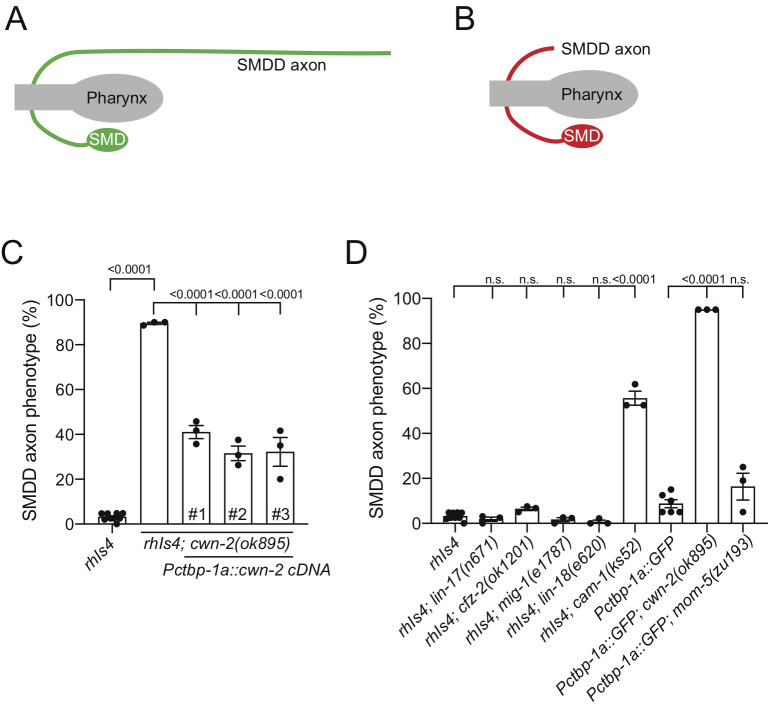

Figure 1. The Wnt ligand CWN-2 and Ror receptor CAM-1 control SMDD axonal development.

(A-B) Schematic of a wild-type (A) and defective (B) SMDD axon where the axon is not visible in the sublateral nerve cord. (C) Quantification of the SMDD axonal phenotype in the cwn-2(ok895) mutant and rescue using three independent transgenic lines expressing Pctbp-1::cwn-2 cDNA (#1-3). (D) Quantification of the SMDD axonal phenotype of mutant alleles for Wnt receptors LIN-17, CFZ-2, MIG-1,LIN-18, CAM-1 and MOM-5. SMDD development was analyzed with either the rhIs4(Pglr-1::GFP) or Pctbp-1a::GFP reporter and scored defective if the SMDD axon was not visible in the sublateral nerve cord. Data presented as mean ± S.E.M (bar) of at least three biological replicates (black dots) by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction. n>60 axons per bar. n.s. – not significant.

Description

CWN-2 is one of five C. elegans Wnt ligands, with known roles in neuron migration, axon guidance and nerve ring placement (reviewed in (Sawa and Korswagen, 2013)). CWN-2 is highly expressed in the SMDD neurons (Kennerdell et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2019), and therefore we were interested in determining whether CWN-2 regulates SMDD axonal development.

We used the cwn-2(ok895) deletion allele to analyze SMDD axonal development. We found that loss of cwn-2 caused a defective SMDD axonal phenotype, where axons do not extend along the dorsal sublateral cord, suggesting that the axons did not exit the nerve ring due to defects in axon outgrowth or guidance (Figure 1A-C). To ensure that this phenotype was due to the loss of CWN-2 function, we transgenically expressed cwn-2 cDNA driven by the ctbp-1a promoter, which drives expression in SMDD and ten other head neurons (Sherry et al., 2020). Expressing cwn-2 using this promoter partially rescues the defective axonal phenotype (Figure 1C). This suggests that CWN-2 controls SMDD development in an autocrine manner and/or non-autonomously from other head neurons.

Next, we investigated which Wnt receptor controls SMDD axonal development. There are six Wnt receptors encoded in the C. elegans genome: four Frizzled receptors (LIN-17, CFZ-2, MIG-1 and MOM-5,), one Ror receptor (CAM-1) and one Ryk receptor (LIN-18) (Sawa and Korswagen, 2013). We analyzed the effect of loss-of-function mutations for each receptor and found that loss of cam-1, but not the other receptors, caused defective SMDD axonal development (Figure 1D). CAM-1 was previously shown to function as a CWN-2 receptor for SIA, SIB and RMED/V posterior-directed neurite outgrowth (Kennerdell et al., 2009; Song et al., 2010; Wang and Ding, 2018). The SIA, SIB, RMED/V and SMDD motor neuron cell bodies are all positioned in the nerve ring and extend posteriorly-directed axons (White et al., 1986). Therefore, our data show that CWN-2 and CAM-1 have a common role in controlling axon extension in posteriorly-directed lateral or sublateral axons.

Methods

C. elegans strains were grown using standard growth conditions on NGM agar at 20 °C and fed with Escherichia coli OP50. Neuroanatomical reporter strains used – rhIs4 [Pglr-1::GFP] and rpEx1739[Pctbp-1a::GFP]. Homozygous mom-5 mutant animals were selected based on the Unc phenotype caused by the linked unc-13(e1091) mutation. Day two adult hermaphrodites were anesthetized with 0.2% levamisole hydrochloride on 5% agarose pads for anatomical scoring. Schematics of axonal defects are shown instead of images as bright GFP expression in multiple cell bodies around the pharynx obscure imaging of axon defects. Refer to (Sherry et al., 2020) for images of the SMDD axons posterior to the pharynx. ‘Defective SMDD axonal phenotype (%)’ indicates the percentage of SMDD axons that do not extend along the dorsal sublateral cord. Two SMDD axons (L and R) were scored per animal. For cwn-2(ok895) rescue experiments, transgenic animals were compared to the cwn-2(ok895) mutant. Three biological replicates were performed, and statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests.

Cloning was performed using Takara In-Fusion® restriction-free cloning. The Pctbp-1a::cwn-2 rescue construct was generated by cloning the cwn-2 1083 bp cDNA sequence, amplified from C. elegans cDNA, into a Pctbp-1a::GFP vector to replace the GFP sequence (Sherry et al., 2020). Rescue constructs were injected into rhIs4; cwn-2(ok895) mutant backgrounds at 2 ng/μl with Punc-122::GFP (20 ng/μl) as injection marker.

Reagents

Strains

HRN169 rhIs4 [Pglr-1::GFP] III

HRN498 rhIs4 III; cwn-2(ok895) IV

RJP4553 rhIs4 III; cwn-2(ok895) IV; rpEx2027 [Pctbp-1a::cwn-2] line #1

RJP4554 rhIs4 III; cwn-2(ok895) IV; rpEx2028 [Pctbp-1a::cwn-2] line #2

RJP4555 rhIs4 III; cwn-2(ok895) IV; rpEx2029 [Pctbp-1a::cwn-2] line #3

RJP4485 mig-1(e1787) I; rhIs4 III

RJP4486 lin-17(n671) I; rhIs4 III

RJP4534 rhIs4 III; cfz-2(ok1201) V

RJP4688 cam-1(ks52) II; rhIs4 III

RJP4715 rhIs4 III; lin-18(e620) X

RJP4076 rpEx1739 [Pctbp-1a::GFP]

RJP4598 cwn-2(ok895) IV; rpEx1739 [Pctbp-1a::GFP]

RJP4624 mom-5(zu193) unc-13(e1091)/hT2 III; rpEx1739 [Pctbp-1a::GFP]

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Cori Bargmann for the lin-18(e620) allele and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota), which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440), for strains.

Funding

This work was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship to T.S, and the National Health and Medical Research Council (GNT1137645 to R.P).

References

- Kennerdell JR, Fetter RD, Bargmann CI. Wnt-Ror signaling to SIA and SIB neurons directs anterior axon guidance and nerve ring placement in C. elegans. Development. 2009 Nov 01;136(22):3801–3810. doi: 10.1242/dev.038109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa H, Korswagen HC. Wnt signaling in C. elegans. WormBook. 2013 Dec 01;:1–30. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.7.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Zhang B, Sun H, Li X, Xiang Y, Liu Z, Huang X, Ding M. A Wnt-Frz/Ror-Dsh pathway regulates neurite outgrowth in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2010 Aug 12;6(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.R., Santpere, G., Reilly, M., Glenwinke, L., Poff, A., McWhirter, R., Xu, C., Weinreb, A., Basavaraju, M., and Steven J Cook, A.B., Alexander Abrams, Berta Vidal, , Cyril Cros, Ibnul Rafi, Nenad Sestan, Marc Hammarlund, Oliver Hobert, David M. Miller III. 2019. Expression profiling of the mature C. elegans nervous system by single-cell RNA-Sequencing. BioRxiv.

- Wang J, Ding M. Robo and Ror function in a common receptor complex to regulate Wnt-mediated neurite outgrowth in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Feb 20;115(10):E2254–E2263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717468115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1986 Nov 12;314(1165):1–340. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]