.2 | 16.55 | 48.6 |

| A28C | — | 26.32 | 3.0 | 26.32 | 3.0 | |

| G75C | — | 19.23 | 19.8 | 20.52 | 13.4 | |

| Lys | F4C | 175 | 10.13 | 925.4 | 16.86 | 43.5 |

| A28C | 130 | 12.95 | 212.0 | 18.07 | 28.7 | |

| G75C | 44 | 19.23 | 19.8 | 21.93 | 9.0 | |

For comparison of the DNP build-up rates with the effective Gd3+–15N distances for Arg, Lys, and His at each of the three tagging sites we have recorded paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) through heteronuclear single quantum correlation (HSQC) spectra in solution. Our initial attempt to estimate Gd3+–15N side chain distances from PRE data has been unsuccessful because of the difficulty to detect the 15N resonances of amino acid side chains in HSQC spectra owing to the side chains’ high mobility in combination with solvent hydrogen exchange of the nitrogen functional groups. Therefore, we have employed a computational structure prediction approach. We have generated a library of conformations for the Gd-DOTA-M tag linked to the side chain of Cys by sampling rotamers of known small molecule fragments that matched regions in Gd-DOTA-M-Cys from the Crystallography Open Database (COD)48, 49 (see Methods in ESI). The resulting set of conformations contained all of the expected rotamers for the linker dihedral angles with balanced probabilities (Figure S5) which indicated that the conformer library was fairly complete. Based on this library approach we have modeled the conformational ensemble of Gd-DOTA-M-Cys at each of the experimentally studied tagging sites in ubiquitin using the Rosetta program50. After careful minimization of protein and spin label, any conformers that produced clashes with the protein structure have been removed to yield a refined ensemble of low-energy conformations of Gd-DOTA-M-Cys. This approach resembles the commonly used “tether-in-a-cone” search strategy for simulating distributions of nitroxide-based spin labels (e.g., MTSSL-wizard51), but, in addition, weights conformers by the frequency of matching rotamer fragments in the COD and uses a physically realistic energy function to model the interaction between spin label and protein environment.52 To account for protein conformational flexibility, we have applied this workflow to an ensemble of ubiquitin structures, which we have created by relaxing the bundle of NMR-determined ubiquitin structures (PDB: 1D3Z)53 through dihedral angle dynamics in the Rosetta FastRelax refinement protocol54. In case of spin-label site G75, we have included an additional 30 models from a previously created MD trajectory of ubiquitin and used them as input for FastRelax refinement to more thoroughly sample the conformation at G75, which is located in the C-terminal tail in ubiquitin.

We have observed varying conformational behaviors of Gd-DOTA-M-Cys at the three experimentally studied spin label sites in ubiquitin, see Figure 7. In the case of F4C, the conformational space of the Gd-DOTA-M-Cys spin label is more restricted compared to the other two tagging sites which in turn limits the localization density of the Gd3+ ion to a small curved plane above the central β-sheet of ubiquitin. A28C is on the solvent-exposed side of the α-helix in ubiquitin, permitting the Gd-DOTA-M tag to sample a larger number of conformations, resulting in an umbrella-shaped positional density for the Gd3+ ion which virtually covers the entire α-helix. The number of accessible conformations of Gd-DOTA-M is even higher at G75C due to the high solvent-accessibility of that position and the increased conformational flexibility of the C-terminus of ubiquitin. Thus, the space occupied by Gd3+ is much larger than for F4C and A28C. While in some conformations the Gd-DOTA-M tag points away from the protein into the solvent, in some other conformations the C-terminus folds back onto the protein permitting the Gd-DOTA-M tag to approach the surface of ubiquitin at short distance. This situation is different from sites F4C and A28C, where the linker of Gd-DOTA-M adopts a more extended structure and is firmly anchored to the rigid protein backbone.

Figure 7.

Structural modeling of the conformations of Gd-DOTA-M-Cys spin labels at three sites in ubiquitin. For each tagging position, F4C, A28C, and G75C, a representative conformer of Gd-DOTA-M-Cys, which corresponded to the centroid of the largest spin label cluster identified by dihedral angle clustering, is shown (sticks). The density of Gd3+ resulting from all valid spin label conformations is indicated in gray, and the protein molecule is depicted as ribbon.

For means of validating the modeled spin label structural ensembles, we have collected 1HN PREs on Gd-DOTA-M-tagged ubiquitin in solution and compared them to PREs back-calculated from the structural models (see Methods in ESI). We have observed a good correlation between experimental and model-predicted PRE rates with a PRE Q-factor of 0.23 for F4C, 0.30 for A28C, and 0.62 for G75C (Figure S6) which lends confidence to our structural models. In the case of A28C-Ub, only six residues (G10, T12, A46, G47, Q49, T66) showed PREs that were significantly larger than what can be expected based on the Gd-Ub structural models. Since all of the six residues cluster on the spin label-opposing solvent-exposed side of ubiquitin, it is possible that they experience an additional inter-molecular PRE which arises from temporary contacts between this highly positively charged surface patch of ubiquitin and the Gd-DOTA-tag of another ubiquitin molecule. For G75C, the experimental PREs are overall very small which is consistent with the model-predicted high conformational flexibility of Gd-DOTA-M tags at G75.

Next, we have correlated the calculated distance distributions with our experimentally observed DNP build-up rates. In Table 2 we have compiled the calculated average effective distance

| (1.11) |

between Gd3+ and 15N of each amino acid type. Here, r represents the distance between the Gd3+ distribution and the center of mass of the side-chain nitrogen atoms of each amino acid residue. Because the nitrogen atoms within one residue’s side chain are much closer to each other (i.e., 2.2–2.4 Å) than to nitrogens in other amino acids or to the electron spin, we expect that each side chain may act more like a common entity due to nuclear spin exchange so that this approach is justified. We estimate that the error—as related to the effective distance if every nitrogen would be counted individually—to be smaller than 0.3 Å which lies well within the error ranges in any case.

As already laid out, this analysis assumes that the electron polarization is transferred in parallel to each 15N with an individual DNP rate constant and we then observe the total contribution of these nuclei as a mean initial DNP rate (Table 2). In Figure 8 we have plotted the obtained average DNP rate together against the calculated average 〈r−6〉 for each labeling position and side chain combination. Although the data set is rather limited, we already find the expected trend for several labeling positions and amino acid types, however, the linear regression yields a rather poor R2 value of −0.03. The negative sign of this coefficient of determination indicates that the assumed proportionality yields a larger squared sum of errors as compared to a model where no dependence exists between the parameters. Note that we have not been able to determine a reliable rate for the single His in A28C and G75C due to poor SNR ratio and large resulting scatter of the build-up data, also for His in F4C the error is rather large because the signal intensity is small and no averaging over several amino acid sites occurs. Therefore, we have also performed the analysis without this data point (see Figure S8), but no significant difference is observed in the goodness of the fit.

Figure 8.

Plot of the experimentally measured initial DNP rate versus the effective (inverse) Gd3+–15N distance calculated from distributed spin pairs within computational structure models as is described in the text. Distances to Lys are shown as full circles, distances to Arg as open circles; data points from the F4C mutant are shown in green, from A28C in brown, and from G75C in purple. A linear regression fit through the origin is shown in red with the respective coefficient of determination. In the upper plot all Gd–15N pairs are included in the calculation of the effective DNP rate; in the lower plot spin pairs with a distance below the cutoff of 12 Å are excluded. These pairs are expected to be situated within the bleaching volume of Gd3+. A full display of all tested cutoffs between 6 and 20 Å is shown in Figure S8.

The expected dependence is highly sensitive to relatively short distances because they are weighted very strongly due to the r−6 scaling. At the same time, very short distances should be also affected by paramagnetic bleaching in a way that their relative contribution might be diminished. To test this possibility, we excluded certain spin label conformer/protein model combinations from the statistical analysis where the distance between Gd3+ and an individual amino acid side chain falls below a specific cutoff (see Figure S7). This binary model is rather simple from a physical perspective (Gd3+–15N pairs either contribute to the observed NMR signal if their distance is larger or they do not contribute if it is shorter than the cutoff); in a more sophisticated model the broadening should be continuous and as such the distance cutoff should be spread over a spherical shell of a certain thickness. However, given the limited experimental data the simple binary model suffices to demonstrate the general applicability. We have varied the cutoff distance between 6 and 20 Å and have found that a cutoff distance of 12 Å (see Figure 8, bottom) dramatically improves the linearity of the correlation which now yields an excellent regression with R2 = 0.95 (as compared to −0.03 without any cutoff). At even larger cutoff distances the quality of the linear regression decays again (see Figure S8 for a full comparison of all tested cutoffs between 6 and 20 Å). Here, we have also tested the robustness of the analysis by excluding the error prone F4C His, which slightly improves the goodness of the fit to R2 = 0.98 but does not influence the overall picture. We can also compare the estimated cutoff value to a similar measure published earlier by analyzing signal bleaching in homogeneous Gd-DOTA solution, where a volume of 127 nm3 within which 1H spins do not contribute to a cross-polarization (CP) MAS spectrum of urea was determined.24 By taking the smaller gyromagnetic ratio into account this would relate to a 12.9 nm3 bleaching volume for 15N. Assuming a spherical geometry, we arrive at a bleaching radius of 14.5 Å which matches reasonably well our above observation, considering that CP transfer should be more sensitive to paramagnetic relaxation. Thus, our analysis strongly suggests that indeed the initial DNP rate increases as expected with r−6 at shorter distances, however, if the distance of an electron–nuclear spin pair falls below a certain value, paramagnetic bleaching deletes the contribution of this pair and critically skews the expected distance dependence.

Conclusion

We have shown that the distance between electron spins and nuclear spins may be assessed by measurement of the initial direct DNP rate as long as spin diffusion and “background” nuclear relaxation may be neglected. This approach has several practical advantages. First, it is not necessary to measure the absolute DNP signal enhancement as long as a sizeable DNP enhancement is achieved (e.g., that no NMR spectrum is obtained under same experimental parameters but in the absence of μw irradiation). This saves precious instrument time otherwise wasted on recording a low thermal polarization signal—which might even be impossible to detect at all. Second, knowledge of the actual build-up time constant—and thus measurement of a full build-up curve which might require polarization times on the order of hours—is not necessary. In contrast, a short initial build-up curve with maximum polarization times up to a few tens of seconds is sufficient. This allows for fast accumulation of transients and rather short experiments. These relatively quickly obtained initial DNP rates may then be compared for different e–n pairs or analyzed by calibration with a distance ruler. As a result, we postulate that the measurement of the initial direct DNP build-up rate is an effective and efficient tool to extract the distance between a polarizing electron spin and nuclei within a weakly-interacting, sparse network.

Furthermore, this method finally allows us to draw crucial conclusions about the quantitative distance dependence of DNP which has been elusive in the past. For this, the computationally generated distance distributions are extremely valuable (see Figure S7). Efficient DNP buildup can only be observed in cases where the distributions reach well inside the bleaching radius of ~12 Å (Arg in G75C as well as Lys in F4C and A28C). On the other hand, we see truly negligible DNP buildup for Arg in F4C where all side chain 15N are distributed with a minimum distance of ≥ 20 Å. As an intermediate case, we have measured a significant but weaker buildup in two cases where the effective distance lies in the range between 20 and 23 Å but several residues’ distance distributions reach the cutoff distance (Arg in A28C and Lys in G75C). This leads us to the conclusion that a direct, non-relayed DNP transfer to 15N can be most effectively utilized and detected at distances slightly outside the bleaching radius of ~12 Å and no effective DNP seems to be observable at distances above 20 Å. Therefore, direct DNP with attenuated spin-diffusion relay may be a highly specific method to only detect hyperpolarized nuclear spins within a narrow shell around the polarizing agent. However, care has to be taken in order to prevent potential misinterpretation of results. For short electron–nuclear distances, deleterious paramagnetic effects can dramatically skew the contribution of observed transfer rates within a conformational distribution. For long electron–nuclear distances, the risk of misinterpretation is low since in cases where our theoretical model fails (i.e., kDNP being of similar magnitude as R1n) vanishing DNP enhancement and thus no significant contribution to the measured NMR signal is expected. Furthermore, our method should be generally applicable also to other spin-1/2 nuclides with accessible distance ranges depending on their gyromagnetic ratio, as long as spin diffusion is sufficiently suppressed.

By applying our method to other systems where ideally individual electron–nuclear spin pairs may be addressed, it should be possible to gain important knowledge about the absolute DNP transfer. In combination with novel methods which push the boundaries of DNP towards closer distances between the electron and the detected nuclear spins, such as pulsed DNP2, 55–58 or electron decoupling59, 60, this could lead to direct DNP becoming an important tool for the accurate measurement of electron–nuclear distances in both biomolecular systems and materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work has been funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through Emmy Noether grants CO802/2-1 and CO802/2-2 and through Collaborative Research Center 902: Molecular Mechanisms of RNA-based regulation (project-ID 161793742). Further financial support from the Center for Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance (BMRZ, Frankfurt am Main) is acknowledged. Funding for BMRZ comes from the state of Hesse. G. K. was funded through an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship (18POST34080422) and NIH grant R01 GM 080403 awarded to Jens Meiler. E. C. was supported by a stipend of the Polytechnische Gesellschaft. We thank J. Plackmeyer (Frankfurt) for providing Gd-DOTA, Gerd Buntkowsky (Darmstadt) for access to the DNP spectrometer, as well as Torsten Gutmann and Vytautas Klimavičius (Darmstadt) for practical support.

Abbreviations

- 4MMDPA

4-Mercaptomethyl-dipicolinic acid

- DOTA

1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetra-acetic acid

- DOTA-M

1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7-tris-acetic acid-10-maleimidoethylacetamide

Footnotes

Accepted Manuscripts are published online shortly after acceptance, before technical editing, formatting and proof reading. Using this free service, authors can make their results available to the community, in citable form, before we publish the edited article. We will replace this Accepted Manuscript with the edited and formatted Advance Article as soon as it is available.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an Accepted Manuscript, which has been through the Royal Society of Chemistry peer review process and has been accepted for publication.

References

- 1.Lilly Thankamony AS, Wittmann JJ, Kaushik M and Corzilius B, Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc, 2017, 102–103, 120–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corzilius B, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem, 2020, 71, 143–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ni QZ, Daviso E, Can TV, Markhasin E, Jawla SK, Swager TM, Temkin RJ, Herzfeld J and Griffin RG, Acc. Chem. Res, 2013, 46, 1933–1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu KN, Debelouchina GT, Smith AA and Griffin RG, J. Chem. Phys, 2011, 134, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimon D, Feintuch A, Goldfarb D and Vega S, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 2014, 16, 6687–6699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hovav Y, Feintuch A and Vega S, J. Magn. Reson, 2010, 207, 176–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corzilius B, Smith AA and Griffin RG, J. Chem. Phys, 2012, 137, 054201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hovav Y, Feintuch A and Vega S, J. Magn. Reson, 2012, 214, 29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thurber KR and Tycko R, J. Chem. Phys, 2012, 137, 084508–084514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mentink-Vigier F, Akbey Ü, Hovav Y, Vega S, Oschkinat H and Feintuch A, J. Magn. Reson, 2012, 224, 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corzilius B, Smith AA, Barnes AB, Luchinat C, Bertini I and Griffin RG, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2011, 133, 5648–5651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corzilius B, eMagRes, 2018, 7, 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corzilius B, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 2016, 18, 27190–27204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaushik M, Bahrenberg T, Can TV, Caporini MA, Silvers R, Heiliger J, Smith AA, Schwalbe H, Griffin RG and Corzilius B, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 2016, 18, 27205–27218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chakrabarty T, Goldin N, Feintuch A, Houben L and Leskes M, ChemPhysChem, 2018, 19, 2139–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolf T, Kumar S, Singh H, Chakrabarty T, Aussenac F, Frenkel AI, Major DT and Leskes M, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2019, 141, 451–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harchol A, Reuveni G, Ri V, Thomas B, Carmieli R, Herber RH, Kim C and Leskes M, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2020, 124, 7082–7090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haze O, Corzilius B, Smith AA, Griffin RG and Swager TM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134, 14287–14290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hubbell WL, Gross A, Langen R and Lietzow MA, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol, 1998, 8, 649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pintacuda G, John M, Su X-C and Otting G, Acc. Chem. Res, 2007, 40, 206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevanato G, Kubicki DJ, Menzildjian G, Chauvin A-S, Keller K, Yulikov M, Jeschke G, Mazzanti M and Emsley L, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2019, 141, 8746–8751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lange S, Linden AH, Akbey Ü, Franks WT, Loening NM, van Rossum B-J and Oschkinat H, J. Magn. Reson, 2012, 216, 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossini AJ, Zagdoun A, Lelli M, Gajan D, Rascon F, Rosay M, Maas WE, Coperet C, Lesage A and Emsley L, Chemical Science, 2012, 3, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corzilius B, Andreas LB, Smith AA, Ni QZ and Griffin RG, J. Magn. Reson, 2014, 240, 113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wittmann JJ, Eckardt M, Harneit W and Corzilius B, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 2018, 20, 11418–11429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andreas LB, Barnes AB, Corzilius B, Chou JJ, Miller EA, Caporini M, Rosay M and Griffin RG, Biochemistry, 2013, 52, 2774–2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith AN, Caporini MA, Fanucci GE and Long JR, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 1542–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernández-de-Alba C, Takahashi H, Richard A, Chenavier Y, Dubois L, Maurel V, Lee D, Hediger S and De Paëpe G, Chemistry – A European Journal, 2015, 21, 4512–4517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voinov MA, Good DB, Ward ME, Milikisiyants S, Marek A, Caporini MA, Rosay M, Munro RA, Ljumovic M, Brown LS, Ladizhansky V and Smirnov AI, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2015, 119, 10180–10190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Cruijsen EAW, Koers EJ, Sauvée C, Hulse RE, Weingarth M, Ouari O, Perozo E, Tordo P and Baldus M, Chemistry – A European Journal, 2015, 21, 12971–12977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viennet T, Viegas A, Kuepper A, Arens S, Gelev V, Petrov O, Grossmann TN, Heise H and Etzkorn M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2016, 55, 10746–10750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogawski R, Sergeyev IV, Li Y, Ottaviani MF, Cornish V and McDermott AE, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2017, 121, 1169–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wenk P, Kaushik M, Richter D, Vogel M, Suess B and Corzilius B, J. Biomol. NMR, 2015, 63, 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daube D, Vogel M, Suess B and Corzilius B, Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson, 2019, 101, 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aladin V and Corzilius B, eMagRes, 2020, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corzilius B, Michaelis VK, Penzel SA, Ravera E, Smith AA, Luchinat C and Griffin RG, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2014, 136, 11716–11727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu M, Wang M, Sergeyev IV, Quinn CM, Struppe J, Rosay M, Maas W, Gronenborn AM and Polenova T, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2019, 141, 5681–5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Potapov A, Yagi H, Huber T, Jergic S, Dixon NE, Otting G and Goldfarb D, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2010, 132, 9040–9048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martorana A, Bellapadrona G, Feintuch A, Di Gregorio E, Aime S and Goldfarb D, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2014, 136, 13458–13465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solomon I, Phys. Rev, 1955, 99, 559–565. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bertini I, Luchinat C and Parigi G, Concepts Magn. Reson, 2002, 14, 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nadaud PS, Helmus JJ, Kall SL and Jaroniec CP, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2009, 131, 8108–8120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jardón-Álvarez D, Reuveni G, Harchol A and Leskes M, J. Phys. Chem. Lett, 2020, 11, 5439–5445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ni QZ, Markhasin E, Can TV, Corzilius B, Tan KO, Barnes AB, Daviso E, Su Y, Herzfeld J and Griffin RG, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2017, 121, 4997–5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bloembergen N, Physica, 1949, 15, 386–426. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daube D, Aladin V, Heiliger J, Wittmann JJ, Barthelmes D, Bengs C, Schwalbe H and Corzilius B, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2016, 138, 16572–16575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aladin V and Corzilius B, Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson, 2019, 99, 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gražulis S, Chateigner D, Downs RT, Yokochi AFT, Quirós M, Lutterotti L, Manakova E, Butkus J, Moeck P and Le Bail A, J. Appl. Crystallogr, 2009, 42, 726–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gražulis S, Daškevič A, Merkys A, Chateigner D, Lutterotti L, Quirós M, Serebryanaya NR, Moeck P, Downs RT and Le Bail A, Nucleic Acids Res, 2011, 40, D420–D427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leman JK, Weitzner BD, Lewis SM, Adolf-Bryfogle J, Alam N, Alford RF, Aprahamian M, Baker D, Barlow KA, Barth P, Basanta B, Bender BJ, Blacklock K, Bonet J, Boyken SE, Bradley P, Bystroff C, Conway P, Cooper S, Correia BE, Coventry B, Das R, De Jong RM, DiMaio F, Dsilva L, Dunbrack R, Ford AS, Frenz B, Fu DY, Geniesse C, Goldschmidt L, Gowthaman R, Gray JJ, Gront D, Guffy S, Horowitz S, Huang P-S, Huber T, Jacobs TM, Jeliazkov JR, Johnson DK, Kappel K, Karanicolas J, Khakzad H, Khar KR, Khare SD, Khatib F, Khramushin A, King IC, Kleffner R, Koepnick B, Kortemme T, Kuenze G, Kuhlman B, Kuroda D, Labonte JW, Lai JK, Lapidoth G, Leaver-Fay A, Lindert S, Linsky T, London N, Lubin JH, Lyskov S, Maguire J, Malmström L, Marcos E, Marcu O, Marze NA, Meiler J, Moretti R, Mulligan VK, Nerli S, Norn C, Ó’Conchúir S, Ollikainen N, Ovchinnikov S, Pacella MS, Pan X, Park H, Pavlovicz RE, Pethe M, Pierce BG, Pilla KB, Raveh B, Renfrew PD, Burman SSR, Rubenstein A, Sauer MF, Scheck A, Schief W, Schueler-Furman O, Sedan Y, Sevy AM, Sgourakis NG, Shi L, Siegel JB, Silva D-A, Smith S, Song Y, Stein A, Szegedy M, Teets FD, Thyme SB, Wang RY-R, Watkins A, Zimmerman L and Bonneau R, Nat. Methods, 2020, 17, 665–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hagelueken G, Ward R, Naismith JH and Schiemann O, Appl. Magn. Reson, 2012, 42, 377–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alford RF, Leaver-Fay A, Jeliazkov JR, O’Meara MJ, DiMaio FP, Park H, Shapovalov MV, Renfrew PD, Mulligan VK, Kappel K, Labonte JW, Pacella MS, Bonneau R, Bradley P, Dunbrack RL Jr., Das R, Baker D, Kuhlman B, Kortemme T and Gray JJ, J. Chem. Theory Comput, 2017, 13, 3031–3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cornilescu G, Marquardt JL, Ottiger M and Bax A, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1998, 120, 6836–6837. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Conway P, Tyka MD, DiMaio F, Konerding DE and Baker D, Protein Sci, 2014, 23, 47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mathies G, Jain S, Reese M and Griffin RG, J. Phys. Chem. Lett, 2016, 7, 111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Can TV, Weber RT, Walish JJ, Swager TM and Griffin RG, J. Chem. Phys, 2017, 146, 154204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jain SK, Mathies G and Griffin RG, J. Chem. Phys, 2017, 147, 164201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan KO, Yang C, Weber RT, Mathies G and Griffin RG, Science Advances, 2019, 5, eaav6909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saliba EP, Sesti EL, Scott FJ, Albert BJ, Choi EJ, Alaniva N, Gao C and Barnes AB, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 6310–6313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alaniva N, Saliba EP, Sesti EL, Judge PT and Barnes AB, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2019, 58, 7259–7262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.