Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to evaluate the potential of voclosporin (VOS) in preventing goblet cell (GC) loss and modulating interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) producing CD4+ T cells in the mouse desiccating stress (DS) dry eye model.

Methods: Mice were subjected to DS and treated topically with vehicle, VOS, or cyclosporine A as a treatment control. Corneal barrier function was evaluated after 5 and conjunctival GC density after 10 days of desiccation. CD4+ T cells were isolated from ocular surface draining lymph nodes of dry eye donor mice and adoptively transferred into immune deficient RAG1−/− mice from which tears and conjunctiva were collected for the evaluation of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and GC density.

Results: Compared to the vehicle-treated group, VOS was significantly better in preserving corneal barrier function and preventing DS-induced conjunctival GC loss. CD4+ T cells from VOS treated dry eye donors caused less conjunctival GC loss than vehicle and suppressed expression of IFN-γ signature genes to a similar extent and transforming growth factor-beta to a greater extent than cyclosporine in adoptive transfer recipients.

Conclusion: These findings suggest that VOS preserves corneal barrier function and conjunctival GCs and suppresses IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells in experimental dry eye.

Keywords: dry eye, desiccating stress, voclosporin, interferon-gamma

Introduction

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca, the ocular surface dry eye disease (DED), is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory condition of the ocular surface due to an aqueous deficiency that results in symptoms of discomfort, tear film instability, and visual disturbance.1 Conjunctival goblet cells (GCs) secrete a large molecular weight gel-forming mucin, which retains water and keeps the ocular surface lubricated, and they also produce immunoregulatory factors such as retinoic acid and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β).2–4 GC loss in DED is associated with greater ocular surface inflammation and expression of the Th1 associated cytokine interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) suggesting that GCs maintain immunological tolerance on the ocular surface.5 IFN-γ produced by T cells and innate cells during desiccation stress causes apoptosis in GCs.6 Consistent with this activity, IFN-γ KO mice are resistant to desiccation stress-induced GC loss.6 This suggests that IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells are a therapeutic target for modulating immune-mediated GC loss in DED.4,7,8

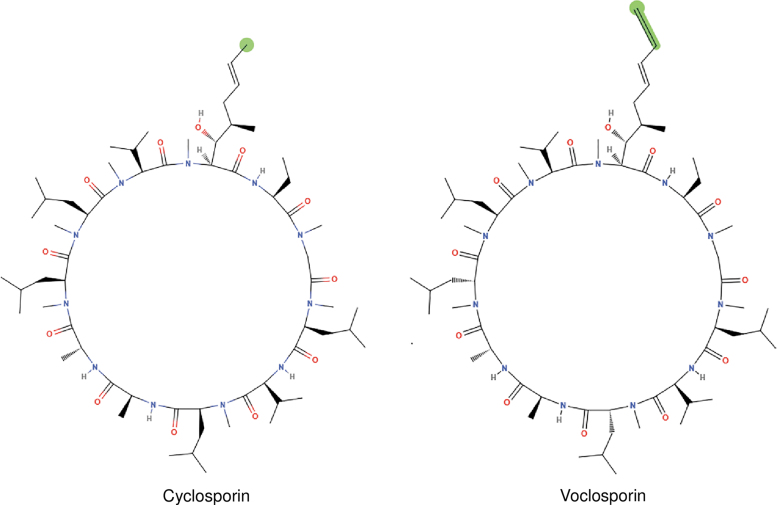

Cyclosporine A (CsA) is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved T cell immunomodulatory agent used in dry eye patients. A recent meta-analysis showed that CsA increases conjunctival GC density in DED.9 Other studies have also shown that CsA significantly increases or prevents GC loss in DED.10–13 CsA binds with cyclophilin and inhibits phosphatase activities of calcineurin, which regulates translocation and subsequent activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells, thus blocking transcription of cytokine genes, including IFN-γ in activated T cells.14 Voclosporin (VOS) is a next generation calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) that is structurally similar to CsA, except for a modification in the side chain of amino acid-1 of the molecule (Fig. 1). This modification renders VOS 3–4 times more potent than cyclosporine.15,16 Similar to CsA, VOS inhibits calcineurin and blocks interleukin (IL)-2 expression and T cell mediated immune responses.17

FIG. 1.

Voclosporin. A semisynthetic structural analog of cyclosporine A, with an additional single carbon extension that has a double bond on one side chain.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the potential of VOS in preventing GC loss and modulating IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells in the mouse desiccating stress (DS) dry eye model.

Methods

Animal

Animal protocol for this study was designed according to the instruction of Association for Research in Vision and Opthalmology Statement for the use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine, Center for Comparative Medicine. Female C57BL/6J mice, aged 6–8 weeks, were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and allowed to rest in a humidified environment for a week before the experiment.

DS model of dry eye

DS was induced by subcutaneous injection of scopolamine hydrobromide (0.5 mg/0.2 mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis) 4 times daily at 3 h interval, alternating between the left and right flanks of animals, as previously described.18 Mice were placed in modified cages with a perforated plastic screen to allow airflow from both sides. Room humidity was maintained at around 30%.

Topical treatment with VOS

There were 4 experimental groups, a no treatment control, and 3 groups receiving one of these topical treatments: VOS ophthalmic solution (0.2%, clear micellar solution; Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Victoria, BC), vehicle of VOS, or CsA (RestasisTM; Allergan, Irvine, CA). Mice received 1 drop (2 μL) of one of these treatments in both eyes, twice a day (BID), initiated on day 1 (concurrently with the start of DS exposure), and continued through either day 5 or 10. C57BL/6J female mice were used to measure corneal barrier disruption (n = 15, day 5 of DS), GC density (n = 5, day 10 of DS), and to measure gene expression (n = 8). RAG1−/− mice (n = 5) were used to measure GC density and measure gene expression (n = 8) in conjunctiva 3 days after adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells. Tear washings were collected from live mice 2 days after adoptive transfer.

Assessment of corneal barrier function

Corneal epithelial permeability to 70 kDa Oregon-Green-conjugated dextran (OGD; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) was assessed as previously described.19 Briefly, 1 μL of OGD (50 mg/mL) was instilled onto the ocular surface 1 min before euthanasia; the eye was then rinsed with 2 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) from the temporal and nasal side and photographed with a high-resolution digital camera (Coolsnap HQ2; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) attached to a stereoscopic zoom microscope (SMZ 1500; Nikon, Melville, NY), under fluorescence excitation at 470 nm. The severity of corneal OGD staining was graded in digital images using NIS Elements (version 3.0; Nikon) within a 2-mm diameter circle placed on the central cornea by 2 masked observers. The mean fluorescence intensity measured by the software inside this central zone was transferred to a database, and the results were averaged within each group.

Measurement of GC density

Following euthanasia, eyes and ocular adnexa were excised (n = 5/group), fixed in 10% formalin, paraffin embedded, and 5-μm sections were cut with a microtome (Microm HM 340E; Thermo Fisher, Wilmington, DE). Sections were stained with periodic acid Schiff (PAS) reagent. Sections from 5 left eyes in each group were examined and photographed with a microscope (Eclipse E400; Nikon) equipped with a digital camera (DXM1200; Nikon). Using the NIS Elements software, GCs were manually counted. To determine the length of the conjunctival GC zone, a line was drawn on the surface of the conjunctiva image from the first to the last PAS+ GC. Results are presented as PAS+ GCs/mm.

Isolation of murine CD4+ T cells and adoptive transfer

Superficial cervical lymph nodes and spleens from donor C57BL/6 mice were gently meshed between 2 frosted end slides, as previously described.20,21 Ammonium chloride Tris solution was used to eliminate erythrocytes. Untouched CD4+ T cells were isolated by negative selection using magnetic beads according to the manufacturer's instructions (MACS system; Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Isolated CD4+ T cells (5 × 106 cells; approximately 1 donor-equivalent of cells) were transferred intraperitoneally to T cell-deficient RAG1−/− female mice. Ocular surface tear washing was collected 2 days after adoptive transfer of CD4+ T cells. Recipient mice were euthanized 72 h after adoptive transfer (AT), and tissues were used for either histology or polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Following euthanasia, the conjunctiva was excised from RAG1−/− on day 3 after adoptive transfer, and total RNA was extracted using a QIAGEN RNeasy Plus Micro RNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer's instruction. The RNA concentration was measured, and cDNA was synthesized using the Ready-To-Go-You-Prime-First-Strand Kit (GE Healthcare). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with specific probes Murine MGB probes, IFN-γ (Mm00801778), Chemokine (C–X–C motif) ligand 9 (Mm00434946), CXCL10 (Mm00445235), interleukin 12A (Mm00434165_m1), TGF-β1 (Mm00441724), TGF-β2 (Mm00436952_m1), Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 2 (Mm00441242), and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT1) (Mm00446968). The HPRT-1 gene was used as an endogenous reference for each reaction. The results of real-time PCR were analyzed by the comparative CT method.

Tear washings and MILLIPLEX assay

Tear-fluid washings were collected from RAG1−/− recipient mice on day 2 postadoptive transfer using capillary tubes as previously described.22 One sample consists of tear washing from both eyes of one mouse pooled (2 μL) into a tube containing 8 μL of PBS +0.1% bovine serum albumin and stored at −80°C until the assay was performed. Cytokine–chemokine concentrations [IFN-γ, IL12(p40), IL12(p70), CXCL-10, CCL2] in tear samples were assayed using a commercial Luminex MILLIPLEX Assay according to the manufacturer's protocol (EMD Millipore Corporation, St. Charles, MO). The reactions were detected with streptavidin–phycoerythrin using a Luminex 100 IS 2.3 system (Austin, TX).19 Biologic replicate samples were averaged. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (pg/mL).

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated using StatMate 2 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) based on pilot studies to have at least 90% power to detect differences with an alpha of 0.05. Based on normality, parametric student t or nonparametric Mann–Whitney U tests were performed for statistical comparisons with an alpha of 0.05 using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Results

VOS improves corneal barrier function and GC density

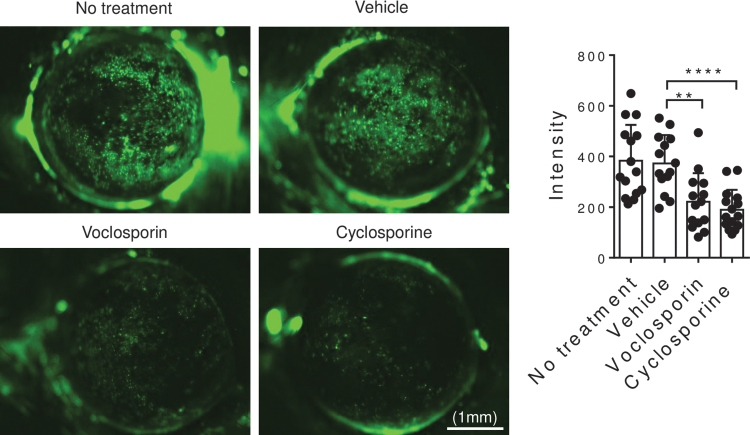

Corneal barrier disruption, clinically observed as corneal fluorescein staining, is a hallmark of DED. We evaluated the effects of VOS on DS-induced corneal permeability by measuring the uptake of the fluorescent dextran molecule OGD. Corneal barrier disruption was significantly lower in VOS (P = 0.001) and cyclosporine (P = 0.0001) compared to no treatment or vehicle treatment groups (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Voclosporin treatment preserves corneal barrier function. Representative images of 70 kDa Oregon-Green-conjugated dextran staining of cornea in mice subjected to DS for 5 days and without or with topical treatment (vehicle, voclosporin 0.2%, cyclosporine A 0.05%) 2 times daily for 5 days (n = 15/group). Bar graphs represent mean + standard deviation. Individual dots represent average of right and left eyes. **P = 0.0015, ****P = 0.0001. DS, desiccating stress.

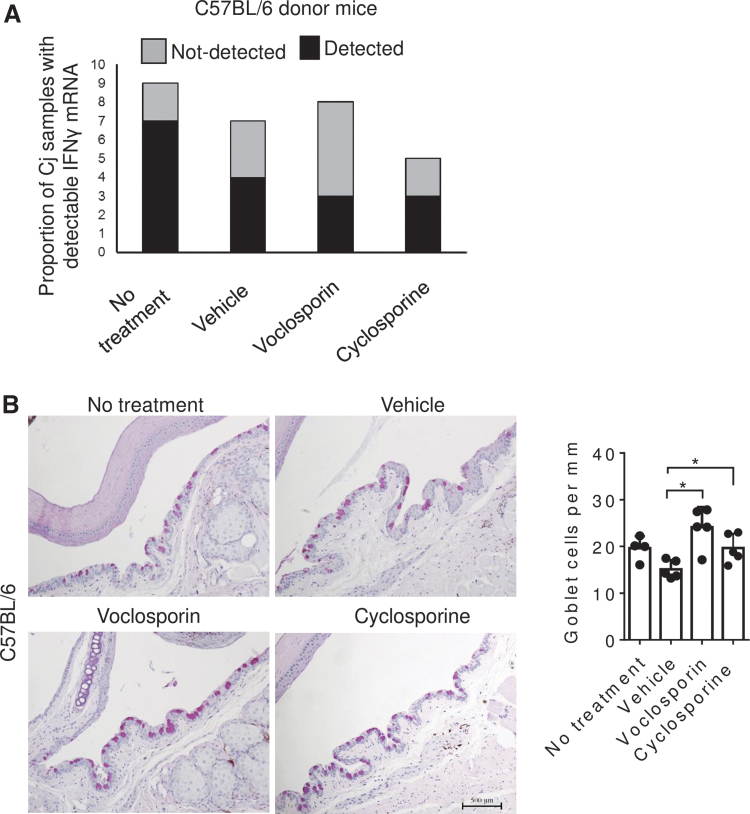

The cytokine IFN-γ produced during DED decreases GC density.6 The effects of VOS on the expression level of IFN-γ in the conjunctiva and conjunctival GC density were determined after 10 days of DS. IFN-γ mRNA was detected in only 37.5% of the samples treated with VOS compared to 78% of the untreated and 57% of the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 3A). GC density was also found to be significantly higher in VOS and cyclosporine-treated groups compared to vehicle (Fig. 3B, P < 0.05).

FIG. 3.

Voclosporin treatment prevented desiccation-induced GC loss. (A) Proportion of samples with detectable IFN-γ mRNA after 40 cycles in conjunctiva (Cj) obtained from C57BL/6 mice subjected to DS for 10 days. (B) Representative images of filled GCs counted in PAS stained sections in the GC-rich zone of the conjunctiva of C57BL/6 mice subjected to DS without or with topical treatment BID (vehicle, voclosporin 0.2% or cyclosporine A 0.05%) for 10 days. Each graph bar represents mean + standard deviation. Individual dots represent average of right and left eyes. *P = 0.03 (n = 5 per group). IFN-γ, interferon-gamma; GC, goblet cell; PAS, periodic acid Schiff; DS, desiccating stress.

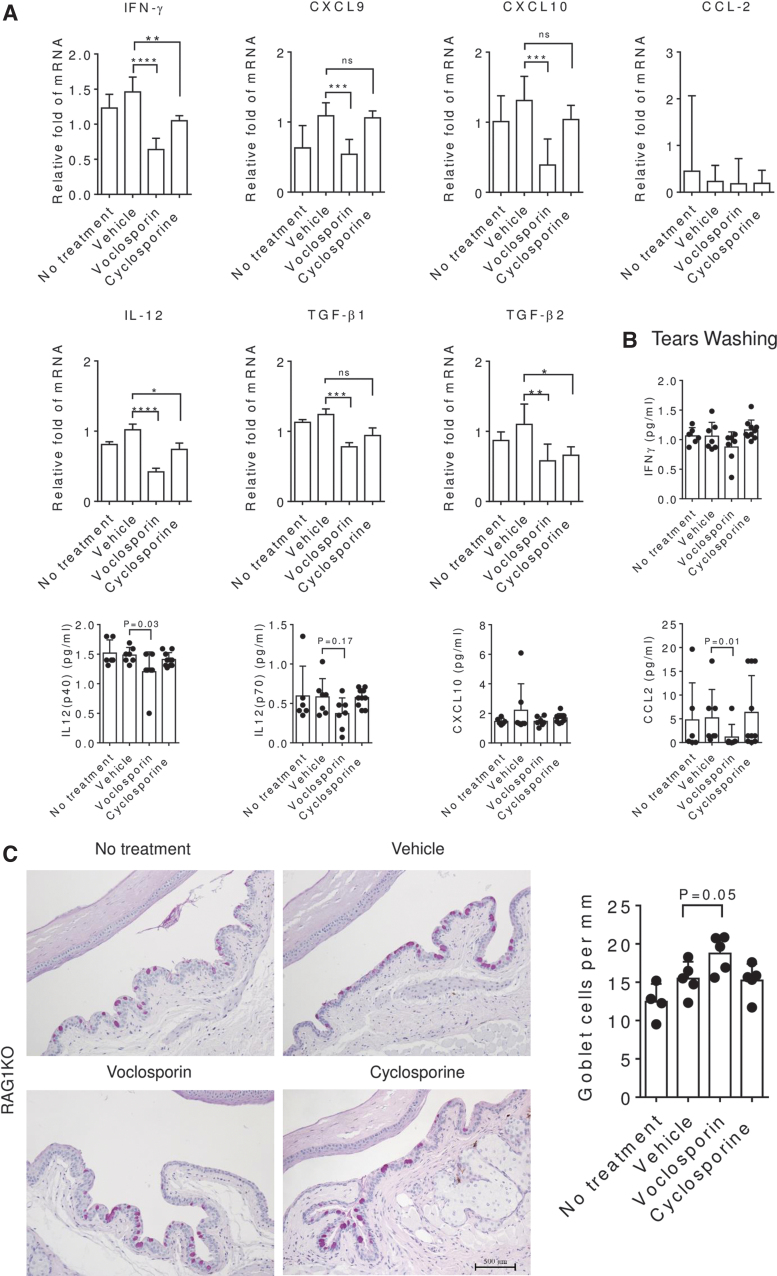

VOS decreases generation of pathogenic CD4+ T cells

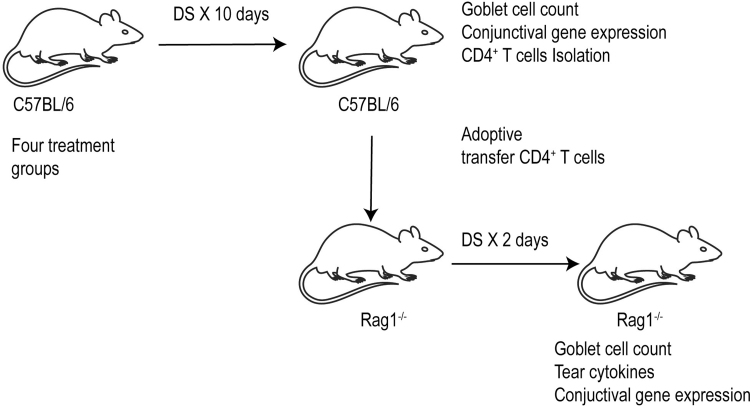

To better understand the effect of VOS on the generation of Th1-pathogenic CD4+ T cells, we used an adoptive transfer model in which untouched CD4+ T cells from C57BL/6 donor mice subjected to desiccation after receiving the 3 treatments were isolated and adoptively transferred to T cell deficient mice (Fig. 4). Tear washing was collected after 48 h, and final euthanasia was performed at 72 h to collect tissues for gene expression analysis. Tear washing showed that VOS significantly decreased IL-12 (p40) and CCL2 concentration levels compared to its vehicle (Fig. 5B). RAG1−/− mice which received CD4+ T cells from VOS-treated donors had a significantly higher number of GC compared to donors receiving no treatment or vehicle treatment (Fig. 5C). Conjunctival biopsies were collected upon euthanasia, and expression of IFN-γ-family genes (IFN-γ, CXCL9, CXCL10, IL-12, CCL2) and other anti-inflammatory genes (TGF-β1, TGF-β2) was investigated by real-time PCR. RAG1−/− recipients of CD4+ cells from VOS treated donors had significantly decreased IFN-γ and transcripts of its signature genes CXCL9, CXCL10, and IL-12 mRNA transcripts and also suppressed expression of TGF-β1/TGF-β2 in the conjunctiva (Fig. 5A). These suppressive effects were similar or greater than the treatment control CsA.

FIG. 4.

Experimental design. C57BL/6 mice were exposed to DS for 5 or 10 days without or with topical treatment (vehicle, voclosporin 0.2%, cyclosporine A 0.05%) 2 times daily, and CD4+ T cells were isolated from their spleens and draining nodes and adoptively transferred into RAG1−/− mice. Adoptive transfer recipients were subjected to DS for 2 days, and conjunctival GCs, tear cytokines, and conjunctival gene expression were evaluated.

FIG. 5.

Pathogenicity of adoptively transferred CD4+ cells. C57BL/6 donor mice were subjected to desiccation for 10 days without or with topical treatment (vehicle, voclosporin 0.2% or cyclosporine A 0.05% BID), and CD4+ T cells were isolated from their spleens and draining nodes and adoptively transferred into RAG1−/− mice. (A) Cytokines and chemokines IFN-γ, IL-12p70, CXCL10, CCL2 concentrations detected in the tears obtained from RAG1−/− mice 2 days after adoptive transfer. (B) Representative images of conjunctiva sections stained with PAS to count GCs and generate the bar graph on the right. Each dot represents the average of 3 sections counted 500 μm apart in the conjunctivae of the same animal. (C) Relative fold mRNA expression of cytokine and chemokines IFN-γ, CXCL9, CXCL10, CCL2, IL-12, TGF-β1, and TGF-β2 in the conjunctiva of RAG1−/− mice 3 days after CD4 adoptive transfer. TGF-β, transforming growth factor-beta; IL, interleukin; BID, twice per day.

Discussion

VOS is a CNI with demonstrated immunosuppressive activity. It was found to increase renal allograft survival and suppress inflammation in autoimmune disease models, including collagen induced arthritis and experimental uveitis.23–26 VOS was recently evaluated in a Phase II parallel, randomized, investigator-masked study assessing the safety and tolerability of VOS 0.2% BID versus commercial cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05% BID in subjects with DED. Subjects (n = 100) were randomized (1:1) to receive either VOS BID or cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion BID for 28 days. There was no difference in tolerability between these drugs; however, VOS was statistically superior to cyclosporine emulsion at most time points for change from baseline in Schirmer tear test (STT) and fluorescein corneal staining (FCS). A statistically significantly higher percentage of subjects in the VOS group achieved a ≥10 mm improvement in STT (42.9% vs. 18.4%, P = 0.0055) and FCS (−2.2 vs. −0.2, P = 0.0003).

Our study evaluated the efficacy of VOS in a validated mouse DS dry eye model. Similar to the FDA approved CNI cyclosporine, VOS improved corneal barrier function and preserved conjunctival GCs. To determine if VOS suppressed generation of pathogenic Th1 cells in mice subjected to DS, CD4+ T cells were isolated from these mice and adoptively transferred to naive immunodeficient RAG1−/− recipients. We found significantly higher conjunctival GC density (Fig. 5C) and lower expression of IFN-γ, IL-12, and the Th1 chemokines, CXCL9 and CXCL10, in the conjunctiva of adoptive transfer recipients of VOS treated donors (Fig. 5A). Th1 cells from VOS treated donors also caused less GC loss in the recipients than those treated with cyclosporine (Fig. 5C). IFN-γ is recognized to cause GC dysfunction and loss in human and experimental murine DED.6,27 Suppression of IFN-γ expression in the conjunctiva of dry eye donor mice and its inducible Th1 chemokines, CXCL9 and CXCL10, in the conjunctiva of recipient RAG1−/− mice indicates that VOS inhibits mediators that are relevant in the pathogenesis of the conjunctival metaplasia that develops in aqueous tear deficiency.

TGF-β is another cytokine with important immunoregulatory function. Although it can inhibit cellular proliferation, it is also critical to the induction of Th17 cells. In the DS dry eye model, TGF-β1 and IL-17A were increased in the conjunctiva.28 In the DS model, disruption of TGF-β signaling resulted in improved corneal barrier function, decreased CD4+ T cell infiltration, decreased Th17 and IFN-γ transcripts, and an increase in GCs.29 In addition to reducing Th1 response transcripts, VOS also significantly reduced TGF-β1 and -β2 mRNA levels in the conjunctiva of RAG1−/− recipient mice. Inhibition of TGF-β receptor I in cultured corneal epithelial cells promoted proliferation of cells expressing stem and transient amplifying cell markers, suggesting that inhibition of TGF-β in vivo may promote survival of certain ocular surface epithelia with proliferative potential.30

In summary, these studies highlight the potential of VOS for suppressing dry eye induced Th1 and TGF-β responses and reducing their pathological effects on the ocular surface epithelium.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by a sponsored research contract with ImmuneEyez (Mission Viejo, CA) in collaboration with Aurina Pharmaceuticals (Victoria, BC), National Institute of Health EY-002520-36 (Core Grant for Vision Research Department of Ophthalmology). Research to Prevent Blindness (Department of Opthalmology), The Oshman Foundation, William Stamps Farish Fund, Hamill Foundation, Sid Richardson Foundation and by Baylor Pathology Core (NIH CA125123).

References

- 1. Craig J.P., Nichols K.K., Akpek E.K., et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul. Surf. 15:276–283, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stephens D.N., and McNamara N.A.. Altered mucin and glycoprotein expression in dry eye disease. Optom. Vis. Sci. 92:931–938, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xiao Y., de Paiva C.S., Yu Z., et al. Goblet cell-produced retinoic acid suppresses CD86 expression and IL-12 production in bone marrow-derived cells. Int. Immunol. 30:457–470, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coursey T.G., Tukler Henriksson J., Barbosa F.L., et al. Interferon-gamma-induced unfolded protein response in conjunctival goblet cells as a cause of mucin deficiency in Sjogren syndrome. Am. J. Pathol. 186:1547–1558, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barbosa F.L., Xiao Y., Bian F., et al. Goblet cells contribute to ocular surface immune tolerance-implications for dry eye disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:978, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Paiva C.S., Villarreal A.L., Corrales R.M., et al. Dry eye-induced conjunctival epithelial squamous metaplasia is modulated by interferon-gamma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48:2553–2560, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bimczok D., Kao J.Y., Zhang M., et al. Human gastric epithelial cells contribute to gastric immune regulation by providing retinoic acid to dendritic cells. Mucosal Immunol. 8:533–544, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang X., Chen W., De Paiva C.S., et al. Interferon-γ exacerbates dry eye-induced apoptosis in conjunctiva through dual apoptotic pathways. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52:6279–6285, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Paiva C.S., Pflugfelder S.C., Ng S.M., et al. Topical cyclosporine A therapy for dry eye syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9:CD010051, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perry H.D., Solomon R., Donnenfeld E.D., et al. Evaluation of topical cyclosporine for the treatment of dry eye disease. Arch. Ophthalmol. 126:1046–1050, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coursey T.G., Wassel R.A., Quiambao A.B., et al. Once-daily cyclosporine-A-MiDROPS for treatment of dry eye disease. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 7:24, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kunert K.S., Tisdale A.S., and Gipson I.K.. Goblet cell numbers and epithelial proliferation in the conjunctiva of patients with dry eye syndrome treated with cyclosporine. Arch. Ophthalmol. 120:330–337, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pflugfelder S.C., Corrales R.M., and de Paiva C.S.. T helper cytokines in dry eye disease. Exp. Eye Res. 117:118–125, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matsuda S., and Koyasu S.. Mechanisms of action of cyclosporine. Immunopharmacology. 47:119–125, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dumont F.J. ISAtx-247 (Isotechnika/Roche). Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 5:542–550, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anglade E., Yatscoff R., Foster R., et al. Next-generation calcineurin inhibitors for ophthalmic indications. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 16:1525–1540, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schultz C. Voclosporin as a treatment for noninfectious uveitis. Ophthalmol. Eye Dis. 5:5–10, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beardsley R.M., De Paiva C.S., Power D.F., et al. Desiccating stress decreases apical corneal epithelial cell size—modulation by the metalloproteinase inhibitor doxycycline. Cornea. 27:935–940, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zaheer M., Wang C., Bian F., et al. Protective role of commensal bacteria in Sjogren syndrome. J. Autoimmun. 93:45–56, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Niederkorn J.Y., Stern M.E., Pflugfelder S.C., et al. Desiccating stress induces T cell-mediated Sjögren's syndrome-like lacrimal keratoconjunctivitis. J. Immunol. 176:3950–3957, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang D.D., and Hu F.B.. Precision nutrition for prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6:416–426, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zheng X., De Paiva C.S., Rao K., et al. Evaluation of the transforming growth factor-beta activity in normal and dry eye human tears by CCL-185 cell bioassay. Cornea. 29:1048–1054, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maksymowych W.P., Jhangri G.S., Aspeslet L., et al. Amelioration of accelerated collagen induced arthritis by a novel calcineurin inhibitor, ISA(TX)247. J. Rheumatol. 29:1646–1652, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cunningham M.A., Austin B.A., Li Z., et al. LX211 (voclosporin) suppresses experimental uveitis and inhibits human T cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50:249–255, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gregory C.R., Kyles A.E., Bernsteen L., et al. Compared with cyclosporine, ISATX247 significantly prolongs renal-allograft survival in a nonhuman primate model. Transplantation. 78:681–685, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bissonnette R., Papp K., Poulin Y., et al. A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of ISA247 in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 54:472–478, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang X., De Paiva C.S., Su Z., et al. Topical interferon-gamma neutralization prevents conjunctival goblet cell loss in experimental murine dry eye. Exp. Eye Res. 118:117–124, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De Paiva C.S., Chotikavanich S., Pangelinan S.B., et al. IL-17 disrupts corneal barrier following desiccating stress. Mucosal Immunol. 2:243–253, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. De Paiva C.S., Volpe E.A., Gandhi N.B., et al. Disruption of TGF-beta signaling improves ocular surface epithelial disease in experimental autoimmune keratoconjunctivitis sicca. PLoS One. 6:e29017, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hu L., Pu Q., Zhang Y., et al. Expansion and maintenance of primary corneal epithelial stem/progenitor cells by inhibition of TGF-beta receptor I-mediated signaling. Exp. Eye Res. 182:44–56, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]