Abstract

The ease with which the unicellular yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae can be manipulated genetically and biochemically has established this organism as a good model for the study of human mitochondrial diseases. The combined use of biochemical and molecular genetic tools has been instrumental in elucidating the functions of numerous yeast nuclear gene products with human homologs that affect a large number of metabolic and biological processes, including those housed in mitochondria. These include structural and catalytic subunits of enzymes and protein factors that impinge on the biogenesis of the respiratory chain. This article will review what is currently known about the genetics and clinical phenotypes of mitochondrial diseases of the respiratory chain and ATP synthase, with special emphasis on the contribution of information gained from pet mutants with mutations in nuclear genes that impair mitochondrial respiration. Our intent is to provide the yeast mitochondrial specialist with basic knowledge of human mitochondrial pathologies and the human specialist with information on how genes that directly and indirectly affect respiration were identified and characterized in yeast.

Keywords: mitochondrial diseases, respiratory chain, yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, pet mutants

1. Introduction

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that supply most of the ATP needed to sustain the different energy-demanding activities of eukaryotic cells. Their ATP generating pathway consists of the oxphos complexes—four hetero-oligomeric complexes that make up the electron transfer chain plus the ATP synthase. Some complexes of this pathway are genetic hybrids composed of both mitochondrial and nuclear gene products. Most of the organelle, however, consists of proteins that are encoded by nuclear genes, their mRNAs translated on cytoplasmic ribosomes and the protein products transported to their proper internal membrane and soluble compartments. It is estimated that the nuclear proteome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae dedicated to the maintenance of respiratory competent mitochondria consists of at least 900 proteins [1]. Much of our information about the functions of this class of nuclear genes has been learned from studies of yeast. The identity of proteins localized in mitochondria and the phenotypic consequences of null mutations in their genes has come from large-scale proteomic studies. Information about the functions of nuclear gene products at the molecular level, however, has been gathered from a large body of previously known information of protein structure and function and from more recent in-depth biochemical analyses of yeast nuclear pet mutants. A search of the current Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) [2] indicates that the functions of some 170 proteins of the mitochondrial proteome essential for respiration and/or ATP synthesis are still not known.

2. Yeast, a Model for Studying Mitochondrial Function and Biogenesis

The last 50 years have witnessed unparalleled technical advances in deciphering the genetic compositions of whole genomes, so much so that whole new specialties have been born with the goal of developing tools for analyzing and dealing with this wealth of data in almost every major area of biological research. Of course, genes are only a starting point for the more interesting question of what their protein products do. This is one of the central questions of proteomics, which strives to develop methods for the simultaneous analysis of the entire complement of proteins in organisms, tissues and cells. Although the field as it stands today is highly successful in many important areas, such as ascertaining subcellular protein localization, their transient, as well as stable, physical interactions and patterns of expression during cell division, development, and diseased states, an understanding of their molecular functions and the specific cellular process they participate in continues to depend on slugfest genetics and biochemistry on a single or a small number of genes.

Respiratory deficient pet mutants of S. cerevisiae, particularly those obtained in Alexander Tzagoloff’s laboratory [3], have been helpful in identifying a number of nuclear gene products essential for maintaining structurally and functionally competent mitochondria. The genes represented by about two thirds of the 215 complementation groups in such collections [3] have been characterized and their functions deduced.

One of the unexpected finding to have emerged from the functional analyses of pet mutants is the large extent to which expression of mitochondrial genes depends on mRNA-specific factors encoded in nuclear DNA. Also unexpected are the many accessory proteins that function in translation and assembly of the respiratory and ATP synthase complexes. For the most part this class of mitochondrial proteins target translation of specific mitochondrial mRNAs and maturation and biogenesis of their encoded proteins. For example, some three dozen proteins that are not constituents of cytochrome oxidase are currently known to be required specifically for the assembly of this single respiratory complex. Foreseeably, still unrecognized assembly factors may be discovered with further biochemical and genetic screens of uncharacterized pet mutants.

Mutations in human mitochondrial genes for subunit polypeptides of NADH-coenzyme Q reductase, cytochrome oxidase (COX, Complex IV), coenzyme Q-cytochrome c reductase (bc1 complex, Complex III) and ATP synthase (Complex V), were the first to be identified [4]. Subsequently, mutations presenting different clinical phenotypes were reported in nuclear genes that code for protein subunits of the ATP synthase and factors that function as chaperones during its assembly [5,6,7] and enzymes of biosynthetic pathways for heme a [8] and coenzyme Q [9]. A more complete blueprint of the regulatory proteins and chaperone factors that contribute to the biogenesis of respiratory competent mitochondria will uncover new chaperones and regulatory factors, some of which will undoubtedly have human homologs.

Human cells are more complex than yeast cells; and the same can be stated about the mitochondria of these two organisms. The higher the organization and the complexity, the more the consequences of one given deficiency differ. In many tested mutations, the phenotypes observed in humans are more deleterious for cell survival than in the yeast counterpart, which is not only true because yeast can ferment but also because of the variable energy demand of a complex organism with different tissues. As an example, the deletion of MRX10 in yeast did not impair its respiratory capacity but mutations in the human counterpart led to respiratory impairment even in cells with low energetic demand such as fibroblasts [10]. In other circumstances, due to the need of proper protein-protein interactions, or just because of evolutionary divergence, the possibility of heterologous complementation is lost. For instance, yeast shy1 mutants are not complemented by the human homolog SURF1, even with chimeric versions of the gene [11]. However, when the human genes do not complement the respective yeast mutant, it is still possible to evaluate the pathogenicity of a given mutation by constructing an allele with the corresponding change in the yeast gene.

3. Strategy for Determining the Function of Unknown Mitochondrial Proteins

A useful initial step for identifying the biochemical lesion of pet mutants is to assign them to one of three broad phenotypic classes based on the spectral properties of their mitochondria. This substantially reduces the number of subsequent assays. For example, a strain showing a normal complement of mitochondrial cytochromes and respiratory chain complexes can be excluded from harboring a mutation in a gene that affects mitochondrial translation, as both COX and the bc1 complex contain subunit polypeptides (cytochromes a, a3, and cytochrome b) that are translated on mitochondrial ribosomes [12]. By the same token, a selective loss of cytochrome a generally signals a mutation in a gene required either for:

-

(1)

Expression of one of the mitochondrial gene products of the COX complex;

-

(2)

Assembly of this complex; or

-

(3)

Maturation of the heme active centers of the enzyme.

A similar argument can be made for mutants lacking cytochrome b, except that a safe assumption is that the lesion affects some aspect of bc1 biogenesis.

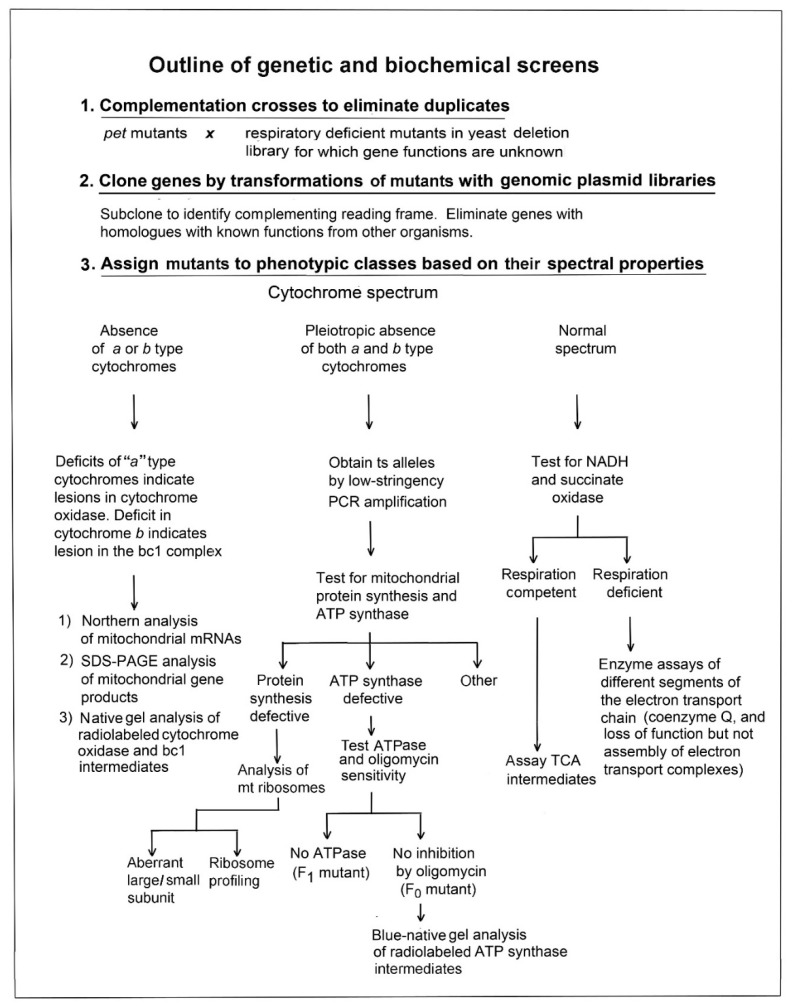

Finally, mutations in genes that are directly or indirectly required for the maintenance of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), undergo a large deletion or complete loss of the genome resulting in a population of cytoplasmic petites (ρ- and ρ0 mutants). Particularly prevalent in this class are mitochondrial protein synthesis mutants, (e.g. aminoacyl tRNA synthases and ribosomal mutants) [13] and mutants with defective ATP synthase [14,15]. Both mitochondrial translation and ATP synthase mutants display the absence of “a” and “b” type cytochromes for the reasons indicated above. An outline of the screens useful in identifying different classes of pet mutants is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Genetic and biochemical screening of pet mutants. The initial complementation tests are done to identify pet mutants with counterparts in the knockout strain collection. This eliminates the need to clone and sequence genes already annotated.

4. Pathological Mutations in Respiratory Chain and ATP Synthase Human Genes with S. cerevisiae Homologs

In this section, the reader will find information on complexes II, III and IV, ATP synthase, Coenzyme Q and cytochrome c. All genes with pathogenic variants encoding subunits of the respiratory complexes and ATP synthase will be described. Regarding assembly factors, we have included only the ones that have yeast homologs.

4.1. Complex II

Succinate-coenzyme Q oxidoreductase, or Complex II, is a membrane-bound enzyme that functions in both the TCA cycle and the electron transfer chain. In the TCA cycle, it catalyzes the oxidation of succinate to fumarate using coenzyme Q as the electron acceptor without accompanying ATP synthesis [16]. The reduced coenzyme Q formed in this reaction is then reoxidized by Complex III, a reaction coupled to the translocation of protons across the mitochondrial inner membrane and ATP synthesis. Fungal and mammalian Complex II is embedded in the mitochondrial inner membrane, with a large portion protruding into the matrix. It is composed of four protein subunits, including the flavoprotein succinate dehydrogenase with covalently bound FAD and the iron sulfur subunit. Both of these catalytic subunits are peripheral proteins facing the matrix side of the inner membrane [17,18]. All four subunits of Complex II are encoded in the nucleus. The two catalytic subunits of Complex II are encoded by SDHA and SDHB in humans and by SDH1 and SDH2 in yeast. The other two subunits are integral membrane proteins that form a dimer that houses a single heme b group of cytochrome b560 and the two coenzyme Q binding sites of the complex. These two membrane anchors of the catalytic sector are encoded by human SDHC and SDGD and yeast SDH3 and SDH4.

In yeast, Sdh3 is a bifunctional protein that is also a subunit of the TIM22 protein translocase complex responsible for transporting and integrating members of the substrate exchange carrier family into the inner membrane [19]. Electrons released during the oxidation of succinate first reduce the FAD cofactor of SDHA and are then sequentially transferred to three iron-sulfur clusters in SDHB before reacting with coenzyme Q [18,20,21,22]. S. cerevisiae sdh1–4 mutants are respiratory deficient and display a severe growth defect on non-fermentable carbon sources such as glycerol and ethanol. The function of the cytochrome b560 is not fully understood, but it is thought to shuttle electrons between the two ubiquinone binding sites [23].

4.1.1. Mutations in Complex II Catalytic and Structural Subunits

Patients with lactic acidosis resulting from reduced succinate dehydrogenase activity have been linked to mutations in all four gene products of human Complex II. Although patients with deficiencies in the respiratory chain complexes, including Complex II, had been reported earlier [24], SDHA was the first instance of a nuclear encoded protein of the electron transfer chain with a mutation shown to cause a respiratory defect [25]. In that study, two siblings were homozygous for an R554T substitution in SDHA which resulted in Leigh syndrome, a severe neurological disorder that affects the central nervous system first described by Denis Leigh in 1951 [26]. The attribution of the phenotype to the mutation in SDHA was confirmed when the homologous mutation in the yeast flavoprotein was shown to have a deleterious effect on Complex II activity [25]. In the past 20 years, other SDHA mutations have been reported in patients presenting different clinical phenotypes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pathologies resulting from mutations in genes encoding Complex II subunits and assembly factors, and their yeast homologs.

| Human Gene | Yeast Gene | Clinical Phenotype 1 | Mutation | Confirmation in Yeast | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDHA | SDH1 | Leigh syndrome | homozygous R554W | yes | [25] |

| compound heterozygous A524V, M1L | no | [45] | |||

| compound heterozygous W119*, A83V | no | [46] | |||

| homozygous G555E | no | [27] | |||

| late-onset optic atrophy, ataxia, myopathy | heterozygous R408C | no | [47] | ||

| neonatal isolated cardiomyopathy | homozygous G555E | no | [28] | ||

| undefined 2 | homozygous G555E | no | [29] | ||

| encephalopathy | compound heterozygous—stop codons at residues 56 and 81 | no | [48] | ||

| cardiomyopathy, leukodystrophy | compound heterozygous T508I, S509L | no | [49] | ||

| optic atrophy, progressive, polyneuropathy, cardiomyopathy | heterozygous R451C | no | [50] | ||

| SDHB | SDH2 | hypotonia, leukodystrophy | homozygous D48V | yes | [49] |

| leukoencephalopathy | compound heterozygous D48V, R230H; homozygous L257V 3 | no | [51] | ||

| SDHD | SDH4 | early progressive encephalomyopathy | compound heterozygous E69K, *164Lext*3 | no | [52] |

| SDHAF1 | SDH6 | leukoencephalopathy | homozygous G57R; homozygous R55P 3 |

yes | [34] |

| homozygous R55P; homozygous Q8*; homozygous G57E 3 |

no | [37] |

1 Paragangliomas were not included in the table. 2 The patient died at five months of age following a respiratory infection before developing other phenotypes. 3 In different patients.

Interestingly, the same homozygous G555E substitution was identified in patients with distinct phenotypes: Leigh syndrome [27] and neonatal isolated cardiomyopathy [28]. This mutation was also found in a baby that died at five months of age following a respiratory infection before developing other phenotypes [29]. There is evidence that the G555E mutation prevents an adequate interaction between SDHA and SDHB [29]. This is supported by earlier studies on yeast Complex II assembly involving chimeric human/yeast genes [30].

More recently, germline mutations in SDHA were found in three patients with persistent polyclonal B cell lymphocytosis. In contrast to the other cases mentioned, the mutations resulted in a substantial increase of Complex II activity, leading to fumarate accumulation which engaged the KEAP1–Nrf2 system to drive the expression of inflammatory cytokines [31]. Mitochondrial pathologies have also been ascribed to mutations in SDHB and SDHD (Table 1).

4.1.2. Mutations in Complex II Assembly Factors

Respiratory deficiency is also elicited by mutations in accessory proteins that are required for assembly but are not constituents of Complex II [32,33]. Four such assembly factors have been identified for the human complex: SDHAF1-4, with yeast homologs SDH6, SDH5, SDH7, and SDH8, respectively [32,34,35,36]. Mutations in SDHAF1 (yeast SDH6), that codes for an assembly factor of Complex II, result in infantile leukoencephalopathy and have been reported in five patients, some sharing substitutions at the same residues [34,37].

4.1.3. Complex II and Paragangliomas

Mutations in SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, SDHAF2, and SDHAF3 have been identified in an increasing number of neoplasms, mainly paragangliomas (rare neoplasms of the autonomic nervous system) and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. A discussion of these mutations is beyond the scope of this article but the topic has been extensively reviewed by others [38,39,40,41,42,43]. Variants in these genes have been associated with a high probability of developing cancer. To improve the identification of putative cancer-inducing human genetic variants, 22 known human variants of SDHA were examined in yeast [44]. Complementation tests of the homologous mutations in yeast sdh1 identified 16 variants that affected the growth of yeast on the non-fermentable carbon source glycerol. The corresponding 16 human variants were proposed to be putative cancer inducing amino acid substitutions.

4.2. Complex III

Complex III or the bc1 complex is an integral inner membrane homodimeric complex of the mitochondrial inner membrane that catalyzes the oxidation of reduced coenzyme Q and reduction of cytochrome c, a reaction coupled to the translocation of protons from the matrix to the inter-membrane space [53]. Both human and yeast Complex III contain three catalytic subunits: a mitochondrially-encoded cytochrome b, with two non-covalently bound heme b containing redox centers corresponding to cytochromes bH and bL; cytochrome c1, with a covalently linked heme b; and the Rieske iron-sulfur protein [53,54,55,56]. In addition to the three catalytic subunits, Complex III contains seven other subunits, four of which are essential for the assembly and stability of the complex but do not participate in either electron transfer or proton translocation (Table 2). Like cytochrome c1 and the Rieske iron sulfur protein, all the non-catalytic subunits are products of nuclear genes.

Table 2.

Yeast complex III subunits and their human homologs. The table also shows Complex III assembly factors that are associated with diseases.

| Yeast Gene | Genome | pet Mutant | Human Gene | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Subunits | COB | mitochondrial | N/A | MT-CYB | catalysis |

| CYT1 | nuclear | yes | CYC1 | catalysis | |

| RIP1 | nuclear | yes | UQCRFS1 | catalysis | |

| COR1 | nuclear | yes | UQCRC1 | structure | |

| COR2 | nuclear | yes | UQCRC2 | structure | |

| QCR6 | nuclear | no | UQCRH | structure | |

| QCR8 | nuclear | yes | UQCRQ | structure | |

| QCR7 | nuclear | yes | UQCRB | structure | |

| QCR9 | nuclear | no | UQCR10 | structure | |

| QCR10 | nuclear | no | UQCR11 | structure | |

| Assembly Factors | CBP3 | nuclear | yes | UQCC1 | translation/assembly of cyt. b |

| CBP6 | nuclear | yes | UQCC2 | translation/assembly of cyt. b | |

| CBP4 | nuclear | yes | UQCC3 | assembly of cyt. b | |

| MZM1 | nuclear | no | LYRM7 | assembly of Rieske protein | |

| BCS1 | nuclear | yes | BCS1L | assembly of Rieske protein |

Assembly of Complex III also depends on nuclear encoded chaperones and on factors that regulate translation and assembly of cytochrome b. Most of the currently known Complex III assembly factors that were first described in yeast are conserved in humans (Table 2). Among yeast factors that have human homologs associated with diseases, there are Cbp6 and Cbp4. Cbp6, together with Cbp3, forms a complex with nascent apocytochrome b [57] for subsequent addition of heme to form the redox center at the cytochrome bL site, followed by stabilization of the partially mature protein by Cbp4 [58] and further hemylation of the cytochrome bH site [59]. Mitochondrial pathologies have also been reported in patients with mutations in human homologs of two other factors, Bcs1 and Mzm1, both needed for maturation and insertion of the Rieske iron sulfur protein into the complex [60,61,62].

Most laboratory strains of S. cerevisiae have a mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (COB) containing group I and II introns that are post-transcriptionally removed [63,64]. Some of the group II introns contain reading frames that code for factors, termed maturases, that function in splicing their own introns [65]. Splicing of the terminal group I intron is aided by a protein factor encoded by a nuclear gene [66]. In addition to these splicing factors, expression of COB depends on other factors that stabilize and activate translation of the mRNA [67,68]. Due to the absence of introns in the human cytochrome b gene and of 5′- non-coding sequences in the human mRNA, none of the yeast RNA splicing factors and translational activators have human homologs.

Complex III disorders are relatively rare but, like mutations in the other respiratory complexes, they present a wide spectrum of phenotypes. Complex III deficiency can be caused by mutations in the mitochondrially-encoded cytochrome b, in nuclear genes coding for catalytic and structural subunits and in ancillary proteins that function in assembly of the complex.

4.2.1. Mutations in Complex III Catalytic Subunits

Most of the known Complex III associated pathologies result from mutations in MT-CYB, the human mitochondrial cytochrome b gene, that have so far been described in 49 different positions of the genome [69]. Typical phenotypes include MELAS (mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes), LHON (Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy), hearing loss and in some cases less severe phenotypes expressed in exercise intolerance (reviewed in [70]). While some cytochrome b mutations are maternally inherited, others are heteroplasmic and are present mainly in muscle tissue, suggesting that they arise de novo after differentiation of the primary germ layers. Additionally, some LHON patients with a mutation in one of the mitochondrially encoded Complex I genes have a second mutation in cytochrome b, which exacerbates the severity of the pathology [71,72,73]. Mutations in the nuclear UQCR4 (yeast CYC1) and UQCRFS1 (yeast RIP1) genes are much rarer and were more recently identified (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pathologies resulting from mutations in genes encoding Complex III subunits and assembly factors, and their yeast homologs.

| Human Gene | Yeast Gene | Clinical Phenotype | Mutation | Confirmation in Yeast | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT-CYB | COB | MELAS, LHON, hearing loss, exercise intolerance | many | [70] 1 | |

| UQCR4 | CYT1 | ketoacidosis and insulin-responsive hyperglycemia | homozygous L215F; homozygous T96C 2 | yes | [115] |

| UQCRFS1 | RIP1 | cardiomyopathy and alopecia totalis | homozygous V72_T81del10; heterozygous V14D; heterozygous R204∗ 2 | no | [116] |

| UQCRC2 | COR2 | neonatal onset of hypoglycemia | homozygous R183W | no | [77,78] |

| UQCRB | QCR7 | hypoglycemia | homozygous 4 bp deletion at nucleotides 338–341 | yes [75] | [74] |

| UQCRQ | QCR8 | severe psychomotor retardation, dystonia, athetosis, ataxia, dementia | homozygous S45F | no | [76] |

| UQCC2 | CBP6 | intrauterine growth retardation, renal tubular dysfunction | homozygous c.214-3C>G 3 | no | [111] |

| neonatal encephalomyopathy | homozygous R8P and L10F 4 | no | [112] | ||

| UQCC3 | CBP4 | hypoglycemia, hypotonia, delayed development | homozygous V20E | no | [114] |

| BCS1L | BCS1 | GRACILE syndrome, Björstand syndrome, encephalopathy, muscle weakness | many | see main text | |

| LYRM7 | MZM1 | early onset severe encephalopathy | homozygous D25N | yes | [106] |

| leukoencephalopathy | homozygous c.243_244 + 2del 3 | no | [107] | ||

| several | yes | [108] | |||

| homozygous 4bp deletion c.[243_244 + 2delGAGT] 3 | no | [109] | |||

| liver dysfunction | homozygous R18Dfs*12 | no | [110] |

1 Review describing many mutations. 2 In different patients. 3 Mutation causing a splicing defect. 4 In the same patient.

4.2.2. Mutations in Complex III Structural Subunits

A 4 bp deletion in UQCRB resulting in a change in the last seven amino acids and an addition of a stretch of 14 amino acids at the C-terminal end of the protein was the first described case of a Complex III deficiency resulting from mutations in a nuclear encoded subunit of the complex [74]. Interestingly, earlier studies on yeast Complex III showed that deletions in the C-terminal helical domain of the QCR7 homolog resulted in reduced levels of the subunit and of cytochrome b, Rip1, and Qcr8 [75]. Taken together, these studies show the importance of the helical domain of UQCRB in the maintenance or assembly of human and yeast Complex III.

The discovery of the deletions in UQCRB was followed by the identification of a pathogenic variant of UQCRQ [76]. A pathogenic mutation in UQCRC2 was also identified: three patients from a Mexican consanguineous family with neonatal onset of hypoglycemia and lactic acidosis were found to have a homozygous mutation leading to a R183W substitution in the Core 2 subunit. The patients also showed hyperammonemia, high urine organic acids and elevated plasma hydroxyl fatty acids, suggesting that the UQCRC2 mutation may elicit secondary effects on TCA and urea cycles and beta-oxidation. Modeling of the crystal structure of bovine Complex III predicted that the R183W mutation would disrupt the hydrophobic interface of the UQCRC2 homodimer, leading to Complex III destabilization. This was supported by an 80% decrease of the complex in the patients, even though Complex III activity was only marginally affected [77]. More recently, the same homozygous mutation with similar symptoms was described in a French child [78]. Furthermore, the expression of UQCRC2 is upregulated in multiple human tumors, whereas its suppression inhibits cancer cells and induces senescence [79].

4.2.3. Mutations in Complex III Assembly Factors

Together with cytochrome b, most Complex III pathologies are derived from mutations in the nuclear BCS1L gene. Its yeast homolog BCS1 is an AAA protease that was shown to be required for the expression/maturation of Rip1 [60,61]. Later studies indicated that Bcs1 promotes one of the steps in the translocation of Rip1 necessary for incorporation of the iron-sulfur center [80]. Bcs1 exists as a heptamer with a contractile central cavity that participates in the translocation of the folded Rip1. Additionally, Bcs1 is associated with the complex III assembly module and its dissociation ends the maturation process [81].

Mutations in BCS1L comprise a wide spectrum of pathologies, including: GRACILE syndrome (growth retardation, aminoaciduria, cholestasis, iron overload, lactic acidosis, early death) [82,83,84,85,86,87,88]; Björstand syndrome, characterized by hearing loss and pili torti [89,90,91,92,93,94]; encephalopathy [95,96,97,98]; lactic acidosis, liver dysfunction and tubulopathy [99,100,101,102]; muscle weakness, focal motor seizures and optic atrophy [103], among others. Besides low steady state levels of Complex III, cells from patients with BSC1L mutations have impaired mitochondrial import of the protein as evidenced by its accumulation in the cytosol [91]. An adult harboring a R69C missense mutation was diagnosed with aminoaciduria, seizures, bilateral sensorineural deafness, and learning difficulties. Yeast complementation studies corroborate that the R69C mutation impairs the respiratory capacity of the cell [104].

Assembly of Rip1 is thought to be the last step in the biogenesis of Complex III [81]. In addition to Bcs1, this assembly step was found to require the product of the yeast nuclear MZM1 gene [105]. The first case of Complex III deficiency caused by a mutation in LYRM7, the human homolog of MZM1, was reported in 2013 [106]. The equivalent mutation in yeast resulted in decreased oxygen consumption as a result of reduced steady state levels of Rieske protein and Complex III. Since then, Complex III deficiency caused by LYRM7 has been identified in patients presenting with leukoencephalopathy [107,108,109] and liver dysfunction [110].

Mutations have also been reported in recent years in the human UQCC2 and UQCC3 genes that code for protein homologs of yeast complex III assembly factors Cbp6 and Cbp4. Complex III deficiency was found in a patient with a homozygous mutation in UQCC2 [111]. This study demonstrated that the biochemical phenotype produced by the UQCC2 mutation is similar to that reported in yeast [57], as cytochrome b synthesis and stability was decreased in the patient’s fibroblasts [111]. A homozygous mutation in UQCC2 leading to a Complex III deficiency was also reported in a consanguineous baby presenting neonatal encephalomyopathy. This mutation resulted in a secondary deficiency of Complex I [112]. The authors proposed that assembled Complex III is required for the stability or assembly of complexes I and IV, which may be related to supercomplex formation. Interestingly, a recent study [113] showed that the ND1 subunit of Complex I co-immunoprecipitated with newly synthesized UQCRFS1 of Complex III in mammalian mitochondria, indicating a possible coordination of the assembly of the two complexes.

During assembly of yeast Complex III, Cbp4 is recruited by the Cbp3–Cbp6-cytochrome b ternary complex following release of the latter from the mitoribosome [57]. Wanschers et al. [114] described a homozygous mutation in UQCC3, the human homolog of CBP4, in a patient diagnosed with isolated Complex III deficiency. Cultured fibroblasts from the patient were partially deficient in cytochrome b and had no detectable UQCC3 protein. The authors concluded that UQCC3 functions in Complex III assembly downstream of UQCC1 and UQCC2, as the absence of UQCC3 did not affect the levels of UQCC1 and UQCC2 [114]. These observations are consistent with the above mentioned sequential interaction of Cbp4 with the Cbp3-Cbp6-cytochrome b complex during synthesis and assembly of cytochrome b [57].

4.3. Complex IV

Complex IV or cytochrome oxidase (COX) is an integral mitochondrial inner membrane protein complex that catalyzes the oxidation of cytochrome c and the reduction of molecular oxygen to water. This reaction is coupled to the translocation of protons from the matrix to the inter-membrane space [117]. In both human and yeast mitochondria, the COX catalytic core is composed of three proteins encoded in the mitochondrial DNA. They are Cox1, Cox2, and Cox3 in yeast, and MTCO1, MTCO2, and MTCO3 in humans. All the redox centers of COX are located in the Cox1 and Cox2 subunits. Yeast but not human Cox2 is synthesized with a cleavable N-terminal presequence that is required for correct insertion of the protein into the membrane [118]. Cox3 does not contain redox centers. It is thought to stabilize the catalytic core and to enhance the uptake of protons from the mitochondrial matrix [119]. One of the redox centers of Cox1, corresponding to cytochrome a, contains heme a. The second center, corresponding to cytochrome a3, consists of a binuclear heme a-CuB. The third center, located on Cox2, is the binuclear CuA. In addition to the catalytic core, COX is composed of several other structural subunits, all encoded in nuclear DNA (Table 4). Recently NDUFA4/COXFA4, a subunit previously thought to be part of Complex I, has been shown to be a subunit of COX [120].

Table 4.

Yeast complex IV subunits and their human homologs. The table also shows Complex IV assembly factors that are associated with diseases.

| Yeast Gene | Genome | pet Mutant | Human Gene | Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Subunits | COX1 | mitochondrial | N/A | MTCO1 | catalysis |

| COX2 | mitochondrial | N/A | MTCO2 | catalysis | |

| COX3 | mitochondrial | N/A | MTCO3 | structure/catalysis | |

| COX5a | nuclear | yes | COX4 | structure | |

| COX5b 1 | nuclear | no | - | structure | |

| COX6 | nuclear | yes | COX5A | structure | |

| COX4 | nuclear | yes | COX5B | structure | |

| COX13 | nuclear | no | COX6A | structure | |

| COX12 | nuclear | yes | COX6B | structure | |

| COX9 | nuclear | yes | COX6C | structure | |

| COX7 | nuclear | yes | COX7A | structure | |

| - | nuclear | - | COX7B | structure | |

| COX8 | nuclear | no | COX7C | structure | |

| - | nuclear | - | COX8 | structure | |

| - | nuclear | - | NDUFA4/COXFA4 | structure | |

| Assembly Factors | COX20 | nuclear | yes | COX20/FAM36A | membrane insertion of Cox2 |

| COX14 | nuclear | yes | COX14 | regulation of COX1 expression, maintenance of monomeric Cox1 | |

| PET117 | nuclear | yes | PET117 | couples synthesis of heme a to COX assembly | |

| PET191 | nuclear | yes | COA5 | required for COX assembly | |

| PET100 | nuclear | yes | PET100 | required for COX assembly | |

| COA6 | nuclear | no | COA6 | maturation of the CuA site | |

| COX25/COA3 | nuclear | yes | COA3 | translational regulation of COX1 mRNA | |

| COX15 | nuclear | yes | COX15 | conversion of heme o to heme a | |

| COX10 | nuclear | yes | COX10 | farnesylation of heme b | |

| SCO1 | nuclear | yes | SCO1 | maturation of the CuA site | |

| SCO2 | nuclear | no | SCO2 | maturation of the CuA site | |

| SHY1 | nuclear | yes | SURF1 | hemylation of Cox1 |

1 Yeast subunit 5b is a paralog of subunit 5a and under standard conditions of growth is present at low concentrations [134].

COX catalyzes the consecutive transfer of 4 electrons from cytochrome c to a molecule of oxygen bound to the heme a of cytochrome a3 with the formation of water. Each electron of cytochrome c first reduces the CuA center of Cox2, from which it is then transferred to the heme a of cytochrome a and finally to the binuclear heme a –Cu center of cytochrome a3 [121,122].

The heme a differs from heme b at two positions of the porphyrin ring. While heme b is present in hemoglobin and most heme containing enzymes, heme a appears only in COX. The biosynthesis of heme a is initiated by the addition of a farnesyl group to the C-2 position of the heme b porphyrin ring by farnesyl transferase, encoded by COX10 [123]. The resulting heme o is then converted to heme a by the oxidation of a methyl to a formyl group on C-8 of the porphyrin ring in a reaction that requires Cox15, mitochondrial ferredoxin, and ferredoxin reductase [124,125]. Some other factors, such as Shy1 (human SURF1) and Pet117, have been shown to be involved in the hemylation of Cox1 [126,127]. Additionally, several proteins with human homologs, including Cox17, Sco1, Sco2, Cox11, Cox19, Cox23, Cox16, and Cmc1 have been implicated in the trafficking of copper and maturation of the CuA and heme a-CuB centers, as reviewed elsewhere [128].

Pathological mutations have been reported in both mitochondrial and nuclear encoded COX subunits, as well as in proteins involved in the biogenesis of the complex. As of today, mutations in more than 20 genes can lead to COX deficiency with a broad spectrum of clinical phenotypes (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pathologies resulting from mutations in genes encoding Complex IV subunits and assembly factors, and their yeast homologs.

| Human Gene | Yeast Gene | Clinical Phenotype | Mutation | Confirmation in Yeast | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTCO1 | COX1 | prostate cancer, LHON, SNHL, DEAF | many | See main text | |

| MTCO2 | COX2 | progressive encephalomyopathy, HCM, SNHL, DEAF, LHON | many | See main text | |

| MTCO3 | COX3 | LHON, Alzheimer’s disease | many | See main text | |

| COX4 | COX5a | pancreatic insufficiency, dyserythropoeitic anemia, calvarial hyperostosis | homozygous E138K | no | [155] |

| short stature, poor weight gain, mild dysmorphic features with highly suspected Fanconi anemia | homozygous K101N | no | [156] | ||

| COX5A | COX6 | early-onset pulmonary arterial hypertension, failure to thrive | homozygous R107C | no | [157] |

| COX6a | COX13 | axonal or mixed form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease | homozygous c.247−10_247−6delCACTC 3 | no | [158,159] |

| COX6b | COX12 | infantile encephalomyopathy, myopathy, growth retardation | homozygous R19H | yes | [160] |

| encephalomyopathy, hydrocephalus, HCM | homozygous R20C | no | [161] | ||

| cystic leukodystrophy | homozygous c.241A>C | no | [162] | ||

| COX7b | microphthalmia with linear skin lesions | heterozygous c.196delC; heterozygous c.41-2A>G 3; heterozygous Q19∗ 2 | no | [136] | |

| COX8 | Leigh-like syndrome, epilepsy | homozygous c.115-1G>C 3 | no | [163] | |

| NDUFA4 | Leigh syndrome | homozygous c.42+1G>C 3 | no | [164] | |

| FAM36A | COX20 | dystonia and ataxia | homozygous T52P | no | [165,166] |

| dysarthria, ataxia, sensory neuropathy | compound heterozygous K14R, G114S, c.157+3G>C 3 | no | [167] | ||

| axonal neuropathy, static encephalopathy | compound heterozygous L14R, W74C | no | [168] | ||

| COX14 | COX14 | fatal neonatal lactic acidosis, dysmorphic features | homozygous M19I | no | [169] |

| PET117 | PET117 | neurodevelopmental regression, medulla oblongata lesions | homozygous c.172C>T (stop codon at residue 58) | no | [170] |

| COA5 | PET191 | fatal neonatal cardiomyopathy | homozygous A53P | no | [171] |

| PET100 | PET100 | Leigh syndrome | homozygous c.3G>C (p.Met1?) | no | [172] |

| fatal infantile lactic acidosis | homozygous Q48* | no | [173] | ||

| COA6 | COA6 | HCM | homozygous W66R | no | [174] |

| compound heterozygous W59C, E87* | yes [175] | [162] | |||

| COA3 | COX25 | neuropathy, exercise intolerance, obesity, short stature | compound heterozygous L67Pfs*21, Y72C | no | [176] |

| COX15 | COX15 | Leigh syndrome | homozygous L139V | no | [177] |

| homozygous R217W | no | [178] | |||

| compound heterozygous S152*, S344P | no | [147] | |||

| infantile cardioencephalopathy | compound heterozygous S151*, R217W | no | [179] | ||

| early-onset fatal HCM | compound heterozygous R217W, c.C447-3G 3 | no | [180] | ||

| COX10 | COX10 | severe muscle weakness, hypotonia, ataxia, ptosis, pyramidal syndrome, status epilepticus | homozygous N204K | yes | [8] |

| Leigh-like disease | homozygous T>C in the ATG start codon | no | [181] | ||

| anemia, sensorineural deafness, fatal infantile HCM | compound heterozygous T196K, P225L | no | [182] | ||

| Leigh syndrome, anemia | compound heterozygous D336V, D336G | no | [182] | ||

| myopathy, demyelinating neuropathy, premature ovarian failure, short stature, hearing loss | compound heterozygous D336V, R339W | yes | [146] | ||

| Leigh syndrome, anemia | homozygous P225L | no | [183] | ||

| hypotony, sideroblastic anemia, progressive encephalopathy | compound heterozygous M344V, L424Pfs | no | [183] | ||

| developmental delay, short stature | compound heterozygous R228H, deletion disrupting the last 2 exons | no | [184] | ||

| SCO1 | SCO1 | encephalopathy, hepatopathy, hypotonia, or cardiac involvement | homozygous G106del | no | [185] |

| fatal infantile encephalopathy | compound heterozygous M294V, V93* | no | [186] | ||

| early onset HCM, encephalopathy, hypotonia, hepatopathy | homozygous G132S | no | [187] | ||

| neonatal-onset hepatic failure, encephalopathy | compound heterozygous P174L, ΔGA nt 363–364 | no | [8] | ||

| SCO2 | SCO2 | cardioencephalomyopathy, Leigh syndrome, high myopia, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease 2 | many | [151,152,154] 1 | |

| SURF1 | SHY1 | Leigh syndrome, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease 2 | many | [139,142] 1; |

1 Review describing many mutations. 2 In different patients. 3 Splicing mutation.

Furthermore, COX interacts with other complexes of the electron transport chain in entities called supercomplexes or respirasomes that are thought to provide a kinetic advantage by allowing for a more efficient transfer of electrons between the respiratory complexes and their intermediary carriers cytochrome c and coenzyme Q [129,130]. In humans, the respirasome is composed of Complex I, III, and IV in variable stoichiometry, while in yeast it is composed of Complex III and IV in strict 2:2 and 2:1 ratios [61,131,132]. Mutations resulting in COX deficiency affect respirasome biogenesis, which could ultimately lead to complex secondary phenotypes, as discussed elsewhere [133].

4.3.1. Mutations in Complex IV Catalytic Subunits

Generally, when compared to nuclear structural subunits and factors, mitochondrial COX genes are associated with milder and late onset clinical phenotypes [135]. As of today, there are 42 pathogenic mutations reported for MTCO1, 26 for MTCO2, and 24 for MTCO3 [69]. The phenotypes associated with mutations in these subunits are briefly summarized in the paragraphs bellow and are cited from the MITOMAP [69].

The most frequent homoplasmic pathogenic mutations in MTCO1 are associated with prostate cancer, LHON, SNHL (sensorineural hearing loss) and DEAF (maternally-inherited deafness). The most frequent diseases caused by homoplasmic variants are dilated cardiomyopathy and maternally inherited epilepsy and ataxia. Clinical phenotypes associated with heteroplasmic variants include epilepsy partialis continua, Leigh syndrome, asthenozoospermic infertility, MELAS, myoglobinuria, motor neuron disease, Rhabdomyolysis and acquired idiopathic sideroblastic anemia. Additionally, both homoplasmic and heteroplasmic variants can lead to exercise intolerance.

Homoplasmic pathogenic MTCO2 variants are mostly associated with progressive encephalomyopathy, possible susceptibility to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), SNHL, DEAF, and LHON. For example, there are 147 sequences containing the m.7859G>A substitution that causes progressive encephalomyopathy. Less frequent mutations can cause Alpers-Huttenlocher-like, Asthenozoospermia, developmental delay, ataxia, seizure, hypotonia, hepatic failure, myopathy, MELAS, cerebellar and pyramidal syndrome with cognitive impairment, pseudoexfoliation glaucoma, multisystem disorder, Rhabdomyolysis, biliary atresia, and MIDD (maternally-inherited diabetes and deafness).

The most frequent pathogenic MTCO3 variants are homoplasmic and lead to LHON. Other clinical phenotypes associated with mutations in MTCO3 include Alzheimer’s disease, MELAS, Leigh syndrome, cardiomyopathy, exercise intolerance, myoglobinuria, myopathy, asthenozoospermia, failure to thrive, cognitive impairment, optic atrophy, encephalopathy, rhabdomyolysis, and sporadic bilateral optic neuropathy.

4.3.2. Mutations in Complex IV Structural Subunits

In the past two decades, pathogenic mutations that result in COX deficiency have been identified in the structural subunits COX4, COX5A, COX6A, COX6B, COX7B, COX8, and NDUFA4 (Table 5). With the exception of COX7B, patients with described mutations in structural COX subunits are born to consanguineous parents and therefore carry homozygous mutant alleles. Clinical phenotypes include, among others, Leigh or Leigh-like syndrome, encephalopathy, myopathy, and anemia.

Interestingly, COX7B is located in the X chromosome and is the only X-linked subunit of COX. Different heterozygous mutations in COX7B have been described in patients presenting with microphthalmia with linear skin lesions (MLS), a neurocutaneous X-linked dominant male-lethal disorder [136]. In addition to COX7B, MLS has also been associated with mutations in HCCS, the holocytochrome c-type synthase, and in NDUFB11, a subunit of Complex I. Somatic mosaicism and the degree of X chromosome inactivation in different tissues could explain the variability of additional clinical phenotypes that accompany MLS, such as developmental delay, abnormalities of the central nervous system, short stature, cardiac defects, and several ocular anomalies [137]. Indeed, the majority of MLS patients have severe skewing of X chromosome inactivation, probably because during embryonic development, respiratory competent cells multiply faster and outgrow cells harboring mutations in these structural genes [137].

4.3.3. Mutations in Complex IV Assembly Factors

SURF1, the human homolog of yeast SHY1, has been implicated in the maturation of the heme a centers of Complex IV [138]. Mutations in this gene are the most frequent cause of Leigh syndrome stemming from COX deficiency [139]. The first cases of Leigh syndrome caused by SURF1 mutations were described in 1998 [140,141]. Since then, many other cases have been reported. A systematic review by Wedatilake et al. [139] lists 43 records describing 129 cases of Leigh syndrome with SURF1 deficiency caused by 83 different mutations. The authors also performed a study that included about 50 patients, in which the most frequently occurring mutation was L105* (16 homozygous and 11 compound heterozygous) and no specific correlation of genotype to phenotype was established [139]. Besides Leigh syndrome, there are also reports of SURF1 mutations associated with Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease [142].

As already mentioned, Cox10 and Cox15 are required for the conversion of heme b to the heme a of the two redox centers in Cox1 (MTCO1). In S. cerevisiae, cox10 and cox15 mutants have no Complex IV activity [143,144]. Yeast cox10 mutants can be functionally complemented by the human homolog of COX10 [145]. Pathogenic mutations in COX10 and COX15 are associated with Leigh syndrome, cardiomyopathy, and encephalopathy, among others (Table 6), and, typically, such patients have an early fatal outcome due to respiratory failure. However, a single adult patient, a 37-year old woman, was identified with isolated COX deficiency associated with a relatively mild clinical phenotype (myopathy, demyelinating neuropathy, premature ovarian failure, short stature, hearing loss, pigmentary maculopathy, and renal tubular dysfunction) due to compound heterozygous mutations resulting in D336V and R339W substitutions in COX10 [146]. Surprisingly, no COX was detected in blue native gels on mitochondria extracted from the patient’s muscle cells. The mutations were introduced into yeast both individually and in combination, all resulting in the loss of the respiratory capacity, which supported the pathogenicity of the mutations [146].

Table 6.

Human ATP Synthase subunits and theirs yeast homologs.

| ATP Synthase Sector | Human Subunit | Human Gene | Genome in Human | Yeast Subunit | Yeast Gene | Genome in Yeast | pet Mutant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 catalytic barrel | α | ATP5F1A | nuclear | α | ATP1 | nuclear | yes |

| β | ATP5F1B | nuclear | β | ATP2 | nuclear | yes | |

| F1 central stalk | γ | ATP5F1C | nuclear | γ | ATP3 | nuclear | yes |

| ε | ATP5F1E | nuclear | ε | ATP15 | nuclear | yes | |

| δ | ATP5F1D | nuclear | δ | ATP16 | nuclear | yes | |

| Peripheral stalk | b | ATP5PB | nuclear | b | ATP4 | nuclear | yes |

| d | ATP5PD | nuclear | d | ATP7 | nuclear | yes | |

| OSCP | ATP5PO | nuclear | OSCP | ATP5 | nuclear | yes | |

| F6 | ATP5PF | nuclear | h | ATP14 | nuclear | yes | |

| Fo rotor | Atp6 | MT-ATP6 | mitochondrial | Atp6 | ATP6 | mitochondrial | N/A |

| Atp8 | MT-ATP8 | mitochondrial | Atp8 | ATP8 | mitochondrial | N/A | |

| c1 | ATP5MC1 | nuclear | Atp9 | ATP9 | mitochondrial | N/A | |

| c2 | ATP5MC2 | nuclear | |||||

| c3 | ATP5MC3 | nuclear | |||||

| Fo supernumerary | f | ATP5MF | nuclear | f | ATP17 | nuclear | yes |

| 6.8 PL | ATP5MPL | nuclear | i/j | ATP18 | nuclear | no | |

| DAPIT | ATP5MD | nuclear | k | ATP19 | nuclear | no | |

| g | ATP5MG | nuclear | g | ATP20 | nuclear | no | |

| e | ATP5ME | nuclear | e | ATP21 | nuclear | no |

There is also a single case of a long surviving Leigh syndrome patient resulting from compound heterozygous mutations leading to S152* and S344P substitutions in Cox15. The 16 year old patient presented 42% and 22% of residual COX activity in skeletal muscle cells and fibroblasts, respectively. A normal amount of assembled COX holoenzyme was present in cultured fibroblasts, which could account for the slower clinical progression of the disease [147].

Human SCO1 and SCO2 are copper proteins involved in the metalation of MTCO2 [148]. Although both proteins have homologs in yeast, only Sco1 is needed for metalation of Cox2 [149]. A role of Sco1 in assembly of COX is supported by its presence in a Cox2 assembly intermediate [150]. Pathological mutations in SCO1 and SCO2 have been described to result in cardioencephalomyopathy. Gurgel-Giannetti et al. [151] reviewed about 40 patients with mutations in SCO2, the majority presenting with cardioencephalomyopathy while two patients suffered from Leigh syndrome. With the exception of one patient that had a homozygous G193S substitution, all other patients presented the E140K substitution which was found either in homozygosis or in association with a second mutation [151]. Furthermore, mutations in SCO2 have also been associated with Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease [152] and with high degree myopia [153,154].

Additionally, in the past 10 years, pathogenic mutations have been identified in COX assembly factors, products of FAM36A, COX14, PET117, COA5, PET100, COA6, and COA3 with a variety of clinical phenotypes (Table 5). The pathologies were found in infants with either homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations.

4.4. ATP Synthase

The F1Fo-ATP synthase or Complex V is a large multimeric protein complex located in the inner membrane of mitochondria. Its principal function is to phosphorylate ADP to ATP using the energy of the proton gradient formed during oxidation of NADH and succinate [188]. This means of making ATP, historically referred to as oxidative phosphorylation, is reversible, allowing the energy released when the ATP synthase hydrolyzes ATP to be stored as a proton gradient capable of driving other energy-demanding chemical, transport, and physical processes. The mitochondrial ATP synthase consists of three distinct structural components: the F1 ATPase, the peripheral stalk, and a membrane-embedded unit referred to as Fo [189]. In both mammalian and yeast cells, the F1 ATPase is composed of five distinct subunits: three and three subunits, that form a hexameric barrel structure, and the monomeric , , and subunits that constitute the central stalk [190]. The peripheral stalk is composed of four nuclear encoded subunits: b, d, OSCP, and h (yeast) or F6 (human). The membrane-embedded domain is comprised of eight subunits, three of which (Atp6, Atp8, and Atp9) are encoded in the mitochondrial genome of S. cerevisiae [191], but only two (MT-ATP6 and MT-ATP8) in mammalian mitochondria [192]. Atp9 is present in multiple copies in a ring that rotates during catalysis. The number of Atp9 molecules per ring differs depending on the organism. The yeast and human rings consist of ten and eight subunits of Atp9, respectively [193,194,195].

4.4.1. Mutations in ATP Synthase Mitochondrially Encoded Subunits

The first mitochondrial disease caused by an ATP synthase dysfunction was found in patients with mutations in MT-ATP6, a mitochondrial gene encoding a key component of the Fo proton channel [196]. The clinical phenotypes of these patients depend largely on the relative levels of heteroplasmy. For instance, patients harboring an m.T8993G substitution with a 70–90% mutation load often exhibit ‘milder’ syndromes, such as NARP (neurogenic muscle weakness, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa) or FBSN (familial bilateral striated necrosis) [196]. Patients with the same m.T8993G substitution, but with a mutation load exceeding 90–95%, present with a more severe neurological disorder: maternally inherited Leigh syndrome characterized by fatal infantile encephalopathy [196].

The m.T8993G pathogenic mutation in MT-ATP6 was the first reported mitochondrial disease associated with an ATP synthase defect [197]. Since then, more than 40 pathogenic variants have been reported [69]. Four of these, m.T8993G, m.T8993C, m.T9185C, and m.T9185C, constitute most of all known cases, while the remaining variants mostly appear as isolated cases [198]. The clinical presentations of these patients are heterogeneous, with Leigh syndrome and NARP being the most frequently reported (Table 7). Recurrent phenotypes also include Charcot–Marie–Tooth peripheral neuropathy, spinocerebellar ataxia, and familiar upper motor neuron disease. Isolated cases of MLASA (mitochondrial lactic acidosis and sideroblastic anemia), HCM, primary lactic acidosis, 3-methylglutaconic aciduria and optic neuropathy have also been reported [198].

Table 7.

Pathologies resulting from mutations in genes encoding ATP synthase subunits and assembly factors, and their yeast homologs.

| Human Gene | Yeast Gene | Clinical Phenotype | Mutation | Confirmation in Yeast | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT-ATP6 | ATP6 | NARP, FBSN, Leigh syndrome, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disorder, HCM, MLASA | many | [198] 1 | |

| MT-ATP8 | ATP8 | apical HCM, neuropathy | homoplasmic W55* | no | [204] |

| tetralogy of Fallot | homoplasmic G9804A, C8481T, heteroplamic T7501C 3 | no | [205] | ||

| ATP5F1D | ATP16 | metabolic disorders, encephalopathy | homozygous P82L; homozygous V106G 2 | no | [213] |

| ATP5F1E | ATP15 | mild mental retardation, developed peripheral neuropathy | homozygous Y12C | no | [6] |

| ATP5F1A | ATP1 | fatal neonatal encephalopathy | heterozygous R329C | no | [5] |

| ATPAF2 | ATP12 | microcephaly etc | homozygous W94R | yes | [7,211] |

1 Review describing many mutations. 2 In different patients. 3 In the same patient.

Due to the heteroplasmy accompanying mitochondrial deficiencies caused by MT-ATP6 mutations, the pathogenic mechanisms underlying these disorders have been challenging to elucidate. In this respect, homoplasmic S. cerevisiae clones carrying the pathogenic ATP6 mutations have served as a good model for characterizing the etiology of MT-ATP6 diseases. The first modeling in yeast of a pathogenic mutation in ATP6 was done by Rak et al. [199]. These authors have introduced in yeast the equivalent of the T8993G mutation responsible for NARP. Although the ATP synthase was correctly assembled and present at 80% of wild-type levels, the yeast mutant showed poor respiratory growth and mitochondrial ATP synthesis was only 10% of that of the wild-type. The mutant also had lower steady state levels of COX, suggesting a co-regulation of ATP synthase activity and COX expression [199]. Additionally, there is more evidence that the biogenesis of these two enzymes may be coupled. It was recently showed that Atco, an assembly intermediate composed of COX and ATP synthase subunits, namely Cox6 and Atp9, is a precursor and the sole Atp9 source for ATP synthase assembly [200].

Another study showed that a Leigh syndrome causing m.T9191C mutation with an L242P substitution in ATP6 reduced both assembly of the yeast ATP synthase and the efficiency of ATP synthesis by 90% [201]. Based on the biochemical phenotypes of the mutant and of revertants with amino acid substitutions at this position, the proline was proposed to disrupt the terminal -helix causing a displacement of other neighboring helices involved in proton transfer at the Atp6 and Atp9 interface [202]. Additionally, the conformational change induced by the mutations promoted proteolysis of Atp6, thereby accounting for the reduction of assembled ATP synthase. Revertants with replacements of the helix-disrupting proline by threonine or serine completely restored the assembly defect, but only partially the efficiency of proton translocation. These observations, combined with modeling of the interface between the two subunits, suggested that the suppressor mutations did not completely compensate for the displacement of residues involved in release of protons from the Atp9 ring and their transfer to a neighboring aspartic acid residue in Atp6 [202]. These findings are consistent with previous models of the disease, suggesting that certain pathogenic ATP6 mutations do not completely block the proton translocation mechanisms of the Fo domain, but rather disrupt proton transport during rotation of the ring. As the conformational changes in the F1 moiety are induced by rotation of the Atp9 ring, the uncoupling leads to the inability of ATP synthase to harness the energy normally released from the translocation of protons for ATP synthesis [203].

The different biochemical anomalies discerned in the numerous MT-ATP6 pathogenic variants suggest several pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for diseases associated with defects in the ATP synthase [198]. These include decreased holoenzyme assembly, destabilization of the proton pore resulting in mitochondrial membrane potential buildup, impairment of the proton pump leading to decreased membrane potential, reduced ATP synthesis and abnormal sensitivity to the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin [198].

A smaller subset of mitochondrial mutations causing ATP synthase deficiencies has been ascribed to the second mitochondrial gene, MT-ATP8, encoding a subunit of Fo. The first pathogenic mutation in MT-ATP8 was identified in a 16-year-old patient with apical HCM and neuropathy, with a marked reduction in ATP synthase activity in fibroblasts and muscle tissue [204]. Since then, several other patients have been identified with pathogenic MT-ATP8 mutations. One of the patients was a seven-month-old infant diagnosed with tetralogy of Fallot, the most common type of congenital heart defect characterized by ventricular septal defect, pulmonary stenosis, right ventricular hypertrophy and aortic dextroposition [205].

MT-ATP6 and MT-ATP8 genes overlap 46 nucleotides that span 16 codons [206]. On the MITOMAP [69] are presently listed four known pathogenic mutations in this region that contribute to an amino acid change in both genes, and three other variants that have a hypothesized deleterious effect. An ATP synthase deficiency has been associated with an m.C8561G mutation in two siblings with cerebral ataxia and loss of neuromuscular function. The mutation, resulting in P12R and P66A changes in MT-ATP6 and MT-ATP8, respectively, when expressed in homoplasmic myoblasts, reduced cellular ATP by 15% but had only a marginal effect on steady state concentrations of the ATP synthase [207]. Even though there was no obvious decrease in the steady-state concentration of ATP synthase, a substantial increase of an uncharacterized assembly intermediate was noted. Another study reported an m.C8561T mutation with other amino acid substitutions in a patient with a similar biochemical but more severe clinical presentation [208]. Neither studies examined the effect of the singular or combined ATP8 and ATP6 mutations on the yeast ATP synthase.

4.4.2. Mutations in ATP Synthase Nuclear Structural Subunits

At present, only a small number of mitochondrial pathologies have been attributed to mutations in nuclear genes coding for subunits of the ATP synthase and for chaperones that function in assembly of the enzyme. Several studies found that patients with lactic acidosis, persisting 3-methylglutaconic aciduria, cardiomyopathy, and early death were correlated with severe deficiencies in ATP synthase, but the genetic lesions in these studies were not identified [209,210,211]. ATP5F1E and ATP5F1D, the human homologs of the yeast ATP15 and ATP16, code for the ε and subunits, respectively, of the central stalk of F1. A homozygous missense mutation in ATP5F1E was the first reported instance of a patient with an ATP synthase defect stemming from a mutation in a nuclear encoded subunit of the enzyme. The mutation caused mild mental retardation and the patient developed peripheral neuropathy [6]. The mitochondrial synthesis of ATP, the oligomycin ATPase activity and the ATP synthase content were reduced by 60–70%. The residual enzyme with the mutated ε subunit had normal activity, indicating that the primary effect of the mutation was on assembly of the synthase. Interestingly, this mutation, when introduced in the ε subunit of yeast ATP synthase, did not elicit any detectable effect on either the activity of assembly of the enzyme [212]. This suggested that the mutation in the human ε subunit, perhaps because of a weaker physical interaction with the c ring, exerted a deleterious effect on assembly of the human but not of the yeast enzyme [212]. In a more recent report, two patients with homozygous mutations in ATP5F1D were shown to suffer from metabolic disorders in one case and from encephalopathy in another [213]. ATP5F1A, coding for human α subunit of F1, is the third nuclear ATP synthase gene identified in two patients presenting fatal neonatal encephalopathy with intractable seizures [5]. Interestingly, reduced levels of cellular ATP5F1 were also shown to correlate significantly with earlier-onset prostate cancer [214]. Indeed, transitioning from oxidative phosphorylation to anaerobic glycolysis for energy production occurs in many types of tumors, and could explain the pathophysiology of the disease.

None of the patients with mutations in the nuclear ATP synthase genes discussed in this and the next sections exhibit the clinical NARP and Leigh syndrome phenotypes characteristic of patients with mutations in the two mitochondrially-encoded genes of the enzyme.

4.4.3. Nuclear ATP Synthase Assembly Gene Mutations

A substantial number of nuclear gene products of S. cerevisiae are known to regulate and chaperone different steps of ATP synthase assembly [215]. At present, however, the only known human regulatory factors with identified mutations in a small number of patients are TMEM70, a protein essential for ATP synthase assembly and ATPAF2, the homolog of the yeast Atp12 chaperone that interacts with the α subunit of F1 during assembly of this ATP synthase module [216]. TMEM70 does not have a yeast homolog. The phenotypes associated with mutations in TMEM70 and the role of its product in ATP synthase assembly have been reviewed elsewhere [217,218].

A study in which two patients, ascertained to have nuclear mutations that affected mitochondrial ATP synthase assembly, were screened by sequencing human homologs of yeast genes previously shown to affect F1 biogenesis led to the identification in one patient of a mutation in ATPAF2. This patient, diagnosed with lactic acidosis, glutaconic aciduria, encephalomyopathy and a range of different developmental problems, was found to have a homozygous W94R amino acid substitution that resulted in severe deficits of ATP synthase in the heart, liver and to a lesser degree in skeletal muscle, resulting in death at 14 months of age [219]. The deleterious effect of the W94R substitution in a highly conserved region of ATPAF2 on ATP synthase assembly was confirmed by Meulemans et al. [7], who showed that the wild-type, but not the mutant human gene, restored the ATP synthase activity of a yeast atp12 mutant. The atp12 mutant also failed to be complemented by the yeast ATP12 harboring the equivalent W102R mutation expressed from a low copy yeast CEN, but not from a high-copy plasmid. The rescue by the W102R, however, depended on the presence of wild-type FMC1, a gene implicated in regulating the activity of yeast Atp12 [220].

4.5. Coenzyme Q

Coenzyme Q (ubiquinone, CoQ or CoQ10 in humans) is a lipophilic redox molecule found in virtually all eukaryotic organisms and most bacteria. It is composed of a quinone ring connected to a polyisoprenoid side chain of variable length. Coenzyme Q serves several crucial functions in mitochondria, including transfer of electrons from Complexes I and II to Complex III, acting as an essential cofactor in the uncoupler protein mediated transfer of protons to the matrix, prevention of lipid peroxidation, biosynthesis of uridine, beta-oxidation of fatty acids, and binding to and regulating the permeability transition of the voltage-dependent anion channel [221].

The CoQ biosynthetic pathway in eukaryotes has been studied in yeast coq mutants arrested at different steps of the pathway [222,223]. Like human cells, yeast relies on de novo synthesis of CoQ; and any deficiency in the biosynthetic pathway results in a growth arrest on media containing non-fermentable carbon sources [3,224]. Most enzymes of the CoQ biosynthetic pathway are organized in a multi-subunit complex known as the CoQ synthome [222,225]. The CoQ synthome is spatially linked to the endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria contact sites, providing optimal CoQ production with an efficient intracellular distribution as well as minimizing the escape of toxic intermediates [226,227]. Expression of functional CoQ in yeast depends on at least 14 nuclear gene products (Coq1-Coq11, Yah1, Arh1, and Hfd1), all located in mitochondria [227].

CoQ biosynthesis is achieved by three separate and highly conserved pathways:

(1) Synthesis of the quinone ring from 4- hydroxybenzoate (4HB), derived from tyrosine [228], or from p-aminobenzoic acid (pABA), in yeast but not in humans [225,227,229]. The early steps of 4HB formation are still to be determined but deamination of tyrosine starts with Aro8 or Aro9 catalyzed transamination [230]. The formation of the final intermediate 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (4 HBz) is catalyzed by the aldehyde dehydrogenase Hfd1 [230,231].

(2) Synthesis of isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylally pyrophosphate (DMAPP), catalyzed by Coq1 in yeast [232] and PDSS1 and PDSS2 in humans.

(3) Prenylation of parahydroxybenzoate by the polisoprenyl transferase Coq2 [233] and further modifications of the benzoquinone ring by hydroxylases and methyl transferases. The isoprenoid side chain is important for proper CoQ localization at the mid-plane of phospholipid bilayers. Yeast coenzyme Q contains 6 isopentenyl units (CoQ6) while in humans the major coenzyme Q isoform contains 10 isopentenyl units (CoQ10).

The benzoquinone head group is modified by hydroxylations catalyzed by Coq6 and Coq7 [234,235,236], methylation of the resultant hydroxyls by the Coq3 methyl transferase [237], methylation of the ring by Coq5 [238] and a decarboxylation step catalyzed by a still unidentified enzyme of this pathway. Other gene products linked to coenzyme Q biosynthesis and utilization include Coq4 and Coq9, that have been assigned a role in assembly and stability of the CoQ synthome, and Coq8, a member of a protein family that includes kinases and ATP-dependent ligases. Coq8 has been implicated in the phosphorylation state of Coq3, Coq5 and Coq7 [239,240,241]. The steady-state concentrations of Coq4, 6, 7, and 9 are markedly decreased in a coq8 null mutant, as a result of which assembly of the CoQ synthome is abrogated [242]. The coq8 null mutant, however, contains a complex of Coq6 and Coq7 thought to be an early intermediate of the synthome [243]. Coq10 is a low molecular weight member of the START protein family that binds coenzyme Q. Although Coq10 is required for respiration, its synthesis is only partially affected in log but not in stationary phase yeast cells, suggesting that its function is related to the delivery of coenzyme Q from the synthome located at the endoplasmic-mitochondrial contact sites to the regions of the inner membrane containing the respiratory chain complexes [226,244]. The respiratory deficiency of coq10 mutants is partially rescued in a coq11 mutant, which codes for a component of the synthome that has been proposed to down- regulate the synthesis of coenzyme Q [244]. Coq11 (human NDUFA9), a separate protein in yeast, is a component of the CoQ synthome [245] and appears to regulate its formation and stability [244]. CoQ yeast and human genes are listed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Coenzyme Q genes required for functional expression of CoQ and their yeast homologs.

| Yeast Gene | Human Gene |

|---|---|

| COQ1 | PDSS1 |

| COQ1 | PDSS2 |

| COQ2 | COQ2 |

| COQ3 | COQ3 |

| COQ4 | COQ4 |

| COQ5 | COQ5 |

| COQ6 | COQ6 |

| COQ7/CAT5 | COQ7 |

| COQ8/ABC1 | COQ8A |

| COQ8/ABC2 | COQ8B |

| COQ9 | COQ9 |

| COQ10 | COQ10A, COQ10B |

| COQ11 | NDUFA9 |

Mutations in COQ Genes

CoQ10 deficiency, a biochemical lesion first described over three decades ago by Ogasahara et al. [246], is subdivided into primary CoQ10 deficiency, when caused by a pathogenic mutation in one of the genes required for the coenzyme’s biosynthesis, and secondary CoQ10 deficiency, when the mutated gene is not directly related to the biosynthetic pathway [247]. Of the two, the latter has been reported more frequently in patients, with phenotypes including mitochondrial myopathies, mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome and multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MADD) [248]. However, the pathogenic mechanisms linking these disorders with the observed CoQ10 deficiency have yet to be elucidated.

Primary CoQ10 deficiency is far rarer [248]. Emmanuele et al. [247] first classified the clinical manifestations of primary CoQ10 deficiency into five distinct phenotypes: encephalomyopathy, isolated myopathy, nephropathy, infantile multisystemic disease, and cerebellar ataxia. However, it has been argued that this subdivision should be updated, as new cases have been discovered with novel mutations presenting a wide range of other clinical phenotypes, as well as different combinations of the previously described symptoms [248]. To date, mutations in ten genes have been associated with primary CoQ10 deficiency (Table 9).

Table 9.

Pathologies resulting from mutations in Coenzyme Q genes and their yeast homologs.

| Human Gene | Yeast Gene | Clinical Phenotype | Mutation | Confirmation in Yeast | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDSS1 | COQ1 | infantile multisystemic disease | homozygous D308E | yes | [261] |

| PDSS2 | COQ1 | infantile multisystemic disease, SRNS, LS, hepatocellular carcinoma | compound heterozygous Q322*, S382L | yes | [262] |

| COQ2 | COQ2 | SRNS, SRNS with encephalomyopathy resembling MELAS, fatal infantile multisystemic disease | homozygous Y297C | yes | [268] |

| COQ4 | COQ4 | LS, cerebellar atrophy, lactic acidosis, etc. | many | [263,269,270] 1 | |

| COQ5 | COQ5 | cerebellar ataxia, dysarthria, myoclonic jerks | biallelic 9590 bp duplication | no | [250] |

| COQ6 | COQ6 | SRNS, infantile multisystemic disease | many | [264] 1 | |

| COQ7 | COQ7 | spasticity, sensorineural hearing loss etc. | homozygous V141E; homozygous L111P; compound heterozygous R107W, K200Ifs*56 2 | no | [272,273,274] |

| COQ8A | COQ8 | ARCA, seizures, dystonia, spasticity | many | [248] 1 | |

| COQ8B | COQ8 | SRNS | many | [248,276] 1 | |

| COQ9 | COQ9 | infantile multisystemic disease, Leigh-like Syndrome, microcephaly | many | See main text |

1 Review describing many mutations. 2 In different patients.

With the exception of Coq3, patients have been reported with mutations in all other components of the CoQ multi-subunit complex [249,250]. These patients can be treated with CoQ10 supplementation with partial success. Early treatment based on early diagnosis is critical for the best outcome [251]. Because of its poor solubility, CoQ10 is only administrated in oral formulations, despite its destitute bioavailability [252,253]. Similarly, uptake of CoQ6 in yeast coq mutants is inefficient [254,255].

Due to the striking homology between human and yeast COQ genes [227], studies of CoQ proteins in S. cerevisiae may provide insight into human homologs, leading to the identification of residues critical for protein function and, therefore, with higher pathogenic potential [256]. Indeed, yeast coq3, coq8, coq9, and coq10 mutants are complemented by the human counterparts [239,257,258,259], while yeast coq5 null mutants are complemented by human COQ5 combined with overexpression of COQ8 [260]. Furthermore, studies of pathogenic mutations in COQ genes have been validated in yeast coq1 [261], coq2 [261,262], coq4 [263], coq6 [264], coq8 [241], and coq9 mutants [265].

PDSS1 and PDSS2, both human homologs of yeast COQ1, encode two proteins that form a heterotetramer that catalyzes the elongation of the isoprenoid side chain. PDSS1 does not complement the yeast coq1 null mutant [261]. Mutations in both of these genes lead to infantile multisystemic disease, a heterogeneous disorder characterized by psychomotor regression, encephalopathy, optic atrophy, retinopathy, hearing loss, renal dysfunction and heart valvulopathy [247,261]. Mutations in PDSS2 have been associated with additional phenotypes, including Leigh syndrome, steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS)—an atypical manifestation for other mitochondrial disorders but quite common for CoQ10 deficiencies; and hepatocellular carcinoma [247,266,267]. It has been shown that the downregulation of PDSS2 can induce a shift from aerobic metabolism to anaerobic glycolysis, as well as increased chromosomal instability—a possible pathogenic mechanism for hepatocellular carcinoma [267].

Pathogenic mutations in COQ2, encoding a parahydroxybenzoate-polyprenyltransferase that catalyzes the addition of the isoprenoid chain to the benzoquinone ring, were the first to be associated with primary CoQ10 deficiency [268]. Pathogenic mutations in human COQ2 have been confirmed in yeast by complementation studies of the yeast coq2 null mutant [261,262]. Clinical manifestations of these mutations include isolated SRNS, SRNS with encephalomyopathy resembling MELAS, fatal infantile multisystemic disease, and late-onset multiple-system atrophy and retinopathy [247,248].

The first pathogenic mutation in COQ4, required for the stability of the CoQ synthome, was found as a haploinsufficiency, with a phenotype similar to that of a heterozygous yeast mutant [263]. The patient presented facial dysmorphism and muscle hypotonia, which improved significantly with CoQ10 supplementation [263]. Since then, a total of 19 patients, all infants, have been identified with mutations in COQ4, with clinical phenotypes that included cerebellar atrophy, lactic acidosis, seizures, muscle weakness, cardiomyopathy, ataxia, and Leigh syndrome [269,270]. None of the patients suffered from nephropathy, typically found in primary CoQ10 deficiency.

To date, only three cases of pathogenic mutations in the methyltransferase encoded by COQ5, have been recorded. The affected individuals were three female siblings presenting with non-progressive cerebellar ataxia, dysarthria, and mild to moderate cognitive disability [250]. Two of the three siblings exhibited myoclonic jerks and generalized tonic-clonic seizures in adolescence and early 20s. Next-generation sequencing identified a tandem duplication of the last four exons of COQ5, while biochemical studies showed a 33% reduction of CoQ10 in skeletal muscle—sufficient to sustain a basal rate but insufficient to reach maximal efficiency of respiration [250].

Mutations in COQ6, encoding an enzyme involved in hydroxylation and deamination reactions during CoQ biosynthesis, have been primarily associated with SRNS [264], characterized by significant proteinuria with resulting hypoalbuminemia and edema and presenting with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis [248]. The pathogenicity of the first six COQ6 mutations in human patients was confirmed by complementation studies using the yeast coq6 null mutant [264]. Three patients harboring a COQ6 mutation also suffered from infantile multisystemic disease [247]. Based on in vitro and in vivo studies of renal podocyte cell lines, it has been hypothesized that the pathogenicity of COQ6 mutations relates to respiratory chain deficiency, ROS generation, disruption of podocyte cytoskeleton and induction of cellular apoptosis, ultimately resulting in SRNS [271].

Three cases of primary CoQ10 deficiency caused by mutations in COQ7, responsible for the penultimate step of CoQ biosynthesis, have been reported in two children with similar phenotypes of spasticity, sensorineural hearing loss and muscle hypotonia; and a third more severe case of fatal mitochondrial encephalo-myo-nephro-cardiopathy, persistent lactic acidosis, and basal ganglia lesions [272,273,274]. In one of the patients, treatment with the unnatural biosynthesis precursor 2,4-dihydroxybenzoate (DHB), a hydroxylated variant of the native 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (4-HB) normally modified by COQ7, increased CoQ10 levels and partially restored mitochondrial respiration [273].

The human genes ADCK3 and ADCK4, also known as COQ8A and COQ8B, are both homologs of yeast COQ8. Mutations in COQ8A have mostly been associated with autosomal recessive progressive cerebellar ataxia (ARCA), often accompanied by childhood onset cerebellar atrophy, with and without seizures, and exercise intolerance [241,248,275]. The pathogenic nature of the ADCK3 mutations was corroborated using the yeast counterpart system [241]. However, isolated cases of psychiatric disorders, seizures, migraines, and dysarthria have been reported [248]. Studies of fibroblast cell lines isolated from ARCA patients showed an increased sensitivity to oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide, high levels of oxidative stress and changes in mitochondrial homeostasis as a result of loss-of-function mutations in COQ8A [275]. Interestingly, concomitant with the upregulation of ROS production, increased respiratory supercomplex stability and basal respiratory rate were observed, suggesting that the loss of ADCK3 could result in a compensatory elevation of respirasome formation [275]. The relationship between the two human paralogs COQ8A and COQ8B is unclear. However, pathogenic mutations in the two genes lead to completely different clinical phenotypes. Indeed, all patients with COQ8B mutations suffered from SNRS, with only a single case of neurological involvement reported [248,276].

Primary CoQ10 deficiency caused by mutations in COQ9 is extremely rare, with only seven cases from four families having been reported. The COQ9 gene product binds to the polyprenyl tail of CoQ intermediates with high specificity, allowing the modification of the benzene ring by Coq7 and other components of the CoQ synthome [259,277]. The reported cases include an infant suffering from lethal lactic acidosis, seizures, cerebral atrophy, HCM, and renal dysfunction [248,265], a boy diagnosed with neonatal Leigh-like syndrome who died at 18 days of age from cardio-respiratory failure [278], four siblings with an unknown and ultimately lethal condition characterized by dilated cardiomyopathy, anemia, abnormal appearing kidney, and suspected Leigh syndrome [279]; and a nine-month old girl presenting with microcephaly, truncal hypotonia, and dysmorphic features [280].