Abstract

Background

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of a conventional preservative system containing desferrioxamine mesylate (DFO) and optimize the composition of the system through mathematical models.

Methods

Different combinations of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), sodium metabisulfite (SM), DFO and methylparaben (MP) were prepared using factorial design of experiments. The systems were added to ascorbic acid (AA) solution and the AA content over time, at room temperature and at 40 °C was determined by volumetric assay. The systems were also evaluated for antioxidant activity by a fluorescence-based assay. Antimicrobial activity was assessed by microdilution technique and photometric detection against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida albicans and Aspergillus brasiliensis. A multi-criteria decision approach was adopted to optimize all responses by desirability functions.

Results

DFO did not extend the stability of AA over time, but displayed a better ability than EDTA to block the pro-oxidant activity of iron. DFO had a positive interaction with MP in microbial growth inhibition. The mathematical models showed adequate capacity to predict the responses. Statistical optimization aiming to meet the quality specifications of the ascorbic acid solution indicated that the presence of DFO in the composition allows to decrease the concentrations of EDTA, SM and MP.

Conclusion

DFO was much more effective than EDTA in preventing iron-catalyzed oxidation. In addition, DFO improved the inhibitory response of most microorganisms tested. The Quality by Design concepts aided in predicting an optimized preservative system with reduced levels of conventional antioxidants and preservatives, suggesting DFO as a candidate for multifunctional excipient.

Graphical abstract

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40199-020-00370-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Desferrioxamine, Antioxidant, Preservative, Experimental design, Design space

Introduction

The development of stable compositions is crucial for meeting the quality standards for medicines and cosmetics. Problems affecting the formulation integrity represent health risks and compromise the effectiveness and the safety of the treatment. Oxygen exposure and spoilage microorganisms are the main causes of product degradation. To avoid these problems, stability-enhancing agents should be added such as antioxidants, sequestrants, preservatives, buffering agents or pH modifiers [1–3].

In the pharmaceutical field, chelating agents are excipients used to sequester trace amounts of metals which arise from the water system, raw materials, manufacturing devices or storage containers. Such impurities can catalyze oxidation processes in the composition and consequently affect the quality of the product. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) is the most commonly chelating agent added in medicines and cosmetics to prevent oxidation [4, 5]. EDTA is also useful as a penetration enhancer of active pharmaceutical ingredients [6, 7] or to boost antimicrobials in preservative systems, due to the ability to remove multivalent cations from microbial cells, making the microorganism more vulnerable to antimicrobials [8, 9]. The sequestration of trace minerals required for microbial metabolism also improves the performance of other preservatives included in the formula [9–11].

Although the use of chelating agents in pharmaceutical formulations is a routine procedure, their selection should not be based on common practice, since in some cases the resulting metal complexes accelerate the formation of free radicals and become even more harmful [12]. Another problem related to the widespread use of chelating agents in cosmetic and medicinal products is the daily exposure of consumers [4, 13]. Cases of hypersensitivity to EDTA in pharmaceutical, personal care and sanitizing formulations have been reported [14–16]. Furthermore, the massive use of EDTA has been linked to negative impacts on the environment. Emphasis is given to the slow biodegradation of EDTA and EDTA complexes in waters and soils [17–20]. In this regard, the search for safer alternatives is a current trend [2, 9].

Chelating agents approved for medical use have applications limited to chelation therapies. Desferrioxamine mesylate (DFO) is a semi-synthetic drug derived from the bacterial siderophore desferrioxamine B and it is used to reverse iron overload in patients with thalassemia major [21–24]. DFO also affects iron availability to microorganisms, which represent the basis of new methods of microbial control, whether to compose novel treatment schemes or even preservative systems [25–27].

The concept of Quality by Design (QbD) consists in the design and construction of the quality of a product or process during its development. The main component of QbD is the Design of Experiments (DoE), which allows better results with smaller number of experiments. In the pharmaceutical industry, QbD is a useful tool at all stages of the production cycle and risk-based analysis. The main objectives of QbD are: to increase pharmaceutical development efficiency and process capability, to reduce variability, to achieve meaningful quality specifications, to improve the cause-effect analysis and to obtain regulatory flexibility [1, 28].

The applicability of statistical techniques for predicting the concentration of excipients in a drug formulation was demonstrated by Meka et al. (2012) [29]. The authors highlighted that optimization reduces the number of experiments and allows desirable product characteristics to be achieved at optimized levels of excipients (inputs), often reducing waste and costs.

The aim of this study was to investigate the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of a conventional preservative system containing DFO in the composition and optimize the system through mathematical models. The high molecular weight and poor lipophilicity gives DFO a restricted ability for tissue penetration [21, 23]. Such characteristics are desirable in our case, as water solubility and reduced absorption rate represent advantages for excipient candidates, especially for topical formulations. The use of very low concentrations represents acceptable costs and low toxicity. In addition, improved biodegradability can generally be expected from products of natural origin [10].

Methods

Chemicals

The following materials were used without further purification: desferrioxamine mesylate (Cristália, Brazil; a kind donation from Associação Brasileira de Talassemia), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt, methylparaben (Henrifarma, Brazil), sodium metabisulfite (Volp, Brazil), L-ascorbic acid (Roche, Switzerland; Sigma-Aldrich, USA), formic acid (Merck, Germany), dihydrorhodamine 123 dihydrochloride salt (DHR; Biotium, USA), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid, N-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES), potassium iodide, ferrous ammonium sulfate, nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA), Chelex-100, methanol (MeOH), amikacin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), potassium iodate (Dinâmica, Brazil), dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), sodium chloride, sulphuric acid (Synth, Brazil), chloramphenicol and nystatin (U.S. Pharmacopeia, USA).

Microbial strains and culture media

Standard strains of bacteria and fungi were employed as recommended elsewhere [30]: Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 (Gram-positive bacteria), Escherichia coli ATCC 8739 (Gram-negative bacteria), Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 9027 (Gram-negative bacteria) and Candida albicans ATCC 10231 (yeast) from Instituto Adolfo Lutz (Brazil), Aspergillus brasiliensis ATCC 16404 (mold) from Microbiologics Lab-Elite (USA). Bacteria were cultured on Tryptone Soy Agar and Tryptone Soy Broth and fungi were cultured on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar and Sabouraud Dextrose Broth (BD Difco, USA).

Design of experiments (DoE) and sample preparation

The preservative system was designed with excipients commonly added as antioxidants/preservatives in the composition of water-based formulations, at usual concentration levels. The excipients selected were: ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; chelating agent), sodium metabisulfite (SM; antioxidant) and methylparaben (MP; preservative). Desferrioxamine mesylate (DFO) was included in the composition and its activity was compared to EDTA.

Aqueous solutions of ascorbic acid (AA) 5% (w/v) pH 3.5 were prepared with different combinations of EDTA (X1), SM (X2) and DFO (X3). The fractional factorial 33 design was adopted, considering 0.1% (w/v) of each compound as the maximum concentration level, the compound not added as the minimum concentration level and central points as the half of the concentration of the variables [28]. The solutions were assayed for AA content overtime. The systems were also evaluated at the maximum and minimum concentrations levels for antioxidant activity, by adding DFO in equimolar concentration to EDTA.

The systems tested for antimicrobial activity included different combinations of EDTA or DFO with SM and methylparaben (MP-X4). In this case, the full factorial 23 design was adopted, considering 0.1% (w/v) of each compound as the maximum concentration level and the compound not added as the minimum concentration level, plus a central point in triplicate [28].

All samples were prepared in ultrapure water 18.2 mΩ (Elga-Veolia Purelab, England). A mixture of MeOH/DMSO 1:1 (v/v) was used to prepare a 5x stock solution of MP. All samples tested in the antimicrobial assay were filtered through 0.22 μm PVDF membranes (Merck Millipore, USA).

Determination of ascorbic acid in the compositions

The aqueous solutions of AA were aliquoted in clear and capped polypropylene tubes. One group was stored at room temperature and assessed for AA concentration at times 0, 1, 2, 7, 14, 28, 42, 56, 70 and 84 days. The average temperature recorded during the study was 23.5 ± 2.5 °C. The other group was stored in a heating chamber at 40 ± 1 °C (Binder, Germany) and assessed for AA concentration at times 0, 1, 2, 7, 14, 28, 42, 49 and 56 days. AA was quantified by iodometric titration [31]. An automatic titration system (905 Titrando, Metrohm, Switzerland) equipped with platinum ring electrode and controlled by Tiamo® software was employed. The titrant consisted of potassium iodate volumetric standard solution 0.02 M, dispensed by a certified dosing device. AA solutions were titrated by adding 1 mL of sample (equivalent to 50 mg AA) and 1 mL of potassium iodide 10% (w/v) in water acidified with sulfuric acid 20% (v/v), under stirring with a magnetic bar. The method was previously validated for specificity, precision (repeatability), accuracy and linearity [32]. The reference values adopted for the validation parameters were relative standard deviation (RSD) < 5%, analyte recovery from 98 to 102% and coefficient of determination (R2) > 0.99. AA concentration (mg/mL) was calculated as the volume of titrant*8.806.

Antioxidant activity

Antioxidant activity was evaluated according to Esposito et al. (2003) [33]. The redox-active standard Fe/NTA was prepared at 10 mM (1:1 metal/ligand molar ratio) in ultrapure water. A solution containing DHR 50 μM and ascorbic acid 40 μM was prepared in iron-free HEPES-buffered saline (HEPES 20 mM, NaCl 150 mM, pH 7.4), previously treated with Chelex-100 (1 g/100 mL). Samples were diluted (1/1000) in ultrapure water, in the presence or absence of Fe/NTA 2 μM (final concentration). Ultrapure water alone was also spiked with iron. Aliquots of 10 μL of both Fe-spiked and non-Fe-spiked samples and ultrapure water were transferred in duplicates to 96-well microplate and treated with 90 μL of DHR/ascorbic acid solution. Fluorescence kinetics curves were recorded every 2 min for 60 min at 37 °C, in a BMG FluoStar Optima microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Germany) with a 485/520 nm excitation/emission filter pair. Slope values (fluorescence intensity/min) were used to evaluate the oxidation rate of DHR.

Antimicrobial activity

Antimicrobial activity was evaluated by broth microdilution using 96-well microplates [34]. The microbial suspensions were prepared in saline solution 0.9% (w/v) and standardized at 0.5 Mc Farland scale or by plate count (mold). The inocula were adjusted to give a final concentration of 105–106 CFU/mL for bacteria and 104–105 CFU/mL for fungi. Quadruplicates of 20 μL of samples were added to 180 μL of each inoculum. Solutions of chloramphenicol or amikacin prepared in ultrapure water or nystatin prepared in MeOH/DMSO 1:1 (v/v) were used as positive antibiotic-containing controls (20 μg/well). All diluents of the samples and antibiotics were evaluated for microbial recovery. Wells in each microtiter dish were included to monitor microbial growth (inoculum) and broth sterility (no microorganisms). Cell viability of each inoculum was verified by plate count. Microplates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h (bacteria) or at 25 °C for 48 h (fungi). After incubation microbial growth was measured at 630 nm, using a multi-well scanning spectrophotometer (Synergy HT Biotek, USA). Mold sporulation was also monitored for 5 days by visual inspection. The percentage of microbial growth inhibition was calculated as: Growth inhibition (%) = 100 - (absorbance of the sample/absorbance of the inoculum)*100.

Statistical analysis and optimization of experimental data

The optimization of the composition regarding ascorbic acid stability over time, as well as the antioxidant and antimicrobial efficacy of the system was performed in two steps: 1) use of Design of Experiments (DoE) in order to identify the factors that significantly affect the responses and to establish mathematical models (multiple regression equations) that explain the response as a function of the factors under study; and 2) the use of desirability functions which allow to mathematically optimize all responses simultaneously in order to achieve the specification requirements of the composition.

The factors examined as independent variables were the concentration of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA-X1), sodium metabisulfite (SM-X2), desferrioxamine mesylate (DFO-X3) and methylparaben (MP-X4), in the range of 0 to 0.1% (w/v). The dependent variables were the following measured responses: determination of AA concentration (mg/mL) over time at room temperature (Y1) and at 40 °C (Y2), antioxidant activity (Y3) expressed as fluorescence units/min, and antimicrobial activity expressed as percentage of microbial growth inhibition against Staphylococcus aureus (Y4), Escherichia coli (Y5), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Y6), Candida albicans (Y7) and Aspergillus brasiliensis (Y8). The results were evaluated by multiple regression analysis and it was adopted a significance level of 5% (p value ≤0.05).

After studying the effect of the independent variables on the responses, the levels of the excipients needed to obtain an optimum response were assessed, according to desirable quality criteria for AA solution. The desirability function was used to optimize the responses, each having a different target [28, 35]. The criteria adopted to represent an ideal scenario of quality were: (i) a decay of up to 10% of AA concentration (based on USP drug product monographs) within 90 to 120 days at room temperature (based on expiry date assigned for compounded medications) and a restrict time interval for exposing the formulation at 40 °C (based on experimental data); (ii) minimum oxidation rate (minimum and maximum values based on experimental data), and (iii) the reduction of at least 30% of the microbial load every 24 h (4 log cycles in 14 days) as fixed by USP challenge test conditions [30]. DoE and Design Space (DS) were drawn up using Minitab Statistical Software 17 (Minitab, USA). The statistical optimization was performed in Microsoft Office Excel 2016 (Microsoft, USA).

Results and discussion

The search for alternative excipients as well as the selection of optimum concentrations in the formula aim to reduce intolerance, toxicity and costs. In this work, we investigated the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of a preservative system containing DFO in the composition. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the t-Student tests for the regression equation coefficients for the responses (Y1 – Y8) as a function of the studied factors (X1 – X4) were performed to identify the significance of the factors tested on the measured responses (Online Resource 1 and 2).

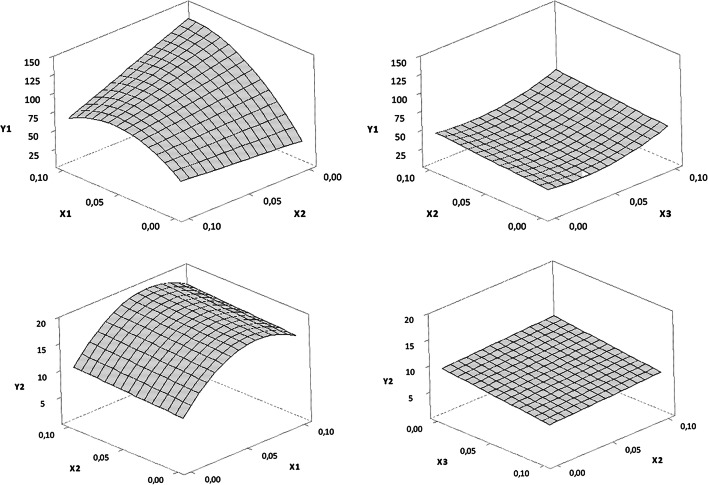

The best fitting polynomial models were represented as regression equations that predict the responses as a function of the concentration of excipients. The models exhibited adequate predictive capacity according to the values of the determination coefficients (Table 1). Surface graphics that relate the responses to the independent variables were constructed through mathematical models discussed below. The response as a function of two factors with fixed values for the others helps in understanding the main effects and interactions of these factors. In addition, the surface plots are very useful to predict responses at intermediate levels of the independent variables [29].

Table 1.

Regression equations and determination coefficients for ascorbic acid concentration (mg/mL) over time at room temperature (Y1) and at 40 °C (Y2), antioxidant activity of the system expressed as fluorescence units/min (Y3) and antimicrobial activity of the system expressed as percentage of microbial growth inhibition against Staphylococcus aureus (Y4), Escherichia coli (Y5), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Y6), Candida albicans (Y7) and Aspergillus brasiliensis (Y8), as a function of the percentage (w/v) of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (X1), sodium metabisulfite (X2), desferrioxamine mesylate (X3) and methylparaben (X4), in the range of 0 to 0.1% (w/v)

| Regression equation | R2 | R2 -adj | R2 -pred |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 = 34.84 + 2039 X1 + 114 X2–251 X3–10435 X12 + 4422 X32–7925 X1*X2 | 93.17 | 88.05 | 73.68 |

| Y2 = 9.52 + 266.2 X1 + 11.4 X2–23.0 X3–2005 X12 | 80.18 | 72.26 | 55.02 |

| Y3 = 294.9 + 15.57 X1–8.19 X2–101.31 X3 + 37.38 X1*X3 + 2.99 X2*X3 | 98.69 | 98.04 | 96.65 |

| Y4 = 92.90–48.7 X2–1748.3 X3–27.7 X4 + 11,253 X32–861 X2*X3 + 839 X2*X4 + 2032 X3*X4 | 95.57 | 95.05 | 93.83 |

| Y5 = 70.96–100.2 X1 + 29.53 X2–673.6 X3 + 328.83 X4 + 4623 X32–203 X2*X4 | 98.22 | 98.05 | 97.83 |

| Y6 = 9.654 + 2566.7 X1 + 6.55 X2–62.1 X3 + 7.17 X4–17058 X12 + 3753.9 X3*X4 | 99.89 | 99.88 | 99.87 |

| Y7 = 5.86 + 2549.5 X1–19.2 X2–36.2 X3 + 4.3 X4–16826 X12 + 625 X2*X4 + 5337 X3*X4 | 98.80 | 98.66 | 98.39 |

| Y8 = 78.953–199.5 X3 + 285.5 X4–3197 X32–1374 X42 + 5166.3 X3*X4 | 99.50 | 99.46 | 99.38 |

R2 = coefficient of determination; R2-adj = adjusted coefficient of determination; R2-pred = prediction coefficient of determination

As noted in Table 1, the models for determining AA content over time presented the lowest prediction capacities probably because they represent complex reactions related to the chemical degradation of the AA molecule. Indeed, ascorbic acid was included in this study because of the high susceptibility to oxidation triggered by ionization in aqueous solution. This is the main challenge for the development of stable formulations containing ascorbic acid. Other conditions such as high temperature, high pH, dissolved oxygen and catalytic effect of metal ions also influence AA stability [36].

The method used to determine AA content over time showed selectivity since no matrix interference was observed in AA recovery. Acceptance criteria for precision (RSD = 1.99%), accuracy (100.8%) and linearity (R2 = 0.9989) were met. Online Resources 3 and 4 show the measurements of the concentration of ascorbic acid after storing the solutions at room temperature and 40 °C, respectively. The surface graphics (Fig. 1) indicated that EDTA positively affected the AA stability in both exposure conditions while DFO and SM showed no significant effect. These results suggest that EDTA may have contributed by maintaining the acidity of the solution over time. Acidity is a very important factor for the effectiveness of topical formulations containing ascorbic acid. The aqueous formulations must be at a pH value lower than the pKa of AA itself (4.2), which increases AA stability and enhances its cutaneous permeation [36].

Fig. 1.

Response surface 3D plots showing the effect of the percentage (w/v) of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (X1), sodium metabisulfite (X2) and desferrioxamine mesylate (X3) on the ascorbic acid concentration (mg/mL) over time at room temperature (Y1) and at 40 °C (Y2). When not showed in the plot, the level of the factors X1 and X3 was fixed at zero

On the other hand, it was found that DFO drastically reduced the iron-mediated oxidation of DHR, while EDTA increased it (Fig. 2). The efficiency of DFO can be explained by both the high stability of the Fe/DFO complex and its very negative reduction potential (Fe(III)/DFO-Fe(II)/DFO), while EDTA is unable to bind iron(III) through all its coordination positions and does not decrease its reduction potential to the same extent, allowing the metal to continue keeping the catalytic cycle leading to free radical generation, even at neutral pH [23, 37]. However, the rate of reaction of DFO with iron depends on the initial chemical speciation of the metal: Fe/EDTA is much more stable than Fe/NTA, thus DFO may take longer to remove iron from Fe/EDTA [38], which would explain the relative inefficiency of DFO to quench the oxidant activity of Fe/EDTA.

Fig. 2.

Response surface 3D plots showing the effect of the percentage (w/v) of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (X1), sodium metabisulfite (X2) and desferrioxamine mesylate (X3) on the antioxidant activity expressed as fluorescence units/min (Y3). When not showed in the plot, the level of the factor X1 was fixed at zero, X2 at 5.3 μM (0.1% w/v) and X3 at 2.7 μM (0.1% w/v)

These findings support previous observations by Brovč et al. (2020) [12] showing that EDTA was not able to prevent biopharmaceutical formulations against oxidative damage by trace amounts of Fe(III). Interestingly, the authors found that DTPA (diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid), a chelator similar to DFO in that it blocks all the coordination positions of Fe(III), is a better choice than EDTA to block iron-mediated oxidative damage. For these reasons, EDTA is not the most effective substance for antioxidant strategies if iron is a possible contaminant.

Water-based formulations also provide an ideal environment for microbial proliferation. In order to extend product shelf life and protect consumers against infections, antimicrobial substances are added. A wide range of preservatives is approved for medicines and cosmetics, parabens being the most common [2, 10, 11, 39]. Unfortunately, preservatives may be highly allergenic, causing dermatitis and eczema in susceptible individuals [39, 40]. Novel strategies to improve the antimicrobial effectiveness of preservative systems consist of combining preservatives with antioxidants and chelating agents, ideally leading to decreased or even complete absence of preservatives in the composition [10, 11]. According to Polson et al. (2014) [41], the use of chelating agents with high affinity for iron may improve antimicrobial activity and reduce the concentration of preservatives in formulations. The authors have proposed environmentally friendly biocidal compositions comprising iron chelators, which may be useful in a variety of technological applications, as antiseptic agents in pharmaceutical and personal care compositions or to maintain the microbiological safety of products and industrial water systems. To the best of our knowledge, DFO has never been proposed for such applications.

The antimicrobial activity of DFO is strongly influenced by concentration and microbial strain. In some instances some microorganisms may develop mechanisms to acquire iron from siderophores produced by other species [27, 42–44]. On a side note, this promiscuous use of siderophores among different species could be explored therapeutically to deliver toxic metal ions to microorganisms [45].

We observed that the association DFO/SM and DFO/MP exhibited positive effect against S. aureus (Fig. 3), while both DFO/MP and EDTA/MP exhibited positive effect against E. coli (Fig. 4). P. aeruginosa (Fig. 5) and C. albicans (Fig. 6) showed similar response profiles with high percentages of growth inhibition at increasing DFO or EDTA concentrations, considering the different combinations of the components. A positive effect of DFO/MP was observed against A. brasiliensis (Fig. 7). The association of DFO with MP resulted in interaction and improved the growth inhibition responses of S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, C. albicans and A. brasiliensis. These findings were indicative of synergy and reveal an interesting strategy for preservation by associating these factors (preservative and chelating agent) at reduced concentrations.

Fig. 3.

Response surface 3D plots showing the effect of the percentage (w/v) of sodium metabisulfite (X2), desferrioxamine (X3) and methylparaben (X4) on antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus (Y4) expressed as percentage of microbial growth inhibition. When not showed in the plot, the level of the factors X1, X2, X3 and X4 was fixed at 0.1% (w/v)

Fig. 4.

Response surface 3D plots showing the effect of the percentage (w/v) of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (X1), sodium metabisulfite (X2), desferrioxamine (X3) and methylparaben (X4) on antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli (Y5) expressed as percentage of microbial growth inhibition. When not showed in the plot, the level of the factors X1, X2, X3 and X4 was fixed at 0.1% (w/v)

Fig. 5.

Response surface 3D plots showing the effect of the percentage (w/v) of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (X1), sodium metabisulfite (X2), desferrioxamine (X3) and methylparaben (X4) on antimicrobial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Y6) expressed as percentage of microbial growth inhibition. When not showed in the plot, the level of the factors X1, X2, X3 and X4 was fixed at 0.1% (w/v)

Fig. 6.

Response surface 3D plots showing the effect of the percentage (w/v) of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (X1), sodium metabisulfite (X2), desferrioxamine (X3) and methylparaben (X4) on antimicrobial activity against Candida albicans (Y7) expressed as percentage of microbial growth inhibition. When not showed in the plot, the level of the factors X1, X2, X3 and X4 was fixed at 0.1% (w/v)

Fig. 7.

Response surface 3D plot showing the effect of the percentage (w/v) of desferrioxamine (X3) and methylparaben (X4) on antimicrobial activity against Aspergillus brasiliensis (Y8) expressed as percentage of microbial growth inhibition. When not showed in the plot, the level of the factors X1 and X2 was fixed at 0.1% (w/v)

The synergistic or antagonistic effects of preservatives are not well established and this issue needs to be considered in the development of pharmaceutical and cosmetic formulations. The optimization of a preservative system of a cosmetic emulsion by the DS approach and the identification of interactions among the components of the system were demonstrated by Lourenço et al. (2015) [46]. The authors established the effectiveness concentration of parabens, imidazolidinyl urea and EDTA against B. cepacia, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, C. albicans and A. brasiliensis and used an alternative method to the conventional challenge test to evaluate the antimicrobial efficacy of the preservatives [30, 47].

In this work, the statistical optimization of the results by the desirability approach and overlay plot was applied to determine the appropriate levels of excipients to provide a composition that comply with the desired responses regarding the stabilization and preservation of the AA solution. Therefore, all the mathematical models (Table 1) were combined to design a preservative system able to meet critical quality attributes. Desirability functions have been applied to maximize both the stability of AA over time and the antimicrobial effectiveness of the system and to minimize the oxidation rate of the solution in the presence of iron. According to experimental data it was adopted a period of 7 to 14 days to determine AA content at 40 °C.

In this respect, a proposal able to meet all quality requirements while still reducing EDTA and MP in the composition was the one that maintained the maximum concentration (w/v) of DFO (0.1%), reduced by 75% the concentration of EDTA and MP (0.025% each) and removed SM from the system (Table 2). The DS resulted in contour graphics that illustrate the optimum concentration ranges of the excipient combinations as well as the acceptable limits to ensure the desired quality (Fig. 8). DS is a useful tool for assisting batch-to-batch quality control as the control strategies could be performed within the DS region. DS also enables regulatory flexibility since the post-registration changes will not be subject to notification and to the approval timeframe by regulatory agencies [1, 28].

Table 2.

Desirability functions values for ascorbic acid concentration (mg/mL) over time at room temperature (Y1) and at 40 °C (Y2), antioxidant activity of the system expressed as fluorescence units/min (Y3) and antimicrobial activity of the system expressed as percentage of microbial growth inhibition against Staphylococcus aureus (Y4), Escherichia coli (Y5), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Y6), Candida albicans (Y7) and Aspergillus brasiliensis (Y8) as a function of the concentration of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (X1), sodium metabisulfite (X2), desferrioxamine mesylate (X3) and methylparaben (X4), in the range of 0 to 0.1% (w/v)

| Input variables (X) | Output variables (Y) | Desirability function values |

|---|---|---|

| X1 = 0.025% (w/v) | Y1 = 98 days | d(Y1) = 0.3 |

| X2 = 0.000% (w/v) | Y2 = 13 days | d(Y2) = 0.8 |

| X3 = 0.100% (w/v) | Y3 = 191 au/min | d(Y3) = 0.5 |

| X4 = 0.025% (w/v) | Y4 = 35% of microbial reduction (24 h) | d(Y4) = 0.1 |

| Y5 = 56% of microbial reduction (24 h) | d(Y5) = 0.4 | |

| Y6 = 67% of microbial reduction (24 h) | d(Y6) = 0.5 | |

| Y7 = 69% of microbial reduction (24 h) | d(Y7) = 0.6 | |

| Y8 = 46% of microbial reduction (24 h) | d(Y8) = 0.2 |

Fig. 8.

Overlapped contour plots and Design Space regions for the determination of ascorbic acid concentration (mg/mL) over time at room temperature (Y1) and at 40 °C (Y2), for the antioxidant activity expressed as fluorescence units/min (Y3), and for the antimicrobial activity expressed as percentage of microbial growth inhibition against Staphylococcus aureus (Y4), Escherichia coli (Y5), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Y6), Candida albicans (Y7) and Aspergillus brasiliensis (Y8), as a function of the percentage (w/v) of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (X1), desferrioxamine mesylate (X3) and methylparaben (X4). When not showed in the plot, the level of the factor X1 was fixed at 0.025% (w/v), X2 at zero, X3 at 0.1% (w/v) and X4 at 0.025% (w/v)

Synergistic effects between antimicrobials and DFO with the reduction of minimum inhibitory concentration values have been previously demonstrated [42, 48, 49]. The studies included several antibiotic drugs, however there are few works regarding DFO as excipient and the association with preservative substances. Desai et al. (2004) [50] showed that DFO was effective in reducing oxidation and inhibiting microbial growth in propofol injectable emulsion. In this context, the results of the present study should be useful in future researches involving pharmaceutical development.

Conclusion

The Quality by Design concepts aided in predicting an optimized preservative system including DFO. DFO contributed to the inhibition of gram-negative bacteria and yeast and showed synergy with methylparaben, improving the inhibitory response of most microorganisms tested. Furthermore, DFO was much more effective in preventing iron-catalyzed oxidation when compared to EDTA. The multiple response optimization allowed a reduction of the conventional antioxidants and preservatives in the composition, suggesting DFO as a candidate for multifunctional excipient.

Authors’contributions

ML planned and carried out the experimental protocols. BPE contributed to the evaluation of the antioxidant activity. FRL contributed to the design of the experiments and statistical analysis. TMK supervised all stages of the research. This study was part of PhD thesis of ML. All authors have been involved in drafting the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 41 kb)

(PDF 36 kb)

(PDF 13 kb)

(PDF 27 kb)

Compliance with ethical standards

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yu LX, Amidon G, Khan MA, Hoag SW, Polli J, Raju GK, Woodcock J. Understanding pharmaceutical quality by design. AAPS J. 2014;16(4):771–783. doi: 10.1208/s12248-014-9598-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halla N, Fernandes IP, Heleno SA, Costa P, Boucherit-Otmani Z, Boucheirt K, et al. Cosmetics preservation: a review on present strategies. Molecules. 2018;23(7):1–41. doi: 10.3390/molecules23071571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pifferi G, Santoro P, Pedrani M. Quality and functionality of excipients. Farmaco. 1999;54(1–2):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0014-827x(98)00101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrutyn ES. Deciphering chelating agent formulas. In: Cosmetics & Toiletries. 2013. https://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/formulating/function/aids/premium-deciphering-chelating-agent-formulas-215885521.html. Accessed 12 Nov 2019.

- 5.Chaturvedi S, Dave PN. Removal of iron for safe drinking water. Desalination. 2012;303:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kikuchi T, Suzuki M, Kusai A, Iseki K, Sasaki H. Synergistic effect of EDTA and boric acid on corneal penetration of CS-088. Int J Pharm. 2005;290(1–2):83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguilera A, Bermudez Y, Martínez E, Marrero MA, Muñoz L, Páez R, et al. Formulation development of a recombinant streptokinase suppository for hemorrhoids treatment. Biotecnol Apl. 2013;30(3):182–186. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alakomi H-L, Paananen A, Suihko M-L, Helander IM, Saarela M. Weakening effect of cell permeabilizers on gram-negative bacteria causing biodeterioration. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(7):4695–4703. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00142-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman A. Antimicrobial ingredients as preservative booster and components of self-preserving cosmetic products. Curr Microbiol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Varvaresou A, Papageorgiou S, Tsirivas E, Protopapa E, Kintziou H, Kefala V, et al. Self-preserving cosmetics. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2009;1(3):163–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2009.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narayanan M, Sekar P, Pasupathi M, Mukhopadhyay T. Self-preserving personal care products. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2017;39(3):301–309. doi: 10.1111/ics.12376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brovč EV, Pajk S, Šink R, Mravljak J. Protein formulations containing polysorbates: are metal chelators needed at all? Antioxidants (Basel). 2020;9(5):441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Genuis SJ, Birkholz D, Curtis L, Sandau C. Paraben levels in an urban community of Western Canada. ISRN Toxicol. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Rajan JP, Cornell R, White AA. A case of systemic contact dermatitis secondary to edetate disodium. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(4):607–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pruitt C, Warshaw EM. Allergic contact dermatitis from ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Dermatitis. 2010;21(2):121–122. doi: 10.1097/01206501-201003000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laborde-Castérot H, Villa AF, Rosenberg N, Dupont P, Lee HM, Garnier R. Occupational rhinitis and asthma due to EDTA-containing detergents or disinfectants. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55(8):677–682. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt CK, Brauch HJ. Impact of aminopolycarboxylates on aquatic organisms and eutrophication: overview of available data. Environ Toxicol. 2004;19(6):620–637. doi: 10.1002/tox.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto H, Tamura I, Hirata Y, Kato J, Kagota K, Katsuki S, et al. Aquatic toxicity and ecological risk assessment of seven parabens: Individual and additive approach. Sci Total Environ. 2011;410–411:102–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Haman C, Dauchy X, Rosin C, Munoz JF. Occurrence, fate and behavior of parabens in aquatic environments: a review. Water Res. 2015;68:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oviedo C, Rodríguez J. EDTA: the chelating agent under environmental scrutiny. Quim Nova. 2003;26(6):901–905. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrne SL, Krishnamurthy D, Wessling-Resnick M. Pharmacology of iron transport. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;53:17–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming RE, Ponka P. Iron overload in human disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(4):348–359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hider RC, Kong X. Chemistry and biology of siderophores. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27(5):637–657. doi: 10.1039/b906679a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breuer W, Ermers MJ, Pootrakul P, Abramov A, Hershko C, Cabantchik ZI. Desferrioxamine-chelatable iron, a component of serum non-transferrin-bound iron, used for assessing chelation therapy. Blood. 2001;97(3):792–798. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kontoghiorghes GJ, Kolnagou A, Skiada A, Petrikkos G. The role of iron and chelators on infections in iron overload and non iron loaded conditions: prospects for the design of new antimicrobial therapies. Hemoglobin. 2010;34(3):227–239. doi: 10.3109/03630269.2010.483662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu B, Kong XL, Zhou T, Qiu DH, Chen YL, Liu MS, Yang RH, Hider RC. Synthesis, iron(III)-binding affinity and in vitro evaluation of 3-hydroxypyridin-4-one hexadentate ligands as potential antimicrobial agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21(21):6376–6380. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holbein BE, Mira de Orduña R. Effect of trace iron levels and iron withdrawal by chelation on the growth of Candida albicans and Candida vini. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;307(1):19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukuda IM, Pinto CFF, Moreira CS, Saviano AM, Lourenço FR. Design of Experiments (DoE) applied to pharmaceutical and analytical quality by design (QbD) Braz J Pharm Sci. 2018;54(special issue):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meka VS, Nali SR, Songa AS, Battu JR, Kolapalli VR. Statistical optimization of a novel excipient (CMEC) based gastro retentive floating tablets of propranolol HCl and it's in vivo buoyancy characterization in healthy human volunteers. Daru. 2012;20:21. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-20-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United States Pharmacopeia. 37th ed. Rockville: The United States Pharmacopeial Convention; 2017.

- 31.Zenebon O, Pascuet NS, Tiglea P. Métodos físico-químicos para análise de alimentos. São Paulo: Instituto Adolfo Lutz; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.International Conference on Harmonisation . Validation of analytical procedures: text and methodology Q2(R1) Genebra: ICH; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esposito BP, Breuer W, Sirankapracha P, Pootrakul P, Hershko C, Cabantchik ZI. Labile plasma iron in iron overload: redox activity and susceptibility to chelation. Blood. 2003;102(7):2670–2677. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wayne PA. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. CLSI standard M07.11th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2018.

- 35.Candioti LV, Zan MMD, Cámara MS, Goicoechea HC. Experimental design and multiple response optimization. Using the desirability function in analytical methods development. Talanta. 2014;124:123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2014.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stamford NPJ. Stability, transdermal penetration, and cutaneous effects of ascorbic acid and its derivatives. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11(4):310–317. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller CJ, Rose AL, Waite TD. Importance of iron complexation for Fenton-mediated hydroxyl radical production at circumneutral pH. Front Mar Sci. 2016;3:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ihnat PM, Vennerstrom JL, Robinson DH. Solution equilibria of deferoxamine amides. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91(7):1733–1741. doi: 10.1002/jps.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lundov MD, Moesby L, Zachariae C, Johansen JD. Contamination versus preservation of cosmetics: a review on legislation, usage, infections, and contact allergy. Contact Derm. 2009;60(2):70–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deza G, Giménez-Arnau AM. Allergic contact dermatitis in preservatives: current standing and future options. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;17(4):263–268. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polson G, Jourden J, Zheng Q, Prioli RM, Ciccognani D, Choi S; Arch Chemicals, lnc. (US). Biocidal compositions comprising iron chelators. Patent WO 2014/059417 A1. 2014 Apr 17.

- 42.Gokarn K, Pal RB. Activity of siderophores against drug-resistant gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:61–75. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S148602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson MG, Corey BW, Si Y, Craft DW, Zurawski DV. Antibacterial activities of iron chelators against common nosocomial pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(10):5419–5421. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01197-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai YW, Campbell LT, Wilkins MR, Pang CN, Chen S, Carter DA. Synergy and antagonism between iron chelators and antifungal drugs in Cryptococcus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48(4):388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huayhuaz JAA, Vitorino HA, Campos OS, Serrano SHP, Kaneko TM, Espósito BP. Desferrioxamine and desferrioxamine-caffeine as carriers of aluminum and gallium to microbes via the Trojan horse effect. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2017;41:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lourenço FR, Francisco FL, Ferreira MR, Andreoli T, Löbenberg R, Bou-Chacra N. Design space approach for preservative system optimization of an anti-aging eye fluid emulsion. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;18(3):551–561. doi: 10.18433/j3j600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferreira MRS, Lourenço FR, Ohara MT, Bou-Chacra NA, Pinto TJA. An innovative challenge test for solid cosmetics using freeze-dried microorganisms and electrical methods. J Microbiol Methods. 2014;106:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Asbeck BS, Marcelis JH, van Kats JH, Jaarsma EY, Verhoef J. Synergy between the iron chelator deferoxamine and the antimicrobial agents gentamicin, chloramphenicol, cefalothin, cefotiam and cefsulodin. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1983;2(5):432–438. doi: 10.1007/BF02013900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hartzen SH, Frimodt-Møller N, Thomsen VF. The antibacterial activity of a siderophore. 3. The activity of deferoxamine in vitro and its influence on the effect of antibiotics against Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis and coagulase-negative staphylococci. APMIS. 1994;102(3):219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Desai NP, Yang A, Ci SX, De T, Trieu V, Soon-Shiong P; American Biosciences, Inc. (US). Compositions and methods of delivery of pharmacological agents. Patent WO 2004/052401, 2004 jun 24.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 41 kb)

(PDF 36 kb)

(PDF 13 kb)

(PDF 27 kb)