Abstract

Bacterial surface lipoproteins are emerging as attractive vaccine candidates due to their biological importance and the feasibility of their large-scale production for vaccine manufacturing. The global prevalence of gonorrhea, resistance to antibiotics, and serious consequences to reproductive and neonatal health necessitate development of effective vaccines. Reverse vaccinology identified the surface-displayed L-methionine binding lipoprotein MetQ (NGO2139) and its homolog GNA1946 (NMB1946) as gonococcal and meningococcal vaccine candidates, respectively. Here, we assessed the suitability of MetQ for inclusion in a gonorrhea vaccine by examining MetQ conservation, its function in Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Ng) pathogenesis, and its ability to induce protective immune responses using a female murine model of lower genital tract infection. In-depth bioinformatics, phylogenetics and mapping the most prevalent Ng polymorphic amino acids to the GNA1946 crystal structure revealed remarkable MetQ conservation: ~97% Ng isolates worldwide possess a single MetQ variant. Mice immunized with rMetQ-CpG (n=40), a vaccine containing a tag-free version of MetQ formulated with CpG, exhibited robust, antigen-specific antibody responses in serum and at the vaginal mucosae including IgA. Consistent with the activity of CpG as a Th1-stimulating adjuvant, the serum IgG1/IgG2a ratio of 0.38 suggested a Th1 bias. Combined data from two independent challenge experiments demonstrated that rMetQ-CpG immunized mice cleared infection faster than control animals (vehicle, p<0.0001; CpG, p=0.002) and had lower Ng burden (vehicle, p=0.03; CpG, p<0.0001). We conclude rMetQ-CpG induces a protective immune response that accelerates bacterial clearance from the murine lower genital tract and represents an attractive component of a gonorrhea subunit vaccine.

Keywords: subunit vaccine, lipoprotein, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, MetQ, infection, crystal structure

INTRODUCTION

Vaccines against infectious diseases have indisputably transformed human health. There is a huge need for continuous efforts to develop vaccines against challenging bacterial infections caused by drug-resistant and/or immunoregulating pathogens. Recently, surface-exposed lipoproteins have garnered interest for their utility in subunit vaccines against disease-causing microbial pathogens, including Clostridioides difficile, Dengue virus, Neisseria meningitidis (Nm) serogroup B, Burkholderia cepacia, and Human Papilloma Virus [1–3]. Lipoproteins play myriad roles in bacterial physiology, which range from acquiring nutrients, contributing to virulence, establishing and maintaining cell envelope homeostasis, and interacting with host cells [4]. During infection, lipoproteins may also act as Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 agonists and contribute to an immune response against the pathogen [1, 5–7]. Characterized by an invariant cysteine residue that is post-translationally modified with two to three acyl chains, lipoproteins are tethered to either the cytoplasmic or outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria through this lipid anchor and may face either the periplasmic space or the extracellular environment [7–10]. Biochemically, lipoproteins are frequently hydrophilic, which facilitates their production in a heterologous host and yields large scale quantities of soluble and natively folded proteins in a cost-effective manner, which are important considerations for vaccine commercialization. Subunit antigens, such as lipoproteins, are also appealing candidates for vaccine development due to their safety and reduced chance of side effects [11, 12].

In concert with gonorrhea vaccine development endeavors, here we focused on the pre-clinical evaluation of MetQ, which is a surface-displayed lipoprotein that elicits strongly bactericidal antibodies [13, 14], as a component of a gonorrhea subunit vaccine. The causative organism of this sexually transmitted infection, Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Ng), is a Gram-negative diplococcus that exclusively plagues humankind, causing about 87 million new cases annually across the globe [15]. In the United States, it remains the second most commonly reported notifiable disease and the number of cases has risen steadily since the historic low in 2009, increasing by 82.6% (a total of 583,405 reported cases) in 2018 [16]. The consequences of gonorrhea and other sexually transmitted infections have devastating health and psychological impacts that profoundly affect quality of life [17]. Clinical presentations of gonorrhea vary between infection site and gender and include cervicitis, urethritis, proctitis, conjunctivitis, or pharyngitis. Disseminated gonorrhea occurs in 0.5–3% patients [18–20]. Women tend to have more frequent asymptomatic urogenital infections and experience serious long-term reproductive health problems including endometritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, pregnancy complications and infertility [21]. Neonates infected during vaginal delivery most typically develop ophthalmia neonatorum, which can lead to blindness if left untreated. Localized infections of other mucosal surfaces can also occur [22]. The grave nature of gonorrhea is further exacerbated by augmenting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infectivity and susceptibility to HIV [23]. Antibiotic therapy remains the mainstay of gonorrhea treatment, alarmingly, however, these antimicrobials are rapidly losing their effectiveness [24–26]. Continued efforts to develop a gonorrhea vaccine are critical.

The MetQ immunogen investigated herein was identified by proteomics and genomics-based reverse vaccinology antigen discovery programs applied to Ng [13, 27, 28] and Nm [13, 27–29], respectively. Using high-throughput proteomics and immunoblotting analyses, we previously reported that MetQ is ubiquitously expressed in diverse Ng isolates [13, 27, 28, 30], in host-relevant growth conditions [13] and in naturally released outer membrane vesicles [13, 27]. In addition to a traditional lipoprotein signal peptide, MetQ contains a NlpA domain homologous to the respective domain in the E. coli methionine binding protein MetQ, NlpA [14, 31]. Indeed, Ng MetQ binds L-methionine with nanomolar affinity. Besides its function in methionine import, MetQ impacts Ng adhesion and invasion of epithelial cells and bacterial survival in primary monocytes, macrophages, and human serum [14].

In this report, we employed bioinformatics to assess MetQ conservation on a large scale, examined its importance in Ng pathogenesis using a mouse infection model, and evaluated its in vivo efficacy against Ng challenge when formulated with a T helper (Th) 1 response-inducing adjuvant (CpG). Our study demonstrates that rMetQ-CpG induces a robust systemic and vaginal humoral immune response and significantly shortens experimental gonococcal infection. Further, we reveal that MetQ is exceptionally conserved and propose its inclusion in a broad-spectrum gonorrhea vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, MetQ purification and other standard methods are provided in Supplemental Information.

Study Design.

Sample size and number of replicates:

Twenty mice per experimental group were immunized in each of two biologically independent immunization/challenge studies. The number of animals was chosen based on our extensive experiences with mouse studies and was selected using power predictions based on the observation that ~75% of mice will be in the correct stage of the estrous cycle at the time of challenge. Mice were randomly assigned to treatment groups and data points from all individual animals were included in analyses. No outliers were defined or excluded. For all experiments, statistical significance and number of replicates are indicated in the figure legends, the main text, or the following sections.

Immunization and challenge studies.

Female BALB/c mice (3–4 weeks old, Charles River Laboratories, NCI BALB/c strain) were immunized by subcutaneous injection of 20 μg of rMetQ mixed with 80 μL of Titermax Gold (Invivogen) (total volume, 150 μL) [day 0 (d0)] followed by three intranasal (IN) boosts on days 14, 24 and 35 consisting of 20 μg of antigen and 20 μg of CpG 1826 (InvivoGen; total volume 40 μL) given in 2, 10 μL volumes per nare, 5 min apart. Control groups received Titermax Gold (d0) and CpG only (d14, 24, 35) or PBS by the same routes. Venous blood and vaginal washes were collected on days 34 and venous blood only on day 49. For vaginal washes, 30 μL of PBS were pipetted in and out of the vagina 3–5 times and pooled. Blood and vaginal washes were centrifuged for 5 min in a microfuge, and the serum fraction and vaginal wash supernatants were stored at −20°C until further analysis. Three weeks after the final immunization, mice in the diestrus or anestrus stage of the reproductive cycle were identified by cytological examination of vaginal smears and implanted with a slow-release 6.5 mg 17β-estradiol pellet (Innovative Research of America) as described [32]. Mice were treated with streptomycin, vancomycin and trimethoprim to suppress the overgrowth of commensal flora that occurs under the influence of estradiol [33]. Two days after pellet implantation, mice were challenged with 106 colony-forming units (CFU) of Ng FA1090. Vaginal swabs were collected every other day for 7 days and suspended in 1 mL of GCBL. Swab suspensions were quantitatively cultured for Ng using the SpiralTek plater (AP5000) and Qcount™ model 530. A portion of the vaginal swab was inoculated onto HIA to monitor the presence of potentially inhibitory commensal flora and smeared on glass slides for assessment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) influx as described [32]. The percentage of mice with positive cultures at each time point was plotted for each experimental group as a Kaplan Meier curve and analyzed by the Log Rank test. Differences in colonization load were assessed by a repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis for multiple pairwise comparisons. The limit of detection was 20 CFU/ml; this value was used in the data analysis for mice from which no Ng was recovered. Additionally, to assess the bacterial burden over time, the mean AUC (log10 CFU versus time) was calculated for each mouse using a baseline of 1.301, corresponding to the assay’s limit of detection of 20 CFU. The geometric means under the curve were compared between the groups using the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric rank sum test and pairwise comparisons between groups were performed with Dunn’s post hoc test as described [34].

Ethics Statement.

Animal experiments were conducted at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) according to the guidelines of the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care under a protocol # MIC16–488 that was approved by the University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The USUHS animal facilities meet the housing service and surgical standards set forth in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” NIH Publication No. 85–23, and the USU Instruction No. 3203, “Use and Care of Laboratory Animals”. Animals are maintained under the supervision of a full-time veterinarian. For all experiments, mice were humanely euthanized by the laboratory technician upon reaching the study endpoint using a compressed CO2 gas cylinder in LAM as per the Uniformed Services University (USU) euthanasia guidelines (IACUC policy 13), which follow those established by the 2013 American Veterinary Medical Association Panel on Euthanasia (http://www.usuhs.mil/usuhs_only/lam/lamws/euth.html).

ELISAs.

Titers of antigen-specific total IgG, IgG1, IgG2a and IgA were measured in serum and vaginal washes by ELISA. Standard antigen titration with serially diluted pooled serum from each test group was used to identify the lowest concentration of rMetQ that gave a linear curve above background when plotted against antiserum dilution. Round bottom high-binding 96 well microtiter plates (Nunc) were coated with 0.5 μg of rMetQ suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 48 h at 4 °C and were blocked with PBS supplemented with 3% Bovine Serum Albumin for 1 h at 37 °C. Serum or vaginal wash samples were serially diluted 3-fold from 1:1 to 1:1.594,323 in PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween (PBST), added to each well, and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The wells were washed with PBST and incubated with secondary antisera diluted 1:5,000: anti-mouse total IgG, anti-mouse IgG1, anti-mouse IgG2a, and anti-mouse IgA (Southern Biotech) conjugated to horse radish peroxidase (HRP). Wells were washed and reactions were developed using TMB Peroxidase EIA Substrate (BioRad). Reactions were stopped by addition of 0.2 M H2SO4 stop solution. End-point titers were determined using the average reading of 8 wells incubated with secondary but no primary antibody plus 3 and 2 standard deviations as baseline for serum and vaginal secretions; respectively. For statistical analysis, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was applied on non-transformed arithmetic data, with p values of <0.05 considered significant.

MetQ bioinformatics analyses.

Polymorphism, phylogenetic, and allele mapping analyses were performed as described by [31], with the following exceptions. The nucleotide sequence of metQ (ngo2139) was used to query the public Neisseria multilocus sequence typing database (Neisseria pubMLST; [35]; https://pubmlst.org/neisseria/) to identify metQ alleles and nucleotide polymorphic sites across 4,421 isolates of N. gonorrhoeae for which metQ sequence data exist, as well as among all Neisseria isolates present in the database (21,798 isolates with metQ sequence data as of March 26, 2020). Translated amino acid sequences were aligned with Muscle in Geneious Prime 2020.1.2. Alignments were used to generate a Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree using the Jukes-Cantor genetic distance model. Amino acid polymorphisms were mapped to crystal structures of the Nm MetQ homolog, GNA1946. The amino acid sequences of structures solved with L-methionine [6OJA; [36]] or in the substrate-free conformation [6CVA; [36]] were aligned against all Ng MetQ amino acid sequences as above. Polymorphic sites were identified and their prevalence was calculated by dividing the number of isolates associated with each polymorphism by the total number of isolates. The single polymorphic site found in >1% of the global Ng population was then mapped to the crystal structure using PyMOL (https://pymol.org/2/).

Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism was used for all statistical analyses. The built-in t-test was utilized to determine statistically significant differences between experimental results with the exception of animal studies and ELISA, which were analyzed as described above. A confidence level of 95% was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

MetQ is highly conserved among Neisseria.

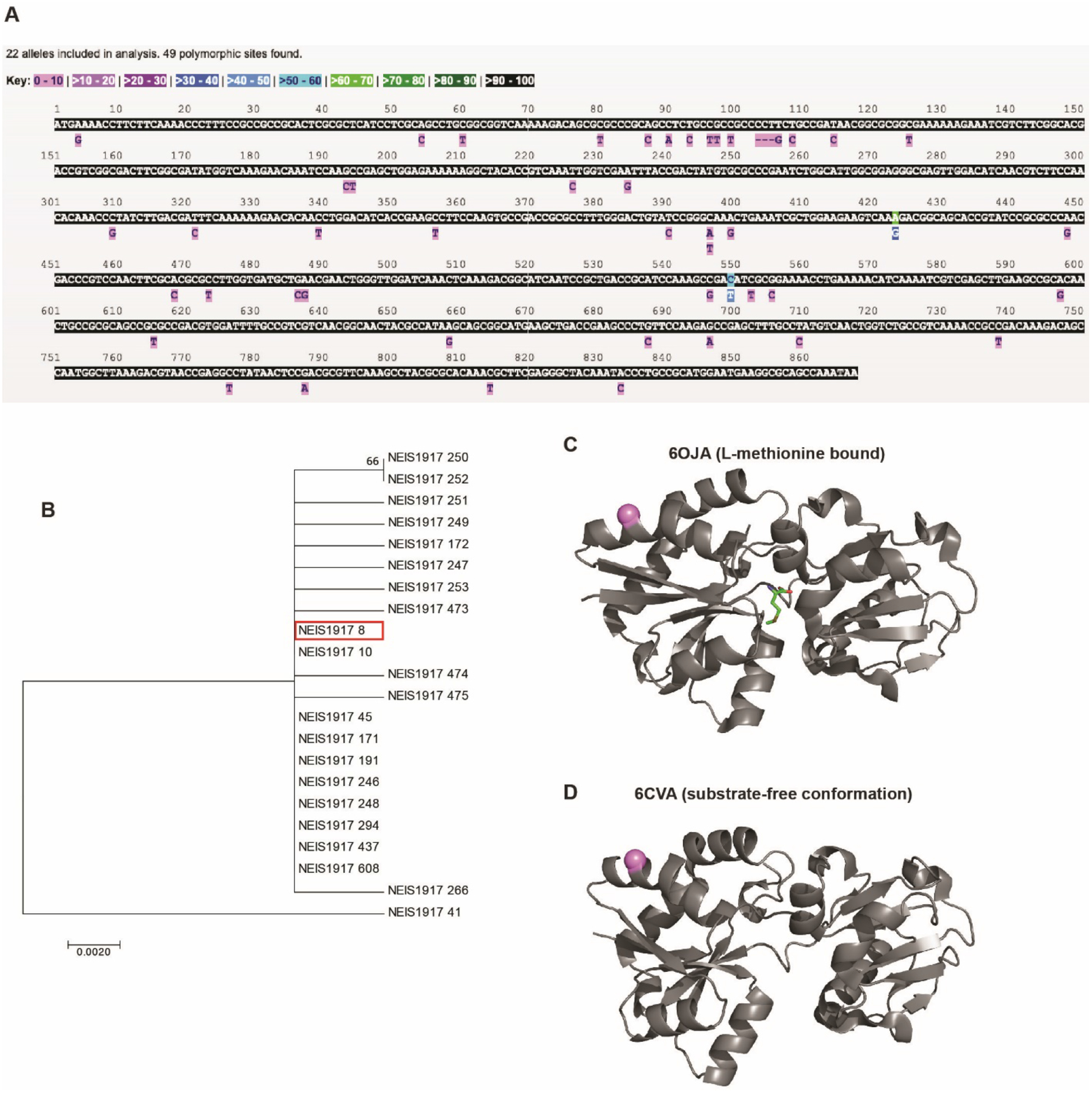

We previously analyzed MetQ polymorphic sites between 36 genetically and temporally diverse Ng isolates including the 2016 World Health Organization reference strains. MetQ had only 2 (0.23%) and 0 variations at the DNA and protein levels, respectively, and was the most conserved vaccine antigen compared to LptD, BamA, TamA, and NGO2054 [13]. To further explore the feasibility of MetQ as an effective vaccine target, we first comprehensively examined the prevalence of this antigen and its sequence variability using all available Neisseria genome sequences deposited to the PubMLST database and their predicted amino acid sequences. Overall, these investigations corroborated that MetQ is highly conserved, with 22 alleles among 4,421 Ng isolates, which accounted for 49 nucleotide polymorphic sites and 17 amino acid polymorphisms (Fig. 1a). Remarkably, a single amino acid sequence, represented by 10 of the 22 alleles, accounts for nearly 97% of metQ sequence variation across the Ng isolates deposited in the database (Table S1). A phylogenetic analysis indicated that all of the metQ alleles were closely related, with the exception of allele 41, which formed an outgroup (Fig. 1b). Polyclonal rabbit antisera elicited by recombinant MetQ (rMetQ) representing allele 8 (Ng FA1090) previously detected MetQ in whole-cell lysates of diverse Ng isolates. Together, these data confirm the ubiquitous nature of this antigen and the conservation of immunogenic epitopes [13].

Figure 1. Conservation of Ng MetQ and mapped amino acid polymorphic sites.

(A) Nucleotide polymorphic sites in the metQ locus (NEIS1917) across 4,421 N. gonorrhoeae isolates with metQ sequence data deposited into the Neisseria PubMLST database. (B) A Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree was constructed for metQ alleles in Geneious using the Jukes-Cantor genetic distance model. The FA1090 allele (8) is highlighted in red. (C, D) The single Ng MetQ amino acid polymorphism found in >1% of the global Ng population was mapped to crystal structures of Nm MetQ using PyMol. The light purple sphere indicates position 65, which is polymorphic in 2.65% of isolates. Structures collected with L-methionine (PDB ID: 6OJA; C) or in the substrate-free conformation (PDB ID: 6CVA; D) are presented. L-methionine is shown in green in the MetQ active site in the L-methionine-bound structure.

A subsequent broader investigation (n=21,798) of other Neisseria isolates with metQ sequence information revealed 415 metQ alleles, which accounted for 645 and 194 nucleotide and amino acid polymorphic sites, respectively (Fig. S1). Similar to Ng, metQ alleles across Neisseria were closely related, with the exception of 13 sequences which clustered separately from the rest of the tree (Fig. S2).

To facilitate future structural vaccinology efforts, we next mapped the most prevalent gonococcal polymorphic amino acids to Nm MetQ crystal structures both with and without L-methionine in the binding site (6OJA and 6CVA, respectively [36]). Of the 11 polymorphisms encompassed by the crystal structures, only one site (A65) diverged from the most common MetQ variant in 2.65% of isolates worldwide. The remaining polymorphisms were found in less than 1% of Ng MetQ amino acid sequences. (Fig. 1c, D). Supplemental Videos 1–4 show rotations of both crystal structures (L-methionine-bound and substrate-free) with the mapped polymorphic site to demonstrate its relationship to the active site and the rest of the protein in 3D space. Six polymorphic sites outside of the crystal structure [the crystal structure sequence starts at site 44, and the polymorphisms are at sites 2, 27, 33, 35 (gap site), 36, and 42] are also found in fewer than 1% of Ng isolates.

These investigations – performed, to our knowledge, for the first time on a large scale – demonstrate the exceptionally high level of MetQ conservation and strongly support its inclusion in a broad-spectrum gonorrhea vaccine.

MetQ is expressed in vivo but does not confer a detectable advantage during competitive murine infection.

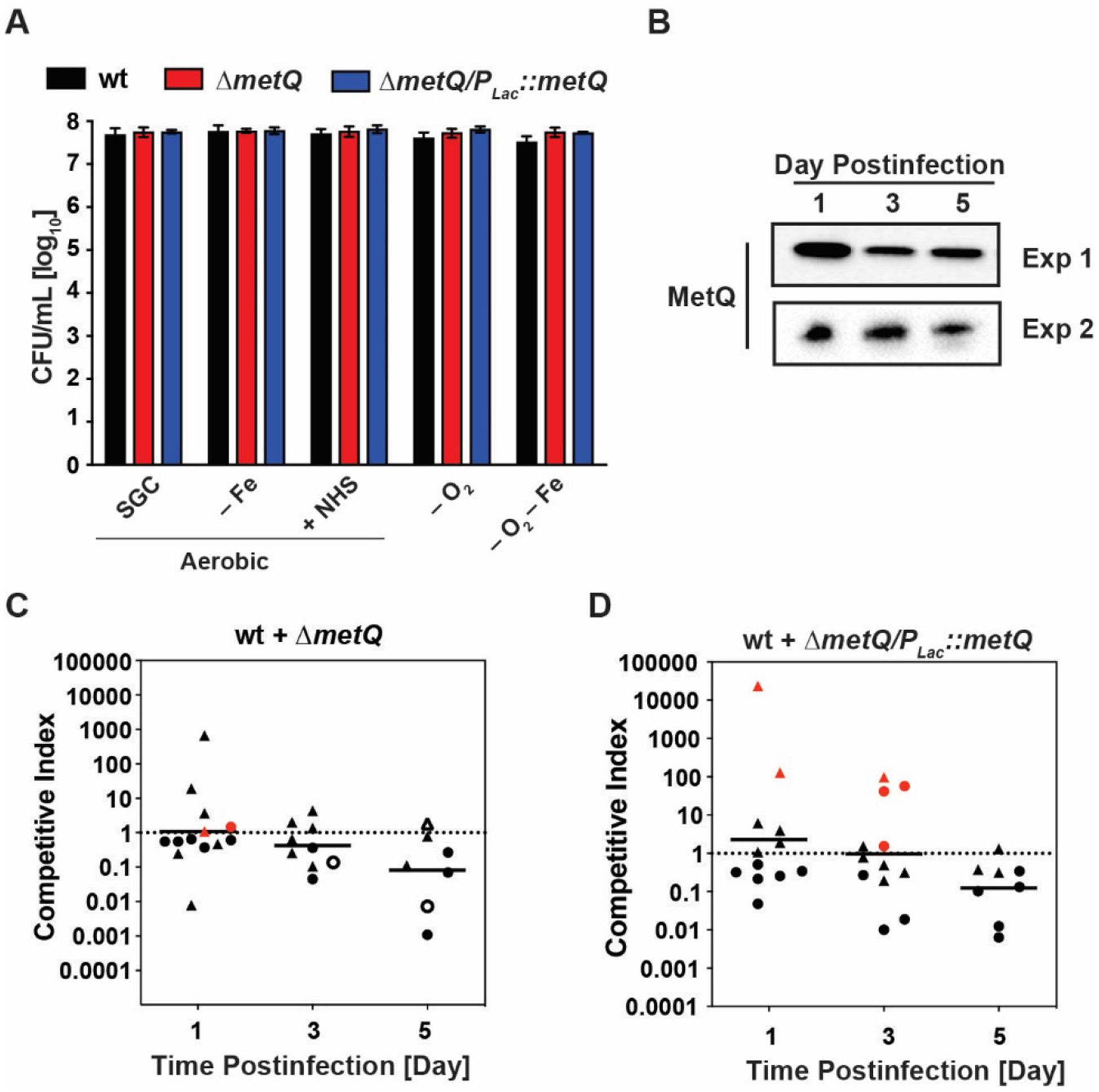

Prokaryotic lipoproteins play versatile functions ranging from cell envelope stability to nutrient acquisition, substrate binding for ABC transporter systems, modulation of the host immune system, signal transduction, and virulence [4, 8]. In addition to its predicted role in bacterial physiology as a methionine transporter, MetQ may contribute to gonococcal pathogenesis based on findings that a Ng ΔmetQ mutant was attenuated during exposure to primary monocytes, activated macrophages, 40 and 80% of complement-active normal human serum in bactericidal assay, and was less able to adhere to and invade human cervical epithelial cells [14]. These observations prompted us to further explore phenotypes associated with deletion of metQ using previously constructed a null mutant in ngo2139 (ΔmetQ) and its complemented mutant ΔmetQ/Plac::metQ in Ng FA1090 [13]. We first examined whether complete elimination of MetQ affects cell envelope homeostasis by exposing bacteria to seven antibiotics with different mechanisms of action using Etest assays. These studies showed that Ng lacking MetQ had the same susceptibility as the parental strain (Table S2), suggesting that this lipoprotein has no significant function in cell envelope stability. Subsequently, we investigated the role of MetQ during conditions that mimic environmental microniches in the host by exposing WT, ΔmetQ, and the complementation strain ΔmetQ/Plac::metQ to iron limitation, anaerobiosis, and a combination of iron deficiency and anoxia. Simultaneous experiment included addition of human serum in solid media to test the influence of its multiple components comprising of proteins and peptides, lipid fatty acids, and over four thousand small molecule metabolites [37]. Loss of MetQ did not significantly alter bacterial viability as assessed by comparing the number of colony forming units (CFU) of the mutant and WT strains following exposure to the conditions examined (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. MetQ is expressed during Ng infection in the murine lower reproductive tract but is dispensable for bacterial fitness.

(A) Rapidly growing liquid cultures of strains indicated above the graph were standardized, diluted, and spotted onto solid media for standard growth conditions (SGC), iron limiting conditions (− Fe), presence of 7.5% normal human serum (NHS), anaerobic conditions (− O2), and anaerobic conditions combined with iron limitation (− O2 − Fe). CFUs were scored following 22 h incubation. n = 3; mean ± SEM. (B) Vaginal washes from five experimentally infected female BALB/c mice inoculated with WT Ng FA1090 were collected on days 1, 3, and 5 post-inoculation in two independent experiments and pooled washes from each experiment were probed with anti-MetQ antiserum. The amount of sample loaded onto SDS-PAGE was normalized based on the number of gonococcal CFUs recovered from the washes. (C, D) Competitive infections between WT bacteria and either the ΔmetQ mutant (C) or the complementation strain ΔmetQ/Plac::metQ (D) were performed by inoculating female BALB/c mice intravaginally with approximately equal numbers of each strain (~106 CFU/dose). Vaginal swabs were collected on days 1, 3, and 5 post-infection and enumerated on medium containing streptomycin (total bacteria) or streptomycin and kanamycin (mutant bacteria). The competitive index (CI) was calculated as described in the main text. Experiments were performed on two separate occasions, distinguished by circular or triangular symbols, with six mice per group, and the geometric mean of the CI is presented. The assay’s limit of detection of 1 CFU was assigned for any strain not recovered from an infected mouse. Statistical analysis was executed using Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparison tests to compare statistical significance of CIs between ΔmetQ/WT and ΔmetQ/Plac::metQ/WT competitions. Red symbols designate mice from which no WT bacteria were recovered, while open symbols signify that no mutant CFU were recovered.

Our prior studies demonstrated that MetQ is ubiquitously expressed in vitro [13, 38], however, its cellular pools during infection have not been investigated. Therefore, we next infected female BALB/c mice with WT FA1090 and collected vaginal washes at days 1, 3, and 5 post-infection in biological duplicate experiments. Samples containing equal numbers of CFUs were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-MetQ antisera. MetQ was readily detectable at each point examined during the infection period (Fig. 2b), indicating that MetQ expression in vivo is relatively stable.

Finally, to assess whether MetQ provides Ng with a fitness advantage during murine infection, we performed competitive infection experiments in which mice were inoculated vaginally with similar numbers of WT FA1090 mixed with either the ΔmetQ mutant or the ΔmetQ/Plac::metQ. The expression from the lac promoter during Ng infection in the murine lower genital tract has been documented [39], warranting the use of the complemented strain. The calculated competitive indices (CIs) for ΔmetQ/WT were 1.09, 0.42, and 0.08 (geometric means of biological duplicate experiments) on day 1, 3, and 5 post-infection, respectively (Fig. 2c). A similar decrease in CI over time was observed for the ΔmetQ/Plac::metQ/WT competition (Fig. 2 d). Statistical comparison of the CIs between the ΔmetQ/WT and ΔmetQ/Plac::metQ revealed no significant differences. Calculated p values for competition experiments conducted in vitro were also not significant (Fig. S3).

Based on these studies, we conclude that MetQ is expressed in vivo but does not provide an advantage in vitro under tested conditions or survival advantage during mucosal infection in the lower genital tract of female mice.

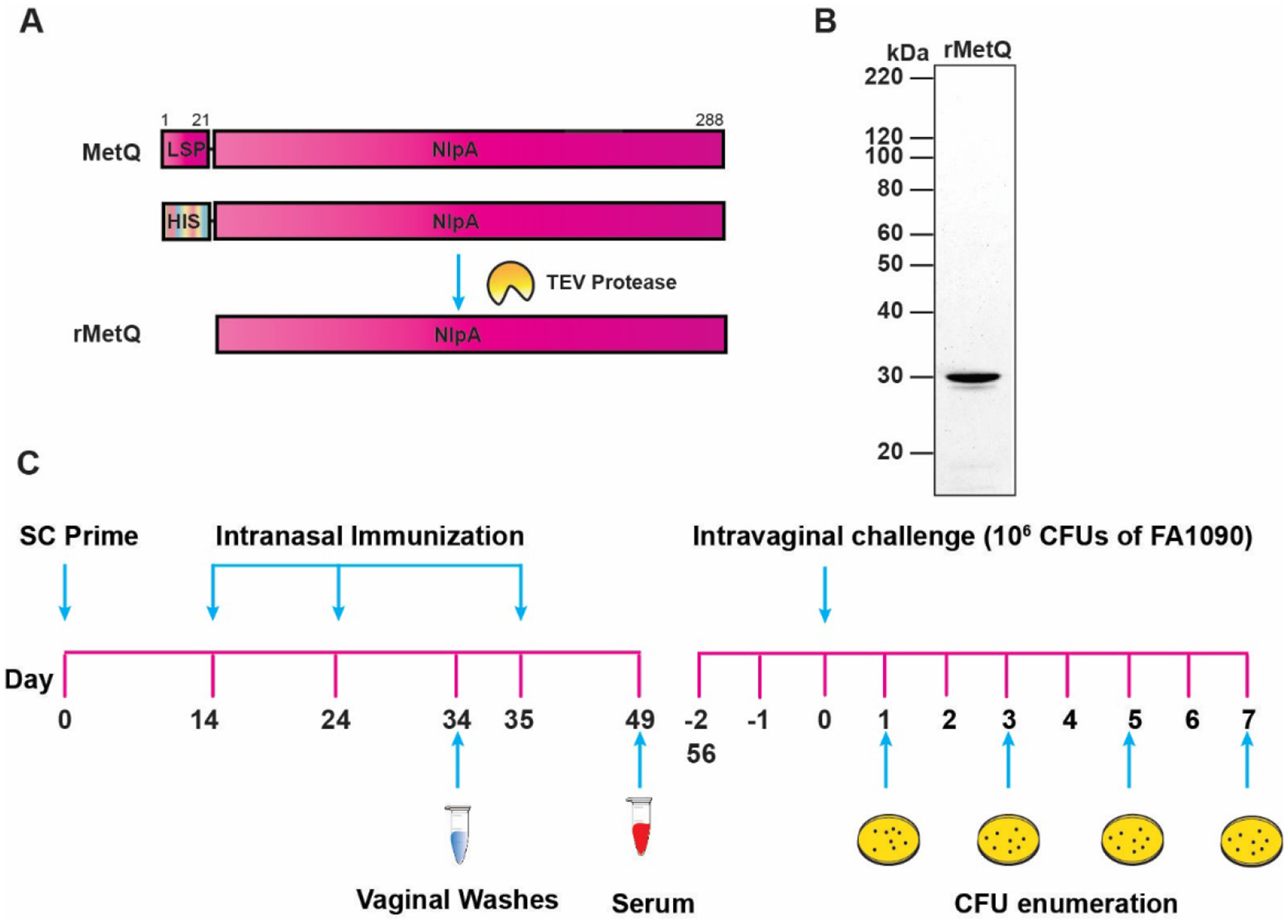

Rationale for immunization and challenge study design.

To appraise MetQ as a component of gonorrhea subunit vaccine, we designed a recombinant protein construct using the most prevalent allele (Table S1), by replacing the MetQ lipoprotein signal peptide with an N-terminal 6×histidine tag (Fig. 3a). A highly pure untagged rMetQ antigen that migrated on SDS-PAGE with a molecular weight of ~30 kDa, consistent with the size of mature MetQ (29.87 kDa), was obtained after two-step chromatography followed by Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease cleavage (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Experimental design of immunization/challenge experiments and MetQ antigen design.

(A) To generate rMetQ antigen, the metQ gene, encoding a full-length MetQ protein, was engineered to produce a recombinant protein that lacks the signal sequence and carries an N-terminal 6×His-tag followed by a Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease cleavage site. (B) Soluble rMetQ was purified to homogeneity through several chromatography steps and migrated on SDS-PAGE at approximately 29.87 kDa, consistent with the predicted molecular mass of mature MetQ, as revealed by SYPRO Ruby staining. Untagged rMetQ was used in immunization studies as shown in panel C. (C) Female BALB/c mice were randomized into three experimental groups (n = 20/group) and given rMetQ-CpG, CpG, or PBS (unimmunized) subcutaneously on day 0, followed by three nasal boosts on days 14, 24 and 35. Vaginal washes were collected 10 days after the second immunization (d34) and serum was collected after the final immunization (day 49) to avoid disruption of the vaginal microenvironment prior to bacterial challenge. Three weeks after the final immunization (d 56 or d-2), only mice that entered into the diestrus or anestrus stage (n - number of animals indicated) were treated with 17β-estradiol and antibiotics and challenged with 106 CFU of Ng FA1090 two days later (day 0). Vaginal swabs were quantitatively cultured for Ng on days 1, 3, 5, and 7 post-bacterial inoculation.

We formulated rMetQ with CpG as an adjuvant based on the limited number of in vivo protection studies conducted, which suggest a Th1 response is associated with accelerated Ng clearance [40–44]. Initially, we conducted a pilot study by immunizing groups of 5 BALB/c mice with rMetQ, rMetQ-CpG, CpG, or PBS using a subcutaneous prime injection, followed by a regimen of three intranasal boost doses. This immunization strategy was selected to promote both systemic and mucosal immune responses. A robust, single protein band corresponding to the molecular weight of rMetQ (~30 kDa) was detected in immunoblots with serum from mice immunized with rMetQ alone and rMetQ-CpG, but not from control animals (Fig. S4). Based on these encouraging results, we performed two large-scale immunization/challenge experiments. To ensure sufficient statistical power for preclinical vaccine research, cohorts (n=20/group) of BALB/c mice were given rMetQ formulated with CpG, adjuvant alone, or PBS and challenged vaginally with wild type FA1090 Ng three weeks after the final immunization as described [32, 33]. Bacterial clearance was assessed by enumerating Ng CFUs present in vaginal washes on days 1, 3, 5, and 7 post-infection (Fig. 3c). Infection duration and bacterial burden were compared between immunized and control groups (Figs. 4 and S5). To evaluate the antigen-specific immune responses elicited, vaginal washes and sera collected after the second boost and 14 days after the third boost, respectively, were subjected to immunoblotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, ELISA (Figs. 5–6).

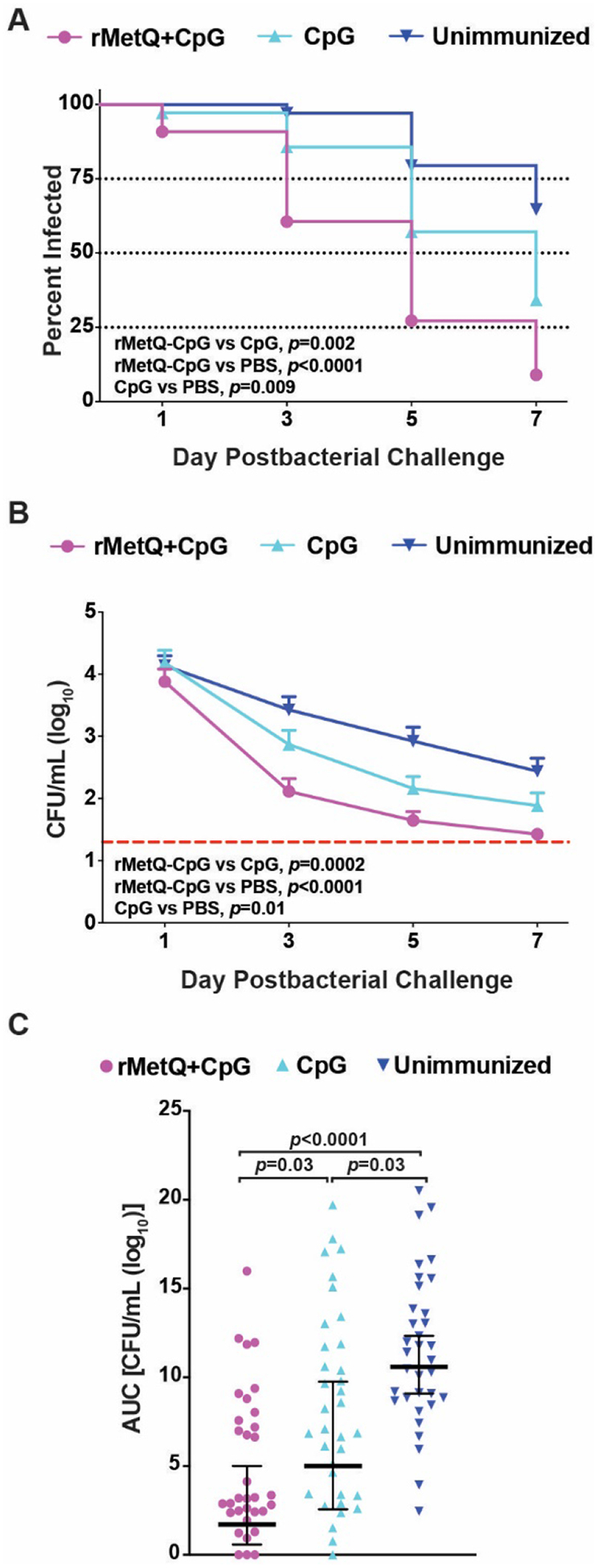

Figure 4. Mice immunized with rMetQ-CpG clear infections significantly faster following vaginal challenge with Ng.

Groups of BALB/c mice were immunized with rMetQ-CpG or given CpG (adjuvant) alone or PBS (unimmunized) as per the immunization regimen shown in Fig. 3. Subsequently, mice in the diestrus stage or in anestrus were treated with 17β-estradiol and antibiotics and challenged with 106 CFU of strain FA1090 three weeks after the final immunization (n=16–18 mice/group). Vaginal washes were quantitatively cultured for N. gonorrhoeae on days 1, 3, 5 and 7 post-bacterial challenge. (A) The percentage of mice with positive vaginal cultures was plotted over time as Kaplan Meier curves and the results analyzed by the Log Rank test. (B) The average number of CFU recovered from each experimental group was plotted over time. The limit of detection was 20 CFU/mL of vaginal swab suspension. This value was used for mice with negative cultures. Differences in colonization load were assessed by a repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis for multiple pairwise comparisons. (C) AUC (log10 CFU/mL) analysis of murine colonization. Data are presented for individual mice. Horizontal bars represent the geometric mean of the data with the 95% confidence interval. Data shown are combined data from two independent experiments.

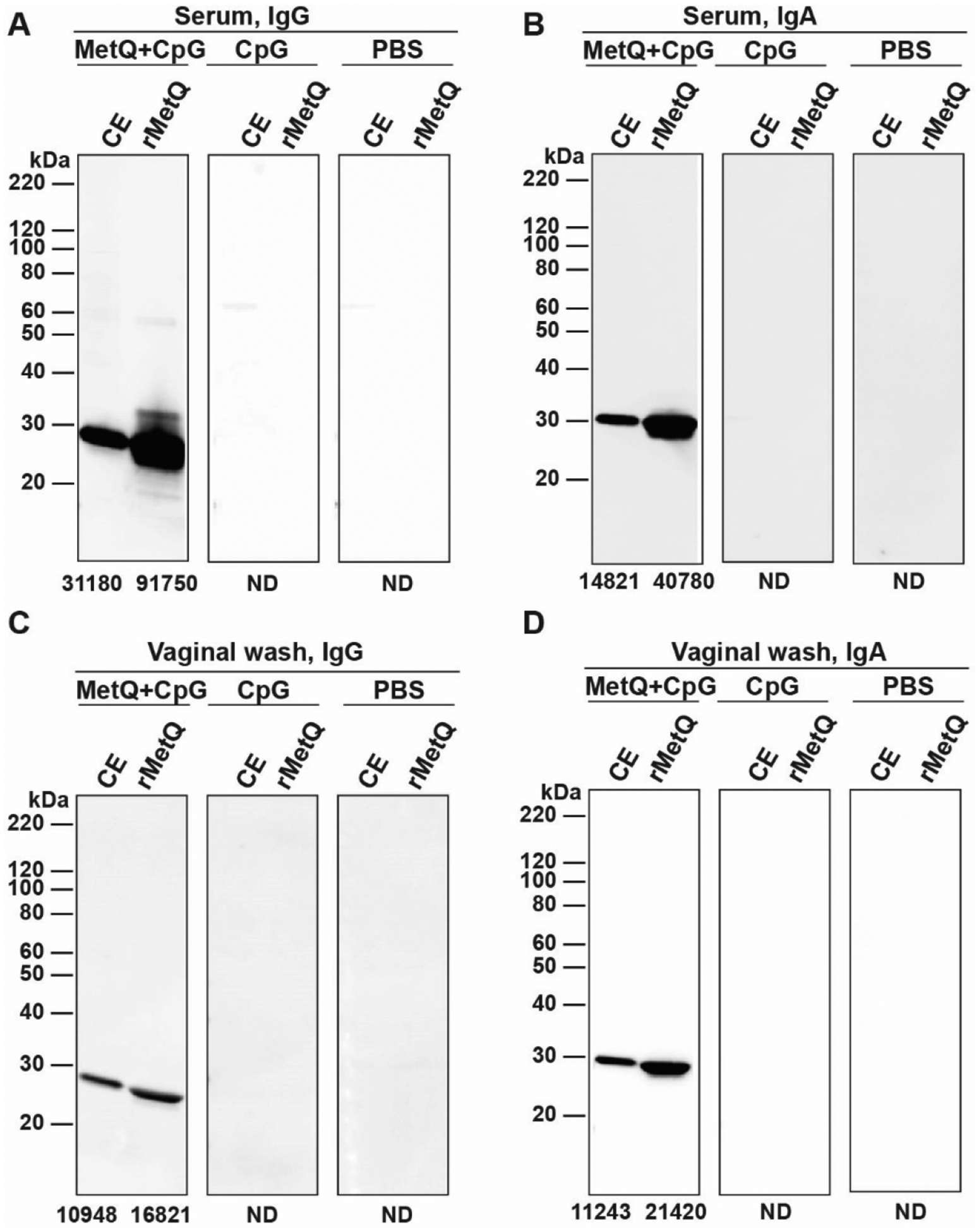

Figure 5. MetQ-specific serum IgG and vaginal IgG and IgA are induced by rMetQ-CpG.

Female mice were immunized with rMetQ-CpG, CpG, or PBS in immunization/challenge studies. Total cell envelope (CE) proteins from Ng FA1090 and rMetQ were fractionated by SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting was performed with pooled serum (A, B) and vaginal washes (C, D) collected after the third immunization, followed by secondary antibodies against mouse IgG (A, C) or IgA (B, D). The intensity of the bands was measured by Fiji software [62] and the value is recorded under each lane. ND-not detected.

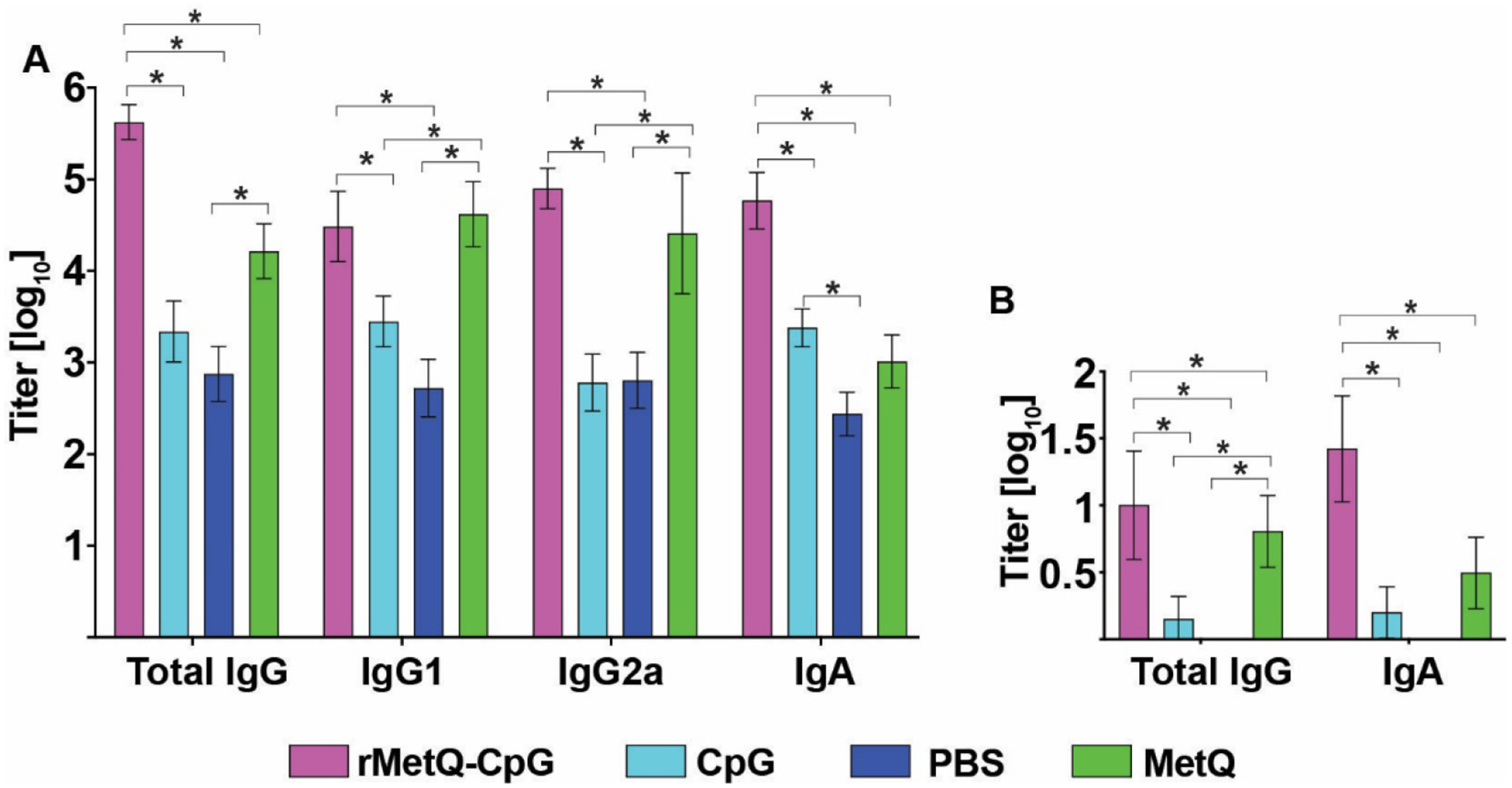

Figure 6. Anti-MetQ antibody titers elicited by rMetQ and rMetQ-CpG immunization.

(A) Post-immunization (d49) total IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgA antibody titers in sera from mice immunized with rMetQ, rMetQ-CpG, CpG, or unimmunized. (B) Post-immunization (d34) vaginal secretions from mice immunized with rMetQ, rMetQ-CpG, CpG, or unimmunized were examined for total IgG and IgA antibodies. Bar graphs represent geometric mean ELISA titers with error bars showing 95% confidence limits. Statistical significance between data in groups was determined using Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparison test; *p<0.05.

Immunization with rMetQ-CpG accelerates clearance from experimentally challenged mice.

The combined data for the two independent rMetQ-CpG vaccine immunization/challenge experiments are shown in Fig. 4. Mice immunized with rMetQ-CpG cleared the infections significantly faster than those given PBS (p<0.0001) or adjuvant alone (p=0.002; Fig.4a). CpG regimen resulted in significant (p=0.009) reduction in duration of infection compared to placebo group. Importantly, by day 5 and 7 post-challenge, 72.8 and 90.9% of mice that received rMetQ-CpG cleared gonorrhea infection, compared to 42.8 and 65.7% for CpG-inoculated animals and 20.6 and 35.3% in the unimmunized group, respectively. The gonococcal cumulative burden was also considerably lower in rMetQ-CpG immunized mice in comparison to mice given either CpG or PBS (p=0.03 and p<0.0001, respectively; Fig. 4b, c). Further, an area under the curve (AUC) analyses showed a 2-fold difference in cumulative burden between adjuvant and PBS-treated mice (p=0.03; Fig. 4c). In the supplemental Fig. S5, we presented individual immunization/challenge studies. In the first experiment, faster clearance was observed in the rMetQ-CpG cohort compared to the CpG- and unimmunized-groups (p=0.004 and p<0.0001, respectively; Fig. S5a). Mice that received rMetQ-CpG had a 4- and 10-fold lower AUC than mice given either CpG or PBS (p>0.9 and p=0.0006, respectively; Fig. S5c). Duration of infection, gonococcal bioburden, and AUC were significantly decreased in adjuvant-treated group compared to unimmunized mice (p=0.046, p=0.03 and p=0.01, respectively; Fig. S5). In the repeat experiment, an additional cohort of mice received rMetQ alone as our preliminary studies suggested that this antigen is a strong immunogen on its own (Fig. S4). The percentage of culture-positive mice over time showed that rMetQ-CpG-immunized mice had a significantly faster clearance rate compared to mice given rMetQ (p=0.02) or PBS (p=0.001) but not adjuvant alone (Fig. S5d). The cumulative burden of infection over time was significantly lower in rMetQ-CpG-immunized mice compared to the rMetQ-, CpG- and PBS-groups (p=0.005, p=0.03 and p=0.003, respectively; Fig. S5f). No significant differences were observed in CpG-treated mice compared to mice that received PBS (Fig. S5d–f). A cohort of mice given rMetQ showed no difference in the clearance rate or bioburden compared to control groups (Fig. S5 d–f). Based on these studies, we conclude that formulation with CpG is required for MetQ to confer protection.

rMetQ-CpG elicits prominent antigen-specific immune responses.

To comparatively assess the specificity and isotype profiles of antibody responses elicited by rMetQ-CpG vaccination, we performed immunoblotting and ELISA using serum and vaginal washes derived from all cohorts of animals (Figs. 5–6). Serum and vaginal IgG and IgA (Fig. 5a, c and 5b, d; respectively) obtained from mice that received rMetQ-CpG readily recognized both purified rMetQ immunogen and native MetQ in Ng cell envelopes (CE). No signal, however, was detected after blotting the membranes with serum or vaginal washes from CpG- or PBS-immunized mice. Visual and densitometric inspection indicated relative MetQ intensities were lower in samples probed with vaginal secretions than with serum (Fig. 5 a–b versus c–d). Notably, although MetQ relative intensities detected with serum IgG were higher than IgA for CE samples (IgG is 2.24-fold higher), vaginal IgA and IgG reacted similarly with MetQ. Together, these experiments demonstrated that immunization of mice with rMetQ-CpG induces antigen-specific IgG and IgA immune responses that are both systemic and, critically, at the genital mucosae.

Analyses of the combined ELISA data showed that total serum IgG and IgA titers in mice immunized with rMetQ-CpG were significantly higher than in mice that received rMetQ alone, adjuvant alone, or PBS (Fig. 6a, Table S3). The calculated geometric mean of total IgG in mice immunized with rMetQ-CpG was 4.2×105 in comparison to 1.65×104, 2.2×103 and 7.5×102 in mice that received rMetQ, CpG, and PBS, respectively. Immunization with rMetQ alone, in comparison to rMetQ-CpG, resulted in similar induction of IgG1 (4.2×104 and 3.1×104; respectively) and IgG2a antibody responses (2.6×104 and 8.0×104; respectively) that were significantly greater than in mice immunized with CpG and PBS. However, the IgG1/IgG2a ratio was lower (0.38) in mice given rMetQ formulated with CpG compared to rMetQ alone (1.6), suggesting a slight systemic bias toward a Th1 response in the protected group, consistent with the activity of CpG as a Th1-stimulating adjuvant. The serum IgA titers were 57.4-, 24.6-, and 214-fold higher in rMetQ-CpG-immunized mice than in rMetQ, CpG and PBS groups, respectively (Table S3). While minimal IgG and IgA antibody responses were detected in vaginal secretions from unimmunized- and CpG-treated cohorts, rMetQ-CpG vaccination gave significant ~10 and 16-fold increases in IgG (10.02; geometric mean) and IgA (26.42; geometric mean) titers, respectively (Fig. 6b, Table S3). Although immunization with rMetQ alone resulted in a significant increase in MetQ-specific mucosal IgG response (6.3; geometric mean), the levels of IgA were not statistically greater than in control groups. Cumulatively, these analyses demonstrated that rMetQ-CpG formulation elicits significantly high systemic and mucosal antibody titers suggestive of a Th1 response, as predicted by relative serum IgG2a and IgG1 immunoglobulin isotype titers.

We conclude that rMetQ formulated with CpG induces a protective immune response that accelerates Ng clearance from the murine lower genital tract, and that while rMetQ alone prompts high serum and vaginal antibody responses, rMetQ-CpG increases total IgG and IgA antibodies in serum and vaginal mucosae and skews the immune response towards Th1 response.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, an increasing number of reports have evaluated the ability of gonorrhea vaccine candidates to elicit immune responses in laboratory animals. However, very few reports examined their capacity to induce protective responses that would enhance clearance and shorten the duration of infection [21]. Accordingly, with this study, we have examined the immune response and protective capability of a lipoprotein antigen discovered through reverse vaccinology: MetQ (NGO2139; [13, 14, 27, 29]). In light of the extensive surface protein variability inherent to Ng, highly conserved antigens should be selected to provide broad vaccine coverage. Our in-depth bioinformatics illustrates that MetQ is a desirable antigen based on its conservation: the MetQ amino acid sequence is identical in nearly 97% of Ng isolates globally (Fig. 1, Table S1). Among the 17 amino acid polymorphisms, single changes are found in 0.02–2.7 % of isolates and a single allele with 8 divergent amino acids is present in only 0.05% of isolates. Consequently, vaccination with the single most prevalent MetQ variant will likely provide broad protection against the majority of Ng encountered worldwide. Additionally, prior analysis of the Nm homolog, GNA1946, in 97 isolates revealed the existence of only 20 different alleles with 23 and 5 polymorphic nucleotide and amino acid sites, respectively [45]. In combination with our bioinformatic analyses (Figs. S1 and S2), conservation data from Nm suggest that MetQ may be a suitable antigen for a universal Neisseria vaccine. Most importantly our immunization/challenge studies showed that rMetQ-CpG vaccination both significantly accelerated clearance and reduced bacterial burden in infected animals compared to CpG-only and PBS control (Fig. 4).

We found that the addition of CpG was critical to promote a protective response with the rMetQ immunogen and that CpG alone provided protection against Ng infection compared to unimmunized and rMetQ-immunized animals (Fig. 4 and Fig. S5). Similar protection against gonorrhea was also seen with viral replicon particles [46]. Our unpublished data has indicated that the amount of CpG used in this study (25 μg) shortens gonococcal infections in the absence of an antigen, likely by triggering a Th1 response and activating the immune system before it is challenged with Ng. In support of this hypothesis, mice immunized intranasally solely with CpG prior to pulmonary challenge with the lethal bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei survived significantly longer than naïve animals or those treated with a control oligodeoxynucleotide. Additionally, animals immunized with attenuated bacteria and treated with CpG showed increased survival compared to either treatment alone. A short-term elevation in lung IFN-γ, accompanied by recruitment of macrophages and natural killer cells, was also observed [47]. CpG treatment alone is protective against a number of intracellular and mucosal pathogens. This protection is strongly correlated to IL-12 and IFN-γ production [48–52]. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides resemble bacterial DNA and provoke an immune response. Their mechanism of action relies on the stimulation of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9, which is primarily expressed in human B cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs). Upon CpG-induced TLR 9 activation, both B cells and pDCs upregulate expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules and release cytokines that signal naïve T cells to differentiate to Th1 cells. B cells then differentiate into either plasma cells or memory cells, while pDCs also differentiate to a stage where antigen processing and presentation are enhanced [53]. The ability of CpG to augment antigen presentation through DCs may therefore overcome the antigen presentation restriction Ng imposes on macrophages [54, 55]. The multi-target mechanism of CpG action is also consistent with data that indicated Th1 and B cell responses were both important for immune memory against gonorrhea [43]. Wild type mice administered IL-12 during infection were able to clear repeat infections more quickly than untreated mice. In contrast, B cell-deficient mice were impaired in their ability to clear the repeat infection [43]. In our experiments, mice cohorts that received rMetQ-CpG developed a robust, MetQ-specific antibody responses in both serum and female mouse genital tract (Figs. 5, 6). The presence of antigen-specific IgA and IgG in the vaginal mucosae is promising, as it suggests that vaccination would result in an antibody response at the site of infection. Together, these data suggest the induction of IgA and a Th1 responses are likely to be important for effective gonococcal clearance. This conclusion is supported by studies with experimental vaccines formulated with Th1-inducing adjuvants or delivery systems [40–42, 44].

The data presented here warrant further development of rMetQ as a gonorrhea vaccine candidate. Subunit vaccines are attractive for their safety, stability, and defined composition. One of the two available licensed serogroup B Nm vaccines, Trumenba (Pfizer), is a subunit vaccine that contains two factor H binding protein variants, which were identified through reverse vaccinology [56]. Although Trumenba demonstrates that a single-component subunit vaccine can be successful, to provide superior immune responses against the sophisticated Ng, a cocktail vaccine with several other highly conserved surface antigens is likely needed. The current renaissance in the gonorrhea vaccine field brings optimism for generating a much needed, effective gonorrhea vaccine by advancing vaccine workflows to preclinical and clinical trials, discovering conserved immunogens, and illuminating new concepts to counteract the ways Ng subverts the immune system [54, 55, 57–61].

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Movie S1. Ng amino acid polymorphism mapped to Nm MetQ crystal structure bound to L-methionine, rotated about the X axis. Movie generated in PyMol.

Supplemental Movie S2. Ng amino acid polymorphism mapped to Nm MetQ crystal structure bound to L-methionine, rotated about the Y axis. Movie generated in PyMol.

Supplemental Movie S3. Ng amino acid polymorphism mapped to Nm MetQ crystal structure in the substrate-free conformation, rotated about the X axis. Movie generated in PyMol.

Supplemental Movie S4. Ng amino acid polymorphism mapped to Nm MetQ crystal structure in the substrate-free conformation, rotated about the Y axis. Movie generated in PyMol.

Supplemental Figure S1. metQ nucleotide variation across Neisseria genus.

Supplemental Figure S2. Phylogenetic analysis of MetQ variation among Neisseria.

Supplemental Figure S3. In vitro competition assay.

Supplemental Figure S4. Immunization with rMetQ alone or with CpG induces antigen-specific immune response.

Supplemental Figure S5. Infection dynamics from individual rMetQ-CpG immunization experiments. In the first immunization/challenge experiment cohorts of BALB/c mice were immunized with rMetQ-CpG, CpG, or PBS (A, B, C). The second experiment consisted of groups that were given rMetQ, rMetQ-CpG, CpG, or PBS (D, E, F) as per the immunization regimen shown in Fig. 3. Mice in the diestrus stage or in anestrus were treated with 17β-estradiol and antibiotics and challenged with 106 CFU of strain FA1090 three weeks after the final immunization. Vaginal washes were quantitatively cultured for Ng on days 1, 3, 5 and 7 post-bacterial challenge. (A, D) The percentage of mice with positive vaginal cultures was plotted over time as Kaplan Meier curves and the results analyzed by the Log Rank test. (B, E) The average number of CFU recovered from each experimental group was plotted over time. The limit of detection was 20 CFU/mL of vaginal swab suspension. This value was used for mice with negative cultures. Differences in colonization load were assessed by a repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis for multiple pairwise comparisons. (C, F) AUC (log10 CFU/mL) analysis of murine colonization. Data are presented for individual mice. Horizontal bars represent the geometric mean of the data with the 95% confidence interval.

Supplemental Table S1. Analysis of MetQ alleles and number of Ng isolates per allele grouping.

Supplemental Table S2. Etest antibiotic susceptibility experiments.

Supplemental Table S3. Geometric means antibody titers measured in serum and vaginal washes on days 34 and 49, respectively, since the SC immunization.

Geometric mean titers of antibodies against purified rMetQ were determined as described in Materials and Methods.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Kristie Connolly (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) for helpful discussion regarding immunization/challenge experiments.

FUNDING

Funding was provided to AES by grant R01-AI117235 from the National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leng CH, et al. , Recombinant bacterial lipoproteins as vaccine candidates. Expert Rev Vaccines, 2015. 14(12): p. 1623–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradshaw WJ, et al. , Molecular features of lipoprotein CD0873: A potential vaccine against the human pathogen Clostridioides difficile. J Biol Chem, 2019. 294(43): p. 15850–15861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choh LC, et al. , Burkholderia vaccines: are we moving forward? Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2013. 3: p. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovacs-Simon A, Titball RW, and Michell SL, Lipoproteins of bacterial pathogens. Infect Immun, 2011. 79(2): p. 548–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henneke P, et al. , Lipoproteins are critical TLR2 activating toxins in group B streptococcal sepsis. J Immunol, 2008. 180(9): p. 6149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buddelmeijer N, The molecular mechanism of bacterial lipoprotein modification--how, when and why? FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2015. 39(2): p. 246–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakayama H, Kurokawa K, and Lee BL, Lipoproteins in bacteria: structures and biosynthetic pathways. FEBS J, 2012. 279(23): p. 4247–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayashi S and Wu HC, Lipoproteins in bacteria. J Bioenerg Biomembr, 1990. 22(3): p. 451–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson MM and Bernstein HD, Surface-Exposed Lipoproteins: An Emerging Secretion Phenomenon in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Trends Microbiol, 2016. 24(3): p. 198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konovalova A and Silhavy TJ, Outer membrane lipoprotein biogenesis: Lol is not the end. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2015. 370(1679): p. 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bae K, et al. , Innovative vaccine production technologies: the evolution and value of vaccine production technologies. Arch Pharm Res, 2009. 32(4): p. 465–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer NO, et al. , Conjugation to nickel-chelating nanolipoprotein particles increases the potency and efficacy of subunit vaccines to prevent West Nile encephalitis. Bioconjug Chem, 2010. 21(6): p. 1018–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zielke RA, et al. , Proteomics-driven Antigen Discovery for Development of Vaccines Against Gonorrhea. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2016. 15(7): p. 2338–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semchenko EA, Day CJ, and Seib KL, MetQ of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Is a Surface-Expressed Antigen That Elicits Bactericidal and Functional Blocking Antibodies. Infect Immun, 2017. 85(2): p. 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowley J, et al. , Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull World Health Organ, 2019. 97(8): p. 548–562P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC. 2018 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance. 2019. 2019-10-09T12:34:07Z; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/default.htm.

- 17.Magidson JF, et al. , Relationship between psychiatric disorders and sexually transmitted diseases in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 2014. 76(4): p. 322–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rice PA, Gonococcal arthritis (disseminated gonococcal infection). Infect Dis Clin North Am, 2005. 19(4): p. 853–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barr J and Danielsson D, Septic gonococcal dermatitis. Br Med J, 1971. 1(5747): p. 482–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knapp JS and Holmes KK, Disseminated gonococcal infections caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae with unique nutritional requirements. J Infect Dis, 1975. 132(2): p. 204–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice PA, et al. , Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Drug Resistance, Mouse Models, and Vaccine Development. Annu Rev Microbiol, 2017. 71: p. 665–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lochner HJ and Maraqa NF, Sexually Transmitted Infections in Pregnant Women: Integrating Screening and Treatment into Prenatal Care. Pediatric Drugs, 2018. 20(6): p. 501–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleming DT and Wasserheit JN, From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect, 1999. 75(1): p. 3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fifer H, et al. , Failure of Dual Antimicrobial Therapy in Treatment of Gonorrhea. N Engl J Med, 2016. 374(25): p. 2504–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eyre DW, et al. , Gonorrhoea treatment failure caused by a Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain with combined ceftriaxone and high-level azithromycin resistance, England, February 2018. Euro Surveill, 2018. 23(27): p. 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.England PH, UK case of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with high-level resistance to azithromycin and resistance to ceftriaxone acquired abroad, in Health Protection Report. 2018. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zielke RA, et al. , Quantitative proteomics of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae cell envelope and membrane vesicles for the discovery of potential therapeutic targets. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2014. 13(5): p. 1299–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Rami FE, et al. , Quantitative Proteomics of the 2016 WHO Neisseria gonorrhoeae Reference Strains Surveys Vaccine Candidates and Antimicrobial Resistance Determinants. Mol Cell Proteomics, 2019. 18(1): p. 127–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pizza M, et al. , Identification of vaccine candidates against serogroup B meningococcus by whole-genome sequencing. Science, 2000. 287(5459): p. 1816–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zielke RA, Gafken PR, and Sikora AE, Quantitative proteomic analysis of the cell envelopes and native membrane vesicles derived from gram-negative bacteria. Curr Protoc Microbiol, 2014. 34: p. 1F 3 1–1F 3 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baarda BI, Martinez FG, and Sikora AE, Proteomics, Bioinformatics and Structure-Function Antigen Mining For Gonorrhea Vaccines. Front Immunol, 2018. 9: p. 2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jerse AE, Experimental gonococcal genital tract infection and opacity protein expression in estradiol-treated mice. Infect Immun, 1999. 67(11): p. 5699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jerse AE, et al. , Estradiol-Treated Female Mice as Surrogate Hosts for Neisseria gonorrhoeae Genital Tract Infections. Front Microbiol, 2011. 2: p. 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gulati S, et al. , Complement alone drives efficacy of a chimeric antigonococcal monoclonal antibody. PLoS Biol, 2019. 17(6): p. e3000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jolley KA, Bray JE, and Maiden MCJ, Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res, 2018. 3: p. 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen PT, et al. , Structures of the Neisseria meningitides methionine-binding protein MetQ in substrate-free form and bound to l- and d-methionine isomers. Protein Sci, 2019. 28(10): p. 1750–1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Psychogios N, et al. , The human serum metabolome. PLoS One, 2011. 6(2): p. e16957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zielke RA, et al. , SliC is a surface-displayed lipoprotein that is required for the anti-lysozyme strategy during Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection. PLoS Pathog, 2018. 14(7): p. e1007081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu H, Soler-Garcia AA, and Jerse AE, A strain-specific catalase mutation and mutation of the metal-binding transporter gene mntC attenuate Neisseria gonorrhoeae in vivo but not by increasing susceptibility to oxidative killing by phagocytes. Infect Immun, 2009. 77(3): p. 1091–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu W, et al. , Vaccines for gonorrhea: can we rise to the challenge? Front Microbiol, 2011. 2: p. 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gulati S, et al. , Immunization against a saccharide epitope accelerates clearance of experimental gonococcal infection. PLoS Pathog, 2013. 9(8): p. e1003559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amanda DeRocco HFS, Sempowski Greg, Ventevogel Melissa, Jerse Ann E., Development of MtrE, the outer membrane channel of the MtrCDE and FarAB,MtrE active efflux pump systems, as a gonorrhea vaccine. International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, et al. , Intravaginal Administration of Interleukin 12 during Genital Gonococcal Infection in Mice Induces Immunity to Heterologous Strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. mSphere, 2018. 3(1): p. 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu W, et al. , Comparison of immune responses to gonococcal PorB delivered as outer membrane vesicles, recombinant protein, or Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon particles. Infect Immun, 2005. 73(11): p. 7558–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobsson S, et al. , Sequence constancies and variations in genes encoding three new meningococcal vaccine candidate antigens. Vaccine, 2006. 24(12): p. 2161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu W, et al. , Vaccines for gonorrhea: can we rise to the challenge? Frontiers in Microbiology, 2011. 2: p. 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Easton A, et al. , Combining vaccination and postexposure CpG therapy provides optimal protection against lethal sepsis in a biodefense model of human melioidosis. J Infect Dis, 2011. 204(4): p. 636–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elkins KL, et al. , Bacterial DNA containing CpG motifs stimulates lymphocyte-dependent protection of mice against lethal infection with intracellular bacteria. J Immunol, 1999. 162(4): p. 2291–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waag DM, et al. , A CpG oligonucleotide can protect mice from a low aerosol challenge dose of Burkholderia mallei. Infect Immun, 2006. 74(3): p. 1944–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krieg AM, et al. , CpG DNA induces sustained IL-12 expression in vivo and resistance to Listeria monocytogenes challenge. J Immunol, 1998. 161(5): p. 2428–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Juffermans NP, et al. , CpG oligodeoxynucleotides enhance host defense during murine tuberculosis. Infect Immun, 2002. 70(1): p. 147–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deng JC, et al. , CpG oligodeoxynucleotides stimulate protective innate immunity against pulmonary Klebsiella infection. J Immunol, 2004. 173(8): p. 5148–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bode C, et al. , CpG DNA as a vaccine adjuvant. Expert Rev Vaccines, 2011. 10(4): p. 499–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ortiz MC, et al. , Neisseria gonorrhoeae Modulates Immunity by Polarizing Human Macrophages to a M2 Profile. PLoS One, 2015. 10(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Escobar A, et al. , Neisseria gonorrhoeae induces a tolerogenic phenotype in macrophages to modulate host immunity. Mediators Inflamm, 2013. 2013: p. 127017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.TRUMENBA [Package Insert]. 2018.

- 57.Ouyang W, Kolls JK, and Zheng Y, The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity, 2008. 28(4): p. 454–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feinen B, et al. , Critical role of Th17 responses in a murine model of Neisseria gonorrhoeae genital infection. Mucosal Immunol, 2010. 3(3): p. 312–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Y, Feinen B, and Russell MW, New concepts in immunity to Neisseria gonorrhoeae: innate responses and suppression of adaptive immunity favor the pathogen, not the host. Front Microbiol, 2011. 2: p. 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu Y, et al. , Neisseria gonorrhoeae selectively suppresses the development of Th1 and Th2 cells, and enhances Th17 cell responses, through TGF-beta-dependent mechanisms. Mucosal Immunol, 2012. 5(3): p. 320–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu Y, Liu W, and Russell MW, Suppression of host adaptive immune responses by Neisseria gonorrhoeae: role of interleukin 10 and type 1 regulatory T cells. Mucosal Immunol, 2014. 7(1): p. 165–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schindelin J, et al. , Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods, 2012. 9(7): p. 676–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Movie S1. Ng amino acid polymorphism mapped to Nm MetQ crystal structure bound to L-methionine, rotated about the X axis. Movie generated in PyMol.

Supplemental Movie S2. Ng amino acid polymorphism mapped to Nm MetQ crystal structure bound to L-methionine, rotated about the Y axis. Movie generated in PyMol.

Supplemental Movie S3. Ng amino acid polymorphism mapped to Nm MetQ crystal structure in the substrate-free conformation, rotated about the X axis. Movie generated in PyMol.

Supplemental Movie S4. Ng amino acid polymorphism mapped to Nm MetQ crystal structure in the substrate-free conformation, rotated about the Y axis. Movie generated in PyMol.

Supplemental Figure S1. metQ nucleotide variation across Neisseria genus.

Supplemental Figure S2. Phylogenetic analysis of MetQ variation among Neisseria.

Supplemental Figure S3. In vitro competition assay.

Supplemental Figure S4. Immunization with rMetQ alone or with CpG induces antigen-specific immune response.

Supplemental Figure S5. Infection dynamics from individual rMetQ-CpG immunization experiments. In the first immunization/challenge experiment cohorts of BALB/c mice were immunized with rMetQ-CpG, CpG, or PBS (A, B, C). The second experiment consisted of groups that were given rMetQ, rMetQ-CpG, CpG, or PBS (D, E, F) as per the immunization regimen shown in Fig. 3. Mice in the diestrus stage or in anestrus were treated with 17β-estradiol and antibiotics and challenged with 106 CFU of strain FA1090 three weeks after the final immunization. Vaginal washes were quantitatively cultured for Ng on days 1, 3, 5 and 7 post-bacterial challenge. (A, D) The percentage of mice with positive vaginal cultures was plotted over time as Kaplan Meier curves and the results analyzed by the Log Rank test. (B, E) The average number of CFU recovered from each experimental group was plotted over time. The limit of detection was 20 CFU/mL of vaginal swab suspension. This value was used for mice with negative cultures. Differences in colonization load were assessed by a repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis for multiple pairwise comparisons. (C, F) AUC (log10 CFU/mL) analysis of murine colonization. Data are presented for individual mice. Horizontal bars represent the geometric mean of the data with the 95% confidence interval.

Supplemental Table S1. Analysis of MetQ alleles and number of Ng isolates per allele grouping.

Supplemental Table S2. Etest antibiotic susceptibility experiments.

Supplemental Table S3. Geometric means antibody titers measured in serum and vaginal washes on days 34 and 49, respectively, since the SC immunization.

Geometric mean titers of antibodies against purified rMetQ were determined as described in Materials and Methods.