Abstract

DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are an evolutionarily conserved family of DNA methylases, transferring a methyl group onto the 5-position of cytosine. Mammalian DNMT family includes three major members that have functional methylation activities, termed DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B. DNMT3A and DNMT3B are responsible for methylation establishment while DNMT1 maintains methylation during DNA replication. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that regulation of DNA methylation by DNMTs is critical for normal hematopoiesis. Aberrant DNA methylation due to DNMT dysregulation and mutations, however, is known as an important molecular event of hematological malignancies, such as DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. In this review, we first describe the basic methylation mechanisms of DNMTs and their function in lymphocyte maturation and differentiation. We then discuss the current understanding of DNA methylation heterogeneity in leukemia and lymphoma to highlight the importance of studying DNA methylation targets. We also discuss DNMT mutations and pathogenic roles in human leukemia and lymphoma. We summarize the recent understanding of how DNMTs interact with transcription factors or cofactors to repress the expression of tumor suppressor genes. Lastly, we highlight current clinical studies using DNMT inhibitors for the treatment of these hematological malignancies.

Keywords: DNA methyltransferases, leukemia, lymphoma, tumor suppressor, DNA methylation

1. Introduction

Methylated DNA was first discovered by Avery and colleagues in the 1940s (McCarty and Avery, 1946; Avery et al., 1995; Moore et al., 2013). Methylation of DNA, however, was not recognized to regulate gene expression until the 1980s (Moore et al., 2013). DNA methylation is catalyzed by the DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) family that transfers a methyl group from S-adenosine methionine (SAM) to the fifth carbon of a cytosine residue (Lyko, 2018). DNA methylation activities of the mammalian DNMT family were described in early biochemical studies on murine cells (Gruenbaum et al., 1982; Bestor and Ingram, 1983, 1985). DNMT1 was molecularly cloned by studying the highly conserved catalytic motifs of bacterial cytosine-5 DNMTs (Bestor et al., 1988). There are five DNMT genes in the human genome: DNMT1, DNMT2, DNMT3A, DNMT3B, and DNMT3L (Lyko, 2018). Among them, DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B have functional methylation activities (Dong, 2001; Edwards et al., 2017; Lyko, 2018; Ren et al., 2018). Although DNMT2 and DNMT3L do not have canonical DNA methyltransferase activity, they share highly conserved sequences with other DNMT members (Dong, 2001; Hermann et al., 2003; Schubert et al., 2003; Goll et al., 2006; Jia et al., 2007a; Lyko, 2018). DNMT1 preferentially binds to hemimethylated CpG dinucleotides rather than unmethylated counterparts (Bestor, 1992). Unlike DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B can methylate various CpG substrates without preference toward hemimethylated CpG dinucleotides (Okano et al., 1998).

DNMT1 methylates nascently synthesized CpGs opposite of methylated DNA on the mother strand during S phase, maintaining the methylation inheritance (Leonhardt et al., 1992; Li et al., 1992; Lei et al., 1996; Okano et al., 1999). In addition to its methylation activity, DNMT1 is known to play a role in the DNA-damage response (Eads et al., 2002; Ha et al., 2011). Compelling evidence from B cell differentiation and induced DNA-damage studies strongly suggest that DNMT1 can act as a genome guardian and an early responder to DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in both B cells and colon cancer cell lines, independently of its catalytic activity (Ha et al., 2011; Shaknovich et al., 2011). After micro-irradiation, DNMT1 is rapidly but transiently recruited to DSBs by interacting with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and ATR effector kinase CHK1 (Ha et al., 2011). Interestingly, DNMT1 has been shown to inhibit aberrant activation of the DNA damage response without exogenous damage (Ha et al., 2011).

2. Functional domains of DNMTs

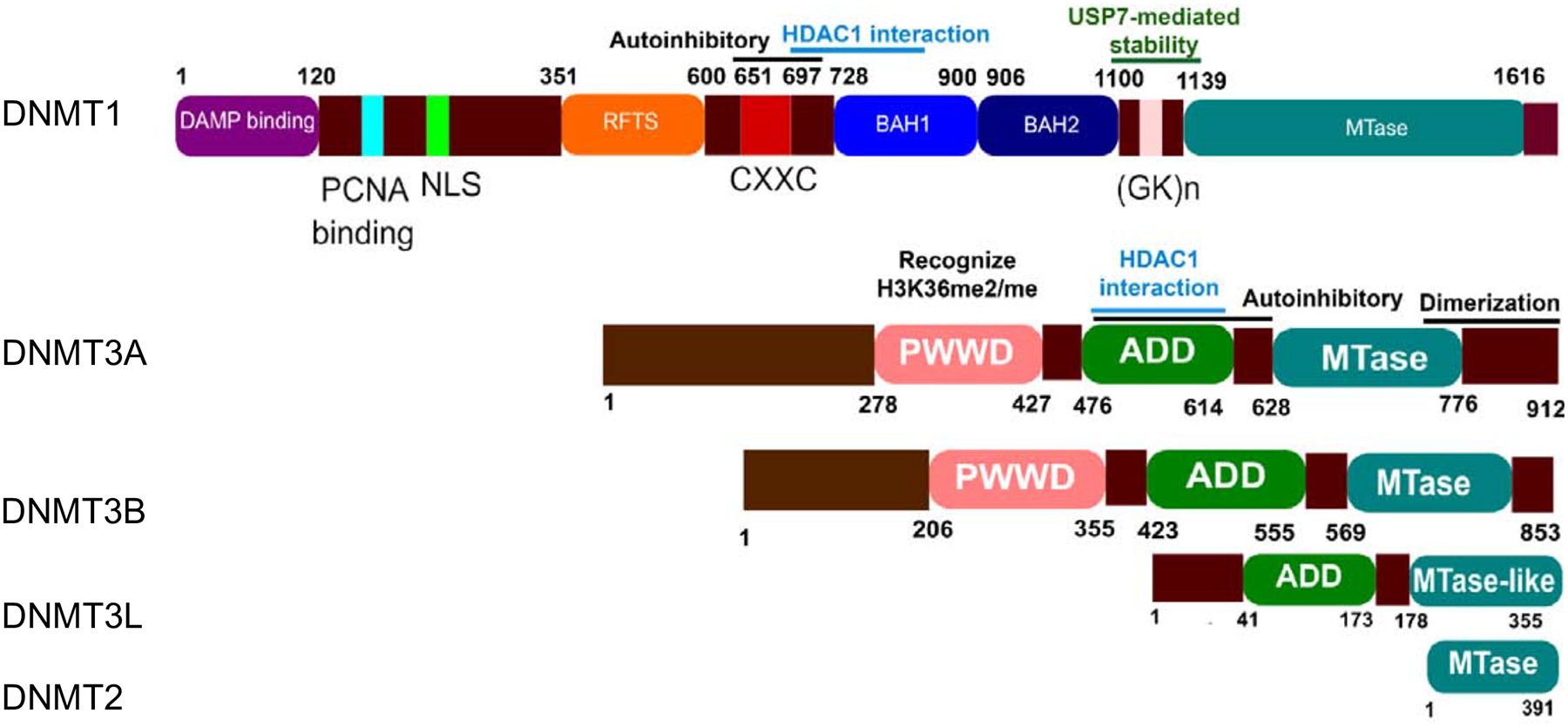

Each DNMT contains multifunctional domains (Fig. 1). The details about their structures are well described in two exceptional reviews (Jeltsch and Jurkowska, 2016; Ren et al., 2018). Briefly, the N-terminus contains multiple domains that regulate their activities and localizations. For instance, the PWWD domain of DNMT3A/3B recognizes di-/tri-methylation of histone 3 lysine 36 (H3K36me2/3) (Baubec et al., 2015; Weinberg et al., 2019). A recent study has shown that the PWWD domain of DNMT3A preferentially binds to H3K36me2 at intergenic regions rather than H3K36me3 in murine embryonic stem and mesenchymal cells (Weinberg et al., 2019). DNMT3B PWWD domain selectively binds to H3K36me3 at gene bodies in mouse stem cells. These co-localizations are associated with increased gene expression.

Fig. 1. Schematic structure of the mammalian DNMT family.

Shown are functional domains of human five DNMT members: DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B, DNMT3L and DNMT2. DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B have a catalytic methyltransferase domain (MTase). DNMT3L and DNMT2 harbor their truncated MTase domain and therefore do not have methyltransferase activity. In addition, DNMT1 has a charge-rich domain containing the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) binding domain, an intrinsically disordered domain with a nuclear localization sequence (NLS), a replication foci target sequence (RFTS), a zinc finger domain (CXXC), and two bromo-adjacent homology domains (BAH 1/2). DNMT3A and DNMT3B have a PWWP domain and an ATRX-DNMTB-DNMT3L (ADD) that is also found in DNMT3L.

The ATRX-like domain (ADD) is multifunctional. The ADD domain of DNMT3A and CXXC-BAH1 of DNMT1 (aa 686–812) can interact with HDAC1 to repress gene expression in a methylation-independent manner (Fuks et al., 2000; Fuks, 2001). The ADD-linker domain mediates spatial precision of DNMT3A targeting by coupling enzymatic autoinhibitory conformation and chromatin recognition (Guo et al., 2015). The magnitude of methylation activity, however, depends on DNMT3A tetramer formation rather than on-off conformation of a single DNMT3A (Holz-Schietinger et al., 2011).

The C-terminus contains the methyltransferase domain (MTase) that catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet) to DNA substrates. The (GK)n repeat of DNMT1 links the regulatory N-terminus to the MTase domain. (GK)n linker mediates DNMT1-ubiquitin-specific Protease 7 (USP7) interaction. Disruption of this interaction by Tip60-mediated acetylation of (GK)n linker leads to a reduction in the protein level of DNMT1.

The C-terminal domain mediates homo and hetero dimerization of DNMT3A. The homo/heterotetramer conformations control the progressive DNA methylation of DNMT3A (Jurkowska et al., 2011; Holz-Schietinger et al., 2012). Recently, the crystal structure of DNMT3A-3L has been resolved (Jia et al., 2007a; Guo et al., 2015). It is clear that both homo- and hetero-tetramer dimeric interface involve two pairs of phenylalanine residues from two proteins (DNMT3A: F728, F768 and DNMT3L: F261, F301) stacking on top of each other (Jia et al., 2007b). It is unclear which form of the tetramer is predominant and under which conditions one tetramer conformation is favored over the other in a cell. Although the functional consequences of each tetramer conformation have been addressed, our understanding about this subject remains incomplete. Tetramer conformation seems to modulate DNMT3A localization as overexpression of DNMT3L re-localizes DNMT3A from heterochromatin to euchromatin regions (Jurkowska et al., 2011). The evidence for this hypothesis is still lacking and requires further studies.

3. Epigenetic heterogeneity

Simple view that genetic variations manifest tumor heterogeneity no longer holds. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that genetically uniform cancer cells exhibit inherent variable phenotypes in term of drug responses, proliferative and survival capacity, and metastatic potential (Spencer et al., 2009; Kreso et al., 2013). Epigenetic marks, such as histone modifications and DNA methylation, contribute to tumor heterogeneity and provide cancer cells with great plasticity to adapt to environmental stresses, increasing their probability to survive and expand during and after cancer treatment. The aberrant DNA methylation signatures have been reported to vary among patients (e.g. inter-patient) and within patients (e.g. intra-tumor) during disease progression. Importantly, aberrant DNA methylation is predictive of patients’ survival as well as time to relapse.

The degree of intra- and inter-sample variation in DNA methylation is shown to be associated with disease aggressiveness (De et al., 2013; Chambwe et al., 2014a; Li et al., 2016). Conceptually, inter-patient methylation heterogeneity is quantified by the spread of methylation values normalized to methylation of normal counterparts at a given cytosine loci. An increased in intra-tumor methylation heterogeneity is indirectly quantified by the loss of bimodality (hypomethylated and hypermethylated nodes) (De et al., 2013; Chambwe et al., 2014b). More expensive methods such as whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) (Frommer et al., 1992) or reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) (Meissner, 2005) allow single base-pair resolution of methylation state, enabling a direct measurement of intra-tumor variability. The source of intra-tumor is hypothesized to stem from variability between concordantly un/methylated fragments or discordantly un/methylated CpGs within a single fragment, termed local disordered methylation (Landau et al., 2014). Local disordered methylation state is shown to manifest intra-tumor DNA methylome in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (Landau et al., 2014). Whether this is a general phenomenon across hematological malignancies awaits further studies.

The link between DNA methylation heterogeneity, disease severity and patient outcomes has been documented in both lymphoma and leukemia. By quantifying the difference of DNA methylation patterns between patient samples and normal B cells, it is shown that follicular lymphoma, a less aggressive type of lymphoma, with relatively less intra-tumor and inter-patient methylation difference has better prognosis and longer survival compared to germinal center B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma (GCB DLBCL) and activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma (ABC DLBCL), both of which exhibit higher intra-heterogeneity (De et al., 2013). Importantly, methylation heterogeneity score and international prognosis index (IPI) together produce a significant risk stratification. In a larger cohort of DLBCL patients (n=140), Chambwe et al. (2014a) demonstrated that DNA methylation patterns classify DLBCL into distinct subtypes with clinical and biological relevance. The variance of DNA methylation patterns quantified by mean variance between normal germinal center B cells and patient samples (MVS) can act as an independent indicator of patient survivor outcome: patients with higher MVS exhibits poorer survival outcomes compared to those with lower MVS. These findings altogether strongly suggest that the extent of intra- and inter-heterogeneity of DNA methylation is associated with different subtypes of hematological cancers and disease progression.

In CLL, patients with higher proportion of locally disordered methylation at promoter regions have shorter failure-free survival (Landau et al., 2014). In a cohort of 138 paired acute myeloid leukemia (AML) primary samples taken at diagnosis and relapse, time to relapse is significantly shorter in patients with higher DNA methylation shift than in patients with lower DNA methylation shift. DNA methylation shift was quantified by comparing the difference of epialleles between two conditions: the epigenetic state of four consecutive CpG dinucleotides and each of the 16 possible CpG combinations is defined as an epiallele. These studies, however, do not address whether heterogeneous DNA methylome occurs in the early stages of tumorigenesis.

Perhaps the most interesting finding is the redistribution of epiallele shift at diagnosis and at relapse; epiallele shifts at diagnosis were significantly enriched at enhancer regions but were significantly enriched at intronic and intergenic regions at relapse. Given the substantial transcriptional reprogramming and alternative splicing reprogramming in drug resistance (Paronetto et al., 2016; Wang and Lee, 2018; El Marabti and Younis, 2018; Zhao et al., 2019) and the roles of DNA methylation in alternative splicing and transcription (Lev Maor et al., 2015), it is reasonably to hypothesize that the epiallelic shifts at intronic and intergenic regions potentially have functional impacts on transcriptional and alternative splicing reprogramming in drug resistant tumors.

Given the clinical and biological importance of epigenetic and DNA methylation dynamics within and among tumors, it is essential to understand the mechanism governing of this dynamic. Unlike genomic instability in which structural and numerical chromosomal alteration occurs at higher frequency of certain genomic regions such as fragile sites and terminal TTAGG sequences, it is less clear if DNA methylation heterogeneity in hematological malignancies is an ordered or stochastic process. Evidence in CLL demonstrated that intra-tumor heterogeneity of DNA methylation seems to be a stochastic process in this subtype of leukemia (Landau et al., 2014). Whether this hold true in a larger context of lymphoma is unclear.

Whether epigenetic and genetic diversifications co-modulate tumorigenesis and how they act cooperatively are key questions in understanding tumor evolution. It appears that there might be more than one answer to these questions. In CLL, experimental evidence from WGBS and RRBS of primary patient samples supports a model in which epigenetic alterations accelerate genetic diversification process by providing permissive states of to adapt to environmental stresses (Landau et al., 2014). In AML, in contrast, the epiallele shifting pattern during tumor progression does not follow somatic mutation accumulation patterns (Li et al., 2016). Although this observation suggests that the phenotypes of epigenetic and genetic diversification do not coincide, it does not rule out the possibility that these two phenomena cooperate. Specifically, whether epiallele shifts during AML evolution affect the rate of genetic diversification and therefore increase tumor cell plasticity during treatment remains unanswered.

On the molecular level, how DNA methylation heterogeneity is governed remains unexplored. AICDA (activation-induced cytidine deaminase) is recently identified as a contributor to DNA methylation heterogeneity in germinal center B cells and germinal center-derived lymphomas in both murine models and DLBCL primary samples (Dominguez et al., 2015; Teater et al., 2018). Both transgenic mice overexpressing AICDA and AICDA-high DLBCL patients exhibit greater global inter-patients and intra-tumor heterogeneity than those expressing vector control or AICDA-low tumors, respectively (Teater et al., 2018). Similar to AML, epiallelic alterations are significantly enriched at inter- and intra-genic regions but depleted at promoter regions. It is clear that AICDA is a required factor that allows DNA methylation heterogeneity to occur. More profoundly, experiments with transgenic mice overexpressing AICDA provide evidence that increasing DNA methylation variations can accelerate lymphomagenesis. This is an important experimental evidence substantiating the concept that epigenetic heterogeneity is necessary during early lymphomagenesis.

The recent findings only scratch the surface of DNA methylation heterogeneity during tumor evolution. What are the molecular events inducing and augmenting DNA methylation divergence within a tumor? How is it maintained while undergoing extrinsic stresses? These questions remain under-investigated in hematological malignancies despite their relevance in building the primal understanding of tumor heterogeneity and evolution.

4. DNA methylation in precision oncology

Despite promising combination of Decitabine with immunotherapy in solid cancers, there are several limitations hinder the use of Decitabine in combinatory regimens in hematological malignancies. From clinical perspectives, there are several reasons for this underuse of Decitabine. First, most studies of Decitabine in hematological malignancies focus on how Decitabine is associated with the re-expression of single tumor suppressors (Tamm et al., 2005; Weber et al., 1994; Molavi et al., 2013; Maes et al., 2014). It is crucial to keep in mind that Decitabine affects the global methylome rather than just one single gene. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct comprehensive studies that utilize systematic approaches to understand the broad effects of Decitabine in the treatment of hematological malignancies.

Second, incomplete fundamental understanding of Decitabine-induced toxicity is the major obstacle in utilizing this drug in hematological malignancies. Mechanisms of Decitabine-induced toxicity is becoming increasingly complex. It has been shown in colon cancers that Decitabine induces cell cycle arrest, reactivates endogenous retroviral elements and increases interferon response as well as has an effect on gene body methylation (Yang et al., 2014; Chiappinelli et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016). In hematological malignancies, it is still unclear whether Decitabine-induced toxicity follows similar mechanisms. Mostly importantly, it is not known which of these mechanisms results in the commitment to apoptosis, because most of the aforementioned processes are reversible. A better understanding of Decitabine-induced toxicity is required for the development of rationale-based combination therapies in hematological malignancies.

From a basic science perspective, many longstanding challenges hinder the study of functional impact of DNA methylation and therefore limit the extent of Decitabine toxicity studies. First, most studies rely on the assumed negative association between promoter DNA methylation and transcription rather than directly testing the causal effect of DNA methylation. Second, it is often forgotten that DNA methylation alone is often insufficient to alter transcription. Despite abundant evidence of the interplay between DNA methylation and histone modifications in modulating enhancer activities and repressive state of transcription, such interplay in the context of hematological malignancies is less studied (Baubec et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2015; Rinaldi et al., 2016; Duy et al., 2019; Weinberg et al., 2019). Last but not least, a heavy focus on promoter methylation masks the need to study the function of DNA methylation at intragenic and intergenic regions despite the enrichment of DNA methylation heterogeneity at these regions in primary samples and transgenic mouse models (Li et al., 2016; Teater et al., 2018).

The rationale behind studying these genomic features stems from recent evidence that DNMT3A and DNMT3B preferentially recognizes histone marks H3K36me2 and H3K36me3 at intra-and inter-genic regions, respectively (Baubec et al., 2015; Weinberg et al., 2019). Interestingly, a subset of DLBCL patients harbor deep deletions or amplifications of NSD1/2, the writer of H3K36me2 (CBio Portal). Additionally, 43% of ibrutinib sensitive mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) patients demonstrated deleterious mutations in NSD2 gene but the NSD2 mutations were present in only 13% of ibrutinib resistance MCL patients (Zhang et al., 2019). Concomitantly, the expression of DNMT3A is consistently higher in ibrutinib resistant than ibrutinib sensitive MCL patients. Whether DNMT3A increase in expression is a response to increased NSD2 activity and whether this coincidence has any functional impact require extensive studies.

Methylation at intragenic and intergenic regions have been shown to associate with alternative splicing patterns (Lev Maor et al., 2015). Additionally, AICDA overexpression in a murine model yields an over-presentation of perturbed intragenic cytosine methylation rather than promoter cytosine methylation. It is necessary to carefully examine the phenotypical changes of intergenic cytosine methylation and functional consequences of alternative spliced transcripts after DNA methylation inhibition (Dominguez et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Teater et al., 2018). Given the growing knowledge in dysregulated alternative splicing and transcriptional reprogramming in tumor pathogenicity and resistance (Paronetto et al., 2016; El Marabti and Younis, 2018; Zhao et al., 2019), it is crucial to investigate whether DNA methylation perturbs alternative splicing patterns and whether inhibition of DNA methylation by Decitabine can reverse the perturbed alternative splicing in the context of hematological malignancies.

It has been long realized that only a fraction of cancer cells undergoes apoptosis after therapies such as chemo- or immuno-therapies. Notably, the cytotoxicity is largely restricted to genetically uniform cancer cell populations (Spencer et al., 2009; Kreso et al., 2013). Given the existence of epigenetic intratumor heterogeneity, the question is whether we can overcome non-genetic cell-to-cell variability and achieve better therapeutic effects using epigenetic drugs. Mounting evidence demonstrated that there might be a subset of patients with hematological malignancies who respond better to epigenetic regiments, which manifests the role of epigenetics in precision medicine. Ex vivo culture system of AML patient samples harboring TET2 mutation (TET2mut) exhibits greater response to epigenetic combinations of a LSD1 inhibitor and Decitabine that inhibit leukemic stem cell functions (Duy et al., 2019). The same study demonstrated that AML patient samples with concomitant TET2mut and DNMT3AR882H might not benefit from this combination. Additionally, DLBCL patients with lower SMAD1 expression showed better response to Decitabine treatment than those with higher SMAD1 expression. Whether the level of SMAD1 expression can serve as an independent biomarker for Decitabine response in DLBCL patients require further studies (Clozel et al., 2013; Stelling et al., 2019).

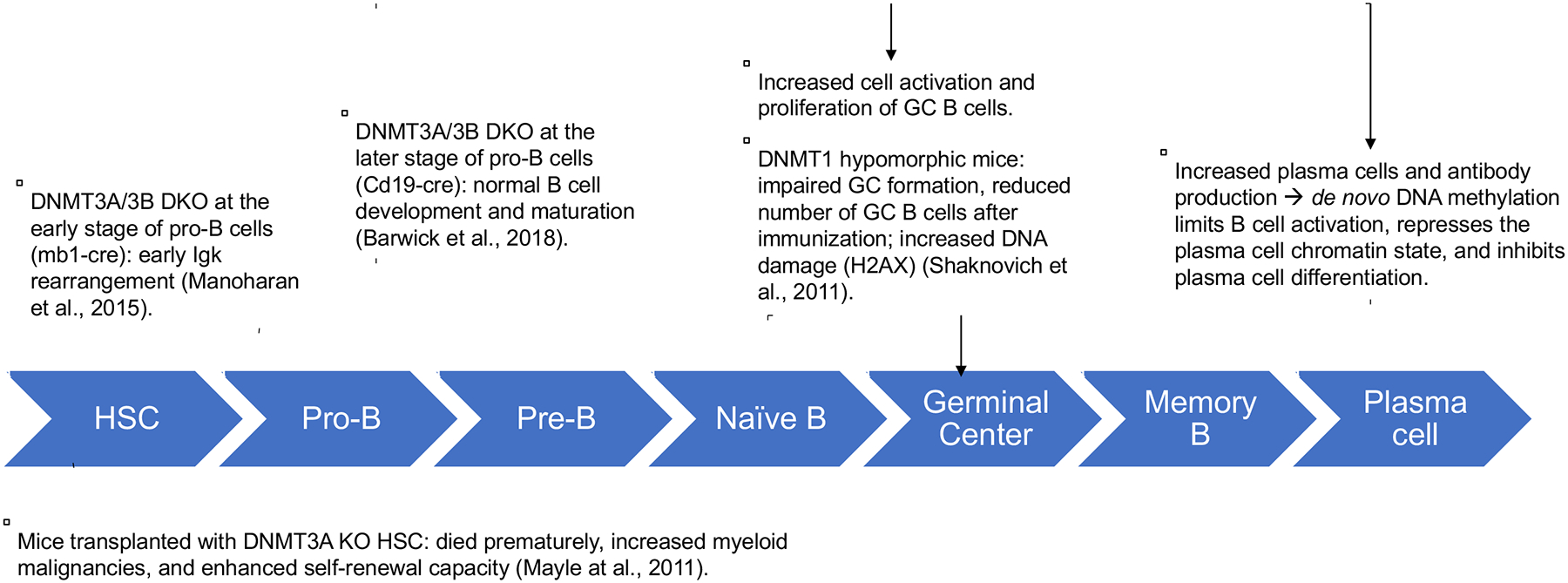

5. The function of DNMTs during normal B cell development

To gain a deeper insight into the roles of DNMTs in hematological malignancies, it is important to understand their functions during normal hematopoiesis and T-/B-cell development and differentiation. Much of the current knowledge about this subject came from mouse studies, although a comprehensive picture is far from completion (Fig. 2). DNMT3A KO at the HSC stage confers the preleukemic phenotype with increased self-renewal capacity (Koya et al., 2016). This concept is further corroborated by findings that DNMT3A mutations are more prevalent in secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) than in primary AML and that these mutations can be traced back to pre-existing clones during the progression of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) (Fried et al., 2012; Wakita et al., 2013). At the early pro-B cell stage (mb1 expressing cells), DNMT3A/3B DKO results in early IgK rearrangement, affecting proximal Vk genes in mice (Manoharan et al., 2015). DNMT3A/3B DKO at the later pro-B cell stage (Cd19 expressing cells), however, has not affected B cell development and maturation but increased cell activation and proliferation of GC B cells and plasma cell population after immunization (Barwick et al., 2018). Collectively, these animal studies suggest that DNMT3A is required for HSC differentiation whereas DNMT3A and 3B together prevent the immature rearrangement at the early pre-B cell stage and control plasmacytic differentiation. These findings highlight the temporal dynamics of DNMT3A and 3B activities during the HSC and B cell development.

Fig. 2. The role of DNMTs in normal B cell development and differentiation.

HSC: hematopoietic stem cells.

DNMT1 regulates B cell maturation. DNMT1 expression is required for complete differentiation of naive B cells to GC B cells (Shaknovich et al., 2011). DNMT1 is up-regulated in GC B cells compared to naive B cells (Shaknovich et al., 2011; Lai et al., 2013). Mice with hypomorphic DNMT1 exhibit a deficiency in GC formation and an increase in DNA damage responses (Shaknovich et al., 2011). GC cells show higher methylation heterogeneity than resting naive B cells. Altogether, these observations substantiate the essential role of DNMT1 in GC formation. How exactly DNMT1 modulates this process remains to be investigated.

6. The role of DNMTs in hematological malignancies

6.1. Acute myeloid leukemia

Among three DNMTs, DNMT3A has been extensively studied in the context of hematopoietic malignancies. DNMT3A is frequently mutated, mostly in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (Table 1). AML is a hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell malignancy that is generally categorized as having normal karyotype or abnormal karyotype. Normal karyotype AML patients show a high frequency of mutations in genes involved in DNA methylation. Among this group, 30%−35% are presented with DNMT3A mutations with the most frequent being the heterozygous R882H mutation, suggesting that altered DNA methylation may play an important role in the pathogenesis of this group of patients (Russler-Germain et al., 2014). These mutations can be found in pre-leukemic clones in patients including those who later develop secondary AML from other myeloid diseases such as MDS (Ley et al., 2010; Ding et al., 2012; Fried et al., 2012; Wakita et al., 2013). Hotspot mutation arginine 882 to histidine (R882H), which is located at outside of the MTase domain, is predominantly found in de novo AML. Interestingly, mutations in secondary AML are mostly found within the MTase domain. DNMT3A mutations as well as the consequences of these mutations with regard to patient prognosis and therapeutic implications have been well documented and reviewed elsewhere (Yang et al., 2015; Brunetti et al., 2017). Briefly, in a cohort of 511 cases (AML=194, MDS=115, and others), the majority of DNMT3A mutated cases are AML (70/194; 36.1%), followed by T-ALL (17/99; 17.2%) and MDS (15/115;13%). Intriguingly, DNMT3A mutations did not affect the prognosis of this AML cohort. (Roller et al., 2013).

Table 1: Mutations mapped to functional domains of DNMT3A.

Based on the COSMIC database (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), 96% of all mutations of DNMT3A are missence mutations and only 5% of these mutations are nonsense substitutions. Total number of cases is 1957. Mutations in the PWWD and ADD-linker domains of DNMT3A are less frequent than the MTase and C-terminus domains. The MTase domain has the most diverse mutation profile. Mutation S714C causes dramatic losses of genome-wide methylation (Sandoval et al., 2019). C-terminus region outside of the Mtase domain harbors the R882H and R882C, the most frequent mutations, suggesting that impaired dimerization of DNMT3A provides cells with growth advantage. Disease abbreviations: AML: acute myeloid leukemia; CML: chronic myeloid leukemia; ALL: acute lymphocytic leukemia; MDS: myelodysplastic syndromes; PV: Polycythemia vera; CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; MCL: mantle cell lymphoma; MM: multiple myeloma; AITL: angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; PTCL: peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

| Domain | Mutation | Type of substitution mutations | Frequency in 1957 cases | Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWWD | R320* | Nonsense | 6 | AML (5), ALL (1) |

| L344P | Missense | 4 | AML (2) Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) (2) | |

| W313* | Nonsense | 3 | DLBCL, MDS, AML | |

| W330* | Nonsense | 3 | HL (2), AML (1) | |

| ADD-linker | G543C | Missense | 23 | MDS (1), AML (22) |

| G543V | Missense | 3 | AML | |

| G543A | Missense | 3 | AML | |

| L547H | Missense | 5 | AML/AML-MDS | |

| G550R | Missense | 7 | AML (5), Myelofibrosis (1), multiple myeloma (MM) (1) | |

| MTase | R635Q | Missense | 3 | AML |

| R635W | Missense | 16 | DLBCL (1); AML (14); MDS (1) | |

| V690D | Missense | 3 | DLBCL; peripheral T cell lymphoma (PTCL); AML | |

| G699S | Missense | 3 | AML (1); MDS (2) | |

| G699D | Missense | 4 | CLL-AML (1); Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (AITL) (1); AML (2) | |

| I705T | Missense | 5 | Polycythaemia vera (PV) (1); CLL (1); AML (3) | |

| C710S | Missense | 4 | DLBCL (2). AML-MDS (2) | |

| S714C | Missense | 23 | CML (1/), AITL (1), MDS (1), AML | |

| R729W | Missense | 13 | DLBCL (5), AITL (1), PTCL (1), AML (6) | |

| F732S | Missense | 3 | Essential thrombocythaemia (2); MDS | |

| Y735S | Missense | 3 | AML | |

| Y735C | Missense | 9 | DLBCL (1), MDS (1), MM (1), AML (6) | |

| R736H | Missense | 16 | AITL (4), MDS (1), PTCL (1), AML (10) | |

| R736C | Missense | 17 | AITL (2), DLBCL (2), MDS (1), MM (1), AML (11) | |

| R749C | Missense | 10 | MCL (2), PV (1) | |

| S770L | Missense | 6 | MDS (1), myelofibrosis (1), AML | |

| S770W | Missense | 5 | AML (2), adult-T cell leukemia/lymphoma, MDS, myeloma | |

| R771Q | Missense | 4 | Mast cell neoplasm (1), AML | |

| R771* | Nonsense | 11 | MCL (2), AITL (1), MDS (2), AML (6) | |

| I780T | 7 | AML (3), AITL (1). DLBCL (2), Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (1) | ||

| C-terminus | R882H | Missense | 852 | AML (majority), MDS (23), myeloma (2), PTCL (3), myelofibrosis (3), Essential thrombocythaemia (6), DLBCL (1), CML (10), AITL (6) |

| R882C | Missense | 355 | AML (majority), PV (6), Myelofibrosis (1), MDS (10), AML-MDS associated (3), CML (1), DLBCL (2), ALL (2), AITL(7), PTCL (1) | |

| P904L | Missense | 16 | MDS (5), AML (10), carcinoma (1) | |

| M880V | Missense | 7 | AML (4), PV (2), MDS (1) | |

| W893S | Missense | 12 | AML (10), Myelofibrosis (1), MDS (1) |

According to the current COSMIC database (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), 852 out of a total of 1957 patients with hematopoietic malignancies harbor the DNMT3A R882H mutation. This mutation was found in approximately 30% of normal karyotype AML. Patients with heterozygous DNMT3A R882H do not show genome-wide hypomethylation but distinct loss- and gain- methylation at different loci throughout the genome. The effect of this mutation has been postulated to affect the oligomerization state of DNMT3A and therefore creates aberrant methylation patterns (Holz-Schietinger et al., 2011). At the molecular level, DNMT3A R882H confers an 80% reduction in the methyltransferase activity compared to the wild-type counterpart (WT) (Russler-Germain et al., 2014). Two seminal papers have provided evidence that this mutant impairs DNMT3A dimer interface and abolishes homotetramer formation (Holz-Schietinger et al., 2012; Russler-Germain et al., 2014). Beside the homotetramer complex, DNMT3A can form a heterotetramer with DNMT3L. DNMT3L is expressed at high levels during the early development but at very low levels in normal karyotype AML (Hata, 2002; Webster et al., 2005; Russler-Germain et al., 2014). It is, however, not clear whether DNMT3L can be re-expressed at certain time points during cancer cell evolution and whether the DNMT3A-3L heterotetramer formation is affected in patients with heterozygous DNMT3A R882H. This is an interesting question because DNMT3A-3L heterotetramer has relatively higher processive catalysis than the homotetramer of DNMT3A and that heterozygous DNMT3A R882H is shown to impair DNMT3A-3A homotetramer (Holz-Schietinger et al., 2011; Russler-Germain et al., 2014). Altogether, the current literature supports that DNMT3A acts as a tumor suppressor in the context of leukemia.

6.2. T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is an aggressive cancer of transformed T-cell lymphoblastic precursors. T-ALL is associated with activation of oncogenic transcription factor c-MYC (Poole et al., 2017). All three active DNMTs are found to be upregulated in T-ALL clinical specimens. Chromatin immunoprecipitation of MYC in T-ALL cell lines showed that MYC directly binds to DNMT1 and DNMT3B promoter regions. Knockdown of c-MYC resulted in decreased DNMT1 and DNMT3B mRNA. These findings suggest that c-MYC directly regulates DNMT1 and DNMT3B expression. Knockdown of DNMT3B in mouse T-ALL (EμSRα-tTA;tet-o-MYC) led to reduced cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest and upregulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors such as p15 and p16 (Poole et al., 2017). This finding suggests DNMT3B as a tumor suppressor in the context of T-ALL. DNMT3A is frequently mutated in a cohort of 90 T-ALL patients (17.8%) and is associated with a poor prognosis (Grossmann et al., 2013). In another cohort of 99 T-ALL cases, 17.2% of these patients harbor DNMT3A mutations in which the majority of the patients have a single mutation (89%) and only 12% have double mutations. Although most of the mutations are heterozygous, there are 17.6% of the affected patients who have homozygous mutations. DNMT3A mutations are associated with worse overall survival (OS) compared to that of patients with wild-type DNMT3A (2-year OS: 35.2 vs. 67.9%; median OS: 16.6 months vs. not reached; P=0.013) (Roller et al., 2013)

6.3. Hodgkin lymphoma

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is an atypical GC-derived B-cell lymphoma that has lost its B cell identity (Küppers, 2009). Methylation array analysis of HL cell lines reveals that DNA hypermethylation accounts for the silencing of B-cell specific genes (Ammerpohl et al., 2012). Although studies of DNMTs in HL lymphoma is lacking, some clues come from studies of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infected GC B cells. EBV-infected GC B cells exhibit significant enrichment of differentially expressed genes that are also differentially expressed in HL (Leonard et al., 2011). Therefore, EBV-infected GC B cells may serve as a useful model to study HL in vitro. Although the regulation of DNMT expression in EBV-infected GC B cells is not yet elucidated, it is shown that EBV infection is associated with decreased DNMT1 and DNMT3B but increased DNMT3A protein levels. EBV infected GC B cells remain latent among the memory B cell populations. The repression of viral gene expressions is in part driven by the upregulation of DNMT3A (Leonard et al., 2011). DNMT3A binds to and methylate the viral promoter Wp, the first promoter to be activated during in vitro transformation. Wp can initiate the transcription of EBV nuclear antigens (EBNA) and upregulation of latent membrane proteins. To remain latent, Wp transcription has to be repressed. Altogether, direct DNMT3A binding and increased promoter methylation at least in part account for the silencing of Wp (Leonard et al., 2011). Additionally, DNMT3A mutations are found in 12.68% of HL patients (n=79), including a nonsense substitution (L859*), missense substitutions clustering in the PWWD domain and the C-terminus, outside of the MTase domain, based on the COSMIC database.

6.4. Burkitt Lymphoma

DNMT1 and DNMT3B are overexpressed in Burkitt Lymphoma (BL) patients (69% and 86%, respectively) partly due to the downregulation of miR-29 (Robaina et al., 2015). Another study has shown that MYC directly binds to the DNMT1 and DNMT3B promoter, resulting in their increased transcription in a human BL model (P493–6) (Poole et al., 2017). Knockdown of DNMT3B decreased cell proliferation, suggesting functional importance of DNMT3B in BL (Poole et al., 2017).

6.5. MYC-induced T-cell lymphoma

Studies using the Eμ-myc transgenic mouse model have demonstrated that DNMT3A supports tumor cell growth during tumor initiation and maintenance (Haney et al., 2016). In T-ALL, DNMT3A depletion reduced tumorigenesis in the Eμ myc transgenic mice. However, promoter and gene body methylation of re-expressed genes after DNMT3A depletion was not substantially altered compared to control mice, indicating that DNMT3A represses these genes in a methylation-independent manner. Importantly, DNMT3B was among the re-expressed genes after DNMT3A depletion and re-expression of either wild-type or catalytically inactive DNMT3A downregulates DNMT3B expression. DNMT3B inactivation in DNMT3A-deficient mice accelerated lymphomagenesis, implicating that DNMT3B upregulation is a relevant molecular event in preventing lymphomagenesis in the DNMT3A-depleted mice. This study is among the first to demonstrate the oncogenic role of DNMT3A in hematopoietic malignancies through methylation-independent repression of DNMT3B.

6.6. Diffuse large B-cell Lymphoma

Diffuse large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive and the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, accounting for 30%−40% of newly diagnosed lymphoma cases (Xie et al., 2015). Gene expression profiling has stratified two distinct molecular signatures termed activated B-cell-like (ABC) and germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) DLBCL (Alizadeh et al., 2000; Lenz and Staudt, 2010; Rui et al., 2011). In a cohort of 81 newly diagnosed DLBCL patients, immunohistochemical analysis showed that all three active DNMTs are overexpressed in DLBCL. Expression of DNMT1 and DNMT3B was significantly associated with advanced clinical stages and worse responses to chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy (Amara et al., 2010). Overexpression of DNMT3B was significantly associated with shorter overall survival and progression free survival in cases based on available clinical outcome data (n=40). It was later shown that treatment with prolonged, low-doses of Decitabine (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, DAC), a pan-inhibitor of DNMTs, sensitized chemoresistant DLBCL cell lines to doxorubicin, a commonly used chemo-drug in several first-line treatments of DLBCL (Jones et al., 1979; Gams et al., 1985; Bishop et al., 1987; Gordon et al., 1992). SMAD1 promoter was found to be hypermethylated whose expression was increased after Decitabine treatment. Inhibition of SMAD1 expression abolished chemosensitization, indicating that methylation-dependent silencing of SMAD1 contributes to the chemoresistant phenotype in DLBCL. More importantly, in a cohort of 12 DLBCL older patients with high-risk disease, sequential administration of DNMT inhibitors followed by R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) was found to be safe and resulted in a high rate of complete clinical response and was associated with re-expression of SMAD1 (Clozel et al., 2013). Taken together, these observations suggest that DNMTs, especially DNMT1 and DNMT3B, might be involved in DLBCL tumor survival and resistant to therapy. A comprehensive characterization of target genes of DNMTs through both methylation-dependent and methylation-independent mechanisms are needed to better design epigenetic based therapies for DLBCL treatment.

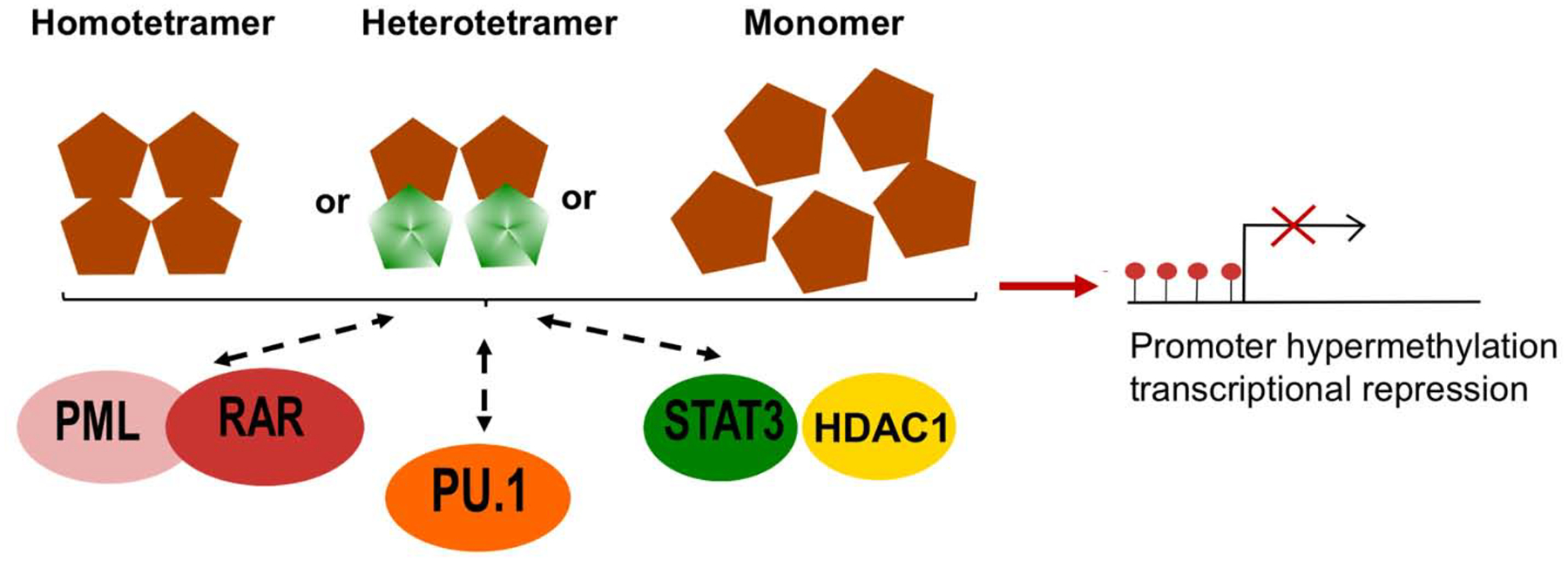

7. Instructive DNA methylation at the promoter region of tumor suppressor genes in hematological malignancies

Genome-wide DNA methylation studies in various blood cancers have demonstrated that the genome of malignant cells is globally hypomethylated. Paradoxically, there are specific DNA regions at which islands of CpG dinucleotides are hypermethylated, leading to the aberrant methylation and expression of these genes. The overexpression of DNMTs alone cannot explain this seemingly instructive methylation. Studies in the past decade have provided some clues about how this aberrant methylation may occur. As illustrated in Figure 3, one molecular mechanism emerging from these studies is the ability of the DNMT family to interact with or recruit other epigenetic enzymes and transcription factors to facilitate different chromatin states, although the chronological sequence of these interactions/recruitments is not completely elucidated.

Fig. 3. Model of instructive DNA methylation by DNMT1 and DNMT3A at promoter regions of tumor suppressor genes.

Whether DNMT3A interacts with these transcription factors/cofactors as a homo/heterotetramer or a monomer remains unknown. Brown diamonds: DNMT3A; green diamonds: DNMT3L.

The longstanding paradigm is that the early stage of carcinogenesis is the accumulation of mutations. Di Croce et al. (2002) reported the first mechanistic evidence linking genetic and epigenetic changes in leukemogenesis, suggesting that the aberrant methylation contributes to the early stages of tumorigenesis. The leukemia promoting PML-RAR fusion protein is an oncogenic transcription factor in acute promyelocytic leukemia. PML-RAR fusion protein recruits DNMT1 and DNMT3A to its target promoter such as retinol acid receptor 2 (RARb2) to induce methylation and gene silencing, contributing to its oncogenic potential (Di Croce, 2002). PML-RAR fusion protein alters subcellular localization of DNMT1 and DNMT 3A. In cells with wild type PML, DNMT1 and DNMT3A diffuse throughout the nucleus. However, their physical interactions with the PML-RAR fusion protein redistribute them to the microspeckles as shown by immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence imaging. In 2005, Zhang and colleagues revealed that DNMT1 interacts with STAT3 and HDAC1 in primary cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) to induce promoter hypermethylation and gene silencing of SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase (Zhang et al., 2005). The authors demonstrated that DNMT1, STAT3 and HDAC1 form a complex in CTCL cell lines and that all three proteins directly bind to the SHP-1 promoter. Depletion of DNMT1 or STAT3 using anti-sense oligonucleotides and small-interfering RNA reduced SHP-1 promoter methylation, leading to SHP-1 re-expression.

Suzuki et al. (2006) found that DNMT3A and 3B interact with PU.1 in vivo using murine hematopoietic progenitor cells. The authors further provided direct evidence of the physical interaction between the ATRX domains of DNMT3A/3B and the ETS domain of PU.1. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay confirmed that DNMT3A/3B colocalize with PU.1 in HEK293T cells. The tumor suppressor p16 promoter region is methylated by PU.1-mediated DNMT3A/3B binding in NIH3T3 cells. Despite strong biochemical evidence, this study did not assess whether p16 is re-expressed after disrupting interaction of PU.1 and DNMT3A/3B.

The above studies suggest a scenario in which DNMTs are recruited to a specific CpG locus by physical interactions with different oncogenic transcription factors or cofactors. These hypermethylation regions are subsequently read by methylation binding proteins (MBP), leading to the recruitment of other silencing complexes such as HDACs and polycome suppressor complex to induce a stably silencing chromatin state. It is unclear, however, what mediates the aberrant interactions between DNMTs and these oncogenic transcription factors/cofactors.

8. Targeting DNMTs in hematological malignancies

8.1. Clinical trials

Currently, there are more than 249 clinical trials using Decitabine as a single drug or in combination with chemotherapy, epigenetic drugs, or immunotherapy in AML and/or MDS (https://clinicaltrials.gov). On the other hand, there are only 30 trials using Decitabine in lymphoma, some of which are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2:

Summary of clinical trials using Decitabine for the treatment of lymphoma patients.

| Disease | Name | Status | Phase | Number of participants | Intervention/Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLBCL | NCT04025593 | Active, recruiting | II | 128 | RCHOP, Ibrutinib, Lenalidomide, chidamide, Decitabine |

| Advanced malignancies for which all standard therapies have failed including DLBCL, AML, and CML | NCT00002980 | Completed | I | NA | Decitabine |

| Relapsed or Refractory Primary Mediastinal Large B-cell Lymphoma | NCT03346642 | Recruiting | I/II | 30 | GVD chemotherapy (Gemcitabine, Vinorelbine and Doxorubicine) PD-1 Antibody (SHR-1210) |

| Untreated Peripheral T cell lymphoma (PTCL) | NCT03553537 | Not yet recruiting | III | 100 | Decitabine plus CHOP |

| PTCL, Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma | NCT03240211 | recruiting | I | 42 | Pembrolizumab, Pralatrexate Drug, Decitabine |

| Recurrent Adult Burkitt Lymphoma, Recurrent Adult Diffuse Large Cell Lymphoma, Recurrent Mantle Cell Lymphoma | NCT00109824 | completed | I | 42 | valproic acid, Decitabine |

8.2. Mechanisms of drug actions:

Decitabine is a DNMT pan-inhibitor and acts as an analog of pyrimidine nucleoside cytidine. Decitabine incorporates into DNA and irreversibly forms a stable complex with DNMTs, leading to rapid loss of methylated cytosine (Christman, 2002). The mechanisms of drug actions have been extensively studied and reviewed (Christman, 2002; Momparler, 2005). Briefly, the toxicity of Decitabine can be characterized into two main categories: i) reactivation of methylation-mediated silenced tumor suppressors and ii) induction of DNA-damage leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Palii et al., 2008; Maes et al., 2014; Chiappinelli et al., 2015; Roulois et al., 2015; Swerev et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2018; Caiado et al., 2019).

8.2.1. Reactivation of methylation-mediated silenced tumor suppressors

In AML, co-treatment of chemotherapeutic drugs and low doses of Decitabine suppresses chemoresistance phenotype by repressing the pre-determined chemoresistant clones that exhibit stemness properties both in xenograft models and primary AML patient samples (Caiado et al., 2019). Mechanistically, Decitabine reactivates a set of key genes including lineage-specific and late-differentiation transcription factors to control myeloid maturation (Negrotto et al., 2012). Additional studies revealed that Decitabine treatment results in reactivation of p21WAF1, dependent of its promoter methylation status by upregulating p73, an upstream regulator of p21 whose promoter is hypermethylated in AML cells (Tamm et al., 2005; Scott et al., 2006). Decitabine also inhibits JAK/STAT3 signaling due to increased SOCS3 expression in AML cells (Zhu et al., 2015).

8.2.2. DNA-damage induction by Decitabine

A plethora of evidence suggests that DNMT1 is involved in the DNA damage response (Eads et al., 2002; Palii et al., 2008; Ha et al., 2011; Shaknovich et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012). Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)-dependent formation of phosphorylated H2AX (γ-H2AX) was observed after Decitabine treatment and DNMT1 colocalized with γ-H2AX foci. DNMT1 interacts with checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1) and mediates the DNA damage response partly by alternating CHK1 subcellular localization (Palii et al., 2008). In multiple myeloma, a plasma cell malignancy, formation of γ-H2AX foci was significantly enhanced after Decitabine treatment, followed by G0/G1 and/or G2/M arrests and caspase-mediated apoptosis (Maes et al., 2014). It should be noted, however, that most mechanistic studies were based on normal B cells and colon cancer cells. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of Decitabine in hematological malignancies.

An interesting candidate that can unify two major mechanisms of Decitabine-mediated toxicity is GADD45a (growth arrest and DNA damage protein 45A). GADD45a is a nuclear protein that is involved in both DNA repair and active DNA demethylation (Carrier et al., 1999; Hollander and Fornace, 2002; Barreto et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2012). GADD45a mediates demethylation in both DNA-repair dependent and independent pathways. In DNA-repair independent pathway, GADD45a requires the DNA repair endonuclease XPG to excise methylated DNA (Barreto et al., 2007). Additional evidence suggests that upon DNA damage, GADD45a interacts with the catalytic site of DNMT1 and inhibits its activity and thereby leaves the repaired DNA hemimethylated during homologous recombination repair after DNA damage (Lee et al., 2012). Recently, GADD45a was found to act as a reader of R-loop, recruiting TET1 to the oxidized methylated promoter CpG islands (Arab et al., 2019). Given that GADD45a is lowly expressed in the majority of leukemic and lymphoblastic cell lines, it is possible that GADD45a is reactivated in response to Decitabine-mediated DNA damage and in turn facilitates the active demethylation by recruiting TET and/or inhibiting DNMT1 activity.

8.2.3. Decitabine enhances the efficacy of immunotherapies

As shown in Table 2, there are several clinical trials combining Decitabine and immunotherapy drugs including anti-PD1 antibodies. Mechanistically, Decitabine is shown to enhance immunogenicity of cancer cells, establishing a subfield termed epigenetic therapy in immune-oncology (Jones et al., 2019). In colon cancers, Decitabine treatment resulted in reactivation of endogenous retrovirus (ERV) and subsequently type I/II interferon responses (Chiappinelli et al., 2015; Roulois et al., 2015). Decitabine rapidly and robustly induced reactivation of cancer-testis antigens (CTA) in melanoma, AML, and transitional cell carcinoma (Weber et al., 1994; Qiu et al., 2010). In MDS-derived cell lines and primary tumor cells, relatively low basal expression of MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3, SP17 (CTA genes) was significantly improved after Decitabine treatment. CTA-specific T lymphocyte recognition and function was significantly enhanced after Decitabine treatment (Zhang et al., 2017). Both ERV and CTA proteins can be presented on the cell surface and therefore increase immune recognitions by other immune cells. These observations provide mechanistic rationales to use Decitabine as an epigenetic-priming reagent in immunotherapy (Jones et al., 2019).

9. Concluding remarks

The current literature demonstrates that the role of DNMTs in hematological malignancies are diverse and context dependent. Most studies suggest that DNMT1 and DNMT3B support tumor cell growth in lymphoma and T-ALL whereas DNMT3A is a tumor suppressor in AML with a high frequency of missense mutations. Although the methylome of most blood cancers exhibits global hypomethylation, multiple specific loci become hypermethylated. This instructive methylation in part can be explained by the aberrant interaction of DNMT1 and DNMT3A with other oncogenic transcription factors, directing DNMTs to specific loci. However, it is still an open question whether DNMT3A exists as monomer, homo- or hetero-tetramer in these interactions. The mechanisms that govern these interactions await further studies.

Clinically, inhibition of DNMTs by Decitabine results in tumor regression. Decitabine has been used at low doses in combination with other regimens including chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Several questions remain including which DNMT is the major target, and whether Decitabine-mediated toxicity is primarily due to induction of DNA damage, reactivation of tumor suppressor genes, or increased immunogenicity.

In conclusion, there is a gap in our knowledge about DNMT functions in the context of hematological malignancies. A deeper understanding of specific targets of DNMTs and the anti-tumor mechanisms of DNMT inhibitors will provide the mechanistic rationale for combinatory regimens in the treatment of hematological malignancies.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (NIH/NCI) grant R01 CA187299 (L.R.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C, Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, Boldrick JC, Sabet H, Tran T, Yu X, Powell JI, Yang L, Marti GE, Moore T, Hudson J, Lu L, Lewis DB, Tibshirani R, Sherlock G, Chan WC, Greiner TC, Weisenburger DD, Armitage JO, Warnke R, Levy R, Wilson W, Grever MR, Byrd JC, Botstein D, Brown PO, Staudt LM, 2000. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature 403, 503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amara K, Ziadi S, Hachana M, Soltani N, Korbi S, Trimeche M, 2010. DNA methyltransferase DNMT3b protein overexpression as a prognostic factor in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Cancer Sci. 101, 1722–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerpohl O, Haake A, Pellissery S, Giefing M, Richter J, Balint B, Kulis M, Le J, Bibikova M, Drexler HG, Seifert M, Shaknovic R, Korn B, Küppers R, Martín-Subero JI, Siebert R, 2012. Array-based DNA methylation analysis in classical Hodgkin lymphoma reveals new insights into the mechanisms underlying silencing of B cell-specific genes. Leukemia 26, 185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arab K, Karaulanov E, Musheev M, Trnka P, Schäfer A, Grummt I, Niehrs C, 2019. GADD45A binds R-loops and recruits TET1 to CpG island promoters. Nat. Genet 51, 217–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery OT, MacLeod CM, McCarty M, 1995. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types. Induction of transformation by a desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated from Pneumococcus type III. 1944. Mol. Med 1, 344–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto G, Schäfer A, Marhold J, Stach D, Swaminathan SK, Handa V, Döderlein G, Maltry N, Wu W, Lyko F, Niehrs C, 2007. Gadd45a promotes epigenetic gene activation by repair-mediated DNA demethylation. Nature 445, 671–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barwick BG, Scharer CD, Martinez RJ, Price MJ, Wein AN, Haines RR, Bally APR, Kohlmeier JE, Boss JM, 2018. B cell activation and plasma cell differentiation are inhibited by de novo DNA methylation. Nat. Commun 9, 1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baubec T, Colombo DF, Wirbelauer C, Schmidt J, Burger L, Krebs AR, Akalin A, Schübeler D, 2015. Genomic profiling of DNA methyltransferases reveals a role for DNMT3B in genic methylation. Nature 520, 243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestor T, Laudano A, Mattaliano R, Ingram V, 1988. Cloning and sequencing of a cDNA encoding DNA methyltransferase of mouse cells: the carboxyl-terminal domain of the mammalian enzymes is related to bacterial restriction methyltransferases. J. Mol. Biol 203, 971–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestor TH, 1992. Activation of mammalian DNA methyltransferase by cleavage of a Zn binding regulatory domain. EMBO J. 11, 2611–2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestor TH, Ingram VM, 1983. Two DNA methyltransferases from murine erythroleukemia cells: purification, sequence specificity, and mode of interaction with DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 80, 5559–5563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestor TH, Ingram VM, 1985. Growth-dependent expression of multiple species of DNA methyltransferase in murine erythroleukemia cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 82, 2674–2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop JF, Wiernik PH, Wesley MN, Kaplan RS, Diggs CH, Barcos MP, Sutherland JC, 1987. A randomized trial of high dose cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone plus or minus doxorubicin (CVP versus CAVP) with long-term follow-up in advanced non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leukemia 1, 508–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti L, Gundry MC, Goodell MA, 2017. DNMT3A in Leukemia. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 7, a030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiado F, Maia-Silva D, Jardim C, Schmolka N, Carvalho T, Reforço C, Faria R, Kolundzija B, Simões AE, Baubec T, Vakoc CR, da Silva MG, Manz MG, Schumacher TN, Norell H, Silva-Santos B, 2019. Lineage tracing of acute myeloid leukemia reveals the impact of hypomethylating agents on chemoresistance selection. Nat. Commun 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier F, Georgel PT, Pourquier P, Blake M, Kontny HU, Antinore MJ, Gariboldi M, Myers TG, Weinstein JN, Pommier Y, Fornace AJ, 1999. Gadd45, a p53-responsive stress protein, modifies DNA accessibility on damaged chromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol 19, 1673–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambwe N, Kormaksson M, Geng H, De S, Michor F, Johnson NA, Morin RD, Scott DW, Godley LA, Gascoyne RD, Melnick A, Campagne F, Shaknovich R, 2014a. Variability in DNA methylation defines novel epigenetic subgroups of DLBCL associated with different clinical outcomes. Blood 123, 1699–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambwe N, Kormaksson M, Geng H, De S, Michor F, Johnson NA, Morin RD, Scott DW, Godley LA, Gascoyne RD, Melnick A, Campagne F, Shaknovich R, 2014b. Variability in DNA methylation defines novel epigenetic subgroups of DLBCL associated with different clinical outcomes. Blood 123, 1699–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappinelli KB, Strissel PL, Desrichard A, Li H, Henke C, Akman B, Hein A, Rote NS, Cope LM, Snyder A, Makarov V, Buhu S, Slamon DJ, Wolchok JD, Pardoll DM, Beckmann MW, Zahnow CA, Merghoub T, Chan TA, Baylin SB, Strick R, 2015. Inhibiting DNA methylation causes an interferon response in cancer via dsRNA including endogenous retroviruses. Cell 162, 974–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christman JK, 2002. 5-Azacytidine and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine as inhibitors of DNA methylation: mechanistic studies and their implications for cancer therapy. Oncogene 21, 5483–5495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clozel T, Yang S, Elstrom RL, Tam W, Martin P, Kormaksson M, Banerjee S, Vasanthakumar A, Culjkovic B, Scott DW, Wyman S, Leser M, Shaknovich R, Chadburn A, Tabbo F, Godley LA, Gascoyne RD, Borden KL, Inghirami G, Leonard JP, Melnick A, Cerchietti L, 2013. Mechanism-based epigenetic chemosensitization therapy of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Discov. 3, 1002–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De S, Shaknovich R, Riester M, Elemento O, Geng H, Kormaksson M, Jiang Y, Woolcock B, Johnson N, Polo JM, Cerchietti L, Gascoyne RD, Melnick A, Michor F, 2013. Aberration in DNA methylation in B-cell lymphomas has a complex origin and increases with disease severity. PLoS Genet. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Croce L, 2002. Methyltransferase recruitment and DNA hypermethylation of target promoters by an oncogenic transcription factor. Science 295, 1079–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Ley TJ, Larson DE, Miller CA, Koboldt DC, Welch JS, Ritchey JK, Young MA, Lamprecht T, McLellan MD, McMichael JF, Wallis JW, Lu C, Shen D, Harris CC, Dooling DJ, Fulton RS, Fulton LL, Chen K, Schmidt H, Kalicki-Veizer J, Magrini VJ, Cook L, McGrath SD, Vickery TL, Wendl MC, Heath S, Watson MA, Link DC, Tomasson MH, Shannon WD, Payton JE, Kulkarni S, Westervelt P, Walter MJ, Graubert TA, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, DiPersio JF, 2012. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature 481, 506–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez PM, Teater M, Chambwe N, Kormaksson M, Redmond D, Ishii J, Vuong B, Chaudhuri J, Melnick A, Vasanthakumar A, Godley LA, Papavasiliou FN, Elemento O, Shaknovich R, 2015. DNA methylation dynamics of germinal center B cells are mediated by AID. Cell Rep. 12, 2086–2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong A, 2001. Structure of human DNMT2, an enigmatic DNA methyltransferase homolog that displays denaturant-resistant binding to DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duy C, Teater M, Garrett-Bakelman FE, Lee TC, Meydan C, Glass JL, Li M, Hellmuth JC, Mohammad HP, Smitheman KN, Shih AH, Abdel-Wahab O, Tallman MS, Guzman ML, Muench D, Grimes HL, Roboz GJ, Kruger RG, Creasy CL, Paietta EM, Levine RL, Carroll M, Melnick AM, 2019. Rational targeting of cooperating layers of the epigenome yields enhanced therapeutic efficacy against AML. Cancer Discov. 9, 872–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eads CA, Nickel AE, Laird PW, 2002. Complete genetic suppression of polyp formation and reduction of CpG-island hypermethylation in ApcMin/+Dnmt1-hypomorphic mice 5 62, 1296–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JR, Yarychkivska O, Boulard M, Bestor TH, 2017. DNA methylation and DNA methyltransferases. Epigenet. Chromatin 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Marabti E, Younis I, 2018. The Cancer Spliceome: Reprograming of Alternative Splicing in Cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried I, Bodner C, Pichler MM, Lind K, Beham-Schmid C, Quehenberger F, Sperr WR, Linkesch W, Sill H, Wolfler A, 2012. Frequency, onset and clinical impact of somatic DNMT3A mutations in therapy-related and secondary acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 97, 246–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommer M, McDonald LE, Millar DS, Collis CM, Watt F, Grigg GW, Molloy PL, Paul CL, 1992. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 89, 1827–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuks F, Burgers WA, Brehm A, Hughes-Davies L, Kouzarides T, 2000. DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 associates with histone deacetylase activity. Nat. Genet 24, 88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuks F, 2001. Dnmt3a binds deacetylases and is recruited by a sequence-specific repressor to silence transcription. EMBO J. 20, 2536–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gams RA, Rainey M, Dandy M, Bartolucci AA, Silberman H, Omura G, 1985. Phase III study of BCOP v CHOP in unfavorable categories of malignant lymphoma: a Southeastern Cancer Study Group trial. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol 3, 1188–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll MG, Kirpekar F, Maggert KA, Yoder JA, Hsieh C-L, Zhang X, Golic KG, Jacobsen SE, Bestor TH, 2006. Methylation of tRNAAsp by the DNA Methyltransferase Homolog Dnmt2. Science 311, 395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon LI, Harrington D, Andersen J, Colgan J, Glick J, Neiman R, Mann R, Resnick GD, Barcos M, Gottlieb A, 1992. Comparison of a second-generation combination chemotherapeutic regimen (m-BACOD) with a standard regimen (CHOP) for advanced diffuse non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med 327, 1342–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann V, Haferlach C, Weissmann S, Roller A, Schindela S, Poetzinger F, Stadler K, Bellos F, Kern W, Haferlach T, Schnittger S, Kohlmann A, 2013. The molecular profile of adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Mutations in RUNX1 and DNMT3A are associated with poor prognosis in T-ALL. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 52, 410–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenbaum Y, Cedar H, Razin A, 1982. Substrate and sequence specificity of a eukaryotic DNA methylase. Nature 295, 620–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Wang L, Li J, Ding Z, Xiao J, Yin X, He S, Shi P, Dong L, Li G, Tian C, Wang J, Cong Y, Xu Y, 2015. Structural insight into autoinhibition and histone H3-induced activation of DNMT3A. Nature 517, 640–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha K, Lee GE, Palii SS, Brown KD, Takeda Y, Liu K, Bhalla KN, Robertson KD, 2011. Rapid and transient recruitment of DNMT1 to DNA double-strand breaks is mediated by its interaction with multiple components of the DNA damage response machinery. Hum. Mol. Genet 20, 126–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney SL, Upchurch GM, Opavska J, Klinkebiel D, Hlady RA, Roy S, Dutta S, Datta K, Opavsky R, 2016. Dnmt3a is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor in CD8+ peripheral T cell lymphoma. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata K, Okano M, Lei H and Li E, 2002. Dnmt3L cooperates with the Dnmt3 family of de novo DNA methyltransferases to establish maternal imprints in mice. Development. 129, 983–1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann A, Schmitt S, Jeltsch A, 2003. The human Dnmt2 has residual DNA-(cytosine-C5) methyltransferase activity. J. Biol. Chem 278, 31717–31721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander MC, Fornace AJ, 2002. Genomic instability, centrosome amplification, cell cycle checkpoints and Gadd45a. Oncogene 21, 6228–6233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz-Schietinger C, Matje DM, Harrison MF, Reich NO, 2011. Oligomerization of DNMT3A controls the mechanism of de Novo DNA methylation. J. Biol. Chem 286, 41479–41488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz-Schietinger C, Matje DM, Reich NO, 2012. Mutations in DNA Methyltransferase (DNMT3A) Observed in acute myeloid leukemia patients disrupt processive methylation. J. Biol. Chem 287, 30941–30951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch A, Jurkowska RZ, 2016. Allosteric control of mammalian DNA methyltransferases – a new regulatory paradigm. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 8556–8575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D, Jurkowska RZ, Zhang X, Jeltsch A, Cheng X, 2007a. Structure of Dnmt3a bound to Dnmt3L suggests a model for de novo DNA methylation. Nature 449, 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D, Jurkowska RZ, Zhang X, Jeltsch A, Cheng X, 2007b. Structure of Dnmt3a bound to Dnmt3L suggests a model for de novo DNA methylation. Nature 449, 248–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA, Ohtani H, Chakravarthy A, De Carvalho DD, 2019. Epigenetic therapy in immune-oncology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 19, 151–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SE, Grozea PN, Metz EN, Haut A, Stephens RL, Morrison FS, Butler JJ, Byrne GE, Moon TE, Fisher R, Haskins CL, Coltman CA, 1979. Superiority of adriamycin-containing combination chemotherapy in the treatment of diffuse lymphoma: a Southwest Oncology Group study. Cancer 43, 417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkowska RZ, Rajavelu A, Anspach N, Urbanke C, Jankevicius G, Ragozin S, Nellen W, Jeltsch A, 2011. Oligomerization and binding of the Dnmt3a DNA methyltransferase to parallel DNA molecules: heterochromatic localization and role of Dnmt3L. J. Biol. Chem 286, 24200–24207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koya J, Kataoka K, Sato T, Bando M, Kato Y, Tsuruta-Kishino T, Kobayashi H, Narukawa K, Miyoshi H, Shirahige K, Kurokawa M, 2016. DNMT3A R882 mutants interact with polycomb proteins to block haematopoietic stem and leukaemic cell differentiation. Nat. Commun 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreso A, O’Brien CA, van Galen P, Gan OI, Notta F, Brown AMK, Ng K, Ma J, Wienholds E, Dunant C, Pollett A, Gallinger S, McPherson J, Mullighan CG, Shibata D, Dick JE, 2013. Variable clonal repopulation dynamics Influence chemotherapy response in colorectal cancer. Science 339, 543–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küppers R, 2009. The biology of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai AY, Mav D, Shah R, Grimm SA, Phadke D, Hatzi K, Melnick A, Geigerman C, Sobol SE, Jaye DL, Wade PA, 2013. DNA methylation profiling in human B cells reveals immune regulatory elements and epigenetic plasticity at Alu elements during B-cell activation. Genome Res. 23, 2030–2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau DA, Clement K, Ziller MJ, Boyle P, Fan J, Gu H, Stevenson K, Sougnez C, Wang L, Li S, Kotliar D, Zhang W, Ghandi M, Garraway L, Fernandes SM, Livak KJ, Gabriel S, Gnirke A, Lander ES, Brown JR, Neuberg D, Kharchenko PV, Hacohen N, Getz G, Meissner A, Wu CJ, 2014. Locally disordered methylation forms the basis of intratumor methylome variation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell 26, 813–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Morano A, Porcellini A, Muller MT, 2012. GADD45α inhibition of DNMT1 dependent DNA methylation during homology directed DNA repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 2481–2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei H, Oh SP, Okano M, Juttermann R, Goss KA, Jaenisch R, Li E, 1996. De novo DNA cytosine methyltransferase activities in mouse embryonic stem cells. Development 122, 3195–3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz G, Staudt LM, 2010. Aggressive lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med 362, 1417–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard S, Wei W, Anderton J, Vockerodt M, Rowe M, Murray PG, Woodman CB, 2011. Epigenetic and transcriptional changes which follow epstein-barr virus infection of germinal center b cells and their relevance to the pathogenesis of hodgkin’s lymphoma. J. Virol 85, 9568–9577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt H, Page AW, Weier H-U, Bestor TH, 1992. A targeting sequence directs DNA methyltransferase to sites of DNA replication in mammalian nuclei. Cell 71, 865–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev Maor G, Yearim A, Ast G, 2015. The alternative role of DNA methylation in splicing regulation. Trends Genet. 31, 274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, McLellan MD, Lamprecht T, Larson DE, Kandoth C, Payton JE, Baty J, Welch J, Harris CC, Lichti CF, Townsend RR, Fulton RS, Dooling DJ, Koboldt DC, Schmidt H, Zhang Q, Osborne JR, Lin L, O’Laughlin M, McMichael JF, Delehaunty KD, McGrath SD, Fulton LA, Magrini VJ, Vickery TL, Hundal J, Cook LL, Conyers JJ, Swift GW, Reed JP, Alldredge PA, Wylie T, Walker J, Kalicki J, Watson MA, Heath S, Shannon WD, Varghese N, Nagarajan R, Westervelt P, Tomasson MH, Link DC, Graubert TA, DiPersio JF, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, 2010. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med 363, 2424–2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E, Bestor TH, Jaenisch R, 1992. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell 69, 915–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Garrett-Bakelman FE, Chung SS, Sanders MA, Hricik T, Rapaport F, Patel J, Dillon R, Vijay P, Brown AL, Perl AE, Cannon J, Bullinger L, Luger S, Becker M, Lewis ID, To LB, Delwel R, Löwenberg B, Döhner H, Döhner K, Guzman ML, Hassane DC, Roboz GJ, Grimwade D, Valk PJM, D’Andrea RJ, Carroll M, Park CY, Neuberg D, Levine R, Melnick AM, Mason CE, 2016. Distinct evolution and dynamics of epigenetic and genetic heterogeneity in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Med 22, 792–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Ohtani H, Zhou W, Ørskov AD, Charlet J, Zhang YW, Shen H, Baylin SB, Liang G, Grønbæk K, Jones PA, 2016. Vitamin C increases viral mimicry induced by 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 113, 10238–10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyko F, 2018. The DNA methyltransferase family: a versatile toolkit for epigenetic regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet 19, 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes K, De Smedt E, Lemaire M, De Raeve H, Menu E, Van Valckenborgh E, McClue S, Vanderkerken K, De Bruyne E, 2014. The role of DNA damage and repair in decitabine-mediated apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Oncotarget 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoharan A, Roure CD, Rolink AG, Matthias P, 2015. De novo DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b regulate the onset of Igκ light chain rearrangement during early B-cell development. Eur. J. Immunol 45, 2343–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty M, Avery OT, 1946. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types. J. Exp. Med 83, 89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner A, 2005. Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing for comparative high-resolution DNA methylation analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 5868–5877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molavi O, Wang P, Zak Z, Gelebart P, Belch A, Lai R, 2013. Gene methylation and silencing of SOCS3 in mantle cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol 161, 348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momparler RL, 2005. Epigenetic therapy of cancer with 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine). Semin. Oncol 32, 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LD, Le T, Fan G, 2013. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology 38, 23–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrotto S, Ng KP, Jankowska AM, Bodo J, Gopalan B, Guinta K, Mulloy JC, Hsi E, Maciejewski J, Saunthararajah Y, 2012. CpG methylation patterns and decitabine treatment response in acute myeloid leukemia cells and normal hematopoietic precursors. Leukemia 26, 244–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA, Li E, 1999. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell 99, 247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano M, Xie S, Li E, 1998. Cloning and characterization of a family of novel mammalian DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferases. Nat. Genet 19, 219–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palii SS, Van Emburgh BO, Sankpal UT, Brown KD, Robertson KD, 2008. DNA methylation inhibitor 5-Aza-2’-Deoxycytidine induces reversible genome-wide DNA damage that is distinctly influenced by Dna methyltransferases 1 and 3B. Mol. Cell. Biol 28, 752–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paronetto MP, Passacantilli I, Sette C, 2016. Alternative splicing and cell survival: from tissue homeostasis to disease. Cell Death Differ. 23, 1919–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole CJ, Zheng W, Lodh A, Yevtodiyenko A, Liefwalker D, Li H, Felsher DW, van Riggelen J, 2017. DNMT3B overexpression contributes to aberrant DNA methylation and MYC-driven tumor maintenance in T-ALL and Burkitt’s lymphoma. Oncotarget 8, 76898–76920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X, Hother C, Ralfkiær UM, Søgaard A, Lu Q, Workman CT, Liang G, Jones PA, Grønbæk K, 2010. Equitoxic doses of 5-Azacytidine and 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine induce diverse immediate and overlapping heritable changes in the transcriptome. PLoS ONE 5, e12994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren W, Gao L, Song J, 2018. Structural basis of DNMT1 and DNMT3A-mediated DNA methylation. Genes 9, 620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi L, Datta D, Serrat J, Morey L, Solanas G, Avgustinova A, Blanco E, Pons JI, Matallanas D, Von Kriegsheim A, Di Croce L, Benitah SA, 2016. Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b associate with enhancers to regulate human epidermal stem cell homeostasis. Cell Stem Cell 19, 491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robaina MC, Mazzoccoli L, Arruda VO, Reis F.R. de S., Apa AG, de Rezende LMM, Klumb CE, 2015. Deregulation of DNMT1, DNMT3B and miR-29s in Burkitt lymphoma suggests novel contribution for disease pathogenesis. Exp. Mol. Pathol 98, 200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roller A, Grossmann V, Bacher U, Poetzinger F, Weissmann S, Nadarajah N, Boeck L, Kern W, Haferlach C, Schnittger S, Haferlach T, Kohlmann A, 2013. Landmark analysis of DNMT3A mutations in hematological malignancies. Leukemia 27, 1573–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roulois D, Loo Yau H, Singhania R, Wang Y, Danesh A, Shen SY, Han H, Liang G, Jones PA, Pugh TJ, O’Brien C, De Carvalho DD, 2015. DNA-demethylating agents target colorectal cancer cells by inducing viral mimicry by endogenous transcripts. Cell 162, 961–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui L, Schmitz R, Ceribelli M, Staudt LM, 2011. Malignant pirates of the immune system. Nat. Immunol 12, 933–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russler-Germain DA, Spencer DH, Young MA, Lamprecht TL, Miller CA, Fulton R, Meyer MR, Erdmann-gilmore p., townsend r.r., wilson r.k., ley t.j., 2014. The R882H DNMT3A mutation associated with AML dominantly inhibits wild-type DNMT3A by blocking its ability to form active tetramers. Cancer Cell 25, 442–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert HL, Blumenthal RM, Cheng X, 2003. Many paths to methyltransfer: a chronicle of convergence. Trends Biochem. Sci 28, 329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SA, Dong W-F, Ichinohasama R, Hirsch C, Sheridan D, Sanche SE, Geyer CR, DeCoteau JF, 2006. 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine) can relieve p21WAF1 repression in human acute myeloid leukemia by a mechanism involving release of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) without requiring p21WAF1 promoter demethylation. Leuk. Res 30, 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaknovich R, Cerchietti L, Tsikitas L, Kormaksson M, De S, Figueroa ME, Ballon G, Yang SN, Weinhold N, Reimers M, Clozel T, Luttrop K, Ekstrom TJ, Frank J, Vasanthakumar A, Godley LA, Michor F, Elemento O, Melnick A, 2011. DNA methyltransferase 1 and DNA methylation patterning contribute to germinal center B-cell differentiation. Blood 118, 3559–3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SL, Gaudet S, Albeck JG, Burke JM, Sorger PK, 2009. Non-genetic origins of cell-to-cell variability in TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Nature 459, 428–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelling A, Wu C-T, Bertram K, Hashwah H, Theocharides APA, Manz MG, Tzankov A, Müller A, 2019. Pharmacological DNA demethylation restores SMAD1 expression and tumor suppressive signaling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 3, 3020–3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Yamada T, Kihara-Negishi F, Sakurai T, Hara E, Tenen DG, Hozumi N, Oikawa T, 2006. Site-specific DNA methylation by a complex of PU.1 and Dnmt3a/b. Oncogene 25, 2477–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerev TM, Wirth T, Ushmorov A, 2017. Activation of oncogenic pathways in classical Hodgkin lymphoma by decitabine: A rationale for combination with small molecular weight inhibitors. Int. J. Oncol 50, 555–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm I, Wagner M, Schmelz K, 2005. Decitabine activates specific caspases downstream of p73 in myeloid leukemia. Ann. Hematol 84, 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teater M, Dominguez PM, Redmond D, Chen Z, Ennishi D, Scott DW, Cimmino L, Ghione P, Chaudhuri J, Gascoyne RD, Aifantis I, Inghirami G, Elemento O, Melnick A, Shaknovich R, 2018. AICDA drives epigenetic heterogeneity and accelerates germinal center-derived lymphomagenesis. Nat. Commun 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]