Abstract

Objective:

Transcatheter mitral valve repair with the MitraClip is used for the symptomatic management of mitral regurgitation (MR). The challenge is reducing MR while avoiding an elevated mitral valve gradient (MVG). This study assesses how multiple MitraClips used to treat MR can affect valve performance.

Methods:

Six porcine mitral valves were assessed using an in vitro left heart simulator in the native, moderate-to-severe MR, and severe MR cases. MR cases were tested in the no-MitraClip, one-MitraClip, and two-MitraClip configurations. Mitral regurgitant fraction (MRF), MVG, and effective orifice area (EOA) were quantified.

Results:

Native MRF, MVG, and EOA were 14.22%, 2.59 mmHg, and 1.64 cm2, respectively. For moderate-to-severe MR, MRF, MVG, and EOA were 34.07%, 3.31 mmHg, and 2.22 cm2, respectively. Compared to the no-MitraClip case, one MitraClip decreased MRF to 18.57% (p<0.0001) and EOA to 1.50 cm2 (p=0.0002). MVG remained statistically unchanged (3.44 mmHg). Two MitraClips decreased MRF to 14.26% (p<0.0001) and EOA to 1.36 cm2 (p=0.0001). MVG remained unchanged (3.29 mmHg). For severe MR, MRF, MVG, and EOA were 59.79%, 4.98 mmHg, and 2.73 cm2, respectively. Compared to the no-MitraClip case, one MitraClip decreased MRF to 30.72% (p<0.0001) and EOA to 1.82 cm2 (p<0.0001); MVG remained unchanged (4.03 mmHg). MVG remained statistically unchanged. Two MitraClips decreased MRF to 23.10% (p<0.0001) and EOA to 1.58 cm2 (p<0.0001); MVG remained statistically unchanged (3.82 mmHg). Both MR models yielded no statistical difference between one and two MitraClips.

Conclusions:

There is limited concern regarding elevation of MVG when reducing MR using one or two MitraClips, though two MitraClips did not significantly continue to reduce MRF.

Introduction

The mitral valve (MV) is located between the left atrium and left ventricle and is composed of two leaflets connected to papillary muscles (PMs) via chordae tendineae. Mitral regurgitation (MR) is characterized by impaired leaflet coaptation that results in backward flow of blood from the left ventricle to the left atrium during systole. MR is present in 1.7% of the general population and in 9.3% of those aged 75 and older [1]. With MR, ventricular and atrial remodeling occurs, and resulting effects include atrial fibrillation and ultimately heart failure; therefore, an intervention to treat MR is required [2].

Current approved treatments are composed of surgical replacement and repair techniques, including annuloplasty and edge-to-edge repair. High-risk patients were previously limited to guideline-directed medical therapy, but transcatheter interventions are on the rise due to their non-invasive nature.

The surgical Alfieri edge-to-edge repair offers a simple solution to MR, where a stitch is placed to connect the two MV leaflets, effectively creating a double orifice and reducing MR. As this procedure is invasive, an alternative is transcatheter mitral valve repair using MitraClip (Santa Clara, CA), which offers this same solution via a less invasive approach by clipping together the anterior and posterior MV leaflets and is tailored to patients with moderate-to-severe or severe MR [3].

The effect of MitraClip in functional MR (FMR) patients with heart failure was assessed in the MITRA-FR and COAPT randomized trials, where MitraClip plus guideline-directed medical therapy was compared to guideline-directed medical therapy alone [4, 5]. The COAPT trial demonstrated a significant reduction in heart failure hospitalization and mortality in the MitraClip group [4, 5], whereas MITRA-FR showed no significant difference in these outcomes with use of MitraClip [4, 6]. Overall, MitraClip can benefit symptomatic heart failure patients with at least moderate-to-severe FMR [7, 8]. In other studies, MitraClip also demonstrated favorable results in patients with degenerative MR [9–11]. Thus, MitraClip has gained FDA approval for treating degenerative MR and FMR.

Despite the importance of MitraClip in reducing MR, the issue of sufficiently reducing MR may result in multiple MitraClip implantations with the potential risk of causing iatrogenic mitral stenosis (MS) with an increase in mitral valve gradient (MVG) [12–15]. This cause of unwanted MS is one of the limitations of the MitraClip procedure. In some cases, even a single MitraClip can cause mild MS [16]. Specifically, patients with procedure-related MS have poorer long-term outcomes than those with residual MR, which becomes increasingly important during the procedure when considering the placement of a second or even a third MitraClip when MR is not sufficiently decreased [12, 13]. In the EVEREST II trial, two MitraClips were implanted in 42% of the subjects [17]. Previous clinical studies show that with the central-clip concept, vena contracta of ≥ 7.5 mm and presence of two broad jets are associated with the need for a second MitraClip, but these criteria are mere correlations that lack in vitro assessment [12, 18]. This leads to the question of when more than one MitraClip should be deployed, as more MitraClips can further reduce MR but also cause MVG to further increase [12].

The objective of this study is to understand how multiple MitraClips affect the hemodynamic performance of the MV for various degrees of MR severity with a specific focus on increases in MVG.

Methods

Mitral Valve

Porcine MVs were used in this study, as they are used in preclinical trials and are acceptable human analogs in context of hemodynamic evaluation [19–21]. Six porcine valves were obtained from Bay Packing (Lancaster, Ohio) from pigs weighing approximately 250 lbs. Heart masses and valve dimensions are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Each valve was sutured to a plate that was cut to its annulus size using 32 MedSci Global Nylon Monofilament sutures, and procedures are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Porcine Mitral Valve Preparation. (A) The heart is first cut open to access the mitral valve. (B) The valve is removed from the heart (top left), and a template of the annulus is created (top right) to customize the mounting plate (bottom left) and accommodating gasket (bottom right). (C) The valve is sutured to the annulus plate, and commissure-to-commissure (CC) and septolateral (SL) dimensions are noted. (D) and (E) An attachment piece is sutured to each papillary muscle for fixation to the papillary control mechanism.

Inducing MR

Each valve was modeled in native (unaltered) and pathophysiological states of two MR severities. Mitral regurgitant fraction (MRF) is used to characterize mitral regurgitation and is the ratio of regurgitant flow to forward flow [22]. MR severities in this study include moderate-to-severe and severe, with MRFs of 30–50%, and ≥ 50%, respectively [14, 23].

MR was achieved via cutting chordae tendineae from the P2 scallop and monitoring MRF, as shown in Figure 2. Analysis of each valve occurs in the order of native, moderate-to-severe MR, then severe MR.

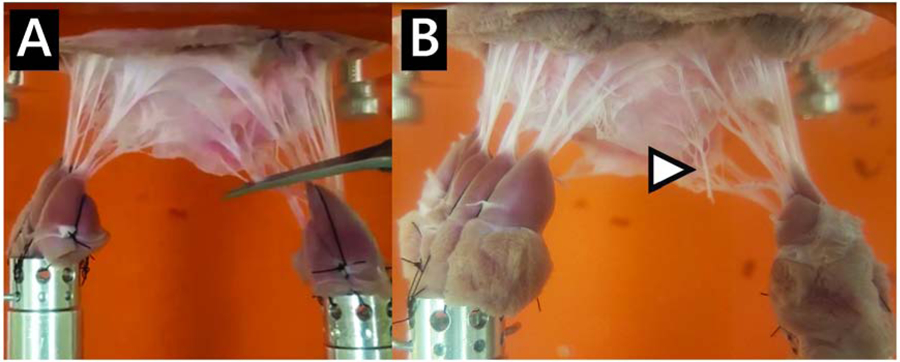

Figure 2:

Chordal cutting for the MR Model. (A) Chordae connecting the papillary muscles to the P2 scallop are cut to induce MR. (B) Severed chordae can be seen at the newly free edge of the leaflet.

MitraClip

Abbott’s MitraClip NT was used in this study, and the device with measured dimensions is show in Figures 3a, b, and c. MitraClips were centered on the leaflets for each clipped configuration, as shown in Figures 3d and e. Analysis of each valve for the MR cases occurs in the order of unclipped, one MitraClip, then two MitraClips.

Figure 3:

Abbott’s MitraClip NT. (A) Opened MitraClip. (B) and (C) Front and side views of the MitraClip with measured dimensions. Central MitraClip placement for one (D) and two (E) MitraClips.

Left Heart Simulator

In order to test the porcine MV, a pulsatile in vitro left heart simulator was developed, containing the components of the left heart—left atrium, MV, left ventricle, aortic valve, and systemic compliance and resistance. The left atrium and ventricle were pneumatic bladder pumps, and contraction and relaxation occurred via air pressure provided by a compressor that was regulated by solenoid valves as controlled by a LabVIEW program, similar to previous experiments [22, 24–27]. A compliance chamber was installed downstream the aortic valve to mimic arterial compliance. Changes in ventricular and atrial pressures were implemented to maintain cardiac output after for each configuration. Transducers were also incorporated, allowing for high fidelity pressure and flow hemodynamic measurements to quantify parameters, including MRF, MVG, and effective orifice area (EOA). The left heart simulator and data collection were controlled by a LabVIEW program. A schematic of the flow loop is shown Figure 4.

Figure 4:

Schematic of the left heart simulator.

A custom MV chamber was designed to hold the MV, including a unique system allowing for fixed placement of the PM as used in previous experiments [22, 25, 26, 28–31]. The mounted valve and description of PM control rod is shown in Figure 5. Overall, this setup allowed for physiological and pathophysiological modeling of the MV with various degrees of regurgitation. The valve in the aortic position was the 21mm Medtronic Hancock II bioprosthetic aortic valve. The working fluid used was 60–40 water-glycerin mixture to achieve the density (1060 kg/m3) and kinematic viscosity of blood (3.88 cSt).

Figure 5:

Mitral Valve Mounting. (A) Mounted mitral valve. (B) Mounted mitral valve, highlighting papillary muscle fixation to the papillary muscle control rods. (C) Full view of mounted mitral valve. (D) and (E) Papillary muscle control rods are used to fix the papillary muscles, allowing control of placement in the apical/basal, anterior/posterior, and septal/lateral directions.

Imposed Hemodynamic Conditions

Heart rate was 60 beats per minute, systolic ventricular pressure was 120 mmHg, atrial systole was 12% of the cardiac cycle, and cardiac output was 3 L/min.

Flow rate and transvalvular and ventricular pressure data were recorded for each configuration. Configurations included the number of MitraClips (0, 1, and 2) and the state of the MV (native, moderate-to-severe, and severe MR). MRF, EOA, and MVG were calculated.

Hemodynamic Characterization

The hemodynamic parameters include MRF, EOA, and MVG.

MRF was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where stroke volume is defined as the volume of forward flow and regurgitant volume is defined as the volume of backward flow.

EOA assesses valve orifice opening and was computed using the Gorlin Equation. Though there are limitations of the Gorlin Equation in general, its use in context of the double orifice is consistent with similar in vitro studies as well as in the EVEREST clinical trial [22, 26, 32, 33]. The Gorlin Equation is as follows:

| (2) |

where Q represents the root mean square mitral valve flow over the same averaging interval of the pressure gradient. The pressure gradient (∆P) is defined as the average difference between atrial and ventricular pressure during forward flow and is also defined as MVG.

Statistical Methods

A total of six valves were tested, and data was collected at 100 Hz per cycle for 60 cycles. Hemodynamic parameters MRF, MVG, and EOA were calculated for each valve, for each cycle, across each of the seven previously discussed configurations. Statistical software used was SAS Version 9.4. Repeated measure analysis was applied to study the effects of the seven configurations on the three hemodynamic parameters. PROC MIXED was applied considering several covariance structures, and the best covariance structure for each measure was picked by Akaike information criterion. From each repeated measure analysis, 12 comparative effects were estimated. Therefore, 36 effects in total were estimated from the analyses of the three measures. With Bonferroni adjustment of multiple comparison, p<0.0014 was considered statistically significant.

Results

MRF, MVG, and EOA are shown in Figure 6. Representative MVG and flow rate waveforms for valve 1 for each configuration are shown in Supplemental Figure 1.

Figure 6:

Hemodynamic Data. Box and whisker plots: (A) MRF – mitral regurgitant fraction, (B) MVG – mitral valve gradient, (C) EOA – effective orifice area. Bar graphs: (D) MRF, (E) MVG, (F) EOA; error bars represent standard deviation. Mod-sev: Moderate-to-severe MR. MC: MitraClip. * p<0.0001 compared to native; § p=0.0002 compared to native; ‡ p<0.0001 compared to unclipped within the same MR grade; # p=0.0001 compared to unclipped within the same MR grade; † p=0.0002 compared to unclipped within the same MR grade.

Native Valve (No Induced MR)

For the native valve, average MRF, MVG, and EOA were 14.22 ± 0.49%, 2.59 ± 0.89 mmHg, and 1.64 ± 0.35 cm2, respectively.

Moderate-to-Severe MR

For MRF, the no-MitraClip configuration was statistically higher than native (14.22 ± 0.49%), at 34.07 ± 0.74% (p<0.0001). However, there was no statistically significant difference between clipped configurations and native (14.22 ± 0.49%), with 18.57 ± 0.59% for one MitraClip (p=0.09) and 14.26 ± 0.50% with two MitraClips (p=0.97). MRF was statically lower with MitraClips than no MitraClip (p<0.0001) but did not statistically differ between two MitraClips and one (p=0.09).

For MVG, all moderate-to-severe configurations were not statistically different from native (2.59 ± 0.89 mmHg), with 3.31 ± 1.28 mmHg for no MitraClip (p=0.22), 3.44 ± 0.97 mmHg for one MitraClip (p=0.15), and 3.29 ± 0.45 mmHg for two MitraClips (p=0.23). MVG did not statistically differ with one or two MitraClips compared to no MitraClip (p=0.81 and p=0.98) or between two MitraClips and one (p=0.79).

For EOA, the no-MitraClip configuration did not statistically differ from native (1.64 ± 0.35 cm2), at 2.22 ± 0.57 cm2 (p=0.01). EOA was also not statistically smaller with MitraClips than native, with 1.50 ± 0.23 cm2 for one MitraClip (p=0.52) and 1.36 ± 0.13 cm2 for two MitraClips (p=0.20). EOA was statistically smaller with one MitraClip (p=0.0002) and two MitraClips (p=0.0001) than no MitraClip but did not statistically differ between two MitraClips and one (p=0.41).

Severe MR

For MRF, the no-MitraClip configuration was statistically higher than native (14.22 ± 0.49%), at 59.79 ± 0.81% (p<0.0001). However, there was no statistically significant difference between clipped configurations and native (14.22 ± 0.49%), with 30.72 ± 0.63% for one MitraClip (p=0.002), and 23.10 ± 0.61% for two MitraClips (p=0.004). MRF was statistically lower with MitraClips than no MitraClip (p<0.0001) but did not statistically differ between two MitraClips and one (p=0.16).

For MVG, the no-MitraClip configuration was statistically higher than native (2.59 ± 0.89 mmHg), at 4.98 ± 1.03 mmHg (p=0.0002). However, there was no statistically significant difference between clipped configurations and native (2.59 ± 0.89 mmHg), with 4.03 ± 1.11 mmHg for one MitraClip (p=0.02), and 3.82 ± 0.84 mmHg for two MitraClips (p=0.03). MVG did not statistically differ with one MitraClip (p=0.09) or two MitraClips (p=0.05) compared to no MitraClip or between two MitraClips and one (p=0.70).

For EOA, the no-MitraClip configuration was statistically larger than native (1.64 ± 0.35 cm2), at 2.73 ± 0.32 cm2 (p<0.0001). However, there was no statistically significant difference between clipped configurations and native, with 1.82 ± 0.27 cm2 for one MitraClip (p=0.35) and 1.58 ± 0.18 cm2 for two (p=0.74). EOA was statistically smaller with MitraClips than no MitraClip (p<0.0001) but did not statistically differ between two MitraClips and one (p=0.15).

Discussion

No MitraClip

Inducing moderate-to-severe MR led to an increase of MRF from native (increase from 14.22% to 34.07%). With this, MVG and EOA were not statistically different from native.

When MRF was increased to severe from native (increase from 14.22% to 59.79%), MVG and EOA were greater than native (increase of 2.39 mmHg and 1.09 cm2, respectively). This is due to the higher forward flow required to maintain the target cardiac output.

One MitraClip

For moderate-to-severe MR, one MitraClip statistically decreased MRF compared to no MitraClip (decrease from 34.07% to 18.57%), and this value is statistically equal to native, showing that the device is efficient in reducing MR grade. MVG did not statistically differ from native or the no-MitraClip case, showing that MVG may not be effected by MitraClip in this case, and MitraClip may not harm the valve in context of elevated MVG that leads to MS. EOA was statistically reduced after placement of one MitraClip (decrease of 0.72 cm2) but did not statistically differ from native. This shows that though EOA may be reduced post-MitraClip, the device may not harm the valve in context of a statistically significant reduction in EOA below the native behavior.

For severe MR, one MitraClip statistically decreased MRF compared to no MitraClip (decrease from 59.79% to 30.72%), and this value was statistically equal to native, showing that the device can effectively reduce higher MR grades as well. MVG did not statistically differ from the native or no-MitraClip case, again showing that MVG may not be harmful in causing MS. With one MitraClip, EOA statistically decreased compared to no MitraClip (decrease of 0.91 cm2) to that of native. This decrease is expected, as the free leaflet was immobilized to some degree which restricted flow behavior.

Two MitraClips

For moderate-to-severe MR, two MitraClips also led to a statistically significant decrease of MRF compared to no MitraClip (decrease from 35.07% to 14.26%) to a value statistically equal to native, again showing that the device is efficient in reducing MR grade. However, two MitraClips did not statistically further reduce MRF. This is because a single MitraClip was effective in significantly reducing MR, and the addition of a second MitraClip was not able to further reduce MR. MVG did not statistically differ with two MitraClips compared to the native, no-MitraClip, or one-MitraClip cases. This shows that MVG may not be affected by MitraClip in this case, and additional MitraClips may not elevate MVG. Similar to the one-MitraClip case, EOA was statistically smaller with two MitraClips than no MitraClip (decrease of 0.86 cm2) but did not statistically differ from native. EOA also did not statistically change with two MitraClips compared to one. Overall, these results show that use of the device for moderate-to-severe MR reduces MRF to native while MVG and EOA are not impaired compared to native, where one and two MitraClips yielded the same outcome.

For severe MR, two MitraClips led to a statistically significant decrease of MRF by more than half compared to no MitraClip (decrease from 59.79% to 23.10%). This value statistically equal to native and did not statistically change with two MitraClips compared to one. This is likely because a second centrally place MitraClip could not further reduce regurgitation due to presence of two remaining regurgitant orifices that were relatively large. MVG did not statistically differ from the native, no-MitraClip, or one-MitraClip case, again showing that MitraClip may not harm the valve in context of elevated MVG. EOA was statistically smaller with two MitraClips than no MitraClip (decrease of 1.15 cm2) but did not statistically differ from native. EOA was also not statistically different with one MitraClip compared to two MitraClips. This shows that though the device may reduce EOA, the reduction does not fall statistically below the native, meaning forward flow function is not impaired. Overall, these results show that use of the device for severe MR reduces MRF to native while MVG and EOA are not impaired compared to native, similar to the moderate-to-severe case, and one and two MitraClips yielded the same outcome.

Perspectives

The XTR is another generation of MitraClip that is also approved for use. The device features arms that are 3 mm longer along with an additional two rows of grippers per arm for an increase of coaptation area by 44% compared to the NT [34]. Thus, it may be possible that the new generation MitraClip may further decrease levels of regurgitation; however, further testing is necessary. Though results of the present study did not indicate risk of elevated MVG, it is possible that the XTR may lead to elevated MVG as a result of the great increase in coaptation area (therefore a possible decrease in effective orifice area). It is important to consider individual leaflet anatomy, as the XTR may be more suitable for longer MV leaflets than shorter leaflets due to the increase in arm length [34]. The EXPAND trial underway will provide more information on patient response to the XTR.

From a hemodynamic perspective (based on in vitro work such as ours), MitraClip deployment led to decreased MRF and acceptable MVG. At present, in low-to-intermediate risk patients with primary MR, the best approach is surgical repair. This procedure provides excellent long-term results, as mortality and morbidity in experienced medical centers are minimal. In cases where surgical repair cannot be performed (for technical reasons) or the likelihood of a successful procedure is low, then other options should be considered. A new clinical trial, REPAIR MR, will be investigating use of MitraClip for patients at moderate surgical risk (as the high-risk trials showed promising results). Though elevated MVG tends to be correlated with higher incidence of atrial fibrillation, the relationship between MVG and development of atrial fibrillation in context of MV repair – specifically edge-to-edge repair – is not well established [35]. Regardless of potential increase in MVG or later development of atrial fibrillation, many MR patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation still benefited from MitraClip therapy as reported by Velu et al [36]. Unfortunately, in an in vitro setting, atrial fibrillation is not possible to simulate, hence the reliance on clinical data.

In this study, the problem of increased MVG after MitraClip deployment was assessed versus the decrease in regurgitation levels. The results showed a decrease in MRF while keeping MVG within acceptable (minimal stenosis) range. Based on these results, there seems to be no concern for elevated MVG when using up to two MitraClip devices, as examined in this study, to reduce MRF. However, caution must always be exercised to take individual leaflet anatomy, patient-specific parameters and MR characteristics in determining the treatment path.

Study Limitations

One limitation of this study is that porcine MVs were used as opposed to human MVs. Also, the Gorlin Equation may not be appropriate for evaluating a double orifice, as previously stated.

Other limitations of the heart model are fixed PM location and the annulus of each valve being mounted to a rigid plate. Though this is consistent with previous in vitro studies [22, 25, 26, 28–31], the papillary muscles contract in the heart along with the myocardium, and annular motion is dynamic.

As stated previously, MitraClip location was centered throughout the study. While we have shown that the second MitraClip (also placed centrally and adjacent to the first) does not significantly impact pressure gradient, this may not be necessarily true if the second clip was located non-centrally [37]. Further studies need to be conducted to examine two clips spaced significantly apart where the double orifice is sub-divided into a triple orifice scenario.

Lastly, this study assessed MitraClip for a very specific case of degenerative P2 flail in a highly controlled manner and did not yet investigate functional MR, where MR is driven by combinations of enlargement of the left ventricle, PM displacement, and annular dilatation. Future studies need to be conducted to examine functional MR mechanisms.

Conclusions

The effect of MitraClip on MV hemodynamics was tested in this study. Figure 7 summarizes the findings, along with Supplemental Video 1. In moderate-to-severe and severe MR, use of one or two MitraClips reduced MRF and MVG. In both MR models, there was no statistically significant difference between the use of one and two MitraClips for any parameter.

Figure 7:

The effect of MitraClip on balancing regurgitation with transmitral pressure gradient.

This study shows that MitraClip significantly reduces MR severity, with no significant concern regarding elevation of MVG when using one or two MitraClips. Further studies are underway to maximize benefit of MitraClip use, including analysis of newer MitraClip generations and assessment of other similar clipping devices.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Representative Mitral Flow and Pressure Gradient Curves (Valve 1)

Supplemental Table 1: Valve Measurements. SL: septo-lateral dimension. CC: commissure-to-commissure dimension. Averages are represented as mean ± standard deviation.

Supplemental Video 1: Short video summary of the article with narration.

Central Picture.

There is limited concern for elevated mitral valve gradient when using 1 or 2 MitraClips.

Perspective Statement.

Iatrogenic mitral stenosis is a concern with use of MitraClip to treat moderate-to-severe and severe mitral regurgitation. With use of up one or two MitraClips, there is limited concern for elevated mitral valve gradient or reduced effective orifice area that lead to mitral stenosis.

Central Message.

With use of one or two MitraClips to treat moderate-to-severe and severe mitral regurgitation, there is limited concern for procedure-related elevation of mitral valve gradient.

Funding:

This research was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HL119824 and the American Heart Association under award number 19POST34380804.

Abbreviations, symbols and terminology

- MV

Mitral valve

- PM

Papillary muscle

- MR

Mitral regurgitation

- FMR

Functional mitral regurgitation

- MVG

Mitral valve gradient

- MS

Mitral stenosis

- MRF

Mitral regurgitant fraction

- EOA

Effective orifice area

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: L.P. Dasi reports having patent applications filed on novel polymeric valves, vortex generators and superhydrophobic/omniphobic surfaces. The other authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, et al. , Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2018. 137(12): p. e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boudoulas KD, et al. , Factors determining left atrial kinetic energy in patients with chronic mitral valve disease. Herz, 2003. 28(5): p. 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aspirus Heart & Vascular Institute. TMVR - Mitral Valve Repair. 2013. [cited 2020; Available from: https://www.valvedisease.org/index.cfm?pid=23&pageTitle=TMVR---Mitral-Valve-Repair.

- 4.Obadia J-F, et al. , Percutaneous repair or medical treatment for secondary mitral regurgitation. New England Journal of Medicine, 2018. 379(24): p. 2297–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone GW, et al. , Transcatheter mitral-valve repair in patients with heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freemantle N, et al. , 32nd EACTS Annual Meeting clinical trials update: ART, IMPAG, MITRA-FR and COAPT. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juillière Y, Lessons from MITRA-FR and COAPT studies: Can we hope for an indication for severe functional mitral regurgitation in systolic heart failure? Archives of cardiovascular diseases, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Wood S FDA Extends MitraClip Indication to Include Functional MR. 2019; Available from: https://www.tctmd.com/news/fda-extends-mitraclip-indication-include-functional-mr.

- 9.Feldman T, et al. , Final Results of the EVEREST II Randomized Controlled Trial of Percutaenous and Surgical Reduction of Mitral Regurgitation. American College of Cardiology, 2014. 63(12 Supplement): p. A1682. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman T, et al. , Percutaneous repair or surgery for mitral regurgitation. New England Journal of Medicine, 2011. 364(15): p. 1395–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kar S, et al. , The EVEREST II REALISM Continued Access study: effectiveness of transcatheter reduction of significant mitral regurgitation in surgical candidates. American College of Cardiology, 2013. 61(10 Supplement): p. E1959. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giordano A, et al. , Implantation of more than one MitraClip in patients undergoing transcatheter mitral valve repair: friend or foe? Journal of Cardiology and Therapy, 2014. 1(6): p. 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neuss M, et al. , Elevated mitral valve pressure gradient after MitraClip implantation deteriorates long-term outcome in patients with severe mitral regurgitation and severe heart failure. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, 2017. 10(9): p. 931–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishimura RA, et al. , 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, 2014. 63(22): p. e57–e185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itabashi Y, et al. , Different indicators for postprocedural mitral stenosis caused by single-or multiple-clip implantation after percutaneous mitral valve repair. Journal of cardiology, 2018. 71(4): p. 336–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh GD, Smith TW, and Rogers JH, Mitral stenosis due to dynamic clip-leaflet interaction during the MitraClip procedure: Case report and review of current knowledge. Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine, 2017. 18(4): p. 287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstrong EJ, et al. , Echocardiographic predictors of single versus dual MitraClip device implantation and long-term reduction of mitral regurgitation after percutaneous repair. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions, 2013. 82(4): p. 673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alegria-Barrero E, et al. , Concept of the central clip: when to use one or two MitraClips. EuroIntervention, 2014. 9(10): p. 1217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leroux AA, et al. , Animal models of mitral regurgitation induced by mitral valve chordae tendineae rupture. The Journal of Heart Valve Disease, 2012. 21(4): p. 416–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fann JI, et al. , Beating heart catheter-based edge-to-edge mitral valve procedure in a porcine model: efficacy and healing response. Circulation, 2004. 110(8): p. 988–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goar FG St., et al. , Endovascular edge-to-edge mitral valve repair: short-term results in a porcine model. Circulation, 2003. 108(16): p. 1990–1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padala SM, Mechanics of the mitral valve after surgical repair-an in vitro study. 2010, Georgia Institute of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grayburn PA, et al. , Defining “severe” secondary mitral regurgitation: emphasizing an integrated approach. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2014. 64(25): p. 2792–2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatoum H, et al. , Aortic sinus flow stasis likely in valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve implantation. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 2017. 154(1): p. 32–43. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jimenez JH, et al. , A saddle-shaped annulus reduces systolic strain on the central region of the mitral valve anterior leaflet. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 2007. 134(6): p. 1562–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jimenez-Mejia JH, The loading and function of the mitral valve under normal, pathological and repair conditions: an in vitro study. 2006, Georgia Institute of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatoum H, et al. , Impact of leaflet laceration on transcatheter aortic valve-in-valve washout: BASILICA to solve neosinus and sinus stasis. 2019. 12(13): p. 1229–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madu EC and D’Cruz IA, The vital role of papillary muscles in mitral and ventricular function: echocardiographic insights. Clinical cardiology, 1997. 20(2): p. 93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritchie J, et al. , The material properties of the native porcine mitral valve chordae tendineae: an in vitro investigation. Journal of Biomechanics, 2006. 39(6): p. 1129–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Espino DM, et al. , The role of Chordae tendineae in mitral valve competence. The Journal of heart valve disease, 2005. 14(5): p. 603–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gooden SC-M, In Vitro Modeling of Mitral Valve Hemodynamics: Significance of Left Atrium Function in the Normal and Repaired Mitral Valve with Simulated MitraClip. 2019, The Ohio State University. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dumesnil JG and Yoganathan AP, Theoretical and practical differences between the Gorlin formula and the continuity equation for calculating aortic and mitral valve areas. The American journal of cardiology, 1991. 67(15): p. 1268–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farouque HMO, Clark DJ, and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Interventional Procedure Overview of Percutaneous Mitral Valve Leaflet Repair for Mitral Regurgitation. 2018. p. 1–16.

- 34.Mackensen GB and Reisman MJSH, Edge-to-Edge Repair of the Mitral Valve with the Mitraclip System: Evolution of Leaflet Grasping Technology. 2019. 3(4): p. 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma W, et al. , Elevated gradient after mitral valve repair: the effect of surgical technique and relevance of postoperative atrial fibrillation. 2019. 157(3): p. 921–927. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velu JF, et al. , Comparison of outcome after percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip in patients with versus without atrial fibrillation. 2017. 120(11): p. 2035–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaefer U, Frerker C, and Kreidel F, Simultaneous double clipping delivery guide strategy for treatment of severe coaptation failure in functional mitral regurgitation. Heart, Lung and Circulation, 2015. 24(1): p. 98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Representative Mitral Flow and Pressure Gradient Curves (Valve 1)

Supplemental Table 1: Valve Measurements. SL: septo-lateral dimension. CC: commissure-to-commissure dimension. Averages are represented as mean ± standard deviation.

Supplemental Video 1: Short video summary of the article with narration.