TO THE EDITOR

In this issue of the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, Han et al. (2018) have made a landmark contribution to the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in dermatologic diagnosis. Although previous studies have reported that computer algorithms can successfully diagnose skin cancer from medical images with human equivalency (Esteva et al., 2017;Ferris et al., 2015;Marchetti et al., 2018;Menzies et al., 2005), Han et al. have made their computer algorithm publicly available for external testing.

To explore the generalizability of their computer classifier in a unique patient population, we selected 100 sequentially biopsied cutaneous melanomas (n = 37), basal cell carcinomas (n = 40), and squamous cell carcinomas (n = 23) with high-quality clinical images from the International Skin Imaging Collaboration Archive (https://isic-archive.com/#images, dataset name: 2018 JID Editorial Images). We uploaded them to the Han et al. web application (http://dx.medicalphoto.org/) on 7 March 2018. All lesions originated from Caucasian patients in the southern United States.

Overall, the Han et al. algorithm’s first classification (i.e., highest probability output) matched the histopathological diagnosis in 29 of the 100 lesions (29%) (Table 1). Considering any of the up to five classifications rendered per image by the web app algorithm (irrespective of the probability), the concordant or matching diagnosis was included for 58% of lesions (58 of 100). We found no difference in the probability output of the first classification among correctly and incorrectly diagnosed lesions (0.711 vs. 0.715, P = 0.94, paired t-test). Of the melanomas, melanoma was the first classification in 13.5% (5 of 37) lesions with a mean (range) probability score of 0.82 (0.42—0.99);considering any of the up to five classifications, melanoma was included in 35.1% (13 of 37) lesions with a mean (range) probability score of 0.43 (0.02—0.99). Among the eight melanomas with melanoma listed as the second or third classification, the mean (range) probability score was 0.18 (0.02—0.37).

Table 1.

Cross-classification frequencies of histopathological diagnosis and web app leading category (categorization with highest probability), along with the average probability associated with the rendered decision

| Web app categorization |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histopathologic diagnosis | Melanoma | Basal cell carcinoma | Intraepithelial carcinoma | Squamous cell carcinoma | Hemangioma | Lentigo | Actinic keratosis | Nevus | Seborrheic keratosis | Wart | Total |

| Melanoma | 5 0.82 |

2 0.96 |

6 0.70 |

3 0.59 |

1 0.96 |

12 0.82 |

1 0.94 |

5 0.65 |

0 | 2 0.82 |

37 |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 0 |

19 0.68 |

10 0.78 |

1 0.82 |

3 0.83 |

1 0.81 |

1 0.98 |

2 0.74 |

1 0.37 |

2 0.57 |

40 |

| Intraepithelial carcinoma | 0 | 6 0.59 |

4 0.83 |

1 0.51 |

0 | 1 0.52 |

1 0.46 |

0 | 0 | 1 0.85 |

14 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 0.17 |

1 0.46 |

4 0.87 |

1 0.30 |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 0.36 |

9 |

| Total | 6 | 28 | 24 | 6 | 4 | 14 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 100 |

The bold values represent the “correct” diagnosis.

Our results suggest that the sensitivity of the Han et al. algorithm for skin cancer, and particularly melanoma, is considerably lower when applied to a different patient population, limiting its generalizability. Although one may take these results to signify a poor performance of the computer classifier, it is important to consider the inherent limitations and challenges associated with automated skin cancer diagnosis when interpreting these data.

Although the authors collected more than 500,000 images, only approximately 20,000 (approximately 6,000 malignancies) were used in training their algorithm. Notably, these images were not collected in a standardized fashion and were associated with limited clinical metadata. In order for deep learning-based diagnostics to become clinically successful, larger datasets including the full spectrum of human populations and clinical presentations are required to develop and train classifiers. The authors did provide specific data on an Asian population (“Asan” dataset) and a Caucasian population (“Edinburgh” dataset), with differences in algorithm performance between the datasets attributed to variations in clinical presentation of specific tumors, patient ethnicities, and image acquisition settings. Ideally, datasets should also include the minimum metadata that a clinician would use when examining a patient (e.g., age, gender, race, skin type, anatomic location, and temporal [i.e., change] and comparative [i.e., appearance relative to other patient lesions] data of the lesion, etc.). As datasets evolve, it will be critical to identify and minimize potential biases that contribute to algorithm output decisions. Gender and racial dataset biases have been shown to have significant effects on the accuracy of facial recognition algorithms (Lohr, 2018). Indeed, we found ink markings to be more prevalent among malignant than benign lesions (28% vs. 19.3%) in the test dataset of 100 malignant and 160 benign images used by Han et al. in their reader study.

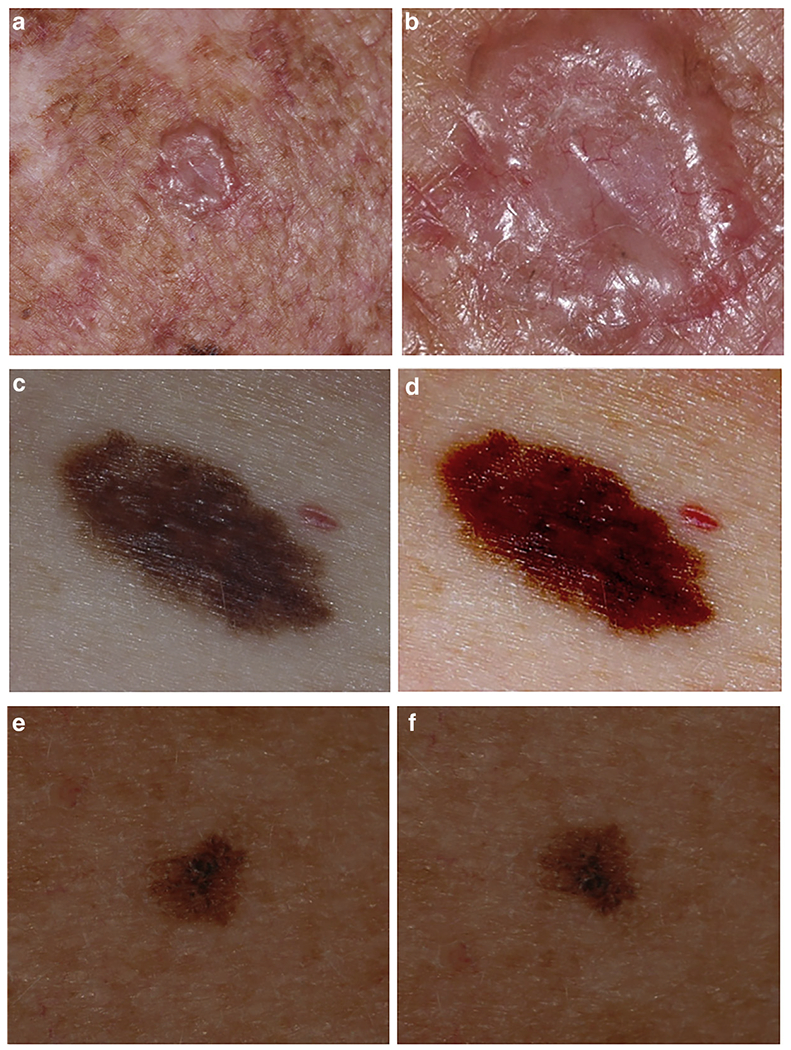

Additional challenges to the generalizability of automated diagnosis include variability in technologies (camera types) and techniques (lighting, body position, etc.) applied to image acquisition. We found significant effects on the classification predictions by the Han et al. algorithm by altering the zoom, contrast/brightness settings, and rotation of images from our dataset (Figure 1). These examples raise important questions regarding the “black box” of AI and underscore previous observations that algorithms are susceptible to image manipulation (e.g., “impersonation” glasses in facial recognition) that does not readily affect human perception (Castelvecchi, 2016; Sharif et al., 2016).

Figure 1. Modification of the web app classification output by image manipulation.

(a, b) Basal cell carcinoma. The original image (a) was modified by zooming in (b). The two images gave different classifications: (a) lentigo (99.2% confidence); (b) intraepithelial carcinoma (96.9% confidence). (c, d) Melanoma. The original image (c) was modified by changing the contrast and brightness settings (d). The two images gave different classifications: (c) melanoma (99% confidence); (d) hemangioma (98% confidence). (e, f) Melanoma. The original image (e) was modified by flipping the image vertically (f). The two images gave different classifications: (e) lentigo (74% confidence), melanoma (12% confidence), nevus (5% confidence); (f) melanoma (40.5% confidence), lentigo (32% confidence), nevus (24% confidence). All images come from the International Skin Imaging Collaboration Archive (https://isic-archive.com/#images, dataset name: 2018 JID Editorial Images).

Although some may perceive the advent of automated diagnosis as a threat, an effective AI system has the potential to improve the accuracy, accessibility, and efficiency of patient care. There are also considerable risks. Premature application of automated diagnosis in clinical practice may not only lead to misdiagnosis, as suggested by our results, but it may also lead to unnecessary concern for lesions of minimal to no risk. Both the opportunities and risks associated with automated diagnosis are magnified if automated diagnostics are directly provided to patients. Finally, even an accurate and valid AI system could lead to substantial harm if used to detect cancer with a low risk of mortality in a population with limited survival through overdiagnosis (Linos et al., 2014).

The successful development of deep learning for dermatologic diagnosis and its effective application in clinical practice can only succeed with the active participation of the dermatology community. The datasets that are required must come from those who are delivering care and can provide the relevant clinical metadata and outcomes. To that end, we support the efforts made by Han et al. to make their image dataset and algorithm publicly accessible. The availability of shared datasets permits independent assessment of the performance of automated diagnostics and is likely to improve the integrity and reproducibility of future research efforts.

Implementation of standards for acquiring images in dermatology has further potential to improve the quality, usability, and generalizability of medical images. To address these issues, the International Skin Imaging Collaboration is creating technology, technique, and terminology standards for skin imaging (https://isic-archive.com). It is also building a public archive of images with an initial focus on skin cancer, particularly melanoma. We hope that these efforts will facilitate the computer science and dermatology communities in the development, benchmarking, and constructive critique of AI approaches to dermatologic diagnosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Abbreviation:

- AI

artificial intelligence

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Castelvecchi D Can we open the black box of AI? Nature 2016;538:20–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, Ko J, Swetter SM, Blau HM, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017;542:115–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris LK, Harkes JA, Gilbert B, Winger DG, Golubets K, Akilov O, et al. Computer-aided classification of melanocytic lesions using dermoscopic images. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;73: 769–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SS, Kim MS, Lim W, Park GH, Park I, Chang SE. Classification of the clinical images for benign and malignant cutaneous tumors using a deep learning algorithm. J Invest Dermatol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linos E, Schroeder SA, Chren MM. Potential overdiagnosis of basal cell carcinoma in older patients with limited life expectancy. JAMA 2014;312:997–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr S Facial Recognition Is Accurate, if You’re a White Guy, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/09/technology/facial-recognition-race-artificial-intelligence.html; 2018. (accessed 6 March 2018).

- Marchetti MA, Codella NCF, Dusza SW, Gutman DA, Helba B, Kalloo A, et al. Results of the 2016 International Skin Imaging Collaboration International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging challenge: comparison of the accuracy of computer algorithms to dermatologists for the diagnosis of melanoma from dermoscopic images. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78:270–277.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies SW, Bischof L, Talbot H, Gutenev A, Avramidis M, Wong L, et al. The performance of SolarScan: an automated dermoscopy image analysis instrument for the diagnosis of primary melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:1388–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif M, Bhagavatula S, Bauer L, Reiter M. Accessorize to a crime: real and stealthy attacks on state-of-the-art face recognition. CCS ’16 Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security 2016:1528–40. [Google Scholar]