Abstract

Chlamydia trachomatis is the cause of several diseases worldwide in the form of a sexually transmitted urogenital disease or ocular trachoma. The pathogen contains a small genome yet, upon infection, expresses two enzymes with deubiquitinating activity, termed ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2, presumed to have redundant deubiquitinase (DUB) function on account of similarity of primary structure of their catalytic domain. Previous studies have led to structural characterization of enzymatic properties of ChlaDUB1 however, ChlaDUB2 has yet to be investigated thoroughly. In this study, we investigated the deubiquitinase properties of ChlaDUB2 and compared them to that of ChlaDUB1. This revealed a distinct difference in hydrolytic activity with regards to di- and polyubiquitin chains, while showing similar ability to cleave a monoubiquitin-based substrate, ubiquitin aminomethylcoumarin (Ub-AMC). ChlaDUB2 was unable to cleave a diubiquitin substrate efficiently whereas ChlaDUB1 could rapidly hydrolyze this substrate comparable to a prototypical prokaryotic DUB, SdeA. With polyubiquitinated green fluorescent protein substrate (GFP-Ubn), whereas ChlaDUB1 efficiently disassembled the polyubiquitin chains into monoubiquitin product, the deubiquitination activity of ChlaDUB2, while showing a depletion of the substrate, did not produce appreciable levels of the monoubiquitin product. We report the structures of a catalytic construct of ChlaDUB2 and its complex with ubiquitin propargyl amide. These structures revealed differences in residues involved in substrate recognition between the two Chlamydia DUBs. Based on the structures we conclude that the distal ubiquitin binding is equivalent between the two DUBs, consistent with the Ub-AMC activity result. Therefore, the difference in activity with longer ubiquitinated substrates may be due to differential recognition of these substrates involving additional ubiquitin binding sites.

INTRODUCTION

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular pathogen responsible worldwide for causing sexually transmitted urogenital infection as well as ocular trachoma. The Chlamydiae family have reduced genomes; C. trachomatis in particular only contains 1.04 M base pairs and 895 open reading frames, which also lacks several metabolic enzymes1. This reduced genome requires C. trachomatis to utilize a host for survival. The bacterium exists in two major forms during its lifecycle: outside the host cell, C. trachomatis exists as a metabolically repressed elementary body and inside the host as a mature metabolically active reticulate body2, 3. The elementary body invades the epithelial cell using a type-III secretion system to induce the endocytosis4–8. Subsequently, the bacterium is phagocytosed by the host cell, thus enclosing it inside a phagocytic vacuole. The bacterium germinates into a reticulate body which then subsequently releases bacterial effectors to manipulate host cellular processes towards its own metabolic needs and evasion from host immune response, where ubiquitin plays a critical role4, 9. Upon infection, the host cell ubiquitinates the inclusion membrane with Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains to signal for the destruction of the bacterium via lysosomal fusion3, 10–15.

Ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of the 76 amino acid protein, ubiquitin (Ub), through its terminal carboxylate group on Gly76 to a lysine residue of a target protein via an isopeptide bond. The formation of this bond is catalyzed by the sequential action of an ATP-dependent E1 Ub-activating enzyme, an E2 Ub-conjugating enzyme, and an E3 Ub-ligase. Ubiquitin can be also ligated onto a lysine residue (Lys 6, 11, 27, 29, 33, 48 and 63) or the amino terminus (Met 1) of another Ub, creating polyubiquitin (poly-Ub) chains that can be appended to protein targets. The Ub monomers in the chain can be modified on the same lysine residue throughout, forming a homotypic poly-Ub chain, or, form a mixed chain where Ub is modified on different lysine residues giving rise to a branched architecture in the chain. When desired the poly-Ub chains can be trimmed or removed entirely from their protein adducts by deubiquitinases (DUBs), which catalyze the hydrolysis of the isopeptide (or peptide) bonds in the poly-Ub chains or those linking Ub to protein targets. A balance of ubiquitination/deubiquitination regulates a myriad of cellular processes such as lysosomal degradation, proteasomal degradation, and DNA repair16–22. Although the Ub system in its entirety has been observed only in eukaryotic organisms, certain pathogens, including bacteria, have recently been shown to harbor virulent factors that behave as mimics of E3 ligases and enzymes displaying DUB activity23, 24. Such organisms include pathogenic bacteria such as Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydia trachomatis and Salmonella typhimurium. The newly characterized family of prokaryotic DUBs in these and some other intracellular bacteria belongs to the CE clan of Cys proteases in the MEROPS database. They share a distinct Ulp fold (similar to the SENP cysteine protease family of eukaryotes) in their core structure and exhibit a general preference for Lys63-linked poly-Ub chains as substrates18, 25–29.

To survive long enough to reproduce, C. trachomatis must have a mechanism to interrupt the host defense. Toward this end the pathogen secretes bacterial effectors, two of which, ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2, exhibit DUB and deneddylating activities30. Previous studies have shown that ChlaDUB1 is capable of suppressing NF-κB activation and Iκ-Bα ubiquitination and degradation31. ChlaDUB1 has been shown to stabilize the apoptosis regulator, Mcl-1, and mutation of the ChlaDUB1 gene caused a significant reduction in bacterial burden upon infection in mice models32. Strains harboring inactive mutants of either ChlaDUB1 or ChlaDUB2 resulted in a drastic impairment of C. trachomatis mediated Golgi apparatus fragmentation upon infection in HeLa and A549 cells14, 33. Therefore, both ChlaDUBs seem to be important for bacterium growth and protection from the host cellular defense response. Interestingly, the two DUBs show differences in subcellular localization during infection; ChlaDUB1 is primarily found at the Golgi while a majority of ChlaDUB2 is localized at the endoplasmic reticulum. This indicates that even though both are required for Golgi fragmentation, the two DUBs may have different functions. Studies conducted by Pruneda et al. have provided an insightful analysis of bacterial DUBs across several bacterial species including C. trachomatis29. They categorized some of these CE clan proteases as having dual DUB and acetyltransferase activity. This dual activity was observed in ChlaDUB1, while ChlaDUB2 demonstrated only DUB activity and therefore considered as the dedicated DUB in the organism. Though structural and biochemical analyses were conducted on ChlaDUB1, ChlaDUB2 is yet to be structurally characterized along with its Ub recognition properties. It remains unclear as to what the function of ChlaDUB2 is and whether it is redundant in host defense evasion. In this study, ChlaDUB2 was investigated to elucidate the differences between the two chlamydia DUBs with regards to their structure and DUB activity. The goal of this comparison is to discern if the DUB activities of these two enzymes are redundant or they display significant differences in enzymatic activity and substrate preference, thereby providing further insight into the physiological relevance of these two enzymes. In addition, we report the structure of a catalytic construct of ChlaDUB2 DUB domain in the apo form and in complex with the suicide substrate ubiquitin propargyl, which permits a direct comparison of structural properties of the two DUBs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, Expression, Purification

Full length constructs of ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2 from Chlamydia trachomatis L2 (kind gifts from Hidde Ploegh, Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology) were each subcloned into pGEX-6P1 (GE Biosciences) using standard cloning protocols. Constructs were designed to omit the transmembrane domain of ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2 to improve solubility. The constructs prepared were truncated from the N-terminus past the transmembrane domain. Each construct was transformed into Escherichia coli Rosetta cells (Novagen). Cultures of each construct were grown at 37°C to an OD600 between 0.4 – 0.6. The cultures were then subsequently induced by addition of 300 μM IPTG and allowed to incubate at 18°C for 16–18 hours. Cells were then pelleted at 6000 rpm for 6 minutes, resuspended in lysis buffer (1x PBS with 400mM KCl) and subsequently lysed via French press. Lysate was then cleared through ultracentrifugation at 100,000 x g at 4°C for 1 hour. N-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST) fused constructs were purified using standard GST purification protocol (GE Biosciences) using 1x PBS with 400mM KCl as the column buffer. Protein was eluted using 250mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500mM KCl, 10mM reduced glutathione. Eluate was dialyzed against 1x PBS with 400mM KCl with 1mM DTT to which PreScission Protease was added to remove the GST tag. Eluate was subsequently passed through a glutathione affinity column to collect the tag-subtracted protein in the flow through. Constructs were further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex S75 column (GE Biosciences) using running buffer of 50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 50mM NaCl, 1mM DTT. Fractions containing the protein of interest was concentrated and either used immediately or flash frozen and stored in −80°C for future use. The SdeA DUB construct used here was purified as described in Puvar et al34.

Ubiquitin-MESNa (Ub-MESNa), in pTXB1 as ubiquitin1–75-intein-chitin binding domain, was expressed from BL-21 DE3 cells; cultures were grown at 37°C to an OD600 between 0.4 – 0.6. The cells were subsequently induced through the addition of 300 μM IPTG and allowed to incubate at 18°C for 16–18 hours. Cells were then pelleted at 6000 rpm for 6 minutes, resuspended in 25mM MES (2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid), 350mM sodium acetate pH 6.0 lysed using French press and cleared using ultracentrifugation at 100,000 x g at 4°C for 1 hour. Ubiquitin-intein chitin binding domain was further purified and converted to Ub-MESNa on-column via incubation in 25mM MES, 350mM sodium acetate, 50mM sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate pH 6.0 as described by Borodovsky et al35. Ub-MESNa was then titrated to pH 8.0 and converted to ubiquitin propargyl amide through the addition of propargylamine. Ubiquitin propargyl amide (Ub-PRG) was then purified using cation ion exchange chromatography using a Mono S column (GE Biosciences).

Diubiquitin Preparation

GST-Ube1, GST-Ubc13, and GST-Uve1a were recombinantly expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 De3 cells. Cultures of each construct were grown at 37°C to an OD600 between 0.4 – 0.6. The cultures were then subsequently induced by addition of 300 μM IPTG and allowed to incubate at 18°C for 16–18 hours. Cells were then pelleted at 6000 rpm for 6 minutes, resuspended in lysis buffer (1x PBS with 400mM KCl) and lysed via French press. Lysate was then cleared through ultracentrifugation at 100,000 x g at 4°C for 1 hour. These constructs were purified following a standard GST purification protocol (GE Biosciences) using 1x PBS with 400mM KCl as the column buffer. Protein was eluted using 250mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 500mM KCl, 10mM reduced glutathione. Proteins were either used immediately or flash frozen and stored in −80°C. Ubiquitin (1–76; WT, K63R, and D77) in pET26b (a gift from Yasuke Sato, University of Tokyo, Tokyo) was transformed into E. coli Rosetta cells. The cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.4–0.6, induced with 300 μM IPTG, and grown for 16–18 h at 18 °C. Cultures were then pelleted by centrifuging at 6000 rpm for 6 minutes. Pellets were resuspended in column buffer 50mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5 and then lysed via French press. Ubiquitin was then purified on SP Sepharose resin. Diubiquitin substrates were prepared using enzymes specific for Lys63 linkages, GST-UbE1, GST-Ubc13, and GST-Uev1a at 37 °C36 in the presence of ATP and Mg2+. Reaction was carried out until an appreciable amount of diubiquitin formed and were then quenched with 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5, and further purified by using cation exchange chromatography (Mono S; GE Biosciences)37.

GFP-Ubn Substrate Generation

GFP-Ubn was produced using the following previously published protocol38. In brief, GFP-PY-titin-cyclin was purified from E. coli Rosetta cells and incubated at 37°C with GST-E1, Ubc4, and RSP5 for 6 hours until a molecular weight greater than 200 kDa was achieved. Reaction mixture was flash frozen until further use.

Mutagenesis

Point mutations for this study were performed via standard site directed mutagenesis protocols. The Δα5 (Δ178–200) deletion mutant was produced using the site overlap extension PCR protocol39. The presence of these mutants was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Mutants were transformed into E. coli Rosetta cells and were purified using standard GST affinity chromatography (GE Biosciences).

Generation of ChlaDUB293–339 Ubiquitin Propargyl Complex

Equimolar amounts of ChlaDUB293–339 and Ub-PRG were mixed, titrated to pH 8.0, and incubated overnight at room temperature. Reaction was quenched by diluting in 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 1 mM DTT. Complex was purified using Mono Q anion exchange chromatography (GE Biosciences).

Crystallization and Structure Determination

Initials hits for ChlaDUB293–339 and ChlaDUB293–339 Ub-PRG covalent complex were screened using sparse matrix screens from Hampton Research using sitting drop vapor diffusion. ChlaDUB293–339 was crystallized at 15 mg/mL in 0.1 M HEPES sodium pH 7.5, 2% (v/v) PEG 400, 2 M ammonium sulfate with 0.3 M NDSB-195 additive at ambient temperature. ChlaDUB293–339 Ub-PRG was crystallized at 13.5 mg/mL in 0.1 M HEPES sodium pH 7.5, 0.8 M sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate, 0.8 M sodium phosphate monobasic at ambient temperature. Crystals were optimized through subsequent rounds of microseeding and additive screening using hanging drop vapor diffusion, 0.1 M cesium chloride additive provided the best quality crystals. Diffraction data for ChlaDUB293–339 and ChlaDUB293–339 Ub-PRG were collected at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory, diffraction data was then processed using HKL200040. ChlaDUB293–339 diffracted to 2.3 Å and was solved using molecular replacement using Molrep in the CCP4 suite41, with ChlaDUB1 as a model (PDB ID: 5HAG)42. Refinement was performed using Refmac543, 44 in the P212121, space group; crystallographic data collection and refinement parameters are listed in Table 1. The crystals of ChlaDUB293–339 Ub-PRG complex diffracted to 2.6 Å. The crystal belongs to the tetragonal system, with P43 and P43212 as the likely space groups according to an analysis by Xtriage in Phenix suit of programs. An initial MR search was conducted in the P43212 space group employing Phaser MR using the apo ChlaDUB293–339 structure as the search probe45. After rigid body refinement and two rounds of restrained refinement of the model obtained from the MR search, electron density for the Ub C-terminus was visible extending from the catalytic cysteine of ChlaDUB2. First, the C-terminal tail was built into the density emerging from residue Cys282 of ChlaDUB2 and then a model of Ub (1UBQ) was superimposed onto the built-in residues46 which resulted in the placement of Ub in the complex. Iterative rounds of model building and refinement in this space group using Refmac543, 44, however, did not proceed as expected, prompting us to examine the P43 space group. This model of the complex from the above refinement was used as a search probe to solve the structure in the P43 space group using Molrep in CCP441, 42 which produced relatively low R-factors upon further refinement, indicating that it might be the correct space group. Two molecules were present in the asymmetric unit. Final rounds of refinement were performed in Phenix using NCS averaging and TLS parameters45. Electron density for α5 helix was poor and the helix was difficult to model. The final model has 1.6% of the residues as Ramachandran outliers. These residues lie in regions where the electron density is very poorly defined making it difficult for the residues to be modeled accurately.

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| Parameters | ChlaDUB293–339 | ChlaDUB293–339-Ub-PRG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | ||||

| Space group | P212121 | P43 | ||

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a,b,c (Å) | 40.36, 74.37, 77.41 | 108.69, 108.69, 62.28 | ||

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 | 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Resolution (Å*) | 53.63–2.29 (2.34–2.29) | 50.00–2.50 (2.54–2.50) | ||

| Rmerge* | 0.181 (0.00) | 0.074 (0.969) | ||

| Rpim* | 0.107 (0.672) | 0.031 (0.419) | ||

| I/σ* | 9.38 (2.04) | 22.22 (2.09) | ||

| Completeness* | 98.7 (98.8) | 99.78 (99.5) | ||

| Redundancy* | 5.3 (5.0) | 6.7 (6.1) | ||

| CC1/2 | 0.583 | 0.853 | ||

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 53.63–2.29 | 48.61–2.50 | ||

| No. reflections | 10306 | 25243 | ||

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.1956/0.2472 | 0.2740/0.2885 | ||

| No. atoms | 1943 | 5019 | ||

| Protein | 1911 | 5011 | ||

| Water | 32 | - | ||

| B factors | ||||

| ChlaDUB2 | 41.98 | 73.71 | ||

| Ubiquitin | - | 81.86 | ||

| Water | 38.57 | - | ||

| rmsd | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0152 | 0.015 | ||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.734 | 1.89 | ||

| Validation | ||||

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 97.00 | 88 | ||

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 2.6 | 10.4 | ||

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.4 | 1.6 |

Values in parentheses indicate data obtained for the highest resolution shell.

Diubiquitin Cleavage Assay

Cleavage assays of Lys63 linked diubiquitin were conducted using 100nM of each enzyme and 20 μM of Lys63-linked diubiquitin. Enzyme and diubiquitin were mixed and incubated in 50 mM Tris pH 7.4 50 mM NaCl 1 mM DTT at room temperature for 1 hour or 18 hours. Reactions were quenched through the addition of reducing Laemmli buffer. Deubiquitinating activity was observed through the disappearance of diubiquitin on the gel and the appearance of monoubiquitin.

GFP Polyubiquitin Assay

Cleavage assays of predominately Lys63 polyubiquitin bound to GFP-titin cyclin were conducted using 100 nM of each enzyme and 2 μM of GFP-Ubn. Enzyme and GFP-Ubn were mixed and incubated in reaction buffer of 50 mM Tris pH 7.4 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT at room temperature for 1 hour. Deubiquitinating activity was observed through the disappearance of high molecular weight GFP-Ubn and the appearance of unmodified GFP-titin cyclin as well as the appearance of monoubiquitin, diubiquitin, triubiquitin, and tetraubiquitin.

Ubiquitin-AMC Hydrolysis Assay

ChlaDUB constructs were each diluted to a final reaction concentration of either 0.2 nM or 2 nM in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.6, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 5 mM DTT) and incubated at 30°C for five minutes prior to the addition of ubiquitin AMC (Ub-AMC). Ubiquitin-AMC (Boston Biochem) was diluted to a final reaction concentration of 500 nM in reaction buffer. Hydrolysis of Ub-AMC was measured at 37°C using either a Tecan (Mannedorf, Switzerland) or Synergy Neo2 (Biotek) fluorescence plate reader with excitation wavelength of 365 nm and emission wavelength of 465 nm. Wild type ChlaDUB2 was used in each assay to account for batch-to-batch variation with Ub-AMC and day-to-day variation of the fluorescence plate reader.

Cleavage of Polyubiquitinated/Polyneddylated Proteins by ChlaDUBs

The cleavage of polyubiquitinated or polyneddylated proteins by ChlaDUBs was performed as previously described in Sheedlo et al27. In brief, polyubiquitinated and neddylated proteins were produced from HEK293T cells transfected to express HA-Ubiquitin or Flag-NEDD8, respectively. Cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with HA or Flag agarose beads. The beads were resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT and then were divided into aliquots and left untreated or treated with 2 μM of ChlaDUBs, for 4 hours at 37 °C. The beads were then washed three times using the cleavage buffer and boiled for 5 min in reducing Laemmli sample buffer. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and polyubiquitinated or neddylated proteins were detected by HA or Flag antibody.

Diubiquitin/Tetraubiquitin cleavage assays

To analyze the cleavage activity of the two ChlaDUBs, purified proteins were combined at a final concentration of 100 nM enzyme (ChlaDUB1 or ChlaDUB2), 2000 ng of diubiquitin (or 1000 ng of tetraubiquitin (Boston Biochem)) and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT). The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and probed by immunoblotting with primary antibodies specific for Ub (Anti-ubiquitin #3933, Cell Signaling, 1:1000) and Licor IRDye® 680LT anti-mouse secondary (1:10,000). Immunoblots were imaged using a Licor Odyssey CLx infrared imager.

Circular Dichroism

The secondary structures of wild type ChlaDUB258–339 and ChlaDUB258–339 Δα5 were determined in solution using circular dichroism. Samples were diluted to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/mL in 100 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4. Far UV CD spectra was collected using a Jasco J-1500 spectrophotometer using a cuvette of path length 0.1 cm. The spectra were collected between 200–260 nm at ambient temperature and averaged from three scans at 100 nm/min. The data was compared by calculating the mean residue ellipticity according to the following equation:

where θ is the ellipticity in degrees, l is the path length of the cuvette in centimeters. M is the molecular mass in Dalton, C is the sample concentration in mg/mL, and n is the number of residues in the protein. The mean residue ellipticity was calculated in units of deg.cm2 dmol−1.

Biolayer Interferometry

Concentration of GST-tagged ChlaDUB1130–401 (C345A) and ChlaDUB258–339 (C282A) were determined by nanodrop to enable dilution of the proteins into BLI buffer (1x PBS containing 0.05% v/v tween 20 and 0.1% w/v BSA) to a concentration of 25 μg/mL. Lys63-linked diubiquitin was buffer exchanged into 1x PBS using Millipore concentrators by performing a 1:100 dilution three times. The concentration of the Lys63-linked diubiquitin was determined by a BCA assay and diluted to a final concentration of 200 μM in BLI buffer. 1:1 serial dilution of ubiquitin was performed to make the different concentrations of analyte used in the BLI experiment. 40 μL of each solution was added to a 384 tilted well plate. One anti-GST biosensor was used for each KD measurement, dipping the various ChlaDUB protein loaded biosensors into wells that contained the lowest concentration of Lys63-diubiquitin first. These experiments were carried out in technical duplicate. GST-tagged ChlaDUB variant was allowed to load onto the biosensor for 300 seconds, followed by a cycle of diubiquitin association and dissociation at 120 seconds and 100 seconds, respectively. Biacore data analysis software (v8.2) was used to collect raw data for the association and dissociation curves.

RESULTS

C. trachomatis has been shown to express two enzymes displaying deubiquitinating and deneddylating activity30, 47. These enzymes, designated ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2, have an overall architecture consistent with typical inclusion membrane proteins from C. trachomatis48. This consists of a short N-terminal region residing inside the Chlamydia inclusion, a single-pass transmembrane domain traversing the inclusion membrane, and the C-terminal region that mediates host-pathogen interactions. For ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2, the C-terminal region contains a deubiquitinating (DUB) domain (Fig. 1). This DUB domain shares topological similarity with the Ulp (ubiquitin-like protease) domain of SENP cysteine proteases25, 26, which, along with a number of recently characterized prokaryotic DUBs, belong to the CE clan of the MEROPS database49. When they were first identified, the DUB activities in these two chlamydia effectors were deduced from their ability to form a covalent adduct with Ub and ubiquitin-like suicide inhibitors, ubiquitin vinylmethylester and Nedd8 vinylsulfone, respectively30, 47.

Figure 1.

Domain organization and topological properties of the ChlaDUBs. (A) Domain diagram of ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2 and the constructs used in our study. (B) Topology diagrams showing the similarities of the ChlaDUBs to SENP2, which is a prototypical CE-clan member that processes SUMO. TM: transmembrane domain; PPr: proline rich region. The box highlights the insertion in SENP2 in the indicated area that is used in Ub recognition in ChlaDUBs (the α5 helix).

Due to the transmembrane domain on the N-terminus, the full-length proteins are not soluble, thus several truncated constructs were prepared. These constructs were truncated from the N-terminus to remove the transmembrane domain. ChlaDUB258–339 is the longest soluble construct and ChlaDUB293–339 is the shortest construct generated and are the primary constructs investigated in this study.

DUB enzymatic activity of ChlaDUB2 differs significantly from ChlaDUB1

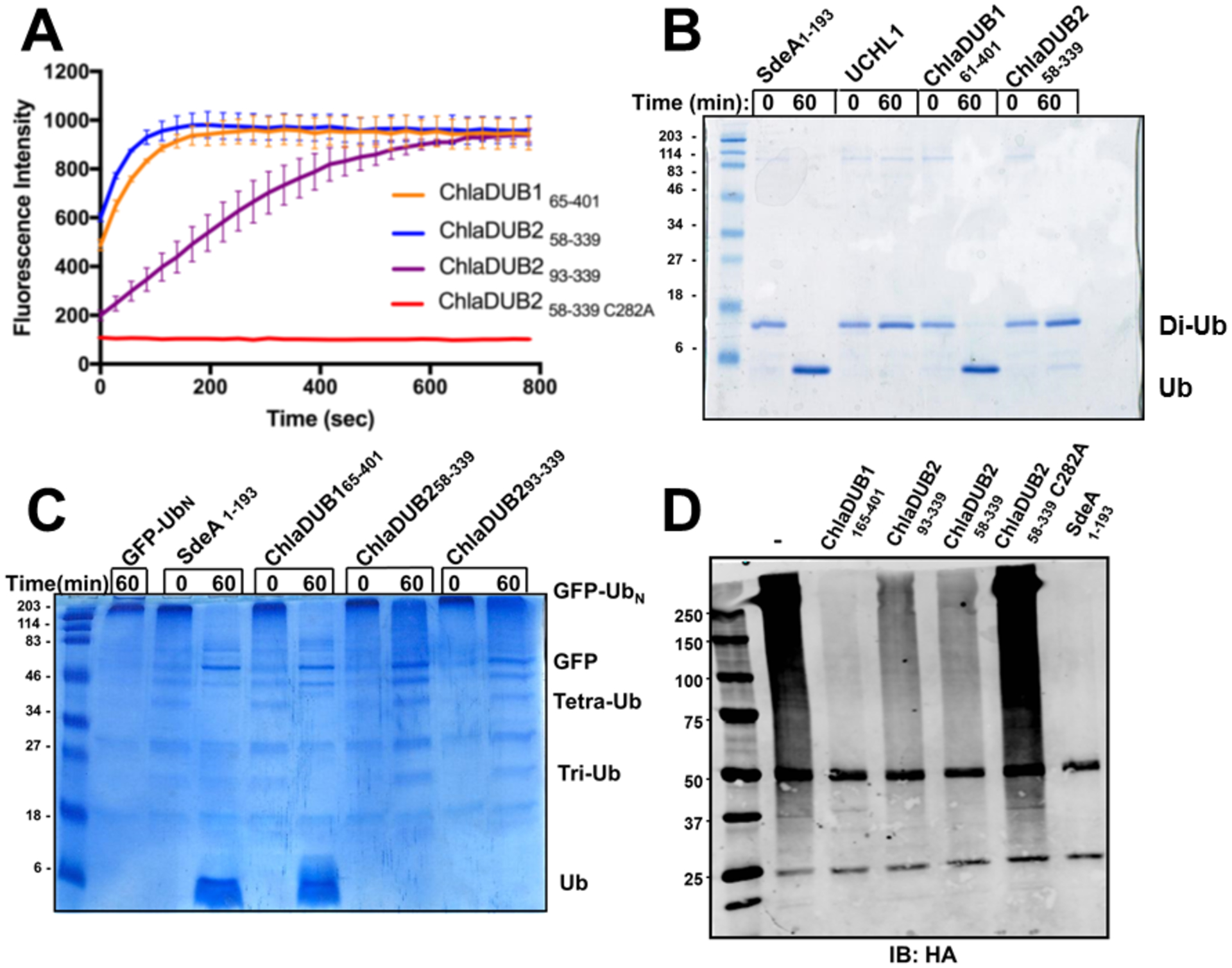

Prior investigation has demonstrated DUB activity for both ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB230. A sequence comparison of these enzymes reveals that they are 36% identical overall at the primary structural level, with the DUB domains sharing most of the similarity (Fig. S1). The genome of C. trachomatis is rather limited, so it would seem unlikely that both enzymes would be completely redundant. Therefore, our initial hypothesis was that there would be differences in how the ChlaDUBs recognize and process Ub. To characterize the DUB activity of the ChlaDUBs, multiple activity assays were conducted, each with substrates representing ubiquitinated species of increasing length. First, ChlaDUB165–401 and ChlaDUB258–339 were incubated with a monoubiquitin based biochemical substrate, ubiquitin aminomethylcoumarin (Ub-AMC); enzymatic activity was characterized through the increase in fluorescence emission by the hydrolytic release of the fluorescent AMC group from the C-terminus of the singleton Ub substrate. This revealed a similar apparent rate of reaction for the two DUB constructs from two-independent experiments employing different enzyme concentrations (Fig. 2a, and Fig. S2). Next, we incubated ChlaDUB165–401 and ChlaDUB258–339 with a longer substrate, Lys63-linked diubiquitin, and monitored enzymatic activity using SDS-PAGE. ChlaDUB1 demonstrated efficient cleavage of the diubiquitin substrate to monoubiquitin product species similar to a prototypical CE-clan DUB, SdeA of Legionella pneumophila27. Strikingly, the ChlaDUB2 construct displayed little activity towards the same substrate (Fig. 2b) even after 18 hours of incubation, similar to the human DUB UCHL1 which known to be incapable of cleaving diubiquitin (Fig. S3) while efficiently hydrolyzing Ub-AMC. The concentration of the DUBs tested in the diubiquitin hydrolysis assay was kept at 100 nM, in line with the relatively low levels of the bacterial enzyme in cellular conditions as expected for bacterial effectors in host cells. The lack of efficient diubiquitin hydrolyzing activity of ChlaDUB258–339 could be due to some occluding features adjacent to the active-site cleft, as seen in UCHL150 (for example, the crossover loop), or due to an intrinsic preference for longer poly-Ub chains or some unknown factors. To investigate the effect of longer substrates on ChlaDUB2 activity, we prepared GFP-titin-cyclin substrate (GFP, green fluorescent protein) modified with a long heterogeneous mixture of predominately Lys63-linked poly-Ub chains (GFP-Ubn) using the yeast E3 ligase RSP5, as described in Beckwith et al38. Due to the modification of poly-Ub chains, the molecular weight of GFP is significantly increased and can be seen as high-molecular weight species on an SDS-PAGE gel. Upon incubation with a DUB, a reduction of the high-molecular weight species and the generation of unmodified GFP-titin-cyclin and monoubiquitin would be indicative of DUB activity. After 1 hour of incubation, SdeA and ChlaDUB1 completely removed the Ub from the GFP-Ubn substrate (Fig. 2c). As for ChlaDUB258–339, the original molecular weight is recovered for the GFP substrate, yet there is no apparent formation of monoubiquitin species even though there was a clear depletion of the substrate, as indicated by the loss of the original high-molecular weight band, and, at its expense, appearance of a smear at the top of the gel which presumably represents higher order poly-Ub chains. Additional bands that seem to correspond to tri- and tetra-Ub species are also observed in the reaction mixture containing ChlaDUB2. This observation can be attributed to a combination of slower overall activity of ChlaDUB2 and a preference of the DUB to cleave longer poly-Ub chains over shorter ones. To investigate if ChlaDUB2 prefers longer Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains, we incubated ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2 with Lys63-linked tetra-ubiquitin chain. After two hours of incubation, ChlaDUB1 disassembled most of the tetra-ubiquitin down to monoubiquitin leaving behind little triubiquitin and diubiquitin. In contrast, ChlaDUB2’s activity on the tetraubiquitin chain resulted in accumulation of shorter chains, mostly diubiquitin, and not much monoubiquitin (Fig. S4), in line with the data shown in Figure 2c.

Figure 2.

DUB activity assays comparing the activities of the ChlaDUBs using different ubiquitinated substrates: (A) ChlaDUBs (2nM) were incubated with ubiquitin-AMC (500nM) at 37°C. The C282A construct of ChlaDUB2 is the catalytically inactive mutant. (B) ChlaDUBs, UCHL1, and SdeA1–193 (100nM) were incubated with 20μM of Lys63-linked diubiquitin for 1 hour at room temperature. Reactions were quenched with reducing Laemmli sample buffer. The numbers under each construct correspond to the residue range. (C) SdeA1–193 and ChlaDUBs (100nM) were incubated with 2μM polyubiquitinated green fluorescent protein (GFP-Ubn) for 1 hour at room temperature. Reactions were quenched with reducing Laemmli sample buffer. (D) Cleavage of ubiquitin from polyubiquitinated proteins in HEK293T cells. ChlaDUBs were incubated in lysate of HEK293T cells transiently expressing N-terminal HA tagged ubiquitin. Ubiquitinated proteins were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA antibody. Deubiquitinating activity was observed by blotting with anti-HA antibody. The numbers under each construct correspond to the residue range.

We then investigated the activity of ChlaDUB2 against native-like ubiquitinated substrates. A HEK293T cell line was created to stably express hemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged Ub (HA-Ub) similar to Sheedlo et al.27 HA-ubiquitinated species were isolated by immunoprecipitation and incubated with ChlaDUB constructs or SdeA. ChlaDUB165–401, like SdeA, efficiently removed Ub from the isolated mammalian proteins. Both ChlaDUB258–339 and ChlaDUB293–339 removed Ub from the proteins but to a lesser extent than ChlaDUB1 (Fig. 2d). Together these results indicate that the activities of ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2 are similar with regards to the hydrolysis of AMC from monoubiquitin but differ significantly when the length of the substrate changes. Among the ubiquitinated substrates, increasing the length from diubiquitin to poly-Ub chains seem to increase enzymatic efficiency for deubiquitination for ChlaDUB2. A similar assay was repeated with a HEK293T cell line stably expressing 4x FLAG-Nedd8. The 4x FLAG neddylated proteins were immunoprecipitated and incubated with ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB258–339 and ChlaDUB293–339. ChlaDUB1 removed the Nedd8 from neddylated proteins to an appreciable extent, where it was unclear if the ChlaDUB258–339 and ChlaDUB293–339 constructs removed Nedd8 to an appreciable degree. (Fig. S5).

Crystal Structure of the ChlaDUB2 DUB domain.

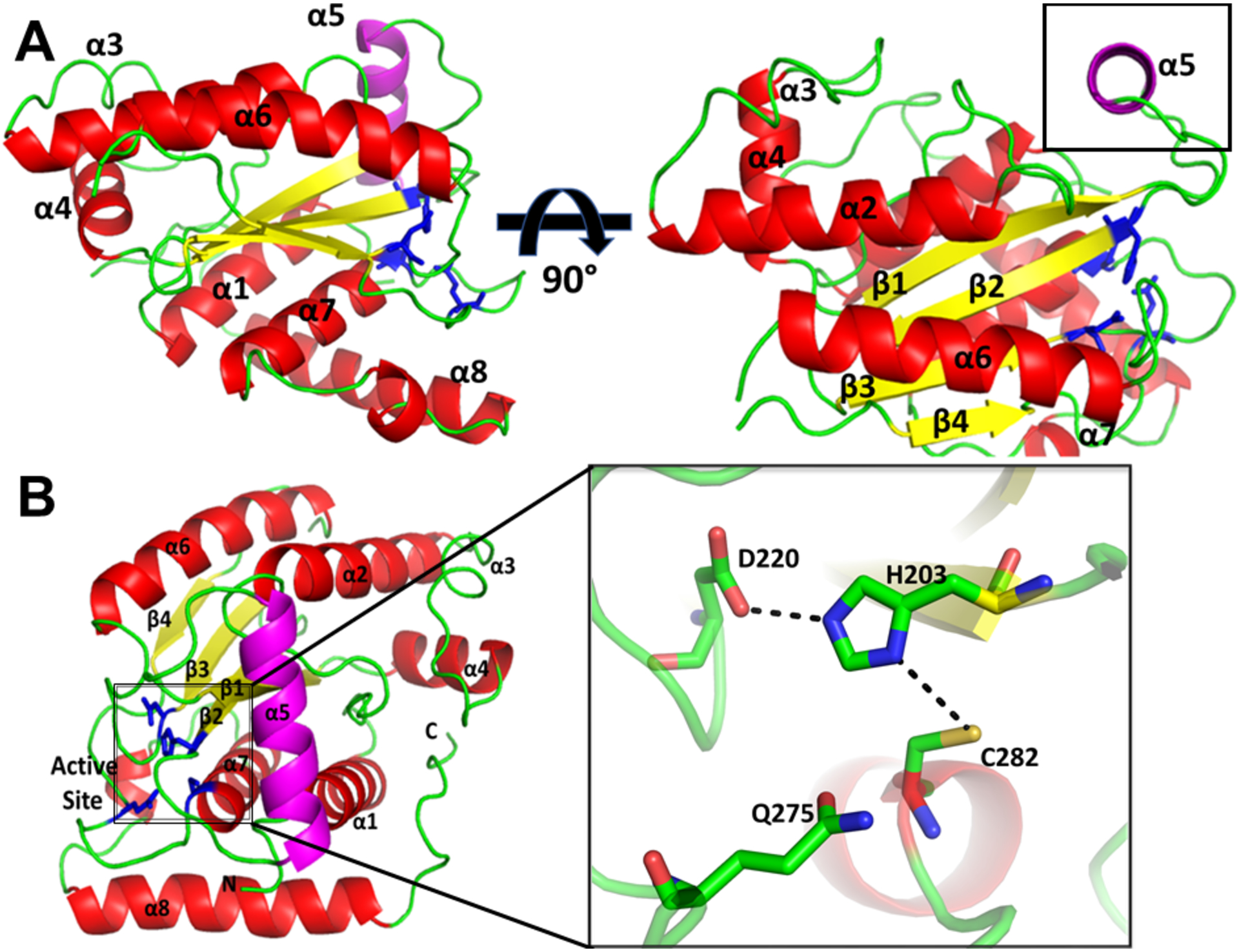

To find a structural explanation for the difference in activity, we crystallized and solved the structure of ChlaDUB293–339, which crystallized in the P212121 space group with one molecule per asymmetric unit. The phases were solved using molecular replacement with ChlaDUB1 as the search model (5HAG) and the structure was refined to 2.3 Å resolution with the crystallographic R-factor and free R-factor of 19.5% and 24.7%, respectively (Table 1). Overall, the structure of ChlaDUB2 follows a topology consistent of the currently defined CE clan proteases29 (Fig. 1b). ChlaDUB2 has a fold similar to that of the Ulp family with a central β-sheet surrounded from top and bottom by α-helices. The β-sheet is comprised of three β-strands25, 26 (β1, β2, and β3) in the center in an antiparallel arrangement and a fourth (β4) lying in a parallel orientation to β3 (Fig. 3a). The α-helices arrange primarily in two groups sandwiching the β-sheet, one containing helices α2, α6, and the other helices α1 and α7. The concave face of the β-sheet packs against α-helix, α7 that features the critical catalytic Cys282 at its amino-terminal end. The catalytic triad adopts a geometric arrangement along the classical blueprint of a canonical cysteine protease with the catalytic cysteine, Cys282, facing and within hydrogen-bonding distance from the catalytic histidine, His203, contributed by the β-sheet β2 (Fig. 3b inset), and the catalytic aspartate, Asp220 (β-strand 3) within 2.9 Å of His203, a distance that corresponds to a close hydrogen-bonding interaction. A glutamine residue from an adjacent loop, Gln275 lies within close-proximity to the Cys282 and His203 and is predicted to stabilize the oxyanion intermediate formed during hydrolysis. The side chain carbonyl group of Gln275 is within a C-H-O hydrogen-bonding distance from the His203 side chain, a characteristic feature of Cys proteases51. An α-helix, α5, is of particular interest since it protrudes out away from the protein core and is separated from the protein core by an unstructured coil on both ends. In the Ulp fold that describes the core structural features of prokaryotic DUBs, this helix is absent, replaced by a short loop (Fig. 1). In the recently described prokaryotic DUBs of the CE clan, insertion of suitable elements in this loop contributes to substrate recognition by the DUBs29. This helix α5, previously named VR3-insertion by Pruneda et al.29, 33, blocks off a canal leading directly into the active site. Overall, the structure of ChlaDUB2 is very similar to ChlaDUB1 with the overall Cα root mean square deviation (rmsd) of 1.04 Å including an aligned active site triad for catalysis (Fig. S6).

Figure 3.

Structure of ChlaDUB293–339 (6MRN). (A) Cartoon representation of ChlaDUB293–339 (6MRN) to identify α-helices (red), β-sheets (yellow), and loops (green). Helix α5 is highlighted in magenta. The box highlights helix α5. Active site residues are represented as sticks (blue). (B) Expanded view of the arrangement of the active site residues hydrogen bond contacts shown as dashed lines.

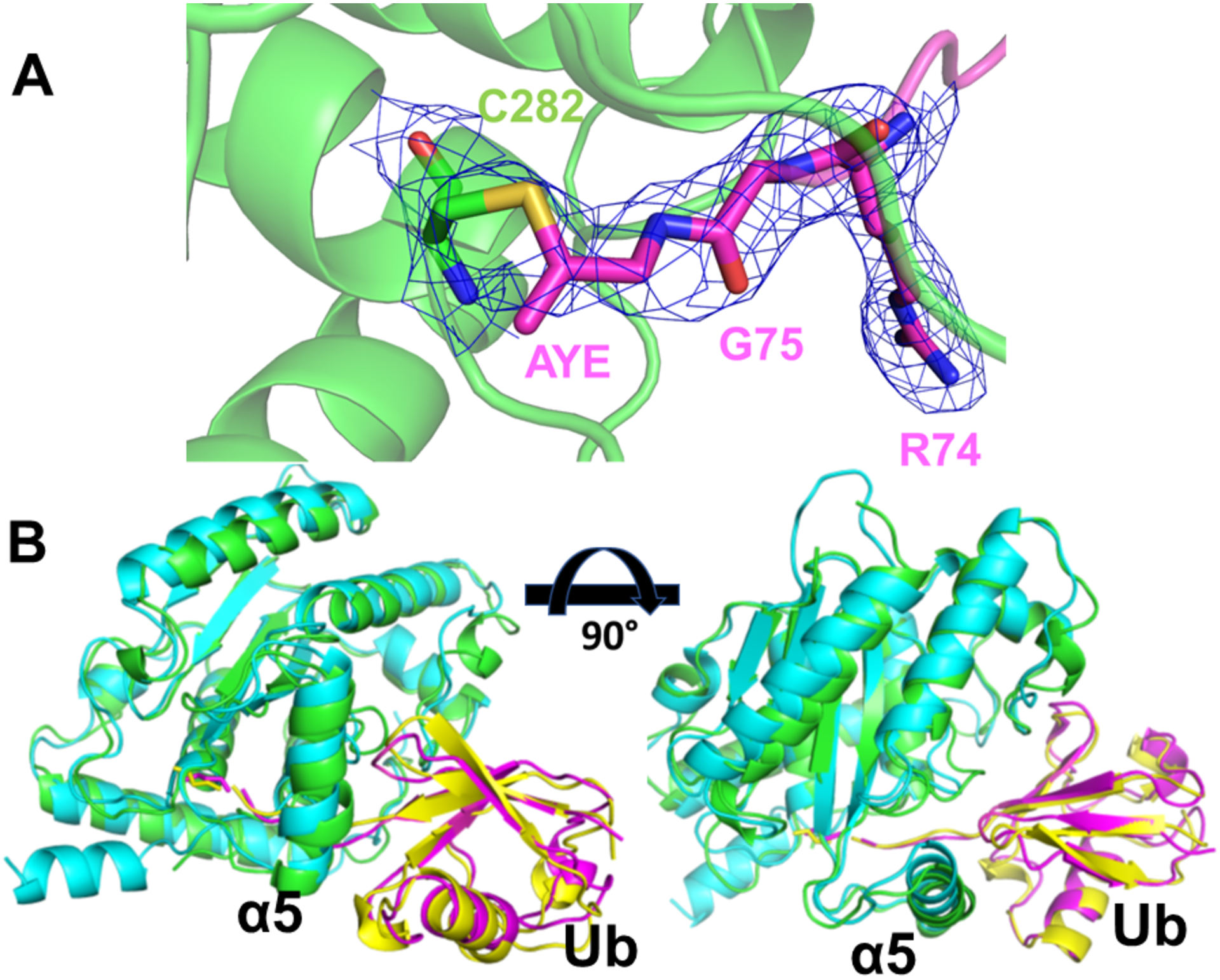

Structure of ChlaDUB2 DUB domain with ubiquitin propargyl

Since the apo structures of ChlaDUB2 and ChlaDUB1 by themselves do not seem to account much for the difference in activity we set out to determine how ChlaDUB2 interacts with Ub by crystallography. To this end we produced a covalently captured complex of ChlaDUB293–339 with Ub by allowing it to react with ubiquitin propargyl amide (Ub-PRG) and crystallized it. This structure was solved by molecular replacement using the apo structure as the search probe. In the Fo-Fc difference map, clear positive density around the active site of the enzyme revealed a potential position for the bound Ub. Ubiquitin was subsequently built into the density (see Material Methods), and after several rounds of refinement the structure of the complex converged to a model with crystallographic R-factor of 27.4% and Rfree of 28.8%. The asymmetric unit consists of two copies of the complex. In one of the subunits the density corresponding to the Ub part was poorly defined while the DUB showed good density in both subunits; the only exception being helix α5, which despite being at the interface with Ub lacked continuous, clear interpretable density. Consequently, we used both the visible electron density in our structure as well as the conformation of helix α5 in apo-ChlaDUB2 structure (6MRN) to guide our modeling of this helix (Fig. S7). A loop leading to α5 also showed weak electron density. The poor Ub density could be due to disorder of the Ub moiety (and the associated α5 of ChlaDUB2) in the crystal lattice even though it is covalently linked to the active site Cys of the DUB. Nevertheless, the copy of the asymmetric unit showing Ub in a better-defined position allowed us to deduce intermolecular contacts between the DUB and Ub at most places with reasonable confidence (Fig. 4). Ubiquitin binds to ChlaDUB2 in a similar fashion as it does to ChlaDUB1 (Fig. 4b)33, 52. This binding site is referred to as the distal binding site (also known as the S1 binding site), so named because this is where the distal Ub group in a diubiquitin substrate would interact when it is bound to the DUB. (In a diubiquitin molecule the Ub group contributing its Gly76 to the isopeptide link is referred to as the distal Ub and the Ub donating its Lys side chain as the proximal Ub.)

Figure 4.

(A) Structure of ChlaDUB293–339 Ubiquitin propargyl complex (6OAM). Ubiquitin propargyl (magenta) covalently bound to active site cysteine of ChlaDUB2 (TV green). The 2Fo-Fc electron density map is displayed in blue mesh, sigma level = 1. AYE: Allylamine. (B) Superposition of ChlaDUB2 Ub-PRG complex (ChlaDUB2 is in TV-green and Ub in magenta) and ChlaDUB1 Ub-PRG complex (PDB 6GZS) (ChlaDUB1 is in cyan and Ub in yellow).

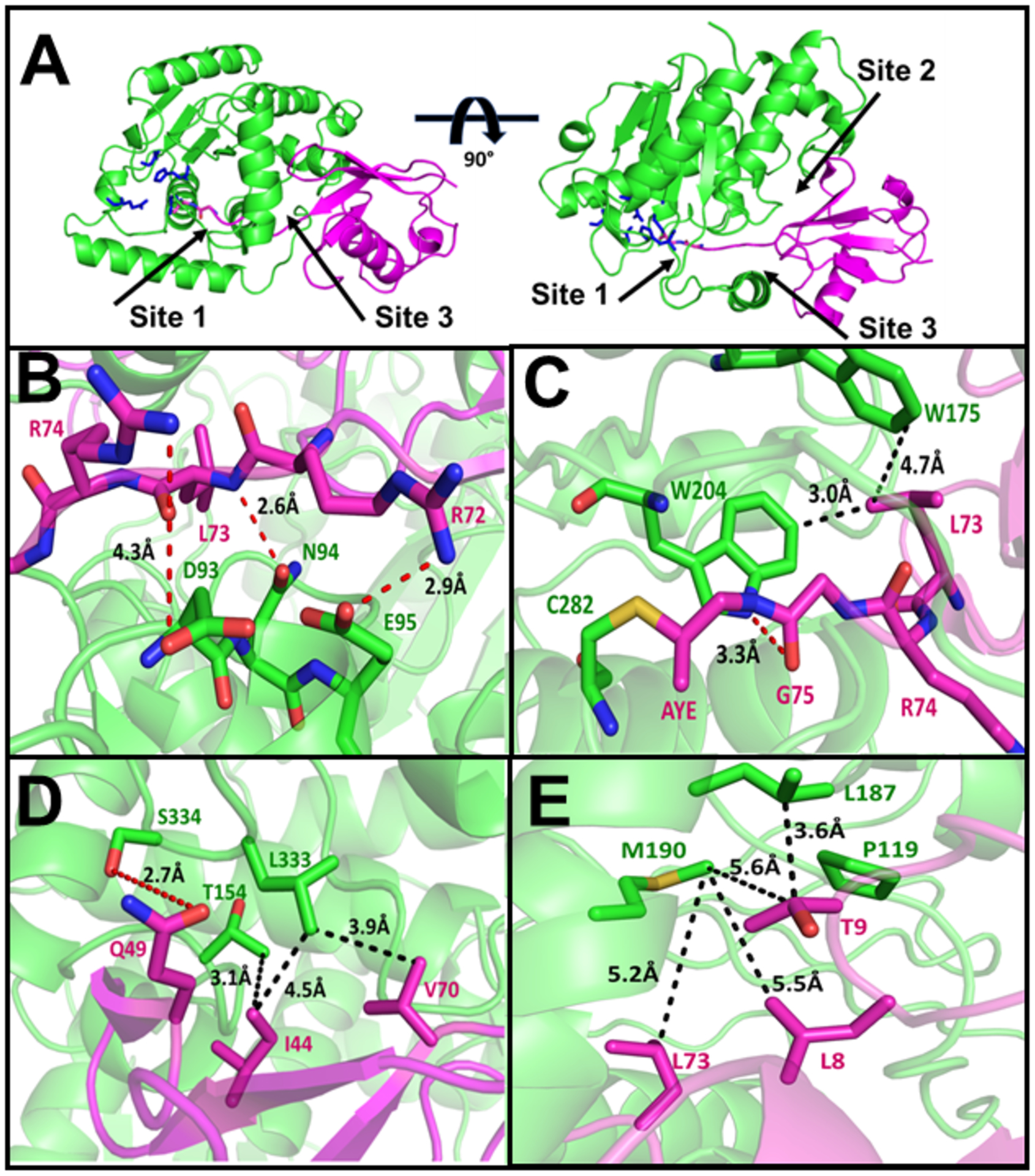

ChlaDUB2 establishes three points of contact with Ub (Fig. 5a, Fig. S8) in the distal site. Site 1, where the C-terminal tail of Ub is held in place by a number of interactions involving the backbone and sidechains atoms of the tail and residues that line up the active-site cleft of the DUB. For example, electrostatic interactions of Asp93 and Glu95 of ChlaDUB2 with Arg72 and Arg74 of Ub, supported by hydrogen bonding from ChlaDUB2Glu95 (Fig. 5b), seem to contribute to productive placement of the tail near the active-site cleft. Gly75 of Ub is recognized through hydrophobic contacts with ChlaDUB2Trp204 that is located near the active site of the DUB. A hydrogen-bonding interaction of the backbone amide group of UbLeu73 with the side chain of ChlaDUB2Asn94 (Fig. 5b,c), with the additional contribution from the hydrophobic contacts of Trp204 and Trp175 of ChlaDUB2 and with the aliphatic sidechain of the same Ub residue, may help stabilize the flexible C-terminal tail of Ub in the active-site cleft of the DUB (Fig. 5c). As mentioned before, due to some areas of the complex having a higher degree of uncertainty in this site, enzyme residues in the distal site were mutated to determine their significance to substrate recognition. These ChlaDUB2 mutants were probed in Ub-AMC hydrolysis assay in order to assess their contribution to Ub recognition. The ChlaDUB2 mutants were also incubated with native-like HA-tagged ubiquitinated substrates isolated from HEK293T cells to assess contribution towards cleavage of polyubiquitinated substrate.

Figure 5.

Structure of ChlaDUB293–339 with ubiquitin propargyl (6OAM). (A) Cartoon representation of ChlaDUB293–339 (TV-green) with ubiquitin propargyl (magenta). Active site residues represented as sticks (blue). (B-E) Sites of interaction between ChlaDUB2 and ubiquitin propargyl with labeled residues displaying hydrogen bonds (red) and van der Waals interactions (black). AYE: allylamine.

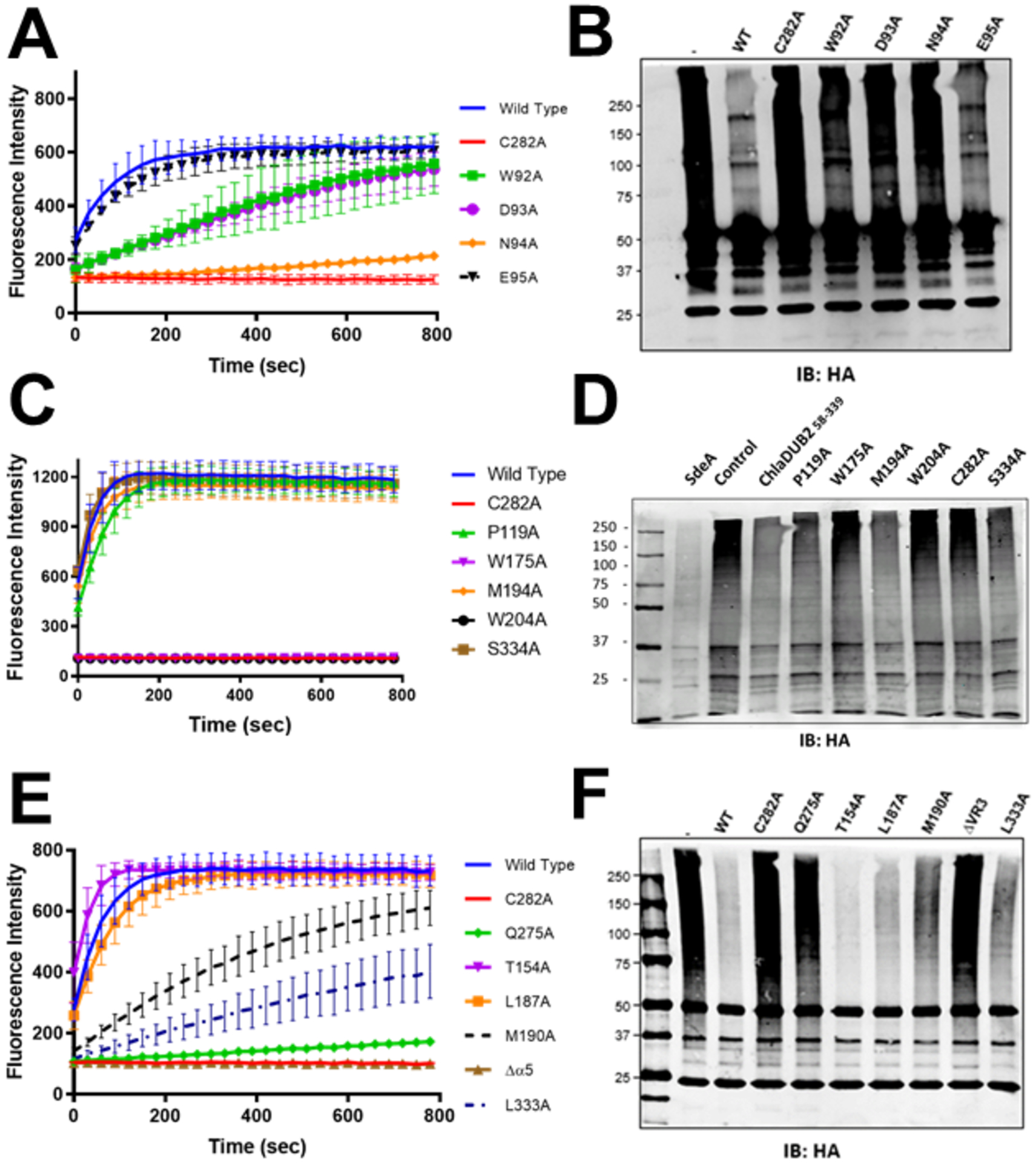

Point mutation of Asp93 and Asn94 to alanine causes a significant decrease in DUB activity with regards to Ub-AMC substrate (Fig. 6a). When incubated with native-like polyubiquitinated substrates, the D93A and N94A mutants were significantly less efficient at cleaving poly-Ub, so was the E95A mutant but to a lesser degree (Fig. 6b). The same E95A mutant did not exhibit a significant difference in activity in the Ub-AMC assay compared to the wild type construct. Mutations of the two tryptophan residues, Trp175 and Trp204, that interact with the backbone of Gly75 and Leu73 of Ub through hydrophobic contacts (Fig. 5c) result in a severe impairment of DUB activity with both Ub-AMC (Fig. 6c) and native-like polyubiquitinated substrates (Fig. 6d). The crystallization construct, ChlaDUB293–339, overall has approximately half of the activity of the longest possible soluble construct used in our experiments, ChlaDUB258–339 (Fig. 1). Thus, it appears that the truncation by nearly 40 residues must have removed some important residues involved in Ub binding. Different truncations from position 58 were therefore generated to assess the minimum length required for full activity. For example, ChlaDUB268–339 and ChlaDUB281–339 both retained similar level of activity compared to the longest construct indicating no loss of critical residues in these constructs (Fig. S9). Sequence alignment revealed a conserved tryptophan between the two ChlaDUBs (Fig. S1) at position 92 (in ChlaDUB2 numbering). According to the structure of ChlaDUB2, Trp92 would be a part of the L1 loop (in agreement with alignment with the ChlaDUB1 structure), possibly making hydrophobic contacts with Gly75 of Ub. To test this, Trp92 was mutated to alanine in the ChlaDUB258–339 construct which resulted in approximately a 50% attenuation in activity towards Ub-AMC (Fig. 6a), also showing reduction of activity towards native-like polyubiquitinated substrates (Fig. 6b). The Ub-AMC hydrolysis activity of this mutant matches that of the ChlaDUB293–339 construct (Fig. 2a) suggesting a role of Trp92 in Ub recognition.

Figure 6.

Mutational analysis. (A, C, E) Mutants of ChlaDUB258–339 (2nM) were incubated with ubiquitin-AMC (500nM) at 37°C. (B, D, F) Cleavage of ubiquitin from polyubiquitinated proteins in HEK293T cells. ChlaDUB258–339 mutants (2μM) were incubated with lysates of HEK293T cells transiently expressing N-terminal HA tagged ubiquitin. Ubiquitinated proteins were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA anti-body. Deubiquitinating activity was observed by blotting with anti-HA antibody.

Site 2 comprises of the L3 and L13 loops of ChlaDUB2 interacting with the Ile44 patch of Ub (Fig. 5d), a hydrophobic patch consisting primarily of Ile44 and Val70 that is commonly used by Ub-interacting proteins. In this contact region, ChlaDUB2Leu333 on the L13 loop rests between the Ile44 and Val70 of Ub contributing nonpolar interactions with the Ile44 patch, augmented by a ChlaDUB2Thr154 and UbVal70 contact. A potential hydrogen bond of 2.9 Å between Ser334 of ChlaDUB2 and Gln49 of Ub (Fig. 5d) also contributes to interactions in this site. Leu333 is a part of a LSWP tetrapeptide motif that is conserved between the two ChlaDUBs indicating a potential importance of this contact site in ChlaDUB2 (Fig. S1). Point-wise mutation of Leu333, Ser334, and Thr154 to alanine revealed a significant decrease in activity for L333A towards both Ub-AMC and polyubiquitinated substrates (Fig. 6e, 6f) while S334A, and T154A retained similar level of activity towards both substrates as the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 6c, 6d, 6e, 6f). Therefore, the interactions between ChlaDUB2Ser334 and UbGln49 and ChlaDUB2Thr154 and UbIle44 seems less important for substrate recognition in solution.

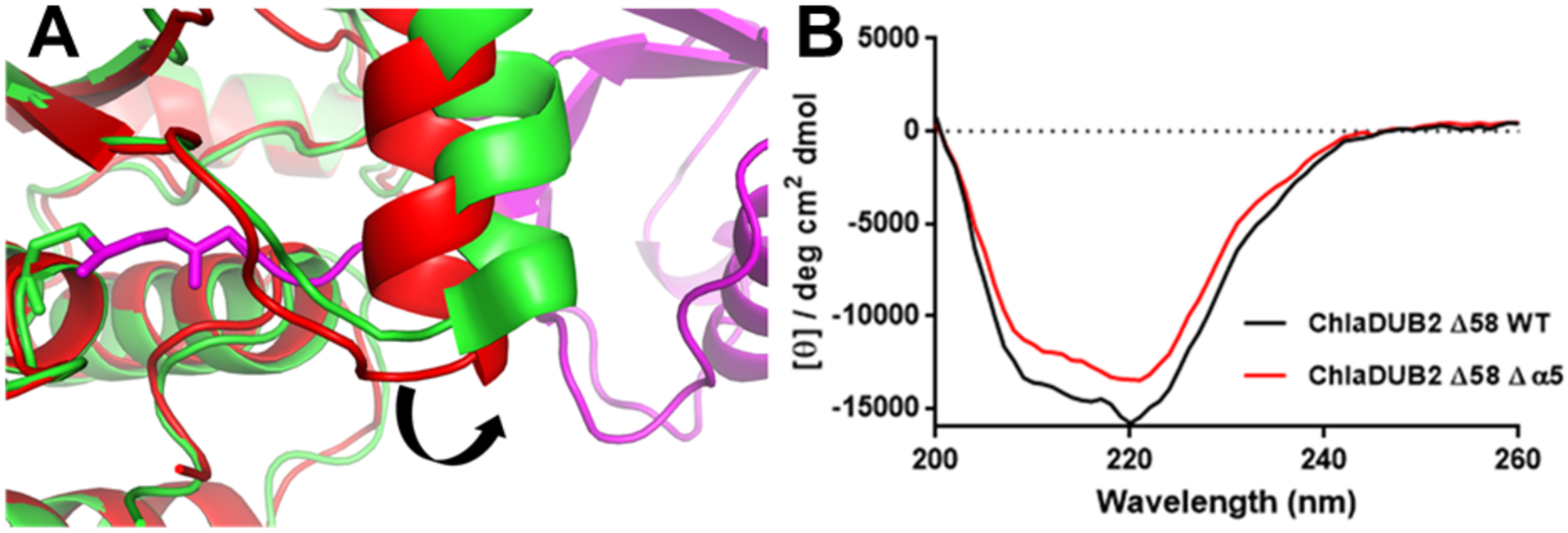

Site 3 involves the N-terminal β-hairpin of Ub interacting with the α5 helix and the L2 loop of ChlaDUB2. This site features interactions similar to the VR3-recogniton element described in a previous work33, 52 on ChlaDUB1 where one face of the α5 helix (VR3-insertion) was shown to engage the Leu8-Thr9 hairpin-turn of Ub. Leu187 and Met190 in the α5 helix of ChlaDUB2 appear to make hydrophobic contacts with Thr9 of Ub, while Pro119 seem to pack against the backbone of Leu8 of Ub providing additional hydrophobic contact (Fig. 5e). Compared to the apo structure, this helix, in ChlaDUB1, shifts position in order to allow entry of the C-terminal tail of Ub to the catalytic site (Fig. 7a). To test its significance in Ub recognition by ChlaDUB2 the entire α5-helix was deleted in a mutant construct. Circular dichroism revealed no significant perturbation of the overall structure when compared to wild type ChlaDUB258–339 (Fig. 7b). Removal of the α5 helix completely ablated activity towards both ubiquitin-AMC and polyubiquitinated substrates. Thus, the loss of activity observed in the helix-deleted mutant construct is not due to any folding defect but due to a loss of Ub recognition. To pinpoint specific residues responsible for interaction with the N-terminal β-hairpin turn of Ub, hydrophobic residues on α5 as well as Pro119 were mutated one at a time. The M190A mutation resulted in a significant decrease in activity towards both substrates (Fig. 6e, Fig. 6f). L187A reduced activity to a lesser extent (Fig. 6e, 6f) and P119A displayed only a slight reduction in activity (Fig. 6c, 6d). Taken together, the interactions in the three sites play important roles in recognizing and holding Ub in the distal binding position in a manner that would promote the placement of the scissile peptide bond at UbGly76 adjacent to the catalytic Cys of the DUB. The overall orientation and manner of recognition of Ub is similar to that of the S1 binding interactions of ChlaDUB1, with an rmsd of 1.36 Å over the entire Ub-bound complex (Fig. 4b).29, 33, 52

Figure 7.

(A) Movement of the α5 helix to accommodate the ubiquitin C-terminus binding to the catalytic site. ChlaDUB293–339 (6MRN, red) and ChlaDUB293–339 (6OAM, TV green). Due to lack of continuous and clear interpretable density for the helix in our structure we used the conformation of the helix in the apo structure of ChlaDUB2 (6MRN) and the visible density in our data to guide us in the modeling the helix. (B) Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of wild type ChlaDUB258–339 and ChlaDUB258–339 Δα5 mutant in which the α5 helix was deleted. Comparison of far-UV CD spectra shows that deletion of the α5 helix did not significantly perturb the overall structure of the enzyme.

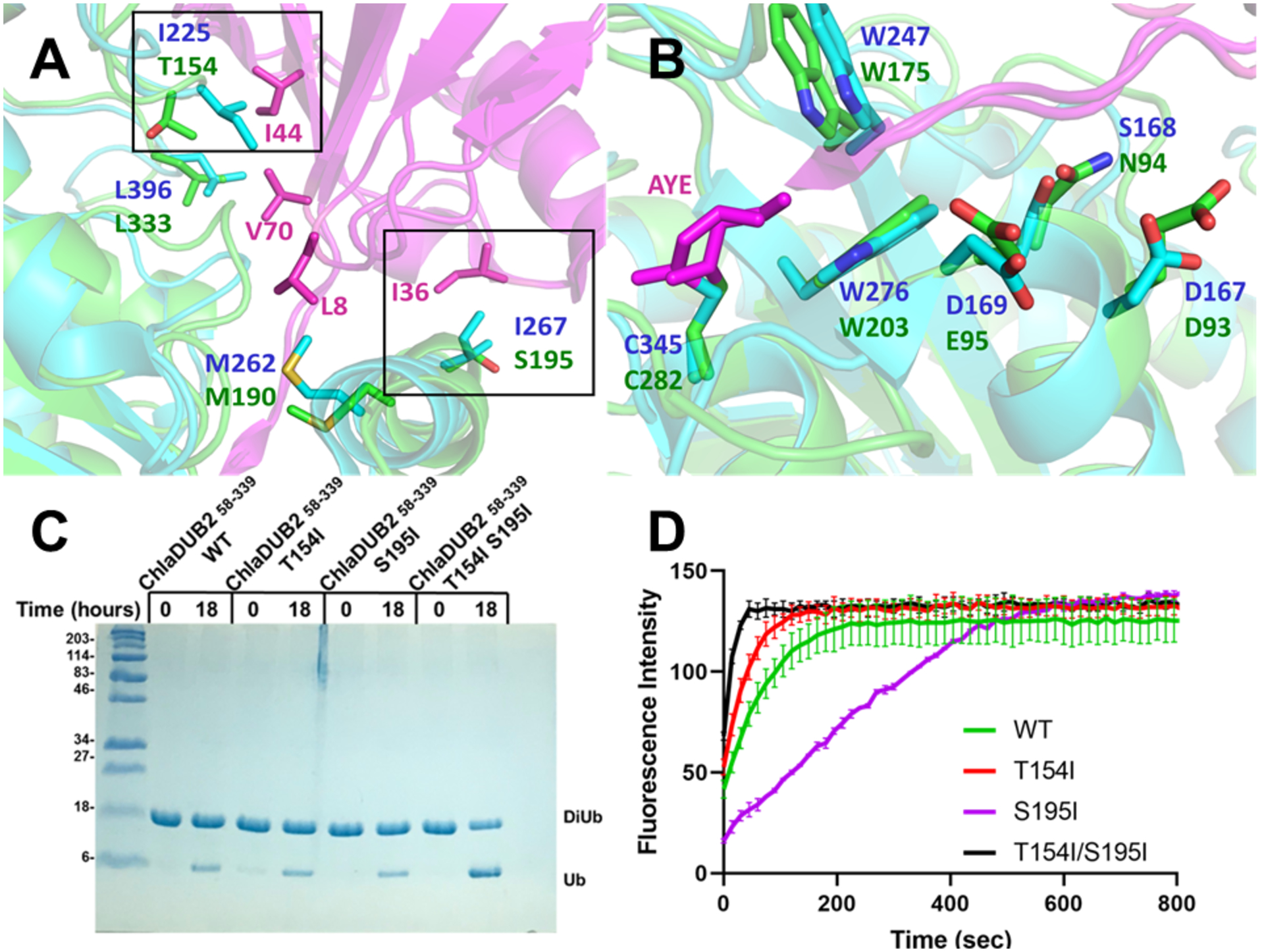

Comparison of distal binding sites of the ChlaDUBs

The distal binding sites of ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2 share several conserved residues for Ub recognition, consistent with similar activities towards ubiquitin-AMC substrate (Fig. 8a, 8b). A notable difference between the ChlaDUBs is the presence of Ile267 on ChlaDUB1 at the C-terminus of the α5 helix, making an important hydrophobic contact with Ile36 of Ub. Mutation of Ile267 to arginine in ChlaDUB1 ablated activity towards both diubiquitin and also disrupts Golgi fragmentation activity33. However, in ChlaDUB2 the equivalent residue is Ser (Ser195) and does not appear to make contact with Ile36 (Fig. 8a). The other key difference in the distal binding site is the presence of Ile225 on ChlaDUB1 engaging Ile44 of Ub. When mutated to alanine, deubiquitinating activity was crippled for ChlaDUB1. However, the equivalent residue for ChlaDUB2 is Thr154, which when mutated to alanine, did not cause a detectable loss in activity (Fig. 6e). To assess the importance of these interactions in the cleavage of diubiquitin substrates, ChlaDUB2 was mutated at Thr154 and Ser195 to isoleucine. Mutation of Ser195Ile caused no gain in activity toward diubiquitin substrates but reduced the activity towards Ub-AMC by nearly half compared to the wild-type enzyme. However, mutation of Thr154Ile caused a slight increase in activity toward both substrates (Ub-AMC and di-Ub) but the when combined with Ser195Ile, the double mutant displayed a further increase in activity. Thus, it appears that Ile225 and Ile267 in ChlaDUB1 contribute to a higher activity toward the diubiquitin substrate compared ChlaDUB2 by virtue of a stronger interaction with Ub at the distal site despite sharing considerable overall similarity in the binding mode.

Figure 8.

Distal ubiquitin binding site of ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2. (A-B) Superposition of ChlaDUB1 bound to ubiquitin propargyl (6GZS, cyan) and ChlaDUB2 bound to ubiquitin propargyl (6OAM, TV green) showing the residues involved in recognition of distal ubiquitin (magenta). Key differences are encapsulated in black boxes. (C) Diubiquitin cleavage assay of ChlaDUB2 with isoleucine mutations. (D) Ubiquitin-AMC assay of ChlaDUB2 with isoleucine mutations.

We further compared the binding properties of the ChlaDUBs via Bio-layer interferometry (BLI) with the diubiquitin substrate. For this analysis, we used the catalytic Cys-to-Ala mutants of the enzymes (please see Methods). The binding curves displayed that both ChlaDUB constructs bind diubiquitin with similar affinity, with ChlaDUB1 displaying a dissociation constant (KD) of ~117 μM and ChlaDUB2 having a KD of ~88.9 μM (Fig. S10). If we assume that Cys-Ala mutants reflect the actual trend with the wild-type enzymes (with catalytic Cys) the BLI results seem to suggest that the two enzymes have similar affinity for the di-Ub substrate (hence similar KM values). Therefore, the difference in activity may be due to ChlaDUB1 having a higher kcat than ChlaDUB2 with regards to the diubiquitin substrate. This is reminiscent of UCHL1 and UCHL3, two very similar enzymes that bind Ub with comparable affinities (and similar KM) but exhibit widely different enzymatic activity toward Ub-AMC due to a difference in kcat53. Thus, it appears that the aforementioned difference in the distal site binding residues between the two enzymes (at positions 154 and 195, ChlaDUB2 numbering) may manifest during interactions made in the transition state rather than substrate binding. Further studies will be required to pinpoint the exact nature of the difference in catalytic activity between the two enzymes toward the diubiquitin substrate.

DISCUSSION

Upon infection, C. trachomatis expresses an arsenal of effector proteins that are recruited to the inclusion membrane54. From there, these inclusion membrane effectors (Incs.) interact with the host in order to harness nutrients or stymie destruction by the host. It is speculated that the function of two of these Incs., ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2, is to remove the Ub from the inclusion membrane to arrest lysosomal fusion and (for ChlaDUB1) stabilize the apoptosis promoter Mcl-132. This process may grant the obligate pathogen enough time to reproduce and move on to other cells. The importance of ChlaDUB1 has been established in prior literature in which mutation of the ChlaDUB1 gene from C. trachomatis causes a significantly reduced bacterial burden in mouse models32. The importance of ChlaDUB2 has yet to be elucidated. The likelihood of both ChlaDUBs having completely redundant function is low, especially with ChlaDUB2 being unable to bind to Mcl-132.

Our findings demonstrate that ChlaDUB1 and ChlaDUB2 have significant differences in their biochemical activity and appear to recognize Ub chains in a different manner, with ChlaDUB2 preferring longer chains of Ub whereas the ChlaDUB1 seems proficient in cleaving ubiquitinated substrates regardless of their length. This difference was observed from a series of assays using substrates with varying lengths of Ub chains. The fact that both ChlaDUBs processed Ub-AMC at a similar rate indicates that the distal binding sites are equivalent in binding Ub despite some differences in residues lining these sites. In particular, Ile225 and Ile267 on ChlaDUB1 makes key interactions with Ile44 and Ile36 of Ub, respectively, which are replaced with Thr154 and Ser195 in ChlaDUB2, respectively. Mutation of Ile225 and Ile267 in ChlaDUB1 significantly reduced deubiquitinating activity33, whereas the equivalent residues in ChlaDUB2 seem to contribute less to Ub recognition at the distal site as their mutation does not lead to the same level of defect seen in ChlaDUB1. Installation of Ile at these positions in ChlaDUB2 results in an appreciable increase in DUB activity toward diubiquitin substrate. Together these amino-acid differences may explain, to some degree, the relative difference in catalytic activity between the two DUBs toward longer ubiquitinated substrates. However, the inability of ChlaDUB2 to recognize and cleave Lys63-diubiquitin efficiently, compared to its CE clan brethren may indicate significant differences in recognition of the proximal Ub which is yet to be determined. ChlaDUB1 contains a long α-helix at the N-terminus of the catalytic construct that is absent in ChlaDUB2 (Fig. S6). This helix may account for the difference in activity between the two enzymes toward diubiquitin and longer poly-Ub substrates. Future studies will shed light into the contribution of the helix to differential activity of the two enzymes. In light of the BLI data, it seems the difference in binding of the proximal Ub between the two enzymes would be more relevant for interactions during transition state (due to a kcat effect rather than a KM effect). Moreover, the distinct gain in catalytic activity of ChlaDUB2 towards longer chains of Lys63-linked poly-Ub larger than diubiquitin entertains the notion of an additional Ub binding site in ChlaDUB2. Since the sequence in the catalytic domains of the two effectors are similar, the presence of an additional Ub binding site in ChlaDUB1 cannot be ruled out, although it seems such a site would be less important in substrate recognition in this DUB.

The aforementioned observations support the hypothesis that ChlaDUB2 may serve a different purpose than that of ChlaDUB1 in cellular DUB activity in addition to a difference in their localization, as seen in Pruneda et. al33, and a difference in substrate targeting (ChlaDUB2 lacks the proline-rich segment found in ChlaDUB1 which is thought to be used in protein-protein interactions). Based on our biochemical observations we propose that ChlaDUB2 may be required for limited trimming of poly-Ub chains rather than complete removal of ubiquitin tags, a task that seems to be handled by ChlaDUB1. It may be desirable to fine tune Ub-based interactions with the host for a balanced infection. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated acetyltransferase activity of ChlaDUB1 in addition to its DUB activity. Certain residues of α5 in ChlaDUB1 facing the catalytic site are involved in substrate recognition underlying the acetyltransferase activity. However, the same residues are not conserved in ChlaDUB2 explaining the lack of acetyl transferase activity of this effector. Thus, ChlaDUB2 was dubbed to be a dedicated DUB unlike ChlaDUB1 which has both activities executed by the same catalytic triad.

Conclusions

The two Chlamydia trachomatis DUBs exhibit distinct biochemical activities despite sharing substantial structural similarity in their catalytic domains. The studies reported herein highlight their differential ability to process poly-Ub chain substrates in a length-dependent manner. While featuring some differences in the binding pocket for the distal Ub, the distinct biochemical behavior observed here seems to rely on interactions with additional, cryptic Ub binding sites, which would be revealed in future through co-crystallization of the DUBs with longer Ub chain substrates. In addition to lacking the acetyl transferase activity of ChlaDUB1 and the proline-rich domain, presumably used for substrate targeting, ChlaDUB2 displays a more controlled deubiquitination activity, the physiological consequence of which under infection conditions remains an open question.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Hidde Ploegh for the full length ChlaDUB1 L2 and ChlaDUB2 L2 constructs and Andreas Martin for the GFP-titin cyclin construct provided for this study. We are grateful for the use of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory at the General Medical Sciences and Cancer Institutes Structural Biology Facility beamlines 23-ID-B and 23-ID-D as well as the staff, Michael Becker and Craig Ogata for their assistance with data collection. The Advanced Photon Source is supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory and is supported by the DOE under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. This publication was made possible by an NIGMS-funded predoctoral fellowship to Sebastian Kenny (T32 GM132024). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS or NIH.

Funding Source

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (GM126296 and T32 GM132024).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

This section provides results of additional experiments and their associated figures (Fig. S1-S10) to support contents of the main article. Sequence alignment of ChlaDUBs highlighting the differences between the two DUBs (Fig. S1). Ub-AMC data emphasizing the similarity of enzymatic activity towards Ub-AMC substrate (Fig. S2). Overnight incubation of ChlaDUBs with diubiquitin substrate (Fig S3). Incubation of ChlaDUBs with diubiquitin and tetraubiquitin (Fig S4). Incubation of ChlaDUBs with HEK293T cell lysate containing 4xFLAG-Nedd8 tagged proteins (Fig S5). Structural alignment of ChlaDUB1 (5HAG) and ChlaDUB2 (6MRN) highlighting similarities in overall topology and active site positioning (Fig. S6). Omit map of α5 helix of ChlaDUB2 (6OAM) validating proper positioning in electron density (Fig S7). 2Fo-Fc electron density map validating positions of key ubiquitin recognition residues on ChlaDUB2 (6OAM) (Fig. S8). Ub-AMC assay comparing enzymatic activity of different lengths of ChlaDUB2 constructs (Fig S9). Bio-layer interferometry binding curves comparing binding affinity of diubiquitin of the ChlaDUBs (Fig S10).

REFERENCES

- [1].Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov RL, Zhao Q, Koonin EV, and Davis RW (1998) Genome Sequence of an Obligate Intracellular Pathogen of Humans: Chlamydia trachomatis, Science 282, 754–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bastidas RJ, Elwell CA, Engel JN, and Valdivia RH (2013) Chlamydial Intracellular Survival Strategies, Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Elwell C, Mirrashidi K, and Engel J (2016) Chlamydia cell biology and pathogenesis, Nature Reviews Microbiology 14, 385–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Subtil A, Delevoye C, Balañá ME, Tastevin L, Perrinet S, and Dautry‐Varsat A (2005) A directed screen for chlamydial proteins secreted by a type III mechanism identifies a translocated protein and numerous other new candidates, Molecular Microbiology 56, 1636–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hybiske K, and Stephens RS (2007) Mechanisms of Chlamydia trachomatis Entry into Nonphagocytic Cells, Infection and Immunity 75, 3925–3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Reynolds DJ, and Pearce JH (1990) Characterization of the cytochalasin D-resistant (pinocytic) mechanisms of endocytosis utilized by chlamydiae, Infection and Immunity 58, 3208–3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Byrne GI, and Moulder JW (1978) Parasite-specified phagocytosis of Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia trachomatis by L and HeLa cells, Infection and Immunity 19, 598–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dautry‐Varsat A, Subtil A, and Hackstadt T (2005) Recent insights into the mechanisms of Chlamydia entry, Cellular Microbiology 7, 1714–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rockey DD, Scidmore MA, Bannantine JP, and Brown WJ (2002) Proteins in the chlamydial inclusion membrane, Microbes and Infection 4, 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Haldar AK, Piro AS, Finethy R, Espenschied ST, Brown HE, Giebel AM, Frickel E-M, Nelson DE, and Coers J (2016) Chlamydia trachomatis Is Resistant to Inclusion Ubiquitination and Associated Host Defense in Gamma Interferon-Primed Human Epithelial Cells, mBio 7, e01417–01416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pilla-Moffett D, Barber MF, Taylor GA, and Coers J (2016) Interferon-Inducible GTPases in Host Resistance, Inflammation and Disease, Journal of Molecular Biology 428, 3495–3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Haldar AK, Foltz C, Finethy R, Piro AS, Feeley EM, Pilla-Moffett DM, Komatsu M, Frickel E-M, and Coers J (2015) Ubiquitin systems mark pathogen-containing vacuoles as targets for host defense by guanylate binding proteins, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, E5628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Al-Zeer MA, Al-Younes HM, Braun PR, Zerrahn J, and Meyer TF (2009) IFN-γ-Inducible Irga6 Mediates Host Resistance against Chlamydia trachomatis via Autophagy, PLOS ONE 4, e4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Auer D, Hügelschäffer SD, Fischer AB, and Rudel T (2019) The chlamydial deubiquitinase Cdu1 supports recruitment of Golgi vesicles to the inclusion, Cellular Microbiology. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [15].Haldar AK, Piro AS, Pilla DM, Yamamoto M, and Coers J (2014) The E2-Like Conjugation Enzyme Atg3 Promotes Binding of IRG and Gbp Proteins to Chlamydia- and Toxoplasma-Containing Vacuoles and Host Resistance, PLOS ONE 9, e86684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nijman SMB, Luna-Vargas MPA, Velds A, Brummelkamp TR, Dirac AMG, Sixma TK, and Bernards R (2005) A Genomic and Functional Inventory of Deubiquitinating Enzymes, Cell 123, 773–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Grabbe C, Husnjak K, and Dikic I (2011) The spatial and temporal organization of ubiquitin networks, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 12, 295–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Eletr ZM, and Wilkinson KD (2014) Regulation of proteolysis by human deubiquitinating enzymes, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1843, 114–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ebner P, Versteeg GA, and Ikeda F (2017) Ubiquitin enzymes in the regulation of immune responses, Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 52, 425–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Komander D, and Rape M (2012) The Ubiquitin Code, Annual Review of Biochemistry 81, 203–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Corn JE, and Vucic D (2014) Ubiquitin in inflammation: the right linkage makes all the difference, Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 21, 297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Komander D, Clague MJ, and Urbé S (2009) Breaking the chains: structure and function of the deubiquitinases, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 10, 550–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Maculins T, Fiskin E, Bhogaraju S, and Dikic I (2016) Bacteria-host relationship: ubiquitin ligases as weapons of invasion, Cell Research 26, 499–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Huibregtse J, and Rohde JR (2014) Hell’s BELs: bacterial E3 ligases that exploit the eukaryotic ubiquitin machinery, PLoS Pathog 10, e1004255–e1004255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Reverter D, Wu K, Erdene TG, Pan Z-Q, Wilkinson KD, and Lima CD (2005) Structure of a Complex between Nedd8 and the Ulp/Senp Protease Family Member Den1, Journal of Molecular Biology 345, 141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shen L. n., Liu H, Dong C, Xirodimas D, Naismith JH, and Hay RT (2005) Structural basis of NEDD8 ubiquitin discrimination by the deNEDDylating enzyme NEDP1, The EMBO Journal 24, 1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sheedlo MJ, Qiu J, Tan Y, Paul LN, Luo Z-Q, and Das C (2015) Structural basis of substrate recognition by a bacterial deubiquitinase important for dynamics of phagosome ubiquitination, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 15090–15095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ronau JA, Beckmann JF, and Hochstrasser M (2016) Substrate specificity of the ubiquitin and Ubl proteases, Cell Research 26, 441–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pruneda Jonathan N., Durkin Charlotte H., Geurink Paul P., Ovaa H, Santhanam B, Holden David W., and Komander D (2016) The Molecular Basis for Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Specificities in Bacterial Effector Proteases, Molecular Cell 63, 261–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Misaghi S, Balsara Zarine R, Catic A, Spooner E, Ploegh Hidde L, and Starnbach Michael N (2006) Chlamydia trachomatis‐derived deubiquitinating enzymes in mammalian cells during infection, Molecular Microbiology 61, 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Le Negrate G, Krieg A, Faustin B, Loeffler M, Godzik A, Krajewski S, and Reed John C (2008) ChlaDub1 of Chlamydia trachomatis suppresses NF‐κB activation and inhibits IκBα ubiquitination and degradation, Cellular Microbiology 10, 1879–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fischer A, Harrison KS, Ramirez Y, Auer D, Chowdhury SR, Prusty BK, Sauer F, Dimond Z, Kisker C, Hefty PS, and Rudel T (2017) Chlamydia trachomatis-containing vacuole serves as deubiquitination platform to stabilize Mcl-1 and to interfere with host defense, eLife 6, e21465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pruneda JN, Bastidas RJ, Bertsoulaki E, Swatek KN, Santhanam B, Clague MJ, Valdivia RH, Urbé S, and Komander D (2018) A Chlamydia effector combining deubiquitination and acetylation activities induces Golgi fragmentation, Nature Microbiology 3, 1377–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Puvar K, Iyer S, Sheedlo MJ, and Das C (2019) Chapter Fifteen - Purification and functional characterization of the DUB domain of SdeA, In Methods in Enzymology (Hochstrasser M, Ed.), pp 343–355, Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Borodovsky A, Kessler BM, Casagrande R, Overkleeft HS, Wilkinson KD, and Ploegh HL (2001) A novel active site‐directed probe specific for deubiquitylating enzymes reveals proteasome association of USP14, The EMBO Journal 20, 5187–5196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Dong Ken C., Helgason E, Yu C, Phu L, Arnott David P., Bosanac I, Compaan Deanne M., Huang Oscar W., Fedorova Anna V., Kirkpatrick Donald S., Hymowitz Sarah G., and Dueber Erin C. (2011) Preparation of Distinct Ubiquitin Chain Reagents of High Purity and Yield, Structure 19, 1053–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shrestha RK, Ronau JA, Davies CW, Guenette RG, Strieter ER, Paul LN, and Das C (2014) Insights into the Mechanism of Deubiquitination by JAMM Deubiquitinases from Cocrystal Structures of the Enzyme with the Substrate and Product, Biochemistry 53, 3199–3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.[] Beckwith R, Estrin E, Worden EJ, and Martin A (2013) Reconstitution of the 26S proteasome reveals functional asymmetries in its AAA+ unfoldase, Nature Structural &Amp; Molecular Biology 20, 1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bryksin AV, and Matsumura I (2010) Overlap extension PCR cloning: a simple and reliable way to create recombinant plasmids, BioTechniques 48, 463–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Otwinowski Z, and Minor W (1997) [20] Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode, In Methods in Enzymology, pp 307–326, Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AGW, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, and Wilson KS (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments, Acta Crystallographica Section D 67, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Vagin A, and Teplyakov A (2010) Molecular replacement with MOLREP, Acta Crystallographica Section D 66, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, and Dodson EJ (2007) Refinement of Macromolecular Structures by the Maximum‐Likelihood Method, Acta Crystallographica Section D 53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Murshudov Garib N, Vagin Alexei A, Lebedev A, Wilson Keith S, and Dodson Eleanor J (2007) Efficient anisotropic refinement of macromolecular structures using FFT, Acta Crystallographica Section D 55, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L-W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, and Zwart PH (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution, Acta Crystallographica Section D 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Vijay-Kumar S, Bugg CE, and Cook WJ (1987) Structure of ubiquitin refined at 1.8Åresolution, Journal of Molecular Biology 194, 531–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Claessen Jasper HL, Witte Martin D, Yoder Nicholas C, Zhu Angela Y, Spooner E, and Ploegh Hidde L (2013) Catch‐and‐Release Probes Applied to Semi‐Intact Cells Reveal Ubiquitin‐Specific Protease Expression in Chlamydia trachomatis Infection, ChemBioChem 14, 343–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bannantine Griffiths, Viratyosin Brown, and Rockey. (2001) A secondary structure motif predictive of protein localization to the chlamydial inclusion membrane, Cellular Microbiology 2, 35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Thomas PD, Huang X, Bateman A, and Finn RD (2017) The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database, Nucleic Acids Research 46, D624–D632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Das C, Hoang QQ, Kreinbring CA, Luchansky SJ, Meray RK, Ray SS, Lansbury PT, Ringe D, and Petsko GA (2006) Structural basis for conformational plasticity of the Parkinson's disease-associated ubiquitin hydrolase UCH-L1, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, 4675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Boudreaux DA, Chaney J, Maiti TK, and Das C (2012) Contribution of active site glutamine to rate enhancement in ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases, The FEBS Journal 279, 1106–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ramirez YA, Adler TB, Altmann E, Klemm T, Tiesmeyer C, Sauer F, Kathman SG, Statsyuk AV, Sotriffer C, and Kisker C (2018) Structural Basis of Substrate Recognition and Covalent Inhibition of Cdu1 from Chlamydia trachomatis, ChemMedChem 13, 2014–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Luchansky SJ, Lansbury PT, and Stein RL (2006) Substrate Recognition and Catalysis by UCH-L1, Biochemistry 45, 14717–14725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Wang X, Stephens RS, and Hybiske K (2018) Direct visualization of the expression and localization of chlamydial effector proteins within infected host cells, Pathogens and Disease 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.