Abstract

Purpose

Patients with Lynch syndrome (LS) have a significantly elevated lifetime risk of developing biliary tract cancers (BTCs) compared to the general population. However, few studies have characterized the clinical characteristics, genetic features, or long-term outcomes of mismatch-repair deficient (dMMR) cholangiocarcinomas associated with LS.

Methods

A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained Familial High-Risk GI Cancer Clinic database identified all patients with BTCs evaluated from 2006 to 2016 who carried germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2.

Results

Eleven patients with BTCs were identified: four perihilar, four intrahepatic, one extrahepatic, one gallbladder, and one ampulla of Vater. All patients had underlying germline mutations and a personal history of a LS-associated malignancy, most commonly (63.3%) colorectal cancer. Ten (90.9%) patients were surgically explored, and margin negative resection was possible in seven (63.3%). Chemotherapy (90.9%) and/or chemoradiation (45.5%) was administered to most patients. Among the seven patients presenting with non-metastatic disease who underwent surgical resection with curative intent, the 5-year overall survival rate was 53.3%. The median overall survival for the four patients not treated with curative intent was 17.2 months.

Conclusions

dMMR biliary tract cancers associated with LS are rare but long-term outcomes may be more favorable than contemporaneous cohorts of non-Lynch-associated cholangiocarcinomas. Given the emerging promise of immunotherapy for patients with dMMR malignancies, tumor testing for dMMR followed by confirmatory germline testing should be considered in patients with BTC and a personal history of other LS cancers.

Keywords: Cholangiocarcinoma, Microsatellite instability, Lynch syndrome, Biliary tract cancer, Immunotherapy, Hepatectomy

Introduction

Patients with Lynch syndrome (LS), also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome, have a significantly elevated lifetime risk of developing biliary tract cancers (BTC) compared to the general population [1]. A hallmark of LS is germline defects in mismatch-repair (MMR) proteins which lead to the accumulation of genetic errors and microsatellite instability (MSI). While MSI is an important biomarker in colorectal cancer given its association with an improved prognosis [2], resistance to 5-fluorouracil [3], and sensitivity to immunotherapy [4], few studies have characterized the clinical characteristics, genetic features, or long-term outcomes of mismatch-repair deficient (dMMR) BTCs associated with LS.

Methods

The prospectively maintained Familial High-Risk GI Cancer Clinic and Genetic Counseling databases were queried to identify all patients with BTCs evaluated at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center from 2005 to 2016. MMR testing was performed through a standardized institutional algorithm at the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory, and patients with germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2 were included. Clinicopathologic and genetic features as well as long-term follow-up were reviewed. Overall survival (OS) was defined based on the date of diagnosis while recurrence-free survival (RFS) was defined based on the date of R0/R1 resection. Descriptive statistics were calculated and survival analyses performed using the Kaplan-Meier method with statistical significance assessed via the Mantel-Cox log rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) while survival curves were created using Graphpad Prism 6.0 (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. This retrospective review was approved by the Institutional Review Board and individual patient consent was waived.

Results

Eleven patients with BTCs were identified: four perihilar cholangiocarcinomas, four intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas, one distal extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, one gallbladder cancer, and one adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater (Table 1). The majority (72.7%) presented with either regional nodal or distant metastatic disease. Nine were male and the median age at diagnosis was 57.8 years (range 40–70). Germline mutations were found in MLH1 (n = 6), MSH2 (n = 4), and MSH6 (n = 1). All had a personal history of other LS-associated malignancies, most commonly (63.3%) colorectal cancer and all but one diagnosed prior to the BTC. The median time between the prior malignancy and BTC was 5.9 years (range 0–25.7). All prior LS-associated malignancies had been treated definitively without evidence of recurrence, and no patients were enrolled in a high-risk screening program. The diagnosis was prompted by findings on surveillance imaging in 2 (18.2%), surveillance laboratory tests in 2 (18.2%), or symptoms in 7 (63.6%), of which jaundice was the most common (3 patients).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 11 patients with biliary tract cancers

| Age | Sex | Personal history | Staging† | Treatment | Outcome | Tumor IHC# | Germline testing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resection | Chemo | XRT | ||||||||

| Perihilar | 61 | M | Colon ×2 | T3N2M0 IV | Aborted | Yes | Yes | Died of disease 22.5 months survival | MLH1 | MLH1 K461X (1381A>T) |

| 69 | M | Colon ×2 | T1N0M0 I | R0 | No | No | Alive without disease 51.5 months survival | N/A | MLH1 del exon 1–19 | |

| 67 | M | Colon | T2N0M0 II | R0 | No | No | Intrahepatic recurrence at 33.4 months1 | PMS2 | MLH1, c.2252_2253delAA | |

| Alive with disease at 46.9 months | ||||||||||

| 52 | M | Colon | T2N1M0 IIIC | R0 | Yes | Yes | No evidence of disease 5.8 months survival | MLH1, PMS2 | MLH1 c.2142G>A | |

| Intrahepatic | 52 | M | Colon, lung, sebaceous adenoma | T1N1M0 IIIB | Aborted | Yes | Yes | Died of other causes 11.7 months survival | N/A | MSH2 del exons 9–10 |

| 62 | M | Colon, urothelial ×2, cutaneous SCC, prostate | TxN1M0 IIIB | Yes | Yes | No | Intrahepatic recurrence at 9.6 months | N/A | MSH2 c.2113delG | |

| Died of disease at 24.1 months | ||||||||||

| 54 | M | Prostate2 | T2N1M0 IIIB | Yes | Yes | No | No evidence of disease 9.6 months survival | MSH2, MSH6 | MSH2 del exons 3–8 | |

| 57 | M | Sebaceous adenoma, cutaneous SCC | TxN1M1 IV | Aborted | Yes | Yes | Alive with disease 49.8 months survival | N/A | MLH1, c.116G>A | |

| Distal extrahepatic | 41 | M | Colon, lung | T2NxM13 IV | R1 | Yes | No | Liver/nodal recurrence 35.5 months | N/A | MLH1, c.298C>T (p.Arg100X) |

| Died of disease 49.3 months | ||||||||||

| Gall bladder | 70 | F | Endometrial | T3N1M1 IVB4 | R05 | Yes | No | Died of disease 11.9 months | N/A | MSH2 c.1216C>T |

| Ampullary | 40 | F | Gastric6, CML6 | pT3N0M0 IIA | R0 | Yes | Yes | Died of other causes 135 months survival | MSH6 | MSH6 (c.2147_2148delCA) |

Staging according to AJCC 8th Ed

Loss of expression of following protein on tumor immunohistochemistry

Recurrence initially treated with gemcitabine/Xeloda, then pembrolizumab, now other investigational agents

Diagnosed simultaneously with biliary tract cancer

Peritoneal disease found at time of resection

Moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with lymphovascular and perineural invasion

Simple cholecystectomy

Diagnosed after biliary tract cancer

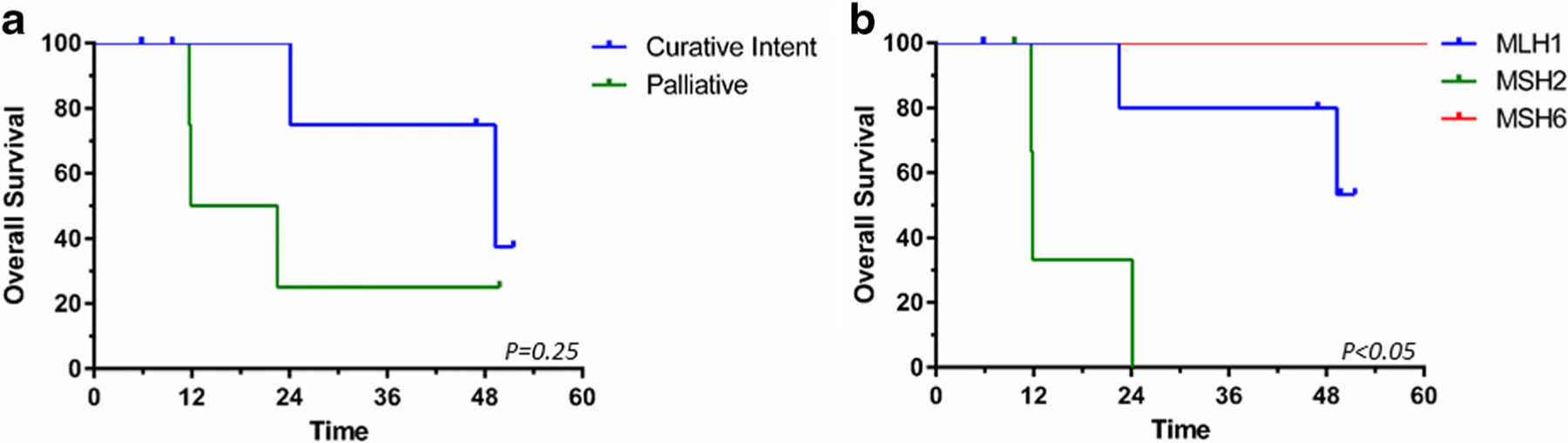

Ten (90.9%) patients were surgically explored, and margin negative resection was possible in seven (63.3%). Chemotherapy (90.9%) and/or chemoradiation (45.5%) was administered to most patients. Among the seven patients presenting with non-metastatic disease who underwent surgical resection with curative intent, the median OS and RFS rates were not reached and 35.6 months, respectively, while the 5-year OS rate was 53.3%. The median overall survival (OS) for the four patients not treated with curative intent was 17.2 months (Fig. 1a). Among the entire cohort, patients with MSH2 mutations had worse OS compared to those with MLH1 mutations (11.9 vs 49.3 months, p = 0.03; Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves based on a curative intent treatment vs palliative therapies and b germline mutation

Discussion

With an estimated lifetime risk of 2%, LS-associated BTCs are rare [5]. Therefore, we leveraged our Familial High-Risk GI Cancer Clinic and Genetic Counseling database to report one of the largest series of BTCs associated with LS, in order to make several important observations. First, LS-associated BTCs tend to occur predominantly among men after the fifth decade and may occur throughout the biliary tract without any site-specific predilection. In addition, all patients had a personal history of another LS-associated neoplasm, most commonly colorectal cancer. Therefore, the diagnosis of BTC in patients with a personal history (or concerning family history) of LS-associated cancers should prompt dedicated tumor and germline genetic testing. Whether patients with LS should undergo screening for BTCs, and whether such intervention is cost-effective, deserves further investigation.

Although the small sample size of this series precludes definitive conclusions, several observations regarding mutation type and tumor location are notable. All intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas were MSH2 deficient while perihilar cholangiocarcinomas were mostly MLH1 deficient. Interestingly, a previous family registry study also failed to identify MSH6-associated cholangiocarcinomas [5]. Although the type of MMR gene mutation is known to influence the penetrance of disease and survival [6], the finding that patients with MLH1 mutations had better OS than those with MSH2 mutations, we believe, is novel.

While it is well known that colorectal cancers with MSI are associated with an improved prognosis, the results of this report suggest that LS-associated BTCs might also be associated with better outcomes. While patients in this series were not immune to nodal or distant metastases, patients with localized disease who underwent surgery with curative intent experienced a 5-year OS rate greater than 50%, significantly better than that which is reported in the literature [7]. Treatment decisions should therefore be made in the context of these patients’ potentially favorable tumor biology and life expectancy. For example, patients who are unable to undergo liver resection may still gain survival benefit with ablative radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy while those who experience recurrence may benefit from ongoing aggressive therapies.

The influence of MSI status on sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents continues to be the subject of investigation. While MSI-high colorectal cancer is thought to be more chemoresistant to fluoropyrimidines, recent reports have highlighted the role of immunotherapy in patients with MSI-high colorectal and hepatobiliary cancers [4] and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently approved the check-point inhibitor pembrolizumab for the treatment of MSI-high solid tumors [8]. Immunotherapy trials in patients with advanced BTCs are ongoing.

Despite the strengths of this report, we acknowledge several limitations, notably, its retrospective, single-institution design, small sample size, and the inclusion of only patients referred to and evaluated in our Familial and High-Risk Cancer Clinic. In addition, our report focused on patients with germline testing whereas other studies have suggested that sporadic events (e.g., DNA methylation) may represent the predominant cause of dMMR and MSI in BTCs [9]. Nevertheless, our case series suggests that long-term outcomes may be more favorable than contemporaneous cohorts of non-Lynch-associated BTCs. Given the emerging promise of immunotherapy for patients with dMMR malignancies and the high proportion of patients with underlying germline mutations, tumor testing for dMMR or MSI followed by confirmatory germline testing should be considered in patients with a BTC and a personal history of other LS-associated cancers.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards This retrospective review was approved by the Institutional Review Board and individual patient consent was waived.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Win AK, Lindor NM, Young JP, Macrae FA, Young GP, Williamson E, et al. Risks of primary extracolonic cancers following colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(18):1363–72. 10.1093/jnci/djs351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vilar E, Gruber SB. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer-the stable evidence. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(3):153–62. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ribic CM, Sargent DJ, Moore MJ, Thibodeau SN, French AJ, Goldberg RM, et al. Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(3):247–57. 10.1056/NEJMoa022289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonadona V, Bonaïti B, Olschwang S, Grandjouan S, Huiart L, Longy M, et al. Cancer risks associated with germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 genes in Lynch syndrome. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2304–10. 10.1001/jama.2011.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maccaroni E, Bracci R, Giampieri R, Bianchi F, Belvederesi L, Brugiati C, et al. Prognostic impact of mismatch repair genes germline defects in colorectal cancer patients: are all mutations equal? Oncotarget. 2015;6(36):38737–48. 10.18632/oncotarget.5395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nathan H, Pawlik TM, Wolfgang CL, Choti MA, Cameron JL, Schulick RD. Trends in survival after surgery for cholangiocarcinoma: a 30-year population-based SEER database analysis. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2007;11(11): 1488–1496; discussion 1496–1497. 10.1007/s11605-007-0282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.FDA approves first cancer treatment for any solid tumor with a specific genetic feature [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm560167.htm

- 9.Silva VWK, Askan G, Daniel TD, Lowery M, Klimstra DS, Abou-Alfa GK, et al. Biliary carcinomas: pathology and the role of DNA mismatch repair deficiency. Chin. Clin. Oncol. [Internet] 2016. [cited 2017 Feb 21];5 Available from: http://cco.amegroups.com/article/view/12260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]