Abstract

This unit describes the protocol to detect and quantify RNA phosphorothioate (PS) modifications in cellular RNA samples. Starting from the solid-phase synthesis of phosphorothioate RNA dinucleotides, followed by purification with reverse-phase HPLC, we prepared phosphorothioate RNA dinucleotide standards for UPLC-MS and LC-MS/MS methods. The RNA samples extracted from cells with TRIzol reagent were digested with a mixture of nuclease enzymes and subjected to analysis by mass spectrometry. First, we employed UPLC-MS to identify the RNA PS modification. Next, we optimized the LC-MS/MS method to further quantify the frequency of RNA PS modification in a series of model cells.

Keywords: nucleic acids, RNA phosphorothioate modification, UPLC-MS, LC-MS/MS

INTRODUCTION

Post-transcriptional modifications of cellular RNAs play important roles in both healthy and abnormal cells (Nachtergaele and He, 2017; Jonkhout et al., 2017). Over 160 distinct post-transcriptional RNA modifications have been identified, with mass spectrometry serving as one of the main methods to analyze the RNA epitranscriptome analysis (Kowalak et al., 1993; Mcluckey et al., 1992; Basanta-Sanchez et al., 2016; Chan et al., 2010). Emerging studies have linked RNA modifications to various diseases such as cancer and neurological disorders (Jonkhout et al., 2017). We recently reported the first modification affecting the phosphate group in RNA backbone, the phosphorothioate (PS) modification (Wu et al., 2020). The PS modification had previously been discovered in bacterial DNA (Wang et al., 2007; Tong et al., 2018) and more recently in the DNA of archaea (Xiong et al., 2019). In contrast to the DNA PS modification, we found that the RNA PS modification also exists in eukaryotes. GpsG is the most frequently modified dinucleotide and it exists exclusively in the Rp configuration, quantified with liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). By knocking out the DndA gene in E. coli, we showed that the DndA-E clusters that regulate DNA PS modification also play roles in the pathway of the RNA PS modification. We also demonstrated that the GpsG modification locates on rRNA in E. coli, L. lactis, and HeLa cells, and it is not detectable in rRNA-depleted total RNAs from these cells (Wu et al., 2020).

The PS-modified backbone is more stable against nuclease degradation than the native phosphodiester backbone. Therefore, PS-linked oligonucleotides are of central importance for therapeutic applications of nucleic acid-based medicines that include microRNA (miRNA), small interfering RNA (siRNA), and antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) (Dunbar et al., 2018). Most of the aforementioned classes of oligonucleotide therapeutics, which either have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or are currently in clinical trials, utilize PS modification to improve metabolic stability and cellular uptake (Stein and Castanotto, 2017; Purcell and Hengge, 2005). The resistance of the PS moiety to nuclease digestion is also the reason why we can detect this modification in cellular RNAs. In our protocol, we digested RNA samples extracted from cells using a nuclease enzyme mixture, after which the phosphodiester groups are hydrolyzed whereas PS groups remain intact. As a result, the anticipated PS-modified dinucleotides can be detected by mass spectrometry aided by synthetic standards.

With UPLC-MS, we identified several RNA PS dinucleotide modifications in a sequence-specific manner in various types of cells. Next, we chose to quantify the Rp-GpsG moiety with LC-MS/MS in total RNAs, because it is the most frequently occurring RNA dinucleotide PS modification in the samples we tested, and also exists across prokaryotes and eukaryotes. We then showed that the Rp-GpsG modification is present in rRNA of E. coli, L. lactis and HeLa cells. This fact accounts for its high frequency as rRNA makes up ~80 % of total cellular RNA. Likewise, we proposed that other PS dinucleotide modifications, albeit with lesser frequencies in total RNAs, may be enriched in other classes of cellular RNAs. This protocol unit provides detailed methods to investigate the RNA PS modification in total RNAs as well as other subsets of RNAs, which may promote research regarding the biochemical significance of the RNA PS modification.

BASIC PROTOCOL 1

SYNTHESIS, PURIFICATION, AND CHARACTERIZATION OF RNA PHOSPHOROTHIOATE DINUCLEOTIDES

It has been demonstrated previously that the PS backbone is well compatible with solid-phase synthesis conditions and fluoride treatment (Kostov et al., 2019). All of the oligonucleotides are chemically synthesized at 1.0 μmol scale using the Oligo-800 DNA solid-phase synthesizer. The system is protected with helium gas. All the reagents are purchased from ChemGenes. To understand the process of oligonucleotide synthesis, one must appreciate the design of phosphoramidites. Phosphoramidtes are normal nucleotides that are engineered with specific protecting groups such as tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) at the 2’-OH positions and 4,4’-dimethoxytrityl (DMTr) at the 5’-OH positions. The synthesis proceeds in the 3’ to 5’ direction and adds one nucleotide per synthesis cycle. The cycle consists of four main steps: detritylation, coupling, capping and oxidation. Phosphoramidite oligo synthesis is performed on control-pore glass (CPG-1000) immobilized with the appropriate nucleoside through a succinate linker. After the trityl group is removed by 3% trichloroacetic acid in dichloromethane, the next phosphoramidite (0.1 M) gets activated and incorporated using 0.25 M 5-ethylthio tetrazole (ETT) in acetonitrile. The phosphoramidites are dissolved in anhydrous acetonitrile at a concentration of 0.1 M. This coupling reaction lasts for 6 min on the synthesis column. Acetic anhydride and 1-methylimidazole in tetrahydrofuran and pyridine are used for the capping step. To synthesize the phosphorothioate bonds, the sulfurizing reagent, 3-((N,N-dimethyl-aminomethylidene)amino)-3H-1,2,4-dithiazole-5-thione (DDTT), is used in the oxidation step instead of the regular iodine solution to install the phosphorothioate linkages at specific positions. The oligonucleotides are prepared in DMT off form. After synthesis, the oligos are cleaved from the solid support and fully deprotected with concentrated ammonium hydroxide solution at room temperature for overnight. The solution is evaporated to dryness by Speed-Vac concentrator and desilylated with 125 μL triethylamine trihydrofluoride in 100 μL DMSO at 65 °C for 2.5 hours. The resulting dinucleotide is desalted with Waters Sep-Pak C18 cartridge using 2 M TEAA as equilibration buffer, and 50% Acetonitrile in H2O as the final eluent.

Materials

Acetonitrile (CH3CN), anhydrous (ChemGenes, Cat #: RN-1447)

Protected RNA phosphoramidites (ChemGenes, rA-CE Cat #: ANP-5671, rG-CE Cat #: ANP-5673, Ac-rC-CE Cat #: ANP-6676, rU-CE Cat #: ANP-5674)

Automated solid-phase oligonucleotide synthesizer

2.0 M triethylammonium acetate (TEAA) buffer, pH 7.0

3% Trichloroacetic acid in dichloromethane (ChemGenes, Cat #: RN-1462)

3-((N,N-dimethyl-aminomethylidene)amino)-3H-1,2,4-dithiazole-5-thione (DDTT) solution (0.1 M) in Pyridine:acetonitrile (v/v 9:1) (ChemGenes, Cat #: RN-1689)

5-Ethylthio-1H-tetrazole (ETT) in acetonitrile solution (0.25 M) (ChemGenes, Cat #: RN-1466)

CapA (Acetic Anhydride in THF) (ChemGenes, Cat #: RN-1458) and CapB (16% N-Methylimidazole in THF) (ChemGenes, Cat #: RN-7776) solutions

Argon

Screw-cap tubes or vials

CPG 500 Å solid support ((ChemGenes, Cat #: N-6103–05)

Sep-Pac C18 columns for desalting (Waters, Ref #: 043239115A)

Reverse phase-HPLC column: C18 column

HPLC system with detector at 260 nm

Acetonitrile (CH3CN), HPLC grade (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat #: 34851–4L)

Reverse phase HPLC buffer A: 20 mM TEAA (triethylammonium acetate, pH 7.1)

Reverse phase HPLC buffer B : 50% 20 mM TEAA in acetonitrile.

Lyophilizer

Speed-vac evaporator

Solid Phase Synthesis

-

1

Dissolve RNA phosphoramidites in anhydrous acetonitrile at a concentration of 0.1 M.

-

2

Perform automated solid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis for phosphorothioate RNAs employing the Oligo-800 DNA synthesizer (Haruehanroengra et al., 2017) with regular phosphoramidites in DMTr-off mode using an appropriate column (e.g., on a 1- μmol scale CPG 500 Å) with two filters that hold the solid support CPG where the oligonucleotide synthesis takes place in the column.

-

3

After completion of the assembly, remove the column and dry it by connecting the column to a house vacuum for 2 minute to remove the remaining CH3CN.

Remove Nucleobase and Backbone Protecting Groups and Purify Samples

-

4

Transfer the RNA product on the glass beads into a screw-cap tube or vial, add 1 mL of concentrated ammonium hydroxide, and flip the tube overnight at room temperature to cleave the dinucleotide off the glass beads as well as remove all nucleobase and backbone-protecting groups.

-

5

Transfer the supernatant to a new tube while leaving the glass beads behind. Wash the glass bead residues twice with 200 μL deionized water and combine the solution. This step ensures higher product yield.

-

6

Evaporate the solution to dryness using a speed-vac system. This step usually takes 3–4 hours without heating.

-

7

Dissolve the dry residue in 100 μL of DMSO by vortexing (1–2 min), then add 125 μL of triethylamine trihydrofluoride to the tube, mix the solution thoroughly and heat the vial at 65 °C for 2.5 hours using a heating block. A screw-capped vial is required to secure the cap during heating.

-

8

After heating, cool down the vial on ice and add 25 μL 3 M sodium acetate and 0.75 mL deionized water, mix well with vortex. The usual −80°C ethanol precipitation step for oligonucleotide purification is skipped as this protocol prepares dinucleotides which may not precipitate well. Instead, desalting with a C18 column is performed to protect the HPLC column from the fluoride reagent from step 7.

Desalt RNA Strands with Sep-Pac C18 Columns

-

9

To pre-wash the column, elute acetonitrile (0.5 mL), D. I. water (1.0 mL) and 2.0 M TEAA buffer (0.5 mL, pH = 7.0) one by one to the Waters Sep-Pac C18 desalting columns, push with air to drain the solution slowly if necessary. Keep the TEAA buffer inside the column up to the filter level. Prepare 2-mL autoclaved vials to collect all the eluent.

-

10

Load the RNA in step 8 to this pre-washed column, using gravity to drain this column.

-

11

When the sample solution is down to the filter level, load deionized water 1mL at a time for a total of three times (3 mL total) and adjust the air pressure on top of this column to control the flow rate at 1 drop per 2 seconds.

-

12

Add 50% acetonitrile in water (1 mL) to elute the RNA from the column, keeping the flow rate at 1 drop per 2 seconds.

-

13

Use a Nanodrop-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a wavelength of 260 mm to evaluate the concentration of all vials with the eluent from this column to make sure that the desired RNA is collected. Usually, the desired RNA is collected with the highest concentration in the first eluent with 50% acetonitrile in water.

-

14

Evaporate the acetonitrile in a speed-vac system. The purity of the dinucleotide standards is assessed with an analytical HPLC, using conditions described below which are usually sufficient as standards in UPLC-MS analysis.

HPLC purification for stereo-pure RNA PS standards

To further quantify the GpsG dinucleotides and study the stereochemistry of the phosphorothioate modification, we purified stereoisomers of GpsG with a reversed-phase HPLC column.

-

15

Purify the desalted GpsG dinucleotides with the prep-scale reverse-phase HPLC. Set the flow rate at 6 mL/min using the Ultimate XB-C18 column from Welch (10 μm spherical particle and 21.2 × 250 mm in size). Buffer A was 20 mM TEAA (triethylammonium acetate, pH 7.1), and buffer B was 50% 20 mM TEAA in acetonitrile, with a programmed gradient from 5% B to 100% B in 25 minutes. The same solvents and gradient can be applied on an analytical HPLC for quality control with an analytical C18 column and a flow rate of 1 mL /min.

-

16

After lyophilizing overnight, desalt the two stereoisomers of GpsG with a Waters Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (see protocol above) for further experiments.

-

17

The Rp-GpG and Sp-GpsG configurations were assigned with 31P NMR on a Bruker 500 MHz NMR spectrometer. The HPLC peaks with shorter and longer retention times correspond to the Rp-GpG and Sp-GpsG configurations, with chemical shifts of 56.67 ppm and 55.89 ppm on 31P NMR, respectively.

BASIC PROTOCOL 2

DIGESTION OF RNA SAMPLES EXTRACTED FROM CELLS

The bacterial total RNAs from E. coli and L. lactis were extracted with the hot phenol extraction method using the standard protocol (Dong et al., 2018). The total RNAs from eukaryotic cells, such as Drosophila Melanogaster, S2 cells, mouse liver, HeLa, and HCT116, were extracted with TRIzol reagent (Liu and Harada, 2013). The Pure Link™ RNA mini kit by Invitrogen can also be used to extract total RNAs from a wide variety of cells.

The total RNAs in the following study were digested with Nuclease Enzyme Mix from New England Biolabs (NEB). In the previous publication, we conducted kinetic studies of the enzymatic digestion of 5’-CCCGpsGUUUA-3’ with different time periods of incubation at 37 °C. We showed that the 45-minute incubation time at 37 °C is the optimal condition for our purpose as the normal phosphodiester bonds are completely cleaved while the digestion of phosphorothioate bonds is not significant under this condition (Wu et al., 2020).

Materials

Cells of choice, typically 107-108 cells are used for RNA extraction.

Acid-Phenol:Chloroform, pH 4.5 (with IAA, 125:24:1) (Invitrogen, Cat #: AM9720)

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Cat #: 15596026)

Pure Link™ RNA mini kit (Invitrogen, Cat #: 12183018A)

Nuclease Enzyme Mix (New England Biolabs, Cat #: 0649S)

Heat block or thermal cycler

−20 °C freezer

RNA digestion with a nuclease enzyme mix

Grow cells of your choice to 107-108 and extract the total RNAs from cells. Typically, the hot phenol extraction method is used for extracting bacterial total RNAs and TRIzol extraction for eukaryotic cells. For TRIzol extraction on cells grown in suspension, pellet cells by centrifuge at 300 g for 5 min. Add 1mL of TRIzol reagent to lyse the cell pellet and incubate the homogenized sample at room temperature for 5 mins. Add 0.2 mL of chloroform, vortex thoroughly and incubate at room temperature for 5 mins, followed by centrifuging sample at 12000 g for 10–15 mins at 4 °C. Transfer the supernatant into a RNase free 1.5 mL tube and add equal amount of iso-propanol, mix thoroughly and incubate at room temperature for 10 mins, followed by centrifuge at 12000 g for 10 mins at 4 °C. Discard the supernatant and add 1 mL of 75% ethanol to wash the RNA pellet, centrifuge at 7500 g for 5 mins at 4 °C, and repeat the wash step one more time. Discard the supernatant and air dry the RNA pellet at room temperature. Re-disslove the RNA in DEPC-treated water and check concentration. The Pure Link™ RNA mini kit can also be applied to a wide variety of cells for RNA extraction.

Nuclease Enzyme Mix (from New England Biolabs) was used for digesting cellular RNAs. The nuclease digestion reaction was performed according to the NEB’s protocol with defined 45 minutes incubation time at 37 °C. After heating, put the vials in a −20 °C freezer to stop the reaction.

The digested sample may be stored at −20 °C before being subjected to mass analysis.

BASIC PROTOCOL 3

MASS SPECTROMETRY FOR DETECTION AND QUANTIFICATION OF RNA PS MODIFICATION

LC-MS/MS has been widely used as a sensitive technique for the detection and quantification of nucleic acid modifications (Kowalak et al., 1993; Mcluckey et al., 1992; Basanta-Sanchez et al., 2016). Synthetic Rp-GpsG prepared with basic protocol 1 was used to develop the LC-MS/MS method. The LC retention time, the isotopic pattern, ion fragments, and ratios in the digested total RNA samples match with the data from our synthetic Rp-GpsG 643.084>227.056, 643.084>150.091, 643.084>133.125 in a negative electrospray ionization (ESI-) mode.

Materials

Dinucleotide standards prepared with basic protocol 1

Digested RNA samples from basic protocol 2

RNase-free water with 0.01% formic acid

Acetonitrile, for UPLC and mass spectrometry

Waters XEVO TQ-S triple quadruple mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, USA)

Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 guard column, 2.1× 5 mm, 1.8 μm

Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000)

UPLC coupled with a diode array detector (Agilent)

LC-MS equipped with a DAD detector for quality control of the standards

Modern UPLC coupled with a diode array detector is capable of measuring the extinction coefficient with a high degree of accuracy and reproducibility. To facilitate the development of LC-MS/MS method and the quality control of the synthetic GpsG standards, a UPLC coupled with a diode array detector is employed to determine the extinction coefficient of Rp- and Sp-GpsG and measure the concentration of standards once its extinction coefficient is determined.

-

1

Stereo-pure Rp- and Sp-GpsG were prepared with basic protocol 1 and the solid samples were accurately weighed with Mettler Toledo XPR26DR Micro-Analytical Balance. 0.5 mg or more of each standard is recommended to achieve significant numbers of three. The value of accurate concentration in μg/ml was thus calculated. The appropriate concentration of the standard is around 100 μM.

-

2

Based on the measured units of molar absorptivity (mAU), the extinction coefficient of Rp- and Sp-GpsG at 254 nm was calculated with the equation Ɛ=A*s/(l*c*t), where A is the reading of absorbance integrated over time in the unit of mAU*s, l is the length of the chamber which is 1 cm in our instrument, t is the time of the injected sample spent in the detector which is equal to the injection volume divided by the flow rate, and c is the concentration of standard measured in the above step.

-

3

Evaluate the quality and quantity of the standards, which are usually kept in aliquot solutions in a −20 °C freezer, using the UPLC-MS-DAD method before the mass spectrometry analysis in the following sections. The parameters to check are the mAU*s value, the retention time, mass and any other impurity peaks in the UPLC trace.

UPLC-MS for identifying RNA PS modification

-

4

The digested samples from basic protocol 2 were lyophilized overnight and reconstituted in 100 μL of RNAse-free water with 0.01% formic acid prior to UPLC-MS/MS analysis.

-

5

The UPLC-MS was carried out on a Waters XEVO TQ-S (Waters Corporation, USA) triple quadruple mass spectrometer, equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source maintained at 150 °C and a capillary voltage of 0.8 kV. Nitrogen was used as the nebulizer gas, which was maintained at 7 bars pressure, at a flow rate of 1000 l/h and a temperature of 500 °C.

-

6

By comparing the retention time and mass values of the standards and those from the digested RNA samples, UPLC-MS/MS is used to identify the RNA PS modifications in sample RNAs. Using concentrations of the standards that are estimated by the A260 absorbance on Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000), the UPLC-MS/MS may also be used to analyze the abundance of RNA PS modification qualitatively. For quantitative purpose, accurately weighed stereo-pure PS standards and LC-MS/MS analysis are required as described below.

LC-MS/MS for quantifying RNA PS modification

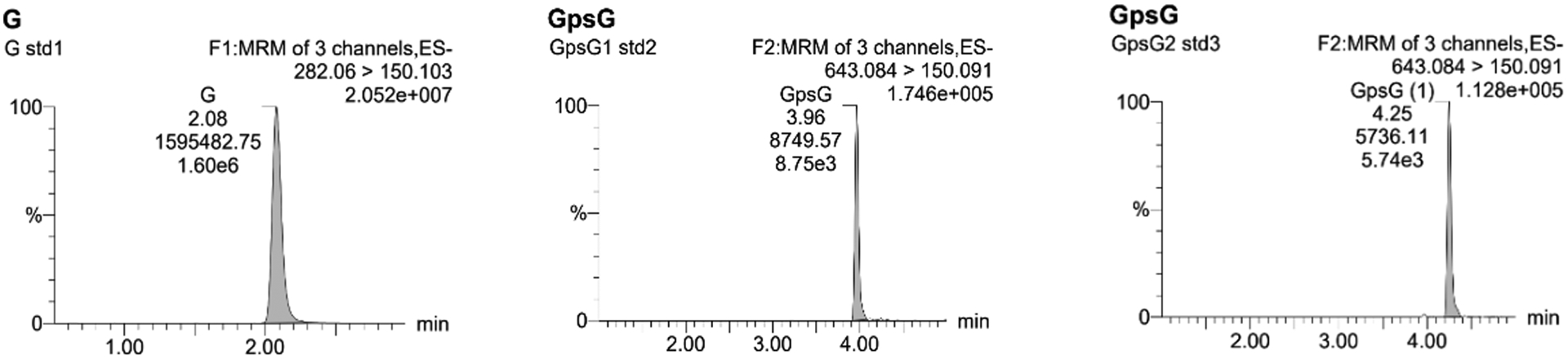

UPLC-MS/MS analysis was performed in ESI negative-ion mode using multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) from ion transitions for GpsG and G. For instance, mass fragments of 643.08>227.06, 643.08>150.09, 643.08>133.12 for Rp-GpsG were observed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mass fragments of GpsG.

-

7

Use a Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 guard column, 2.1× 5 mm, 1.8 μm attached to an HSS T3 column, 2.1×50 mm, 1.7 μm for the separation. Mobile phases used should include RNase-free water (18 MΩ cm−1) containing 0.01% formic acid (Buffer A) and 50:50 acetonitrile in Buffer A (Buffer B).

-

8

Elute the digested nucleotides at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min with a gradient as follows: 0–2 min, 0–10% B; 2–3 min, 10–15% B; 3–4 min, 15–100% B; 4–4.5 min, 100 %B. The total run time is 7 min. Keep the column oven temperature at 35 °C, and inject 10 μL sample. Three injections were performed for each sample.

-

9

Acquire Rp-GpsG or Sp-GpsG analyte data in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode using Waters Masslynx 4.1 software. MS conditions for individual analytes were optimized directly from the syringe pump. The optimization was performed using 100 pg/ul solution of GpsG. Optimizations and analyses have been performed in negative ionization mode to maximize the number of fragmentation reactions. The calibration curves were prepared by spiking known concentrations (0.01–50 pg/ul) of Rp-GpsG and Sp-GpsG into 500 ul of 0.01% formic acid buffer. Peak integration was done using Waters TargetLynx software. Calibration curves were built by fitting the analyte standard concentration versus the standard peak area using linear regression analysis with a weight factor of 1/x, y=ax+b, where the a parameter is the slope and b is the y-intercept.

-

10

From the LC-MS/MS traces of both the standards and the sample RNAs, we observed that the LC retention times and ion fragment patterns in the digested total RNA samples match with the data from our synthetic Rp-GpsG. No Sp-GpsG was detected in the samples we tested, although we have shown that Sp-GpsG could be detected in the digested synthetic oligonucleotides containing the PS bonds using the same methods (Wu et al., 2020).

-

11

To calculate the concentration of GpsG or G in the sample RNAs, the areas from LC-MS/MS chromatogram traces of sample RNAs (Figure 3), together with the area and concentration of G, Rp- and Sp-GpsG standards from Figure 2 and Chart 1 were applied to the equation: G, Rp- and Sp-GpsG concentration in the sample = G, Rp- and Sp-GpsG Area of the sample × concentration of the standard/area of the standard, where concentration of the standard is determined in step 1–3 and the areas of the standard are obtained from LC-MS/MS traces.

-

12

The ratio, the concentration of Rp-GpsG divided by the concentration of G, is then used to quantify the frequency of the Rp-GpsG modification in various types of cells.

Figure 3.

LC-MS/MS traces of G (282.06>150.103) and GpsG (643.084>150.091) of the digested total RNAs extracted from several types of cells. The G concentration was measured in 100x dilution of the GpsG sample.

Figure 2.

LC-MS/MS traces of standards G (282.06>150.10) and Rp- and Sp-GpsG (643.08>150.09).

Background Information

The work described herein provides detailed methods to study the newly discovered RNA PS modification that is a part of our continuous goals of studying the structures and functions of natural RNA modifications. This discovery opens up new opportunities to explore the epitranscriptomic-wide PS modifications and reveal their significance in chemical biology. It is anticipated that other closely related research topics, such as whether the RNA PS modification is permanent or reversible, its dynamic regulatory enzymes and mechanisms, its potential epigenetic functions, and the existence of complex PS modification combined with base or ribose modifications, will attract further investigations. This research will eventually provide the knowledge foundation to promote RNA-based drug discovery. Therefore, a reliable protocol to identify and quantify the RNA PS modification is needed to advance our understanding of this modification across the epitranscriptome. The protocols described here for preparation of dinucleotide standards, RNA extraction and digestion, and analysis with mass spectrometry are robust and reproducible for discovering and quantifying RNA PS modifications in a wide range of cell types.

Critical Parameters & Troubleshooting

In the HPLC purification of RNA dinucleotides, the fluoride-treated product should always have undergone a C18 column purification before HPLC purification to remove the fluoride reagent and protect the HPLC columns. The RNA PS standards need to be checked for quality, such as with an LC-MS equipped with a DAD detector. It should also be noted that the UPLC-MS method is for qualitative purpose to identify RNA PS modification. For quantitative analysis, the LC-MS/MS method and stereo-pure standards with precise quantity are needed to follow basic protocol 3. The nuclease mix usually digest the normal PO backbone in 15 minutes and should also work for RNAs extracted from other cell types, leaving the PS linked dimers for further detection.

Anticipated Result

With this protocol, the PS dinucleotide standards and the stereo-pure PS dinucleotide standards are prepared for mass spectrometry. Researchers can also follow this protocol to develop mass spectrometry methods to detect and quantify many other PS dinucleotide standards besides GpsG in particular cellular RNAs of their interest.

Time Consideration

The time required for PS dinucleotide synthesis, purification, and analysis is about one week. The extraction and purification of cellular RNAs takes from several days to a couple of weeks depending on the types of cells. The mass analysis takes several hours with the correct parameters set up.

Table 1.

The retention time, LC-MS/MS area and concentration of G (282.06>150.10), Rp-GpsG and Sp-GpsG. (643.084>150.091) standards.

| Retention time (min) | Area | Concentration (pg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| G (282.06>150.10) | 2.07 | 1595482.75 | 5.74 × 104 |

| GpsG-Rp (643.08>150.09) | 3.96 | 8749.565 | 6.03 × 103 |

| GpsG-Sp (643.08>150.09) | 4.25 | 5736.11 | 5.34 × 103 |

Acknowledgement

We are grateful for the funding (NSF-1845486 and NSF-1715234 to J.S). Research was also supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM39422).

Literature Cited

- Basanta-Sanchez M, Temple S, Ansari SA, D’Amico A, and Agris PF 2016. Attomole quantification and global profile of RNA modifications: Epitranscriptome of human neural stem cells. Nucleic Acids Research 44:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CTY, Dyavaiah M, DeMott MS, Taghizadeh K, Dedon PC, and Begley TJ 2010. A quantitative systems approach reveals dynamic control of tRNA modifications during cellular stress. PLoS Genetics 6:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Ranganathan S, Qu G, Piazza CL, and Belfort M 2018. Structural accommodations accompanying splicing of a group II intron RNP. Nucleic Acids Research 46:8542–8556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar CE, High KA, Joung JK, Kohn DB, Ozawa K, and Sadelain M 2018. REVIEW SUMMARY Gene therapy comes of age. 4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruehanroengra P, Vangaveti S, Ranganathan SV, Wang R, Chen A, and Sheng J 2017. Nature’s Selection of Geranyl Group as a tRNA Modification: The Effects of Chain Length on Base-Pairing Specificity. ACS Chemical Biology 12:1504–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkhout N, Tran J, Smith MA, Schonrock N, Mattick JS, and Novoa EM 2017. The RNA modification landscape in human disease. Rna 23:1754–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostov O, Liboska R, Páv O, Novák P, and Rosenberg I 2019. Solid-phase synthesis of phosphorothioate/ phosphonothioate and phosphoramidate/ phosphonamidate oligonucleotides. Molecules 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalak JA, Pomerantz SC, Crain PF, and Mccloskey JA 1993. A novel method for the determination of posttranscriptional modification in RNA by mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Research 21:4577–4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, and Harada S 2013. RNA isolation from mammalian samples. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcluckey SA, Van Berkel GJ, and Glish GL 1992. Tandem Mass Spectrometry of Small, Multiply Charged Oligonucleotides. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 3:60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachtergaele S, and He C 2017. The emerging biology of RNA post-transcriptional modifications. RNA Biology 14:156–163. Available at: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1267096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell J, and Hengge AC 2005. The Thermodynamics of Phosphate versus Phosphorothioate Ester Hydrolysis. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 70:8437–8442. Available at: 10.1021/jo0511997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein CA, and Castanotto D 2017. FDA-Approved Oligonucleotide Therapies in 2017. Molecular Therapy 25:1069–1075. Available at: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong T, Chen S, Wang L, Tang Y, Ryu JY, Jiang S, Wu X, Chen C, Luo J, Deng Z, et al. 2018. Occurrence, evolution, and functions of DNA phosphorothioate epigenetics in bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115:E2988–E2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Chen S, Xu T, Taghizadeh K, Wishnok JS, Zhou X, You D, Deng Z, and Dedon PC 2007. Phosphorothioation of DNA in bacteria by dnd genes. Nature Chemical Biology 3:709–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Tang Y, Dong X, Zheng YY, Haruehanroengra P, Mao S, Lin Q, and Sheng J 2020. RNA Phosphorothioate Modification in Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes. ACS Chemical Biology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L, Liu S, Chen S, Xiao Y, Zhu B, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Chen B, Luo J, Deng Z, et al. 2019. A new type of DNA phosphorothioation-based antiviral system in archaea. Nature Communications 10:1–11. Available at: 10.1038/s41467-019-09390-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]