Abstract

Introduction

There remains uncertainty regarding the differences in patient outcomes between monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate (MTURP) and bipolar TURP (BTURP) in the management of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign prostatic obstruction (BPO).

Methods

A systematic literature search was carried out up to March 19, 2019. Methods in the Cochrane Handbook were followed. Certainty of evidence (CoE) was assessed using the GRADE approach.

Results

A total of 59 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 8924 participants were included. BTURP probably results in little to no difference in International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) at 12 months (mean difference −0.24, 95% confidence internal [CI] −0.39–−0.09; participants=2531; RCTs=16; moderate CoE) or health-related quality of life (HRQOL) at 12 months (mean difference −0.12, 95% CI −0.25–0.02; participants=2004, RCTs=11; moderate CoE), compared to MTURP. BTURP probably reduces TUR syndrome (relative risk [RR] 0.17, 95% CI 0.09–0.30; participants= 6,745, RCTs=44; moderate CoE) and blood transfusions (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.30–0.59; participants=5727, RCTs=38; moderate CoE), compared to MTURP. BTURP may carry similar risk of urinary incontinence at 12 months (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.01–4.06; participants=751; RCTs=4; low CoE), re-TURP (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.44–2.40; participants=652, RCTs=6, I2=0%; low CoE) and erectile dysfunction (International Index of Erectile Function [IIEF-5]) at 12 months (mean difference 0.88, 95% CI −0.56–2.32; RCTs=3; moderate CoE), compared to MTURP.

Conclusions

BTURP and MTURP probably improve urological symptoms to a similar degree. BTURP probably reduces TUR syndrome and blood transfusion slightly postoperatively. The moderate certainty of evidence available for primary outcomes suggests no need for further RCTs comparing BTURP and MTURP.

Introduction

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) using a monopolar electrosurgery unit (ESU), also known as monopolar TURP (MTURP), is a well-established surgical management option for bladder outlet obstruction (BPO) due to benign prostate enlargement (BPE), but continues to be associated with significant patient morbidity.1 In light of this, new technologies have been developed with the aim of reducing the risk of complications. In contrast to MTURP, bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate (BTURP) makes use of energy confined between an active electrode (resection loop) and a return electrode situated on the resectoscope tip or sheath, and as such has the advantages of allowing the use of physiological irrigation fluid and lower voltages, theoretically removing the risk of TUR syndrome and reducing thermal damage to surrounding tissues.2–4

Despite the accumulation of evidence comparing MTURP and BTURP over the last decade, there has been ongoing uncertainty regarding the differences between these two surgical methods in terms of surgical outcomes. Previous systematic reviews that have compared these surgical methods5–10 do not incorporate the significant number of recently published randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and have not consistently adhered to the methodological standards of Cochrane, including the publication of a review protocol, implementation of a rigorous search strategy, application of GRADE, and use of patient-focused outcomes. The objective of this review was to compare the effects of BTURP and MTURP.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This systematic review and meta-analysis were based on a published protocol.11 We performed a comprehensive search using multiple databases, including Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE Ovid, and EMBASE Ovid. The search strategy was up to date as of March 19, 2019. To identify unpublished trials or trials in progress, we searched the following sources: ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov), the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://www.who.int/ictrp/en), and the abstract proceedings for the European Association of Urology (EAU) (https://urosource.uroweb.org/urosource?page=1&search=&types=abstract) and American Urological Association (AUA) (https://www.auanet.org/research/annual-meetingabstracts) conferences from 2009–2018. Two review authors (CEA, MS) independently screened all relevant records and classified studies in accordance with criteria for each provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review for Interventions.12 We only searched for RCTs because they are likely to provide the most reliable evidence.

Types of participants

We included participants aged >18 years with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to BPO. BPO was defined as bladder outlet obstruction secondary to BPE.

Types of intervention

We compared BTURP with MTURP.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcomes of the review were urological symptoms (as measured by the International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS] questionnaire score at 12 months), bother (as measured by health-related quality of life [HRQOL] questionnaire score at 12 months) and TUR syndrome. The secondary outcomes were urinary incontinence at 12 months, postoperative blood transfusion, incidence of second TURP (i.e., re-do TURP), and erectile function (as measured by the International Index of Erectile Function questionnaire score [IIEF-5] at 12 months.

Assessment of the risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CEA, MS) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study on a per-outcome basis. We resolved disagreements by discussion and consensus. We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane “risk of bias” assessment tool. We judged the risk of bias domains as low-risk, high-risk, or unclear risk, and evaluated the individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.12

Data collection and data extraction

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors (CA, MS) using data extraction forms created in Microsoft Word. We resolved any disagreements by discussion or, if required, by consultation with a third review author (MIO). We combined data from individual studies for meta-analysis where interventions were similar enough. We have expressed dichotomous data as a risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous outcomes measured on the same scale we estimated the intervention effect using the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI. We summarized data using a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was analyzed using the Chi-squared test, with an alpha of 0.1 used for statistical significance, and the I2 test. I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% generally correspond to low, medium, and high levels of heterogeneity. Where we have encountered heterogeneity, we attempted to determine possible reasons for it by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

We expected the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity and we planned to carry out subgroup analyses with investigation of interactions:

- Prostate volume (large vs. small prostate volume, with specific categories for these defined by primary authors)

- Patient age (older vs. younger patients, with specific categories for these defined by primary authors)

We undertook sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect sizes by restricting analysis to the following:

- Taking into account risk of bias

- Very long or large trials to establish the extent to which they dominate the results

Summary of findings table

We presented the overall certainty of evidence for each outcome according to GRADE, which accounts for five criteria not only related to internal validity (study limitations, imprecision, publication bias), but also to external validity, such as directness of results.

Results

Search results

We identified 1249 records through an electronic database search. We identified 40 records through hand-searching of other sources. After removal of 432 duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of 857 records and excluded 647 records. We screened 210 full text records and excluded 81 records that did not meet the inclusion criteria. We included a total of 59 RCTs.4,13–70 We did not identify studies awaiting classification or ongoing RCTs. The flow of literature through the assessment process is shown in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Included studies

All studies were RCTs that compared BTURP to MTURP. Characteristics of the included studies are detailed in the Appendix (available at cuaj.ca). Four studies were multi-institutional, 4,20,24,48 and all other studies were single-institution. The included studies were performed between 2002 and 2016. The followup duration varied from the immediate postoperative period only to 48 months27 and 60 months65 postoperatively.

Participants

We included 8924 randomized participants. Of these, 6745 contributed data to the primary and secondary outcomes. The mean age of the included participants ranged from 59.0 (BTURP) and 61.0 (MTURP)27 to 74.1 (BTURP) and 73.8 (MTURP)64. The mean prostate volume ranged from 39 cc (BTURP and MTURP)29 to 82.4 cc (BTURP) and 82.6 cc (MTURP).21

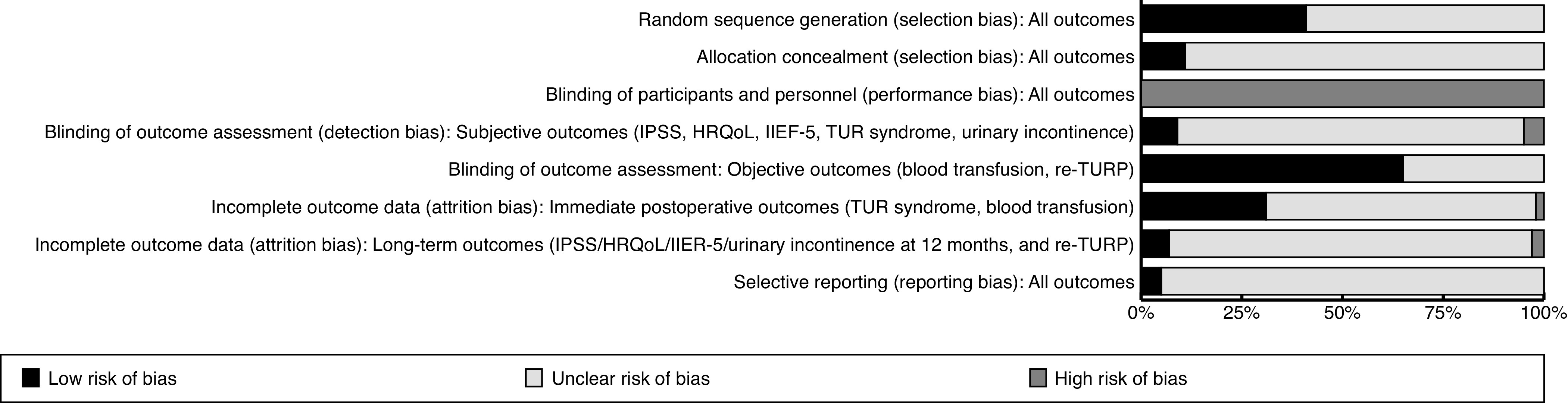

Risk of bias in included studies

Assessments of risk of bias are summarized in Fig. 2. Further details on the assessment of risk of bias were stated in the review published in the Cochrane Library.

Fig. 2A.

Risk of bias summary: Review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Summary of findings tables

We summarized the results in the summary of findings tables in accordance with GRADE methodology (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of findings: BTURP compared to MTURP for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic obstruction

| Patient or population: Men with lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic obstruction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting: Hospital | |||||

| Intervention: BTURP | |||||

| Comparison: MTURP | |||||

|

| |||||

| Outcomes | No of participants (studies) followup | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

|

| |||||

| Risk with MTURP | Risk difference with BTURP | ||||

| Urological symptoms (IPSSa at 12 monthsa) | 2531 (16 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

— | Mean urological symptoms (IPSS at 12 months) was 6.4 Weighted mean=6.4 |

MD 0.24 lower (0.39 lower to 0.09 lower) |

| Bother (HRQoLc at 12 months) | 2004 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

— | Mean bother (HRQOL at 12 months) was 1.7 Weighted mean=1.7 |

MD 0.12 lower (0.25 lower to 0.02 higher) |

| TUR syndrome | 6745 (44 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

RR 0.17 (0.09 to 0.30) | Study population | |

| 24 per 1000 Weighed mean number of events=1.8 |

20 fewer per 1000 (22 fewer to 17 fewer) | ||||

| Urinary incontinence at 12 months | 751 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,d |

RR 0.20 (0.01 to 4.06) | Study population | |

| 5 per 1000 Weighted mean number of events=0.5 |

4 fewer per 1000 (5 fewer to 16 more) | ||||

| Blood transfusion | 5727 (38 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

RR 0.42 (0.30 to 0.59) | Study population | |

| 48 per 1000 Weighted mean number of events=3.7 |

28 fewer per 1000 (34 fewer to 20 fewer) | ||||

| Re-TURP | 652 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,d |

RR 1.02 (0.44 to 2.40) | Study population | |

| 34 per 1000 Weighted mean number of events=1.8 |

1 more per 1000 (19 fewer to 48 more) | ||||

| Erectile function (IIEF-5e score at 12 months) | 321 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

— | Mean erectile function (IIEF-5 score at 12 months) was 19.2 Weighted mean=19.2 |

MD 0.88 higher (0.56 lower to 2.32 higher) |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence: | |||||

| High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. | |||||

| Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | |||||

| Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | |||||

| Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

IPSS questionnaire scores range from 0 to 35, with higher values signalling more severe lower urinary tract symptoms; the minimum clinically important difference was defined as 4.

Downgraded by one level for study limitations: blinding of operating surgeon considered unlikely in all trials; method of randomisation, allocation concealment, and blinding of outcome assessment unclear in > 50% of included trials.

HRQOL questionnaire scores range from 0 to 6, with higher values signalling poorer quality of life.

Downgraded by one level for imprecision: wide confidence intervals, very small numbers of events for urinary incontinence and re-TURP.

IIEF-5 questionnaire scores range from 5–25, with higher values signalling better erectile function; the minimum clinically important difference was defined as 4.

BTURP: bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate; CI: confidence interval; HRQOL: health-related quality of life; IIEF-5: International Index of Erectile Function; IPSS: International Prostate Symptoms Score; MD: mean difference; MTURP: monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; TUR: transurethral resection; TURP: transurethral resection of the prostate.

Effect of the intervention

Primary outcomes

Urological symptoms as measured by IPSS at 12 months

We included 16 studies with 2531 participants. BTURP probably results in similar improvements in urological symptoms, as measured by IPSS at 12 months (MD −0.24, 95% CI −0.39–−0.09, moderate certainty of evidence [CoE]) compared to MTURP.

Bother as measured by HRQOL score at 12 months

We included 11 studies with 2004 participants. BTURP probably results in similar improvements in bother, as measured by the HRQoL scores at 12 months (MD −0.12, 95% CI −0.25–0.02, moderate CoE) compared to MTURP.

TUR syndrome

We included 44 studies with 6745 participants. BTURP probably reduces TUR syndrome events slightly (RR 0.17, 95% CI 0.09–0.30, moderate CoE) compared to MTURP.

Secondary outcomes

Urinary incontinence at 12 months

We included 4 studies with 751 participants. BTURP may result in similar rates of urinary incontinence at 12 months (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.01–4.06, low CoE) compared to MTURP.

Blood transfusion

We included 38 studies with 5727 participants. BTURP probably reduces blood transfusions slightly (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.30–0.59, moderate CoE) compared to MTURP.

Re-TURP

We included six studies with 652 participants. BTURP may result in similar rates of re-TURP (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.44–2.40, low CoE) compared to MTURP.

Erectile function as measured by IIEF-5 score at 12 months

We included three studies with 321 participants. BTURP probably results in similar erectile function as measured by the IIEF-5 at 12 months (MD 0.88, 95% CI −0.56–2.32, moderate CoE) compared to MTURP.

Subgroup analyses

Of the included RCTs, Kumar 201345 was the only study to include specific subgroup analyses by prostate volume. They defined small prostates as >20 cc to <50 cc and large prostates as 50–80 cc. They observed no significant difference in effect for urological symptoms, bother, TUR syndrome, or erectile function. They did observe a significant difference in effect for blood transfusion in men with large prostates. The number of events of postoperative blood transfusion in men with large prostates was six who had undergone MTURP (n=31) compared to one blood transfusion for BTURP (n=27). We did not identify any analysis or data within the included RCTs that would allow for subgroup analysis by patient age.

Sensitivity analysis

In light of the judged high risk of attrition bias seen with Demirdag 2016,26 with 37 patients excluded due to loss to followup or missing data and the significant differential loss to followup (23/59 participants lost to followup for BTURP vs. 14/59 for MTURP), we performed sensitivity analysis where this study was excluded from the meta-analysis for the outcomes it assessed. The exclusion of Demirdag 201626 from the meta-analyses did not result in any significant change in the effect size that would impact on the overall conclusions of the analysis. In light of the size of the largest included RCT by Al-Rawashdah 2017,18 with 497 included participants, we performed sensitivity analysis where this study was excluded from the meta-analysis for the outcomes it assessed. The exclusion of Al-Rawashdah 201718 from the meta-analyses did not result in any significant change in the effect size that would impact on the overall conclusions of the analysis.

Discussion

BTURP and MTURP probably result in similar improvements in urological symptoms and bother. BTURP probably reduces TUR syndrome and postoperative blood transfusion slightly compared to MTURP. BTURP and MTURP probably do not differ in terms of erectile function. The moderate CoE available for urological symptoms, bother, TUR syndrome, blood transfusion, and erectile function suggests there is no need for further RCTs comparing BTURP and MTURP for these outcomes. BTURP and MTURP may also have similar effects on postoperative urinary incontinence and the need for re-TURP, but the low CoE for these outcomes means that they deserve further study in the form of prospective RCTs which incorporate standardized and clinically meaningful definitions, as well as sufficient duration of followup.

There have been a number of previously published systematic reviews and meta-analyses comparing BTURP and MTURP.5–10 While the focus of this review has been limited to a smaller number of key primary and secondary outcomes, its findings are in keeping with the conclusions of previous reviews that no clinically relevant differences exist in the short-term (up to 12 months) effectiveness (urological symptoms as measured by IPSS, bother as measured by HRQOL score) or in short-term incidence of adverse events (urinary incontinence, need for re-TURP, erectile function), but BTURP may be preferable due to a more favorable perioperative safety profile (lower incidence of TUR syndrome and blood transfusion rates).

The favorable perioperative safety profile of BTURP may have potential implications in reducing morbidity and mortality associated with the surgical treatment of BPO. BTURP may allow for longer resection times and resection of larger prostates without the risk of TUR syndrome. The allowance for longer resections may also permit further time to ensure sufficient coagulation time to secure hemostasis, thereby reducing the risks of bleeding. These features may be particularly beneficial for urologists in training.

Compared to all relevant previous meta-analyses, our present systematic review and meta-analysis represents the largest body of evidence by far, being based on 59 RCTs. The largest systematic review published prior to this was by Omar and colleagues9 and included 24 RCTs. One of the major strengths of the present meta-analysis is that the strict methodology described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions12 was used and that GRADE was applied for evaluating the CoE.

However, this review has several limitations. A potential source of bias is the clinical heterogeneity across subgroups of interventions. For instance, BTURP represents a diverse range of interventions with differences in equipment, magnitude of energy, and techniques.3 The various bipolar systems represent distinct technological advancements based on different electrophysiological principles regarding current flow, and in this review, there was insufficient data to perform sensitivity or subgroup analysis on how the different types of BTURP compared to each other. There was also heterogeneity of outcome measurement and reporting, with some studies not reporting how outcomes were measured. In particular, the primary outcome of TUR syndrome was inconsistently defined, with some studies failing to provide a clear definition. Accordingly, the incidence of TUR syndrome varied across studies. Furthermore, despite our stringent inclusion criteria and comprehensive search strategy, it is possible that not all eligible RCTs were included in the databases that was searched. For some of the older reports of RCTs, there were limited usable data, and despite contacting trial authors for further information, we did not always receive a response.

To answer the multiple-choice questions associated with this article, go to: www.cuasection3credits.org/cuajdecember2020. This program is an Accredited Self-Assessment Program (Section 3) as defined by the Maintenance of Certification Program of The Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons of Canada, and approved by the Canadian Urological Association. Remember to visit MAINPORT (www.mainport.org/mainport/) to record your learning and outcomes. You may claim a maximum of 1 hour of credit.

Supplementary Information

Fig. 2B.

Risk of bias graph: Review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. HRQol: health-related quality of life; IIEF: International Index of Erectile Function; IPSS: International Prostate Symptom Score; TURP: transurethral resection of the prostate.

Acknowledgement

This article is based on a Cochrane Review published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) 2019, Issue 12, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009629.pub4 (see www.cochranelibrary.com for information). Cochrane Reviews are regularly updated as new evidence emerges and in response to feedback, and the CDSR should be consulted for the most recent version of the review.

Footnotes

The following is an abridged republication of a published Cochrane Review, reprinted with permission.

Appendix available at cuaj.ca

See related commentary on page 431

Competing interests: The authors report no competing personal or financial interests related to this work.

The authors would like to thank Professor Philipp Dahm, Coordinating Editor, Cochrane Urology, for his advice and guidance with regards to Cochrane review methodology. We are grateful to the following individuals for their kind efforts in assisting with study translation, assessment of eligibility and data extraction for foreign language articles: Lena Lantsova, Euan Fisher, Christopher Carroll, Sergio Fdez-Pello Montes, Jae Hung, and Professor Phillipp Dahm

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Reich O, Gratzke C, Bachmann A, et al. Morbidity, mortality, and early outcome of transurethral resection of the prostate: A prospective, multicenter evaluation of 10 654 patients. J Urol. 2008;180:246–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Issa MM. Technological advances in transurethral resection of the prostate: Bipolar vs. monopolar TURP. J Endourol. 2008;22:1587–95. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faul P, Schlenker B, Gratzke C, et al. Clinical and technical aspects of bipolar transurethral prostate resection. Scandinav J Urol Nephrol. 2008;42:318–23. doi: 10.1080/00365590802201300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mamoulakis C, Schulze M, Skolarikos A, et al. Midterm results from an international multicenter, randomized controlled trial comparing bipolar with monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate. Eur Urol. 2013;63:667–76. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lourenco T, Pickard R, Vale L, et al. Alternative approaches to endoscopic ablation for benign enlargement of the prostate: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2008;337:a449. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39575.517674.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mamoulakis C, Ubbink DT, de la Rosette JJ. Bipolar versus monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Urol. 2009;56:798–809. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahyai SA, Gilling P, Kaplan SA, et al. Meta-analysis of functional outcomes and complications following transurethral procedures for lower urinary tract symptoms resulting from benign prostatic enlargement. Eur Urol. 2010;58:384–97. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke N, Whelan JP, Goeree L, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of transurethral resection of the prostate vs. minimally invasive procedures for the treatment of benign prostatic obstruction. Urology. 2010;75:1015–22. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omar MI, Lam TBL, Cameron A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical effectiveness of bipolar compared to monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate. BJU Int. 2014;113:24–35. doi: 10.1111/bju.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornu JN, Ahyai S, Bachmann A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of functional outcomes and complications following transurethral procedures for lower urinary tract symptoms resulting from benign prostatic obstruction: An update. Eur Urol. 2015;67:1066–96. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamoulakis C, Sofras F, de la Rosette J, et al. Bipolar vs. monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic obstruction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD009629. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009629.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Accessed Aug. 27, 2019]. Available at: www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abascal Junquera JM, Cecchini Rosell L, Salvador Lacambra C, et al. Bipolar vs. monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate: Perioperative analysis of the results. Actas Urologicas Españolas. 2006;30:661–6. doi: 10.1016/S0210-4806(06)73515-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acuña-López JA, Hernández-Torres AU, Gómez-Guerra LS, et al. Bipolar vs. monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate: Intraoperative and postoperative result analysis. Revista Mexicana de Urología. 2010;70:146–51. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad M, Khan H, Masood I, et al. Comparison of bipolar and monopolar cautery use in TURP for treatment of enlarged prostate. J Ayub Medical College Abbottabad. 2016;28:758–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akçayöz M, Kaygisiz O, Akdemir O, et al. Comparison of transurethral resection and plasmakinetic transurethral resection applications with regard to fluid absorption amounts in benign prostate hyperplasia. Urol Int. 2006;77:143–7. doi: 10.1159/000093909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akman T, Binbay M, Tekinarslan E, et al. Effects of bipolar and monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate on urinary and erectile function: A prospective randomized comparative study. BJU Int. 2013;111:129–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Rawashdah SF, Pastore AL, Salhi YA, et al. Prospective randomized study comparing monopolar with bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate in benign prostatic obstruction: 36-month outcomes. World J Urol. 2017;35:1595–1601. doi: 10.1007/s00345-017-2023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bahadzor B, Fadzli I, Nazri J, et al. Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing the use of plasmakinetic resection of prostate vs. conventional transurethral resection of prostate in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int J Urol. 2006;13:A21–2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertolotto F, Naselli A, Vigliercio G, et al. Prospective randomized study confronting monopolar vs. bipolar TURP: 6 months followup outcome. Eur Urol Suppl. 2007;6:137. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(07)60456-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhansali M, Patankar S, Dobhada S, et al. Management of large (>60 g) prostate gland: PlasmaKinetic Superpulse (bipolar) vs. conventional (monopolar) transurethral resection of the prostate. J Endourol. 2009;23:141–5. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Q, Zhang L, Liu YJ, et al. Bipolar transurethral resection in saline system vs. traditional monopolar resection system in treating large-volume benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol Int. 2009;83:55–9. doi: 10.1159/000224869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Q, Zhang L, Fan QL, et al. Bipolar transurethral resection in saline vs. traditional monopolar resection of the prostate: Results of a randomized trial with a 2-year followup. BJU Int. 2010;106:1339–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi SH, Lee JH, Seo JH, et al. The comparison of PK tissue management system TURP with conventional monopolar TURP. Eur Urol Suppl. 2006;5:271. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(06)60997-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Elia G, Mastrangeli B. A randomized prospective trial of bipolar vs. standard monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate. Eur Urol Suppl. 2004;3:235. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(04)90902-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demirdag C, Citgez S, Tunc B, et al. The clinical effect of bipolar and monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate more than 60 mL. Urology. 2016;98:132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Sio M, Autorino R, Quarto G, et al. Gyrus bipolar vs. standard monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate: A randomized prospective trial. Urology. 2006;67:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eaton A, Francis R, Duncan N, et al. A randomized prospective study comparing the performance of the 4 mm plasma kinetic loop against standard monopolar TURP in prostates 4–100 g size. Eur Urol Suppl. 2004;3:145. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(04)90567-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egui Rojo MA, Redon Galvez L, Alvarez Ardura M, et al. Monopolar versus bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate: Evaluation of the impact on sexual function. J Sex Med. 2017;14:e107–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Assmy A, ElSha AM, Mekkawy R, et al. Erectile and ejaculatory functions changes following bipolar vs. monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate: A prospective randomized study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2018;50:1569–76. doi: 10.1007/s11255-018-1950-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erturhan S, Erbagci A, Seckiner I, et al. Plasmakinetic resection of the prostate vs. standard transurethral resection of the prostate: A prospective randomized trial with 1-year followup. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007;10:97–100. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fagerström T, Nyman CR, Hahn RG. Complications and clinical outcome 18 months after bipolar and monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate. J Endourol. 2011;25:1043–9. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geavlete B, Georgescu D, Multescu R, et al. Bipolar plasma vaporization vs. monopolar and bipolar TURP: A prospective, randomized, long-term comparison. Urology. 2011;78:930–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghozzi S, Ghorbel J, Ben Ali M, et al. [Bipolar vs. monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate: A prospective randomized study]. Progrès en Urologie. 2014;24:121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2013.08.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giulianelli R, Albanesi L, Attisani F, et al. Comparative randomized study on the efficaciousness of endoscopic bipolar prostate resection vs. monopolar resection technique: 3-year followup. Archivio Italiano di Urologia e Andrologia. 2013;85:86–91. doi: 10.4081/aiua.2013.2.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goh MHC, Gulur DM, Okeke AA, et al. Bipolar vs. monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic obstruction: A randomized prospective trial with one-year followup. BJU Int. 2009;103:17. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.02.1868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He JW, Xie J, Chen GY, et al. [Therapeutic efficacy of bipolar plasmakinetic resection compared with transurethral resection on benign prostate hyperplasia]. Chinese J Endourol. 2010;4:302–4. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho HS, Yip SK, Lim KB, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing monopolar and bipolar transurethral resection of prostate using transurethral resection in saline (TURIS) system. Eur Urol. 2007;52:517–22. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang X, Wang L, Wang XH, et al. Bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate causes deeper coagulation depth and less bleeding than monopolar transurethral prostatectomy. Urology. 2012;80:1116–20. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iori F, Franco G, Leonardo C, et al. Bipolar transurethral resection of prostate: Clinical and urodynamic evaluation. Urology. 2008;71:252–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kadyan B, Kankalia SP, Sabale VP, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing safety and efficacy of bipolar resection vs. standard transurethral resection of prostate. Indian J Urol. 2014;30:s155. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JY, Moon KH, Yoon CJ, et al. [Bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate: A comparative study with monopolar transurethral resection]. Kor J Urol. 2006;47:493–7. doi: 10.4111/kju.2006.47.5.493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komura K, Inamoto T, Takai T, et al. Incidence of urethral stricture after bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate using TURis: Results from a randomized trial. BJU Int. 2015;115:644–52. doi: 10.1111/bju.12831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kong CH, Ibrahim MF, Zainuddin ZM. A prospective, randomized clinical trial comparing bipolar plasma kinetic resection of the prostate vs. conventional monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:429–32. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.57163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar A, Vasudeva P, Kumar N, et al. A prospective randomized comparative study of monopolar and bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate and photoselective vaporization of the prostate in patients who present with benign prostatic obstruction: A single-center experience. J Endourol. 2013;27:1245–53. doi: 10.1089/end.2013.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin MS, Wu JC, Hsieh HL, et al. Comparison between monopolar and bipolar TURP in treating benign prostatic hyperplasia: 1-year report. Mid-Taiwan J Med. 2006;11:143–8. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mei HB, Wang F, Chang JP, et al. [Comparison of clinical effect of transurethral resection and bipolar plasma kinetic resection of benign prostatic hyperplasia]. Chinese J Endourol. 2010;4(3):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Méndez-Probst CE, Nott L, Pautler SE, et al. A multicenter, single-blind, randomized controlled trial comparing bipolar and monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5:385–9. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.10199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michielsen DP, Debacker T, De Boe V, et al. Bipolar transurethral resection in saline: An alternative surgical treatment for bladder outlet obstruction? J Urol. 2007;178:2035–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nasution P, Nur Budaya T, Duarsa G, et al. Comparative study of monopolar vs. bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate vs. thulium laser vaporesection of the prostate (ThuVaRP) in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia and urinary retention: Randomized, multicenter study. J Clin Urol. 2017;10:69. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nuhoglu B, Ayyildiz A, Karagüzel E, et al. Plasmakinetic prostate resection in the treatment of benign prostate hyperplasia: Results of 1-year followup. Int J Urol. 2006;13:21–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patankar S, Jamkar A, Dobhada S, et al. PlasmaKinetic Superpulse transurethral resection vs. conventional transurethral resection of prostate. J Endourol. 2006;20:215–9. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qian P, Mingtao Li. Study of transurethral bipolar plasma kinetic resection operation for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia patients and its effect on sexual function. Chin J Androl. 2014;28:52–4. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rojo MAE, Galvez LR, Ardura MA, et al. Comparison of monopolar versus bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate: Evaluation of the impact on sexual function. Andrologia. 2018;212:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rose A, Suttor S, Goebell PJ, et al. Transurethral resection of bladder tumors and prostate enlargement in physiological saline solution (TURIS). A prospective study. Urologe A. 2007;46:1148–50. doi: 10.1007/s00120-007-1391-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seckiner I, Yesilli C, Akduman B, et al. A prospective randomized study for comparing bipolar plasmakinetic resection of the prostate with standard TURP. Urol Int. 2006;76:139–43. doi: 10.1159/000090877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shaik JA, Devraj R, Ram Reddy CH. Bipolar vs. monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic obstruction: a randomized prospective study. Ind J Urol. 2017;33(Suppl 1) [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh H, Desai MR, Shrivastav P, Vani K, et al. Bipolar vs. monopolar transurethral resection of prostate: Randomized controlled study. J Endourol. 2005;19:333–8. doi: 10.1089/end.2005.19.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singhania P, Nandini D, Sarita F, et al. Transurethral resection of prostate: A comparison of standard monopolar vs. bipolar saline resection. Int Braz J Urol. 2010;36:183–9. doi: 10.1590/S1677-55382010000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stucki P, Marini L, Mattei A, et al. Bipolar vs. monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate: A prospective, randomized trial focusing on bleeding complications. J Urol. 2015;193:1371–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.08.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Symons S, Browning A, Chahal R. A comparative study of the Gyrus plasmakinetic electrosurgical system vs. conventional loop electroresection (TURP) for the treatment of bladder outflow obstruction: Six-month data. Eur Urol Suppl. 2002;1:169. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(02)80660-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Terrone C, ScoJone C, Cracco C, et al. Bipolar vs. monopolar TURP: A randomized study. Eur Urol Suppl. 2006;5:235. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(06)60854-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang D, Lu J, Xia S, et al. [A comparative study of transurethral plasma kinetic resection vs. transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia]. J Clin Urol. 2007;22:520–2. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu WJ, Wang XH, Wang HP, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of bipolar plasmakinetic technique compared with transurethral resection on benign prostate hyperplasia. Nat Med J China. 2005;85:3365–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xie CY, Zhu GB, Wang XH, et al. Five-year followup results of a randomized controlled trial comparing bipolar Plasmakinetic and monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate. Yonsei Med J. 2012;53:734–41. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.4.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xin G, Xingqiao W, Jianguang Q, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing gyrus bipolar and standard monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate. J Endourol. 2007;21(Supplement 1):A102. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xin L, Zhu J, Yao B. Transurethral prostate ion bipolar electrosurgical excision efficacy. Med J Comm. 2009;23:685–7. doi: 10.1080/09528820903189350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xue S, Ma HQ, Ge JP, et al. [A comparative study of two different surgical procedures for benign prostatic hyperplasia]. J Med Postgrad. 2008;21:283–6. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang S, Lin WC, Chang HK, et al. Gyrus plasmasect: Is it better than monopolar transurethral resection of prostate? Urol Int. 2004;73:258–61. doi: 10.1159/000080838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yousef AA, Suliman GA, Elashry OM, et al. A randomized comparison between three types of irrigating fluids during transurethral resection in benign prostatic hyperplasia. BioMed Central Anesthesiol. 2010;10:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.