Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Many breast cancer survivors (BCS) experience persistent cognitive and psychological changes associated with their cancer and/or treatment and that have limited treatment options. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the feasibility and effects of a Kirtan Kriya meditation (KK) intervention on cognitive and psychological symptoms compared to an attention control condition, classical music listening (ML), in BCS.

Materials and Methods:

A randomized control trial design was used. Participants completed eight-week interventions. Cognitive function and psychological symptoms were measured at baseline and post-intervention. Mixed analysis of variance models were examined for all cognitive and psychological outcomes.

Results:

27 BCS completed the study. Intervention adherence was 88%. Both groups improved in perceived cognitive impairments, cognition related quality of life, verbal memory, and verbal fluency (p’s < 0.01). There were no significant group by time effects for cognitive and psychological outcomes, except stress. The ML group reported lower stress at time 2 (p < 0.05).

Conclusion:

KK and ML are feasible, acceptable, and cost-effective interventions that may be beneficial for survivors’ cognition and psychological symptoms. Both interventions were easy to learn, low cost, and required just 12 minutes/day. Meditation or music listening could offer providers evidence-based suggestions to BCS experiencing cognitive symptoms.

Keywords: breast cancer survivors, cognitive functioning, Kirtan Kriya, meditation, music listening, stress

1.0. Introduction

Cancer is often considered a chronic condition 1 with long-term physical, psychological, and cognitive effects following diagnosis and treatment 2. Many breast cancer survivors (BCS) experience cognitive changes associated with their cancer and/or treatment that are often identified as the most distressing, disruptive, and disabling effects 3. These changes can last months to decades after treatment ends 4,5. Estimates vary, but up to 78% of BCS experience ongoing cancer related cognitive impairment (CRCI) 6 that can negatively impact quality of life and social and occupational functioning 7. Self-reports of CRCI are highly correlated with other psychological symptoms following cancer diagnosis and treatment 8 including feelings of distress 9, stress 10, loneliness 11, and fatigue 12. Even though these symptoms are independently assessed, they often co-occur in BCS 11.

Long-term cognitive and psychological symptoms are prevalent and life-altering problems that have limited treatment options 13. Few interventions have been evaluated to improve these symptoms; those that have are time and resource intensive, typically requiring participants to travel to study sites to receive interventions 13. This highlights a need for accessible interventions for survivors with CRCI. In fact, a recent qualitative study with BCS reported that cost, distance to travel, and time intensiveness were the biggest barriers for their participation in CRCI related interventions 14. Mind-body techniques such as meditation, are accessible, low-tech, and low-cost interventions that have been applied to oncology populations for decades 15 with evidence of significant effects on psychological symptoms in BCS in particular16. There is growing evidence supporting the positive impact of meditation techniques on neurological functioning17, stress reduction, and improvements in wellbeing in populations at risk for cognitive decline 18 and for improving quality of life, depression, anxiety, and perceived cognitive functioning in BCS 19–21. However, the majority of the programs evaluated required in-person attendance at weekly classes lasting several hours, thereby limiting accessibility.

To address these barriers our team adapted a mantra-based kundalini meditation technique, Kirtan Kriya (KK), used in persons with subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment that may prevent or reverse cognitive impairment in older adults 22, and emerging evidence supports improvements in mood, psychological well-being, stress, and favorable neurobiological changes 18,22–26. This program can be delivered remotely and is simple, cost effective, accessible, and requires just 12 minutes a day. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to determine the feasibility of delivering an eight-week daily KK intervention program remotely to BCS. Secondly, we aimed to evaluate the preliminary effects of the program on cognitive function (performance and perceived, primary outcomes), psychological functioning (anxiety, depression, stress; secondary outcomes), fatigue (secondary outcome), and self-efficacy (secondary outcome) in BCS compared to classical music listening (ML). We used ML as an attention control group in order to control for the effect of relaxation alone on the primary and secondary outcomes, and to be consistent with the intervention protocols previously published using this modality 18,23–26.

2.0. Materials and Methods

A feasibility study with a two-group parallel random assignment experimental design was used. No critical changes were made to methods after the trial commenced. Informed consent was obtained for experimentation with human subjects, all study procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and under the approval and supervision of the University of Texas Institutional Review Board approval (protocol #2018-05-0155).

2.1. Participants

The sample size reflects the primary aim of this study— to determine the feasibility of implementing the intervention protocol within a new clinical population, thus a power analysis was not utilized. Women with a history of breast cancer and treated with chemotherapy were recruited (October 2018- July 2019) using study flyers posted at a local breast cancer resource center, and local oncology clinics. Potential participants contacted the research office and were screened for eligibility via telephone. Eligibility criteria included: women who were 21–75 years of age; with a history of breast cancer (stage I-IV); were three months to six years post adjuvant chemotherapy; reported cognitive deficits (a minimum of five cognitive symptoms occurring “sometimes” or more, per the Perceived Deficits Questionnaire 27); identified as any ethnic or racial group; and were able to speak and read English. Those on hormonal therapies and anti- human epithelial receptor 2 (HER-2) therapy were also included. Exclusion criteria included: metastases to the brain; a pre-cancer history of unmanaged sleep disorders, severe cognitive impairments (provider diagnosed), or other neurological or psychiatric disorders that could interfere with completion of the cognitive testing; self-reported regular meditation practice (more than 1 time a week for at least a month); previous diagnosis of inflammatory breast cancer or history of other inflammatory diseases (e.g. diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis); and systemic steroids or biologic response modifiers use within 30 days of enrollment. The later exclusion criteria were chosen based on the inflammatory biomarkers that were also measured in this study, but not reported here.

2.2. Data Collection and Study Procedures

After participants were screened for eligibility and provided verbal consent, they were scheduled for their in-person baseline data collection appointment (Time 1). Prior to their appointment, participants were sent an electronic survey via RedCap (Vanderbilt, TN) that included demographic and cancer history questionnaires and self-report instruments (described below). Informed written consent was completed and electronic survey completion verified when in-person. This was followed by standardized cognitive testing. After Time 1 data collection was complete, participants were randomized to either the KK or ML groups in a 1:1 ratio 28 using randomization software 29 and block randomization to ensure equal distribution between groups 30. The PI informed participants of their group assignment and provided intervention details. Research staff collecting baseline data were blind to random group allocation. Participants began their daily intervention within two weeks of completing Time 1 data collection and were scheduled for Time 2 data collection after eight weeks of the daily program. Time 2 data collection included the same measures as baseline except demographic and cancer history questionnaires. All data were stored in RedCap.

2.3. Interventions Protocols

The primary intervention for this study was KK, and the attention control condition was ML. Both intervention protocols were adapted from earlier studies using the same inventions with older adults with cognitive decline 18,23–26. Specific adaptations to the study design and our rationales for the intervention are described in Electronic Supplementary Materials Table 1. All participants were instructed to meditate or listen to music (depending on group allocation) while sitting comfortably, eyes closed, for 12 minutes a day, every day, for eight weeks and to record each practice session daily on their practice log. The facilitators contacted each participant with weekly reminders and were available to answer questions as needed during the study.

2.3.1. KK Meditation.

The KK program incorporated chanting (singing repetition of the “Sa-Ta-Na-Ma” mantra) with mudras (touching each fingertip to the thumb from index to little finger in sequence with the chant) and visualization (imagining the sound energy coming through the top of the head and out between the eyebrows in an “L” shape). Participants assigned to this group were provided a simple video demonstration of the 12-min daily meditation and four guided audio meditations—two with nature sounds (one with words and one with only timing cues [bell sound]), and two with calming instrumentals (one with words and one with only timing cues [bell sound]) via a private playlist on a consumer-based audio platform. All audiovisual materials were prepared and created by the group facilitator, a master’s prepared licensed social worker, certified kundalini yoga teacher, and a Certified Yoga Therapist. Written instructions for how to complete the daily KK were also provided. After participants were given their protocol details, the group facilitator contacted each participant to review the meditation technique and discuss any questions or barriers to their practice. Written instructions were adapted from those publicly available on the Alzheimer’s Foundation Research website (https://alzheimersprevention.org/research/kirtan-kriya-yogaexercise/). Both the video link and the written instructions can be found in the Electronic Supplementary Materials.

2.3.2. Music Listening.

Participants in the ML group were given written instructions for completing their daily 12-min practice and access to four audio files containing 12-min clips of classical music (i.e. Mozart, Bach, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky) on a private playlist located on the same consumer-based audio platform that was used for the KK group.

2.4. Study Outcomes

There were no changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced.

2.4.1. Feasibility Outcomes.

The number of potential participants screened and enrolled and the number of participants completing all data collection time points were tracked to evaluate recruitment and retention rates for the study. Participant adherence to the programs was determined based on their practice logs and the “comments” section on their daily logs. Exit interviews were conducted after Time 2 to evaluate usability, usefulness, and satisfaction and included both structured and open-ended questions about participants’ perceptions of the structure, content, value, and potential burden of the intervention programs.

2.4.2. Cognitive Function (Primary Outcomes).

Cognitive performance was measured with three standardized neuropsychological tests recommended by the International Cancer and Cognition Task Force (ICCTF) for evaluating CRCI 31: the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised 32, a measure of immediate and delayed verbal memory, the Controlled Oral Word Association Test 33, a measure of verbal fluency, and Trail Making Test A & B 34, measures of processing speed and executive attention. Tests were administered according to standardized protocols described in the proprietary test manuals, and scored by two different trained research staff. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function Instrument version 3 (FACT-Cog), Perceived Cognitive Impairments (PCI) and the FACT-Cog Quality of Life (QOL) subscales were used to measure quality of life 35 and demonstrated high reliability (present study Cronbach’s α’s: 0.97 and 0.95). Lower scores indicate poorer functioning and quality of life.

2.4.3. Psychosocial Symptoms, Self-Efficacy (Secondary Outcomes).

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 36,36 Short Form 8a scales 36 were used to measure anxiety and depressive symptoms using the — Emotional Distress – Anxiety, and Emotional Distress – Depression, and the Fatigue was used to measure feelings of fatigue 37. Stress was measured using the Perceived Stress Scale 28,28, a 10-item scale measuring the degree that life circumstances are appraised as having been stressful in the previous 4 weeks 38. These measures all demonstrated adequate reliability in this study (Cronbach’s α’s: 0.93–0.97). Higher scores indicate greater symptoms for all measures. In order to capture the effect of the intervention on feelings of self-efficacy in managing cognitive symptoms, we administered the Chronic Disease Self Efficacy Scale (CDSES; Cronbach’s α: 0.87 in present study)39, a 6 item scale that is widely used as a measure of general self-efficacy, adapting items to reflect the chronicity of CRCI.

2.5. Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample by group assignment. We used mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate changes in primary and secondary outcomes from time 1 to time 2 along with group by time effects. Preliminary analysis for tests of assumptions included normality, independence of errors, homogeneity of variance, and outliers. Per CONSORT guidelines, we utilized intention to treat principles to handle missing data due to attrition for hypothesis testing. Raw scores were used in analyses and the last observation carried forward method 40 was used for mixed ANOVA analyses. The alpha level was kept at 0.05 for each analysis and not corrected for family wise error in this exploratory feasibility study. All statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS Version 26 28. Exit interviews were audio recorded and AH and HB listened to all interviews, took notes, and identified themes related to usability, usefulness, satisfaction, and burden across all participants.

3.0. Results

We found no significant group differences in demographic and clinical characteristics. See Table 1 for all baseline data of demographics and clinical characteristics for the KK and ML groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical measures

| Music listening (n=15) | Kirtan Kriya (n=16) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Mean (SD) | Min, max | Number (%) | Mean (SD) | Min, max | P valuea | |

| Age in years | 48.93 (10.69) | 27, 73 | 50 (9.52) | 32, 64 | 0.77 | ||

| Education in years | 15.93 (1.44) | 13, 18 | 15.5 (2.39) | 12, 21 | 0.55 | ||

| Minority (1=yes, 0=no) | 5 (33.3%) | 1 (6.3%) | 0.20 | ||||

| Partnered (1=yes, 0=no) | 12 (80%) | 12 (75%) | 0.58 | ||||

| Have children (1=yes, 0=no) | 12 (80%) | 8 (50%) | 0.08 | ||||

| Bachelors or higher | 13 (86.67%) | 9 (56.25%) | 0.21 | ||||

| Full time work or homemaker or student / part time work | 11 (73.33%) / 4 (26.66%) | 14 (87.5%) / 1 (6.3%) | 0.44 | ||||

| Breast cancer stage I/II/III | 4(26.7%) /7 (46.7%)/ 4 (26.7%) | 4(25%)/8(50%)/4 (25%) | 0.98 | ||||

| Time since diagnosis (in months) | 33 (18.71) | 7.97, 69.7 | 37.07 (20.79) | 8.57, 77.83 | 0.57 | ||

| Time since chemotherapy (in months) | 27.58 (18.85) | 3.27, 64.1 | 34.96 (19.85) | 4.37, 73.17 | 0.30 | ||

| Anthracycline chemotherapy | 7 (46.7%) | 5 (31.3%) | 0.38 | ||||

| IDC, ILC, combination with DCIS | 15 (100%) | 13 (81.25%) | 0.38 | ||||

| Estrogen receptor positive | 9 (60%) | 13 (81.3%) | 0.19 | ||||

| Progesterone receptor positive | 5 (33.3%) | 7 (43.8%) | 0.55 | ||||

| HER-2 positive | 6 (40%) | 7 (43.8%) | 0.83 | ||||

| Herceptin treatment | 6 (40%) | 7 (43.8%) | 0.83 | ||||

| Triple negative | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0.16 | ||||

| Surgery | 15 (100%) | 16 (100%) | 0.72 | ||||

| Radiation | 13 (86.7%) | 13 (81.3%) | 0.68 | ||||

| Estrogen blockade treatment | 8 (53.3%) | 12 (75%) | .21 | ||||

| Neoadjuvant | 9 (60%) | 10 (62.5%) | 0.88 | ||||

| Menopause | 12 (80%) | 11 (68.75%) | 0.24 | ||||

| Currently on estrogen blockade treatment | 10 (66.7%) | 11 (68.75%) | 0.58 | ||||

Abbreviations. DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ; IDC: invasive ductal carcinoma; ILC: invasive lobular carcinoma; HER-2: human epithelial receptor 2; max: maximum; min: minimum; SD: standard deviation

Independent t tests used to evaluate differences in continuous variables and chi square tests used to evaluate differences in categorical variables.

3.1. Feasibility Data: Intervention Acceptability, Utility, and Satisfaction

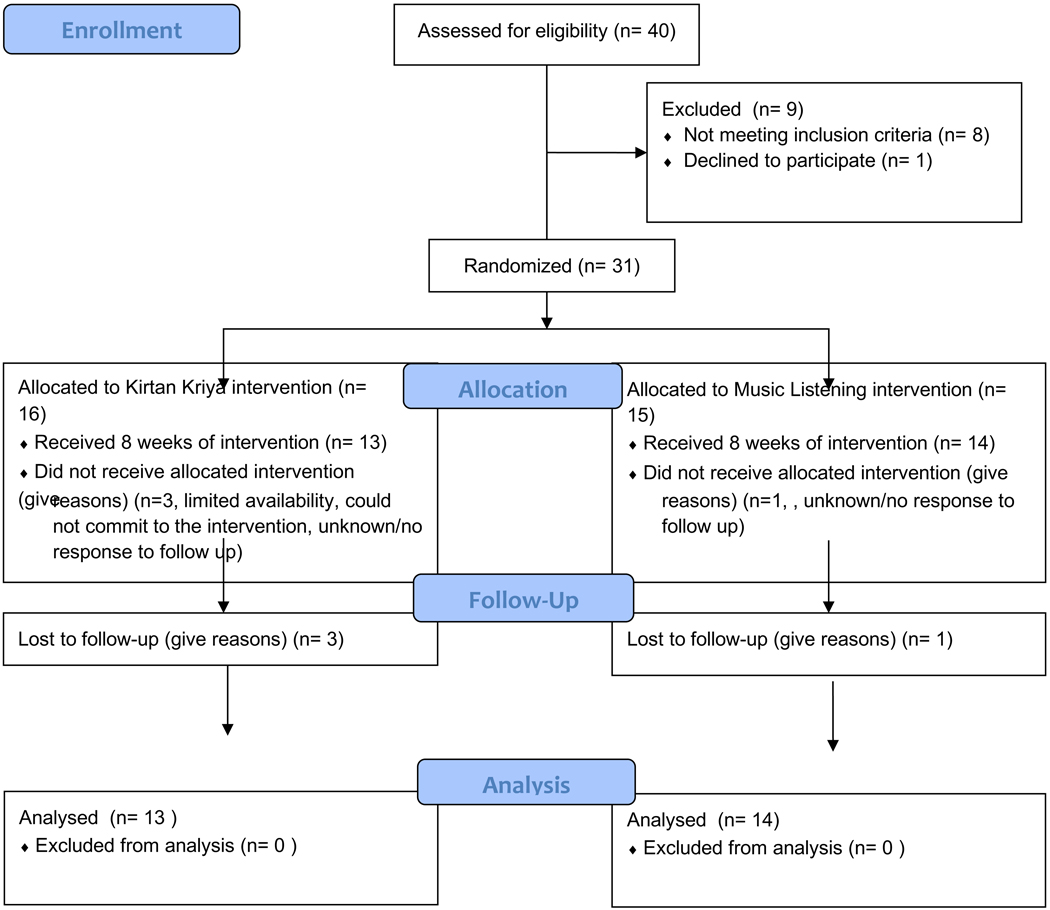

Forty people expressed interest in the study between October 2018 and July 2019. Thirty-one women were eligible for the study and enrolled. Of those that did not enroll, 8 did not meet inclusion criteria and one declined to enroll based on study requirements. See Figure 1. Consort Flow Diagram for enrollment, randomization, intervention recipients, and numbers analyzed for the primary outcomes. All participants received the intervention program to which they were allocated. In the KK group, 100% completed Time 1 data collection, 80% completed Time 2 data collection. In the ML group, 100% completed Time 1 data collection, 93.7% completed Time 2 data collection. Those that did not complete Time 2 data collection had withdrawn from the study for both groups. Overall, retention in both interventions was high (87%). For adherence, the KK group completed on average 45 of the 54 sessions (80.35%) and the ML group on average completed 50 of the 54 sessions (93.75%). There were no statistically significant group differences in retention rates or average minutes of the interventions (p > 0.10). No adverse events were reported by any of the participants.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram for study enrollment, allocation, follow up, and analysis.

Exit interviews were conducted with 13 of the 16 participants in the KK group. Approximately half of the women believed the intervention had helped them a little, others did not perceive any direct effects. Those who did find it helpful spoke about the benefits of meditation and relaxation. A few also cited specific activities that were now easier, such as focusing, being less dependent on navigation devices, remembering, or calming down—or waking up more alert. About half the women found it difficult to stick with the KK intervention for the full 8 weeks. Some described the exercise as boring, or monotonous, and one stated that it “never flowed for me.” Two stated that doing the same meditation each day did get easier over time, whereas for others, boredom with the meditation either remained consistent or increased over time. Some women found meditation easier to do at night, although others found that they fell asleep if they tried to do the meditation at nighttime. Most indicated that having the facilitator check in with them throughout the 8 weeks was helpful, especially in the beginning. Women did, however, appreciate the flexibility of the daily sessions as something they could choose to do when most convenient.

Since this was a feasibility study, we also conducted exit interviews with the attention control group. 15 of the 16 participants from the ML group completed exit interviews. Almost all of the participants reported that the music program was beneficial to their lives and expressed high satisfaction and enjoyment from incorporating it into their daily routines. Some specific effects that participants noted from doing the music program included better word recall, focusing, concentrating for longer periods of time, remembering where they put something, approaching prioritizing and problem solving in a clearer way, multitasking, following through on thoughts better, not drawing blanks, and being calmer, with less anxiety and stress. Only two of the 13 did not perceive any cognitive benefit from the program.

3.2. Feasibility Data: Study Demands

For both the KK and ML groups, the overall schedule (i.e., three campus visits) were attainable for almost all participants (n=26). Some participants cited the helpfulness and flexibility of staff in scheduling these trips. Overall women expressed low study burden—they did not consider the data collection or cognitive testing problematic or burdensome, although a few expressed that they considered the questionnaires lengthy.

3.3. Feasibility Data: Suggestions for Improvement

Participants across both groups suggested more variety in tracks (meditation or music) to listen to. It was also suggested that the surveys be shortened. A few participants suggested a mandatory longer intervention time (16 instead of 8 weeks). Eleven participants thought that a single smartphone app on their phone with audio tracks, questionnaires, study log, and reminders all in one place would make the intervention easier to complete and were enthusiastic about that prospect. One participant wanted more feedback on how she did on the surveys and cognitive tests after she completed them. Finally, one woman cautioned the researchers not to make the intervention too long in the future and added, “I can make 12 minutes happen.”

3.3. Change in Primary and Secondary Outcomes Across Time Analyses

The means and standard deviations, F statistics, and partial eta squared (ηp2) values for the primary and secondary outcomes of the KK (n=16) and ML (n=15) groups are provided in Table 2. The findings indicated that both the KK and ML group reported significant change over time for FACT-Cog PCI (F (1,29) = 11.74, p < 0.01), FACT-Cog QOL (F (1,29) = 14.65, p < 0.01), HVLT-I (F (1,29) = 8.16, p < 0.01), and COWA (F (1,29) = 13.581, p < 0.01) scores. Trails A scores also changed over time, with the time effect approaching significance (F (1,29) = 3.728, p = 0.063). The group by time effects for all the cognitive outcomes were not significant (p’s > 0.05).

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations, F statistics and ηp2 for mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) for primary and secondary outcome measures

| Music listening group (n=15) | Kirtan Kriya group (n=16) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Time 1 mean (SD) | Time 2 mean (SD) | Time 1 mean (SD) | Time 2 mean (SD) | F statistic time effect | ηp2 for time effect | F statistic time * group effect | ηp2 for time * group effect |

| FACT-Cog PCIa | 36.33 (20.10) | 44.87 (21.28) | 46.88 (17.27) | 54.31 (19.09) | 11.74** | 0.288 | 0.055 | 0.002 |

| FACT-Cog QOLa | 8.67 (5.64) | 10.67 (4.89) | 10.56 (4.41) | 12.63 (4.11) | 14.65** | 0.339 | 0.003 | 0.00 |

| PSSb | 15.47 (8.43) | 12.73 (9.11) | 13.06 (7.25) | 14.26 (5.79) | 0.805 | 0.028 | 5.30* | 0.159 |

| PROMIS Anxietyb | 20.4 (8.10) | 17.93 (8.37) | 15.69 (8.47) | 16.69 (7.12) | 0.526 | 0.018 | 2.94 | 0.092 |

| PROMIS Depressionb | 13.07 (4.27) | 11.80 (4.02) | 12.75 (6.82) | 12.81 (5.60) | 0.768 | 0.026 | 0.936 | .031 |

| PROMIS Fatigueb | 25.47 (7.85) | 23.73 (8.25) | 23.00 (7.16) | 22.13 (7.45) | 2.212 | 0.071 | 0.239 | 0.008 |

| CDSESa | 72.31 (17.22) | 78.86 (16.07) | 74.42 (21.06) | 74.22 (20.93) | 2.327 | 0.074 | 2.626 | 0.083 |

| HVLT Immediatea | 29.73 (2.60) | 30.93 (3.30) | 29.19 (2.71) | 31.69 (2.52) | 8.166** | 0.22 | 1.008 | 0.034 |

| HVLT Delayeda | 11.33 (1.17) | 11.20 (1.08) | 11.25 (1.06) | 11.56 (.51) | 0.286 | 0.01 | 1.77 | 0.058 |

| COWAa | 40.00 (9.50) | 42.60 (9.13) | 37.13 (8.50) | 41.06 (9.44) | 13.581** | 0.319 | 0.568 | 0.019 |

| Trails Ab | 26.40 (11.48) | 23.13 (6.50) | 26.44 (6.78) | 24.06 (6.40) | 3.728 | 0.114 | 0.093 | 0.003 |

| Trails Bb | 52.53 (21.89) | 51.06 (19.39) | 59.31 (19.19) | 56.31 (17.86) | 0.68 | 0.023 | 0.080 | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: CDSES: Chronic Disease Self Efficacy Scale; COWA: Controlled Oral Word Association Test; FACT-Cog: Functional

Assessment of Cancer Treatment Cognitive Symptoms; HVLT: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test; PCI: Perceived Cognitive Impairments, PROMIS:

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; SD: standard deviation; Trails: Trail Making Test; QOL: Quality of Life

: Higher scores indicate better performance/functioning.

: Lower scores indicate less symptoms

p<0.05

p<0.01

Note: The Levene’s Test of Equality of Error Variances was not violated for any of the mixed ANOVA analyses

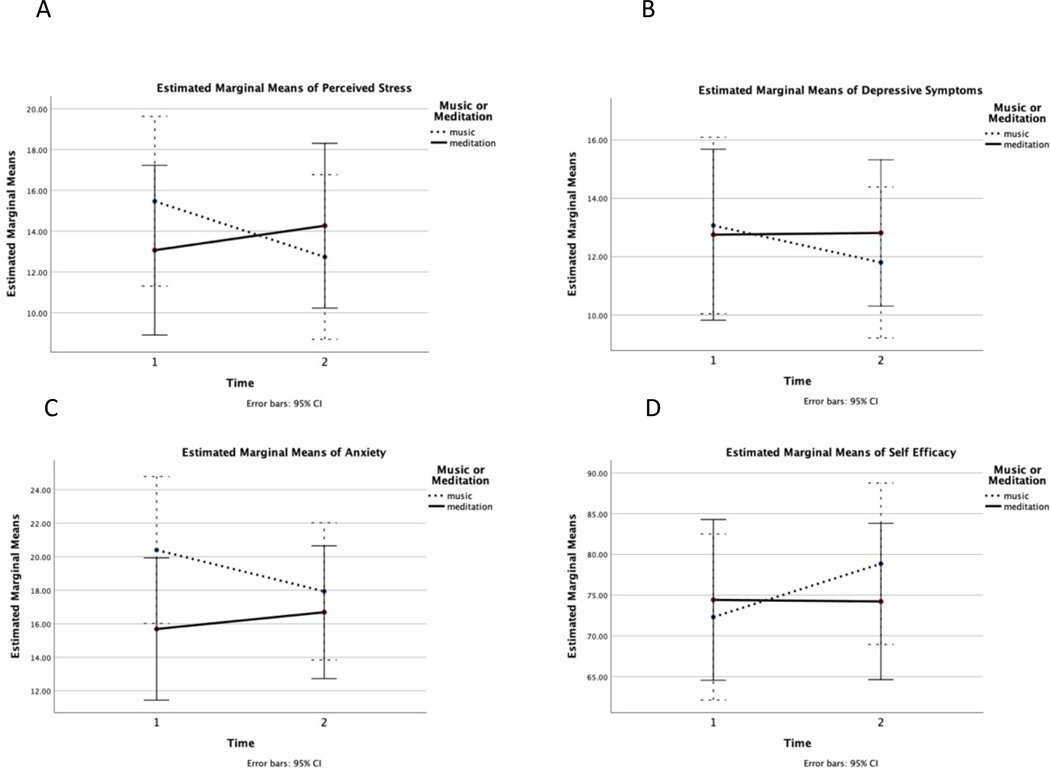

No significant time effects were found for the PSS, PROMIS Anxiety, PROMIS Depression, PROMIS Fatigue, CDSES, HVLT-Delayed, or Trails B (p’s > 0.05). There was a group by time effect found for PSS (F (1,29) = 5.30, p < 0.05), and trends towards group by time effects found for PROMIS Depression and CDSES. Post hoc paired t-test analyses were conducted to examine the significant group by time effects found for PSS. These analyses revealed that the ML group had a significant decrease in PSS from time 1 to time 2 (t=2.20, p < 0.05), and that the increase in PSS seen in the KK group was not significant (p > 0.05, see Figure 2.A. for the estimated marginal mean plot). Even though the group by time effects were non-significant for PROMIS Depression, PROMIS Anxiety or CDSES, we did examine the estimated marginal mean plots for these analyses and similar patterns of improvements in these measures were seen in the ML group but not the KK group (See Figure 2.B–D). Post hoc paired t-test analyses for PROMIS Depression, PROMIS Anxiety of CDSES revealed that these changes were only significant for the ML group’s improvement in CDSES (t= −2.19, p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Estimated marginal mean plots for the KK meditation (n=16) and the ML (n=15) groups for time 1 and time 2 for A) Perceived stress measured by the Perceived Stress Scale, B) Depressive symptoms measured by the PROMIS Emotional Distress – Depression Scale, C) Anxiety measured by the PROMIS Emotional Distress – Anxiety Scale, and D) Self efficacy in managing cognitive symptoms measured by the Chronic Disease Self Efficacy Scale. Lower scores represent lower symptoms for A-C, and higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy for D.

4.0. Discussion

This small exploratory study used a randomized parallel design and demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of recruiting and delivering a home-based, daily meditation intervention aimed to improve cognitive functioning and reducing symptom burden of BCS. We also demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of delivering a home-based music listening intervention (the attention control condition) to BCS. To our knowledge, this is the first study to utilize KK or ML in BCS with cognitive symptoms. On average participants adhered to almost all of the protocol. About half of those in the KK group and almost all of the ML group expressed that the programs had a beneficial effect on their cognitive symptoms along with their overall well-being. This study also provides preliminary evidence that both KK and ML and may have beneficial effects on perceived cognitive impairment and improve cognitive performance, and ML may be beneficial for stress and self-efficacy in BCS who report cognitive symptoms.

The KK intervention program was well received in terms of study demands, with participants noting positive effects on relaxation and some effects on cognitive symptoms similar to previous findings 18. However, many participants in this group expressed some resistance to doing the same meditation each day and explained that variety in meditations would motivate them to maintain daily meditation in their lives. This boredom and resistance to meditation practice is novel in this sample compared to the previously published reports of using the same KK protocol in other populations 17,18,24,41. This difference in satisfaction may be a result of the previous authors 23–25,42 either not collecting or not reporting qualitative data from exit interviews. Innes et al. (2016)18 did have an exit questionnaire with open ended questions and reported that over 80% of the 51 participants who completed the questionnaire indicated they would “likely” continue the program after the study. However, qualitative analysis of open-ended narrative text was not reported on in this study. The difference in satisfaction that we found may also be attributed to our sample being younger and a different clinical populations—the mean age of participants in previous studies 23–25,42 were approximately 10–20 years older than the women in the current study. This age difference could reflect a social desirability response bias which is more common in older adults43.

It is also possible that participants in our study were doing the KK meditation “incorrectly” resulting in boredom or dissatisfaction. In an effort to increase access of this intervention program through remote delivery, we chose not to physically observe participants in the KK group. Our group facilitator did; however, speak with each participant in the KK group to ensure that they understood the meditation when starting the protocol. This decision was also made in an effort to not introduce a bias that the participants could potentially “do it wrong”. Over the past 20 years, meditation and mindfulness have been increasingly promoted in the media. In 2017, over 46 million U.S citizens reported utilizing meditation in some form.44 With this increase in knowledge of meditation, people may have expectations about how they are “supposed to” perform a meditation, and think that they are doing it wrong. Some of the comments recorded by the KK group facilitator supported this theory. It is also possible that meditation was perceived to be more challenging than listening to music since it is more activating and requires more intention and attention—an agency that one is “doing something” active, as opposed to a more passive form of relaxation. Although uncommon, it is possible that meditation can amplify or call to attention negative thoughts or emotions.45 This may explain some of the resistance to meditation among many of the participants, but it would need to be empirically evaluated.

Both groups in this study demonstrated improvements in perceived cognitive outcomes, which is consistent with those reported previously in 53 persons with subjective cognitive decline 46. Notably, the improvements we found in perceived cognitive impairments (approximately 8 points in both groups), were higher than published “clinically meaningful changes” in the FACT-Cog PCI subscale of approximately 4.6 points in BCS post adjuvant treatment 47. The effect sizes for changes in perceived cognitive impairments and quality of life did not differ significantly between the groups.

The participants in both the KK and ML groups demonstrated significant improvements on two of the cognitive tests, however, the changes observed were not significantly different between the groups. Positive changes in cognitive test scores are consistent with previous reports of KK used in persons with memory problems 23 and older adults 25. It is possible that the positive changes we found in cognitive test scores were due to practice effects 48, however we administered alternate forms of the HVLT and COWA at each time to reduce familiarity with the specific forms of the tests that had been administered at T1. Benedict and Zgaljardic (1998)49 reported that practice effects were significantly reduced when alternative forms of the HVLT were used, however some have suggested that practice effects are not as reduced when alternative forms of the COWA are used50.

The ML group demonstrated improvements in perceived stress and feelings of self-efficacy at managing their cancer related symptoms. The ML group also reported lower levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and fatigue at Time 2 compared to Time 1, but those differences were not statistically significant. The KK group did not demonstrate any significant improvements in their psychological symptoms or in their feelings of self-efficacy. These findings differ from previous findings of greater improvements in mood related outcomes in the KK group compared to the ML group in older adults with subjective cognitive decline 26. Our findings may be explained by the shorter length of time, and therefore smaller “dosage” of our intervention protocol (eight weeks compared to their 12 weeks 26). Our findings could also be due to differences in the populations studied. Many participants in the KK group expressed some resistance to doing the same meditation each day and explained that variety in meditations would motivate them to maintain daily meditation in their lives during exit interviews. Future studies should consider using variations of different mantra-based meditations to encourage intervention engagement. It is possible that the KK group may have had greater improvements in psychological outcomes with a greater intervention dose or greater variety in meditation content.

Both KK and ML involved sitting quietly and focusing on one thing (either music or guided meditation) each day, which may have resulted in consistent decreases in neural activity over the eight weeks. This decrease in activation may have had beneficial neural effects, consistent with reports suggesting periods of decreased neural activity may regulate human longevity 51. Similarly, there is growing evidence that meditation may improve neurophysiological pathways in populations at risk for cognitive decline 52. Research utilizing brain imaging suggests improvements in blood flow to the brain 23,24 in persons with subjective cognitive decline 18,23–25 and language connectivity in persons with mild cognitive impairment receiving MM compared to memory enhancement training 41,53.

Although unexpected, our findings indicate that ML had high satisfaction and acceptability among BCS. Music inherently represents cognitive stimuli desired for neuroplasticity such as repetition and attention.54 Processing of musical sounds has been associated with changes in brain structure and function suggestive of neuroplasticity,55–57 making music a potentially rehabilitative tool to restore cognitive function, whether through passive listening to or active playing of music.58 Many studies have shown that listening to music can improve cognitive and motor skills and recovery following brain injury.59 Studies have also shown that listening to music can have positive effects on psychological symptoms that interact with cognitive abilities such as stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and mood. However, it is unclear how much or what kinds of musical stimuli elicit positive cognitive and psychological responses, and more research is needed in clinical populations to understand music’s effects on cognitive functioning.

Our findings need to be interpreted within the context of the study limitations. The sample size was small secondary to primary study aim—to determine feasibility and acceptability. We used convenience sampling which may represent selection bias. Our findings can only be generalized to female breast cancer survivors who received chemotherapy as part of their treatment. We are lacking a control group since we utilized an attention control condition controlling for the effects of time, attention, and relaxation in the primary intervention group. Future studies should include a waitlist control group to evaluate the possibility that the effects in this study were due to time, attention, relaxation, or practice rather than the particular stimuli received (MM or KK). We relied on self-reports of daily intervention completion and fidelity, which could have resulted in inaccurate measurement of treatment exposure due to human error or recall bias or lower fidelity to the intervention protocols than was reported by participants. Future studies should utilize alternative intervention content delivery methods that allow for backend tracking of audio track utilization. We used the cognitive tests recommended by the ICCTF for measuring change in CRCI 31, but it is possible that these measures were not sensitive or specific enough 60 to capture the change in cognitive function reflected by the self-reports in our findings. We also utilized intention to treat analysis per CONSORT guidelines, but this conservative estimate of treatment effect can increase potential for type II error 40. On the other hand, in this exploratory study we did not correct for family wise error, so there is also the potential for Type I error.

5.0. Conclusion

Identifying feasible, cost-effective interventions for improving cognitive symptoms in BCS is very important, given the high prevalence (up to 60%6) and negative impact of these symptoms on social role and occupational performance. Cognitive impairment and psychological distress are serious concerns for many BCS following treatment completion and need to be addressed by health care providers. Profiles of CRCI are unique to the individual and do not always improve in the months and years following completion of adjuvant treatment. There are limited options for survivors to manage their cognitive symptoms. Our study builds on previous research that has demonstrated positive effects of behavioral interventions on cognitive functioning 13,61,62 and extends our knowledge of the effects of Kirtan Kriya meditation and classical music listening interventions at improving cognitive and psychological symptoms. Both the primary intervention (Kirtan Kriya meditation) and attention control condition (classical music listening) evaluated in this study were delivered remotely, easy to learn, low cost, required minimal instructions, and were easily incorporated into participants’ busy schedules (requiring just 12 minutes per day). Furthermore, both programs could be adapted for telehealth delivery, making them accessible to an even larger population. Although the findings are positive, a larger 3-arm randomized control trial aimed to determine the efficacy of the interventions compared to usual care is needed.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

It was feasible to remotely delivery 8-week, 12 min/day meditation or music interventions to breast cancer survivors

Kirtan Kriya meditation may improve verbal fluency and memory, perceived cognitive functioning, and quality of life

Music Listening may improve verbal fluency and memory, perceived cognitive functioning, quality of life, and perceived stress

Acknowledgments:

This study was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30NR015335. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research is also supported by the St. David’s Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research. The research team would like to thank both the Breast Cancer Resource Center (Austin, TX) and Texas Oncology for their support and assistance recruiting participants for this study.

Footnotes

Clinical Trials Registration number: NCT03696056

Declaration of Interest Statement: EK serves as an advisory board member for Pfiser. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. This study was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30NR015335.

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, AH, upon reasonable request.

Research involving Human Participants and/or Animals: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (University of Texas at Austin Institutional Review Board, 2018–05-0155) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

The study details can be accessed at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03696056

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Meyers CA. Cognitive complaints after breast cancer treatments: patient report and objective evidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(11):761–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, D.C. : National Academies Press;2005.

- 3.Von Ah D. Cognitive changes associated with cancer and cancer treatment: state of the science. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(1):47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahles TA, Root JC, Ryan EL. Cancer- and cancer treatment-associated cognitive change: an update on the state of the science. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(30):3675–3686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pomykala KL, Ganz PA, Bower JE, et al. The association between pro-inflammatory cytokines, regional cerebral metabolism, and cognitive complaints following adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Brain Imaging Behav. 2013;7(4):511–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kesler S, Rao A, Blayney DW, Oakley Girvan I, Karuturi M, Palesh O. Predicting long-term cognitive outcome following breast cancer with pre-treatment resting state fMRI and random forest machine learning. Front Human Neurosci. 2017;11:555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arndt J, Das E, Schagen SB, Reid-Arndt SA, Cameron LD, Ahles TA. Broadening the cancer and cognition landscape: the role of self-regulatory challenges. Psychooncology. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bray VJ, Dhillon HM, Vardy JL. Systematic review of self-reported cognitive function in cancer patients following chemotherapy treatment. J Cancer Surviv. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pullens MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA. Subjective cognitive dysfunction in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2010;19(11):1127–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid-Arndt SA, Cox CR. Stress, coping and cognitive deficits in women after surgery for breast cancer. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19(2):127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henneghan A, Stuifbergen A, Becker H, Kesler S, King E. Modifiable correlates of perceived cognitive function in breast cancer survivors up to 10 years after chemotherapy completion. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bower JE, Lamkin DM. Inflammation and cancer-related fatigue: mechanisms, contributing factors, and treatment implications. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30 Suppl:S48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treanor CJ, McMenamin UC, O’Neill RF, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for cognitive impairment due to systemic cancer treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016(8):CD011325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crouch A, Von Ah D, Storey S. Addressing Cognitive Impairment After Breast Cancer: What Do Women Want? Clin Nurse Spec. 2017;31(2):82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson LE, Zelinski EL, Speca M, et al. Protocol for the MATCH study (Mindfulness and Tai Chi for cancer health): A preference-based multi-site randomized comparative effectiveness trial (CET) of Mindfulness-Based Cancer Recovery (MBCR) vs. Tai Chi/Qigong (TCQ) for cancer survivors. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;59:64–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Q, Zhao H, Zheng Y. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on symptom variables and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(3):771–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eyre HA, Acevedo B, Yang H, et al. Changes in Neural Connectivity and Memory Following a Yoga Intervention for Older Adults: A Pilot Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52(2):673–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Innes KE, Selfe TK, Khalsa DS, Kandati S. A randomized controlled trial of two simple mind-body programs, Kirtan Kriya meditation and music listening, for adults with subjective cognitive decline: Feasibility and acceptability. Complement Ther Med. 2016;26:98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Paterson CL, et al. Examination of Broad Symptom Improvement Resulting From Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2827–2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milbury K, Chaoul A, Biegler K, et al. Tibetan sound meditation for cognitive dysfunction: results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. Psychooncology. 2013;22(10):2354–2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deprez S Impact of a mindfulness-based intervention on chemotherapyinduced cognitive dysfunction and brain alterations: A pilot study. 2018 International Cognition and Cancer Task Force Conference; April 10, 2018, 2018; Sydney Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khalsa DS. Stress, Meditation, and Alzheimer’s Disease Prevention: Where The Evidence Stands. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newberg AB, Wintering N, Khalsa DS, Roggenkamp H, Waldman MR. Meditation effects on cognitive function and cerebral blood flow in subjects with memory loss: a preliminary study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(2):517–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moss AS, Wintering N, Roggenkamp H, et al. Effects of an 8-week meditation program on mood and anxiety in patients with memory loss. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(1):48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lavretsky H, Epel ES, Siddarth P, et al. A pilot study of yogic meditation for family dementia caregivers with depressive symptoms: effects on mental health, cognition, and telomerase activity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(1):57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Innes KE, Selfe TK, Khalsa DS, Kandati S. Effects of Meditation versus Music Listening on Perceived Stress, Mood, Sleep, and Quality of Life in Adults with Early Memory Loss: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52(4):1277–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan MJEK, & Dehoux E. A survey of multiple sclerosis: Perceived cognitive problems and compensatory strategy use. Canadian Journal Of Rehabilitation. 1990;4(3):99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 28.PASW [computer program]. Version 18.0. Chicago, IL USA2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Team R. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio, PBC; http://www.rstudio.com/. Published 2020. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vickers AJ. How to randomize. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006;4(4):194–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wefel JS, Vardy J, Ahles T, Schagen SB. International Cognition and Cancer Task Force recommendations to harmonise studies of cognitive function in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(7):703–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benedict RHB, Schretlen D, Groninger L, Brandt J. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised: Normative Data and Analysis of Inter-Form and Test-Retest Reliability. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1998;12(1):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benton A, deS Hamsher K, Varney N, Spreen O. Contributions to neuropsychological assessment: A clinical manual. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tombaugh T. Trail Making Test A and B: Normative data stratified by age and education. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2004;19(2):203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner L, Sweet J, Butt Z, Lai J-s, Cella D. Measuring patient self-reported cognitive function: development of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-cognitive function instrument. J Support Oncol. 2009;7(6):W32–W39. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 2017. http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/obtainadminister-measures. Published 2017. Accessed.

- 38.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: A review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(3):109–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eyre HA, Siddarth P, Acevedo B, et al. A randomized controlled trial of Kundalini yoga in mild cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(4):557–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Innes KE, Selfe TK, Brown CJ, Rose KM, Thompson-Heisterman A. The effects of meditation on perceived stress and related indices of psychological status and sympathetic activation in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers: a pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:927509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soubelet A, Salthouse TA. Influence of Social Desirability on Age Differences in Self-Reports of Mood and Personality. Journal of Personality. 2011;79(4):741–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Macinko J, Upchurch DM. Factors Associated with the Use of Meditation, U.S. Adults 2017. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(9):920–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farias M, Wikholm C. Has the science of mindfulness lost its mind? BJPsych Bulletin. 2016;40(6):329–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Innes KE, Selfe TK, Khalsa DS, Kandati S. Meditation and Music Improve Memory and Cognitive Function in Adults with Subjective Cognitive Decline: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56(3):899–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bell ML, Dhillon HM, Bray VJ, Vardy JL. Important differences and meaningful changes for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function (FACT-Cog). Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2018;2(1):48. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andreotti C, Root JC, Schagen SB, et al. Reliable change in neuropsychological assessment of breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2016;25(1):43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benedict RHB, Zgaljardic DJ. Practice Effects During Repeated Administrations of Memory Tests With and Without Alternate Forms. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1998;20(3):339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ross TP. The reliability of cluster and switch scores for the Controlled Oral Word Association Test. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2003;18(2):153–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zullo JM, Drake D, Aron L, et al. Regulation of lifespan by neural excitation and REST. Nature. 2019;574(7778):359–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Innes KE, Selfe TK. Meditation as a therapeutic intervention for adults at risk for Alzheimer’s disease - potential benefits and underlying mechanisms. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Black DS, Cole SW, Irwin MR, et al. Yogic meditation reverses NF-kappaB and IRF-related transcriptome dynamics in leukocytes of family dementia caregivers in a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(3):348–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sohlberg MM, Mateer CA. Effectiveness of an attention-training program. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1987;9(2):117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drake C, Jones MR, Baruch C. The development of rhythmic attending in auditory sequences: attunement, referent period, focal attending. Cognition. 2000;77(3):251–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peretz I, Zatorre RJ. Brain organization for music processing. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:89–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blood AJ, Zatorre RJ. Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(20):11818–11823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jauset-Berrocal JA, Soria-Urios G. [Cognitive neurorehabilitation: the foundations and applications of neurologic music therapy]. Rev Neurol. 2018;67(8):303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hegde S. Music-based cognitive remediation therapy for patients with traumatic brain injury. Front Neurol. 2014;5:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nelson WL, Suls J. New approaches to understand cognitive changes associated with chemotherapy for non-central nervous system tumors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(5):707–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fernandes HA, Richard NM, Edelstein K. Cognitive rehabilitation for cancer-related cognitive dysfunction: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(9):3253–3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cifu G, Power MC, Shomstein S, Arem H. Mindfulness-based interventions and cognitive function among breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.