Abstract

Background

People with multiple sclerosis (MS) have varied experiences and approaches to self‐management. This review aimed to explore the experiences of people with MS, and consider the implications of these experiences for clinical practice and research.

Methods

A meta‐synthesis of the qualitative literature examining experiences of people with MS was conducted using systematic searches of ProQuest, PubMed, CINAHL and PsycINFO. We incorporated feedback from team members with MS as expert patient knowledge‐users to capture the complex subjectivities of persons with lived experience responding to research on lived experience of the same disease.

Results

Of 1680 unique articles, 77 met the inclusion criteria. We identified five experiential themes: (a) the quest for knowledge, expertise and understanding, (b) uncertain trajectories (c) loss of valued roles and activities, and the threat of a changing identity, (d) managing fatigue and its impacts on life and relationships, and (f) adapting to life with MS. These themes were distributed across three domains related to disease (symptoms; diagnosis; progression and relapse) and two contexts (the health‐care sector; and work, social and family life).

Conclusion

The majority of people in the studies included in this review expressed a determination to adapt to MS, indicating a strong motivation for people with MS and clinicians to collaborate in the quest for knowledge. Clinicians caring for people with MS need to consider the experiential and social outcomes of this disease such as fatigue and the preservation of valued social roles, and incorporate this into case management and clinical planning.

Keywords: MS, multiple sclerosis, patient experience, perceptions, review literature

1. INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is one of the most common inflammatory neurological conditions and a major cause of non‐traumatic neurologic disability among younger adults. 1 Worldwide, more than 2.2 million people, mostly female, are estimated to be affected. 1 MS varies in its presentation, clinical course and the frequency and severity of symptoms experienced. Many people present initially with a relapsing‐remitting form of the disease, characterized by symptom‐free periods and recovery which follow attacks or relapses. 2 For others, MS begins as a primary progressive form, or develops into secondary progressive MS, with gradual worsening of neurological symptoms and increasing disability over time. 2

Although several risk factors have been identified, the cause of MS remains unknown and to date, there is no known cure. 2 , 3 Many disease‐modifying therapies are available that can reduce symptoms and relapse frequency, with the ultimate aim of preventing all disease activity. 4 Most of these treatments modify immunity and are administered variously via oral, intramuscular, subcutaneous and intravenous routes. All treatments carry risk of side effects, including pervasive flu‐like symptoms as a direct consequence of treatment (type 1 interferons), heightened susceptibility to infections as a result of immune suppression, and drug hypersensitivity and injection site reactions, 5 which can impact people's willingness to use them. 6 Overall, the relationship between therapies and disease outcomes is uncertain for any particular person, as is the range of side‐effects a person may experience.

Perhaps because of the heterogeneity of disease experiences of MS, the literature has tended to atomize, rather than synthesize these experiences. Qualitative studies have focused on the experiences of people with MS at particular points in time (eg diagnosis, early stage and relapse), 7 , 8 in specific populations (eg women and mothers), 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 in relation to specific assessments or interventions (eg rehabilitation, physical activity, disease‐modifying therapies or alternative therapies), 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 or of specific symptoms or consequences (eg fatigue or sexual dysfunction). 18 , 19 , 20

The purpose of this review was to: (a) conduct a systematic search of the published qualitative literature on the experiences of people with MS; (b) synthesize the results to elucidate the common impacts of MS on people's lives; and (c) discuss these experiences in relation to clinical practice and research.

2. METHODS

We used the scoping review approach described by Arksey and O'Malley 23 and enhanced by Levac et al 24 and involved six stages: (a) identifying the research question, (b) identifying relevant studies, (c) selecting studies, (d) charting the data, (e) collating, summarizing and reporting the results, and (f) consulting with relevant stakeholders. Our collation and summation of the results involved arriving at a consensus of the overarching themes derived from the included studies and a meta‐synthesis of these.

The multidisciplinary research team involved in this project was comprised of clinicians, academics and people living with MS. The researchers leading this review had expertise in qualitative research methods and a variety of review methodologies.

2.1. Research question

The overarching question underpinning this review was as follows: How do people experience living with MS? Two further questions were defined: (a) What are the key experiences explored in the qualitative literature? and (b) What common themes underpin these experiences?

2.2. Searches

Systematic searches were conducted in ProQuest, PubMed, CINAHL and PsychINFO using the search string (‘multiple sclerosis’) AND (experienc* OR perception* OR perspective* OR attitude* OR belief* OR value* OR view*) AND (qualitative OR ‘focus group*’ OR interview* OR narrative*).

2.3. Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were studies with empirical qualitative data about adults’ subjective experiences of living with MS (2010 to January 2019). Mixed‐method studies were included if qualitative data could be extracted. Studies that focused on the experience of others (eg carer/family/health‐care professionals) were excluded. Studies in the grey literature and those not written in English were also excluded.

Experiences of the person with MS included physical, social and/or psychological impacts of the disease, health systems and services, health‐care professional interactions and disease management. Studies describing experiences related to specific interventions or treatments (eg a specific activity programme as opposed to all physical exercise or a specific drug as opposed to all disease‐modifying therapies) were excluded.

2.4. Study quality assessment

All included studies were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) qualitative checklist 25 by two researchers working independently. Title and abstract, and full‐text screening was performed by two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

2.5. Charting the data

A thematic analytical approach was adopted to provide a rich description of MS experiences. 26 Data familiarization was achieved through several stages of article review. Coding and interpretation began at title and abstract screening, and were refined as the data were reviewed. Initial coding involved arranging‐related types of experiences conceptually into categories, capturing disease domains (diagnosis, progression and relapse, physical and psychological symptoms) and contexts of people's lives (work, social and family life; the health sector). We coded and compared the breadth and commonalities of experience across these domains and contexts. Final coding was conducted using NVivo 12, a qualitative data analysis computer software package. 27

We undertook blinded audits to ensure consistency of codes and concepts between reviewers. Any differences in approaches were resolved through discussion across the research team.

2.6. Synthesis with knowledge experts

To improve the authenticity of the synthesis, 28 research team members with MS read the analyses and contributed personalized reflections, which were translated into I‐poem 29 or narratives to capture the complex subjectivities of persons with lived experience responding to research on lived experience of the same disease.

2.7. Ethical approval

This review did not include direct involvement with human participants; it was a secondary analysis of research data, and therefore in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018) did not require ethical approval. 30

3. RESULTS

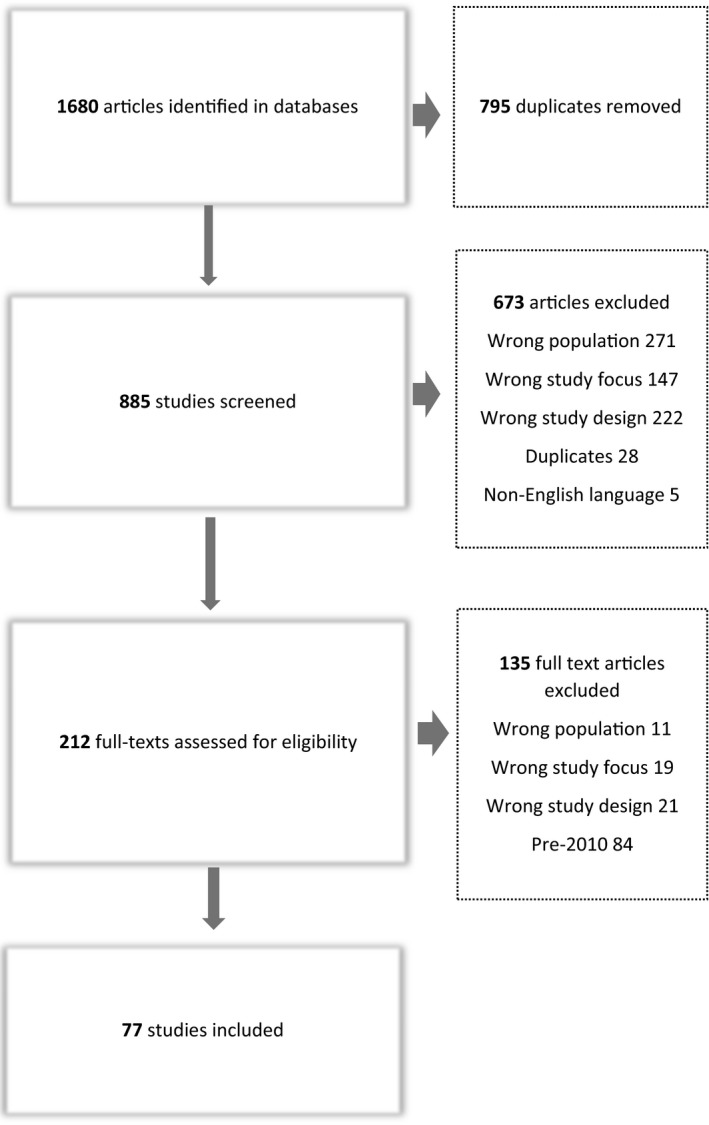

Of 1680 articles identified in the initial search, 77 met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Ages of participants ranged from 18 to 81 years; two‐thirds were female. The data collection method used most frequently was interviews (84%), followed by focus groups (14%) (Table 1). The country of participants’ origin most represented in the studies was the UK (23%), followed by the United States (17%); Scandinavian countries (12%); and Iran (12%).

FIGURE 1.

Search flow diagram

TABLE 1.

Included studies: Descriptors and key included domains/contexts

| Author (Abbr) | Year | Country | Population | n | ♀ | ♂ | Age | Aims | Key findings | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adamson et al | 2018 | USA | PwMS | 14 | 13 | 1 | 27‐70 | To understand ways that individuals with MS who had a recent relapse describe the roles of physical activity regarding MS itself, relapse, and disability identity | There is both empowerment and guilt in physical activity. Empowerment comes from feelings of taking control of MS, and guilt may develop through perceptions of disengaging with exercise | √ | √ | |||

| Al‐Sharman et al | 2018 | Jordan | PwMS | 16 | 8 | 8 | 22‐57 | To explore experiences and challenges of living with MS from a Jordanian perspective | Provides an overview of the experience of living with MS in Jordan, as conceptualized through two distinct areas of experience – that is, disease related experiences and experiences with the health‐care system | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Aminian et al | 2017 | Canada | PwMS | 15 | 12 | 3 | 23‐61 | To see whether replacing sedentary behaviour with light activities to manage MS symptoms | Adults with MS were open to replace sitting with light activities | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Anderson et al | 2013 | UK | Women with MS | 9 | 9 | 18‐50 | To identify concerns with pregnancy and mothering | Women with MS have difficulty in finding the correct information on how pregnancy will affect their MS. Main concerns surround theirs and their baby's future well‐being | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Asanao et al | 2015 | Canada/USA | PwMS relapse | 17 | 16 | 1 | 26‐69 | To explore how PwMS process their relapse experience and manage the consequences | There is a need for multidisciplinary post‐relapse care beyond restoring functional limitations in the acute phase of relapse | √ | ||||

| Blundell Jones et al | 2014 | UK | Women with MS | 10 | 10 | 30‐64 | To explore the emotional experiences and help‐seeking behaviours of women with MS | Non‐help seeking was influenced by desire to keep things normal and a lack of knowledge regarding service provision. More holistic care from services was desired | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Bogenscutz et al | 2016 | USA | PwMS | 27 | 19 | 6 | 20‐69 | To examine work‐related experiences of PwMS | Unpredictability of MS, effects on cognitive capabilities and physical stamina, and concerns about seeking workplace accommodations severely undermined prospects for continued work and education | √ | ||||

| Bogosian et al | 2017 | UK | PwMS | 34 | 25 | 9 | 41‐77 | To examine cognitive and behavioural challenges and adaptations for PwMS | Adjusting to MS following diagnosis a fluid process and involves decisions about whether to reveal or conceal the condition | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Browne et al | 2015 | UK (Ireland) | PwMS | 19 | 11 | 8 | 37‐64 | To understand how bladder dysfunction interferes with quality of life | Bladder dysfunction is a major disruption to living with MS. In view of difficult to navigate health systems and services, many people with MS attempt to self‐manage | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Brunn Helland et al | 2015 | Norway | PwMS | 27 | 16 | 11 | 37‐71 | To identify factors influencing use of rehab services | Communication skills including information giving skills of neurologist on diagnosis need improvement, and patients need equal access to information about rehabilitation options | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Chard | 2017 | USA | PwMS doing aquatic exercise | 45 | 18+ | To determine attitudes and experiences of PwMS re aquatic exercise | Both MS‐specific exercise groups and general exercise groups provide positive exercise experiences, a history of previous exercise is not key to taking it up, class satisfaction based of sense of acceptance and good instructor, and HCPs could play a stronger role in encouraging PwMS | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Coenen et al | 2011 | Germany | PwMS | 27 | 19 | 8 | 28‐73 | To explore impacts of MS on functioning and disability | Functioning and disability in MS can be influenced by a range of complex and multidimensional environmental and personal factors | √ | √ | |||

| Cowan et al | 2018 | Australia | PwMS after discharge from rehabilitation | 15 | 9 | 6 | 25‐64 | To explore lived experiences after inpatient rehabilitation and discharge home | Physical and mental fatigue impacted on all aspects of day‐to‐day life after rehabilitation. A desire for independence and concerns over burden on family were experienced, as was a loss of valued roles including work | √ | √ | √ | ||

| de Ceuninck van Capelle et al | 2016 | Netherlands | PwMS recently diagnosed | 10 | 8 | 2 | 27‐51 | To understand how recently diagnosed PwMS experience family life | MS affected family life and perceived ability to care for their family and home. Given the pivotal role of this worry, more family‐centred care should be integrated into MS care | √ | √ | |||

| de Ceuninck van Capelle et al | 2017 | Netherlands | PwRRMS | 10 | 8 | 2 | 27‐51 | To explore patient's perspectives on using disease‐modifying therapies (DMTs) for MS | The use of DMTs and dealing with advice to start them are a complicated treatment step. Decision is not made in isolation, but is grounded in the support/advice from relatives and friends | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Deghan‐Nayeri et al | 2018 | Iran | Women with MS | 25 | 25 | 21‐45 | To understand the sexual life and experiences of Iranian women with MS in an Iranian cultural context | Hiding sexual problems from husbands is common and sexual awareness and education should be extended in the rehabilitation team | √ | √ | ||||

| Deghan‐Nayeri et al | 2017 | Iran | PwMS | 11 | 6 | 5 | 24‐46 | To understand factors affecting how PwMS cope | Coping with MS is complex and affected by both individual and broader factors, including social and economic conditions | √ | √ | |||

| Deghan‐Nayeri et al | 2018 | Iran | PwMS | 11 | 6 | 5 | 24‐46 | To understand the features of coping with MS | Identified four key features of coping with MS: acceptance, relationships, self‐regulation and self‐efficacy | √ | ||||

| Dennison et al | 2011 | UK | PwMS | 30 | 22 | 8 | 40‐50 | To identify the adjustment required when diagnosed with MS | Services for people with early‐stage MS need careful attention to ensure they are sensitive and supportive rather than threatening and alienating | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Dennison et al | 2016 | UK | PwMS | 15 | 12 | 3 | 31‐68 | To explore how pwMS experience prognostic uncertainty and communication with HCPs | PwMS developed beliefs and expectations about their prognosis, particularly about pace of worsening, with minimal input from HCPs. Prognostic information threatened a need to remain present focused and was considered emotionally dangerous | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Dlugonski et al | 2012 | USA | Women with MS | 11 | 11 | 18‐64 | To better understand the adoption and maintenance of physical activity in women w MS | Consideration of physical activity beliefs, motivations and strategies may be useful in designing behavioural interventions to increase physical activity | √ | √ | ||||

| Encarnação et al | 2016 | Portugal | PwMS | 15 | 9 | 6 | 31‐60 | To understand the perception of faith in PwMS | Faith as a resource can achieve a positive outcome and assist PwMS to develop hope | √ | √ | |||

| Fallahi et al | 2014 | Iran | PwMS | 25 | 18 | 7 | 20‐55 | To explore the experiences of PwMS in confronting their diagnosis | Confronting a diagnosis of MS may involve a need for information, decisions around revealing a diagnosis, faith in god and emotional reactions including denial, anxiety fear and confusion | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Frost et al | 2017 | UK | PwPMS | 14 | 10 | 4 | 40‐67 | To explore experiences of diagnosis and self‐management | Gender differences with coping and living with MS were identified. These are more apparent in early stages and at time of diagnosis | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Gaskill et al | 2011 | USA | PwMS who are experiencing suicidal ideation (SI) | 16 | 11 | 5 | 21‐64 | To determine whether SI is greater in PwMS than the general population | Perceived loss of control was highlighted by all participants as contributing to SI. Interventions that seek to increase control in other areas of people's lives could serve as a buffer to SI | √ | ||||

| Ghafari et al | 2014 | Iran | PwMS who are married | 25 | 18 | 7 | 20‐55 | To determine the extent and type of spousal support | PwMS would rather have more emotional support than physical support | √ | ||||

| Ghafari et al | 2015 | Iran | PwMS | 25 | 18 | 7 | 20‐55 | To identify themes and subthemes of pwMS in relation to their hospital experiences | Main themes identified were religiosity, information seeking, seeking support, hope rearing, emotional reactions, concealing disease, fighting disease and disability | √ | ||||

| Giovannetti et al | 2017 | Italy | PwMS who have requested psychosocial support | 19 | 13 | 6 | 19‐57 | To explore adjustment to MS | Psychosocial interventions can support patients to adjust and accept diagnosis of MS | √ | √ | |||

| Harrison et al | 2015 | UK | PwMS who have major pain issues | 25 | 19 | 6 | 18‐70 | To explore PwMS experiences and responses to pain, and their perspectives of pain management | Identified pain‐related beliefs, emotional reactions and disparate pain management attitudes | √ | √ | |||

| Hosseini et al | 2016 | Iran | PwMS | 34 | 25 | 9 | 23‐54 | To identify the nature of leisure activities of PwMS in the context of Iranian culture | Six categories physical, social, individual, art/cultural, educational, and spiritual/religious. Useful to understand for mental health promotion purposes and tailored interventions | √ | ||||

| Hunt et al | 2014 | UK | PwMS in Ireland | 5 | 3 | 2 | 40‐65 | To explore meanings of leisure‐based visual art making for PwMS | PwMS valued creative art making, developed friendships and it enabled respite from worry | √ | √ | |||

| Kayes et al | 2011 | Australia | PwMS | 10 | 7 | 3 | 34‐53 | To explore barriers to physical activity | Barriers to physical activity are complex due to variability of MS symptoms | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Kirk‐Brown and Van Dijk | 2014 | Australia/NZ | Employed PwMS | 40 | 28 | 12 | 18‐65 | To examine what psychosocial support PwMS require post disclosure to maintain employment | Management responses to disclosure should focus on abilities and inclusive decision making | √ | ||||

| Knaster et al | 2011 | USA | PwMS | 12 | 8 | 4 | 41‐71 | To examine how PwMS self‐manage | Self‐management involved mainlining control and adapting and altering to capabilities to perform valued roles | √ | √ | |||

| Lee Mortensen & Rasmussen | 2017 | Denmark | PwMS | 40 | 29 | 11 | 18‐63 | To explore the main factors affecting patients' preferences regarding MS treatment and health care | Ability to uphold meaningful role functioning was crucial to treatment priorities. Unmet information and support needs from HCPs especially at time of diagnosis | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Lexell et al | 2011 | Sweden | PwMS | 10 | 6 | 4 | 41‐67 | To understand how PwMS adapt to their changed physical circumstances | Participants had to be prepared to adapt to rapidly changing circumstances on a daily basis. This process was on‐going and dynamic, but motivated through achieving a desired self or family life | √ | √ | |||

| Lohne et al | 2010 | Norway | PwMS | 14 | 8 | 6 | 39‐66 | To explore how PwMS experience and understand dignity in the context of a rehabilitation ward | Invisibility of MS symptoms may influence an experience of self as invisible, and the perception that needs are not respected, affecting dignity | √ | √ | |||

| Lynass and Gillon | 2017 | UK (Scotland) | PwMS | 5 | 3 | 2 | 18+ | To explore the experience of person‐centred counselling for PwMS | Counselling was found to be helpful. Empathy and non‐directive and non‐judgemental approaches were valued as were counsellor's knowledge of MS | √ | ||||

| Lynd et al | 2018 | Canada | PwMS | 23 | 18 | 5 | 20‐72 | To explore patient preferences regarding drug treatments | Patients consider the impact and likelihood of benefits and side‐effects when making drug treatment decisions | √ | √ | |||

| Maghsoodi & Mohammadi | 2018 | Iran | Women with MS | 10 | 10 | 30‐62 | To explore the process of restoring social esteem to women with MS in Iranian culture | Social esteem was severely affected by sense of abandonment, rejection from family and friends, financial problems and feeling a burden | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Masoudi et al | 2015 | Iran | PwMS | 23 | 20‐50 | To identify experience of continuity of care for PwMS in Iran | Patients requested need for dignity and respect from carer givers, as well as empathy and knowledge of MS | √ | √ | |||||

| Meade et al | 2016 | USA | PwMS | 74 | 20‐81 | To determine the benefits/quality outcomes of working for PwMS | Participants reported a range of motivations to work including compensation, personal well‐being and to help others | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Moriya & Kutsumi | 2010 | Japan | PwMS | 9 | 6 | 3 | 31‐57 | To explore the impacts of fatigue in PwMS, especially in relation to social life and interpersonal relations | Fatigue has far reaching physical, psychological and social implications for PwMS | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Moriya & Suzuki | 2011 | Japan | PwMS | 17 | 13 | 4 | 20‐59 | To ascertain differences in symptoms experienced by individuals with MS per disease severity | Characteristics of experiences may differ because of disease severity | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Morley et al | 2013 | UK | PwMS experiencing spasticity | 10 | 7 | 3 | 20‐69 | To investigate the impact of spasticity on the lives of PwMS | Spasticity has physical, psychological and social consequences for people with MS | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Mozo‐Dutton et al | 2012 | UK | PwMS | 12 | 8 | 4 | 34‐71 | To explore the impact of MS on perceptions of self | The physical body is intrinsically linked with sense of self; however, the onset of MS does not necessarily equate to a loss of self | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Newland et al | 2012 | USA | PwMS who discuss symptoms | 16 | 12 | 4 | 25‐58 | To characterize the symptoms of PwMS in their own words | Certain common symptoms may be characterized by as association with other MS symptoms. This study found a need to develop a clinical tool to document changes in symptoms | √ | ||||

| Olsson et al | 2010 | Sweden | Women with secondary progressive MS | 15 | 15 | 35‐70 | To describe the meanings of feeling well for women with MS | Feeling well in women with MS influenced by finding a pace where 'daily life goes on' despite living with illness | √ | √ | ||||

| Olsson et al | 2011 | Sweden | Women with secondary progressive MS | 15 | 15 | 35‐71 | To understand the meanings of being received and met by others as experienced a woman with MS | Women feel valued when accepted as 'normal' and disappointed/not valued when viewed as abnormal and constantly needing to justify their situation | √ | √ | ||||

| Parton et al | 2018 | Australia | Mothers with MS | 20 | 20 | 26‐54 | To examine how women with MS construct and experience motherhood | Complexity of mothering with MS highlighted as women negotiate the fear of being a bad mother, as constructed by perceptions of self‐sacrifice and meeting their children's needs, with building resilience and character in their children. MS was a catalyst for some to engage in self‐care and provided a buffer from guilt | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Parton et al | 2017 | Australia | Mothers with MS | 20 | 20 | 26‐55 | To understand how women with MS construct their sense of self as a mother | Women with MS identified negative and positive aspects of sense of self as a mother. Health professionals can assist women better knowing how they experience living with MS as a mother | √ | |||||

| Payne & Kathryn | 2010 | NZ | Mothers with MS | 9 | 9 | 22‐45 | To explore experience of mothers with MS, and elicit the strategies used to manage mothering and MS | Support is pivotal to mothers with MS, as is the need to conserve energy to manage fatigue | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Ploughman et al | 2012 | Canada | Older PwMS | 18 | 14 | 4 | 56‐81 | To explore older people's experiences of ageing with MS | Dealing with loss and navigating barriers, especially in the areas of employment, independence and social participation are critical components of self‐management' | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Plow & Finnlayson | 2012 | USA | PwMS | 8 | 6 | 2 | 29‐58 | To explore the experience of how PwMS participate in domestic life activities | Nutrition plays an important yet overlooked part in MS management – difficult symptoms, the social environment and a lack of information play a role in preventing PwMS from engaging in healthy eating behaviours | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Pretorius & Joubert | 2014 | South Africa | PwMS | 10 | 7 | 3 | 38‐71 | To explore the experiences of PwMS in the South African (SA) Context | The study highlights several key challenges (diagnosis, daily life, invisible illness and medical aid) and resources (social support, mobility aids, religion and knowledge) for PwMS in SA | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Riazi et al | 2012 | UK | PwMS in care homes | 21 | 10 | 11 | 43‐80 | To examine the experiences of care home residents with MS | Quality of life in care home residents could be improved by involving family, supporting transitions and improving access to services such as rehabilitation | √ | √ | |||

| Rintel et al | 2012 | USA | PwMS who had received mental health care | 54 | 44 | 10 | 18+ | To explore the experience of mental health care in PwMS | Mental health care should be provided upon diagnosis of MS, and providers should be familiar with MS | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Russell et al | 2018 | Australia | PwMS with recent diagnosis | 11 | 9 | 2 | 31‐70 | To explore responses to diet after recent diagnosis of MS | Lack of information specific to MS, and specific to individuals with MS, surrounding dietary advice | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Senders et al | 2016 | USA | PwMS | 34 | 30 | 4 | 18+ | To further understand how stress is addressed in the MS medical visit | Psychological stress in PwMS is not adequately addressed during medical visits | √ | √ | |||

| Sharifi & Abbaszadeh | 2016 | Iran | PwMS | 13 | 6 | 7 | 28‐51 | To explore the daily social interactions that affect the dignity of PwMS | A range of personal and social factors can affect perceived dignity of PwMS. Dignity can be promoted through moderation of dignity‐threatening factors, and improvement of dignity enhancing factors | √ | ||||

| Skar et al | 2014 | Norway | PwMS who recently completed rehabilitation | 10 | 6 | 4 | 45‐61 | To explore the experience of rehabilitation and how it might provide psychosocial benefits | Inpatient rehab instilled sense of community, recognition and empowerment in an environment where PwMS felt free from stigma | √ | √ | |||

| Skovgaard et al | 2014 | Denmark | PwMS | 11 | 11 | 31‐39 | To explore how people with MS consider the risks of combining conventional and complementary medicines (CAM) | PwMS considered CAM to be safe as guided by the 'naturalness' of treatments, their own body sensations, trust in their CAM practitioner and a lack of dialogue from their medical doctor | √ | |||||

| Skovgaard et al | 2014 | Denmark | PwMS | 17 | 15 | 2 | 18+ | To explore issues surrounding exclusive CAM use in pwMS | Use of exclusive CAM associated with beliefs and experiences of avoiding chemical substances, strengthening the body, increasing controls and participation in one's health, and maintaining body sensations which were seen as valuable in guiding treatments decisions | √ | √ | |||

| Smith et al | 2015 | NZ | Men with MS | 18 | 18 | 36‐68 | To examine fatigue and exercise experience of men with MS | Fatigue has physical and psychological consequences for men, but goal readjustment aids men to stay engaged in exercise | √ | √ | ||||

| Smith et al | 2011 | NZ | PwMS who engage in community‐based exercise | 10 | 10 | 28‐70 | To explore how PwMS experience fatigue and how this influences participation in community‐based exercise | MS‐related fatigue is unpredictable and controlling. Regaining control over fatigue is a complex process influenced by multiple factors including feeling supported, managing limits and individual wellness philosophies/goals | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Sosnowy | 2014 | USA | Women with MS | 9 | 9 | 18+ | To examine the experiences and perspectives of women who blog about their MS | Blogging provides an opportunity to gain information and resist dominant medical discourses | √ | |||||

| Soundy et al | 2012 | UK | PwMS involved in rehabilitation | 11 | 7 | 4 | 42‐69 | To understand how PwMS in a rehabilitation setting express hope | Despite acceptance of loss, meaning and values in their life, PwMS could defy their illness through maintaining hope and a sense of purpose in life. Physiotherapists need to support this process during rehabilitation | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Stennett et al | 2018 | UK | Community dwelling PwMS | 16 | 12 | 4 | 47‐72 | To explore the meaning of physical activity to people with MS who live in the community | PwMS may describe a broad, multidimensional concept of physical activity that reflects social engagement, uncertain trajectories and coping with their illness | √ | √ | |||

| Stern & Goverover | 2018 | USA | Men with MS | 3 | 3 | 50‐57 | To present perspectives of everyday technology use for men with MS | Facilitating everyday technology use in men with MS may promote health and quality of life | √ | √ | ||||

| Stone et al | 2013 | Canada | PwMS working in academia | 35 | 20 | 10 | 33‐72 | To explore academics with MS experiences of seeking employment accommodations | Academics with MS who seek workplace adjustments can be conceptualized in terms of needing to 'go through the back door' – concealing disabilities to avoid stigma | √ | √ | |||

| Strickland et al | 2017 | UK (Scotland) | Recently diagnosed PwMS | 10 | 8 | 2 | 25‐45 | To understand the impact of a diagnosis of MS | Diagnosis of MS results in a separation from the pre‐symptomatic self, to an evolving reconstruction of identity influenced by social roles, uncertainty, availability of health care | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Tabuteau‐Harrison et al | 2016 | UK | PwMS | 15 | 11 | 4 | 42‐67 | To determine whether adjustment to MS is determined by social group factors | Social groups play an important role in adjusting to MS, and in continuing valued roles and relationships | √ | √ | |||

| Turpin et al | 2018 | Australia | PwMS who experienced fatigue | 13 | 11 | 2 | 25‐67 | To determine how individuals experienced MS fatigue | Fatigue is a challenging and debilitating MS symptom which is poorly understood and largely invisible to others | √ | √ | |||

| van der Meide et al | 2018 | Netherlands | PwMS | 13 | 13 | 18+ | Examines the bodily experiences of PwMS | People with MS experience the body through oscillating dimensions of bodily uncertainty, having a precious body, being a different body and the mindful body | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Vijayasingham et al | 2017 | Malaysia | PwMS | 10 | 6 | 4 | 25‐46 | To describe how PwMS perceive and negotiate the long‐term course of their employment | Holistic life management decisions contribute to on‐going but also disrupted work trajectories | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Willson et al | 2018 | Italy | Mothers with MS | 16 | 16 | N/A | To explore the perceived influence of MS on mothers in an Italian socio‐cultural context | MS can affect ability to participate in mothering tasks and cause subsequent feelings of difference and loss, influenced by a desire to stay in control and perceptions of stigma, which impact on women's identity as mothers | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Yilmaz et al | 2017 | Turkey | Women with MS | 21 | 21 | 23‐51 | Explores the impacts of MS in women on sexual, physical and emotional functioning | MS influences uncertainty in terms of illness and marriage, affects sexuality and influences a perceived inadequacy to engage in the role of wife and mother. Women felt a lack of support and acknowledgement of the impacts of MS on their sexual lives | √ | √ | √ |

Domains and contexts: P1: Experiences of receiving the diagnosis; P2: Experiences of health services and health professionals; P3: Experience of managing physical and psychological symptoms; P4: Experience of disease progression and relapse; P5: Experiences and effects on work, social and family life.

Abbreviations: HCP, health care provider; MS, multiple sclerosis; PwMS, people with MS.

3.1. Quality assessment

The quality of all 77 studies was considered acceptable using the CASP tool (Table S1). The criterion of adequate consideration of the relationship between researcher and participants was met in only 34% of studies. 12% of studies used recruitment strategies which we did not consider appropriate to address the aims of their study. In 13% of studies, ethical issues were either inadequately addressed, or information about consent, recruitment and/or obtaining approval of a human research ethics committee was not provided.

3.2. Qualitative synthesis

We identified five overarching themes describing people's experiences of living with MS: (a) the quest for knowledge, expertise and understanding, (b) uncertain trajectories (c) loss of valued roles and activities, and the threat of a changing identity, (d) managing fatigue and its impacts on life and relationships, and (e) adapting to life with MS. (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Thematic framework

| Theme | Domain or context | Experiences |

|---|---|---|

| A quest for knowledge, expertise and understanding | Receiving the diagnosis | |

| Physical and psychological symptoms | ||

| Work, social and family life |

|

|

| Health services and health professionals |

|

|

| Uncertain trajectories | Prior to diagnosis | |

| At diagnosis/health services and health professionals/disease progression and relapse/physical and psychological symptoms |

|

|

| Work, social and family life |

|

|

| Loss of valued roles and the threat of a changing identity | Physical and psychological symptoms |

|

| Work, social and family life |

|

|

| Managing fatigue, and its impacts on life and relationships | Physical and psychological symptoms |

|

| Work, social and family life |

|

|

| Adapting to life with MS | Physical and psychological symptoms | |

| Work, social and family life |

|

|

| Health services and health professionals |

3.2.1. A quest for knowledge, expertise and understanding

This theme included experiences related to diagnosis, treatment, and information and support seeking. While some people described a sense of relief 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 and validation 11 , 29 , 32 , 33 at diagnosis, followed by direction to support services, 32 , 33 many highlighted extensive self‐directed efforts to meet their information needs at an already stressful time. 8 , 15 , 30 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 Several studies referred to people's experiences of receiving insufficient information and support from health‐care professionals at this time. 15 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 39 People described the provision of generic advice from health‐care providers, rather than personally tailored and specific advice. 9 , 29 , 35 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 In two studies, women described receiving inadequate and conflicting information related to having children – from supportive to discouraging. 9 , 10

People with MS often had to navigate their own preconceived ideas about MS and what their future living with MS might look like; for example, they may have inferred from the frequent image of someone in a wheelchair used in popular representations of MS that this would be the outcome for all with this diagnosis. 47 Overall, a general lack of information and knowledge about MS in the community extended to their experiences of being misunderstood at work, 16 , 18 , 20 , 31 , 33 , 43 , 46 in social situations 16 , 18 , 20 , 31 , 33 , 43 , 46 , 47 , 48 and in family life. 18 , 20 , 33 , 43 , 46 , 47 , 48 Their MS symptoms were often referred to as ‘invisible’, obliging them to assert the impacts of MS on daily life and to help others understand a hidden disability. 12 , 18 , 20 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 46 , 48 , 49 , 50 Conversely, while information was welcomed by most, some described being bombarded, 15 , 51 inundated, 54 and overwhelmed 38 by advice and disease details. In response, some chose to manage anxiety about the future by only researching those symptoms that were of current concern to them. 38 People with MS described varied alternative paths of self‐directed research using resources such as the internet, 9 , 18 , 31 , 35 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 books, 9 , 18 , 31 , 35 , 54 peer group support networks, 9 , 18 , 31 media, 18 , 52 friends 52 , 53 and MS associations. 35 , 53 , 55

3.2.2. Uncertain trajectories and a need to plan

This theme described the inherent uncertainty people with MS experienced across all aspects of their lives. It was expressed around the time of diagnosis, 7 , 8 , 10 , 15 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 regarding treatment, 6 , 13 , 39 , 42 , 56 and in terms of the potential future impacts of MS progression, especially on work, 33 , 41 , 54 , 57 family and relationships. 9 , 12 , 19 , 45

Several studies included experiences of physical and psychological symptoms presenting themselves acutely and without warning. These included bladder symptoms, 44 pain, 58 fatigue, 32 , 49 , 58 , 59 spasticity, 62 speech problems, 63 balance disturbances, 43 and cognitive and mood changes. 64 This unpredictability caused worry, 41 , 42 , 51 made it difficult to plan, 36 , 41 , 42 , 51 , 56 , 58 and disrupted valued roles and activities, 20 , 36 , 41 , 42 , 51 , 56 , 58 , 60 and everyday routines. 20 , 41 , 42 , 60

Lack of certainty about treatment effectiveness, including impact on clinical course, made it difficult to make decisions about which treatments to choose, especially considering potential significant side‐effects and impact on quality of life. 13 , 39 In a study of the exclusive use of alternative medicine by people with MS, interviewees described the lack of certainty regarding the impact and long‐term effects of conventional medicines as a deterrent to their use, leading to the adoption of alternative modes of therapy, which were represented as delivering more certainty of outcome. 19 At the same time, uncertainty surrounding clinical course, and prognostication, appeared to provide respite from a fearful future, or be a source of hope for some. 30 , 35

3.2.3. Loss of valued roles and activities, and the threat of a changing identity

The impact and fear of future impact of MS on valued roles and activities were frequently reported, reflecting the way that MS posed challenges to self‐perceptions and perceived identity, and difficulties in adapting to a changing body and altered capabilities. 38 Guilt and shame associated with changing roles and abilities affecting family dynamics were expressed, 12 , 30 , 48 , 63 including an inability to provide for family through loss of employment and income. 33 , 61 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 Many studies highlighted the impact of MS on people's careers and employment. 7 , 41 , 48 , 51 , 57 , 61 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 The presence of supportive structures and environments at work were factors influencing whether people living with MS chose to remain in employment or not. 57 , 73

Disclosing or concealing a diagnosis was an important consideration in maintaining a sense of identity and avoiding stigma. Studies described concealing a MS diagnosis in the workplace 7 , 30 , 33 , 57 , 64 , 73 and social life. 7 , 30 , 33 , 64 Reasons included maintaining professional perceptions, 64 , 73 not wanting to be seen as different or disabled, 33 , 40 , 45 , 57 , 63 , 64 , 73 and uncertainty about how others would respond. 7 , 45 , 57 , 71 When people living with MS did disclose their diagnosis, they reported both positive reactions, such as being supported and accommodated, 64 , 73 , 74 and negative reactions, including having their work competency questioned 41 , 57 , 74 and being treated dismissively. 57 , 73 , 74

3.2.4. Managing fatigue, and its impacts on life and relationships

Managing fatigue required constant planning and pacing of tasks to accommodate the anticipated fatigue‐related after effects. 10 , 11 , 29 , 41 , 47 , 51 , 58 , 59 , 64 It was described in terms of its impact on work, 18 , 49 , 51 , 70 , 75 , 76 social life, 18 , 45 , 49 , 51 , 75 , 76 , 77 family life 12 , 18 , 45 , 49 , 51 , 52 , 75 , 76 , 78 and physical and psychological health. 14 , 16 , 47 , 76 People with MS described feelings of frustration about the limitations that fatigue imposed on their lives and the resulting loss of spontaneity. 18 , 29 , 47 Knowing how to manage this was a source of confusion, with some people highlighting exercise 14 , 16 , 47 , 76 and diet 49 as effective, and others attributing fatigue and relapse to incorrect, or too much, exercise. 14 , 47 Information and support to manage fatigue were found to be lacking for some, despite the significant impact it had on their lives. 18 , 20

People described emotional fatigue in relation to seeking information and support, and with interactions with health services. 38 , 46 This was influenced by an overall perceived lack of legitimacy 38 , 40 of invisible symptoms, and experiences of having to repeatedly explain or justify limitations to friends, family and workplaces, 31 , 40 , 46 , 50 to fight for needs from health professionals and government organizations, 31 , 34 , 38 , 50 and the need to regularly re‐establish relationships with rotating or changing health‐care providers. 38 , 46 Lack of community understanding about MS fatigue was recognized 22 with people reporting feelings of guilt, 18 , 51 unreliability 18 , 48 , 51 and being perceived as lazy 18 , 20 , 55 when they were unable to meet work and social commitments due to fatigue.

3.2.5. Adapting to life with MS

Strategies that people with MS used to adapt to MS ranged from, and oscillated between, denying the existence of their condition 45 to total acceptance. 14 Although denial of the diagnosis was experienced by some, 7 , 30 defiance in the sense of not letting MS and its impacts define identity, personal outlook and everyday life was most often expressed. 12 , 30 , 33 , 49 , 76

For some people with MS, initial fears surrounding dependence on aids, such as wheelchairs, were replaced with acceptance and relief, as they facilitated adaptation to certain tasks, and assisted in maintaining independence. 29 , 30 , 71 , 79 Technology and devices were valued for enabling people to stay connected to society and community, 82 follow online exercise programmes, 43 monitor activity and fitness levels, 18 and assist with daily living activities 53 and work‐related tasks. 59

The most frequently reported strategy for everyday coping was to draw on personal resources. Resources could include work, 64 , 69 spiritual faith, 33 , 70 , 81 family support 10 , 31 , 82 (including financial support to access care 13 , 66 ) and social interaction, including engaging with other people with MS. 8 , 16 , 40 , 47 , 48 , 82

Our team members with MS affirmed the themes, and articulated some linkages across the themes, in narratives synthesized into I‐poems (Box 1). These poems contributed to the title of our paper.

BOX 1 Comments on experiential themes by people with MS

| Changing identity | Quest for knowledge | Uncertainty, quest for knowledge | Fatigue |

|---|---|---|---|

|

I struggled with the identity issue for years. It struck at the heart of who I thought I was |

There is not a lack of information out there – it is the opposite But it is not personalized and varies in quality and currency The onus is on you to take control and self‐educate |

I still feel I have both too much and too little information |

In 2011 I had transverse myelitis I spent most nights in intense, painful spasms I felt my level of fatigue increase and I am still fatigued |

4. DISCUSSION

The five themes described in our review provide insight into people's experiences of MS. Most articles contained content which covered three or more domains and contexts, highlighting the interconnectedness of these experiences. For instance, experiences related to work, social and family life were rarely mentioned in isolation, and were closely linked to experiences of physical and psychological symptoms. Likewise, studies which included experiences related to receiving the diagnosis frequently referenced experiences with health services and health professionals – a pivotal point of contact, and one that is often vividly recalled, even many years after diagnosis. 85

The two themes of uncertain trajectories and quest for knowledge, expertise and understanding are interwoven – with uncertainty itself related to an enacted quest for knowledge. People living with MS often experience long‐standing and unsettling symptoms before a diagnosis of MS is confirmed. Even when there is information available, information and support seeking may be complicated by a range of factors, including lack of integrated care, limited time with health‐care professionals, lack of referral to support services, or the knowledge, communication style and focus (eg pharmacological) of health‐care providers. This was particularly highlighted prior to and around the time of receiving a MS diagnosis.

The experiences described in this review suggest that the onus is on people with MS to take control and self‐educate, despite a lack of certainty about the very information that would enable them to do so (eg unknown aetiology and unpredictable prognosis, symptom trajectories and responses to treatment). This is challenging in the context of a diverse and information‐laden health landscape. 86 In a qualitative study examining people with MS’ experiences, needs and preferences for integrating treatment information into decision making, participants described a desire for unbiased and up‐to‐date information. On the other hand, they reported an excess amount of information available, of which only a small amount was of relevance to them. 87 Overall, participants expressed a desire to develop a ‘research partnership’ with health professionals to facilitate tailoring of information to meet their unique health needs. 87 Acknowledging the presence of uncertainty with health professionals is the first step to achieve this aim.

Gheihman and colleagues 88 propose that distinguishing between the many types and meanings of knowledge uncertainty is important in determining clinical management strategies. Clarifying knowable and unknowable forms and prioritizing techniques to address these are essential, in particular minimizing unnecessary uncertainties (knowable unknowns) through the provision of information. In line with the key experiences reported by people with MS and highlighted in this paper, this approach could help to address knowledge and intervention gaps for people with MS.

Fatigue is one of the most common and debilitating symptoms of MS, and managing this was described as a constant challenge by most participants in our review. Fatigue affects more than 80% of people with MS 89 and is cited as the main reason why people with MS seek early retirement. 90 Improving people with MS’ capacity to manage fatigue should be a priority for clinicians. While clinical trials have demonstrated some benefit associated with medication, physical activity and cognitive‐behaviour therapy, 89 the experiences described in our review indicate that there is no one‐size‐fits‐all solution for fatigue.

A narrative review of apps developed to assist with MS self‐management found that most focused on physical and cognitive ability, and medication adherence, and few had been evaluated. 91 However, repeated users of one interactive web‐based program, MSmonitor, reported improved ability to self‐manage fatigue and increased health‐related quality of life. 92 Until recently, the needs of people with MS have not been accounted for in the development of apps. 93 Patient and public involvement in research refers to the conduct of research ‘by’ or ‘with’ members of the public, rather than ‘for’ or ‘about’ them. 94 Taking such an approach, a recent New Zealand study found that mobile technology provides an accessible and acceptable platform for the provision of interventions aimed at decreasing the impact and severity of fatigue in people with MS. 95 Preliminary results of a web‐based survey of people with MS, using fatigue as a moderating influence, indicated that expectations of how helpful an app would be for self‐management, and social support was one indicator of acceptance. 96 Other recent digital developments aimed at assisting people with MS to manage fatigue are involving people with MS. 91 , 93 , 95

Patient experiences are infrequent outcomes in clinical trials of novel therapeutics. In their analysis of 16 pivotal MS drug trials relating to 8 of the recently introduced therapies, Gerardi et al 98 found that all these drugs have to date been tested in 1‐ to 2‐year trials. Most drugs were compared to placebos but there have been no comparisons between established and recently introduced drugs. Two‐thirds of studies primarily examined relapse rate, with co‐primary examination of disability in two, but overall there was lack of consideration of patients’ preferences. Similarly, in their analysis of 29 Phase 3 trials of new disease‐modifying treatments for MS, Gehr and colleagues 99 found that patients’ perspectives, including experiences of fatigue, cognitive impairment, pain, sleep disorders, loss of vision and spasticity, were mostly overlooked. They recommended designing studies that align with patients’ needs to ensure that results facilitate patient‐relevant outcomes. Our review supports this contention. Inclusion of patient preferences in outcomes of clinical trials would advance resolution of patient uncertainty, assist people with MS in making decisions and advance their quest for knowledge related to unknown impacts of treatments.

4.1. Limitations

A strength of our study is the incorporation of quality appraisal, which is not a requirement of scoping review approaches. 21 , 98 The exclusion of quantitative literature meant we were not able to include examination of patient‐reported experiences and outcomes elucidated through questionnaires. Insight into these, including quality of life, cost effectiveness, patient satisfaction and enablement, is essential to gain understanding of people's perceptions of both the process and outcome of health care. 101 This paper does not address the grey literature about patient experiences, or works produced by patients themselves outside the scholarly literature, such as autobiographies and illness narratives. A few of the studies explicitly addressed people from low socio‐economic backgrounds. Some of the experiences described in this review may reflect the more individualistic cultures of the Global North, rather than more collectivist cultures. People with MS from North America and the United Kingdom accounted for 48% of the studies in this review, while there was only one study from Latin America 72 and three from Asia. 20 , 61 , 67

5. CONCLUSION

The majority of people in the studies included in this review expressed a determination to adapt to MS. The literature is replete with stories of survival and persistence, and a strong desire to remain engaged in society. The invisible aspects of MS, including fatigue, are often under‐appreciated by peers and clinicians. Our findings highlight the importance of the clinical partnerships between people with MS and their clinicians. In order to broaden their access to the ‘knowable form’ of knowledge underlying uncertainty, it is of critical importance to examine the long‐term risks and benefits of treatments, including patient‐reported outcomes, to enhance the capacities of people with MS and clinicians to make informed, person‐focused decisions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

CB, JD, AP, CL, JDr, KC, ME, VF were responsible for writing the original draft. JD, CP, CB, AP, KC,ME, CL, MC, JDr, VF, AB, HS, AT, AH were responsible for preparation, creation and presentation of the published work, specifically critical review, commentary or revision – including pre‐ or post‐publication stages. JD, CB and AP contributed to preparation, and creation and/or presentation of the published work, specifically visualization/ data presentation. JD and CP contributed to oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, including mentorship external to the core team. JD contributed to management and coordination responsibility for the research activity planning and execution, and acquisition of the financial support for the project leading to this publication.

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by and has been delivered in partnership withOur Health in Our Hands (OHIOH), a strategic initiative of the Australian National University, which aims to transform health care by developing new personalized health technologies and solutions in collaboration with patients, clinicians and health‐care providers.

Desborough J, Brunoro C, Parkinson A, et al. ‘It struck at the heart of who I thought I was’: A meta‐synthesis of the qualitative literature examining the experiences of people with multiple sclerosis. Health Expect. 2020;23:1007–1027. 10.1111/hex.13093

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors: the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supporting Information files).

REFERENCES

- 1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Nichols E, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(3):269‐285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thompson AJ, Baranzini SE, Geurts J, Hemmer B, Ciccarelli O. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2018;391(10130):1622‐1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):169‐180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Havrdova E, Galetta S, Stefoski D, Comi G. Freedom from disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;74(Suppl 3):S3‐S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Torkildsen Ø, Myhr KM, Bø L. Disease‐modifying treatments for multiple sclerosis ‐ a review of approved medications. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23(Suppl 1):18‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lynd LD, Henrich NJ, Hategeka C, et al. Perspectives of patients with multiple sclerosis on drug treatment: a qualitative study. Int J MS Care. 2018;20(6):269‐277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fallahi‐Khoshknab M, Ghafari S, Nourozi K, Mohammadi E. Confronting the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study of patient experiences. J Nurs Res. 2014;22(4):275‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dennison L, Yardley L, Devereux A, Moss‐Morris R. Experiences of adjusting to early stage multiple sclerosis. J Health Psychol. 2011;16(3):478‐488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anderson J, Wallace L. Multiple sclerosis: pregnancy and motherhood. Pract Midwife. 2013;16(6):28‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Payne D, Mc KM. Becoming mothers. Multiple sclerosis and motherhood: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(8):629‐638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Parton C, Ussher JM, Natoli S, Perz J. Being a mother with multiple sclerosis: negotiating cultural ideals of mother and child. Fem. Psychol. 2018;28(2):212‐230. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parton C, Katz T, Ussher JM. 'Normal' and 'failing' mothers: women's constructions of maternal subjectivity while living with multiple sclerosis. Health. 2019;23:516‐532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Capelle AD, van der Meide H, Vosman FJ, Visser LH. A qualitative study assessing patient perspectives in the process of decision‐making on disease modifying therapies (DMT’s) in multiple sclerosis (MS). PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kayes NM, McPherson KM, Taylor D, Schlüter PJ, Kolt GS. Facilitators and barriers to engagement in physical activity for people with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative investigation. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(8):625‐642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bruun Helland C, Holmøy T, Gulbrandsen P. Barriers and facilitators related to rehabilitation stays in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(3):122‐129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aminian S, Ezeugwu VE, Motl RW, Manns PJ. Sit less and move more: perspectives of adults with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(8):904‐911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Skovgaard L, Pedersen IK, Verhoef M. Exclusive use of alternative medicine as a positive choice: a qualitative study of treatment assumptions among people with multiple sclerosis in denmark. Int J MS Care. 2014;16(3):124‐131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Turpin M, Kerr G, Gullo H, Bennett S, Asano M, Finlayson M. Understanding and living with multiple sclerosis fatigue. Br J Occup Ther. 2018;81(2):82‐89. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yilmaz SD, Gumus H, Odabas FO, Akkurt HE, Yılmaz H. Sexual life of women with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Int J Sex Health. 2017;29(2):147‐154. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moriya R, Kutsumi M. Fatigue in Japanese people with multiple sclerosis. Nurs Health Sci. 2010;12(4):421‐428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19‐32. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . CASP qualitative checklist. 2018. https://casp‐uk.net/casp‐tools‐checklists/ Accessed June 17, 2019

- 24. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77‐101. [Google Scholar]

- 25. QSR International Pty Ltd . NVivo. 2020. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo‐products/nvivo‐12‐plus. Accessed January 13, 2020

- 26. Guba E, Lincoln YS. Effective Evaluation: Improving the Usefulness of Evaluation Results through Responsive and Naturalistic Evaluation. San Fransisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 1981https://www.amazon.com/Effective‐Evaluation‐Usefulness‐Responsive‐Naturalistic/dp/0875894933/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr= [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koelsch LE. I‐poem: evoking self. Qual Psychol. 2015;2:96‐107. [Google Scholar]

- 28. The National Health and Medical Research Council, t.A.R.C.a.U.A. , National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018). Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frost J, Grose J, Britten N. A qualitative investigation of lay perspectives of diagnosis and self‐management strategies employed by people with progressive multiple sclerosis. Health. 2017;21(3):316‐336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ploughman M, Austin MW, Murdoch M, Kearney A, Godwin M, Stefanelli M. The path to self‐management: a qualitative study involving older people with multiple sclerosis. Physiother Can. 2012;64(1):6‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pretorius C, Joubert N. The experiences of individuals with multiple sclerosis in the Western Cape, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid. 2014;19(1):1‐12. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Strickland K, Worth A, Kennedy C. The liminal self in people with multiple sclerosis: an interpretative phenomenological exploration of being diagnosed. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(11–12):1714‐1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blundell Jones J, Walsh S, Isaac C. ‘Putting one foot in front of the other’: a qualitative study of emotional experiences and help‐seeking in women with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2014;21(4):356‐373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sosnowy C. Practicing patienthood online: social media, chronic illness, and lay expertise. Societies. 2014;4(2):316‐329. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dennison L, McCloy Smith E, Bradbury K, Galea I. How do people with multiple sclerosis experience prognostic uncertainty and prognosis communication? a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mozo‐Dutton L, Simpson J, Boot J. MS and me: exploring the impact of multiple sclerosis on perceptions of self. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(14):1208‐1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Russell RD, Black LJ, Sherriff JL, Begley A. Dietary responses to a multiple sclerosis diagnosis: a qualitative study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73(4):601‐608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rintell D, Frankel D, Minden SL, Glanz BI. Patients' perspectives on quality of mental health care for people with MS. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(6):604‐610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee Mortensen G, Rasmussen PV. The impact of quality of life on treatment preferences in multiple sclerosis patients. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1789‐1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Skar AB, Folkestad H, Smedal T, Grytten N. ‘I refer to them as my colleagues’: the experience of mutual recognition of self, identity and empowerment in multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(8):672‐677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Al‐Sharman A, Khalil H, Nazzal M, et al. Living with multiple sclerosis: a Jordanian perspective. Physiother Res Int. 2018;23(2):e1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Browne C, Salmon N, Kehoe M. Bladder dysfunction and quality of life for people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(25):2350‐2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Maghsoodi S, Mohammadi N. Qualitative analysis of the process of restoring social esteem by the women with multiple sclerosis. Qual Quant. 2018;52(6):2557‐2575. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Skovgaard L, Pedersen IK, Verhoef M. Use of bodily sensations as a risk assessment tool: exploring people with multiple sclerosis' views on risks of negative interactions between herbal medicine and conventional drug therapies. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Giovannetti AM, Brambilla L, Torri Clerici V, et al. Difficulties in adjustment to multiple sclerosis: vulnerability and unpredictability of illness in the foreground. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(9):897‐903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Senders A, Sando K, Wahbeh H, Peterson Hiller A, Shinto L. Managing psychological stress in the multiple sclerosis medical visit: patient perspectives and unmet needs. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(8):1676‐1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smith C, Olson K, Hale LA, Baxter D, Schneiders AG. How does fatigue influence community‐based exercise participation in people with multiple sclerosis? Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(23–24):2362‐2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tabuteau‐Harrison SL, Haslam C, Mewse AJ. Adjusting to living with multiple sclerosis: the role of social groups. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2016;26(1):36‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lohne V, Aasgaard T, Caspari S, Slettebø Å, Nåden D. The lonely battle for dignity: individuals struggling with multiple sclerosis. Nurs Ethics. 2010;17(3):301‐311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Olsson M, Skar L, Soderberg S. Meanings of being received and met by others as experienced by women with MS. Int J Qual Stud Health Well‐being. 2011;6(1):5769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cowan CK, Pierson JM, Leggat SG. Psychosocial aspects of the lived experience of multiple sclerosis: personal perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(3):349‐359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Plow M, Finlayson M. A qualitative study of nutritional behaviors in adults with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(6):337‐350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chard S. Qualitative perspectives on aquatic exercise initiation and satisfaction among persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(13):1307‐1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dehghani AP, Dehghan Nayeri NP, Ebadi AP. Antecedents of coping with the disease in patients with multiple sclerosis. A qualitative content analysis. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2017;5(1):49‐60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Knaster ES, Yorkston KM, Johnson K, McMullen KA, Ehde DM. Perspectives on self‐management in multiple sclerosis: a focus group study. Int J MS Care. 2011;13(3):146‐152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Harrison AM, Bogosian A, Silber E, McCracken LM, Moss‐Morris R. 'It feels like someone is hammering my feet': understanding pain and its management from the perspective of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J. 2015;21(4):466‐476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bogenschutz M, Rumrill PD, Seward HE, Inge KJ, Hinterlong PC. Barriers to and facilitators of employment among Americans with multiple sclerosis: results of a qualitative focus group study. J Rehabil. 2016;82(2):59‐69. [Google Scholar]

- 58. van der Meide H, Teunissen T, Collard P, Visse M, Visser LH. The mindful body: a phenomenology of the body with multiple sclerosis. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(14):2239‐2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Newland PK, Thomas FP, Riley M, Flick LH, Fearing A. The use of focus groups to characterize symptoms in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(6):351‐357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Morley A, Tod A, Cramp M, Mawson S. The meaning of spasticity to people with multiple sclerosis: what can health professionals learn? Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(15):1284‐1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vijayasingham L, Jogulu U, Allotey P. Work change in multiple sclerosis as motivated by the pursuit of illness‐work‐life balance: a qualitative study. Mult Scler Int. 2017;2017:8010912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lynass R, Gillon E. A thematic analysis of the experience of person‐centred counselling for clients with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;32(4):49‐57. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lexell EM, Iwarsson S, Lund ML. Occupational adaptation in people with multiple sclerosis. OTJR. 2011;31(3):127‐134. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bogosian A, Morgan M, Bishop FL, Day F, Moss‐Morris R. Adjustment modes in the trajectory of progressive multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study and conceptual model. Psychol Health. 2017;32(3):343‐360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gaskill A, Foley FW, Kolzet J, Picone MA. Suicidal thinking in multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(17–18):1528‐1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ghafari S, Khoshknab MF, Norouzi K, Mohamadi E. Spousal support as experienced by people with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. J Neurosci Nurs. 2014;46(5):E15‐E24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Moriya R, Suzuki S. A qualitative study relating to the experiences of people with MS: differences by disease severity. Br J Nurs. 2011;7(4):593‐600. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sharifi S, Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A. Factors affecting dignity of patients with multiple sclerosis. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016;30(4):731‐740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Meade M, Reed KS, Rumrill P, Aust R, Krause JS. Perceptions of quality of employment outcomes after multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. J Rehabil. 2016;82(2):31‐40. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Encarnação P, Clara Costa O, Martins T. The role of faith in health promotion in patients with multiple sclerosis. Revista Brasileira em Promocao da Saude. 2016;29(4):574‐584. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ghafari S, Fallahi‐Khoshknab M, Nourozi K, Mohammadi E. Patients' experiences of adapting to multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Contemp Nurse. 2015;50(1):36‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Stennett A, De Souza L, Norris M. The meaning of exercise and physical activity in community dwelling people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(3):317‐323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Stone S‐D, Crooks VA, Owen M. Going through the back door: chronically ill academics' experiences as 'unexpected workers'. Soc Theor Health. 2013;11(2):151‐174. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kirk‐Brown AK, Van Dijk PA. An empowerment model of workplace support following disclosure, for people with MS. Mult Scler J. 2014;20(12):1624‐1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Coenen M, Basedow‐Rajwich B, König N, Kesselring J, Cieza A. Functioning and disability in multiple sclerosis from the patient perspective. Chronic Illn. 2011;7(4):291‐310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Smith CM, Fitzgerald H, Whitehead L. How fatigue influences exercise participation in men with multiple sclerosis. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(2):179‐188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hosseini SM, Asgari A, Rassafiani M, Yazdani F, Mazdeh M. Leisure time activities of Iranian patients with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Health Promot Perspect. 2016;6(1):47‐53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. de Ceuninck van Capelle A, Visser LH, Vosman F. Multiple sclerosis (MS) in the life cycle of the family: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the perspective of persons with recently diagnosed MS. Fam Syst Health. 2016;34(4):435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Dehghani A, Dehghan Nayeri N, Ebadi A. Features of coping with disease in iranian multiple sclerosis patients: a qualitative study. J Caring Sci. 2018;7(1):35‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Stern BZ, Goverover Y. Everyday technology use for men with multiple sclerosis: an occupational perspective. Br J Occup Ther. 2018;81(12):709‐716. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Soundy A, Benson J, Dawes H, Smith B, Collett J, Meaney A. Understanding hope in patients with multiple sclerosis. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(4):344‐350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Olsson M, Skar L, Soderberg S. Meanings of feeling well for women with multiple sclerosis. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(9):1254‐1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Koopman W, Schweitzer A. The journey to multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. J Neurosci Nurs. 1999;31(1):17‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Klerings I, Weinhandl AS, Thaler KJ. Information overload in healthcare: too much of a good thing? Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;109(4–5):285‐290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Synnot AJ, Hill SJ, Garner KA, et al. Online health information seeking: how people with multiple sclerosis find, assess and integrate treatment information to manage their health. Health Expect. 2016;19(3):727‐737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Gheihman G, Johnson M, Simpkin AL. Twelve tips for thriving in the face of clinical uncertainty. Med Teach. 2019;42:493‐499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Krupp LB, Serafin DJ, Christodoulou C. Multiple sclerosis‐associated fatigue. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(9):1437‐1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Schiavolin S, Leonardi M, Giovannetti AM, et al. Factors related to difficulties with employment in patients with multiple sclerosis: a review of 2002–2011 literature. Int J Rehabil Res. 2013;36(2):105‐111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Marziniak M, Brichetto G, Feys P, Meyding‐Lamadé U, Vernon K, Meuth SG. The use of digital and remote communication technologies as a tool for multiple sclerosis management: narrative review. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2018;5(1):e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Jongen PJ, Sinnige L, van Geel B, et al. The interactive web‐based program MSmonitor for self‐management and multidisciplinary care in multiple sclerosis: concept, content, and pilot results. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1741‐1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Pulman A, Thomas P, Jiang N, Dogan H, Pretty K. Developing a FACETS digital Toolkit, in MS Frontiers 2019. Bath, UK; 2019. http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/32492/ February 11, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 92. National Institute of Health Research . What is public involvement in research? 2019. https://www.invo.org.uk/find‐out‐more/what‐is‐public‐involvement‐in‐research‐2/. Accessed December 5, 2019

- 93. Van Kessel K, Babbage DR, Reay N, Miner‐Williams WM, Kersten P. Mobile technology use by people experiencing multiple sclerosis fatigue: survey methodology. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2017;5(2):e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Apolinario‐Hagen J, Menzel M, Hennemann S, Salewski C. Acceptance of mobile health apps for disease management among people with multiple sclerosis: web‐based survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;2(2):e11977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Thomas S, Pulman A, Thomas P, et al. Digitizing a face‐to‐face group fatigue management program: exploring the views of people with multiple sclerosis and health care professionals via consultation groups and interviews. JMIR Form Res. 2019;3(2):e10951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Gerardi C, Bertele' V, Rossi S, Garattini S, Banzi R. Preapproval and postapproval evidence on drugs for multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2018;90(21):964‐973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Gehr S, Kaiser T, Kreutz R, Ludwig W‐D, Paul F. Suggestions for improving the design of clinical trials in multiple sclerosis – results of a systematic analysis of completed phase III trials. EPMA J. 2019;10(4):425‐436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Joanna Briggs Institute . The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. Adelaide, SA: University of Adelaide; 2015https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/ReviewersManuals/Scoping‐.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 99. Kingsley C, Patel S. Patient‐reported outcome measures and patient‐reported experience measures. BJA Educ. 2017;17(4):137‐144. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Asano M, Hawken K, Turpin M, Eitzen A, Finlayson M. The lived experience of multiple sclerosis relapse: how adults with multiple sclerosis processed their relapse experience and evaluated their need for postrelapse care. Mult Scler Int. 2015;2015:351416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Riazi A, Bradshaw SA, Playford E. Quality of life in the care home: a qualitative study of the perspectives of residents with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(24):2095‐2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Willson CL, Tetley J, Lloyd C, Messmer Uccelli M, MacKian S. The impact of multiple sclerosis on the identity of mothers in Italy. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(12):1456‐1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Dlugonski D, Joyce RJ, Motl RW. Meanings, motivations, and strategies for engaging in physical activity among women with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(25):2148‐2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Hunt L, Nikopoulou‐Smyrni P, Reynolds F. ‘It gave me something big in my life to wonder and think about which took over the space … and not MS’: managing well‐being in multiple sclerosis through art‐making. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(14):1139‐1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors: the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supporting Information files).