Abstract

The exercise pressor reflex is exaggerated in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Hyperglycemia, a main characteristic of T2DM, likely contributes to this exaggerated response. However, the isolated effect of acute hyperglycemia, independent of T2DM, on the exercise pressor reflex is not known. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the effect of acute, local exposure to hyperglycemia on the exercise pressor reflex and its two components, namely the mechanoreflex and the metaboreflex, in healthy rats. To accomplish this, we determined the effect of an acute intra-arterial glucose infusion (0.25 g/mL) on cardiovascular responses to static contraction (i.e., exercise pressor reflex) and tendon stretch (i.e., mechanoreflex) for 30 s, as well as intra-arterial lactic acid (24 mM) injection (i.e., metaboreflex) in fasted unanesthetized, decerebrated Sprague-Dawley rats. We measured and compared changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) before and after glucose infusion. We found that acute glucose infusion did not affect the pressor response to static contraction (ΔMAP: before: 15 ± 2 mmHg, after: 12 ± 2 mmHg; n=8, p > 0.05), tendon stretch (ΔMAP: before: 12 ± 1 mmHg, after: 12 ± 3 mmHg; n=8, p > 0.05), or lactic acid injection (ΔMAP: before: 13 ± 2 mmHg, after: 17 ± 3 mmHg; n=9, p > 0.05). Likewise, cardioaccelerator responses were unaffected by glucose infusion, p > 0.05 for all. In conclusion, these findings suggest that acute, local exposure to hyperglycemia does not affect the exercise pressor reflex or either of its components.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes mellitus, blood glucose, hyperinsulinemia, blood pressure

INTRODUCTION

Exercise evokes an increase in blood pressure, heart rate, and myocardial contractility to meet the metabolic demands of working skeletal muscle (2, 25). Both the exercise pressor reflex, a feedback mechanism originating in working skeletal muscle, and central command, a feedforward mechanism originating in the higher brain centers, increase sympathetic activity and decrease parasympathetic activity during exercise (1, 9). In addition, the arterial baroreflex, a feedback mechanism originating in the carotid sinuses and aortic arch, modulates changes in sympathetic and parasympathetic activity during exercise (35). The afferent arm of the exercise pressor reflex is comprised of thinly myelinated group III afferents and unmyelinated group IV afferents, which respond primarily to mechanical (mechanoreflex) or metabolic (metaboreflex) stimuli, respectively (16, 17, 26, 43). Although the exercise pressor reflex is essential to the circulatory adjustments needed during exercise, studies suggested that this reflex is exaggerated in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (11, 27). Importantly, this exaggerated response can lead to adverse cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction and stroke (3, 28, 29, 39). Hyperglycemia, a main characteristic of T2DM, may potentially contribute to the exaggerated pressor response during exercise in individuals with this disease (18, 28, 29, 40).

Studies in both animals and humans have shown an exaggerated exercise pressor reflex in T2DM. Moreover, both the mechanoreflex and the metaboreflex contribute to this exaggerated response (11, 19, 27). Kim et al. (27) were the first to show that both pressor and sympathetic responses to static muscle contraction were exaggerated in a high-fat diet, streptozotocin-induced T2DM rat model. Grotle et al. (11) extended these findings to show that the mechanoreflex, evoked by passive tendon stretch, was likewise exaggerated in the UCD-T2DM rat model. These findings are consistent with exaggerated sympathetic and blood pressure responses to static handgrip exercise and post-exercise ischemia in individuals with T2DM (19). The underlying mechanisms for this exaggerated exercise pressor reflex in T2DM are not fully understood; however, hyperglycemia likely plays a role, either directly or indirectly (5, 6, 8, 41).

Several studies have suggested a possible connection between hyperglycemia and the exaggerated blood pressure response to exercise. For example, Holwerda et al. (19) found a strong relationship between sympathetic responses to post exercise ischemia (metaboreflex activation) and blood glucose level. Moreover, Marfella et al. (31) found that inducing acute hyperglycemia in newly diagnosed T2DM individuals resulted in a significant increase in blood pressure along with circulating catecholamines and that these responses were independent of increases in insulin. Additional studies by Marfella et al. (32–34) also provide indirect evidence of acute hyperglycemia affecting autonomic function at rest. Previous studies suggest that the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting from hyperglycemia, can sensitize afferent nerve endings and may contribute to an exaggerated exercise pressor reflex (15, 33, 37). For example, the sensitization of the peripheral nerve endings of group III and IV afferents by ROS can lead to an exaggerated exercise pressor reflex (15, 44). Although it is not known how quickly ROS are produced or how long it takes to sensitize muscle afferents, Yu et al. (45) reported that ROS production was increased after just 15 min of hyperglycemia in rat livers and myoblast cells. Thus, these studies support a possible role of local, acute hyperglycemia in increasing blood pressure during exercise. However, it is not known whether acute hyperglycemia alone, independent of other T2DM characteristics (i.e., hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance) influences the manifestation of the exercise pressor reflex or its components.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the effect of local, acute exposure to hyperglycemia on the exercise pressor reflex and to investigate the contributions of the mechanoreflex and metaboreflex. We hypothesized that local, acute exposure to hyperglycemia would exaggerate the exercise pressor reflex in otherwise healthy rats, and that this would be due to the effect of glucose on both the mechanoreflex and the metaboreflex. To accomplish this, we compared the pressor response to static muscle contraction (i.e., exercise pressor reflex), tendon stretch (i.e., mechanoreflex), and the local injection of lactic acid (i.e., metaboreflex) before and after glucose infusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Texas at Austin. Adult male (n = 23; 344 ± 17 g) and female (n = 23; 281 ± 13 g) Sprague-Dawley rats from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) were used in these experiments. The rats were housed in a temperature-controlled room (24 ± 1°C) with a 12:12 h light-dark cycle and fed a standard diet and tap water ad libitum. Following all terminal experiments, rats were euthanized by injecting saturated potassium chloride intravenously (> 3 mL/kg) followed by a thoracotomy.

Surgical preparation.

On the day of the experiment, fasted rats were anesthetized with isoflurane gas (2 – 5 %) in 100 % oxygen. Body weight was assessed. The trachea was cannulated and the lungs were mechanically ventilated (Model 683 small animal ventilator, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, Massachusetts). The right jugular vein and both common carotid arteries were cannulated (PE-50) for fluid and drug delivery and blood pressure measurement, respectively. Although both carotid arteries were cannulated, the baroreflex remained intact during the surgical preparation, as demonstrated by previous studies (4). One of the carotid arterial catheters was connected to a pressure transducer (CWE DTX-1, Ardmore, PA) for blood pressure and heart rate measurement (CED, Cambridge, UK), and the other catheter was used for blood gas analysis (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA). The left superficial epigastric artery, which branches from the femoral artery and supplies the hindlimb, was cannulated (PE-8) for local lactic acid injection and glucose infusion. A reversible snare (2–0 silk suture) was placed around the left iliac artery and vein to control blood flow to and from the left hindlimb muscles.

To evoke a static muscle contraction, the sciatic nerve was surgically isolated, and a stimulating electrode was placed underneath it. The left hindlimb muscles were exposed, and the skin was retracted. The calcaneal bone of the same leg was severed, and the Achilles tendon was attached to a force transducer (model FT-03, Grass Instruments, West Warwick, RI), which was connected to a rack-and-pinion for tension measurement. An automated blood gas analyzer (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA) was used to measure arterial PO2, PCO2, and pH. Arterial blood gas and pH were maintained within normal range by either adjusting ventilation or by intravenously injecting sodium bicarbonate (8.5 %). A rectal temperature probe was used to measure body temperature, which was maintained between 36.5°C and 38°C using a heating lamp and plate.

Rats were then placed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame for the decerebration procedure and the spine and pelvis of the rat were stabilized using a pair of metal spikes. Dexamethasone (2 mg/mL; 0.2 mL) was first injected intravenously, to prevent excessive swelling in the brain, before performing a pre-collicular decerebration. All neural tissue rostral to the section was removed, and the cranial vault was filled with gauze to stop any bleeding. Immediately after decerebration, gas anesthesia was discontinued and rats were allowed to stabilize for at least 1 h before starting the experimental protocol (42).

Experimental Protocols

Determination of glucose concentration.

We first determined the duration and concentration of glucose infusion needed to increase local blood glucose to similar concentrations (~580 mg/dL) as those observed in T2DM rats with exaggerated pressor responses to static contraction (11). To do this, Sprague-Dawley rats were infused with a glucose solution (0.25 g/mL; n=3; 0.01 mL/min over 15 min), using an infusion pump (Intertek 9801781, Harvard Apparatus Houston), into the arterial supply of the left hindlimb through the superficial epigastric artery. Prior to the infusion, the snare surrounding the iliac artery and vein was tightened such that the glucose solution was restricted to the circulation of the hindlimb. To prevent an endogenous insulin response, somatostatin was infused (3.9 μg/100 μl) systemically through the jugular vein (0.01 mL/min) at the same time that glucose was infused into the hindlimb circulation (21). Blood glucose was measured every five min during glucose infusion and five min after glucose infusion, when the snare was released, by puncturing the popliteal vein in both hindlimbs. We found that by infusing 0.25 g/mL of glucose over 15 min into the hindlimb circulation we could evoke the desired local hyperglycemia quickly (within five min) without evoking a prolonged ischemic state for the hindlimb due to the tightened snare (Fig. 1). Blood glucose concentration measured five min after infusion represents the blood glucose concentration at the time of muscle contraction, tendon stretch, or lactic acid injection.

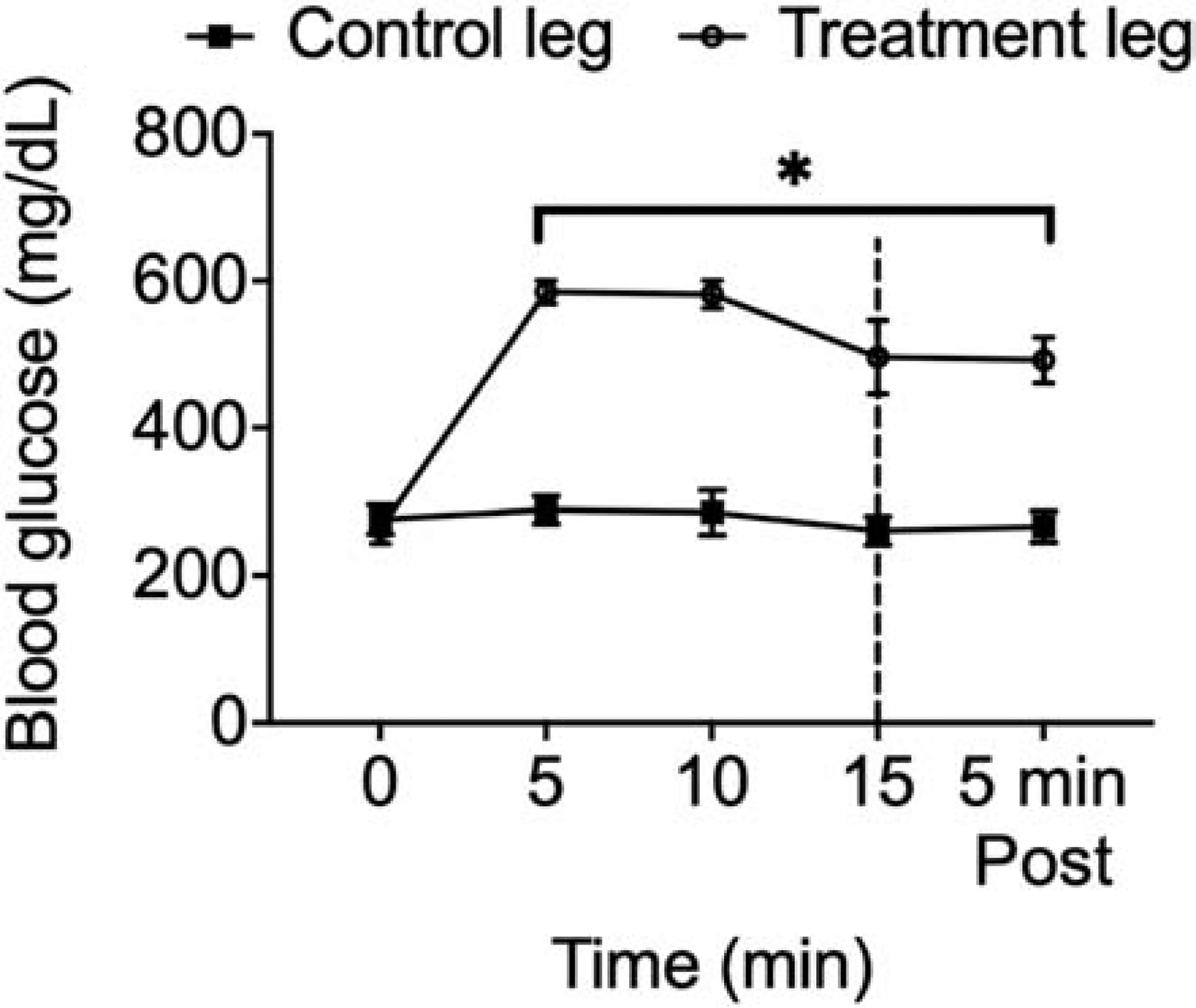

Fig. 1.

Glucose concentration in the hindlimb over 15 min of glucose (0.25 g/mL) infusion and five min post infusion. Local glucose concentration increased significantly by the 5th min, and remained elevated, compared to the contralateral limb, which was used as a control. (*) p < 0.05 (two-way ANOVA) indicates statistically different from the glucose concentration at 0 min. Dashed line indicates the end of the infusion and release of the snare.

Glucose infusion.

After we determined the appropriate dose of glucose (0.25 g/mL infused over 15 min), we then determined the effect of glucose infusion on the pressor and cardioaccelerator responses to one of three different stimuli known to evoke the exercise pressor reflex (static contraction), the mechanoreflex (passive tendon stretch) and the metaboreflex (lactic acid injection). In order to do this, we stimulated the muscle, tightened the snare, infused glucose, released the snare, allowed the hindlimb muscles to re-perfuse for five min, and then re-stimulated the muscle a second time. In addition, somatostatin was simultaneously infused through the jugular vein during glucose infusion. To address the possible effects of somatostatin on the exercise pressor reflex, we infused somatostatin into the jugular vein and saline, in place of glucose, into the circulation of the hindlimb in a subset of rats (n=3). Changes in blood pressure and heart rate to each stimulus were measured and compared before and after infusing glucose. At the end of each experiment, Evans blue dye (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was injected into the epigastric artery while the snare was tightened to ensure that the infused glucose reached the targeted muscle.

Insulin measurement.

To measure blood insulin concentration, carotid blood was taken before and 20 min after glucose infusion. These samples were taken from two groups. One group had both somatostatin and glucose infused simultaneously and the other group had only glucose infused. Following collection, blood samples were left to clot for 30 min before being centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000 g. Serum was then aliquoted into tubes and frozen at −80°C for subsequent batch analyses. A high-sensitive rat insulin ELISA kit (ALPCO, Salem, NH) was used to measure insulin concentration in the samples. Standards, controls, and samples were added, in duplicate, to a 96 -well plate and analyzed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Plates were read using an infinite F200 pro (TECAN, Switzerland) to determine the absorbance for each well. Four-parameter-Marquardt logistic regression was used to construct a standard curve, which was then used to calculate control and sample unknown concentrations. R2 for the standard curve was 0.999 and the coefficient of variation between sample duplicates averaged < 8 %. In our laboratory, the intra-assay variability (%CV) for this kit is 7 % and the inter-assay variability (%CV) is 8 %.

Static contraction.

Prior to contraction, baseline tension (90 – 100g) was applied to the hindlimb muscle for 30 s. Static contraction of the hindlimb muscles was then evoked by electrically stimulating (40 Hz; 0.01 ms; ≤ 2 times motor threshold; for 30 s) the sciatic nerve. At the end of all experiments, 0.5 mL of pancuronium bromide (1 mg/mL; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was injected through the jugular vein to paralyze the rat and another stimulation was performed using the same parameters as those used previously to contract the hindlimb muscles. This was done to verify that the pressor responses before pancuronium bromide injection were not due to direct stimulation of the skeletal muscle afferents responsible for evoking the exercise pressor reflex. If pancuronium bromide abolished the pressor response to electrical stimulation of the sciatic nerve, it was concluded that the pressor response to static contraction was not due to any direct stimulation of skeletal muscle afferents.

Tendon stretch.

Prior to stretching the Achilles tendon, baseline tension (90 – 100g) was applied to the hindlimb muscle for 30 s. The Achilles tendon was then stretched by rapidly turning the rack-and-pinion, and a tension equivalent to that achieved during a static muscle contraction was maintained for 30 s.

Lactic acid injection.

Prior to lactic acid injection, the abdominal snare was tightened for 30 s in order to prevent lactic acid from circulating systemically. Lactic acid (0.2 mL, 24 mM, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was then injected through the superficial epigastric artery. At the end of the experiment, Evans blue dye (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was injected into the epigastric artery while the snare was tightened to ensure the lactic acid reached the targeted muscle.

Data analysis.

Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) are presented as means ± SEM. Real-time MAP (mmHg), HR (bpm), and muscle tension (g) were recorded with a Spike2 data acquisition system (Cambridge Electronic Design). The tension-time index (TTI, kg•s) was calculated by integrating the area between the tension trace and the baseline level during the 30 s contraction or stretch. All variables were compared before and after glucose infusion. Glucose measurement data and insulin concentrations were analyzed using two-way ANOVAs. Holm-Sidak’s post hoc tests were used when a significant interaction was detected. Baseline blood pressures and HR, as well as peak changes in MAP and HR during static contraction, tendon stretch, and lactic acid injection before and after glucose infusion/somatostatin and saline/somatostatin, were analyzed using paired t-tests. GraphPad Prism 8 Software (La Jolla, CA) was used for all statistical analyses. The criterion level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Insulin.

Plasma insulin concentrations before and 20 min after glucose infusion with and without somatostatin are shown in Table 1. The interaction between treatment effect (with or without somatostatin) and time effect (before and 15 min after glucose infusion) was not significantly different (p = 0.54). There was no significant main effect of either treatment or time (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Bodyweight, blood glucose, and insulin concentration before and after glucose infusion

| Treatment group | n | Bodyweight (g) | Blood glucose (mg/dL) | Insulin (ng/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before infusion | 20 min after infusion | ||||

| Glucose w/o somatostatin | 6 | 414 ± 34 | 131 ± 9 | 0.81 ± 0.11 | 1.35 ± 0.2 |

| Glucose w/ somatostatin | 5 | 358 ± 27 | 149 ± 11 | 1.07 ± 0.29 | 2.25 ± 1.23 |

Values are Mean± SE.

Baseline measurements.

Baseline MAP and HR before and after glucose infusion are shown in their corresponding bar graphs in Fig. 2, 3, and 4. There was no difference in baseline MAP before and after glucose infusion before any of the stimuli (p > 0.05). Likewise, baseline HR before tendon stretch was not different before and after glucose infusion (p > 0.05). However, baseline HR before both static contraction and lactic acid injection was significantly lower after glucose infusion compared to before glucose infusion, which is likely due to the cardio-depressive effects of somatostatin (p < 0.05) (30).

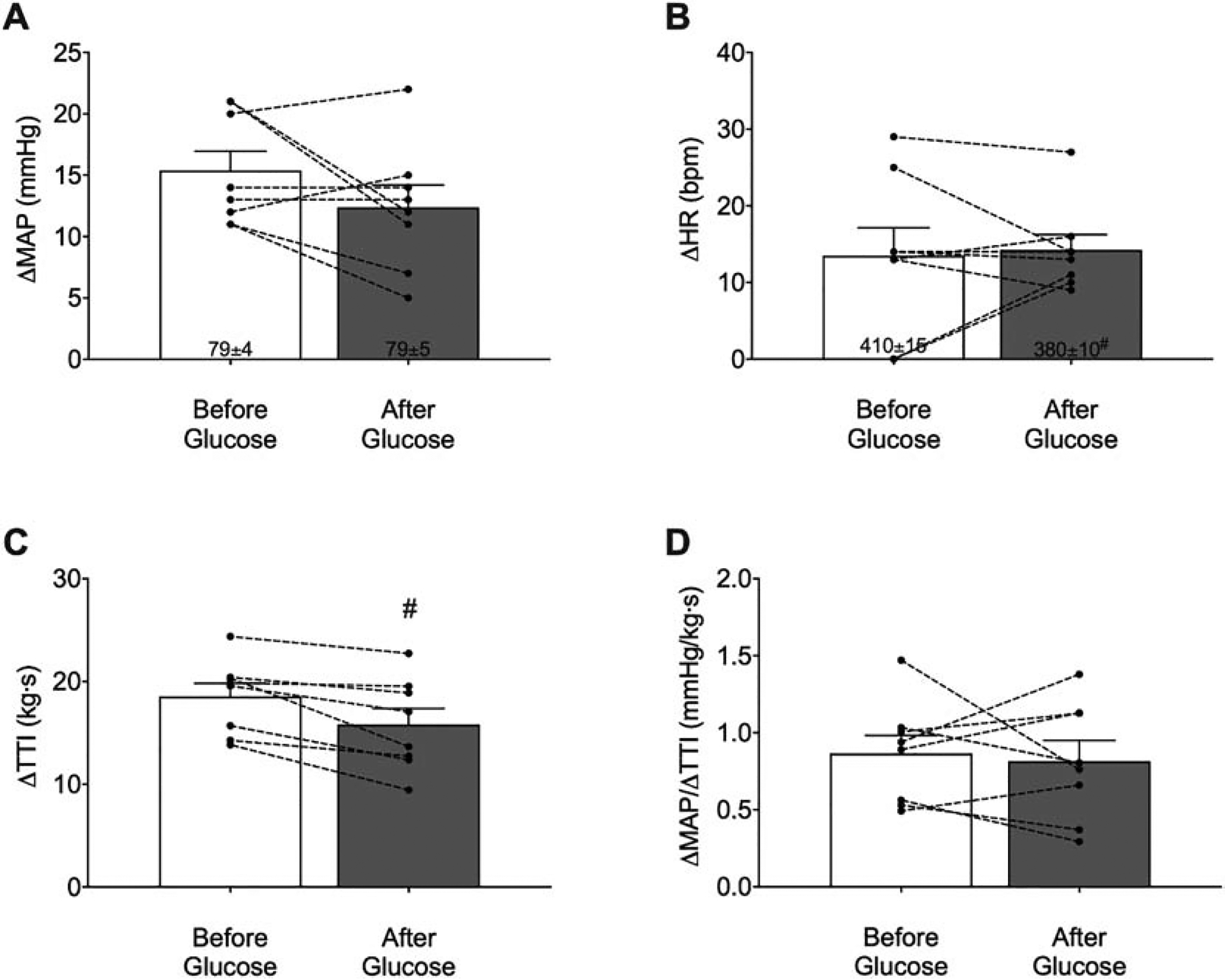

Fig. 2.

Means ± SE and individual data showing the peak pressor (A) and cardioaccelerator (B) responses to static contraction before and after glucose infusion (n=8). Glucose infusion did not affect the pressor or the cardioaccelerator response to static contraction. Surprisingly, glucose infusion did result in a lower developed tension [tension-time index (TTI)] (C). Normalizing the pressor response to developed tension revealed no difference in the pressor response before and after glucose infusion (D). (#) indicates significantly lower relative to before glucose infusion, p < 0.05 (t-test). MAP, mean arterial pressure; HR, heart rate.

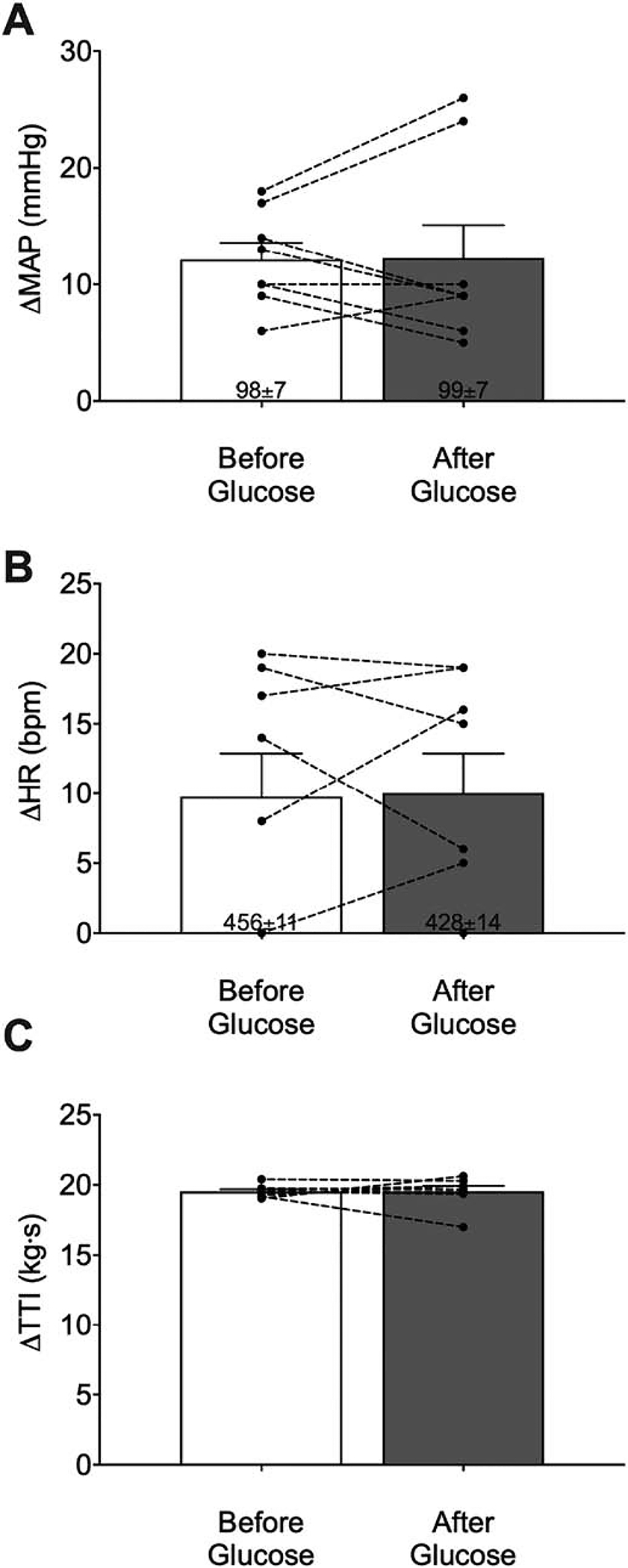

Fig. 3.

Means ± SE and individual data showing peak pressor (A) and cardioaccelerator (B) responses to tendon stretch before and after glucose infusion (n=8). Intra-arterial infusion of glucose did not affect the peak pressor or cardioaccelerator responses to tendon stretch. Developed tensions [tension-time index (TTI)] were similar before and after glucose infusion (C).

Fig. 4.

Means ± SE and individual data showing that the peak pressor (A) and cardioaccelerator (B) responses to lactic acid injection were not significantly different before and after glucose infusion (n=9). (#) indicates statistically lower baseline HR from before glucose infusion, p < 0.05 (t-test).

Static muscle contraction.

The peak pressor response to static contraction was not significantly different before and after glucose infusion (ΔMAP: before: 15 ± 2 mmHg; after: 12 ± 2 mmHg; n = 8; p > 0.05; Fig. 2A). Similarly, the cardioaccelerator response to static contraction was not significantly different before and after glucose infusion (ΔHR: before: 14 ± 4 bpm; after: 14 ± 2 bpm; n = 8; p > 0.05; Fig. 2B). Surprisingly, developed tension during static contraction was significantly lower after glucose infusion compared to before glucose infusion (ΔTTI: before: 19 ± 1 kg•s; after: 16 ± 2 kg•s; n = 8; p < 0.05; Fig. 2C). One possible explanation for this is that glucose infusion changed the osmolality of the interstitial environment, thereby affecting the contractile properties of the muscle. Therefore, to account for the difference in developed tension and, thus, the “stimuli” of skeletal muscle afferents, we normalized the pressor responses to changes in developed tension (ΔMAP/ ΔTTI). The normalized peak pressor response during static contraction was not significantly different before and after glucose infusion (normalized peak pressor before: 0. 9 ± 0.1 mmHg/(kg•s); after: 0.8 ± 0.1 mmHg/(kg•s); n = 8; p > 0.05, Fig. 2D). Furthermore, infusing somatostatin with saline did not affect the pressor or cardioaccelerator responses to static contraction (ΔMAP: before: 11 ± 2 mmHg; after: 10 ± 2 mmHg; ΔHR: before: 14 ± 3 bpm; after: 12 ± 4 bpm; n = 3; p > 0.05).

Tendon stretch.

The peak pressor responses to tendon stretch were not significantly different before and after glucose infusion (ΔMAP: before: 12 ± 1 mmHg; after: 12 ± 3 mmHg; n = 8; p > 0.05; Fig. 3A). Similarly, the cardioaccelerator responses to tendon stretch were also not significantly different before and after glucose infusion (ΔHR: before: 10 ± 3 bpm; after: 10 ± 3 bpm; n = 8; p > 0.05; Fig. 3B). Developed tensions during tendon stretch were also similar before and after glucose infusion (ΔTTI: before: 20 ± 0.1 kg•s; after: 20 ± 0.4 kg•s, n = 8; p > 0.05, Fig. 3C).

Lactic acid injection.

The peak pressor responses to lactic acid injection were not significantly different before and after glucose infusion (ΔMAP: before: 13 ± 2 mmHg; after: 17 ± 3 mmHg; n = 9; p > 0.05; Fig. 4A). Similarly, the cardioaccelerator responses to lactic acid injection were also not significantly different before and after glucose infusion (ΔHR: before: 10 ± 3 bpm; after: 10 ± 5 bpm; n= 9; p > 0.05; Fig. 4B).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of local, acute exposure to hyperglycemia on the exercise pressor reflex and to investigate the contribution of the mechanoreflex and metaboreflex. We hypothesized that local, acute exposure to hyperglycemia would exaggerate the exercise pressor reflex in otherwise healthy rats and that this would be due to its effect on both the mechanoreflex and metaboreflex. Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that acute local hyperglycemia, evoked by infusing 0.25 g/mL glucose into the hindlimb circulation, did not affect the pressor or cardioaccelerator responses to static contraction, passive tendon stretch, or local intra-arterial lactic acid injection. Thus, these findings suggest that acute, local exposure to hyperglycemia does not affect the exercise pressor reflex or either of its components, the mechanoreflex and the metaboreflex.

In this study, we were able to create an acute, local hyperglycemic environment without affecting systemic glucose or insulin concentrations. To create a hyperglycemic environment similar to what we observed in the UCD-T2DM model (11), we infused glucose into the left hindlimb and prevented blood flow to and from the area by temporally occluding the circulation to the hindlimb muscles. As an additional control, we systemically co-infused somatostatin to prevent an endogenous insulin response. These measures were necessary as insulin has been shown to affect the activation of the sympathetic nervous system (20, 23). Our findings show that local glucose concentration was significantly elevated, as intended, compared to the glucose concentration measured from the contralateral leg, which was freely perfused. Importantly, circulating insulin levels were not higher after glucose infusion. Thus, using this approach, we demonstrated that a glucose environment, similar to that seen in T2DM, could be re-created in healthy rats, independent of changes in systemic insulin levels, to investigate the effects of local, acute exposure to hyperglycemia on the exercise pressor reflex.

Several studies suggest that the exercise pressor reflex and its two components are exaggerated in the presence of hyperglycemia in T2DM animals and humans. Using two different T2DM rat models, studies have shown that T2DM leads to exaggerated sympathetic activity and pressor responses to static contraction and tendon stretch (i.e., mechanoreflex) compared to healthy controls (11, 27). Similarly, individuals with T2DM exhibit exaggerated sympathetic activity and pressor responses to static handgrip exercise and post-exercise ischemia (i.e., metaboreflex) compared to healthy controls (19). Even though hyperglycemia was clearly present in these subjects (both rat and human), findings from the current study suggest that acute hyperglycemia does not contribute to evoking an exaggerated exercise pressor reflex in T2DM. It is, however, still likely that chronic hyperglycemia plays a role in evoking these exaggerated responses, perhaps in conjunction with other factors related to T2DM such as oxidative stress and hyperinsulinemia.

Contrary to our hypothesis, local, acute exposure to hyperglycemia had no effect on the exercise pressor reflex or either of its components. Though we can only speculate, it is possible that a preserved antioxidant capacity in healthy rats may, in part, explain why local, acute exposure to hyperglycemia had no effect. For example, both muscle contraction and a hyperglycemic environment stimulate the production of free radicals in skeletal muscle (22, 36, 45). Although free radicals have important signaling functions in healthy conditions, overproductions and the inability to neutralize them in diseases such as T2DM leads to increased oxidative stress (38). Of interest, several studies have demonstrated that free radicals play a role in evoking the exaggerated exercise pressor reflex in disease (15, 44), whereas their role in healthy conditions is controversial, perhaps due to preserved antioxidant capacity in healthy individuals. For example, one study showed that attenuating super-oxide dismutase (SOD) activity, an important antioxidant enzyme, augmented the exercise pressor reflex in healthy rats (44). Similarly, another study showed that pretreatment with SOD attenuated group IV muscle afferent activity during static muscle contraction (7). Collectively, these studies suggest that preserved antioxidant capacity in healthy rats may mask an effect played by free radicals in sensitizing group III and IV afferents. Conversely, impaired antioxidative capacity in T2DM (14) may exaggerate ROS production in response to muscle contraction and hyperglycemia, which leads to an exaggerated exercise pressor reflex. Thus, although the current study did not find an effect of acute hyperglycemia on the exercise pressor reflex, it is still possible that acute hyperglycemia in conditions with an impaired antioxidant capacity, such as T2DM, contribute to exaggerate the exercise pressor reflex. Future studies are, therefore, needed to determine the impact of acute hyperglycemia in conditions with impaired antioxidant capacity on the activation of the exercise pressor reflex.

It is also possible that hyperinsulinemia contributes to the exaggerated exercise pressor reflex found in T2DM. For example, Kim et al. (20) found an exaggerated exercise pressor reflex in T2DM rats with significantly higher insulin concentrations than that in healthy controls (11). This exaggerated response could be in part due to insulin potentiating responses to mechanical stimuli in small dorsal root ganglia and sensitizing group IV muscle afferents (20). The potential effect of insulin on the exercise pressor reflex may also explain why we did not see an exaggerated pressor reflex in the current study since hyperinsulinemia was absent.

Conversely, not all studies investigating T2DM have demonstrated that the exercise pressor reflex and its components are exaggerated in the presence of hyperinsulinemia. For example, Grotle et al. (11) reported exaggerated pressor responses to static muscle contraction and tendon stretch in UCD-T2DM rats that had lower insulin levels than those in the control rats. Likewise, Holwerda et al. showed an exaggerated metaboreflex in T2DM individuals with similar insulin levels to healthy controls (19). Furthermore, studies using the streptozotocin (STZ) induced type 1 diabetic rat model, which destroys pancreatic β-cells thereby causing a reduction in insulin synthesis (10, 24), also report exaggerated pressor responses to static muscle contraction and tendon stretch (12, 13). Although these findings appear to contradict the idea that hyperinsulinemia contributes to an exaggerated exercise pressor reflex in T2DM, it is important to emphasize that the role of hyperinsulinemia was not examined independently from chronic hyperglycemia in these studies. Thus, we are not suggesting that hyperinsulinemia plays no role in exaggerating the EPR in T2DM, but that a complex relationship likely exists between hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in evoking the EPR. Future studies should parse out the role of each as well as their combined role in evoking the exaggerated EPR in T2DM.

In summary, this is the first study to examine the isolated effects of local, acute exposure to hyperglycemia, independent from other characteristics of T2DM, on the exercise pressor reflex. We found that acute, local exposure to hyperglycemia alone does not exaggerate the exercise pressor reflex (static contraction), mechanoreflex (tendon stretch), or the metaboreflex (lactic acid injection) in healthy rats. These findings suggest that it may not be acute hyperglycemia per se, but rather the interactions between hyperglycemia and other disease characteristics, such as oxidative stress or hyperinsulinemia, that contribute to an exaggerated exercise pressor reflex in T2DM. Moreover, it is important to note that the scope of the current study focused on local effects of hyperglycemia and not systemic effects, which are still currently unknown. Future studies are needed to identify the role of these mechanisms and their interaction with hyperglycemia on the exercise pressor in T2DM.

New and Noteworthy:

This is the first study to show that acute local hyperglycemia does not affect the exercise pressor reflex or either of its components, the mechanoreflex or the metaboreflex. These findings are significant as they provide insight into the potential role of acute hyperglycemia in evoking the exaggerated exercise pressor reflex in T2DM.

Grants

This project was supported by NIH R01 HL144723

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Alam M, and Smirk FH. Observations in man upon a blood pressure raising reflex arising from the voluntary muscles. The Journal of physiology 89: 372–383, 1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann M, Runnels S, Morgan DE, Trinity JD, Fjeldstad AS, Wray DW, Reese VR, and Richardson RS. On the contribution of group III and IV muscle afferents to the circulatory response to rhythmic exercise in humans. The Journal of physiology 589: 3855–3866, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen R, Ovbiagele B, and Feng W. Diabetes and Stroke: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Pharmaceuticals and Outcomes. Am J Med Sci 351: 380–386, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Copp SW, Kim JS, Ruiz-Velasco V, and Kaufman MP. The mechano-gated channel inhibitor GsMTx4 reduces the exercise pressor reflex in decerebrate rats. J Physiol 594: 641–655, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Copp SW, Stone AJ, Li J, and Kaufman MP. Role played by interleukin-6 in evoking the exercise pressor reflex in decerebrate rats: effect of femoral artery ligation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H166–173, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E, Groop L, Henry RR, Herman WH, Holst JJ, Hu FB, Kahn CR, Raz I, Shulman GI, Simonson DC, Testa MA, and Weiss R. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 1: 15019, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delliaux S, Brerro-Saby C, Steinberg JG, and Jammes Y. Reactive oxygen species activate the group IV muscle afferents in resting and exercising muscle in rats. Pflugers Arch 459: 143–150, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donath MY, and Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 98–107, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eldridge FL, Millhorn DE, Kiley JP, and Waldrop TG. Stimulation by central command of locomotion, respiration and circulation during exercise. Respir Physiol 59: 313–337, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eleazu CO, Eleazu KC, Chukwuma S, and Essien UN. Review of the mechanism of cell death resulting from streptozotocin challenge in experimental animals, its practical use and potential risk to humans. J Diabetes Metab Disord 12: 60, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grotle AK, Crawford CK, Huo Y, Ybarbo KM, Harrison ML, Graham J, Stanhope KL, Havel PJ, Fadel PJ, and Stone AJ. Exaggerated cardiovascular responses to muscle contraction and tendon stretch in UCD type-2 diabetes mellitus rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 317: H479–H486, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grotle AK, Garcia EA, Harrison ML, Huo Y, Crawford CK, Ybarbo KM, and Stone AJ. Exaggerated mechanoreflex in early-stage type 1 diabetic rats: role of Piezo channels. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology 316: R417–R426, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grotle AK, Garcia EA, Huo Y, and Stone AJ. Temporal changes in the exercise pressor reflex in type 1 diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 313: H708–H714, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grotle AK, and Stone AJ. Exaggerated exercise pressor reflex in type 2 diabetes: Potential role of oxidative stress. Autonomic neuroscience : basic & clinical 222: 102591, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harms JE, Kuczmarski JM, Kim JS, Thomas GD, and Kaufman MP. The role played by oxidative stress in evoking the exercise pressor reflex in health and simulated peripheral artery disease. J Physiol 595: 4365–4378, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes SG, Kindig AE, and Kaufman MP. Comparison between the effect of static contraction and tendon stretch on the discharge of group III and IV muscle afferents. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985) 99: 1891–1896, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes SG, McCord JL, Koba S, and Kaufman MP. Gadolinium inhibits group III but not group IV muscle afferent responses to dynamic exercise. The Journal of physiology 587: 873–882, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henriksen EJ, Diamond-Stanic MK, and Marchionne EM. Oxidative stress and the etiology of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 993–999, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holwerda SW, Restaino RM, Manrique C, Lastra G, Fisher JP, and Fadel PJ. Augmented pressor and sympathetic responses to skeletal muscle metaboreflex activation in type 2 diabetes patients. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H300–309, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hotta N, Katanosaka K, Mizumura K, Iwamoto GA, Ishizawa R, Kim HK, Vongpatanasin W, Mitchell JH, Smith SA, and Mizuno M. Insulin potentiates the response to mechanical stimuli in small dorsal root ganglion neurons and thin fibre muscle afferents in vitro. The Journal of physiology 597: 5049–5062, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh PS. Attenuation of insulin-mediated pressor effect and nitric oxide release in rats with fructose-induced insulin resistance. Am J Hypertens 17: 707–711, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson MJ. Recent advances and long-standing problems in detecting oxidative damage and reactive oxygen species in skeletal muscle. The Journal of physiology 594: 5185–5193, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joyner MJ, and Limberg JK. Insulin and sympathoexcitation: it is not all in your head. Diabetes 62: 2654–2655, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junod A, Lambert AE, Orci L, Pictet R, Gonet AE, and Renold AE. Studies of the diabetogenic action of streptozotocin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 126: 201–205, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman MP, and Hayes SG. The exercise pressor reflex. Clin Auton Res 12: 429–439, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufmann CA, Weinberger DR, Yolken RH, Torrey EF, and Pofkin SG. Viruses and schizophrenia. Lancet 2: 1136–1137, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HK, Hotta N, Ishizawa R, Iwamoto GA, Vongpatanasin W, Mitchell JH, Smith SA, and Mizuno M. Exaggerated pressor and sympathetic responses to stimulation of the mesencephalic locomotor region and exercise pressor reflex in type 2 diabetic rats. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology 317: R270–R279, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laakso M Hyperglycemia and cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 48: 937–942, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laakso M Hyperglycemia as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Prim Care 26: 829–839, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maison P, Tropeano AI, Macquin-Mavier I, Giustina A, and Chanson P. Impact of somatostatin analogs on the heart in acromegaly: a metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 1743–1747, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marfella R, Nappo F, De Angelis L, Paolisso G, Tagliamonte MR, and Giugliano D. Hemodynamic effects of acute hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes care 23: 658–663, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marfella R, Nappo F, Marfella MA, and Giugliano D. Acute hyperglycemia and autonomic function. Diabetes care 24: 2016–2017, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marfella R, Quagliaro L, Nappo F, Ceriello A, and Giugliano D. Acute hyperglycemia induces an oxidative stress in healthy subjects. J Clin Invest 108: 635–636, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marfella R, Verrazzo G, Acampora R, La Marca C, Giunta R, Lucarelli C, Paolisso G, Ceriello A, and Giugliano D. Glutathione reverses systemic hemodynamic changes induced by acute hyperglycemia in healthy subjects. The American journal of physiology 268: E1167–1173, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McRitchie RJ, Vatner SF, Boettcher D, Heyndrickx GR, Patrick TA, and Braunwald E. Role of arterial baroreceptors in mediating cardiovascular response to exercise. Am J Physiol 230: 85–89, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Du XL, Yamagishi S, Matsumura T, Kaneda Y, Yorek MA, Beebe D, Oates PJ, Hammes HP, Giardino I, and Brownlee M. Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature 404: 787–790, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishio N, Taniguchi W, Sugimura YK, Takiguchi N, Yamanaka M, Kiyoyuki Y, Yamada H, Miyazaki N, Yoshida M, and Nakatsuka T. Reactive oxygen species enhance excitatory synaptic transmission in rat spinal dorsal horn neurons by activating TRPA1 and TRPV1 channels. Neuroscience 247: 201–212, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robertson RP, Harmon J, Tran PO, and Poitout V. Beta-cell glucose toxicity, lipotoxicity, and chronic oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 53 Suppl 1: S119–124, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savage MP, Krolewski AS, Kenien GG, Lebeis MP, Christlieb AR, and Lewis SM. Acute myocardial infarction in diabetes mellitus and significance of congestive heart failure as a prognostic factor. Am J Cardiol 62: 665–669, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Selvin E, Marinopoulos S, Berkenblit G, Rami T, Brancati FL, Powe NR, and Golden SH. Meta-analysis: glycosylated hemoglobin and cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 141: 421–431, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shoelson SE, Lee J, and Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 116: 1793–1801, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith SA, Mitchell JH, and Garry MG. Electrically induced static exercise elicits a pressor response in the decerebrate rat. The Journal of physiology 537: 961–970, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stone AJ, Copp SW, Kim JS, and Kaufman MP. Combined, but not individual, blockade of ASIC3, P2X, and EP4 receptors attenuates the exercise pressor reflex in rats with freely perfused hindlimb muscles. Journal of applied physiology 119: 1330–1336, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang HJ, Pan YX, Wang WZ, Zucker IH, and Wang W. NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species in skeletal muscle modulates the exercise pressor reflex. J Appl Physiol (1985) 107: 450–459, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu T, Robotham JL, and Yoon Y. Increased production of reactive oxygen species in hyperglycemic conditions requires dynamic change of mitochondrial morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 2653–2658, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]