Abstract

IL-15 is a 14–15 kDa member of the four α-helix bundle of cytokines that acts through a heterotrimeric receptor involving IL-2/IL-15R β, γc and the IL-15 specific receptor subunit IL-15R α. IL-15 stimulates the proliferation of T, B and NK cells, and induces stem, central and effector memory CD8 T cells. In rhesus macaques, continuous infusion of recombinant human IL-15 at 20 μg/kg/day was associated with approximately a 10-fold increase in the numbers of circulating NK, γ/δ cells and monocytes, and an 80- to 100-fold increase in the numbers of effector memory CD8 T cells. IL-15 has shown efficacy in murine models of malignancy. Clinical trials involving recombinant human IL-15 given by bolus infusions have been completed and by subcutaneous and continuous intravenous infusions are underway in patients with metastatic malignancy. Furthermore, clinical trials are being initiated that employ the combination of IL-15 with IL-15R α+/− IgFc.

Keywords: CD40, γc IL-2, IL-2/IL-15R β, IL-15, IL-15 receptor α, malignant melanoma, renal cell cancer

Over the past decade, immunotherapy has joined surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy as a pivotal element in the treatment of cancer [1]. Immunological approaches include monoclonal antibodies and more recently chimeric antigen receptor (CAR-T) that directly attack tumor cells [2–4]. In other strategies, the goal of cancer immunotherapy is to stimulate the host’s immune system to attack cancer cells. This approach is based on the premise that the host is making an immune response, albeit inadequate, to its cancer cells. In this arena, immunostimulatory anticheckpoint monoclonal antibodies including the anti-CTLA-4 ipilimumab and anti-PD1/PD-L1 have yielded improved patient survival [5,6]. In addition, several recombinant cytokines and hematopoietic growth factors have been approved for use as supportive agents in cancer therapy. Recombinant IL-2 is a prototypic immunotherapeutic agent approved for patients with metastatic malignancy [7]. Despite its accepted role IL-2 has negative effects. IL-2 has a dual role as an immunomodulator that stimulates proliferation of effector cells that kill cancer cells but also checkpoint cells that suppress the immune response by maintenance of inhibitory CD25+Foxp3+T regulatory cells (Tregs) and that participate in activation-induced cell death (AICD) [8,9]. Furthermore, IL-2 is associated with a serious capillary leak syndrome. These issues prompted the search for other immunotherapeutics with the benefits of IL-2 but with fewer negative side effects. It was proposed that IL-15 has favorable characteristics that could make it more effective and less toxic than IL-2 in the immunotherapy of metastatic malignancy [10–15]. In particular, IL-15 facilitates the proliferation and synthesis of immunoglobulin by activated B cells [16]. In addition, IL-15 is pivotal in mice in the generation and maintenance of NK cells; is antiapoptotic in several systems; and supports the survival of stem, central and effector CD8 memory T cells, thereby playing a critical role in the maintenance of long-lasting, high-affinity T-cell immune responses to invading pathogens [10–15,17–20]. Furthermore, in contrast to IL-2, IL-15 inhibited IL-2-mediated AICD, less consistently activated Tregs and did not cause a major capillary leak syndrome in mice or in nonhuman primates [10].

IL-15 molecular biology & expression

IL-15 is a 14–15 kDa glycoprotein encoded on chromosome 4q31 [21–23]. The human IL-15 gene comprises nine exons and four introns. There are two isoforms of IL-15 mRNA that differ in their signal peptides. One isoform consists of a 316-bp 5′-UTR, a 486-bp coding sequence and a 400-bp 3′-UTR that is translated into an IL-15 precursor protein with a long-signal peptide of 48 amino acids [24]. The other isoform of IL-15 mRNA has a short-signal peptide of 21 amino acids. Both isoforms produce the same mature protein. However, the two isoforms differ in their intracellular trafficking pattern. The IL-15 long-signal peptide is targeted to the Golgi apparatus, endosomes and the endoplasmic reticulum secretory pathway, whereas IL-15 short-signal peptide is not secreted but appears to be restricted to the cytoplasm and the nucleus [24].

IL-15 mRNA is expressed by a large number of tissues; however, IL-15 protein is largely limited to monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) [10,25–27]. Thus, although regulation of IL-15 protein production occurs at transcription, most of the control of its protein expression is at the level of translation [13,25–28]. Transcription of IL-15 is stimulated by type I and II interferons, CD40 ligation as well as Toll-like receptor stimuli such as lipopolysaccharide. Lucas and coworkers demonstrated that interferon type I signals by DCs and the subsequent production and trans-presentation of IL-15 by DCs to resting NK cells was necessary and sufficient for priming of NK cells [29]. Translation is impeded by multiple AUG sequences in the 5′-UTR, a long-signal peptide and a negative regulatory element in the C-terminus of the coding sequence of the mature protein that act to limit this process [25,26]. This tight regulation of IL-15 expression is required because of its potency as an inflammatory cytokine that induces TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, IL-6 and other inflammatory cytokines [30].

IL-15 receptor molecular biology

The heterotrimeric IL-15 receptor is composed of the β subunit (IL-2R/IL-15R, CD122) shared with the IL-2 receptor [10,11,22]; the common gamma (γc) subunit (CD132) shared with IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9 and IL-21; and a private IL-15 specific α subunit, IL-15R α [31–33]. The IL-15R α receptor has a 173-amino acid extracellular domain, a single 21-amino acid transmembrane region and a 37-amino acid cytoplasmic domain [10,12,13,31,32]. The human IL-15R α gene maps to chromosome 7 with over ten alternative isoforms [31,33]. It is made up of eight exons which as a result of alternative splicing can produce multiple isoforms of IL-15R α [32].

Biological functions of IL-15

As a consequence of their sharing receptor components IL-2R/IL-15R β and γc and use of common JAK (JAK1, JAK3) STAT (STAT3, STAT5) signaling molecules, IL-2 and IL-15 share several functions. These functions include stimulation of the proliferation of activated CD4−CD8−, CD4+CD8+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [10,11,13,34]. Furthermore, the two cytokines facilitate the induction of cytotoxic lymphocytes and augment the proliferation and immunoglobulin synthesis by B cells that have been costimulated with an IgM-specific antibody or by ligation of CD40 [16]. IL-2 and IL-15 also stimulate the generation, proliferation and activation of NK cells [17,35]. In addition to these similarities, there are distinct differences between the functions of IL-15 and IL-2. IL-2 has a unique role in the prevention of T-cell-mediated immune responses to self. This function is explained by the fact that IL-2 is required to maintain the fitness of Fox forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) expressing Treg cells [9]. By contrast, IL-15 expression has no marked effects on Treg cells. IL-2 also has a crucial role in AICD, a process that leads to the elimination of self-reactive T cells, whereas IL-15 is an antiapoptotic agent wherein IL-15-transgenic mice have an inhibition of IL-2-induced AICD [20]. In contrast to IL-2, IL-15 has as its unique role the maintenance of a long-lasting immune response to invading pathogens. In particular, IL-15 promotes the maintenance of CD8+ CD44hi memory phenotype T cells [10,11,18,19]. These observations from ex vivo functional studies are supported by an examination of mice with disrupted cytokine or cytokine receptor genes. IL-2 and IL-2R-deficient mice develop a marked enlargement of peripheral lymphoid organs that is associated with the polyclonal expansion of T and B populations [36]. These expanded populations are associated with impairments in Treg development and AICD. Furthermore, IL-2R α deficient mice develop autoimmune diseases such as hemolytic anemia and inflammatory bowel disease [36]. In contrast to these observations with IL-2, IL-15 and IL-15R α deficient mice do not develop lymphoid enlargement, increased serum immunoglobulin concentrations or autoimmune disease [37]. Rather IL-15-deficient mice have a marked reduction in the number of peripheral NK cells, NK T cells, γ/δ T cells and intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes [37]. In contrast to the situation in mice, homeostasis of human NK cells is not IL-15 dependent although IL-15 does augment proliferation and activation of NK cells in humans [38]. In addition to its effects on T and NK cells, IL-15 also protects neutrophils from apoptosis, modulates phagocytosis and simulates the secretion of IL-8 and IL-1R antagonists by these cells [13]. IL-15 suppresses human neutrophil apoptosis through the action of several kinases including JAK2, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinases-1/2 [34,39–41]. In addition, IL-15 has a role in the action of the antiapoptotic Mcl-1 protein [41]. Furthermore, DCs stimulated by IL-15 demonstrate maturation and increased CD83, CD86, CD40 and MHC Class II expression [13,41].

Interaction of IL-15 with its receptor & receptor signaling

IL-15 and IL-15R α are coexpressed on monocytes and DCs following activation with interferon or CD40 ligation and Toll-like receptor activation with agents such as lipopolysaccharide that in turn induce interferon expression [42,43]. IL-15 binds to IL-15R α with high-affinity Kd >10−11 M. Following activation-mediated coexpression in DCs, IL-15 and IL-15R α remain together on the cell surfaces, recycle through endosomal vesicles and reappear on the cell surfaces so that the combination is coexpressed for many days [43]. Dubois and coworkers and then others discovered that the IL-15R α on DCs trans-presents IL-15 to effector NK and CD8 T cells as part of an immunological synapse [43–48]. IL-15 is trans-presented to cells that express IL-2R/IL-15R β and γc but not IL-15R α. In lymphocytes, the binding of IL-15 in trans to the IL-2/IL-15R β and γc heterodimer induces JAK1 activation that subsequently phosphorylates STAT3 via the β chain and JAK3 and STAT5 via its γ chain [10–13,34]. Sathe and coworkers demonstrated a nonredundant pathway linking IL-15 via STAT5 phosphorylation and subsequent binding to the 3′ UTR of Mcl1 that is involved in the maintenance of NK cells and innate immune responses [42]. In an additional IL-15 signaling mechanism, the adapter protein Shc binds to a phosphotyrosine residue on IL-2/IL-15R β resulting in the activation of Grb2 and AKT via the Shc, Grb2, Gab2, PI3K, AKT and mTOR signaling pathway. Marcais and coworkers demonstrated that the metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR is essential for IL-15 signaling during the development and activation of NK cells [49]. Low doses of IL-15 triggered only phosphorylation of the transcription factor STAT5, whereas high concentrations of IL-15 utilized the metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR, stimulated the growth and nutrient uptake of NK cells and positively fed back on the receptor for IL-15 [49]. In a third signaling pathway, IL-15 trans-presentation is associated with activation of Grb2 and SOS to form a Grb2/SOS complex that in turn activates the RAS–RAF pathway that then activates the MAPK pathway involved in cellular proliferation [12,13]. Collectively these signaling pathways induce expression and activation of c-myc, c-fos, c-jun, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and NF-kB [12,13].

In addition to its dominant trans-presentation, IL-15 can also signal in cis onto cells that express IL-15R α in addition to IL-2/IL-15R β and the common γ chain [50–56]. Cells normally bearing the β and γ chain transfected with IL-15R α were shown to efficiently signal in cis through IL-15R α and the IL-2R β/γc expressed on the surface of a single cell. With cells bearing only IL-2R/IL-15R β and γc, the addition of soluble IL-15R α facilitated IL-15 activity, whereas soluble IL-15R α inhibited the proliferative capacity of cis expressing heterotrimeric IL-15 receptors [50,55].

Ota and coworkers demonstrated that there is no requirement for trans-presentation of IL-15 for human CD8 T-cell proliferation [54]. Furthermore, the humanized monoclonal antibody Mik-Beta-1 directed toward IL-2/IL-15R β blocked IL-15 trans-presentation but did not inhibit IL-15 receptor action in cis [52]. In addition, in immunophysiological studies examining the ability of IL-15 expressed by a vaccine vector to influence the response induced, it was demonstrated that the presence of IL-15 during the immune-induction phase resulted in long-lasting CD8+ memory T cells due to an increased expression of IL-15R α [53]. The results are consistent with the ability of IL-15R α on T cells themselves to present in cis and augment the T cells’ responsiveness to IL-15 in addition to the known ability of IL-15R α on APCs to present IL-15 to T cells in trans [53]. Furthermore, Zanoni and coworkers demonstrated that IL-15 cis presentation is required for optimal NK cell activation in lipopolysaccharide-mediated inflammatory conditions [55]. Escherichia coli exposure of DCs led to IFN-β enhancement of NK-cell activation by inducing expressions of IL-15 and IL-15 receptor α not only in DCs but surprisingly also in NK cells. This process allows the transfer of IL-15 onto NK cell surfaces and its cis presentation. cis-presented NK cell-derived and trans-presented DC-derived IL-15 contributed equally to optimal NK cell activation [55].

In addition to the classical heterotrimeric IL-15 receptor JAK1, JAK3, STAT3/STAT5 pathway, there are novel receptor signaling transduction pathways for IL-15 in mast cells [57]. IL-15 signaling in mast cells does not involve IL-2/IL-15R β or the common γ chain rather it involves distinct receptors. Furthermore, mast cell IL-15 receptors recruit JAK2 and STAT5 instead of JAK1/3 and STAT3/5 that are activated in T cells. Finally, a number of groups have reported that in the absence of the common γ chain and independently of IL-2/IL-15R β and JAK/STAT signaling that IL-15 can signal via IL-15R α, JNK and NK-kB to drive RANTES production by myeloid cells [56,58,59]. Other groups have also demonstrated that IL-15R α is competent for IL-15-mediated signal transduction contrary to what was previously reported.

The efficacy of IL-15 in murine models of neoplasia

A number of studies in murine models suggested that IL-15 may prove to be of value in the therapy of neoplasia [10–14,60–67]. In particular, whereas following intravenous administration of MC38 syngeneic colon carcinoma cells wild-type B6 mice died of pulmonary metastases within 6 weeks, IL-15 transgenic mice survived for more than 8 months following infusion of the tumor cells [61]. Furthermore, Klebanoff and coworkers demonstrated that IL-15 enhanced the in vivo activity of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells in the T-cell receptor transgenic mouse (pmel-1) whose CD8+ T cells recognized an epitope derived from the melanoma antigen gp100 [14]. Huntington and coworkers evaluated IL-15 in the HIS mouse model that involved engraftment of newborn BALB/c Rag2−/− γc−/− mice with human hematopoietic stem cells from fetal liver or cord blood which generates human innate and adaptive lymphocytes and DCs required for the immune response [68,69]. Trans-presented murine IL-15 inefficiently triggered human NK cells providing an explanation for the poor human NK cell reconstitution in HIS mice. This group also evaluated exogenous administration of a potent human IL-15R agonist (RLI) consisting of human IL-15 covalently linked to an extended human IL-15R α ‘sushi’ domain thus mimicking IL-15 trans-presentation. This agent was sufficient to restore human NK cell development in HIS mice. Furthermore, Bessard and coworkers demonstrated high antitumor activity of RLI, the IL-15-IL-15R α fusion protein in metastatic melanoma and colorectal cancer models in mice supporting the use of RLI as an adjuvant/therapeutic for human clinical trials [70]. In the studies of Yu [67] and Zhang [65,66], IL-15 was shown to prolong the survival of mice with established PC26, MC38 colon cancer and with TRAMP-C2 prostate cancers. On the basis of the animal and laboratory trials with IL-15, great interest was generated among leading immunotherapeutic experts participating in the NCI Immunotherapy Agent Workshop who ranked IL-15 as the most promising unavailable immunotherapeutic agent to be brought to therapeutic trials [71].

Toxicity, pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity & impact on elements of the normal immune system of recombinant human IL-15 in rhesus macaques

The safety of IL-15 was evaluated in mice and in rhesus macaques [62,72–76]. Munger et al. [62] administered 30, 60 or 180 μg of recombinant simian IL-15 by intraperitoneal injection to C57BL/6 mice three-times per day for nine doses. Mice receiving IL-15 at 180 μg demonstrated only a minimal vascular leak syndrome suggesting that this toxicity would not be dose limiting in human IL-15 trials. Mueller et al. [72] injected simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques with recombinant IL-15 at doses of 10 or 100 μg/kg twice weekly subcutaneously for 4 weeks [72]. IL-15 induced a nearly threefold increase in the number of peripheral CD8+CD3− NK cells. All clinical laboratory results remained within normal limits with the exception of a nonsignificant increase in the number of circulating platelets. Berger et al. [76] administered human recombinant IL-15 to rhesus macaques at doses of 2.5–15 μg/kg daily by subcutaneous injection for up to 14 days [76]. A second set of macaques received IL-15 every 3 days at doses of 2.5, 5 or 10 μg/kg for 24 days. Daily administration of IL-15 for up to 14 days caused reversible severe neutropenia, anemia, weight loss, a generalized skin rash and a massive expansion of T cells. The bone marrow of a single neutropenic animal was found to be hypocellular.

Recombinant human IL-15 (rhIL-15) produced by the Biopharmaceutical Development Program NCI was administered at a dosing schedule of 12 daily intravenous bolus infusions at doses of 10, 20 and 50 μg/kg/day [73,74]. The only biologically meaningful laboratory abnormality was a grade 3/4 transient neutropenia. This neutropenia was shown to be secondary to a redistribution of neutrophils in that bone marrow examinations demonstrated increased marrow cellularity including cells of the neutrophil series [73]. Furthermore, neutrophils were observed in sinusoids of markedly enlarged livers and of spleens suggesting IL-15-mediated neutrophil redistribution from the circulation to the tissues. In accord with this view, Verri and coworkers demonstrated that following intraperitoneal administration of IL-15, there was a cascade of cytokines in the order of IL-18, MIP-1-α, MIP-1-β and TNF-α that was associated with a redistribution of neutrophils from the circulation to the peritoneal cavity [77].

A 12-day bolus of intravenous administration of 20 μg/kg/day of IL-15 to rhesus macaques was associated with a 4- to 8-fold increase in the number of circulating NK and stem, central and effector memory CD8 T cells [73–75]. Subsequently, alternative routes of administration were evaluated in rhesus macaques including continuous intravenous infusion (CIV) and subcutaneous administration of IL-15 [75]. The administration of IL-15 by CIV at 20 μg/day for 10 days led to an approximately 10-fold increase in the number of circulating NK cells and a massive 80- to100-fold increase in the number of circulating effector memory CD8 T cells [75].

Subcutaneous infusions at 20 μg/kg/day for 10 days led to a more modest 10-fold expansion in the number of circulating effector memory CD8 T cells [75]. In contrast to observations with daily administration of IL-15, subcutaneous infusions of 20 μg/kg/day twice weekly were not associated with an increase in the number of total circulating lymphocytes or effector memory CD8 T cells [75]. No vascular leak syndrome, hemodynamic instability or renal failure was observed in these studies. In addition, no animal developed autoimmune disorders or antibodies to the infused IL-15.

Clinical trials using IL-15 in the treatment of cancer

Five clinical trials have been initiated using E. coli rhIL-15 in the treatment of cancer (Table 1). The primary goal of the completed trial: ‘A Phase I study of intravenous recombinant human IL-15 in adults with refractory metastatic malignant melanoma and metastatic renal cell cancer’ [78] to determine the safety, adverse event profile, dose limiting toxicity and maximum tolerated dose of rhIL-15 administered as a daily intravenous bolus infusion for 12 consecutive days in subjects with metastatic malignant melanoma or metastatic renal cell cancer [79]. This first in-human trial utilized E. coli-produced rhIL-15. The study was initially designed as a Phase I dose-escalation trial starting with an initial dose of 3 μg/kg/day for 12 days. However, after the initial patient developed grade 3 hypotension and another patient developed grade 3 thrombocytopenia the protocol was amended to add two lower doses 1.0 and 0.3 μg/kg/day. Two of four patients given the 1.0 μg/kg/day dose had persistent grade 3 alanine aminotransferase (ALT), AST elevations that were dose limiting. All nine patients with IL-15 administered at 0.3 μg/kg/day received all 12 doses without dose-limiting toxicity. The maximum tolerated dose of rhIL-15 was determined to be 0.3 μg/kg/day.

Table 1.

Clinical trials using IL-15 in cancer immunotherapy.

| Clinical trial | Government clinical trials identifier | Disease + dosing strategy | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Phase I study of intravenous recombinant human IL-15 in adults with refractory metastatic malignant melanoma and metastatic renal cell cancer | NCT01021059 | Phase I study with 12 daily bolus intravenous infusions in 18 patients with melanoma or renal cell cancer | This study has been completed | [78] |

| Recombinant interleukin-15 in treating patients with advanced melanoma, kidney cancer, non-small cell lung cancer or squamous cell head and neck cancer | NCT01727076 | Melanoma, kidney, non-small cell lung cancer, squamous cell head and neck cancer. This Phase I study involves subcutaneous IL-15 daily on days 1–5 and 8–12 |

Currently recruiting patients | [82] |

| Continuous infusion of rhIL-15 for adults with advanced cancer | NCT01572493 | Metastatic carcinoma. This is a Phase I study of ten daily continuous intravenous infusions of rhIL-15 | Currently recruiting patients | [84] |

| Haploidentical donor of natural killer cell infusion with IL-15 in acute myelogenous leukemia | NCT01385423 | Acute myelogenous leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome. This is a Phase I study of rhIL-15 given after haploidentical donor NK cells | Currently recruiting patients | [85] |

| Use of IL-15 after chemotherapy and lymphocyte transfer in metastatic melanoma | NCT01369888 | Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in rhIL-15 in the treatment of melanoma | This study is closed | [104] |

rhIL-15: Recombinant human IL-15.

There was a consistent temporal pattern of post-treatment adverse events in patients given the 3 μg/kg/day dose with fever beginning 2.5–4 h following the start of rhIL-15 infusions. Rigors occurred at approximately the 1.5–2 h time point and blood pressure dropped to a nadir of approximately 20 mm Hg below pretreatment levels. These changes were concurrent with maximum up to 50-fold elevations of circulating IL-6 and IFN-γ. In studies with chimeric antigen receptors, such symptoms could be reversed by the administration of an anti-IL-6R a monoclonal antibody [80,81]. The patients had evidence of only modest capillary leak. None of the patients produced antibodies to rhIL-15. The pharmacokinetics of rhIL-15 for 3.0, 1.0 and 0.3 μg/kg/day resulted in Cmax of 47,800, 15,900 and 12,060 respectively. The survival half-lives (t1/2) were very similar for the three dose levels 2.4, 2.7 and 2.7 h.

Flow cytometry of peripheral blood lymphocytes revealed an efflux of NK and memory CD8 T cells from the circulating blood within minutes upon IL-15 administration, followed by influx and hyperproliferation yielding 10-fold expansion of NK cells that ultimately returned to baseline [79]. Furthermore, there were significant increases in γ/δ and CD8 memory T cells. In this first in-human Phase I trial, there were no responses with stable disease as a best response. However, five patients manifested a decrease between 10 and 30% in their marker lesions and two patients had clearing of lung lesions.

Development of alternative dosing strategies

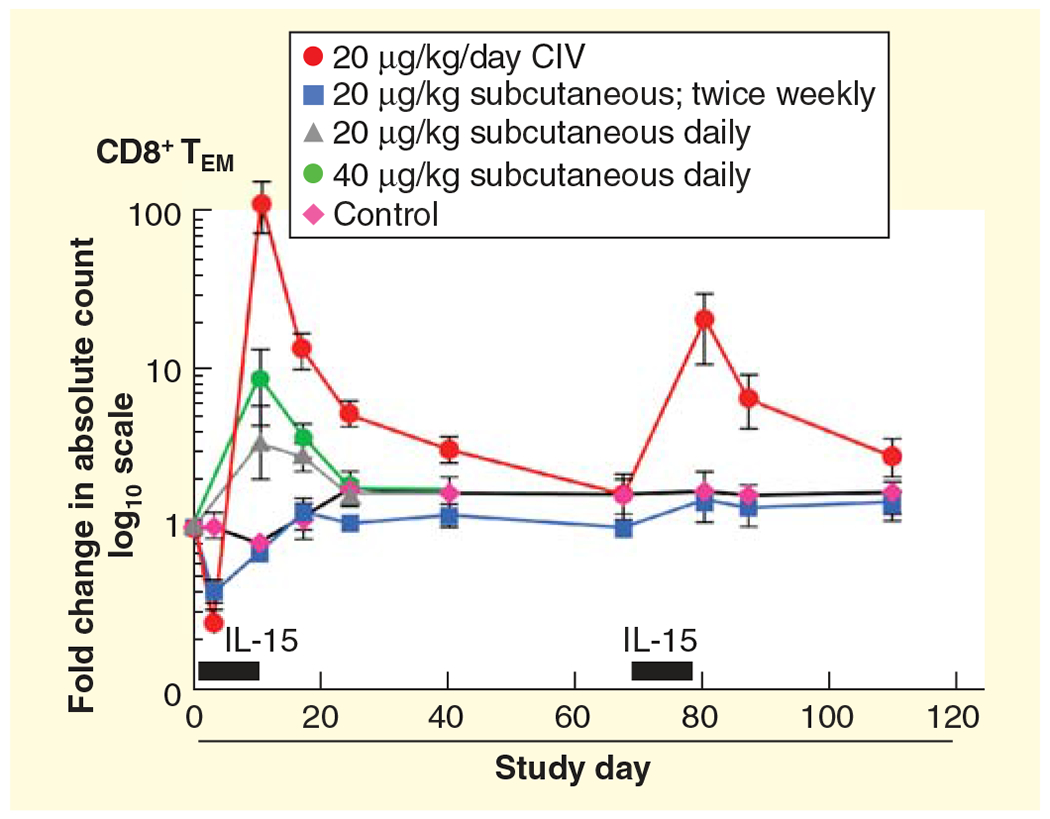

It was concluded that although IL-15 could be safely administered to patients with metastatic malignancy, rhIL-15 was not optimal when administered as an intravenous bolus due to an intense cytokine secretion and the macrophage activation syndrome that occurred in the first few hours after treatment. There were exceedingly high IL-15 Cmax levels initially following bolus infusions that were sufficient to signal through the IL-2/IL-15R β and γc receptor pair that IL-15 shares with IL-2 thereby contributing to the toxicity observed [79]. To reduce the Cmax obtained and to increase the period of time when IL-15 was at an optimal concentration for high-affinity IL-15 receptors, alternative receptor dosing strategies in nonhuman primate rhesus macaques were evaluated Figure 1 [75]. By administering IL-15 by CIV or subcutaneously, the exceedingly high Cmax observed with bolus infusions could be avoided. With bolus intravenous infusion to rhesus macaques at 20 μg/kg/day the Cmax was 720 ng/ml; with subcutaneous infusions at this dose the Cmax was 50 ng/ml; whereas with CIV of this dose per day the Cmax was between 2 and 4 ng/ml throughout the 10-day study [73,75]. Furthermore, the efficacy was greatest with CIV bolus infusions. In contrast to the four- to eightfold expansion of CD8 TEM cells observed with bolus administration, CIV rhIL-15 infusions were associated with an 80- to 100-fold expansion of circulating CD8 TEM cells in rhesus macaques [75]. Subcutaneous IL-15 at 20 μg/kg/day resulted in a more modest 10-fold expansion of CD8 T-effector memory cells [75]. To translate these preclinical trials with the goal of reducing Cmax, the excess cytokine release and the macrophage activation syndrome events two additional clinical trials were initiated. These trials include the clinical trial: ‘Recombinant interleukin-15 in treating patients with advanced melanoma, kidney cancer, non-small cell lung cancer or squamous cell head and neck cancer’, [82], supported by the NCI and the Cancer Immunotherapy Trials Network, wherein at five sites recombinant IL-15 is being administered subcutaneously daily on days 1–5 and 8–12 in a study involving patients with advanced melanoma, kidney cancer, non-small cell lung cancer or squamous cell head and neck cancer [83]. Treatment repeats every 28 days for up to four courses in the absence of unacceptable toxicities are permitted. Three patients have been enrolled in each of the 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 μg/kg per dose cohorts [83]. Among 12 patients treated, there was only one serious adverse event, grade 2 pancreatitis in a metastatic melanoma patient that began 3 days after completing cycle one treatment at 2.0 μg/kg [83]. Flow-cytometric data indicated a consistent increase in the frequency of circulating CD3+CD56+ NK cells. In addition, in the study [84] being performed at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center there is an evaluation of ‘continuous infusion of rhIL-15 for adults with advanced cancer.’ This study involves a dose escalation of IL-15 provided by CIV to patients with cancer for whom there is no remaining effective curative treatment available. In addition to these trials [85], ‘Haploidentical donor of natural killer cell infusion with IL-15 in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML)’ is recruiting participants [86]. This is a single-center (Masonic Cancer Center – University of Minnesota), modified standard design dose-escalation study designed to determine the maximum tolerated, minimum efficacious dose of IL-15 (intravenous recombinant human IL-15) and incidence of donor NK cell expansion by day +14 when given after haploidentical donor NK cells in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myelogenous leukemia.

Figure 1. IL-15 was administered for 10 days using four different dosing strategies.

The control group received 5% dextrose by CIV for 10 days. Each point corresponds to the mean ± SEM and indicates the fold change in the absolute count relative to the pretreatment (day −4). Gray bars above the x-axis represent the duration of IL-15 administration. The rhesus macaques received 20 μg/kg/day of IL-15 by CIV (red dots), subcutaneously daily 40 μg/kg/day (green circles), subcutaneously daily 20 μg/kg/day (gray triangles) or subcutaneously twice weekly (blue squares).

CIV: Continuous intravenous infusion; SEM: Standard error of the mean. This research was originally published in [75].

IL-15/IL-15R α

Although IL-15 administration may show efficacy in the treatment of metastatic malignancy in human clinical trials, it has not been optimal when used as a single agent for cancer therapy. A particular challenge is that there is only a low-level expression of IL-15R α on resting DC cells [87]. As noted above, for its long-term persistence and its optimal activation of NK and CD8+ T cells, IL-15 is predominantly expressed bound to IL-15R α on the surface of DCs where IL-15 is trans-presented to effector NK and CD8 T cells that express IL-2/IL-15R β and γc but not IL-15R α [43–48]. Indeed, the true IL-15 cytokine may not be an IL-15 monomer but rather may be considered as an IL-15R α/IL-15 heterodimeric cytokine [70,88–93]. Physiologically, IL-15 is produced as a heterodimer in association with IL-15R α. Furthermore, in mice it is the heterodimer alone that is stably produced and transported to the surface of the cell [94,95]. On cleavage, IL-15R α/IL-15 elements are associated in the serum as the sole form of circulating IL-15 [87,89,95]. The heterodimeric IL-15R α/IL-15 can be efficiently produced in a mammalian system, whereas this has not been true for monomeric IL-15. The recombinant form of IL-15R α/IL-15 has a larger overall size and when produced in a mammalian system is glycosylated in contrast to E. coli-produced monomeric IL-15. In part because of its larger size and glycosylation, the heterodimeric IL-15 has a much longer T½ of survival in the plasma than does monomeric IL-15 [89].

To address the issue of deficient IL-15R α when IL-15 is used as a monomer, multiple agents involving IL-15 associated with IL-15R α have been generated [70,89–92]. When tested in vitro IL-15R α IgG1-Fc strongly increased the IL-15-mediated proliferation of murine NK and CD8+CD44hi CD8 T cells [65,88,89]. IL-15R α/IL-15 heterodimers administered at tolerable doses to rhesus macaques led to a marked proliferation of NK, γ/δ and CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood. Furthermore, IL-15 heterodimers induced the preferential expansion of both central and effector memory CD8 T cells. In addition, when mice bearing the NK sensitive syngeneic tumor B16 were treated the presence of IL-15R α linked to IgG1Fc but not IgG4Fc there was an increase in the antitumor activity [65]. Thus, a preassociation of IL-15 with IL-15R α enhanced the activities of IL-15 in vivo and in vitro.

Clinical trials with heterodimeric IL-15/IL-15R α agents

As noted above, even if rhIL-15 has clinical efficacy, eventual use of monomeric IL-15 as a single agent is unlikely. Of critical importance in the present IL-15 monomer clinical trials is that there was only a very low level expression of IL-15R α on resting DCs in the serum of patients entering the IL-15 trials with a mean serum level below 2 pg/ml [87]. A number of strategies and agents are being used to circumvent this limitation. One future strategy, noted below, is to combine the optimal rhIL-15 regimen with an agonistic anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody that acts to stimulate IL-15R α expression [66]. In addition, clinical trials have been or are being initiated to evaluate IL-15 preassociated with IL-15R α or with IL-15R α IgG1-Fc [90]. Altor BioScience Corporation launched a clinical trial in patients with metastatic melanoma with the superagonist ALT-803 which represents a combination of a mutant IL-15 with a fourfold increase in biological activity given in conjunction intravenously with IL-15R α-IgG1-Fc [90]. ALT-803 is a superagonist of IL-15 consisting of two molecules of IL-15 N-to-D substituted at position 72 bound to two molecules of the ‘sushi’ domain of IL-15 receptor α and a single Fc fragment of IgG1. The Cancer Immunotherapy Trials Network has initiated a Phase I expansion trial of weekly intravenous ALT-803 in patients with advanced melanoma. Furthermore, Admune Therapeutics LLC in conjunction with the NCI is initiating a clinical trial of subcutaneously administered IL-15 associated with IL-15R α in patients with metastatic malignancy.

The agents with a combination of IL-15R α with IL-15 present a number of theoretical advantages over monomeric rhIL-15. IL-15R α/IL-15 is more physiological in that these elements are always expressed together normally and may indeed represent two elements of a heterodimeric cytokine [88–95]. In addition, the combination can be very efficiently generated in mammalian cells and are glycosylated, whereas this cannot be efficiently done with monomeric IL-15. Due to the larger size and glycosylation, the combination of IL-15R α/IL-15 has a much longer in vivo survival than the 1 h T½ of E. coli-produced IL-15 [89]. Heterodimeric IL-15 can be given two- to three-times a week rather than the daily administration required for monomeric IL-15. The heterodimeric IL-15R μ/IL-15 is 10-fold more active in inducing the expression of NK and CD8 cells than is monomeric IL-15 [89,92]. Finally, in the B16 melanoma and TRAMP-C2 models the heterodimeric IL-15 has shown greater efficacy in the treatment of murine xenograft tumor models than monomeric IL-15 [65].

Expert commentary

IL-15 was shown to have favorable characteristics that make it more effective and less toxic than IL-2 in the treatment of cancer. Furthermore, IL-15 is pivotal in the generation and maintenance of NK cells and is effective in supporting the survival of stem, central and effector CD8 memory T cells. In addition, in contrast to IL-2, IL-15 inhibited IL-2-mediated AICD, less consistently activated Tregs and did not cause a major capillary leak syndrome in mice and in nonhuman primates. Administration of IL-15 to rhesus macaques by CIV at 20 μg/day for 10 days led to an approximately 10-fold increase in the number of circulating NK cells and an 80- to 100-fold increase in the number of circulating effector memory CD8 T cells [75]. Clinical trials utilizing E. coli-produced rhIL-15 are in a Phase I dose finding stage and are directed toward determining an appropriate dosing strategy and the maximum tolerated dose. Nevertheless, it is clear that a number of additional developments including the initiation of combination drug therapy will be required before the encouraging preclinical trials can be translated into an effective strategy utilizing IL-15 in the treatment of patients with cancer. The initial completed Phase I IL-15 bolus infusion clinical trial was associated with toxicities including fever, rigors and hypotension not predicted from the preclinical trials in nonhuman primates. These toxicities as well as hepatotoxicity led to the determination of a maximum tolerated dose of 0.3 μg/kg/day, a value much lower than that predicted from the nonhuman primate studies [79]. The toxicities observed were associated contemporaneously with up to 50-fold increases in IL-6 and IFN-γ levels. There were exceedingly high IL-15 Cmax levels initially following bolus infusions that may underlie this intense cytokine secretion and macrophage activation syndrome that were observed in the first few hours following IL–15 infusions. With the goal of reducing the Cmax, clinical trials have been initiated with alternative dosing strategies by administering IL-15 daily subcutaneously on days 1–5 and 8–12 or by CIV for 10 days. It is hoped that these approaches will reduce toxicity and increase the efficacy of IL-15 in increasing the number of circulating monocytes, NK cells and CD8 effector memory T cells, thereby augmenting efficacy.

Although IL-15 administration may show efficacy, it probably is not optimal when used as a single monomeric agent for cancer therapy. There is only a low level expression of IL-15R α on resting DC cells. As noted for its long-term persistence and its optimal activation of NK and CD8 T cells, IL-15 must be expressed as a heterodimer in association with IL-15R α. To address this challenge, agents with IL-15 preassociated with both IL-15R α and IL-15R α IgG1-Fc have been generated. These combinations have improved pharmacokinetics, have an impact on the mononuclear cell numbers and have greater efficacy in preclinical murine models when compared to monomeric IL-15. Trials have been initiated with both the superagonist ALT-803 (IL-15 and IL-15R α IgG1-Fc) and with IL-15/IL-15R α. It is too early in these studies to define the toxicity and efficacy that will be observed with this approach. Nevertheless, it is my view that neither IL-15 alone nor IL-15 in conjunction with IL-15R α when given alone will show major efficacy in the treatment of cancer. Preclinical studies suggest that the coadministration of IL-15 with other agents, described more extensively in the 5-year view below, will permit IL-15 to play a major role in cancer therapy. In particular, it was shown in murine models using an agonistic anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody coadministered with IL-15 that the combination was associated with an augmented IL-15R α expression and a reversal of the ‘helpless state’ of CD8 cells. This combination showed great additivity/synergy in murine syngeneic tumor models [66]. Furthermore, additivity/synergy was also observed with IL-15 given in combination with both of the checkpoint inhibitors anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-L1 [67]. All the strategies discussed above are based on the assumption that the host is making an immune response, albeit inadequate, to its tumor. Other approaches using IL-15 do not make this assumption. In particular, IL-15 is being incorporated in vaccines [96]. Furthermore, IL-15 is very effective in activating NK cells and monocytes suggesting that it may increase antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity mediated by antineoplastic monoclonal antibodies [97–99].

In summary, it is clear that much work is necessary in the clinic to bring the encouraging preclinical insights and therapeutic opportunities of IL-15 to fruition. It is anticipated that with these combination agent approaches, IL-15 can play a crucial role in the treatment of cancer.

Five-year view

Dose-escalation trials of rhIL-15 with different dosing routes of administration (bolus intravenous infusion, subcutaneous or CIV) will soon be completed. However, monotherapy with IL-15 is not optimal since the physiological agent is the heterodimer IL-15R α/IL-15. Dose-escalation clinical trials will also soon be initiated and completed with the heterodimeric IL-15R α/IL-15 and with mutant IL-15/IL-15R α IgFc. When these studies have been completed, the optimal agent, dose and dosing strategy can be identified. IL-15 alone or coupled with IL-15R α can then be evaluated in a number of clinical situations including as critical elements of antitumor vaccines, cellular therapy and in association with monoclonal antibodies to augment ADCC.

Use of an agonistic anti-CD40 coadministered with IL-15 to induce (IL-15R α) & to reverse the ‘helpless state’ of CD8 T cells

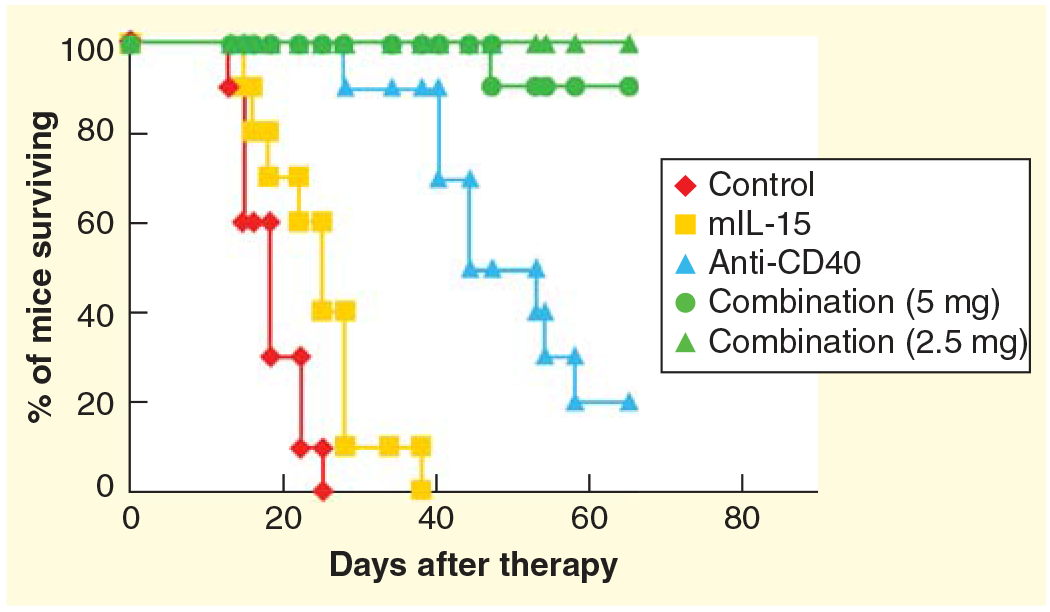

Agents are available that induce IL-15R α expression on DCs that could be given in conjunction with IL-15 to circumvent the problems discussed above with IL-15 when used in monotherapy [66]. Although INF-γ induced IL-15R α on DCs it also induced Class 1 MHC expression on tumor cells and was ineffective when given in conjunction with IL-15 in CT26, MC38 and TRAMP-C2 murine tumor models [66]. In contrast, the combination of IL-15 with the agonistic anti-CD40 antibody FGK4.5 showed additivity/synergy in the MC38 murine model of colon cancer and in the TRAMP-C2 model of prostatic cancer (Figure 2) [66]. The administration of the anti-CD40 antibody was associated with an increased expression of IL-15R α on CD11+DCs expressing cells present in the spleens of treated mice [66]. Furthermore, the serum concentrations of murine IL-15R α as assessed by ELISA were markedly increased in anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody treated mice when compared to those in the control mouse group. In the murine syngeneic tumor model, treatment with IL-15 or with the agonistic anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody alone significantly (p < 0.01) prolonged the survival of both groups of CT26 and MC38 tumor-bearing mice when compared to mice in the PBS control group. These studies were extended to mice bearing established (80 mm3) subcutaneous TRAMP-C2 tumors and again it was demonstrated that the combination of IL-15 with anti-CD40 produced markedly additive effects when compared to either agent administered alone [66]. Using IL-15R α−/− mice or DCs from such IL-15R α depleted mice, the IL-15-mediated induction of IL-15R α was shown to be one of the critical factors in the anti-CD40-mediated augmentation of IL-15 action in the treatment of the TRAMP-C2 model of prostatic cancer [66].

Figure 2. Combination therapy of mIL-15 with agonistic anti-CD40 mAb led to regression of established TRAMP-C2 tumors in wild-type C57BL/6 mice.

Therapy was initiated after tumors were well established with an average volume of 80 mm3. Treatment with mIL-15 alone at a dose of 2.5 μg per mouse 5 days a week for 2 weeks inhibited tumor growth slightly and prolonged survival of TRAMP-C2 tumor-bearing mice compared with mice in the PBS control group (p < 0.05), whereas treatment with an agonistic anti-CD40 mAb (200 μg per mouse on day 0 and then 100 μg per mouse on days 3, 7 and 10) provided greater inhibition of tumor growth and prolonged survival of the TRAMP-C2-bearing mice compared with mice in the PBS control group (p < 0.001). Furthermore, combination therapy with mIL-15 and anti-CD40 provided a greater therapeutic efficacy as demonstrated by the fact that all of the mice in the combination group were alive at day 60, with 80% becoming tumor free, whereas only 20% of the mice in the anti-CD40 mAb alone group and none of the mice in the PBS group or the IL-15 alone group were alive at that time.

mAb: Monoclonal antibody.

Reproduced with permission from [60]. © The American Association of Immunologists Inc. (2012).

Sckisel and coworkers [98] reported that the administration of the γc family cytokine IL-2 induced the expression of SOCS-3 in CD4 T cells that became ineffective as helper cells [98]. Although IL-2 facilitated an increase in the number of CD8 T cells, these CD8 cells induced were ‘helpless’, and inadequate as antigen-specific immune responders [98]. Furthermore, this group indicated that the ligation of CD40 relieved the ‘helpless’ CD8 T cell state so that the CD8 cells became antigen-specific immune responders. Zhang and coworkers reported related results with IL-15 [60]. As noted above, there was additivity/synergy observed with the combination of IL-15 administered with the anti-CD40 antibody FGK4.5 in an established TRAMP-C2 syngeneic tumor model [60]. Furthermore, when evaluated neither the IL-15 alone nor anti-CD40 alone increased the number of tumor-specific tetramer-positive CD8 T cells. However, the administration of the combination of IL-15 plus the agonistic anti-CD40 antibody was associated with a meaningful increase in the number of TRAMP-C2 tumor-specific SPAS-1/SNC9-H8 tetramer-positive CD8 T cells [60]. These tetramer-specific CD8 T cells were shown to be associated with protection from tumor development on rechallenge. These observations provide major support for a clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of an agonistic optimized anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody administered in conjunction with IL-15 in the treatment of cancer.

Agents to relieve checkpoints on the immune system to optimize IL-15 action

The studies above were directed toward developing strategies to increase the efficacy of externally administered IL-15 by augmenting the expression of IL-15R α on APCs. Efforts were also directed toward the coadministration of monoclonal antibodies targeting human cells and proteins that act as inhibitory checkpoints on the immune system to augment the action of coadministered IL-15. As is true with virtually all cytokines, IL-15 is associated with the expression of immunological checkpoints. IL-15 induced the inhibitory cytokine IL-10 and the expression of PD1 on CD8 T cells [67]. Furthermore, IL-15 was shown to be critical in the maintenance of CD122+ CD8+ T negative regulatory cells [100,101]. CD8+CD122+ T cells are a heterogeneous population that contains both PD1 nonexpressing memory cells as well as PD1 expressing negative regulatory cells that produce IL-10 and that negatively regulate other T cells [100,101].

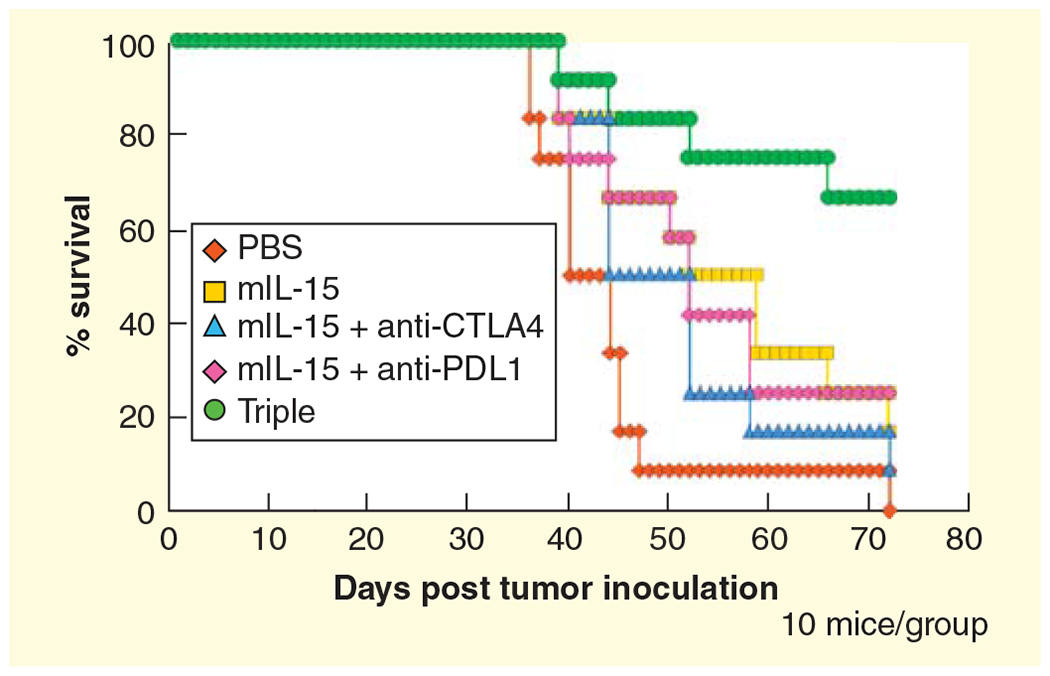

To address the issue of induced checkpoints, IL-15 was administered in combination with agents to remove these inhibitory checkpoints that included antibodies to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and to program death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) proteins that mediate negative T-cell signaling pathways [67,102]. Following intravenous administration of CT26 or MC38 colon carcinoma syngeneic tumors to immunologically intact mice or the establishment of subcutaneous implantation of TRAMP-C2 tumors IL-15 alone provided only a modest antitumor effect (Figure 3). Furthermore, the addition of either anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-L1 alone in association with IL-15 did not augment IL-15 action. However, tumor-bearing mice receiving IL-15 and the combination of both the anti-checkpoints anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-L1 manifested a marked prolongation of animal survival [67,102]. These observations support a clinical trial involving IL-15 or IL-15/IL-15R α with the combination of anti-CTLA-4 with anti-PD1/anti-PD-L1.

Figure 3. IL-15 showed additivity with simultaneous blockade of CTLA-4 and PD-L1 in protecting mice against TRAMP-C2 tumor growth.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrate survivals of mice with treatments. IL-15 (5 mg/day 5 days a week for 2 weeks) plus IgG significantly inhibited tumor growth compared with mice receiving PBS (p = 0.037). The combination of IL-15 with either anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-L1 did not improve animal survival over animals receiving IL-15 alone. However, the triple combination group exhibited a significant survival advantage compared with mIL-15 alone (p = 0.022) or groups receiving mIL-15 plus anti-PD-L1 or anti-CTLA-4 alone treatment (p = 0.042 and p = 0.027, respectively). Moreover, more than 60% of triple-combination treated mice remained tumor free at study termination.

Reproduced with permission from [67].

Use of IL-15 with anticancer monoclonal antibodies to augment ADCC

The predominant approaches involving IL-15 are based on the hypothesis that the host is making an immune response, albeit inadequate, to its tumor that can be augmented by the administration of an IL-15-containing agent. However, IL-15 could also be used in systems where an additional coadministered agent provides the specificity directed toward the tumor. In particular, IL-15 could be used with anticancer vaccines, cellular therapy or with tumor-directed monoclonal antibodies [96,97,99,103]. In particular, given the capacity of IL-15 to increase the number of activated NK cells, monocytes and granulocytes, a very attractive antitumor strategy would be to use the optimal IL-15 agent and dosing strategy with antitumor monoclonal antibodies to augment ADCC cells [96,97,99,103]. Vincent and coworkers reported highly potent anti-CD20-RLI immunocytokine targeting established human B-cell lymphoma in SCID mice. In summary, since IL-15 is effective in activating NK cells, monocytes and granulocytes, trials should be initiated involving IL-15 given with cancer cell directed monoclonal antibodies. It is hoped with the diverse approaches discussed, IL-15 will take a central place in the combination treatment of cancer.

Key issues.

IL-15 is a member of the four α-helix bundle family of cytokines. The IL-15 heterotrimeric receptor includes IL-2/IL-15R β shared with IL-2, γc shared with IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-21 and a private IL-15 receptor, IL-15R α.

As part of an immunological synapse, on the surface of dendritic cells, IL-15R α presents IL-15 in trans to NK and memory CD8 T cells that bear the other two IL-15 receptor subunits.

IL-15 can also function on cells that express the three cell elements of the IL-15 receptor in cis.

IL-15 augments proliferation of T, B and NK cells and induces the expression of stem, central and effector memory CD8 T cells.

IL-15 given by continuous intravenous infusion at 20 μg/kg/day to rhesus macaques was associated with an approximately 10-fold increase in the number of circulating NK cells and an 80- to 100-fold increase in the number of circulating effector memory CD8 T cells.

A clinical trial of daily bolus infusions of recombinant human IL-15 for 12 days has been completed with acceptable toxicity in 18 patients with metastatic malignant melanoma and metastatic renal cell cancer. The maximum tolerated dose in this bolus infusion study was 0.3 μg/kg/day for 12 days.

Phase I dose-escalation clinical trials with different dosing strategies that involve either subcutaneous or with continuous intravenous infusion of IL-15 have been initiated.

Clinical trials are being initiated with IL-15 + IL-15R α or IL-15 + IL-15R α IgFc.

Future trials are planned combining IL-15 with an agonistic anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody given to induce IL-15R α and to reverse the ‘helpless’ state of CD8 T cells.

Subsequent trials will involve IL-15 or IL-15/IL-15R α administered in association with anticancer monoclonal antibodies to augment antibody-dependent cellular toxicity.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH. The author has no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Couzin-Frankel J Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science 2013;342:1432–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maus MV, Grupp SA, Porter DL, June CH. Antibody-modified T cells: CARS take the front seat for hematologic malignancies. Blood 2014;123:2625–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Feldman SA, et al. B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood 2012;119:2709–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldmann TA, Morris JC. Development of antibodies and chimeric molecules for cancer immunotherapy. Adv Immunol 2006;90:83–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDemott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363:711–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2443–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Topalian SL, et al. Treatment of 283 consecutive patients with metastatic melanoma or renal cell cancer using high-dose bolus interleukin-2. JAMA 1994;271:907–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lenardo MJ. Fas and the art of lymphocyte maintenance. J Exp Med 1996;183:721–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Fueling regulation: IL-2 keeps CD4+ Treg cells fit. Nat Immunol 2005;6:1071–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldmann TA. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol 2006;6:595–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fehniger TA, Cooper MA, Caligiuri MA. Interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: immunotherapy for cancer. Cytokine and Growth Factor Rev 2002;13:169–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.•.Mishra A, Sullivan L, Caligiuri MA. Molecular pathways: interleukin-15 signaling in health and in cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:2044–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides an excellent review of the role of IL-15 in cancer.

- 13.Steel JC, Waldmann TA, Morris JC. Interleukin-15 biology and its therapeutic implications in cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2012;33:35–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klebanoff CA, Finkelstein SE, Surman DR, et al. IL-15 enhances the in vivo antitumor activity of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:1969–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldmann TA, Dubois S, Tagaya Y. Contrasting roles of IL-2 and IL-15 in the life and death of lymphocytes: implications for immunotherapy. Immunity 2001;14: 105–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armitage RJ, Macduff BM, Eisenman J, et al. IL-15 has stimulatory activity for the induction of B cell proliferation and differentiation. J Immunol 1995;154:483–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mrozek E, Anderson P, Caligiuri MA. Role of interleukin-15 in the development of human CD56+ natural killer cells from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood 1996;87:2632–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Sun S, Hwang I, et al. Potent and selective stimulation of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells in vivo by IL-15. Immunity 1998;8:591–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lugli E, Dominguez MH, Gattinoni L, et al. Superior T memory stem cell persistence supports long-lived T cell memory. J Clin Invest 2013;123:594–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marks-Konczalik J, Dubois S, Losi JM, et al. IL-2-induced activation-induced cell death is inhibited in IL-15 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:11445–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.•.Grabstein KH, Eisenman J, Shanebeck K, et al. Cloning of a T cell growth factor that interacts with the beta chain of the interleukin-2 receptor. Science 1994;264: 965–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study describes the codiscovery of IL-15.

- 22.Bamford RN, Grant AJ, Burton JD, et al. The interleukin (IL)2 receptor beta chain is shared by IL-2 and a cytokine, provisionally designated IL-T, that stimulates T-cell proliferation and the induction of lymphokine-activated killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:4940–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.•.Burton JD, Bamford RN, Peters C, et al. A lymphokine, provisionally designated interleukin T and produced by a human adult T-cell leukemia line, stimulates T-cell proliferation and the induction of lymphokine-activated killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:4935–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study describes the codiscovery of IL-15.

- 24.Tagaya Y, Kurys G, Thies TA, et al. Generation of secretable and nonsecretable interleukin-15 isoforms through alternate usage of signal peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997;94:14444–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bamford RN, Battiata AP, Burton JD, et al. Interleukin (IL)15/IL-T production by the adult T-cell leukemia cell line HuT-102 is associated with a human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type I R region/IL-15 fusion message that lacks many upstream AUGs that normally attenuate IL-15 mRNA translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:2897–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bamford RN, DeFilippis AP, Azimi N. The 5’untranslated region, signal peptide, and the coding sequence of the carboxyl terminus of IL-15 participate in its multifaceted translational control. J Immunol 1998;160:4418–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waldmann TA, Tagaya Y. Cytokine reference. Volume I Academic Press; London: 2000. p. 213–24 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson DM, Kumaki S, Ahdieh M, et al. Functional characterization of the human interleukin-15 receptor alpha chain and close linkage of IL-15RA and IL-2RA genes. J Biol Chem 1995;270:29862–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucas M, Schachterle W, Oberle K, et al. Dendritic cells prime natural killer cells by trans-presenting interleukin 15. Immunity 2007;26:503–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McInnes IB, Leung BP, Sturrock RD, et al. Interleukin-15 mediates T cell-dependent regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Med 1997;3:189–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mueller JR, Waldmann TA, Kruhlak MJ, et al. Paracrine and transpresentation functions of IL-15 are mediated by diverse splice versions of IL-15R alpha in human monocytes and dendritic cells. J Biol Chem 2012;287:40328–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubois S, Magrangeas F, Lehours P, et al. Natural splicing of exon 2 of human interleukin-15 receptor alpha-chain mRNA results in a shortened form with a distinct pattern of expression. J Biol Chem 1999;274:26978–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giri JG, Kumaki S, Ahdieh M, et al. Identification and cloning of a novel IL-15 binding protein that is structurally related to the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor. Embo J 1995;14:3654–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnston JA, Bacon CM, Finbloom DS, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of STAT5, STAT3, and Janus kinases by interleukins 2 and 15. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:8705–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carson WE, Giri JG, Lindemann MJ, et al. Interleukin (IL) 15 is a novel cytokine that activates human natural killer cells via components of the IL-2 receptor. J Exp Med 1994;180:1395–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadlack B, Kuhn R, Schorle H, et al. Development and proliferation of lymphocytes in mice deficient for both interleukins-2 and-4. Eur J Immunol 1994;24:281–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kennedy MK, Glaccum M, Brown SN, et al. Reversible defects in natural killer and memory CD8 T cell lineages in interleukin 15-deficient mice. J Exp Med 2000;191: 771–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lebrec H, Horner MJ, Gorski KS, et al. Homeostasis of human NK cells is not IL-15 dependent. J Immunol 2013;191: 5551–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellery JM, Nicholls PJ. Alternate signalling pathways from the interleukin-2 receptor. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2002;13: 27–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adunyah SE, Wheeler BJ, Cooper RS. Evidence for the involvement of LCK and MAP kinase (ERK-1) in the signal transduction mechanism of interleukin-15. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997;232: 754–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelletier M, Ratthe C, Girard D. Mechanisms involved in interleukin-15-induced suppression of human neutrophil apoptosis: role of the anti-apoptotic Mcl-1 protein and several kinases including Janus kinase-2, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinases-1/2. FEBS Lett 2002;532:164–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sathe P, Delconte RB, Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F, et al. Innate immunodeficiency following gentic ablation of MCl1 in natural killer cells. Nat Commun 2014;5:4539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.••.Dubois S, Mariner J, Waldmann TA, et al. IL-15Ralpha recycles and presents IL-15 In trans to neighboring cells. Immunity 2002;17:537–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This was the first study to show that IL-15 bound to IL-15R α recycles through endosomal vesicles and that IL-15R α on the surface of monocytes and dendritic cells presents IL-15 in trans to NK cells and CD8+ CD44hi memory T cells.

- 44.Ma A, Koka R, Burkett P. Diverse functions of IL-2, IL-15 and IL-7 in lymphoid homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol 2006;24:657–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sandau MM, Schluns KS, Lefrancois L, Jameson SC. Cutting edge: transpresentation of IL-15 by bone marrow-derived cells necessitates expression of IL-15 and IL-15R alpha by the same cells. J Immunol 2004;173:6537–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schluns KS, Klonowski KD, Lefrancois L. Transregulation of memory CD8 T-cell proliferation by IL-15Ralpha+ bone marrow-derived cells. Blood 2004;103: 988–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mortier E, Woo T, Advincula R, et al. IL-15R alpha chaperones IL-15 to stable dendritic cell membrane complexes that activate NK cells via trans presentation. J Exp Med 2008;205:1213–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chirifu M, Hayashi C, Nakamura T, et al. Crystal structure of the IL-15-IL-15R alpha complex, a cytoine-receptor unit presented in trans. Nat Immunol 2007;8:1001–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marcais A, Cherfils-Vicini J, Viant C, et al. The metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR is essential for IL-15 signaling during the development and activation of NK cells. Nat Immunol 2014;15:749–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olsen SK, Ota N, Kishishita S, et al. Crystal structure of the interleukin-15. interleukin-15 receptor alpha complex: insights into tarns and cis presentation. J Biol chem 2007;282:37191–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rowley J, Monie A, Hung C-F, Wu TC. Expression of IL-15RA or an IL-15/IL-15RA fusion on CD8+ T cells modifies adoptively transferred T-cell function in cis. Eur J Immunol 2009;39:491–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waldmann TA, Conlon KC, Stewart DM, et al. Phase 1 trial of IL-15 trans presentation blockade using humanized Mik-Beta-1 mAb in patients with T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2013;121:476–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oh S, Perera LP, Burke DS, et al. IL-15/IL-15R alpha-mediated avidity maturation of memory CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:15154–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ota N, Takase M, Uchiyama H, et al. No requirement of trans presentations of IL-15 for human CD8 T cell proliferation. J Immunol 2010;185:6041–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zanoni I, Spreafico R, Bodio C, et al. IL-15 cis presentation is required for optimal NK cell activation in lipopolysaccharide-mediated inflammatory conditions. Cell Rep 2013;4:1235–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chenoweth MJ, Mian MF, Barra NG, et al. IL-15 can signal via IL-15R alpha, JNK, and NF-kB to drive RANTES production by myeloid cells. J Immunol 2012;188: 4149–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tagaya Y, Burton JD, Miyamoto Y, Waldmann TA. Identification of a novel receptor signal transduction pathway for IL-15/T in mast cells. Embo 1996;15:4928–39 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pereno R, Giron-Michel J, Gaggero A, et al. IL-15/IL-15R alpha intracellular trafficking in human melanoma cells and signal transduction through the IL-15R alpha. Oncogene 2000;19:5153–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bulfone-Paus S, Bulanova E, Budagian V, Paus R. The interleukin-15/interleukin-15 receptor system as a model for juxtacrine and reverse signaling. Bioessays 2006;28: 362–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.••.Zhang M, Ju W, Yao Z, et al. Augmented interleukin(IL)-15Ralpha expression by CD40 activation is critical in synergistic CD8 T-cell mediated antitumor activity of anti-CD40 antibody with IL-15 in TRAMP-C2 tumors in mice. J Immunol 2012;188:6156–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrated that anti-CD40 showed synergy when coadministered with IL-15 and that the combination induced IL-15R α expression and reversed the ‘helpless’ state of CD8 T cells.

- 61.Kobayashi H, Dubois S, Sato N, et al. Role of trans-cellular IL-15 transpresentation in the activation of NK cell-mediated killing, which leads to enhanced tumor immunosurveillance. Blood 2005;105:721–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Munger W, DeJoy SQ, Jeyaseelan R Sr, et al. Studies evaluating the antitumor activity and toxicity of interleukin-15, a new T cell growth factor: comparison with interleukin-2. Cell Immunol 1995;165: 289–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evans R, Fuller JA, Christianson G, et al. IL-15 mediates anti-tumor effects after cyclophosphamide injection of tumor-bearing mice and enhances adoptive immunotherapy: the potential role of NK cell subpopulations. Cell Immunol 1997;179:66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeng R, Spolski R, Finkelstein SE, et al. Synergy of IL-21 and IL-15 in regulating CD8+ T cell expansion and function. J Exp Med 2005;201:139–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dubois S, Patel HJ, Zhang M, et al. Preassociation of IL-15 with IL-15R apha-IgG1-Fc enhances its activity on proliferation of NK and CD8+/CD44high T cells and its antitumor action. J Immunol 2008;180:2099–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang M, Yao Z, Dubois S, et al. Interleukin-15 combined with an anti-CD40 antibody provides enhanced therapeutic efficacy for murine models of colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:7513–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu P, Steel JC, Zhang M, et al. Simultaneous inhibition of two regulatory T-cell subsets enhanced Interleukin-15 in a prostate tumor model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109:6187–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huntington ND, Alves NL, Legrand N, et al. IL-15 transpresentation promotes both human T-cell reconstitution and T-cell-dependent antibody responses in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:6217–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huntington ND, Legrand N, Alves NL, et al. IL-15 trans-presentation promotes human NK cell development and differentiation in vivo. J Exp Med 2009;206:25–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bessard A, Sole V, Bouchaud G, et al. High antitumor activity of RLl, an interleukin-15 (IL-15)-IL-15 receptor alpha fusion protein, in metastatic melanoma and colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2009;8:2736–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.NCI Immunotherapy Agent Workshop; July 12, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mueller YM, Petrovas C, Bojczuk PM, et al. Interleukin-15 increases effector memory CD8+ T cells and NK cells in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Virol 2005;79:4877–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Waldmann TA, Lugli E, Roederer M, et al. Safety (toxicity), pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, and impact on elements of the normal immune system of recombinant human IL-15 in rhesus macaques. Blood 2011;117:4787–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lugli E, Goldman CK, Perera LP. Transient and persistent effects of IL-15 on lymphocyte homeostasis in nonhuman primates. Blood 2010;116:3238–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sneller MC, Kopp WC, Engelke KJ, et al. IL-15 administered by continuous intravenous infusion to rhesus macaques induces massive expansion of the CD8+ T effector memory population in peripheral blood. Blood 2011;118:6845–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Berger C, Berger M, Hackman RC, et al. Safety and immunological effects of IL-15 administration in nonhuman primates. Blood 2009;114:2417–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Verri WACunha TM, Ferreira SH, et al. IL-15 mediates antigen-induced neutrophil migration by triggering IL-18 production. Eur J Immunol 2007;37:3373–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.A Phase I study of intravenous recombinant human IL-15 in adults with refractory metastatic malignant melanoma and metastatic renal cell cancer. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01021059+&Search=Search [Google Scholar]

- 79.••.Conlon KC, Lugli E, Welles HC, et al. Redistribution, hyperproliferation, activation of NK and CD8 T cells and cytokine production during first-in-human clinical trial of rhIL-15 in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study described the first-in-human Phase I clinical trial with 12 daily bolus intravenous infusions of IL-15 in patients with metastatic melanoma and renal cell cancer.

- 80.Grupp SA, Kalos M, Barrett D, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N Eng J Med 2013;368:1509–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Teachey DT, Rheingold SR, Maude SL, et al. Cytokine release syndrome after blinatumomab treatment related to abnormal macrophage activation and ameliorated with cytokine-directed therapy. Blood 2013;121:5154–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Recombinant Interleukin-15 in treating patients with advanced melanoma, kidney cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, or squamous cell head and neck cancer. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01727076+&Search=Search [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morishima C, Sondel PM, Kohrt HEK, et al. CITN11-02 Interim trial results: Subcutaneous administration of recombinant human IL-15 (rhIL-15) is associated with robust expansion of peripheral blood CD56+ NK cells. Abstract for SITC Meeting 2014; In press [Google Scholar]

- 84.Continuous infusion of rhIL-15 for adults with advanced cancer. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01572493&Search=Search [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haploidentical donor natural killer cell infusion with IL-15 in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (AML). Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01385423&Search=Search [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cooley S, Verneris MR, Curtsinger J, et al. Recombinant human IL-15 promotes in vivo expansion of adoptively transferred NK cells in a first-in-human phase I dose escalation study in patients with AML. Blood 2012;120:Meeting abstract 894 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen J, Petrus M, Bamford R, et al. Increased serum soluble IL-15R alpha levels in T-cell large granular lymphocyte leukemia. Blood 2012;119:137–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tinhofer I, Marschitz I, Henn T, et al. Expression of functional interleukin-15 receptor and autocrine production of interleukin-15 as mechanisms of tumor propagation in multiple myeloma. Blood 2000;95:610–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chertova E, Bergamaschi C, Chertov O, et al. Characterization and favorable in vivo properties of heterodimeric soluble IL-15-IL-15R alpha cytokine compared to IL-15 monomer. J Biol Chem 2013;288: 18093–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Altor launches clinical trial of IL-15 superagonist protein complex against metastatic melanoma. Cellular Technology Ltd, 2013. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.pharmaceutical-business-review.com/news/altor-launches-clinicaltrial [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stoklasek TA, Schluns KS, Lefrancois L. Combined IL-15/IL-15Ralpha immunotherapy maximizes IL-15 activity in vivo. J Immunol 2006;177:6072–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rubinstein MP, Kovar M, Purton JF, et al. Converting IL-15 to a superagonist by binding to soluble IL-15R{alpha}. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:9166–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Burkett PR, Koka R, Chien M, et al. Coordinate expression and trans presentation of interleukin (IL)-15Ralpha and IL-15 supports natural killer cell and memory CD8+ T cell homeostasis. J Exp Med 2004;200:825–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sandau MM, Schluns KS, Lefrancois L, Jameson SC. Cutting edge: transpresentation of IL-15 by bone marrow-derived cells necessitates expression of IL-15 and IL-15R by the same cells. J Immunol 2004;173:6537–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bergamaschi C, Bear J, Rosati M, et al. Circulating IL-15 exists as heterodimeric complex with soluble IL-15R alpha in human and mouse serum. Blood 2012;120: e1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Oh S, Berzofsky JA, Burke DS, et al. Coadministration of HIV vaccine vectors with vaccinia viruses expressing IL-15 but not IL-2 induces long-lasting cellular immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:3392–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Roberti MP, Barrio MM, Bravo AI, et al. IL-15 and IL-2 increase Cetuximab-mediated cellular cytotoxicity against triple negative breast cancer cell lines expressing EGFR. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;130:465–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sckisel GD, Bouchlaka MN, Mirsoian A. Cyotkine-based immunotherapy impairs primary T cell immunity (VAC3P.942). Immunology 2014;192:abstract 11024116956 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vincent M, Teppaz G, Lajoie L. Highly potent anti-CD20-RLI immunocytoine targeting established human B lymphoma in SCID mouse. MAbs 2014;4:1026–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee YH, Ishida Y, Rifa’i M, et al. Essential role of CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells in the recovery from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 2008;180: 825–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Endharti AT, Rifa’I M, Shi Z, et al. Cutting edge: CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells produce IL-10 to suppress IFN-g production and proliferation of CD8+ T cells. J Immunol 2005;175:7093–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yu P, Steel JC, Zhang M, et al. Simultaneous blockade of multiple immune system inhibitory checkpoints enhances antitumor activity mediated by interleukin-15 in a murine metastatic colon carcinoma model. Clin Can Res 2010;16: 6019–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Moga E, Alvarez E, Canto E, et al. NK cells stimulated with IL-15 or CpG ODN enhance rituximab-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against B-cell lymphoma. Exp Hematol 2008;36:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Use of IL-15 after chemotherapy and lymphocyte transfer in metastatic melanoma. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01369888&Search=Search [Google Scholar]