Abstract

Cancer research of the Warburg effect, a hallmark metabolic alteration in tumors, led to the discovery of several agents targeting glucose metabolism with potential anticancer effects at the preclinical level. These agents’ monotherapy points to their potential as adjuvant combination therapy to existing standard chemotherapy in human trials. Accordingly, several studies on combining glucose transporter inhibitors with chemotherapeutic agents, such as doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and cytarabine, showed synergistic or additive anticancer effects, reduced chemo-, radio-, and immuno-resistance, and reduced toxicity due to lowering the therapeutic doses required for desired chemotherapeutic effects, as compared with monotherapy. The combinations have been specifically effective in treating cancer glycolytic phenotypes, such as pancreatic and breast cancers. Even combining GLUT inhibitors with other glycolytic inhibitors and energy restriction mimetics seems worthwhile. Though combination clinical trials are in the early phase, initial results are intriguing. The various types of GLUTs, their role in cancer progression, GLUT inhibitors, and their anticancer mechanism of action have been reviewed several times, but not much has been reviewed with respect to their utilization as combination therapeutics.Here we review glucose transporter inhibitors, the agents that work directly by binding to glucose transporters to block them or those that work indirectly by depressing GLUT expression or competing with glucose to bind at the active site of GLUT, as combination chemotherapeutic agents. This review mainly focused on summarizing the effects of various combinations of GLUT inhibitors with other anticancer agents and providing a perspective on the current status.

Keywords: Glucose transporters (GLUTs), GLUT inhibitors, Combination strategy, drug synergy, cancer

1. Introduction

Several decades ago, Otto Warburg, a German biochemist, noticed the differential utilization of glucose by cancerous versus normal cells[1]. He observed that, while producing ATP from glucose, normal cells follow the TCA cycle leading to glucose oxidative phosphorylation. In contrast, cancerous cells, even in the presence of oxygen, convert glucose to lactate, and this effect was then known as the ‘Warburg effect’[2,3]. Since then, the effect of glucose metabolism in various cancer cells has been studied extensively, reflecting the potential application of agents that target different pathways, receptors, and enzymes involved in glucose metabolism.

The metabolic shift of glucose to lactate in cancer cells gives less ATP per glucose molecule metabolised. Hence, to meet the higher energy needs of multiplying cancer cells, glucose demand in these cells is higher than in normal cells. Expectedly, cancer cells need accelerated rates of glucose uptake to support their augmented energy supply, biosynthetic, and redox needs[4], leading to overexpressed glucose transporters (GLUTs, SLC2 gene family). This overexpression has been reported several times in almost every type of cancer[5], suggesting an active role of glucose transporters in cancer proliferation and growth[6,7]. Therefore, to offset the tumor gluttony for glucose, GLUT inhibitors could restrict glucose entry into the tumor cells, leading to starvation[8] followed by death and or growth inhibition[9]. Indeed, several GLUT inhibitors, both natural products and small synthetic molecules, were found to restrict the in vitro and in vivo cell growth in various cancers[10,11]. Natural products exhibiting GLUT inhibition include flavonoids and polyphenolic compounds, for ex., Naringenin[12], Myricetin, Quercetin[13], Isoquercetin[14], Kaempferol[15], Phloretin[16,17], Apigenin[18], Silibinin[19], Xanthohumol[20], Cytochalasin B[21], Curcumin[22], Resveratrol[23], Caffeine[24], Theophylline[25], (+)-Cryptocaryone[26], and Melatonin[27]. Amongst the synthetic ligands, a wide variety of chemical scaffolds have been reported, viz, Fasentin[28], STF-31[29], WZB117[30], Curcumin based EF24[31], xanthane derivative PUG-1[32], ketoximes[33], polyphenolic esters[34], pyrazolo-pyrimidines[35], quinazolines[36], phenylalanine amides[21] and many more [11,37–40].

The types and structures of various GLUT isoforms[41,42], the role of GLUTs in tumor development[6,43], targeting strategies for GLUTs[9,44], the antitumor effects of GLUT inhibitors[10,45], and their application in cancer therapy[46] have been reviewed several times. Still, not much has been critically reviewed about combining GLUT inhibitors effectively with other anticancer agents. Reviewing recent studies on the effects of GLUT inhibitors combined with other anticancer agents will provide needed insight into the exact applications of GLUT inhibitors as adjuvants of chemotherapeutic agents for future considerations. Therefore, this review mainly focuses on effects of various combinations of GLUT inhibitors with other anticancer agents (Figure 1). Here we review the agents that work directly by binding to glucose transporters to block them or those that work indirectly by depressing GLUT expression or competes with glucose to bind at the active site of GLUT (collectively referred as glucose transporter inhibitors in the review), as combination chemotherapeutic agents by summarizing the effects of various combinations of GLUT inhibitors with other anticancer agents.

Figure 1.

Pictorial representation of the preclinical evaluation of the combinations of GLUT inhibitors with other chemotherapeutic agents in various types of cancers.

2. Combination studies of GLUT inhibitors from natural sources.

During their transport, GLUTs undergo conformational changes that open the substrate cavity alternately to each side of the membrane. GLUT inhibitors can interfere with the transport by hindering the cycling between the two major states of the transporter: outward-facing (substrate cavity opened towards the lumen) and inward-facing (substrate cavity opened towards the cytosol) or blocking glucose access in one or both types of conformational states. Cytochalasin B is a well-known GLUT inhibitor, which binds to the endofacial side of the transporter[47]. It inhibits GLUT isoforms from class I (GLUT1–4), but not those from class II (GLUT5, 7, 9 and 11). GLUT inhibitors obtained from the natural origin such as Cytochalasin B, Phloretin, Apigenin, Curcumin, Trehalose, Silibinin and Genistein (Figure 2) have been studied to seek the combined effect along with other clinical agents in various types of cancer cells and models showing advantage over monotherapy (either with GLUT inhibitor or agent studied in combination) and are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of the natural GLUT inhibitors that have been studied for combination anticancer effects.

Table 1.

Effect of combination treatments of natural compound GLUT inhibitors with other therapeutic agents in various types of cancers.

| Combination | Cancer type | MOA proposed | Anticancer effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytochalasin B + Antimycin A/Leucascandrolide | Lung | ↓ lactate ↓OXPHOS ↓ ATP |

In vitro synergistic effects | [48] |

| Compound 17 + Antimycin A/Leucascandrolide | Lung Ovarian Glioma Prostate |

↓ lactate ↓OXPHOS ↓ ATP |

In vitro synergistic effects | [48] |

| Compound 18+ Antimycin A/Leucascandrolide | Lung Ovarian Glioma Prostate |

↓ lactate ↓OXPHOS ↓ ATP |

In vitro synergistic effects | [48] |

| Cytochalasin B + Vincristine | T-cell lymphoma Mastocytoma B-cell lymphoma |

↑DNA fragmentation | In vitro synergistic effects | [49,50] |

| Cytochalasin B + Doxorubicin | Resistant Leukaemia |

↓ Resistance, independent of glycolytic inhibition | Sensitization of resistant cells in vitro | [51]. |

| Phloretin + Cisplatin | Lung | ↓ BcL-2, ↓ MMP-2, ↓ MMP-9, ↑cleaved Caspases |

Synergistic effects in vitro | [53] |

| Phloretin + chaperone | Myeloid Leukaemia |

↑HSP70 cellular penetration, |

Enhanced anticancer effects in vitro and in vivo | [55] |

| Phloretin + Daunorubicin | Colon Myeloid leukaemia |

↓ GLUT1, ↓HIF-1 α ↑Apoptosis | Combat chemoresistance of Daunorubicin in vitro. | [56] |

| Silibinin + Doxorubicin | colorectal adenocarcinom a |

↓ Glycolytic activity, ↑Sensitization of cells | Sensitization of resistant cells to overcome chemoresistance. | [57] |

| Silibinin + Gefitinib/erlotinib | Prostate | ↓ Glycolytic activity, ↓ EGFR |

Combat T790M-mediated drug resistance and tumor suppression in vivo | [58] |

| Silibinin + Metformin | Colorectal | ↓ Alt, ↓p-AMPK, ↑ act. Caspase 3 |

Enhanced in vitro apoptosis. | [59] |

| Silibinin + EGCG | Lung HUVEC cells |

↓ VEGF, ↓ Wnt signaling, ↑Bax, Cell cycle arrest, Apoptosis |

Synergistic antiangiogenic and antiproliferative effects in vitro | [60] |

| Silibinin + Paclitaxel | Ovarian | ↑tp21, ↑p53, ↓ P-gp mediated inactivation of Paclitaxel, ↓mRNA of ABC transporters, ↓efflux of drugs |

Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects in vitro and two-fold increased oral bioavailability in vivo | [61], [62], [63] |

| Silibinin + Doxorubicin | Prostate | ↓cyclin B1, ↓p34 | Synergistic anticancer effects with cell cycle arrest | [64,65] |

| Silibinin + Cytarabine | Acute myeloid leukaemia | Not defined well | Reduced therapeutic dose, reduced toxicity, synergistic anticancer effects in vitro | [67] |

| Apigenin + Radiotherapy | laryngeal carcinoma |

↓ GLUT1, Modulation of AKT/AMPK pathway |

In vivo improved the radiosensitivity | [69]. |

| Apigenin + Cisplatin | laryngeal carcinoma |

↓ GLUT1, ↓ Akt, ↓ COX-1,2, ↓ Il-6, ↑GSH |

In vitro chemo-sensitization and reduced nephrotoxicity in vivo. | [18], [70] |

| Apigenin + 5-Fluorouracil | Breast | ↓ ErbB2, ↓ Akt | In vitro synergistic antiproliferative effects, 5-FU dose reduction, combat ErbB2 induced chemoresistance. | [71] |

| Apigenin + Immunotherapy (DNA vaccine, E7-hsp70) | E7-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cells | Renders the tumor cells more vulnerable to lysis by the DNA vaccine. | [72] | |

| apigenin + Gefitinib | Lung (EGFR mutant- resistant NSCLC) |

↓c-Myc, ↓HIF-1α ↓EFGR, ↓AMPK ↓Glucose uptake |

Synergistic anticancer effects and apoptosis induction, reduced chemoresistance. | [76]. |

| Apigenin + Abivertinib | B-cell Lymphoma |

↓p-GS3K-β | Enhanced anticancer effects in vitro and in vivo. | [77] |

| Apigenin + Sorafenib | Hepatoma | ↑ Caspase3/8/9/10 ↑ p53, p21, p16 |

Reduced migration and invasion, induction of apoptosis and gene expression in vitro | [73]. |

| Curcumin + GLUT1 AS-ODN + Radiotherapy | laryngeal carcinoma |

↑Autophagy, ↑Apoptosis |

Enhanced radiosensitivity. | [78] |

| Genistein + Celecoxib | Prostate | ↓ GLUT1, ↓COX2, ↑ ROS, ↓GSH |

Synergistic apoptotic effects | [79]. |

| Trehalose + Temozolomide | Melanoma | ↑Autophagy, ↓Akt, ↓ GLUT1 |

Reduced therapeutic dose, Reduced clonogenicity | [81] |

| Trehalose + Temozolomide + Radiotherapy | Melanoma | ↑Autophagy, ↓Akt, ↓ GLUT1 |

Reduced therapeutic dose and enhanced radiosensitivity. | [81] |

Abbreviations are MOA for mechanism of action, OXPHOS for oxidative phosphorylation…

Cytochalasin B, combined with an OXPHOS (oxidative phosphorylation) inhibitor that blocks the mitochondrial function, such as Antimycin A or Leucascandrolide A, caused a rapid and synergistic depletion of intracellular ATP in highly glycolytic lung cancer cells- A549. Derivatives of Cytochalasin B, compounds 17 and 18 (Figure 2), non-competitive inhibitors of GLUT1, suppressed ATP synthesis in combination with Antimycin A or Leucascandrolide in A549 cells (lung), CHO-K1 (ovarian) cells, glioma cells, and prostate cancer cells; lactate production was also diminished in the same cell lines. Reduced lactate production is an indirect measure of decreased glucose entry in the cells due to glucose transport inhibition by Cytochalasin B. Inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation by blocking mitochondrial electron transport with Antimycin A or Leucascandrolide A alone, had only a minor effect on the highly glycolytic A549 lung cancer cells, but supplementing with Cytochalasin B, rapidly depleted intracellular ATP, revealing synergistic effects of the combined agents[48]. Combining Cytochalasin B with Vincristine exhibited the highest rate of DNA fragmentation as compared to the treatment with Cytochalasin B or Vincristine alone in EL4 (T-cell lymphoma), P815 (mastocytoma),CH33, and LS102.9 (B-cell lymphoma) cells[49,50]. Cytochalasin B was also found to synergize with Doxorubicin (ADR) against ADR-resistant P388/ADR leukaemia cells, a cell line in which neither Cytochalasin B nor ADR showed any substantial inhibitory activity alone; however this synergistic effect seemed independent of glucose transport inhibition by Cytochalasin B [51].

Phloretin is another well-known GLUT inhibitor, affecting class I GLUTs[52]. Recent studies have reported that combined treatment of Phloretin and Cisplatin in A549 cells can augment Cisplatin’s therapeutic effects by facilitating the deregulation of Bcl-2, MMP-2, and MMP-9 and upregulation of cleaved-caspases[53]. Inhibition of Bcl-2 extended the effect of metabolic reprogramming[54]; hence these synergistic effects of Phloretin with Cisplatin could be attributed to GLUT inhibition by Phloretin. Abkin et al. studied the antitumor effect of recombinant HSP70 (heat shock protein 70) Chaperone, in combination with Phloretin, and found that penetration of HSP70 in K562 cells increased and its anti-cancer effect was improved in vitro and in vivo. Notably, the combined treatment elevated cytotoxicity by 16–18 % in vitro compared to treatment with HSP70 alone and almost fivefold reduced tumor weight for combination-treated mice compared to untreated mice in vivo[55]. Combined treatment with glucose transporter inhibitors has also been an effective method to overcome chemoresistance associated with Daunorubicin. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) increases the expression of GLUT1 under hypoxic conditions, a state often seen in tumors and known to contribute to chemotherapeutics resistance. Inhibition of GLUT1 via Phloretin was shown to overcome this hypoxia-induced resistance when used in combination with Daunorubicin. Thus, inhibition of glucose uptake by Phloretin sensitized Daunorubicin-resistant SW620 and K562 cancer cells to its anticancer effects and apoptosis by overcoming drug resistance developed due to hypoxia [56].

Silybin (Silibinin), a recently verified glucose transporter modulator, seemed to be a decent contender to target the accelerated glucose metabolism in human colorectal adenocarcinoma resistant to Doxorubicin (LoVo DOX) cells. When it was combined with Doxorubicin, they exerted synergistic effects by sensitizing resistant cells to Doxorubicin’s chemotherapeutic effects. A recent strategy to overcome resistance to routine chemotherapeutics is to combine them with other agents, converting resistant cells to sensitive cells. Most resistant cell types are highly glycolytic phenotypes due to alteration in tumor metabolism. In such cases, combining resistant chemotherapeutic agents with Sylibin is a useful strategy [57]. In lung cancer, T790M mutations are responsible for acquired resistance to EFGR-TKIs (epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors). Silybin’s addition to therapy with EFGR-TKIs, Gefitinib or Erlotinib, helped overcome T790M-mediated drug resistance indicating that Silybin possesses antitumor effects including through EGFR downregulation; the combination of Silybin and Erlotinib efficiently blocked tumor growth in erlotinib resistance-bearing PC-9 xenografts. Thus, the addition of Silybin to EGFR-TKI therapy is a promising strategy to combat T790M-mediated drug resistance[58]. Cotreatment of colorectal cancer COLO-205 cells with Metformin and Silybin caused decreased cell survival, inhibition of Akt phosphorylation, and AMPK phosphorylation activation. It resulted in increased expression of activated caspase-3 leading to apoptosis and enhanced antiproliferative effects[59]. Adding Silybin (50 μM) to the antiangiogenic therapy with epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) (50 μg/ml) on human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) reduced cell viability by 70%, compared to treatment with single agents. The antiangiogenic effects of EGCG were associated with the Wnt signaling pathway through VEGF gene targeting, while those of Silybin were due to cell cycle arrest and induction of apoptosis as a result of upregulation of Bax, and modulation of Akt and necrosis factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathways. In the same study, the combination of Silybin and EGCG exerted antimigratory effects on HUVEC and lung cancer A549 cells, demonstrating a notable synergistic effect of Silybin and EGCG as an antiangiogenic and antiproliferative combination[60]. A major limitation of the chemotherapeutic agent Paclitaxel, apart from poor oral bioavailability, is P-gp (P-glycoprotein) mediated first-pass metabolism in the liver and small intestine. Several in vivo and in vitro studies have highlighted the modulation of Paclitaxel’s oral bioavailability when combined with Silybin. In vitro evaluation of the combination of Paclitaxel (0.02 μM) with Silybin (50 μM) in human epithelial ovarian cancer SKOV-3 cells showed improved cytotoxicity and apoptosis induction, attributed to upregulation of tumor suppressor genes p21 and p53[61]. In a study involving co-administration of Silybin (0.5, 2.5, or 10 mg/kg) with Paclitaxel (40 mg/kg) to rats orally [62], the peak plasma concentration of Paclitaxel increased and so did its oral bioavailability (up to 2 fold). Silybin has shown downregulation of mRNA levels for some ABC transporter proteins, leading to modulation of drug efflux and enhanced anticancer activity[63]. In prostate cancer PCA cells, Silybin had strong synergy with Doxorubicin showing strong G2/M cell cycle arrest[64]. The underlying mechanism of the silybin/doxorubicin combination’s strong effect could be due to reduced cyclin B1 expression and p34 kinase activity[64,65]. Interestingly, Silybin also synergized very well with Cisplatin, Doxorubicin, or Carboplatin in human breast cancer, MCF7, and MDA-MB-468 cells[66]. A combination of Silybin (10 μM) and Cytarabine in acute myeloid leukaemia cells displayed synergistic anticancer potential and decreased the IC50 value of Cytarabine in vitro by 4.5 fold, thereby reducing the therapeutic dose and associated toxicity. However, the underlying mechanism of the synergistic effects is not well defined[67].

Apigenin, a GLUT1 inhibitor, has antitumor activity against various cancers[68]. The cotreatment of laryngeal carcinoma with Apigenin improved the radiosensitivity of xenografts in nude mice. After X-ray radiation, tumor size was considerably reduced in the mice group treated with 100 μg Apigenin and 10 Gy radiation compared to the group receiving only 10 Gy radiation. Apigenin’s effects on tumor growth and in promoting xenograft radiosensitivity may be linked to lowered expression of GLUT-1 via modulation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway[69]. In laryngeal carcinoma Hep-2 cells, in vitro, combining Apigenin(10–160 μM) with Cisplatin(5 μg/ml) enhanced chemosensitivity of Cisplatin in a dose-dependent manner, through suppression of GLUT1 and p-Akt levels[18]. Apigenin exerts antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Co-administration of Apigenin with Cisplatin in rats significantly reduced the nephrotoxic effects of Cisplatin by decreasing blood urea nitrogen levels, creatinine, expression of COX (I and II) enzymes, and interleukin-6, with increased levels of GSH, thereby leading to neuroprotective effects[70]. In human breast cancer MDA-MB-453 cells co-administration of Apigenin (5, 10, 50 or 100 μM) with 5-Fluorouracil(5-FU) (90 μM) enhanced antiproliferative effects with a reduced dose of 5-FU. Relatively higher concentrations of 5-FU alone were needed to elicit the effect (IC50>170 μM), possibly owing to developed resistance due to overexpression of ErbB2. Adding Apigenin to 5-FU downregulated ErbB2 and Akt signaling, leading to increased sensitivity of MDA-MB-453 cells to 5-FU[71]. Apigenin has also been studied as an adjuvant to immunotherapy, wherein the treatment of mice with Apigenin (25mg/kg) prior to the administration of the DNA vaccine (E7-hsp70) (2 μg) showed that Apigenin rendered the tumor cells more vulnerable to lysis by the DNA vaccine (E7-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cells), leading to enhanced tumor growth suppression. Thus, Apigenin shows promise of its utility in combination to immunotherapy[72]. The synergistic effects of combination of Apigenin and Sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma Hep-G2 cells have also been established; the combined treatment reduced cell migration and invasion, induced apoptosis and gene expression in vitro[73]. There are also reports of combining GLUT inhibitors with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, as a few studies have demonstrated that resistance to TKIs is associated with increased glucose metabolism in tumor cells[74,75]. The combined use of Apigenin and Gefitinib in EGFR mutant-resistant NSCLC cells (EGFR L858R-T790M-mutated H1975) caused dysregulated metabolism and apoptotic cell death by inhibiting oncogenic drivers such as c-Myc, HIF-1α, and EFGR, downregulation of AMPK signaling pathway, and impaired glucose uptake and utilization by EGFR mutant-resistant cells[76]. Thus, combining Apigenin with Gefitinib is a critical approach in the treatment of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs. Apigenin has also improved the effects of the BKT inhibitor, Abivertinib, in B-cell lymphoma in vitro and in vivo by inhibiting p-GS3K-β and its downstream targets[77].

Curcumin and GLUT-1 AS-ODN (GLUT1 antisense oligodeoxynucleotides) co-treatment improved the radiosensitivity of laryngeal carcinoma in mice through regulating autophagy and inducing apoptosis when administered before exposing to10 Gy radiation[78].

Nano-formulations of combined drugs have also been reported and evaluated in prostate cancer cells. As prostate cancer cells overexpress COX-2 (cyclooxygenase 2) and GLUT1, a nanoliposome formulation incorporating the COX-2 inhibitor, Celecoxib, and the GLUT1 inhibitor, Genistein, was evaluated in vitro. The inhibitor mixture exerted synergistic effects selectively to induce apoptosis in prostate cancer PC-3 cells compared to normal fibroblasts. The mechanism for increased apoptosis involved combined effects of ROS (reactive oxygen species) generation, downregulation of GSH (Glutathione), inhibition of COX-2, and GLUT1[79].

Recently, trehalose, a natural disaccharide of glucose, has been found to exert its antiproliferative effects by blocking GLUTs [80]. It enters the cells via GLUT8 and induces autophagy through modulation of the Akt pathway[80]. Long term treatment of tumors with Temozolomide (TMZ) increases the expression of GLUTs, triggering higher glycolytic activity, and reduced response to the TMZ treatment. Combining trehalose with TMZ caused a highly reduced clonogenicity and improved autophagic effects in melanoma cells. When further merged with radiation therapy, this combination had more pronounced effects at relatively lower drug concentrations as compared to TMZ + radiation or Trehalose + radiation. Thus, Trehalose + TMZ + radiation treatment might be advantageous to melanoma patients, allowing lower doses of TMZ and radiation[81].

3. Combination studies of synthetic small molecule GLUT inhibitors.

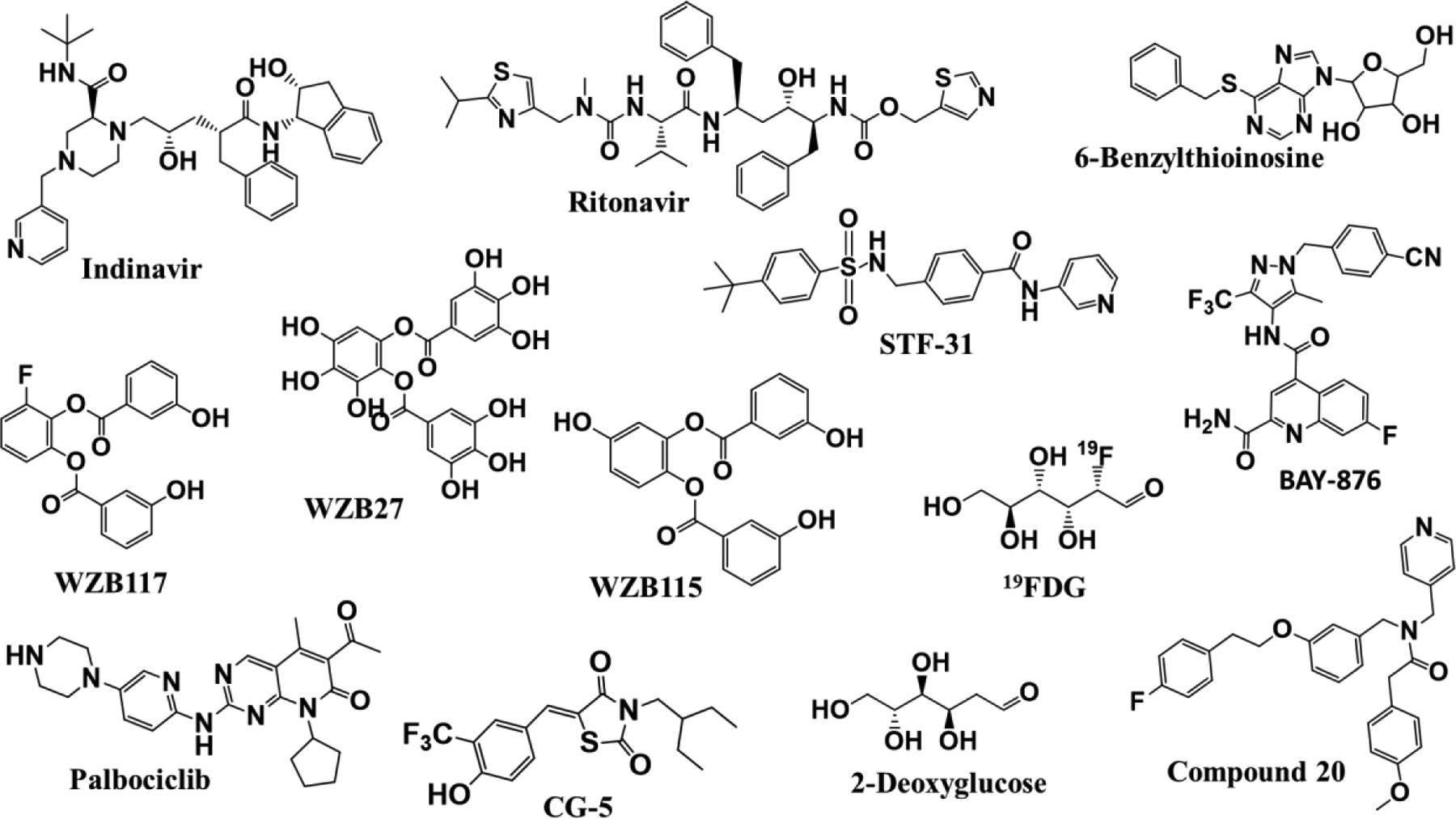

Post observation of in vitro and in vivo anticancer effects of various synthetic, small molecule, GLUT inhibitors reported over a decade shows a few studies that combine GLUT inhibitors with other chemotherapeutic agents for various reasons, ranging from obtaining synergistic effects to circumventing toxic effects associated with routine chemotherapy. The structures of synthetic GLUT inhibitors studied in combination are presented in Figure 3 and combination studies have been potted together in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of the synthetic, small molecule, GLUT inhibitors that have been studied for combination anticancer effects.

Table 2.

Effect of combination treatments of synthetic small molecule GLUT inhibitors with other therapeutic agents in various types of cancers.

| Combination | Cancer type | MOA proposed | Anticancer effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WZB117 + 5-FU | Colorectal | ↓ Resistance | Re-sensitization of resistant cells | [82] |

| WZB117 + Doxorubicin | Breast | ↓ Resistance, ↓Bcl-2 ↓ Akt, ↓ mTOR, ↓ AMPK, ↓GLUTl |

Re-sensitization of resistant cells | [83] |

| WZB117 + MK-2206 | Breast | ↓ Akt ↑ DNA damage ↓Apoptosis |

In vitro synergistic antiproliferative effects | [84] |

| WZB117 + Radiotherapy | Breast | ↓ Radio-resistance ↓GLUTl |

Re-sensitize to radiotherapy | [85] |

| WZB117 + Gefitinib | Lung | ↓ Resistance | Re-sensitization of resistant cells and in vitro/in vivo synergistic tumor regression | [87] |

| WZB27/WZB115+ Cisplatin/Paclitaxel | Lung Breast |

- | In vitro synergistic antiproliferative effects | [88] |

| WZB117 + Thapsigargin/2-ABP | Osteosarcoma | ↓ Glucose ↑ Cytoplasmic Ca2+

↑ p-RIPK1 |

In vitro synergistic antiproliferative effects | [89] |

| STF31 + Thapsigargin/2-ABP | Osteosarcoma | ↓ Glucose ↑ Cytoplasmic Ca2+

↑ p-RIPK1 |

In vitro synergistic antiproliferative effects | [89] |

| BAY-876 + Cisplatin | oesophageal squamous cell | - | Additive antiproliferative effects. | [90] |

| BAY-876 + Paclitaxel | Uterus | ↓ ALDH | In vivo and in vitro tumor suppression. | [91] |

| STF31+ Metformin | Breast | - | In vitro synergistic antiproliferative. | [92] |

| CG-5 + Gemcitabine | Pancreas | ↓ ribonucleotide reductase M2 | Sensitization of resistant cells in vitro, synergistic antiproliferative effects in vivo. | [93] |

| 6-BT + Metformin | Acute myeloid leukaemia | ↓ GLUT1 ↓Glycolysis ↓ATP |

In vitro synergistic antiproliferative effects | [94] |

| Ritonavir + Doxorubicin | Multiple Myeloma |

↓ Resistance | Sensitization of resistant cells | [98] |

| Ritonavir + Temozolomide | Glioma | - | Additive antiproliferative effects | [99] |

| Ritonavir + Aprepitant | Glioma | ↓ GLUT1, ↓Glycolysis, ↓NK-1, ↓ Akt | Synergistic antiproliferative effects | [99] |

| Ritonavir + BCNU | Glioma | - | Five-fold Dose reduction, Increased survivals in vivo. | [101] |

| Indinavir + BCNU | Glioma | - | Additive antiproliferative effects | [102] |

| 2-DG + Mibefradil | Breast | Cell cycle synchronization, | Synergistic antiproliferative effects, Cell cycle arrest | [104] |

| 2-DG + FTS | Pancreas | ↓ Ras, ↓HIF-1α, ↓ATP |

Synergistic antiproliferative effects in vitro and in vivo | [105] |

| 2-DG + Metformin | Breast Prostate |

↑ Caspase 3, ↑ Apoptosis, ↓ Lactate ↓AMPK, ↑Autophagy |

Synergistic antiproliferative effects in vitro and in vivo, cell cycle arrest | [107] |

| 2-DG + Cisplatin/Oxaliplatin | Ovarian Pancreas |

- | Synergistic antiproliferative effects in vitro | [111] |

| 2-DG + Doxorubicin/Paclitaxel | Lung Osteosarcoma |

In vivo synergistic effects and prolonged survival | [112] | |

| 2-DG + Etoposide | Murine mammary adenocarcinom a |

↓ATP- dependent P-gp mediated efflux of Etoposide, ↓ Glycolysis |

Synergistic effects, increased drug accumulation. | [115] |

| 2-DG + Fenofibrate | Breast Melanoma Osteosarcoma |

↑ ER stress, ↑ AMPK, ↓ATP, ↓ GRP78, ↑Apoptosis |

Synergistic effects | [120] |

| 2-DG + Metformin | Lung CSCs | ↓ Resistance | Synergistic effects | [121] |

| 2-DG + 10058-F4/LY294002 | Lymphoma | Additive antiproliferative effects | [122] | |

| 2-DG + Erlotinib | Oral | ↓ GLUT1, ↓ EFGR ↓LDHA | Synergistic antiproliferative effects | [86] |

| 2-DG + Paclitaxel | Oral | ↓ PARP, ↑Apoptosis ↓ Resistance |

Sensitization of resistant cells, synergistic antiproliferative effects | [86] |

| 2-DG + SB203580 | Lymphoma | - | Additive antiproliferative effects | [122] |

| 2-DG + PD98059 | Lymphoma | - | Additive antiproliferative effects | [122] |

| 19FDG + Doxorubicin | Cervical | ↑Apoptosis, ↑Necrosis |

Synergistic antiproliferative effects in vitro. | [126]. |

| Compound 20 + ABT-199 | Myeloma | ↑Apoptosis | Synergistic antiproliferative effects in vitro. | [127] |

| Compound 20 + Dexamethasone | Myeloma | ↓ Resistance | Synergistic antiproliferative effects in vitro. | [127] |

| Compound 20 + Melphalan | Myeloma | ↓ Resistance | Synergistic antiproliferative effects in vitro. | [127] |

| Palbociclib + Paclitaxel | Breast | ↓Rb/E2F/c-myc | Synergistic antiproliferative effects in vitro. | [128] |

| Palbociclib + BYL719 | Breast | ↓PI3K/mTOR, ↓Rb/E2F/c-myc, ↓GLUTl, ↓ATP |

Synergistic antiproliferative effects in vitro. | [129] |

The overexpression of GLUT1 leading to an elevated glycolysis rate has been found responsible for developing chemoresistance in colorectal HCT116 cells, and cotreatment with 5-FU and the GLUT1 inhibitor WZB117 restored the sensitivity of resistant HCT116 cells to 5-FU treatment[82]. WZB117 cotreatment also helps to overcome doxorubicin resistance in resistant MCF7 breast cancer cells by restoring their sensitivity to doxorubicin, possibly through activating BAX translocation to mitochondria, activating AMPK, and downregulating mTOR pathway[83]. Combined treatment of breast cancer cells with WZB117 and the Akt inhibitor, MK-2206,also showed synergy in inhibiting the proliferation of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231cells by effects that caused greater Akt phosphorylation, compromised DNA repair mechanism, and induced DNA damage, collectively leading to apoptotic cell death[84]. Associating WZB117 with radiotherapy also appeared promising in treating radioresistant MCF7 and MD-MBA-231 breast cancer cells. The radioresistant breast cancer cells overexpressed GLUT1, and inhibiting its glucose transport with WZB117 before exposure to radiation helped to re-sensitize the cells to radiotherapy through glucose metabolism regulation[85]. In Gefitinib-resistant non-small cell lung carcinoma PC-9-R cells, combining WZB117 (7.5 μM) with Gefitinib (10.0 μM)inhibited the cells much more efficiently than either drug alone, consistent with previous observations of combined treatments of GLUT inhibitors and TKIs[76,86]; similar effects of combined treatment were further corroborated in A549 xenografts, in vivo. Interestingly, the same combination did not show any inhibitory effects on human fetal lung fibroblasts (IMR-90), indicating selectivity for non-small cell lung carcinoma [87]. Other derivatives with GLUT1 inhibition capacity, WZB27, and WZB115, coupled with Cisplatin or Paclitaxel in lung cancer (A549 and H1299) and breast cancer (MCF7) cells, also exhibited synergistic effects[88]. A patent report highlights that combining sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase inhibitors, Thapsigargin or 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-ABP), with STF-31 or WZB117, in human osteosarcoma U20S cells, synergistically inhibited glucose entry and increased the cytoplasmic calcium level, producing receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIPK1)- dependent cancer cell death. Elevated cytosolic calcium levels promote protein phosphatase 2A (PP2Ac) demethylation, leading, through RIPK1 phosphorylation, to cell death; glucose deprivation induces PP2Ac demethylation through influx of cytosolic calcium, thus causing synergistic effects. In all treatment concentrations, these combinations did not interfere with human normal lung fibroblasts (WI-38) glucose levels, indicating targeted effects in cancer cells[89].

Based on the finding that GLUT1 suppression by siRNA (small interfering RNA) amplified inhibition of proliferative oesophageal squamous cell cancer (ESCC) TE-11 cells, which overexpress GLUT1, Sawayama et al. evaluated Cisplatin coupled with a potent GLUT1 inhibitor, BAY-876, to examine if similar effects can be observed. As anticipated, BAY-876 effectively sensitized ESCC TE-8 and TE-11 cells when combined with Cisplatin additively. Cisplatin (0.5 μmol/L) with BAY-876 (0.025 nmol/L) caused 79.9% ± 2.3% inhibition of TE8 cells when compared to treatment with either drug alone, 59.9% ± 4.9% (cisplatin) and 38.1% ± 3.1% (BAY-876), at the same concentrations. Similar additive results were observed in TE-11 cells[90].Mori et al. have shown that inhibition of GLUT1 by BAY876 sensitized uterine endometrial cancer patient-derived spheroid cells to Paclitaxel. Also, it synergistically suppressed the tumor propagation of in vitro spheroid cells and in vivo spheroid cell-transplanted mice. Proposedly, the mechanism was the inhibition of ALDH (aldehyde dehydrogenase) dependent glycolytic activation [91].

The potency of GLUT1 inhibitor, STF31, was enhanced by Metformin to inhibit breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation, compared to these drugs alone. STF31 (1.9 μM) reduced the cell number to 78% and Metformin (3mM) to 87%; their combination at the indicated concentrations reduced the cell number to 37% compared to untreated cells, indicating strong synergistic effects [92].

CG-5, a thiazolidinedione (TZD) derivative, exhibited GLUT1 inhibition and antitumor effects. Coupled with Gemcitabine, it caused higher tumor growth suppression than either drug alone in the panc-1 xenograft model in vivo. Emerging resistance limits the gemcitabine treatment for pancreatic cancer. Combining it with CG-5 resensitizes Gemcitabine resistant Panc-1 cells by upregulating Gemcitabine-induced expression of ribonucleotide reductase M2 catalytic subunits to overcome drug resistance[93].

6-BT(6-benzylthioinosine) and Metformin synergistically promote cell death in FLT3-ITD AML (acute myeloid leukaemia) cells [94]. A potential role for Metformin in AML therapy has been considered; however, high levels of Akt in AML enhance glycolysis and may account for Metformin resistance[95,96]. Coupling Metformin with glucose transporter inhibitors, such as 6-BT, may help overcome resistance by controlling the enhanced glycolysis. Combination drug therapy caused substantial intracellular ATP depletion with simultaneous depletion of extracellular glucose levels. The treatment of AML cells with Metformin decreased oxidative phosphorylation with a concomitant increase in glycolysis. Adding 6-BT dramatically reduced the glycolytic flux and GLUT1 mRNA expression. Thus, impaired glycolysis by 6-BT in AML cells probably accounts for the robust synergistic effects seen upon combination with Metformin[94].

Recently, the HIV protease inhibitor, Ritonavir [97], with pan inhibitory effects on GLUT1/3/4, was found beneficial when used in combination. Glucose transporters are essential for the maintenance of multiple myeloma cells. The off-target GLUT inhibitor Ritonavir recapitulates the Doxorubicin chemotherapeutic sensitivity in L363 multiple myeloma cells[98]. In the GAMG glioma cell line, Ritonavir (25 μM), Temozolomide (TMZ) (300 μM), and Aprepitant (15 μM), when used as single agents, exhibited 14.04%, 13.8%, and 6.71% growth inhibition, respectively. When these agents were combined, additive or more than additive growth inhibition of glioma cells was observed, indicating possible drug synergy. Combining Ritonavir and Temozolomide at the same above concentrations exerted additive growth inhibition of 34.03%, whereas combining Ritonavir and Aprepitant (NK-1 receptor antagonist) led to 64.48% growth inhibition, showing synergy. Thus,Ritonavir’s combination with either Temozolomide or Aprepitant has additive cytotoxic effects [99]. TMZ, an important adjuvant chemotherapeutic agent in gliomas, upregulates expression of GLUT family members; hence, Ritonavir’s inhibition of glucose uptake may be advantageous in glioblastoma therapy. Also, the synergistic effects of Ritonavir with Aprepitant are encouraging, as the NK-1 antagonist exerts apoptotic effects by decreasing the kinase activity of the AKT pathway[100], whereas Ritonavir, as an extended effect of GLUT inhibition, interferes with AKT signalling ; AKT pathway is obstructed at two points, resulting in drug synergy and anti-glioma activity[99]. In vivo investigation of Ritonavir (100 mg/kg) combined with BCNU (1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea) (1 mg/kg) in GL261 glioma tumors increased the overall survival period of animals and allowed an almost five-fold reduction in the routine therapeutic dose of BCNU (6 mg/kg) commonly given in mice for brain tumor therapy[101]. On the other hand, a more specific GLUT4 inhibitor, Indinavir, demonstrated synergistic effects only with BCNU and not with TMZ, indicating that multiple (PAN) GLUT inhibition is necessary for the drug synergy [102].

2-DG(2-deoxy-D-Glucose) is a competitive inhibitor of glucose in both GLUT1 and GLUT4 transport. It has anticancer effects in various cancers and has been studied extensively as an adjuvant agent in combination therapy[103]. Cell cycle modulators, such as Mibefradil (a T-type calcium channel inhibitor with antiproliferative effects) (10 μM), when combined with 2-DG (1.0 or 2.5 mM), enhanced the anticancer efficacy of the latter in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Mibefradil causes cell-cycle synchronization by arresting the cell cycle at the G1/S interphase. This cell cycle synchronization at the G1/S interphase may augment the therapeutic effect of 2-DG by induction of the S phase[104]. Combining farnesylthiosalicylic acid (FTS), a Ras inhibitor, with 2-DG sensitizes the pancreatic cancer cells to the effects of 2-DG. The combination was synergistic in antiproliferative effects and induction of apoptosis in vitro and in vivo by inhibition of active Ras and reduction in HIF-1α expression leading to energy crises[105]. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of 2-DG with Metformin showed the combination to be effective in breast and prostate cancer. Metformin (1 and 5 mM) and 2-DG (1 mM) induced a 95% inhibition of cell viability in LNCaP cells compared to 70% and 37% inhibition caused individually by 2-DG (1 mM) and Metformin(5 mM), respectively; the combination induced apoptosis by caspase 3 activation, whereas each drug alone did not. Additionally, the combination arrested cells in the G2/M phase, decreased lactate production, and downregulated the AMPK pathway. Thus, the AMPK mediated energetic stress caused by this combination was responsible for apoptosis and enhanced antitumor effects in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. However, a matter of concern about this combination was that the concentration used had exhibited a few toxic effects on normal cells. [106]. In breast cancer cells, the combination of 4 mM 2-DG with 6 mM Metformin was more efficacious in inducing cell death and causing tumor regression in vivo compared to Metformin or 2-DG treatment alone. These enhanced antitumor effects of the combination are associated with decreased cellular ATP levels, extended activation of AMPK, and sustained autophagy [107]. In glycolytic phenotypes of breast cancer cell lines, HCC1806 and MDA-MB-231, the combination was more effective at lower doses (1.25 mM 2-DG and 2.5μM Metformin) [108]. A few pancreatic and ovarian cell lines have been considered as glycolytic tumor phenotypes. Compared to low glycolytic cancer cell types, highly glycolytic cancer cells need higher concentrations of 2-DG to compete effectively with glucose and block glycolysis[109]. In such cases, the combination of glycolysis inhibitors and other anticancer agents could benefit treating these cancers. The combination of 2-DG with Cisplatin in highly glycolytic ovarian cancer and Oxaliplatin in highly glycolytic pancreatic cell lines has enhanced antitumor effects. Activation of the p38 MAPK pathway has been associated with resistance to Cisplatin[110]. Hence, the addition of a p38 MAPK inhibitor further enhanced the antitumor efficacy of the above combinations. Combining glycolysis inhibitors and p38 MAPK inhibitors with chemotherapy may be a promising method to target glycolytic tumor phenotypes effectively [111]. In vivo experiments in human osteosarcoma and MV522 lung tumor carcinoma in nude mice demonstrated that combining 2-DG (500 mg/kg) with either ADR (18 mg/kg) or Paclitaxel (16 mg/kg) increased the antitumor efficacy of these chemotherapeutic agents in terms of tumor growth inhibition and prolonged survival of treated animals[112]. The underlying mechanism for this synergy could be that inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation either by mitochondrial inhibitors or hypoxic conditions makes glycolysis the primary energy source for cell survival, rendering the cells hypersensitive to glycolysis inhibitors[113,114]. Combined treatment of 2-DG with Etoposide in vivo in Ehrlich ascites tumor (EAT) bearing mice helped reduce the therapeutic doses of Etoposide [115], which was toxic and mutagenic at higher treatment doses[116]. As a topoisomerase inhibitor, Etoposide has cytotoxic activity by forming cleavable complexes with DNA[117]. However, its cytotoxic effect is insufficient to produce cell death since the DNA complexes become reversible with drug removal. Further, it has been shown that the dissociation of DNA-Etoposide complexes and the topoisomerase activities demand energy[118]. Thus, combining Etoposide with glycolysis inhibitors, such as 2-DG, can alter the repair and recovery processes, hampering the cleavable complexes’ reversal due to reduced energy supply. Cotreatment with 2-DG causes high Etoposide retention due to inhibition of its ATP-dependent P-gp mediated efflux [119]. Thus, enhanced drug accumulation and depletion of energy required to dissociate the reversible complexes could be the mechanisms driving drug synergy of Etoposide and 2-DG. Combining 2-DG with the cholesterol-lowering agent Fenofibrate has been evaluated in breast carcinoma (SKBR 3), melanoma (NM2C5,) and osteosarcoma (143B) cells. Fenofibrate (40 μM) and 2-DG (2mM) induced higher energy stress than either drug alone, as indicated by reduced ATP production, increased phosphorylated AMPK, and mTOR downregulation. Inhibition of mTOR blocks GRP78, resulting in greater ER stresses and enhanced overall antiproliferative effects[120]. Treating cancer stem cells (CSCs) with routine chemotherapeutic agents, such as Doxorubicin, Paclitaxel, Hydroxyurea, and Colchicine is a challenge as they show increased levels of stemness markers leading to resistance. In this situation the newly proposed anticancer drugs such as Metformin and 2-DG have shown potential to treat these CSCs in various types of cancers; it will be of interest to evaluate these agents in combination against CSCs. One such combination has been found beneficial in highly resistant human lung cancer H460 cells, compared to noncancer human Beas-2B cells. These studies are in the primary stage and need more attention to establish the synergistic effects[121]. In EGFR overexpressing oral cancer OECM-1 EGFR cells, cotreatment with 2-DG and the EGFR inhibitor Erlotinib synergistically inhibited cell viability compared to either agent alone. Higher EGFR levels have been correlated to the transient increase in glucose transport. Hence, combining Erlotinib with glycolytic inhibitors leads to synergistic effects and accelerated antiproliferative effects. In a similar study, 2-DG was further combined with Paclitaxel to treat resistant Squamous Cell Carcinoma, as elevated levels of EGFR have been associated with Paclitaxel resistance. Combining 2-DG with Paclitaxel re-sensitized Paclitaxel-resistant cells to Paclitaxel by decreasing the glucose levels and controlling the effect of activated EGFR and reduced resistance[86]. Broecker et al. have reported on the synergistic effects of combinations of 2-DG with signalling pathway inhibitors (c-MYC-inhibitor-10058-F4 and LY294002, p38 MAPK inhibitor-SB203580, MEK inhibitor- PD98059) in lymphoma cell lines (OCI-LY3, BJAB and SU-DHL-6), wherein combinations were found to have additive or superior effect in terms of cell kill rate compared to single agents[122]. The pilot results from clinical trials involving 2-DG as monotherapy looks inconclusive and unclear on the toxic and reported side effects[49,177][123,124]. Hence, the current strategy of reintroducing 2-DG in combination treatment, as reported above, at comparatively lower doses to achieve synergistic anticancer effects with currently used chemotherapeutic agents or radiotherapy, may provide promising opportunities to utilize the anticancer benefits of 2-DG while avoiding toxicity issues.

2DG has promising anticancer and GLUT modulatory effects in vitro and in vivo[105,111], but its use has been hindered by several limitations[109,125]. As an alternative to 2-DG, 19FDG has a better ability to inhibit glycolysis without the most concerning limitation of 2-DG of losing effectiveness under hypoxic conditions. Thus, Niccoli et al. studied the effect of combining 19FDG with Doxorubicin and compared its efficacy to that of 2-DG and Doxorubicin in HeLa cells. The apoptotic effect of Doxorubicin, whether alone or in combination with 2-DG, was similar under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. However, the combination of 19FDG and Doxorubicin produced a higher proportion of apoptotic and necrotic cells at all cell cycle stages. Thus, combining Doxorubicin with 19FDG rather than 2DG is more effective in inhibiting glycolysis through GLUT inhibition, decreasing cell viability and proliferation, and inducing apoptosis in vitro normoxic and hypoxic conditions[126].

A United States patent claims the effective combination of a GLUT4 selective inhibitor (Compound 20) with a BH3 mimetic agent (ABT-199), a commonly used steroid (Dexamethasone), and an alkylating agent (Melphalan). In LC63 and JJN3 cells, combining Compound 20 (10 μM) with ABT-199 (0–3 μM) exhibited more significant apoptotic effects than either of these agents alone. In Dexamethasone-resistant MM.1S myeloid cells, the combination of Dexamethasone (0.00195–1.0 μM) with Compound 20 (10 μM) led to cell sensitization to Dexamethasone, demonstrating significant cell death. Interestingly, the combination of Compound 20 with either of these drugs did not impact the viability of non-myeloid cells derived from the bone marrow of MM patients’ samples, indicative of selective effects of the combination on myeloid cells. Compound 20 (10 μM) also sensitized the MM.1S cells to Melphalan (0–4 μM). However, the exact mechanism of these synergistic effects has not been clarified[127].

Palbociclib, originally a cyclin-dependent Kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor, is reported to inhibit GLUT1 mediated glucose uptake by reducing GLUT1 expression level in triple-negative breast cancer MD-MBA-231 cells. It improved the efficacy of Paclitaxel in Palbociclib pre-treated cells through induction of AKT signaling and further downregulation of the Rb/E2F/c-myc cascade[128]. Another study by the same group has reported the combination of Palbociclib with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitor BYL719 wherein MD-MBA-231 cells were pre-treated with Palbociclib followed by treatment with BYL719, leading to synergistic antiproliferative effects through inhibition of both PI3K/ mTOR and CDK4/6/Rb/c-myc signaling and down-regulation of glucose metabolism due to inhibition of GLUT1 expression and glucose uptake, compared to individual drug treatments[129].

4. Combination of GLUT inhibitors with other glycolytic inhibitors and energy restriction mimetic agents (ERMAs).

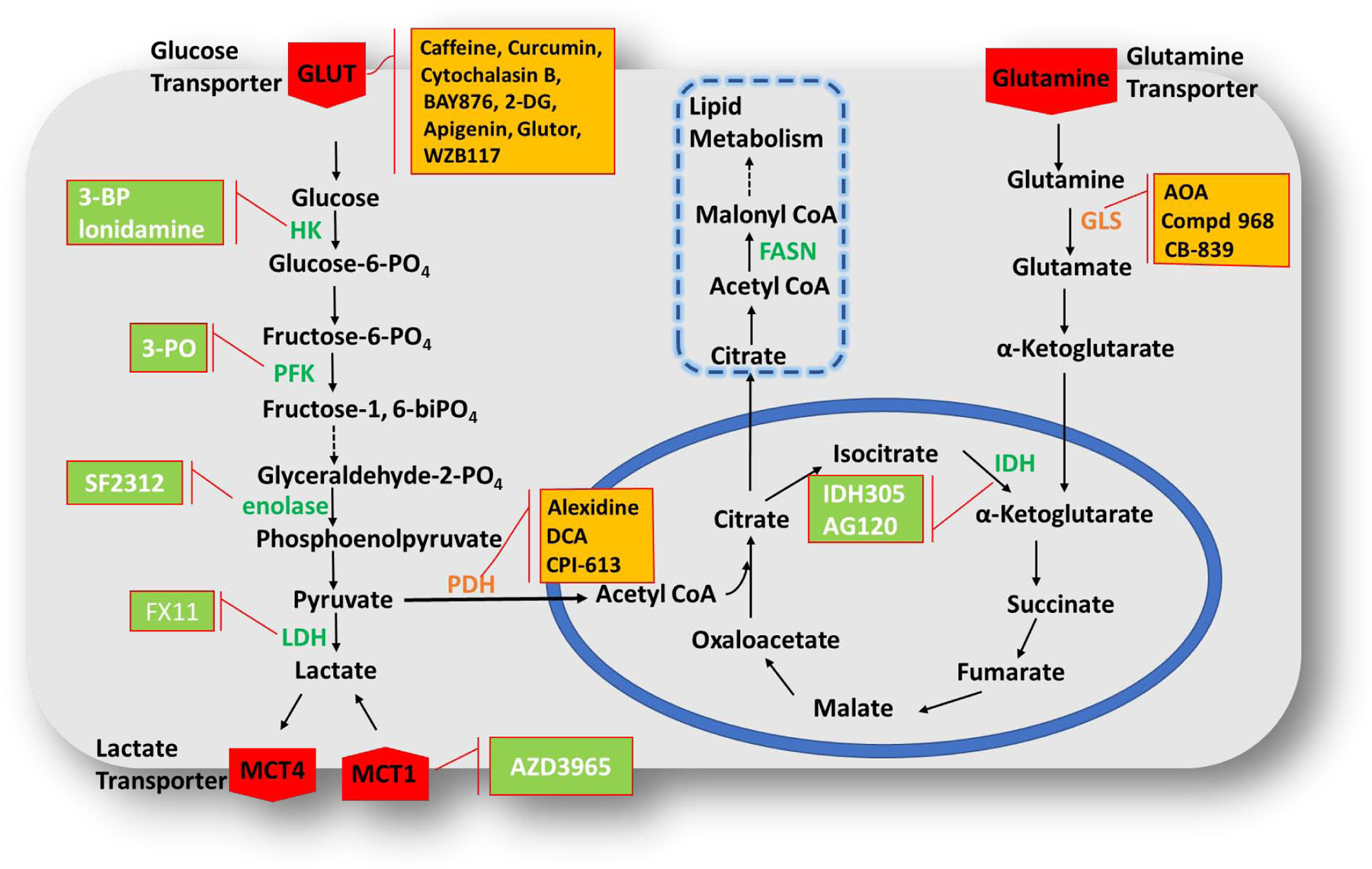

Almost for the last 50 years, tumor bioenergetics is used in oncology for diagnostic and/or prognostic purposes[130]. As soon as glycolysis became known as the main metabolic pathway supplying energy and nutrition for tumor cell proliferation and survival under unfavourable conditions, it got researchers interested in exploiting it for anticancer therapy. Now various enzymes, receptors, and transporters involved in glycolysis and cancer cell energetics are being targeted with small molecules and natural products to suppress tumor growth. All these efforts led to the discovery of GLUT inhibitors, MCT1 (Monocarboxylate transporters) inhibitors, hexokinase 2 (HK2) inhibitors, PGM-1 (Phosphoglycerate mutase) inhibitors, Enolase (ENO) inhibitors, Pyruvate kinase M2 (PK) activators, Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) inhibitors, Pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) kinase inhibitors, and various ERMAs[45]. As these agents are being combined with other chemotherapeutic agents to enhance the anticancer activity, reduce toxicity, or overcome resistance, the mutual combinations of these agents have also been examined to simultaneously attack two checkpoints of energy metabolism pathway leading to synergistic anticancer effects (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The schematic representation of glycolytic and mitochondrial pathways and various enzymes that can be targeted.

The combination of GLUT inhibitors with PDH and GLS inhibitors has already been evaluated (marked in yellow) and further combination studies with HK, PFK, enolase, LDH, and IDH inhibitors (marked in green) can be assumed to have synergistic effects and to overcome metabolic plasticity of tumors. The combination studies with enzymes involved in lipid metabolism/lipogenesis (marked in blue dotted square) can also be conducted to determine synergy, FASN-Fatty acid synthase. Dashed arrow indicates there are more than one steps which are not shown in figure.

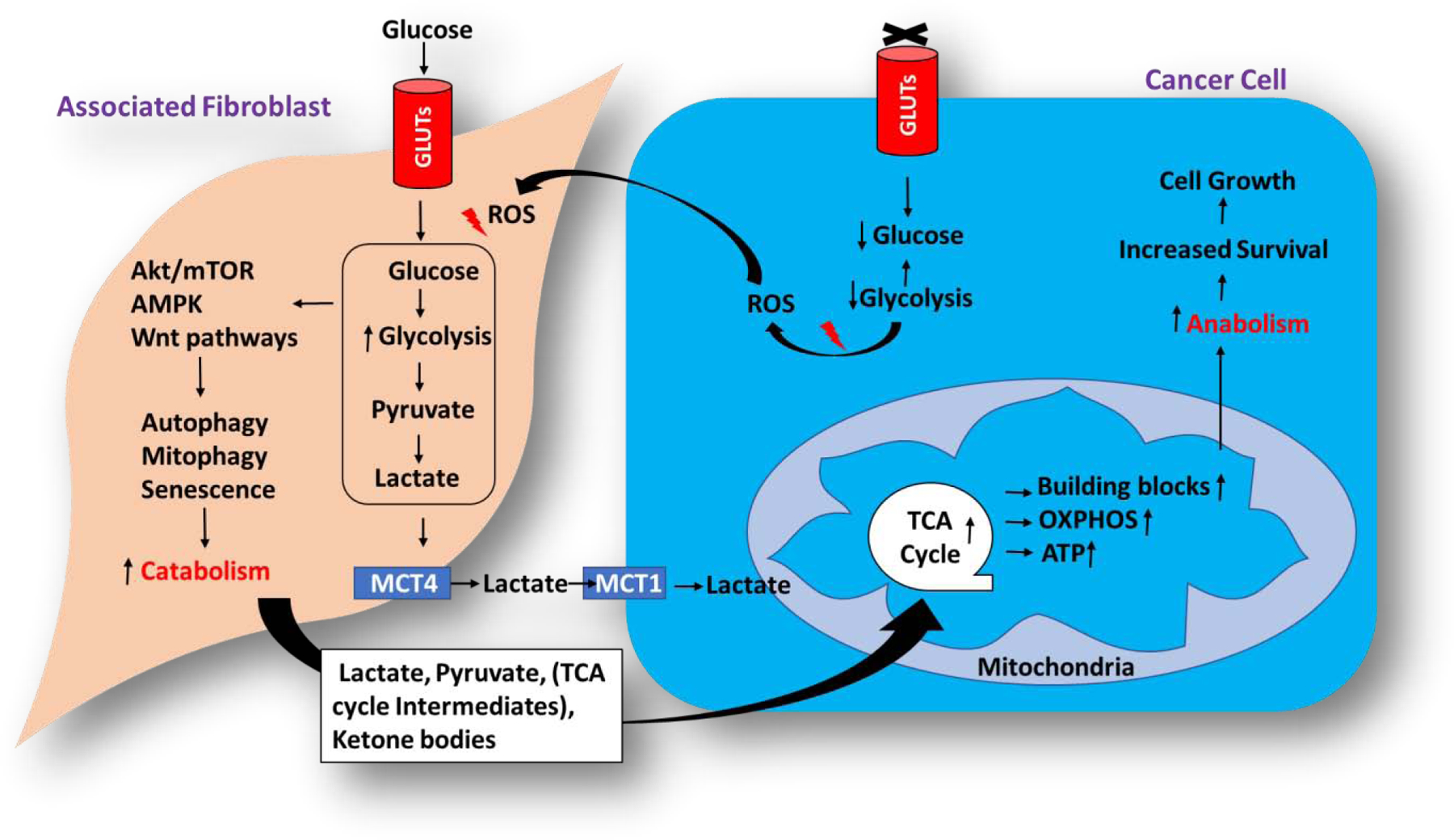

Of late, the concept of the ‘two-compartment’ model, also known as the reverse Warburg effect or metabolic coupling, has spurred re-evaluation of tumor metabolism (Figure 5), with the realization that certain forms of cancer exhibit high mitochondrial respiration and low glycolysis rate[131]. In the two-compartment model, tumor cells form one compartment and adjacent stromal fibroblasts form a second one. They co-operate with each other so that fibroblasts perform aerobic glycolysis, as a result of the acidic atmosphere created in cancer cells, and the generated glycolytic metabolites such as lactate, pyruvate, fatty acids etc., are exported to tumor cells to be funnelled into the TCA cycle for continued ATP generation[132]. This metabolic coupling could lead to the development of resistance and hence combining together the inhibitors of mitochondrial and glycolytic metabolism looks promising in effective treatment of cancer.

Figure 5. The two-compartment model of cancer cell metabolic reprogramming and energy production.

Under reduced glycolytic activities, cancer cells trigger ROS (Reactive oxygen) generation which signals the neighbouring fibroblast to undergo enhanced glycolysis leading to metabolic coupling between the neighbouring associated fibroblast and cancer cells, supporting the survival and growth of the cancer cells. The associated fibroblast cell serves as catabolic compartment utilizing glycolysis for the production of energy and TCA cycle intermediates which are further transferred to the cancer cells wherein, they will be utilised for anabolic processes such as generation of building blocks and production of energy through oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria.

GLUT1 inhibitory effects of Caffeine, when combined with other GLUT1 inhibitors, Curcumin and Cytochalasin B, have been demonstrated. 2DG uptake was measured in L929 cells treated with a combination of Caffeine (20 mM) + Cytochalasin B (20 mM) and Caffeine (20 mM) + Curcumin (100 mM). The inhibitory effects of Cytochalasin B remained unaffected with the addition of Caffeine, in agreement with previous results reported in erythrocytes [24]. However, the combination of Caffeine and Curcumin appeared to be additive, suggesting that these inhibitors may bind at different sites on GLUT1[133]. Indeed docking analysis showed that Caffeine and Cytochalasin B bind to the same endofacial site on GLUT1; hence, their combined inhibitory effects should not be additive[24]. The combination of 2-DG (0.98 g/kg orally) and DCA (Dichloroacetate)(1.5 g/kg orally), an inhibitor of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) kinase utilized effectively for cancer therapy [134], produced substantial antitumor activity when evaluated in Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC). Notably, both compounds were inactive and did not inhibit tumor growth as single agents. Interestingly, DCA, when combined with 2-DG, considerably inhibited tumor growth by about 70% compared to control. The mechanism of the combination could be simultaneous/additive intensification of oxidative phosphorylation in tumor cells through DCA-induced activation of the PDH complex and competitive inhibition of consumption/entry of glucose in tumor cells by 2-DG, consequently decreasing energy supply by blocking the glycolytic pathway. Additionally, the antitumor effects were also attributed to the activation of tumor-infiltrating cells that express the CD14 receptor, leading to alteration of the tumor microenvironment[135]. 2-DG combined with glutaminolysis inhibitor Aminooxaloaceate (AOA) in ovarian cancer SKOV3, IGROV-1, and Hey cells, sensitized these cells to 2-DG by increasing its uptake in the cells, leading to synergistic antiproliferative effects[136]. It has been observed that downregulation of GLUT1 expression by Apigenin sensitized lung cancer cells to inhibition of glutamine utilization, leading to apoptosis and growth suppression. Thus, combining GLUT1/3 inhibitor with a glutamine metabolism inhibitor (glutaminase inhibitor, Compound 968) could synergistically inhibit cancer cell growth by targeting metabolic plasticity[137]. Recently reported piperazine-2-one derivative, Glutor, which is a GLUT1/2/3 inhibitor, has also shown synergy with the glutaminase (GLS) inhibitor CB-839, in colon cancer HCT116 cells. GI50 value of Glutor improved from 428 nm to 10 nm upon the combination with 5 μM of CB-839[138]. Some cancers become addicted to glutamine due to its use for amino acid synthesis and redox balance maintenance that enable accelerated cancer cell growth [139]. Glutamine serves as a source of C and N atoms in fast-dividing cancer cells; hence, modulating glutamine metabolism serves as an effective approach in cancer drug discovery. Thus, co-treatment of glucose transporter inhibitors with glutamine metabolism inhibitors such as GLS inhibitors may show additive effects in cancer cell growth inhibition. Commander et al. have studied the effect of combining PDH inhibitor, alexidine, and GLUT1 inhibitor, BAY-876, in phenotypically heterogeneous breast and lung cancer cells. The leader cells preferentially rely on mitochondrial respiration. The trailing follower cells utilize elevated glucose uptake. Thus, simultaneous targeting of both leader and follower cells with the combination of PDH and GLUT1 inhibitors could hinder cell growth and collective invasion. The combination was synergistic in parental cell lines and leader cells, but not in follower cells, indicating that leader cells are also sensitive to GLUT1 inhibitors. However, the combination was synergistic in inhibiting collective invasion compared to each drug alone. In the same study, further combining BAY-876 with another clinical PDH inhibitor, CPI-613 (Devimistat), replicated the same synergistic effects on invasion, suggesting that the combination of PDH and GLUT1 inhibitors could be an effective tactic for impeding collective invasion in heterogeneous cellular subtypes[140].

The above results demonstrate that dual/multi-targeting the glycolytic pathway may be a promising treatment option. Several new inhibitors, with brilliant anticancer effects, involved in the energy production cascade, including aerobic/anaerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial metabolism, have been identified[11,38–40]. Thus, further combinations of GLUT inhibitors with inhibitors of HK, such as 3-BP (bromopyruvate) and lonidamine[141]; fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (PFK), like 3-PO (3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1- one)[142]; LDH (lactate dehydrogenase), such as FX11[143]; enolase, such as SF2312[144]; IDH (Isocitrate dehydrogenase), such as IDH305, and AG120[145]; MCT1, such as AZD3965[146] (Figure 4), and various such combinations can be evaluated to establish the effects of combination treatments on cancer cell growth and proliferation by overcoming metabolic plasticity acquired in proliferating tumors. Moreover, the targeting of enzymes involved in de novo lipid metabolism (lipogenesis)has shown promising anticancer effects[147,148]. The combination studies of these with glucose transporter inhibitors could prove beneficial in controlling tumor growth.

5. Combinations of Glucose transport inhibitors in clinical trials.

Most of the GLUT inhibitors are in the early preclinical stage, with a few advanced to the clinical trial stages. However, the current outcomes are not very encouraging for monotherapy[149,150]. Silibinin in Phase I trial was effective in HCC (hepatocellular carcinoma) [151] but did not affect the PSA (prostate-specific antigen) levels in prostate cancer [152]. The dose-escalation Phase I study of 2-DG in castrate-resistant prostate cancer led to asymptomatic QTc prolongation, restricting dose-escalation[153]. The combined treatment of 2-DG with radiation therapy in glioblastoma patients was well tolerated, and there were reduced incidences of late radiation effects[154]. In 2014, a phase II study to assess efficacy of combined treatment with erlotinib (Tarceva) and silybin-phosphatidylcholine complex (Siliphos) in patients with EGFR mutant lung adenocarcinoma (NCT02146118) started in Kosin University Gospel Hospital, Busan, Republic of Korea. The study completion date was estimated as March 2016, however, no results were published[155]. More clinical trials are needed to understand better the clinical relevance of the combination hypothesis of GLUT inhibitors.

6. Conclusion

Depending on the tumor type, the efficacy of GLUT inhibitors varies when used as monotherapy; coupling them with other chemotherapeutic agents has tremendous therapeutic potential.

Many in vitro and in vivo studies show that combining GLUT inhibitors with standard chemotherapy agents such as Doxorubicin, Cisplatin, Paclitaxel, and 5-FU can dodge the chemoresistance by re-sensitizing resistant cells to the anticancer effects of the drug. Thus, combining glucose transporter inhibitors with these standard drugs could be an effective strategy to treat drug-resistant tumor types. Apart from chemoresistance, cancer cells exhibit numerous genetic alterations challenging current immunotherapy. Thus, the combination strategy is needed for effective cancer remedy. A few attempts to assess the effects of combining glucose transporter inhibitors with immunotherapy showed promise. Although insufficient to comment, they provide a starting point for investigating how these could integrate with established immunotherapies. Similarly, radio-resistance has also been observed in patients due to repeated radiotherapy. To overcome radio-resistance, a few studies of cotreatment with GLUT inhibitors before exposure to radiotherapy showed improved response of radioresistant tumors to radiotherapy. However, like immunotherapy, more studies are needed to explore the full potential of combining glucose transporter inhibitors with radiotherapy in different tumor types. Combining glucose transporter inhibitors with standard anticancer therapy potentiates chemotherapeutic effects in a synergistic or additive manner leading to more effective anticancer effects. Most of the combination studies reported to date documented primary synergistic effects of these agents. Overall, the downregulation of glycolysis by glucose transporter inhibitors appears to be exceedingly effective in sensitizing cancer cells to varied treatment approaches including chemo-, radio-, and immunotherapy.

The major concern with the current chemotherapeutic agents is the notorious toxicity issues observed at the doses needed to elicit anticancer effects. Doxorubicin causes cardiotoxicity, alkylating agents and Cytarabine are associated with bone marrow depression, including anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia, Cisplatin induces nephro-, cardio-, hepato-, and neurotoxicity. Combining GLUT inhibitors with standard chemotherapy tackles the toxicity issues by reducing the total dose required to attain therapeutic effects. Some tumor types are highly glycolytic phenotypes and more susceptible to the effects of glucose transporter inhibitors than parent tumor types. Combining GLUT inhibitors with standard chemotherapeutic agents in such glycolytic phenotypes completely inhibit the growth in a few tumor types. Hence, depending on the tumor type, combination therapy with GLUT inhibitors can be integrated and tried at the clinical level.

Solo-targeting of glycolysis remains insufficient to control cancer growth due to two reasons. First, cancer cells adopt alternative strategies for glucose supply. Second, the energy requirements and production of essential building blocks are fulfilled by accelerated mitochondrial respiration. As glycolysis and mitochondrial metabolism work together to support cancer cells’ survival and proliferation, attacking simultaneously multiple checkpoints in the glycolytic and mitochondrial pathways has proven a more effective tactic. Several studies combine glucose transporter inhibitors with other glycolysis inhibitors and energy restriction mimetic agents (ERMAs). It seems a promising strategy to deprive cells of energy by inhibiting their metabolic plasticity caused by single agents.

To date, glycolysis inhibitors in clinical trials as monotherapy have not proved fruitful mostly because of off-target effects and low anticancer potency. Hence, their benefits could be better utilized as adjuvant combination therapy rather than monotherapy. In this regard, a couple of clinical trials have been found promising. However, more clinical studies with inhibitors of glucose transport are needed to develop adjuvants in cancer treatment. Thus, the current overview of combination strategies involving glucose transporter inhibitors showcases their potential and the need for further clinical trials to establish their clinical applicability.

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by Indo-Poland joint research program grant from Department of Science and Technology (DST) with reference number DST/INT/Pol/P-27/2016 (to CSR), the United State NIH grant R01GM123103 (to JC).

Abbreviations:

- GLUTs

glucose transporters

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

- SLC2

solute Carrier 2

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic Acid

- ADR

Adriamycin/doxorubicin

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- MMP-2/9

matrix metalloproteinase-2/9

- HSP70

heat shock protein 70

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- EFGR-TKIs

epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- EGCG

epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- NF-κB

necrosis factor-κB

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- COX-1/2

cyclooxygenase 1/2

- GSH

glutathione

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung carcinoma

- GLUT-1 AS-ODN

GLUT1 antisense oligodeoxynucleotides

- TMZ

temozolomide

- 2-ABP

2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate

- RIPK1

receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1

- PP2Ac

protein phosphatase 2A

- ESCC

oesophageal squamous cell cancer

- ALDH

aldehyde dehydrogenase

- TZD

thiazolidinedione

- 6-BT

6-benzylthioinosine

- FLT3-ITD

FLT3 internal tandem duplication

- AML

acute myeloid leukaemia

- NK-1 receptor

neurokinin 1

- BCNU

1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea

- 2-DG

2-deoxy-D-Glucose

- FTS

farnesyl thiosalicylic acid

- EAT

ehrlich ascites tumor

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- CSCs

cancer stem cells

- CDK

cyclin-dependent Kinase

- MCT1

monocarboxylate transporter 1

- HK2

hexokinase 2

- PGM-1

phosphoglycerate mutase

- ENO

Enolase

- PKM2

pyruvate kinase M2

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- PDH

pyruvate dehydrogenase

- ERMAs

energy restriction mimetic agents

- FASN

fatty acid synthase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- DCA

dichloroacetate

- OAA

oxaloacetate

- PFK

fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase

- 3-PO

3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1- one

- IDH

Isocitrate dehydrogenase

- PSA

prostate-specific antigen

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: Authors declares no conflict of interest.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

References:

- [1].Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E, The metabolism of tumors in the body, The Journal of General Physiology. 8 (1927) 519–530. 10.1085/jgp.8.6.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Koppenol WH, Bounds PL, Dang CV, Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism, Nat Rev Cancer. 11 (2011) 325–337. 10.1038/nrc3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Warburg O, On the Origin of Cancer Cells, Science. 123 (1956) 309–314. 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hanahan D, Weinberg RA, Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation, Cell. 144 (2011) 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Szablewski L, Expression of glucose transporters in cancers, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 1835 (2013) 164–169. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Calvo MB, Figueroa A, Pulido EG, Campelo RG, Aparicio LA, Potential Role of Sugar Transporters in Cancer and Their Relationship with Anticancer Therapy, International Journal of Endocrinology. 2010 (2010) 1–14. 10.1155/2010/205357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hamanaka RB, Chandel NS, Targeting glucose metabolism for cancer therapy, The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 209 (2012) 211–215. 10.1084/jem.20120162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Selwan EM, Finicle BT, Kim SM, Edinger AL, Attacking the supply wagons to starve cancer cells to death, FEBS Lett. 590 (2016) 885–907. 10.1002/1873-3468.12121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Barbosa AM, Martel F, Targeting Glucose Transporters for Breast Cancer Therapy: The Effect of Natural and Synthetic Compounds, Cancers. 12 (2020) 154 10.3390/cancers12010154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Granchi C, Fortunato S, Minutolo F, Anticancer agents interacting with membrane glucose transporters, Med. Chem. Commun 7 (2016) 1716–1729. 10.1039/C6MD00287K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Meng Y, Xu X, Luan H, Li L, Dai W, Li Z, Bian J, The progress and development of GLUT1 inhibitors targeting cancer energy metabolism, Future Medicinal Chemistry. 11 (2019) 2333–2352. 10.4155/fmc-2019-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Park JB, Flavonoids Are Potential Inhibitors of Glucose Uptake in U937 Cells, Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 260 (1999) 568–574. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hamilton KE, Rekman JF, Gunnink LK, Busscher BM, Scott JL, Tidball AM, Stehouwer NR, Johnecheck GN, Looyenga BD, Louters LL, Quercetin inhibits glucose transport by binding to an exofacial site on GLUT1, Biochimie. 151 (2018) 107–114. 10.1016/j.biochi.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kwon O, Eck P, Chen S, Corpe CP, Lee J, Kruhlak M, Levine M, Inhibition of the intestinal glucose transporter GLUT2 by flavonoids, FASEB j. 21 (2007) 366–377. 10.1096/fj.06-6620com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Azevedo C, Correia-Branco A, Araújo JR, Guimarães JT, Keating E, Martel F, The Chemopreventive Effect of the Dietary Compound Kaempferol on the MCF-7 Human Breast Cancer Cell Line Is Dependent on Inhibition of Glucose Cellular Uptake, Nutrition and Cancer. 67 (2015) 504–513. 10.1080/01635581.2015.1002625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lorris Betz A, Drewes LR, Gilboe DD, Inhibition of glucose transport into brain by phlorizin, phloretin and glucose analogues, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 406 (1975) 505–515. 10.1016/0005-2736(75)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tsujihara K, Hongu M, Saito K, Inamasu M, Arakawa K, Oku A, Matsumoto M, Na+-Glucose Cotransporter Inhibitors as Antidiabetics. I. Synthesis and Pharmacological Properties of 4’-Dehydroxyphlorizin Derivatives Based on a New Concept., Chem. Pharm. Bull 44 (1996) 1174–1180. 10.1248/cpb.44.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Xu Y-Y, Wu T-T, Zhou S-H, Bao Y-Y, Wang Q-Y, Fan J, Huang Y-P, Apigenin suppresses GLUT-1 and p-AKT expression to enhance the chemosensitivity to cisplatin of laryngeal carcinoma Hep-2 cells: an in vitro study, Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 7 (2014) 3938–3947. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhan T, Digel M, Küch E-M, Stremmel W, Füllekrug J, Silybin and dehydrosilybin decrease glucose uptake by inhibiting GLUT proteins, J. Cell. Biochem 112 (2011) 849–859. 10.1002/jcb.22984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Correia-Branco A, Azevedo CF, Araújo JR, Guimarães JT, Faria A, Keating E, Martel F, Xanthohumol impairs glucose uptake by a human first-trimester extravillous trophoblast cell line (HTR-8/SVneo cells) and impacts the process of placentation, Mol. Hum. Reprod 21 (2015) 803–815. 10.1093/molehr/gav043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kapoor K, Finer-Moore JS, Pedersen BP, Caboni L, Waight A, Hillig RC, Bringmann P, Heisler I, Müller T, Siebeneicher H, Stroud RM, Mechanism of inhibition of human glucose transporter GLUT1 is conserved between cytochalasin B and phenylalanine amides, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113 (2016) 4711–4716. 10.1073/pnas.1603735113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gunnink LK, Alabi OD, Kuiper BD, Gunnink SM, Schuiteman SJ, Strohbehn LE, Hamilton KE, Wrobel KE, Louters LL, Curcumin directly inhibits the transport activity of GLUT1, Biochimie. 125 (2016) 179–185. 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zambrano A, Molt M, Uribe E, Salas M, Glut 1 in Cancer Cells and the Inhibitory Action of Resveratrol as A Potential Therapeutic Strategy, IJMS. 20 (2019) 3374 10.3390/ijms20133374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sage JM, Cura AJ, Lloyd KP, Carruthers A, Caffeine inhibits glucose transport by binding at the GLUT1 nucleotide-binding site, American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 308 (2015) C827–C834. 10.1152/ajpcell.00001.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ojeda P, Pérez A, Ojeda L, Vargas-Uribe M, Rivas CI, Salas M, Vera JC, Reyes AM, Noncompetitive blocking of human GLUT1 hexose transporter by methylxanthines reveals an exofacial regulatory binding site, American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 303 (2012) C530–C539. 10.1152/ajpcell.00145.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ren Y, Yuan C, Qian Y, Chai H-B, Chen X, Goetz M, Kinghorn AD, Constituents of an Extract of Cryptocarya rubra Housed in a Repository with Cytotoxic and Glucose Transport Inhibitory Effects, J. Nat. Prod 77 (2014) 550–556. 10.1021/np400809w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hevia D, González-Menéndez P, Quiros-González I, Miar A, Rodríguez-García A, Tan D-X, Reiter RJ, Mayo JC, Sainz RM, Melatonin uptake through glucose transporters: a new target for melatonin inhibition of cancer, J. Pineal Res 58 (2015) 234–250. 10.1111/jpi.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wood TE, Dalili S, Simpson CD, Hurren R, Mao X, Saiz FS, Gronda M, Eberhard Y, Minden MD, Bilan PJ, Klip A, Batey RA, Schimmer AD, A novel inhibitor of glucose uptake sensitizes cells to FAS-induced cell death, Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 7 (2008) 3546–3555. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chan DA, Sutphin PD, Nguyen P, Turcotte S, Lai EW, Banh A, Reynolds GE, Chi J-T, Wu J,Solow-Cordero DE, Bonnet M, Flanagan JU, Bouley DM, Graves EE, Denny WA, Hay MP, Giaccia AJ, Targeting GLUT1 and the Warburg Effect in Renal Cell Carcinoma by Chemical Synthetic Lethality, Science Translational Medicine. 3 (2011) 94ra70–94ra70. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Liu Y, Cao Y, Zhang W, Bergmeier S, Qian Y, Akbar H, Colvin R, Ding J, Tong L, Wu S, Hines J, Chen X, A Small-Molecule Inhibitor of Glucose Transporter 1 Downregulates Glycolysis, Induces Cell-Cycle Arrest, and Inhibits Cancer Cell Growth In Vitro and In Vivo, Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 11 (2012) 1672–1682. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang D, Wang Y, Dong L, Huang Y, Yuan J, Ben W, Yang Y, Ning N, Lu M, Guan Y, Therapeutic role of EF24 targeting glucose transporter 1-mediated metabolism and metastasis in ovarian cancer cells, Cancer Sci. 104 (2013) 1690–1696. 10.1111/cas.12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ung PM-U, Song W, Cheng L, Zhao X, Hu H, Chen L, Schlessinger A, Inhibitor Discovery for the Human GLUT1 from Homology Modeling and Virtual Screening, ACS Chem. Biol 11 (2016) 1908–1916. 10.1021/acschembio.6b00304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Granchi C, Tuccinardi T, Minutolo F, Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of GLUT Inhibitors, in: Lindkvist-Petersson K, Hansen JS (Eds.), Glucose Transport, Springer New York, New York, NY, 2018: pp. 93–108. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7507-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].George Thompson AM, Iancu CV, Nguyen TTH, Kim D, Choe J, Inhibition of human GLUT1 and GLUT5 by plant carbohydrate products; insights into transport specificity, Sci Rep. 5 (2015) 12804 10.1038/srep12804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Siebeneicher H, Bauser M, Buchmann B, Heisler I, Müller T, Neuhaus R, Rehwinkel H, Telser J, Zorn L, Identification of novel GLUT inhibitors, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 26 (2016) 1732–1737. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cole B, Kim E, Sweetnam P, Wong E, Metabolic inhibitors, WO2012040499A2, 2012. https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2012040499A2/en (accessed July 29, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- [37].Almahmoud S, Jin W, Geng L, Wang J, Wang X, Vennerstrom JL, Zhong HA, Ligand-based design of GLUT inhibitors as potential antitumor agents, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 28 (2020) 115395 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tilekar K, Upadhyay N, Schweipert M, Hess JD, Macias LH, Mrowka P, Meyer-Almes F-J, Aguilera RJ, Iancu CV, Choe J, Ramaa CS, Permuted 2,4-thiazolidinedione (TZD) analogs as GLUT inhibitors and their in-vitro evaluation in leukemic cells, European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 154 (2020) 105512 10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tilekar K, Upadhyay N, Hess JD, Macias LH, Mrowka P, Aguilera RJ, Meyer-Almes F-J, Iancu CV, Choe J, Ramaa CS, Structure guided design and synthesis of furyl thiazolidinedione derivatives as inhibitors of GLUT 1 and GLUT 4, and evaluation of their anti-leukemic potential, European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 202 (2020) 112603 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ceballos J, Schwalfenberg M, Karageorgis G, Reckzeh ES, Sievers S, Ostermann C, Pahl A, Sellstedt M, Nowacki J, Carnero Corrales MA, Wilke J, Laraia L, Tschapalda K, Metz M, Sehr DA, Brand S, Winklhofer K, Janning P, Ziegler S, Waldmann H, Synthesis of Indomorphan Pseudo-Natural Product Inhibitors of Glucose Transporters GLUT-1 and −3, Angew. Chem 131 (2019) 17172–17181. 10.1002/ange.201909518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mueckler M, Thorens B, The SLC2 (GLUT) family of membrane transporters, Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 34 (2013) 121–138. 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Cheeseman C, Long W, Structure of, and functional insight into the GLUT family of membrane transporters, CHC. (2015) 167 10.2147/CHC.S60484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ancey P, Contat C, Meylan E, Glucose transporters in cancer - from tumor cells to the tumor microenvironment, FEBS J. 285 (2018) 2926–2943. 10.1111/febs.14577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Shi Y, Liu S, Ahmad S, Gao Q, Targeting Key Transporters in Tumor Glycolysis as a Novel Anticancer Strategy, CTMC. 18 (2018) 454–466. 10.2174/1568026618666180523105234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Granchi C, Fancelli D, Minutolo F, An update on therapeutic opportunities offered by cancer glycolytic metabolism, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 24 (2014) 4915–4925. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sborov DW, Haverkos BM, Harris PJ, Investigational cancer drugs targeting cell metabolism in clinical development, Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 24 (2015) 79–94. 10.1517/13543784.2015.960077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Devés R, Krupka RM, Cytochalasin B and the kinetics of inhibition of biological transport: a case of asymmetric binding to the glucose carrier, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 510 (1978) 339–348. 10.1016/0005-2736(78)90034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]