Abstract

Objectives

To assess the nature, quality and independence of scientific evidence provided in support of claims in industry-authored educational materials in oral health.

Design

A content analysis of educational materials authored by the four major multinational oral health product manufacturers.

Setting

Acute care settings.

Participants

68 documents focused on oral health or oral care, targeted at acute care clinicians and identified as ‘educational’ on companies’ international websites.

Main outcome measures

Data were extracted in duplicate for three areas of focus: (a) products referenced in the documents, (b) product-related claims and (c) citations substantiating claims. We assessed claim–citation pairs to determine if information in the citation supported the claim. We analysed the inter-relationships among cited authors and companies using social network analysis.

Results

Documents ranged from training videos to posters to brochures to continuing education courses. The majority of educational materials explicitly mentioned a product (59/68, 87%), a branded product (35/68, 51%), and made a product-related claim (55/68, 81%). Among claims accompanied by a citation, citations did not support the majority (91/147, 62%) of claims, largely because citations were unrelated. References used to support claims most often represented lower levels of evidence: only 9% were systematic reviews (7/76) and 13% were randomised controlled trials (10/76). We found a network of 20 authors to account for 37% (n=77/206) of all references in claim–citation pairs; 60% (12/20) of the top 20 cited authors received financial support from one of the four sampled manufacturers.

Conclusions

Resources to support clinicians’ ongoing education are scarce. However, caution should be exercised when relying on industry-authored materials to support continuing education for oral health. Evidence of sponsorship bias and reliance on key opinion leaders suggests that industry-authored educational materials have promotional intent and should be regulated as such.

Keywords: oral medicine, medical ethics, health policy, health services administration & management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We sampled all documents explicitly labelled as ‘educational’ from the websites of the four major manufacturers of oral care products.

All data were extracted in duplicate and judgements about whether evidence substantiated a claim was made by two independent reviewers.

We included a novel evaluation of the independence of the cited evidence by assessing relationships among cited authors and the manufacturers.

We do not know whether or how these educational materials are used by clinicians and thus the impact on practice is unknown.

Introduction

Industry continues to be a major source of sponsorship of clinicians’ continuing education in the form of conferences, dinner meetings, journal clubs, grand rounds and trainings.1 2 Nurses frequently rely on industry representatives and information for guidance on product use and outcome evaluation in the practice setting.3–5 Products commonly used in nursing care, such as wound dressings, often lack high-quality clinical trials demonstrating efficacy prior to market approval.6 7 Thus, manufacturers are often a principle—or sole—source of information about nursing-related products.

However, information communicated to health professionals about pharmaceuticals and devices in the form of product advertisements often fails to provide adequate safety information, or to communicate an appropriate balance between benefits and harms.8–10 Less is known about the nature, quality or impact of industry-authored materials that are characterised as ‘educational.’ Educational materials in many jurisdictions are not subject to the same regulation as advertising, thus, may not undergo regulatory review for inclusion of appropriate safety information, for example.11 Thus, the goal of this study was to evaluate the nature and quality of industry-authored educational materials from the perspective of evidence-based practice.

We selected oral health in acute care settings as the case study for this analysis for three reasons. First, oral diseases affect over half of the world’s population, including untreated dental caries, which globally, is the most prevalent health condition.12 Second, oral health represents an opportunity to examine a variety of commercial determinants of health as it is characterised largely by a downstream, interventionist and technology-focused approach.13 Third, inadequate oral hygiene represents a serious risk factor for healthcare-acquired pneumonia, which is an important source of morbidity, mortality and growing healthcare costs.14 Thus, there is increased interest by hospital administrators and health systems in addressing patients’ oral health, which has placed a spotlight on the selection and use of efficacious tools and pharmaceuticals for oral care.

Consequently, nurses face increasing expectations to deliver safe and effective oral care.14 15 Oral care is a fundamental care practice for which nurses are primarily accountable and occurs within complex clinical and technical environments in order to prevent associated adverse health and quality of life outcomes including pneumonia, painful oral diseases such as periodontitis and tooth loss.14 16 17 However, nurses consistently experience insufficient pre-licensure and post-licensure education in oral healthcare,18 which is consistent with the siloing of oral health by health systems, policymakers and medicine more broadly.13 Given these educational gaps, in this content analysis, we focus on educational materials authored by the manufacturers of products used to perform oral care in acute care hospital settings including toothbrushes, foam swabs, lip moisturiser, oral rinses and oral suction (see online supplemental table 1). We aimed to assess the nature, quality, and independence of scientific evidence provided in support of product-related and practice-related claims.

bmjopen-2020-040541supp001.pdf (115.4KB, pdf)

Materials and methods

Design and sampling frame

We identified manufacturers of oral care products (see online supplemental table 1) through expert consultation (CMD), previous research on nurse-industry interactions,4 Google searches for oral care product brands and examination of the regulatory filing (SEC 10-K form) for the dominant manufacturer (Sage), which identified the major competitors in the company’s medical division. We excluded companies that were at the start-up phase or supported exclusively through grants, and that only distributed and did not manufacture oral health products. Our sampling frame thus included educational materials authored by:

Sage Products (publicly traded manufacturer, a subsidiary of Stryker, a Fortune 500 company, USA, manufacturer of Q·Care Oral Cleansing & Suctioning Systems).

Medline Industries (privately held manufacturer and distributor, USA, manufacturer of Medline brand toothbrushes, swabs, Yankauers, mouthwashes and DenTips Oral Swabsticks).

Intersurgical (privately held manufacturer, UK, manufacturer of OroCare 24-hour day kits).

Avanos (publicly traded manufacturer, USA, manufacturer of Ballard Oral Care kits).

Data sources

Two investigators independently sampled all educational materials from the four companies’ international websites; thus, all content was in English. We defined ‘educational material’ as documents produced and authored by the company, focused on oral health conditions and/or care practices, targeted at clinicians, and explicitly identified as ‘educational’ (eg, located under website headers ‘clinical education,’ or identified as a ‘course’ or ‘training’). There were no restrictions on document format. We captured screenshots of all included web pages and downloaded all available PDFs. Two investigators independently screened the full texts of sampled documents according to these inclusion criteria with a third investigator reviewing any discrepancies. We excluded documents if they were required by a regulator (eg, Material Data Safety Sheet), intended for purchasing (eg, catalogue, order form), hosted and/or authored exclusively by a third party, or targeted patients, family caregivers or clinicians working outside of acute care (eg, dentists).

Data extraction

Based on previous analyses of evidentiary support for promotional claims in pharmaceutical and medical device advertising,8 9 19 we created a data extraction tool in REDcap20 that comprised three main sections: identification of products, identification and assessment of product-related claims, and identification and assessment of supporting evidence. Identification of products included assessing the number and type of unique products mentioned or depicted. We extracted all product-related or practice-related claims, defined as statements made about the efficacy, safety, cost-effectiveness, convenience, or other value of an oral care product (eg, toothbrush) or clinical practice involving a product (eg, toothbrushing), along with any accompanying citation(s). We distinguished product-related claims from normative claims, which suggested what should or must be done, but did not refer to effectiveness, for example.

We categorised claims using an adapted typology from a previous investigation of pharmaceutical advertisements8: unambiguous (ie, clinical comparison or outcome that is clear and measurable); vague or non-clinical (ie, lacks a comparison, clear efficacy outcome or clinical outcome); process-related (ie, related to workflow, convenience or compliance concerns); and emotive/immeasurable (ie, evoked feelings and no measurable outcome identified) and noted whether the claim contained risk reporting.

We extracted all citations, then classified citations accompanying claims by type (eg, journal article, conference abstract, data on file) and level of evidence according to the criteria for treatment efficacy from the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.21 We determined whether a citation identified a primary outcome and data were extracted on the citation’s funding sources and author conflicts of interest.

We piloted the instrument on a subset of sampled documents until we reached an acceptable level of agreement. Two investigators then independently extracted data on the entire sample; discrepancies were discussed and resolved with a third author.

Data analysis

Two independent investigators assessed claim–citation pairs, which involved a claim and accompanying citation, to determine if information in the citation supported the claim). Investigators classified citations deemed ‘unsupportive’ according to an adapted classification from a study of claim–citation pairs in wound care advertising,9 choosing the reason that best described why the citation was unsupportive. Reasons included: the citation was unrelated in terms of content, study population or intervention; exaggeration of benefits; citation reported an in-vitro or animal study; distorted reporting of study findings (eg, the claim was not based on the study’s primary outcome, the study findings were not statistically significant or the citation did not meet an appropriate level of evidence for the accompanying claim) or cited data were unpublished (eg, ‘data on file’). We calculated descriptive statistics on all frequencies and proportions using SPSS V.25.

Network analysis

In addition to the level and quality of evidence used to substantiate claims, we assessed the independence of the evidence presented using social network analysis. We sought to analyse two facets of independence: (1) the degree to which industry-authored educational materials cited the work of authors who work independently from one another (ie, authors who are not coauthors); and (2) the extent of referenced authors’ relationships with the sampled companies and industry more broadly.

We manually extracted the listed authors and coauthors for all publications referenced in the sample, excluding sampled documents with no citations and non-authored citations (eg, data on file, federal register, no listed authors). We calculated the number of times each publication was cited in substantiation of a claim and the number of times each publication was cited overall. Then, we ranked authors by the number of cited publications they authored or coauthored in substantiation of a claim. To analyse the interdependence of authors, we derived the network of coauthorship relations derived from these references.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in this study.

Results

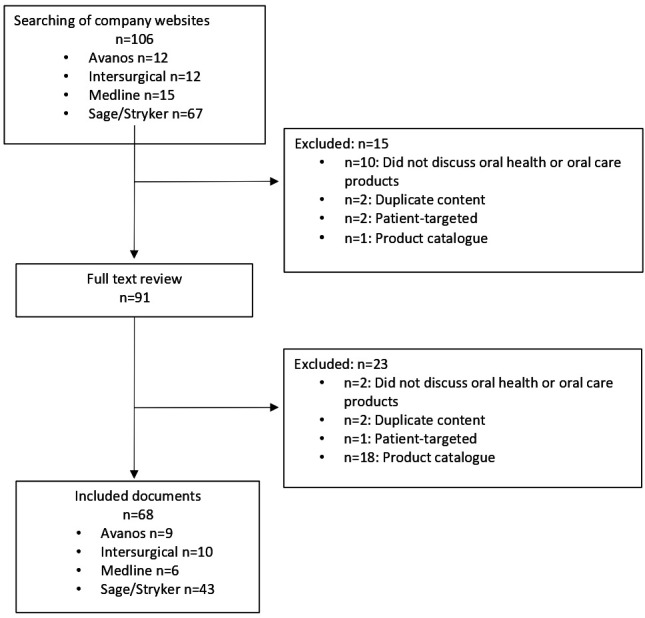

We included 68 documents from the four manufacturers (figure 1). Nearly 2/3 (43/68, 64%) were authored by Sage (owned and operated by Stryker Corporation), the dominant manufacturer in this market. Document characteristics are outlined in table 1. Sampled documents included brochures, flyers, web pages and courses containing information about oral care (eg, ‘Evidence-based practices for comprehensive oral care workshop’), oral disease (eg, ‘Colonisation of dental plaque and importance of brushing for hospitalised patients’), or sequelae of missed oral care or oral disease (eg, ‘Protecting your patients from ventilator-associated pneumonia’). Sampled documents also included templates for educational posters, and oral care assessment or care protocols designed to be customised by users. The majority of documents mentioned an oral care product (59/68, 87%) and 51% mentioned a branded oral care product (35/68), which included pharmaceuticals (eg, oral rinse), medical devices (eg, toothbrushes, suction devices) or pre-packaged kits containing a combination of oral care products and pharmaceuticals (online supplemental table 1). The majority of documents contained at least one product-related claim (55/68, 81%). We extracted 252 claims across the sampled documents; however, claims frequently recurred verbatim across the 68 documents, resulting in 204 unique claims (204/252, 79%).

Figure 1.

Industry-authored educational materials sampling flow diagram (n=68).

Table 1.

Characteristics of industry-authored educational materials (n=68)

| Variable | Sage n (%) | Intersurgical n (%) | Avanos n (%) | Medline n (%) | Total n (%) |

| No of documents | 43 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 68 |

| Document format | |||||

| Brochure, flyer, webpage | 31 (72) | 8 (80) | 8 (89) | 4 (67) | 51 (75) |

| Protocol template | 7 (16) | 2 (20) | 0 | 0 | 9 (13) |

| Course (accredited) | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (11) | 2 (33) | 5 (7) |

| Course (non-accredited) | 2 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3) |

| Other* | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| No with product mentions | 36 (84) | 8 (80) | 9 (100) | 6 (100) | 59 (87) |

| No of branded† mentions | 22 (51) | 5 (50) | 5 (56) | 3 (50) | 35 (51) |

| No of pharmaceutical mentions | 22 (51) | 7 (70) | 4 (44) | 2 (33) | 35 (51) |

| No of device mentions | 28 (65) | 5 (50) | 4 (44) | 2 (33) | 39 (57) |

| No of combination kit mentions‡ | 20 (47) | 5 (50) | 6 (67) | 4 (67) | 35 (51) |

| No with product-related claims | 34 (79) | 7 (70) | 8 (89) | 6 (100) | 55 (81) |

*Other format was a webpage containing information about a ‘customer information department’.

†‘Branded’ mentions were those that referenced a product’s specific brand name.

‡Pre-packaged kits containing a combination of oral care products and pharmaceuticals.

Evidentiary support for claims

The majority of claims (124/204, 61%) referred to an outcome that was vague and/or non-clinical (see table 2). Only 12% (24/204) of claims contained risk reporting; on examination of the accompanying citation, we determined the majority of claims containing risk reporting (18/24, 75%) reported relative risk, while 6 (25%) did not present sufficient information to determine the type of risk reporting.

Table 2.

Nature of outcome reporting in claims

| Type of outcome referenced in claim (n=204) | n (%) | Examples |

| Vague and/or non-clinical | 124/204 (61) | ‘The BALLARD turbo-cleaning catheter is the only catheter that retracts within a unique isolated turbulent cleaning chamber, which results in a cleaner catheter tip compared with a standard closed suction system.’ ‘Our oral care products are designed to help promote oral health to address the risk of hospital acquired pneumonia.’ ‘Oral care given q2–q4 appears to provide greater improvement in oral health.’ |

| Unambiguous and clinical | 39/204 (19) | ‘A published 4-year study using an oral care protocol including Toothette Oral Care Systems saw… fewer vent days, shorter length of stay and decreased mortality rates.’ ‘A 2-year study at 11 nursing homes found pneumonia risk was significantly reduced in patients receiving oral care. In fact, mortality due to pneumonia was about half that of patients not receiving oral care.’ ‘Two times per day application of 2% and 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate to the oral cavity with a 2-hour time period from brushing has reduced VAP rates.’ |

| Process-related | 35/204 (17) | ‘New space-saving design and bedside bracket help improve compliance.’ ‘The Sherpa Suction System ensures 100% of all ICU-ventilated patients have daily access to above-the-cuff suctioning.’ ‘Product ease-of-use resulted in my ability to provide more frequent oral cleansing.’ ‘OroCare day kits: ensuring compliance with hospital guidelines for VAP prevention.’ |

| Emotive or immeasurable | 6/204 (3) | ‘We are preventing pneumonia and saving lives, one clean mouth at a time.’ ‘Tooth brushing is essential component of oral care.’ ‘Oral hygiene is critical in the fight against VAP with good brushing techniques and suctioning being important tools.’ ‘Data-driven best practices for oral care may allow healthcare providers to protect ventilated patients with a higher level of confidence.’ |

ICU, intensive care unit; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Of the 204 unique claims, 56% (115/204) were accompanied by one or more citations, resulting in 147 unique claim–citation pairs. For the majority of claim–citation pairs, we judged the claim to be unsupported by the accompanying citation (91/147, 62%). Most often, citations did not provide adequate support for the claim because citations were unrelated in terms of content focus, study population or intervention; the underlying evidence was inaccessible to a frontline clinician; or claims exaggerated the benefits of the cited findings. Table 3 provides illustrative examples of citations that provided insufficient support to claims.

Table 3.

Nature of evidentiary support or non-support of claims

| Reasons citation was unsupportive (n=91) | n (%) | Example claim | Accompanying citation | Explanation* |

| Citation unrelated to claim | 25 (27) | ‘One facility had a VAP rate of zero for 3 straight years after implementing an oral care protocol that included Q care systems.’ | Quinn, B. et al. Basic nursing care to prevent nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia, J Nurs Scholarsh, 2014, 46:1, 11–19. | The cited study examines prevention of non-ventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia, while the claim cited improvements in ventilator-associated pneumonia. |

| ’Toothette SuctionToothbrush: Helps remove dental plaque, debris and oral secretions, all known to harbour potential respiratory pathogens.’ | Pearson LS, Hutton JL, J Adv Nurs. 2002 Sep;39(5):480–9 | The cited study compared toothbrushes (not suction toothbrushes) and foam swabs. | ||

| ‘Pneumonia risk can be significantly reduced by performing oral care. In a 2-year study, mortality due to pneumonia was about half that of patients not receiving oral care.’ | Yoneyama, T., Yoshida, M., Ohrui, T., Mukaiyama, H., Okamoto, H., Hoshiba, K.,… & Mizuno, Y. (2002). Oral care reduces pneumonia in older patients in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(3), 430–433. | The document containing the claim is targeted at oral care in adult acute care, however, the citation reports research conducted in a long-term care facility. | ||

| ‘Having set oral care protocols that are followed by healthcare personnel may help decrease poor oral health outcomes of patients, thus improving overall health.’ | Handa, S., Chand, S., Sarin, J., Singh, V., & Sharma, S. (2014). Effectiveness of oral care protocol on oral health status of hospitalised children admitted in intensive care units of selected hospital of Haryana. Nursing and Midwifery Research Journal, 10(1), 8–15. | The document containing the claim is targeted at oral care in adult acute care populations, however, the citation reports findings from a study of hospitalised children. | ||

| Distorted interpretation of citation findings | 24 (26) |

‘Oral care removes microbes and is proven to significantly reduce NV-HAP.’ | Quinn, B., & Baker, D. (2015). Comprehensive oral care helps prevent hospital-acquired nonventilator pneumonia. American Nurse Today, 10(3), 18–23. | The claim implies causality but cites a narrative review. |

| ‘A published 4-year study using an oral care protocol including Toothette Oral Care Systems saw a 33% reduction in VAP, plus fewer vent days, shorter length of stay and decreased mortality rates.’ | Garcia et al. Reducing ventilator-associated pneumonia through advanced oral-dental care: A 48-month study. Am J Crit Care. 2009;18(6):523–532. | The cited pre/post (non-randomised) study states, ‘During the intervention period, VAP rates decreased by 33.3%, although the result was only marginally significant (12 vs 8 cases per 1000 ventilator days, p=0.06).’ | ||

| ‘Maintaining oral hygiene has been proven to help reduce healthcare-acquired pneumonias (HAPs), including ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and aspiration pneumonia.’ | Vollman K, Garcia R, Miller L, AACN News. Aug 2005;22(8):12–6. | The claim implies causality but cites an observational study. | ||

| Exaggerated benefits | 21 (23) | ‘Intervention led to 89.7% reduction in VAPs from 2004 to 2007.’ | Hutchins et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia and oral care: A successful quality improvement project. Am J Infect Contr. 2009;37(7):590–597 | Citation is a quality improvement study, with no control group, which stated ‘the ventilator bundle and an oral care protocol intervention with cetylpyridinium chloride (changed to 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate in January 2007) and hydrogen peroxide… may have led to the 89.7% reduction in the rate of VAP in mechanically ventilated patients from 2004 to 2007.’ |

| ‘In one study, Continue Care led to $1 720 000 in avoided costs and 500 extra hospital days averted.’ | Quinn, B., Baker, D. L., Cohen, S., Stewart, J. L., Lima, C. A., & Parise, C. (2014). Basic nursing care to prevent nonventilator hospital‐acquired pneumonia. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 46(1), 11–19. | Findings were due to the implementation of an ‘enhanced oral care nursing protocol’ (including provider education, protocol, improved equipment). Continue Care products were also not explicitly mentioned in the article although it was stated that the authors received an unrestricted grant from Sage. | ||

| ‘Oral care removes microbes and is proven to significantly reduce NV-HAP.’ | Fox J, Frush K, Chamness C, et al. (2015). Preventing Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP) Outside of the Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Bundle. Prevention Strategist, 3, 45–48. | The citation does not provide any statistics nor raw data to be able to interpret the significance of the results. | ||

| Evidence cited not accessible for verification | 21 (23) | ‘Clinician success at delivery of a suction catheter to ETT cuff: 99% with Sherpa Suction Guide, 0% with suction catheter alone.’ | Clinician experience in simulated test models, Data on File at Ciel Medical | Data on file with the manufacturer and not publicly available. |

| ‘Mechanically ventilated patients are at a particularly high risk of pneumonia even after discharge. Yet oral care protocols have been shown to make a positive difference in ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) risk.’ | Lloyd, R. Oral care of the mechanically ventilated patient: You can make a difference in 5 min.(cited at the State of Illinois Critical Care Conference). March, 2002. | Citation is a conference poster with insufficient detail to assess methods or results. | ||

| ‘Antiseptic Oral Rinse: Helps reduce chance of infection in minor oral irritation…(and) promotes healing by reducing bacteria known to cause most oral dysfunction.’ | Nisengard RJ, Dept of Periodontics & Endodontics, Sch of Dent Med, SUNY Buffalo, 2000 Dec. | Citation refers to an individual and not a study. | ||

| Study in-vitro or in animals | 0 |

*All bolded text has been bolded by authors for emphasis.

Nature and level of evidence

Documents referenced a mean 6.62 citations (SD=11.89). We extracted 437 citations from the 68 documents; 31% of the citations (134/437) appeared in multiple documents, resulting in 303 unique citations in the sample of 68 documents (table 4). However, the majority of unique citations (71%, 215/303) accompanied statements unrelated to oral health or general statements of fact (eg, ‘Every 4–6 hours 20 billion bacteria duplicate in the oral cavity’). Only 29% (88/303) of unique citations occurred as part of a claim–citation pair. We were unable to identify or access the full text of 14% (12/88) because citations were incomplete (eg, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses Manual, 2015) or data were unpublished (eg, data on file with manufacturer, presentation abstracts and proprietary reports). Thus, we categorised 76 citations by level of evidence. Cited studies generally represented lower levels of evidence: less than 20% were systematic reviews (7/76, 9%) or randomised controlled trials (10/76, 13%). About half the cited studies provided a conflict of interest statement (43/76, 57%) and/or a funding statement (36/76, 47%). Of the cited studies that made such disclosures, 23% (10/43) disclosed financial relationships between authors and oral health product manufacturers, 33% (12/36) reported industry sponsorship of the study; two studies reported both author conflicts of interest and industry funding for the study.

Table 4.

Characteristics of cited studies

| Variable | n (%) |

| Total citations (n=68 documents) | 437 |

| Total unique citations | 303/437 (69) |

| Number of unique citations accompanying claims | 88/303 (29) |

| Unique citations with full text accessible | 76/88 (86) |

| Full text not accessible* | 12/88 (14) |

| Type of unique reference with full text accessible (n=76) | |

| Journal article | 51/76 (67) |

| Other† | 16/76 (21) |

| Poster | 5/76 (7) |

| Clinical practice guideline | 4/76 (5) |

| Level of evidence (n=76) | |

| Systematic review | 7/76 (9) |

| Randomised controlled trial | 10/76 (13) |

| Observational study | 28/76 (37) |

| Opinion | 24/76 (32) |

| Narrative review | 4/76 (5) |

| Other‡ | 2/76 (3) |

| Mechanistic | 1/76 (1) |

| References with conflict of interest statement (n=76) | 43/76 (57) |

| Presence of conflict of interest with oral health product manufacturer | 10/43 (23) |

| References with funding statement (n=76) | 36/76 (47) |

| Study funded by oral health product manufacturer | 12/36 (33) |

*Incomplete citations or unpublished data (eg, data on file with manufacturer, presentation abstracts and proprietary reports).

†Policy documents, organisational web pages, non-peer-reviewed magazines and textbooks.

‡Regulatory documents (eg, Food and Drug Administration notice of rulemaking).

Independence of evidence

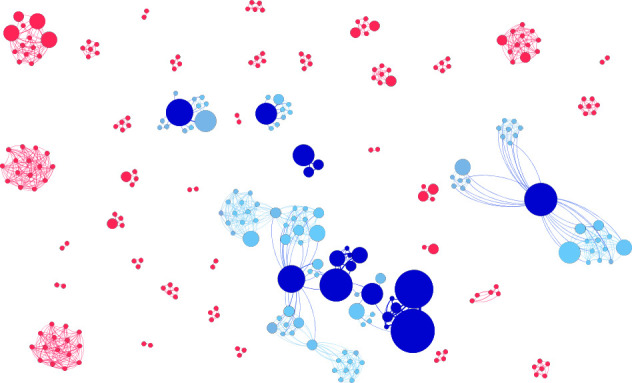

We identified 796 unique authors of citations referenced in the sampled documents; 38% (304/795) were authors of citations used to substantiate a claim. Using social network analysis, we examined the degree to which authors of citations accompanying claims were independent from one another (ie, authors who are not coauthors). Within sampled documents, a small group of individuals authored and coauthored a disproportionate number of citations used to substantiate claims.

Figure 2 displays the coauthor network derived from citations used to substantiate a claim within sampled documents. The nodes represent individual authors, joined by ties that indicate they coauthored at least one citation in the sample. The size of the node represents the number of citations the individual authored within the sample that were used to substantiate claims. Nodes coloured dark blue highlight the top 20 authors ranked by the number of citations; light blue nodes indicate authors that are directly or indirectly linked (through shared coauthors) to the top 20 authors.

Figure 2.

Network of authors and coauthors referenced by claims: the nodes represent individual authors, joined by ties that indicate coauthorship. The size of the node represents the number of citations the individual authored within the sample that were used to substantiate claims. Nodes coloured dark blue highlight the top 20 authors ranked by the number of citations; light blue nodes indicate authors that are directly or indirectly linked (through shared coauthors) to the top 20 authors.

These top 20 authors occupied central positions in the network, connecting and collaborating with many of the author groups whose work companies cited to provide an evidence base for the educational materials. The top 20 authors (in terms of the number of times their authored or coauthored citations were used to substantiate a claim) represented 2.5% of all authors in the overall sample of cited authors (20/796). Collectively, they accounted for 37.4% of all citations used within claim–citation pairs (n=77/206, including claim–citation pairs repeated across documents) (table 5).

Table 5.

Characteristics of top 20 authors

| Characteristic | N | % |

| Citations within sample by top 20 authors* | 270/437 | 62 |

| Citations accompanying claims by top 20 authors* | 77/206 | 37 |

| Author discipline (n=20) | ||

| Nursing | 11 | 55 |

| Infection control | 3 | 15 |

| Medicine | 3 | 15 |

| Dentistry | 1 | 5 |

| Epidemiology | 1 | 5 |

| Disclosures (n=20) | ||

| Study funding | ||

| From oral health manufacturer† | 9 | 45 |

| Use of professional medical writer‡ | 6 | 30 |

| Personal payments | ||

| From oral health manufacturer† | 8 | 40 |

| From other industry | 3 | 15 |

| Both study funding and personal payments from oral health manufacturer† | 5 | 25 |

| Any financial relationship with oral health manufacturer† | 12 | 60 |

| No financial ties to industry | 1 | 5 |

*Authorship included principal, senior and coauthorship.

†Included companies producing the educational materials (ie, Sage Products, Avanos, Intersurgical, Medline Industries).

‡Authors disclosed using the services of a professional medical writer, but otherwise did not disclose the source of study funding.

We investigated the industry ties of these top 20 authors (table 5). Overall 60% (12/20), including the top five authors, had at least one financial relationship with one of the four sampled oral health product manufacturers, which included receipt of personal payments for speaking or consulting and/or study funding. Among these top 20, only 1 author (5%) had no financial ties to industry.

Discussion

Oral health product manufacturers authored a wide range of educational materials targeted at nurses ranging from product training videos to courses. However, these educational materials may be largely characterised as ‘education in support of a product’4: the majority mentioned an oral health product, half mentioned a branded product and over 80% made a product-related claim. Given that oral health is the product of a complex interplay among social (eg, socioeconomic status, marginalisation, access to dental care) and commercial determinants (eg, promotion of high-sugar products),12 the educational focus on product-related practices suggests a downstream approach to oral health and may constitute an agenda bias in educational content and the underlying research.22

Educational materials authored by these companies presented as evidence-based, containing on average nearly seven citations per document and suggested they represented the findings of curated scientific literature (ie, titles such as ‘What the Experts Say’). Just over half of the unique claims (115/204, 56%) were accompanied by a citation and the majority were not substantiated by the underlying evidence. In general, sampled documents presented a low level of evidence and relied heavily on narrative reviews or opinion pieces; however, most claims related to vague or non-clinical outcomes, thus, the level of evidence required to support such statements is also lower. Commonly, claims presented a distorted interpretation or exaggerated the benefits of the accompanying evidence, which constitutes a form of ‘spin,’ defined as reporting practices that mislead readers by presenting results in a more favourable light.23

The companies relied on a small network of oral health experts in marshalling evidence in support of claims and educational materials more generally, many of whom had existing or subsequent financial ties to the companies or industry more broadly. These recognised and respected experts are examples of key opinion leaders, who are engaged by pharmaceutical or medical device companies as speakers or consultants for their ability to influence their peers.24 Companies may also approach key opinion leaders to serve as investigators on company-sponsored projects or as authors on company-led research.25 Key opinion leaders are valuable to companies because they project an appearance of independence and integrity, while serving as ‘product champions’; however, companies carefully manage key opinion leaders, including nurses, physicians and scientists, through training programmes and by offering targeted research funding, speaking platforms and authorship opportunities.24

Companies also sponsored or were involved in nearly half of the highly cited studies suggesting sponsorship bias, where industry funding is associated with results and conclusions favourable to the sponsor,26 may also be of concern. Regardless of the educational value and integrity of the underlying research, our network analysis illustrates how companies can strategically cite, often repeatedly, and thus amplify, perspectives that are favourable to commercial aims. This may be another facet of sponsorship bias consistent with previous research that found articles with positive conflict of interest disclosures are more likely to be published in high-impact journals or to receive more media attention.27

Consequently, industry-authored educational should be characterised as ‘promotional’ and regulated as advertising. Regulators have issued industry guidance to enable assessment of the distinction between ‘promotional’ and ‘non-promotional’ activities, which includes assessing whether materials directly or indirectly promote the sale of a health product and whether the manufacturer or sponsor has influence over the content.11 28 In practice, however, medical device industry-authored educational materials likely receive little regulatory scrutiny. Though certain high-income countries such as Canada, Australia, the USA and the European Union have specific laws that govern pharmaceutical and medical device advertising, these regulators are under-resourced and most jurisdictions rely on voluntary, industry self-regulation through codes of practice to regulate promotion.29 30

Strengths and limitations

We analysed a purposive sample of publicly available educational materials sampled from the websites of four manufacturers of oral health products. It is unknown whether these documents are representative of those produced by other oral health manufacturers, nor whether these findings can be generalised to other product categories. However, the sampled companies are market leaders and two (Sage and Medline) have diverse product portfolios suggesting that these findings may be indicative of industry-authored educational materials more broadly. We sampled educational documents targeting nurses from company websites, thus it is unknown whether and how these educational materials are used and their impact on educational or clinical outcomes. Identifying educational materials and extracting claims required interpretation, thus we opted for duplicate sampling and data extraction at all stages.

Conclusion

The sustainability of health systems worldwide is under strain and resources to support nurses’ ongoing practice-based education are scarce. The findings of this study, however, suggest that caution should be exercised when relying on industry-authored educational materials to support product training and continuing clinical education in oral health and in clinical practice, more broadly. To support the use of oral health products in clinical practice, clinicians should seek industry-authored materials that conform to regulatory standards related to labelling (ie, instructions for use) and otherwise, seek education that is independent from manufacturers.

The findings of this study call into question whether industry-authored materials are educational or promotional, which carries regulatory implications. Evidence of sponsorship bias affecting the focus, substantiation of claims and curation of expert recommendations suggests that industry-authored educational materials have promotional intent and should be regulated as such.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @QuinnGrundy, @craig_dale1

Contributors: QG conceived the study, acquired funding, supervised all aspects of the work and wrote the first draft; AM and CC conducted sampling, data collection and analysis, and critically revised the manuscript; FH conducted network analyses, performed data visualisation and critically revised the manuscript; CMD contributed to study design, supervised all aspects of the work and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Bloomberg Summer Research Scholarship (no award number) from the Lawrence S Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing at the University of Toronto, the Connaught New Researcher Award (no award number) from the University of Toronto and the Toronto Mobility Scheme (no award number) from the University of Sydney’s Office of Global Engagement.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The full dataset is available as a CSV file from the authors upon reasonable request.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Fabbri A, Grundy Q, Mintzes B, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of pharmaceutical industry-funded events for health professionals in Australia. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016701. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeJong C, Aguilar T, Tseng C-W, et al. Pharmaceutical industry-sponsored meals and physician prescribing patterns for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1114–22. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jutel A, Menkes DB. "But doctors do it…”: nurses' views of gifts and information from the pharmaceutical industry. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:1057–63. 10.1345/aph.1M027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy Q. Infiltrating healthcare: how marketing works underground to influence nurses. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madden M, Stark J. Understanding the development of advanced wound care in the UK: interdisciplinary perspectives on care, cure and innovation. J Tissue Viability 2019;28:107–14. 10.1016/j.jtv.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodgson R, Allen R, Broderick E, et al. Funding source and the quality of reports of chronic wounds trials: 2004 to 2011. Trials 2014;15:19. 10.1186/1745-6215-15-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lockyer S, Hodgson R, Dumville JC, et al. "Spin" in wound care research: the reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically non-significant primary outcome results or unspecified primary outcomes. Trials 2013;14:371. 10.1186/1745-6215-14-371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Othman N, Vitry A, Roughead EE. Quality of pharmaceutical advertisements in medical journals: a systematic review. PLoS One 2009;4:e6350. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumville JC, Petherick ES, O'Meara S, et al. How is research evidence used to support claims made in advertisements for wound care products? J Clin Nurs 2009;18:1422–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02293.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diep D, Mosleh-Shirazi A, Lexchin J. Quality of advertisements for prescription drugs in family practice medical journals published in Australia, Canada and the USA with different regulatory controls: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e034993. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canada H. The distinction between promotional and non-promotional messages and activities for health products: draft guidance document. Ottawa, Canada: Health Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet 2019;394:249–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watt RG, Daly B, Allison P, et al. Ending the neglect of global oral health: time for radical action. Lancet 2019;394:261–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31133-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dale CM, Angus JE, Sinuff T, et al. Ethnographic investigation of oral care in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care 2016;25:249–56. 10.4037/ajcc2016795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sjögren P, Wårdh I, Zimmerman M, et al. Oral care and mortality in older adults with pneumonia in hospitals or nursing homes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:2109–15. 10.1111/jgs.14260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanne K, Ingelise T, Linda C, et al. Oral status and the need for oral health care among patients hospitalised with acute medical conditions. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:2851–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dale CM, Smith O, Burry L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of difficulty accessing the mouths of intubated critically ill adults to deliver oral care: an observational study. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;80:36–40. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rello J, Koulenti D, Blot S, et al. Oral care practices in intensive care units: a survey of 59 European ICUs. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:1066–70. 10.1007/s00134-007-0605-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villanueva P, Peiró S, Librero J, et al. Accuracy of pharmaceutical advertisements in medical journals. Lancet 2003;361:27–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12118-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine - Levels of evidence, 2009. Available: https://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/ [Accessed 12 Nov 2019].

- 22.Fabbri A, Lai A, Grundy Q, et al. The influence of industry sponsorship on the research agenda: a scoping review. Am J Public Health 2018;108:e9–16. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiu K, Grundy Q, Bero L. 'Spin' in published biomedical literature: a methodological systematic review. PLoS Biol 2017;15:e2002173. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2002173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sismondo S, Chloubova Z. “You’re not just a paid monkey reading slides”: How key opinion leaders explain and justify their work. Biosocieties 2016;11:199–219. 10.1057/biosoc.2015.32 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sismondo S. Ghosts in the machine: publication planning in the medical sciences. Soc Stud Sci 2009;39:171–98. 10.1177/0306312708101047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, et al. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2:MR000033. 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grundy Q, Dunn AG, Bourgeois FT, et al. Prevalence of disclosed conflicts of interest in biomedical research and associations with Journal impact factors and altmetric scores. JAMA 2018;319:408–9. 10.1001/jama.2017.20738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Food and Drug Administration Office of Policy Industry-supported scientific and educational activities. Federal Register 1997;62:64093–100. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francer J, Izquierdo JZ, Music T, et al. Ethical pharmaceutical promotion and communications worldwide: codes and regulations. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2014;9:7. 10.1186/1747-5341-9-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonardo Alves T, Lexchin J, Mintzes B. Medicines information and the regulation of the promotion of pharmaceuticals. Sci Eng Ethics 2019;25:1167–92. 10.1007/s11948-018-0041-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-040541supp001.pdf (115.4KB, pdf)