Abstract

Optimized selection of the slow-relaxing components of single-quantum 13C magnetization in 13CH3 methyl groups of proteins using acute (< 90°) angle 1H radio-frequency pulses, is described. The optimal selection scheme is more relaxation-tolerant and provides sensitivity gains in comparison to the experiment where the undesired (fast-relaxing) components of 13C magnetization are simply ‘filtered-out’ and only 90° 1H pulses are employed for magnetization transfer to and from 13C nuclei. When applied to methyl 13C single-quantum Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) relaxation dispersion experiments for studies of chemical exchange, the selection of the slow-relaxing 13C transitions results in a significant decrease in intrinsic (exchange-free) transverse spin relaxation rates of all exchanging species. For exchanging systems involving high-molecular-weight species, the lower transverse relaxation rates translate into an increase in the information content of the resulting relaxation dispersion profiles.

Keywords: methyl NMR, 13CH3 spin-system, acute angle RF pulses, methyl 13C CPMG relaxation dispersion

Methyl groups serve as unique probes of molecular structure and dynamics, and as such have played an important role in NMR investigations of proteins and protein complexes yielding considerable insights into a variety of biochemical processes (Tugarinov et al. 2004; Rosenzweig and Kay 2014; Schütz and Sprangers 2020). Recently, we revisited several classes of NMR experiments targeting selectively 13CH3-labeled methyl sites of proteins in a highly deuterated environment, focusing primarily on pulse-scheme design optimization from the perspective of both sensitivity and simplicity. In particular, we demonstrated the utility of acute (< 90°) angle 1H radio-frequency (RF) pulses for more efficient and sensitive selection of 1H and 13C transitions belonging to the I = 1/2 manifolds of 13CH3 groups, effectively reducing the complexity of a 13CH3 spin-system to the simpler case of its AX(13C-1H) counterpart (Tugarinov et al. 2020a). A special case of acute angle RF pulses, the magic-angle (54.7°) 1H pulse, was shown, in the case of small to intermediate sized proteins, to simplify pulse schemes and improve sensitivity of NMR experiments that quantify the amplitudes of methyl three-fold symmetry axis motions (Tugarinov et al. 2020b).

The present communication provides a further demonstration of the utility of acute angle RF pulses in methyl NMR. The pulse scheme design stems from the realization that in NMR applications targeting single-quantum (SQ) 13C transitions in a 13CH3 methyl group for quantitative measurements of methyl 1H-13C residual dipolar couplings in the indirect dimension of methyl 1H-13C correlation spectra (Ottiger et al. 1998; Karamanos et al. 2020) or methyl 13C SQ relaxation dispersion experiments (Lundström et al. 2007), the simplification of the spin-system, previously achieved via selection of the transitions belonging to the I = 1/2 manifolds (Tugarinov et al. 2020a), can be accomplished with higher sensitivity through a more straightforward selection of a subset of slow-relaxing (inner) 13C transitions of all methyl manifolds. We show that when this selection is incorporated into a methyl 1H-13C HSQC pulse scheme (Bodenhausen and Ruben 1980), however, the transfer of magnetization from methyl protons to 13C and back to methyl protons for detection, commonly achieved via INEPT schemes (Morris and Freeman 1979) and 90° 1H pulses, becomes suboptimal with respect to attainable sensitivity in the presence of relaxation. The transfer of magnetization to and from the slow-relaxing 13C transitions can be optimized via isolation of slow-relaxing (inner) 1H transitions in conjunction with careful adjustment of the angles of the relevant 1H pulses. This optimized transfer scheme is applied to methyl 13C SQ Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) (Carr and Purcell 1954; Meiboom and Gill 1958) relaxation dispersion experiments (Lundström et al. 2007) recorded on the slow-relaxing methyl 13C transitions of a {U-[2H]; Ileδ1-[13CH3]; Leu,Val-[13CH3,12CD3]}-labeled (ILV-{13CH3}) sample of the ΔST-DNAJB6b deletion mutant of the human DNAJB6b chaperone, a 25-kDa molecular system that undergoes exchange between a major monomeric species and a sparsely populated high-molecular-weight oligomeric species (Karamanos et al. 2019). We show that selection of the slow-relaxing 13C transitions significantly reduces the intrinsic (exchange-free) transverse spin relaxation rates of all exchanging states, and is accompanied by an increase in the information content of the relaxation dispersion profiles for exchanging systems involving high-molecular-weight species (Baldwin et al. 2012).

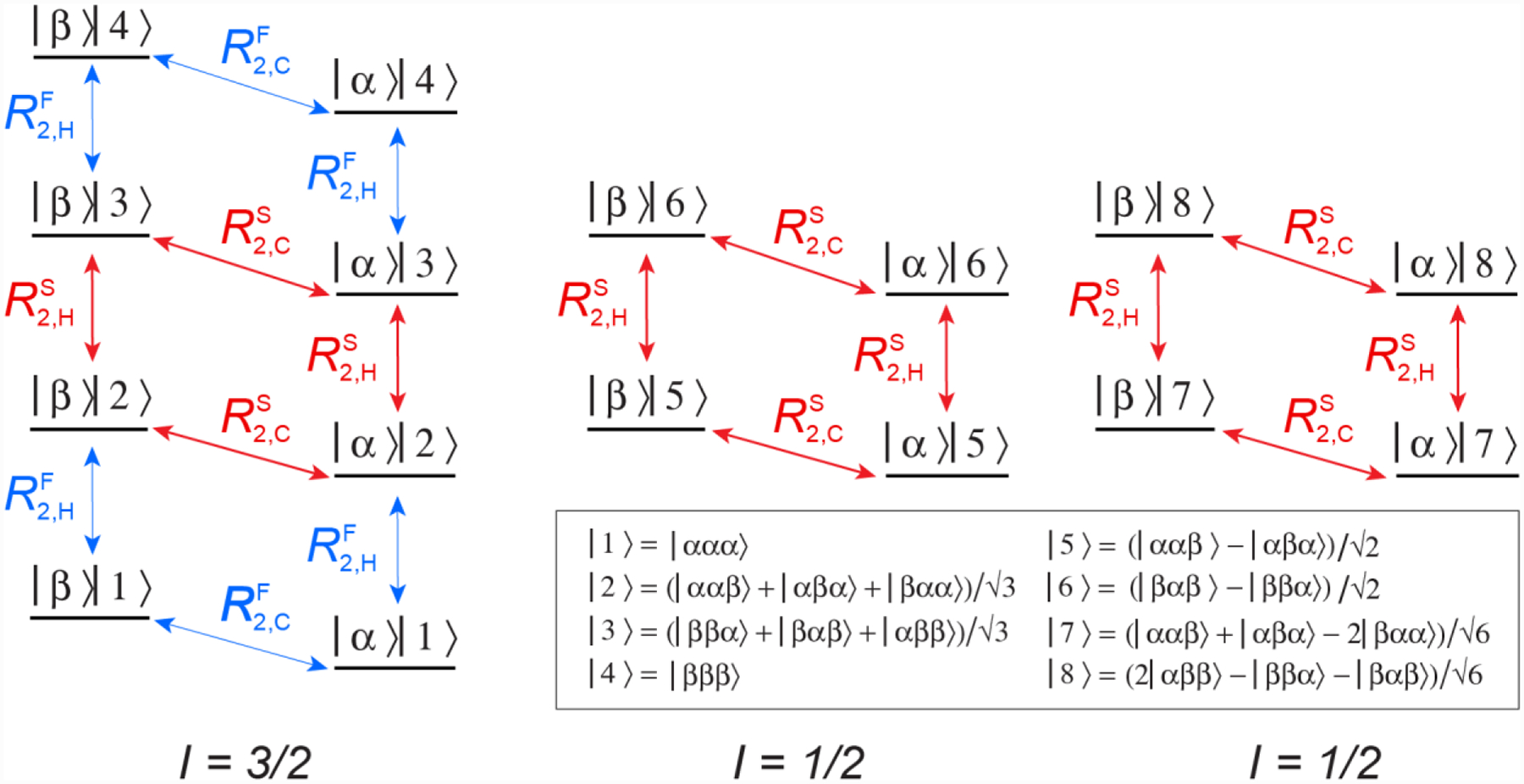

The energy level diagram of a 13CH3 methyl spin system is shown in Figure 1, and consists of one manifold with spin I = 3/2 and two manifolds with I = 1/2. Vertical and diagonal arrows show a total of 10 SQ 1H and 8 SQ 13C transitions, respectively. In the macromolecular limit, transverse spin relaxation of the inner 1H and 13C transitions of the I = 3/2 and I = 1/2 manifolds occurs with slower rates (RS2,H and RS2,C, shown with red arrows; Figure 1), while the outer 1H and 13C transitions of the I = 3/2 manifold are characterized by much faster rates of decay (RF2,H and RF2,C, blue arrows) (Tugarinov et al. 2003). Although this is not exactly true (Tugarinov and Kay 2007), the slow relaxation rates of 1H and 13C transitions of the I = 3/2 and I = 1/2 manifolds are assumed to be equal for the purposes of the following discussion. It is clear from the diagram in Figure 1 that since the inner 13C transitions of the I = 3/2 and I = 1/2 manifolds corresponding to 1H eigenstates {|2>, |5>, |7>} and {|3>, |6>, |8>}, respectively, are degenerate (i.e. have the same chemical shifts), a quartet of peaks is observed in the 13C dimension of a 1H-coupled HSQC experiment (with a 3:1:1:3 ratio of the quartet peak intensities in the absence of relaxation).

Figure 1.

Energy level diagram of the 13CH3 (AX3) spin-system of a methyl group. Single-quantum 1H and 13C transitions are shown by vertical and diagonal arrows, respectively. The slow- and fast-relaxing 1H (R2,H) and 13C (R2,C) transitions are distinguished by superscripts ‘S’ and ‘F’ and shown with red and blue arrows, respectively. The spin quantum numbers, I, of the three manifolds are specified below the energy level diagram. The 16 eigenstates are represented by |m>|n>, where |m> is the state of the 13C spin, m ∈ {α,β}, and the 8 1H eigen-states |n> are described by linear combinations of |i,j,k> (i,j,k ∈ {α,β}). Theoretical expressions for the transverse spin relaxation rates R2,H and R2,C in the macromolecular limit can be found, for example, in (Tugarinov and Kay 2013).

Kontaxis and Bax (2001) previously described a procedure to separate each of the peaks (components) of the 13C quartet. Separating the two slow-relaxing, inner components is much more straightforward considering that the total signal I evolves with time τ as, I(τ) = I0{3cos(3πJCHτ) +cos(πJCHτ)}, where JCH is the one-bond 1H-13C scalar coupling in a methyl group, the first term accounts for the evolution of the outer two components, and the second one describes that of the inner (slow-relaxing) components of interest. Adjusting the delay τ to 1/(6JCH) ensures that angles of 30° and 90° are accrued by the inner and outer components, respectively, allowing one to select for the former with a loss of only (1 – √3/2) = 0.13 of initial magnetization. The scheme with this selection implemented before the indirect evolution period (t1; 13C) of a 1H-13C HSQC experiment, SHSQC, is reproduced for clarity in Figure 2A, with the element selecting for the slow-relaxing 13C transitions enclosed in a solid box. The signal detected at the end of the experiment in Figure 2A, SSHSQC, as a function of the direct (t2) and indirect (t1) acquisition times is given by the following four terms (Tugarinov et al. 2003; Tugarinov and Kay 2013),

| (1) |

In the absence of relaxation, SSHSQC = 3, as opposed to 12 for the ‘full’ HSQC scheme (with all transitions included). In the presence of relaxation, however, the transfer of magnetization from methyl 1H to 13C and back to 1H for detection that involve 90° 1H pulses cease to be optimal as we show in detail below.

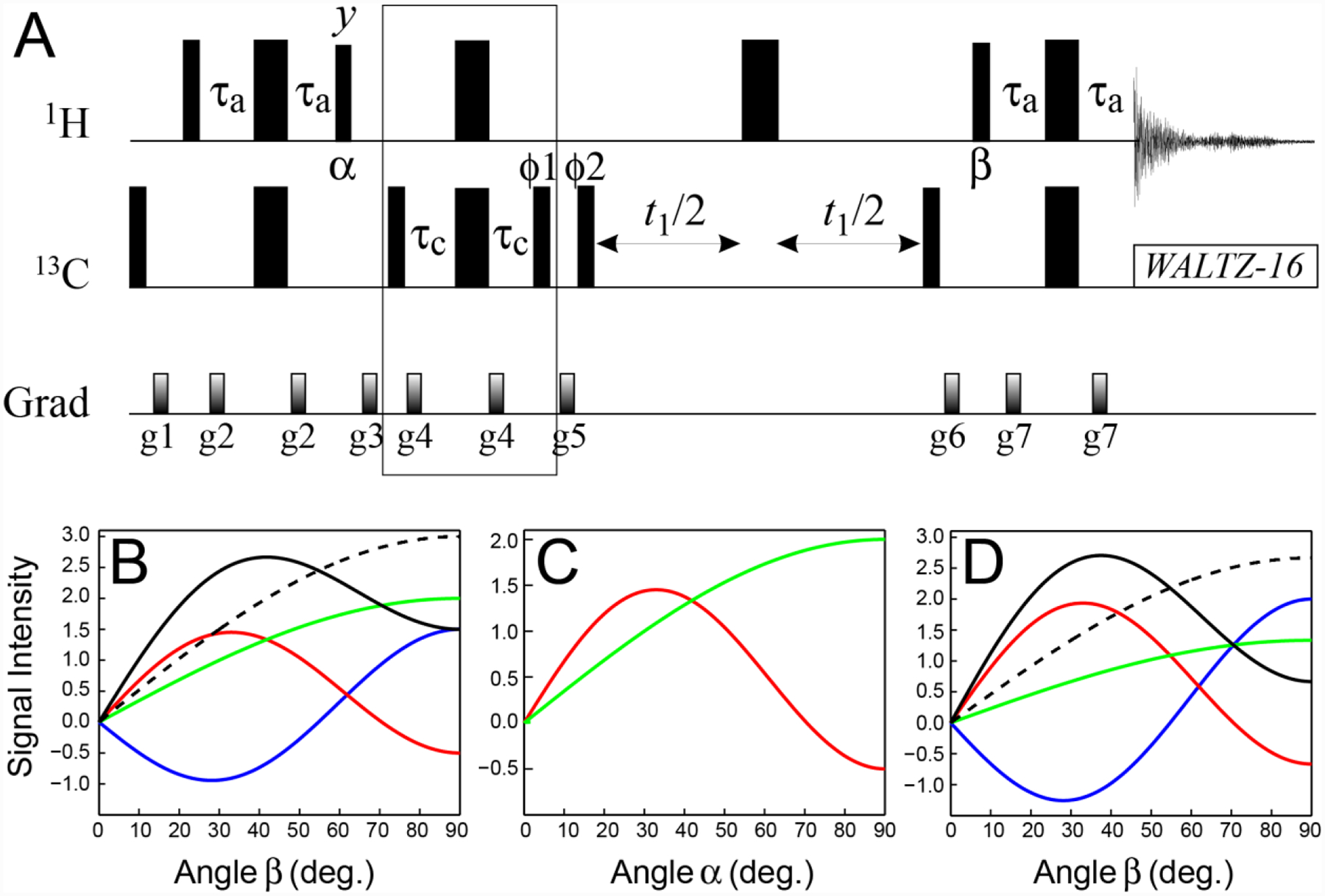

Figure 2.

(A) Pulse-scheme for selection of the slow-relaxing 13C transitions in methyl groups (SHSQC). All narrow and wide rectangular pulses are applied with flip angles of 90° and 180°, respectively, along the x-axis unless indicated otherwise. The 1H and 13C carrier frequencies are positioned in the center of the Ileδ1-Leu-Val methyl region (0.5 and 20 ppm, respectively). All 1H and 13C pulses are applied with the highest possible power, while 13C WALTZ-16 decoupling (Shaka et al. 1983) is achieved using a 2-kHz field. Delays are: τa = 1/(4JHC) = 2.0 ms, τc = 1/(12JHC) = 0.67 ms. The durations and strengths of pulsed-field gradients in units of (ms; G/cm) are: g1 = (1; 25), g2 = (0.5; 15), g3 = (1.5; 15), g4 = (0.4; 20), g5 = (1.0; 20), g6 = (0.8; −20), g7 = (0.5; 12). The phase cycle is: ϕ1 = 2(x),2(−x); ϕ2 = x,−x; receiver phase = (x,−x,−x,x). Quadrature detection in t1 is achieved via States-TPPI (Marion et al. 1989) incrementation of ϕ2. (B–D) Signal intensities (arbitrary units) of the fast-relaxing SQ 1H/13C transitions (blue curves), and the slow-relaxing SQ 1H/13C transitions of the I = 3/2 (red curves) and I = 1/2 (green curves) manifolds calculated for (B) the first direct acquisition point (t2 = 0) of the SHSQC experiment shown in panel A as a function of the angle β (deg.); (C) the first point in the indirect (13C) dimension (t1 = 0) as a function of the angle α (deg.) following selection of the slow-relaxing 1H transitions; (D) the first direct acquisition point (t2 = 0) as a function of the angle β after selection of the slow-relaxing 1H transitions with an optimal angle α, followed by selection of the slow-relaxing 13C transitions before t1. In panels (B) and (D) black solid curves show intensities originating from the slow-relaxing 1H and 13C transitions of the sum of the I = 3/2 and I = 1/2 manifolds, while the dashed black curves show the total signal intensity from all 1H transitions (including the fast-relaxing ones shown in blue). All calculations were performed in the absence of relaxation.

It is instructive to first consider how each of the components of methyl 1H magnetization to be detected in the end of the SHSQC experiment varies as a function of the angles of the two 1H pulses responsible for the transfer of magnetization to and from 13C nuclei, which are labeled in Figure 2A by α and β, respectively. Note that α = β = 90° in the SHSQC scheme. The 1H magnetization detected in the SHSQC experiment is decomposed onto its ‘substituents’ for angle β varied between 0 to 90° in the absence of relaxation in Figure 2B (with α kept fixed at 90°). When β = 90°, one-half of the total detected signal represented by the dashed black curve, derives from the fast-relaxing 1H transitions (blue curves), while the other half derives from the slow-relaxing 1H transitions (red and green curves for the transitions of the I = 3/2 and I = 1/2 manifolds, respectively, and solid black curve for their sum). Although relaxation is not considered in the plots of Figure 2B, it is clear that in the presence of relaxation, this scenario will lead to a fast decay of one half of the 1H magnetization during the 2τa and t2 periods. This situation can be remedied by selecting the slow-relaxing 1H coherences before acquisition and adjusting the angle β to the maximum of the signal arising from these coherences (the maximum of the black curve in Figure 2B). The loss of signal associated with such a scheme is small even in the absence of relaxation -calculated to be 1/9 of the total signal (cf. the maxima of the solid and dashed black curves in Figure 2B), and can be expected to be readily compensated for by slower relaxation of the (remaining) 1H coherences even in small protein molecules.

Perhaps fortuitously, when the slow-relaxing part of the 1H magnetization is selected before acquisition as described above, there is no ‘penalty’ to be paid for the same selection after the first INEPT period (when methyl 1H magnetization is transferred to 13C at the beginning of the experiment) if the angle α of the corresponding 1H pulse (Figure 2A) is adjusted to an optimal value. This observation can be rationalized by reference to the simpler case of the SHSQC experiment with 90° 1H pulses. If only the magnetization corresponding to the last two terms in Eq. (1) (i.e. 1H coherences relaxing slowly during the last 2τa and t2 periods) is retained, then an additional selection for the slow-relaxing 1H magnetization ‘on the way’ to 13C - i.e. elimination of the last, negative term in Eq. (1) - will only increase the observed signal. Figure 2C shows the magnitude of 13C magnetization arising from 13C transitions of the I = 3/2 (red) and I = 1/2 (green) manifolds for the first point in the indirect dimension (t1 = 0) as a function of the angle α of the 1H pulse following isolation of the slow-relaxing 1H transitions, while the (detected) 1H magnetization at the first point in the acquisition dimension (t2 = 0) when the angle α is adjusted to its optimal value, is shown in Figure 2D as a function of angle β using the same color code as in Figure 2B. Note that there is an (ever so slight, ~1 %) actual gain in signal intensity obtained after the slow-relaxing 1H transitions are selected and the angle α is adjusted to its optimal value before the magnetization is transferred to 13C nuclei (cf. the maxima of the solid black curves in Figures 2B and 2D).

Keeping in mind all the considerations discussed above, we proceeded to design a pulse scheme that achieves optimal selection of the slow-relaxing SQ 13C transitions in 13CH3 methyl groups (Figure 3A). The experiment starts with selection of the slow-relaxing 1H transitions followed by a 1Hy α-angle pulse (the element enclosed in the first dashed box in Figure 3A with the α pulse shown in green). As described in more detail in the Supplementary Information, the intensities of the peaks arising from the slow-relaxing 13C transitions after the 1H pulse with angle α, PS, are given by,

| (2) |

where the first two terms correspond to the two 13C transitions of the I = 3/2 manifold (), and the last term - to the four 13C transitions of the I = 1/2 manifold (). Differentiating the expression in Eq. (2) with respect to angle α and equating the derivative to 0, dPS/dα = 0, yields the optimal angle αopt = sin−1(2/3) = 41.8°. For α = αopt, the contributions to 13C magnetization from and are the same and equal to 4/3 (corresponding to the intersection point of the red and green curves in Figure 2C).

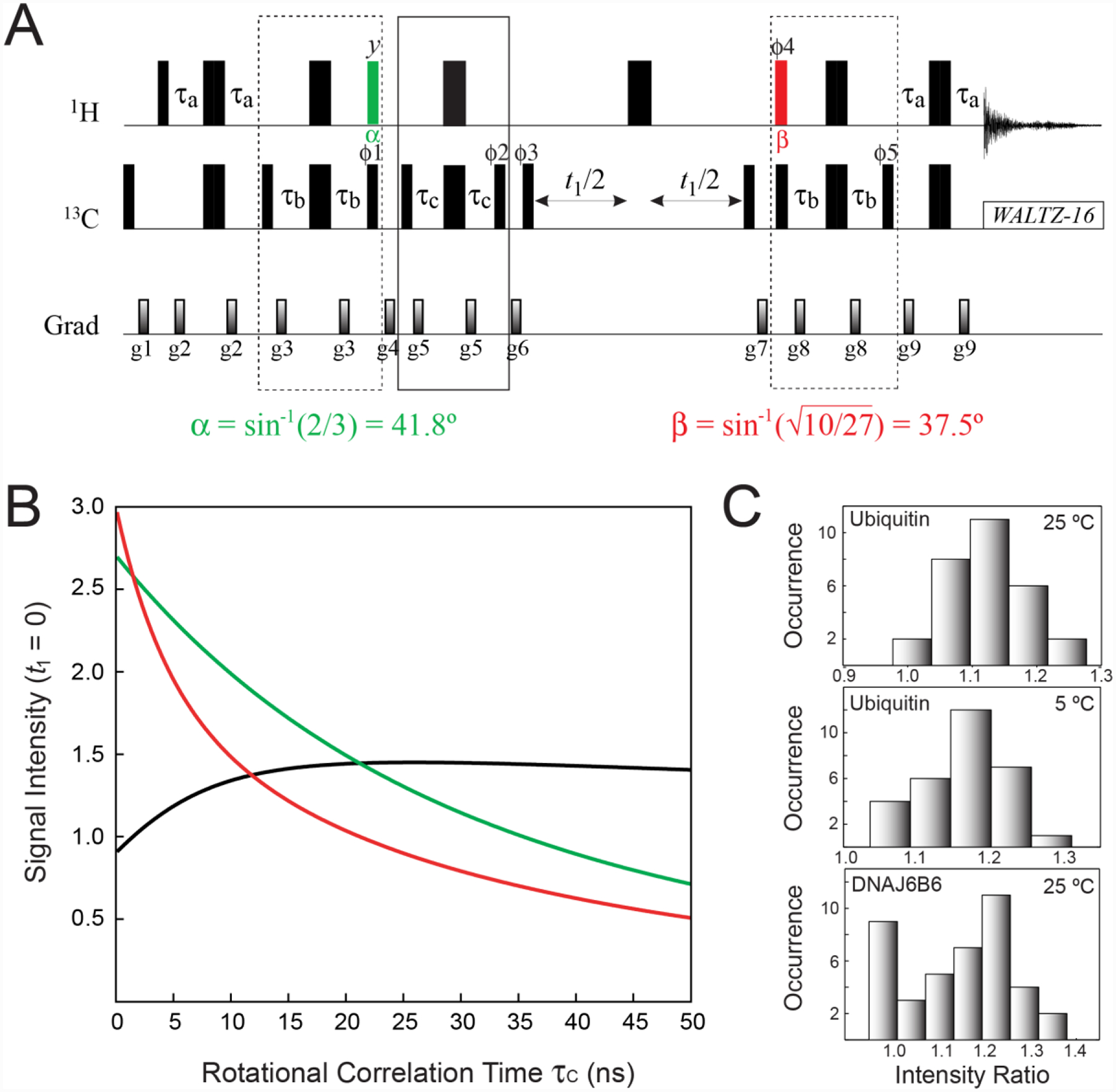

Figure 3.

(A) Pulse scheme for the optimal selection of the slow-relaxing 13C transitions in 13CH3 methyl groups. All the parameters of the scheme are as described in Figure 2A. The 1H pulse shown in green is applied with flip angle α = sin−1(2/3) = 41.8°, while the pulse shown in red is applied with flip angle . The delay τb = 1/(8JHC) = 1.0 ms. The durations and strengths of pulsed-field gradients in units of (ms; G/cm) are: g1 = (1; 25), g2 = (0.4; 15), g3 = (0.5; 12), g4 = (0.8; 25), g5 = (0.4; 10), g6 = (1.5; 20), g7 = (0.7; −20), g8 = (0.5; 15), g9 = (0.4; 10). The phase cycle is: ϕ1 = 4(x),4(−x); ϕ2 = 2(x),2(−x); ϕ3 = x, −x; ϕ4 = 4(x),4(−x); ϕ5 = 4(x),4(−x); receiver phase = (x, −x, −x,x, −x,x,x, −x). Quadrature detection in t1 is achieved via States-TPPI incrementation of ϕ3. (B) Signal intensities (arbitrary units) for the first point of the indirect acquisition dimension (t1 = 0) calculated for the experiment in A (green curve), the SHSQC scheme in Figure 2A (red curve), and the ratio of the two (black curve) plotted as a function of the molecular rotational correlation time τC (ns). Expressions for relaxation rates were taken from (Tugarinov and Kay 2013), with a single external 1H spin placed at a distance of 3.0 Å from methyl protons, and the order parameters of the methyl three-fold axis, S2axis, set to 0.6. Note that the red curve follows the expression in Eq. (1) for t1 = 0. Calculations were performed using the integral form of exp(−R2t2) equal to [1 − exp(−R2t2,max)]/(R2t2,max), where t2,max = 65 ms, and R2 is the transverse relaxation rate of the corresponding 1H transitions (RS2H or RF2H). (C) Histograms of experimental peak intensity ratios obtained for the experiment in panel A and the SHSQC experiment (see Figure 2A) for ubiquitin at 5 and 25 °C and the chaperone ΔST-DNAJB6b at 25 °C. Sample conditions and NMR acquisition parameters are described in the ‘Materials and Methods’ section of the Supplementary Information.

Subsequently, the magnetization is transferred to 13C nuclei, and the slow-relaxing, inner 13C transitions are isolated before the indirect acquisition period t1 (the element enclosed in the solid box in Figure 3A). The transfer of magnetization back to protons for detection starts with the 1Hϕ4 pulse applied with angle β followed again by selection of the slow-relaxing 1H transitions (the element enclosed in the second dashed box in Figure 3A, with the β-angle pulse shown in red). The signal detected at the end of the experiment, SS, is given by (see Supplementary Information for details),

| (3) |

where the first two terms correspond to the two SQ 1H transitions of the I = 3/2 manifold (), and the last term to the four SQ 1H transitions of the I = 1/2 manifold (). Since for α = αopt, , differentiating the expression in Eq. (3) with respect to β and equating the derivative to 0, dSS/dβ = 0, gives, . When the angles α and β are adjusted to their optimal values (αopt; βopt), the total signal SS is equal to , i.e. more than 90 % of the signal in the SHSQC experiment (equal to 3, see Eq. (1)) is retained in the absence of relaxation.

As the slow-relaxing 1H and 13C transitions are actively isolated and selected for in an optimal manner at each stage of the experiment (before the t1 and t2 acquisition periods), the scheme in Figure 3A effectively represents a single-quantum implementation of the methyl-TROSY experiment (Tugarinov et al. 2003) and, as such, is predicted to be more tolerant to transverse spin relaxation than the SHSQC experiment. Figure 3B shows the plots of signal intensities of the first point of the indirect acquisition dimension (t1 = 0) calculated for the scheme in Figure 3A (green), the SHSQC experiment in Figure 2A (red) and the ratio of the two (black), plotted as a function of molecular rotational correlation time τC. Note that the red curve follows the expression in Eq. (1) for t1 = 0. Clearly, ~10 % lower sensitivity of the scheme in Figure 3A in the absence of relaxation (τC → 0) is predicted to transform to sensitivity gains for τC values higher than ~2 ns (corresponding to the correlation time of the smallest of folded proteins), reaching close to ~50 % for larger systems (higher τC values).

Figure 3C shows histograms of peak intensity ratios obtained for the experiment of Figure 3A and the SHSQC scheme (Figure 2A) for ILV-{13CH3}-labeled ubiquitin at 25 °C (τC ~ 5 ns in D2O; average ratio = 1.12 ± 0.06) and 5 °C (τC ~ 11 ns in D2O; average ratio = 1.17 ± 0.07), and ILV-{13CH3}-ΔST-DNAJB6b at 25 °C (‘apparent’ τC ~ 16 ns and 25 ns for the two independently tumbling domains (Tugarinov et al. 2020b); average ratio = 1.20 ± 0.08 after exclusion of the 9 very flexible methyl sites that do not show sensitivity gains due to only minor relaxation effects). Although these sensitivity gains are quite modest and fall short of those predicted based on the plot in Figure 3B (mainly, due to inclusion of 8 additional RF pulses and relaxation losses during the total of 4τb periods in the elements enclosed in dashed boxes in the scheme of Figure 3A), they are realized even for small protein molecules, such as ubiquitin at room temperature, as well as for exchanging systems, such as ΔST-DNAJB6b that undergoes inter-conversion between the major monomeric species and sparsely-populated high-molecular-weight oligomers (Karamanos et al. 2019).

Several applications that would benefit from selection of the slow-relaxing 13C transitions in methyl groups of proteins can be envisaged. For example, the quantitative measurement of methyl 1H-13C residual dipolar couplings in the indirect dimension of 1H-13C correlation spectra, as well as their direct measurements from the splitting of the methyl 1H-13C doublet, can be achieved by sequestering all slow-relaxing 13C transitions and, in principle, do not require isolating transitions of the I = 1/2 manifold described by us earlier (Tugarinov et al. 2020a). Here, instead, we focus on methyl 13C SQ CPMG relaxation dispersion measurements (Lundström et al. 2007). Figure 4A shows the pulse-scheme for recording methyl 13C SQ CPMG relaxation dispersion profiles with optimal selection of slow-relaxing 13C transitions using the ‘building blocks’ developed above for the experiment in Figure 3A. Examples of methyl 13C relaxation dispersion profiles obtained with the scheme in Figure 4A are compared with those recorded using the experiment developed earlier by Lundström et al. (2007) where all 13C methyl coherences are present during CPMG delays, in Figure 4B for ILV-{13CH3}-ubiquitin at 5 °C, and in Figure 4C for ILV-{13CH3}-ΔST-DNAJB6b at 15 °C. (Note a temperature of 15 °C was chosen as the dispersions are larger than at 25 °C).

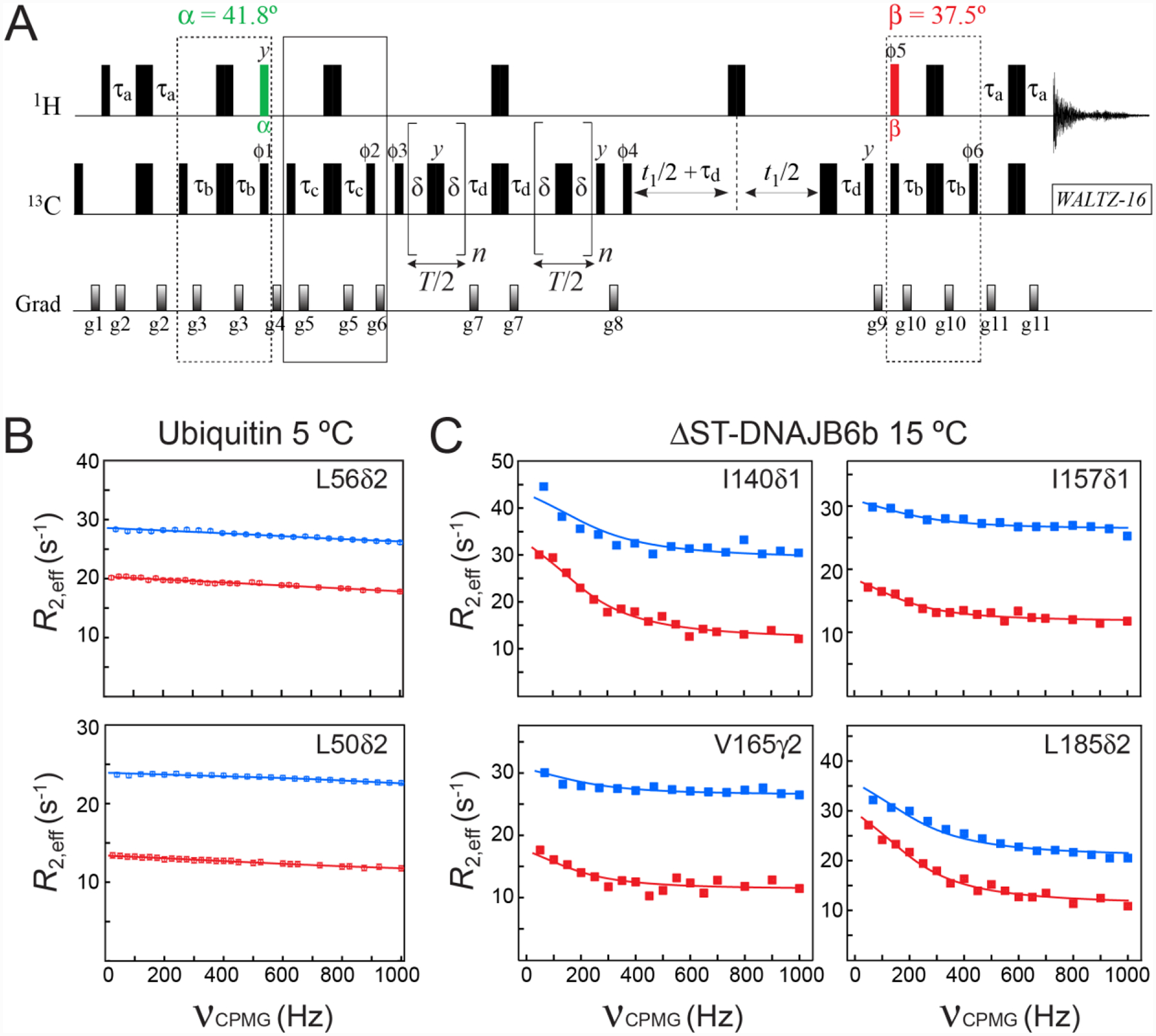

Figure 4.

(A) Pulse scheme for methyl 13C SQ CPMG relaxation dispersion experiment with optimal selection of slow-relaxing 13C transitions. All the parameters of the scheme are as described in Figures 2A and 3A. The delay τd = 1/(4JHC) = 2.0 ms. T is the CPMG constant time relaxation delay. Even number of CPMG cycles (180° 13C pulses) n should be used for each relaxation period T/2. The durations and strengths of pulsed-field gradients in units of (ms; G/cm) are: g1 = (1.0; 25), g2 = (0.5; 15), g3 = (0.3; 20), g4 = (1.5; 25), g5 = (0.25; 15), g6 = (1.2; 20), g7 = (0.5; 20), g8 = (0.6; 20), g9 = (0.8; −25), g10 = (0.3; 20), g11 = (0.5; 20). The phase cycle is: ϕ1 = 8(x),8(−x); ϕ2 = 4(x),4(−x); ϕ3 = 2(x),2(−x); ϕ4 = x,-x; ϕ5 = 8(x),8(−x); ϕ6 = 8(x),8(−x); receiver = (x, −x, −x,x, 2(−x,x,x, −x), x, −x, −x,x). Quadrature detection in t1 is achieved via States-TPPI incrementation of ϕ4. (B–C) Examples of methyl 13C relaxation dispersion profiles obtained for (B) ubiquitin at 5 °C, and (C) ΔST-DNAJB6b at 15 °C are shown in red. The corresponding profiles obtained with the scheme of Lundström et al. (2007) that does not select the slow-relaxing 13C transitions, are shown in blue. The best fits to a two-state exchange model are shown as continuous lines. In the case of ΔST-DNAJB6b, exchange occurs between the major monomeric state and a sparsely-populated, high-molecular-weight oligomer comprising 30–40 monomeric units (Karamanos et al. 2019). Sample conditions, the parameters of NMR experiments and the details of the fitting procedure are described in the ‘Materials and Methods’ section of the Supplementary Information.

Although sensitivity losses associated with selection of the slow-relaxing 13C transitions are substantial (an average factor of 3.2 was measured for the cross-peaks of both protein samples in favor of the scheme of Lundström et al. (2007) for the reference plane (T = 0), while these losses decrease to the average factor of ~1.9 for relaxation delays T of 50 ms and 30 ms for ubiquitin and ΔST-DNAJB6b, respectively, at the highest CPMG frequency), the effective transverse relaxation rates, R2,eff, are significantly lower for the profiles recorded with selection of the slow-relaxing 13C coherences in both proteins. Lower R2,eff rates translate into longer constant-time CPMG relaxation periods that can be used in these experiments permitting (1) CPMG relaxation dispersion studies of slower exchange processes, as well as (2) better sampling of the relaxation dispersion profiles. In fact, the constant-time relaxation delay T in the experiment of Figure 4A could be increased from 50 to 80 ms for ubiquitin and from 30 to 50 ms for ΔST-DNAJB6b.

For ubiquitin, there are only two methyl sites (Leu50δ2 and Leu56δ2; Figure 4B) that show weak relaxation dispersion (the difference between R2,eff at 0 and the highest CPMG frequency, Rex ~ 2 s−1), reflecting a fast exchange process likely involving inter-conversion between two or more side-chain conformations (Massi et al. 2005). For the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the ΔST-DNAJB6b chaperone, which was shown earlier to be implicated in association with high-molecular-weight oligomeric species comprising 30–40 monomeric units (Karamanos et al. 2019), methyl 13C relaxation dispersions are more abundant. It is important to note that the intrinsic (exchange-free) transverse relaxation rates R2 are reduced as a result of selection of the slow-relaxing 13C components in both the major, observable (monomeric) species of ΔST-DNAJB6b and the sparsely populated, high-molecular-weight oligomers. The resulting decrease in the population-weighted average R2 profoundly affects the relaxation dispersion profiles (Baldwin et al. 2012) significantly increasing their exchange-related information content. This is clearly observed for the relaxation dispersion profiles of Ile140δ1, Val165γ2 and Leu185δ2 of ΔST-DNAJB6b which show higher Rex values in the data recorded with selection of the slow-relaxing 13C components (Figure 4C). We note that the profiles obtained with and without selection of the slow-relaxing 13C components can be fitted together using the same parameters of exchange but separate intrinsic relaxation rates of the involved species. Specifically, while the rate constants of exchange can be shared between the relaxation dispersion profiles recorded with and without selection of the slow-relaxing 13C components, different sets of R2 values of the major (R2,A) and minor, high-molecular-weight (R2,B) states are required for analysis of these two types 13C relaxation dispersion experiments. In both cases, however, the same scaling factor was employed between the relaxation rates of interconverting species, R2,B = 30R2,A, where R2,A was a free variable parameter in the fit. Such simultaneous best-fits of the CPMG profiles of the four methyl sites of ΔST-DNAJB6b in Figure 4C to a 2-state model of exchange yields an exchange rate kex = 1050 ± 60 s−1 and a fractional population of 4.7 ± 0.4 % for the oligomeric species (200 μM ΔST-DNAJB6b, 15 °C). Considering that no meaningful parameters of exchange could be extracted from the best-fits of the data without selection of the slow-relaxing 13C transitions alone for the same set of methyl sites (blue profiles in Figure 4C), this clearly illustrates the benefits of reduced R2 (and, hence, R2,eff) relaxation rates in CPMG relaxation dispersion experiments that target exchanging systems with at least one high-molecular-weight player.

In summary, a further demonstration of the utility of acute angle pulses in methyl NMR is provided by the design of pulse schemes incorporating optimized selection of the slow-relaxing components of SQ 13C magnetization in 13CH3 methyl groups of selectively methyl-protonated, highly deuterated proteins. The optimized selection scheme is more relaxation-tolerant and provides some sensitivity gains in comparison to the experiment where the undesired (fast-relaxing) components of 13C magnetization are simply ‘filtered-out’ of the picture, and only 90° 1H pulses are employed to transfer the magnetization to and from 13C nuclei. We show that isolation of the slow-relaxing components of 13C magnetization results in retrieval of the information content of 13C SQ CPMG relaxation dispersion profiles obscured by high intrinsic relaxation rates (high molecular weights) of one of the species involved in exchange.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement.

We thank Drs. James Baber, Jinfa Ying and Dan Garrett for technical support. This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (DK029023 to G.M.C.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Supplementary Information. Density matrix analysis of the scheme in Figure 3A leading to the derivation of optimal values of α/β 1H pulse angles. ‘Materials and Methods’ describing NMR sample conditions and acquisition parameters of NMR experiments.

References

- Baldwin AJ, Walsh P, Hansen DF, Hilton GR, Benesch JL, Sharpe S, Kay LE (2012) Probing dynamic conformations of the high-molecular-weight αB-crystallin heat shock protein ensemble by NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc 134:15343–15350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhausen G, Ruben DJ (1980) Natural abundance 15N NMR by enhanced heteronuclear spectroscopy. Chem Phys Lett 69:185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Carr HY, Purcell EM (1954) Effects of diffusion on free precession in nuclear magnetic resonance experiments. Phys Rev 4:630–638. [Google Scholar]

- Karamanos TK, Tugarinov V, Clore GM (2019) Unraveling the structure and dynamics of the human DNAJB6b chaperone by NMR reveals insights into Hsp40-mediated proteostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:21529–21538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamanos TK, Tugarinov V, Clore GM (2020) Determining methyl sidechain conformations in a CS-ROSETTA model using methyl 1H-13C residual dipolar couplings. J Biomol NMR 74:111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontaxis G, Bax A (2001) Multiplet component separation for measurement of methyl 13C-1H dipolar couplings in weakly aligned media. J Biomol NMR 20:77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundström P, Vallurupalli P, Religa TL, Dahlquist FW, Kay LE (2007) A single-quantum methyl 13C-relaxation dispersion experiment with improved sensitivity. J Biomol NMR 38:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion D, Ikura M, Tschudin R, Bax A (1989) Rapid recording of 2D NMR spectra without phase cycling: application to the study of hydrogen exchange in proteins. J Magn Reson 85:393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Massi F, Grey MJ, Palmer AG (2005) Microsecond timescale backbone conformational dynamics in ubiquitin studied with NMR R1ρ relaxation experiments. Protein Sci. 14:735–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiboom S, Gill D (1958) Modified spin-echo method for measuring nuclear relaxation times. Rev Sci Instrum 29:688–691. [Google Scholar]

- Morris GA, Freeman R (1979) Enhancement of nuclear magnetic resonance signals by polarization transfer. J Am Chem Soc 101:760–762. [Google Scholar]

- Ottiger M, Delaglio F, Marquardt JL, Tjandra N, Bax A (1998) Measurement of dipolar couplings for methylene and methyl sites in weakly oriented macromolecules and their use in structure determination. J Magn Reson 134:365–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig R, Kay LE (2014) Bringing dynamic molecular machines into focus by methyl-TROSY NMR. Annu Rev Biochem 83:291–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schütz S, Sprangers R (2020) Methyl TROSYspectroscopy: a versatile NMR approach to study challenging biological systems. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc 116:56–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaka AJ, Keeler T, Frenkiel T, Freeman R (1983) An improved sequence for broadband decoupling: Waltz-16. J Magn Reson 52:335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Tugarinov V, Hwang PM, Kay LE (2004) Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of high-molecular-weight proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 73:107–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugarinov V, Hwang PM, Ollerenshaw JE, Kay LE (2003) Cross-correlated relaxation enhanced 1H-13C NMR spectroscopy of methyl groups in very high molecular weight proteins and protein complexes. J Am Chem Soc 125:10420–10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugarinov V, Karamanos TK, Ceccon A, Clore GM (2020a) Optimized NMR experiments for the isolation of I=1/2 manifold transitions in methyl groups of proteins. Chemphyschem 21:13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugarinov V, Karamanos TK, Clore GM (2020b) Magic-angle-pulse driven separation of degenerate 1H transitions in methyl groups of proteins: Application to studies of methyl axis dynamics. Chemphyschem 21:1087–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugarinov V, Kay LE (2007) Separating degenerate 1H transitions in methyl group probes for single-quantum 1H-CPMG relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc 129:9514–9521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugarinov V, Kay LE (2013) Estimating side-chain order in [U-2H;13CH3]-labeled high molecular weight proteins from analysis of HMQC/HSQC spectra. J Phys Chem B 117: 3571–3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.