Abstract

Background

Despite the advances in the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), complete remission is usually challenging. The interactions between tumor and host cells, in which exosomes (EXs) play critical roles, have been shown to be among the major deteriorative tumor-promoting factors herein. Therefore, any endeavor to beneficially target these EX-mediated interactions could be of high importance.

Objectives

a) To investigate the effects of myeloma EXs on natural killer (NK) cell functions. b) To check whether treatment of myeloma cells with eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) or docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), two polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids with known anti-cancer effects, can modify myeloma EXs in terms of their effects on natural killer functions.

Methods

L363 cells were treated with either EPA or DHA or left untreated and the released EXs (designated as E-EX, D-EX and C-EX, respectively) were used to treat NK cells for functional studies.

Results

Myeloma EXs (C-EXs) significantly reduced NK cytotoxicity against K562 cells (P ≤ 0.05), while the cytotoxicity suppression was significantly lower (P ≤ 0.05) in the (E-EX)- and (D-EX)-treated NK cells compared to the (C-EX)-treated cells. The expression of the activating NK receptor NKG2D and NK degranulation, after treatment with the EXs, were both altered following the same pattern. However, C-EXs could increase IFN-γ production in NK cells (P < 0.01), which was not significantly affected by EPA/DHA treatment. This indicates a dual effect of myeloma EXs on NK cells functions.

Conclusion

Our observations showed that myeloma EXs have both suppressive and stimulatory effects on different NK functions. Treatment of myeloma cells with EPA/DHA can reduce the suppressive effects of myeloma EXs while maintaining their stimulatory effects. These findings, together with the previous findings on the anti-cancer effects of EPA/DHA, provide stronger evidence for the repositioning of the currently existing EPA/DHA supplements to be used in the treatment of MM as an adjuvant treatment.

Graphical abstract

EXs released from L363 (myeloma) cells in their steady state increase IFN-γ production of NK cells, while reduce their cytotoxicity against the K562 cell line (right blue trace). EXs from L363 cells pre-treated with either EPA or DHA are weaker stimulators of IFN-γ production. These EXs also increase NK cytotoxicity and NKG2D expression (left brown trace) compared to the EXs obtained from untreated L363 cells. Based on these findings, myeloma EXs have both suppressive and stimulatory effects on different NK functions depending on the properties of their cells of origin, which can be exploited in the treatment of myeloma.

Keywords: Extracellular vesicle, Cancer, Tumor, Natural killer cell, Exosome, Omega-3

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a prevalent hematological cancer, which despite the advances in the development of anti-myeloma drugs, still remains a fatal disease [1, 2]. The reason for this clinical frustration is the development of drug resistance and refractory disease in many cases, resulting in frequent deadly relapses [3, 4]. The recent years of research has shown that most of the treatment failures associated with MM result from the tumor-supporting role of the microenvironment within the bone marrow (BMM) as well as the secretory profile of malignant cells, which remain unaffected in almost all of the current conventional anti-myeloma therapies [5, 6]. It is now evident that bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) and the malignant plasma cells (MM cells) are the major cell populations, which contribute to the drug resistance, survival and progression of MM [7]. This is mainly done via their secretory components and, to a lower extent, through direct cell-to-cell contact, all of which end up in the transduction of survival signals and the suppression of critical immunosurveillance mechanisms. These findings have provoked a great deal of interest in the field to look for more effective drugs targeting the tumor microenvironment in parallel with the direct targeting of tumor cells.

Exosomes (EXs) are small vesicles (30–100 nm) of endosomal origin, well-known as mediators of inter-cellular communication. These nano-sized vesicles are involved in many physiological functions such as maintaining the cross-talk between the hematopoietic cells and other systems of the body [8], stimulating T cells, antigen transfer to dendritic cells (DC) [9, 10] and homeostasis maintenance via disposal of cellular waste [11]. The involvement of EXs in various pathological processes has been also revealed, which is mainly due to their ability to induce changes in their target cells via different mechanisms [12]. Malignant cells specifically exploit this ability of EXs not only for induction of their signals of survival and the suppression of the anti-tumor immunity [13, 14], but also to imprint their pre-metastatic niche into tissues far from the primary tumor site [15]. MM cells have been shown to produce EXs (MM-EXs), which can affect the anti-myeloma immune response and provide the survival signals required for MM persistence and progression [16, 17].

Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) are two widely studied safe polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) of the omega-3 family for which a vast variety of biological properties including anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer effects have been reported [18–20]. A number of studies have reported their apoptotic effects on several cancer cell lines [21, 22] and revealed that they could be exploited in the treatment of hematological malignancies [23]. However, none of the aforementioned studies have tested the indirect effects of these FAs on cancer microenvironment in relation to the anti-tumor immune response. On the other hand, EPA and DHA have been shown to influence different intracellular secretory pathways [23] as well as the cellular membrane structure and composition [24]. EPA, for instance, was shown to displace proteins from specific membrane domains via altering the composition of lipid rafts [25].

Based on the previous findings that EXs released from tumors including MM cells are critical role players in tumor survival and progression, in the present work we made an effort to explore whether EXs secreted by L363 cells (representing myeloma) can alter the activity of natural killer (NK) cells, which are important role players in MM immunosurveillance. We further studied if EPA/DHA can change the secretion and immunomodulatory functions of MM-derived EXs. Considering the availability of pharmaceutical omega-3 supplements, which contain varying amounts of EPA/DHA, as well as their high safety profile, the efficacy of these fatty acids in the context of myeloma can provide stronger evidence for the repositioning of these preparations to be used in the therapeutic regimen of MM patients.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

EPA (Cat. No. E7006-50MG) and DHA (Cat. No. D2534-100MG) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands). ExoQuick TC ™ Exosome Precipitation Solution and exosome-depleted Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) were both from System Biosciences (Palo Alto, CA, USA). Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit and Brefeldin A Solution (1000X) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, USA). Alpha-modified Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (EMEM) was a product of Merck (New Jersey, USA). Recombinant interleukin 2 (IL-2), Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and 3.9-μm latex beads, surfactant-free aldehyde/sulfate, 4% solids were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The following antibodies were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA): Anti-CD38/FITC (Clone: HIT2), Anti-CD138/PE (Clone: Ml15), Anti-CD81/FITC (Clone: 5A6), Anti-CD63/PE (Clone: H5C6), Anti-CD56/APC (Clone: HCD56), Anti-CD107a/FITC (Clone: H4A3), and Anti-IFN-γ/FITC (Clone: 4S.B3). Annexin V/FITC (Cat. No. 51-65,874X) was also from BioLegend. The isotype controls mouse IgG/FITC and mouse IgG/PE and the viability dye Propidium Iodide (PI) (Cat. No. 51-66211E) were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Anti-CD314/PURE (Clone: 1D11) and Anti-CD16/PE (3G8) were from IMMUNOSTEP, S.L. (Salamanca, Spain). Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS (LDH) was a product of Roche (Basel, Switzerland).

Cell lines and culture conditions

The multiple myeloma cell line L363 was a gift from Tuna Mutis, University Medical Centre Utrecht, The Netherlands. NK-92 and the chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line (K562) were generous gifts from Dr. Leo Koenderman, Utrecht University, The Netherlands. The L363 and K562 cell lines were cultured and maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin and fetal bovine serum (FBS; 15 and 10%, respectively) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The NK-92 cell line required enriched culture conditions which were provided using an alpha-modified EMEM medium without ribonucleosides and deoxyribonucleosides supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.2 mM inositol, 0.02 mM folic acid, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 12.5% FBS, 12.5% horse serum and 100–200 U/ml recombinant IL-2.

EPA/DHA treatment of myeloma cells

We have shown in our previous studies that EPA and DHA exert apoptotic effects on MM cell lines including L363 [26, 27]. Based on these studies, various concentrations of EPA and DHA were tested to find the highest concentration with no apoptotic effects (the highest sub-lethal concentration), which was found to be 12.5 μM. EPA and DHA primary stocks of 2 mM were prepared in ethanol (solvent) and working solutions were subsequently prepared by diluting in the assay medium. L363 cells from parent cultures were washed with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) and resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 15% EX-depleted FBS. In order to collect EXs from L363 cells, these cells were seeded in three T-75 (Corning, USA) culture flasks at a concentration of 3 × 105 and incubated in the presence/absence of EPA/DHA for 72 h. Cells were treated with 12.5 μM EPA or DHA, or remained untreated as the control group (untreated control). The concentration of ethanol was maintained below 0.05% in all the experiments.

EX isolation

After 72 h, the cell suspension of each flask was centrifuged at 1000 x g for 10 min to remove the cells. The supernatants were then collected in sterile 15 mL tubes and centrifuged once again at 3000 x g for 15 min. The precipitates were discarded and the remaining supernatants were passed through a 0.22 μM micropore filter to eliminate any remnant impurities of larger than 220 nm. The obtained supernatants were used for EX isolation as per manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 2 ml of the ExoQuick TC ™ Exosome Precipitation Solution was used per 10 ml of each supernatant. The solution was added and mixed gently. The tubes were placed upright and motionless at 4 °C overnight. After the incubation time, the content of each tube was centrifuged without mixing at 1500 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The same centrifugation step was repeated and the white pellet (EX pellet) was resuspended in 500 μl PBS and stored at −70 °C until the following experiments.

EX characterization and quantification

Protein content quantification

The isolated EXs in each group were quantified based on the protein content using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit. The protein concentrations were then reported as μg/ml for each group. The entire study design is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Illustrated flowchart of the methodology used in the study

Flow cytometric analysis of surface markers

To characterize the isolated EXs by flow cytometry, the method described by Théry C and colleagues was followed [28]. Briefly, the isolated EXs were fixed on latex microbeads of a size that falls within the range of flow cytometry detection (3.9 μM). Anti-CD81/FITC and anti-CD63/PE antibodies were then used for staining and detected by flow cytometry. FITC- and PE-conjugated isotype controls were used to eliminate the fluorescent signals caused by any unspecific binding. To perform the analysis, 5 μg of the isolated EXs in each group as determined by the BCA assay was incubated with 10 μl latex beads at room temperature for 15 min. PBS was added to a final volume of 1000 μl in a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube and the tube was placed on a wheel rotator and incubated at 4 °C overnight. To inactivate any remaining binding sites on the surface of the beads, glycine was added to a final concentration of 100 mM for 30 min at room temperature. The suspension was then centrifuged at 4000 x g rpm for 3 min and the obtained pellet was subjected to 3 consecutive washing steps with 1 ml PBS containing 0.5% BSA. Finally, the pellet was resuspended in an antibody binding solution (1% BSA in PBS) and stained with anti-CD81/FITC and anti-CD63/PE. In each group, 20,000 events were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Transmission Electron Microscopy imaging

The isolated EXs were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). To do this, 2% paraformaldehyde was used to fix the EXs and were then placed on formvar-carbon-coated copper grids. Next, the grids were treated with glutaraldehyde (1%) and washed 3 times. The procedure was completed without any further staining and the digital images were prepared.

Dynamic Light Scattering

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) was used to determine the size distribution of the isolated EXs using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK).

EX treatment of NK cells

NK-92 cells in their log phase of growth were seeded onto 96-well plates (1 × 106 cells/ml) for all the experiments. For this, the NK cells were allocated into the following groups each in triplicate: a group which received EXs from the EPA-treated L363 cells (E-EX), a second group which received 10 μg EX from DHA-treated L363 cells (D-EX), a third group which was treated with EXs obtained from non-treated L363 cells (C-EX) and a final group which remained untreated (Ctrl). NK-92 cells were treated with 10 μg EX/well 24 h prior to all the subsequent experiments.

Viability, apoptosis and proliferation assays

In order to check the viability of NK-92 cells after treatment with EXs, the cells were stained with PI and Annexin V/FITC and then were analyzed by flow cytometry. To investigate whether or not the EXs could induce any changes in the proliferation of NK cells, the CFSE proliferation assay was carried out based on a method described previously [29]. Briefly, the cells were labeled with 6 μg/ml CFSE prior to incubation with EXs and were then washed three times with cold PBS to remove any remaining CFSE. After 24 h, the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of CFSE was determined by flow cytometry to determine the proliferation cycles.

Functional assessment

NK cell cytotoxicity assay

To check the cytotoxic function of the NK cells, a co-culture system with the K562 cell line was used where the NK-92 cells were the effector (E) cells and the K562 cells served as target (T) cells. In order to determine the best E: T ratio, co-cultures were established at different E: T ratios of 12.5:1, 25:1 and 50:1 among which the number of target cells was maintained at 5000 cells/well. The ratio of 12.5:1 was finally selected and used in all the subsequent experiments. To perform the cytotoxicity assay, 62.5 × 103 NK cells activated with 100 IU/ml IL-2, were seeded in each well. After 24 h pre-treatment of the cells with 10 μg EX in different groups (Ctrl, C-EX, E-EX, and D-EX), the target cells previously labeled with CFSE were added to each well. The cells were then spun at 100 g for 1 min to increase cell-to cell contact and were then incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. Following the incubation time, the cells were stained with PI and subjected to flow cytometric analysis to determine the percentage of killed target cells (CFSE and PI double positive cells) as described earlier [30, 31]. The obtained percentages were finally used and the specific cytotoxic activity of each group was determined using the following formula:

In some experiments, after the 4 h incubation time, the percentage of cell lysis was determined by measuring the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and the obtained ODs were used in the formula to calculate the specific cytotoxic activity.

NK cell degranulation assay, CD314 expression, and IFN-γ production

Degranulation of the NK-92 cells was determined using the lysosomal-associated protein CD107a [32]. Surface expression of CD107a (normally present on the lipid bilayer of lytic granules), corresponds with the extent of NK degranulation. The expression of CD107a was detected using a FITC-conjugated anti-CD107a antibody as described in [32]. To determine the possible involvement of NKG2D (CD314) in the cytotoxicity changes of NK cells, the surface expression of CD314 was also studied by flow cytometry using an anti-CD314 antibody. The NK cells were activated by either 100 IU/ml IL-2 or co-culture with K562 cells prior to CD314 analysis. For intracellular IFN-γ measurement, NK-92 cells were seeded in complete NK growth medium supplemented with 20% EX-depleted FBS at 1 × 106/ml and treated with 10 μg EX for 24 h. Brefeldin A was added at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml during the last 5 h to prevent the extracellular release of the cytokine. Finally, intracellular staining was done using an anti-IFN-γ/FITC antibody and the cytokine expression was measured by a four-color flow cytometer (FACS Calibur, BD Biosciences, USA).

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were repeated at least 3 times and the data analysis was done using one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey post-hoc test. All the bars in each figure represent Mean ± SEM. The symbols in all the figures represent the following: # Significantly different compared to the C-EX group (P < 0.05) ## (P < 0.01) ϕ Significantly different compared to the control group (P < 0.01).

Results

Structural, protein content and surface marker characterization of MM EXs in steady state and upon EPA/DHA treatment

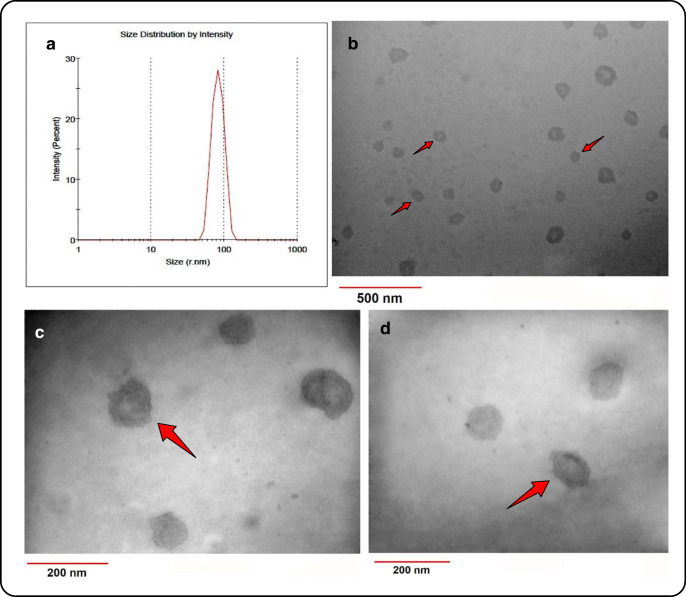

EXs were isolated from the conditioned media of L363 cells under steady state and after 72 h treatment with either EPA or DHA. DLS analysis revealed the presence of particles ranging in diameter from 30 to 110 nm (Fig. 2A), which falls mostly within the diameter range previously reported for EXs [33]. Furthermore, TEM analysis confirmed the ultrastructural characteristics of the isolated nano-sized vesicles as membranous cup-shaped structures (Fig. 2B, C and D), which is similar to previous morphological reports of EXs [34]. Latex bead-assisted fluorescent labeling of the isolated nano-vesicles against the surface markers CD81 and CD63 showed the expression of these markers widely accepted EX markers (Fig. 3A), [35]. Interestingly, EPA/DHA treatment of L363 cells resulted in significantly higher concentrations of EXs recovered, compared to the untreated cells (Fig. 3B). Besides, the percentage of the CD81 and CD83 positive particles were dramatically higher in both the EPA and DHA treated groups (Fig. 3A), supporting the probability that EPA and DHA have increased the release of EXs from MM cells.

Fig. 2.

Structural and size distribution analysis of the isolated MM-EXs. (A) Size distribution by intensity reveals a diameter range of 30 to 110 nm for the isolated EXs. (B, C and D) TEM images show membranous cup-shaped structures, the majority of which possess diameters of less than 100 nm

Fig. 3.

Flow cytometric characterization of EXs and protein content quantification. (A) reveals that the isolated EXs are positive for both CD81 and CD63. EPA and DHA treatment of the MM cells increased the percentage of particles with positive surface markers, which may be due to increased EX release from these cells. (B) BCA protein assay also shows increased protein content of the EXs after treatment with either EPA or DHA. ## Significantly different compared to the C-EX group (P < 0.01)

MM-EXs suppress the cytotoxic function of NK cells

To investigate the effects of MM-EXs on the cytotoxic function of NK cells, NK-92 cells were co-cultured with the human myelogenous leukemia cell line K562 at an E:T ratio of 25:1. In order to discriminate between the effector and targets cells (Fig. 4A), the target cells were pre-labeled with CFSE before co-culture and flow cytometry analysis was done within the CFSE+ population (Fig. 4B) to determine the percentage of killed (PI positive) target cells (Fig. 4C). 24 h treatment with MM-EXs (C-EX) significantly reduced the cytotoxic function of NK cells against K562 cells (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4D). To further confirm the results obtained from flow cytometry, the specific cytotoxicity of NK cells was also investigated based on the release of the LDH enzyme from the lysed cells. Similar results were obtained using the LDH assay, confirming the suppressive effect of MM-EXs on NK cytotoxicity (Fig. 4E). MM-EXs did not induce any apoptotic or viability changes in NK cells when treated with MM-EXs for 24 h as analyzed by flow cytometry using a combination of annexin V and PI. Similarly, CFSE proliferation assay revealed no changes in the proliferation of NK cells following treatment with EXs from either of the groups (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Cytotoxicity studies of NK cells. K562 cells were labeled with CFSE (5 μM) prior to their co-culture with NK-92 cells in each treatment group. (A and B) The CFSE+ population (target K562 cells) were initially gated. (C) After 4 h of co-culture, the cells were stained with PI and then subjected to flow cytometry analysis. In order to calculate the percentage of cytotoxicity, the percentage of PI+ cells were determined within the CFSE+ population, which were deemed as killed targets (%). (D) Shows the percentage of killed target cells as determined by flow cytometry. Each bar represents the Mean ± SEM of three different repeats. (E) Specific cytotoxicity of NK cells in different groups calculated based on the extent of LDH release. Each bar represents the Mean ± SEM of three different experiments. # significantly different compared to the C-EX group (P < 0.05) ## (P < 0.01) ϕ Significantly different compared to the control group (P < 0.01)

DHA-modified MM-EXs do not suppress the cytotoxicity of NK cells

To check whether EPA or DHA treatment could change the suppressive effects of C-EX on NK cytotoxicity, EXs from either of the EPA- or DHA-treated MM cells (E-EX and D-EX, respectively) were used to determine the extent of the cytotoxic activity of NK cells after their 24 h treatment. The results from flow cytometry analysis and LDH measurements indicated that both EPA and DHA treatment reduced the suppressive effects of EXs released from MM cells. D-EX treated NK cells had a normal cytotoxic activity against K562 cells. Although E-EX treated NK cells had increased cytotoxic function compared to the C-EX group, the increase was only significant in the LDH assay (Fig. 4D and E).

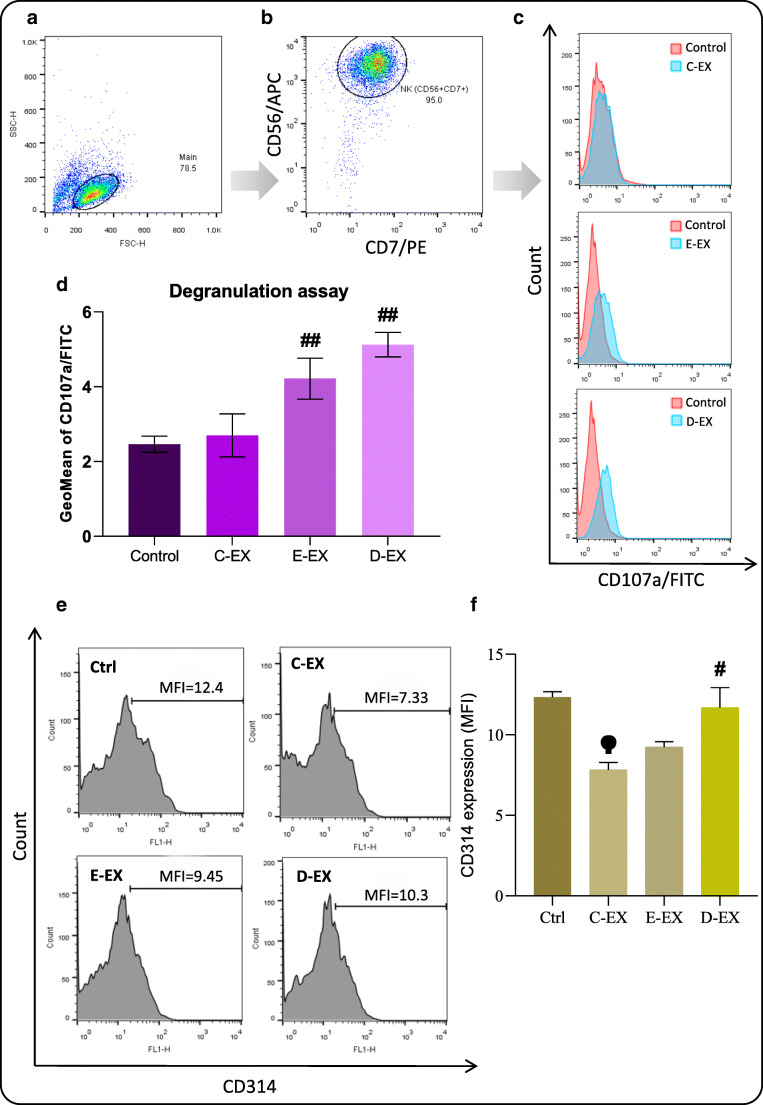

EPA/DHA-modified MM-EXs stimulate NK degranulation

Since degranulation is a major mechanism employed by NK cells to release their cytotoxic molecules such as perforin and granzymes [36], the degranulation marker CD107a was used to check whether C-EX changed degranulation of the NK cells (Fig. 5A, B). The results were partly in parallel with the cytotoxicity assay indicating that although C-EX did not change NK degranulation significantly (Fig. 5C), E-EX and D-EX significantly increased NK degranulation (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Flow cytometry studies of degranulation and CD314 expression. (A and B) NK-92 cells were identified using the markers CD56 and CD7. (C) Surface expression of CD107a as a degranulation marker was then detected using an anti-CD107a antibody. (D) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of three independent experiments were then presented as bars. (E) Flow cytometry histograms of NKG2D expression in each treatment group. (F) C-EXs decreased NKG2D expression of NK-92 cells, while this effect was much weaker in the (E-EX)- and (D-EX)-treated groups. # Significantly different compared to the C-EX group (P < 0.05) ## (P < 0.01) ϕ Significantly different compared to the control group (P < 0.01)

EX-mediated changes in NK cytotoxicity is associated with concomitant changes in the expression levels of the activating receptor NKG2D

To further investigate the observed changes in NK cytotoxicity following treatment with different groups of EXs, we checked the expression of the activating NK receptor CD314 (NKG2D). The flow cytometry results showed that treatment with C-EX significantly decreased surface NKG2D expression of NK cells (Fig. 5E; upper right panel), while this effect was either weak or absent following treatment with E-EX or D-EX (Fig. 5E; lower panels). NKG2D expression in the cells treated with D-EX was significantly higher than that of the C-EX treated cells (P < 0.05), which was almost the same as its expression in the steady state Control (P > 0.05). The data of three different experiments were plotted and depicted as Fig. 5F.

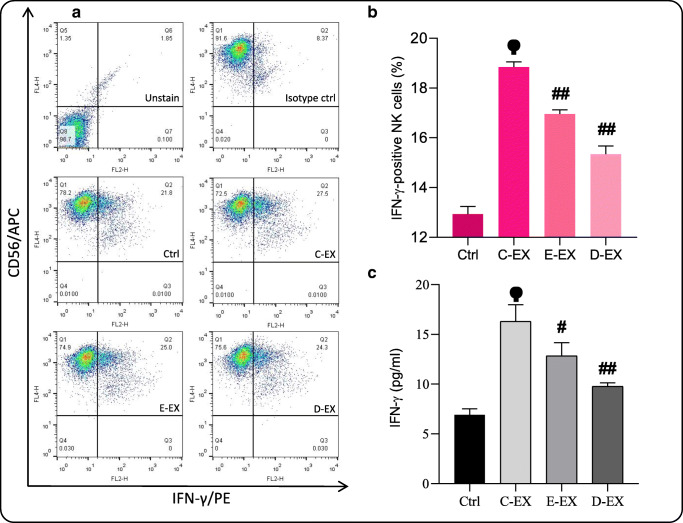

Steady-state and to a lower extent EPA/DHA-modified MM-EXs stimulate IFN-γ production of NK cells

In order to further investigate the effect of steady-state and EPA/DHA-modified EXs on NK cell activity, cytokine production of NK cells was studied. To determine the percentage of IFN-γ positive NK cells, intracellular staining of NK cells was performed using a fluorescent-conjugated anti-human IFN-γ antibody (Fig. 6A). A large increase in the number of IFN-γ positive cells after treatment with C-EX (P < 0.01) was observed (Fig. 6B). Following E-EX and D-EX treatment of the cells, the increase in IFN-γ simulation was significantly lower as compared to the C-EX group (P < 0.01). Next, we measured the concentration of secreted IFN-γ in the supernatants of each group by ELISA. The results were completely in parallel with the flow cytometry results for intracellular IFN-γ, indicating that C-EX and to lower extents E- and D-EX could increase the release of IFN-γ from NK cells (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

IFN-γ production and release by NK-92 cells. (A and B) The percentage of IFN-γ positive NK cells was determined in each group following the intra-cellular staining. (C) The cytokine release of NK cells was then measured using ELISA. Based on the results, C-EX strongly stimulated IFN-γ production of NK cells. E-EX and D-EX also stimulated IFN-γ production, however the effect was not as pronounced as that of C-EX. # Significantly different compared to the C-EX group (P < 0.05) ## (P < 0.01) ϕ Significantly different compared to the control group (P < 0.01)

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the effects of MM-EXs on the activity of NK cells, the major type of immune cells that infer immunity against MM. We initially showed that the L363 cells are capable of producing EXs, which was shown through the identification of the EX surface markers CD81 and CD63 by flow cytometry. Using DLS, we then confirmed that the diameters of the isolated particles were within the range previously reported for EXs. Although there are several studies reporting the isolation of EXs from the sera of MM patients or other cells within the BMM of MM patients [37, 38], there are only few reports on the isolation of EXs exclusively from MM cell lines [39]. We provide evidence that both EPA and DHA at concentrations as low as 12.5 μM, increase the protein content of EXs and also increase the percentage of isolated EXs with positive surface markers. These findings are in parallel with the results of a previous work by Hannafon et al. who showed that DHA can increase the release of EXs from the two breast cancer cell lines MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 [40].

EXs, due to their membranous vesicular structure, which enables them to carry a variety of bioactive molecules both on their surface and within their interior, play an important role in immunity regulation [41, 42]. Moreover, their nano-sized diameter allows them to penetrate almost any cellular compartment throughout the whole body even the most protected sites like the blood brain barrier (BBB) [43, 44]. Tumor cells particularly exploit these characteristics of EXs via producing higher amounts of these nano-sized particles, generally known as tumor-derived EXs (TEX) [12]. A great deal of evidence suggests that TEXs act in favor of tumor survival and progression via suppressing different compartments of the immune system, promoting the required niche for metastasis, stimulating angiogenesis, and the induction of drug resistance [45–47]. This is while a smaller proportion of studies have shown different extents of immunostimulation, which give rise to the notion that besides the deteriorative effects of TEXs, they may also -in part- promote immunosurveillance against tumors [39, 48]. In the case of MM, a number of studies highlight the emerging role of EXs as one of the main culprits behind MM pathogenesis especially in the BMM [49, 50].

Here, we showed that MM-EXs (C-EXs) can suppress the cytotoxic activity of NK cells against K562 cells, while they do not significantly affect the surface exposure of CD107a as a marker of cell degranulation. This indicates a suppressive role for MM-EXs on NK-mediated immunity. On the contrary, treatment of NK cells with MM-EXs caused a dramatic increase in their IFN-γ production and release. These results are in accordance with the results of a previous study, which showed that IFN-γ treatment of K562 cells can inhibit NK cell cytotoxicity and decrease the susceptibility of K562 cells to NK-mediated lysis [51]. On such a basis, it can be postulated that the increased amounts of IFN-γ produced by NK cells as a result of their treatment with MM-EX, has affected the target K562 cells and reduced their susceptibility to be lysed by NK cells. Considering the fact that production of cytokines by NK cells, specifically IFN-γ, is an important tool in governing anti-MM immunity, it can be postulated that MM-EXs in their steady-state serve as a double-edged sword and may affect the NK-mediated immunity in different ways. In agreement with our findings, Vulpis et al. showed that the treatment of primary NK cells with EXs isolated from the sera of MM patients also stimulated degranulation and increased their IFN-γ production [39]. However, they did not observe any effects of their isolated EXs on NK cytotoxicity, which may be due to differences between patients and the MM cell line, as EX-mediated effects can be highly cell-specific [52] and may also differ greatly among patients [53].

Interestingly, our data showed that the suppressive effect of EXs on NK cytotoxicity was significantly lower when NK cells were treated with E-EXs (EXs derived from EPA-treated MM cells). NK cells treated with D-EXs (EXs derived from DHA-treated MM cells) had almost the same cytotoxic function as the untreated NK cells, indicating that DHA treatment can greatly inhibit the cytotoxicity suppression of NK cells mediated by MM-EXs. Notably, both E-EXs and D-EXs could increase NK degranulation while steady-state EXs did not have such an effect. This is while, NK cells after treatment with either E-EXs or D-EXs, produced smaller amounts of IFN-γ compared to the NK cells treated with steady-state EXs. However, the amounts of IFN-γ produced by the (E-EX)- or (D-EX)-treated NK cells was still significantly higher than that of control NK cells that did not receive any EXs (untreated control). These findings altogether show that treatment of MM cells with either EPA or DHA can not only inhibit the suppressive effects of MM-EXs, but also they can strongly trigger some aspects of NK function. These results are in line with the findings of most studies, which have revealed immunosuppressive effects for TEX rather than immunostimulatory effects [48].

NK cell activation is dependent upon the balance between the signals from the stimulatory and the inhibitory receptors on its surface [54]. NKG2D is among the activation receptors, which mainly recognizes MICA and MICB as its ligands [55]. However, a few studies suggest that the binding of these ligands to NKG2D does not necessarily result in NK activation and may even cause its inactivation. These findings were subsequent to the observations that MICA and MICB, when present on EXs, acted differently compared to when they were presented to NKG2D on the cell membrane itself. Surprisingly, it has been shown that exosomal MICA and MICB does not activate NKG2D, but instead, causes downregulation of this receptor on NK cells [56]. Accordingly, we observed that C-EXs significantly decreased the expression of NKG2D, while NKG2D expression was higher in the E-EX and D-EX groups. In the case of (D-EX)-treated NK cells, NKG2D expression was almost as high as the untreated control. It would be of interest to further study if the presence of EPA and DHA can change the exosomal content of MICA and MICB.

It has been previously shown that EPA and DHA exert their cellular effects via multiple ways such as changing the composition of the cell membrane, producing downstream inflammatory molecules, altering the expression of a variety of genes [23] and activating the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) [57]. The mechanism(s) through which EPA or DHA have caused an increase in EX production of MM cells, may underlie their previously shown ability to increase the activity of neutral sphingomyelinase (nSMase) and ceramide formation [58], which are involved in EX synthesis [59]. Another explanation may be that due to their low cholesterol binding affinities, EPA and DHA could change the cholesterol composition of the cell membrane and thus affect lipid raft formation [24, 25]. This is important since changes in cholesterol content of the cellular membrane can affect EX biogenesis and its release [60]. Nonetheless, these possibilities are only hypothetical and have to be tested in the future studies.

Beside their high safety profile, EPA and DHA have so far shown promising anti-cancer effects in various hematological cancers, which have been reviewed previously [23]. Moreover, there is an adequate deal of clinical data that supports the beneficiary effects of these omega 3 fatty acids in blood cancer patients. For instance, Cvetkovic et al. showed that, compared to healthy individuals, the levels of these two fatty acids were lower in the sera of non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients [61]. The levels of EPA/DHA also correlated inversely with the aggressiveness and severity of the disease [61]. In another study on ALL and AML patients, incorporation of EPA in the diet of these patients resulted in better overall conditions of the patients and prevented their weight loss [62]. With regard to the role of MM-EXs in MM progression, a recent clinical trial (NCT01764880) studied the effects of a heparanase inhibitor (roneparstat) as novel therapy for MM patients [63]. However, to date, there are no clinical studies investigating the direct links between these fatty acids and the overall outcome of MM patients, warranting future clinical studies herein.

Conclusion

In the present study we showed that (i) MM-EXs suppress the cytotoxic function of NK cells; (ii) MM cells treated with either EPA or DHA produce less suppressive exosomes; (iii) NKG2D expression of NK cells changes upon their treatment with EXs in parallel with alterations in their cytotoxic function (iv) MM-EXs dramatically increase IFN-γ production and release of NK cells. In summary, our findings provide new evidence on the immunomodulatory role of MM-EXs and the effectiveness of EPA and DHA in modifying the EX-mediated changes. We showed that MM-derived EXs can suppress the cytotoxic function of NK cells and that treatment with either EPA or DHA can largely eliminate this suppression. Acknowledging the important role of EXs in controlling the tumor microenvironment of MM as an important determinant of disease progression, the use of EPA and DHA as dietary supplements for MM patients may be the subject of future clinical research in the field. This can be done by integrating the currently existing pharmaceutical preparations of EPA and DHA into the therapeutic regimen of MM patients. Finally, further mechanistic studies are warranted to elucidate the precise mechanisms through which MM-EXs exert their immunomodulatory effects and the possible strategies of targeting these mechanisms to achieve therapeutic outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This article has been extracted from the thesis written by Mr. Milad Moloudizargari in School of Medicine Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Registration No: 260). Ethics committee approval ID: IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1397.578.

Author’s contribution

MM carried out all the experiments and prepared the manuscript. FR edited the manuscript. MHA helped in preparing the paper and did the statistical analysis. NM consulted MM during the work. EM supervised and conceived the whole study.

Funding

E. Mortaz was supported by National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD) grant number 977582.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Canella A, et al. The potential diagnostic power of extracellular vesicle analysis for multiple myeloma. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2016;16(3):277–284. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2016.1132627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iaccino E, et al. Monitoring multiple myeloma by idiotype-specific peptide binders of tumor-derived exosomes. Mol Cancer. 2017;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Di Marzo L, et al. Microenvironment drug resistance in multiple myeloma: emerging new players. Oncotarget. 2016;7(37):60698–60711. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang L, Pan L, Xiang B, Zhu H, Wu Y, Chen M, Guan P, Zou X, Valencia CA, Dong B, Li J, Xie L, Ma H, Wang F, Dong T, Shuai X, Niu T, Liu T. Potential role of exosome-associated microRNA panels and in vivo environment to predict drug resistance for patients with multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(21):30876–30891. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soley L, Falank C, Reagan MR. MicroRNA transfer between bone marrow adipose and multiple myeloma cells. Current Osteoporosis Reports. 2017;15(3):162–170. doi: 10.1007/s11914-017-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umezu T, Tadokoro H, Azuma K, Yoshizawa S, Ohyashiki K, Ohyashiki JH. Exosomal miR-135b shed from hypoxic multiple myeloma cells enhances angiogenesis by targeting factor-inhibiting HIF-1. Blood. 2014;124(25):3748–3757. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-576116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moloudizargari M, Asghari MH, Abdollahi M. Modifying exosome release in cancer therapy: how can it help? Pharmacol Res. 2018;134:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Veirman K, et al. Induction of miR-146a by multiple myeloma cells in mesenchymal stromal cells stimulates their pro-tumoral activity. Cancer Lett. 2016;377(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(8):569–579. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfers J, Lozier A, Raposo G, Regnault A, Théry C, Masurier C, Flament C, Pouzieux S, Faure F, Tursz T, Angevin E, Amigorena S, Zitvogel L. Tumor-derived exosomes are a source of shared tumor rejection antigens for CTL cross-priming. Nat Med. 2001;7(3):297–303. doi: 10.1038/85438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanez-Mo, M., et al., (2015) Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles. 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Kosaka N, Yoshioka Y, Tominaga N, Hagiwara K, Katsuda T, Ochiya T. Dark side of the exosome: the role of the exosome in cancer metastasis and targeting the exosome as a strategy for cancer therapy. Future Oncol. 2014;10(4):671–681. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maybruck BT, Pfannenstiel LW, Diaz-Montero M, Gastman BR. Tumor-derived exosomes induce CD8(+) T cell suppressors. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szajnik M, Czystowska M, Szczepanski MJ, Mandapathil M, Whiteside TL. Tumor-derived microvesicles induce, expand and up-regulate biological activities of human regulatory T cells (Treg) PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, Molina H, Kohsaka S, di Giannatale A, Ceder S, Singh S, Williams C, Soplop N, Uryu K, Pharmer L, King T, Bojmar L, Davies AE, Ararso Y, Zhang T, Zhang H, Hernandez J, Weiss JM, Dumont-Cole VD, Kramer K, Wexler LH, Narendran A, Schwartz GK, Healey JH, Sandstrom P, Labori KJ, Kure EH, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, de Sousa M, Kaur S, Jain M, Mallya K, Batra SK, Jarnagin WR, Brady MS, Fodstad O, Muller V, Pantel K, Minn AJ, Bissell MJ, Garcia BA, Kang Y, Rajasekhar VK, Ghajar CM, Matei I, Peinado H, Bromberg J, Lyden D. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527(7578):329–335. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raimondi L, de Luca A, Amodio N, Manno M, Raccosta S, Taverna S, Bellavia D, Naselli F, Fontana S, Schillaci O, Giardino R, Fini M, Tassone P, Santoro A, de Leo G, Giavaresi G, Alessandro R. Involvement of multiple myeloma cell-derived exosomes in osteoclast differentiation. Oncotarget. 2015;6(15):13772–13789. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang JH, et al. Multiple myeloma exosomes establish a favourable bone marrow microenvironment with enhanced angiogenesis and immunosuppression. J Pathol. 2016;239(2):162–173. doi: 10.1002/path.4712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calder PC. Mechanisms of action of (n-3) fatty acids. J Nutr. 2012;142(3):592S–599S. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.155259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghaedi E, Rezaei, N, Mahmoudi, M (2019) Nutrition, Immunity, and Cancer, in Nutrition and Immunity. Springer. p. 209–281.

- 20.Golzari MH, Javanbakht MH, Ghaedi E, Mohammadi H, Djalali M. Effect of Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) supplementation on cardiovascular markers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12(3):411–415. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Betiati Dda S, de Oliveira PF, Camargo Cde Q, Nunes EA, Trindade EB. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on regulatory T cells in hematologic neoplasms. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2013;35(2):119–125. doi: 10.5581/1516-8484.20130033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillis RC, Daley BJ, Enderson BL, Karlstad MD. Eicosapentaenoic acid and gamma-linolenic acid induce apoptosis in HL-60 cells. J Surg Res. 2002;107(1):145–153. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2002.6496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moloudizargari M, et al. Effects of the polyunsaturated fatty acids, EPA and DHA, on hematological malignancies: a systematic review. Oncotarget. 2018;9(14):11858–11875. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan YY, McMurray DN, Ly LH, Chapkin RS. Dietary (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids remodel mouse T-cell lipid rafts. J Nutr. 2003;133(6):1913–1920. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.6.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stulnig TM, Huber J, Leitinger N, Imre EM, Angelisova P, Nowotny P, Waldhausl W. Polyunsaturated eicosapentaenoic acid displaces proteins from membrane rafts by altering raft lipid composition. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(40):37335–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdi J, Garssen J, Faber J, Redegeld FA. Omega-3 fatty acids, EPA and DHA induce apoptosis and enhance drug sensitivity in multiple myeloma cells but not in normal peripheral mononuclear cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2014;25(12):1254–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mortaz E et al., (2019) EPA and DHA have selective toxicity for PBMCs from multiple myeloma patients in a partly caspase-dependent manner. Clin Nutr. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Thery C et al., (2006) Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. Chapter 3: p. Unit 3 22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Good Z, Borges L, Vivanco Gonzalez N, Sahaf B, Samusik N, Tibshirani R, Nolan GP, Bendall SC. Proliferation tracing with single-cell mass cytometry optimizes generation of stem cell memory-like T cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(3):259–266. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HR et al. (2017) Expansion of cytotoxic natural killer cells using irradiated autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells and anti-CD16 antibody. Sci Rep. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Zhang H, Xie Y, Li W, Chibbar R, Xiong S, Xiang J. CD4(+) T cell-released exosomes inhibit CD8(+) cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses and antitumor immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8(1):23–30. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorenzo-Herrero S, Sordo-Bahamonde C, Gonzalez S, López-Soto A. CD107a degranulation assay to evaluate immune cell antitumor activity. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1884:119–130. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8885-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strack R. Improved exosome detection. Nat Methods. 2019;16(4):286–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Du YM, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes promote immunosuppression of regulatory T cells in asthma. Exp Cell Res. 2018;363(1):114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng N et al. (2019) Recent advances in biosensors for detecting Cancer-derived Exosomes. Trends Biotechnol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Morcos M et al. (2019) Perforin inhibition blocks NK-mediated in vitro killing of human lung epithelial cells in COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 199.

- 37.Arendt BK, Walters DK, Wu X, Tschumper RC, Huddleston PM, Henderson KJ, Dispenzieri A, Jelinek DF. Increased expression of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (CD147) in multiple myeloma: role in regulation of myeloma cell proliferation. Leukemia. 2012;26(10):2286–2296. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arendt BK, Walters DK, Wu X, Tschumper RC, Jelinek DF. Multiple myeloma cell-derived microvesicles are enriched in CD147 expression and enhance tumor cell proliferation. Oncotarget. 2014;5(14):5686–5699. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vulpis E, Cecere F, Molfetta R, Soriani A, Fionda C, Peruzzi G, Caracciolo G, Palchetti S, Masuelli L, Simonelli L, D'Oro U, Abruzzese MP, Petrucci MT, Ricciardi MR, Paolini R, Cippitelli M, Santoni A, Zingoni A. Genotoxic stress modulates the release of exosomes from multiple myeloma cells capable of activating NK cell cytokine production: role of HSP70/TLR2/NF-kB axis. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(3):e1279372. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1279372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hannafon BN, Carpenter KJ, Berry WL, Janknecht R, Dooley WC, Ding WQ. Exosome-mediated microRNA signaling from breast cancer cells is altered by the anti-angiogenesis agent docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) Mol Cancer. 2015;14:133. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0400-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anel A et al. (2019) Role of Exosomes in the Regulation of T-cell Mediated Immune Responses and in Autoimmune Disease. Cells. 8(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.LeBleu VS, Kalluri R. Exosomes exercise inhibition of anti-tumor immunity during chemotherapy. Immunity. 2019;50(3):547–549. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Offen D, Perets N, Guo S, Betzer O, Popovtzer R, Ben-Shaul S, Sheinin A, Michaelevski I, Levenberg S. Exosomes loaded with Pten Sirna leads to functional recovery after complete transection of the spinal cord by specifically targeting the damaged area. Cytotherapy. 2019;21(5):E7–E8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng M, Huang M, Ma X, Chen H, Gao X. Harnessing Exosomes for the development of brain drug delivery systems. Bioconjug Chem. 2019;30(4):994–1005. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.9b00085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, et al. Multiple myeloma exosomes establish a favourable bone marrow microenvironment with enhanced angiogenesis and immunosuppression. J Pathol. 2016;239(2):162–173. doi: 10.1002/path.4712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Canella A, Harshman SW, Radomska HS, Freitas MA, Pichiorri F. The potential diagnostic power of extracellular vesicle analysis for multiple myeloma. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2016;16(3):277–284. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2016.1132627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyiadzis M, Whiteside TL. The emerging roles of tumor-derived exosomes in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2017;31(6):1259–1268. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bobrie A, Colombo M, Raposo G, Théry C. Exosome secretion: molecular mechanisms and roles in immune responses. Traffic. 2011;12(12):1659–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moloudizargari M et al. (2019) The emerging role of exosomes in multiple myeloma. Blood Rev: p. 100595. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Moloudizargari M, Asghari MH, Mortaz E. Inhibiting exosomal MIC-A and MIC-B shedding of cancer cells to overcome immune escape: new insight of approved drugs. Daru. 2019;27:879–884. doi: 10.1007/s40199-019-00295-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gronberg A, et al. IFN-gamma treatment of K562 cells inhibits natural killer cell triggering and decreases the susceptibility to lysis by cytoplasmic granules from large granular lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1988;140(12):4397–4402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phuyal S, et al. Regulation of exosome release by glycosphingolipids and flotillins. FEBS J. 2014;281(9):2214–2227. doi: 10.1111/febs.12775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sierich H and Eiermann T (2013) Comparing individual NK cell activity in vitro. Curr Protoc Immunol. Chapter 14: p. Unit 14 32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Gillgrass A, Ashkar A. Stimulating natural killer cells to protect against cancer: recent developments. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7(3):367–382. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferrari de Andrade, L., et al., Antibody-mediated inhibition of MICA and MICB shedding promotes NK cell-driven tumor immunity. Science, 2018. 359(6383): p. 1537–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Labani-Motlagh A, et al. Differential expression of ligands for NKG2D and DNAM-1 receptors by epithelial ovarian cancer-derived exosomes and its influence on NK cell cytotoxicity. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(4):5455–5466. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4313-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DeClercq V, d'Eon B, McLeod RS. Fatty acids increase adiponectin secretion through both classical and exosome pathways. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2015;1851(9):1123–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu M, Harvey KA, Ruzmetov N, Welch ZR, Sech L, Jackson K, Stillwell W, Zaloga GP, Siddiqui RA. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids attenuate breast cancer growth through activation of a neutral sphingomyelinase-mediated pathway. Int J Cancer. 2005;117(3):340–348. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Théry C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(1):9–17. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plebanek MP et al. (2015) Nanoparticle targeting and cholesterol flux through scavenger receptor type B-1 inhibits cellular exosome uptake. Sci Rep. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Cvetkovic Z, et al. Abnormal fatty acid distribution of the serum phospholipids of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2010;89(8):775–782. doi: 10.1007/s00277-010-0904-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bayram I, Erbey F, Celik N, Nelson JL, Tanyeli A. The use of a protein and energy dense Eicosapentaenoic acid containing supplement for malignancy-related weight loss in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(5):571–574. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Galli M, Chatterjee M, Grasso M, Specchia G, Magen H, Einsele H, Celeghini I, Barbieri P, Paoletti D, Pace S, Sanderson RD, Rambaldi A, Nagler A. Phase I study of the heparanase inhibitor roneparstat: an innovative approach for ultiple myeloma therapy. Haematologica. 2018;103(10):e469–e472. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.182865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]