Abstract

Background

Osteoporotic-osteoarthritis is an incapacitating musculoskeletal illness of the aged.

Objectives

The anti-inflammatory and anti-catabolic actions of Diclofenac were compared with apigenin-C-glycosides rich Clinacanthus nutans (CN) leaf extract in osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats.

Methods

Female Sprague Dawley rats were randomized into five groups (n = 6). Four groups were bilateral ovariectomised for osteoporosis development, and osteoarthritis were induced by intra-articular injection of monosodium iodoacetate (MIA) into the right knee joints. The Sham group was sham-operated, received saline injection and deionized drinking water. The treatment groups were orally given 200 or 400 mg extract/kg body weight or 5 mg diclofenac /kg body weight daily for 28 days. Articular cartilage and bone changes were monitored by gross and histological structures, micro-CT analysis, serum protein biomarkers, and mRNA expressions for inflammation and catabolic protease genes.

Results

HPLC analysis confirmed that apigenin-C-glycosides (shaftoside, vitexin, and isovitexin) were the major compounds in the extract. The extract significantly and dose-dependently reduced cartilage erosion, bone loss, cartilage catabolic changes, serum osteoporotic-osteoarthritis biomarkers (procollagen-type-II-N-terminal-propeptide PIINP; procollagen-type-I-N-terminal-propeptide PINP; osteocalcin), inflammation (IL-1β) and mRNA expressions for nuclear-factor-kappa-beta NF-κβ, interleukin-1-beta IL-1β, cyclooxygenase-2; and matrix-metalloproteinase-13 MMP13 activities, in osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats comparable to Diclofenac.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that apigenin-C-glycosides at 400 mg CN extract/kg (about 0.2 mg apigenin-equivalent/kg) is comparable to diclofenac in suppressing inflammation and catabolic proteases for osteoporotic-osteoarthritis prevention.

Graphical abstract

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40199-020-00343-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Apigenin-C-glycosides, Anti-inflammatory, Osteoarthritis, Osteoporosis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis and osteoporosis are conjoint musculoskeletal ailments that cause serious debility in the aged. Osteoarthritis (OA) causes joint pains due to changes in the cartilage, synovium, ligaments, tendons, subchondrial bone, and periarticular soft tissues [1]. Osteoporosis (OP) is a bone loss condition, that decreases bone strength and enhances fracture risk [2]. The OA usually co-exists with osteoporotic bone loss in the elderly, particularly in postmenopausal women [3]. About 20% of OP sufferers had OA [4], and many OA patients due for joint arthroplasty also have severe bone loss [5], and have 10–20% increased fracture risk [6].

Diclofenac is the FDA approved nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to control inflammation, pain, and related symptoms in OA and bone fracture patients [7], but prolonged use may produce undesirable gastrointestinal and cardiovascular side-effects [8], and impair fracture healing [9]. Alternatively, plant extracts, components or dietary polyphenols/flavonoids have been traditionally used to reduce inflammation, protect cartilage and bone damage, and may provide a better option.

Clinacanthus nutans, is a Southeast Asian medicinal plant with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-tumor proliferation, analgesic and anti-microbial properties [10], without toxic effects even with long term use [11]. The leaves contain apigenin and apigenin-C-glycosides including vitexin, isovitexin, schaftoside and isoscaftoside [12, 13]. We hypothesized that the anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties of apigenin-C-glycosides rich Clinacanthus nutans (CN) leaf extract may be an effective alternative/complementary herbal therapy for OP/OA to NSAID such as Diclofenac. This study investigated whether the CN is protective against OP/OA cartilage and bone loss in ovariectomized and monosodium iodoacetate (MIA)-induced rat model, as compared to the NSAID, diclofenac.

Materials and methods

Extract preparation and characterization

Cleaned, dried, milled Clinacanthus nutans (CN) leaves were extracted in ten times its weight of 50% aqueous ethanol at ambient temperatures for 3 days with mechanical shaking, filtered, then rotary evaporated below 40 °C, before the final drying in a 50 °C oven and stored at 4 °C. The extract was analyzed on a HPLC-UV/DAD system (Waters Alliance 2695 with Waters 2996 photodiode array detector, Massachusetts, USA). The chromatography were run using a 250 mm × 4.6 mm, C18 column of 5 휇m particle size, (Dikma Technologies, California, USA) at 30 °C. The eluents were 0.05% (v/v) glacial acetic acid and methanol (solvent A and solvent B, respectively). The HPLC condition used was optimized at: 33–45% B for 0–25 min; 45–80% B for 25–40 min; 80–95% B for 40–45 min; 95% B for 45–50 min; with a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. The injection volume was 10 휇L and detection was at 330 nm. The apigenin derivatives were identified from the retention times of the peaks as compared with vitexin (PubChem CID: 5280441), isovitexin (PubChem CID: 162350), schaftoside (PubChem CID: 442658), and isoschaftoside (PubChem CID: 44257699) (ChromaDex, California, USA).

Animals and oral drug administration

The animal study protocols followed strictly the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines (IACUC), Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM/IACUC/AUP-R083/2014). Thirty 12-week-old female Sprague Dawley rats (about 240 ± 10 g each) were kept in solid-bottom plastic rat cages (3 rats /cage) with a 12-h light-dark cycle at ambient temperatures. They were allowed to acclimatized for 2 weeks on commercial rat pellet (Gold Coin™, Selangor, Malaysia), and tap water ad libitum. The rats were allocated into 5 groups randomly (n = 6): (1) Sham Control group given deionized water, (2) non-treated osteoporotic-osteoarthritis (OP/OA) given deionized water (osteoporotic+osteoarthritis), (3) osteoporotic-osteoarthritis orally given 200 mg extract/kg body weight (OP/OA+ 200 mg CN /kg), (4) osteoporotic-osteoarthritis given 400 mg extract /kg body weight (OP/OA + 400 mg CN /kg) and (5) osteoporotic-osteoarthritis given 5 mg Diclofenac /kg body weight (OP/OA + 5 mg Diclo/kg). Dose selection were based on previously reported CN safety studies [11, 14, 15]. Extracts were added into deionized water as vehicle and administered by oral gavage daily for 4 weeks, starting 2 weeks after monosodium iodoacetate injection (4 weeks after OVX) to enable OA and estrogen deficient bone loss development. All rats were exsanguinated at Week 10 after 4 weeks of treatment. Body weights were measured biweekly. All animals were included in the data collection and analysis.

Development of osteoporotic-osteoarthritis in vivo model

Anesthetized rats were bilateral ovariectomized via a midline incision for excising both ovaries. The Sham group underwent midline incision exposure only, followed by suturing. Rats were left for 14 days to completely heal from the surgery and develop estrogen-deficient osteoporosis. Osteoarthritis was induced with an intra-articular injection of 3 mg/50 μl of monosodium iodoacetate (MIA) (Sigma Aldrich, Missouri, USA) using a needle (26 G), through the patellar ligament of the right knee joint. Sham group received saline injection.

Gross evaluation and histological analysis

After 1 month, the animals were sacrificed, and the right knee joints dissected, then photographed (digital camera DMC-GF1, Panasonic, Osaka, Japan). Femur samples were fixed for 14 days in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution and subsequently decalcified with 8% formic acid for 4 weeks. Femur midpoint coronal sections (7 um thickness) were cut with a microtome (Leica RM2235, Germany) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The stained sections were photomicrographed using Olympus Box-Type FSX100 Imaging Device (Olympus Life Science, Tokyo, Japan). The histopathological features were evaluated by four double-blind observers according to the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) [16] and total modified Mankin [17] scores. The final minimized bias OARSI scores were calculated as `grade x stage’ [16]. The grade evaluated the severity of the cartilage damage: 0 (cartilage morphology intact); 1 (surface intact, with chondrocytes and cartilage morphology changes); 2 (surface discontinuity); 3 (vertical fissures); 4 (erosion); 5 (denudation) and 6 (deformation); while the stage evaluated the amount of damaged area: 0 (no OA activity); 1 (<10%); 2 (10–25%); 3 (25–50%); 4 (more than 50%).

The modified Mankin score is the total of 3 components (a + B + C) namely

(A) For structure: 0 (Normal); 1 (Irregular surface, including possible radial layer fissures); 2 (Superficial fibrillation); 3 (no superficial cartilage layers); 4 (Slight disorganization - cellular rows absent, some small superficial clusters); 5 (Fissures into calcified cartilage layer); 6 (Disorganization chaotic structures, clusters or small superficial clusters indicating osteoclast activity).

(B) For cellular abnormalities: 0 (Normal); 1 (Hypercellularity, and small superficial clusters); 2 (Clusters), 3 (Hypocellularity).

(C) For matrix staining intensity: 0 (Normal); 1 (Slight radial layer reduction); 2 (Reduced interterritorial matrix); 3 (Only the pericellular matrix was stained); 4 (No dye stain).

Micro-computed tomography (μCT) analysis

The micro-CT scanner (Skyscan 1076, Luxembourg, Belgium), with an X-ray voltage set at 72 kV, and the current, at 110 μA were used to analyze the right tibia. The X-ray projections were obtained at 0.5-degrees angular step with a 180° scanning angular range, and 18 μm per pixel resolution. The image slices were reconstructed with Skyscan NRecon software, which generated a series of planar transverse gray value images. The bone morphometry volumes of interest (VOI) were selected with a Skyscan CT-Analyser Software for semiautomatic contouring. The 3D tibial subchondral and metaphyseal trabecular cross-section images were generated by Skyscan CTVol v2.0 software. The microstructural parameters analyzed included subchondral bone volume /trabecular volume fraction (BV/TV), bone plate thickness (Pl.Th), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and trabecular number (Tb.N).

The blood serum protein markers were determined using ELISA kits (Elabscience Biotechnology, Wuhan, China) for IL-1β (interleukin 1 beta), PIINP (procollagen type II N-terminal propeptide), osteocalcin and PINP (procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide), read at 450 nm using Synergy H1 ELISA reader (BioTek, Vermont, USA).

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

The total mRNA were extracted from the tibio-femoral bone regions (containing cartilage and bone), and the qPCR was determined relative to beta actin (β-actin) gene expressions. The total mRNA from the right femoral head (containing cartilage and bone) was extracted with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The total RNA of each sample (250 ng) were reverse transcribed with RT2 First Strand kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Quantitative PCR for selected genes was performed using RT2 SYBR Green ROX FAST Mastermix (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Primers designing for the genes used and the Thermal cycling profile were as follows: NF-κβ, F-ACCTGAGTCTTCTGGACCGCTG and R-CCAGCCTTCTCCCAAGAGTCGT; COX-2, F-CCGGGTTGCTGGGGGAAGGA and R-CCACCAGCAGGGCGGGATACAG; IL-1β; F-GACCTGTTCTTTGAGGCTGACA and R-CTCATCTGGACAGCCCAAGTC; MMP-13, F-TCCCTGTTCAGCCATCCCTTG and R-TCGCTCTGGTAGCCCTTCTC; and β-actin, F-CGTTGACATCCGTAAAGACC and R-GCCACCAATCCACACAGA. Thermal cycling profile consisted of 5 min at 35 °C; 15 min at 94 °C; 50 cycles of 5 s at 94 °C (melting), 10 s at 57 °C (annealing); and 15 s at 72 °C (extension) using a CFX96 Touch qPCR System (Bio-rad, California, USA). Data were analyzed using an excel-based PCR Array Data Analysis Template from website GeneGlobe Data Analysis Center (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Transcript levels were normalized to beta actin (β-actin) levels and calculated based on ΔΔCT method, as described by the manufacturer’s instruction.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical analysis used IBM SPSS 22.0 statistical software package. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan post hoc test, with significance at p < 0.05 for differences between groups.

Results and discussion

Apigenin-C-glycosides profile of Clinacanthus nutans leaf extract

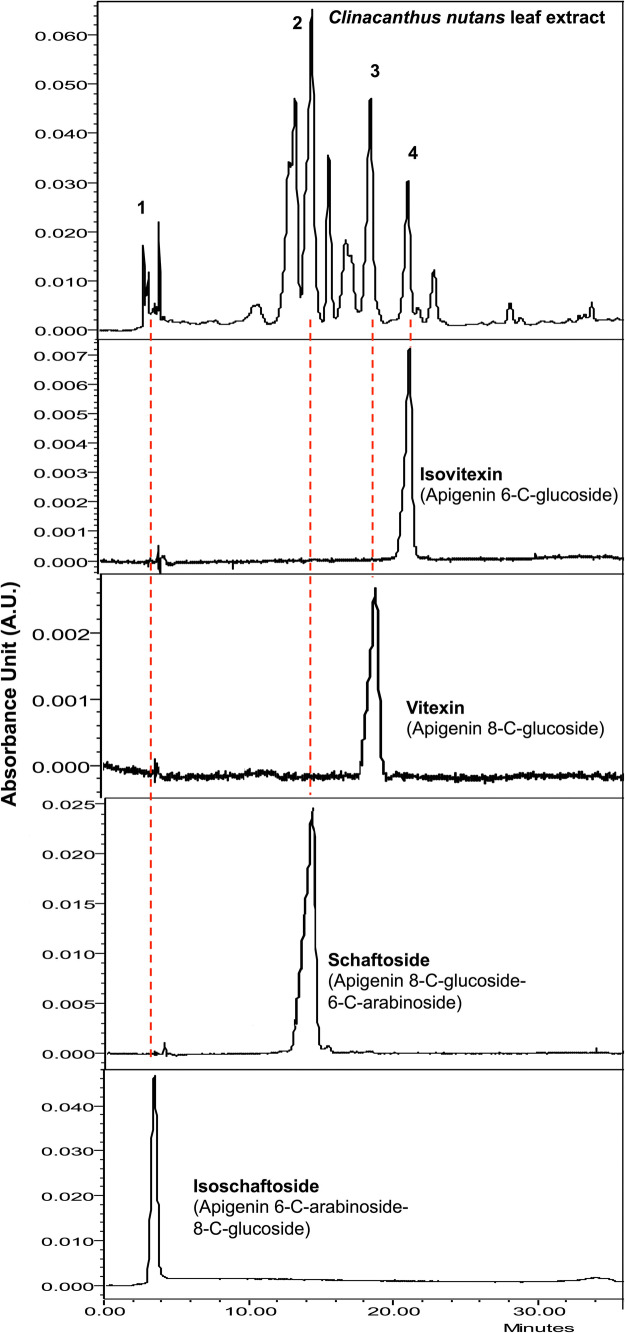

The HPLC analysis showed the CN leaf extract is rich in mainly three apigenin-C-glycosides (Fig. 1), namely: schaftosides (Rt 13.0 and 14.0 min with a saddle in between); vitexin (Rt 18.0 min); and isovitexin (Rt 20.0 min). A low amount of isoschaftoside (retention time Rt 4.0 min) was also detected as the fourth apigenin-C-glycoside.

Fig. 1.

HPLC Chemical fingerprint of Clinacanthus nutans leaf extract identified apigenin C-glycosides, using retention times of reference compounds (1) isoschaftoside, (2) schaftoside, (3) vitexin and (4) isovitexin

The average composition of shaftoside, vitexin, and isovitexin in the extract was 10.0, 1.0, and 0.45 mmol/g, respectively, as in previous reports [13]. The total flavonoids content of the extract was about 0.50 ± 0.03 mg Apigenin equivalent (AE) /g extract [18]. Additionally, flavonoids content varies with the weather and extraction technique. The daily dose was thus estimated based on the average CN flavonoids content reported by others [13, 18]. Hence the estimated daily flavonoid doses of the experimental groups were equivalent to 0.1 mg AE/kg and 0.2 mg AE/kg body weight as compared to 5 mg/kg for Diclofenac.

Animal study for postmenopausal osteoporotic-osteoarthritis

Here, the bilateral ovariectomized rats induced postmenopausal osteoporosis, caused by austere estrogen deficiency, apparent from the significant tibial metaphysis bone loss, 14 days post-ovariectomy. The MIA injection further aggravated articular cartilage degeneration by interrupting chondrocyte metabolism, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase glycolysis, triggering synovial fluid increase and inflammation, subchondral bone sclerosis /remodeling, osteophyte formation and inducing chondrocyte death, similar to human OA [19].

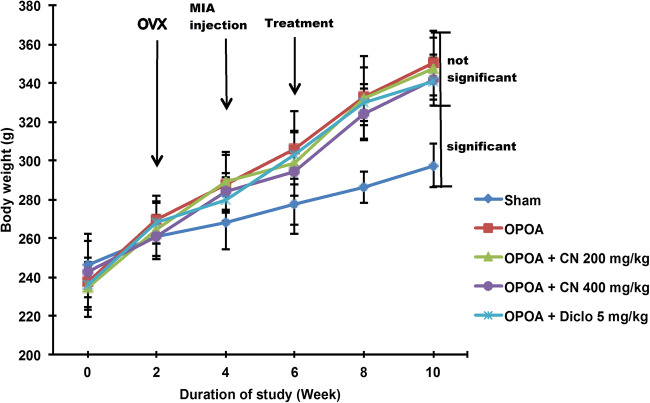

All rats body weights increased during the experiment (Fig. 2), with the increase being significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the ovariectomized (OVX) groups compared to sham group, from the second week onwards, even after osteoarthritis (OA) induction at week 4. This excess body weight increase is characteristic of estrogen deficiency and mild chronic oxidative-stressed/inflammatory conditions. Both CN and Diclofenac treatments did not significantly affect body weight gains and showed no observable toxicity.

Fig. 2.

The body weight changes of different groups of rats at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 weeks. [Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). n.s. = not significant between groups and sig. = significant between groups, p < 0.05]

Macroscopic and microscopic cartilage evaluation

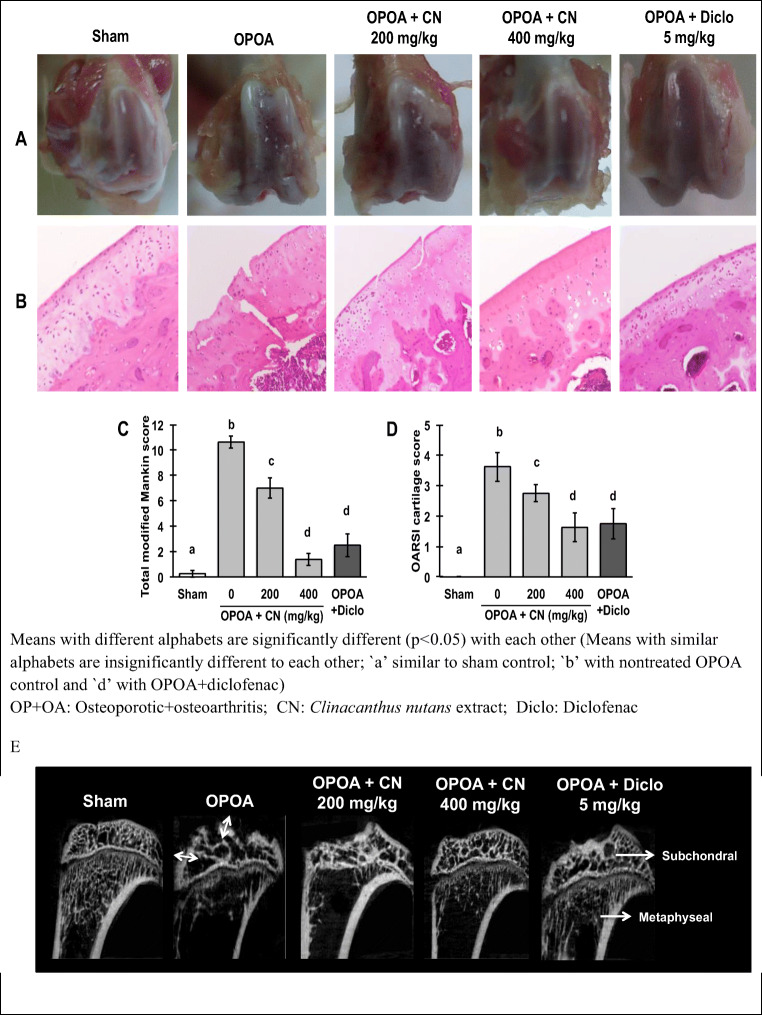

The macroscopic images of the knees of the osteoporotic-osteoarthritis cartilages displayed rough surface, local ulceration, severe articular cartilage surface cleft and matrix loss unlike the glistening, smooth healthy articular cartilage surface of sham control rats (Fig. 3a). All treatments with the extracts and diclofenac attenuated these articular cartilage damages as compared with the non-treated osteoporotic-osteoarthritis control. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections confirmed the gross features, general cartilage morphology, structural and cellular abnormalities (Fig. 3b). The staining confirmed real fissures and not artifacts as the matrix loss at each fissures had reduced dye uptake and was heterogeneous. The modified Mankin and OARSI cartilage scoring systems, showed severe OA lesions in the non-treated osteoporotic-osteoarthritis group which were significantly (p < 0.05) reduced in all CN extracts and diclofenac treatment groups (Fig. 3c and d). Apigenin were reported to prevent cartilage lesions in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid inflammatory arthritis [20] and osteoporosis rat models [21], and this study confirmed it under osteoporotic-osteoarthritis conditions.

Fig. 3.

Macroscopic and microscopic evaluation of the right articular cartilage in osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats with and without treatments with Clinacanthus nutans leaf extract. a Glistening smooth cartilage surfaces of sham rats and rough eroded surface of non-treated osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats. Treatments with CN extracts and diclofenac reduced the Cartilage erosions. b General morphology sections of the right femoral cartilages stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (magnification 42×), showing extensive cartilage fibrillation in the nontreated osteoporotic-osteoarthritis cartilage, c, d treatment with CN extracts and diclofenac decreased the extent of cartilage damage. The cartilage lesions were graded on scale of 0–13 using the modified Mankin scoring system and scale of 0–5 using the OARSI cartilage scoring system of rat model. e Representative micro-CT images of tibial bone in osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats with and without Clinacanthus nutans leaf extract treatments. [Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4). The different letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05)]

Histomorphometric analysis of bone

The representative micro-CT images of the rats’ tibial subchondral and metaphyseal regions (Fig. 3e) demonstrated subchondral bone lesions (double white arrows depicted subchondral bone plate thickening) in non-treated osteoporotic-osteoarthritis group, while treatment with CN leaf extracts and diclofenac mitigated these lesions and bone plate thickening. The underlying metaphyseal region depicted massive trabecular bone loss in the non-treated osteoporotic-osteoarthritis group, and treatments with high dose of CN leaf extract (400 mg/kg) or diclofenac mitigated the trabecular bone loss at the metaphyseal region.

The histomorphometric analysis (Fig. 4), showed an osteoporotic trend in both the subchondral and metaphyseal regions. The osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats had significantly (p < 0.05) lower bone volume fractions (BV/TV - volume of mineralized bone per unit volume of the sample), trabecular numbers (Tb.N), and trabecular separations (Tb.Sp) than normal rats.

Fig. 4.

The Bone histomorphometric analysis of subchondral and metaphyseal regions (microarchitecture of tibial bones) as assessed by micro-CT imaging

The subchondral bone microarchitecture showed changes in the metaphyseal regions indicating its interaction with the overlying osteoarthritic cartilage. The non-treated osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher plate (Pl.Th) and trabecular thicknesses (Tb.Th) at the subchondral region than normal, in addition to the articular bony contour micro-fractures. The 400 mg extract /kg treatment significantly (p < 0.05) reduced the subchondral bone plate thickness (Sb.Pl.Th) and showed no bone focal lesions. Other osteoporotic parameters for both subchondral and metaphyseal bones, namely bone volume fraction (Sb.BV/TV - volume of mineralized bone per unit volume of the sample), trabecular thickness (Sb.Tb.Th), trabecular separation (Sb.Tb.Sp) and trabecular number (Sb.Tb.N) demonstrated significant (p < 0.05) changes in non-treated osteoporotic-osteoarthritis group compared to sham group, without statistical significance between all treatment groups.

Osteoarthritis (OA), progressively damages the joint cartilage, and the underlying adjacent bones (Fig. 4). Articular cartilage fibrillation in OA is caused by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), especially MMP-13 or collagenase 3, that breakdown the extracellular cartilage matrix (ECM), major type II collagen [22], and changes in the normal chondrocyte function towards a catabolic phenotype that favour cartilage loss [23]. The apigenin-C-glycosides rich extract reduced cartilage fibrillation, and dose-dependently suppressed MMP-13, to ameliorate the serum N-propeptide II of type II collagen (PIINP) levels, which is a biomarker for OA correlated joint surface area [24] and articular cartilage ECM degradation, comparable to Diclofenac.

Subchondral bone is a highly active protective tissue for OA joint integrity, and its remodeling rate changes with cartilage destruction and microfractures [25]. Subchondral bone active turnover and thinning occurs during early OA, but slow turnover at the later stage cause it to become thicker [26]. The micro-CT data (Fig. 4) showed subchondral bone plate and trabecular thickening in the osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats, indicating a late OA stage, whereby compensatory mechanisms towards adjacent osteoarthritic cartilages had occurred to support the mechanical functions. The enhanced subchondral bone plate remodeling and trabecular thickening were ameliorated by the apigenin-C-glycosides rich extract. The unilateral OA would eventually develop into a bilateral OA due to the abnormal loading and gait of the weight-bearing knee, for prospective cohort study reported that about 80% of those with unilateral OA developed bilateral disease after 5–12 years [27].

The micro-CT images showed the osteoporotic-osteoarthritis bone, remained osteopenic, with reduced bone volume fraction (BV/TV) and increased trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) particularly at the metaphyseal region. Serum procollagen type I N propeptide (PINP) and osteocalcin, the diagnostic biomarkers for osteoporosis secreted by osteoblasts during bone formation phase of bone remodeling [28, 29], were greatly reduced in osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats and increased by treatment with the apigenin-C-glycosides rich extract or Diclofenac, indicating bone loss mitigation with possible bone formation effects under estrogen deficiency alone or in the presence of OA.

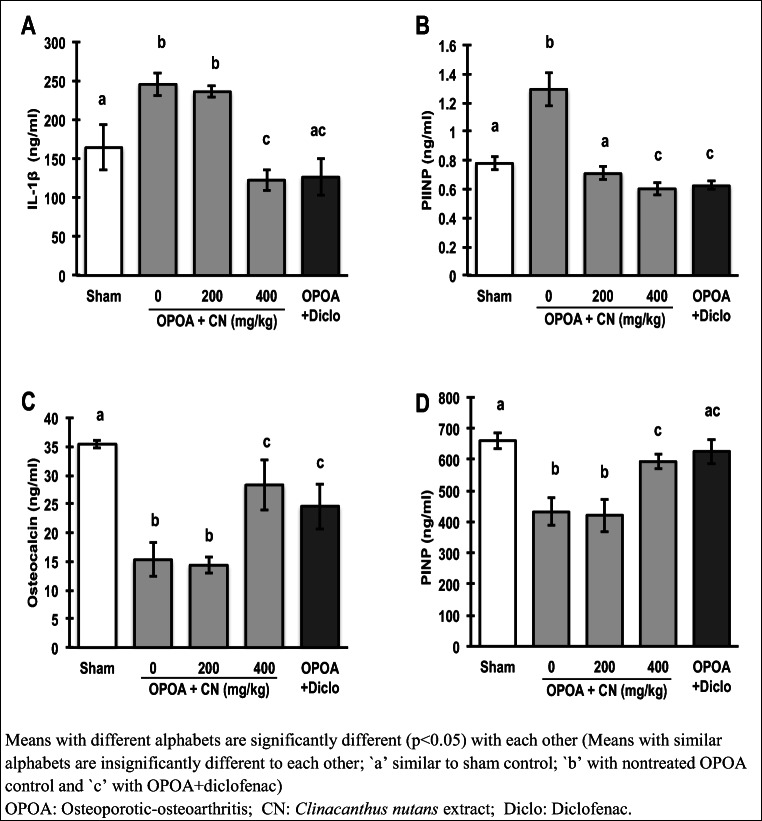

Serum protein biomarkers for inflammation, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis

The profoundly elevated serum pro-inflammatory IL-1β levels in the non-treated osteoporotic-osteoarthritis group (Fig. 5a), were significantly (p < 0.05) suppressed by the 400 mg extract /kg and diclofenac treatments. Apigenin and its derivatives, reportedly reduced diabetic-related inflammation by suppressing COX-2 and NF-κβ [30]; while vitexin and isovitexin, reduced IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α in inflammation-induced mice [31].

Fig. 5.

Effect of Clinacanthus nutans leaf extract on serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine, osteoporosis and osteoarthritis markers evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). a Interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) as pro-inflammatory cytokine, b procollagen type II N-terminal propeptide (PIINP) as osteoarthritis marker, and c osteocalcin and d procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide as osteoporosis markers. Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). The different letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05)

The extract also significantly (p < 0.05) and dose-dependently reduced the elevated osteoarthritis biomarker, procollagen type II N-terminal propeptide (PIINP) levels, in the osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats. Conversely, the bone formation phase biomarkers of bone remodeling, osteocalcin and procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (PINP), that were considerably decreased in osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats, were significantly (p < 0.05) raised by the 400 mg /kg dose, or diclofenac.

Effects on mRNA expressions

The significantly (p < 0.05) upregulated pro-inflammatory nuclear-factor kappa-beta (NF-κβ), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and interleukin-1-beta (IL-1β), and matrix proteolytic enzyme; matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) mRNA expressions in the non-treated osteoporotic-osteoarthritis group (Fig. 6), were dose-dependently and significantly (p < 0.05) suppressed by both CN and diclofenac treatments.

Fig. 6.

Effect of Clinacanthus nutans leaf extract on pro-inflammatory and proteolytic enzyme mRNA expressions. a Nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κβ), b cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) and c interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) as pro-inflammatory markers. d Matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP-13) as matrix proteolytic enzyme marker. Data were expressed as mean fold change compared to healthy sham rats

Pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, COX, IL-1β and IL-6, aggravate the pathogenesis of both OP and OA by increasing the metalloproteinases and aggrecanases that degrades the collagen and proteoglycan matrix, while disturbing the chondrocytes normal matrix anabolism and remodeling activities [32]. These pro-inflammatory cytokines up-regulate osteoclasts and inhibit osteoblast activities in the presence of RANK ligand (RANKL), eventually causing a net bone loss when the resorptive lacuna are not filled by new matrix [33, 34].

Here, the increase in IL-1β serum level, and the up-regulated NF-κβ, IL-1β and COX-2 expressions in the osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rats, were significantly suppressed by both Diclofenac and the apigenin-C-glycosides rich CN extract to near normal levels, indicating potent anti-inflammatory actions. The NF-κβ signaling pathways interfere with chondrocytes responses, leading to progressive OA-related ECM damage, MMP release [35], and OP-associated osteoclastogenesis that impaired bone formation [36]. The estrogen receptor deficiency in osteoblast under OP, and chondrocytes phenotype changes under OA, caused NF-κ β elevation in these cells [37, 38]. NF-κβ transcription factors facilitate activation of inflammatory mediators especially IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, PGE2 and COX-2, that consequently produced a positive feedback loop to increase NF-κβ that suppress bone and cartilage cells anabolism in OP and OA [39–41].

Vitexin was previously reportedly to attenuate inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) production through NF-κβ and HIF-Iα pathways inhibition in osteoarthritis models [42, 43]. Schaftoside, inhibited mRNA and protein expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6) in vitro [44]. The isoschaftoside-rich Viola yedoensis inhibited IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 and NF-κβ activation in lipolysaccharide-stimulated inflammation in murine macrophages [45]. The apigenin-C-glycosides rich CN extract, may have interacted synergistically to significantly suppress the NF-κβ pathway in this osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rat model, providing a safe and effective osteoporotic-osteoarthritis management option. Future work could investigate each individual CN apigenin-C-glycoside administration to rank the most potent compounds for osteoporotic-osteoarthritis. The findings may also be corroborated further by clinical intervention studies.

Conclusions

The apigenin-C-glycosides (schaftoside, vitexin, isovitexin and isoschaftoside,) rich Clinacanthus nutans leaf extract attenuated cartilage and bone loss in osteoporotic-osteoarthritis by inhibiting inflammatory and catabolic proteases pathways, comparable with the NSAID diclofenac, the FDA approved benchmark pharmacological treatment for OA and painful inflammatory conditions.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 214 kb)

(PDF 343 kb)

Acknowledgements

Authors would wholeheartedly thank Comparative Medicine and Technology (CoMeT) Unit, Institute of Bioscience, Universiti Putra Malaysia for helping with surgical and injection procedure in animal studies.

Funding information

This work was supported by the Herbal Development Division, Ministry of Agriculture, Malaysia (Grant no. NH1014D052).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Loeser RF, Collins JA, Diekman BO. Ageing and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:412–420. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendrickx G, Boudin E, Van Hul W. A look behind the scenes: the risk and pathogenesis of primary osteoporosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:462–474. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glowacki J, Thornhill TS. Osteoporosis and Osteopenia in Patients with Osteoarthritis. Orthop Rheumatol. 2016;2:1–5. doi: 10.19080/OROAJ.2016.02.555590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan MY, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Bone mineral density and association of osteoarthritis with fracture risk. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22:1251–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domingues VR, de Campos GC, Plapler PG, de Rezende MU. Prevalence of osteoporosis in patients awaiting total hip arthroplasty. Acta Ortop Bras. 2015;23:34–37. doi: 10.1590/1413-78522015230100981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright NC, Lisse JR, Walitt BT, Eaton CB, Chen Z, Nabel E, et al. Arthritis increases the risk for fractures - results from the women’s health initiative. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1680–1688. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrera VLM, Bagamasbad P, Decano JL, Ruiz-Opazo N. AVR/NAVR deficiency lowers blood pressure and differentially affects urinary concentrating ability, cognition, and anxiety-like behavior in male and female mice. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43:32–42. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00154.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, Abramson S, Arber N, Baron JA, et al. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382:769–779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60900-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geusens P, Emans PJ, De Jong JJA, Van Den Bergh J. NSAIDs and fracture healing. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25:524–531. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32836200b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zulkipli IN, Rajabalaya R, Idris A, Sulaiman NA, David SR. Clinacanthus nutans: a review on ethnomedicinal uses, chemical constituents and pharmacological properties. Pharm Biol. 2017. 10.1080/13880209.2017.1288749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Farsi E, Esmailli K, Shafaei A, Moradi Khaniabadi P, Al Hindi B, Khadeer Ahamed MB, et al. Mutagenicity and preclinical safety assessment of the aqueous extract of Clinacanthus nutans leaves. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2016. 10.3109/01480545.2016.1157810. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Abdul Rahim MH, Zakaria ZA, Mohd Sani MH, Omar MH, Yakob Y, Cheema MS, et al. Methanolic extract of clinacanthus nutans exerts antinociceptive activity via the opioid/nitric oxide-mediated, but cGMP-independent, pathways. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med. 2016. 10.1155/2016/1494981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Chelyn JL, Omar MH, Mohd Yousof NSA, Ranggasamy R, Wasiman MI, Ismail Z. Analysis of flavone C-glycosides in the leaves of Clinacanthus nutans (Burm. F.) Lindau by HPTLC and HPLC-UV/DAD. Sci World J. 2014;2014:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2014/724267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farsi E, Ahmad M, Hor SY, Ahamed MBK, Yam MF, Asmawi MZ. Standardized extract of Ficus deltoidea stimulates insulin secretion and blocks hepatic glucose production by regulating the expression of glucose-metabolic genes in streptozitocin-induced diabetic rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farsi E, Shafaei A, Hor S, Ahamed M, Yam M, Asmawi M, Ismail Z. Genotoxicity and acute and subchronic toxicity studies of a standardized methanolic extract of Ficus deltoidea leaves. Clinics. 2013;68:865–875. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(06)23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pritzker KPH, Gay S, Jimenez SA, Ostergaard K, Pelletier J-P, Revell PA, Salter D, van den Berg W. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2006;14:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mankin HJ, Dorfman H, Lippiello L, Zarins A. Biochemical and metabolic abnormalities in articular cartilage from osteo-arthritic human hips. II. Correlation of morphology with biochemical and metabolic data. J Bone Jt Surg. 1971;53:523–537. doi: 10.2144/000113917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khoo LW, Audrey Kow S, Lee MT, Tan CP, Shaari K, Tham CL, et al. A comprehensive review on Phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Clinacanthus nutans (Burm.F.) Lindau. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med. 2018;2018:1–39. doi: 10.1155/2018/9276260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barve RA, Minnerly JC, Weiss DJ, Meyer DM, Aguiar DJ, Sullivan PM, Weinrich SL, Head RD. Transcriptional profiling and pathway analysis of monosodium iodoacetate-induced experimental osteoarthritis in rats : relevance to human disease. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15:1190–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park J-S, Kim D-K, Shin H, Lee H-J, Jo H-S, Jeong J-H, Choi YL, Lee CJ, Hwang SC. Apigenin regulates Interleukin-1 β -induced production of matrix metalloproteinase both in the knee joint of rat and in primary cultured articular chondrocytes. Biomol Ther. 2016;24:163–170. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2015.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goto T, Hagiwara K, Shirai N, Yoshida K, Hagiwara H. Apigenin inhibits osteoblastogenesis and osteoclastogenesis and prevents bone loss in ovariectomized mice. Cytotechnology. 2015;67:357–365. doi: 10.1007/s10616-014-9694-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldring MB, Otero M, Plumb DA, Dragomir C, Favero M, El Hachem K, et al. Roles of inflammatory and anabolic cytokines in cartilage metabolism: signals and multiple effectors converge upon MMP-13 regulation in osteoarthritis. Eur Cell Mater. 2011;21:202–220. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v021a16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houard X, Goldring MB, Berenbaum F. Homeostatic mechanisms in articular cartilage and role of inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013. 10.1007/s11926-013-0375-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Lotz M, Martel-Pelletier J, Christiansen C, Brandi M-L, Bruyère O, Chapurlat R, Collette J, Cooper C, Giacovelli G, Kanis JA, Karsdal MA, Kraus V, Lems WF, Meulenbelt I, Pelletier JP, Raynauld JP, Reiter-Niesert S, Rizzoli R, Sandell LJ, van Spil W, Reginster JY. Value of biomarkers in osteoarthritis: current status and perspectives. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1756–1763. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei Y, Bai L. Recent advances in the understanding of molecular mechanisms of cartilage degeneration, synovitis and subchondral bone changes in osteoarthritis. Connect Tissue Res. 2016. 10.1080/03008207.2016.1177036. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Burr DB, Gallant MA. Bone remodelling in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:665–673. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metcalfe AJ, Andersson MLE, Goodfellow R, Thorstensson CA. Is knee osteoarthritis a symmetrical disease? Analysis of a 12 year prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:153. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krege JH, Lane NE, Harris JM, Miller PD. PINP as a biological response marker during teriparatide treatment for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2159–2171. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2646-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh S, Kumar D, Lal AK. Serum osteocalcin as a diagnostic biomarker for primary osteoporosis in women. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015. 10.7860/JCDR/2015/14857.6318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Wang Z-H, Hsu C-C, Lin H-H, Chen J-H. Antidiabetic effects of carassius auratus complex formula in high fat diet combined streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med 2014;2014. 10.1155/2014/628473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Borghi SM, Carvalho TT, Staurengo-Ferrari L, Hohmann MSN, Pinge-Filho P, Casagrande R, Verri WA Jr Vitexin inhibits inflammatory pain in mice by targeting TRPV1, oxidative stress, and cytokines. J Nat Prod. 2013;76:1141–1146. doi: 10.1021/np400222v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapoor M, Martel-Pelletier J, Lajeunesse D, Pelletier J-P, Fahmi H. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:33–42. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clowes JA, Riggs BL, Khosla S. The role of the immune system in the pathophysiology of osteoporosis. Immunol Rev. 2005;208:207–227. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maruyama K, Takada Y, Ray N, Kishimoto Y, Penninger JM, Yasuda H, et al. Receptor activator of NF- B ligand and Osteoprotegerin regulate Proinflammatory cytokine production in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:3799–3805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olivotto E, Otero M, Marcu KB, Goldring MB. Pathophysiology of osteoarthritis: canonical NF-κB/IKKβ-dependent and kinase-independent effects of IKKα in cartilage degradation and chondrocyte differentiation. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000061. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jimi E, Aoki K, Saito H, D’Acquisto F, May MJ, Nakamura I, et al. Selective inhibition of NF-κB blocks osteoclastogenesis and prevents inflammatory bone destruction in vivo. Nat Med 2004. 10.1038/nm1054. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Chang J, Wang Z, Tang E, Fan Z, McCauley L, Franceschi R, Guan K, Krebsbach PH, Wang CY. Inhibition of osteoblastic bone formation by nuclear factor-B. Nat Med. 2009;15:682–689. doi: 10.1038/nm.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcu KB, Otero M, Olivotto E, Borzi RM, Goldring MB. NF-kappaB signaling: multiple angles to target OA. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:599–613. doi: 10.2174/138945010791011938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang J, Wang Z, Tang E, Fan Z, McCauley LK, Franceschi RT, et al. Inhibition of osteoblast functions by IKK/NF-kB in osteoporosis. Nat Med. 2009;15:682. doi: 10.1038/nm.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLean RR. Proinflammatory cytokines and osteoporosis. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2009. 10.1007/s11914-009-0023-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Rigoglou S, Papavassiliou AG. The NFkB signalling pathway in osteoarthritis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:2580–2584. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie CL, Li JL, Xue EX, Dou HC, Lin JT, Chen K, et al. Vitexin alleviates ER-stress-activated apoptosis and the related inflammation in chondrocytes and inhibits the degeneration of cartilage in rats. Food Funct 2018. 10.1039/c8fo01509k. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Yang H, Huang J, Mao Y, Wang L, Li R, Ha C. Vitexin alleviates interleukin-1β-induced inflammatory responses in chondrocytes from osteoarthritis patients: involvement of HIF-1α pathway. Scand J Immunol 2019. 10.1111/sji.12773. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Zhou K, Wu J, Chen J, Zhou Y, Chen X, Wu Q, Xu Y, Tu W, Lou X, Yang G, Jiang S. Schaftoside ameliorates oxygen glucose deprivation-induced inflammation associated with the TLR4/Myd88/Drp1-related mitochondrial fission in BV2 microglia cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2018;139:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeong YH, Oh YC, Cho WK, Shin H, Lee KY, Ma JY. Anti-inflammatory effects of Viola yedoensis and the application of cell extraction methods for investigating bioactive constituents in macrophages. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1142-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 214 kb)

(PDF 343 kb)