Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a bacterial pathogen capable of causing a wide array of diseases, ranging from typically mild in severity (e.g., middle ear infections) to often potentially deadly (e.g., pneumonia and sepsis). Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) containing capsular polysaccharide conjugated to protein carriers have been quite effective at preventing invasive pneumococcal disease, in children and adults alike, and they are widely used as a public health tool [1]. However, due to the plasticity of pneumococci, serotype replacement by non-vaccine serotypes often occurs after introduction of PCVs [2]. This necessitates the reformulation of conjugate vaccines to include additional serotypes.

Vaccines may elicit functional, as well as non-functional, antibodies [3]. Therefore, evaluation of the new PCV formulations requires assays that measure functional capacity of anti-capsule antibodies, which provide protection to the host by opsonizing target bacteria for host phagocytes [4]. In vitro opsonophagocytic assays (OPAs), including those using multiplexed formats (MOPAs), are used by many laboratories to assess the immunogenicity of new vaccine formulations [5–7]. Further, OPAs are beginning to be used to evaluate the anti-pneumococcal activity in therapeutic reagents [8] and are proposed as an aid in the diagnosis of primary immunodeficiencies [9]. With the increased use of OPAs across multiple laboratories for these varied applications, the need to reduce inter-laboratory variation of OPA results and to standardize OPA becomes increasingly important.

To aid inter-laboratory standardization, international collaborations have created 007sp [10], the reference serum for pneumococcal assays, and a panel of calibration sera (“Ewha Panel A”) [11]. The opsonic values for these sera have been assigned for the 13 serotypes in Prevnar13® [11, 12]. These studies have also demonstrated that normalization of OPA results using 007sp significantly decreased inter-laboratory variability. As the next generation of PCVs target serotypes beyond those core 13 serotypes [13, 14], assignments of opsonic values for additional serotypes is needed to facilitate the development of new PCVs. Herein, we assign opsonic values to pneumococcal reference serum 007sp for 11 additional serotypes. Additionally, we describe the creation, characterization, and assignment of opsonic values for a new panel of calibration sera (“Ewha Panel B”) for these additional serotypes.

Materials and Methods

Participating Laboratories

The five laboratories that participated in this study are indicated in Table 1. Laboratories are listed alphabetically, and the order in no way correlates with the letter designations used throughout this publication. Each participating laboratory had considerable experience with pneumococcal OPAs.

Table 1.

Participating Laboratories

| Institution Name | Location |

|---|---|

| Ewha Womans University | Seoul, Republic of Korea |

| LG Chem | Seoul, Republic of Korea |

| Merck & Co., Inc. | MRL, West Point, PA,USA |

| SK Bioscience | Seongnam-Si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea |

| University of Alabama at Birmingham | Birmingham, AL, USA |

Sera

The preparation of 007sp has been described previously [10].

The calibration sera were collected under a study approved by the Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital institutional review board (EUMC 2016-01-012-001). To create the Korea OPA Calibration Serum Panel B, 32 individuals were evaluated at the Ewha Center for Vaccine Evaluation and Study, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine after written informed consent. Twenty healthy male and nonpregnant female volunteers between 20 and 50 years of age met the eligibility requirements for this study. Eligibility was determined by a physical assessment and a questionnaire concerning medical history and risk factors associated with exposure to, or clinical evidence of, a relevant transfusion-transmitted infection. Participants were negative for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV. Fifteen volunteers were vaccinated once with 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) (Prodiax23, Merck & Co. Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ) by intramuscular injection, and donated a unit of blood 14 to 22 days following immunization and a second unit of blood 8 to 12 weeks after the first donation (see Table 2). Five volunteers who were vaccinated previously (49–123 months prior) with PPSV23 (Prodiax23) donated a unit of blood, a second unit of blood 8 to 12 weeks later, and in some instances a third unit of blood 8 to 12 weeks after the second donation (Table 2). Blood was allowed to clot and the serum was collected and stored at −80°C at the Ewha Center for Vaccine Evaluation and Study. For each donor, the sera from the 2 blood donations were thawed, pooled, and 1-mL aliquots were prepared (260–444 vials were prepared for each of the 20 sera). The aliquots were lyophilized by EuBiologics Co., Ltd (Chuncheon, Republic of Korea) and are stored at −70°C. The age, sex, and post-vaccination interval for the serum donors are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Serum Donor Information

| QC Name | Donor Age | Donor Sex | Post-Vaccination Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| PnQC-21 | 40 | M | 17 days |

| PnQC-22 | 36 | M | 19 days |

| PnQC-23 | 42 | M | 20 days |

| PnQC-24 | 41 | M | 14 days |

| PnQC-25 | 35 | M | 21 days |

| PnQC-26 | 25 | M | 19 days |

| PnQC-27 | 40 | M | 14 days |

| PnQC-28 | 31 | F | 15 days |

| PnQC-29 | 48 | M | 14 days |

| PnQC-30 | 38 | M | 20 days |

| PnQC-31 | 31 | F | 21 days |

| PnQC-32 | 24 | M | 20 days |

| PnQC-33 | 26 | M | 22 days |

| PnQC-34 | 27 | M | 19 days |

| PnQC-35 | 40 | M | 20 days |

| PnQC-36 | 50 | M | 49 months |

| PnQC-37 | 30 | F | 50 months |

| PnQC-38 | 39 | F | 50 months |

| PnQC-39 | 33 | F | 59 months |

| PnQC-40 | 47 | F | 123 months |

For use in the assays, sera were reconstituted with 1 mLof sterile, distilled water and were heat-inactivated at 56°C for 30 minutes.

Study Design

The primary goal of the study was to assign consensus values to 007sp for 11 additional pneumococcal serotypes (2, 8, 9N, 10A, 11A, 12F, 15B, 17F, 20B, 22F, and 33F). A secondary goal of the study was to assign consensus values to the Ewha Panel B Calibration Sera for those serotypes. To accomplish these goals, each laboratory tested each of the twenty sera in five valid runs for these serotypes. In each run, 007sp was tested three times, independently. Each laboratory used its own batches/lots of reagents for the assays.

OPAs

All laboratories used the multiplexed OPA (MOPA) as previously described (Burton 2006), and a detailed protocol can be found at www.vaccine.uab.edu. Briefly, ten microliters of diluted bacteria (four strains) were added to 20 microliters of serially diluted serum. After incubation at room temperature for 30 minutes with shaking, ten microliters of baby rabbit complement (note, one participating laboratory used adsorbed baby rabbit complement as described previously [15]) and 4 × 105 differentiated HL60 cells (in 40 microliters) were added to each well. After incubation at 37°C/5% CO2 with shaking, plates were incubated on ice, and spotted onto culture plates. After overnight growth at 37°C/5% CO2, the numbers of surviving colony forming units (CFUs) were enumerated. All laboratories used Opsotiter template to convert CFUs to Opsonic Indexes (OIs).

Statistical Methods

For each serotype, the consensus OIs and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for 007sp were obtained by back-transforming the model intercept and its corresponding CI.

Statistical analyses for the calibration sera were performed as described previously [11]. Calibration sera OIs were normalized using the following formula:

Unadjusted and normalized consensus OIs, and the associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for the calibration sera were estimated for each sample and serotype using a mixed effects ANOVA model consisting of the random terms Lab and Run(Lab).

For each serotype, the percent reduction in inter-laboratory variability due to normalization was calculated as:

with , , , and defined as the inter-laboratory, run-within-laboratory, sample-by-laboratory, and sample-by-run-within-laboratory variance component estimates for the unadjusted OIs, respectively; and , , , and defined as the corresponding variance components for the normalized OIs.

Results

The consensus values for 007sp estimated from the ANOVA model are shown in Table 3. For serotype 10A, the inter-laboratory results agreed well, yielding a low CV (46%) and a narrow confidence interval (6009 to 16609). There was more variation seen for serotypes 2, 12F, and 15B, with CVs in the 60%−70% range and corresponding increases in the confidence intervals. For the remaining seven serotypes, the CVs are greater than 100%.

Table 3. 007sp results.

The consensus OIs, as well as the laboratory-specific GMOIs, for 007sp are shown for the indicated target serotypes. The table also shows the variance components estimates for each target.

| Pn | Laboratory-Specific GMOI | Consensus OI (95% CI) | Variance Components | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab A | Lab B | Lab C | Lab D | Lab E | Lab | Run (Lab) | Plate (Run × Lab) | %CV | ||

| 2 | 3936 | 1224 | 1829 | 1992 | 5045 | 2452 (798,7529) | 0.085 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 76 |

| 8 | 5526 | 524 | 3623 | 3201 | 5426 | 2843 (433,18527) | 0.190 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 132 |

| 9N | 18269 | 4335 | 12398 | 48500 | 7163 | 12949 (2259,74210) | 0.188 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 131 |

| 10A | 10726 | 9494 | 7729 | 14813 | 8610 | 9990 (6009,16609) | 0.034 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 46 |

| 11A | 4914 | 918 | 3548 | 6100 | 2544 | 3068 (710,13257) | 0.146 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 112 |

| 12F | 10884 | 5538 | 6231 | 6180 | 3921 | 6257 (2994,13076) | 0.082 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 74 |

| 15B | 13265 | 7896 | 4727 | 13110 | 6538 | 8372 (3548,19754) | 0.066 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 65 |

| 17F | 19507 | 3271 | 12161 | 30992 | 10292 | 12405 (2322,66277) | 0.268 | 0.115 | 0.115 | 177 |

| 20B | 11218 | 2505 | 6829 | 24240 | 7451 | 8076 (1619,40289) | 0.159 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 118 |

| 22F | 7481 | 1874 | 6481 | 9240 | 4753 | 5511 (1516,20028) | 0.163 | 0.070 | 0.070 | 118 |

| 33F | 33733 | 14451 | 34334 | 97085 | 24960 | 32901 (8214,132000) | 0.181 | 0.078 | 0.078 | 127 |

Pn, pneumococcal serotype; OI, Opsonic Index; CI, confidence interval; GMOI, geometric mean OI; Lab, variability among the laboratories; Run(Lab), variability among runs within each laboratory; Plate(RunxLab), plate-associated variability within each combination of run and laboratory; CV, coefficient of variation.

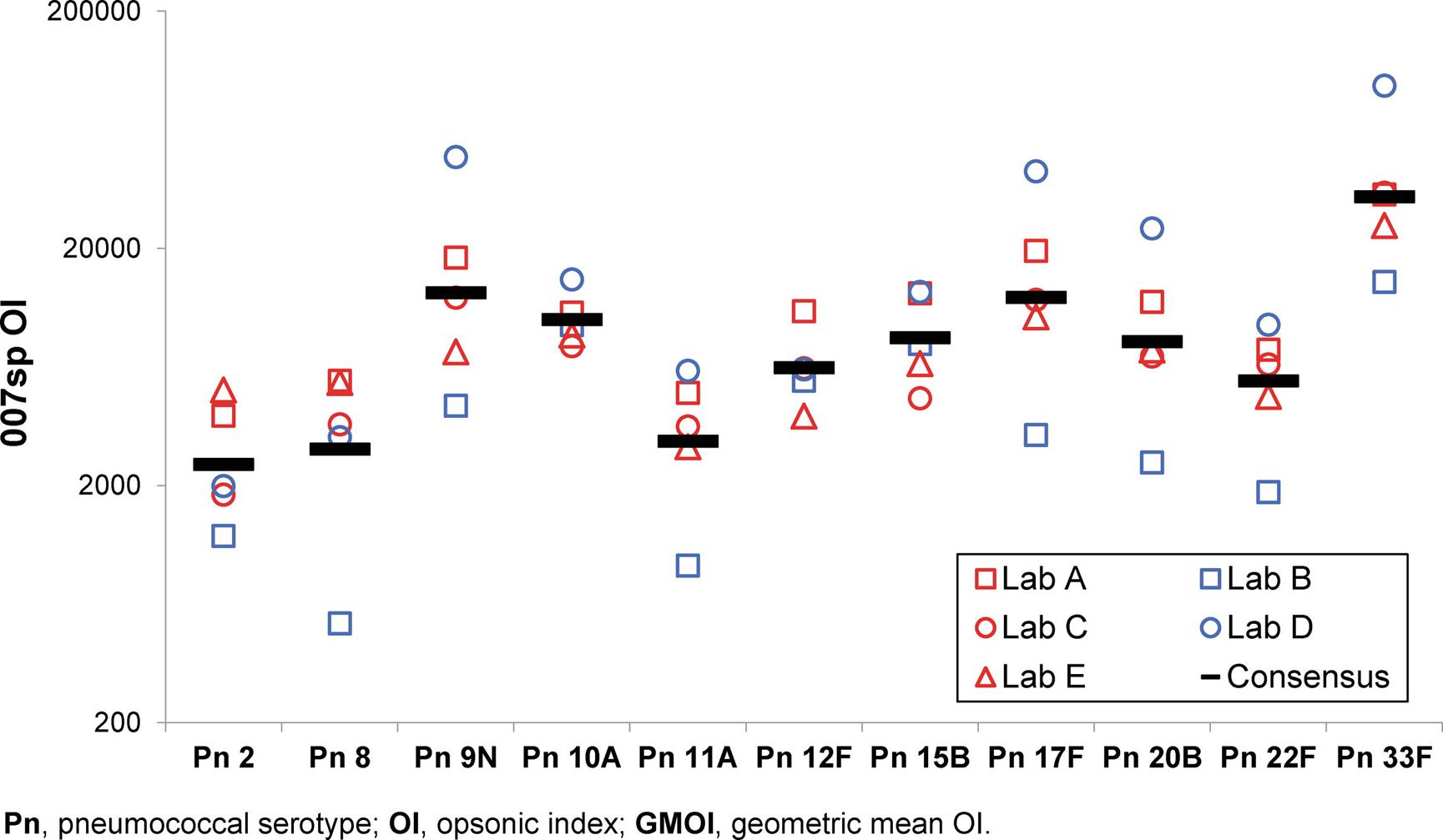

As shown in Table 3, the results of the ANOVA indicate “Lab” as the major contributor to the variance for 007sp. For many of the serotypes with high inter-laboratory variation, the results from Lab B and Lab D are responsible for a significant portion of the variation, with Lab D reporting the highest and Lab B reporting the lowest values for most of the serotypes (see Figure 1). The results from Lab B and Lab D also deviate significantly from the results of the other laboratories for multiple serotypes.

Figure 1. 007sp Results.

For each target serotype (X axis), the laboratory-specific 007sp GMOI for each laboratory (see legend), as well as the consensus OI for 007sp, are shown on the Y axis.

For the calibration sera, the consensus value for each serum for each serotype was estimated by ANOVA. The consensus normalized results are shown in Table 4, and the consensus unadjusted values are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The confidence intervals for the normalized OIs varied from small (e.g., serotypes 2 and 8) to large (e.g., serotype 10A).

Table 4. Normalized consensus OIs for calibration sera.

For each serum sample, the consensus OI (with the 95% confidence interval) for the indicated target serotype is shown.

| Sample # | Pn 2 | Pn 8 | Pn 9N | Pn 10A | Pn 11A | Pn 12F | Pn 15B | Pn 17F | Pn 20B | Pn 22F | Pn 33F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PnQC-21 | 3888 (2851,5302) | 1920 (1558,2365) | 11067 (5252,23321) | 1538 (450,5256) | 1414 (757,2642) | 1271 (581,2782) | 11824 (6371,21943) | 13779 (7646,24829) | 7093 (2580,19500) | 2964 (1727,5088) | 6761 (3025,15111) |

| PnQC-22 | 677 (438,1046) | 964 (732,1269) | 1460 (882,2417) | 216 (61,765) | 583 (360,946) | 234 (16,3358) | 2667 (1117,6367) | 879 (399,1937) | 870 (482,1572) | 1475 (916,2375) | 4657 (1604,13520) |

| PnQC-23 | 976 (622,1532) | 5199 (3805,7104) | 14193 (6672,30191) | 10253 (4805,21879) | 662 (378,1160) | 1554 (806,2996) | 24884 (13129,47162) | 6664 (2268,19580) | 10367 (4098,26224) | 4069 (2947,5617) | 16873 (5599,50851) |

| PnQC-24 | 2400 (2035,2830) | 1615 (1354,1925) | 8094 (4194,15620) | 4292 (1855,9934) | 2267 (1028,5003) | 2644 (1877,3724) | 5817 (3397,9964) | 9505 (4302,21000) | 5052 (3272,7801) | 3130 (1854,5285) | 49335 (29436,82685) |

| PnQC-25 | 694 (609,791) | 1365 (1119,1665) | 2030 (897,4597) | 1512 (827,2763) | 960 (437,2107) | 896 (651,1233) | 2048 (1104,3798) | 2144 (970,4737) | 1600 (792,3231) | 1391 (664,2914) | 2905 (1410,5984) |

| PnQC-26 | 3075 (2088,4529) | 1343 (1054,1711) | 5783 (2970,11260) | 1755 (809,3809) | 341 (40,2936) | 1213 (783,1878) | 1845 (1203,2830) | 1662 (745,3706) | 5340 (3414,8354) | 4172 (2120,8213) | 14750 (7255,29988) |

| PnQC-27 | 898 (597,1352) | 1758 (1139,2715) | 6620 (2871,15263) | 2446 (1179,5075) | 455 (243,850) | 1418 (864,2328) | 3982 (1755,9038) | 4638 (1958,10987) | 2542 (1192,5423) | 1631 (1046,2542) | 25364 (7284,88326) |

| PnQC-28 | 3162 (2382,4197) | 1008 (557,1823) | 8207 (3703,18190) | 3149 (747,13272) | 631 (363,1097) | 1179 (394,3528) | 23371 (12783,42730) | 9753 (5514,17250) | 3227 (1684,6185) | 2062 (734,5790) | 7437 (2891,19132) |

| PnQC-29 | 1672 (1195,2339) | 282 (218,366) | 6497 (3240,13029) | 2739 (1350,5556) | 208 (70,622) | 1047 (582,1884) | 3255 (835,12690) | 2068 (748,5716) | 385 (41,3660) | 12 (3,39) | 21237 (8072,55877) |

| PnQC-30 | 377 (301,472) | 1003 (577,1744) | 3268 (1460,7313) | 2003 (874,4590) | 344 (51,2336) | 2132 (1480,3072) | 1167 (210,6503) | 4613 (2104,10111) | 1064 (514,2204) | 1038 (654,1648) | 2982 (1505,5911) |

| PnQC-31 | 1663 (1046,2643) | 787 (605,1023) | 1238 (712,2153) | 5434 (2363,12498) | 531 (354,797) | 4701 (3440,6423) | 80 (8,761) | 2072 (981,4378) | 268 (32,2265) | 4890 (2634,9079) | 19192 (9341,39429) |

| PnQC-32 | 1482 (1141,1924) | 2565 (2083,3158) | 4949 (2409,10169) | 4117 (1607,10549) | 5174 (3595,7447) | 5993 (4617,7779) | 4097 (1832,9163) | 3626 (1918,6853) | 3557 (1758,7197) | 5087 (1650,15684) | 142000 (79570,252000) |

| PnQC-33 | 1418 (1234,1630) | 3262 (1836,5796) | 13272 (6885,25581) | 1584 (297,8444) | 2530 (1145,5592) | 2363 (1518,3677) | 2849 (1092,7430) | 4589 (1942,10848) | 5197 (2863,9433) | 1479 (451,4849) | 11917 (6558,21654) |

| PnQC-34 | 5124 (4128,6360) | 1388 (943,2043) | 11872 (5775,24406) | 5970 (2182,16332) | 3294 (1439,7541) | 3609 (1949,6683) | 9370 (5052,17380) | 11064 (5905,20730) | 4166 (2642,6570) | 2767 (921,8319) | 77224 (41801,143000) |

| PnQC-35 | 1176 (836,1653) | 1967 (1434,2699) | 3666 (1796,7480) | 1890 (510,7007) | 1409 (520,3817) | 1493 (885,2520) | 3398 (1508,7659) | 3721 (1535,9022) | 6623 (2420,18124) | 3035 (1363,6758) | 32410 (15780,66566) |

| PnQC-36 | 6 (3,13) | 7 (3,18) | 711 (425,1188) | 242 (27,2215) | 92 (36,235) | 4 (NA) | 533 (235,1209) | 269 (148,489) | 88 (13,583) | 30 (6,160) | 2166 (597,7856) |

| PnQC-37 | 654 (394,1084) | 878 (484,1593) | 2671 (1187,6012) | 975 (336,2827) | 199 (43,910) | 1997 (1262,3160) | 5263 (2552,10853) | 3292 (1347,8047) | 480 (88,2606) | 1016 (425,2425) | 6082 (2735,13525) |

| PnQC-38 | 427 (256,712) | 235 (199,277) | 2058 (967,4379) | 2953 (625,13951) | 328 (48,2231) | 7 (1,57) | 974 (207,4573) | 2303 (1002,5291) | 1167 (684,1990) | 247 (39,1550) | 1886 (734,4844) |

| PnQC-39 | 3379 (2105,5424) | 614 (391,964) | 4321 (1797,10390) | 4187 (1152,15216) | 487 (51,4614) | 10 (1,132) | 77 (12,479) | 3850 (1667,8891) | 4277 (2096,8728) | 1651 (1115,2446) | 2982 (822,10826) |

| PnQC-40 | 206 (152,279) | 352 (286,433) | 1572 (680,3634) | 1329 (486,3639) | 585 (345,991) | 91 (9,869) | 157 (13,1925) | 1378 (632,3004) | 184 (24,1409) | 123 (15,1028) | 6405 (3328,12327) |

Pn, pneumococcal serotype; OI, opsonic index; NA, Not Applicable; see Discussion for explanation of bold, italic font.

Normalizing the OIs for the calibration sera using 007sp resulted in significant decreases in variability for serotypes 2, 8, and 11A (≥40% reductions in variability, see Table 5). The effect of normalization was less dramatic for 12F, 17F, and 20B (14%−24% reductions), with little effect noted for the remaining serotypes. It is interesting that while serotype 10A had the lowest CV for the 007sp results, it was the only serotype for which normalization increased the variability.

Table 5. Effects of Normalization.

For the indicated target serotypes, the overall CVs of the unadjusted and normalized results and the reduction in variability that resulted from normalization are shown. For each set of data (unadjusted and normalized), the estimated variance components are also indicated.

| Unadjusted Data | Normalized Data | Variability Reduction (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pn | Lab | Lab × Sample | Run (Lab) | Sample (Run × Lab) | %CV | Lab | Lab × Sample | Run (Lab) | Sample (Run × Lab) | %CV | |

| 2 | 0.082 | 0.024 | 0.032 | 0.016 | 74 | 0.033 | 0.024 | 0.019 | 0.016 | 44 | 40% |

| 8 | 0.170 | 0.038 | 0.038 | 0.029 | 121 | 0.048 | 0.038 | 0.036 | 0.029 | 54 | 45% |

| 9N | 0.083 | 0.025 | 0.036 | 0.017 | 74 | 0.085 | 0.024 | 0.025 | 0.017 | 75 | 7% |

| 10A | 0.232 | 0.138 | 0.149 | 0.122 | 156 | 0.278 | 0.135 | 0.147 | 0.118 | 184 | −6% |

| 11A | 0.444 | 0.132 | 0.109 | 0.049 | 317 | 0.200 | 0.133 | 0.063 | 0.049 | 137 | 40% |

| 12F | 0.275 | 0.175 | 0.113 | 0.073 | 182 | 0.234 | 0.163 | 0.081 | 0.071 | 157 | 14% |

| 15B | 0.292 | 0.225 | 0.191 | 0.183 | 192 | 0.300 | 0.216 | 0.190 | 0.180 | 198 | 0% |

| 17F | 0.117 | 0.039 | 0.043 | 0.029 | 93 | 0.100 | 0.033 | 0.028 | 0.024 | 83 | 19% |

| 20B | 0.314 | 0.173 | 0.053 | 0.042 | 207 | 0.194 | 0.167 | 0.044 | 0.038 | 135 | 24% |

| 22F | 0.038 | 0.156 | 0.146 | 0.098 | 203 | 0.187 | 0.150 | 0.093 | 0.085 | 130 | −17% |

| 33F | 0.131 | 0.068 | 0.066 | 0.048 | 104 | 0.140 | 0.069 | 0.061 | 0.048 | 106 | −1% |

Pn, pneumococcal serotype; Lab, variability among the laboratories; Lab × Sample, variability associated with laboratory and sample interactions; Run(Lab), variability among runs within each laboratory; Sample (Run × Lab), sample-associated variability within each combination of run and laboratory; CV, coefficient of variation.

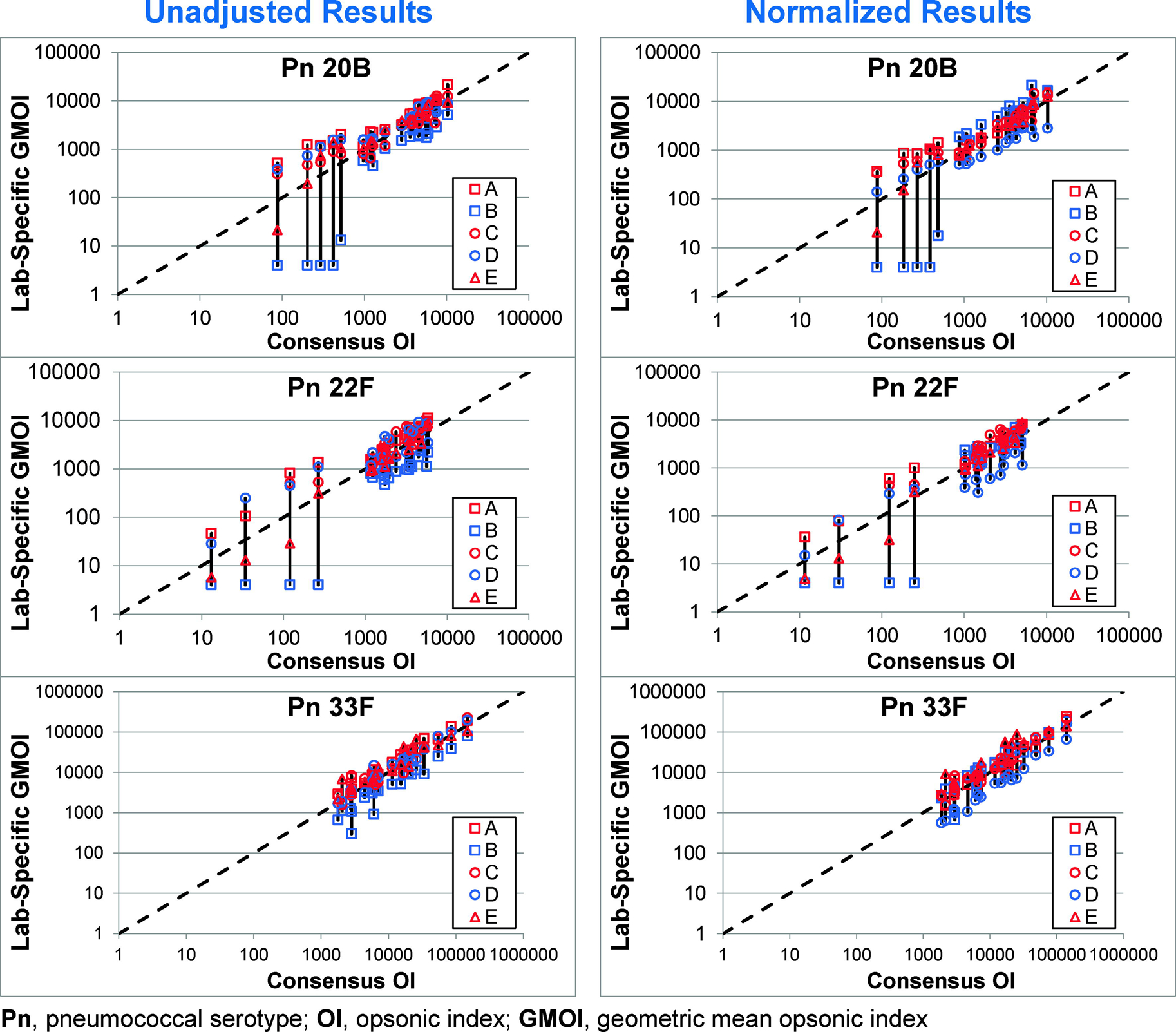

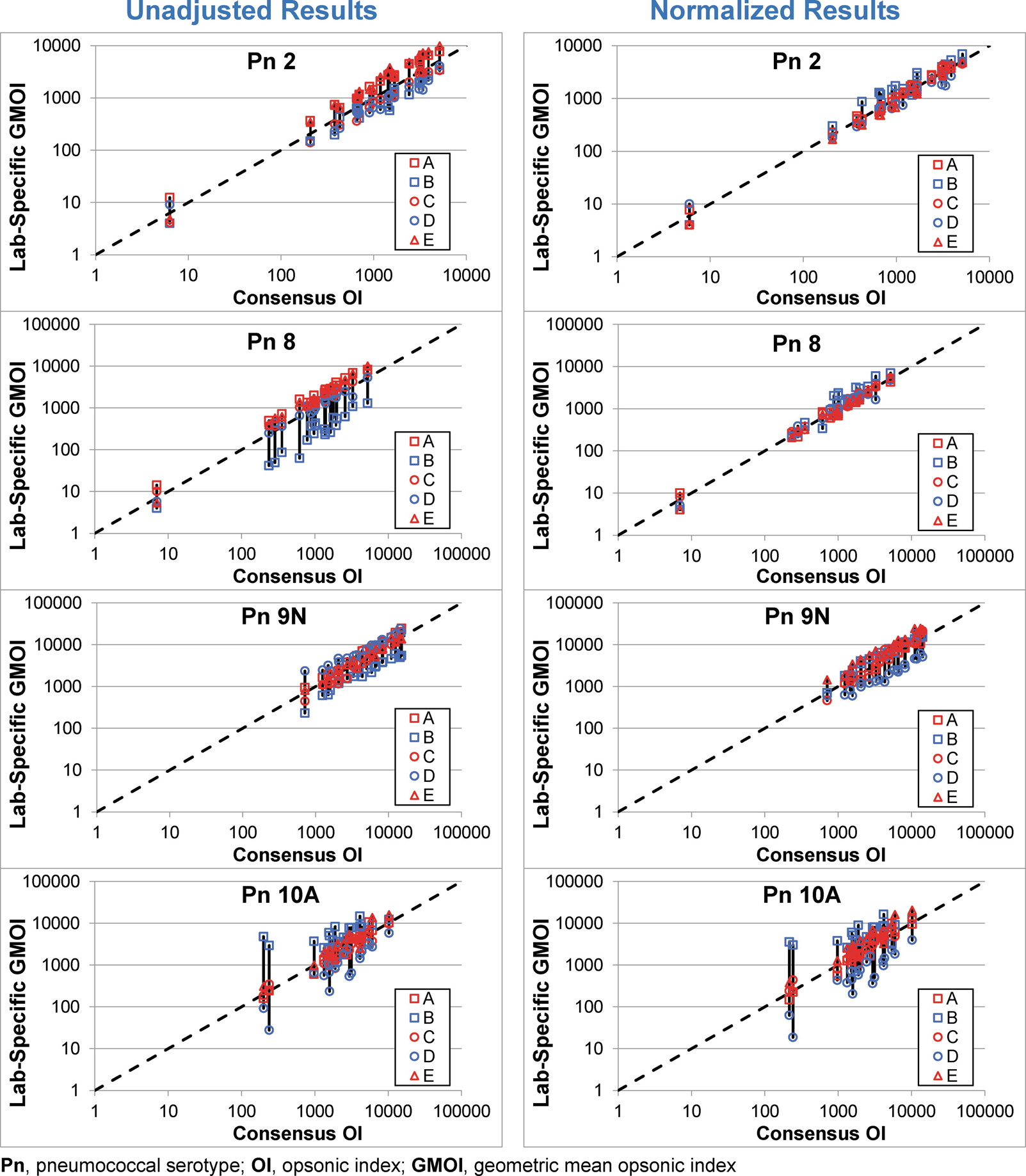

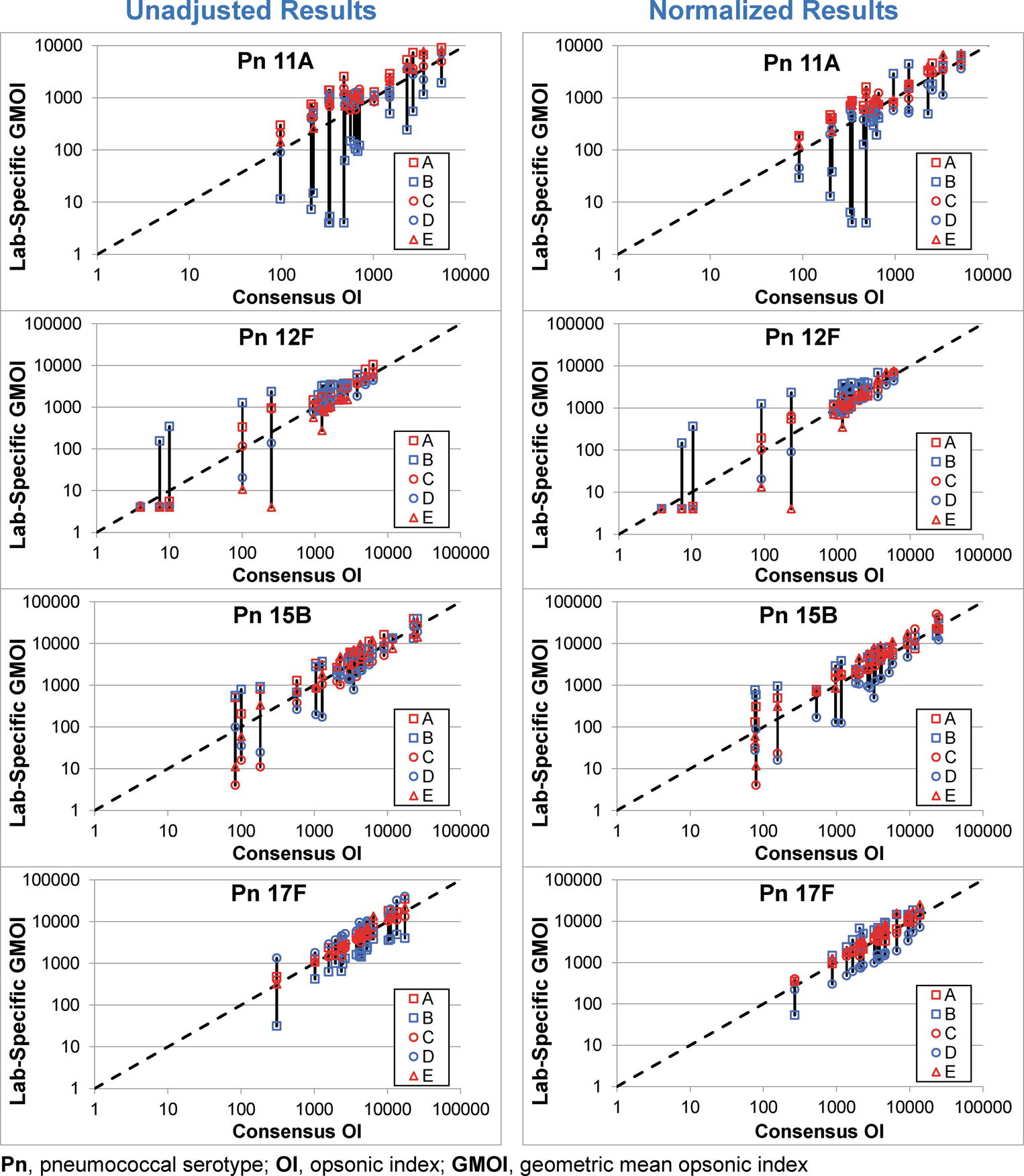

The effect of normalization can also be seen in Figure 2. For each serotype, the left graphs display the agreement of each laboratory with the consensus values using the unadjusted OIs and the right graphs display the agreement using the normalized OIs. The effect of normalization can be seen by comparing the length of the vertical bars connecting the results from each laboratory. The results for serotype 8 were the most striking with the obvious bias observed for Lab B completely abrogated by normalization.

Figure 2. Impact of Standardization.

In each plot, the consensus OI (X axis) and the GMOI from each laboratory (Y axis) are shown for the 20 sera, with the GMOIs connected by a solid black vertical bar. The dashed line indicates identity. Unadjusted and normalized data are shown in the left and right plots, respectively, for each serotype.

Samples PnQC36 through PnQC40 were collected after an extended post-vaccination interval (>4 years, see Table 2). To determine the impact these sera have on the results, the data from those samples was removed from Figure 2 (see Supplemental Figure S1). Although these sera did provide some low consensus OIs, there was a considerable amount of variability typically associated with them.

Discussion

Consensus values for pneumococcal reference serum 007sp have been previously reported for the serotypes in the currently licenses PCVs [11, 12]. To facilitate the development of next generation PCVs, we describe consensus opsonic values for 11 additional serotypes in. With these additional serotypes, 007sp now has values assigned for 24 serotypes, the 23 serotypes in PPV23 plus serotype 6A. Also, a serum panel was created, and the opsonic values were assigned for these additional 11 serotypes to those sera.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the third published study examining the effect of standardizing (or normalizing) OPA results on inter-laboratory variability [11, 12]. Although some laboratories in the current study also participated in more than one of the previous studies, each study was comprised of a unique set of laboratories. All of these studies shared a common result. Namely, standardization of OPA results can significantly decrease inter-laboratory variations for some serotypes. The current study found that normalization reduced inter-laboratory variability by 40%−45% for serotypes 2, 8, and 11A. For serotypes 12F, 15B, and 17F, the magnitude of the effect was lower, with 14%−24% reductions in variability. For the remaining five serotypes, normalization had a minimal effect on variability.

Generally, across all serotypes, OIs greater than ~1000 either agreed well prior to normalization or their agreement improved significantly with normalization. For multiple samples with OIs less than ~1000, the benefits of normalization were typically limited by the relatively low assay sensitivity of Lab B which resulted in a disproportionate number of undetectable OIs (e.g., serotypes 11A, 20B, and 22F). Since normalization cannot be applied to samples with undetectable OIs, normalization was not expected to significantly reduce inter-assay variability in these situations. A similar trend was seen in a previous study [11].

In our experience, assay sensitivity can be influenced by the four biological reagents used in the assay: target bacteria, baby rabbit serum (BRC, as a complement source), fetal bovine serum (FBS, used for assay buffer), and HL60 cells (as effector cells). All laboratories in this collaboration used the same MOPA target bacteria, making the target bacteria strain an unlikely source for sensitivity differences. Although all laboratories used the same HL60 cell line from ATCC, we have seen that the use of sub-optimal HL60 cells can decrease assay sensitivity (unpublished observation). However, the most likely reason for low sensitivity is the FBS used for assay buffer or BRC, where we have observed significant lot-to-lot differences in activity for both reagents.

When comparing analytical assays, it is ideal to have a serum panel that covers the entire operating range of the assays. Although there is some heterogeneity in the post-vaccination results, the results tend to be in the middle to high range. As a novel approach to identify a potential source of low OI sera, five of the calibration sera were collected after an extended post-vaccination interval (PnQC36-PnQC40, see Table 2). Although some of the OIs for these sera were low, multiple sera were associated with irregular killing curves which are often observed in pre-immune adult sera (personal observation). As can be seen by comparing the results in Figure 2 with those in Figure S1 (with the results from PnQC36-PnQC40 removed), these five sera are major contributors to the variation, in the unadjusted as well as the normalized results. Therefore, we believe the sera collected after an extended post-vaccination interval should not be used as calibration sera (the consensus OIs for these sera are indicated in bold, italic font in Table 4).

These observations highlight the need to consider assay sensitivity when addressing assay comparability. At the moment, there is no standard that can be used to establish absolute OPA sensitivity. However, the sera in this study (007sp and the calibration sera) may be useful to determine relative assay sensitivity, with the consensus OIs providing a target for sensitivity. To aid such efforts, these sera may be obtained by contacting Dr. Kyung-Hyo Kim at Ewha Womans University (kaykim@ewha.ac.kr) or Dr. Hyungok Chun at Biologics Research Division, National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation, Republic of Korea (hyungok@korea.kr).

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HHSN272201200005C, M.H.N.), and the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (17172MFDS275, K.H.K.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Yildirim I, Shea KM, Pelton SI. Pneumococcal Disease in the Era of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:679–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Weinberger DM, Malley R, Lipsitch M. Serotype replacement in disease after pneumococcal vaccination. Lancet. 2011;378:1962–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lee H, Nahm MH, Burton R, Kim KH. Immune response in infants to the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against vaccine-related serotypes 6A and 19A. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:376–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Winkelstein JA. The role of complement in the host’s defense against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Rev Infect Dis. 1981;3:289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Caro-Aguilar I, Indrawati L, Kaufhold RM, Gaunt C, Zhang Y, Nawrocki DK, et al. Immunogenicity differences of a 15-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (PCV15) based on vaccine dose, route of immunization and mouse strain. Vaccine. 2017;35:865–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Xie J, Zhang Y, Caro-Aguilar I, Indrawati L, Smith WJ, Giovarelli C, et al. Immunogenicity Comparison of a Next Generation Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Animal Models and Human Infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ermlich SJ, Andrews CP, Folkerth S, Rupp R, Greenberg D, McFetridge RD, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in pneumococcal vaccine-naive adults >/=50 years of age. Vaccine. 2018;36:6875–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lee S, Kim HW, Kim KH. Functional antibodies to Haemophilus influenzae type B, Neisseria meningitidis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae contained in intravenous immunoglobulin products. Transfusion. 2017;57:157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].LaFon DC, Nahm MH. Measuring immune responses to pneumococcal vaccines. J Immunol Methods. 2018;461:37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Goldblatt D, Plikaytis BD, Akkoyunlu M, Antonello J, Ashton L, Blake M, et al. Establishment of a new human pneumococcal standard reference serum, 007sp. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1728–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Burton RL, Kim HW, Lee S, Kim H, Seok JH, Lee SH, et al. Creation, characterization, and assignment of opsonic values for a new pneumococcal OPA calibration serum panel (Ewha QC sera panel A) for 13 serotypes. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Burton RL, Antonello J, Cooper D, Goldblatt D, Kim KH, Plikaytis BD, et al. Assignment of opsonic values to pneumococcal reference serum 007sp for use in opsonophagocytic assays for 13 serotypes. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2017;24:e00457–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Thompson A, Lamberth E, Severs J, Scully I, Tarabar S, Ginis J, et al. Phase 1 trial of a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy adults. Vaccine. 2019;37:6201–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].https://vaxcyte.com/news/. 2020.

- [15].Burton RL, Nahm MH. Development of a fourfold multiplexed opsonophagocytosis assay for pneumococcal antibodies against additional serotypes and discovery of serological subtypes in Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 20. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:835–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.