Abstract

Background:

Diagnostic criteria for apathy have been published but have yet to be evaluated in the context of clinical trials. The Apathy in Dementia Methylphenidate Trial 2 (ADMET 2) operationalized the diagnostic criteria for apathy (DCA) into a clinical-rated questionnaire informed by interviews with the patient and caregiver.

Objective:

The goal of the present study was to compare the classification of apathy using the DCA with that using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-apathy (NPI-apathy) subscale in ADMET 2. Comparisons between NPI-Apathy and Dementia Apathy Interview Rating (DAIR) scale, and DCA and DAIR were also explored.

Methods:

ADMET 2 is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial examining the effects of 20mg/day methylphenidate on symptoms of apathy over 6 months in patients with mild to moderate AD. Participants scoring at least 4 on the NPI-Apathy were recruited. This analysis focuses on cross-sectional correlations between baseline apathy scale scores using cross-tabulation.

Results:

Of 180 participants, the median age was 76.5 years and they were predominantly white (92.8%) and male (66.1%). The mean (± SD) scores were 7.7 ± 2.4 on the NPI-apathy, and 1.9 ± 0.5 on the DAIR . Of those with NPI-defined apathy, 169 (93.9%, 95%CI 89.3%−96.9%) met DCA diagnostic criteria. The DCA and DAIR overlapped on apathy diagnosis for 169 participants (93.9%, 95%CI 89.3%−96.9%).

Conclusion:

The measurements used for the assessment of apathy in patients with AD had a high degree of overlap with the DCA. The NPI-apathy cut-off used to determine apathy in ADMET 2 selects those likely to meet DCA criteria.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, apathy, dementia

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has an estimated prevalence of 50 million persons worldwide (1) and an incidence of 10 million cases per year (1–3), making it the most common form of dementia. While neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) are common in AD, apathy is particularly frequent, affecting up to 70% of patients (4). Apathy has been broadly defined as a loss of interest in daily activities and diminished goal-directed behavior in the absence of depression and other mood changes (5)(6, 7). This NPS is associated with greater functional impairment, greater caregiver burden, increased risk of institutionalization, poorer quality of life, and higher costs of care (8–15). Accordingly, apathy has emerged as an important treatment target in AD (12, 16), and its accurate assessment has become paramount.

A wide variety of tools are available to assess severity of apathy in AD in clinical research (17). Given the documented lack of insight associated with apathy (18, 19) and the difficulty associated with NPS assessment in advanced AD, the tools used to assess apathy for this population are generally based on caregiver report. As reviewed recently (17), the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) (20) and the Dementia Apathy Interview and Rating (DAIR) (21) are particularly suited for use in clinical trials due to good psychometric properties, but few data compare their performance in the context of a clinical trial. Importantly, there are no validated cut-offs on those scales to diagnose apathy.

Validation of any assessment requires comparison to a gold standard of diagnosis. To that end, the European Psychiatric Association assembled a task force in 2008 to develop diagnostic criteria for apathy in AD and other neuropsychiatric disorders (7), designed to be employed in both clinical practice and research studies. The resulting criteria had four requirements for a diagnosis of apathy: A) the symptoms have persisted for four weeks; B) the presence of two of three dimensions of apathy (reduced goal-directed behavior, goal-directed initiative, and emotions); C) these symptoms must cause functional impairment, and; D) these symptoms must not be exclusively explained by or due to physical or motor abilities, to diminished level of consciousness or to the direct physiological effects of a substance. Those criteria were validated by Mulin et al.(22) in several patient populations including AD.

The Apathy in Dementia Methylphenidate Trial 2 (ADMET 2) operationalized the above diagnostic criteria for apathy (DCA) into a clinician-rated questionnaire informed by interviews with the patient and caregiver (23). The ADMET 2 protocol defined clinically significant apathy based on the NPI-apathy subscale.

The goal of the present study was to compare the classification of apathy using the DCA with that using the NPI-apathy subscale in ADMET 2. Comparisons between NPI-Apathy and Dementia Apathy Interview Rating (DAIR) scale, and DCA and DAIR were also explored.

METHODS

ADMET 2 is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase-III trial examining the efficacy and safety of 20 mg/day methylphenidate on symptoms of apathy in patients with mild to moderate AD (23). AD patients with clinically significant apathy were recruited from 10 clinical centers across North America and randomized to methylphenidate or placebo in a 1:1 ratio. All participating caregivers also received a standardized psychosocial intervention similar to interventions used in comparable AD trials (24, 25). This trial was approved by the local institutional review boards of all clinical centers, as well as by the Johns Hopkins University for the Data Coordinating Center and the Study Chair’s Office. The study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02346201).

Participants

Study participants or their legally authorized representative and caregivers provided informed consent. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are comprehensively detailed elsewhere (23), but are summarized here. Eligible participants had a diagnosis of possible or probable AD (NINCDS-ADRDA criteria) (26) with a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (27) score of 10–28 and a NPI-apathy frequency times severity score greater than or equal to 4. Female participants were post-menopausal for at least 2 years or had a hysterectomy. Exclusion criteria included: 1) current diagnosis of major depressive episode, or clinically significant agitation/aggression, delusions, or hallucinations based on the NPI; 2) current treatment with medications that prohibited the safe and concurrent use of methylphenidate, such as any amphetamine product, antipsychotics, bupropion, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants; 3) use of trazodone >50mg daily or lorazepam >0.5 mg daily for indications other than insomnia or benzodiazepines within 30 days preceding randomization; 4) participants with contraindications for the use of methylphenidate including closed angle glaucoma, pheochromocytoma, uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, tachycardia (heart rate ≥100 beats per minute), uncontrolled hypertension or any other cardiovascular or cerebrovascular abnormalities deemed to be clinically significant by study physician.

Measures

Diagnostic Criteria for Apathy (DCA): The DCA is a questionnaire that was developed to operationalize the consensus diagnostic criteria for apathy published by the European Psychiatric Association (7). This questionnaire was completed by the study physician/clinician based on clinical assessment and information obtained from the patient and caregiver. Participants were considered apathetic (DCA+) if they meet all four criteria (A through D) as described above.

Neuropsychiatric Inventory Apathy subscale (NPI-apathy): The NPI is a structured interview of the primary caregiver assessing 12 behavioral disturbances, including apathy, in the patient over the past 4 weeks (20). Specifically, the presence of apathy is determined with a screening question followed by eight sub-questions to characterize apathy under the NPI apathy/indifference domain. The caregiver rates the frequency of symptoms on a 4-point scale and symptom severity on a 3-point scale. The total subscale score is calculated by multiplying frequency and severity, with higher scores representing greater apathy. In this study, clinically significant apathy was defined as apathy that was present “very frequently” or “frequently” and of “moderate” or “marked” severity with frequency times severity score greater than or equal to 4.

Dementia Apathy Interview and Rating (DAIR) (21): The DAIR is a structured interview conducted with the primary caregiver. It has 16-items that examine behavior, interest and engagement with the environment over the past 4 weeks, with each behavior assessed for frequency (on a 4-point scale) and for whether this is a change from premorbid behaviors. Total scores are obtained by summing all items that were rated as changed from premorbid behavior, divided by the number of items completed, with higher scores representing greater average apathy. The DAIR score was divided into 2 categories: clinically non-apathetic (score ≤1.0) and apathetic (score 1.1–3.0).

Data Analyses

Data were obtained from an interim analysis of baseline assessments from the ADMET 2 study as of 8 October 2019. Participant demographics are presented as mean and standard deviations or percentages and 95% confidence interval (CI) of total study sample. Cross-sectional comparisons between apathy scale scores were assessed using cross tabulation. Comparisons included: 1) NPI-apathy by DCA, 2) NPI-apathy by DAIR and 3) DAIR by DCA. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics:

Baseline characteristics of study participants (n=180) are listed in Table 1. The median age of participants was 76.5 years (25th percentile = 71 years; 75th percentile = 81 years). Participants were predominantly white (92.8%) and male (66.1%). The majority of the participants were married (85.0%); thirteen were widowed (10.2%), seven were divorced (5.5%) and one had never married (0.8%). Most (75.6%) participants had more than a high school level of education.

Table 1:

Demographics and Dementia Apathy Interview Rating (DAIR) and Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) scores of study participants at baseline

| Total (n = 180) | DCA+ (n = 169) | DCA− (n = 11) | Test statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Male (%, 95%CI) | 119 (66.1, 59.2–73.0) | 111 (65.7, 58.0–72.8) | 8 (72.7, 39.0–94.0) | Fisher’s exact | 0.752 |

| Mean age ± SD | 75.9 ± 8.0 | 75.8 ± 8.04 | 77.6 ± 8.12 | t = 0.72 | 0.470 |

| Married (%, 95%CI) | 153 (85.0, 79.8–90.2) | 143 (84.6, 78.3–89.7) | 10 (90.9, 58.7–99.8) | Fisher’s exact | 1.000 |

| Caucasian (%, 95%CI) | 167 (92.8, 89.0–96.6) | 156 (92.3, 87.2–95.8) | 11 (100, 71.5–100.0) | Fisher’s exact | 1.000 |

| Greater than high school education (%, 95%CI) | 136 (75.6, 69.3–81.8) | 126 (74.6, 67.3–80.9) | 10 (90.9, 58.7–99.8) | Fisher’s exact | 0.299 |

| Smoking history (%, 95%CI) | 81 (45.0, 37.7–52.3) | 75 (44.4, 36.8–52.2) | 6 (54.5, 23.4–83.3) | Fisher’s exact | 0.546 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Myocardial infarction (%, 95%CI) | 7 (3.9, 1.1–6.7) | 5 (2.9, 1.0–6.8) | 2 (18.2, 2.3–51.8) | Fisher’s exact | 0.060 |

| Hypertension (%, 95%CI) | 106 (58.9, 51.7–66.1) | 101 (59.8, 52.0–67.2) | 5 (45.5, 16.7–76.6) | Fisher’s exact | 0.363 |

| Coronary artery disease (%, 95%CI) | 30 (16.7, 11.2–22.1) | 29 (17.2, 11.8–23.7) | 1 (9.1,0.2–41.3) | Fisher’s exact | 0.694 |

| Stroke (%, 95%CI) | 8 (4.4, 1.4–7.5) | 7 (4.1, 1.7–8.3) | 1 (9.1,0.2–41.3) | Fisher’s exact | 0.402 |

| Diabetes (%, 95%CI) | 29 (16.1, 10.7–21.5) | 27 (15.9, 10.8–22.4) | 2 (18.2,2.3–51.8) | Fisher’s exact | 0.692 |

| Concomitant medications | |||||

| Cholinesterase inhibitors (%, 95%CI) | 143 (79.4, 73.5–85.3) | 133 (78.7, 71.7–84.6) | 10 (90.9, 58.7–99.8) | Fisher’s exact | 0.465 |

| Antidepressants (%, 95%CI) | 84 (46.7, 39.4–54.0) | 81 (47.9, 40.2–55.7) | 3 (27.3, 6.0–61.0) | Fisher’s exact | 0.224 |

| Psychotropics (%,95%CI) | 5 (2.8, 0.4–5.2) | 5 (2.9, 1.0–6.8) | 0 (0, 0.0–28.5) | Fisher’s exact | 1.00 |

| Apathy scales | |||||

| Mean NPI ± SD | 7.7 ± 2.4 | 7.8 ± 2.4 | 6.2 ± 2.6 | t = −2.18 | 0.030 |

| Mean DAIR ± SD | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | t = −1.53 | 0.128 |

DCA – Diagnostic Criteria for Apathy; SD – Standard deviation; CI – confidence interval

Apathy Outcomes:

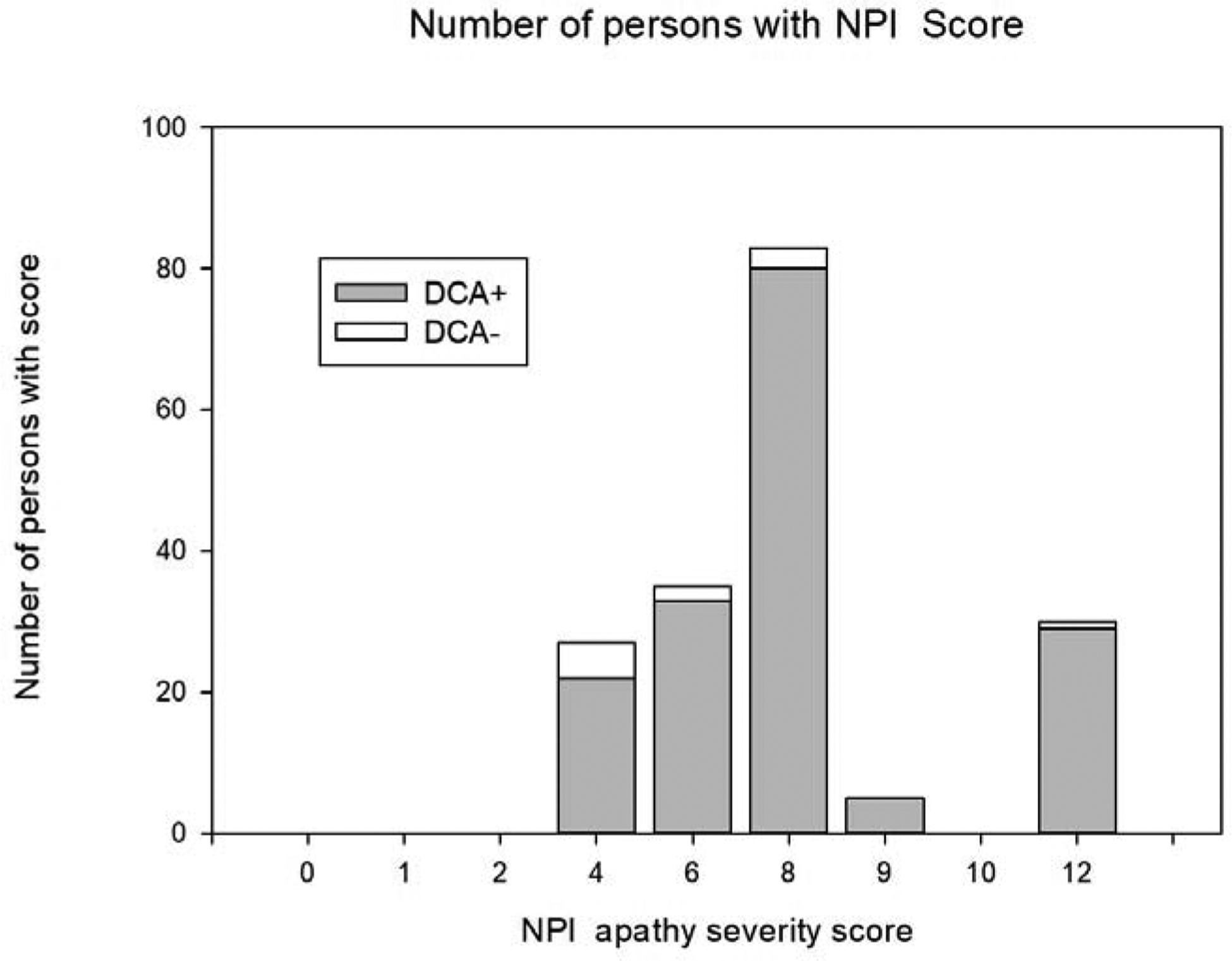

The mean NPI-apathy score (± standard deviation) was 7.7 ± 2.4 (Figure 1). There were 169 participants who also met DCA, therefore having a 93.9% (95%CI 89.3%−96.9%) overlap with the NPI-apathy subscale. Eleven (6.1%, 95%CI 3.1%−10.7%) participants met the NPI-apathy inclusion criteria but did not meet DCA.

Figure 1:

Histogram of Neuropsychiatric Inventory-apathy (NPI-apathy) severity score at baseline, divided by Diagnostic Criteria for Apathy+ (DCA+) and DCA−

There were no significant demographic differences between those who were apathetic based on the DCA and those who were not (Table 1). On the goal-directed behavior domain of the DCA, 173 participants (99.4%) endorsed diminished or loss of self-initiated goal-directed behavior and 149 (85.6%) endorsed diminished or loss of environment-stimulated behavior (Domain B1) (Table 2). On the goal-directed cognitive activity domain 171 (98.3%) endorsed a loss of spontaneous ideas and curiosity for routine and new events and 156 (89.6%) endorsed a loss of environment-stimulated ideas and curiosity for new and routine events (Domain B2). On the emotion domain 122 (70.1%) endorsed loss of spontaneous emotion, and 110 (63.2%) endorsed a loss of emotional responsiveness to positive or negative stimuli or events (Domain B3).

Table 2:

Responses to Diagnostic Criteria for Apathy (DCA) items

| Criterion | # answered yes (%, 95%CI) (n = 174) |

|---|---|

| Criterion A | 174 |

| Has there been a loss of or diminished motivation in comparison to the patient’s previous level of functioning and which is not consistent with his/her age or culture? | (100.0, 100.0–100.0) |

| Criterion B | 173 |

| Domain B1: Goal directed behavior | (99.4,98.3–100.0) |

| Loss of initiation | |

| Does the patient have loss of self-initiated behavior (e.g., starting conversation, doing basic tasks of day-to-day living, seeking social activities, communicating choices) ? | |

| Domain B1: Goal directed behavior | 149 |

| Loss of responsiveness | (85.6, 80.4–90.8) |

| Does the patient have loss of environment-stimulated behavior (e.g., responding to conversation, participating in social activities) ? | |

| Domain B2: Goal-directed cognitive activity | 171 |

| Loss of initiation | (98.3, 96.3–100.0) |

| Does the patient have loss of spontaneous ideas and curiosity for routine and new events (i.e., challenging tasks; recent news; social opportunities; personal, family, and social affairs) ? | |

| Domain B2: Goal-directed cognitive activity | 156 |

| Loss of responsiveness | (89.6,85.1–94.2) |

| Does the patient have loss of environment-stimulated ideas and curiosity for routine and new events (i.e., in the person’s residence, neighborhood, or community)? | |

| Domain B3: Emotion | 122 (70.1, 63.3–76.9) |

| Loss of initiation | |

| Does the patient have loss of spontaneous emotion, observed or self-reported (e.g., subjective feeling of weak or absent emotions, or observation by others of a blunted effect)? | |

| Domain B3: Emotion | 110 (63.2, 56.1–70.3) |

| Loss of responsiveness | |

| Does the patient have loss of emotional responsiveness to positive or negative stimuli or events (e.g., observer-reports of unchanging affect, or of little emotional reaction to exciting events, personal loss, serious illness, emotional-laden news) ? | |

| Criterion C | 174 (100.0) |

| Does this loss of or diminished motivation cause clinically significant impairment in personal, social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning? | |

| Criterion D | 174 (100.0) |

| Is this loss of or diminished motivation exclusively explained by or due to the following? | |

| B1+B2 (Behavior + Cognition) | 174 (100.0) |

| B1+B3 (Behavior + Emotion) | 136 (78.2, 72.0–84.3) |

| B2+B3 (Cognition + Emotion) | 136 (78.2, 72.0–84.3) |

| B1+B2+B3 (Behavior + Cognition+ Emotion) | 136 (78.2, 72.0–84.3) |

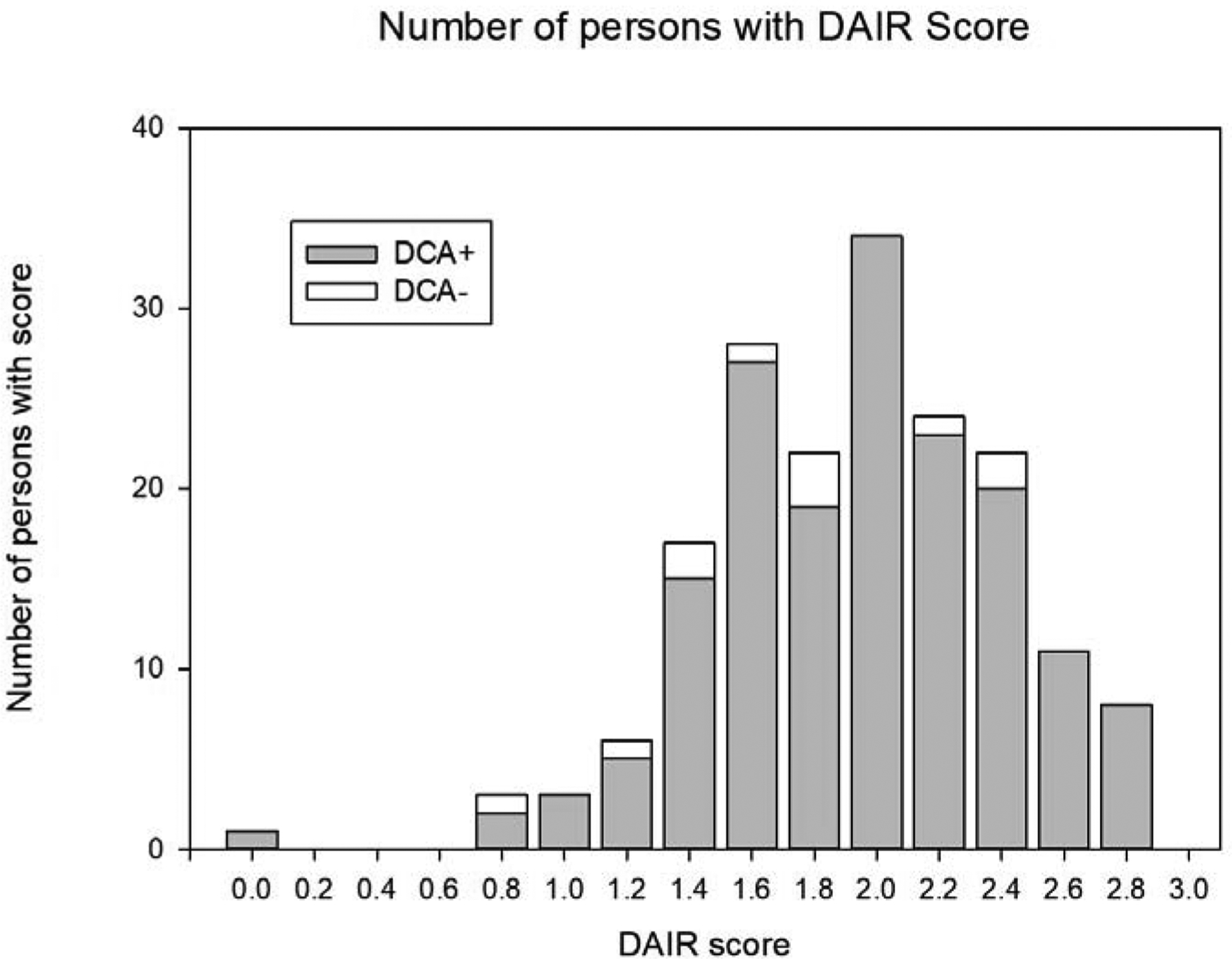

The mean DAIR score was 1.9 ± 0.5 and 172 participants (95.5%) were rated as apathetic (score > 1.0). Of these participants, 107 (62.2%) were rated as having mild to moderate apathy while 65 (37.8%) were rated as having severe apathy. There was a 95.5% (n=172) overlap between the NPI-apathy subscale and DAIR.

The DCA and DAIR overlapped on apathy diagnosis for 169 participants (93.9%, 95%CI 89.3%−96.9%); 7 participants (3.9%) diagnosed with apathy using the DCA did not endorse apathy according to the DAIR. In addition, 10 participants classified as apathetic on the DAIR did not meet DCA, of whom 7 participants (4.1%) classified as mildly to moderately apathetic by the DAIR and 3 participants (1.7%) as severely apathetic (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Histogram of apathy severity on Dementia Apathy Interview Rating (DAIR) at baseline vs. Diagnostic Criteria for Apathy (DCA)

DISCUSSION

Apathy is increasingly recognized as an important neuropsychiatric symptom in AD (28), and consequently, it is becoming a target for intervention. Clinical research has been hampered by the lack of standardized assessment tools and inconsistent definitions of apathy (29). The wide variety of tools that have been used in research (17) have made results difficult to compare between different studies, which in turn slows advances in the understanding and treatment of apathy. The DCA was developed to provide a standardized definition of apathy, suitable for use in both clinical and research settings (30). Despite the important potential impact of using the DCA in clinical research, to date, few clinical trials have characterized patients using these diagnostic criteria. Although there are multiple reasons for the limited use of the DCA in clinical trials, we believe that, at least in part, this is due to the lack of documented comparisons of the DCA against commonly used evaluation instruments such as the NPI. An NPI-apathy subscale score greater than or equal to 4 was used to define clinically significant apathy in the ADMET 2 study. The NPI-apathy subscale is considered a psychometrically robust measure of apathy (30) and has been commonly used to define apathy (17). In fact, NPI defined apathy has consistently been correlated with specific neuroimaging changes in AD (31). While the NPI-apathy subscale may rely on a caregiver to recall behaviors retrospectively, the screening question allows rapid determination of whether or not the patient has apathy symptoms without lengthy scoring, which is advantageous in clinical trials.

We found the NPI-apathy subscale score to have high overlap with the DCA, with 93.9% of those considered apathetic by the NPI (apathy subscale score ≥ 4) also meeting criteria for apathy using the DCA. The average NPI-apathy score in DCA+ individuals was 7.8 ± 2.4. This is similar to a study conducted by Mulin et al. in clinical practice, which found an NPI-apathy score of 6.9 ± 3.3 in DCA+ patients (22). While the ADMET 2 study had a higher proportion of DCA+ participants who endorsed goal-directed behavior and cognitive domains than DCA+ participants in the Mulin study, similar proportions of participants endorsed the emotion domain. In fact, the emotion domain was the least commonly endorsed in both studies, which may be due to the difficulty of using retrospective caregiver ratings to assess emotion (21). It has been suggested that the emotional domain could be best assessed with tests that are not affected by the patient’s insight and capacity to communicate (12).

The DAIR was developed to assess apathy in an AD population. It is assessed based on changes in behavior from prior to the onset of illness (17). It is also considered psychometrically sound (17). To date, the DAIR has had limited use in clinical trials. In our study, the DAIR also had a high level of overlap with the DCA, with 169 participants (93.9%) being classified as apathetic by both. Interestingly, some participants who had high DAIR scores were not considered apathetic by the DCA. The difficulty in assessing emotional change using the DCA could explain why participants rated as having apathy on the DAIR did not meet DCA criteria for apathy. While the DAIR assesses changes in emotion as well as changes in motivation and engagement, it does not separate items by apathy domains. Each item that is a change toward greater apathy from premorbid behavior is weighed equally.

In summary, as stated before, in a clinical trial of methylphenidate for apathy in AD, the NPI-apathy subscale cut-off was used to define clinically significant apathy. We found a high level of overlap between the DCA and NPI-apathy subscale as defined in the ADMET 2 study. We also found a high level of overlap between DAIR and DCA. Furthermore, participants with both high NPI-apathy and DAIR scores were very likely to be rated apathetic on DCA, and similarly, the majority of participants who met DCA+ criteria had elevated scores on NPI-apathy and DAIR.

Several limitations of this analysis should be noted. First, the assessment of the performance of the DCA was not the primary goal of the study, therefore, only overlap with other tools can be reported. Similarly, because the study was conducted only in those with apathy, false-positive and false-negative rates of the DCA cannot be determined. However, if one accepts the DCA as a gold standard diagnosis, and using the NPI-apathy subscale as the assessment of interest, it could be said that in our sample of 180 patients, there were 169 true-positive cases, and 11 false-positive cases. Therefore, it could be said that the NPI-Apathy subscale had a 93.9% positive predictive value. Finally, because ADMET 2 is designed as a treatment trial for apathy, there may be biases in the determination of DCA+ or DCA−.

Revised diagnostic criteria for apathy have since been developed (32), which consolidate the behavior and cognitive domains and add a novel domain, social interaction. Those criteria were developed to be transdiagnostic, with the viewpoint that apathy is a standalone construct. In addition, specific criteria for apathy in neurodegenerative disorders, which are consistent with the transdiagnostic criteria but take into consideration the need for assessment in the presence of cognitive impairment, have been developed by the International Society of Clinical Trial Methodology (ISCTM), in conjunction with the Alzheimer Association’s International Society of Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment (ISTAART) Neuropsychiatric Symptom Professional Interest Area (NPS-PIA) and the International Psychogeriatric Association (IPA). These updated diagnostic criteria overcome limitations of the previous criteria by being grounded in emerging neurocircuitry evidence and are consistent with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). Neuroimaging studies of apathy in AD have consistently reported associations between apathy and changes in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (31). Prefrontal regions of the brain have also been associated with apathy, specifically with impairments in decision making and planning (33). Neurocircuitry evidence supports distinct apathy domains and the separation of behavior (initiative) and cognition (interest) in apathy (34–36). Lack of initiative has been associated with the ACC (34), basal ganglia(36), and ventrolateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) (35) while lack of interest has been associated with the right middle OFC (34) and the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (PFC) (36). Impairments in the emotion domain have been associated with the superior and ventral PFC (34, 36) and the insula (35). Future research will be needed to operationalize these criteria.

While ADMET demonstrated that apathy can be a suitable target for drug intervention, ADMET 2 has now incorporated the DCA into its measures. The strong overlap between DCA, NPI-apathy, and DAIR supports the use of all of these tools for screening, diagnosis and assessment of apathy in AD. The results presented here suggest that these instruments are measuring a similar conceptualization of apathy in AD. They further indicate that the NPI-apathy subscale may be used as a rapid screening tool for eligibility in clinical trials. These findings provide a stronger methodological foundation for further observational and interventional studies of apathy in AD.

Highlights.

This study operationalized the diagnostic criteria for apathy (DCA) into a clinical rated questionnaire and validated it against the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-apathy (NPI-apathy) subscale; it also compared the DCA and NPI-apathy subscale to the Dementia Apathy Interview Rating (DAIR) scale.

The NPI apathy subscale selects patients likely to meet DCA. The DCA was highly concordant with other measures used for the assessment of apathy.

The strong concordance between the DCA, NPI-apathy and DAIR suggests that these instruments are measuring a similar conceptualization of apathy.

Acknowledgements:

ADMET 2 is funded by NIA, NIH, R01AG046543. The Sponsor had no role in the design of the trial, and is not involved in data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data.

Funding: ADMET 2 is funded by NIA, NIH, R01AG046543. The Sponsor had no role in the design of the trial, and is not involved in data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest: Disclosures/conflict of interests: Dr. Lanctôt reports grants from National Institute on Aging, during the conduct of the study; grants from Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer Society of Canada, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, National Institute on Aging; consulting fees from Abide, BioXcel, Cerevel, Exciva, Glide, Highmark, ICG Pharma, Kondor Pharma, Otsuka, outside the submitted work. Dr. Scherer, Ms. Li, Dr. Rosenberg report grants from National Institute of Aging, during the conduct of the study. NH reports research grants from Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, Alzheimer Society Canada, Brain Canada, Bright Focus Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, National Institute on Aging, Physician Services Incorporated. Dr. Padala reports grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Veterans Affairs during the conduct of the study. Dr. van Dyck reports grants from National Institute of Health for the conduct of the study; consulting fees from Roche, Elsai and Kyowa Kirin; and grants for clinical trials from Biogen, Roche, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Janssen, Novartis, Biohaven, Merck, Toyama, TauRx, and Forum, outside the submitted work. Dr. Levey reports grants from Eisai, Abbvie, Genentech, Novartis, Biogen; personal fees from Karuna Pharmaceuticals, GENUV, Cognito Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. Dr. Porsteinsson reports grants from National Institutes of Health for the conduct of the study; DSMB membership fees from Acadia, Functional Neuromodulation, Neurim, and Tetra Discovery Partners; consulting fees from Avanir, BioXcel, Eisai, Grifols, Lundbeck, Merck, Pfizer, and Toyama; grants for clinical trials from AstraZeneca, Avanir, Biogen, Biohaven, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Genentech/Roche, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Toyama, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02346201

REFERENCES

- 1.Patterson C World Alzheimer’s Report 2018 The state of the art dementia research: New frontiers. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia: WHO guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiu C, Kivipelto M, von Strauss E. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: occurrence, determinants, and strategies toward intervention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(2):111–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, Gornbein J. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46(1):130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marin RS. Differential diagnosis and classification of apathy. The American journal of psychiatry. 1990;147(1):22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marin RS. Apathy: a neuropsychiatric syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;3(3):243–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert P, Onyike CU, Leentjens AF, Dujardin K, Aalten P, Starkstein S, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease and other neuropsychiatric disorders. European psychiatry : the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists. 2009;24(2):98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurt C, Bhattacharyya S, Burns A, Camus V, Liperoti R, Marriott A, et al. Patient and caregiver perspectives of quality of life in dementia. An investigation of the relationship to behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26(2):138–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle PA, Malloy PF, Salloway S, Cahn-Weiner DA, Cohen R, Cummings JL. Executive dysfunction and apathy predict functional impairment in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(2):214–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vilalta-Franch J, Calvo-Perxas L, Garre-Olmo J, Turro-Garriga O, Lopez-Pousa S. Apathy syndrome in Alzheimer’s disease epidemiology: prevalence, incidence, persistence, and risk and mortality factors. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(2):535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrmann N, Lanctot KL, Sambrook R, Lesnikova N, Hebert R, McCracken P, et al. The contribution of neuropsychiatric symptoms to the cost of dementia care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(10):972–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nobis L, Husain M. Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2018;22:7–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu CW, Grossman HT, Sano M. Why Do They Just Sit? Apathy as a Core Symptom of Alzheimer Disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(4):395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nijsten JMH, Leontjevas R, Pat-El R, Smalbrugge M, Koopmans R, Gerritsen DL. Apathy: Risk Factor for Mortality in Nursing Home Patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(10):2182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spalletta G, Long JD, Robinson RG, Trequattrini A, Pizzoli S, Caltagirone C, et al. Longitudinal Neuropsychiatric Predictors of Death in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(3):627–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sultzer DL. Why Apathy in Alzheimer’s Matters. The American journal of psychiatry. 2018;175(2):99–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammad D, Ellis C, Rau A, Rosenberg PB, Mintzer J, Ruthirakuhan M, et al. Psychometric Properties of Apathy Scales in Dementia: A Systematic Review. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2018;66(3):1065–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Starkstein SE, Petracca G, Chemerinski E, Kremer J. Syndromic validity of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. The American journal of psychiatry. 2001;158(6):872–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishii S, Weintraub N, Mervis JR. Apathy: a common psychiatric syndrome in the elderly. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2009;10(6):381–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss ME, Sperry SD. An informant-based assessment of apathy in Alzheimer disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 2002;15(3):176–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulin E, Leone E, Dujardin K, Delliaux M, Leentjens A, Nobili F, et al. Diagnostic criteria for apathy in clinical practice. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2011;26(2):158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scherer RW, Drye L, Mintzer J, Lanctot K, Rosenberg P, Herrmann N, et al. The Apathy in Dementia Methylphenidate Trial 2 (ADMET 2): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin BK, Frangakis CE, Rosenberg PB, Mintzer JE, Katz IR, Porsteinsson AP, et al. Design of Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease Study-2. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):920–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drye LT, Ismail Z, Porsteinsson AP, Rosenberg PB, Weintraub D, Marano C, et al. Citalopram for agitation in Alzheimer’s disease: design and methods. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(2):121–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanctot KL, Aguera-Ortiz L, Brodaty H, Francis PT, Geda YE, Ismail Z, et al. Apathy associated with neurocognitive disorders: Recent progress and future directions. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2017;13(1):84–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cummings J, Friedman JH, Garibaldi G, Jones M, Macfadden W, Marsh L, et al. Apathy in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Recommendations on the Design of Clinical Trials. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2015;28(3):159–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarke DE, Ko JY, Kuhl EA, van Reekum R, Salvador R, Marin RS. Are the available apathy measures reliable and valid? A review of the psychometric evidence. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(1):73–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Theleritis C, Politis A, Siarkos K, Lyketsos CG. A review of neuroimaging findings of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. International psychogeriatrics. 2014;26(2):195–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robert P, Lanctot KL, Aguera-Ortiz L, Aalten P, Bremond F, Defrancesco M, et al. Is it time to revise the diagnostic criteria for apathy in brain disorders? The 2018 international consensus group. European psychiatry : the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists. 2018;54:71–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stella F, Radanovic M, Aprahamian I, Canineu PR, de Andrade LP, Forlenza OV. Neurobiological correlates of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: a critical review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;39(3):633–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benoit M, Clairet S, Koulibaly PM, Darcourt J, Robert PH. Brain perfusion correlates of the apathy inventory dimensions of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(9):864–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanton BR, Leigh PN, Howard RJ, Barker GJ, Brown RG. Behavioural and emotional symptoms of apathy are associated with distinct patterns of brain atrophy in neurodegenerative disorders. Journal of neurology. 2013;260(10):2481–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumfor F, Zhen A, Hodges JR, Piguet O, Irish M. Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia: Distinct clinical profiles and neural correlates. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior. 2018;103:350–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]