Abstract

Recent studies have highlighted that early enhancement of the glycolytic pathway is a mode of maintaining the pro-inflammatory status of immune cells. Thiamine, a well-known co-activator of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, a gatekeeping enzyme, shifts energy utilization of glucose from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation. Thus, we hypothesized that thiamine may modulate inflammation by alleviating metabolic shifts during immune cell activation. First, using allithiamine, which showed the most potent anti-inflammatory capacity among thiamine derivatives, we confirmed the inhibitory effects of allithiamine on the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production and maturation process in dendritic cells. We applied the LPS-induced sepsis model to examine whether allithiamine has a protective role in hyper-inflammatory status. We observed that allithiamine attenuated tissue damage and organ dysfunction during endotoxemia, even when the treatment was given after the early cytokine release. We assessed the changes in glucose metabolites during LPS-induced dendritic cell activation and found that allithiamine significantly inhibited glucose-driven citrate accumulation. We then examined the clinical implication of regulating metabolites during sepsis by performing a tail bleeding assay upon allithiamine treatment, which expands its capacity to hamper the coagulation process. Finally, we confirmed that the role of allithiamine in metabolic regulation is critical in exerting anti-inflammatory action by demonstrating its inhibitory effect upon mitochondrial citrate transporter activity. In conclusion, thiamine could be used as an alternative approach for controlling the immune response in patients with sepsis.

Keywords: allithiamine, citrate accumulation, lipid droplet formation, lipopolysaccharides, metabolic flux

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is a life-threatening clinical syndrome caused by an excessive immune response to an infection. The incidence of sepsis has remained unchanged for over 20 years, and hospital mortality has ranged from 17% to 26% depending on disease severity, but there is currently no adequate treatment method (Fleischmann et al., 2016).

Dendritic cells are responsible for the first line of defense in response to infection. Upon pathogen exposure, they immediately and dramatically turn on several processes, including the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and co-stimulatory molecules. To support abrupt energy-demanding processes during activation, dendritic cells undergo metabolic reprogramming by shifting their glucose usage from oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to aerobic glycolysis (Van den Bossche et al., 2017). During metabolic reprogramming, there are marked events that include the accumulation of citrate and biosynthesis of fatty acids and prostaglandins from exported cytoplasmic citrate (O'Neill, 2014). The enhancement of lipid droplet formation via citrate accumulation is a notable feature of dendritic cell activation, directly connected to acquiring and producing building blocks of membranes required to transport cytokines to the extracellular space (Cubillos-Ruiz et al., 2015; Infantino et al., 2014).

The switching balancing between glycolysis and OXPHOS deteriorates the integrity of mitochondria (O'Neill, 2014). Mitochondrial dysfunction in immune cells aggravates the pathogenesis of sepsis (Merz et al., 2017). The generation of excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) directly inhibits mitochondrial respiration and causes damage to the mitochondrial structure, including the lipid membrane (Singer, 2014). Various clinical studies have demonstrated an association between the degree of mitochondrial impairment and clinical severity and sepsis-induced organ dysfunction (Singer, 2014).

By de-phosphorylating pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) E1α, thiamine, identified as a co-activator of PDH complex (PDC), promotes the conversion of cytosolic pyruvate to mitochondrial acetyl CoA and inhibits pyruvate breakdown into lactate (Hanberry et al., 2014). Although thiamine has been shown to have an anti-inflammatory effect in immune cells, a coordinated explanation linking thiamine’s role of modulating metabolite distribution and its immune function has not yet been established (Bozic et al., 2015).

In this study, we demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effect of thiamine in terms of metabolic regulation during sepsis. We hypothesized that thiamine may inhibit inflammation by modulating metabolic shifts during immune cell activation. Allithiamine reduced the inflammatory response, ROS production, and polymorphonuclear neutrophil infiltration as well as the proportion of dysfunctional mitochondria in dendritic cells. Allithiamine alleviated metabolic reprogramming upon lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activation, which subsequently reduced “citrate–lipid synthesis”-mediated pro-inflammatory processes, including cytokine production, costimulatory molecule expression, and PGE2 generation in dendritic cells. We also suggested thiamine’s previously unappreciated role as an anticoagulant relating to thiamine’s regulation of the “citrate–lipid synthesis–PGE2” axis in septic conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Eight-week-old 20 g male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Dooyeol Biotech (Korea). All animal studies were performed according to protocols approved by Kyungpook National University (permit No. 2019-0003) and under recommendations for the proper use and care of the specific pathogen-free housing facility at Kyungpook University. For survival studies, mice were sacrificed by CO2 euthanasia following humane endpoints. The signs of the moribund state included impaired motility, inability to maintain an upright position, and labored breathing (Nemzek et al., 2004). All injections and organ removal were performed under isoflurane anesthesia.

Isolation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were generated from C57BL/6J mice bone marrow via incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium (Hyclone, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 20 ng/ml granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and 20 ng/ml IL-4 (PeproTech, USA). The cells were harvested on day 6 of expansion and were used for subsequent assays.

Flow cytometry

Dendritic cells were stained with PE-Cy7-anti-CD11c, BV421-anti-CD40, PE-anti-CD80, and APC-anti-CD86 (BioLegend, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 min at 4°C. Lipid droplets were stained with 10 µM BODIPY493/503, and mitochondria membrane potentials were estimated with 20 nM MitoTracker Deep Red and 20 nM MitoTracker Green (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for 30 min at 37°C. ROS was assayed by a DCFDA Cellular ROS Detection Assay Kit (Abcam, UK). Data were analyzed using FACS LSR Fortessa cytometry with BD CellQuest Pro software (BD, USA).

Cytokine measurements

The ELISA Kits for the measurement of interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) were all purchased from eBioscience (USA). The ELISA Kit for the measurement of PGE2 was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (USA). Lactate, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity was assayed using colorimetric assay kits (BioVision, USA). Tissue factor was assessed by a Mouse Tissue Factor ELISA Kit (Abcam).

Measurement of ATP production rate

The ATP production rate was measured using a Seahorse XF-96 Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Biosciences, USA). The culture medium consisted of RPMI160 supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin B. BMDCs were seeded in a XF-96 culture plate at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well and incubated overnight. The cells were treated with LPS 100 ng/ml with or without allithiamine 10 µM for 16 h. The assay medium comprised of XF base medium (Seahorse Biosciences) supplemented with 5.5 mM D-glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1X GlutaMAXTM (Gibco, USA), adjusted to pH 7.4. The inhibitors were used in the following concentrations: oligomycin A (2 µmol/L; Sigma-Aldrich), rotenone (3 μmol/L; Sigma-Aldrich), and antimycin A (3 μmol/L; Sigma-Aldrich).

Metabolite extraction and LC-MS/MS analysis

On day 6, BMDCs were washed with 10% dialyzed FBS (DFBS) media. Next, 5 × 106 BMDCs in the 10% DFBS media supplemented with 5.5 mM D-Glucose 13C6 were stimulated with 100 ng/ml LPS with or without allithiamine for 16 h. Cells were washed twice with 0.9% NaCl and sonicated in 200 µl of metabolite extraction solution (chloroform:methanol:water 1:3:1, v/v). All the samples were lyophilized and resuspended in 300 µl of 0.1% formic acid. For separation, analytes were subjected to a pentafluorophenyl column (100 × 2.1 mm, 3 µm) containing acetonitrile as mobile phase (in 0.1% formic acid at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min) by using an HPLC Nexera coupled with an LCMS-8060 mass spectrometer (Shimadzu, Japan). 3C-mass isotopomer distributions were determined by Q3 selected ion monitoring in scan mode and corrected for natural isotope abundance for target metabolite isotopomers.

Tail bleeding assay

The tail bleeding assay was performed as previously described (Liu et al., 2012). Mice were injected with 50 mg/kg LPS or 5 mg/kg allithiamine. Twelve hours after the allithiamine injection, the tail tip was cut and immediately immersed into a 50-ml tube containing 37°C normal saline. Each mouse was monitored until bleeding had stopped for 1 h. The volume of blood flowing out of the tail and the total bleeding time were then measured.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from 5 × 106 BMDCs using QIAzol lysis reagent (Qiagen, Germany), and the synthesis of cDNA was performed using a RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was carried out using SYBR Green (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the ViiA 7 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA). The samples were amplified for 40 cycles as follows: 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 30 s. Relative quantification was performed to analyze qPCR data, using the 2-ΔΔCt method with mouse 36B4 as an internal control gene; data were expressed as relative fold changes. The primer sequences were as follows: Dgat2, F: 5′-TGGAACACGCCCAAGAAG-3′, R: 5′-CACACGGCCCAGTTTCG-3′; Cox2, F: 5′-CCGACTAAATCAAGCAAAAGTAACAT-3′, R: 5′-AAATTTCAGAGCATTGGCCATAG-3′; TXBsynthase, F: 5′-ATCAGCCAAGCCTGT GAACT-3′, R: 5′-CCTCTCTTCTGCTGCTTGCT-3′; 36B4, F: 5′-ACCTCCTTCTTCCAGGCTTT-3′, R: 5′-CTCCAGTCTTTATCAGCTGC-3′.

Measurements of polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration

The lungs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and were processed for paraffin embedding. Next, 4-µm sections of paraffin blocks were stained with H&E. Images were captured with a digital camera (Nikon DS-Ri1; Nikon, Japan) coupled to a Nikon Eclipse Ni microscope (Nikon) under 20× magnification.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SD of three to four independent experiments. Individual data points were compared by Student’s t-test. The survival of mice was analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method followed by the log-rank test. The analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (ver. 22.0; IBM, USA). Differences between groups were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Allithiamine exerts a therapeutic effect on LPS-induced murine sepsis model

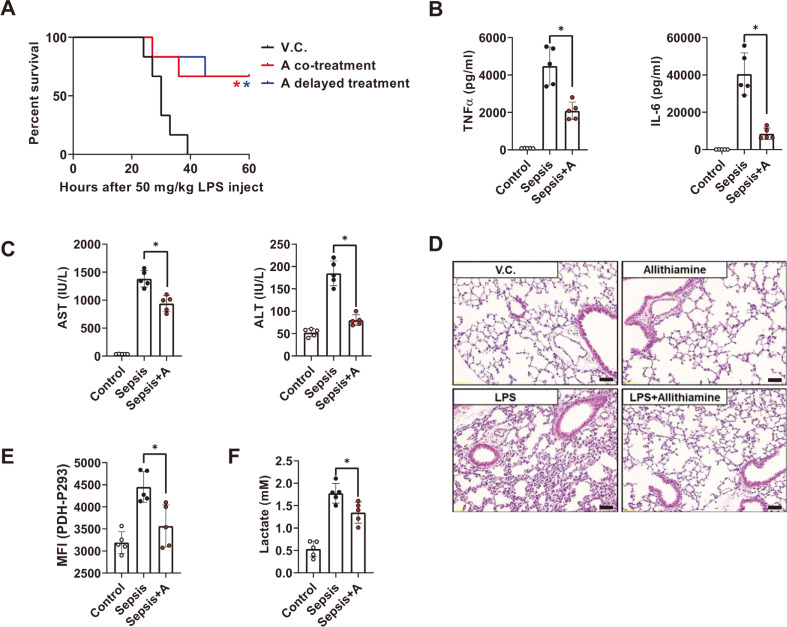

Recent clinical studies support the potential of thiamine as a sepsis therapeutic (Bozic et al., 2015; Donnino et al., 2016; Woolum et al., 2018; Yadav et al., 2010). However, the efficacy of each thiamine derivative has not been compared, and a valid in vivo demonstration has not yet been performed. First, we selected three well-known thiamine derivatives and compared the degree of maturation status in dendritic cells during LPS-induced activation. Allithiamine displayed the strongest anti-inflammatory effect among the reagents (Supplementary Fig. S1), so we further questioned whether allithiamine has a protective role in septic conditions. Interestingly, allithiamine not only showed a therapeutic effect in the concurrently injected model but also showed an effect in the 3 h-delayed treatment model, which makes allithiamine more suitable in the clinical setting (Fig. 1A). To assess whether these effects were derived from the modulation of inflammation by allithiamine, pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα (early time point, at 1 h after LPS injection) and IL-6 (late time point, at 18 h after LPS treatment) were measured. As shown in Fig. 1B, allithiamine injection led to a significant reduction of these cytokine levels. Since the cytokine storm can lead to organ failure (Wang and Ma, 2008), we examined whether allithiamine exerts a protective effect on endotoxemia-induced liver damage. The serum concentrations of AST and ALT were significantly reduced 18 h after endotoxemia induction in the allithiamine treatment group (Fig. 1C). In addition, allithiamine successfully mitigated the cellular infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) in the lung during sepsis (Fig. 1D). Thiamine promotes PDH activity, which inhibits the excess glycolytic flux leading to lactate production (Hanberry et al., 2014). To confirm whether thiamine can modulate glycolytic metabolism during sepsis, we compared PDH-Phospho293 on CD11chigh cells in splenocytes during sepsis between the allithiamine treatment group and the control treatment group. As shown in Fig. 1E, PDH activity was suppressed in the sepsis group, as described in other clinical data, but allithiamine significantly increased the PDH activity compared to the LPS-only injected group (Nuzzo et al., 2015). Allithiamine also succeeded in alleviating the lactate production during endotoxemia (Fig. 1F). Collectively, these data indicate that allithiamine promotes host survival during endotoxemia.

Fig. 1. Allithiamine reduces lethality in LPS-induced murine sepsis model.

Endotoxemia was induced by LPS treatment (50 mg/kg, intraperioneal injection [i.p.]) in animals. C57BL/6J mice were treated with or without allithiamine (5 mg/kg, intravenous injection [i.v.]), concurrently or 3 h after LPS treatment. (A) Survival was monitored for 60 h. Asterisk indicates significant differences (*P < 0.05) between LPS triggered group and allithiaimine cotreatment group (red asterisk) or delayed treatment group (blue asterisk). V.C. designates vehicle control, which is composed of 10% DMSO in 0.9%NaCl. (B) Pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα (at 1 h after endotoxemia induction: early time point) and IL-6 (at 18 h after endotoxemia induction: late time point) in serum were determined by ELISA. (C) The extent of organ dysfunction was determined by liver function test (AST, ALT) using serum extracted 18 h after LPS challenge. (D) The degree of tissue damage was determined by PMN infiltration in lung sections, excised 18 h after LPS challenge. Representative images of lung sections from each group were captured at 20× magnification. Scale bar = 100 µm. (E) PDH-Phospho293 on CD11chigh cells in splenocytes and (F) lactate in serum were determined 18 h after LPS challenge. (B, C, E, and F) All data are presented as means ± SEM of three independent experiments. Asterisk indicates significant differences (*P < 0.05) between vehicle control + LPS and allithiamine + LPS group.

Allithiamine exerts an anti-inflammatory effect in dendritic cells both in vitro and in vivo

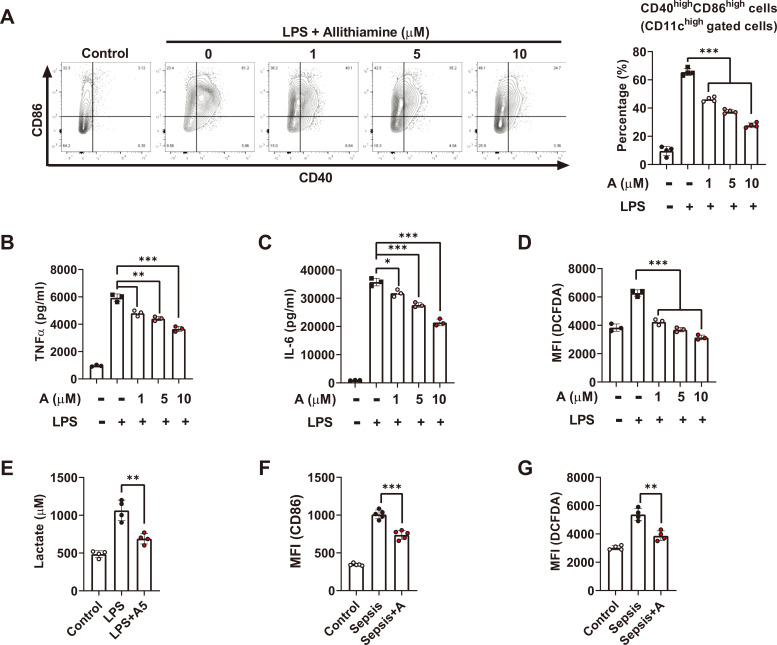

In order to estimate the anti-inflammatory role of allithiamine in the LPS-induced endotoxemia model, we characterized the LPS-induced dendritic cell activation in the presence of allithiamine. Co-stimulatory molecules were elevated upon LPS stimulation, and allithiamine treatment downregulated the percentage of CD40highCD86high cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the in vivo data, allithiamine decreased the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-6 (Figs. 2B and 2C). Furthermore, allithiamine modulated ROS and lactate production as well as inflammatory reaction markers in dendritic cells (Figs. 2D and 2E). Consistent with the in vitro data, we also confirmed that allithiamine downregulated dendritic cell maturation and ROS formation during endotoxemia (Figs. 2F and 2G). These results indicate that allithiamine exerts an anti-inflammatory effect on dendritic cells both in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 2. Allithiamine reduces LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines, co-stimulatory molecules, and ROS generation in dendritic cells.

(A-D) BMDCs (1 × 106) were stimulated with 100 ng/ml LPS for 16 h. Simultaneously, BMDCs were treated with allithiamine at concentrations of 1, 5, and 10 µM. (A) CD40 and CD86 on dendritic cells were measured by flow cytometry, and percentages of CD40highCD86high cells in CD11c gated cells were calculated. (B and C) Supernatants were collected, and pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-6 were assessed using ELISA. (D) DCFDA on dendritic cells was determined using flow cytometry. (E) BMDCs were stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 16 h and simultaneously with allithiamine 5 µM. Supernatants were collected, and lactate was assessed. (F and G) CD86 and DCFDA were measured in CD11c gated cells on splenocytes during LPS-induced endotoxemia. The scatterplot with the bar graph illustrates the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each surface marker. Asterisk indicates significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) from data obtained during the LPS-only challenge. Allithiamine is designated as A.

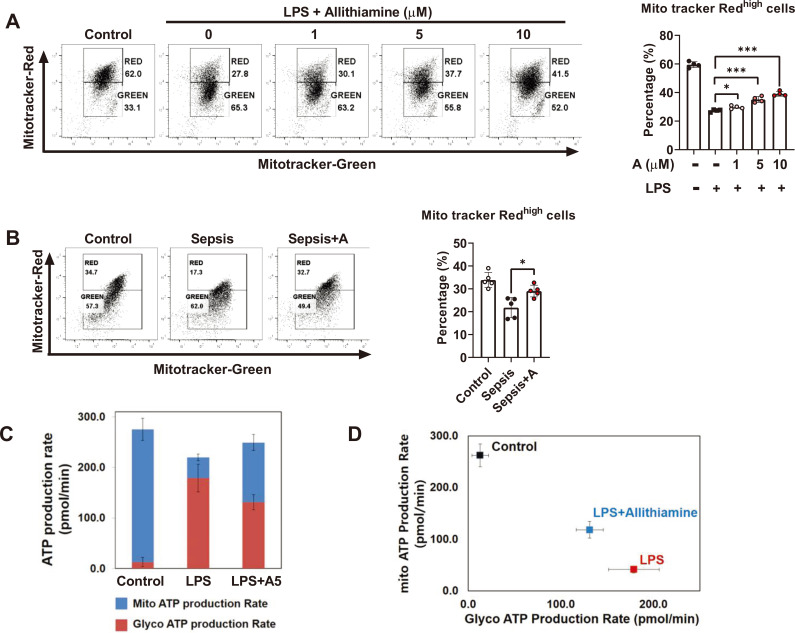

Allithiamine recovers mitochondrial function and inhibits glycolysis during dendritic cell activation

The excessive production of ROS may deteriorate the mitochondrial function (Armstrong et al., 2018). We reasoned that reduced ROS production by allithiamine may alter the integrity of mitochondria. As hypothesized, allithiamine enhanced mitochondria membrane potential in a dose-dependent manner during LPS-induced dendritic cell activation (Fig. 3A). In order to verify the role of allithiamine in the immune and mitochondrial status of dendritic cells during sepsis, we analyzed the degree of alteration of mitochondrial membrane potential in splenic dendritic cells upon endotoxemia induction. Upon LPS challenge, the proportion of the functional mitochondrial pool was significantly increased in the allithiamine treatment group when compared to that in the control group (Fig. 3B), indicating that allithiamine successfully supported the maintenance of their membrane potential. Next, we questioned how the maintenance of integrity is directly linked to the functional aspect of mitochondria; thus, we assessed the major site of ATP generation in immune cells during endotoxemia. As shown in Fig. 3C, the dominant ATP production shift from the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to glycolysis upon LPS stimulation and allithiamine treatment hampered this process. In other words, allithiamine alters the energy dependency of immune cells shifting from mitochondria to glycolysis during endotoxemia. These data show that the immunomodulatory role of allithiamine in immune cells involves the regulation of the metabolic switch.

Fig. 3. Allithiamine sustains mitochondrial integrity and regulates glycolytic flux during immune cell activation.

(A) BMDCs (1 × 106) from C57BL6 mice were stimulated with 100 ng/ml LPS for 16 h. Simultaneously, BMDCs were treated with allithiamine at concentrations of 1, 5, and 10 µM. Dendritic cells were then subjected to flow cytometric analysis for MitoTracker Deep Red and MitoTracker Green, and quantitative analysis was performed. (B) MitoTracker Deep Red and MitoTracker Green were analyzed in CD11c gated cells on splenocytes during LPS-induced endotoxemia. (C and D) The ATP production rate was measured using a Seahorse XF-96 Flux Analyzer. BMDCs were seeded in a XF-96 culture plate at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well and treated with LPS 100 ng/ml with or without allithiamine 10 µM for 16 h. Asterisk indicates significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) from data obtained during the LPS-only challenge. Allithiamine is designated as A.

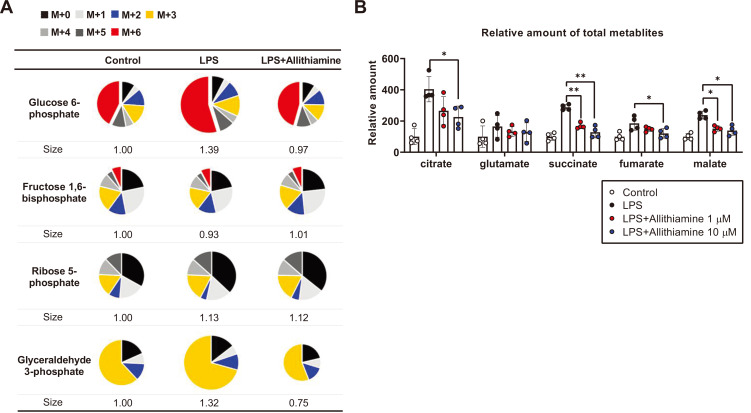

Allithiamine inhibits citrate accumulation during LPS-induced dendritic cell activation

One of the well-known consequences of the metabolic shift from OXPHOS to glycolysis during immune activation is glucose-driven citrate accumulation (O'Neill, 2014). Since allithiamine was shown to decrease glycolysis-dependent ATP production (Figs. 3C and 3D), we hypothesized that allithiamine may reduce the citrate accumulation during immune reaction. To test our hypothesis, we performed a 13C6-glucose trace analysis in the presence of allithiamine during dendritic cell activation. The relative mass distribution vector represented by the metabolites derived from 13C6-glucose as well as the total amount of TCA metabolites were measured (Fig. 4). The total amount of glucose increased by 39% in the activated dendritic cells and then decreased with allithiamine treatment (Fig. 4A). Consistent with Figs. 3C and 3D, allithiamine reduced glycolysis intermediates during LPS-induced dendritic cell activation (Fig. 4A). The amount of accumulated citrate was increased in the LPS-only treated group, while allithiamine significantly prevented the rise in this metabolite (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that the metabolic shift from glycolysis to OXPHOS mediates citrate accumulation, important in maintaining pro-inflammatory status in immune cells.

Fig. 4. Allithiamine attenuates glycolysis and reduces citrate accumulation in activated dendritic cells.

(A) Allithiamine effect on relative amounts of 13C-labeled glycolysis intermediates; n = 4 per group. (B) The absolute amount of TCA cycle intermediates in dendritic cells with or without allithiamine (1 µM, 10 µM) was compared. Asterisk indicates significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01) from data obtained during the LPS-only challenge. The values are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Allithiamine suppresses the “citrate–lipid droplet–PGE2” axis and may exert an anticoagulant effect during sepsis

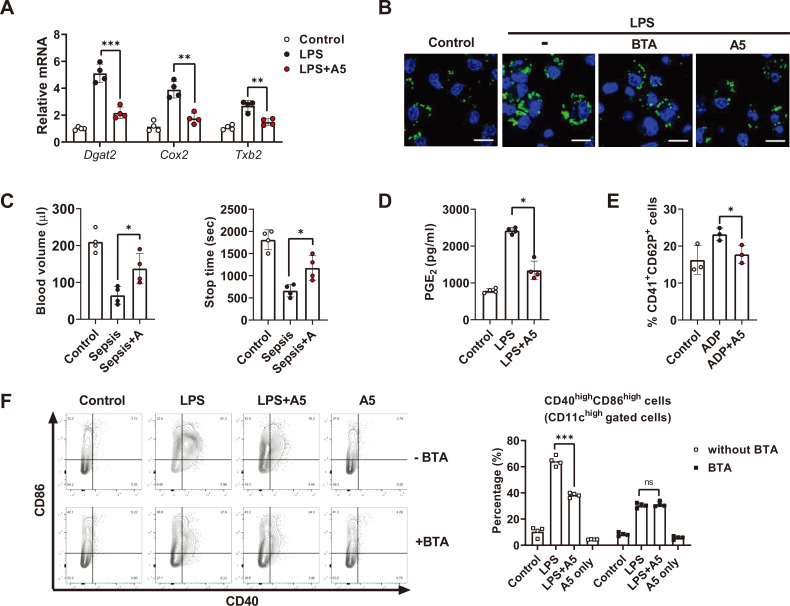

Citrate is produced in the first reaction of the TCA cycle through the condensation of acetyl-CoA and one oxaloacetate, and it is then exported from the mitochondria to the cytoplasm via the mitochondrial citrate carrier (CIC) (Infantino et al., 2014). After being withdrawn from the mitochondria, citrate metabolizes into fatty acids, which in turn become cellular components related to the transportation of newly expressed cytokines and co-stimulatory molecules as well as the proteins of pro-inflammatory lipids themselves, including PGE2 (MacPherson et al., 2017). Such a “citrate accumulation–lipid droplet–immune response axis” is a metabolic view of how metabolic reprogramming supports pro-inflammatory status in immune cells (Cubillos-Ruiz et al., 2015). Since allithiamine markedly suppressed citrate accumulation during dendritic cell activation (Fig. 4B), we further investigated whether allithiamine modulates subsequent lipid formation and related immune reactions (den Brok et al., 2018). As shown in Fig. 5A, levels of genes important for lipid droplet biogenesis were increased in the activated dendritic cells, and allithiamine reduced their expression. In addition, allithiamine suppressed lipid droplet formation in activated dendritic cells (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Allithiamine inhibits “citrate–lipid droplet” pathway and exerts anticoagulant effect during endotoxemia.

(A, B, and D) BMDCs were activated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 16 h in the presence of allithiamine at a concentration of 5 µM. (A) Relative mRNA levels were calculated. (B) Lipid droplet formation in dendritic cells was measured by confocal microscopy using BODIPY 493/503. Scale bar = 10 µm. (C) Tail bleeding assay was performed in LPS-induced model comparing control with allithiamine injection group. Twelve hours after LPS injection, the tail tip was amputated, and the volume of blood flowing out of the tail and the total bleeding time were estimated. (D) Supernatants were collected, and PGE2 concentration was assessed using ELISA. (E) Platelets were isolated from C57BL6 mice, activated with ADP 2 mM, and treated with or without allithiamine at 5 µM. CD41+ and CD62P+ cells were detected by flow cytometry. (F) CD11c+CD86+ CD40+ cells during LPS-induced activation with or without BTA 5 µM or allithiamine 5 µM were detected by flow cytometry. Asterisk indicates significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) from data obtained during the LPS-only challenge. ns, not significant. Allithiamine is designated as A.

Prostaglandins secreted from monocytes contribute to platelet activation (Friedman et al., 2015). Since allithiamine successfully diminished the “citrate–lipid droplet axis” including PGE2 and TXB2, we tried to delineate the effect of allithiamine on septic conditions. To investigate whether allithiamine is able to inhibit coagulation during sepsis, we performed a tail bleeding assay. The tail bleeding assay is used to evaluate the anticoagulant effect in various disease conditions by measuring bleeding time and volume of blood drained from a tail following amputation (Liu et al., 2012). As shown in Fig. 5C, allithiamine treatment led to an increase in bleeding time and volume, while tissue factor was not altered during sepsis (Supplementary Fig. S2). This observation implies that allithiamine may play a role in inhibiting LPS-mediated coagulation processes, suggesting the potential use of allithiamine as an anticoagulant against various septic conditions. We also measured the direct effect of allithiamine on PGE2 production during dendritic cell activation (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, allithiamine diminished the percentage of CD41+CD62P+ cells upon ADP-mediated activation (Fig. 5E).

To confirm that alleviating citrate accumulation is allithiamine’s main mode of immune modulation, we reasoned that the anti-inflammatory effect of allithiamine would be abrogated when citrate export is inhibited. As shown in Fig. 5B, LPS-induced lipid droplet formation in dendritic cells was significantly reduced upon BTA treatment (Infantino et al., 2014). When the “citrate–lipid droplet” axis was restrained by BTA, a compound inhibiting the mitochondrial CIC, allithiamine no longer suppressed CD40+CD86+ expression (Fig. 5F). These data imply that allithiamine regulation of the metabolic switch modulates the “citrate–lipid droplet” axis, which consequently alleviates both inflammation and coagulation during sepsis.

DISCUSSION

In this study, using dendritic cells, we provided evidence that targeting metabolic plasticity by thiamine, a PDH activator known to inhibit aerobic glycolysis, is directly linked to its anti-inflammatory capacity. The present study not only determined the clinical relevance of allithiamine in the treatment of sepsis but also delineated thiamine’s anti-inflammatory role from the metabolic perspective by determining how metabolism regulates inflammation. We showed that allithiamine reduces glucose-driven citrate retention, which in turn mitigates lipid-mediated inflammation. We further interpreted the role of thiamine from a new perspective: the redistribution of glucose metabolites conditions the immune cells to dampen the coagulation processes during sepsis.

Clinically, the time gap between the onset of infection and diagnosis of sepsis is inevitable, and a successful therapeutic strategy at a later time point is important in determining the effectiveness of sepsis treatment (Dellinger et al., 2013). Sepsis is diagnosed when the patient shows symptoms after exposure to bacteria, so there is always a gap between the time of infection and the time of treatment. Interestingly, allithiamine not only showed a therapeutic effect in the concurrently injected model but also showed an effect even 3 h after the LPS challenge, which makes it more clinically relevant (Fig. 1A). We assumed that this delayed effect is attributed to the fact that allithiamine regulates the immune response mostly by metabolic regulation (Fig. 5F). In other words, since allithiamine modulates inflammation mainly via restraining the “citrate–lipid droplet” axis, its capacity is not limited to the anti-inflammatory role but includes the anticoagulant effect exerted during sepsis (Fig. 5C).

The export of citrate via the mitochondrial CIC leads to the formation of lipid droplets, which readily cooperate with inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandins, including PGE2 (Infantino et al., 2019). Interestingly, allithiamine even led to a direct anticoagulant effect on platelets, as shown in Fig. 5E. A recent study showed that platelet activation largely depends on glycolysis-dominant status, and metabolic reprogramming during platelet activation is an alternative target of controlling coagulation. For example, dichloroacetate, a well-known PDH activator, has been proven to exert a direct anticoagulant effect by inhibiting glycolysis (Nayak et al., 2018). Collectively, the fact that allithiamine hampers the “citrate–lipid droplet” axis in activated dendritic cells makes allithiamine an anticoagulant reagent as well as an immune suppressor in septic conditions.

PDC plays a crucial role in regulating metabolic reprogramming in dendritic cells (McCall et al., 2018). PDC determines the fate of pyruvate, either by converting cytosolic pyruvate to mitochondrial acetyl CoA or by breaking down into lactate. PDC activity was decreased in liver tissue obtained from the murine sepsis model, which was demonstrated by an increase in the phospho-PDC E1α form (McCall et al., 2018). Clinical evidence indicates that PDC activity and quantity are decreased in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of humans with sepsis, which are associated with mortality (Nuzzo et al., 2015). As shown in previous papers, PDH-Phospho293 on CD11chigh cells in splenocytes was increased during sepsis, and allithiamine successfully enhanced PDH activity (Fig. 1E).

The maintenance of the mitochondrial integrity and the increase in PDH activity by allithiamine was reflected in the result of the 13C6-glucose trace analysis. LPS increased the glucose uptake and the intermediates of the glycolytic pathway in the dendritic cells, which consequently increased the flux of pyruvate to both lactate and citrate (Figs. 2E and 4). However, mitochondria with reduced integrity do not efficiently process the glucose-driven metabolites, which is reflected in the diminished number of changed 13C6-labeled glucose during LPS stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S3). Although LPS increases the total amount of accumulated citrate, the efficiency of glucose-driven flux is significantly reduced. Allithiamine successfully recovers the function of mitochondria, which promptly increases the number of changed 13C6-labeled glucose as well as the dependency of energy utilization on mitochondria during dendritic cell activation (Figs. 3C and 3D, Supplementary Fig. S3).

The greatest advantage of allithiamine compared to other thiamine derivatives lies in its capacity to be rapidly absorbed in the immune cells. The anti-inflammatory role of thiamine derivatives has been demonstrated mostly in overnight pre-incubating conditions (Bozic et al., 2015; Yadav et al., 2010). When co-treated with LPS, however, these effects were considerably abrogated (Supplementary Fig. S1). This implies that commonly used thiamine derivatives, benfotiamine and fursultiamine, have low absorption capacity. For example, allithiamine required only a 10-fold reduced concentration compared to fursultiamine to suppress LPS-induced dendritic cell activation (Supplementary Fig. S1). In the murine endotoxemia model, allithiamine was the only thiamine derivative that showed a delayed therapeutic effect (Fig. 1). The rapid absorption of allithiamine in the immune cells may explain the enhanced therapeutic efficacy in sepsis.

In summary, our present study demonstrated that allithiamine inhibits the immune response by suppressing metabolic shifts during immune cell activation. Allithiamine successfully alleviated citrate accumulation in activated dendritic cells, which then inhibited the immune cell-activated coagulation-enhancing process due to the “citrate–lipid droplet-prostaglandin pathway.” We showed that allithiamine exerts a protective effect on pro-inflammatory status as well as an anticoagulant effect during various septic conditions. Together, these findings suggest allithiamine as a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of patients with sepsis.

Supplemental Materials

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), which is funded by the Ministry of Science, Information, and Communication Technology, Korea (2019R1A2C1007753; 2019R1A2C1084371) and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project of the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI16C1501; HI15C0001).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.J.C., C.H.J., and T.H.K. conceived and performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. T.H.K. and D.H.P. secured funding. E.J.C. and C.H.J. performed experiments. D.H.P. provided expertise and feedback.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Armstrong J.A., Cash N.J., Ouyang Y., Morton J.C., Chvanov M., Latawiec D., Awais M., Tepikin A.V., Sutton R., Criddle D.N. Oxidative stress alters mitochondrial bioenergetics and modifies pancreatic cell death independently of cyclophilin D, resulting in an apoptosis-to-necrosis shift. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:8032–8047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozic I., Savic D., Laketa D., Bjelobaba I., Milenkovic I., Pekovic S., Nedeljkovic N., Lavrnja I. Benfotiamine attenuates inflammatory response in LPS stimulated BV-2 microglia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubillos-Ruiz J.R., Silberman P.C., Rutkowski M.R., Chopra S., Perales-Puchalt A., Song M., Zhang S., Bettigole S.E., Gupta D., Holcomb K., et al. ER stress sensor XBP1 controls anti-tumor immunity by disrupting dendritic cell homeostasis. Cell. 2015;161:1527–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellinger R.P., Levy M.M., Rhodes A., Annane D., Gerlach H., Opal S.M., Sevransky J.E., Sprung C.L., Douglas I.S., Jaeschke R., et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit. Care Med. 2013;41:580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Brok M.H., Raaijmakers T.K., Collado-Camps E., Adema G.J. Lipid droplets as immune modulators in myeloid cells. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnino M.W., Andersen L.W., Chase M., Berg K.M., Tidswell M., Giberson T., Wolfe R., Moskowitz A., Smithline H., Ngo L., et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of thiamine as a metabolic resuscitator in septic shock: a pilot study. Crit. Care Med. 2016;44:360–367. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann C., Scherag A., Adhikari N.K., Hartog C.S., Tsaganos T., Schlattmann P., Angus D.C., Reinhart K. International Forum of Acute Care Trialists. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016;193:259–272. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0781OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman E.A., Ogletree M.L., Haddad E.V., Boutaud O. Understanding the role of prostaglandin E2 in regulating human platelet activity in health and disease. Thromb. Res. 2015;136:493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanberry B.S., Berger R., Zastre J.A. High-dose vitamin B1 reduces proliferation in cancer cell lines analogous to dichloroacetate. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014;73:585–594. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2386-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantino V., Iacobazzi V., Menga A., Avantaggiati M.L., Palmieri F. A key role of the mitochondrial citrate carrier (SLC25A1) in TNFalpha- and IFNgamma-triggered inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1839:1217–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantino V., Pierri C.L., Iacobazzi V. Metabolic routes in inflammation: the citrate pathway and its potential as therapeutic target. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019;26:7104–7116. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180510124558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Jennings N.L., Dart A.M., Du X.J. Standardizing a simpler, more sensitive and accurate tail bleeding assay in mice. World J. Exp. Med. 2012;2:30–36. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v2.i2.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson S., Horkoff M., Gravel C., Hoffmann T., Zuber J., Lum J.J. STAT3 regulation of citrate synthase is essential during the initiation of lymphocyte cell growth. Cell Rep. 2017;19:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall C.E., Zabalawi M., Liu T., Martin A., Long D.L., Buechler N.L., Arts R.J.W., Netea M., Yoza B.K., Stacpoole P.W., et al. Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex stimulation promotes immunometabolic homeostasis and sepsis survival. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e99292. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.99292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz T.M., Pereira A.J., Schurch R., Schefold J.C., Jakob S.M., Takala J., Djafarzadeh S. Mitochondrial function of immune cells in septic shock: a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak M.K., Dhanesha N., Doddapattar P., Rodriguez O., Sonkar V.K., Dayal S., Chauhan A.K. Dichloroacetate, an inhibitor of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases, inhibits platelet aggregation and arterial thrombosis. Blood Adv. 2018;2:2029–2038. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemzek J.A., Xiao H.Y., Minard A.E., Bolgos G.L., Remick D.G. Humane endpoints in shock research. Shock. 2004;21:17–25. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000101667.49265.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzo E., Berg K.M., Andersen L.W., Balkema J., Montissol S., Cocchi M.N., Liu X., Donnino M.W. Pyruvate dehydrogenase activity is decreased in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with sepsis. A prospective observational trial. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015;12:1662–1666. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201505-267BC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill L.A. Glycolytic reprogramming by TLRs in dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:314–315. doi: 10.1038/ni.2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis-induced multi-organ failure. Virulence. 2014;5:66–72. doi: 10.4161/viru.26907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bossche J., O'Neill L.A., Menon D. Macrophage immunometabolism: where are we (going)? Trends Immunol. 2017;38:395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Ma S. The cytokine storm and factors determining the sequence and severity of organ dysfunction in multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2008;26:711–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolum J.A., Abner E.L., Kelly A., Thompson Bastin M.L., Morris P.E., Flannery A.H. Effect of thiamine administration on lactate clearance and mortality in patients with septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2018;46:1747–1752. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav U.C., Kalariya N.M., Srivastava S.K., Ramana K.V. Protective role of benfotiamine, a fat-soluble vitamin B1 analogue, in lipopolysaccharide-induced cytotoxic signals in murine macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;48:1423–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.