Abstract

Background:

The tea-plucking activity in Garo Hills, Meghalaya, India is performed in a traditional way making the majority of women workers, especially those who have spent more years in tea-plucking activity prone to musculoskeletal disorders.

Materials and Methods:

The present study was conducted on a sample of 40 women workers who had the highest field experience in tea leaf plucking. Pain as a musculoskeletal disorder was recorded using a 5-point scale ranging from very mild pain (1) to very severe discomfort (5) to quantify the stress on muscles used in work. The coefficient of correlation was used to explore the relationship between age, years of involvement, BMI of women, and their musculoskeletal problem. The analysis of discomfort in upper extremity was done by using a rapid upper limb assessment (RULA) technique. Analysis of discomfort in entire body parts was carried out using a rapid entire body assessment (REBA) technique.

Results and Discussion:

During tea plucking, women workers reported severe discomfort in the head (4.5), neck (4.3), both fingers (4.2), upper and lower back (4.3 and 4.4), and feet (4.3). The RULA grand score was observed seven indicating the need for immediate investigation and changes. REBA result was 11 for entire body parts leading to conclude that workers were working under high physical strain.

Conclusion:

Workers with severe musculoskeletal disorders can face permanent disability that prevents them from returning to their jobs or handling simple everyday tasks. Therefore, some rest periods, ergonomic intervention, and personal protective equipment are needed to minimize the discomfort of women workers in the tea-plucking activity.

Keywords: Ergonomics, musculoskeletal disorders, posture, tea cultivation

INTRODUCTION

Small tea plantation in the hills of Meghalaya, India is being recognized as one of the promising sectors in doubling farmer's income. It is the most labor-intensive among the plantation crops which employs a large number of people. The small tea farmers are self-employed and they have opened a new horizon for others particularly for women and other family members. In India, small tea growers have opened a door to rural mass in getting employment which leads to economic empowerment.[1,2] Tea plucking is the most labor-intensive and tedious job in tea production industry where women were involved globally. Though tea plantation activity does not demand specialized skills or gender, still the tea-plucking part is regarded as a female activity.[3] It accounts for about 40% of the cost of production and 60% of the total field cost and approximately 67% of the field workforce in tea plantations is engaged in tea plucking.[4] Tea plucking is perceived to be the most difficult task as the women had to pluck tea leaves for 8 hours in continuous standing posture. Many of the activities, especially the plucking activity performed by the workers in tea plantations demand a high degree of physical effort because of repetitiveness and assuming static awkward posture, leading to early fatigue, and work-related musculoskeletal problems. Ergonomic intervention in designing work accessories can reduce work-related stress by assisting the plucking operation.[5] One of the preliminary objectives in ergonomic assessment is the prevention of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs). So, keeping in view the most neglected and essentially required aspects of drudgery due to plucking of tea leaves, the present study has been planned to make an ergonomic assessment of the occupational and posture discomfort among Garo women workers working in hill areas of West Garo Hills, Meghalaya, India. In brief, the present study was envisaged to assess the musculoskeletal disorders due to adopted body posture of the Garo women workers engaged in tea-plucking activity.

LITERATURE REVIEW

WMSDs of the upper extremities are common causes of pain and can lead to significant distress, lost function, and functional disability.[6,7] Tea-plucking activity is a repetitive task where a worker stands for long duration with carrying load on the head for the entire shift. WMSDs result in pain and discomfort in different body parts of a significant numbers of workers in tea gardens. The workers perform the activity in the entire shift with highly repetitive job of tea plucking. The sustained work with awkward or biomechanically stressful postures increased the risk of tea leaf pluckers.[8] This indicates that the plucking operations with awkward postures affect the shoulder and upper limbs in general and lead to WMSDs in the long run. Studies have also reported that workers felt pain in fingers, wrists, upper and lower arm.[9,10] Their back is also severely affected as they have to carry a heavy load of tea leaves up to 30 kg in their traditional basket kokcheng (a native bamboo basket) for entire shift. According to ILO Report, the permissible limits of lifting and carrying load in comfortable outdoor climate condition in winter is 20 kg, in warm outdoor climatic condition in summer is 15 kg, and young and older women workers should not handle loads exceeding 15 kg.[11] But in an another study it was found that Garo women have a habit of carrying load in the kokcheng on an average 30 kg, but some of them carried up to 40 kg also for firewood collection.[12,13] A study in Tamil Nadu on tea plucker women revealed that majority of the women workers were found to suffer from back pain which is quite similar to other studies.[14] Several studies reported that for tasks other than manual handling, static postural loading has been shown to be a risk factor for low back pain (LBP), especially when combined with long work duration.[15,16] The awkward standing posture of the workers causes pain in the upper and lower back, ankle and standing for long duration leads to severe pain in the feet.[17] When back muscles or ligaments are injured from repetitive pulling and straining, the back muscles, discs and ligaments can become scarred, weakened, and lose their ability to support the back, making additional injuries more likely.[18]

The power of handgrip is the result of forceful flexion of all finger joints with maximum voluntary force that the subject can exert under normal biokinetic conditions.[19,20,21] Studies have indicated that the grip strength of both hands of male and female farmworkers has reduced after performing the uprooting and transplanting tasks.[22] Studies have also revealed that the strength of handgrip used to decline after jobs where jobs were in repetitive fashion.[23,24] When awkward posture is for long-duration chances of back disorders is at high risk. It also appears that the load on the spine increases when workers sit without back support, compared with workers standing, which is mainly due to a change in the shape of the lumbar spine.[25] Thus, the increase in spinal load may be another cause of reduced back strength.[26,27] Studies also recorded that if the workers continued to work in awkward posture with forceful lifting movement and manual work at rapid rate they will suffer from the MSDs related to neck, trunk, and wrist.[28]

Based on the findings of the above literatures, the present study was envisaged to assess the musculoskeletal disorders due to adopted body posture of the Garo women workers engaged in tea-plucking activity.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study was conducted on women tea-garden workers in villages of Tebronggre, Bokda Apal, Ampanggre, Chibra Agital, Waram Songma, and Waram Asimgre in West Garo Hills district of Meghalaya. Forty tea-garden women workers who have spent more than 5 years in tea-plucking activity in two age groups 20–35 years and 36–50 years were selected. The subjects who had highest field experience were selected because there is a significant positive correlation between years of involvement and musculoskeletal problems.[29] Postural discomfort in various body parts is recorded by showing the Corlett and Bishop's body map to the subjects and asking them to identify the region of any pains/aches in the body parts during rest, before lunch, and just after end of work.[30] Five-point scale ranging from very mild (1) to very severe (5) discomfort is used to quantify the stress on muscles used in work. Grip dynamometer was used to measure the strength of grip muscles during rest, before lunch, and after performance of the activity. It was measured separately both for the right and left hand and the percentage change in grip strength was calculated using the following formula,

Where, Sr = strength of muscles at rest

Sw = strength of muscles after work

Back dynamometer was used to measure the strength of back during rest, before lunch, and just after the end of work. The same formula used for change in grip strength was followed to calculate the percentage reduction of average strength of back.

The analysis of working postures adopted during tea plucking was performed using rapid upper limb assessment (RULA) and rapid entire body assessment method (REBA) as a means to assess posture for the risk of developing WMSDs. RULA is a posture sampling tool to examine the level of risk associated with upper limb disorders of individual workers such as high task repetition, forceful exertions, and sustained or repetitive awkward postures associated with upper extremity musculoskeletal disorder.[31] The tea-plucking activity involves carrying a load on their head which affects the upper extremity of the workers. Therefore, RULA in this study was intended to measure the risks of injury due to physical loading on the back of tea-plucking women workers. The REBA was specifically designed for analyzing the entire body postures, strength, load, in addition, most suitable for work done standing, exactly due to the highlight given to the lower limbs, although not failing to consider the upper limbs, torso, neck, and activity factors.[32] Since tea plucking is performed in a continuous standing position, thus REBA was also used in the study.

Statistical analysis of data

Descriptive statistics and weighted mean scores were used to analyze collected data during the experiments. The coefficient of correlation was used to identify the relationship between selected independent variables (age, years of involvement, and BMI of women workers) and dependent variables (i.e. intensity of body discomfort) where the coefficient of correlation (r-value) lies between −1 and +1.

Ethical issues

This study received ethics approval from the Ethics Review Committee of North Eastern Hill University, Tura Campus, Chandamari, Tura, Meghalaya on 05 Aug 2019.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This section of the study is divided into different subheads to ascertain musculoskeletal discomfort which can affect almost all parts of the body depending upon the physical movement characteristics and work setup.

Musculoskeletal problems

Table 1 shows the intensity of musculoskeletal problems while working in the tea-plucking activity. Under existing working conditions, the women workers complained of severe pain in the head (4.5), neck (4.3), both fingers (4.2), upper and lower back (4.3 and 4.4), and feet (4.3). Moderate to severe pain was reported by a worker in the neck (3.8) and shoulder joint (3.9) which is the most common disorder for occupational workers where the job demands fine visual attention. When fine visual attention is required, the worker leans forward to do the activity. This forward bend of the head and trunk puts stress on the lower spine and neck muscles making them fatigued which can be defined as low back and neck pain of workers as occupational LBP.

Table 1.

Musculoskeletal problems faced by the respondents

| Different parts of the body | Age group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 20-35 years (n=20) | 36-50 years (n=20) | 20-50 years (n=40) | |

| Upper extremity | |||

| Head | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.5 |

| Eye | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.5 |

| Neck | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.3 |

| Shoulder joint | 3.8 | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| Upper arm | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| Elbow | 3.1 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Lower arm | 3 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Wrist (RH) | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Wrist (LH) | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.5 |

| Fingers (RH) | 3.9 | 4.6 | 4.2 |

| Fingers (LH) | 4 | 4.5 | 4.2 |

| Upper back | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.3 |

| Lower extremity | |||

| Low back | 4.7 | 4.1 | 4.4 |

| Buttock | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.2 |

| Upper leg/thigh | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Knee | 3.6 | 4.2 | 3.9 |

| Calf muscle | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| Ankle | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Feet/toe | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.3 |

Note: 5-point scale (1=very mild, 2=mild, 3=moderate, 4=severe, 5=very severe) Percentage Reduction of Handgrip Strength

Since tea plucking involves the abduction of the upper arm, the position of the lower arm was working across the midline of the body. Moreover, the wrist position showed that it was bent from the midline and the wrist was also twisted at or near end range. The neck and the trunk position were also flexed resulting in an awkward position for the women workers to perform the tea-plucking activity. The calculation of handgrip strength has been found to reveal the relation between body, wrist, and forearm position. Here in this study, the percentage reduction in the handgrip strength was found to be less before lunch and was quite high after completion of the work. It was observed that during the plucking activity, the grip strength decreased because of tiredness of muscles as the women had to pluck tea leaves for 8 h in a repetitive manner continuously. Table 2 shows that the percentage reduction of handgrip strength was more (17.96% for right and 17.27% for left hand) at the end of the day in comparison to the percentage reduction of grip strength of women just before lunch. Further analysis indicated that the percentage reduction of both right and left hand was more in the case of the young age group (20–35 years) of tea garden women labor.

Table 2.

Percentage reduction in the handgrip strength in tea-plucking activity

| Parameter Grip strength |

Age group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-35 years (n=20) | 36-50 years (n=20) | Total (20-50 years) (n=40) | ||||

| Right hand | Left hand | Right hand | Left hand | Right hand | Left hand | |

| Before lunch | 8.98 (4.63) | 8.71 (4.23) | 9.12 (5.78) | 8.63 (6.47) | 8.73 (0.20) | 8.91 (0.10) |

| Just before end of work | 20.08 (6.99) | 18.75 (6.29) | 15.84 (6.80) | 15.80 (8.03) | 17.96 (2.12) | 17.27 (1.47) |

Note: Figures in parentheses indicate standard deviationPercentage Reduction of Back Strength

In this study, tea-plucking women workers adopt static as well as dynamic posture for a long duration (8-h working schedule per day) which is similar to another study conducted on different occupations of static muscular forces which reduce blood flow, deplete nutrients, and lead to a build-up of metabolic waste in their back. Thus, the spinal load is increased which may be another cause of their reduced back strength.[26,27] This study has also shown that the percentage reduction has occurred for back strength just before lunch and just after the end of work as well. Table 3 indicated the average percentage reduction of back strength of women worker in the tea industry and shows that there was a 2.32% reduction of back strength just before lunch and an 8.57% reduction just before the end of work. Further when the percentage reduction of back strength with handgrip strength was compared; it was observed that the percentage reduction was less in case of back strength of Garo women workers.

Table 3.

Percentage reduction of the average strength of back of the respondents

| Age group | Before lunch | Just before end of work |

|---|---|---|

| 20-35 years (n=20) | 2.49 (0.9) | 8.29 (2) |

| 36-50 years (n=20) | 2.15 (1.1) | 8.86 (1.9) |

| Total (20-50 years) (n=40) | 2.32 (0.2) | 8.57 (0.4) |

Note: Figures in parentheses indicate standard deviation (SD) RULA and REBA Scores

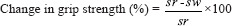

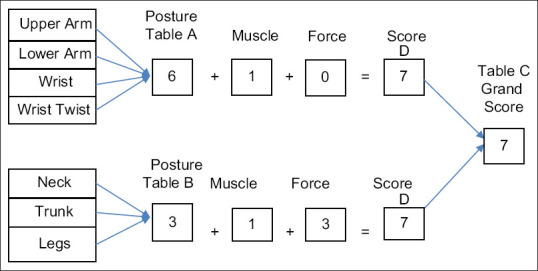

The RULA result revealed that the mean value of wrist and arm score was found to be 7 and the mean score for neck, trunk, and leg was also 7, thus, leading to a final mean score for all the respondents which is 7 [Table 4 and Figure 1]. This score generates an action level that the respondents were working in a poor posture and there could be a risk of injury to their health from work posture. The reasons for this need to be investigated further and change should be brought about soon to prevent an injury. After analysis and calculation, the final REBA result was 11 for entire body parts, where workers were found to be working at high-risk levels under high physical strain and change is recommended for the health benefit of workers [Table 4 and Figure 2].

Table 4.

RULA and REBA scores for women in teaplucking activity

| Method | Risk assessment score | Risk level | Action level |

|---|---|---|---|

| RULA | 07 | High | Investigate and implement change |

| REBA | 11 | Very high risk | Implement change |

RULA: rapid upper limb assessment; REBA: rapid entire body assessment

Figure 1.

RULA scoring flowchart

Figure 2.

REBA scoring flowchart

Correlation between age, years of involvement, and BMI of women workers with their musculoskeletal problems

To find out the correlation between selected independent variables (age, years of involvement and BMI of women workers) with their overall musculoskeletal problems, in the first stage, the cumulative discomfort intensity score of different body parts presented in Table 1 (i.e. head, neck, fingers, upper back, lower back, feet) was calculated. Then in the second stage, the coefficient of correlation was calculated. Table 5 highlights that there existed a significant positive relationship of a musculoskeletal problem with age (r = 0.497) and years of involvement (0.320). From Tables 1 and 5, it can be concluded that back pain is the most severe and significant among the respondents. The workers also felt discomfort in fingers, wrists, upper and lower arm, and in the shoulder joint.

Table 5.

Correlation between age, years of involvement and BMI of women workers with their musculoskeletal problems

| Age | Work Experience | BMI | MSD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .655** | .287 | .497** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .072 | .001 | ||

| Work Experience | Pearson Correlation | .655** | 1 | .121 | .320* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .456 | .044 | ||

| BMI | Pearson Correlation | .287 | .121 | 1 | .250 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .072 | .456 | .119 | ||

| MSD | Pearson Correlation | .497** | .320* | .250 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .001 | .044 | .119 |

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

CONCLUSION

From this study, it can be concluded that while performing the tea-plucking operation workers were found to assume unnatural posture which is static as well as highly dynamic with load in their kokcheng up to 30 kg of weight. It is noticed that the workers have discomforts in their body parts due to long working hours, insufficient rest breaks, and awkward movements with monotonous and repetitive work. The age of the women workers and years of involvement are considered as the factors associated with WRMDs. Plucking activity in tea garden has been reported as maximum drudgery prone activity where the output of the work decreases and the health of the women workers are also affected. Musculoskeletal discomfort was more among middle-aged women workers who had worked for a longer duration where no medical intervention was done to solve the issue. According to the Hours of Work (Industry) Convention, 1919 (No. 1) and the Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices) Convention, 1930 in India, no worker shall work for more than 5 h before having a break of at least half an hour.[33] Some techniques and technologies such as adjustable strap to support the head for the tea-plucking basket while carrying the load in the hilly terrain along with some personnel protective equipment for fingers like rubber finger cots and finger stalls should be introduced for them to reduce their occupational drudgery which will lead to better occupational health and thereby productivity of worker will enhance.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research received no financial support for the study, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Department of Family Resource Management, College of Community Science, Central Agricultural University, Tura- 794005, Meghalaya.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goowalla H. Labour relations practices in tea industry of Assam with special reference to Jorhat district of Assam. IOSR J Hum Soc Sci. 2012;1:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayami Y, Damodaran A. Towards an alternative agrarian reform: Tea plantations in South India. Econ Pol Wkly. 2004;39:3992–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wickramasinghe AD, Cameron DC. ernational Farm Management Congress, August 10-15. 16th 2003. Economies of scale paradox in the Sri Lankan Tea Industry. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sivaram B, Herath DPB. Talawakele, Sri Lanka: Tea Research Institute of Sri Lanka; 1996. Labour Economics in Tea. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kishtwaria J, Rana A, Sood S. Work pattern of hill farm women: A study of Himachal Pradesh. Stud Home Comm Sci. 2009;3:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rempel DM, Harrison RJ, Barnhart S. Work-related cumulative trauma disorders of the upper extremity. J Am Med Assoc. 1992;267:838–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw WS, Feuerstein M, Lincoln AE, Miller VI, Wood PM. Ergonomic and psychosocial factors affect daily function in workers’ compensation claimants with persistent upper extremity disorders. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:606–15. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiker SF, Chaffin DB, Langolf GD. Shoulder postural fatigue and discomfort: A preliminary finding of no relationship with isometric strength capability in a light-weight manual assembly task. Int J Indus Ergon. 1990;5:133–46. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dul J, Neumann WP. Ergonomics contributions to company strategies. App Ergon. 2009;40:745–52. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker‐Bone K, Palmer KT. Musculoskeletal disorders in farmers and farm workers. Occup Med. 2002;52:441–50. doi: 10.1093/occmed/52.8.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ILO. International Labour Organization (Maximum Weight Convention, 1967 (No 127) Thailand (Ratification: 1969) [Last accessed on 2019 Jul 20]. Available from: https://wwwiloorg/dyn/normlex/en/fp=NORMLEXPUB:13101:0::NO::P13101_COMMENT_ID:3186097 .

- 12.Borah S. Physiological workload of hill farm women of Meghalaya, India involved in firewood collection. Procedia Manufac. 2015;3:4984–90. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suthar N. The impact of physical work exposure on musculoskeletal problems among tribal women of Udaipur District. Int NGO J. 2011;6:43–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vasanth D, Ramesh N, Fathima FN, Fernandez R, Jennifer S, Joseph B. Prevalence, pattern, and factors associated with work-related musculoskeletal disorders among pluckers in a tea plantation in Tamil Nadu, India. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2015;19:167–70. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.173992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattacharyya N, Baruah SC, Borah R, and Bhagawati P. Ergonomic assessment of postures assumed by workers in tea cultivation. Asian J of Home Sc. 2013;8:580–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverstein BA. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan; 1985. The prevalence of upper extremity cumulative disorders in industry. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyers J, Bloomberg L, Faucett J, Janowitz I, Miles JA. Using ergonomics in the prevention of musculoskeletal cumulative trauma injuries in agriculture: Learning from the mistakes of others. J Agro Med. 1995;2:11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandra AM, Ghosh S, Iqbal R, Sadhu N. A comparative assessment of the impact of different occupations on workers’ static musculoskeletal fitness. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2007;13:271–8. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2007.11076727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De S, Sengupta P, Maity P, Pal A, Dhara PC. Effect of body posture on hand grip strength in adult Bengalee population. J Ex Sci Physiother. 2011;7:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rantanen T, Guralnik JM, Foley D. Midlife hand grip strength as a predictor of old age disability. J Am Med Asso. 1999;281:558–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rantanen T, Era P, Heikkinen E. Maximal isometric strength and mobility among 75-year-old men and women. Age Ageing. 1994;23:132–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ojha P, Kwatra S. Comparative ergonomic assessment of the male and female farm workers involved in rice cultivation. Int J Curr Microb App Sci. 2017;6:3439–46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards L, Palmiter-Thomas P. Grip strength measurement: A critical review of tools, methods, and clinical utility. Crit Rev Phys Rehabil Med. 1996;8:87–09. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohannon RW. Reference values for extremity muscle strength obtained by hand-held dynamometry from adults aged 20 to 79 years. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:26–32. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bimala KR, Gandhi S, Dilbaghi M. Ergonomic evaluation of farm women picking cotton. International Congress on Humanizing Work and Work environment. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borah S. Ludhiana, India: Punjab Agricultural University; 2002. Physiological workload of farm women involved in selected Dairy activities. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersson GBJ, Corlett N, Wilson J, Manenica I. London, UK: Taylor and Francis; 1986. Loads on the spine during sitting The Ergonomics of Working Postures; pp. 309–18. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ansari NA, Sheikh MJ. Evaluation of work posture by RULA and REBA: A case study. IOSR J Mech Civil Eng. 2014;11:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borah S. Ergonomic assessment of drudgery of women worker involved in Cashew nut processing factory in Meghalaya, India. Procedia Manufac. 2015;3:4665–72. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corlett EN, Bishop RP. A technique for assessing postural discomfort. Ergonomics. 1976;19:175–85. doi: 10.1080/00140137608931530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McAtamney L, Corlett EN. RULA: A survey method for the investigation of work-related upper limb disorders. Appl Ergon. 1993;24:91–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-6870(93)90080-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hignett S, McAtamney L. Rapid entire body assessment (REBA) Appl Ergon. 2000;31:201–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ILO. The Hours of Work (Industry) Convention, 1919 (No 1) and the Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices) Convention, 1930 (No 30) Available from: https://wwwiloorg/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---ilo-hanoi/documents/publication/wcms_649367pdf .