Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic imposed multiple restrictions on health care services.

Objective

To investigate the impact of the pandemic on Allergy & Immunology (A&I) services in the United Kingdom.

Methods

A national survey of all A&I services registered with the Royal College of Physicians and/or the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology was carried out. The survey covered staffing, facilities, personal protective equipment, appointments & patient review, investigations, treatments, and research activity. Weeks commencing February 3, 2020 (pre–coronavirus disease), April 6, 2020, and May 8, 2020, were used as reference points for the data set.

Results

A total of 99 services participated. There was a reduction in nursing, medical, administrative, and allied health professional staff during the pandemic; 86% and 92% of A&I services continued to accept nonurgent and urgent referrals, respectively, during the pandemic. There were changes in immunoglobulin dose and infusion regimen in 67% and 14% of adult and pediatric services, respectively; 30% discontinued immunoglobulin replacement in some patients. There was a significant (all variables, P ≤ .0001) reduction in the following: face-to-face consultations (increase in telephone consultations), initiation of venom immunotherapy, sublingual and subcutaneous injection immunotherapy, anesthetic allergy testing, and hospital procedures (food challenges, immunoglobulin and omalizumab administration); and a significant increase (P ≤ .0001) in home therapy for immunoglobulin and omalizumab. Adverse clinical outcomes were reported, but none were serious.

Conclusions

The pandemic had a significant impact on A&I services, leading to multiple unplanned pragmatic amendments in service delivery. There is an urgent need for prospective audits and strategic planning in the medium and long-term to achieve equitable, safe, and standardized health care.

Key words: COVID-19, Allergy, Immunology, Service, Impact, Immunodeficiency

Abbreviations used: A&I, Allergy and Immunology; BSACI, British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology; COVID, Coronavirus disease; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CSU/A, Chronic spontaneous urticaria and angioedema; IgRT, Immunoglobulin replacement therapy; IQAS, Improving Quality in Allergy Services; NHS, National Health Service; RCP, Royal College of Physicians; SCIT, Subcutaneous immunotherapy; SLIT, Sublingual immunotherapy; VIT, Venom immunotherapy

What is already known about this topic? There are no published data regarding the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on Allergy & Immunology services in the UK National Health Service.

What does this article add to our knowledge? Data showed reduction in face-to-face consultations, increase in remote consultations, reduced access to allergy testing, and increase in self-administration of omalizumab and immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

How does this study impact current management guidelines? These findings will shape new guidelines regarding delivery of an equitable, safe, and standardized Allergy & Immunology service and governance framework in the postpandemic recovery phase.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID) 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has presented unique and unprecedented challenges to health service delivery globally. Health services have had to rapidly implement measures to reduce virus transmission rates, which has involved risk stratification and service prioritization to focus on emergency care and where feasible, cancer care—the aim being to reduce patient volumes in clinical areas and limit potential exposure for patients, their caregivers, and health care professionals.

Allergic disorders such as allergic rhinitis, asthma, and food allergy are among the most common noncommunicable diseases worldwide,1 and the United Kingdom has one of the highest prevalence rates in the world. Health service delivery for these conditions is primarily outpatient-based. There is a huge unmet demand for allergy services globally, and specifically there is inadequate and uneven distribution of specialist allergy services across the United Kingdom.1, 2, 3

The National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom offers specialist Allergy and Immunology (A&I) services for children and adults in secondary care, with some heterogeneity with respect to the professional background and training of clinicians involved in service delivery, and the repertoire of services within each center.2 , 4 Adult allergy services are delivered by specialists in allergy and/or clinical immunology, and organ-based specialists such as respiratory physicians. Pediatric allergy services are delivered by pediatric allergists and general pediatricians with an interest in allergy. Some services provide only allergy or immunology services, and others offer joint services including A&I within adult or pediatric departments.

Several recent publications have described the restrictions imposed by COVID-19 alongside prioritization and newer models of care in A&I and other medical and surgical specialties.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Specifically, the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI), the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology issued expert/consensus guidance regarding safe and strategic delivery of specialist A&I services during the pandemic.10, 11, 12

We sought to assess the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on A&I services within secondary health care NHS facilities in the United Kingdom. This was a collaborative project involving the accreditation unit of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) of London, the BSACI, and the UK Primary Immunodeficiency Network. Because this was a national A&I services survey without patient involvement, ethics committee approval was not sought. This survey generated baseline data to shape national policy for A&I services during the recovery phase of the pandemic.

Methods

Questions relating to allergy and immunodeficiency service delivery were designed by an expert panel led by M.T.K. and C.B. (from the RCP) and A.F.W. (from the BSACI), with administrative support from the RCP accreditation unit. A draft of the questionnaire was circulated for consultation via representatives of BSACI (P.J.T. and S.N.) and UKPIN (R.S. and S.H.). Feedback was reviewed and the final version agreed.

Three separate questionnaires were designed using the Survey Monkey platform, for allergy, immunology, and combined A&I services (see Supplemental Text E1-E3 in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). Generic questions were common to all versions, and specific elements unrelated to the respective specialty were removed (eg, immunology questions were removed in allergy service questionnaire and vice versa). The survey was launched on June 30, 2020, and was open for 4 weeks, during which 2 email reminders were sent. Where possible, the investigators contacted service clinical leads directly via telephone, email, and/or text messaging to request responses before the closing date.

The first cases of COVID-19 occurred in the United Kingdom in late January 2020, with significant increase through March and a peak in mid-April. We therefore chose 3 time points to study the impact of COVID-19: the week commencing February 3, 2020 (as a baseline data set), and the weeks commencing April 6, 2020, and May 8, 2020. During the study period, generic guidelines with respect to restrictions were put in place by the UK Department of Health. Hence, these regulations were common to all NHS hospitals in all geographical areas.

Briefly, questions covered generic domains including workforce, estates & facilities, referral pathways, appointment scheduling, provision of personal protective equipment for staff, screening patients for COVID-19, perceived positive changes in clinical practice, and specialty-specific questions relating to allergy testing (eg, drugs and venoms), open food and drug challenges (hospital and home), allergen-specific immunotherapy including venom immunotherapy (VIT), subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT), and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) for allergic rhinitis, omalizumab for chronic spontaneous urticaria and angioedema (CSU/A; hospital and home therapy), subcutaneous immunoglobulin and intravenous immunoglobulin replacement therapy (hospital and home therapy), access to laboratory investigations, and occurrence of COVID-19 cases among patients with immunodeficiency.

All participating services were registered with the RCP accreditation unit and/or the BSACI. A link to the appropriate survey was emailed to clinical leads registered with Improving Quality in Allergy Services (IQAS accreditation program; 28 services; pediatric allergy is not currently a part of this program) and to clinical leads registered with Quality in Primary Immunodeficiency Services accreditation program (39 services), both under the auspices of the RCP accreditation unit. Two additional Quality in Primary Immunodeficiency Service unregistered Immunology centers were contacted directly and the immunodeficiency survey was then forwarded. A link to the survey was also sent out to the BSACI membership to allow pediatric allergy services and other non-IQAS registered services to participate. Responses were checked to ensure that no centers completed more than 1 version of the relevant survey.

Data were collected in MS Excel, and a descriptive analysis was performed and tabulated. Statistical analysis was conducted using MedCalc Statistical Software version 19.4.1 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium); because data were not normally distributed, Wilcoxon matched paired sign-rank test was used to compare continuous variables; a P value of less than.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

A total of 99 services (involving 79 centers) including adult immunology, adult allergy, pediatric immunology, and pediatric allergy completed survey forms. There were 38 immunology services registered with Quality in Primary Immunodeficiency Service either as adult immunology centers, pediatric immunology centers, or both. Of the 32 adult immunology services, 29 (94%) completed the survey. These responses included 1 service with a combined adult and pediatric service. All 7 pediatric-only immunology centers (100%) completed the survey. There were 30 allergy centers registered with IQAS, of whom 26 (87%) completed the survey. There were 22 additional adult allergy services on the BSACI database, of which 6 (26%) completed the survey, giving an overall response rate of 32 of 52 services (62%). Because the IQAS accreditation scheme does not cover pediatric allergy services, they were contacted via BSACI. There are 92 pediatric allergy centers on the BSACI database, of which 30 (33%) completed the survey.

Data regarding responses to generic questions and specialty-specific questions are summarized in Table I, Table II, Table III , Table E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org, Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 , and Online Repository Supplemental Text E4 at www.jaci-inpractice.org.

Table I.

Data summarizing responses to generic questions

| Question no. | Question | Subcategories | Adult immunology, n (%) | Pediatric immunology, n (%) | Adult allergy, n (%) | Pediatric allergy, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staffing | |||||||

| 1 | Has a requirement for staff members to shield and/or self- isolate had an impact on your service? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 32 (100) | 30 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Yes, but they are generally able to work from home | 18 (60) | 4 (57.1) | 13 (40.6) | 12 (40) | 47 (47.5) | ||

| Yes, but they are generally unable to work from home | 6 (20) | 2 (28.6) | 8 (25) | 4 (13.3) | 20 (20.2) | ||

| No significant impact | 6 (20) | 1 (14.3) | 11 (34.4) | 14 (46.7) | 32 (32.3) | ||

| Facilities | |||||||

| 2a | Has the physical space available for your service been affected by changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic in day-case units? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 32 (100) | 30 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Yes | 25 (83.3) | 5 (71.4) | 29 (90.6) | 24 (80) | 83 (83.8) | ||

| No | 5 (16.7) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (9.4) | 6 (20) | 16 (16.2) | ||

| 2b | Has the physical space available for your service been affected by changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic in outpatient units? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 32 (100) | 30 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Yes | 24 (80) | 6 (85.7) | 28 (87.5) | 28 (93.3) | 86 (86.9) | ||

| No | 6 (20) | 1 (14.3) | 4 (12.5) | 2 (6.7) | 13 (13.1) | ||

| 3 | Are you aware of specific patients with adverse clinical outcomes resulting from changes in service provision? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 32 (100) | 30 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Yes | 8 (26.7) | 1 (14.3) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (16.7) | 28 (28.3) | ||

| No | 22 (73.3) | 6 (85.7) | 18 (56.3) | 25 (83.3) | 71 (71.7) | ||

| Service recovery | |||||||

| 4 | What positive impact of the adjustments to service provision due to COVID-19 have you identified? | No. of respondents | 29 (96.7) | 7 (100) | 31 (96.9) | 28 (93.3) | 95 (96) |

| Perceived reduced risk of infection by staff | 20 (69) | 2 (28.6) | 20 (64.5) | 12 (42.9) | 54 (56.8) | ||

| Perceived reduced risk of infection by patients | 26 (89.7) | 2 (28.6) | 23 (74.2) | 15 (53.6) | 66 (69.5) | ||

| Reduced carbon footprint due to less travel | 26 (89.7) | 7 (100) | 28 (90.3) | 23 (82.1) | 84 (88.4) | ||

| Reduced health service overhead costs | 13 (44.8) | 2 (28.6) | 10 (32.3) | 7 (25) | 32 (33.7) | ||

| Reduced patient travel time | 28 (96.6) | 7 (100) | 30 (96.8) | 23 (82.1) | 88 (92.6) | ||

| Reduced patient nonattendance rates | 15 (51.7) | 3 (42.9) | 19 (61.3) | 14 (50) | 51 (53.7) | ||

| Improved flexibility in health care professionals' time | 16 (55.2) | 5 (71.4) | 15 (48.4) | 20 (71.4) | 56 (58.9) | ||

| Other | 7 (24.1) | 3 (42.9) | 7 (22.6) | 7 (25) | 24 (25.3) | ||

| 5a | Will the requirement for social distancing in accordance to government guidelines impact your ability to deliver the pre-COVID level of service for outpatients? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 32 (100) | 30 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Yes | 27 (90) | 7 (100) | 28 (87.5) | 30 (100) | 92 (92.9) | ||

| No | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 7 (7.1) | ||

| 5b | Will the requirement for social distancing in accordance to government guidelines impact your ability to deliver the pre-COVID level of service for day-case? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 32 (100) | 30 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Yes | 27 (90) | 5 (71.4) | 26 (81.3) | 26 (86.7) | 84 (84.8) | ||

| No | 3 (10) | 2 (28.6) | 6 (18.8) | 4 (13.3) | 15 (15.2) | ||

| Service provision | |||||||

| 6 | Overall, have changes in service provision occurred as a result of changes in: | No. of respondents | 29 (96.7) | 7 (100) | 30 (93.8) | 29 (96.7) | 95 (96) |

| Staffing | 20 (69) | 4 (57.1) | 23 (76.7) | 17 (58.6) | 64 (67.4) | ||

| Facilities | 27 (93.1) | 6 (85.7) | 29 (96.7) | 29 (100) | 91 (95.8) | ||

| Other | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 8 (27.6) | 15 (15.8) | ||

| Referrals | |||||||

| 7 | Are you accepting any nonurgent (next available routine appointment) referrals? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 32 (100) | 30 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Yes | 27 (90) | 7 (100) | 26 (81.3) | 25 (83.3) | 85 (85.9) | ||

| No | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 6 (18.8) | 5 (16.7) | 14 (14.1) | ||

| 8 | If you are accepting any nonurgent referrals, are you: | No. of respondents | 27 (90) | 7 (100) | 26 (81.3) | 24 (80) | 83 (84.8) |

| Scheduling appointments as normal | 18 (66.7) | 5 (71.4) | 20 (76.9) | 15 (62.5) | 58 (69) | ||

| Deferring appointments until service recovery | 9 (34.6) | 2 (28.6) | 7 (26.9) | 9 (37.5) | 27 (32.1) | ||

| 9 | If you are not accepting any nonurgent referrals, are you: | No. of respondents | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 7 (21.9) | 5 (16.7) | 15 (15.2) |

| Giving advice and guidance only | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (57.1) | 5 (100) | 9 (60) | ||

| Giving advice and guidance and requesting rereferral | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (33.3) | ||

| Automatic rejection (no advice) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | ||

| 10 | Are you any accepting urgent (see within 4 wk) referrals? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 32 (100) | 30 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Yes | 29 (96.7) | 7 (100) | 28 (87.5) | 27 (90) | 91 (91.9) | ||

| No | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.5) | 3 (10) | 8 (8.1) | ||

| 11 | Do you have capacity to see urgent referrals face-to-face rather than remotely? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 32 (100) | 30 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Yes | 25 (83.3) | 7 (100) | 22 (68.8) | 22 (73.3) | 76 (76.8) | ||

| No | 5 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 10 (31.3) | 8 (26.7) | 23 (23.2) | ||

Table II.

Data summarizing impact on specialist allergy services

| Question no. | Question | Subcategories | Adult allergy, n (%) | Pediatric allergy, n (%) | Total allergy, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service provision | |||||

| 1 | Did you stop VIT in any particular groups of patients (see government guidelines for definitions)? | No. of respondents | 30 (93.8) | 5 (16.7) | 35 (56.5) |

| No change—all patients continued | 3 (10) | 4 (80) | 7 (20) | ||

| Stopped in the extremely vulnerable shielded groups | 10 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 10 (28.6) | ||

| Stopped in the vulnerable stringent social distancing groups | 7 (23.3) | (0) | 7 (20) | ||

| Individual discussion with each patient | 18 (60) | 1 (20) | 19 (54.3) | ||

| All patients stopped | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.7) | ||

| Other change | 4 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (11.4) | ||

| Referrals | |||||

| 2 | Which groups of patients are you prioritizing as urgent? | No. of respondents | 30 (93.8) | 30 (100) | 60 (96.8) |

| Drug allergy—general anesthetic allergy (surgery imminent) | 23 (76.7) | 3 (10) | 26 (43.3) | ||

| Drug allergy—general anesthetic allergy (future need) | 5 (16.7) | 1 (3.3) | 6 (10) | ||

| Drug allergy—antibiotic allergy (clinically required as alternatives deemed inadequate) | 15 (50) | 5 (16.7) | 20 (33.3) | ||

| Drug allergy—chemotherapy/biologics allergy | 10 (33.3) | 2 (6.7) | 12 (20) | ||

| Drug allergy—nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug reactions | 0 (0) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (3.3) | ||

| Drug allergy—other drug allergy deemed clinically urgent | 19 (63.3) | 5 (16.7) | 24 (40) | ||

| Occupational allergy (eg, latex) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.3) | ||

| Food allergy—food-induced anaphylaxis | 13 (43.3) | 25 (83.3) | 38 (63.3) | ||

| Food allergy—nutritional concern | 5 (16.7) | 25 (83.3) | 30 (50) | ||

| Food allergy—limited diet but no nutritional concern | 2 (6.7) | 7 (23.3) | 9 (15) | ||

| Food allergy—patient choice | 0 (0) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (3.3) | ||

| Venom anaphylaxis | 14 (46.7) | 7 (23.3) | 21 (35) | ||

| Anaphylaxis, uncertain cause | 22 (73.3) | 23 (76.7) | 45 (75) | ||

| Urticaria and angioedema—spontaneous urticaria/angioedema | 6 (20) | 3 (10) | 9 (15) | ||

| Urticaria and angioedema—isolated angioedema | 3 (10) | 4 (13.3) | 7 (11.7) | ||

| Aeroallergen allergy—rhinosinusitis | 0 (0) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (3.3) | ||

| Aeroallergen allergy—rhinosinusitis with asthma | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 3 (5) | ||

| Other | 7 (23.3) | 6 (20) | 13 (21.7) | ||

| 3a | Were/are you able to undertake urgent (within 4 wk) treatments/procedures (eg, desensitizations or challenges) week commencing February 3, 2020? | No. of respondents | 30 (93.8) | 25 (83.3) | 55 (88.7) |

| Yes | 27 (90) | 21 (84) | 48 (87.3) | ||

| No | 3 (10) | 4 (16) | 7 (12.7) | ||

| 3b | Were/are you able to undertake urgent (within 4 wk) treatments/procedures (eg, desensitizations or challenges) week commencing April 5, 2020? | No. of respondents | 30 (93.8) | 25 (83.3) | 55 (88.7) |

| Yes | 15 (50) | 7 (28) | 22 (40) | ||

| No | 15 (50) | 18 (72) | 33 (60) | ||

| 3c | Were/are you able to undertake urgent (within 4 wk) treatments/procedures (eg, desensitizations or challenges) week commencing May 8, 2020? | No. of respondents | 30 (93.8) | 25 (83.3) | 55 (88.7) |

| Yes | 18 (60) | 8 (32) | 26 (47.3) | ||

| No | 12 (40) | 17 (68) | 29 (52.7) | ||

| 4 | Has there been a change to the available repertoire or turnaround time of specific IgE tests in your local laboratory? | No. of respondents | 31 (96.9) | 29 (96.7) | 60 (96.8) |

| Yes | 8 (25.8) | 7 (24.1) | 15 (25) | ||

| No | 23 (74.2) | 22 (75.9) | 45 (75) | ||

| 5 | If indicated, are you able to book skin tests for patients reviewed remotely (telephone or video consultations)? | No. of respondents | 32 (100) | 29 (96.7) | 61 (98.4) |

| <1 wk | 1 (3.1) | 4 (13.8) | 5 (8.2) | ||

| 1-4 wk | 7 (21.9) | 6 (20.7) | 13 (21.3) | ||

| By deferring to subsequent appointment (>4 wk) | 24 (75) | 19 (65.5) | 43 (70.5) | ||

Table III.

Data summarizing impact on specialist immunology services

| Question no. | Question | Subcategories | Adult immunology, n (%) | Pediatric immunology, n (%) | Total immunology, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service recovery | |||||

| 1 | Have you made changes to patient's immunoglobulin (Ig) dosing regimens as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 37 (100) |

| Yes | 20 (66.7) | 1 (14.3) | 21 (56.8) | ||

| No | 10 (33.3) | 6 (85.7) | 16 (43.2) | ||

| 2 | Have any patients discontinued Ig therapy as a result of COVID-19? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 37 (100) |

| Yes | 10 (33.3) | 2 (28.6) | 12 (32.4) | ||

| No | 20 (66.7) | 5 (71.4) | 25 (67.6) | ||

| Service provision | |||||

| 3 | Have patients been switched from hospital to home Ig therapy as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 37 (100) |

| Yes | 26 (86.7) | 2 (28.6) | 28 (75.7) | ||

| No | 4 (13.3) | 5 (71.4) | 9 (24.3) | ||

| 4 | Are home visits normally provided for routine assessment of patients on home Ig therapy? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 37 (100) |

| Yes | 18 (60) | 4 (57.1) | 22 (59.5) | ||

| No | 12 (40) | 3 (42.9) | 15 (40.5) | ||

| 5 | Has there been a reduction in home visits as a consequence of COVID-19? | No. of respondents | 17 (56.7) | 3 (42.9) | 20 (54.1) |

| Yes | 16 (94.1) | 2 (66.7) | 18 (90) | ||

| No | 1 (5.9) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (10) | ||

| Investigations | |||||

| 6 | Has there been a change in the availability of immunology laboratory investigations for the investigation of immunodeficiency? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 37 (100) |

| No change | 24 (80) | 4 (57.1) | 28 (75.7) | ||

| Longer turnaround time | 4 (13.3) | 1 (14.3) | 5 (13.5) | ||

| Fewer tests available | 2 (6.7) | 3 (42.9) | 5 (13.5) | ||

| Other | 1 (3.3) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (8.1) | ||

| COVID-19 in immunodeficiency | |||||

| 7 | Have any immunodeficiency patients from your service been diagnosed with COVID-19? | No. of respondents | 29 (96.7) | 7 (100) | 36 (97.3) |

| Yes | 22 (75.9) | 2 (28.6) | 24 (66.7) | ||

| No | 7 (24.1) | 5 (71.4) | 12 (33.3) | ||

| 8 | How many patients in your service have been diagnosed with COVID-19? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 37 (100) |

| 73 ≤ n ≤ 84 | 3 | 76 ≤ n ≤ 87 | |||

| 9 | How many COVID-19– positive patients have been reported to the COVID-19 PID data collection? | No. of respondents | 22 (73.3) | 2 (28.6) | 24 |

| 56 ≤ n ≤ 77 | 1 ≤ n ≤ 3 | 57 ≤ n ≤ 80 | |||

| Shielding advice | |||||

| 10 | Have all immunodeficiency patients in your department been risk stratified by your team according to need for “shielding”? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 37 (100) |

| Yes | 29 (96.7) | 7 (100) | 36 (97.3) | ||

| No | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.7) | ||

| 11 | How did you stratify these immunodeficiency patients according to need for “shielding”? | No. of respondents | 29 (96.7) | 7 (100) | 36 (97.3) |

| Using government guidelines or advice | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0) | 4(11.1) | ||

| No method stated | 8 (27.6) | 3 (42.9) | 11 (30.6) | ||

| Using UKPIN guideline | 17 (58.6) | 4 (57.1) | 21 (58.3) | ||

| Other stratifying method | 4 (13.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (11.1) | ||

| 12 | Did you liaise with your trust to send out “national” screening letters? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 37 (100) |

| Yes | 15 (50) | 6 (85.7) | 21 (56.8) | ||

| No | 15 (50) | 1 (14.3) | 16 (43.2) | ||

| 13 | If “no,” did you send out independent letters from your department advising shielding? | No. of respondents | 13 (43.3) | 1 (14.3) | 14 (37.8) |

| Yes | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | 13 (92.9) | ||

| No | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (7.1) | ||

PID, Primary immunodeficiency; UKPIN, United Kingdom Primary Immunodeficiency Network.

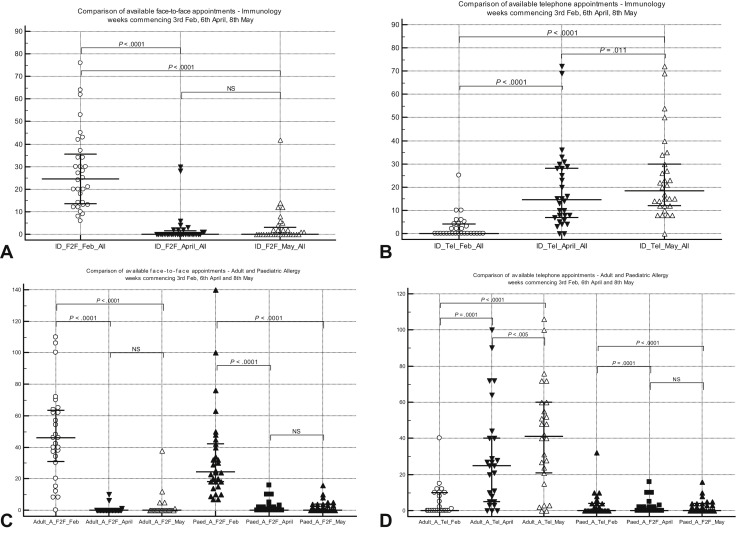

Figure 1.

(A) Comparison of face-to-face patient appointments (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points for immunology clinics. (B) Comparison of telephone patient appointments (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points for immunology clinics. (C) Comparison of face-to-face patient appointments (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points for allergy clinics. (D) Comparison of telephone patient appointments (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points for allergy clinics. IQR, Interquartile range; NS, not significant.

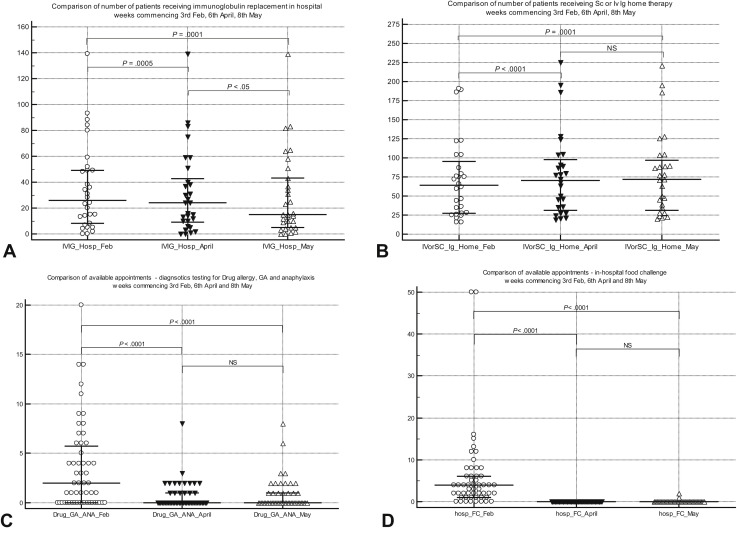

Figure 2.

(A) Comparison of hospital intravenous immunoglobulin appointments (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points. (B) Comparison of patients receiving home intravenous immunoglobulin and subcutaneous immunoglobulin (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points. (C) Comparison of general anesthetic allergy testing numbers (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points. (D) Comparison of in-hospital open food challenges numbers (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points. GA, General anesthetic; Ig, immunoglobulin; IQR, Interquartile range; Iv, intravenous; NS, not significant; Sc, subcutaneous.

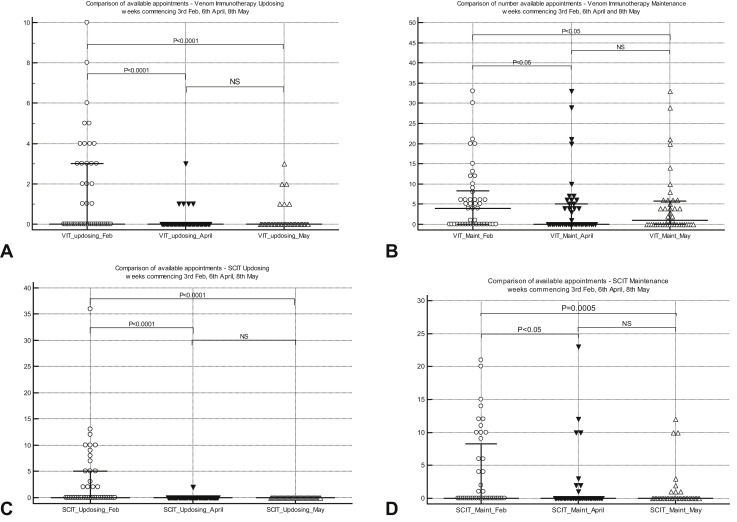

Figure 3.

(A) Comparison of VIT updosing injection appointments (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points. (B) Comparison of venom immunotherapy maintenance injection appointments (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points. (C) Comparison of subcutaneous immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis updosing injection appointments (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points. (D) Comparison of subcutaneous immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis maintenance injection appointments (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points. IQR, Interquartile range; NS, not significant.

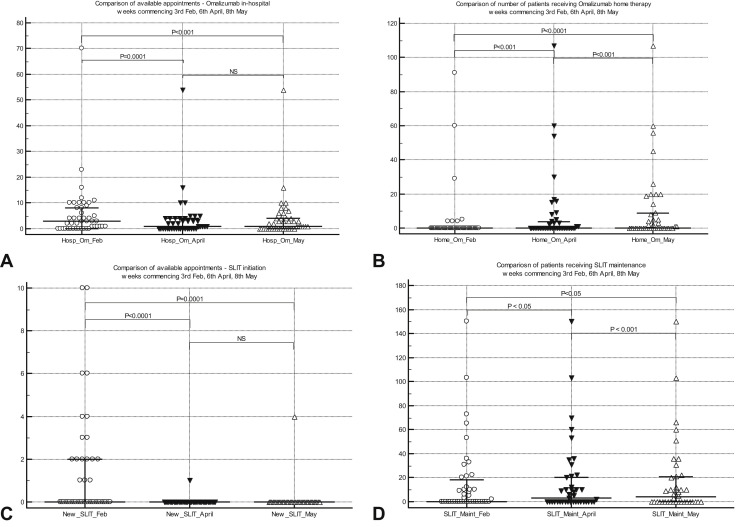

Figure 4.

(A) Comparison of in-hospital omalizumab injection appointments (median [IQR]) for chronic spontaneous urticaria for week commencing at 3 time points. (B) Comparison of patients receiving home omalizumab injection (median [IQR]) for chronic spontaneous urticaria for week commencing at 3 time points. (C) Comparison of numbers of new patient appointments (median [IQR]) for sublingual immunotherapy initiation for week commencing at 3 time points. (D) Comparison of patients receiving maintenance for sublingual immunotherapy (median [IQR]) for week commencing at 3 time points. IQR, Interquartile range; NS, not significant.

Generic questions

Staff

There was a 22% to 46%, 21% to 26%, and 15% to 41% reduction in nursing, medical, and secretarial & administrative staff, respectively, in April, which remained at a similar level in May. There was a 14% to 21% reduction in availability of dieticians, pharmacists, physiotherapists, and psychologists in April, showing a modest improvement by May. Overall, 47% of personnel in services were able to work from home, with just over a third reporting that this had no impact on service delivery.

Scheduling appointments

Eighty-five percent of services were triaging referrals pre-COVID, and a similar proportion continued during the pandemic. Eighty-six percent were still accepting “routine” nonurgent referrals, with 70% scheduling appointments as usual. The remaining services were deferring appointments until service recovery. Ninety-three percent of the latter were giving “advice and guidance,” a process involving written communication to referring physician based on the content of the referral letter. Ninety-two percent were accepting urgent referrals, with 77% offering face-to-face appointments for such referrals.

There was a highly significant reduction in face-to-face consultation involving adult and pediatric A&I services during the pandemic, with a parallel highly significant increase in telephone consultations (Figure 1). Video consultations were rarely used. Importantly, the increase in telemedicine was insufficient to meet the reduction in face-to-face attendances, leading to an overall reduction in clinic capacity.

Facilities

More than 80% of services reported that outpatient and day-case space availability was affected because of restriction imposed by the pandemic. Nearly a third of services were aware of specific patients with adverse clinical outcomes as a consequence of changes. All services who responded “yes” to adverse outcomes provided free-text comments. Adverse outcomes relating to changes in the provision of immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IgRT) included patients who did not tolerate escalated doses, an increase in anxiety in patients who discontinued immunoglobulin infusions, and some patients who felt pressured to self-administer immunoglobulin infusions at home. One center reported an increase in the rate of infection in some patients who discontinued IgRT, but no further details were provided. One pediatric center reported that lack of resources to train patients for home subcutaneous IgRT resulted in continued treatment in hospital and infections in intravenous line.

From adult allergy centers, 5 reported an inability to commence or to continue omalizumab injections, which resulted in exacerbation of CSU/A. One patient reportedly summoned paramedic crew because of an exacerbation but was not admitted to hospital. Six pediatric centers reported inability to reintroduce foods and ongoing dietary restrictions occurring as a consequence of not undertaking food challenges. Stopping VIT before completion of a full course was reported as an adverse outcome by some centers, but none reported anaphylaxis as a result. A number of centers reported that they thought it was too early to determine whether there had been adverse outcomes in this group.

Inadequate control of allergic rhinitis from not commencing SCIT or SLIT was described as an adverse clinical outcome by 1 center. A number of centers reported that an increase in waiting times for challenge testing and SCIT/SLIT would adversely impact patients. There was no report in the free text regarding admissions to hospital (although 1 child described above had a line infection as a result of not having subcutaneous immunoglobulin at home); specifically, there were no reports of anaphylaxis.

Screening patients for COVID-19

Screening for COVID-19 was implemented in a relatively small number of services in February 2020, but this clearly escalated by May 2020. This involved a questionnaire-based approach and temperature checks, with very few (3.2% of the cohort) obtaining COVID-19 swabs by May 2020. Hardly any personal protective equipment was used in February 2020, but by May 2020, the vast majority used aprons (92%) and surgical masks (99%), with a moderate proportion using eye protection (40%).

Perceived positives from changes

The respondents reported a number of positives emerging from changes made due to the pandemic, including reductions in perceived risk of infection to staff (57% of respondents) and patients (69.5%), travel time for patients (93%), patient nonattendance of appointments (54%), carbon footprint (88%), and financial overhead health service costs (34%). Fifty-nine percent reported greater flexibility of staff time; 93% and 85% of services agreed that they will not be able to return to pre-COVID service levels in outpatient and day-case units, respectively, due to changes imposed by the government with respect to social distancing.

Research activity

Thirty percent of services were not involved in research; 19% reported no change during the pandemic, 9% moved to remote research activity, and of the remaining services, 38% had all activity suspended and 3% reported reduction in activity.

Allergy specific

Specialist treatments and investigations

VIT was discontinued in nearly 50% of services in “vulnerable” and “highly vulnerable” groups (as per UK government stratification) because of restrictions related to social distancing and “shielding” (a set of extra precautions advised by the UK government to protect extremely vulnerable individuals). Although 77% of adult services regarded investigations for general anesthetic allergy (when surgery imminent) as urgent, only 10% of pediatric allergy services considered this as urgent. Similarly, 50% of allergy services considered antibiotic allergy (with alternatives deemed inadequate) to be urgent, as opposed to 17% of pediatric services. Idiopathic anaphylaxis was deemed as urgent by more than 70% of adult and pediatric allergy services. Although 83% of pediatric allergy services regarded food anaphylaxis as urgent, only 43% of adult allergy services classified this as urgent. Although more than 80% of adult and pediatric services could undertake urgent treatments such as desensitization or challenges pre-COVID, only 60% and 32% of adult and pediatric services, respectively, could do so in May 2020 during the pandemic. There was a highly significant switch from hospital-based treatment to self-administration at home for omalizumab for CSU/A during the pandemic. Similarly, there was a highly significant reduction in in-hospital food challenges and SCIT and SLIT initiation, with a significant increase in appointments offered for SLIT maintenance therapy during the pandemic (Table II and Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4).

Laboratory and skin tests

Turnaround times for laboratory investigations were not affected in 75% of services. Although all services could continue to offer skin tests when clinically indicated, only a third could offer within 4 weeks, with the remaining deferring tests for more than 4 weeks. The 4-week time point is a watershed for urgent investigations in the UK NHS framework.

Immunology specific

Immunoglobulin replacement therapy

Fifty-seven percent of services made changes (more frequent in adult services; 67% vs 14%) to dosing regimens for IgRT as a result of restrictions imposed by the pandemic, with about a third of adult and pediatric services reporting that they discontinued treatment for some patients. Seventy-six percent of services reported switching patients from hospital-based treatment to self-administration at home, more commonly in adult services than in pediatrics (87% vs 29%, although pediatric sample size was relatively small [n = 2 of 7]). Sixty percent of services offered home visits by specialist nursing staff pre-COVID, but this activity was reduced in May 2020 in 90% of centers (94% of adult centers, 67% pediatric) (Table III and Figure 2).

Immunology laboratory

Seventy-six percent of centers did not report any change in laboratory investigations for primary immunodeficiency during the pandemic, with 13.5% either reporting longer turnaround time or fewer tests.

COVID-19 cases

Seventy-six percent of adult services and 29% (2 of 7) of pediatric services reported at least 1 patient developing COVID-19.

Of note, UK pediatric immunology services are centralized in the United Kingdom; thus, the sample size of pediatric immunology services is relatively small.

Discussion

This is the first study conducted at a national level to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on A&I services. The pandemic had a significant impact on the provision of both adult and pediatric A&I services in the United Kingdom, in multiple ways affecting staffing, facilities, the modus operandi of patient review, investigations & treatment pathways, and clinical outcomes as perceived by services. However, we also identified some positive aspects arising from changes in practice during the pandemic that could improve service delivery once the pandemic is over.

A reduction was seen in medical and nursing staff availability during the study period, mostly reflecting redeployment of staff to frontline duties. A similar reduction was seen with secretarial & administrative and allied health professional staff during the study period. It is interesting to note that despite staff shortages, around 85% of services continued to triage referrals during the pandemic and importantly a similar proportion offered nonurgent appointments for patient review. New urgent referrals were accepted by more than 90% of services, with 77% able to offer face-to-face appointments, mainly focused on urgent general anesthetic allergy tests where surgery was imminent, clinically deemed important antibiotic allergy investigations, venom anaphylaxis, and food anaphylaxis. This is in keeping with recommendations recently issued by the BSACI and the American Academy of Asthma, Allergy & Immunology.11 , 12

UK government recommendations to NHS organizations to reduce patient volumes in hospitals led to a significant reduction in face-to-face consultations with a parallel increase in telephone consultations. This was seen across both adult and pediatric A&I services and is in keeping with BSACI, European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, and American Academy of Asthma, Allergy & Immunology expert panel recommendations suggesting restriction of face-to-face consultations to those with severe and uncontrolled disease and remote consultations for patients needing surveillance for mild to moderate disease.10, 11, 12 Interestingly, video consultations were not used by vast majority of services, probably due to lack of secure information technology framework with respect to clinical governance and concerns regarding use of e-devices by some patient groups. Recent reports highlight the judicious application of telemedicine in the delivery of allergy services.7 , 13 , 14 It remains unclear at present how remote consultations were conducted for patients with suboptimal proficiency in English language, although NHS trusts have access to translators. Clearly, going forward it is of paramount importance to maintain equitable access and quality of service in the black, Asian, and minority ethnic population.15 Finally, it is important for health service planning to recognize that an increase in telemedicine consultations was insufficient to fully replace the reduction in face-to-face consultations.

Staff shielding and self-isolation had an impact on 40% to 57% of A&I services, with about a third reporting that it had no significant impact on service. Outpatient and day-case space availability was significantly impacted, both due to changes in the use of facilities and 67% reporting that changes in staffing was also a contributory factor. No serious adverse events were reported because of rapid unplanned changes implemented during the study period. The reported adverse clinical outcomes were surrounding IgRT, dietary restrictions due to suspension of supervised food challenges and exacerbation of CSU/A, and inadequate control of allergic rhinitis due to either cessation or not commencing omalizumab and allergen-specific immunotherapy, respectively. This survey did not specifically explore if and what proportion of patients required short courses of corticosteroid therapy to control exacerbations of symptoms due to CSU/A.

The adverse impact on IgRT programs appeared greater in adult than in pediatric services. One-third of services discontinued IgRT in some patients, while many patients were switched to home administration, although this was associated with a reduction in home visits by immunology specialist nurses for those enrolled for the home IgRT program. The potential inconvenience caused to patients and their families due to lack of home visits by specialist nurses was not explored in depth in this study, although no serious adverse events were reported as a consequence. However, the time window for reporting such events was relatively short (∼8 weeks during the study period).

There was a highly significant decrease in general anesthetic allergy testing (routine and urgent; P < .0001), VIT updosing (P < .0001), SCIT updosing (P < .0001) and maintenance (P = .0005), hospital omalizumab administration (P < .001), and hospital oral food challenges (P < .0001) during the pandemic. A significant number of patients on omalizumab therapy were rapidly trained and switched to home administration, following the recent change in marketing authorization in the United Kingdom allowing home treatment. This is likely to be cost-effective for the NHS in the long-term, although it would be prudent to seek patient feedback, so appropriate standardized support mechanisms are put in place. No changes were detected in home oral food challenge rates between February and May. New SLIT initiation significantly decreased (P < .001) between February and May, and there was an increase in telephone consultations for those on maintenance treatment, although reasons for the latter are unclear.

Our data set is generalizable for A&I in the United Kingdom, because we had a relatively large sample size with representation from both adult and pediatric services across all geographic regions. The survey response rate for adult allergy, adult immunology, and pediatric immunology was excellent, although it was modest for pediatric allergy services. It was beyond the scope of this survey to address regarding potential confounders related to the study period. Also, even though the study included a single baseline point for comparison rather than a longer time window, the latter might have potentially introduced logistic issues in data collection and compromised quality. Although there is heterogeneity between services as described in the previous section, all UK NHS hospitals have a common generic health service framework that is set and governed centrally by the Department of Health. Although the survey was retrospective, it was launched just after the pandemic peak to maximize the quality of responses. A potential second surge16 of the pandemic during winter 2020 has been anticipated, and current changes to health service delivery may remain in place during the medium and long-term. Therefore, this data set provides evidence for strategic planning and health economic projections. Specifically, the positives that emerged from changes to practice should help shape policies going forward. In particular, remote consultations should be factored into service planning and robust standardized criteria developed with respect to patient selection for face-to-face consultations.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant adverse impact on pediatric and adult A&I services in the UK NHS. There was a significant reduction in face-to-face consultations, with a parallel increase in telephone consultation and home administration of biologic therapies, which might offer significant benefits to patients and health care providers alike in the future. It is likely that some of these changes will remain, at least in the medium term, and there is an urgent need to put in place new standards and national policies to achieve equity and standardization of care. A fit-for-purpose governance framework alongside seeking prospective feedback from patients and their caregivers regarding their perspectives should be embedded into such an approach.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Gemma Mackay and Katy Thistlethwaite in the Accreditation Unit of the RCP for administrative support. Katy Thistlethwaite collated survey responses.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: M. T. Krishna has received grants from MRC CiC, NIHR, and FSA for research unrelated to this study; received funds to attend the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology conference; and is clinical lead for the Improving Quality in Allergy Services national accreditation program. His department received funds from ALK Abello, Thermofisher, MEDA, and other pharmaceutical companies for PracticAllergy course. P. J. Turner reports grants from UK Medical Research Council, NIHR/ImperialBRC, UK Food Standards Agency, End Allergies Together, and Jon Moulton Charity Trust; personal fees and nonfinancial support from Aimmune Therapeutics, DBV Technologies, and Allergenis; personal fees and other fees from ILSI Europe and UK Food Standards Agency, outside the submitted work; and is current Chairperson of the WAO Anaphylaxis Committee, and joint-chair of the Anaphylaxis Working group of the UK Resuscitation Council. C. B. is clinical lead for the Quality in Primary Immunodeficiency Service national accreditation program. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Online Repository.

Table E1.

Data summarizing responses to generic questions

| Number | Question | Subcategories | Adult immunology, n (%) | Pediatric immunology, n (%) | Adult allergy, n (%) | Pediatric allergy, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal protective equipment (PPE) and screening | |||||||

| 1 | Screening | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 30 (93.8) | 27 (90) | 94 (94.9) |

| 1a | When patients arrive for appointments or procedures, were/are you screening for COVID-19 infection—week commencing February 3, 2020? | No screening | 14 (46.7) | 2 (28.6) | 14 (46.7) | 13 (48.1) | 43 (45.7) |

| Screening questionnaire (eg, cough and fevers) | 9 30) | 2 (28.6) | 8 (26.7) | 4 (14.8) | 23 (24.5) | ||

| Temperature measurements | 4 (13.3) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 8 (8.5) | ||

| COVID-19 swab | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| 1b | When patients arrive for appointments or procedures, were/are you screening for COVID-19 infection—week commencing April 6, 2020? | No screening | 10 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 11 (36.7) | 10 (37) | 31 (33) |

| Screening questionnaire (eg, cough and fevers) | 24 (80) | 5 (71.4) | 25 (83.3) | 17 (63) | 71 (75.5) | ||

| Temperature measurements | 18 (60) | 2 (28.6) | 21 (70) | 6 (22.2) | 47 (50) | ||

| COVID-19 swab | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| 1c | When patients arrive for appointments or procedures, were/are you screening for COVID-19 infection—week commencing May 8, 2020 | No screening | 6 (20) | 0 (0) | 10 (33.3) | 10 (37) | 26 (27.7) |

| Screening questionnaire (eg, cough and fevers) | 25 (83.3) | 4 (57.1) | 26 (86.7) | 19 (70.4) | 74 (78.7) | ||

| Temperature measurements | 19 (63.3) | 3 (42.9) | 21 (70) | 7 (25.9) | 50 (53.2) | ||

| COVID-19 swab | 1 (3.3) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.2) | ||

| 2 | PPE | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 31 (96.9) | 21 (70) | 89 (89.9) |

| 2a | For procedures with asymptomatic patients (eg, skin testing, VIT, omalizumab, challenges, and immunoglobulin) were you using the following PPE week commencing February 3, 2020? | Surgical mask (fluid- resistant) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (14.3) | 4 (4.5) |

| Filtering facepiece 3 mask | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Single-use plastic apron | 3 (10) | 2 (28.6) | 4 (12.9) | 6 (28.6) | 15 (16.9) | ||

| Long-sleeved gown | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Eye protection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| 2b | For procedures with asymptomatic patients (eg, skin testing, VIT, omalizumab, challenges, and immunoglobulin) were you using the following PPE week commencing April 6, 2020? | Surgical mask (fluid- resistant) | 28 (93.3) | 5 (71.4) | 27 (87.1) | 17 (81) | 77 (86.5) |

| Filtering facepiece 3 mask | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.4) | ||

| Single-use plastic apron | 27 (90) | 5 (71.4) | 26 (83.9) | 17 (81) | 75 (84.3) | ||

| Long-sleeved gown | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (3.4) | ||

| Eye protection | 13 (43.3) | 0 (0) | 13 (41.9) | 2 (9.5) | 28 (31.5) | ||

| 2c | For procedures with asymptomatic patients (eg, skin testing, VIT, omalizumab, challenges, and immunoglobulin), were you using the following PPE week commencing May 8, 2020? | Surgical mask (fluid- resistant) | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 31 (100) | 20 (95.2) | 88 (98.9) |

| Filtering facepiece 3 mask | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.6) | ||

| Single-use plastic apron | 28 (93.3) | 6 (85.7) | 30 (96.8) | 18 (85.7) | 82 (92.1) | ||

| Long-sleeved gown | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (3.4) | ||

| Eye protection | 14 (46.7) | 2 (28.6) | 16 (51.6) | 4 (19) | 36 (40.4) | ||

| Service provision | |||||||

| 3 | Has there been a change to out-of-hours (outside of 9 am to 5 pm, weekends, and public holidays) provision? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 32 (100) | 30 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Not applicable; no out-of- hours provision pre–COVID-19 | 18 (60) | 4 (57.1) | 26 (81.3) | 22 (73.3) | 70 (70.7) | ||

| No change (out-of-hours service continues) | 12 (40) | 3 (42.9) | 6 (18.8) | 8 (26.7) | 29 (29.3) | ||

| Out-of-hours service withdrawn as a result of COVID-19 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Research | |||||||

| 4 | Have there been changes in your research activity? | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 32 (100) | 30 (100) | 99 (100) |

| Not applicable; not involved in research pre–COVID-19 | 5 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 7 (21.9) | 18 (60) | 30 (30.3) | ||

| No change | 8 (26.7) | 2 (28.6) | 6 (18.8) | 3 (10) | 19 (19.2) | ||

| Yes, moved to remote research | 2 (6.7) | 3 (42.9) | 1 (3.1) | 3 (10) | 9 (9.1) | ||

| Yes, all research suspended | 14 (46.7) | 2 (28.6) | 17 (53.1) | 5 (16.7) | 38 (38.4) | ||

| Reduced numbers or other | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.3) | 3 (3) | ||

| Referrals | |||||||

| 5 | Referrals | No. of respondents | 30 (100) | 7 (100) | 31 (96.9) | 29 (96.7) | 97 (98) |

| 5a | Did you triage referrals pre–COVID-19? | Yes, all | 27 (90) | 6 (85.7) | 27 (87.1) | 22 (75.9) | 82 (84.5) |

| Some | 3 (10) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (9.7) | 7 (24.1) | 14 (14.4) | ||

| No, none | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | ||

| 5b | Do you triage referrals since COVID-19? | Yes, all | 27 (90) | 6 (85.7) | 29 (93.5) | 25 (86.2) | 87 (89.7) |

| Some | 2 (6.7) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (3.2) | 4 (13.8) | 8 (8.2) | ||

| No, none | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.1) | ||

References

- 1.Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Royal College of Physicians . The Royal College of Physicians; London, UK: 2003. Allergy: The Unmet Need. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warner J.O., Kaliner M.A., Crisci C.D., Del Giacco S., Frew A.J., Liu G.H. Allergy practice worldwide: a report by the World Allergy Organization Specialty and Training Council. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;139:166–174. doi: 10.1159/000090502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.House of Commons Health Committee . Stationery Office; London: 2004. The Provision of Allergy Services. Sixth Report of Session 2003–04. Volume I. HC696–I. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Efthimiou I. Urological services in the era of COVID-19. Urol J. 2020;17:534–535. doi: 10.22037/uj.v16i7.6330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez H.A., Myers S., Whitehead E., Pattinson A., Stamp K., Turnbull J. React, reset and restore: adaptation of a large inflammatory bowel disease service during COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Med (Lond) 2020;20:e183–e188. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malipiero G., Heffler E., Pelaia C., Puggioni F., Racca F., Ferri S. Allergy clinics in times of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: an integrated model. Clin Transl Allergy. 2020;10:23. doi: 10.1186/s13601-020-00333-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehanna H., Hardman J.C., Shenson J.A., Abou-Foul A.K., Topf M.C., AlFalasi M. Recommendations for head and neck surgical oncology practice in a setting of acute severe resource constraint during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e350–e359. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30334-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mack D.P., Chan E.S., Shaker M., Abrams E.M., Wang J., Fleischer D.M. Novel approaches to food allergy management during COVID-19 inspire long-term change. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:2851–2857. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brough H.A., Kalayci O., Sediva A., Untersmayr E., Munblit D., Rodriguez Del Rio P. Managing childhood allergies and immunodeficiencies during respiratory virus epidemics—the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: a statement from the EAACI-section on pediatrics. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31:442–448. doi: 10.1111/pai.13262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaker M.S., Oppenheimer J., Grayson M., Stukus D., Hartog N., Hseih E.W.Y. COVID-19: pandemic contingency planning for the allergy and immunology clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1477–1488.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology . 2020. BSACI expert panel. COVID-19: recovery of allergy and immunology services.https://wwwbsaciorg/professional-resources/bsaci-covid-19-resources/2020 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greiwe J. Telemedicine in a post-COVID world: how eConsults can be used to augment an allergy practice. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:2142–2143. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishna M.T., Knibb R.C., Huissoon A.P. Is there a role for telemedicine in adult allergy services? Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46:668–677. doi: 10.1111/cea.12701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishna M.T., Hackett S., Bethune C., Fox A.T. Achieving equitable management of allergic disorders and primary immunodeficiency in a black, Asian and minority ethnic population. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50:880–883. doi: 10.1111/cea.13698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wise J. Covid-19: risk of second wave is very real, say researchers. BMJ. 2020;369:m2294. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.