Abstract

The 1500mg/day dietary sodium-restriction commonly recommended for patients with heart failure has recently been questioned. Poor adherence to sodium restricted diets makes assessing the efficacy of sodium restriction challenging. Therefore, successful behavioral interventions are needed. We reviewed sodium restriction trials and descriptive studies of sodium restriction to: 1) determine if sodium restriction was achieved in interventions among heart failure patients; and 2) characterize predictors of successful dietary sodium restriction. Among 638 identified studies, 10 intervention trials and 25 descriptive studies met inclusion criteria. We used content analysis to extract information about sodium restriction and behavioral determinants of sodium restriction. Dietary sodium was reduced in seven trials; none achieved 1500 mg/day (range=1938–4564mg/day). The interventions implemented in the interventional trials emphasized knowledge, skills, and self-regulation strategies, but few addressed the determinants correlated with successful sodium restriction in the descriptive studies (e.g., social/cultural norms, social support, taste preferences, food access, self-efficacy). Findings suggest incorporating determinants predictive of successful dietary sodium restriction may improve the success of interventional trials. Without effective interventions to deploy in trials, the safety and efficacy of sodium restriction remains unknown.

Keywords: Heart failure, behavioral nutrition, intervention design, sodium restricted diet, dietary management of heart failure, congestive heart failure, nutrition education, sodium restriction

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure, which affects approximately 26 million people worldwide,(1) represents the most common indication for a sodium restricted diet.(2, 3) This recommendation is based on a hypothesis that low cardiac output leads to activation of renin which increases sodium retention.(4) This renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system-activated sodium retention, coupled with excess dietary sodium, is theorized to result in fluid retention in heart failure patients.(5) This theory is supported by observational studies that associate sodium restricted diet with lower symptom burden,(6) hospitalization,(7) mortality,(7) and event-free survival.(8) Lapses in sodium restricted diet adherence have been associated with readmission and mortality.(9, 10) American Heart Association guidelines recommend a 1500 mg/day sodium restricted diet for patients with early stage heart failure.(5)

However, data indicating the efficacy of sodium restricted diets as treatment for heart failure is inconsistent(11) and has recently been called into question. Sodium restriction has been associated with hospital readmission(12, 13) and mortality(12) as well as a dysregulated neurohormonal profile among compensated congestive heart failure patients.(14) It remains unclear if these inconsistencies are due to poor dietary measurement, reverse causality, or a biological mechanism of sodium homeostasis.(12, 15, 16)

Adherence to sodium restricted diets is poor among heart failure patients.(7, 16) This calls into question whether the trials assessed to form the current guidelines and recommendations accurately reflect the influence of sodium intake and sodium restricted diets on heart failure outcomes. Dietary interventions that successfully achieve sodium restriction are necessary to assess the effectiveness of sodium restriction on heart failure-relevant outcomes.

Improved behavioral interventions for heart failure self-management, and specifically for sodium restriction, are needed(17) but the path forward is unclear. The quality of behavioral interventions can be improved by identifying and targeting determinants of behavior change. However, the determinants incorporated into dietary sodium restriction interventions have not been examined systematically. Determinants of behavior are organized in a number of frameworks, e.g., Integrated Behavior Model.(18) Frameworks (e.g., (19)) that specifically address food choice and dietary behavior change identify determinants that should be considered in behavioral nutrition interventions. These determinants are key to improving trials of sodium restriction’s effect on heart failure outcomes.

Reviews have examined self-management interventions that include sodium restricted diet: One systematic review found self-management interventions correlated with improved health behavior(17), another review indicated that self-care behaviors improved with education.(20) The European Society of Cardiology recommends tailored skills-based education with social support.(21) No systematic reviews have yet addressed sodium restricted diet interventions in heart failure patients.

In this review, we aimed to determine if sodium restriction has been achieved in interventions among heart failure patients and then characterize why it is or is not. We conducted a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and descriptive studies of sodium restricted diets to 1) assess efficacy of sodium restricted diet interventions tested in randomized controlled trials, 2) identify determinants of dietary sodium restriction targeted in the trialed sodium restricted diet interventions, and 3) identify determinants of dietary sodium restriction identified in descriptive studies of sodium restriction. Then, we compared determinants targeted in randomized controlled trials with those identified in descriptive studies.

METHODS

First, we searched PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane databases for English-language studies published January 2000-December 2018 with the following terms: heart failure or congestive heart failure; dietary sodium restriction, salt restriction, salt limit, sodium limit, dietary salt, low-sodium, or low salt; and intervention, education, behavior, self-manage, self-care, knowledge, disease management, or secondary prevention. We included peer-reviewed randomized controlled trials of interventions for heart failure patients, with sodium restriction as a primary or secondary outcome, and quantitative and qualitative descriptive studies of adherence to sodium restricted diets. Eligible randomized controlled trials reported sodium restricted diet efficacy and behavioral determinants, whereas descriptive studies did not assess sodium restricted diet efficacy, instead focusing on determinants of sodium restricted diet adherence. Our search strategy is summarized in Figure 1. A review protocol was not pre-registered.

Figure 1.

Systematic search and review process

Next, we conducted a content analysis. Two reviewers coded each study for determinants of dietary behavior change, using the Integrated Behavior Model(18) and Contento framework(19) as a guide. Reviewers met regularly throughout the coding process, developing a comprehensive list of determinants represented in the included studies and resolving all differences by consensus.

Finally, we compared determinants addressed in the randomized controlled trial sodium restriction interventions and those identified in the descriptive studies.

RESULTS

Among 638 identified studies, 10 intervention trials and 25 descriptive studies met inclusion criteria.

Intervention studies

Ten randomized controlled trials that included sodium restricted diet were published in 2000–2018(22–31) and are summarized in Table 1. Studies were conducted in the US,(24, 26, 29–31) Canada,(23) Mexico,(25) Brazil,(22) Sweden,(28) and Japan(27) and ranged from 46 to 480 participants. Primary aims of these studies included: sodium reduction,(22, 26, 30) sodium restricted diet adherence,(23, 24) clinical status,(23, 27, 31) symptoms,(27) and self-care(29, 31); studies that did not include sodium reduction or sodium restricted diet adherence as primary aims included sodium reduction among secondary aims. Seven of these studies claimed to be effective in reducing sodium intake(23, 25, 26, 28, 30) or increasing sodium restricted diet adherence,(27, 31) based on 3-day food records (3DFR),(25, 26, 30) 24-hour urinary sodium excretion,(23, 25, 26, 28) or self-reported adherence.(27, 31) One study was inconclusive, finding self-reported reductions in sodium intake with 24-hour dietary recalls, but no reduction in urinary sodium excretion.(22) Two trials found no difference between intervention and control.(24, 29)

Table 1.

Description of sodium restriction randomized trials for heart failure patients

| Reference | Location | Sample Size | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome | Average sodium Intake in experimental group at post-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvez, 2012(22) | Brazil | n=46 | Outpatients at tertiary university hospital | 2 nutrition education sessions | usual care | Reduced self-reported, but not urinary Na intake. Urinary Na was 3-fold higher than self-report | 4564 mg/d (urinary sodium) |

| Arcand, 2005(23) | Toronto, Canada | n=47 | Ambulatory heart failure clinic patients | 2 g/day Na RX + 2 RD counseling sessions | 2 g/day Na RX | Reduced Na based on 3-day food record | 2140 mg/day |

| Athar, 2018(24) | USA | n=97 | general medicine inpatients in urban academic medical center | ultrasound image of inferior vena cava and explanation of relation to fluid status | ultrasound image with general heart failure information | No difference in self-reported sodium restriction adherence | Not measured |

| Colin-Ramirez, 2004(25) | Mexico City, Mexico | n=65 | heart failure clinic patients | sodium and fluid restriction diet RX | usual care | Decreased urinary Na excretion @ 6 mos. compared to control | 1942mg/day |

| Dunbar, 2013(26) | Atlanta, USA | n=61 | Patient/Family member dyads at outpatient heart failure clinic | family heart failure education or family partnership intervention | usual care | Lower urinary Na in family partnership group @ 8 months than usual care | 1938 mg/day measured through 3DFR |

| Otsu, 2012(27) | Japan | n=94 | Outpatients at cardiovascular clinic | self-monitoring and monthly educational sessions | usual care | Self-reported sodium reduction @ 12 months, not @ 24 months | Not measured |

| Philipson, 2013(28) | Sweden | n=97 | Patients with heart failure history from three hospitals | RD counseling session | general information about heart failure provided by RD | Significant reduction in urinary sodium compared to control group @ 12 weeks | Not calculated |

| Veroff, 2012(29) | USA | n=480 | Medicare Advantage patients with heart failure from large not-for-profit health plans | Mailed “Living with heart failure” DVD and booklet | mailed basic heart failure information | No significant change in sodium restriction | Not measured |

| Welsh, 2013(30) | Kentucky, USA | n=52 | heart failure patients recruited from cardiology clinic, community hospital, and university hospital | weekly home or phone counseling sessions | usual care | Lower Na intake in intervention group @ 6 months | 2262 mg/day |

| Young, 2016(31) | USA | n=100 | heart failure patients discharged from rural critical access hospital | inpatient self-management training + telephone sessions and toolkit | usual care | No significant difference in estimated daily sodium intake based on urine test | 3749 mg/day |

No interventions consistently achieved the 1500 mg/day recommended sodium intake level for adults with heart failure when sodium intake was estimated with 24-hour urinary sodium measurements (according to varying conversion assumptions). Average sodium intake at post-test ranged from 1938mg/day(26) to 4564mg/day(22).

Descriptive studies

Twenty-five studies describing determinants of sodium restricted diet adherence(32–56) were published in 2000–2018, summarized in Table 2. The included studies were conducted in the US(32–40, 42–47, 51, 52, 54, 56), the Netherlands,(48, 55) Taiwan,(41) China,(49) Canada,(50) Korea,(53) and Australia(46) and used qualitative,(33, 40–42, 49, 52, 55) quantitative(32, 34–37, 39, 44–48, 50, 51, 53, 54, 56) or mixed methods(38, 43) to explore determinants of sodium restriction.

Table 2.

Description of studies of determinants of sodium restriction in heart failure patients

| Reference | Location | Study Type | Sample Size | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bennett, 2005(32) | USA | Descriptive, Cross-sectional | Sample 1: n=101, Sample 2 n=205 | Sample 1: heart failure patients from VA heart clinics and private practice, Sample 2: inpatients from county and VA hospitals |

| Bentley, 2005(33) | Southern USA | Qualitative descriptive study | n=20 | Convenience sample of community-dwelling heart failure patients receiving care at heart failure clinic |

| Bidwell, 2018(34) | Southeastern USA | Secondary analysis of cross-sectional baseline data from prospective trial | n=114 patient-caregiver dyads | Patient-caregiver dyads from 3 outpatient heart failure clinics |

| Chung, 2006(35) | Kentucky, Ohio, Australia | Comparative descriptive study | n=68 | heart failure outpatient clinic patients |

| Chung, 2015(36) | Kentucky, Georgia, Indiana | Secondary analysis | n=379 | heart failure outpatients who objectively followed sodium restricted diet |

| Chung, 2017(37) | Kentucky, USA | Cross-sectional descriptive study | n=74 | Community-dwelling outpatients with chronic heart failure from 2 community hospitals and 1 academic medical center |

| Dickson, 2013(38) | USA | Mixed-methods concurrent nested study | n=30 | Black adults with confirmed heart failure recruited from heart failure clinic and inpatient units at urban medical center |

| Dunbar, 2016(39) | Southeastern USA | Secondary analysis of baseline data from randomized controlled trial | n=117 patient-family dyads | Patient-family dyads from 3 outpatient heart failure clinics |

| Gary, 2006(40) | USA | Descriptive study | n=32 | Women over 50 with diagnosed heart failure from outpatient clinic |

| Jiang, 2013(41) | Taiwan | Qualitative descriptive study | n=12 | Elderly Chinese heart failure patients |

| Heo, 2009(42) | Southern USA | Qualitative descriptive study | n=20 | Convenience sample of patients with heart failure from outpatient clinics |

| Holden, 2015(43) | Southern USA | Descriptive observational study | n=30 patients, n=14 informal caregivers | Patients with heart failure and their informal caregivers |

| Hooker, 2018(44) | USA | Cross-sectional study of baseline data from randomized controlled trial | n=99 patient-caregiver dyads | Patient-caregiver dyads identified as part of randomized controlled trial with n=314 participants |

| Kollipara, 2008(45) | Dallas, TX, USA | Observational | Sample 1: n=97, Sample 2: n=48 | heart failure patients treated at urban public hospital serving indigent patients |

| Lennie, 2008(46) | USA and Australia | Observational | n=246 | Patients with heart failure referred from academic medical centers |

| Luyster, 2009(47) | USA | Cross-sectional | n=88 | heart failure patients with a mean age of 70 years, treated with ICD |

| Nieuwenhuis, 2011(48) | Netherlands | Cross-sectional correlational study | n=84 | heart failure patients |

| Rong, 2017(49) | China | Qualitative descriptive study | n=15 | Subjective sample of Chinese heart failure patients |

| Schnell-Hoehn, 2009(50) | Canada | Cross-sectional | n=65 | Convenience sample of ambulatory heart failure patients recruited from outpatient clinics |

| Sethares, 2014(51) | Northeastern USA | Exploratory, longitudinal descriptive design | n=78 | heart failure patients recruited from community hospital |

| Sheahan, 2008(52) | USA | Qualitative design | n=33 | Older women aged 65–98 residing in 3 congregate living facilities in the high-risk “coronary valley” of USA |

| Song, 2009(53) | Seoul, South Korea | Prospective study | n=254 | heart failure patients referred from outpatient heart failure clinics at two tertiary medical centers |

| Subramanian, 2008(54) | Midwestern USA | Cross-sectional | n=259 | heart failure patients receiving care at 2 VA hospitals |

| Van der Wal, 2010(55) | Netherlands | Qualitative descriptive study | n=15 | heart failure patients participating in multicenter trial |

| Wu, 2017(56) | Midwestern USA | Secondary analysis of cross-sectional study | n=244 | heart failure patients from clinics associated with 3 large community hospitals/academic medical centers |

Content Analysis

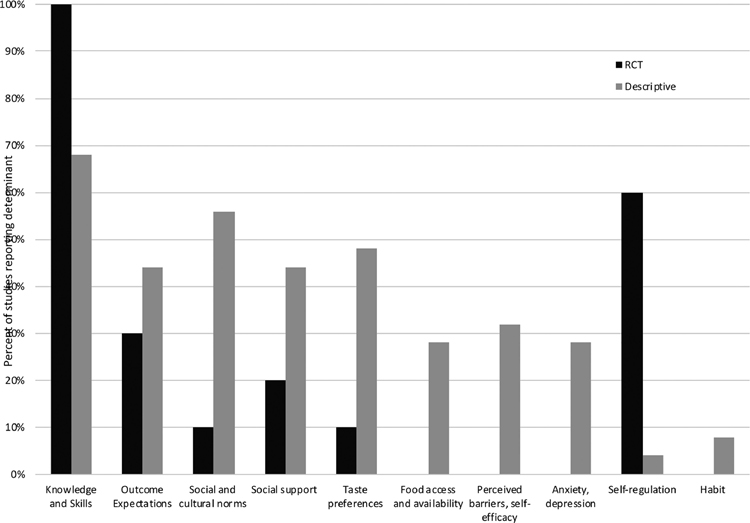

Nine determinants of sodium restricted dietary behavior consistent with health behavior theories were addressed across the 35 studies in our review: knowledge and skills, outcome expectations, social and cultural norms, social support, taste preferences, food access and availability, perceived barriers and self-efficacy, self-regulation, and habit. We added mental health (i.e., anxiety and/or depression) as a determinant of sodium restriction because it was also common in included studies. The final set of determinants included in the content analysis is summarized in Figure 2. Below we present a summary of how determinants were addressed in randomized controlled trials and descriptive studies. The findings of this content analysis are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework dietary behavior change mediators in heart failure

Table 3.

Content Analysis of intervention targets

| Reference | Knowledge and Skills | Outcome Expectations | Social and cultural Norms | Social support | Taste preferences | Food access and availability | Perceived barriers, self-efficacy | Anxiety, Depression | Self-regulation | Habit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trials | ||||||||||

| Alvez, 2012 | X | X | ||||||||

| Arcand, 2005 | X | X | ||||||||

| Athar, 2018 | X | X | ||||||||

| Colin-Ramirez, 2004 | X | |||||||||

| Dunbar, 2013 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Otsu, 2012 | X | X | X | |||||||

| Philipson, 2013 | X | X | ||||||||

| Veroff, 2012 | X | |||||||||

| Welsh, 2013 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Young, 2016 | X | X | ||||||||

| Descriptive Studies | ||||||||||

| Bennett, 2005 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Bentley, 2005 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Bidwell, 2018 | X | X | ||||||||

| Chung, 2006 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Chung, 2015 | X | X | X | |||||||

| Chung, 2017 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Dickson, 2013 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Dunbar, 2016 | X | X | ||||||||

| Gary, 2006 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Jiang, 2013 | X | X | X | |||||||

| Heo, 2009 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Holden, 2015 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Hooker, 2018 | X | X | ||||||||

| Kollipara, 2008 | X | |||||||||

| Lennie, 2008 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Luyster, 2009 | X | |||||||||

| Nieuwenhuis, 2011 | X | |||||||||

| Rong, 2017 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Schnell-Hoehn, 2009 | X | X | ||||||||

| Sethares, 2014 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Sheahan, 2008 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Song, 2009 | X | |||||||||

| Subramanian, 2008 | X | X | ||||||||

| Van der Wal, 2010 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Wu, 2017 | X | |||||||||

The 10 randomized controlled trials addressed fewer determinants than the descriptive studies. The six determinants identified in the content analysis that were addressed in the randomized controlled trials included: knowledge and skills,(22–31) outcome expectations,(24, 26, 30) social and cultural norms,(28) social support,(26, 27) taste preferences,(30) and self-regulation.(22, 23, 26, 27, 31)

All 10 determinants were discussed across the 25 descriptive studies: knowledge and skills,(32–38, 40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 49, 52, 54, 55) outcome expectations,(32, 33, 36–38, 41–43, 51, 52, 55) social and cultural norms,(32, 33, 35–37, 40–42, 46, 49, 51, 52, 56) social support,(33–35, 38, 42–44, 46, 52) taste preferences,(32, 33, 35, 37, 38, 40, 42, 43, 49, 51, 52, 55) food access and availability,(32, 33, 35, 42, 49, 51, 55) perceived barriers and self-efficacy,(32, 37, 38, 44, 48, 50, 54, 56) anxiety and/or depression,(32, 39, 40, 43, 47, 50, 53) self-regulation,(37) and habit.(43, 49)

Knowledge and skills.

All randomized controlled trials intervened on knowledge and skills. Interventions included group education,(22, 23, 26, 27) one-on-one counseling,(24, 25, 27, 28, 31) written materials,(22–26, 28, 31) and a DVD.(26, 29) Education was provided in-person,(22–28, 30, 31) and over the phone.(26, 28, 30, 31) The study that provided a DVD and written handout through the mail in lieu of in-person education was ineffective.(29) Knowledge and skills included information about sodium,(22, 23, 25–28, 30) label reading,(23, 30) recipe adaptation,(26, 28) eating in restaurants,(23) alternative seasoning techniques,(23, 28, 30) and meal planning.(26, 30) Education was provided by registered dietitians,(23, 25, 26) nurses,(26, 30) and ultrasonographers.(24)

Knowledge and skills were important determinants of sodium restricted diet adherence in 17 (65%) of the descriptive studies.(32–38, 40–43, 45, 46, 52, 54, 55) One(45) found only knowledge and skills to be an important determinant of sodium restricted diet adherence, while the other 16 found that other determinants were important in addition to knowledge and skills.

Outcome expectations.

Three of ten randomized controlled trials incorporated outcome expectations by addressing beliefs about the consequences of a behavior and includes perceived risks and perceived benefits.(19) All three interventions discussed the rationale for following sodium restricted diet; two(24, 30) explicitly linked this education to improved outcomes and decreased symptom burden. One(30), which highlighted the relationship between sodium restricted diet and fewer heart failure symptoms, resulted in lower sodium intake at 6 months. Another(24), which aimed to motivate patients by using ultrasound to show patients damage to their inferior vena cava, was unsuccessful.

Eleven (44%) of the descriptive studies illustrated how outcome expectations were related to sodium restricted diet.(32, 33, 35, 37, 38, 41–43, 51, 52, 55) Individuals were motivated to participate in self-care, including a sodium restricted diet, in order to experience decreased symptom burden and hospitalization,(55) and improved health and longevity.(51) Descriptive studies also elucidated that those who did not understand or experience the relationship between diet and symptom burden were less likely to adhere to sodium restricted diet.(32, 33, 41, 43) One study reported patients felt that heart failure was inevitable, and therefore unrelated to health behaviors like sodium restricted diet.(38)

Social and cultural norms.

Social norms consist of beliefs about how others think one should behave and perceptions about what others are doing.(19) Only one randomized controlled trial provided dietary education in line with patients’ social and cultural norms, and was effective in reducing urinary sodium.(28) On the other hand, social and cultural norms were associated with sodium restricted diet in 14 descriptive studies.(32, 33, 35–38, 40, 41, 41, 42, 46, 49, 51, 52, 56) Individuals struggled to follow sodium restricted diet if their family did not follow it with them(35, 42). Conversely, individuals whose family members followed sodium restricted diet were more successful.(36) Many did not feel their families would accept low-sodium foods.(40) Eating alone, or eating different low-sodium foods from family members, were barriers to sodium restricted diet.(32, 33, 52) Individuals were more likely to follow sodium restricted diet when they believed it was important to their family or doctor.(37, 56) Lastly, cultural norms, such as traditional medicinal beliefs and cultural foods, influenced sodium restricted diet adherence.(38, 49)

Social support.

Two of ten randomized controlled trial interventions considered social support, though the interventions differed greatly. One successful intervention(26) included a caregiver, most often a spouse, in all aspects of the intervention, including supportive communication and self-care role-playing. In an unsuccessful randomized controlled trial(27), investigators provided a letter to each patient’s family.

Eleven descriptive studies (44%) found social support to influence sodium restricted diet adherence.(33–36, 38, 39, 42–44, 46, 52) Three studies found sodium restricted diet interfered with social life.(33, 46, 52) Informal caregivers influenced sodium restricted diet in five studies(26, 34, 36, 43, 44) and healthcare providers influenced sodium intake in one study.(43)

Taste Preferences.

One randomized controlled trial provided(30) educational activities tailored to taste preferences by helping patients to identify their favorite low-sodium foods at restaurants, plan sample menus, and familiarize themselves with low-sodium substitutes. This intervention resulted in lower sodium intake.

Taste was an important determinant of sodium restricted diet adherence in 12 (48%) of the included descriptive studies.(32, 33, 35, 37, 38, 40, 42, 43, 49, 51, 52, 55) Low palatability of sodium restricted diets was a barrier to adherence,(32, 33, 35, 42, 51) as was preference for saltier foods.(37, 40, 42, 52, 55)

Food Access and Availability.

No randomized controlled trials intervened on food access and availability. However, food access and availability was associated with sodium restricted diet adherence in eight descriptive studies.(32, 33, 35, 40, 42, 49, 51, 55) The cost of healthy food,(32, 40, 49, 51, 55) as well as the difficulty identifying low-sodium foods in grocery stores and on restaurant menus(33, 35) and insufficient low-sodium choices (32, 42, 51) were challenges to sodium restricted diet adherence.

Perceived Behavioral Control and Self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in carrying out an intended behavior.(19) No randomized controlled trials intervened on self-efficacy or perceived behavioral control, while six descriptive studies identified self-efficacy as an important determinant of adherence to a sodium restricted diet.(38, 44, 46, 48, 50, 54) Perceived behavioral control, such as control over diet due to family roles, was also associated with adherence.(46)

Anxiety and Depression.

No randomized controlled trials intervened on mental health. Seven descriptive studies found that anxiety and depression were associated with decreased adherence to sodium restricted diets, with increased anxiety and depression decreasing self-care, including sodium restricted diet.(32, 39, 40, 43, 46, 50, 53)

Self-regulation.

Self-regulation refers to the ability to handle challenges, manage emotions, and avoid temptations.(57) Six of ten randomized controlled trials intervened on self-regulation. Three studies, one of which was effective in reducing sodium intake based on 3-day food records, helped subjects with goal setting;(22, 23, 31) three studies, one of which was successful based on urinary sodium, included self-monitoring.(26, 27, 31) Randomized controlled trials also addressed self-regulation via care planning,(23) reminders and cues,(26) strategies for controlling emotions,(27) and keeping a diary.(30) Only one descriptive study related self-regulation to sodium restricted diet adherence, finding that those who struggled to adhere to sodium restricted diet reported “lacking the will power” to change their diet(37).

Habit.

No randomized controlled trials intervened on habit. Two descriptive studies found that habits incompatible with sodium restricted diet made it difficult for participants to adhere to a sodium restricted diet.(43, 49) For example, one participant reported, “I’ve been eating pork all my life. And sometimes it’s hard to break habits.”(43)

DISCUSSION

In our review and content analysis, we found that although most trialed sodium restricted diet interventions claimed success in reducing sodium intake among heart failure patients, few patients in the included studies achieved the recommended sodium intake of 1,500mg/day. Importantly, the sodium restricted diet interventions tested in the included randomized controlled trials focused primarily on changing participants’ sodium intake by increasing their knowledge and skills and self-regulation about sodium. However, our content analysis of the descriptive studies of dietary sodium restriction among heart failure patients elucidated that many more determinants play an important role in the success or failure of a sodium restricted diet. In the descriptive studies, motivational determinants, like outcome expectations, taste preferences, social norms, and self-efficacy, as well as food access and availability, were important in addition to knowledge and skills. However, these were infrequently addressed in the randomized controlled trials. Furthermore, though self-regulation was not prominent in the descriptive studies, it was commonly addressed in the randomized controlled trials. A comparison of the determinants addressed in the sodium restricted diet randomized controlled trials and those identified in the descriptive studies is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of intervention targets in experimental and descriptive studies

The mismatch between the evidence from descriptive studies and the intervention design of the randomized controlled trials suggests that providing patients with knowledge, skills, and self-regulation strategies as a primary intervention is unlikely to aid them in adopting a sodium restricted diet.(58, 59) This is consistent with the broader evidence base in nutrition education and behavior change.(19) Interventions intended to change behavior must address motivators, facilitators, as well as structural (i.e., environmental) issues, such as food access.(60, 61) None of the randomized controlled trial interventions in our review addressed environmental/policy determinants, such as food access and food security. Theory-based interventions, which by definition indicate that multiple determinants of behavior change are included, have been identified as holding greater potential for success for behavior changes in heart failure patients.(34, 58) Physiological determinants, such as sodium appetitive drive and/or taste sensitivity, are likely also critical,(16) especially in the context of heart failure.(62, 63) Tastelessness of low sodium food was frequently reported as a barrier to adherence in descriptive studies included in this review. Interventions that use health behavior theory and intervene on structural determinants of diet, including food access and taste preferences, and determinants identified as associated with success, may ultimately be more successful in achieving sodium restriction.

Successful behavioral interventions are needed to assess sodium restriction and this study identifies a mechanism by which sodium restricted diets can be improved. Importantly, these findings suggest that the current debate over whether our current sodium restriction guidelines substantially improve outcomes for patients is affected by type III error, i.e., providing the right answer to the wrong question, because sodium restricted diet randomized controlled trials may not, in fact, represent a comparison of outcomes of participants who do and do not follow a sodium restricted diet.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this review. First, many studies we reviewed lacked rigor in determining sodium intake, relying on self-report and dietary recall. Second, definitions of success varied by study, and intervention design was reported inconsistently, making comparison impossible. Third, the descriptions of the behavioral interventions were often poor, making it difficult to ascertain how determinants were addressed and to what extent, also limiting comparison.

CONCLUSIONS

Restricting dietary sodium to 1500 mg/d is recommended for patients with heart failure, but has not been achieved in randomized controlled trials of sodium restricted diets. Moreover, there is a disconnect between behavioral determinants identified in descriptive studies and those applied in interventional trials. Future randomized controlled trials evaluating sodium restriction should address behavioral determinants beyond knowledge, skills, and self-regulation. The behavioral determinants applied in the interventions must be explicitly reported so they may be compared for effectiveness and reproducibility. Given the acuity of illness in this population, well designed and relatively short-term randomized controlled trials should be able to answer whether and how much sodium restriction would be of benefit to this patient population

ClinicalSignificance_R1.

Randomized trials of sodium-restricted diets for patients with heart failure have failed to reach the 1500 mg/day recommended intake.

Sodium restriction interventions in randomized trials do not incorporate many of the determinants shown to be predictive of decreased sodium intake in descriptive studies of sodium restriction among heart failure patients. These include: knowledge/skills, outcome expectations, social/cultural norms, social support, taste, food access, self-efficacy, self-regulation, habit, and mental health.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: NIH T32HL7343-37

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest relevant to this manuscript: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2014;63:1123–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta D, Georgiopoulou VV, Kalogeropoulos AP, et al. Dietary sodium intake in heart failure. Circulation 2012;126:479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adigopula S, Vivo RP, DePasquale EC, Nsair A, Deng MC. Management of ACCF/AHA Stage C heart failure. Cardiol. Clin 2014;32:73–93, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beich KR, Yancy C. The heart failure and sodium restriction controversy: challenging conventional practice. Nutr. Clin. Pract. Off. Publ. Am. Soc. Parenter. Enter. Nutr 2008;23:477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS, Yancy CW, Jessup M, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2013;128:e240–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Son Y, Lee Y, Song EK. Adherence to a sodium-restricted diet is associated with lower symptom burden and longer cardiac event-free survival in patients with heart failure. J. Clin. Nurs 2011;20:3029–3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arcand J, Ivanov J, Sasson A, et al. A high-sodium diet is associated with acute decompensated heart failure in ambulatory heart failure patients: a prospective follow-up study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 2011;93:332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lennie TA, Song EK, Wu J-R, et al. Three gram sodium intake is associated with longer event-free survival only in patients with advanced heart failure. J. Card. Fail 2011;17:325–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett SJ, Huster GA, Baker SL, et al. Characterization of the precipitants of hospitalization for heart failure decompensation. Am. J. Crit. Care 1998;7:168–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuyuki RT, McKelvie RS, Arnold JM, et al. Acute precipitants of congestive heart failure exacerbations. Arch. Intern. Med 2001;161:2337–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Donnell MJ, Mente A, Smyth A, Yusuf S. Salt intake and cardiovascular disease: why are the data inconsistent? Eur. Heart J 2013;34:1034–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doukky R, Avery E, Mangla A, et al. Impact of dietary sodium restriction on heart failure outcomes. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paterna S, Gaspare P, Fasullo S, Sarullo FM, Di Pasquale P. Normal-sodium diet compared with low-sodium diet in compensated congestive heart failure: is sodium an old enemy or a new friend? Clin. Sci. Lond. Engl. 1979 2008;114:221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damgaard M, Norsk P, Gustafsson F, et al. Hemodynamic and neuroendocrine responses to changes in sodium intake in compensated heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 2006;290:R1294–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corotto PS, McCarey MM, Adams S, Khazanie P, Whellan DJ. Heart failure patient adherence: epidemiology, cause, and treatment. Heart Fail. Clin 2013;9:49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wessler JD, Hummel SL, Maurer MS. Dietary interventions for heart failure in older adults: re-emergence of the hedonic shift. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis 2014;57:160–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jovicic A, Holroyd-Leduc JM, Straus SE. Effects of self-management intervention on health outcomes of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord 2006;6:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Contento IR. Nutrition education: linking research, theory, and practice Third Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boren SA, Wakefield BJ, Gunlock TL, Wakefield DS. Heart failure self-management education: a systematic review of the evidence. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc 2009;7:159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lainscak M, Blue L, Clark AL, et al. Self-care management of heart failure: practical recommendations from the Patient Care Committee of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2011;13:115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donner Alves F, Correa Souza G, Brunetto S, Schweigert Perry ID, Biolo A. Nutritional orientation, knowledge and quality of diet in heart failure: randomized clinical trial. Nutr. Hosp 2012;27:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arcand JAL, Brazel S, Joliffe C, et al. Education by a dietitian in patients with heart failure results in improved adherence with a sodium-restricted diet: a randomized trial. Am. Heart J 2005;150:716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Athar MW, Record JD, Martire C, Hellmann DB, Ziegelstein RC. The Effect of a Personalized Approach to Patient Education on Heart Failure Self-Management. J. Pers. Med 2018;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colín Ramírez E, Castillo Martínez L, Orea Tejeda A, Rebollar González V, Narváez David R, Asensio Lafuente E. Effects of a nutritional intervention on body composition, clinical status, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. Nutr. Burbank Los Angel. Cty. Calif 2004;20:890–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Reilly CM, et al. A Trial of Family Partnership and Education Interventions in Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail 2013;19 Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3869235/. Accessed April 19, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otsu H, Moriyama M. Follow-up study for a disease management program for chronic heart failure 24 months after program commencement. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. JJNS 2012;9:136–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Philipson H, Ekman I, Forslund HB, Swedberg K, Schaufelberger M. Salt and fluid restriction is effective in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2013;15:1304–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veroff DR, Sullivan LA, Shoptaw EJ, et al. Improving self-care for heart failure for seniors: the impact of video and written education and decision aids. Popul. Health Manag 2012;15:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welsh D, Lennie TA, Marcinek R, et al. Low-sodium diet self-management intervention in heart failure: pilot study results. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. J. Work. Group Cardiovasc. Nurs. Eur. Soc. Cardiol 2013;12:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young L, Hertzog M, Barnason S. Effects of a home-based activation intervention on self-management adherence and readmission in rural heart failure patients: the PATCH randomized controlled trial. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord 2016;16:176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett SJ, Lane KA, Welch J, Perkins SM, Brater DC, Murray MD. Medication and dietary compliance beliefs in heart failure. West. J. Nurs. Res 2005;27:977–993; discussion 994–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bentley B, De Jong MJ, Moser DK, Peden AR. Factors related to nonadherence to low sodium diet recommendations in heart failure patients. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. J. Work. Group Cardiovasc. Nurs. Eur. Soc. Cardiol 2005;4:331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bidwell JT, Higgins MK, Reilly CM, Clark PC, Dunbar SB. Shared heart failure knowledge and self-care outcomes in patient-caregiver dyads. Heart Lung J. Crit. Care 2018;47:32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung ML, Moser DK, Lennie TA, et al. Gender differences in adherence to the sodium-restricted diet in patients with heart failure. J. Card. Fail 2006;12:628–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung ML, Lennie TA, Mudd-Martin G, Moser DK. Adherence to a low-sodium diet in patients with heart failure is best when family members also follow the diet: a multicenter observational study. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 2015;30:44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung ML, Park L, Frazier SK, Lennie TA. Long-Term Adherence to Low-Sodium Diet in Patients With Heart Failure. West. J. Nurs. Res 2017;39:553–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dickson VV, McCarthy MM, Howe A, Schipper J, Katz SM. Sociocultural influences on heart failure self-care among an ethnic minority black population. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 2013;28:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Stamp KD, et al. Family partnership and education interventions to reduce dietary sodium by patients with heart failure differ by family functioning. Heart Lung 2016;45:311–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gary R Self-care practices in women with diastolic heart failure. Heart Lung J. Crit. Care 2006;35:9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang R-S, Wu S-M, Che H-L, Yeh M-Y. Cultural implications of managing chronic illness: treating elderly Chinese patients with heart failure. Geriatr. Nurs. N. Y. N 2013;34:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heo S, Lennie TA, Moser DK, Okoli C. Heart failure patients’ perceptions on nutrition and dietary adherence. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. J. Work. Group Cardiovasc. Nurs. Eur. Soc. Cardiol 2009;8:323–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holden RJ, Schubert CC, Mickelson RS. The patient work system: an analysis of self-care performance barriers among elderly heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. Appl. Ergon 2015;47:133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hooker SA, Schmiege SJ, Trivedi RB, Amoyal NR, Bekelman DB. Mutuality and heart failure self-care in patients and their informal caregivers. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. J. Work. Group Cardiovasc. Nurs. Eur. Soc. Cardiol 2018;17:102–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kollipara UK, Jaffer O, Amin A, et al. Relation of lack of knowledge about dietary sodium to hospital readmission in patients with heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2008;102:1212–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lennie TA, Worrall-Carter L, Hammash M, et al. Relationship of heart failure patients’ knowledge, perceived barriers, and attitudes regarding low-sodium diet recommendations to adherence. Prog. Cardiovasc. Nurs 2008;23:6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luyster FS, Hughes JW, Gunstad J. Depression and anxiety symptoms are associated with reduced dietary adherence in heart failure patients treated with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 2009;24:10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nieuwenhuis MMW, van der Wal MHL, Jaarsma T. The body of knowledge on compliance in heart failure patients: we are not there yet. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 2011;26:21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rong X, Peng Y, Yu H-P, Li D. Cultural factors influencing dietary and fluid restriction behaviour: perceptions of older Chinese patients with heart failure. J. Clin. Nurs 2017;26:717–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schnell-Hoehn KN, Naimark BJ, Tate RB. Determinants of self-care behaviors in community-dwelling patients with heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 2009;24:40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sethares KA, Flimlin HE, Elliott KM. Perceived benefits and barriers of heart failure self-care during and after hospitalization. Home Healthc. Nurse 2014;32:482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheahan SL, Fields B. Sodium dietary restriction, knowledge, beliefs, and decision-making behavior of older females. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract 2008;20:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song EK. Adherence to the low-sodium diet plays a role in the interaction between depressive symptoms and prognosis in patients with heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs 2009;24:299–305; quiz 306–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Subramanian U, Hopp F, Mitchinson A, Lowery J. Impact of provider self-management education, patient self-efficacy, and health status on patient adherence in heart failure in a Veterans Administration population. Congest. Heart Fail. Greenwich Conn 2008;14:6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van der Wal MHL, Jaarsma T, Moser DK, van Gilst WH, van Veldhuisen DJ. Qualitative examination of compliance in heart failure patients in The Netherlands. Heart Lung J. Crit. Care 2010;39:121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu J-R, Lennie TA, Dunbar SB, Pressler SJ, Moser DK. Does the Theory of Planned Behavior Predict Dietary Sodium Intake in Patients With Heart Failure? West. J. Nurs. Res 2017;39:568–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.St Quinton T, Brunton JA. Implicit Processes, Self-Regulation, and Interventions for Behavior Change. Front. Psychol 2017;8 Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00346/full. Accessed August 4, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riegel B, Moser DK, Anker SD, et al. State of the science: promoting self-care in persons with heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009;120:1141–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Durose CL, Holdsworth M, Watson V, Przygrodzka F. Knowledge of dietary restrictions and the medical consequences of noncompliance by patients on hemodialysis are not predictive of dietary compliance. J. Am. Diet. Assoc 2004;104:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnston DW, Johnston M, Pollard B, Kinmonth A-L, Mant D. Motivation is not enough: prediction of risk behavior following diagnosis of coronary heart disease from the theory of planned behavior. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc 2004;23:533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bellg AJ. Maintenance of health behavior change in preventive cardiology. Internalization and self-regulation of new behaviors. Behav. Modif 2003;27:103–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takamata A, Mack GW, Gillen CM, Nadel ER. Sodium appetite, thirst, and body fluid regulation in humans during rehydration without sodium replacement. Am. J. Physiol 1994;266:R1493–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kochli A, Tenenbaum-Rakover Y, Leshem M. Increased salt appetite in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 2005;288:R1673–R1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]