Abstract

Gene mutations linked to lignin biosynthesis are responsible for the brown midrib (bm) phenotypes. The bm mutants have a brown-reddish midrib associated with changes in lignin content and composition. Maize bm1 is caused by a mutation of the cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase gene ZmCAD2. Here, we generated two new bm1 mutant alleles (bm1-E1 and bm1-E2) through EMS mutagenesis, which contained a single nucleotide mutation (Zmcad2-1 and Zmcad2-2). The corresponding proteins, ZmCAD2-1 and ZmCAD2-2 were modified with Cys103Ser and Gly185Asp, which resulted in no enzymatic activity in vitro. Sequence alignment showed that CAD proteins have high similarity across plants and that Cys103 and Gly185 are conserved in higher plants. The lack of enzymatic activity when Cys103 was replaced for other amino acids indicates that Cys103 is required for its enzyme activity. Enzymatic activity of proteins encoded by CAD genes in bm1-E plants is 23–98% lower than in the wild type, which leads to lower lignin content and different lignin composition. The bm1-E mutants have higher saccharification efficiency in maize and could therefore provide new and promising breeding resources in the future.

Keywords: cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase, EMS mutagenesis, biofuels, C4 grass, forage

Introduction

Lignin is a phenolic polymer that provides mechanical support to plant organs and protects the plant from pathogen attacks, thus playing a vital role in plant growth and development (Bhuiyan et al., 2009; Barros et al., 2015; Gallego-Giraldo et al., 2020). Lignin is produced from the polymerization of monolignols, which are synthesized through the phenylpropanoid pathway. Lignin polymer consists of three predominant types: p-hydroxyphenyl (H), guaiacyl (G) and syringyl (S) subunits (Vanholme et al., 2010). The presence of lignin in the plant cell wall reduces (CWRs) the efficiency of ethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass and the digestibility of forage for animal consumption (Chen and Dixon, 2007). Thus, modifying lignin content in plants can be an effective approach for forage improvement (Jung and Ni, 1998).

Lignin content and its composition are particularly important in plants. Studying the monolignol metabolic pathways is key to develop successful genetic breeding programs (Dixon and Barros, 2019). Brown midrib (bm) mutants are a good model to study such metabolic pathways. They have a reddish midrib phenotype and variation in lignin content. This phenotype was initially described about 90 years ago and was discovered in C4 grasses (i.e., maize, sorghum, and pearl millet) (Jorgenson, 1931; Sattler et al., 2010). Six bm mutants (bm1-6) have been isolated in maize. Mutation loci have been analyzed in bm1-5 (Vignols et al., 1995; Halpin et al., 1998; Tang et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015; Xiong et al., 2019). Genes responsible for bm1 and bm3 encode for cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD) and caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT), respectively (Vignols et al., 1995; Halpin et al., 1998). Mutated genes in both bm2 and bm4 are involved in one-carbon metabolism, and encode for functional methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) and folypolyglutamate synthase (FPGS) respectively (Tang et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015). The recently cloned gene in bm5 encodes for 4-coumarate: coenzyme A ligase (4CL) (Xiong et al., 2019). Besides changes in lignin content and composition, bm mutants show improved forage efficiency (Vignols et al., 1995; Godin et al., 2016), which makes them promising breeding resources.

CAD catalyzes the NADPH-dependent reduction of hydroxycinnamyl aldehydes to their alcohol derivatives which are then incorporated into lignin (Goffner et al., 1992; Vanholme et al., 2010). The bm1 maize mutant was caused by a transposon insertion in the first intron of CAD2 (GRMZM5G844562) gene (Chen et al., 2012). Decreased CAD activity in bm1 reduces its Klason lignin content and G and S monomers yield (Halpin et al., 1998). The bmr6 phenotype is the result of a mutation in the CAD gene in sorghum, same as in maize bm1 (Saballos et al., 2009; Sattler et al., 2009). The bmr6 mutant also exhibits altered lignin content and composition with higher saccharification efficiency (Sattler et al., 2009). CAD catalyzes the final and essential step in the monolignol biosynthesis and genetic modification in the CAD gene leads to changes in lignin content and composition (Yan et al., 2019). CAD deficiency decreases overall lignin content, alters lignin structure and increases enzymatic recovery of sugars in rice, tomato, Brachypodium, and switchgrass (Saathoff et al., 2011; d’Yvoire et al., 2013; Li et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2019).

In this study, two new maize bm1 mutant alleles were obtained through ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) mutagenesis. To study the impacts of the mutation on ZmCAD2 function, the expression level of ZmCAD2 was determined in bm1-E mutants and Z58. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to determine whether the missense mutations have impact on ZmCAD2 gene expression. Unlike previous reported maize bm1 mutants, the new bm1 alleles resulted from a single base mutation and the missense mutation caused the encoded proteins lost activity. The study indicated the conserved amino acids Cys103 and Gly185 were important sites for CAD2 activity and it provided new alleles impacting lignin biosynthesis in maize, as well as cell wall digestibility efficiency and plant breeding.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

Maize plants were grown in the greenhouse at 26°C, 16 h of light and 8 h of darkness. Maize bm1 stock (bm1-PI228174) was derived from the Maize Genetics COOP Stock Center. The bm1-E mutants (bm1-E1 and bm1-E2) were obtained from an EMS mutagenic population which was generated from the inbred line Z581. Phenotypic identification was confirmed through hybrid complementation tests with bm1 plants. Z58 plants with no reddish midrib phenotype were used as the wild type control.

Gene Cloning and Expression Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from leaf tissue using the 2 × CTAB protocol (Porebski et al., 1997). To determine the mutations responsible for the bm1 phenotype, the ZmCAD2 gene was cloned and sequenced using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. The ZmCAD2 genes were amplified from the mutants, sequenced and aligned against the Z58 genome.

Total RNA was extracted from the midrib of 60 days-old plant using Trizol according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, United States). The extracted RNA was treated with DNaseI. The expression level of the CAD gene in the midrib was analyzed using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay (Tang et al., 2014).

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

The CAD coding region was amplified from Z58 and bm1-E plants and then sub-cloned into pET32a vector. The recombinant vectors were transferred into BL21 Escherichia coli cells. Cells were cultured at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium. Isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.3 mM at mid-log phase (A600 = 0.4∼0.6). Cells were continued to be incubated at 18°C for 16 h and harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 5 min. Soluble proteins were extracted by sonication and the recombinant proteins were purified with Ni affinity column (GE Healthcare) for further enzyme activity (Youn et al., 2006).

Enzyme Activity and Protein Structure Analyses

Enzymatic activity was determined as described by Scully et al. (2016). Midribs of the second to fifth leaves from the top were collected from 60-day old bm1-E mutants and Z58 wild type plants. Powdered fresh midribs (∼0.5 g) were extracted for 3 h at 4°C in protein extraction buffer (Liu et al., 2012). The samples were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the extracts were desalted on PD-10 columns (Pharmacia) and used for CAD enzyme activity assay. The assay was performed using 200 ng of purified recombinant CAD proteins or 100 μg of total protein for midrib extracts with different substrates. The reaction was carried out at 30°C for 30 min in 300 μL of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.4 mM NADP, 1 mM DTT, 5% ethylene glycol, and 0.14 mM substrates (p-coumaraldehyde, coniferaldehyde, and sinapaldehyde).

The three-dimensional structure of CAD in bm1-E mutants was predicted using the SWISS-MODEL2. SWISS-MODEL generated models by homology using amino acid sequences to infer the stoichiometry and the overall structure of the assembly (Bertoni et al., 2017).

Chemical Analysis

Maize midribs were collected from the fourth-to-fifth leaves of 60-day-old plants. CWRs were prepared and used for further chemical analysis as described previously (Chen and Dixon, 2007). Lignin content was quantified using the acetyl bromide method. The thioacidolysis method was used to measure the lignin composition (Lapierre et al., 1986; Hatfield et al., 1999). For enzymatic hydrolysis analysis, CWR was digested by direct exposure to a cellulase and cellobiase mixture for 72 h (as untreated samples). Enzymatic saccharification of samples was performed following the analytical procedure of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (LAP-009). Saccharification efficiency was calculated as the ratio of sugars released by enzymatic hydrolysis versus sugar content in the CWR. Sugar release was analyzed using the phenol-sulfuric acid assay method (Dubois et al., 1956). Cellulose and hemicellulose were extracted as described in Yu et al. (2014). Monomeric sugars were determined by HPLC (Agilent 1200 Series LC system with 1200 Series refractive index detector) equipped with an Aminex HPX-87P column (Agilent Technologies).

Statistical Analysis

Three biological replicates were used for all collected data and the mean values were used for statistical analyses. Data from each trait were subjected to Student’s t-test. One or two asterisks indicate significance corresponding to P < 0.05 or 0.01. Standard errors were provided in all tables and figures as appropriate.

Results

Identification of New bm1 Alleles

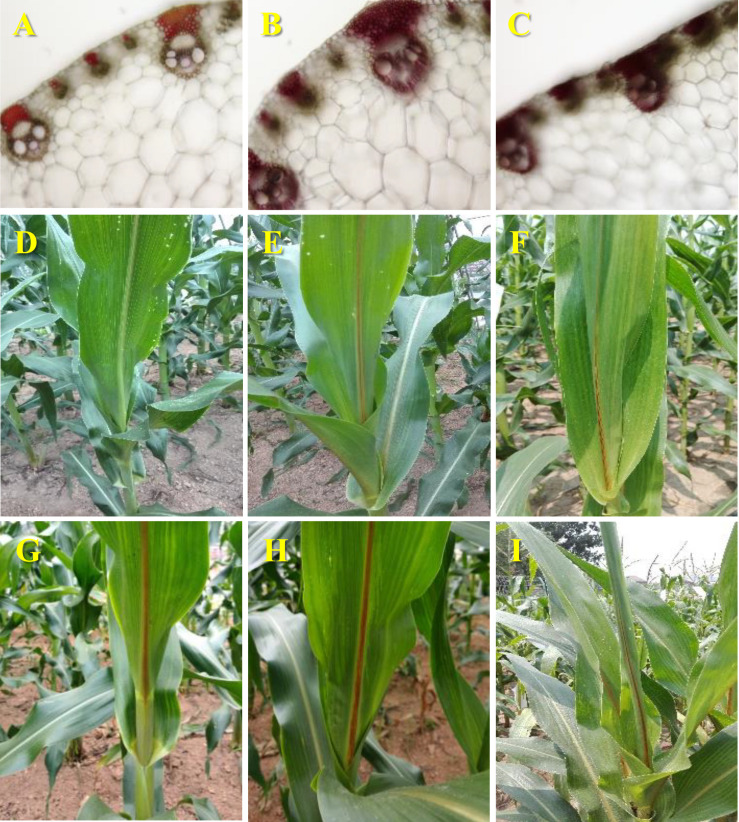

Two putative bm mutants were isolated from the EMS-mutagenic population. Stained midrib cross sections with phloroglucinol-HCl showed a darker brown in these two new bm mutants than in Z58. This indicates higher accumulation of aldehyde derivatives in their lignified tissues and the incorporation of cinnamyl aldehydes, the substrates for CAD (Figures 1A–C). Indeed, the allelism tests with the previously described maize bm1 mutant (Gene stock ID: bm1-PI267186) confirmed that two new EMS-mutagenized bm mutants were bm1 alleles (bm1-E) (Figures 1D–I).

FIGURE 1.

Morphological characterization of the bm1-E mutants. Midribcross sections stained with acid phloroglucinolof the fourth leaf collected from 60-days old wild-type Z58 (A), bm1-E1 (B), and bm1-E2 (C). Adaxial view of themidrib of 45-days old wild-type Z58 (D), bm1-E1 (E), bm1-E2 (F), bm1 (G), hybrid bm1 × bm1-E1 (H), and hybrid bm1 × bm1-E2 (I). Cross sections and adaxial view of the midribs from three independent materials of each plants were used for histochemical assay and phenotypic measurements.

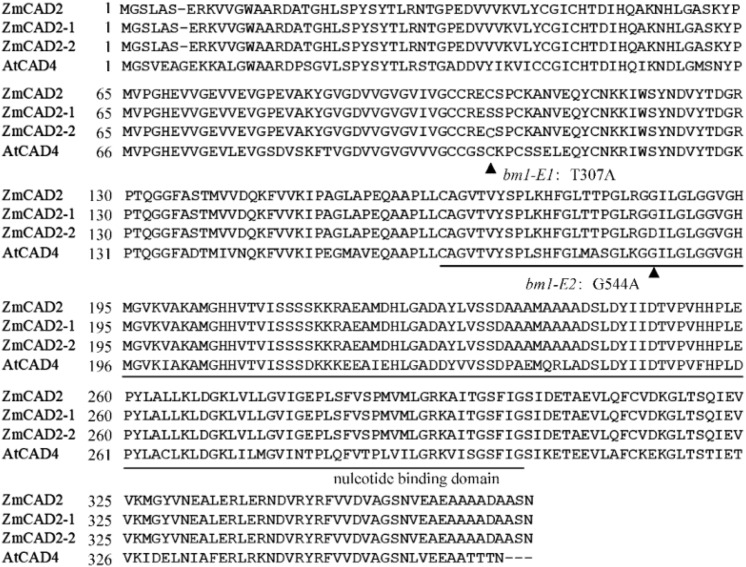

In bm1-E mutants, two transition missense mutations (T357A and G554A) were identified in the ZmCAD2 coding region (Figure 2). In bm1-E1 plants, Cys103 was converted into Ser, while Gly185 was converted into Asp in bm1-E2 plants (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment of predicted cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase proteins. The mutant amino acid was highlighted in red color. The protein sequences of ZmCAD2 was aligned with ZmCAD2-1, ZmCAD2-2, and AtCAD4 proteins using ClustalW. AtCAD4: Arabidopsis thaliana P48523.1; ZmCAD2: Zea maize GRMZM5G844562. ▲ indicates the mutant amino acids; the line indicates the nucleotide biding domain.

Impacts of the Mutation on ZmCAD2 Function

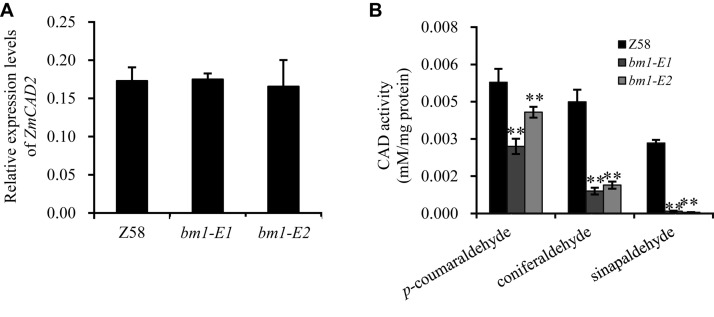

To study the impacts of the mutation on ZmCAD2 function, the expression level of ZmCAD2 were determined in bm1-E mutants and Z58. No significant differences were detected in the expression levels of ZmCAD2 between the wild type and two bm1-E mutants (Figure 3A). Although the missense mutation did not affect the expression of the ZmCAD2 gene in bm1-E plants, its impact in the enzymatic activity remains uncertain. The recombinant corresponding mutation proteins of Zmcad2 of bm1-E (ZmCAD2-1 and ZmCAD2-2) were expressed in vitro. The point mutations Cys103Ser and Gly185Asp both resulted in no CAD activity compared with the wild type (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S1).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of ZmCAD2 mutation in gene expression and CAD enzymatic activity in midribs of the fourth leaf collected from 60-days old plants. (A) Gene expression levels of ZmCAD2. (B) CAD enzymatic activity in different substrates: p-coumaraldehyde, coniferaldehyde, and sinapaldehyde. Values shown are means ± SD from three technical replicates and three biological replicates. Two asterisks indicate significance corresponding to P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

TABLE 1.

Enzymatic activity of ZmCAD2 and its mutated versions in different substrates in vitro.

| Name | Amino acids | Substrates |

||

| p-Coumaraldehyde | Coniferaldehyde | Sinapaldehyde | ||

| Z58 | Cys103Gly185 | √ | √ | √ |

| bm1-E1 | Ser103Gly185 | ND | ND | ND |

| bm1-E2 | Cys103Asp185 | ND | ND | ND |

| M1 | His103Gly185 | ND | ND | ND |

| M2 | Lys103Gly185 | ND | ND | ND |

| M3 | Gly103Gly185 | ND | ND | ND |

| M4 | Asp103Gly185 | ND | ND | ND |

| M5 | Met103Gly185 | ND | ND | ND |

M: mutation;

ND: no enzymatic activity detected.

In vivo assays showed that CAD enzymatic activity significantly decreased in the midrib of two bm1-E mutants (Figure 3B). In the p-coumaraldehyde substrate, CAD activity in bm1-E1 and bm1-E2 was 51.1 and 71.1% lower than in the wild type. In coniferaldehyde, it was only 20.0 and 25.4% compared to the wild type (Figure 3B). In sinapalaldehyde, the enzymatic activity of bm1-E1 and bm1-E2 was reduced to 3.3 and 1.6% of the wild type (Figure 3B).

Impacts of ZmCAD2 Point Mutations on Predicted Protein Structure

CAD belongs to the medium chain dehydrogenase/reductase (MDR) superfamily. It is composed of two distinct domains: the nucleotide-binding domain and the catalytic domain (Figure 2) (Jornvall and Hoog, 1995). Here, a mutation in Cys103Ser observed in ZmCAD2-1 protein led to no CAD activity (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S1). The predicted protein structure showed that Cys103Ser would not change the three-dimensional structure of ZmCAD2 (Supplementary Figure S2). When Cys103 was replaced with any other amino acid (His, Asp, Lys, Gly, and Met), there was no enzymatic activity using p-coumaraldehyde, coniferaldehyde, and sinapalaldehyde as substrates (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S2). Therefore, our results suggest that Cys103 is essential for CAD catalytic activity.

The nucleotide-binding domain of ZmCAD2 is located in the 163–301 region (Figure 2). The Gly185Asp mutation in ZmCAD2-2 protein did not change ZmCAD2 three-dimensional protein structure except for the amino acid substitution (Supplementary Figure S2). Gly and Asp were different in structure, as Asp contained a side-chain. A replacement of Gly185 for Asp resulted in the lack of CAD enzymatic activity for ZmCAD2-2. This is consistent with former observations in sorghum (Scully et al., 2016). In bmr6-23 and bmr6-1103, Gly184 was mutated into Asp, and no CAD enzyme activity was detected (Scully et al., 2016).

Impact of bm1-E Mutant on Lignin Content and Composition

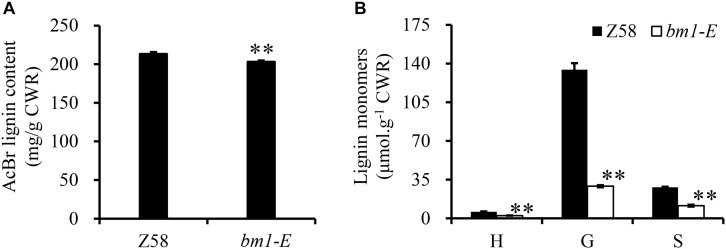

Reduction of CAD activity in plants would affect the biosynthesis of lignin. Herein, the lignin content and its composition were analyzed in Z58 and bm1-E plants. Lignin content in bm1-E mutants decreased by 5.11 and 4.38% compared to Z58 (Figure 4A). Furthermore, levels of H, G, and S lignin were also lower than in the wild types (reduced to 43.3, 21.7, and 40.9%, respectively) (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of bm1-E mutation on lignin content (A) and lignin composition (B). Midribs of the second to fifth leaves from the top were collected from 60-days old bm1-E mutant and Z58 wild type maize. Values are means ± SE from three biological replicates. Two asterisks indicate significance corresponding to P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

bm1-E Biomass Has Increased Glucose Yields Following Enzymatic Saccharification

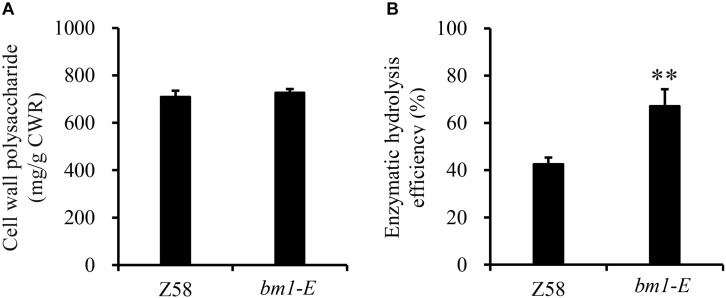

To determine the impact of bm1-E mutant on fermentable sugars, the cellulose and hemicellulose contents were measured with CWRs. The cellulose content in bm1-E mutants was 6.02% higher (346.9 mg/g CWR) than in the wild type Z58 (327.2 mg/g CWR) (Table 2). The hemicellulose content was also changed in bm1-E plants. Xylose and arabinose contents were lower in bm1-E, while glucose, galactose, rhamnose, and galacturonic acid levels were higher (Table 2). The xylose content accounts for 73.4% of the total hemicellulose in the wild type Z58, and in bm1-E mutant was reduced from 256.7 to 200.8 mg/g CWR (i.e., a relative decrease of 21.8%) (Table 2). The total cell wall polysaccharide was not significantly changed in bm1-E plants (Figure 5A). Additionally, bm1-E mutants showed an enzymatic saccharification efficiency of 67.1% at 72 h against 42.5% in Z58 plants (Figure 5B).

TABLE 2.

Cellulose content and monosaccharide composition (mg/g CWR) of non-cellulosic cell wall carbohydrates in Z58 and bm1-E plants.

| Plant | Cellulose | Xylose | Arabinose | Glucose | Mannose | Galactose | Rhamnose | Galacturonic acid |

| Z58 | 327.2 ± 6.42 | 256.7 ± 22.65 | 28.8 ± 1.68 | 44.3 ± 2.46 | 5.5 ± 2.20 | 5.1 ± 0.29 | 1.8 ± 0.09 | 7.4 ± 0.26 |

| bm1-E | 346.9 ± 5.88** | 200.8 ± 12.92** | 23.1 ± 2.39** | 56.8 ± 2.03** | 4.7 ± 1.08 | 6.5 ± 0.72** | 2.4 ± 0.47** | 8.2 ± 2.11** |

Midrib samples were collected from 60-days old Z58 and bm1-E1 plants.

Values are means ± SE from three biological replicates.

One or two asterisks indicate significance corresponding to P < 0.05 or 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of bm1-E mutation on total sugar content (A) and enzymatic hydrolysis efficiency (B). Stalk samples were collected from 90-days old bm1-E mutants and Z58 wild type plants. Values are means ± SE from three biological replicates. Two asterisks indicate significance corresponding to P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

Discussion

The ZmCAD2 gene was first identified and mapped in maize bm1 mutants in Halpin et al. (1998). Mutations in this gene dramatically reduce its transcription rate and enzymatic activity, which results in reduced lignin content and changes in lignin composition (Halpin et al., 1998). In this study, two new maize bm mutants (bm1-E1 and bm1-E2) were obtained through EMS mutagenesis and were certified to be bm1 alleles. The expression level of ZmCAD2 did not significantly changed in bm1-E in comparison to the wild type Z58 (Figure 3A). Both ZmCAD2-1 and ZmCAD2-2 showed no enzymatic activity in vitro (Table 1). The missense mutations in bm1-E reduced CAD activity by 75–98% in the midribs of bm1-E plants, especially in coniferaldehyde and sinapaldehyde (Figure 3B). CAD catalyzes the final step in the monolignol biosynthesis. A mutation in the CAD gene leads to the accumulation of hydroxycinnamyl aldehyde derivatives in maize and Medicago truncatula (Halpin et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 2013). The accumulation of cinnamyl aldehydes in the midrib was confirmed with phloroglucinol-HCl staining (Halpin et al., 1998). The bm1-E mutants exhibited a decrease in lignin content and altered lignin composition due to changes in the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathways (Figure 4).

Total lignin content in bm1-E was 4.7% lower, while it was significantly reduced by 20% in former identified maize bm1 (Halpin et al., 1998). There are two possible explanations for this: one is that different methods were adopted to extract and analyze the lignin content. The other reason is that maize stalk was examined instead of the midrib. Although the lignin content did not vary, lignin composition was significantly reduced for H, G, and S lignin in bm1-E plants.

Conserved CAD proteins are important for its enzymatic activity. They have two main domains: the nucleotide-binding domain and the catalytic domain (Figure 2). Cys103 and Gly185 are generally conserved in CAD proteins (Youn et al., 2006; Scully et al., 2016). Cys103 is in the catalytic domain in ZmCAD2, which is an important function in the MDR family (Youn et al., 2006). ZmCAD2-1 protein displayed no enzymatic activity, and no activity was detected when Cys103 was replaced for other amino acids (Table 1). When Gly185 was changed for Asp, ZmCAD2 also lost its enzymatic activity (Table 1). Previous study has suggested that a point mutation Gly185Asp in OsCAD2 protein sequence of rice gh2 results in complete loss of the CAD and SAD activities which leads to impaired lignin biosynthesis and a reddish-brown pigmentation in the hull and internode in rice (Zhang et al., 2006). The same point mutation Gly185Asp was observed in the ZmCAD2 of bm1-E2, implying that Gly185 is crucial for CAD structure and function. Interestingly, another point mutation Gly184Asp in CAD sequence of sorghum Bmr6-23 and -1103 mutants can lead to nearly undetectable bmr6 protein in vitro (Scully et al., 2016). It was formerly suggested that changing Gly for Asp without a side-chain would impact hydrophilicity, and that Gly185 occurred in close to residues predicted for dimerization, which would interfere the enzyme forming a homodimer (Scully et al., 2016). In contrast, the changing Gly185 for Asp in OsCAD2 only affects CAD activity rather than gh2 protein expression in vitro (Zhang et al., 2006). Thus, the conserved amino acids in CAD may play different roles in its enzymatic structure and function.

The Cys103 and Asp185 mutations resulted in loss of its enzyme activities (Table 1). In spite of no enzymatic activity in the mutant ZmCAD2 proteins, other CAD proteins compensated the cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase activity. Still, CAD enzyme activities were dramatically reduced in vivo, especially in coniferaldehyde and sinapaldehyde (Figure 3). CAD enzymatic activity in bm1-E was 75.6–80% lower than the wild type in coniferaldehyde, and 96.7–98.4% in sinapalaldehyde (Figure 3B). The OsCAD2 protein sequences in gh2 (Zhefu802 as the background), undergoing a same point mutation with ZmCAD2 in bm1-E2, lost its function (Zhang et al., 2006). And gh2 plant obviously exhibited reddish-brown in the internode (Zhang et al., 2006). The CAD activities for total gh2 plant proteins in all tested tissues (except for midrib) were dramatically reduced using coniferaldehyde as substrate, while its activity was not detectable using gh2 proteins from panicle, hull, sheath, internode, and root tissues using sinapylaldehyde as substrate (Zhang et al., 2006). It was speculated that CAD isoenzymes unevenly exist in maize different tissues and less CAD homologs using sinapylaldehyde as substrate exists in maize midrib. Still, the enzyme activity reduction seems not be consistent the reduced S lignin content. The main reason for this is that the thioacidolysis method (Figure 3B) mainly proceeds by the cleavage of β-O-4 aryl ether lignin structures which account for about 50% of all lignin linkages in maize.

Lignin abundance and structure are correlated to saccharification efficiency in plants, which could improve the saccharification efficiency of cell wall polysaccharides (Sattler et al., 2010). Indeed, cell wall saccharification efficiency of polysaccharides was higher in bm1-E plants. Three main reasons could explain it: (i) The lignin content is reduced in bm1-E (Figure 4A). Lignin is a major obstacle to cell wall degradation, and its content is negatively correlated with biomass enzymatic saccharification efficiency (Tarasov et al., 2018). (ii) S/G ratio was increased in bm1-E mutant compared with Z58 wild type (Figure 4B). Recent articles have indicated that the S/G ratio may play dual roles in biomass enzymatic hydrolysis for sugar yields (Studer et al., 2011; Yoo et al., 2017; Alam et al., 2019). (iii) The arabinose and xylose level of hemicellulose was significantly reduced in bm1-E mutant (Table 2). It has been proposed that the major arabinose should be associated with lignin for cell wall network construction, which somehow explains the reduced arabinose level in both mutants should somewhat disassociate with lignin inter-linkage, resulting in raised biomass porosity for high enzymatic hydrolysis (Wang et al., 2016). ZmCAD2 is the major gene responsible for lignin biosynthesis in maize. CAD2 mutants have a brown midrib phenotype, and variable lignin accumulation. The missense mutation in the ZmCAD2 in bm1-E showed no enzyme activity in vitro, and CAD enzymatic activity was severely affected in vivo (Figure 3B and Table 1). However, catalysis of the hydroxycinnamyl aldehydes to their corresponding alcohols derivatives was still observed (Figure 4). It is possible that other CAD genes were responsible for this catalytic activity. CAD genes belong to the MDR family and has many homologous in plants (Youn et al., 2006). There are nine CAD-like putative genes in Arabidopsis, of which AtCAD4 and AtCAD5 show the highest catalytic activity and are mainly responsible for lignin formation in vivo (Sibout et al., 2005; Youn et al., 2006). Twelve CAD-like genes have been previously identified in rice and OsCAD2 was the major CAD gene responsible for lignin biosynthesis in rice (Zhang et al., 2006; Hirano et al., 2012). Interestingly, AtCAD4, AtCAD5, OsCAD2, Bmr6, and ZmCAD2 were clustered in a clade together (Hirano et al., 2012). This indicates that CAD gene function is conserved across different plant groups, and that ZmCAD2 is the main gene responsible for CAD catalytic ability in maize.

Like other bm mutants in maize, the saccharification efficiency was improved in bm1-E mutants (Chen and Dixon, 2007). The new bm1 mutations presented here would provide more resources for research study, lignocellulosic biomass utilization, and plant breeding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

CF, XL, and WX conducted experimental design and manuscript writing. WX, YL, ZW, LM, YCL, LQ, JL, JS, GY, and MC conducted in experiments and data collection. CF, YL, WX, ZH, SG, and CZ analyzed the data. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The handling editor declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration, with several of the authors WX, YL, ZW, LM, YCL, and CF.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Hanzhong Deng from Qingdao Institute of Bioenergy and Bioprocess Technology, the Chinese Academy of Sciences for modeling structure of ZmCAD2 and related proteins.

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the National Key Technologies Research & Development Program-Seven Major Crops Breeding Project (No. 2016YFD0101803), Agricultural Variety Improvement Project of Shandong Province (Nos. 2019LZGC010 and 2019LZGC002), the Major Program of Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2018ZB0213), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31872879 and 31800254), Forage Industrial Innovation Team, Shandong Modern Agricultural Industrial and Technical System (SDAIT-23-01), and China Agriculture Research System (CARS-34).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.594798/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alam A., Zhang R., Liu P., Huang J., Wang Y., Hu Z., et al. (2019). A finalized determinant for complete lignocellulose enzymatic saccharification potential to maximize bioethanol production in bioenergy Miscanthus. Biotechnol. Biofuels 12:99. 10.1186/s13068-019-1437-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros J., Serk H., Granlund I., Pesquet E. (2015). The cell biology of lignification in higher plants. Ann. Bot. 115 1053–1074. 10.1093/aob/mcv046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoni M., Kiefer F., Biasini M., Bordoli L., Schwede T. (2017). Modeling protein quaternary structure of homo- and hetero-oligomers beyond binary interactions by homology. Sci. Rep. 7: 10480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan N. H., Selvaraj G., Wei Y., King J. (2009). Role of lignification in plant defense. Plant Signal. Behav. 4 158–159. 10.4161/psb.4.2.7688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Dixon R. A. (2007). Lignin modification improves fermentable sugar yields for biofuel production. Nat. Biotechnol. 25 759–761. 10.1038/nbt1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., VanOpdorp N., Fitzl D., Tewari J., Friedemann P., Greene T., et al. (2012). Transposon insertion in a cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase gene is responsible for a brown midrib1 mutation in maize. Plant Mol. Biol. 80 289–297. 10.1007/s11103-012-9948-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon R. A., Barros J. (2019). Lignin biosynthesis: old roads revisited and new roads explored. Open Biol. 9:190215. 10.1098/rsob.190215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M., Gilles K. A., Hamilton J. K., Rebers P. A., Smith F. (1956). Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 28 350–356. 10.1021/ac60111a017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- d’Yvoire M. B., Bouchabke-Coussa O., Voorend W., Antelme S., Cezard L., Legee F., et al. (2013). Disrupting the cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 1 gene (BdCAD1) leads to altered lignification and improved saccharification in Brachypodium distachyon. Plant J. 73 496–508. 10.1111/tpj.12053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Giraldo L., Liu C., Pose-Albacete S., Pattathil S., Peralta A. G., Young J., et al. (2020). Arabidopsis dehiscence zone polygalacturonase 1 (ADPG1) releases latent defense signals in stems with reduced lignin content. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 3281–3290. 10.1073/pnas.1914422117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin B., Nagle N., Sattler S., Agneessens R., Delcarte J., Wolfrum E. (2016). Improved sugar yields from biomass sorghum feedstocks: comparing low-lignin mutants and pretreatment chemistries. Biotechnol. Biofuels 9:251. 10.1186/s13068-016-0667-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffner D., Joffroy I., Grimapettenati J., Halpin C., Knight M. E., Schuch W., et al. (1992). Purification and characterization of isoforms of cinnamyl alcohol-dehydrogenase from Eucalyptus xylem. Planta 188 48–53. 10.1007/bf01160711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpin C., Holt K., Chojecki J., Oliver D., Chabbert B., Monties B., et al. (1998). Brown-midrib maize (bm1) - a mutation affecting the cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase gene. Plant J. 14 545–553. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00153.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield R. D., Grabber J., Ralph J., Brei K. (1999). Using the acetyl bromide assay to determine lignin concentrations in herbaceous plants: Some cautionary notes. J. Agr. Food Chem. 47 628–632. 10.1021/jf9808776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano K., Aya K., Kondo M., Okuno A., Morinaka Y., Matsuoka M. (2012). OsCAD2 is the major CAD gene responsible for monolignol biosynthesis in rice culm. Plant Cell Rep. 31 91–101. 10.1007/s00299-011-1142-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson L. R. (1931). Brown midrib in maize and its linkage relations. J. Am. Soc. Agron. 23 549–557. 10.2134/agronj1931.00021962002300070005x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jornvall H., Hoog J. O. (1995). Nomenclature of alcohol dehydrogenases. Alcohol Alcohol. 30 153–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H. J., Ni W. (1998). Lignification of plant cell walls: impact of genetic manipulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 12742–12743. 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre C., Monties B., Rolando C. (1986). Thioacidolysis of poplar lignins - identification of monomeric syringyl products and characterization of guaiacyl-syringyl lignin fractions. Holzforschung 40 113–118. 10.1515/hfsg.1986.40.2.113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Hill-Skinner S., Liu S. Z., Beuchle D., Tang H. M., Yeh C. T., et al. (2015). The maize brown midrib4 (bm4) gene encodes a functional folylpolyglutamate synthase. Plant J. 81 493–504. 10.1111/tpj.12745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Cheng C., Zhang X., Zhou S., Li L., Yang S. (2019). Overexpression of pear (Pyrus pyrifolia) CAD2 in tomato affects lignin content. Molecules 24:2595. 10.3390/molecules24142595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Shi R., Li Q., Sederoff R. R., Chiang V. L. (2012). A standard reaction condition and a single HPLC separation system are sufficient for estimation of monolignol biosynthetic pathway enzyme activities. Planta 236 879–885. 10.1007/s00425-012-1688-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. F., Tobimatsu Y., Kusumi R., Matsumoto N., Miyamoto T., Lam P. Y., et al. (2019). Altered lignocellulose chemical structure and molecular assembly in CINNAMYL ALCOHOL DEHYDROGENASE-deficient rice. Sci. Rep. 9:17153. 10.1038/s41598-019-53156-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porebski S., Bailey L. G., Baum B. R. (1997). Modification of a CTAB DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 15 8–15. 10.1007/bf02772108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saathoff A. J., Sarath G., Chow E. K., Dien B. S., Tobias C. M. (2011). Downregulation of cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase in switchgrass by RNA silencing results in enhanced glucose release after cellulase treatment. PLoS One 6:e16416. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saballos A., Ejeta G., Sanchez E., Kang C., Vermerris W. (2009). A genomewide analysis of the cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase family in sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] identifies SbCAD2 as the brown midrib6 gene. Genetics 181 783–795. 10.1534/genetics.108.098996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler S. E., Funnell-Harris D. L., Pedersen J. F. (2010). Brown midrib mutations and their importance to the utilization of maize, sorghum, and pearl millet lignocellulosic tissues. Plant Sci. 178 229–238. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler S. E., Saathoff A. J., Haas E. J., Palmer N. A., Funnell-Harris D. L., Sarath G., et al. (2009). A nonsense mutation in a cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase gene is responsible for the sorghum brown midrib6 phenotype. Plant Physiol. 150 584–595. 10.1104/pp.109.136408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully E. D., Gries T., Funnell-Harris D. L., Xin Z., Kovacs F. A., Vermerris W., et al. (2016). Characterization of novel Brown midrib 6 mutations affecting lignin biosynthesis in sorghum. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 58 136–149. 10.1111/jipb.12375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibout R., Eudes A., Mouille G., Pollet B., Lapierre C., Jouanin L., et al. (2005). Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase-C and -D are the primary genes involved in lignin biosynthesis in the floral stem of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17 2059–2076. 10.1105/tpc.105.030767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer M. H., DeMartini J. D., Davis M. F., Sykes R. W., Davison B., Keller M., et al. (2011). Lignin content in natural Populus variants affects sugar release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 6300–6305. 10.1073/pnas.1009252108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H., Liu S., Hill-Skinner S., Wu W., Reed D., Yeh C. T., et al. (2014). The maize brown midrib2 (bm2) gene encodes a methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase that contributes to lignin accumulation. Plant J. 77 380–392. 10.1111/tpj.12394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov D., Leitch M., Fatehi P. (2018). Lignin-carbohydrate complexes: properties, applications, analyses, and methods of extraction: a review. Biotechnol. Biofuels 11:269. 10.1186/s13068-018-1262-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanholme R., Demedts B., Morreel K., Ralph J., Boerjan W. (2010). Lignin biosynthesis and structure. Plant Physiol. 153 895–905. 10.1104/pp.110.155119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignols F., Rigau J., Torres M. A., Capellades M., Puigdomenech P. (1995). The brown midrib3 (bm3) mutation in maize occurs in the gene encoding caffeic acid O-methyltransferase. Plant Cell 7 407–416. 10.2307/3870079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Fan C., Hu H., Li Y., Sun D., Wang Y., et al. (2016). Genetic modification of plant cell walls to enhance biomass yield and biofuel production in bioenergy crops. Biotechnol. Adv. 34 997–1017. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W., Wu Z., Liu Y., Li Y., Su K., Bai Z., et al. (2019). Mutation of 4-coumarate: coenzyme A ligase 1 gene affects lignin biosynthesis and increases the cell wall digestibility in maize brown midrib5 mutants. Biotechnol. Biofuels 12:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Liu J., Kim H., Liu B., Huang X., Yang Z., et al. (2019). CAD1 and CCR2 protein complex formation in monolignol biosynthesis in Populus trichocarpa. New Phytol. 222 244–260. 10.1111/nph.15505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo C. G., Yang Y., Pu Y., Meng X., Muchero W., Yee K. L., et al. (2017). Insights of biomass recalcitrance in natural Populus trichocarpa variants for biomass conversion. Green Chem. 19 5467–5478. 10.1039/c7gc02219k [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Youn B., Camacho R., Moinuddin S. G. A., Lee C., Davin L. B., Lewis N. G., et al. (2006). Crystal structures and catalytic mechanism of the Arabidopsis cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenases AtCAD5 and AtCAD4. Org. Biomol. Chem. 4 1687–1697. 10.1039/b601672c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Shi D., Li J., Kong Y., Yu Y., Chai G., et al. (2014). CELLULOSE SYNTHASE-LIKE A2, a glucomannan synthase, is involved in maintaining adherent mucilage structure in Arabidopsis seed. Plant Physiol. 164 1842–1856. 10.1104/pp.114.236596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Qian Q., Huang Z., Wang Y., Li M., Hong L., et al. (2006). GOLD HULL AND INTERNODE2 encodes a primarily multifunctional cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase in rice. Plant Physiol. 140 972–983. 10.1104/pp.105.073007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Tobimatsu Y., Zhou R., Pattathil S., Gallego-Giraldo L., Fu C., et al. (2013). Loss of function of cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 1 leads to unconventional lignin and a temperature-sensitive growth defect in Medicago truncatula. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 13660–13665. 10.1073/pnas.1312234110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.