Abstract

Objectives

Previous studies have implicated therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), by measuring serum or urine drug levels, as a highly reliable technique for detecting medication non-adherence but the attitudes of patients and physicians toward TDM have not been evaluated previously. Accordingly, we solicited input from patients with uncontrolled hypertension and their physicians about their views on TDM.

Design

Prospective analysis of responses to a set of questions during semistructured interviews.

Setting

Outpatient clinics in an integrated health system which provides care for a low-income, uninsured population.

Participants

Patients with uncontrolled hypertension with either systolic blood pressure of at least 130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of at least 80 mm Hg despite antihypertensive drugs and providers in the general cardiology and internal medicine clinics.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Attitudes towards TDM and the potential impact on physician–patient relationship.

Results

We interviewed 11 patients and 10 providers and discussed the findings with 13 community advisory panel (CAP) members. Of the patients interviewed, 91% (10 of 11) and all 10 providers thought TDM was a good idea and should be used regularly to better understand the reasons for poorly controlled hypertension. However, 63% (7 of 11) of patients and 20% of providers expressed reservations that TDM could negatively impact the physician–patient relationship. Despite some concerns, the majority of patients, providers and CAP members believed that if test results are communicated without blaming patients, the potential benefits of TDM in identifying suboptimal adherence and eliciting barriers to adherence outweighed the risks.

Conclusion

The idea of TDM is well accepted by patients and their providers. TDM information if delivered in a non-judgmental manner, to encourage an honest conversation between patients and physicians, has the potential to reduce patient–physician communication obstacles and to identify barriers to adherence which, when overcome, can improve health outcomes.

Keywords: hypertension, internal medicine, cardiology, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of the study is the first study that explored the attitudes of patients and clinicians regarding the use of therapeutic drug monitoring in clinical practice, which is important since the concept of drug testing could be interpreted as a lack of trust.

Another strength of the study is additional input from an independent group of community advisory panel.

The limitation of the study is the small sample size and the study setting is limited to indigent care population, which may not be applicable to all healthcare systems.

Introduction

Non-adherence to antihypertensive medications is a major contributor to cardiovascular disease events globally.1 At least half of patients with hypertension are non-adherent to treatment within 1 year of treatment initiation.2–5 In the USA, it was estimated that approximately 16.3 million (31%) of insured US adults with hypertension are non-adherent to their prescribed antihypertensive therapy.6 Given the enormous burden of the problem, pragmatic strategies that improve detection and medication adherence are urgently needed to optimise cardiovascular outcomes.

An increasing number of studies by our group and others have indicated that therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), biochemical monitoring of drug levels in the serum or urine, constitutes a highly reliable technique for detecting medication non-adherence in patients with hypertension not be captured by conventional methods such as patient self-report or pharmacy refill data.2–4 7 In addition, biochemical screening is widely available for clinical use and covered by most health insurance carrier in the USA and many countries worldwide.2 8 Several small observational studies have indicated that when non-adherent patients were given TDM-guided feedback regarding specific undetectable drug levels, blood pressure (BP) improved substantially at subsequent visits despite no significant change in their prescribed antihypertensive regimen and no intensive counselling beyond that typically provided at a regular clinic visit.2 7

While TDM appears promising, the attitudes of patients and clinicians regarding the use of TDM in clinical practice have not been assessed, especially since the concept of drug testing could be interpreted as a lack of trust. Given the higher rates of medical mistrust among low income and minority populations, negative attitudes towards TDM might be a major barrier to implementation among the very high-risk groups with uncontrolled hypertension this approach is designed to help.9 Therefore, we conducted in-depth semistructured interviews of low-income patients and their providers, using a combination of scripted and open-ended follow-up questions, to understand: (1) their knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and concerns about using a blood test to monitor medication adherence and (2) how best to introduce and use TDM in a respectful, patient-centred way.

Methods

This study was approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Board. After an informed consent was obtained, we conducted semistructured interviews with 11 patients who have uncontrolled hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) of at least 130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of at least 80 mm Hg despite treatment with ≥2 antihypertensive drugs, from the general internal medicine and cardiology clinics of Parkland Health & Hospital Systems (PHHS). Exclusion criteria include: (1) presence of hypertensive emergency (BP >180/110 mm Hg plus one of the following features: acute coronary syndrome, acute stroke, hypertensive encephalopathy, aortic dissection or acute kidney injury), (2) history of active substance abuse such as alcohol, cocaine or narcotics, (3) uncontrolled psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia or major depression based on diagnosis entered in electronic medical record, (4) pregnancy, (5) homelessness, (6) stage V Chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end stage renal disease (glomerular filtration rate <15 mL/min/1.73 m2), (7) self-report of non-adherence or unwillingness to follow medication regimen prescribed by the primary care physicians for any reasons, (8) presence of white coat hypertension (defined as normal 24 hours ambulatory SBP or home BP of <130 and diastolic BP of <80 mm Hg and clinic SBP of at least 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP of at least 90 mm Hg and (9) inability to read or write English. PHHS is an integrated health system which serves as the safety-net hospital for a large, low income, uninsured population in the Dallas County, Texas, USA. We also interviewed 10 providers (physicians, mid-level practitioners and clinical pharmacists) who work with low-income patients with poorly controlled hypertension in the Cardiology and General Internal Medicine clinics. Patients and clinicians received a US$20 gift card for their time and participation.

The interviews were designed to assess: (1) how TDM could be used in a way that is acceptable to patients that enhances both the patient–provider relationship and improves patient health outcomes, (2) potential causes of non-adherence, (3) patient’s reluctance to reveal non-adherence to their provider, (4) how TDM could contradict patient self-report about adherence and (5) how this contradiction could potentially affect patient–provider trust and communication. The interview guide comprised nine questions that explored respondents’ personal and/or professional experiences with treatment of hypertension, with the blood test for therapeutic monitoring, and to explore perspectives on how the test may best be used in practice. The interview scripts were tested and refined after initial practice sessions. Follow-up questions were added to elaborate answers and pursue complementary lines of inquiry if the initial response to the main questions was unclear. A patient/provider interview script is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Interview script

| Ques tions | Time (min) |

Main questions | Possible follow-up questions |

| Intro | 5 | Thank you for agreeing to talk with me today. As you know, we are talking with patients who have recently been diagnosed with uncontrolled high blood pressure and their providers. We are trying to find the best way to use an effective new blood test that can help doctors know for sure how much of the medications they prescribe to patients are in the patient’s blood. This can help the doctor understand if the medication is doing what it needs to do to control high blood pressure and improve the patient’s health. We are going to ask you some questions to get your thoughts and ideas about some issues related to high blood pressure in general, taking medications to control high blood pressure, and using this new blood test. There are no right or wrong answers. We hope you will speak freely and honestly. None of your answers will be reported to any of your healthcare providers. This conversation will take about an hour. We will audio record it so we can refer back to what you said. This will let me stay focused on the conversation without having to take notes. If you need to take a break or wish to stop the interview at any time, just let me know. What questions do you have for me before we start? |

|

| #1 | 5 min |

Why is high blood pressure such an important health topic?

Rationale: conversation starter; gets patient thinking about the topic; provides chance to build rapport with patient; gives some insight to what the patient understands about hypertension |

|

| #2 | 5 min | (For patients) What have your providers encouraged you to do about your high blood pressure?

(For providers) As a provider, how do you discuss high blood pressure with your patients? Rationale: makes the conversation personally relevant; builds rapport; starts to elicit patient’s experience with antihypertensive interventions |

|

| #3 | 5 min |

Why might some people not take the medications their doctors prescribe?

Rationale: opens conversation to adherence issues; keeps the focus general/broad to start/ |

|

| # 4 | 5 min |

What do you think about this test? Is it a good idea? Why or why not?

Rationale: introduces TDM; assesses patient’s thoughts and feelings about this intervention. |

|

| #5 | 10 min |

One possible result with this blood test is that it could show that a patient does not have any of the prescribed medication in his or her blood. How do you think patients might react if the results to the TDM test contradict (or goes against) what they tell their doctor about the medications they are taking?

Rationale: explores impact of test on doctor–patient relationship. |

|

| #6 | 10 min |

How could the doctor explain the test in a way that helps the patient feel safe to admit that they might not be taking their medications the way the doctor prescribed?

Rationale: elicits ideas about how to structure the intervention in a patient-centred way. |

|

| #7 | 5 min |

When the doctor gives the patient the results of the test, what should the doctor say or do? When should the doctor do this?

Rationale: elicits further input about how to structure the intervention. |

-How would you want to receive these results from your doctor? Is it important to have them written out for you to see while the doctor is explaining them? How do you think a patient might react to the doctor saying something like this: Mr. Jones, the test results suggest that there is not any drug X in your system. I thought I understood you to say that you were taking all of the medications I prescribed to you for your high blood pressure. I am wondering if there is something about drug x that is causing you some problems and if you are not taking it or not taking it as prescribed. Can you tell me about this? -What is the best way for the doctor to address this issue with the patient? |

| #8 | 5 min |

What would make it easier for a patient to tell the doctor that they are not taking their high blood pressure medications or not taking them the way the doctor prescribed?

Rationale: elicits insights to reasons patients may be non-adherent that providers may need to address. |

In my experience, patients do not always take their medications or take them in the way the doctor prescribes for different reasons. Some patients do not like the way the drug makes them feel, some have a hard time paying for them, or some skip doses to try to make them last. These can be sensitive issues. I have found that patients sometimes have a hard time talking about these very personal things with their doctor. So I ask all my patients if there is anything going on that makes it hard for them to take their high blood pressure medications as prescribed. How about with you? Would a conversation like this help patients feel better about agreeing to do the TDM blood test? |

| #9 | 5 min |

What else do should we think about before we start doing TDM tests for patients?

Rationale: broads the conversation to include anything that might not have come up. |

|

TDM, therapeutic drug monitoring.

Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and analysed under the guidance of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (PCOR) Center’s Qualitative Methods Core.10 Transcripts were coded by three independent coders using a two-step deductive/inductive approach to thematic content analysis.11 After reading all the transcripts, we applied initial open codes derived from the interview guide topics. Line-by-line coding led to understanding and development of thematic categories of codes, using highlighting and margin coding of recurring and relevant themes. Each reviewer coded the transcripts independently then met to discuss their individual findings with the larger team and resolve coding discrepancies by consensus. This iterative process enabled the team to refine and revise codes accordingly.12 The codes identified fell under the categories of adherence barriers, adherence facilitators, barriers to disclosure, monitoring rationale and intervention implications. We also performed a descriptive statistical analysis to assess the proportion of patients or providers who responded to each question in different ways. We ceased recruitment on reaching thematic saturation.

The rationale and proposed methods for the study were also presented to the community advisory panel (CAP) to seek additional input. The CAP programme is curated by the UT Southwestern Center for PCOR to engage community perspectives on the relevance, design and implications of research that has the potential to improve patient-centred care. The members comprise a diverse racial and ethnic group of lay individuals with experience with the PHHS health system or community-based organisations serving minority, low-income populations in Dallas County. The meeting discussion was digitally recorded, transcribed and analysed in a similar fashion as the interview.

Patient and public involvement

The objective of this study was to glean patients’ perspectives in the application of TDM in hypertension management. Patients were not directly involved in the production of the research study design. We supplemented patients’ perspectives with input from the CAP programme, who are meant to represent and serve minority, low-income populations in Dallas County. Their perspectives also greatly contributed to our understanding of how to best use TDM. Input from the CAP programme was not used to implement or modify the study design.

Results

During the course of 4 weeks in September 2018, 54 consecutive patients with uncontrolled hypertension (SBP ≥130 mm Hg or DBP ≥80 mm Hg despite treatment with ≥2 antihypertensive drugs) who visited the General Internal Medicine or Cardiology clinic were identified from the electronic medical record. Among these subjects, 25 were excluded due to the inability to read or write English, 2 due to stage V CKD and 2 due to unwillingness to take their medications. Thirteen patients did not wish to participate and 11 were enrolled in the study. Patient participants included 8 women and 3 men (7 African Americans, 2 Hispanics and 2 non-Hispanic whites). The mean age of patients was 62±11 years. The provider group consisted of 7 men and 3 women (80% non-Hispanic whites, 20% African Americans) with a mean age of 35±10 years. The providers included: three internal medicine residents, three cardiology fellows, two physician assistants, one pharmacist and one cardiology attending physician). None of the providers were directly involved in the care of any of the patient participants.

Patients’ attitude and acceptability to TDM

All 11 patients were aware of the potential impact of high BP and non-adherence to medications on health in terms of increasing the risk of stroke, heart disease, kidney disease and death. All patients identified themselves as adherers to medications as prescribed. When asked about the potential causes of medication non-adherence in general, five patients attributed it to inability to afford medications (which some patients felt uncomfortable mentioning to their providers), five to drug side effects, four to forgetfulness, two to being tired of having to take medications regularly and one to poor insight or health literacy. Overall 91% of patients (10 of 11) believed that TDM would be useful in their care and stated that they would agree to TDM testing. However, 63% (7 of 11) of patients expressed concerns that TDM could potentially negatively impact the physician–patient relationship. Two patients believed that the relationship could be strengthened and two others felt it would have no significant impact. When patients were asked which method of explanation TDM results would make them feel safe to admit their suboptimal adherence, 54% patients believed that they would feel at ease if providers acknowledged medication non-adherence and the underlying reasons, such as cost, inconvenience or forgetfulness, as a common problem. Honest communication by the providers was considered a major factor in facilitating admission of non-adherence in 45% patients. Empathy is thought be a major factor in 27% of patients. Providing education and communication to the patients regarding the adverse health consequences of the non-adherent behaviour is felt to be a major factor that triggers patient’s admittance to non-adherence in 27%. Other potentially positive aspects of TDM mentioned by the patients included enhancing provider’s commitment to help patients (18%), trust (9%), truthfulness (18%) and warm or nurturing personality of providers (9%). The theme and codes of patients’ views are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Selected themes and quotes: patients' perspectives on therapeutic drug monitoring

| Theme | Quote |

| Barrier to adherence | |

| Memory/forgetfulness | Well, and I'm not going to lie, there for a while, I did try to take them. Then, I got so tired of taking them, then I would forget. Then, I'd go a week like that, or I've gotten where I cough so much, because I get bronchitis twice, twice a year. I cough so much, and I take it, and it comes right back up. My sisters used to call me a lot when I first started taking mine, to remind me to take mine, I'd say I already did. They said, okay that's good, 'cause I know if one person is sick, all of us be sick and worried about the other one. We are a very, very close knit family. |

| Cost | Cost for seniors, it's cost. Cause some people don't……can't afford it. they should talk to the doctor about it first if it costs them more money than they have or they could afford. Some people live on a budget. I live on a fixed income. I don't get that much money, and when they talk about, like, I pay my rent and stuff and I know I paid it. I get so upset. |

| Lack of knowledge | I can't go into their mind but I think that they didn't realize the importance of it. |

| Not feeling sick | when they're blood pressure gets controlled they don't think they have to take their medicine anymore. We have a lady that our church just recently had a stroke. She was on blood pressure medicine, but she felt good, and her blood pressure was registering good, so she got off of the medicine. |

| Side effects | I was talking isosorbide something, blood pressure medication, that's the worst. It gave me really bad headaches. It took a while for them to take me off of it, but each time I saw the doctor I would repeat, “I can't function on this medicine.” |

| Adherence facilitators | |

| Symptoms | I don't like taking any medication if I don't have to. But I mean, I have to. It's just the only thing that's going to make me feel better. At first I didn't…I'm like, you know, I didn't care about it. I wouldn't even take it. I wouldn't, until a couple years ago I got a real, real bad headache. I was almost having a stroke, my blood pressure was 200/100. It was real bad. I didn't care at first, but the medicine I started, the medicine does help you to keep it level. Keep you where doctor wants you and your blood pressure. So, I think it's a good thing to take. |

| Trust | Because I go to the same doctors, and I've developed some trust in them for on thing. That's the only thing you can rely on, trusting the doctor. You've got to have some kind of comfort, or trust, with that doctor. Even if it's the first time. Talk to them. They've gotta be easy to talk to. And if they're not easy to talk to, it's hard for you to get what you need from them, because you're not able to tell them what's going on with you. |

| Perceived risks | Because it's not a medical condition that you can feel. It'll take you out without you knowing it. It's scary. I think that's probably the biggest one I can think of. It comes down to if they can't feel the effect of it (high blood pressure) then- |

| Social support | My sisters used to call me a lot when I first started taking mine, to remind me to take mine. |

| Relationship with providers | I guess it depends on every doctor. Like some doctors, they're very friendly and some doctors don't seem too friendly, or some doctors just seem like they're not so interested. They're just in a hurry. “You're here. Okay, this is it.” Then they walk off so you're not comfortable. So why waste your time? You're fixing to tell him something and then they already wanting to leave. The doctor, some doctors can just be cold, you know. Callous, I guess you might, at times, you just kind of make the patient feel uneasy. some doctors talk way up here, and you don't understand. some doctors don't want to take the time to talk to you. If they are just straight going about their day, trying to get the patient in and out, it's a little more difficult for you to talk to them, for you to tell them what's happening. But, if their more inviting to you, or you feel that they're inviting, it's easy to talk to. To tell them, “Hey, this is what's going on with me.” It's kind of hard to find some doctors like that. |

| Barrier to disclosure | |

| Reluctance to admit financial difficulty | I mean nobody wants to admit that you don't have enough funds to do everything that you want to do. You know, and then maybe they suggest maybe we could get a social worker or maybe get you in some program. My age group, asking for a lot of help is not something that we were raised to do. Some people will ask, well do you have any free this or free that, but our culture, my group, that's just not something we're really accustomed to doing. It kind of makes it hard. So you kind of have to, as my daddy said, work easy in that area. The cost is a big thing, it took two years before my mom was ever to tell a doctor I can't afford this med and this med. In fact, it would have never happened if my sister hadn't started taking her to the doctor and interrupting conversation between her and the doctor and saying, I can't afford it. |

| Reluctance to admit side effects | My younger son, his blood pressure is higher you know it's not controlled, but he's younger. The medications that he's been given caused him issues as he always say. So, but my reaction to him was, go back and talk to the doctor. Let them know what the medicine is doing and that you don't want to take it cause you a young and vibrant and you got a wife. Let them prescribe you something else.especially with men, especially with blood pressure pills, a lot of things that they're just not going to tell their doctor unless they're doctors asked because they're embarrassed about these things. Too much stigma, which is a shame. But it's the society that we live in. |

| Monitoring rationale | |

| Confirmation of adherence | So I think it would be a good thing. I know that they do it for their psych patients, cause I have a friend that takes psychiatry medicine, and they check their blood to make sure that they are taking their medications. So if you do that … that would help with blood pressure, that would be pretty cool. it would eliminate some of the guess work as to the wait and see kind of effect. That's I'm going to give this medicine to you, and I'll wait until you come back in three weeks or whatever to see how it reacted, or what changes in your body has come and gone. I don't know. I think it's a good idea. That's a good way to find out what's going on with the patient, and why they're not taking their medicine like they're supposed to. |

| Education opportunity | Well, the doctor could try to change it and inform the patient of what's gonna happen to them if they don't take the medications. |

| Intervention implications | |

| Doctor–patient relationship | Some people, not very happy, because they don't like to be caught, I guess you want to call it. They're busted basically. It could cause a bad feeling between the patient and the doctor, or it could build a trust. So it could go either way depending on the relationship between the patients and the doctors. Probably in a more positive way, because like I said, they would know that the doctor is on top of it, they know that they're getting the right medication, and the right levels. Okay, he meant well. He didn't really … "He chewed me out, sure 'nuff, but his chewing out was for a good cause. Good. Good. You know what I mean? So, I don't think they can be a negative effect. |

| Nurturing and compassion | You want him to tell you what's right but in a compassionate way. Nobody likes to be yelled at or anything. You got to remember that their your patients. Well, I think he should just, again, talk to the patient. There's a lot of patients that you can talk to. But if you approach them the right way, I think the patient will be all right and will be probably understanding. |

| Sensitive to patients' barriers/normalisation of reasons | Again, it depends on the individual. People have reasons for doing things that they do. Some people may have totally different reasons why they take their medicine and why they don't sometime. You know. Some people might not like the side effects of it. Like the doctors aware that all these things can go on, it makes a patient feel better. I don't have to tell you I can't afford it, or it makes me feel weird, or for whatever reason he already knows that these things can happen so it will probably make it easier to discuss. Because everybody has different little issues of what you said. It may not be all of that applied to me, but to different individuals it applies. Some of this stuff applies to them. So I think it's good. |

| Open communication | They may not tell you they're not taking it, but they'll hint around you know about, well see this medicine causes me to do this and this. Some of the young men at our church, when we kind of found out their wives were letting us know they weren't taking their medicine, when you get them alone and you can talk to them, I said she wants you to be alive and well. I said go talk to the doctor and tell him what problems you're having. I said they got me on some medicine so you don't have to … I would rather for you to talk to them and get something that will work with you, rather than not take it and we lose you. Well, if the patient is not telling the truth, they're really playing with their lives, and they need to straighten up and tell the doctor the truth. Ask if they could prescribe something else maybe. Say the medication isn't working, I didn't take it. Just own up to it, and I'd like you to prescribe something else that would help me, but I couldn't take the medication because it made me sick or gave me headaches, or had my heart palpitating. Just tell them the truth. The doctor can't make somebody tell the truth, the patient should own up to it. Just tell them they're not. Say I'm doing it for your own good. |

Providers’ attitude and acceptability to TDM

Similar to the patients’ views, providers (n=10) believed that inability to afford medication, forgetfulness, poor self-efficacy, concerns about medication side effects, pill burden and poor health literacy were major factors contributing to non-adherence. All providers thought TDM was a good idea and should be used regularly. Forty per cent of clinicians believed that TDM could strengthen the patient–provider relationship, particularly in patients in whom non-adherence was initially suspected but TDM demonstrated evidence of adherent behaviour. The same group of providers, however, believe that the results may have a negative effect in others for whom TDM confirmed medication non-adherence. Three providers (30%) believed that TDM results would have no impact on the physician–patient relationship. Two providers (20%) believed that TDM would negatively impact the patient–provider relationship. All providers felt TDM was potentially useful in identifying and solving non-adherence to antihypertensive drugs, if the counselling was delivered in a sensitive manner. When providers were asked how best to explain TDM results, half believed that acknowledging common obstacles to adherence (forgetfulness, side effects, costs and so on) and offering assistance accordingly would make the patients more comfortable revealing non-adherence. Other ideas about discussing TDM results and non-adherence included: building trust and rapport (50%), using non-judgmental language (40%), emphasising honesty (20%) and using it as an opportunity to increase health literacy (20%). The theme and codes of providers’ views are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Selected themes and quotes: provider perspectives on therapeutic drug monitoring

| Theme | Quote |

| Benefits of monitoring | |

| Patient care | l “you're able to actually see if the patient is actually taking their medication"l "helpful as far as giving some objective measure for trying to manage them or treat them or make decision about what to do with their medications"l "knowing what they're doing certainly makes it easier from our perspective to figure out what to do as far as treatment plans…"l “it's a good idea to help being able to confirm what they [patients] do"l " I think it'll be helpful for the practitioners to know when their patietns are telling the truth…"l “knowing that they're not compliant will likely change their clinical care, likely in a positive way"l “you'd be able to avoid the adverse consequence of unnecessarily adding more blood pressure to somebody who doesn't need it"l “it's going to have a positive impact because I'm going to know what to do about my patient's blood pressure” |

| Cost effectiveness | it would be very helpful. I think it could probably potentially save health care dollars” |

| Safety | l “it would help patient safety so we won't be overprescribing the medication"l "I think we would be able to focus our efforts more on counseling them on medication adherence rather than adding the third, fourth, and fifth medicines” |

| Barriers to adherance | |

| Access and affordability | l “they're having issues with funding for their medications"l “one problem we get into here is always cost and that becomes an issue"l "Lastly, cost. If there are so many other medications that patients have to take, and so many other obligations, they might just not chosse to take their blood pressure medications"l “in my experience, one of the biggest problems is, in the venue that i practiced during fellowship, was access issues"l “people can't affords their meds. Even if it's on the Walmart four dollar list, sometimes you've got to make ends meet.“l “Sometimes if there's suspicion about affordability issue, sometimes it's just like, “Are you able to afford your medicine?” You just have to ask that question straight up, and sometimes people are really embarrassed about their financial status so they don't want to tell you." |

| Drug side effects | l "a lot of our people have fear of side effecs. They agree to take it [medication] while in the room [office] and then when the pharmacist tells him about it, they become really worried"l "I think for some of the major anti-hypertensives, there's some very tangible side efffecs that patients feel pretty soon after starting their meds"l “…some people are actually genuinely very afraid of side effects of medications…" |

| Pill burden/ self-efficacy | l “daily dosing vs multiple times a day dosing medication, then they might not want to adhere because they'll forget.“l “…some of these folks who I see have multiple pill bottles and it's hard to keep track of ten bottles"l “if you've never been on medications….to take them every single day is a routine that's hard to get into"l “patients might just have too many medications and that can be a hindrance to the compliance…"l "i think the major reason would be the frequency of which they have to take the medicine…The next most would just be forgetting to take…" |

| Forgetfulness | l “sometimes they just forget, the medicine just falls off the wagon…it's an easy thing to forget…"l "it's easy to forget….it it's twice a day medicine, they very commonly will forget to take the evening dose. Three times a day medicine is just almost impossible sometimes” |

| Communication | l "I've many times talked to patients about language barriers when it comes to reading prescription bottles…I find that patient is not being compliant, that's one of the first things I address with them is, do you understand how to read this prescription bottle, do you know what it means…" |

| Health literacy | l “they may not be aware how serious high blood pressure is, so then they don't really take the medication seriously"l "not understanding the reason why they need to take their medication.so they don't really understand what's behind it. I think those are big considerations for them"l "I think that literacy is a big factor. Honesly, its difficult for people to understand that even though they feel fine now, that taking BP medicine is going to keep them from getting sick later on…" |

| Psychological (denial, unwillingness, bias) | l "they might not be willing to accept the changes that they need to make in their habit in their daily lifestyle to make the medicines daily"l “…there's going to be patients who are hesitant….to take their medications [due to]. suspicion of the medical profession." |

| Barriers to disclosure | |

| Repetition | l “they might have already been counseled from there in the past, and they don't want to repeat the same conversation again” |

| Expectation | l “yeah I guess some people just really want to please the doctor"l "I think the patients to some extent always want to please the provider or the doctor they see. They don't want them to be perceived as I don't do what I'm told” |

| Embarassment | l " patients are probably embarrassed to admit that theyre not taking their medications. “l “this person just feels embarrassed or doesn't want to disappoint their doctor"l But I think it's mostly that position of authority that the doctor sits in and that the patients are embarrassed, or they're afraid of being seen as incompetent or unruly.l "they take their meds because they're afraid that i'm going to think less of them if they tell me they're not taking them…" |

| Intervention implications | |

| Change in perception of patient | l "that's going to happen with or without the testing. if you don't get the desired response. I don't think this will make anything worse"l I don't think so. I think that even when we talk to our patients, we sometimes have a suspicion that they may not be honest with us. I think that this blood test would just be a more objective fact for us to stand upon when we make judgments."l "I would like to think not, but i imaging that I subconsciously probably do…I think on an individual level, it's probably insignificant."l "I would like to think no, but i think that i would potentially be kidding myself if i thought there was not some unconscious bias"l "again, I would hope not. I think it's hard to avoid that kind of unconscious bias but yeah…it does color your judgement of the patient. I try to avoid that, but it's, i think unavoidable”.l "Not necessarily…i guess maybe…I guess it will change my perception about how engaged I perceive them to be in their care."l "I don't think so. I mean, i wouldn't necessarily think, oh, this person's a liar or dishonest. I would presumably just think more, this person just feels embarrassed or doesn't want to disappoint their doctor"l " I know that visceral reactions are going to happen, and people are going to reflex to, 'My patient is a liar'” |

| Mode of counselling | l "if we bring this up gently, this would be something they would be okay with as long as you are not accusatory about it"l " I think that you have to be careful about how it's going to change the dynamic between patient and provider"l "…it could lead to an improved patient/provider relationship. I think the conversation would have to be led very, very skillfully by the provider for that to actually happen” ▶ I think certainly establishing a good relationship with the patient and making sure that you don't create a stigma around it. Making sure that you tell your patient that you, again, are in it as a team, that you two are working together as a team instead of you kind of reprimanding the patient. That will kind of make them more likely to be honest and more willing to work towards compliance. " |

| Patient–doctor relationship | l "No(it wouldn't hurt doctor-patient relationship), again it's just how you would use it….if you use it gently. Just like any test, the practitioner would have to use it with some discretion"l "It can, yes. Because, I mean the patient and provider should have this trust with one another in regards to what they're saying….these blood tests, and you start seeing your patient is actually not taking it."l "I think it would potentially, positively. Right? My goals for the patient wouldn't change. The goals are still to improve their overall care and if I had to take a different strategy or approach to doing that, this may help me do that."l "they might feel like the doctors are tring to act as the big brother…being monitored too much. Maybe the government or doctors…are getting too involved in their life"l "Certainly, that would decrease some tension but i think that might already exist…you already know that patients are being non-compliant even though they say they are…"l " i think regardless of how the discussion is framed, I am sure some people might still feel a little bit defensive on might feel like their provider doesn't trust them. "l "i think it could create additional barriers for patients to participation in their healthcare and continue to actively engage in the healthcare system…"l "it makes me worried that in some cases it may lead to this accusatory or paternalistic scenario…will add this element of tension to the relationship … What it reminds me of. drug monitoring in patients who are on chronic narcotics that the VA does…"l "I think, like I said, it might compromise the provider/patient relationship…it has the potential to cause harm and not a lot of potential to improve the patient relationship” |

| Increased communication | l "I think it's going to open up the conversation. And again, if you don't come in making them defensive, I think this could help to open up"again I try to talk to people from the standpoint that I'm here to help you, but we got to be honest with each other both ways 'cause if we don't do that, that potentially can hurt you if I assume you're doing one thing and treat you based upon that.l "having the objective measures may help us open up that dialect and conversation with them help them get a better understanding that we can work together"l "I think it will open a discussion as to whether they're taking their meds the right way with the right frequency. I think it is similar to the urine tox screen where patients sometimes might deny it but then they also be willing tobe truthful and to discuss the topic further"l "Sometimes patients just forget that they forgot to take their medication, so it could just be another reinforcement to allow for the patient to know that, "Listen, it looks like you aren't taking it as much as you think that you're taking it. We can work on this.” That kind of thing.” |

| Safety | l I think this would kind of help us to lead with why there is no improvement and probably save us from chasing with other more expensive and invasive testing if we have a pretty good idea why the patient is not improving. Yeah it could be safety and cost effective.l I think from a safety perspective, if you are concerned about whether or not a patient is taking all of these medications, instead of just prescribing more of these medicines where we're on our third, fourth or fifth med, but the patient isn't even taking medicine number one or number two, I think with would be able to focus our efforts more on counseling them on medication adherence rather than counseling them on the indications, risks, and benefits to these third, fourth, and fifth medicines. |

| Normalising reasons | l Offering them some reasons, "Maybe the medicine is giving you a side effect. Maybe you're forgetting to take some doses, everybody forgets to take doses.l If you ask a few more times, and especially if you have time, normalizing it, “You're on 15 medications, I understand this is hard to take all of them. In a typical week, how many might you miss” |

Input from the PCOR Center CAP

The results of the patient and provider interviews were subsequently shared with our PCOR Center CAP. Thirteen CAP members were present in the meeting with the study investigators (RC, KBS, BE and WV). The CAP members acknowledged that some patients might feel embarrassed or angry by test results that are discordant from their self-reported adherence behaviour and that some patients have difficulty admitting financial barriers to medication adherence. One CAP member believed that provider should not ‘sugar coat’ the results and tell the patient upfront of the non-adherent behaviour. Most CAP members, however, believed that by acknowledging medication non-adherence as a common problem that most patients had to struggle to overcome obstacles would normalise the challenge and increase the likelihood of a productive discussion of their own non-adherence with providers. At the end of the discussion, all of the CAP members agreed that TDM was potentially useful and suggested several different ways to present the drug testing results to patients that would be acceptable, respectful, not damage patient–provider trust, and be more conducive to problem solving rather than placing blame.

Discussion

Our study explored positive and negative attitudes towards TDM among low-income patients and providers who treat this population to better understand potential barriers and facilitators to using TDM in real-world practice. The major findings from the study are three-fold. First, most patients with hypertension and their providers considered TDM a useful tool in monitoring adherence to medications. Second, more than half of patients and providers initially expressed concerns about the potential negative impact on the relationship if the results of TDM suggested non-adherent behaviour. Third, most patients believed that presenting TDM results in a collaborative, non-judgmental manner and exploring reasons underlying suboptimal adherence directly with the patient may lead to improved adherence and health outcomes. Remarkably, providers shared a similar view to the patients when discussing TDM results.

Adherence to medications can be monitored by several methods, including patient self-report, detailed questionnaires, pill counts, prescription fill rates, direct observation, electronic pillboxes or ingestible digital pills.13–15 Although self-report is often used to assess adherence, patients tend to overestimate their adherence to antihypertensive medications when compared with electronic pillbox data.15 Physicians' ability to predict patients' adherence to antihypertensive medications in the primary care setting is notoriously poor.16 Prescription fill rates may not be accurate if patients receive automatic prescription refills but do not ingest the dispensed medication.17 On the other hand, more accurate techniques, such as electronic monitoring or digital pill technology, are limited by the high cost which is not covered by any insurance carrier in the USA.2 In contrast to electronic monitoring, TDM is covered by insurance carriers in the USA and many countries worldwide.2 To our knowledge, our study represents the first that explores patients’ and providers’ attitudes in adopting TDM in routine practice.

We were encouraged that patients and provider identified similar reasons for medication non-adherence, barriers to disclosing them to providers, as well as the potential benefit of TDM to both hypertension control and the patient–provider relationship. As expected, both patients and providers expressed concerns about the potential impact of TDM on trust. However, patients and providers believed the benefits of an honest discussion about adherence outweighed the potential risks to the patient–provider relationship. Specifically, patients recommended that providers acknowledge that medication non-adherence is a common but addressable challenge. More importantly, many patients recommended providers ask if they experienced specific barriers to adherence such as drug cost or forgetfulness as patients reported often having difficulty volunteering information upfront due to shame and guilt. Patients also suggested that providers discuss medication non-adherence in the context of how hard it can be for many people to change all kinds of health behaviours like diet and physical activity. This approach would both decrease stigma and shame about this common occurrence, and set the stage for an honest, patient-centred discussion for practical strategies for improving adherence and hypertension control. In our interviews, providers who raised concerns about TDM adversely impacting patient trust also indicated that framing and presentation of adherence mattered and could mediate their concern. Overall, this suggests that provider education and training will be important if TDM is to be incorporated into routine clinical practice.

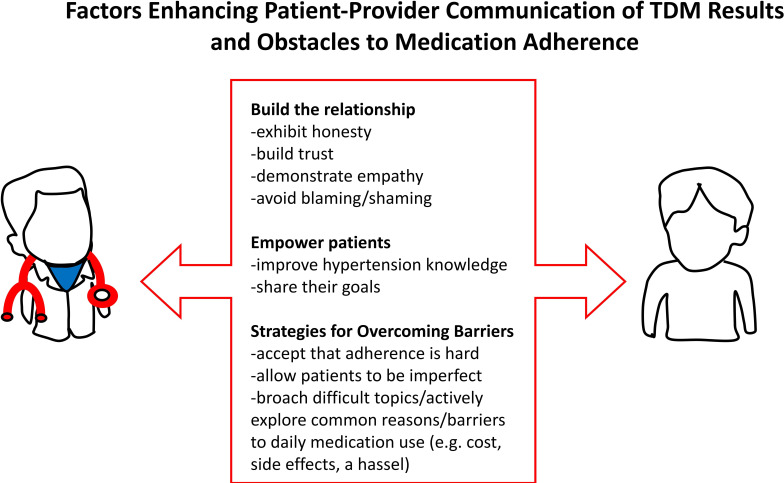

Presenting findings to the CAP provided the added advantage of providing a collective and peer-based approach to ‘member-checking,’ a qualitative technique where researchers test their understanding or interpretation of findings with participants. In our study, we found CAP reactions to the issues of non-adherence were remarkably similar to those patients we interviewed, validating our findings. Community members recognised adherence as a challenge to patients. Their remarks emphasised their shared experience as patients with first-person accounts of their experience. Based on input from patients, providers and CAP members, we propose several key factors that are essential in enhancing patient–provider communication of TDM results and obstacles to medication adherence as shown in figure 1. Future work to design interventions might benefit from more explicit engagement with family members and other caregivers to identify their role in managing patient adherence that might complement TDM efforts in the clinic.

Figure 1.

Proposed factors enhancing patient–provider communication of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) results and obstacles to medication adherence.

This was a qualitative methods pilot study so our small sample size is a potential limitation. The study results may not be applicable to many patients who were excluded from the study due to inability to read or write English or verbally expressed non-adherence to medication. Furthermore, more than half of eligible patients refused to participate and their views regarding TDM may differ from those participating in our study. During the interview, we did not address the limitation of TDM in the capturing drug levels with short half-life or long sample collection time since last ingestion which may lead to misinterpretation of results by the clinicians. Nevertheless, we were able to explore attitudes in depth among the patients enrolled in the study, and the themes that emerged are concordant with the literature on medication non-adherence. Additionally, participants were patients who were predominantly non-White, low income, uninsured individuals in an urban safety health system, and clinicians who care for these vulnerable populations so generalisability to other settings is uncertain. On the other hand, such patients and settings are most heavily impacted by non-adherence and poor hypertension control.

In summary, the idea of TDM was well-accepted by patients and providers. Despite the fact that both groups expressed concerns that TDM could potentially negatively impact the physician–patient relationship, more than 90% of patients and providers believed that TDM constituted an effective tool in identifying and overcoming barriers to adherence, especially if providers could address this common and important problem in a respectful, patient-centred fashion.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @realHamzaLodhi, @@sandeepdasmd, @@DrWanpen

Contributors: WV is the senior author. KBS and SS interviewed participants. KBS, HL, BW, SAS and SS organised recorded transcripts. KBS, RC and WV coded the transcripts. WV conceived the study. BE, EAH, SJCL and WV contributed to study design. WV, RC, BE, SJCL, SAS, RBJ, SD, EAH and KBS contributed to the final manuscript. WV and EAH secured funding support. WV is the guarantor.

Funding: This project was supported by grant number R24HS022418 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (to EAM, BE, SCL, and WV), the UT Southwestern T32 training grant in Nephrology (to RC), and the UT Southwestern O’Brien Kidney Center and the Pak Center of Mineral Metabolism and Clinical Research (to WV).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. All data acquired from this prospective analysis will be shared with the public scientific community upon request. Requests can be made to wanpen.vongpatanasin@utsouthwestern.edu. This includes original recorded transcripts and coded data. Data will be made available upon publication with no end date. The lead author (KBS) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1. Chowdhury R, Khan H, Heydon E, et al. Adherence to cardiovascular therapy: a meta-analysis of prevalence and clinical consequences. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2940–8. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brinker S, Pandey A, Ayers C, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring facilitates blood pressure control in resistant hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:834–5. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pandey A, Raza F, Velasco A, et al. Comparison of Morisky medication adherence scale with therapeutic drug monitoring in apparent treatment-resistant hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens 2015;9:420–6. 10.1016/j.jash.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Velasco A, Chung O, Raza F, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of therapeutic drug monitoring in diagnosing primary aldosteronism in patients with resistant hypertension. J Clin Hypertens 2015;17:713–9. 10.1111/jch.12570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vrijens B, Vincze G, Kristanto P, et al. Adherence to prescribed antihypertensive drug treatments: longitudinal study of electronically compiled dosing histories. BMJ 2008;336:1114–7. 10.1136/bmj.39553.670231.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang TE, Ritchey MD, Park S, et al. National rates of nonadherence to antihypertensive medications among insured adults with hypertension, 2015. Hypertension 2019;74:1324–32. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gupta P, Patel P, Štrauch B, et al. Biochemical screening for nonadherence is associated with blood pressure reduction and improvement in adherence. Hypertension 2017;70:1042–8. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chung O, Vongpatanasin W, Bonaventura K, et al. Potential cost-effectiveness of therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with resistant hypertension. J Hypertens 2014;32:2411–21. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Armstrong K, Ravenell KL, McMurphy S, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in physician distrust in the United States. Am J Public Health 2007;97:1283–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Committee. P-C. The PCORI methodology report; 2019.

- 11. Creswell JW, Miller DL. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Pract 2000;39:124–30. 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burnier M, Egan BM, Egan Brent M. Adherence in hypertension. Circ Res 2019;124:1124–40. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feyz L, Bahmany S, Daemen J, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring to assess drug adherence in assumed resistant hypertension: a comparison with directly observed therapy in 3 nonadherent patients. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2018;72:117–20. 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zeller A, Ramseier E, Teagtmeyer A, et al. Patients' self-reported adherence to cardiovascular medication using electronic monitors as comparators. Hypertens Res 2008;31:2037–43. 10.1291/hypres.31.2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zeller A, Taegtmeyer A, Martina B, et al. Physicians' ability to predict patients' adherence to antihypertensive medication in primary care. Hypertens Res 2008;31:1765–71. 10.1291/hypres.31.1765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ruzicka M, Leenen FHH, Ramsay T, et al. Use of directly observed therapy to assess treatment adherence in patients with apparent treatment-resistant hypertension. JAMA Intern Med 2019. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.1455. [Epub ahead of print: 17 Jun 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.