Abstract

Background:

We describe a multidisciplinary approach for comprehensive care of amputees with concurrent targeted muscle reinnervation (TMR) at the time of amputation.

Methods:

Our TMR cohort was compared to a cross-sectional sample of unselected oncologic amputees not treated at our institution (N = 58). Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (NRS, PROMIS) were used to assess postamputation pain.

Results:

Thirty-one patients underwent amputation with concurrent TMR during the study; 27 patients completed pain surveys; 15 had greater than 1 year follow-up (mean follow-up 14.7 months). Neuroma symptoms occurred significantly less frequently and with less intensity among the TMR cohort. Mean differences for PROMIS pain intensity, behavior, and interference for phantom limb pain (PLP) were 5.855 (95%CI 1.159-10.55; P = .015), 5.896 (95%CI 0.492-11.30; P = .033), and 7.435 (95%CI 1.797-13.07; P = .011) respectively, with lower scores for TMR cohort. For residual limb pain, PROMIS pain intensity, behavior, and interference mean differences were 5.477 (95%CI 0.528-10.42; P = .031), 6.195 (95%CI 0.705-11.69; P = .028), and 6.816 (95%CI 1.438-12.2; P = .014), respectively. Fifty-six percent took opioids before amputation compared to 22% at 1 year postoperatively.

Conclusions:

Multidisciplinary care of amputees including concurrent amputation and TMR, multimodal postoperative pain management, amputee-centered rehabilitation, and peer support demonstrates reduced incidence and severity of neuroma and PLP.

Keywords: neuroma, pain management, phantom limb pain, residual limb pain

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Despite a paradigm in the United States that has favored limb salvage and advances in limb salvage techniques, amputation remains a cornerstone in the management of extremity malignancies at time of index resection, for the management of locally recurrent disease, and for failed limb salvage. Approximately 18,000 patients undergo amputation for cancer diagnoses annually, representing a small but significant portion of the amputee population.1 In light of heterogeneous evidence favoring limb salvage over amputation, Robert et al,2 summarized it best when they concluded that regardless of the surgical strategy (limb salvage or amputation), patients with more functional lower limbs had a better quality of life. Therefore, we submit that we must refocus our efforts away from the decision of limb salvage versus amputation and instead strive towards developing techniques and strategies to achieve “limb optimization.”

Several strategies may be considered to increase the odds of a favorable outcome after amputation. Herein we present a multidisciplinary approach for the care of the oncologic amputee with a foundation built upon the surgical innovation of targeted muscle reinnervation (TMR) and synergistic adjuvants including multimodal acute pain management, emphasizing the role of oncologic rehabilitation, and psychosocial support.

1.1 |. Management of postamputation pain through surgical innovation

One reason to avoid amputation has historically been the possibility of intractable postamputation pain. People living with limb loss may experience pain in the form of residual limb pain, phantom limb pain (PLP), and axial musculoskeletal pain.3–5 As few as 9% of all amputees report living pain-free,5 leaving a significant number of amputees living with chronic pain. Symptomatic neuromas are responsible for chronic localized pain within the residual limb in approximately 30% of major limb amputees.6 These neuromas can make prosthetic wear uncomfortable or even impossible. Traditionally, traction neurectomy is performed at the time of amputation; however this results in a neuroma as the transected axons attempt to regenerate.7 Numerous surgical techniques have been proposed8 including excision of the neuroma and burying the nerve in muscle,9 bone,10–12 or vein,13,14 and coaptation of two nerve ends.15,16 To date, no method provides consistently effective relief of neuroma-related postamputation pain. In addition to neuroma-related residual limb pain, up to 85% of all major limb amputees experience PLP.17–23 PLP is defined as burning, tingling, discomfort, or electrical shooting pain in the missing limb.24 Oncology patients experience similar, if not higher, rates of PLP after amputation compared to the general amputee population.25–30 Krane and Heller25 noted PLP in up to 90% of pediatric extremity sarcoma survivors, while others have noted PLP in 60%-87% of proximal oncologic amputees.29,30 Some evidence suggests that chemotherapy may play a potentiating role in the development of PLP.26 While the exact mechanism of PLP and phantom limb sensations are poorly understood, it is surmised that spontaneous and abnormal peripheral nerve signals along with associated central changes including cortical reorganization and gray matter plasticity may play crucial roles.31–35 Proposed strategies for the management of PLP include peri-operative catheters, pharmacological therapies, cognitive and mirror therapy, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.36–45 Although these modalities have demonstrated some benefit, no intervention has been shown to clearly prevent or treat PLP.

TMR has recently been adopted as a strategy for the management and prevention of postamputation pain. TMR was originally performed by Dumanian as a secondary procedure to improve myoelectric prosthetic control in proximal upper extremity amputees.46 It involves the transfer of transected peripheral nerves to otherwise redundant target muscle motor nerve units.46–53 The central principle underlying nerve transfers in TMR surgery is to reestablish a physiologic end organ for the transected nerve through the organized reinnervation of denervated target muscle units. Details of the surgical technique have been previously published.54–56 Nerve coaptation provides the nerve with a function as it heals, thus increasing the likelihood that neuromas do not form and that subsequent neuroma related symptoms are minimized. This clinical effect has been observed in animal models that demonstrate normalization of nerve morphology after neuroma excision and subsequent TMR.57 In a study focusing on the effect of TMR on postamputation neuroma pain, Souza et al58 demonstrated successful treatment of neuroma-related symptoms in 93% of patients who had neuroma-related pain before TMR. A recent randomized control trial for the treatment of established residual limb and neuroma pain in amputees with TMR versus neuroma excision and muscle burying showed improved PLP with TMR.59 Furthermore, Serino et al60 objectively demonstrated the beneficial effect of targeted muscle and sensory reinnervation on the normalization of motor and sensory cortical organization and the prevention of cortical reorganization that occurs after amputation, confirming similar findings by Chen et al61 The potential for this strategy in the oncology population was recently highlighted.62

With the recognition that chronic pain is difficult to treat, we have instituted TMR at the time of major limb amputation as routine practice at our institution, in particular for oncologic amputees, for the preemptive management of postamputation pain.

1.2 |. Management of postamputation pain through multimodal pharmacology

With few historical options for neuroma-related residual limb and PLP, opioid analgesics remain a central component of postamputation pain management.43,63 The short-term effects of various interventions on inpatient opioid consumption are a frequently reported outcome in the literature42,64–66; however, the reporting of chronic opioid dependence after amputation is inconsistent. Although recent literature supports its use in the treatment of PLP in a subset of patients who appear to be opioid-responders,37,67 awareness of the growing opioid epidemic and resultant legislative changes discourage and limit the use of opioids for the management of chronic pain, thus necessitating the development of alternative strategies to prevent phantom limb and neuroma-related residual limb pain.

Neuromodulators, such as gabapentin and pregabalin, are commonly utilized in the management of neuropathic pain, including postamputation PLP. Literature supporting the use of neuromodulators in the prevention and treatment of PLP is inconclusive. Given its associated side effects, it is uncertain if the risk-benefit favors its long-term daily use.36,43,68,69

The effect of TMR on the use of postoperative narcotic dependence is investigated in our patient population.

1.3 |. Oncology rehabilitation: optimizing the benefit of TMR

Oncology rehabilitation teams consisting of physical and occupational therapists have an essential role in the integrative care model of cancer patients. Research has shown that oncology-specific rehabilitation decreases disability and overall health care costs when utilized throughout the cancer treatment continuum.70,71 A study from the Journal of the National Cancer Institute projects there will be 18.1 million cancer survivors in the United States in 2020 with a total cost of $173 billion, representing a 39% increase from the year 2010.72 With this increase, due in large part to more effective treatment measures, the health care system is met with the challenge of survivorship care. Thus it is crucial to minimize the functional impairment and disability experienced by patients during and after treatment and facilitate patients’ reintegration into society.73 Furthermore, oncologic amputees have comorbidities that may affect or slow down their postoperative rehabilitation course, including chemotherapy-related fatigue and neuropathy that can cause increased pain and decreased strength and endurance.74 Similarly, radiation-associated fibrosis can slow down the rehabilitation process and limit prosthetic utilization.75 Addressing these hurdles requires a coordinated team of physical and occupational therapists dedicated solely to the care of oncology patients who are aware of the unique needs and burdens of this population.

In addition to their oncology-specific needs, patients undergoing amputation with TMR have tailored rehabilitation that evolves as the nerve coaptations heal. Our institutional rehabilitation protocol is available in Appendix 1. Throughout the recovery process our therapist continues to assess functional outcomes at 2-month intervals until patients achieve their functional goals and then ideally annually thereafter.

Our collaborative multidisciplinary team is essential to create continuity of care and effectively manage the patient’s rehabilitation needs throughout their recovery.

1.4 |. Peer support

The emotional and physical strain endured by an oncology patient necessitates a supportive cast of caregivers, family, friends, healthcare providers, and peers. Furthermore, a strong peer support network for major limb amputees is known to be associated with improved outcomes.76,77 In the cancer population, this sense of community from a peer support network is associated with improved quality of life for many participants.78 The plight of the oncologic amputee is truly unique with patients battling a cancer diagnosis during ongoing treatment, as well as the pain, change in body image, and loss of function associated with a major limb amputation. Therefore, our patients are offered the opportunity to speak with TMR amputees preoperatively, and at follow-up appointments are encouraged to seek out support groups.

2 |. METHODS

Patients during the sample period followed our institutional protocol as described in detail in Appendix 2. Following Institutional Review Board approval, patient-reported outcomes were collected using a previously developed amputee survey for patients who underwent major limb amputation with concurrent TMR for an oncologic diagnosis between November 2015 and November 2018. Opioid prescription patterns were examined using the Ohio Automated Rx Reporting System (OARRS). Patients were excluded if they were under 18 years of age at the time of follow-up, had a cognitive impairment, were enrolled in other studies relating to neuropathic pain, had open wounds, or were actively undergoing radiation therapy. Minimum follow-up time was 3 months. The TMR cohort was compared to a cross-sectional sample of unselected amputees not treated at our institution recruited from across the United States via prosthetic clinics, pain clinics, amputee clinics, and activity clubs, as well as amputee conferences and trade shows. The survey was also advertised online at amputee-coalition.org. The result of this effort was 727 completed surveys, of which 60 identified “Cancer” as the reason for amputation. Two were excluded for age <18 years for a final control group N = 58.

The survey collected demographic information (age, gender, education, employment) and amputation information (level of amputation, time since amputation, and reason for amputation). Participants were asked to rate the frequency and intensity of neuroma symptoms, including tingling sensations, burning sensations, sudden episodes of pain, light touch causing pain, hot or cold temperatures causing pain, and light pressure causing pain. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) instruments for pain intensity (short form 3a), pain behavior (short form 7a), and pain interference (short form 8a) were used to assess residual limb and PLP separately.79–82 Pain outcomes were analyzed only for patients with greater than 1 year follow-up. TMR patients with greater than 1 year follow-up (N = 15) were compared to TMR patients with less than 1 year follow-up (N = 12) in a secondary analysis.

Categorical variables were analyzed by the Chi-squared statistic. Ordinal variables were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test. PROMIS scores were analyzed by independent samples t test comparison of means. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY).

3 |. RESULTS

During the study period, 31 patients with malignant or benign aggressive tumor diagnoses were treated at our institution with amputation and concurrent TMR. Four patients were excluded from patient-reported outcomes analysis according to our exclusion criteria–two patients with open wounds and two patients with inadequate patient-reported outcomes follow-up. Of those included in the patient-reported outcomes study, the average patient age was 53.5 years (range 18-85 years). Average follow-up time was 14.7 months (range 3-40.2 months). Six upper extremity (3 transhumeral and 3 shoulders disarticulation) and 21 lower extremity amputations were performed (7 below the knee, 13 above knee, and 1 hip disarticulation).

Our cohort of patients undergoing amputation with concurrent TMR included 31 patients with a wide range of histologic diagnoses, including bone and soft-tissue sarcomas as well as other non-sarcoma malignancies and benign aggressive tumors (Table 1). With respect to oncologic follow-up, average follow-up was 16 months with three patients lost to follow-up with no evidence of disease at 0, 5, and 9 months respectively. Nine upper extremity amputations (1 transradial, 4 trans-humeral, and 4 shoulder disarticulations) and 22 lower extremity amputations (7 below the knee, 14 above the knee and 1 hip disarticulation) were performed. Sixteen amputations were performed at the index resection for a malignant diagnosis. Fifteen patients underwent secondary amputation; 13 for local recurrence and two for infection-related failures of distal femoral replacements for a large distal femoral B-cell lymphoma and remote distal femoral chondrosarcoma. Eleven patients received neoadjuvant (within 8 weeks of amputation) chemotherapy, and 12 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy (started before 8 weeks postoperatively) after amputation. Seven patients received radiation to the operative extremity at any time before amputation and two patients received postoperative radiation (within 8 weeks of amputation).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics including age at the time of amputation, gender, oncologic diagnosis, level of amputation, the use of adjuvant therapies, and oncologic outcome at final follow-up

| Level of amputation | Age, y | Gender | Oncologic diagnosis | Adjuvant therapy | Oncologic outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | Postoperative | ||||||||

| Chemotherapy | XRT | Chemotherapy | XRT | ||||||

| 1 | Trans-radial | 49 | M | Synovial sarcoma | – | – | Yes | – | Metastatic/died of disease |

| 2 | BKA | 42 | M | Leiomyosarcoma | Yes | – | – | – | No evidence of disease |

| 3 | Shoulder disarticulation | 58 | M | Recurrent chondroblastic osteosarcoma | – | – | – | – | No evidence of disease |

| 4 | BKA | 32 | M | Clear cell sarcoma | – | – | – | – | Lost to follow-up (NED) |

| 5 | BKA | 18 | M | Ewing sarcoma | Yes | – | Yes | – | No evidence of disease |

| 6 | AKA | 51 | M | Recurrent malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | No evidence of disease |

| 7 | AKA | 62 | M | B-cell lymphoma | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | No evidence of disease |

| 8 | Shoulder disarticulation | 62 | M | Recurrent metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | No evidence of disease |

| 9 | AKA | 45 | M | Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma | – | – | – | – | No evidence of disease |

| 10 | BKA | 69 | F | Synovial cell sarcoma | – | – | – | – | No evidence of disease |

| 11 | AKA | 44 | F | Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma | Yes | – | Yes | – | No evidence of disease |

| 12 | BKA | 51 | M | Clear cell sarcoma | – | – | – | – | No evidence of disease |

| 13 | AKA | 83 | F | Recurrent high-grade myxofibrosarcoma | – | – | – | – | Local recurrence/metastatic disease |

| 14 | Shoulder disarticulation | 54 | M | Osteosarcoma | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Local recurrence/metastatic disease/died of disease |

| 15 | Shoulder disarticulation | 66 | F | Recurrent undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma | – | Yes | – | – | Local recurrence |

| 16 | AKA | 17 | M | Osteosarcoma | – | – | Yes | – | No evidence of disease |

| 17 | AKA | 47 | M | High-grade myxofibrosarcoma | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | No evidence of disease |

| 18 | Trans-humeral | 60 | F | Recurrent epithelioid sarcoma | Yes | – | – | Yes | No evidence of disease |

| 19 | AKA | 26 | M | Recurrent low-grade parosteal osteosarcoma | – | – | – | – | Lost to follow-up (NED) |

| 20 | BKA | 22 | M | Recurrent high-grade osteosarcoma | – | – | Yes | – | No evidence of disease |

| 21 | Trans-humeral | 68 | F | Recurrent high-grade myxofibrosarcoma | – | Yes | – | – | Local recurrence/metastatic disease/died of disease |

| 22 | AKA | 59 | M | Interme intermediate-grade MPNST | – | – | – | – | Lost to follow-up (NED) |

| 23 | AKA | 84 | M | High-grade myxofibrosarcoma | No evidence of disease | ||||

| 24 | AKA | 75 | F | Chondrosarcoma | – | – | – | – | No evidence of disease |

| 25 | AKA | 68 | M | High-grade spindle cell sarcoma of bone | Yes | – | Yes | – | No evidence of disease |

| 26 | Trans-humeral | 78 | M | Recurrent intermediate-grade myxofibrosarcoma | – | – | – | – | No evidence of disease |

| 27 | BKA | 70 | F | Recurrent high-grade myxofibrosarcoma | – | – | – | – | No evidence of disease |

| 28 | AKA | 22 | F | Recurrent desmoid tumor | – | Yes | – | – | No evidence of disease |

| 29 | AKA | 50 | F | Alveolar soft part sarcoma | – | – | – | – | No evidence of disease |

| 30 | Hip disarticulation | 46 | M | Chondroblastic osteosarcoma | Yes | – | Yes | – | No evidence of disease |

| 31 | Trans-humeral | 57 | F | Squamous cell carcinoma | – | – | – | – | No evidence of disease |

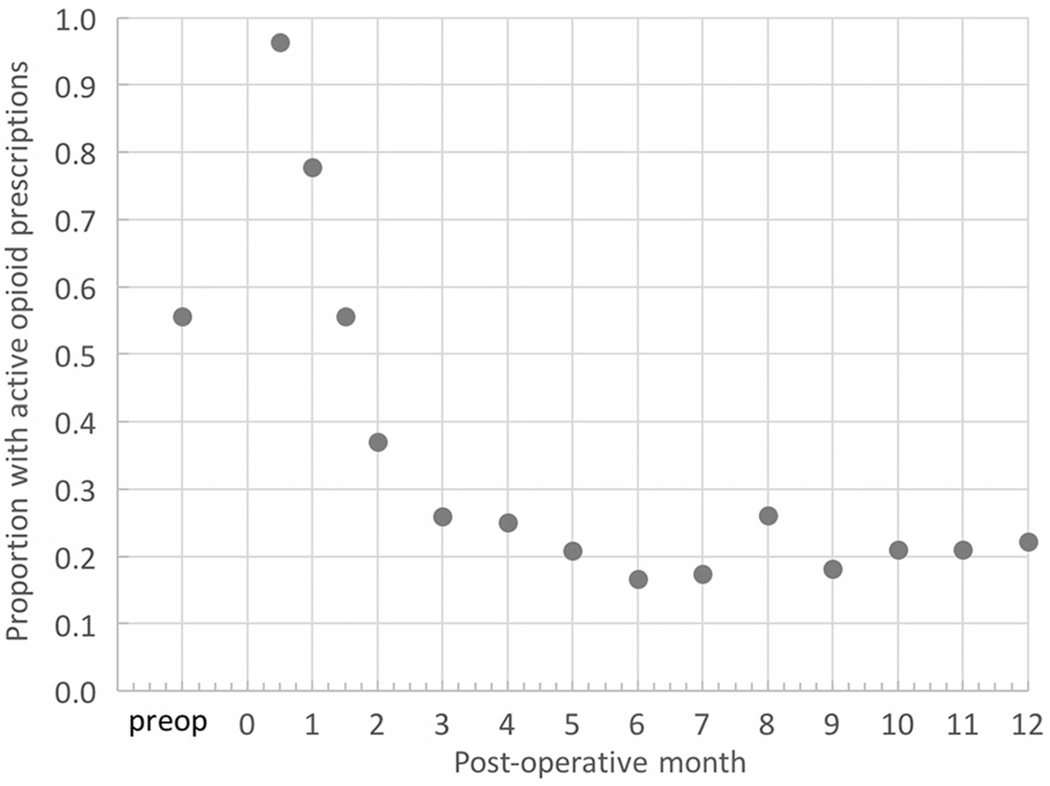

At clinical last follow-up, 23 patients (74%) were without evidence of disease, one patient (3.2%) had an isolated local recurrence, one patient developed metastatic disease without local recurrence and unfortunately died of his disease, and three patients (9.7%) developed a local recurrence with concurrent metastatic disease, two of whom died of their disease. Three patients were lost to clinical follow-up, but at the time of the last follow-up were without evidence of disease. These results are similar to those observed in similar studies of patients undergoing amputation for oncologic reasons with local recurrence occurring in 7%-36% of patients.28–30,83–86 Wound complications requiring a return to the operating room occurred in 16% (5/31) of patients, including one patient who initially underwent a below-knee amputation with TMR who required conversion to an above knee amputation with TMR because of a nonhealing stump wound. Two patients returned to the operating room for neuroma excisions and TMR of symptomatic neuromas that developed in pure sensory nerves (medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve) that were not included in the initial nerve transfer. Nineteen (61.3%) patients were fitted with and received their prosthesis on average 3.6 months postoperatively (range 2-7 months). Fifteen of 27 patients (56%) were taking opioids before amputation. At 6 weeks, 56% continued to require opioid prescriptions; this percentage decreased to 26% by 3 months and plateaued to 22% by 1 year (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Opioid prescriptions for TMR-treated oncologic amputees. Time zero represents the day of amputation and TMR. TMR, targeted muscle reinnervation

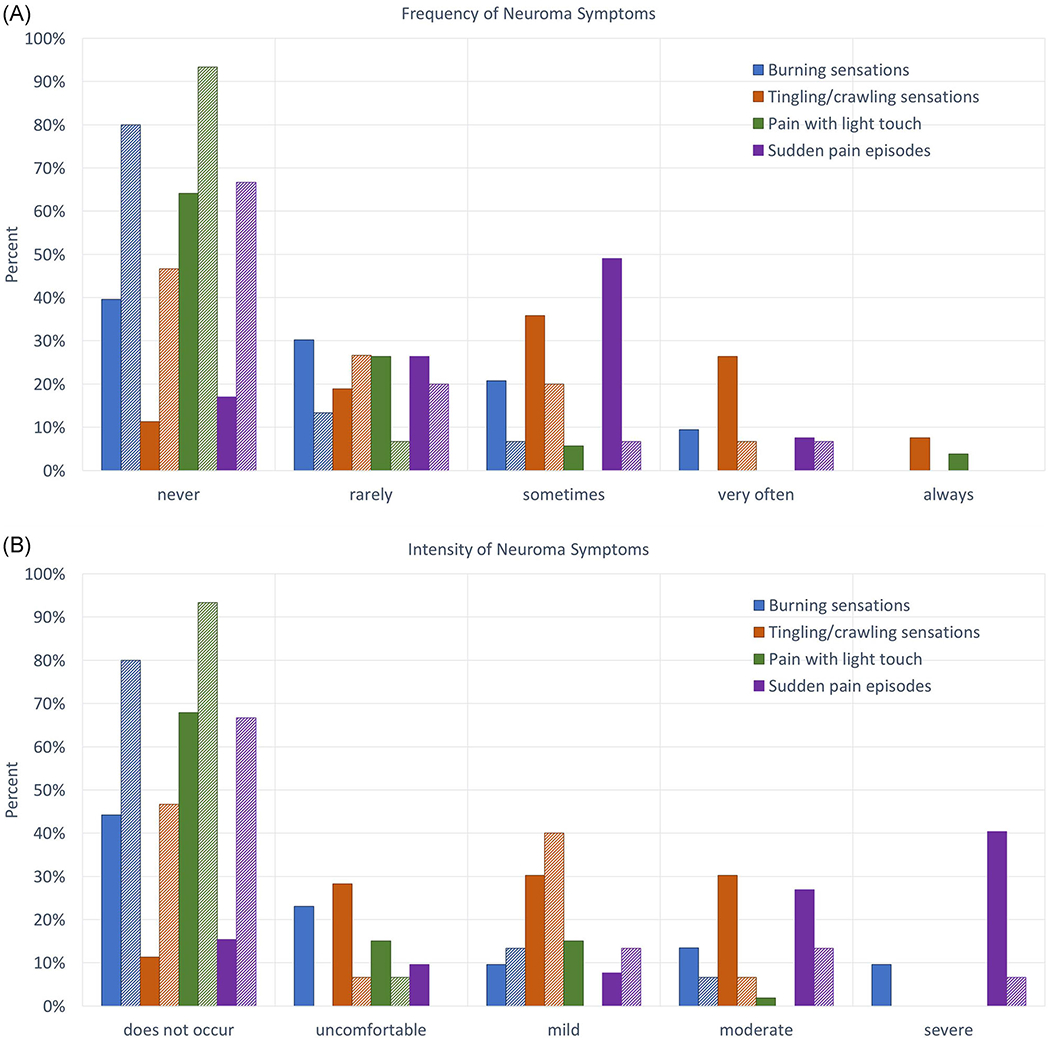

Demographics and details of amputation were similar between TMR and general oncologic amputee cohorts with the exception of time since amputation (Table 2). Outcomes were analyzed for patients with greater than 1-year follow-up. Neuroma symptoms, specifically burning sensations (Figure 2), tingling or crawling sensations (Figure 2), pain with light touch (Figure 2), and sudden pain episodes at the amputation site (Figure 2), occurred less frequently and with less intensity in the TMR cohort (all P < .05; Table 3). No differences were observed in hot or cold sensitivity or light pressure causing pain. Mean differences for PROMIS pain intensity, behavior, and interference for PLP were 5.855 (95%CI 1.159, 10.55; P = .015), 5.896 (95%CI 0.492, 11.30; P = .033), and 7.435 (95%CI 1.797, 13.07; P = .011), respectively, with lower scores for the TMR cohort (Table 4). For residual limb pain, PROMIS pain intensity, pain behavior, and pain interference mean differences were 5.477 (95%CI 0.528, 10.42; P = .031), 6.195 (95%CI 0.705, 11.69; P = .028), and 6.816 (95%CI 1.438, 12.2; P = .014), respectively. Comparison of TMR patients with greater than 1 year follow-up to TMR patients with less than 1 year follow-up demonstrated no significant differences (Supporting Information Table). Minimally important difference (MID) for health-related quality of life measures may be estimated as one-half of a standard deviation or five t-score points.87 Among advanced-stage cancer patients, MID for PROMIS pain interference is estimated to be between 4.0 and 6.0.88 In summary, pain measures across the board were statistically and meaningfully favorable for the TMR cohort.

TABLE 2.

Demographic and amputation variables

| All |

>1 y |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | TMR, N = 27 N (%) | General, N = 58 N (%) | P value | TMR, N = 15 N (%) | General, N = 53 N (%) | P value |

| Age (mean, range) | 53.5 (18-85) | 53.6 (25-77) | .990 | 48.5 (18-85) | 55.2 (25-77) | .148 |

| Male | 17 (63%) | 31 (53%) | .410 | 12 (80%) | 27 (51%) | .045 |

| Race | .733 | .727 | ||||

| Black/African American | 2 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| White | 24 (89%) | 53 (91%) | 14 (93%) | 48 (91%) | ||

| Other | 1 (4%) | 4 (7%) | 1 (7%) | 4 (8%) | ||

| Time since amputation | <.05 | <.05 | ||||

| <1 y | 11 (41%) | 5 (9%) | Excluded | |||

| 1-4 y | 16 (59%) | 18 (31%) | 15 (100%) | 18 (34%) | ||

| >5 y | 0 (0%) | 35 (60%) | 0 (0%) | 35 (66%) | ||

| Level of amputation | .274 | .339 | ||||

| Below elbow | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | ||

| Below knee | 7 (26%) | 15 (26%) | 6 (40%) | 14 (26%) | ||

| Above elbow | 3 (11%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | ||

| Above/through knee | 13 (48%) | 29 (50%) | 7 (47%) | 26 (49%) | ||

| Shoulder disarticulation | 3 (11%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (13%) | 2 (4%) | ||

| Hip disarticulation/ hemipelvectomy | 1 (4%) | 9 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (15%) | ||

Abbreviation: TMR, targeted muscle reinnervation.

FIGURE 2.

Frequency (A) and intensity (B) of neuroma symptoms at last follow-up. Dark solid bars represent the general cohort; lighter shaded bars represent the TMR cohort. All general versus TMR comparisons are statistically significant by nonparametric regression with P < .05. TMR, targeted muscle reinnervation [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

TABLE 3.

Neuroma symptom frequency and intensity for oncologic amputees at least 1 year from amputation

| Median Frequency/intensity TMR, N = 15 | Median Frequency/intensity General, n = 53 | U Frequency/intensity | P Frequency/intensity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burning sensations | Never/none | Rarely/uncomfortable | 226.5/256.5 | .006/.029 |

| Tingling/crawling sensations | Rarely/uncomfortable | Sometimes/mild | 183.5/253.5 | .001/.027 |

| Pain with light touch | Never/none | Never/none | 279/292 | .028/.044 |

| Sudden pain episodes | Never/none | Sometimes/moderate | 180/159.5 | .001/<.001 |

| Hot/cold pain sensitivity | Never/none | Never/none | 322.5/315 | .072/.057 |

| Pain with pressure | Never/none | Never/none | 362/384.5 | 561/.829 |

Note: P < .05 denotes significantly different distributions Abbreviation: TMR, targeted muscle reinnervation.

TABLE 4.

PROMIS pain outcomes for oncologic amputees at least 1 year from amputation

| Mean difference | 95%CI lower, upper | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phantom limb pain (PLP) | |||

| Pain intensity | 5.855 | 1.159, 10.55 | .015 |

| Pain behavior | 5.896 | 0.491, 11.30 | .033 |

| Pain interference | 7.435 | 1.797, 13.07 | .011 |

| Residual limb pain (RLP) | |||

| Pain intensity | 5.477 | 0.528, 10.42 | .031 |

| Pain behavior | 6.195 | 0.705, 11.69 | .028 |

| Pain interference | 6.816 | 1.438, 12.19 | .014 |

Note: P < .05 denotes significance.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

4 |. DISCUSSION

4.1 |. Defining an oncologic amputee center of excellence

When amputation is indicated for oncologic reasons, a multidisciplinary team approach can maximize outcomes. The Sarcoma Division at The James Cancer and Solove Research Institute at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center has developed an oncologic amputee program in which limb optimization begins with prehabilitation to set patient expectations, continues with intraoperative collaboration between the oncology and plastic surgery teams to perform the resection and subsequent TMR, and a patient-specific postoperative rehabilitation. All of this occurs in the setting of a comprehensive cancer center where a close relationship exists between medical, radiation, and surgical oncologists who work together to address cancer-specific considerations in the oncologic amputee population.

In our study, TMR reduced patient-reported phantom and residual limb pain behavior and interference compared to unselected general oncologic amputee controls beyond the clinically meaningful threshold for this population. Raw PROMIS pain interference scores in our study population undergoing amputation with concurrent TMR for oncologic diagnoses demonstrated favorable outcomes in comparison to both oncologic amputees and limb salvage patients in the recent study by Wilke et al.89 In a population with similar follow-up, they demonstrated PROMIS pain interference scores of 53.8 and 53.3 for limb salvage and amputation respectively. These are both higher (more pain interference) than our findings of phantom pain related pain interference of 42.1 and 46.2 for >1 year and <1 year follow-up, respectively, and residual limb pain related pain interference of 44.0 and 44.1 for >1 year and <1 year follow-up, respectively, after TMR. In addition, TMR patients experience less frequent and intense residual limb sensations and sudden pain and relatively low rates of opioid utilization. Notably, we also found that when pure sensory nerves such as the medial antebrachial cutaneous and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves are not included in the initial nerve transfer, symptomatic neuromas may develop leading to reoperation. This finding triggered a change in our practice to include these nerves in subsequent transfers. Finally, postoperative care can be enhanced through multimodal pain management, patient-centered rehabilitation, and finally, a peer support network that plays a crucial role throughout the entire process.

Our multidisciplinary approach was informed by lessons from the military community where recent conflicts have necessitated medical advance. Programs such as the US Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, the Center for the Intrepid at Brooke Army Medical Center, and Veterans Administration Regional Amputation Centers provide a comprehensive medical home for the rehabilitation of combat-related amputees and have been shown to have a positive impact on their patients’ recovery by providing durable provider-patient relationships, open communication, easy accessibility, and peer support.76,90 The application of military medical practices in civilian medical institutions, specifically those caring for oncology populations, requires acknowledgment of their similarities and differences. Both oncologic and combat-related amputees may have high expectations for postamputation activity, and both may include young men and women. However, oncology patients may have additional medical comorbidities, metastatic disease, need for adjuvant therapies including chemotherapy and/or radiation, different emotional coping strategies due to the reason for their amputation, and overall life expectancy. With these differences in mind, it is recognized that the oncology population requires a dedicated team at a facility equipped and invested in their care to optimize both their oncologic and functional outcomes after amputation.

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. We have developed our institutional protocol based on the experience of our team members and patients over time. The patient population is heterogeneous and relatively small due to the rare nature of extremity-based malignancies necessitating amputation. Patient-reported data was analyzed at last follow-up and not tracked longitudinally to examine the effects of specific rehabilitative interventions or medication changes on pain. Surgical details, oncologic details, and opioid use were unavailable for the control cohort. We assumed that the cross-sectional survey represented the current standard of care in the United States. Furthermore, there is a significant difference in the follow-up between the control and TMR cohorts. However, previous studies have shown that the prevalence of postamputation pain, in particular, phantom limb and residual limb pain, improves with time in the general population,17 but plateaus to slightly increases with greater than 1-year follow-up.59 Most patients experience mild symptoms in the long-term, but approximately 25%-33% continue to experience debilitating symptoms.4 In contrast, our experience with TMR has shown continued improvement after 1 year in NRS pain scores after the treatment of symptomatic neuromas59 and our unpublished experience has found continued improvement in postamputation pain 1 year after primary TMR. Due to these findings, we would expect the differences between the control and TMR group to be greater with more pain experienced by the control group with shorter follow-up. Since a statistically and clinically significant difference was identified in our study between the intervention group with shorter follow-up and the control group with longer follow-up) we would expect our results to remain significant with matched follow-up of the control group.

Given the lack of long-term follow-up for patients undergoing TMR, the durability of the TMR effect is unknown. However, given the biologic healing that occurs at the nerve endings, we anticipate the effect to be long-lasting.

The use of the OARRS for assessing opioid use is limited by the nature of the data generated. The OARRS report represents prescriptions filled by the patient but does not necessarily reflect daily or actual opioid consumption. In our previous work, however, the OARRS data were consistent with self-reported use with greater than 90% agreement.91 Finally, formal assessments including functional outcomes measures and detailed prosthetic use information were beyond the scope of our investigation. Despite these limitations, this is the largest case series to-date of concurrent TMR in patients undergoing amputation for malignant diagnoses and our findings provide early support for the strategy and the basis for further clinical investigations.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

Multidisciplinary care of the oncologic amputee that includes TMR at the time of resection, multimodal postoperative pain management, amputee-centered rehabilitation, and peer support has demonstrated favorable outcomes for reducing the incidence and severity of painful neuroma and PLP. The multidisciplinary team of medical, radiation, orthopedic and surgical oncologists, plastic surgeons, and oncology rehabilitation therapists working in concert in the care of an oncologic amputee defines, for us, an Oncologic Amputee Center of Excellence. Dedicated programs such as these will ignite innovation and serve as proving grounds for new technologies and treatment strategies for the oncologic amputee.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, Travison TG, Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:422–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert RS, Ottaviani G, Huh WW, et al. Psychosocial and functional outcomes in long-term survivors of osteosarcoma: a comparison of limb-salvage surgery and amputation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:990–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ephraim PL, Wegener ST, MacKenzie EJ, et al. Phantom pain, residual limb pain, and back pain in amputees: results of a national survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1910–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehde DM, Czerniecki JM, Smith DG, et al. Chronic phantom sensations, phantom pain, residual limb pain, and other regional pain after lower limb amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:1039–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith DG, Ehde DM, Legro MW, et al. Phantom limb, residual limb, and back pain after lower extremity amputations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;361:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchheit T, Van deVen T, Hsia HL, et al. Pain phenotypes and associated clinical risk factors following traumatic amputation: results from Veterans Integrated Pain Evaluation Research (VIPER). Pain Med. 2016;17:149–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pet MA, Ko JH, Friedly JL, Smith DG. Traction neurectomy for treatment of painful residual limb neuroma in lower extremity amputees. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:e321–e325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernadakis AJ, Koch H, Mackinnon SE. Management of neuromas. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30:247–268vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE. Treatment of the painful neuroma by neuroma resection and muscle implantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:427–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein SA, Sturim HS. Intraosseous nerve transposition for treatment of painful neuromas. J Hand Surg Am. 1985;10:270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemmy DC. Intramedullary nerve implantation in amputation and other traumatic neuromas. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:842–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boldrey E Amputation neuroma in nerves implanted in bone. Ann Surg. 1943;118:1052–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch H, Hubmer M, Welkerling H, et al. The treatment of painful neuroma on the lower extremity by resection and nerve stump transplantation into a vein. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25:476–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balcin H, Erba P, Wettstein R, et al. A comparative study of two methods of surgical treatment for painful neuroma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:803–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belcher HJ, Pandya AN. Centro-central union for the prevention of neuroma formation after finger amputation. J Hand Surg Br. 2000;25:154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbera J, Albert-Pamplo R. Centrocentral anastomosis of the proximal nerve stump in the treatment of painful amputation neuromas of major nerves. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:331–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen TS, Krebs B, Nielsen J, Rasmussen P. Immediate and long-term phantom limb pain in amputees: incidence, clinical characteristics and relationship to pre-amputation limb pain. Pain. 1985;21:267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen TS, Krebs B, Nielsen J, Rasmussen P. Phantom limb, phantom pain and stump pain in amputees during the first 6 months following limb amputation. Pain. 1983;17:243–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce RO Jr., Kernek CB, Ambrose TA 2nd. The plight of the traumatic amputee. Orthopedics. 1993;16:793–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hertel R, Strebel N, Ganz R. Amputation versus reconstruction in traumatic defects of the leg: outcome and costs. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10:223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikolajsen L, Ilkjaer S, Kroner K, et al. The influence of preamputation pain on postamputation stump and phantom pain. Pain. 1997;72:393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherman RA, Sherman CJ, Parker L. Chronic phantom and stump pain among American veterans: results of a survey. Pain. 1984;18:83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherman RA, Sherman CJ. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic phantom limb pain among American veterans. Results of a trial survey. Am J Phys Med. 1983;62:227–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikolajsen L, Staehelin Jensen T. Phantom limb pain. Curr Rev Pain. 2000;4:166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krane EJ, Heller LB. The prevalence of phantom sensation and pain in pediatric amputees. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith J, Thompson JM. Phantom limb pain and chemotherapy in pediatric amputees. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgoyne LL, Billups CA, Jiron JL Jr., et al. Phantom limb pain in young cancer-related amputees: recent experience at St Jude children’s research hospital. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:222–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daigeler A, Lehnhardt M, Khadra A, et al. Proximal major limb amputations--a retrospective analysis of 45 oncological cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grimer RJ, Chandrasekar CR, Carter SR, et al. Hindquarter amputation: is it still needed and what are the outcomes? Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B:127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parsons CM, Pimiento JM, Cheong D, et al. The role of radical amputations for extremity tumors: a single institution experience and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elbert T, Rockstroh B. Reorganization of human cerebral cortex: the range of changes following use and injury. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:129–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flor H, Elbert T, Knecht S, et al. Phantom-limb pain as a perceptual correlate of cortical reorganization following arm amputation. Nature. 1995;375:482–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Preissler S, Feiler J, Dietrich C, et al. Gray matter changes following limb amputation with high and low intensities of phantom limb pain. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:1038–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giummarra MJ, Moseley GL. Phantom limb pain and bodily awareness: current concepts and future directions. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011;24:524–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montoya P, Ritter K, Huse E, et al. The cortical somatotopic map and phantom phenomena in subjects with congenital limb atrophy and traumatic amputees with phantom limb pain. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:1095–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsu E, Cohen SP. Postamputation pain: epidemiology, mechanisms, and treatment. J Pain Res. 2013;6:121–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alviar MJ, Hale T, Dungca M. Pharmacologic interventions for treating phantom limb pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10CD006380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clerici CA, Spreafico F, Cavallotti G, et al. Mirror therapy for phantom limb pain in an adolescent cancer survivor. Tumori. 2012;98:e27–e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolognini N, Olgiati E, Maravita A, et al. Motor and parietal cortex stimulation for phantom limb pain and sensations. Pain. 2013;154:1274–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enneking FK, Scarborough MT, Radson EA. Local anesthetic infusion through nerve sheath catheters for analgesia following upper extremity amputation. Clinical report. Reg Anesth. 1997;22:351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaddoum RN, Burgoyne LL, Pereiras JA, et al. Nerve sheath catheter analgesia for forequarter amputation in paediatric oncology patients. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2013;41:671–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lambert A, Dashfield A, Cosgrove C, et al. Randomized prospective study comparing preoperative epidural and intraoperative perineural analgesia for the prevention of postoperative stump and phantom limb pain following major amputation. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26:316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nikolajsen L, Finnerup NB, Kramp S, et al. A randomized study of the effects of gabapentin on postamputation pain. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1008–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morey TE, Giannoni J, Duncan E, et al. Nerve sheath catheter analgesia after amputation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;397:281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherman RA, Sherman CJ, Gall NG. A survey of current phantom limb pain treatment in the United States. Pain. 1980;8:85–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuiken TA, Dumanian GA, Lipschutz RD, et al. The use of targeted muscle reinnervation for improved myoelectric prosthesis control in a bilateral shoulder disarticulation amputee. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2004;28:245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hijjawi JB, Kuiken TA, Lipschutz RD, et al. Improved myoelectric prosthesis control accomplished using multiple nerve transfers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:1573–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuiken TA, Miller LA, Lipschutz RD, et al. Targeted reinnervation for enhanced prosthetic arm function in a woman with a proximal amputation: a case study. Lancet. 2007;369:371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Shaughnessy KD, Dumanian GA, Lipschutz RD, et al. Targeted reinnervation to improve prosthesis control in transhumeral amputees. A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuiken TA, Li G, Lock BA, et al. Targeted muscle reinnervation for real-time myoelectric control of multifunction artificial arms. JAMA. 2009;301:619–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dumanian GA, Ko JH, O’Shaughnessy KD, et al. Targeted reinnervation for transhumeral amputees: current surgical technique and update on results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:863–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheesborough JE, Smith LH, Kuiken TA, Dumanian GA. Targeted muscle reinnervation and advanced prosthetic arms. Semin Plast Surg. 2015;29:62–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuiken TA, Barlow AK, Hargrove L, Dumanian GA. Targeted muscle reinnervation for the upper and lower extremity. Tech Orthop. 2017;32:109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Agnew SP, Schultz AE, Dumanian GA, Kuiken TA. Targeted reinnervation in the transfemoral amputee: a preliminary study of surgical technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gart MS, Souza JM, Dumanian GA. Targeted muscle reinnervation in the upper extremity amputee: a technical roadmap. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:1877–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morgan EN, Kyle Potter B, Souza JM, et al. Targeted muscle reinnervation for transradial amputation: description of operative technique. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2016;20:166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim PS, Ko JH, O’Shaughnessy KK, et al. The effects of targeted muscle reinnervation on neuromas in a rabbit rectus abdominis flap model. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:1609–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Souza JM, Cheesborough JE, Ko JH, et al. Targeted muscle reinnervation: a novel approach to postamputation neuroma pain. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2984–2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dumanian GA, Potter BK, Mioton LM, et al. Targeted muscle reinnervation treats neuroma and phantom pain in major limb amputees: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2018. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003088 [published online ahead of print Octoberber 26, 2018]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Serino A, Akselrod M, Salomon R, et al. Upper limb cortical maps in amputees with targeted muscle and sensory reinnervation. Brain. 2017;140:2993–3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen A, Yao J, Kuiken T, Dewald JP. Cortical motor activity and reorganization following upper-limb amputation and subsequent targeted reinnervation. Neuroimage Clin. 2013;3:498–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mioton LM, Dumanian GA. Targeted muscle reinnervation and prosthetic rehabilitation after limb loss. J Surg Oncol. 2018;118:807–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ong BY, Arneja A, Ong EW. Effects of anesthesia on pain after lower-limb amputation. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18:600–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roullet S, Nouette-Gaulain K, Biais M, et al. Preoperative opioid consumption increases morphine requirement after leg amputation. Can J Anaesth. 2009;56:908–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elizaga AM, Smith DG, Sharar SR, et al. Continuous regional analgesia by intraneural block: effect on postoperative opioid requirements and phantom limb pain following amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1994;31:179–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bosanquet DC, Glasbey JC, Stimpson A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of perineural local anaesthetic catheters after major lower limb amputation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50:241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huse E, Larbig W, Flor H, Birbaumer N. The effect of opioids on phantom limb pain and cortical reorganization. Pain. 2001;90:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bone M, Critchley P, Buggy DJ. Gabapentin in postamputation phantom limb pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith DG, Ehde DM, Hanley MA, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin in treating chronic phantom limb and residual limb pain. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42:645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Silver JK, Baima J, Newman R, et al. Cancer rehabilitation may improve function in survivors and decrease the economic burden of cancer to individuals and society. Work. 2013;46:455–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Silver JK, Raj VS, Fu JB, et al. Cancer rehabilitation and palliative care: critical components in the delivery of high-quality oncology services. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:3633–3643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stout NL, Silver JK, Raj VS, et al. Toward a National Initiative in Cancer Rehabilitation: recommendations from a subject matter expert group. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:2006–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stubblefield MD. Neuromuscular complications of radiation therapy. Muscle Nerve. 2017;56:1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Messinger S, Bozorghadad S, Pasquina P. Social relationships in rehabilitation and their impact on positive outcomes among amputees with lower limb loss at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wells LM, Schachter B, Little S, et al. Enhancing rehabilitation through mutual aid: outreach to people with recent amputations. Health Soc Work. 1993;18:221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ussher J, Kirsten L, Butow P, Sandoval M. What do cancer support groups provide which other supportive relationships do not? The experience of peer support groups for people with cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:2565–2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150:173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Askew RL, Cook KF, Revicki DA, et al. Evidence from diverse clinical populations supported clinical validity of PROMIS pain interference and pain behavior. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:103–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen W-H, Revicki D, Amtmann D, et al. Development and Analysis of PROMIS Pain Intensity Scale. Qual Life Res. 2012;20(1):18. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Revicki DA, Chen WH, Harnam N, et al. Development and psychometric analysis of the PROMIS pain behavior item bank. Pain. 2009;146:158–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alamanda VK, Crosby SN, Archer KR, et al. Amputation for extremity soft tissue sarcoma does not increase overall survival: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:1178–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Puhaindran ME, Chou J, Forsberg JA, Athanasian EA. Major upper-limb amputations for malignant tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:1235–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rougraff BT, Simon MA, Kneisl JS, et al. Limb salvage compared with amputation for osteosarcoma of the distal end of the femur. A long-term oncological, functional, and quality-of-life study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Clark MA, Thomas JM. Major amputation for soft-tissue sarcoma. Br J Surg. 2003;90:102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yost KJ, Eton DT, Garcia SF, Cella D. Minimally important differences were estimated for six Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Cancer scales in advanced-stage cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:507–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wilke B, Cooper A, Scarborough M, et al. A comparison of limb salvage versus amputation for nonmetastatic sarcomas using patient-reported outcomes measurement information system outcomes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27:e381–e389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Meier RH 3rd, Heckman JT. Principles of contemporary amputation rehabilitation in the United States, 2013. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25:29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Valerio IL, Dumanian GA, Jordan SW, et al. Targeted muscle reinnervation (TMR) at the time of major limb amputation decreases phantom and residual limb pain. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228:217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.