Abstract

Background

Neonatal male circumcision is a painful skin-breaking procedure that may affect infant physiological and behavioral stress responses as well as mother-infant interaction. Due to the plasticity of the developing nociceptive system, neonatal pain might carry long-term consequences on adult behavior. In this study, we examined whether infant male circumcision is associated with long-term psychological effects on adult socio-affective processing.

Methods

We recruited 408 men circumcised within the first month of life and 211 non-circumcised men and measured socio-affective behaviors and stress via a battery of validated psychometric scales.

Results

Early-circumcised men reported lower attachment security and lower emotional stability while no differences in empathy or trust were found. Early circumcision was also associated with stronger sexual drive and less restricted socio-sexuality along with higher perceived stress and sensation seeking.

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional study relying on self-reported measures from a US population.

Conclusions

Our findings resonate with the existing literature suggesting links between altered emotional processing in circumcised men and neonatal stress. Consistent with longitudinal studies on infant attachment, early circumcision might have an impact on adult socio-affective traits or behavior.

Keywords: Psychology, Clinical research, Neonatal pain, Attachment style, Empathy, Personality, Stress, Sociosexuality

Psychology; Clinical research; Neonatal pain; Attachment style; Empathy; Personality; Stress; Sociosexuality.

1. Introduction

Routine, non-therapeutic infant male circumcision is the most commonly performed surgery in the United States (Maeda et al., 2012; Weiss and Elixhauser, 2014). Approximately one-third of males in the world are circumcised (World Health Organization, 2010), primarily for cultural reasons. Nevertheless, the social and health-related aspects of newborn circumcision, including the degree and magnitude of associated benefits and risks, remain contentious and hotly debated (Darby, 2015; Freedman, 2016; Myers and Earp, 2020). Relatively little research has investigated pain-related responses to circumcision in infants (Dixon et al., 1984; Fergusson et al., 2007; Gattari et al., 2013; Gunnar et al., 1981, 1995; Marshall et al., 1980, 1982; Mondzelewski et al., 2016; Page, 2004; Svoboda and Van Howe, 2013; Taddio et al., 1997a, 1997b; Talbert et al., 1976; Williamson et al., 1986; Williamson and Williamson, 1983), and only a handful of studies have generated evidence regarding potential long-term effects lasting into adulthood (Bauer and Kriebel, 2013; Bollinger and Van Howe, 2011; Frisch and Simonsen, 2015a; Ullmann et al., 2017). The small number of studies that have investigated long-term effects have been argued to exhibit methodological flaws and limitations (Boyle, 2017; Morris et al., 2012; Morris and Wiswell, 2015) leading to calls for further research in this area (Bollinger and Van Howe, 2012; Frisch and Simonsen, 2015b).

Indicators of likely infant pain experience overlap considerably with those seen in adults. Administration of noxious stimuli to infants activates 18 of the 20 adult brain regions activated during pain experience (Goksan et al., 2015). Due to the plasticity of the developing nociceptive system, the effects of such stimulation may persist into adolescence (AAP, 2016; Hohmeister et al., 2010; Schmelzle-Lubiecki et al., 2007; Walker, 2019). In addition to tracheal intubation or suctioning, catheter insertion, chest tube placement, heel lancing, lumbar puncture, and subcutaneous or intramuscular injections, often associated with neonatal intensive care units (Anand et al., 2001; Simons et al., 2003), penile circumcision is one of the most common sources of pain in (male) newborns. Such circumcision can elicit clinically significant pain responses even when analgesia is used (Banieghbal, 2009, as discussed in Frisch and Earp, 2018), and indications of extreme pain when, as frequently occurs, no analgesia is used (Brady-Fryer et al., 2004; Elhaik, 2018). As recently as the 1990s, large majorities of surveyed physicians reported using no analgesia for newborn male circumcision (Wellington and Rieder, 1993), with many training programs failing to provide any instruction in pain relief for the procedure (Howard et al., 1998).

Because the penile prepuce (foreskin) is normally fused to the head of the penis at birth, these structures must often be forced apart with the application of a blunt probe (Machmouchi and Alkhotani, 2007). Depending on the method, a clamp or other device is then used to crush the prepuce for purposes of hemostasis, followed by excision of the tissue (World Health Organization, 2009). During these procedures, infants’ heart rate and blood pressure increase significantly while cortisol levels elevate 3 to 4-fold, remaining elevated up to several days (Gunnar et al., 1981, 1995; Page, 2004; Talbert et al., 1976; Williamson et al., 1986; Williamson and Williamson, 1983). Even with “gold standard” subcutaneous ring blog for analgesia along with intraoperative sucrose, cortisol levels more than double with use of the popular Gomco clamp (Sinkey et al., 2015). Some studies have found that parent-infant bonding following circumcision is disrupted, marked by altered breastfeeding and sleep patterns as well as higher infant irritability (Dixon et al., 1984; Marshall et al., 1982; 1980; Richards et al., 1976; for discussion, see Svoboda and Van Howe, 2013), while others do not find evidence of such behavioral changes (Fergusson et al., 2007; Gattari et al., 2013; Mondzelewski et al., 2016). Circumcised infants display increased pain responses during subsequent vaccination, suggesting that behavioral effects of the surgery can last, at a minimum, up to 4–6 months (Taddio et al., 1997a).

Despite the fact that neonatal circumcision occurs in the US within the most crucial neurodevelopmentally plastic period of an individual's life, very little research has been conducted on its long-term effects. Previous preliminary research has reported an association between circumcision and alexithymia (i.e., dysfunctions in emotion recognition, social attachment, and interpersonal relations) in adults (Bollinger and Van Howe, 2011). More recently, two large-sample studies suggested a positive correlation between circumcision and autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Bauer and Kriebel, 2013; Frisch and Simonsen, 2015a). Although the causal implications of this research has been questioned (Morris et al., 2012; Morris and Wiswell, 2015), these studies suggest that early-circumcision might have an impact on adult psychosocial functioning. It has been extensively debated whether circumcision affects sexual outcome variables, including sensation and satisfaction (e.g., Bossio et al., 2014; Boyle, 2015; Earp, 2016; Morris and Krieger, 2015), with research in this area often conflating studies of newborn versus adult circumcision. It is also contentious whether early-circumcised males experience long-term alterations within the limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (LHPA) system; and whether potential stress in this regard is connected to developmental factors. The only study that, to our knowledge, examined this issue was statistically underpowered (Boyle, 2017), using a sample of only 9 circumcised participants (Ullmann et al., 2017). Nevertheless, despite being underpowered, the trend in the data were consistent with the hypothesized decrease in long-term activation of the LHPA axis among early-circumcised males, as assessed through both hair cortisol and cortisone levels (Boyle, 2017; Ullmann et al., 2017). Finally, one recent study has found that neonatal male circumcision and prematurity were associated with Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), providing support for the allostatic load hypothesis (i.e., the result of cumulative perinatal painful, stressful, or traumatic events) as an explanation for SIDS (Elhaik, 2018).

Overall, the research so far suggests that neonatal circumcision is a painful procedure that elicits the stress response and it might have long-term effects. The life-history (or “psychosocial acceleration”) theory proposes that early stress, within a period of heightened vulnerability and dependency, such as infancy, leads to the development of a fast (vs. slow) life-history trajectory. Such life-history strategies are hypothesized to be adaptive responses to harsh and stressful environments in order to optimize reproductive and survival fitness, organizing behavior in multiple domains such as risk-taking, self-regulation, resource exploitation, aggression, exploration, sexual maturity, mating, and caregiving (Del Giudice, 2016; Del Giudice et al., 2005; Shakiba et al., 2020). Therefore, in the present study, we explore the relationship between neonatal circumcision and adult psychosocial outcomes, addressing this issue from a stress and developmental perspective. We examine whether early-circumcised men show differences in developmentally-forged traits including personality and attachment styles that, depending on caregiver interactions, appear early in life (Abe and Izard, 1999; DeYoung et al., 2002; Young et al., 2017), and tend to remain stable throughout the lifespan (Young et al., 2017).

Consistent with the life-history theory, we hypothesize that adults who underwent neonatal circumcision, compared to those who did not, will display alterations in socio-affective processing conforming to the fast life-history strategies, namely, decreased reliance on social environment and increased perceived stress and sexual activity. Specifically, here we test whether early-circumcised men, compared to men who did not undergo neonatal circumcision, display higher attachment insecurity and emotional instability (i.e., impaired functioning in emotional, motivational, and social domains), lower empathy and trust, higher sexual libido and unrestricted sociosexuality (i.e., preference of short- over long-term mating), as well as higher stress and risk taking attitudes.

The present research is framed within the context of developmental and socio-affective psychology. Therefore, questions about whether neonatal circumcision is ethical (Abdulcadir et al., 2019; Benatar and Benatar, 2003; Earp, 2013), is associated with therapeutic benefit (e.g., reduction in sexually transmitted and urinary tract infections as well as penile cancer; AAP, 2012; Dave et al., 2018; Frisch et al., 2013) or risks (e.g., meatal stenosis, loss of the glans or the whole penis; Fahmy, 2019; Krill et al., 2011), or changes in sexual sensation, function, satisfaction, or body image (Bossio et al., 2016; Bossio and Pukall, 2018; Earp, 2016; Hammond and Carmack, 2017), fall outside the scope of this research.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 744 Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) participants completed an online survey using the TurkPrime interface between July and December 2017. TurkPrime is a research platform linked with MTurk and supports tasks that are common to the social and behavioral sciences (Litman et al., 2017). MTurk respondents are a subset of workers who decide to complete a given task; hence participation is voluntary (Stewart et al., 2017). Because circumcision is sometimes associated with religious practice, here we attempted to limit this potentially confounding variable. To do this, we chose a general US sample since neonatal circumcision is commonly practiced in the US within the first week of life regardless of religious faith. All participants were currently living in the US, which ensured language competence when completing self-report questionnaires (Chandler and Shapiro, 2016; Litman et al., 2015).

Because we were interested in early (i.e., neonatal) circumcision, we focused on men who stated that they were circumcised within the first month of life (early-circumcised men, EC, N = 408) and men claiming to be non-circumcised (NC, N = 211). Hence the final sample included 619 participants (see Table 1 for demographic characteristics). Respondents were given an anonymous random-generated user ID. Only demographic data (no personal identifiers) were collected. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent was obtained from all participants before starting the survey. No further ethics approval was required for the conduct of this study since biological samples were not collected, according to the Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of early-circumcised (EC) and non-circumcised (NC) participants.

| Total | Total sample |

Early circumcised |

Non circumcised |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 619 | 408 | 69.27% | 211 | 35.82% | ||||

| Age [mean SD] | 34.91 |

9.99 |

35.98 |

10.36 |

32.85 |

8.90 |

t484.39 = 3.91, p < .001 |

|

|

Circumcision reasons |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

||

| Hygiene | 91 | 22.30% | - | - | ||||

| I don't know why | 236 | 57.84% | - | - | ||||

| Medical reasons | 24 | 05.88% | - | - | ||||

| Other | 10 | 02.45% | - | - | ||||

| Religion | 47 | 11.52% | - | - | ||||

| missing | 0 |

00.00% |

||||||

|

Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Black or African American | 46 | 07.43% | 28 | 06.86% | 18 | 08.53% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 49 | 07.92% | 13 | 03.19% | 36 | 17.06% | ||

| White | 462 | 74.64% | 341 | 83.58% | 121 | 57.35% | ||

| Other | 58 | 09.37% | 22 | 05.39% | 36 | 17.06% | X23 = 67.16, p < .001 | |

| missing | 4 |

00.65% |

4 |

00.98% |

0 |

00.00% |

||

|

Sexual orientation | ||||||||

| Bisexual | 24 | 03.88% | 15 | 03.68% | 9 | 04.27% | ||

| Heterosexual | 571 | 92.25% | 379 | 92.89% | 192 | 91.00% | ||

| Homosexual | 21 | 03.39% | 12 | 02.94% | 9 | 04.27% | ||

| Other | 3 | 00.48% | 2 | 00.49% | 1 | 00.47% | X23 = 0.90, p = .826 | |

| missing | 0 |

00.00% |

0 |

00.00% |

0 |

00.00% |

||

|

Is in a relationship | ||||||||

| No | 247 | 39.90% | 153 | 37.50% | 94 | 44.55% | ||

| Yes | 346 | 55.90% | 240 | 58.82% | 106 | 50.24% | X21 = 3.55, p = .060 | |

| missing | 26 |

04.20% |

15 |

03.68% |

11 |

05.21% |

||

|

Education | ||||||||

| Bachelor | 288 | 46.53% | 189 | 46.32% | 99 | 46.92% | ||

| High School | 244 | 39.42% | 155 | 37.99% | 89 | 42.18% | ||

| Master | 53 | 08.56% | 40 | 09.80% | 13 | 06.16% | ||

| More than one Master | 5 | 00.81% | 5 | 01.23% | 0 | 00.00% | ||

| PhD | 4 | 00.65% | 3 | 00.74% | 1 | 00.47% | ||

| Primary | 1 | 00.16% | 0 | 00.00% | 1 | 00.47% | ||

| Technical | 24 | 03.88% | 16 | 03.92% | 8 | 03.79% | X26 = 7.46, p = .281 | |

| missing | 0 |

00.00% |

0 |

00.00% |

0 |

00.00% |

||

|

Occupation time | ||||||||

| Career of home, family, etc. full time | 2 | 00.32% | 1 | 00.25% | 1 | 00.47% | ||

| Other permanently unemployed e.g. chronically sick, independent means | 12 | 01.94% | 10 | 02.45% | 2 | 00.95% | ||

| Retired | 10 | 01.62% | 7 | 01.72% | 3 | 01.42% | ||

| Student full-time | 22 | 03.55% | 9 | 02.21% | 13 | 06.16% | ||

| Temporarily unemployed but actively seeking work | 31 | 05.01% | 22 | 05.39% | 9 | 04.27% | ||

| Working full- and part-time | 542 | 87.56% | 359 | 87.99% | 183 | 86.73% | X25 = 8.42, p = .135 | |

| missing | 0 |

00.00% |

0 |

00.00% |

0 |

00.00% |

||

|

Occupation type | ||||||||

| Armed Forces | 10 | 01.62% | 8 | 01.96% | 2 | 00.95% | ||

| Civil Service and local government | 21 | 03.39% | 19 | 04.66% | 2 | 00.95% | ||

| Education | 43 | 06.95% | 27 | 06.62% | 16 | 07.58% | ||

| Finance and banking | 60 | 09.69% | 42 | 10.29% | 18 | 08.53% | ||

| Manufacturing | 70 | 11.31% | 44 | 10.78% | 26 | 12.32% | ||

| Other service industries | 177 | 28.59% | 111 | 27.21% | 66 | 31.28% | ||

| Primary farming, fishing, mining, etc. | 12 | 01.94% | 8 | 01.96% | 4 | 01.90% | ||

| Professions in private practice | 107 | 17.29% | 74 | 18.14% | 33 | 15.64% | ||

| Selling, distribution and retailing | 99 | 15.99% | 62 | 15.20% | 37 | 17.54% | ||

| Transportation | 20 | 03.23% | 13 | 03.19% | 7 | 03.32% | X29 = 9.24, p = .415 | |

| missing | 0 | 00.00% | 0 | 00.00% | 0 | 00.00% | ||

2.2. Material

In contrast with previous online surveys that used titles such as “Global survey of circumcision harm” (Hammond and Carmack, 2017) and “Male circumcision trauma” (Bollinger and Van Howe, 2011), i.e., titles that might have biased participant recruitment, our survey title did not explicitly mention circumcision nor imply any negative connotations to circumcision (for a similar sampling approach, see Earp et al., 2018). Rather, focusing on “Penis morphology and sexual behavior” (see survey instructions in supplementary material, SM1), we asked participants several distractor questions about their penile status to divert attention away from circumcision status in particular. Moreover, in contrast to studies that have recruited participants through foreskin restoration websites, blogs devoted to men's issues, or genital autonomy-related social media, our survey was delivered via TurkPrime, a platform that is neutral with regard to circumcision. This approach, overall, allowed us to minimize selection bias. The survey took approximately 35 min to complete (without an imposed time limit and with the possibility of switching back and forth between questions) and all participants received US $4.00 compensation through their TurkPrime WorkerID (not stored).

The instruments that we used assessed a constellation of socio-affective variables, including attachment styles, personality traits, empathy, interpersonal trust, sexual libido, sociosexuality, stress, and sensation seeking. Attachment style was assessed using the Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (ECR-R) questionnaire (Fraley et al., 2000), which measures adult attachment avoidance (e.g., “I prefer not to show a partner how I feel deep down”) and attachment anxiety (e.g., “I'm afraid that I will lose my partner's love”). Personality traits were assessed with the Big Five Inventory (Costa and McCrae, 1992), which measures extraversion (e.g., “I see myself as someone who is talkative”), openness (e.g., “I see myself as someone who is original, comes up with new ideas”), agreeableness (e.g., “I see myself as someone who is helpful and unselfish with others”), neuroticism (e.g., “I see myself as someone who is depressed, blue”), and conscientiousness (e.g., “I see myself as someone who does a thorough job”). In addition, two personality meta-traits, namely, plasticity and stability, were examined by aggregating extraversion and openness for the meta-trait named plasticity, and conscientiousness, neuroticism (reversed), and agreeableness for the meta-trait named stability (DeYoung et al., 2002). The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI, Davis, 1980) was used for assessing empathy via measures of perspective taking (e.g., “I believe that there are two sides to every question and try to look at them both”) and empathic concern for others (e.g., “I am often quite touched by things that I see happen”). Trust was measured with the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, Naef and Schupp, 2009), which includes three dimensions: trust towards institutions (e.g., “How much trust do you have in parliament?”), trust towards strangers (e.g., “How much trust do you have in strangers?”), and trust towards known individuals (e.g., “How much trust do you have in friends?”). Sociosexuality (the preference for short-term mating strategies) was measured with the revised Sociosexual Orientation Inventory (SOI-R, Penke and Asendorpf, 2008). It captures three dimensions of sociosexuality such as behavior (frequency of uncommitted sex in the last year, e.g., “With how many different partners have you had sex within the past 12 months?”), attitude towards uncommitted sex (e.g., “Sex without love is OK”), and desire and sexual fantasies towards uncommitted sex (e.g., “In everyday life, how often do you have spontaneous fantasies about having sex with someone you have just met?”). The Sexual Desire Inventory (SDI, Spector et al., 1996) was used to assess both solitary (i.e., masturbation, e.g., “How strong is your desire to engage in sexual behavior by yourself?”) and dyadic (i.e., with a partner, e.g., “How strong is your desire to engage in sexual activity with a partner?”) sexual libido. Stress was assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS, Cohen and Williamson, 1988), in which participants appraise the overall perceived stress in various situations (e.g., “In the last month, how often how often have you felt nervous and stressed”). Sensation seeking, the need for novel experiences, and the willingness to take physical and social risks, was measured with the brief sensation seeking scale (SSS, Hoyle et al., 2002, e.g., “I like to do frightening things”).

Demographic data included age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, relationship status, education level, occupation type and time, and, if circumcised, the age of, and the reason for, the circumcision. Participants also responded to other measures not included in the present study but part of a broader project that aims at investigating in depth the relation between sexual behavior and circumcision.

2.3. Statistical analyses

The required sample size was determined a priori using a statistical power analysis, setting the power (1-β) at 0.95 and α at 0.05, and computing the effect size from the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the stress scale used in Ullman et al. (2017), which is the same as the one used in this study. With an effect size of d = 0.38, the projected sample size we needed was 181 participants per group. Thus, to account for potential participant drop out, exclusions, or missing values, we collected data to ensure at least 200 subjects per group.

Data analyses were performed in R (R Core Team, 2019). All measures had Cronbach alphas (computed using the “psych” package, Revelle, 2015) exceeding 0.81 (Mα = .87, range = .70 - .95) except for sociosexual behavior (α = .70) and trust towards known people (α = .76). We then checked for the presence of outliers, defined as values exceeding 2.5 SD from the mean. The percentage of outliers per each dependent variable was below 2% (except for dyadic sexual libido, which was 2.64%, Noutliers = 14). Given the negligible number of outliers, we decided not to remove observations nor apply any transformation to the data (for psychometric details, see table SM2 in supplementary material). Before running the main analysis, we performed a discriminant validity test employing a confirmatory factor analysis. All the latent factors loaded the respective items. Results showed satisfactory fit indexes, χ211153 = 23110.53, p < .001, RMSEA = .06, CFI = .94, SRMR = .06, with all loadings higher than .46 (ps < .001) with the exceptions of one loading (lambda = .27, p < .001) of the SOI scale. In addition, all variables represented separate constructs since the 95% confidence intervals did not include 1. Then, we tested whether the two groups, i.e., early-circumcised (EC) and non-circumcised (NC) men, differed in terms of demographic factors. There were differences regarding age (t484.39 = 3.91, p < .001), ethnicity (χ26 = 67.16, p < .001), and, marginally, relationship status (χ25 = 3.55, p = .060). Therefore, we decided to include those variables as covariates in subsequent analyses. Also, although marginally significant, we included relationship status as a covariate for theoretical reasons, namely, because of its impact on socio-affective behavior (Fraley et al., 2000; Rodriguez et al., 2015).

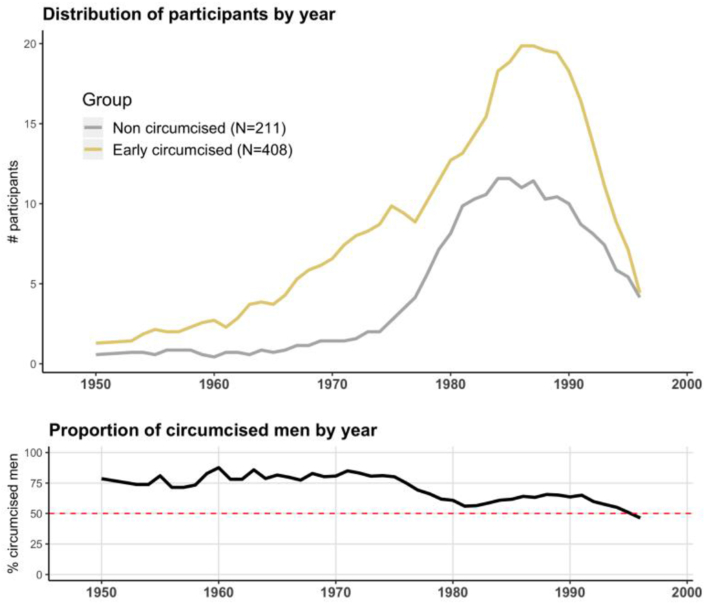

Demographic characteristics and distribution of age are reported in Table 1 and Figure 2. In the main analysis, using a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA), with age, ethnicity, and relationship status as covariates, we examined group differences for multi-domain psychological constructs such as attachment style, personality traits, empathy, trust, sociosexuality, and sexual libido. For each single domain, then, along with stress and sensation seeking, we tested group differences using univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with the same set of covariates. MANCOVAs and ANCOVAs were computed using the function “Anova” from the package “car” (Fox et al., 2014, with type III sum of squares to address differences in group sizes). For all analyses, the significance level was set at α = 0.05. Partial eta squared (η2p) is reported as measure of effect size so as to provide the proportion of variance associated only with group differences, partialling out the effects of other covariates. R squared (R2) is used instead to indicate the overall variance explained by all predictors (group and covariates).

Figure 2.

Distribution of year of birth (age) for early-circumcised and non-circumcised participants (above) and proportion of early-circumcised men (below).

3. Results

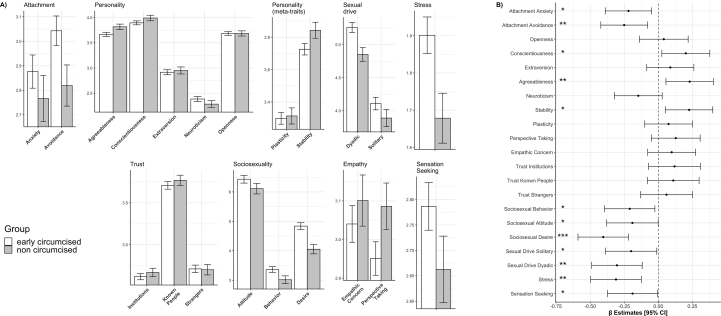

Circumcision status showed an effect on attachment style (F2,602 = 4.77, p = .009, η2p = .016). Specifically, between-subjects effects analysis indicated that EC participants reported higher levels of avoidance and anxiety compared to the NC sample. No multivariate effect was found regarding the Big Five personality traits (F5,599 = 1.66, p = .141, η2p = .014). The two personality meta-traits yielded a multivariate effect (F2,602 = 3.29, p = .038, η2p = .011), suggesting that EC men scored lower in emotional stability but not in plasticity. No multivariate effects were found for empathy (F2,599 = 1.07, p = .344, η2p = .004) or trust (F3,518 = 0.64, p = .491, η2p = .004). An effect of circumcision status was detected on sociosexuality (F3,518 = 6.29, p < .0001, η2p = .035), with EC men reporting higher levels of sociosexual desire, sociosexual behavior, and sociosexual attitude. A multivariate effect on sexual libido was found (F2,519 = 5.82, p = .003, η2p = .022), with EC men scoring higher in solitary and dyadic dimensions. Lastly, compared to NC, EC men reported higher levels of both stress (F1,521 = 10.76, p = .001, η2p = .020), and sensation seeking (F1,550 = 4.08, p = .043, η2p = .007). Univariate results are reported in Table 2 and displayed in Figure 1 before (left) and after (right) correcting for age, ethnicity, and relationship status. A correlation matrix for all the study's variables is presented in supplementary material SM3.

Table 2.

Univariate results. Differences between groups with age, ethnicity, and relationship status as covariates. Negative estimates (b with standard error) indicate lower scores in the non-circumcised group. As measures of effect size and model fitness, partial eta squared (η2p, with 95% CI) and R squared (R2) are reported. df: degrees of freedom.

| Psychological construct | scale | Range | b | St. Err | F value | df | p | η2p | η2p 95% CI | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment | Anxiety | 1–7 | -.299 | 0.118 | 6.44 | 603 | .011 | .011 | [0.001, 0.032] | .109 |

| Avoidance | 1–7 | -.306 | 0.107 | 8.22 | 603 | .004 | .013 | [0.001, 0.037] | .092 | |

| Personality | Openness | 1–5 | .030 | 0.067 | 0.19 | 603 | .660 | .000 | [0.000, 0.009] | .019 |

| Conscientiousness | 1–5 | .160 | 0.071 | 5.06 | 603 | .025 | .008 | [0.000, 0.028] | .046 | |

| Extraversion | 1–5 | .088 | 0.089 | 0.99 | 604 | .321 | .002 | [0.000, 0.014] | .070 | |

| Agreeableness | 1–5 | .180 | 0.069 | 6.72 | 603 | .010 | .011 | [0.001, 0.033] | .065 | |

| Neuroticism | 1–5 | -.143 | 0.087 | 2.72 | 603 | .100 | .004 | [0.000, 0.021] | .051 | |

| Stability | 0–5 | .161 | 0.063 | 6.49 | 603 | .011 | .011 | [0.001, 0.033] | .065 | |

| Plasticity | 0–5 | .054 | 0.064 | 0.70 | 604 | .402 | .001 | [0.000, 0.013] | .045 | |

| Empathy | Perspective taking | 1–5 | .112 | 0.080 | 1.97 | 600 | .161 | .003 | [0.000, 0.018] | .018 |

| Empathic concern | 1–5 | .093 | 0.085 | 1.19 | 600 | .275 | .002 | [0.000, 0.015] | .057 | |

| Trust | Towards institutions | 1–5 | .081 | 0.067 | 1.50 | 520 | .222 | .003 | [0.000, 0.019] | .017 |

| Towards known people | 1–5 | .092 | 0.081 | 1.29 | 520 | .256 | .002 | [0.000, 0.018] | .022 | |

| Towards strangers | 1–5 | .051 | 0.082 | 0.38 | 520 | .536 | .001 | [0.000, 0.012] | .022 | |

| Sociosexuality | Behavior | 1–9 | -.377 | 0.168 | 5.00 | 520 | .026 | .010 | [0.000, 0.033] | .074 |

| Attitude | 1–9 | -.465 | 0.235 | 3.91 | 520 | .049 | .007 | [0.000, 0.029] | .028 | |

| Desire | 0–9 | -.894 | 0.208 | 18.44 | 520 | .000 | .034 | [0.010, 0.070] | .073 | |

| Sexual libido | Solitary | 0–8 | -.354 | 0.170 | 4.33 | 520 | .038 | .008 | [0.000, 0.030] | .039 |

| Dyadic | 0–8 | -.430 | 0.133 | 10.39 | 520 | .001 | .020 | [0.003, 0.049] | .069 | |

| Stress | Stress | 0–5 | -.286 | 0.087 | 10.76 | 521 | .001 | .020 | [0.003, 0.050] | .055 |

| Sensation seeking | Sensation seeking | 1–5 | -.171 | 0.085 | 4.08 | 550 | .044 | .007 | [0.000, 0.028] | .037 |

Figure 1.

Left (A): raw group means (error bars: standard error of the mean) in psychological constructs for each group (early-circumcised and non-circumcised men). Right (B): estimated mean difference (standardized coefficients beta estimates, error bars: 95% CI) between group after correcting for age, ethnicity, and relationship status. Positive beta estimates indicate higher scores in the non-circumcised group; ∗p < .05; ∗∗ <.01; ∗∗∗<.001.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the possible long-term impact of neonatal circumcision on adult psychosocial outcomes. Unlike other studies that relied on mixed early- and late-circumcised men (Bollinger and Van Howe, 2011; Frisch and Simonsen, 2015a; Ullmann et al., 2017), here we specifically focused on the adult psychological profile of self-reported early-circumcised (within a month) men compared to non-circumcised. We hypothesized that early-circumcised men, compared to men who did not undergo neonatal circumcision, would display an alteration in socio-affective processing, characterized by higher attachment insecurity and emotional instability, lower empathy and trust, higher sexual libido and unrestricted sociosexuality (i.e., high number of sexual partners), and higher stress and risk-taking attitudes. Although all the associations that we found are in the direction of our hypothesis, contrary to our expectations, neither empathy nor trust were found to be affected by early circumcision. This being noted, our results are consistent with the view that neonatal circumcision has a long-term impact on adult behavior. Our findings are in line with research showing that neonatal circumcision affects parent-infant attachment. This is in accordance with life-history theory, which stipulates that early-life stress reduces reliance on one's social environment (e.g., opportunistic-exploitative interpersonal orientation), increasing stress, heightening sexuality, and increasing short-term mating and externalizing behaviors (Del Giudice, 2016; Del Giudice et al., 2005; Shakiba et al., 2020).

Although some studies have found that post-circumcision mother-infant bonding is disrupted, marked by altered breastfeeding and sleep patterns as well as higher infant irritability (Dixon et al., 1984; Marshall et al., 1980, 1982; Richards et al., 1976), other studies do not (Fergusson et al., 2007; Gattari et al., 2013; Mondzelewski et al., 2016). In this study, we found that EC men exhibited more anxious and avoidant attachment. For decades, investigators have advanced the view that the precursors of insecure attachment were lying in separation from, or inconsistent treatment by, primary caregivers in early life (Cassidy et al., 2013). Early attachment, crucial for the infant's neurobiological development (Schore, 2001), impacts both development and adult behavior (Bowlby, 1979). Longitudinal studies show that in six-month old infants, the quality of the mother-infant interaction predicted attachment security (Britton et al., 2006; measured with the Ainsworth et al. (1978) Strange Situation test). Also, early attachment security at 12 months has been found to predict the experience and expression of emotions at elementary school, at adolescence, and in the mid-twenties (Simpson et al., 2007). Moreover, early attachment security was found linked, 30 years later, to lower neuroticism and higher conscientiousness and agreeableness (Young et al., 2017), which, when aggregated, constitute the meta-trait stability (DeYoung et al., 2002). Consistent with longitudinal studies, we can preliminarily —but cautiously— link the adult attachment style of EC men with developmental factors, prompting more research to support this finding.

Our results showed that EC, compared to NC, men scored lower in emotional stability, a meta-trait of the Big Five composed of conscientiousness, agreeableness, and neuroticism (reversed). Low emotional stability has been linked to impaired functioning in emotional, motivational, and social domains (DeYoung et al., 2002, 2008). Several studies have linked insecure attachment and emotional instability to the rise of externalizing behaviors (e.g., aggression, hostility, impulsivity, antisocial behavior, hyperactivity, and drug abuse) and psychopathology (DeYoung et al., 2008; Green and Goldwyn, 2002; Paetzold et al., 2015). Interestingly, preterm children who have spent early days in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) have persistently altered cortisol levels (Grunau et al., 2005, 2007) and altered breastfeeding patterns (Dodrill et al., 2008; Flacking et al., 2003; Maastrup et al., 2014) along with changed mother-infant interactions (Feldman, 2006), and are at higher risk of developing externalizing behaviors (Bhutta et al., 2002). This may be due in part to the invasive and painful, but life-saving, procedures performed in the NICU that affect structural brain development (Brummelte et al., 2012; Smyser et al., 2010), thereby having a long-term impact. These findings, together with our own results, suggest that neonatal circumcision may foster the development of attachment-related changes with implications for adult psychology or behavior.

We also found that early circumcision was associated with increased libido and sociosexual behavior. Studies on early stress show that precocious sexuality and unstable pair bonding are associated with insecure attachment (Belsky et al., 1991, 2012; Sung et al., 2016), and that individuals low in emotional stability are less likely to maintain stable relationships (Young et al., 2017), hence scoring high in sociosexuality. We found that the EC group also scored higher in sensation seeking. Sensation seeking is a potent predictor of a wide array of behaviors such as sexual risk-taking, reckless driving, smoking, alcohol use, and use of illicit drugs (Hoyle et al., 2002). The associations between sensation seeking, risk taking, and sociosexuality have been well established (Birnbaum, 2016; Penke and Asendorpf, 2008; Seal and Agostinelli, 1994; Simpson et al., 2004). Insecure individuals are more likely to have sex because of fear of abandonment and therefore to engage in sexual contact as an instrumental way of gaining reassurance (Birnbaum, 2016). Because risk taking often involves unprotected sex (Simpson et al., 2004), this suggests that unrestricted individuals who score high in sensation seeking might be at greater risk for contracting and spreading sexually transmitted diseases.

In our study, EC men reported higher levels of perceived stress compared to NC men. This is in contrast with one study that failed to reject the null hypothesis that circumcision alters neither psychological nor endocrine measures of stress (Ullmann et al., 2017). Yet, that study had insufficient statistical power (Boyle, 2017) to detect statistically significant differences between the groups (11 non-circumcised and 9 circumcised men, of whom 6 were circumcised with anesthesia and 3 were circumcised in infancy). Here, not only did we detect a statistically significant effect of perceived stress using a well-powered sample, but we have also provided theoretical reasons to link such stress in EC men to developmental factors. Because our EC sample was higher in attachment anxiety and emotional instability, this population may be less able to use secure-based strategies of social support-seeking that may lead them to use less effective means of social resources to cope with stress (Ein-Dor et al., 2018).

Although trust is a crucial part of a secure attachment (Joireman et al., 2002; Mikulincer, 1998; Rodriguez et al., 2015), contrary to our expectations, we did not find an effect of early circumcision on trust. While individuals with a secure attachment style tend to be confident, trust intimacy, and develop closeness, individuals with an insecure attachment style have difficulties in trusting and depending on others (avoidant style) or view others as undependable and untrustworthy (anxious style; Bogaert and Sadava, 2002). Our failure to detect an effect of circumcision on empathy should be noted. Exploratory work suggests a link between circumcision (192 neonatally circumcised and 44 later in life) and alexithymia (Bollinger and Van Howe, 2011) and between circumcision and a greater risk of developing ASD (Bauer and Kriebel, 2013; Frisch and Simonsen, 2015a), which, in turn, is associated with alexithymia (Berthoz and Hill, 2005; Frith, 2004; Hill et al., 2004). Studies on premature infants, who undergo invasive painful procedures in the NICU, have found that neonatal pain exposure was associated with reduced subcortical gray matter and reduced white matter in frontal and parietal regions (Brummelte et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2011), structures associated with empathic processing (Bernhardt and Singer, 2012; Decety and Jackson, 2004). Studies consistently show that alexithymia and empathy scores correlate significantly (Banzhaf et al., 2018; Moriguchi et al., 2006), even when controlling for anxiety and depressive symptoms (Grynberg et al., 2010). We did however find that EC men scored lower than NC men in all measures of empathy and trust, despite the associated p value being greater than the pre-determined alpha level. We also report that these two constructs correlate negatively with both attachment avoidance and anxiety, replicating the findings of previous literature (Joireman et al., 2002; Rodriguez et al., 2015). Nevertheless, we report that the effect of circumcision on empathy and trust is negligible, at least in our sample.

4.1. Potential epidemiological implications

The psychological differences that we found between EC and NC men are not sufficiently severe in themselves to be suggestive of pathology. However, at the population level, where more than a half of US neonates undergo circumcision and 70–80% of US adult men have undergone early circumcision (AAP, 2012; Maeda et al., 2012; Morris et al., 2016), even small individual-level effects on psychosocial functioning may have meaningful cumulative implications. As discussed above, early-circumcision (similar to other neonatal surgical procedures, DeYoung et al., 2008; Green and Goldwyn, 2002; Paetzold et al., 2015) might be a concomitant factor for the emergence of such externalizing behaviors, especially in low socioeconomic contexts (Dodge et al., 1994). The present study did not explicitly examine externalizing behavior so we cannot test this hypothesis but recommend this analysis in future research, perhaps comparing EC boys/men with those born preterm who experienced early days in the NICU.

We found that EC, compared to NC, men reported higher sexual libido and sociosexual behavior. Assuming reasonably accurate self-reporting, EC men in our sample may therefore be more likely to engage in more sex with more partners than the NC men in our sample. Some surveys indicate that circumcised men are less likely to wear a condom when engaging in heterosexual (but not homosexual, Mao et al., 2008) penetrative intercourse (Chikutsa and Maharaj, 2015; Crosby and Charnigo, 2013), that unrestricted individuals are more likely to engage in unprotected risky sexual intercourse (Seal and Agostinelli, 1994), and that individuals high in risk taking often engage in unprotected sex (Simpson et al., 2004). Overall, this might suggest an increased likelihood among EC men who score high in sociosexuality and risk-taking to spread sexually transmitted diseases; but more direct research on this question must be undertaken. We note that prior research suggesting a protective effect of circumcision on, e.g., transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV, female-to-male transmission only) concerned adult, voluntary circumcision later in life, not EC as explored in our study.

4.2. Limitations

Although our study provides potentially valuable information about the long-term psychological effects of neonatal circumcision, the results obtained should be tempered with an understanding of its limitations. Above all, we did not collect sociodemographic data such as religious affiliation and socioeconomic status that could have played a role in parent-infant relationships hence affecting attachment development. Our data is self-reported, and studies of this type are known to suffer from social desirability bias for sensitive topics, and low accuracy in self-assessment of circumcision status (at least in adolescents, Risser et al., 2004). Social desirability might have hindered participants from answering honestly on scales related to constructs known to be socially desirable (e.g., empathy, Watson and Morris, 1991). Although such a bias would be a systematic confound present in both EC and NC groups, we urge that future studies do not rely solely on self-reported questionnaires, or, at least, attempt to correct for social desirability bias.

MTurk populations, like ours, when compared to the US population as a whole, tend to be younger and more educated, but report lower incomes and higher unemployment (Stewart et al., 2017). Therefore, future studies need to be repeated with a sample of people that is more representative of the population and collect more sociodemographic variables to allow comparisons. To this end, we have provided a thorough description of our sample(s) in terms of demographic characteristics (see Table 1 and Figure 2) and provided complete statistics for our scales and results (SM2, SM3, and Table 2). It should be noted that our population was comparable to larger samples in terms of within-ethnicity proportion of circumcised men. Risser et al. (2004) investigated the circumcision status of 1508 adolescents (mean age in 2002 was 15 years) and reported that 58% of men within Black or African American, 22% men within Hispanic or Latino/a, and 82% men within White ethnic groups were circumcised. Similarly, we report that 61%, 27%, and 74% of men, within the same ethnic groups respectively, reported being early-circumcised. Moreover, our sample also shows a decreasing proportion of neonatal circumcision over the decades (see Figure 2), which has been shown in census data (Laumann et al., 1997; Wiswell et al., 1987, but see Morris et al., 2016). Another limitation is that our sample is composed of only US Americans. While this might pose a problem in terms of generalizability beyond this population, it is however a strength that, in the US, religion is less of a confounding factor with respect to circumcision, compared to samples drawn from European populations.

5. Conclusions

As a painful skin-breaking procedure, neonatal circumcision alters infant physiological and behavioral stress responses. Prolonged stress may have an effect on mother infant interactions and the development of an insecure attachment style. Here, we explored whether neonatal circumcision was connected with adult socio-affective processing associated with early stress. Our analysis shows differences between early-circumcised and non-circumcised men in psychological measures of socio-affectivity and provides initial support for the hypothesis that this alteration stems from the most crucial neurodevelopmentally plastic period of an individual's life. On a global scale, these small alterations might have meaningful social implications. Although we have used validated psychological instruments and provided a rich set of descriptive statistics that facilitate comparison to other studies, a replication of the current study with a larger sample size and better ability to control for socioeconomic variables is warranted. Longitudinal case-control studies from birth using the validated Ainsworth Strange Situation test to measure infant attachment would provide additional insights into how developmental history affects adult behaviors following neonatal circumcision.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

A. Miani: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

G. A. Di Bernardo: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

A. D. Højgaard, P. J. Zak, A. Landau: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

B. D. Earp: Wrote the paper.

J. Hoppe, M. Winterdahl: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the RegionMidt Research Foundation and the Institute of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University.

Data availability statement

Data associated with this study has been deposited at https://osf.io/znhp8/?view_only=a95c7e6d7de34facb9c043d2c9953ced.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- AAP Prevention and management of procedural pain in the neonate: an update. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AAP Male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e756–e785. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulcadir J., Adler P.W., Alderson P., Alexander S., Aurenque D., Bader D., Ben-Yami H., Bewley S., Boddy J., van den Brink M., Bronselaer G., Burrage H., Ceelen W., Chambers C., Chegwidden J., Coene G., Conroy R., Dabbagh H., Davis D.S., Dawson A., Decruyenaere J., Dekkers W., Delaet D., De Sutter P., van Dijk G., Dubuc E., Dworkin G., Earp B.D., Baky Fahmy M.A., Ferreira N., Florquin S., Frisch M., Garland F., Goldman R., Gruenbaum E., Heinrichs G., Herbenick D., Higashi Y., Ho C.W.L., Hoebeke P., Johnson M., Johnson-Agbakwu C., Karlsen S., Kim D., Kling S., Komba E., Kraus C., Kukla R., Lempert A., von Gleichen T.L., Macdonald N., Merli C., Mishori R., Möller K., Monro S., Moodley K., Mortier E., Munzer S.R., Murphy T.F., Nelson J.L., Ncayiyana D.J., van Niekerk A.A., O’neill S., Onuki D., Palacios-González C., Pang M.G., Proudman C.R., Richard F., Richards J.R., Reis E., Rotta A.T., Rubens R., Sarajlic E., Sardi L., Schüklenk U., Shahvisi A., Shaw D., Sidler D., Steinfeld R., Sterckx S., Svoboda J.S., Tangwa G.B., Thomson M., Tigchelaar J., Van Biesen W., Vandewoude K., Van Howe R.S., Vash-Margita A., Vissandjée B., Wahlberg A., Warren N. Medically unnecessary genital cutting and the rights of the child: moving toward consensus. Am. J. Bioeth. 2019 doi: 10.1080/15265161.2019.1643945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe J.A.A., Izard C.E. A longitudinal study of emotion expression and personality relations in early development. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999;77:566–577. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.3.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth M.D.S., Blehar M.C., Waters E., Wall S.N. Psychology Press; 1978. Patterns of Attachment, Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. [Google Scholar]

- Anand K.S., Aynsley-Green A., Bancalari E., Benini F., Champion G.D., Craig K.D., Dangel T.S., Fournier-Charrière E., Franck L.S., Grunau R.E., Hertel S.A., Jacqz-Aigrain E., Jorch G., Kopelman B.I., Koren G., Larsson B., Marlow N., McIntosh N., Ohlsson A., Olsson G., Porter F., Richter R., Stevens B., Taddio A. Consensus statement for the prevention and management of pain in the newborn. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2001 doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banieghbal B. Optimal time for neonatal circumcision: an observation-based study. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2009;5:359–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banzhaf C., Hoffmann F., Kanske P., Fan Y., Walter H., Spengler S., Schreiter S., Singer T., Bermpohl F. Interacting and dissociable effects of alexithymia and depression on empathy. Psychiatr. Res. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A.Z., Kriebel D. Prenatal and perinatal analgesic exposure and autism: an ecological link. Environ. Health. 2013;12:41. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-12-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J., Schlomer G.L., Ellis B.J. Beyond cumulative risk: distinguishing harshness and unpredictability as determinants of parenting and early life history strategy. Dev. Psychol. 2012;48:662–673. doi: 10.1037/a0024454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J., Steinberg L., Draper P. Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: an evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Dev. 1991;62(4) doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benatar M., Benatar D. Between prophylaxis and child abuse: the ethics of neonatal male circumcision. Am. J. Bioeth. 2003;3(2) doi: 10.1162/152651603766436216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt B.C., Singer T. The neural basis of empathy. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;35(1):1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoz S., Hill E.L. The validity of using self-reports to assess emotion regulation abilities in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Eur. Psychiatr. 2005;20(3) doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta A.T., Cleves M.A., Casey P.H., Cradock M.M., Anand K.S. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002;288(6):728. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum G.E. Handbook of Attachment. third ed. Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2016. Attachment and sexual mating: the joint operation of separate motivational systems; pp. 464–483. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert A.F., Sadava S. Adult attachment and sexual behavior. Pers. Relat. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Bollinger D., Van Howe R.S. Preliminary results are preliminary, not “unfounded”: reply to Morris and waskett. Int. J. Men’s Health. 2012;11(2) [Google Scholar]

- Bollinger D., Van Howe R.S. Alexithymia and circumcision trauma: a preliminary investigation. Int. J. Men’s Health. 2011;10(2):184–195. [Google Scholar]

- Bossio J.A., Pukall C.F. Attitude toward one’s circumcision status is more important than actual circumcision status for men’s body image and sexual functioning. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2018;47(3) doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-1064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossio J.A., Pukall C.F., Steele S. A review of the current state of the male circumcision literature. J. Sex. Med. 2014;11(12):2847–2864. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossio J.A., Pukall C.F., Steele S.S. Examining penile sensitivity in neonatally circumcised and intact men using quantitative sensory testing. J. Urol. 2016;195:1848–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Tavistock; London, UK: 1979. The Making and Breaking of Affectional Bonds. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle G. Proving a negative? Methodological, statistical, and psychometric flaws in Ullmann et al. (2017) PTSD study. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2017 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle G.J. Does male circumcision adversely affect sexual sensation, function, or satisfaction? Critical comment on Morris and krieger. Adv. Sex. Med. 2015;5:7–12. (2013) [Google Scholar]

- Brady-Fryer B., Wiebe N., Lander J.A. Pain relief for neonatal circumcision. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2004;CD004217 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004217.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton J.R., Britton H.L., Gronwaldt V. Breastfeeding, sensitivity, and attachment. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):e1436–e1443. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelte S., Grunau R.E., Chau V., Poskitt K.J., Brant R., Vinall J., Gover A., Synnes A.R., Miller S.P. Procedural pain and brain development in premature newborns. Ann. Neurol. 2012;71(3):385–396. doi: 10.1002/ana.22267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J., Jones J.D., Shaver P.R. Contributions of attachment theory and research: a framework for future research, translation, and policy. Dev. Psychopathol. 2013;25:1415–1434. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler J., Shapiro D. Conducting clinical research using crowdsourced convenience samples. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2016;12(1):53–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikutsa A., Maharaj P. Social representations of male circumcision as prophylaxis against HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe. BMC Publ. Health. 2015;15:603. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1967-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Williamson G.M. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S., Oskaap S., editors. The Social Psychology of Health. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, McCrae R.R. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. Neo PI-R Professional Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby R., Charnigo R.J. A comparison of condom use perceptions and behaviours between circumcised and intact men attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in the United States. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2013;24:175–178. doi: 10.1177/0956462412472444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby R. Risks, benefits, complications and harms: neglected factors in the current debate on non-therapeutic circumcision. Kennedy Inst. Ethics J. 2015;25(1) doi: 10.1353/ken.2015.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave S., Afshar K., Braga L.H., Anderson P. CUA guideline on the care of the normal foreskin and neonatal circumcision in Canadian infants. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2018;12(2) doi: 10.5489/cuaj.5034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.H. Interpersonal reactivity Index. JSAS cat. Sel. Doc. Psychol. 1980;10:14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Decety J., Jackson P.L. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav. Cognit. Neurosci. Rev. 2004;3(2):71–100. doi: 10.1177/1534582304267187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice M. Sex differences in romantic attachment: a facet-level analysis. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2016;88:125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice M., Gangestad S., Kaplan H.S. Life history theory and evolutionary psychology. Handb. Evol. Psychol. 2005:68–95. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung C.G., Peterson J.B., Higgins D.M. Higher-order factors of the Big Five predict conformity: are there neuroses of health? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2002;33(4):533–552. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung C.G., Peterson J.B., Séguin J.R., Tremblay R.E. Externalizing behavior and the higher order factors of the Big Five. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2008;117(4):947–953. doi: 10.1037/a0013742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon S., Snyder J., Holve R., Bromberger P. Behavioral effects of circumcision with and without anesthesia. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 1984;5(5):246–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge K.A., Pettit G.S., Bates J.E. Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Dev. 1994;65(2):649–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodrill P., Donovan T., Cleghorn G., McMahon S., Davies P.S.W. Attainment of early feeding milestones in preterm neonates. J. Perinatol. 2008;28(8):549–555. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earp B.D. Infant circumcision and adult penile sensitivity: implications for sexual experience. Trends Urol. Men’s Health. 2016;7(4) [Google Scholar]

- Earp B.D. The ethics of infant male circumcision. J. Med. Ethics. 2013;39(7):418–420. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2013-101517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earp B.D., Sardi L.M., Jellison W.A. Cult. Heal. Sex; 2018. False Beliefs Predict Increased Circumcision Satisfaction in a Sample of US American Men. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ein-Dor T., Verbeke W.J.M.I., Mokry M., Vrtička P. Epigenetic modification of the oxytocin and glucocorticoid receptor genes is linked to attachment avoidance in young adults. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2018;20(4):1–16. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2018.1446451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhaik E. Neonatal circumcision and prematurity are associated with sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2018;4(2):136–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy M.A.B. Complications in Male Circumcision. Elsevier; 2019. Prevalence of male circumcision complications; pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R. From biological rhythms to social rhythms: physiological precursors of mother-infant synchrony. Dev. Psychol. 2006;42(1):175–188. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D.M., Boden J.M., Horwood L.J. Neonatal circumcision: effects on breastfeeding and outcomes associated with breastfeeding. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2007;44 doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flacking R., Nyqvist K.H., Ewald U., Wallin L. Long-term duration of breastfeeding in Swedish low birth weight infants. J. Hum. Lactation. 2003;19(2):157–165. doi: 10.1177/0890334403252563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J., Weisberg S., Adler D., Bates D.M., Baud-Bovy G., Ellison S., Firth D., Friendly M., Gorjanc G., Graves S., Heiberger R., Laboissiere R., Mon G., Murdoch D., Nilsson H., Ogle D., Ripley B., Venables W., Zeileis A., R-Core . second ed. R Top. Doc; 2014. An R Companion to Applied Regression. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley R.C., Waller N.G., Brennan K.A. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000;78(2):350–365. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman A.L. The circumcision debate: beyond benefits and risks. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M., Aigrain Y., Barauskas V., Bjarnason R., Boddy S.-A., Czauderna P., de Gier R.P.E., de Jong T.P.V.M., Fasching G., Fetter W., Gahr M., Graugaard C., Greisen G., Gunnarsdottir A., Hartmann W., Havranek P., Hitchcock R., Huddart S., Janson S., Jaszczak P., Kupferschmid C., Lahdes-Vasama T., Lindahl H., MacDonald N., Markestad T., Martson M., Nordhov S.M., Palve H., Petersons A., Quinn F., Qvist N., Rosmundsson T., Saxen H., Soder O., Stehr M., von Loewenich V.C.H., Wallander J., Wijnen R. Cultural bias in the AAP’s 2012 technical report and policy statement on male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):796–800. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M., Earp B.D. Circumcision of male infants and children as a public health measure in developed countries: a critical assessment of recent evidence. Global Publ. Health. 2018;13(5) doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1184292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M., Simonsen J. Ritual circumcision and risk of autism spectrum disorder in 0- to 9-year-old boys: national cohort study in Denmark. J. R. Soc. Med. 2015;108(7):1–14. doi: 10.1177/0141076814565942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M., Simonsen J. Circumcision-autism link needs thorough evaluation: response to Morris and Wiswell. J. R. Soc. Med. 2015;108(8) doi: 10.1177/0141076815593048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith U. Emanuel miller lecture: confusions and controversies about asperger syndrome. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2004;45(4):672–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattari T.B., Bedway A.R., Drongowski R., Wright K., Keefer P., Mychaliska K.P. Neonatal circumcision: is feeding behavior altered? Hosp. Pediatr. 2013;3(4):362–365. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2012-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goksan S., Hartley C., Emery F., Cockrill N., Poorun R., Moultrie F., Rogers R., Campbell J., Sanders M., Adams E., Clare S., Jenkinson M., Tracey I., Slater R. fMRI reveals neural activity overlap between adult and infant pain. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.06356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J., Goldwyn R. Annotation: attachment disorganisation and psychopathology: new findings in attachment research and their potential implications for developmental psychopathology in childhood. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2002;43(2):835–846. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau R.E., Haley D.W., Whitfield M.F., Weinberg J., Yu W., Thiessen P. Altered basal cortisol levels at 3, 6, 8 and 18 Months in infants born at extremely low gestational age. J. Pediatr. 2007;150(2):151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau R.E., Haley D.W., Oberlander T., Weinberg J., Solimano A., Whitfield M.F., Fitzgerald C., Yu W. Neonatal procedural pain exposure predicts lower cortisol and behavioral reactivity in preterm infants in the NICU. Pain. 2005;113(3):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynberg D., Luminet O., Corneille O., Grèzes J., Berthoz S. Alexithymia in the interpersonal domain: a general deficit of empathy? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2010;49(8) [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M.R., Fisch R.O., Korsvik S., Donhowe J.M. The effects of circumcision on serum cortisol and behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1981;6(3):269–275. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(81)90037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M.R., Porter F.L., Wolf C.M., Rigatuso J., Larson M.C. Neonatal stress reactivity: predictions to later emotional temperament. Child Dev. 1995;66(1):1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond T., Carmack A. Long-term adverse outcomes from neonatal circumcision reported in a survey of 1,008 men: an overview of health and human rights implications. Int. J. Hum. Right. 2017;21(2):189–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hill E., Berthoz S., Frith U. Brief report: cognitive processing of own emotions in individuals with autistic spectrum disorder and in their relatives. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004;34(2):229–235. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000022613.41399.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmeister J., Kroll A., Wollgarten-Hadamek I., Zohsel K., Demirakça S., Flor H., Hermann C. Cerebral processing of pain in school-aged children with neonatal nociceptive input: an exploratory fMRI study. Pain. 2010;150(2):257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard C.R., Howard F.M., Garfunkel L.C., De Blieck E.A., Weitzman M. Neonatal circumcision and pain relief: current training practices. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3) doi: 10.1542/peds.101.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle R.H., Stephenson M.T., Palmgreen P., Lorch E.P., Donohew R.L. Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2002;32(3):401–414. [Google Scholar]

- Joireman J.A., Needham T.L., Cummings A.-L. Relationships between dimensions of attachment and empathy. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2002;4(1):63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Krill A.J., Palmer L.S., Palmer J.S. Complications of circumcision. Sci. World J. 2011;11:2458–2468. doi: 10.1100/2011/373829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann E.O., Ezra W., Zuckerman E.O. Circumcision in the United States. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1997;277(13):1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litman L., Robinson J., Abberbock T. TurkPrime.com: a versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 2017;49(2):433–442. doi: 10.3758/s13428-016-0727-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litman L., Robinson J., Rosenzweig C. The relationship between motivation, monetary compensation, and data quality among US- and India-based workers on Mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods. 2015;47(2):519–528. doi: 10.3758/s13428-014-0483-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maastrup R., Hansen B.M., Kronborg H., Bojesen S.N., Hallum K., Frandsen A., Kyhnaeb A., Svarer I., Hallström I. Breastfeeding progression in preterm infants is influenced by factors in infants, mothers and clinical practice: the results of a national cohort study with high breastfeeding initiation rates. PloS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machmouchi M., Alkhotani A. Is neonatal circumcision judicious? Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2007;17(4) doi: 10.1055/s-2007-965417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda J.L., Chari R., Elixhauser A. Circumcisions performed in U.S. Community hospitals, 2009. HCUP stat. Br. #126. Agency Healthc. Res. Qual. Rockville, MD. 2012:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L., Templeton D.J., Crawford J., Imrie J., Prestage G.P., Grulich A.E., Donovan B., Kaldor J.M., Kippax S.C. Does circumcision make a difference to the sexual experience of gay men? Findings from the health in men (HIM) cohort. J. Sex. Med. 2008;5(11):2557–2561. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall R.E., Porter F.L., Rogers A.G., Moore J., Anderson B., Boxerman S.B. Circumcision: II. Effects upon mother-infant interaction. Early Hum. Dev. 1982;7(4):367–374. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(82)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall R.E., Stratton W.C., Moore J.A., Et A. Circumcision I: Effects upon newborn behavior. Early Hum. Dev. 1980;3:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M. Attachment working models and the sense of trust: an exploration of interaction goals and affect regulation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998;74(5) [Google Scholar]

- Mondzelewski L., Gahagan S., Johnson C., Madanat H., Rhee K. Timing of circumcision and breastfeeding initiation among newborn boys. Hosp. Pediatr. 2016;6(11):653–658. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi Y., Ohnishi T., Lane R.D., Maeda M., Mori T., Nemoto K., Matsuda H., Komaki G. Impaired self-awareness and theory of mind: an fMRI study of mentalizing in alexithymia. Neuroimage. 2006;32(3) doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.04.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris B.J., Krieger J.N. Male circumcision does not reduce sexual function, sensitivity or satisfaction. Adv. Sex. Med. 2015;5(3):53–60. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris B.J., Wamai R.G., Henebeng E.B., Tobian A.A.R., Klausner J.D., Banerjee J., Hankins C.A. Estimation of country-specific and global prevalence of male circumcision. Popul. Health Metrics. 2016;14(1) doi: 10.1186/s12963-016-0073-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris B.J., Waskett J.H., Bollinger D., Van Howe R.S. Claims that circumcision increases alexithymia and erectile dysfunction are unfounded: a critique of bollinger and van howe’s “alexithymia and circumcision trauma: a preliminary investigation. Int. J. Men’s Health. 2012;11(2):177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Morris B.J., Wiswell T.E. “Circumcision pain” unlikely to cause autism. J. R. Soc. Med. 2015;108(8):297. doi: 10.1177/0141076815590404. 297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers A., Earp B.D. What is the best age to circumcise? A medical and ethical analysis. Bioeth. 2020;34(7) doi: 10.1111/bioe.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naef M., Schupp J. Measuring trust: experiments and surveys in contrast and combination. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2009;(4087) Pap. 4087. [Google Scholar]

- Paetzold R.L., Rholes W.S., Kohn J.L. Disorganized attachment in adulthood: theory, measurement, and implications for romantic relationships. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2015;19(2):146–156. [Google Scholar]

- Page G.G. Are there long-term consequences of pain in newborn or very young infants? J. Perinat. Educ. 2004;13(3):10–17. doi: 10.1624/105812404X1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penke L., Asendorpf J.B. Beyond global sociosexual orientations: a more differentiated look at sociosexuality and its effects on courtship and romantic relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008;95(5):1113–1135. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Revelle W. R Packag; 2015. Package “Psych” - Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric and Personality Research. [Google Scholar]

- Richards M.P.M., Bernal J.F., Brackbill Y. Early behavioral differences: gender or circumcision? Dev. Psychobiol. 1976;9(1) doi: 10.1002/dev.420090112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risser J.M.H., Risser W.L., Eissa M.A., Cromwell P.F., Barratt M.S., Bortot A. Self-assessment of circumcision status by adolescents. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004;159(11) doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez L.M., DiBello A.M., Øverup C.S., Neighbors C. The price of distrust: trust, anxious attachment, jealousy, and partner abuse. Partner Abuse. 2015;6 doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.6.3.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzle-Lubiecki B.M., Campbell K.A.A., Howard R.H., Franck L., Fitzgerald M. Long-term consequences of early infant injury and trauma upon somatosensory processing. Eur. J. Pain. 2007;11(7) doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schore A.N. The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Ment. Health J. 2001;22:201–269. [Google Scholar]

- Seal D.W., Agostinelli G. Individual differences associated with high-risk sexual behaviour: implications for intervention programmes. AIDS Care. 1994;6(4) doi: 10.1080/09540129408258653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakiba N., Conradt E., Ellis B.J. Biological sensitivity to context. In: Harkness K.L., Hayden E.P., editors. The Oxford Handbook of Stress and Mental Health. Oxford University Press; 2020. pp. 600–624. [Google Scholar]

- Simons S.H.P., van Dijk M., Anand K.S., Roofthooft D., van Lingen R.A., Tibboel D. Do we still hurt newborn babies? Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2003;157(11):1058. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.11.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J.A., Collins W.A., Tran S., Haydon K.C. Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in romantic relationships: a developmental perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007;92(2):355–367. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J.A., Wilson C.L., Winterheld H.A. Sociosexuality and romantic relationships. Handb. Sex. Close Relation. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Sinkey R.G., Eschenbacher M.A., Walsh P.M., Doerger R.G., Lambers D.S., Sibai B.M., Habli M.A. The GoMo study: a randomized clinical trial assessing neonatal pain with Gomco vs Mogen clamp circumcision. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;212(5):664.e1–664.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G.C., Gutovich J., Smyser C., Pineda R., Newnham C., Tjoeng T.H., Vavasseur C., Wallendorf M., Neil J., Inder T. Neonatal intensive care unit stress is associated with brain development in preterm infants. Ann. Neurol. 2011;70(4):541–549. doi: 10.1002/ana.22545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyser C.D., Inder T.E., Shimony J.S., Hill J.E., Degnan A.J., Snyder A.Z., Neil J.J. Longitudinal analysis of neural network development in preterm infants. Cerebr. Cortex. 2010;20(12):2852–2862. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector I.P., Carey M.P., Steinberg L. The sexual desire inventory: development, factor structure, and evidence of reliability. J. Sex Marital Ther. 1996;22(3):175–190. doi: 10.1080/00926239608414655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart N., Chandler J., Paolacci G. Crowdsourcing samples in cognitive science. Trends Cognit. Sci. 2017;21(10):736–748. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung S., Simpson J.A., Griskevicius V., Sally I., Kuo C., Schlomer G.L., Belsky J., Kuo S.I.-C., Schlomer G.L., Belsky J. Secure infant-mother attachment buffers the effect of early-life stress on age of menarche. Psychol. Sci. 2016;27(5):667–674. doi: 10.1177/0956797616631958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda J.S., Van Howe R.S. Out of step: fatal flaws in the latest AAP policy report on neonatal circumcision. J. Med. Ethics. 2013;39(7):434–441. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2013-101346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddio A., Katz J., Ilersich A.L., Koren G. Effect of neonatal circumcision on pain response during subsequent routine vaccination. Lancet. 1997;349(9052):599–603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)10316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddio A., Stevens B., Craig K., Rastogi P., Ben-David S., Shennan A., Mulligan P., Koren G. Efficacy and safety of lidocaine-prilocaine cream for pain during circumcision. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;336(17) doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704243361701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbert L.M., Facog E., Kraybill E.N., Potter H.D. Adrenal cortical response to circumcision in the neonate. Obstet. Gynecol. 1976;48(2):208–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullmann E., Licinio J., Barthel A., Petrowski K., Oratovski B., Stalder T., Kirschbaum C., Bornstein S.R. Circumcision does not alter long-term glucocorticoids accumulation or psychological effects associated with trauma- and stressor-related disorders. Transl. Psychiatry. 2017;7(3) doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S.M. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2019. Long-term effects of neonatal pain. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson P.J., Morris R.J. Narcissism, empathy and social desirability. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 1991;12(6):575–579. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss A.J., Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. Healthc. Cost Util. Proj. Stat. Br. 2014 #180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellington N., Rieder M.J. Attitudes and practices regarding analgesia for newborn circumcision. Pediatrics. 1993;92(4):541–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson P.S., Evans N.D., Donovan Evans N. Neonatal cortisol response to circumcision with anesthesia. Clin. Pediatr. 1986;25(8):412–415. doi: 10.1177/000992288602500807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson P.S., Williamson M.L. Physiologic stress reduction by a local anesthetic during newborn circumcision. Pediatrics. 1983;71(1):36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiswell T.E., Enzenauer R.W., Cornish J.D., Hankins C.T. Declining frequency of circumcision: implications for changes in the absolute incidence and male to female sex ratio of urinary tract infections in early infancy. Pediatrics. 1987;139(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Neonatal and child male circumcision: a global review. Unaids. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2009. Manual for Male Circumcision under Local Anaesthesia. Geneva WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Young E.S., Simpson J.A., Griskevicius V., Huelsnitz C.O., Fleck C. Childhood attachment and adult personality: a life history perspective. Self Ident. 2017;18(1):22–38. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with this study has been deposited at https://osf.io/znhp8/?view_only=a95c7e6d7de34facb9c043d2c9953ced.