Abstract

The purpose of this review is to highlight the pharmacological barrier to drug development for traumatic brain injury (TBI) and to discuss best practice strategies to overcome such barriers. Specifically, this article will review the pharmacological considerations of moving from the disease target “hit” to the “lead” compound with drug-like and central nervous system (CNS) penetrant properties. In vitro assessment of drug-like properties will be detailed, followed by pre-clinical studies to ensure adequate pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of response. The importance of biomarker development and utilization in both pre-clinical and clinical studies will be detailed, along with the importance of identifying diagnostic, pharmacodynamic/response, and prognostic biomarkers of injury type or severity, drug target engagement, and disease progression. This review will detail the important considerations in determining in vivo pre-clinical dose selection, as well as cross-species and human equivalent dose selection. Specific use of allometric scaling, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic criteria, as well as incorporation of biomarker assessments in human dose selection for clinical trial design will also be discussed. The overarching goal of this review is to detail the pharmacological considerations in the drug development process as a method to improve both pre-clinical and clinical study design as we evaluate novel therapies to improve outcomes in patients with TBI.

Keywords: biomarker, drug development, pharmacokinetics, pharmacology, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

The global goal of drug research is to translate discovery efforts into meaningful new therapeutic interventions. The pursuit of successful translation fuels both academic research and the pharmaceutical industry pipeline with the common goal of discovering novel therapeutics. Significant efforts have been made to advance discovery in academic and industrial settings and to forge partnerships between both entities.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiatives through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences has promoted collaborative industry partnership grants to evaluate drug repurposing and drug discovery. Specifically, within the neurosciences, the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke has developed both the Innovation Grants to Nurture Initial Translational Efforts and Cooperative Research to Enable and Advance Translational Enterprises for Biologics to advance novel small and large molecule discovery and development, respectively. Such efforts aim to catalyze support for drug discovery and development across the complexities of the academic and industrial settings to improve human health.

The challenges of successful drug development across the academic and industrial settings have been well described previously in numerous review articles.1–4 The challenges of successful drug development for central nervous system (CNS) indications are complicated further by the need to achieve adequate drug concentrations in the brain. Putative therapeutic agents should be amenable to systemic delivery and should be able to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB).

The progression of drug discovery from disease target discovery, to identification and selection of candidates for in vivo testing, to pre-clinical efficacy/toxicity evaluation of those agents, and finally to evaluate first in man studies has been coined the “valley of death.” Previous reviews have highlighted the need for reduction in cultural difference between academia and industry, education of scientists with the skills for translation, provision of resources to academia for translational intellectual property across collaborative entities.4 The aforementioned academic/NIH/industry efforts have been aimed at overcoming these challenges.

Therapies for traumatic brain injury (TBI) have had a poor translational success record with no treatment, pharmacological or otherwise, demonstrating improved outcomes in Phase III clinical trials. Multiple factors have been attributed to these failures including the intrinsic heterogeneity of the TBI patient population, trial design factors, the need for new validated targets, the insensitivity of outcome measures, and suboptimal dosing to achieve neuroprotection.5 In particular, dose selection and duration of treatment have been implicated as a potential reason for polyethylene glycol-superoxide dismutase, progesterone, and tirilazad clinical trial failures.1,6,7

The purpose of this current review is to detail the important pharmacological considerations that must be incorporated into drug discovery and development, as well as clinical trial considerations to minimize the risk of new agent failures. This review will suggest optimal strategies in new drug development and clinical dosage selection to improve translational success in future TBI patient clinical trials.

Getting from a Validated Disease Target to an Identified Lead Compound

The initial step in drug development is disease target identification and validation. Approaches for target identification and validation include an array of approaches that range from traditional molecular biology, genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic discovery, to generation of transgenic animals to evaluate the relevance of the target to the disease phenotype.8,9 A key consideration for putative CNS acting therapeutics is the ability to cross the BBB. Biological agents typically cannot readily cross the BBB because of their size and physicochemical properties. Search for approaches/methodologies that allow the CNS delivery of biological agents is ongoing; however, given the difficulty of the task, such efforts have yet to yield a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved biological agent that can cross the BBB.10,11

Greater success has been achieved in development of small molecules that cross the BBB. Several FDA approved drugs with CNS indications are small molecules with the appropriate physiochemical properties to cross the BBB. It has been estimated, however, that 98% of small molecules cannot cross the BBB.10 In the absence of active transport, small molecule therapeutics cross the BBB via passive diffusion and must have appropriate physicochemical properties to cross successfully.

For instance, the molecular weight for a compound should be below 450. The polar surface area—that is the sum of the surface area of their polar atoms—ideally should be less than 70 A2. The number of rotatable bonds and a host of other properties should all be within specific and relatively narrow value ranges.12 These requirements have implications for small molecule drug design of newly discovered CNS targets. The low molecular weight and overall narrow physicochemical property characteristics required for passive CNS penetration suggest that some small molecules may not be suitable for CNS targets that can only be modulated via direct disruption of protein-protein interactions occurring through shallow pockets and/or a large protein surface.13

Aside from target suitability, a key consideration for small molecule CNS drug discovery is the availability and identification of a compound as a hit/lead for development. In general, hits/leads can modulate the target of interest in vitro and/or in vivo. Compounds often do not have the desired therapeutic product profile (TPP) needed for the therapeutic indication, but their properties suggest that there is a possibility of achieving the TPP on chemical modification and optimization.

Hit/lead compound identification can be completed by a number of strategies, including high throughput screening,8,9 fragment-based screening, or computer aided methods, such as virtual screening. The generation of three-dimensional pharmacophore models based on common structure elements of known target modulators followed by computational evaluation of novel structural elements of the pharmacophore and scaffold hopping are additional approaches.9,14

Lead Compound Optimization and In Vivo Testing: First Time in Rat Studies

The next step after hit/lead identification is the compound optimization to incorporate the drug-like characteristics suitable for further development and for animal in vivo testing. This process is multi-parametrical and involves iterative steps of chemical modifications on the hit/lead structure. These derivatives are then tested to assess whether the modifications resulted in compounds that approach the desired TPP in terms of potency, selectivity, pharmacokinetics (PK), route of administration, acceptable toxicity, and in vivo efficacy.8,9

During hit/lead optimization, choices of derivative synthesis are informed by biochemical assays that measure binding/selectivity for the target of interest, cellular assays that measure functional activity, and by several other parallel assays that test pharmaceutical characteristics (aqueous solubility, stability, permeability), ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion), and toxicity of compounds. The complete battery of available assays is not employed against every derivative produced because this can be highly demanding to available resources. Instead, lead optimization efforts use a gateway approach where compounds that meet certain key TPP characteristics are tested in low resource utilization assays, such as activity and selectivity, to advance further to “higher order” assays such as cytochrome P450 (CYP) metabolic stability, hERG channel inhibition, in vivo PK and/or efficacy.

Evaluation of metabolic stability from CYP-based metabolism is an important assay that is used routinely during hit/lead optimization. Screening of hits/leads as substrates for other non-CYP metabolic enzymes and as transporter substrates are also evaluated. This testing allows for the selection of agents with the greatest potential for better in vivo PK characteristics and increased likelihood of BBB penetration. Typically, human liver microsomes, rat liver microsomes, and recombinant individual CYP isoform expression systems can be used to estimate the degree to which a given compound is metabolized and the identification of the specific isoforms involved in the metabolism. Use of nuclear magnetic resonance and full-scan mass spectrometry are used to identify the site of metabolism for subsequent structural modifications to improve metabolic stability and increased in vivo half-life.

During CYP metabolism studies, compounds are compared with prototypical known drugs such as verapamil, metoprolol, and warfarin that have high, medium, and low hepatic extraction in vitro and in vivo. To evaluate BBB permeability potential and transporter efflux, experiments with Madin-Darby Canine Kidney cell monolayers with overexpression of individual transporters are often evaluated. After lead compounds are identified, the degree to which a given lead compound may have drug-drug interaction potential in vivo is evaluated.

Evaluation of CYP inhibition and induction, as well as, transporter inhibition may be conducted.15–18 Hepatocyte cultures along with supportive in vitro transactivation of nuclear hormone receptor pathways (PXR, CAR, and others) are employed to assess induction potential for both metabolism and transport pathways, whereas the inhibition potential is most frequently evaluated in microsomal systems.

The FDA provides detailed guidance on each of the accepted methods for in vitro metabolism and transporter mediated drug-drug interaction studies (https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM581965.pdf). Incorporating such assays early in optimization decision trees generally is advantageous for identification of problematic hit/lead series sooner rather than later.

Biomarkers are an essential part of every stage of drug development and represent an emerging area of research within TBI. It is of note that the FDA and the NIH formed a working group to develop the BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools) resource to define and clarify research efforts in biomarker discovery and validation. The resource provides detailed descriptions of seven categories of biomarkers, which include diagnostic, monitoring, pharmacodynamic (PD)/response, predictive, prognostic, safety, and susceptibility/risk biomarkers.

Recent studies by the Operation Brain Trauma Therapy (OBTT) multi-center pre-clinical TBI consortium evaluated and proposed novel blood-based biomarkers.19 Specifically, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) blood levels are indicative of glial injury in the cortical contusion TBI rat model20 with potential for future clinical validation.21,22 The pre-clinical OBTT studies also demonstrated that axon specific phosphoneurofilament-heavy protein in the serum is indicative of traumatic axonal injury across different animal models of TBI.23 Recently, the FDA granted marketing authorization to Banyan Biomarkers for the use of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 and GFAP as the first diagnostic blood test for TBI as a marker to determine the need for computed tomography scans among patients with the clinical indication.24

In addition to diagnostic biomarkers, identification of biomarkers of direct drug target engagement, also known as PD/response biomarkers, are essential for pre-clinical and clinical drug development. The approach to identify biomarkers of target engagement differs based on whether the target is an enzyme or a receptor. If inhibition of an enzyme's activity is targeted, then the product/metabolite of that pathway can be assessed to ensure that the compound is reducing the formation after in vivo administration to an animal model.25,26

Concurrent studies to evaluate the associations between PD/response biomarkers, prognostic biomarkers, and TBI outcome measures will provide important evidence that a given pathway is a target for therapeutic intervention and can be used to guide drug dosing estimations during clinical translation for first-time-in-human studies. Evaluation of target engagement for an agonist or antagonist of a given receptor has unique challenges in vivo. If there are known downstream signal transduction pathways and/or pathways of reactive oxygen species development that can be assessed in vivo, then these metabolites can be assessed as a surrogate of PD/response.

Alternatively, and ideally, if a known selective positron emission tomography (PET) ligand or other brain imaging biomarker method exists for a given target, then the use of imaging methods would provide an ideal method for translation from pre-clinical to early stage clinical studies. The PET ligands have the additional advantage of assessment of the percent of receptor occupancy (RO). Use of such imaging methods for target engagement has been evaluated in other CNS disorders.27 The collective use of diagnostic, PD/response, and prognostic biomarkers across species will provide multiple indices to guide drug dose/duration selection, as well as the potential personalization of future drug interventions.

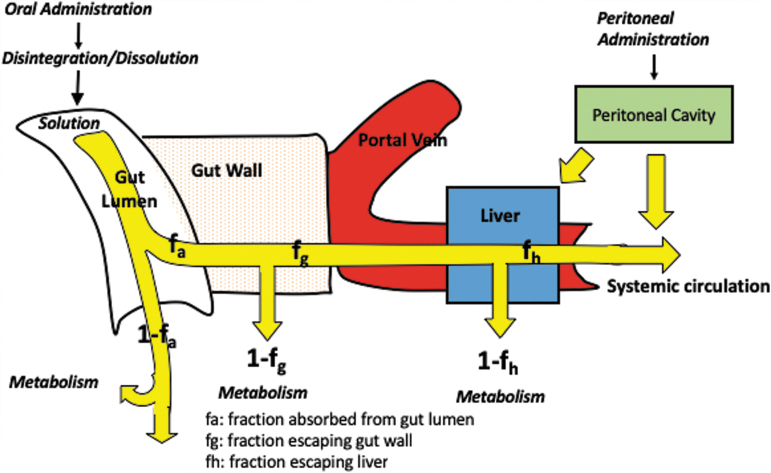

Once lead compounds are identified, they are advanced for pre-clinical rodent in vivo PK assessment of plasma and tissue concentrations. The route of administration should be considered carefully and should reflect the intended TPP during this stage of pre-clinical development. The oral route has a number of hurdles that a drug candidate has to cross before it reaches the site of action and is often least desired for critically ill patients. Hence, the intraperitoneal (IP) route is often chosen where a molecule does not have to overcome the challenge of gastric acid stability and gut wall permeability. The IP route of administration, however, does have the barrier of peritoneal absorption with some first pass liver metabolism that is not a barrier after intravenous (IV) administration (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Barriers encountered by orally and intraperitoneally administered molecules before reaching the systemic circulation. Color image is available online.

An example of this issue within TBI research the pre-clinical minocycline. Pre-clinical PK studies by Fagan and associates28 demonstrate in the rat model that 90 mg/kg of minocycline IP are required to generate a comparable area under the plasma concentration versus time curve is evaluation of (AUC) is as 45 mg/kg IV. More importantly, the IP absorption of minocycline is highly variable compared with IV administration, thereby, precluding the use of the IP route in pre-clinical in vivo assessment.

In the clinical setting, the IP route of administration is not relevant for TBI drug development.28 The IP route of administration may be acceptable, however, for early in vivo proof of concept studies when the drug has adequate and complete absorption after IP administration with low PK variability. Initial PK suites to evaluate the extent and variability of absorption should be conducted to determine the appropriateness of the IP route before embarking on pre-clinical injury model outcomes.

If PK characteristics are known, if adequate concentration at the effect site can be achieved, and if target engagement and prognostic biomarkers are established, then there is an opportunity to conduct PK-PD–efficacy evaluations. Murine studies that establish the relationship between drug concentration to target engagement biomarker in the brain, and ideally in the systemic circulation, can be used for subsequent dose finding in larger animals, as well as first-time-in-human studies. Further, use of systemic biomarkers, drug concentrations required for modulation of these biomarkers, and meaningful measures of neurological injury to assess effects of a given new drug will allow for better translation of drugs from rat to man through the identification of the human equivalent dose.

From Rat to Man: Human Equivalent Dose Identification

Estimating dose across species, mg/kg versus mg/body surface area (BSA) determinations: FDA guidance

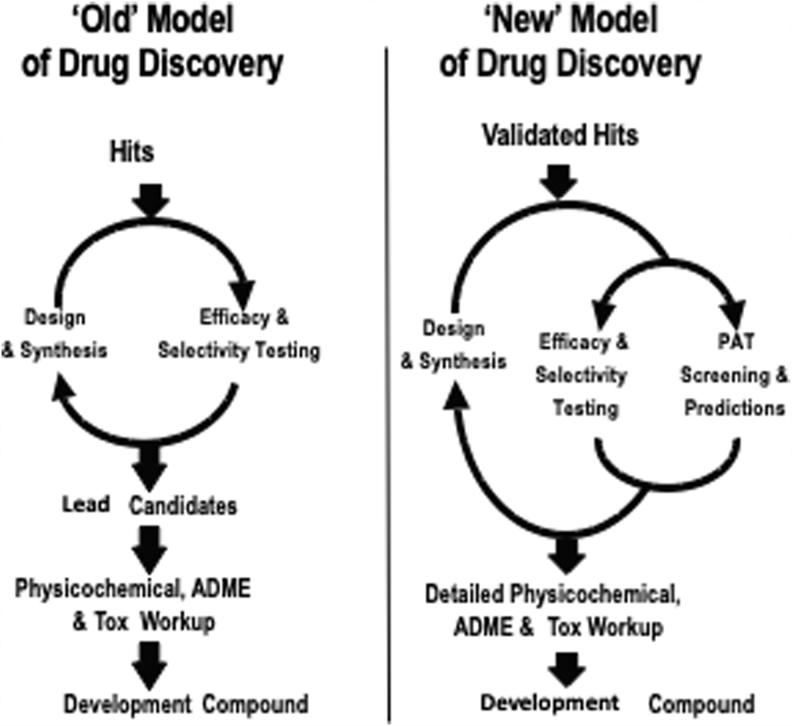

To increase the probability of success in clinical trials, the pharmaceutical industry has adopted several in vitro and in vivo assays to assess the drug-like characteristics of new candidate compounds.29 As discussed previously, these assays test pharmaceutics (aqueous solubility, stability, permeability), ADME, and toxicological characteristics of drug candidates. This iterative process identifies drug candidates for detailed physicochemical, ADME, and toxicology evaluation before advancing the candidate for first in human studies (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Models of drug discovery and development. ADME, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion; Tox, toxicology.

In vivo pharmacological evaluation relies on rodent efficacy models that capture some aspect of the human disease pathophysiology. A molecule is dosed in vivo in rodents to evaluate if the in vitro potency will translate to in vivo efficacy. If the molecule is not optimized for solubility, permeability, and metabolic stability, however, the administered dose may not reach the brain in sufficient concentrations. Often a pharmacologist will pick doses that increase in half log magnitude (e.g. 10, 30, 100 mg/kg) with the hope that a dose-pharmacological response relationship will be seen without toxicity that may compromise efficacy. If all works well and the 30 mg/kg dose shows efficacy based on pre-determined criteria, it is projected that a comparable dose will work in patients.

A 30 mg/kg dose in rats will scale to 2.1 g dose in a 70 kg individual. It is unlikely that this high dose will be delivered in a solid dosage form to achieve sufficient pharmacological activity. Fortunately, for small molecules, the dose often scales based on BSA and not body weight. Based on BSA conversion, a 30 mg/kg dose in the rat will translate to approximately 300 mg dose in patients, which is far more amenable to be developed as a human administered dose.

The FDA and other regulatory agencies have provided guidance for first-in-human dosing based on BSA conversion of the no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) in the most sensitive species and further applying a safety factor for the starting dose selection. www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM078932.pdf%23search=%27guidekines+for+industry+sfe+starting%27. The guidance recommends that the process of calculating the maximum recommended starting dose should begin after the NOAEL has been identified in each safety species.

The BSA normalization and extrapolation of the animal dose to human dose should be done by dividing the NOAEL in each animal species studied by the appropriate BSA-conversion factor. This is a unitless number that converts mg/kg dose for each animal species to the mg/kg dose in humans, which is equivalent to the NOAEL of the animal on mg/m2 basis. The resulting number is called the human equivalent dose (HED).

A safety factor is then applied to the HED to increase assurance that the first dose in humans will not cause adverse effects. For example, assuming the above-mentioned molecule that is efficacious at 30 mg/kg shows no observed adverse effect at 100 mg/kg/day in chronic toxicity studies, a starting dose of 100 mg may be permissible with a safety factor of 10. The regulatory agencies are also likely to cap the maximum dose based on the observed toxicities and BSA-based dose conversion.

This approach offers a wider margin of safety when testing a new drug candidate for the first time in humans. Yet this approach does not consider PK properties of new drug candidates. It is also of note that dosing of the small molecule levetiracetam is the exception because the HED scales more closely with body weight rather than BSA. While the BSA-based dose conversion typically is the standard practice for small molecules, there are specific exceptions for some small molecules and large therapeutic proteins, which typically scale based on body weight.30

Estimating dose versus targeting concentrations: Advantages of utilizing PK/PD estimates to identify dose

Drug discovery scientists have advanced beyond scaling doses from rodents to humans based on body weight or BSA-based conversion. It has now been well accepted that circulating plasma concentrations of drug compounds coupled with biomarker assessments are a much better surrogate of efficacy than the administered dose. Some targets that are being pursued in drug discovery today often require more sophisticated heterocyclic structure and are inherently more lipophilic, poorly soluble, and metabolically unstable.

Once leads are optimized in vitro, it is prudent to conduct single dose acute PK studies by the intended route of administration before embarking on chronic efficacy studies that require a lot more compound and human resources. It is also recommended that plasma and brain exposure be determined in the same strain of rats (or mice) and under identical conditions as those to be used in efficacy studies (e.g., matching the vehicle for dosing and fed vs. fasted condition). Despite these precautions, scientists are often surprised with the outcome in the efficacy studies. As such, the efficacy study protocol should incorporate measurement of selected concentrations from the study animals or from a group of satellite animals to guide future experimental design and define the therapeutic concentration window.

As described earlier, in vitro potency should translate to in vivo potency. Often, this is the case, and significant correlations between in vivo effective dose (ED)50 or effective concentration (EC)50 and in vitro potency have been established for a variety of therapeutic targets.31,32 When there is no correlation between in vivo and in vitro potency measures, however, the validity of the in vitro assay, the animal model, and the target may be questioned.

Establishing dose response and strong in vitro-to-in vivo relationships is a necessity for drug development. For compounds that have large pharmacokinetic variability, in vitro-to-in vivo correlations based on ED50 are unlikely. Instead, improved correlations may be obtained by using EC50 (based on plasma concentrations). For determining ECs, “free drug hypothesis” generally prevails. It assumes only the free (unbound; not plasma-protein bound) drug is available to modulate the target. Even for intracellular targets, where drug access is not limited by passive permeability, efflux, or active uptake; free plasma exposure is a good surrogate of efficacy.

For more complex targets, one has to go beyond plasma exposure to assess feasibility of drug action. For example, plasma exposure will not guarantee exposure in “difficult-to-reach” targets such as the brain. There has been important progress in the development of anticancer therapeutics, including molecularly targeted agents and novel immunotherapies.33 While these modalities are clearly efficacious toward tumors at the primary site, to deliver these therapeutics across the BBB remains a challenge.

The capillaries and associated cellular components in the brain that make up the BBB keep many solutes, especially water-soluble solutes and large molecules, out of the brain. The tight junctions between the endothelial cells in the BBB in conjunction with multiple transport systems, both influx and efflux, regulate selective movement of molecules across the BBB into the brain. Specifically, many small molecule anticancer targeted agents have been shown to be substrates of active efflux transporters at the BBB, resulting in limited brain penetration of such therapies.

It is a common practice to measure brain concentrations in rodent models for centrally acting drug candidates. Total brain concentrations, however, are also not indicative of the active brain concentrations. In the absence of active transport (both in and out of the brain), unbound (not plasma protein bound) drug concentrations can serve as a surrogate of active brain concentrations. For drugs that are substrates for active transport, however, unbound plasma concentrations are not a good indicator of active brain concentrations. In such circumstances, measuring unbound brain concentrations provides the closest link to efficacy.34

For central targets, this EC50 relates to brain concentrations and, as shown by Kalvass and coworkers,34 it is obtained by PK/PD modeling of free brain concentrations and in vivo efficacy. One method for estimating CNS biophase concentrations is simply to multiply total brain concentrations by brain unbound fraction (fu,brain). Kalvass and colleagues34 showed that the brain EC50 is the best in vivo measure of CNS intrinsic potency for seven μ-opioid agonists. These drugs were selected as probe CNS drugs on the basis of having pronounced differences in potency toward the μ-opioid receptor, differing physiochemical properties (i.e., lipophilicity, unbound fractions, and permeability), and differing extent of CNS distribution. The PK/PD studies were conducted in mice to determine five measures of in vivo potency (ED50; total and unbound EC50 for both serum and brain) for each opioid. The most useful measure of in vivo potency was determined by correlation analysis with the in vitro and clinical potency data. The strongest in vitro-to-in vivo correlation was observed between Ki and unbound brain EC50,u (r2 ∼ 0.8).

The brain vasculature also contains several other transporters, including uptake transporters that ferry the drug across the barrier to the brain parenchyma. Limited studies have reported the role of uptake transporters in transporting drugs across the BBB.35 Comparison across human organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs) and rodent Oatps has indicated that there exists similar tissue localization for both. The presence of Oatps in the blood-spinal cord barrier (BSCB) is not widely reported, although it has been shown that the efflux transporter (P-gp) localization is similar between the BBB and BSCB.

The study of BSCB transporters becomes important when the site of drug action specifically resides in the spinal cord (e.g., certain pain disorders). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations have been used occasionally as a surrogate for active brain concentrations, yet this may lead to poor correlation between concentrations and efficacy because of the presence of active transport in the brain-CSF barrier (BCSFB). Some reports suggest that the P-gp is localized on the BCSFB, but the orientation of the efflux transporter may enable the transport from the blood to the CSF instead of effluxing drugs out of the CSF.36,37

Approaches to inhibit BBB efflux transporter activity to increase concentrations of drugs in the brain have been evaluated in pre-clinical and clinical studies. Although there is substrate overlap between rodents and human OATP/Oatps, transporter function shows significant species differences in capacity. Many Oatp substrates show overlapping substrate specificity for P-gp and other efflux transporters, such as breast cancer resistance protein or multi-drug resistance–associated proteins.

Digoxin is a widely used P-gp substrate in in vitro as well as in vivo pre-clinical and clinical studies, and its disposition is influenced by P-gp modulation across various membranes. Digoxin brain penetration increases ∼4 to 10 fold when P-gp activity is inhibited either by chemical inhibition or by P-gp gene knockout in pre-clinical species.38,39

Similar approaches have been taken to increase antioxidants in the brain through efflux transport inhibition. Specifically, studies have evaluated the repurposing of the OAT inhibitor, probenecid, to increase n-acetylcysteine (NAC) concentrations in the brain after TBI. A study in juvenile rats demonstrated that probenecid increased plasma NAC exposure and also produced a greater increase in the brain NAC concentrations, thereby, implicating reduced OAT efflux at the BBB.40 The translational importance of BBB modulation by probenecid on NAC was also evaluated in a phase I study of pediatric patients with severe TBI. Combination treatment resulted in measurable CSF NAC and probenecid concentrations and was not associated with undesirable effects in children.41

The clearance of drugs by metabolism in the brain tissue or endothelia and distribution by bulk flow are considered to be negligible for most drugs.42 Hence, the interplay between passive diffusion, uptake transporters, and efflux transporters determines the passage of a drug across the BBB. The presence of highly competent efflux transport renders the uptake transport and passive diffusion insignificant, and hence a drug like digoxin and NAC exhibit poor permeability across the brain. The brain uptake for drugs like digoxin and NAC can be increased by drugs capable of inhibiting the specific transporters involved in BBB efflux.

Establishing adequate systemic concentrations is important for efficacy; yet a common question faced in drug discovery is which PK parameter drives efficacy. For competitive antagonists, duration of target coverage could be important. A conservative goal may be to maintain the plasma concentrations above the in vitro inhibitory concentration (IC)50 (or IC90) for the entire dosing interval in a chronic dosing regimen. Drug discovery scientists should test this hypothesis before advancing a new drug candidate to clinical trials.

Once robust in vitro potency assays and a reliable efficacy model are established, scientists should test multiple molecules with varying potency and PK properties. By varying the maximum concentration, minimum concentration (Cmin) and AUC, the scientists can determine which PK parameter drives efficacy.

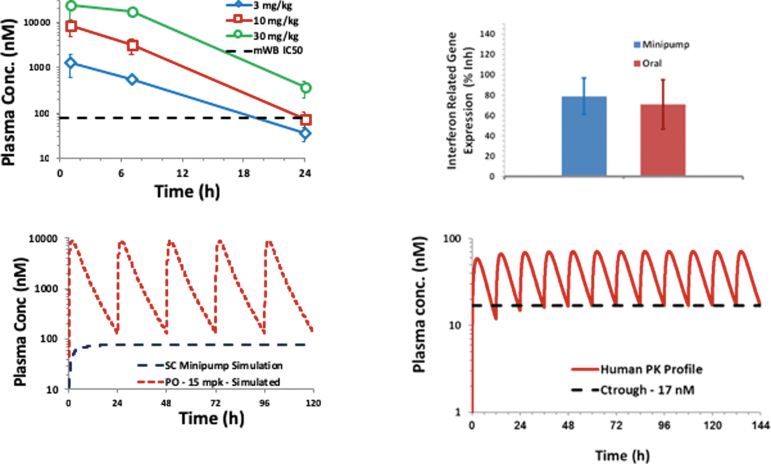

An illustrative example of finding which PK parameter drives efficacy is shown in Figure 3. Single daily doses of 10 and 30 mg/kg/day of a new drug candidate provided robust efficacy. At these doses, plasma drug concentrations were 1X and 5X above the in vitro IC50. Interferon-induced genes were measured as a PD biomarker because they correlated with efficacy and drug concentrations at trough in multiple studies. The drug candidate was then administered as a subcutaneous infusion via Alzet minipumps to maintain the plasma concentrations at 1X IC50. The subcutaneous infusion was equally efficacious as the once daily drug regimen. Based on these data, human efficacious doses were projected (7 mg twice daily) to maintain Cmin concentrations at 1X human IC50.

FIG. 3.

Use of pharmacokinetic (PK) parameter assessment to evaluate drug efficacy. Color image is available online.

Importance of multi-species assessment for both rigor of efficacy and PK determinations

Modern drug discovery often relies on PK optimization in multiple species. Earlier in a discovery program, it is common to test promising compounds in the rodent model of efficacy. Once robust efficacy is established and molecules with drug-like properties emerge, they are advanced into large animal PK studies. Composite PK analysis from multiple species enables prediction of human PK.43

It is important to recognize that not all species will behave similarly. For example, it is possible to see decent oral bioavailability in the rat and dog, yet poor oral bioavailability in the monkey.44 Sometimes, the terminal half-life in the dog may be much longer than other species. When such disconnects are observed, it becomes difficult to predict which species will resemble human. A reasonable effort may be spent in understanding these inter-species differences. For example, the low oral bioavailability in the monkey may be attributed to extensive gut first pass effect,45 and the long half-life in the dog may be attributed to extremely low clearance because of poor metabolic turnover.

In addition, the juvenile piglet has been utilized as a more acceptable brain injury model system for pediatric TBI studies. The ontogeny of CYP metabolism in the piglet has been largely understudied. A recent study by Millecam and associates46 evaluated the ontogeny of several CYP isoforms during development and demonstrated similarities with expression in human development. This study suggests that the juvenile piglet may serve as an appropriate model for multi-species drug development depending on the specific CYP isoform involved in drug elimination.48

Prediction of human PK is highly uncertain when the mechanism behind interspecies differences is not understood. No one species behaves similar to human in all aspects of drug disposition. When such uncertainty exists, the scientists should leverage in vitro human-based assays to ensure the new drug candidate has favorable drug-like properties—such as good metabolic stability, good permeability, no drug-drug interaction liabilities—before advancing them to the clinic. This emphasizes the need to test the new drug candidates in human in vitro systems (e.g., human liver microsomes for metabolic stability, Caco2 cells for permeability) in addition to the evaluation of interspecies differences to guide human equivalent dosing.

An opportunity for ADME scientists lies in pharmacologists working with biologists to integrate PK-PD optimization with a quantitative mindset to assess the efficacy in animal models. Translational biomarkers become critical when trying to extrapolate disease modulation in rodents to human. If a large animal species is thought to be more relevant to human disease, it is imperative to establish PK-PD relationship in that species and to provide greater confidence that the relationship will hold in human.

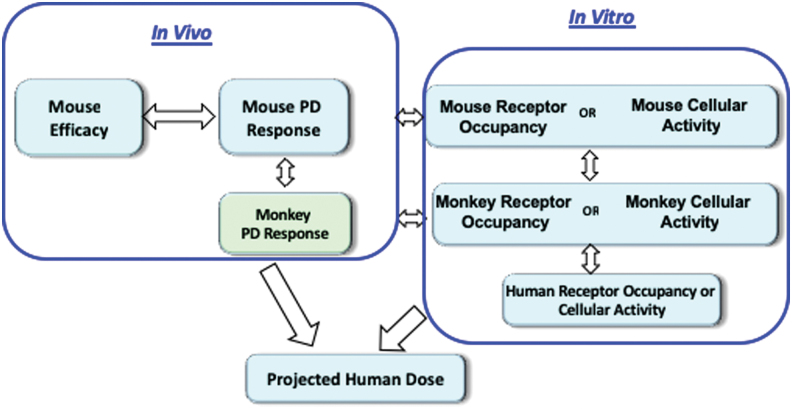

The PD biomarker assays in human plasma will facilitate expeditious clinical testing. An example of integrating target engagement as measured by receptor occupancy, PD biomarker and efficacy are shown in Figure 4. In vitro cellular potency in the mouse and monkey is translated to in vivo PD response in the respective species. In vivo PD response in the mouse is translated to disease modulation to establish the required PD response. Human efficacious dose is then projected that will target the desired PD response based on the in vitro potency in human and projected human PK.

FIG. 4.

Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic framework for projecting human efficacious doses. Color image is available online.

Many drugs form pharmacologically active metabolites. Drug discovery scientists should profile plasma obtained from animals used in efficacy studies and determine presence of metabolites. Major circulating metabolites in efficacy species should be synthesized and tested for pharmacological activity. Metabolism studies using in vitro systems should evaluate whether an active metabolite is formed in vitro, in the animal efficacy model, and in humans.

A correlation of the active metabolite formed in vitro and in vivo in the efficacy model should be established to gauge the importance of human in vitro systems for formation of the putative active metabolite. In vitro potency of the metabolite and its circulating concentrations will allow understanding of its contribution to the pharmacological activity in the animal species. If the formation of this active metabolite is minor in human in vitro systems; there will be additional uncertainty in translating the efficacious dose between species. Prediction of human dose typically assumes that the pharmacological activity is only from the parent drug molecule without the more complex contribution from an active circulating metabolite.47,48

Apart from PK assessment in the efficacy species, it is equally important to ensure good PK properties leading to good systemic exposure in the species used for safety assessment. For small molecules, it is recommended to have two species (one rodent and one non-rodent) for safety assessment. Rat is the most commonly used rodent safety species. The choice of non-rodent species is based on pharmacological activity, ability to escalate exposures several fold above the “efficacious exposure,” appropriateness for TBI research assessment, and similarity in metabolic profile relative to human. Demonstration of robust PD activity along with multiples of systemic exposure in safety evaluation studies is highly desirable. This will ensure that the toxicological species is relevant to assess suprapharmacological activity and thus both on- and off-target effects.

Is allometrical scaling the ideal method for human drug dose determination?

So far we have discussed the importance of PK optimization in animal species for both efficacy and safety evaluation. Ultimately, the goal is to advance the new drug candidate to humans for safety and efficacy evaluation. How does one project human PK based on animals? Allometrical scaling is a commonly used method for prediction of human PK.49 The PK profile is governed by two primary parameters—clearance (CL) and volume of distribution (Vd). Clearance measures how efficiently the drug is eliminated from the body while Vd determines the distribution of the drug molecule throughout the body.

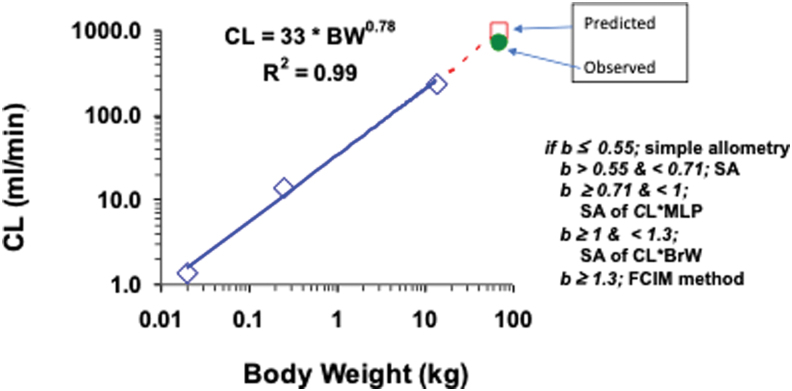

Many physiological processes (e.g., blood flow) scale based on body weight. The CL, which has the units of flow, can also be scaled by body weight (Fig. 5). As discussed earlier, if the PK parameter that drives efficacy is the plasma AUC, CL becomes the most important parameter that drives AUC (AUC = Dose/CL).

FIG. 5.

Allometric scaling of clearance (CL) based on body weight (BW) across species. Color image is available online.

It is now well established that simple allometry (simply based on body weight) is not adequate for prediction of CL because it requires correction factors to improve the prediction.50 The role of exponents was developed from real observations and behavior of the allometrical exponents. Simple allometry works best when the exponent is <0.71. Between 0.71 and 1.0, CL is multiplied by the maximum lifespan potential of each species; whereas for exponent >1.0, the best prediction is obtained by multiplication with brain weight. A case of vertical allometry is observed when the exponent exceeds 1.3 and adjustment by correction of free fraction between the rat and human is applied for allometrical scaling.51

Allometrical scaling is also used to predict Vd in humans; however, unlike CL, the typical exponent for Vd is 1.0. Significant deviation of the Vd exponent from unity is indicative of interspecies disconnect, and it creates uncertainty in the prediction of human Vd. Sometimes, the Vd exponent comes closer to 1.0 when a correction factor of plasma protein binding in each species is applied. While CL alone is sufficient to predict AUC, prediction of Vd is necessary to project plasma concentration versus time profile, thereby estimating the duration of target coverage at a given dose.

There are numerous examples of successful PK prediction by allometry, yet it is important to recognize that this method is strictly empirical in nature. It does not consider species differences in metabolism or any other disposition pathways (e.g., active transport across the liver or kidney) that may affect CL and Vd. A more mechanistical method to predict CL is to establish in vitro-in vivo correlation in CL.52

Many liver-based in vitro systems are available (e.g., microsomes, S9, cytosol, hepatocytes) for measuring metabolic turnover. Choice of the system depends on the metabolic characterization of the new drug candidate. For example, if the new drug candidate is metabolized largely by CYP enzymes, human liver microsomes is an ideal in vitro system. In vitro turnover is then scaled to in vitro CL and then to in vivo CL by incorporation of liver blood flow and protein binding. To increase the confidence in scaling in vitro CL in human liver microsomes to predict human in vivo CL; it is desirable to establish a correlation between in vitro and in vivo (IVIC) CL in one or more animal species. This method assumes that systemic CL is largely governed by the liver, however.

Beyond allometrical scaling and IVIVC, physiologically based methods (e.g., incorporation of active transport across the liver) are now being used for prediction of CL and Vd.53 Use of multiple approaches leading to convergence of CL and Vd predictions will provide additional confidence in human PK prediction. While regulatory guidance recommends first-in-human dose selection based on BSA-based dose conversion and observed toxicities, it also allows for an alternative approach that places primary emphasis on animal PK, biomarker assessment, and modeling rather than the dose.

There is a clear distinction between prediction of human PK and efficacious dose. While reliable PK prediction requires in depth understanding of disposition properties of the new drug candidate (e.g., metabolic pathways, renal elimination, protein binding, active transport), efficacious dose prediction requires in depth understanding of the animal models of disease and their translation to human disease. Specific evaluation of alterations in systemic and brain tissue concentrations in various TBI animal models will better determine the effects of BBB disruption and inflammatory alterations in CYP expression, which occur after injury.54,55

Ideally, the use of brain injury models that best represent the specific human type of brain injury for which the therapy is targeted, along with the corresponding biomarkers of that injury type, should be used to guide subsequent clinical translation. Approaches to model PK drug concentrations assessments with PD biomarkers of injury in pre-clinical studies will aid in the estimation of efficacious doses in humans compared with methods that rely primarily on dose response or dose body weight/BSA estimations.

Clinical Development Considerations

Once a drug candidate is nominated to proceed into the clinic, preparation is made for the first in-human studies. The majority of compounds will be tested first in healthy volunteers before studies in patients with TBI. A single dose escalation will be pursued before multiple dosing. The starting dose for a small molecule is based on toxicology studies with respect to the FDA first time in human guidance. The no effect dose determined in the most sensitive species is used for the initial dose determination, followed by a BSA safety correction factor to convert to a human-equivalent dose. A safety factor of 10 is applied to yield the starting dose. Exposure data in the toxicology studies can also be used with scaling to humans, in addition to BSA to determine a starting dose.

The predicted efficacious dose and exposure from toxicity studies are considered when the range of doses to be studied in the first in human trial is determined. Increases in doses often occur logarithmically at low doses and in lower increments at higher doses. Frequency of dosing in the multiple dose study will be determined based on PD understanding of the target determined pre-clinically, and actual PKs determined in the single-dose study.

If there is a way to determine pharmacological effect in healthy volunteers, biomarkers should be incorporated in the healthy volunteer and patient studies. Evaluating receptor binding in humans is useful, but the number of compartments that can be sampled in humans is very limited. Leveraging the animal and in vitro data to help design first time in human studies and assess target engagement increases the interpretability and likelihood of success. Also, ensuring that the drug is getting to the tissue of interest, such as the CNS, is key. Sampling of CSF may be useful, but imaging such as PET is preferred ideally.27

Recognizing the challenges of clinical trials, Morgan and coworkers56 have proposed three pillars for increasing probability of success in advancing drug candidates to Phase III trials. Pillar 1 asks questions about target exposure. Is there exposure at the target site in humans that meets desired levels based on pre-clinical animal studies or potency? Pillar 2 requires assurance of target engagement. Are there data from humans showing binding to pharmacological target in the target tissue that meets the pre-defined criteria? Pillar 3 goes one step beyond into target PDs. Are there data from humans showing the desired pharmacology in the target tissue that meet the pre-defined criteria?

Their retrospective analysis of 44 Phase II candidates revealed that a fundamental understanding of the PK/PD pillars of a drug was a determinant of Phase II success. With target exposure in relevant compartment, target binding, and expected PD effects, eight of 14 Phase II programs achieved Phase III starts. On the contrary, with only plasma exposure, without evidence of target binding, and poor understanding of PK-PD, not a single program (of 12) led to Phase III initiation. Not only were the majority of failures caused by lack of efficacy but also in 43% of cases, it was not possible to conclude whether the mechanism had been tested adequately.

This evaluation emphasized the importance of an integrated understanding of the fundamental PK-PD principles of exposure at the site of action, target binding, and expression of functional pharmacological activity. It is essential to conduct more thorough evaluations of PK/PD relationships detailed in these pillars of drug discovery. If TBI drug development continues without such data, then it is likely that we will continue to observe failure of clinical studies to improve outcomes before or on completion of Phase III clinical trials.

In the later stage clinical trials, duration of treatment becomes very important. Picking the optimal dosing regimen could avoid a trial failure, either for lack of efficacy if a drug is dosed too infrequently or unnecessary toxicity. Trials where the duration of therapy is not long enough could result in primary end-point failure. Last, many diseases progress over time, so measurement of a biomarker over time, with incorporation of placebo data, is often needed to assess adequately whether a treatment is effective in a given disease.

Another challenge in later stage clinical trials is the selection of the optimum primary end-points, with consideration of the high degree of heterogeneity that exists in the TBI patient population. Characterizing the variability in patients with TBI based on injury type and/or severity, seeking end-points that will minimize that variability, and working closely with statisticians to ensure optimal study size and design are keys for success.

Summary and Future Opportunities

Drug discovery and development for TBI has reached a critical juncture to advance new therapies aimed at improving patient outcomes. The renewed emphasis on both the discovery of biomarkers coupled with assessment of drug concentration/PD relationship relative to disease outcomes has the promise to advance the next generation of drug discovery. Pre-clinical evaluation of new compounds with drug-like properties, including likelihood of BBB penetration, is important in the early phase of drug discovery. Advancing the discovery of diagnostic biomarkers of injury type and severity is aimed to personalize therapy to move past the “one size fits all” approach to TBI research. The PK concentration assessments combined with PD/response biomarkers (target engagement and disease prognosis) can modeled to elucidate a novel drug's to therapeutic window.

It is critically important to ensure that PK/PD assessments begin in the pre-clinical phase and extend into clinical drug discovery and development. Dose scaling based on BSA alone is insufficient to ensure that adequate drug concentrations are achieved at the effect site of the targeted pathway to improve patient outcomes. Careful consideration of the route of administration based on intended clinical route rather than ease of use in pre-clinical studies will also aid in development and translation of new drug interventions.

Now is the time to continue the transition from the traditional “dose-response” relationship to the new era of “dose-concentration-biomarker-response” relationship. Full elucidation of these dynamic relationships in the pre-clinical phase will improve the likelihood of success of clinical translation. Collaborative interdisciplinary teams with expertise in neurotrauma, pharmacology, and drug discovery and development will be key in translating new drug discoveries into therapies that improve TBI patient outcomes.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Howard R.B., Sayeed I., and Stein D.G. (2017). Suboptimal dosing parameters as possible factors in the negative phase III clinical trials of progesterone for traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 34, 1915–1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gamo N.J., Birknow M.R., Sullivan D., Kondo M.A., Horiuchi Y., Sakurai T., Slusher B.S., and Sawa A. (2017). Valley of death: a proposal to build a “translational bridge” for the next generation. Neurosci. Res. 115, 1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hutson P.H., Clark J.A., and Cross A.J. (2017). CNS target identification and validation: avoiding the valley of death or naive optimism? Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 57, 171–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Finkbeiner S. (2010). Bridging the Valley of Death of therapeutics for neurodegeneration. Nature Med. 16, 1227–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maas A.I., Steyerberg E.W., Murray G.D., Bullock R., Baethmann A., Marshall L.F., and Teasdale G.M. (1999). Why have recent trials of neuroprotective agents in head injury failed to show convincing efficacy? A pragmatic analysis and theoretical considerations. Neurosurgery 44, 1286–1298 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sena E., Wheble P., Sandercock P., and Macleod M. (2007). Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of tirilazad in experimental stroke. Stroke 38, 388–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stein D.G. (2015). Embracing failure: What the Phase III progesterone studies can teach about TBI clinical trials. Brain Inj. 29, 1259–1272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roy A. (2018). Early probe and drug discovery in academia: a minireview. High Throughput 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hughes J.P., Rees S., Kalindjian S.B., and Philpott K.L. (2011). Principles of early drug discovery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 162, 1239–1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pardridge W.M. (2015). Targeted delivery of protein and gene medicines through the blood-brain barrier. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 97, 347–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yi X., Manickam D.S., Brynskikh A., and Kabanov A.V. (2014). Agile delivery of protein therapeutics to CNS. J. Control Release 190, 637–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pajouhesh H. and Lenz G.R. (2005). Medicinal chemical properties of successful central nervous system drugs. NeuroRx 2, 541–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blazer L.L. and Neubig R.R. (2009). Small molecule protein-protein interaction inhibitors as CNS therapeutic agents: current progress and future hurdles. Neuropsychopharmacology 34, 126–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sun H., Tawa G., and Wallqvist A. (2012). Classification of scaffold-hopping approaches. Drug Discov. Today 17, 310–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Einolf H.J., Chen L., Fahmi O.A., Gibson C.R., Obach R.S., Shebley M., Silva J., Sinz M.W., Unadkat J.D., Zhang L., and Zhao P. (2014). Evaluation of various static and dynamic modeling methods to predict clinical CYP3A induction using in vitro CYP3A4 mRNA induction data. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 95, 179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fahmi O.A. and Ripp S.L. (2010). Evaluation of models for predicting drug-drug interactions due to induction. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 6, 1399–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Agarwal S., Arya V., and Zhang L. (2013). Review of P-gp inhibition data in recently approved new drug applications: utility of the proposed [I(1) ]/IC(50) and [I(2) ]/IC(50) criteria in the P-gp decision tree. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 53, 228–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bjornsson T.D., Callaghan J.T., Einolf H.J., Fischer V., Gan L., Grimm S., Kao J., King S.P., Miwa G., Ni L., Kumar G., McLeod J., Obach R.S., Roberts S., Roe A., Shah A., Snikeris F., Sullivan J.T., Tweedie D., Vega J.M., Walsh J., Wrighton S.A., Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) Drug Metabolism/Clinical Pharmacology Technical Working Group; FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). (2003). The conduct of in vitro and in vivo drug-drug interaction studies: a Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) perspective. Drug Metab. Dispos. 31, 815–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kochanek P.M., Dixon C.E., Mondello S., Wang K.K., Lafrenaye A., Bramlett H.M., Dietrich W.D., Hayes R.L., Shear D.A., Gilsdorf J.S., Catania M., Poloyac S.M., Empey P.E., Jackson T.C., and Povlishock J.T. (2018). Multi-center pre-clinical consortia to enhance translation of therapies and biomarkers for traumatic brain injury: Operation Brain Trauma Therapy and beyond. Front. Neurol. 9, 640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Browning M., Shear D.A., Bramlett H.M., Dixon C.E., Mondello S., Schmid K.E., Poloyac S.M., Dietrich W.D., Hayes R.L., Wang K.K., Povlishock J.T., Tortella F.C., and Kochanek P.M. (2016). Levetiracetam treatment in traumatic brain injury: Operation Brain Trauma Therapy. J. Neurotrauma 33, 581–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McMahon P.J., Panczykowski D.M., Yue J.K., Puccio A.M., Inoue T., Sorani M.D., Lingsma H.F., Maas A.I., Valadka A.B., Yuh E.L., Mukherjee P., Manley G.T., Okonkwo D.O., and TRACK-TBI Investigators. (2015). Measurement of the glial fibrillary acidic protein and its breakdown products GFAP-BDP biomarker for the detection of traumatic brain injury compared to computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurotrauma 32, 527–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Diaz-Arrastia R., Wang K.K., Papa L., Sorani M.D., Yue J.K., Puccio A.M., McMahon P.J., Inoue T., Yuh E.L., Lingsma H.F., Maas A.I., Valadka A.B., Okonkwo D.O., Manley G.T.; TRACK TBI Investigators. (2014). Acute biomarkers of traumatic brain injury: relationship between plasma levels of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 and glial fibrillary acidic protein. J. Neurotrauma 31, 19–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang Z., Zhu T., Mondello S., Akel M., Wong A.T., Kothari I.M., Lin F., Shear D.A., Gilsdorf J., Leung L.Y., Bramlett H.M., Dixon C.E., Dietrich W.D., Hayes R.L., Povlishock J., Tortella F.C., Kochanek P.M. and Wang K.K. (2010). Serum-based phospho-neurofilament-heavy protein as theranostic biomarker in three models of traumatic brain injury: an Operation Brain Trauma Therapy (OBTT) study. J. Neurotrauma 36, 348–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bazarian J.J., Biberthaler P., Welch R.D., Lewis L.M., Barzo P., Bogner-Flatz V., Gunnar Brolinson P., Buki A., Chen J.Y., Christenson R.H., Hack D., Huff J.S., Johar S., Jordan J.D., Leidel B.A., Lindner T., Ludington E., Okonkwo D.O., Ornato J., Peacock W.F., Schmidt K., Tyndall J.A., Vossough A., and Jagoda A.S. (2018). Serum GFAP and UCH-L1 for prediction of absence of intracranial injuries on head CT (ALERT-TBI): a multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol. 17, 782–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shaik J.S., Poloyac S.M., Kochanek P.M., Alexander H., Tudorascu D.L., Clark R.S., and Manole M.D. (2015). 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid inhibition by HET0016 offers neuroprotection, decreases edema, and increases cortical cerebral blood flow in a pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest model in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 35, 1757–1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mu Y., Klamerus M.M., Miller T.M., Rohan L.C., Graham S.H., and Poloyac S.M. (2008). Intravenous formulation of N-hydroxy-N'-(4-n-butyl-2-methylphenyl)formamidine (HET0016) for inhibition of rat brain 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid formation. Drug Metab. Dispos. 36, 2324–2330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Javitt D.C., Carter C.S., Krystal J.H., Kantrowitz J.T., Girgis R.R., Kegeles L.S., Ragland J.D., Maddock R.J., Lesh T.A., Tanase C., Corlett P.R., Rothman D.L., Mason G., Qiu M., Robinson J., Potter W.Z., Carlson M., Wall M.M., Choo T.H., Grinband J., and Lieberman J.A. (2018). Utility of imaging-based biomarkers for glutamate-targeted drug development in psychotic disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 75, 11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fagan S.C., Edwards D.J., Borlongan C.V., Xu L., Arora A., Feuerstein G., and Hess D.C. (2004). Optimal delivery of minocycline to the brain: implication for human studies of acute neuroprotection. Exp. Neurol. 186, 248–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Caldwell G.W., Yan Z., Tang W., Dasgupta M. and Hasting B. (2009). ADME optimization and toxicity assessment in early- and late-phase drug discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 9, 965–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deng R., Iyer S., Theil F.P., Mortensen D.L., Fielder P.J., and Prabhu S. (2011). Projecting human pharmacokinetics of therapeutic antibodies from nonclinical data: what have we learned? MAbs 3, 61–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Visser S.A., Wolters F.L., Gubbens-Stibbe J.M., Tukker E., Van Der Graaf P.H., Peletier L.A., and Danhof M. (2003). Mechanism-based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of the electroencephalogram effects of GABAA receptor modulators: in vitro-in vivo correlations. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 304, 88–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leysen J.E., Gommeren W., and Niemegeers C.J. (1983). [3H]Sufentanil, a superior ligand for mu-opiate receptors: binding properties and regional distribution in rat brain and spinal cord. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 87, 209–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim M., Kizilbash S.H., Laramy J.K., Gampa G., Parrish K.E., Sarkaria J.N., and Elmquist W.F. (2018). Barriers to effective drug treatment for brain metastases: a multifactorial problem in the delivery of precision medicine. Pharm. Res. 35, 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kalvass J.C., Olson E.R., Cassidy M.P., Selley D.E., and Pollack G.M. (2007). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of seven opioids in P-glycoprotein-competent mice: assessment of unbound brain EC50,u and correlation of in vitro, preclinical, and clinical data. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 323, 346–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Taskar K.S., Mariappan T.T., Kurawattimath V., Singh Gautam S., Radhakrishna Mullapudi T.V., Sridhar S.K., Kallem R.R., Marathe P., and Mandlekar S. (2017). Unmasking the role of uptake transporters for digoxin uptake across the barriers of the central nervous system in rat. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 9, 1179573517693596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mariappan T.T., Kurawattimath V., Gautam S.S., Kulkarni C.P., Kallem R., Taskar K.S., Marathe P.H., and Mandlekar S. (2014). Estimation of the unbound brain concentration of P-glycoprotein substrates or nonsubstrates by a serial cerebrospinal fluid sampling technique in rats. Mol. Pharm. 11, 477–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Westholm D.E., Rumbley J.N., Salo D.R., Rich T.P., and Anderson G.W. (2008). Organic anion-transporting polypeptides at the blood-brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 80, 135–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xiao G., Black C., Hetu G., Sands E., Wang J., Caputo R., Rohde E., and Gan L.S. (2012). Cerebrospinal fluid can be used as a surrogate to assess brain exposures of breast cancer resistance protein and P-glycoprotein substrates. Drug Metab. Dispos. 40, 779–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kallem R., Kulkarni C.P., Patel D., Thakur M., Sinz M., Singh S.P., Mahammad S.S., and Mandlekar S. (2012). A simplified protocol employing elacridar in rodents: a screening model in drug discovery to assess P-gp mediated efflux at the blood brain barrier. Drug Metab. Lett. 6, 134–144 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hagos F.T., Daood M.J., Ocque J.A., Nolin T.D., Bayir H., Poloyac S.M., Kochanek P.M., Clark R.S., and Empey P.E. (2017). Probenecid, an organic anion transporter 1 and 3 inhibitor, increases plasma and brain exposure of N-acetylcysteine. Xenobiotica 47, 346–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clark R.S., Empey P.E., Bayir H., Rosario B.L., Poloyac S.M., Kochanek P.M., Nolin T.D., Au A.K., Horvat C.M., Wisniewski S.R., and Bell M.J. (2017). Phase I randomized clinical trial of N-acetylcysteine in combination with an adjuvant probenecid for treatment of severe traumatic brain injury in children. PLoS One 12, e0180280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee G., Dallas S., Hong M., and Bendayan R. (2001). Drug transporters in the central nervous system: brain barriers and brain parenchyma considerations. Pharmacol. Rev. 53, 569–596 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huang C., Zheng M., Yang Z., Rodrigues A.D., and Marathe P. (2008). Projection of exposure and efficacious dose prior to first-in-human studies: how successful have we been? Pharm. Res. 25, 713–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Komura H. and Iwaki M. (2008). Species differences in in vitro and in vivo small intestinal metabolism of CYP3A substrates. J. Pharm. Sci. 97, 1775–1800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nishimura T., Amano N., Kubo Y., Ono M., Kato Y., Fujita H., Kimura Y., and Tsuji A. (2007). Asymmetric intestinal first-pass metabolism causes minimal oral bioavailability of midazolam in cynomolgus monkey. Drug Metab. Dispos. 35, 1275–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Millecam J., De Clerck L., Govaert E., Devreese M., Gasthuys E., Schelstraete W., Deforce D., De Bock L., Van Bocxlaer J., Sys S., and Croubels S. (2018). The ontogeny of cytochrome P450 enzyme activity and protein abundance in conventional pigs in support of preclinical pediatric drug research. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nguyen H.Q., Lin J., Kimoto E., Callegari E., Tse S., and Obach R.S. (2017). Prediction of losartan-active carboxylic acid metabolite exposure following losartan administration using static and physiologically based pharmacokinetic models. J. Pharm. Sci. 106, 27582770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Martin I.J., Hill S.E., Baker J.A., Deshmukh S.V., and Mulrooney E.F. (2016). A pharmacokinetic modeling approach to predict the contribution of active metabolites to human efficacious dose. Drug Metab. Dispos. 44, 1435–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mahmood I. (1999). Prediction of clearance, volume of distribution and half-life by allometric scaling and by use of plasma concentrations predicted from pharmacokinetic constants: a comparative study. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 51, 905–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nagilla R. and Ward K.W. (2004). A comprehensive analysis of the role of correction factors in the allometric predictivity of clearance from rat, dog, and monkey to humans. J. Pharm. Sci. 93, 2522–2534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mahmood I. and Boxenbaum H. (2014). Vertical allometry: fact or fiction? Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 68, 468–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hallifax D., Foster J.A., and Houston J.B. (2010). Prediction of human metabolic clearance from in vitro systems: retrospective analysis and prospective view. Pharm. Res. 27, 2150–2161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li R., Barton H.A., and Varma M.V. (2014). Prediction of pharmacokinetics and drug-drug interactions when hepatic transporters are involved. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 53, 659–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Toler S.M., Young A.B., McClain C.J., Shedlofsky S.I., Bandyopadhyay A.M., and Blouin R.A. (1993). Head injury and cytochrome P-450 enzymes. Differential effect on mRNA and protein expression in the Fischer-344 rat. Drug Metab. Dispos. 21, 1064–1069 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Poloyac S.M., Perez A., Scheff S., and Blouin R.A. (2001). Tissue-specific alterations in the 6-hydroxylation of chlorzoxazone following traumatic brain injury in the rat. Drug Metab. Dispos. 29, 296–298 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Morgan P., Van Der Graaf P.H., Arrowsmith J., Feltner D.E., Drummond K.S., Wegner C.D., and Street S.D. (2012). Can the flow of medicines be improved? Fundamental pharmacokinetic and pharmacological principles toward improving Phase II survival. Drug Discov. Today 17, 419–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]