Abstract

Efficient symbiotic colonization of the squid Euprymna scolopes by the bacterium Vibrio fischeri depends on bacterial biofilm formation on the surface of the squid’s light organ. Subsequently, the bacteria disperse from the biofilm via an unknown mechanism and enter through pores to reach interior colonization sites. Here, we identify a homolog of Pseudomonas fluorescens LapG as a dispersal factor that promotes cleavage of a biofilm-promoting adhesin, LapV. Overproduction of LapG inhibited biofilm formation and, unlike the wild-type parent, a ΔlapG mutant formed biofilms in vitro. Although V. fischeri encodes two putative large adhesins, LapI (near lapG on chromosome II) and LapV (on chromosome I), only the latter contributed to biofilm formation. Consistent with the Pseudomonas Lap system model, our data support a role for the predicted c-di-GMP-binding protein LapD in inhibiting LapG-dependent dispersal. Furthermore, we identified a phosphodiesterase, PdeV, whose loss promotes biofilm formation similar to that of the ΔlapG mutant and dependent on both LapD and LapV. Finally, we found a minor defect for a ΔlapD mutant in initiating squid colonization, indicating a role for the Lap system in a relevant environmental niche. Together, these data reveal new factors and provide important insights into biofilm dispersal by V. fischeri.

Keywords: Vibrio fischeri, Euprymna scolopes, Biofilm, Dispersal, Lap, c-di-GMP

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial biofilms are associated with a wide range of human and animal infections. Anti-biofilm measures are complicated by the natural recalcitrance of biofilms to antibiotic treatment via tolerance mechanisms that include restricted access to cells within biofilms and the presence of persister cells (Ciofu et al., 2017). Bacteria naturally disperse from biofilms under conditions that favor planktonic growth (Petrova and Sauer, 2016). Understanding bacterial strategies for dispersal will provide alternative avenues for preventing or treating biofilm-related infections.

Bacterial strategies to disperse from biofilms include the degradation of biofilm matrix proteins (Petrova and Sauer, 2016, McDougald et al., 2011). For example, adhesins that facilitate biofilm formation when associated with the cell surface can be proteolytically processed, and the release of these surface-associated proteins promotes biofilm dispersal. The protease LapG regulates biofilm dispersal in this way and is located in the periplasm of several Gram-negative bacteria (Rybtke et al., 2015, Gjermansen et al., 2005, Newell et al., 2011, Ambrosis et al., 2016, Chatterjee et al., 2012, Zhou et al., 2015, Kitts et al., 2019). LapG mediates dispersal through the cleavage and release of large adhesive proteins including LapA in Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas fluorescens, CdrA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, BrtA in Bordetella bronchiseptica, BpfA in Shewanella oneidensis, and FrhA and CraA in Vibrio cholerae (Fig. 1A) (Newell et al., 2011, Gjermansen et al., 2010, Rybtke et al., 2015, Ambrosis et al., 2016, Zhou et al., 2015, Kitts et al., 2019). The LapG-dependent cleavage of these targets is regulated by LapD, which sequesters the protease, allowing for maintenance of adhesins on the cell surface during biofilm-forming conditions (Newell et al., 2011, Chatterjee et al., 2012, Kitts et al., 2019). Based on sequence similarity, LapG and LapD homologs are predicted to be present in Vibrio fischeri (Navarro et al., 2011).

Figure 1. The Lap regulatory system in model organisms and V. fischeri.

(A) In Pseudomonas fluorescens and other organisms, biofilm formation and dispersal are mediated by the proteolytic activity of LapG. Biofilm formation occurs when large adhesins are present on the cellular surface and LapG is sequestered by LapD in response to high c-di-GMP. A large adhesin (in V. fischeri, LapV) is translocated from across the inner membrane (IM) and outer membrane (OM) to the cell surface by a three component T1SS apparatus composed of LapB (ATPase), LapC (membrane fusion protein), and LapE (outer membrane pore). Biofilm dispersal is induced upon inactivation of LapD via degradation of c-di-GMP by a phosphodiesterase (in V. fischeri, PdeV). The inactivation of LapD relieves sequestration of LapG and permits cleavage (indicated by scissors) of adhesin LapV. High environmental calcium (grey circles) appears to be a condition where this system is active. (B) Lap operon and genomic context of lapV in V. fischeri. (C) LapI domain architecture. The putative LapG cleavage site (PAAG) is in indicated by a thin vertical line on the left (red). (D) LapV domain architecture. The putative LapG cleavage site (TAAG) is in indicated by a thin vertical line on the left (red).

Vibrio fischeri is a marine bacterium that participates in a symbiotic relationship with the Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes (Stabb and Visick, 2013, McFall-Ngai, 2008, McFall-Ngai, 2014b, McFall-Ngai, 2014a). The symbiosis is established when V. fischeri colonizes the light-emitting organ of newly hatched E. scolopes. Biofilm formation and dispersal are key steps that precede colonization: V. fischeri forms a transient biofilm on the surface of the E. scolopes light organ, from which cells must disperse before migrating into the light organ to reach the sites of colonization (Nyholm et al., 2000). Biofilm formation requires production of the symbiosis polysaccharide (Syp), which is regulated and synthesized by the 18-gene syp locus (Yip et al., 2005, Shibata et al., 2012), and cellulose, whose synthesis is encoded by bcs (bacterial cellulose synthesis) genes (Tischler et al., 2018, Bassis and Visick, 2010). However, it is unknown what environmental and/or host-derived signals are required for the lifestyle changes necessary for the symbiosis.

The majority of V. fischeri biofilm studies have used strain ES114, which forms biofilms in the squid, but only poorly under routine laboratory conditions. However, this strain can form substantial biofilm when genetically manipulated to overproduce Syp polysaccharide, such as by overexpression of the positive biofilm regulator rscS or disruption of the negative regulator binK (Yip et al., 2006, Tischler et al., 2018, Brooks and Mandel, 2016). These two-component regulators are part of a complex but incompletely-defined regulatory network with unknown signals that result in induction of polysaccharide production (Thompson et al., 2018, Thompson et al., 2019, Tischler et al., 2018). Despite these gaps in knowledge, calcium has emerged as an important signal for V. fischeri biofilm formation (Marsden et al., 2017, Tischler et al., 2018). In shaking liquid culture, calcium promotes two biofilm-like phenotypes: rings at the air-liquid interface and cohesive clumps that settle to the bottom of culture vessels (Tischler et al., 2018). These phenotypes positively correlate with biofilms formed in other established laboratory assays (e.g., host-associated biofilms, wrinkled colonies, and pellicles). In addition, calcium increases expression of both of the major V. fischeri biofilm polysaccharide loci (syp and bcs) (Tischler et al., 2018). While calcium promotes biofilm formation by genetically-altered ES114, the wild-type parent fails to form robust biofilms in calcium-containing media (e.g., shaking cultures or agar plates), suggesting that this strain is either not producing something necessary for the biofilm structure, actively producing factors to disperse, or both.

Using the calcium-dependent biofilm phenotypes, we set out to investigate the unexplored process of V. fischeri dispersal and the role of putative Lap system homologs. Our work demonstrates that the V. fischeri LapG homolog promotes biofilm dispersal through cleavage of a large surface adhesin that we designate as LapV. We determined that LapG activity influences V. fischeri to disperse under multiple laboratory conditions and that LapG-dependent dispersal can be inhibited by LapD. Furthermore, dispersal in wild-type ES114 is driven by degradation of the second messenger c-di-GMP by the phosphodiesterase, PdeV. We assert that this pathway explains, at least in part, the failure of wild-type V. fischeri to form calcium-dependent biofilms, despite its competence to form biofilms in the context of its squid host.

RESULTS

V. fischeri contains a Lap locus and two genes encoding large adhesins.

We hypothesized that V. fischeri could promote biofilm dispersal using factors that regulate dispersal in other organisms, such as the Lap system found in P. fluorescens, P. putida, and others (Fig. 1A). Bioinformatics searches for candidates with possible Lap system roles identified seven putative lap genes located in the VF_A1162-VF_A1168 locus on chromosome II, the smaller, niche-specific chromosome (Fig. 1B) (Navarro et al., 2011, Ruby et al., 2005). VF_A1162 encodes a large (3,933 amino acids) putative adhesin that contains a T1SS target sequence presumed to promote its export, several extracellular localization domains, multiple adhesion domains (e.g., cadherin tandem repeat domains), and a putative proteolytic cleavage sequence identical to that shown to be required for cleavage of FrhA of V. cholerae (Kitts et al., 2019) (Fig. 1C). VF_A1167 encodes a putative transglutaminase-like cysteine protease homologous to P. fluorescens LapG (51% identity and 70% similarity), which recognizes a specific motif and cleaves a large adhesive protein (Newell et al., 2011). V. fischeri LapG contains the conserved catalytic residues required for proteolytic cleavage, as well as the conserved residues shown to be involved in calcium-binding by Legionella pneumophila LapG (Fig. S1) (Chatterjee et al., 2012, Ginalski et al., 2004). VF_A1166 encodes a putative LapD protein, with a cytoplasmic portion containing degenerate GGDEF and EAL domains and a periplasmic domain connected via a HAMP domain, sharing 25% sequence identity (47% similarity) with P. fluorescens LapD (Fig. S2). The remaining genes in the locus encode a putative porin, encoded by VF_A1164, and three predicted type I secretion system components encoded by VF_A1168, VF_A1165, and VF_A1163. VF_A1168 is a homolog of the membrane fusion protein, LapC (42% identity, 62% similarity) (Hinsa et al., 2003). VF_A1165 shares homology with LapB, which is an ABC transporter (43% identity, 64% similarity) (Monds et al., 2007, Hinsa et al., 2003). Finally, VF_A1163 is a LapE homolog that, in P. fluorescens, is hypothesized to retain LapA on the cell surface (37% identity, 57% similarity) (Hinsa et al., 2003). We hypothesized that this locus encodes functional Lap system homologs, and we refer to them using their Lap nomenclature, based on evidence presented below; because VF_A1162 lacks sequence similarity to well-characterized adhesins like LapA from P. fluorescens and LapF from P. putida, we designate VF_A1162 as LapI due to its 15 Immunoglobulin-like repeats.

LapG negatively affects V. fischeri biofilm formation.

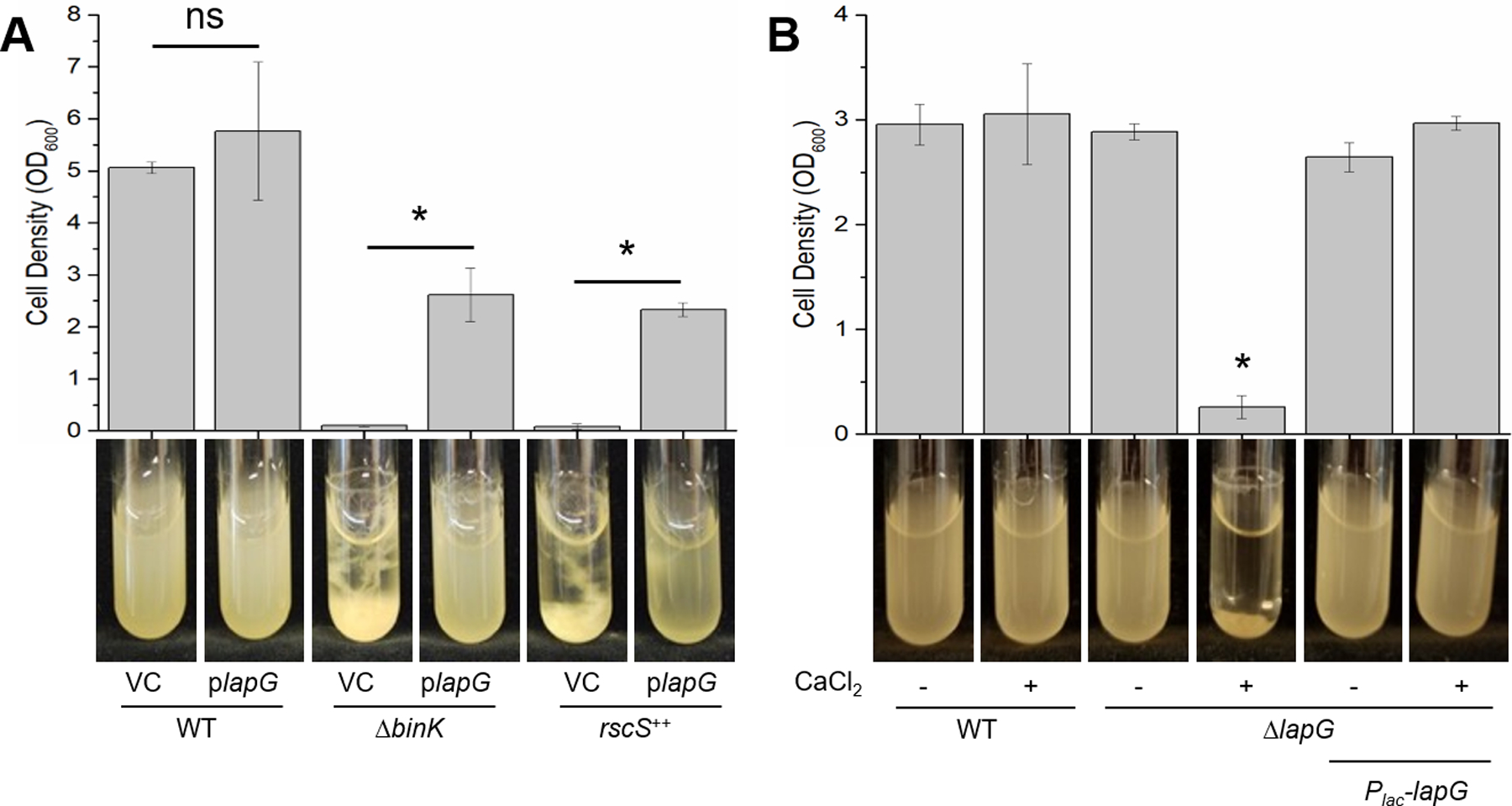

In P. fluorescens, LapG promotes biofilm dispersal by cleaving the adhesin LapA, thus releasing the protein from the cell surface (Fig. 1A) (Newell et al., 2009, Newell et al., 2011). Based on this model, we predicted that overproduction of V. fischeri LapG might similarly promote biofilm dispersal. We tested this possibility using derivatives of V. fischeri ES114 that form biofilms under laboratory conditions, including a ΔbinK mutant and an rscS-overexpressing strain (rscS++). When grown with shaking in liquid cultures supplemented with calcium, these strains produce rings and cohesive cellular clumps, while wild-type V. fischeri grows as a turbid culture (Fig. 2A) (Tischler et al., 2018). Introduction of the lapG overexpression plasmid plapG severely diminished biofilm formation by both biofilm-induced strains relative to the vector control (Fig. 2A). This result is consistent with the putative function of LapG in promoting dispersal.

Figure 2. LapG negatively affects biofilm formation.

(A) Wild-type (WT) ES114, ΔbinK (KV7860), or rscS++ (KV7655) strains carrying vector control (VC [pVSV105]) or plapG (pAEM7) were aerated in LBS containing 10 mM CaCl2 and 1 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol for 24 hours at 24°C. rscS++ indicates a strain that over-expresses rscS. Representative images of each culture are shown, and the bar graph depicts the mean optical density of the culture supernatant for three independent replicates. For each genotype, the mean cell density was compared between vector and plapG-containing strains. Comparisons are indicated by a solid bar, and an (*) indicates one-way ANOVA comparisons with p < 0.05, while (ns, not significant) indicates the resulting p-value was greater than the confidence interval. (B) WT ES114, ΔlapG (KV8593), and ΔlapG Plac-lapG (KV8727) strains were grown in LBS with or without 10 mM CaCl2 supplementation. Representative images of each culture are shown and the bar graph depicts the mean optical density of the culture supernatant for three independent replicates. An (*) Indicates p < 0.05 when the mean optical densities were compared for each strain across both growth conditions (with and without calcium) using a two-way ANOVA.

Given this result, we wondered whether LapG activity could account for the well-established inability of wild-type strain ES114 to form biofilms under similar conditions. If so, deletion of lapG from an otherwise wild-type strain would potentially prevent dispersal, and consequently permit biofilm formation. Indeed, whereas wild-type V. fischeri failed to produce a substantial biofilm, a ΔlapG mutant formed a robust ring and a cellular clump after 24 hours of growth with shaking in the presence of calcium (Fig. 2B). This biofilm phenotype was reminiscent of the characterized biofilm-competent ΔbinK mutant (Fig. 2A, Tube 3), and was similarly calcium-dependent (Fig. 2B, Tubes 3 and 4). Culture turbidity was restored when lapG was expressed under the control of a constitutive promoter from a neutral, non-native position in the chromosome, indicating the loss of lapG was responsible for the biofilm phenotype (Fig. 2B). Quantification of the culture optical densities confirmed the significant visual differences between the ΔlapG mutant and wild type when grown in the presence of calcium (Fig. 2B). Together, these results suggest that LapG inhibits calcium-dependent biofilm formation by wild-type strain ES114 and are consistent with a model in which LapG-mediated cleavage of a surface adhesin promotes dispersal.

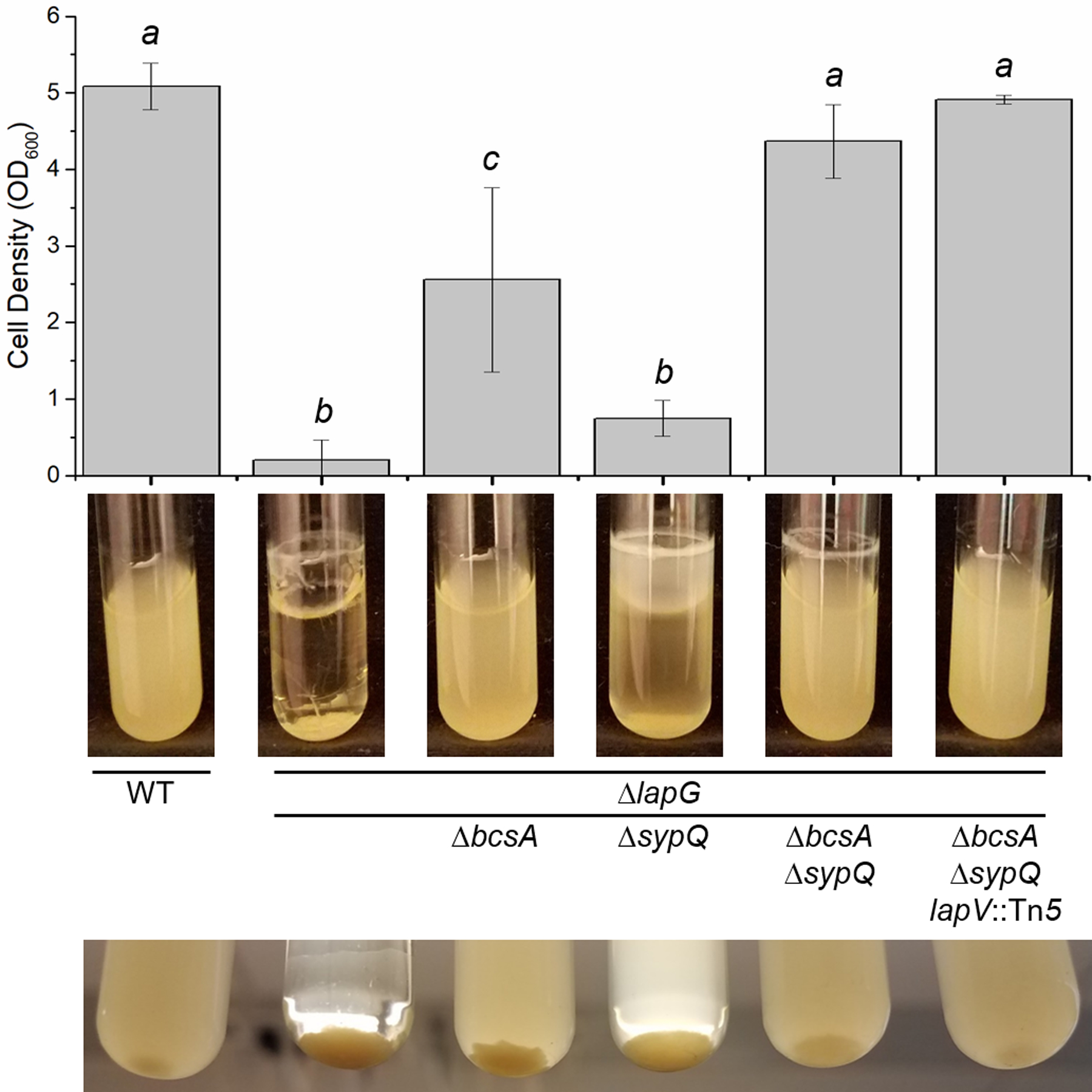

ΔlapG shaking biofilms depend primarily on cellulose.

The ability of a ΔlapG mutant to form calcium-induced rings and clumps was somewhat surprising, as this type of biofilm had been exclusively observed with strains that were engineered to increase production of the major polysaccharides Syp and cellulose, which contribute to biofilm clumps and rings, respectively (Tischler et al., 2018). To determine whether the rings and clumps formed by the ΔlapG mutant depend on these polysaccharides, we introduced mutations that disrupt production of Syp (ΔsypQ (Shibata et al., 2012)), cellulose (ΔbcsA (Bassis and Visick, 2010)), or both polysaccharides (ΔsypQ ΔbcsA) into a ΔlapG strain and evaluated biofilm formation in the resulting strains. Deletion of sypQ visibly increased culture turbidity but did not visibly decrease cell clumping (Fig. 3). Also, the ring formed after deletion of sypQ was phenotypically distinct, producing a smear along the tube side. However, quantification of turbidity indicated that Syp does not significantly contribute to ΔlapG biofilm formation as it does in other biofilm-competent strain backgrounds like ΔbinK (Tischler et al., 2018). In other biofilm-competent strains, cellulose is largely responsible for ring formation (Tischler et al., 2018). Correspondingly, deletion of bcsA reduced ring formation by the ΔlapG mutant (Fig. 3). Additionally, loss of bcsA reduced clump formation, indicating an involvement of cellulose in both phenotypes. Finally, deletion of both sypQ and bcsA largely restored turbidity of the ΔlapG mutant; however, a defined ring and small clump remained (Fig. 3). The mutations were not detrimental to growth as each strain grew to an approximately equivalent final optical density in the absence of calcium (Fig. S3). Together, these findings suggest that LapG inhibits wild-type cells from forming biofilms that are primarily cellulose-dependent. Furthermore, the results also suggest that LapG controls a Syp- and cellulose-independent mechanism of biofilm formation, as some biofilm is still formed in the absence of these polysaccharides.

Figure 3. The ΔlapG mutant biofilm depends on the biofilm components cellulose, Syp polysaccharide, and LapV.

Wild-type (WT) ES114 and mutant derivatives (KV8593, KV8751, KV8754, KV8774, and KV8825) were grown with shaking in LBS containing 10 mM CaCl2 for 24 hours at 24°C. Representative images of each culture and clump are shown. The bar graph depicts the mean optical density of the culture supernatant for three independent replicates. Mean optical densities were compared using a one-way ANOVA. a compared to b (p < 0.05), a compared to c (p < 0.05) and b compared to c (p < 0.05) were statistically different.

The importance of cellulose and, to a lesser extent, Syp in the ΔlapG mutant phenotype led us to wonder whether the loss of lapG resulted in increased expression of the syp or bcs loci. Though LapG is predicted to be a protease, increased polysaccharide production by genetic manipulation is the only method that, to date, promotes robust biofilm formation in otherwise wild-type V. fischeri under laboratory conditions (Brooks and Mandel, 2016, Tischler et al., 2018, Morris et al., 2011, Sabrina Pankey et al., 2017). To determine whether the ΔlapG mutant exhibits increased syp or bcs expression compared to wild-type V. fischeri, we measured the activity of lacZ reporters driven by syp or bcs loci promoters (PsypA and PbcsQ, respectively) in strains with or without LapG. To overcome issues with normalization due to biofilm formation by the ΔlapG mutants, the strains were engineered to eliminate cellulose (ΔbcsA) and Syp (ΔsypQ) production and were grown in baffled flasks to further break apart cellular clumps that may be formed. Unexpectedly, the ΔlapG mutant had reduced activity from both PbcsQ and PsypA (Fig. 4). We observed a similar result when the cells were grown in test tubes, albeit with lower overall values (Fig. 4). While the cause of decreased polysaccharide loci transcription is unknown, these data confirm that the loss of LapG does not induce biofilm formation by increasing transcription of syp or bcs. Instead, based on our understanding of LapG homologs, we hypothesized that LapG negatively affects a protein component of V. fischeri biofilms, specifically a surface-localized adhesin. When LapG is absent, this adhesin may be sufficient to nucleate biofilm formation along with the polysaccharides produced when calcium is present.

Figure 4. The ΔlapG mutation does not enhance transcription of genes that direct production of known biofilm polysaccharides Syp and cellulose.

ΔsypQ bcsA (−) and ΔsypQ bcsA lapG (ΔlapG) mutants carrying lacZ fused to either the bcsQ promoter (KV9401 and KV9403) or sypA promoter (KV9402 and KV9404) at the Tn7 attachment site were grown with shaking in LBS containing 10 mM CaCl2 for 24 hours at 24°C. The cultures were grown in either 20 ml medium in 125 ml baffled flasks (Flask) or in 2 ml medium in a 13 × 100-mm glass test tube (Tube). After 24 hours, a β-galactosidase assay was performed for either the bcsQ promoter (left) or sypA promoter (right). The bar graph depicts the mean β-galactosidase activity for each strain from six independent replicates. Mean activities were compared between ΔsypQ bcsA lapG and the parent using Student’s t-test where (*) indicates p <0.05.

LapI does not contribute to calcium-dependent clumps and rings.

In P. fluorescens, LapG promotes biofilm dispersal by cleaving the large adhesin LapA (~520 kDa), releasing the protein from the cell surface (Boyd et al., 2014). While many bacterial species use large repeats-in-toxin (RTX) adhesins to form biofilms, members of this protein family share low levels of sequence similarity, but can have common motifs, including the eponymous RTX sequences, an amino-terminal LapG cleavage sequence, or a sequence marking the protein for secretion via the T1SS (Boyd et al., 2014). Based on protein size (~410 kDa, 3933 amino acids) and on the presence of a putative LapG cleavage sequence, we hypothesized that lapI encodes a potential surface adhesin (Fig. 1C). Like the adhesins in P. fluorescens and P. putida, LapI is encoded in the lap locus near lapG in V. fischeri (Fig. 1B) (Gjermansen et al., 2010, Newell et al., 2011). To test the role of LapI in biofilm formation, we generated two lapI alleles, a truncated allele that lacks the first 1000 base pairs, including the start codon (lapItrunc), and a ΔlapI deletion that lacks the entire ~12 kb gene. In contrast to our expectations, however, introducing either allele into a ΔlapG mutant failed to alter the calcium-dependent biofilm phenotypes (Fig. 5A). These findings suggest the existence of an alternate adhesin required for biofilm formation and dispersal.

Figure 5. ΔlapG and ΔbinK mutant biofilms require LapV.

(A) Wild-type (WT) ES114 and mutant derivatives (KV8593, KV8826, KV8765, KV8650, KV8649, and KV8829) were grown with shaking in LBS containing 10 mM CaCl2 for 24 hours at 24°C. Representative images of each culture are shown, and the bar graph depicts the mean optical density of the culture supernatant for three independent replicates. Mean optical densities were compared using a one-way ANOVA. Post-hoc analysis shows a compared to b (p < 0.05) was significantly different. (B) WT and mutant derivatives (KV7860 and KV8708) were grown as above. Representative images of each culture are shown, and the bar graph depicts the mean optical density of the culture supernatant for three independent replicates. Comparisons are indicated by a solid bar, and an asterisk (*) indicates one-way ANOVA comparisons with p < 0.05.

LapV promotes V. fischeri biofilm formation.

The V. fischeri genome includes a second putative large adhesin gene on chromosome I, the larger of its two chromosomes. Specifically, VF_1506 encodes a ~420 kDa protein (3971 amino acids) that is composed of 32 VCBS repeats (PF13517) of approximately 100 amino acids each (Fig. 1D). Although poorly characterized, VCBS repeats are found in high copy numbers in large proteins from Vibrio, Colwellia, Bradyrhizobium, and Shewanella genera that are thought to be involved in adhesion (Martínez-Gil et al., 2010, Fong and Yildiz, 2015). Based on the predicted protein size, the presence of VCBS repeats, and phenotypes of the corresponding mutant described below, we named the protein encoded by VF_1506 as LapV (large adhesive protein with VCBS repeats). We initially identified lapV as a gene encoding a putative adhesin through a transposon mutagenesis screen for genes required for biofilm formation by the ΔbinK mutant (Lie and Visick, unpublished). We confirmed this result by generating a lapV truncation allele that lacks the first 1,500 base pairs including the start codon (lapVtrunc) and introducing it into the ΔbinK mutant allele. The loss of LapV substantially diminished the biofilm phenotype of the ΔbinK mutant (Fig. 5B). Consistent with a role for LapV in LapG-dependent biofilm formation, introduction of the lapV::Tn mutation or the lapVtrunc allele into a ΔlapG strain disrupted calcium-induced clump and ring formation (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, introduction of the lapVtrunc allele into the ΔlapG sypQ bcsA background fully abolished the remaining biofilm formation from the parent strain and restored turbidity of the culture to wild-type levels (Fig. 3). Together, these data reveal a critical role for LapV in biofilm formation in the context of both ΔbinK and ΔlapG mutant backgrounds.

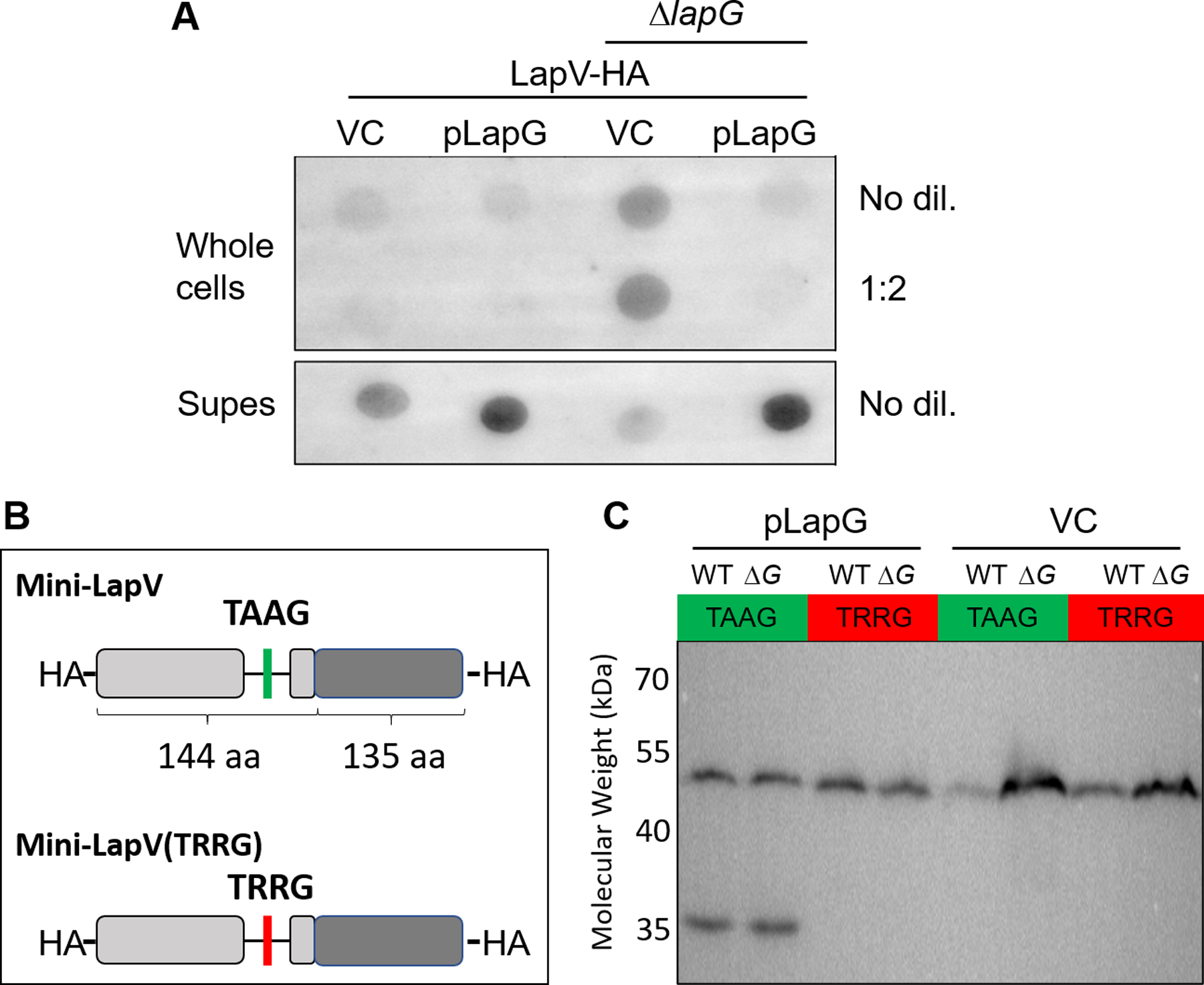

LapG regulates the release of LapV from the cell surface.

To determine whether LapV localizes to the cell surface, we performed a dot blot of whole cells encoding LapV with a C-terminal HA-tag. While the HA tag did not impair LapV function (Fig. S4), our analysis was impeded because the ΔlapG mutant clumps were difficult to normalize, and further complicated by non-specific binding observed in biofilm conditions (Fig. S5). We found that disruption of either lapV or both sypQ and bcsA reduced the background signal. Therefore, to detect LapV and facilitate normalization, we performed the dot blots using a ΔsypQ bcsA strain. We found that LapV-HA was detected at a higher dilution in the absence of LapG relative to the LapG-expressing control (Fig. 6A, compare lane 3 to lane 1), which produced a signal comparable to untagged cells (Fig. S6). Overproducing LapG had no effect on signal in the ΔsypQ bcsA mutant, which remained at the limit of detection (Fig. 6A, lane 2), but it restored ΔsypQ bcsA lapG signal to the limit of detection (Fig. 6A, lane 4). These data suggest that LapG prevents surface localization of LapV.

Figure 6. LapV localizes to the outer membrane and is released into extracellular space by LapG-dependent cleavage at a conserved TAAG motif.

(A) Indicated strains (KV9391 and KV9392) encoding an HA-tag on LapV carrying either pVSV105 (vector control [VC]) or pAEM2 (pLapG) were grown with shaking at 24°C for 24 hours in LBS containing 10 mM CaCl2 and 1 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol. For whole cell spots, a volume of culture was harvested equivalent to 1 OD600. The cells were resuspended in 150 μl PBS, serially diluted, and 3 μl of each dilution was spotted on a PVDF membrane. Only the no dilution and 1:2 dilution are shown. For supernatant spots (Supes), a volume of culture was harvested equivalent to 3.5 OD600 and then total volume was normalized. The cultures were centrifuged at 13,500 rpm for 2’, and supernatants were removed from the cell pellet. 6 μl of each supernatant was spotted on a PVDF membrane. Each blot was probed with an anti-HA antibody conjugated to Surelight™ APC fluorophore. (B) Diagram of Mini-LapV and Mini-LapV(TRRG) constructs. Each construct contains the 144 N-terminal and 135 C-terminal amino acids of full-length LapV with an HA-tag encoded at both termini. DNA encoding each of these constructs was inserted in the intergenic region between yeiR and glmS under the control of the constitutive PnrdR promoter. (C) Anti-HA western blot of whole cell lysates from wild-type (WT) strain ES114 and a ΔlapG mutant derivative (ΔG) that encode either Mini-LapV(TAAG) or Mini-LapV(TRRG) and that carry either pLapG (pAEM2) or vector control (pVSV105). Each strain was grown with shaking at 24°C for 24 hours in LBS containing 10 mM CaCl2 and 1 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol. The expected molecular weight of Mini-LapV and Mini-LapV(TRRG) is ~32 kDa.

Since LapG reduced detectable LapV on the cell surface, we predicted that LapG might cleave and release LapV from the cell, as observed in homologous systems. Therefore, we performed dot blots of cell-free supernatants to detect HA-tagged LapV. Unlike whole cells, supernatant from untagged strains showed no non-specific staining (Fig. S6). A strong signal could be detected from ΔsypQ bcsA supernatants, while ΔsypQ bcsA lapG produced a relatively weaker signal (Fig. 6A, compare lanes 1 and 3). Overproducing LapG in either strain resulted in greatly enhanced staining (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 4). These data are consistent with a model in which LapG regulates the removal of LapV from the cell surface.

LapG promotes dispersal by cleaving LapV.

Because our data indicated that LapG acts through LapV to promote dispersal, we next assessed whether LapG cleaves LapV. Sequence analysis indicated that LapV contains the conserved TAAG cleavage site determined for LapG-dependent cleavage of LapA in P. fluorescens (Boyd et al., 2014, Smith et al., 2018a). To determine whether LapG cleaves LapV at the TAAG motif, we constructed a minimal version of lapV called Mini-LapV that retains the predicted TAAG cleavage site of the native protein and contains HA-tags at both the N- and C-termini (Fig. 6B). We also generated Mini-LapV(TRRG), a variant of Mini-LapV where the dialanine of the predicted cleavage site is replaced by arginines, which has been shown to render LapA insensitive to LapG-dependent cleavage in the homologous system of P. fluorescens (Newell et al., 2011). Introduction of these Mini-LapV constructs did not affect normal function of LapV (Fig. S7).

We successfully detected bands for both Mini-LapV and Mini-LapV(TRRG) expressed in otherwise wild-type cells, though the band corresponding to each construct migrated at an aberrant apparent molecular weight. Attempts to remedy this size discrepancy were unsuccessful, including 1) increasing β-mercaptoethanol concentration to completely reduce disulfide bonds (Fig. S8), 2) deleting potential interacting partners (Fig. S8), and 3) expressing Mini-LapV in a heterologous E. coli system to overcome any potential post-translational modifications that could occur in V. fischeri (Fig. S9). Because none of these possible solutions resolved the size discrepancy, we concluded that the aberrant migration pattern may be an inherent property of this construct and thus proceeded to use it for the studies to assess LapG-dependent cleavage of LapV.

Unexpectedly, no Mini-LapV cleavage products could be observed in wild-type cells, which phenocopied the ΔlapG mutant (Fig. 6C). Importantly, however, overexpressing LapG from a plasmid in both wild-type cells and ΔlapG mutants containing Mini-LapV resulted in the consistent production of a second, lower molecular weight band. A second cleavage product was undetectable; potentially, this product may be unstable. Finally, when LapG was overexpressed in strains carrying Mini-LapV(TRRG), no cleavage product was detected. These data suggest that cleavage of LapV depends on the LapG-dependent recognition of a TAAG motif.

LapC is required to deposit LapV onto the cell surface.

For LapV to extend from the outer membrane on the cell surface, it must travel from the cytoplasm through the inner membrane and periplasm. In P. fluorescens, a type-I secretion system, composed of LapB, LapC, and LapE, mediates this translocation (Hinsa et al., 2003). Structural analysis of these proteins strongly predicts that the functions of LapB, LapC, and LapE are an inner membrane ATPase, a membrane fusion protein, and an outer membrane porin, respectively (Smith et al., 2018b). In V. fischeri, the homologs of these proteins are encoded in the locus containing lapG and lapD (Fig. 1B). If these proteins assist in translocation of LapV, deletion of any one of these type I secretion system genes from a ΔlapG mutant should prevent deposition of LapV onto the cell surface and abolish biofilm formation by the ΔlapG mutant. Thus, we made a ΔlapG-lapC double mutant. As predicted, while a ΔlapG mutant culture has characteristic clumps and rings, the ΔlapG-lapC mutant culture was turbid (Fig. S10). Complementation with lapC restored the biofilm phenotypes to the ΔlapG-lapC mutant, thus demonstrating the importance of LapC in the lapG mutant biofilm phenotype.

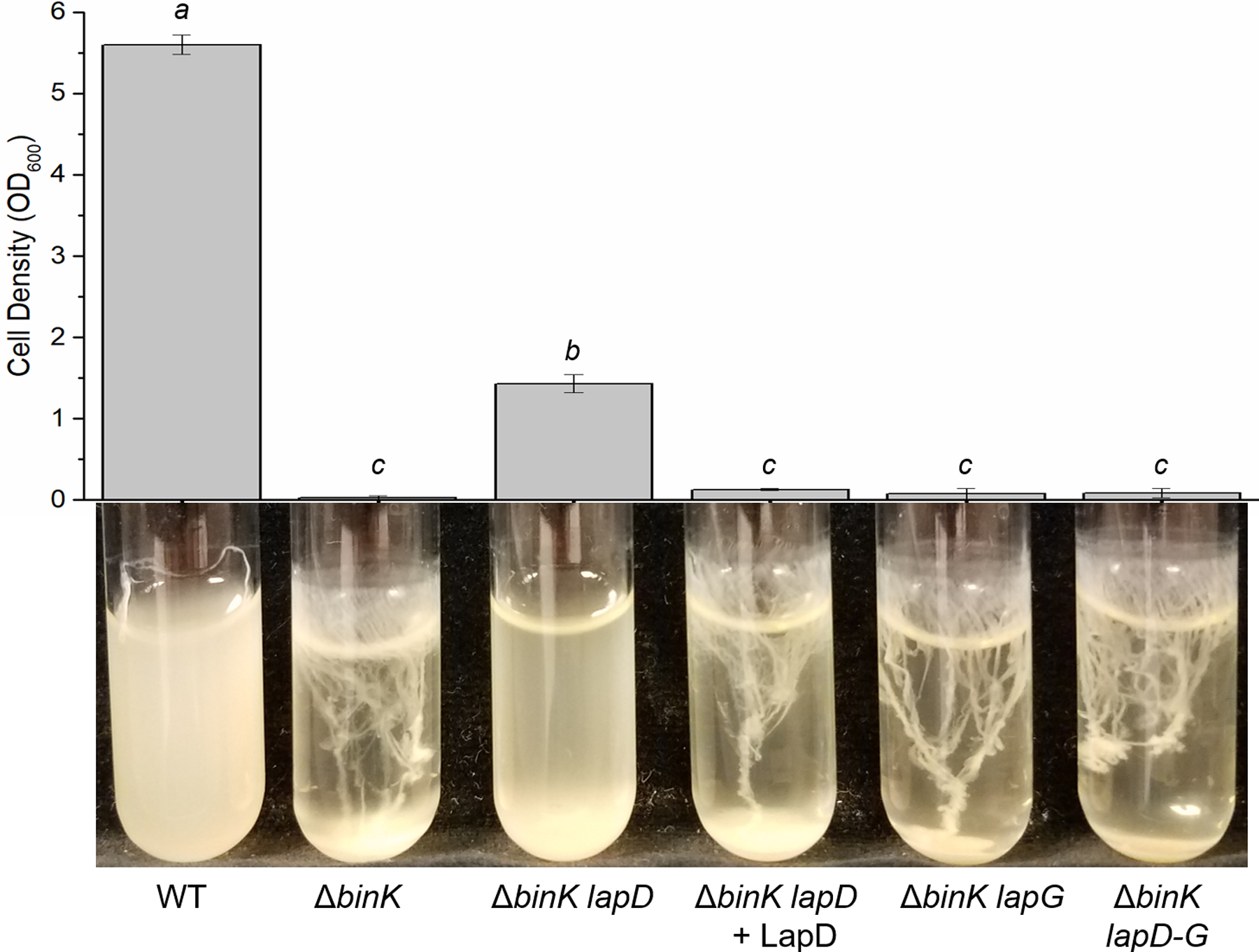

LapD inhibits biofilm dispersal.

In multiple bacteria, LapG-dependent cleavage of its target adhesin is controlled by the transmembrane protein LapD, which binds and sequesters LapG (Fig. 1A) (Newell et al., 2009, Kitts et al., 2019, Rybtke et al., 2015, Ambrosis et al., 2016, Zhou et al., 2015). To determine whether LapD could similarly control LapG activity in V. fischeri, we assessed biofilm phenotypes using a series of ΔlapD mutant derivatives. Because wild-type ES114 cultures are naturally “dispersed”, we evaluated LapD activity in the context of a biofilm-induced strain. Specifically, we used a ΔbinK mutant, which produces biofilms that can be dispersed by LapG (Fig. 2A). Whereas the ΔbinK mutant formed biofilms in response to calcium, the ΔbinK lapD mutant culture was significantly more turbid with some biofilm formation (Fig. 7). Complementing the ΔbinK lapD mutant with lapD at a neutral site in the chromosome abolished turbidity. These results suggest that LapD contributes to biofilm formation, potentially because it controls LapG activity. Consistent with that hypothesis, deleting both lapG and lapD from a ΔbinK mutant resulted in the production of substantial biofilm similar to the ΔbinK parent. This result indicates that the phenotype of a lapG mutation is epistatic to that of the lapD mutation, consistent with the role of LapD as an inhibitor of LapG-dependent dispersal.

Figure 7. LapD inhibits dispersal of binK-dependent biofilms and is hypostatic to LapG.

Wild-type (WT) ES114 and mutant derivatives (KV7860, KV8595, KV9395, KV8633, and KV8832) were grown in LBS supplemented with 10 mM CaCl2 for 24 hours at 24°C. Representative images of each culture are shown, and the bar graph depicts the mean optical density of the culture supernatant for three independent replicates. Mean optical densities were compared using a one-way ANOVA. a compared to b (p < 0.05), a compared to c (p < 0.05) and b compared to c (p < 0.05) were statistically different.

The phosphodiesterase PdeV drives V. fischeri dispersal.

High levels of the second messenger c-di-GMP promote biofilm formation in many bacteria (Hisert et al., 2005, Römling et al., 2005, Kulasakara et al., 2006, Chua et al., 2014, Yu et al., 2015). LapD is predicted to contain catalytically inactive phosphodiesterase and diguanylate cyclase domains, which often serve as c-di-GMP binding domains (Fig. S2). In P. fluorescens, binding of c-di-GMP to LapD results in activation of its sequestration activity (Navarro et al., 2011). There are 50 V. fischeri genes predicted to encode phosphodiesterases (PDEs) that break down c-di-GMP, diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) that make c-di-GMP, enzymes that contain both putative activities, or enzymes that contain one or more degenerate GGDEF and/or EAL domains (Wolfe and Visick, 2010). If c-di-GMP activates LapD to sequester and inhibit LapG-dependent dispersal, deletion of one or more PDEs should increase c-di-GMP levels to promote biofilm formation. In an on-going study designed to mutate and phenotypically assess putative DGC and PDE genes, we found that deletion of a putative PDE, encoded by VF_A1014, was sufficient to promote shaking biofilm phenotypes comparable to that of a ΔlapG mutant (Fig. 8A). Complementation confirmed that this mutation was responsible for the observed biofilm phenotype (Fig. 8B). Due to this phenotype and subsequent characterization of VF_A1014 described below, we designate this gene as pdeV (phosphodiesterase for VCBS adhesin-dependent biofilm).

Figure 8. The phosphodiesterase PdeV inhibits LapV-dependent biofilm formation.

(A) The ΔpdeV mutant (KV8969) and mutant derivatives were grown with shaking in LBS supplemented with 10 mM CaCl2 for 24 hours at 24°C. Representative images of each culture are shown, and the bar graph depicts the mean optical density of the culture supernatant for three independent replicates. Mean optical densities were compared using a one-way ANOVA. a compared to b (p < 0.05), a compared to c (p < 0.05) and b compared to c (p < 0.05) were statistically different. (B) The ΔpdeV mutant carrying vector control (VC [pVSV105]) or plasmid expressing pdeV (PdeV [pMJR4]) was grown with shaking in LBS supplemented with 10 mM CaCl2 and 1 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol for 24 hours at 24°C. Mean optical densities were compared using Student’s t-test with (*) indicating p<0.05.

To determine whether the ΔpdeV biofilm depended on the Lap system or the known biofilm polysaccharides, we made double mutants and assessed the biofilms formed under shaking conditions (Fig. 8A). In contrast to the single ΔpdeV parent, the double ΔpdeV bcsA exhibited substantial turbidity, similar to what is observed for a ΔlapG bcs double mutant, indicating the relative importance of cellulose in this phenotype (Fig. 3). In contrast, deletion of sypQ had no effect on turbidity but did result in a robust, defined ring, suggesting a more modest role for Syp in this phenotype. Importantly, deletion of lapV restored full turbidity to the culture, approximating that of the wild-type strain (e.g., Fig. 3). These data demonstrate that ΔlapV is epistatic to ΔpdeV, and suggest that PdeV inhibits LapV-dependent biofilm formation by ES114. Finally, deletion of lapD similarly resulted in fully turbid cultures that could be complemented by a wild-type copy of lapD, suggesting that PdeV activity requires the function of LapD. Together, these data are consistent with a role for PdeV in promoting dispersal dependent on LapD, possibly by degrading c-di-GMP necessary to activate LapD to sequester LapG and prevent cleavage of LapV (Fig. 1A).

The Lap system regulates pellicle formation.

To determine whether the Lap system has a role in other V. fischeri biofilm phenotypes, we evaluated pellicle production, a well-studied biofilm phenotype that is correlated with the ability of V. fischeri to establish a symbiosis with its squid host. The lap genes made a major contribution to pellicle production, primarily by impacting pellicle architecture and/or retention of cells in the pellicle (Fig. 9). Upon static growth in culture for 72 h, wild-type strain ES114 reproducibly formed a modest, but highly sticky pellicle. This phenotype has not been reported previously, likely because calcium supplementation was not included in most past experiments (Koehler et al., 2018). These data underscore the importance of calcium in inducing biofilm formation by V. fischeri (Tischler et al., 2018) and reveal conditions in which ES114 forms modestly sticky biofilms without genetic manipulation. Furthermore, within 24 h, the ΔlapG mutant produced a single, striking wrinkle in the middle of a pellicle, which subsequently collapsed. These data suggest that LapG plays a role in preventing the production of strong biofilms.

Figure 9. The Lap system regulates pellicle architecture.

Wild-type strain ES114 (WT) or mutant derivatives (KV8735, KV7860, KV8633, KV8595, KV8832, and KV8598) were inoculated to 0.02 OD600 into LBS containing 10 mM CaCl2 in a 24 well plate. The plates were incubated statically at 24°C in a re-sealable plastic bag for 72 hours upon which time they were disrupted with a toothpick to assess biofilm robustness.

We next examined pellicles produced in the absence of the negative regulator BinK. The single ΔbinK mutant produced a robust pellicle with evenly distributed, fine wrinkling that was enhanced in the absence of lapG. Deletion of lapD or lapV greatly diminished the wrinkling of the pellicle. The ΔbinK mutant lacking lapD and lapG phenocopied the lapG mutant, as observed previously for biofilms formed under shaking conditions (Fig. 7). These data are consistent with the model shown in Fig. 1.

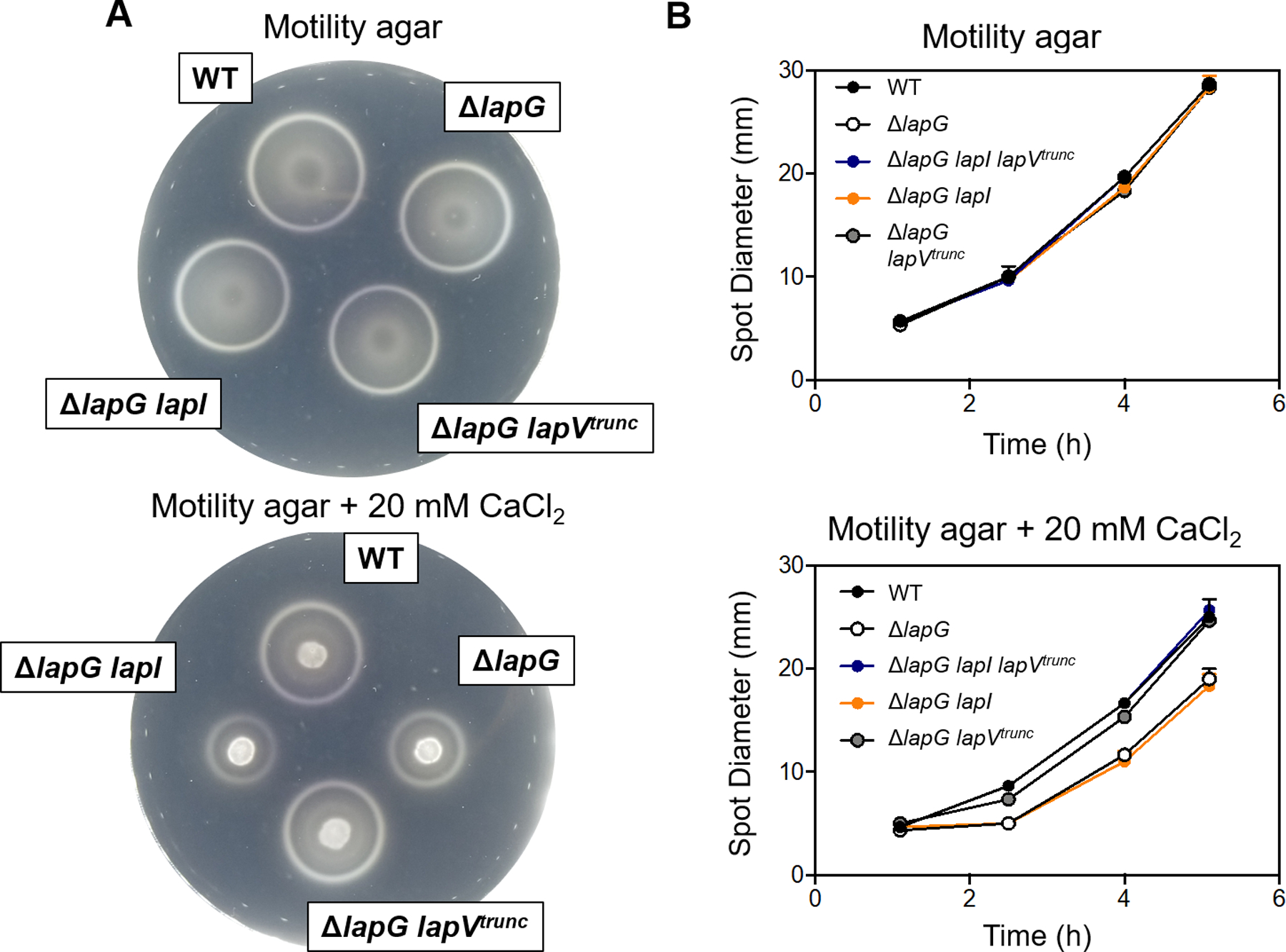

Adhesins reduce motility in a ΔlapG mutant.

Our data support a model in which adhesins are present on the cell surface in a ΔlapG strain when calcium is present. Due to the immense sizes of LapI and LapV, we wondered whether one or both adhesins could affect motility, one of the main behaviors associated with V. fischeri during animal colonization (Aschtgen et al., 2019, Graf et al., 1994). To compare motility between strains, we measured the zone of migration over time on motility agar with and without calcium and incubated the plates at a temperature conducive to biofilm formation and adhesin production. Compared to wild type, ΔlapG motility was reduced only when calcium was present (Fig. 10). We found that neither calcium-induced polysaccharide production (Tischler et al., 2018) nor LapI mediated this motility defect as both ΔlapG sypQ bcsA (Fig. S11) and ΔlapG lapI (Fig. 10) migrated at a rate comparable to that of ΔlapG alone. In contrast, eliminating LapV adhesin production restored motility to the ΔlapG mutant. Importantly, in the absence of calcium, the migration of each tested strain was indistinguishable from the wild-type strain (Fig. 10). Together, these data support a model in which LapG activity controls presence of the LapV adhesin on the cell surface to mediate biofilm formation, resulting in a hindrance of motility, perhaps by directly interfering with the flagella, indirectly introducing drag, and/or interacting with the agar polysaccharides.

Figure 10. LapV decreases migration of a ΔlapG mutant.

A 10 uL aliquot of wild-type (WT) ES114 or mutant derivatives (KV8593, KV8829, KV8826, and KV8649) normalized to 0.02 OD600 was spotted onto motility agar plates with 20 mM CaCl2 or without addition. Plates were incubated at 24°C and motility was monitored over time. (A) Representative plate picture after 4 hours of incubation at 24°C. (B) Motility over time graph where individual data points represent the mean of technical replicates (same sub-culture spotted onto 3 separate plates).

LapD influences symbiotic colonization.

Symbiotic colonization by V. fischeri depends on both syp-dependent biofilm formation on the light organ surface and subsequent dispersal into the interior crypts where the bacteria ultimately reside. If the Lap system is involved in regulating biofilm formation and dispersal in vivo, dysregulating Lap-dependent dispersal may alter colonization of the light organ.

Because a ΔlapD mutant exhibits diminished biofilm formation (Fig. 7), we asked whether this constitutively dispersing mutant would exhibit a colonization defect. We thus assessed the importance of LapD using three assays: single strain inoculations, competitions with wild-type, and direct visualization of ΔlapD colonization of crypts during competitive colonization. In single strain inoculations with the same strain carrying either an RFP-expressing plasmid or a GFP-expressing plasmid, wild type-inoculated animals were colonized 100% of the time (1-d post-inoculation), as measured indirectly using luminescence as a marker of colonization. In contrast, the ΔlapD mutant failed to colonize one third of the animals, indicating that this mutation may cause a delay in initiating colonization (Fig. 11A). We next assessed whether the ΔlapD mutant would exhibit a defect in colonization when competed against wild type. To do so, we competed a ΔlapD mutant carrying the RFP-expressing plasmid and wild type carrying the GFP-expressing plasmid and vice versa. No defect was observed as the ΔlapD mutant was competent to colonize in approximately equal numbers relative to the wild-type strain (Fig. 11B).

Figure 11. ΔlapD mutants exhibit a mild colonization defect in the absence of wild type.

A) The indicated combination of wild type (WT) and ΔlapD (KV8582) labeled with different plasmids (pVSV102 with GFP and pVSV208 with RFP) were mixed and introduced to juvenile squid at comparable inoculum levels: WT (1.6–2.09 × 104) and lapD (9.8 × 103 – 1.87 × 104). A luminometer reading of above 10 relative light units (RLU) is operationally defined as colonized. Between two experiments, a third of animals were colonized at 24 hours when only the ΔlapD mutant was in the water (N = 30). B) From either competition between WT and ΔlapD, the squid were homogenized and plated for CFU. These data are plotted as the log of a relative competitive index as defined by RCI=(CFUmutant/CFUWT)output/(CFUmutant/CFUWT)input. C) Confocal micrographs of light organ crypts, colonized with fluorescently labeled wild-type and lapD mutant strains. Host cell nuclei are stained with TOPRO-3, shown in blue. Bars 20 μm, unless otherwise indicated.

Finally, our imaging experiments revealed rare, but unusual, defects of the ΔlapD mutant: in animals exposed only to the ΔlapD mutant, occasionally the largest, most mature tissue crypt 1 (C1) was not colonized (2 out of 7 cases). In mixed inoculation experiments between wild type and ΔlapD, in 4 out of 18 C1 analyzed, wild-type and ΔlapD cells were either swirled together (Fig. 11C, top) or had large pockets of empty space between cells lining the host epithelium (Fig. 11C, bottom). Often, the less mature crypt 2 (C2) and crypt 3 (C3) spaces (32 out of 34 C2/C3 analyzed) were single colonized by either the wild type or ΔlapD strain. However, in the other 2 instances when the two strains co-colonized C2/C3, they were distributed evenly in the crypt lumen (Fig. 11C, bottom). The appearance of co-colonized strains when present in the less mature crypts was indistinguishable from the ‘normal’ distribution of wild type (two ES114 strains with each reporter) when mixed in any crypt (Fig. S12). Taken together, these data suggest that 1) the ΔlapD mutant is defective for initiating colonization when presented alone, 2) the ΔlapD mutant is not dramatically outcompeted by wild type when both are present, suggesting that other factors compensate for the lack of LapD, and 3) there may be other phenotypic consequences of the absence of LapD during symbiotic colonization that warrant further examination.

DISCUSSION

Initiating the symbiosis between V. fischeri and its squid host requires two shifts in bacterial lifestyle: from planktonic single cells in seawater to a multi-cellular biofilm community on the surface of the squid’s light organ, then a shift back to the planktonic form, permitting migration into the light organ where colonization occurs. While biofilm formation has been intensively studied, dispersal has remained elusive. Here, we identify both the protease LapG and the PDE PdeV as dispersal factors in V. fischeri, based on their inhibitory roles in shaking biofilms. We further identify LapV as a surface adhesin whose cleavage by LapG promotes dispersal.

The V. fischeri genome encodes homologs of the Lap system that regulates biofilm formation and dispersal in P. fluorescens and other bacteria, and our data reported here are consistent with the model previously established (Fig. 1). Somewhat surprisingly, however, we found that the biofilm formation that occurs in the absence of LapG depends not on LapI, which is encoded within the lap locus on niche-specific chromosome II, but on LapV, encoded by a gene located on the larger chromosome I. LapI and LapV are both predicted to be members of the repeats-in-toxin (RTX) family of exoproteins present in certain Gram-negative bacteria that consist of both toxins as well as adhesins (Linhartová et al., 2010). While this protein family is diverse in size and function, each member is characterized by TISS-dependent secretion and the presence of an RTX motif required for secretion. Both LapI and LapV contain an RTX motif at their respective C-termini as well as multiple repeat domains implicated in adhesion.

Other motifs within the two proteins are distinct. LapV contains 32 VCBS domains that overlap with 14 cadherin-like domains, a similar architecture to what is seen for the RTX protein BrtA, which is required for biofilm formation in B. bronchiseptica (Nishikawa et al., 2016). In contrast, LapI contains 15 Immunoglobulin-like domains, 7 cadherin domains, and a von Willebrand factor type A (vWFA) domain. Other large adhesins implicated in biofilm formation contain similar motifs (P. putida LapF contains Ig-like repeats while P. putida LapA, P. fluorescens LapA, and B. bronchiseptica BrtA each contain a vWFA domain (Nishikawa et al., 2016)), making it reasonable to expect that LapI could contribute to biofilm formation in V. fischeri. However, we were unable to observe any phenotype for LapI; perhaps it is not expressed or is nonfunctional under the conditions used here. In V. cholerae O1 El Tor, which similarly encodes two large adhesins, FrhA and CraA, both adhesins were required for robust biofilm formation on a natural substrate, chitin, but not glass. Alternatively, LapI function may be revealed by the use of a different strain. In V. cholerae O1 El Tor, neither adhesin contributed substantially to hemagglutination, while in the O1 classical O395 strain, both FrhA and CraA contributed to biofilm formation on glass yet only FrhA contributed to hemagglutination (Kitts et al., 2019).

In P. aeruginosa, the large adhesin CdrA directly binds the biofilm matrix polysaccharide Psl to strengthen the biofilm (Borlee et al., 2010). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that LapV could bind to one or more Vibrio polysaccharides to crosslink the cells within the biofilm matrix. However, CdrA can promote biofilm formation in the absence of EPS (Psl, Pel, and alginate), and thus likely binds to other substrates as well (Reichhardt et al., 2018). Since LapV causes a ring and clump to form in the absence of Syp and cellulose (Fig. 3, compare tubes 5 and 6), albeit substantially reduced, it appears that LapV may be able to bind a non-Syp, non-cellulose substrate.

Calcium positively stimulates biofilm formation of V. fischeri. Addition of CaCl2 induces biofilm formation by a ΔbinK mutant (Tischler et al., 2018), and here the same is found for a ΔlapG mutant: calcium promotes clump and ring formation (Fig. 2B) that depends on LapV (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that wild-type ES114 synthesizes biofilm-promoting LapV in the presence of calcium, but LapG is actively cleaving it to promote dispersal. LapG function may thus explain, in part, why wild-type ES114 does not form robust biofilms under any known laboratory conditions. These calcium-dependent biofilms formed by the ΔlapG mutant also depend partially on Syp and more strongly on cellulose (Fig. 3), indicating that wild-type cells are actively producing these polysaccharides in the presence of calcium. However, the quantity of polysaccharide produced by wild type appears to be insufficient to promote substantial biofilm formation, potentially due to LapG activity and/or to other unknown dispersal mechanisms.

While the interconnectedness of calcium and biofilm formation in V. fischeri is clear, the exact calcium responsive factors are not defined. One result of excess calcium is increased transcription of polysaccharide synthesis loci, which results in increased polysaccharide production (Tischler et al., 2018). In the Lap system, calcium appears to have a dual role that is almost certainly conserved in V. fischeri. The first role is to promote biofilm formation. LapV has multiple calcium binding domains that in related proteins are important for folding and rigidity of the protein. For example, the BapA protein in Salmonella remains in a flexible state at intracellular concentrations of calcium (sub-micromolar), while in the higher, extracellular concentrations of calcium (millimolar), BapA adopts a more rigid conformation (Guttula et al., 2019). Additionally, a calcium-dependent ratcheting mechanism has been proposed to translocate the RTX leukotoxin CyaA of Bordatella pertussis through its cognate T1SS (Bumba et al., 2016). Thus, for LapV to pass from the cytoplasm to the extracellular space, it must remain flexible enough to pass through the TISS, whereupon exiting the LapE pore, it comes into contact with a high calcium concentration that possibly extrudes LapV and allows LapV to adopt a final, rigid form. The second role of calcium is to inhibit biofilm formation. LapG is a calcium-dependent cysteine protease; as such, it has been shown to require calcium to promote its activity (Ambrosis et al., 2016, Boyd et al., 2012, Kitts et al., 2019). These opposing effects of calcium emphasize that other signals beyond calcium are likely required for the decision of V. fischeri to form (or leave) a biofilm.

Attempts to show that LapV localizes to the cell surface and that LapG releases LapV into the supernatant were met with unexpected challenges. Though not described in the results section, our early work revealed that V. fischeri cells reacted with the chemiluminescent substrate, prompting our use of fluorescently-tagged antibodies. We also found that a ΔlapG mutant readily binds antibody, but this binding was alleviated by disruption of either lapV or of both syp and bcs (Fig. S5). Since neither the polysaccharides nor LapV alone is sufficient for the non-specific antibody binding, an association between LapV and the polysaccharides may provide an epitope that the antibody can recognize. Alternatively, the combination of these components may produce an inherent stickiness that can facilitate antibody attachment.

Our experiments with Mini-LapV constructs containing the putative cleavage site, TAAG, or a mutated version, TRRG, supported the model that LapG-dependent cleavage depends on TAAG (Fig. 6C) (Newell et al., 2011). However, neither full-length nor the cleavage product of the TAAG construct migrated to its expected size. We hypothesized that a post-translational modification may have been responsible. There are two cysteines (C75 and C78) near the N-terminus of LapV that are present in Mini-LapV. These may form an intramolecular disulfide bond as a “cysteine hook” that anchors LapV to the cell surface, as has been proposed for the large adhesive protein HMW1 in Haemophilus influenzae (Buscher et al., 2006). However, addition of extra β-mercaptoethanol to samples of Mini-LapV did not alter the size, suggesting that a disulfide bond is likely not responsible for the size discrepancy (Fig. S8). Furthermore, the aberrant migration was also observed when Mini-LapV was produced in E. coli (Fig. S9), indicating that, if a post-translational modification is responsible, it also occurs in an organism without obvious Lap homologs.

As observed in other bacteria, LapD from V. fischeri inhibits biofilm dispersal (Fig. 7). LapD is predicted to contain degenerate EAL and GGDEF domains based on the divergence from the extended PDE motif EXLXR (EVFSA in LapD) and the DGC motif GGDEF (NSSEF in LapD) (Chou and Galperin, 2016). A set of structural studies showed that P. fluorescens binds c-di-GMP through its enzymatically inactive EAL domain, causing the EAL domains of adjacent LapD molecules to form a dimer-of-dimers and exerting conformational changes in the periplasmic domain to sequester LapG (Newell et al., 2009, Cooley et al., 2016, Navarro et al., 2011). In contrast, V. cholerae LapD binds to two molecules of c-di-GMP via both its EAL and GGDEF domains, with binding to the latter domain being required for dimerization to occur (Kitts et al., 2019). V. fischeri LapD is highly similar to the V. cholerae protein and contains a conserved residue in the GGDEF domain shown to be required for this dimerization. Interestingly, three of the four residues required for c-di-GMP binding to the EAL domain of P. fluorescens LapD are not conserved in the two Vibrio species, potentially indicating a divergence in function. However, while additional work is required to understand the exact roles of the EAL and GGDEF domains, the overall conserved domain architecture suggests that LapD likely functions as an inside-out c-di-GMP receptor via its EAL and/or GGDEF domains in Vibrio (Newell et al., 2009).

PdeV is predicted to be a transmembrane protein with a cytosolic EAL domain and a degenerate GGDEF domain that lacks the conserved GGDEF motif; thus, it is expected to function solely as a PDE. Consistent with a role for PdeV in degrading c-di-GMP required for LapD function, deletion of pdeV from otherwise wild type V. fischeri caused the cells to form clumps and rings similar to the ΔlapG mutant and dependent on an intact LapD. Future studies will investigate whether this phenotype is specific to PdeV or if other PDEs can have a similar effect and will also determine which DGC(s) produce the c-di-GMP that LapD binds. Certain DGC and PDE enzymes have been suggested to have localized effects, while others globally alter the cellular concentrations of c-di-GMP (Sarenko et al., 2017). In the homologous system identified in V. cholerae, an increased pool of c-di-GMP promotes biofilm formation by both activating LapD activity and activating transcription of the genes encoding the adhesins FrhA and CraA (Kitts et al., 2019). Whether a similar phenomenon occurs in V. fischeri to control lapV transcription remains to be determined.

While we present LapG as a V. fischeri dispersal factor, it is likely not the only one. Our data indicate that overexpression of LapG does not completely abolish biofilm formation (Fig. 2A), and a biofilm can be formed even in the complete absence of LapV (Fig. 5B). Many dispersal factors, including proteases, nucleases, and glycoside hydrolases, have been identified across multiple bacterial biofilm models (reviewed in (Fleming and Rumbaugh, 2017, Kostakioti et al., 2013, Kaplan, 2010, Guilhen et al., 2017). For example, P. aeruginosa has two known dispersal factors, LapG to cleave the CdrA adhesin and alginate lyase to degrade the polysaccharide alginate (Boyd and Chakrabarty, 1994, Rybtke et al., 2015). Since Syp polysaccharide is required for colonization of the squid host by V. fischeri (Yip et al., 2005), it is likely that V. fischeri encodes one or more hydrolases to degrade this matrix polysaccharide to promote dispersal.

A ΔlapD mutant, which should exhibit a “constitutively dispersing” phenotype, had a modest colonization defect, which indicates relevance for this mechanism in nature (Fig. 11). This defect could be alleviated by co-inoculation with wild-type cells. Perhaps the LapV produced by ES114 can facilitate binding by the ΔlapD mutant on the light organ surface; in the context of such a mixed biofilm, the defect of ΔlapD may no longer be a disadvantage. Indeed, LapV retained by a subset of cooperating cells could act as a public good for establishment of a symbiosis with a genotypically diverse V. fischeri community, some of which may lack the adhesin. In this context, ΔlapD mutants may become “cheaters” that can negatively impact the population (Rainey and Rainey, 2003). Further studies are necessary to understand the functions and evolutionary advantage of LapV and other Lap system components in symbiotic biofilm formation and dispersal.

In conclusion, we have substantially expanded our knowledge of the factors that control the biofilm versus dispersal decision by V. fischeri. We have identified two genes, lapG and pdeV, that actively promote dispersal by wild-type strain ES114, and whose loss results in calcium-induced biofilm formation. We have also added LapV to the list of structural components that are required for full biofilm formation. Together with past results, this work indicates that ES114 encodes multiple regulators that promote the planktonic state under standard laboratory conditions. Elucidating a role for these previously unstudied components enables future studies to identify signals that control the Lap pathway as well as alternative dispersal factors of V. fischeri biofilms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media

All V. fischeri strains used in this study are derivatives of strain ES114 (Boettcher and Ruby, 1990) and are listed in Table 1 and Table S1, the latter of which also contains construction details. Primers used for molecular genetics can be found in Table S2. V. fischeri strains were maintained on LBS agar plates (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 342 mM NaCl, and 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 with 1.5% agar for solid media), and kanamycin (100 μg ml−1) or chloramphenicol (1 μg ml−1) was added as necessary (Graf et al., 1994). For squid experiments, V. fischeri was grown in SWT medium (0.5% tryptone, 0.3% yeast extract, and 0.3% glycerol in 70% filtered ocean water). E. coli strains GT115, π3813, DH5α, and TAM1 λpir carrying plasmids listed in Table S3 were used for conjugation and maintained on LB agar plates (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% NaCl with 1.5% agar) with kanamycin (50 μg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (12.5 μg ml−1) added as necessary. Soft agar motility plates contained tryptone (1%), NaCl (2%), agar (0.25%), MgSO4 (35 mM), and CaCl2 (20 mM) where indicated.

Table 1:

V. fischeri strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype† | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ES114 | Wild type | Boettcher and Ruby, 1990 |

| KV7655 | attTn7::rscS | Tischler et al., 2018 |

| KV7860 | ΔbinK | Tischler et al., 2018 |

| KV8582 | ΔlapD::FRT-EmR | This study |

| KV8593 | ΔlapG | This study |

| KV8595 | ΔbinK ΔlapD::FRT | This study |

| KV8598 | ΔbinK lapVtrunc::FRT | This study |

| KV8617 | IG (yeiR-glmS)::FRT-EmR-PnrdR-HA-mini-lapV-HA | This study |

| KV8633 | ΔlapG ΔbinK::FRT-EmR | This study |

| KV8649 | ΔlapG lapVtrunc::FRT-EmR | This study |

| KV8650 | ΔlapG lapV::Tn5 | This study |

| KV8655 | ΔlapG IG (yeiR-glmS)::FRT-EmR-PnrdR-HA-mini-lapV-HA | This study |

| KV8708 | ΔbinK lapVtrunc::FRT-EmR | This study |

| KV8727 | ΔlapG attTn7::Plac-lapG | This study |

| KV8735 | ΔlapG::FRT-EmR | This study |

| KV8751 | ΔlapG ΔbcsA::FRT-TrimR | This study |

| KV8754 | ΔlapG ΔsypQ::FRT-CmR | This study |

| KV8765 | ΔlapG lapItrunc::FRT-EmR | This study |

| KV8774 | ΔlapG ΔbcsA::FRT-TrimR ΔsypQ::FRT-CmR | This study |

| KV8813 | IG (yeiR-glmS)::FRT-EmR-PnrdR-HA-mini-lapV(TRRG)-HA | This study |

| KV8814 | ΔlapG IG (yeiR-glmS)::FRT-EmR-PnrdR-HA-mini-lapV(TRRG)-HA | This study |

| KV8825 | ΔlapG ΔbcsA::FRT-TrimR ΔsypQ::FRT-CmR lapV::Tn5 | This study |

| KV8826 | ΔlapG ΔlapI::FRT-TrimR | This study |

| KV8829 | ΔlapG lapVtrunc::FRT ΔlapI::FRT-TrimR | This study |

| KV8832 | ΔbinK Δ(lapD-lapG)::FRT-EmR | This study |

| KV8969 | ΔpdeV::FRT | This study |

| KV9391 | ΔsypQ::FRT ΔbcsA::FRT lapV-HA-FRT-EmR | This study |

| KV9392 | ΔsypQ::FRT ΔbcsA::FRT ΔlapG::FRT lapV-HA-FRT-EmR | This study |

| KV9395 | ΔbinK ΔlapD::FRT IG (yeiR-glmS)::FRT-EmR-PnrdR-lapD-HA | This study |

| KV9401 | ΔsypQ::FRT ΔbcsA::FRT attTn7::PbcsQ-lacZ | This study |

| KV9402 | ΔsypQ::FRT ΔbcsA::FRT IG (yeiR-glmS)::PsypA-lacZ attTn7::EmR | This study |

| KV9403 | ΔsypQ::FRT ΔbcsA::FRT ΔlapG::FRT attTn7::PbcsQ-lacZ | This study |

| KV9404 | ΔsypQ::FRT ΔbcsA::FRT ΔlapG::FRT IG (yeiR-glmS)::PsypA-lacZ attTn7::EmR | This study |

| KV9407 | ΔpdeV::FRT ΔbcsA::FRT-TrimR | This study |

| KV9408 | ΔpdeV::FRT ΔlapD::FRT-EmR | This study |

| KV9409 | ΔpdeV::FRT lapVtrunc::FRT-EmR | This study |

| KV9410 | ΔpdeV::FRT ΔsypQ::FRT-CmR | This study |

| KV9414 | ΔpdeV::FRT ΔlapD::FRT IG (yeiR-glmS)::FRT-EmR-PnrdR-lapD-HA | This study |

IG = intergenic region between the genes in parentheses

Strain construction

V. fischeri strains were engineered using natural transformation (Pollack-Berti et al., 2010) in Tris minimal medium and tools as described previously (Visick et al., 2018). Briefly, for each mutant, a precursor strain carrying pLostfoX-Kan was transformed with linear DNA (i.e., chromosomal DNA or PCR product) (Brooks et al., 2014). Mutants were selected on LBS medium containing Erythromycin (Erm) at 5 μg ml−1, Chloramphenicol (Cm) at 1 μg ml−1, or Trimethoprim (Trim) at 5 μg ml−1.

Shaking biofilm assays

V. fischeri were inoculated into LBS medium using either single colonies or frozen cells and grown at 28°C with shaking overnight for ~16–18 hours. Optical densities were measured and were used to inoculate 2 ml LBS with or without 10 mM CaCl2 (indicated in the figure legends) at an OD600 of 0.05. Sub-cultures were shifted to 24°C with shaking. Tubes were imaged after 24 hours or the indicated time point using a Samsung Galaxy S7 or S8 camera. To compare the extent of biofilm formation among strains, we quantified optical density as a proxy to measure the proportion of clumped cells compared to cells in suspension. Representative images are shown from at least 3 independent experiments.

Motility assays

Overnight cultures of V. fischeri grown in LBS at 28°C were sub-cultured (1:100) into fresh LBS medium and grown at 28°C with shaking for one hour. Optical densities were measured, cultures were diluted with LBS to a standard OD600 of 0.2, and a 10 μl aliquot was spotted onto freshly poured motility plates with or without 20 mM calcium. The outer diameter of the zone of migration was measured over time.

Transcriptional reporter assay

From single colonies, V. fischeri strains were grown overnight at 28°C with shaking in LBS. The following day, cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in LBS with 10 mM CaCl2 (as indicated in the figure legends) and grown at 24°C with shaking. Samples were collected after 24 hours and assayed for β-galactosidase activity as previously described (Miller, 1972). Miller units were calculated and reported as the average of at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Student’s t-test.

Dot blot assay

Cultures of V. fischeri were grown overnight at 28°C in LBS with 1 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol when indicated. Optical densities were measured and were used to inoculate 2 ml LBS with 10 mM CaCl2 at an OD600 of 0.05. For dot blots of whole cells, a volume of culture was harvested equivalent to 1 OD600. The harvested cells were pelleted at 13,500 rpm for 2’ and resuspended in 150 μl PBS. The resuspended cells were serially diluted as indicated in the figures, and 3 μl of each dilution was spotted on a PVDF membrane. For dot blots of supernatants, a volume of culture was harvested equivalent to 3.5 OD600 and then total volume was normalized. The cultures were centrifuged at 13,500 rpm for 2’, and supernatants were removed from the cell pellet. 6 μl of each supernatant was spotted on a PVDF membrane. The blots were allowed to dry overnight, rehydrated, and blocked with 10% milk (2 g in 20 mL PBS). The blots were washed with PBST for 5’ in triplicate. The blot was probed with a 1:10 anti-HA IgG:SureLight™ APC (Columbia Biosciences D3–1830) antibody in 10 ml PBST. The blots were washed with PBST for 5’ in triplicate and imaged using the Cy5 filter of a ChemiDoc XRS+ System (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA).

Western blot assay

Cultures of V. fischeri were grown overnight at 28°C in LBS with 1 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol, and cultures of E. coli were grown overnight at 37°C in LB with 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin. Optical densities were measured and used to inoculate 2 ml LBS with chloramphenicol or 2 ml LB with ampicillin each supplemented with 10 mM CaCl2 at an OD600 of 0.05. Cultures of V. fischeri were grown with shaking at 24°C for 24 hours, while E. coli cultures were grown with shaking at 37°C for 24 hours. After 24 hours, an equivalent volume of each culture was harvested to obtain an equivalent of 1 OD600 of cells, unless otherwise noted in a figure. The cells were pelleted at 13,500 rpm for 1’, and the supernatant was decanted. The cell pellets were resuspended in 100 μl 2× loading dye and boiled for 10’. Unless otherwise noted, 10 μl of each lysate was loaded onto a SDS-PAGE gel (8% stacking, 12% resolving). Electrophoresis was carried out at 150 V for approximately 1.5 hours. The proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane for 1.5 hours at 100 V at 4°C. Membranes were blocked with 10% milk (2 g milk in 20 ml PBS) for 1.5 hours and then washed for 5’ with PBST in triplicate.

For detection of HA-tagged proteins, the blots were incubated with an anti-HA primary antibody (H6908, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 10 ml PBST (1:10,000) overnight. The membrane was washed for 5’ with PBST in triplicate, and incubated with an anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody conjugated to HRP (A0545, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 10% milk (1:10,000) made with PBST. After a final triplicate set of 5’ washes with PBST, the blot was incubated with SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and imaged using a FluorChem E imaging system (ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA).

Pellicle assay

Overnight cultures of V. fischeri were grown with shaking at 28°C in LBS. These cultures were inoculated to 0.02 OD600 in 2 ml LBS with 10 mM CaCl2 in the center wells of a 24-well plate. The plate was incubated statically at 24°C and imaged with a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C dissecting microscope at the indicated time points. After 72 hours, the pellicles were disrupted with a toothpick to promote pellicle visualization and to estimate pellicle strength. Representative images are shown from at least three independent experiments.

Squid colonization assay

For each competition experiment, overnight cultures of each strain grown in LBS with appropriate antibiotics were subcultured into SWT media and grown with shaking at 28°C. SWT subcultures were grown to mid-log phase and were then diluted with SWT to a standard OD600 of 0.2. Ten microliters of the diluted subculture were introduced to 100 ml of unfiltered Hawaiian offshore seawater (HOSW) (Chun et al., 2008). Freshly hatched E. scolopes juveniles were introduced to the HOSW with the inoculum and were exposed for 3 h to a 1:1 mixed inoculum containing a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled strain (ES114 or ΔlapD) and a red fluorescent protein (RFP)-labeled strain (ES114 or ΔlapD) with an inoculum between 9.8×103 and 2.09×104 CFU ml−1. After 3 h of exposure to bacteria in seawater, animals were rinsed 3 times in bacteria-free seawater, and were maintained in bacteria-free seawater until the endpoint of the assay. At 24 h post-inoculation, animals were assessed for luminescence via a TD-20/20 Luminometer (Turner Designs, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA). To ensure no background V. fischeri were introduced into the experiment, uninoculated animals maintained in HOSW served as an aposymbiotic control and were confirmed to be non-luminescent.

The University of Hawaii and the Federal Government have no official guidelines for the care and management of invertebrate animals, such as cephalopod squid, used in laboratory research; however, our laboratory strictly follows the procedures and recommendations in Boyle (Boyle, 1991). While our aquarium facility and protocols are outside the scope of the IACUC committee, they have been reviewed and approved by the University Veterinarian.

Plating

To estimate the population density of V. fischeri that successfully colonized the light organ, squid were rinsed and frozen at −80°C to then be homogenized and plated following previously defined procedures (Stabb and Ruby, 2003, Bongrand et al., 2016). Dilutions of the homogenate were plated onto LBS and CFU were counted after 1 day of growth and the fluorescence of colonies checked on a fluorescence dissecting microscope. The relative competitive index was used to describe the effectiveness of colonization by two competing strains as compared to the initial inoculum as previously described (Bongrand et al., 2016, Stabb and Ruby, 2003).

Sample preparation and imaging

For visualization of V. fischeri that colonized the light organ, animals were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde in marine phosphate-buffered saline (mPBS: 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 450 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and then washed three times for 30 min in mPBS prior to removal of the light organ by dissection. Light organs were then counterstained with TOPRO-3 and mounted on slides as described previously (Essock-Burns et al., In Press). Laser scanning confocal microscopy was performed using an upright Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany), located at the University of Hawaiʻi-Mānoa (UHM) Kewalo Marine Laboratory. Images were analyzed using FIJI (ImageJ) (Schindelin et al., 2012).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Louise Lie for the initial identification of lapV as a putative biofilm factor, Ali Razvi for generation of the ΔpdeV mutant, Matt Rishel for generating the pMJR4 plasmid, and members of the Visick lab for valuable scientific discussions during the development of this project. We also thank Daniel Arencibia who aided in dissections and plating assays. This work was supported by NIH General Medical Sciences grants R01 GM114288 and R35 GM130355. The squid colonization work was supported by NIH R37 AI50661, COBRE P20 GM125508 and GM135254 and an NSF INSPIRE Grant MCB1608744.

REFERENCES

- AMBROSIS N, BOYD CD, O TOOLE GA, FERNÁNDEZ J & SISTI F 2016. Homologs of the LapD-LapG c-di-GMP effector system control biofilm formation by Bordetella bronchiseptica. PLoS One, 11, e0158752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASCHTGEN M-S, BRENNAN CA, NIKOLAKAKIS K, COHEN S, MCFALL-NGAI M & RUBY EG 2019. Insights into flagellar function and mechanism from the squid–vibrio symbiosis. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, 5, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BASSIS CM & VISICK KL 2010. The cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase BinA negatively regulates cellulose-containing biofilms in Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol, 192, 1269–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOETTCHER KJ & RUBY EG 1990. Depressed light emission by symbiotic Vibrio fischeri of the sepiolid squid Euprymna scolopes. J Bacteriol, 172, 3701–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BONGRAND C, KOCH EJ, MORIANO-GUTIERREZ S, CORDERO OX, MCFALL-NGAI M, POLZ MF & RUBY EG 2016. A genomic comparison of 13 symbiotic Vibrio fischeri isolates from the perspective of their host source and colonization behavior. ISME J, 10, 2907–2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORLEE BR, GOLDMAN AD, MURAKAMI K, SAMUDRALA R, WOZNIAK DJ & PARSEK MR 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses a cyclic-di-GMP-regulated adhesin to reinforce the biofilm extracellular matrix. Mol Microbiol, 75, 827–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYD A & CHAKRABARTY AM 1994. Role of alginate lyase in cell detachment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol, 60, 2355–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYD CD, CHATTERJEE D, SONDERMANN H & O’TOOLE GA 2012. LapG, required for modulating biofilm formation by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0–1, is a calcium-dependent protease. J Bacteriol, 194, 4406–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYD CD, SMITH TJ, EL-KIRAT-CHATEL S, NEWELL PD, DUFRÊNE YF & O’TOOLE GA 2014. Structural features of the Pseudomonas fluorescens biofilm adhesin LapA required for LapG-dependent cleavage, biofilm formation, and cell surface localization. J Bacteriol, 196, 2775–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYLE P 1991. The UFAW Handbook on the Care and Management of Cephalopods in the Laboratory, Herts, UK, Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- BROOKS JF, GYLLBORG MC, CRONIN DC, QUILLIN SJ, MALLAMA CA, FOXALL R, WHISTLER C, GOODMAN AL & MANDEL MJ 2014. Global discovery of colonization determinants in the squid symbiont Vibrio fischeri. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 111, 17284–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROOKS JF & MANDEL MJ 2016. The histidine kinase BinK Is a negative regulator of biofilm formation and squid colonization. J Bacteriol, 198, 2596–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUMBA L, MASIN J, MACEK P, WALD T, MOTLOVA L, BIBOVA I, KLIMOVA N, BEDNAROVA L, VEVERKA V, KACHALA M, SVERGUN DI, BARINKA C & SEBO P 2016. Calcium-driven folding of RTX domain β-rolls ratchets translocation of RTX proteins through type I secretion ducts. Mol Cell, 62, 47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSCHER AZ, GRASS S, HEUSER J, ROTH R & ST GEME JW 2006. Surface anchoring of a bacterial adhesin secreted by the two-partner secretion pathway. Mol Microbiol, 61, 470–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATTERJEE D, BOYD CD, O’TOOLE GA & SONDERMANN H 2012. Structural characterization of a conserved, calcium-dependent periplasmic protease from Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol, 194, 4415–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOU SH & GALPERIN MY 2016. Diversity of cyclic di-GMP-binding proteins and mechanisms. J Bacteriol, 198, 32–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUA SL, LIU Y, YAM JK, CHEN Y, VEJBORG RM, TAN BG, KJELLEBERG S, TOLKER-NIELSEN T, GIVSKOV M & YANG L 2014. Dispersed cells represent a distinct stage in the transition from bacterial biofilm to planktonic lifestyles. Nat Commun, 5, 4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUN CK, TROLL JV, KOROLEVA I, BROWN B, MANZELLA L, SNIR E, ALMABRAZI H, SCHEETZ TE, BONALDO MEF, CASAVANT TL, SOARES MB, RUBY EG & MCFALL-NGAI MJ 2008. Effects of colonization, luminescence, and autoinducer on host transcription during development of the squid-vibrio association. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 105, 11323–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIOFU O, ROJO-MOLINERO E, MACIÀ MD & OLIVER A 2017. Antibiotic treatment of biofilm infections. APMIS, 125, 304–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COOLEY RB, O’DONNELL JP & SONDERMANN H 2016. Coincidence detection and bi-directional transmembrane signaling control a bacterial second messenger receptor. Elife, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESSOCK-BURNS T, BONGRAND C, GOLDMAN WE, RUBY EG & MCFALL-NGAI MJ In Press. Interactions of symbiotic partners drive the development of a complex biogeography in the Squid-Vibrio symbiosis. mBio. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLEMING D & RUMBAUGH KP 2017. Approaches to dispersing medical biofilms. Microorganisms, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FONG JNC & YILDIZ FH 2015. Biofilm Matrix Proteins. Microbiol Spectr, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GINALSKI K, KINCH L, RYCHLEWSKI L & GRISHIN NV 2004. BTLCP proteins: a novel family of bacterial transglutaminase-like cysteine proteinases. Trends Biochem Sci, 29, 392–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GJERMANSEN M, NILSSON M, YANG L & TOLKER-NIELSEN T 2010. Characterization of starvation-induced dispersion in Pseudomonas putida biofilms: genetic elements and molecular mechanisms. Mol Microbiol, 75, 815–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GJERMANSEN M, RAGAS P, STERNBERG C, MOLIN S & TOLKER-NIELSEN T 2005. Characterization of starvation-induced dispersion in Pseudomonas putida biofilms. Environ Microbiol, 7, 894–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAF J, DUNLAP PV & RUBY EG 1994. Effect of transposon-induced motility mutations on colonization of the host light organ by Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol, 176, 6986–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUILHEN C, FORESTIER C & BALESTRINO D 2017. Biofilm dispersal: multiple elaborate strategies for dissemination of bacteria with unique properties. Mol Microbiol, 105, 188–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUTTULA D, YAO M, BAKER K, YANG L, GOULT BT, DOYLE PS & YAN J 2019. Calcium-mediated protein folding and stabilization of Salmonella biofilm-associated Protein A. J Mol Biol, 431, 433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]