Abstract

During breast cancer bone metastasis, tumor cells interact with bone microenvironment components including inorganic mineral. Bone mineralization is a dynamic process and varies spatiotemporally as a function of cancer-promoting conditions such as age and diet. The functional relationship between skeletal dissemination of tumor cells and bone mineralization, however, is unclear. Standard histological analysis of bone metastasis frequently relies on prior demineralization of bone, while methods that maintain mineral are often harsh and damage fluorophores commonly used to label tumor cells. Here, fluorescent silica nanoparticles (SNPs) are introduced as a robust and versatile labeling strategy to analyze tumor cells within mineralized bone. SNP uptake and labeling efficiency of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells is characterized with cryo-scanning electron microscopy and different tissue processing methods. Using a 3D in vitro model of marrow-containing, mineralized bone as well as an in vivo model of bone metastasis, SNPs are demonstrated to allow visualization of labeled tumor cells in mineralized bone using various imaging modalities including widefield, confocal, and light sheet microscopy. This work suggests that SNPs are valuable tools to analyze tumor cells within mineralized bone using a broad range of bone processing and imaging techniques with the potential to increase understanding of bone metastasis.

Keywords: bone metastasis, bone mineral, bone imaging, silica nanoparticles, breast cancer cell labeling, bone metastasis imaging

Graphical Abstract

Fluorescent silica nanoparticles (SNPs) are introduced as a robust labeling strategy to visualize tumor cells within mineralized bone from in vitro and in vivo studies. SNP labeling efficiency of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells is characterized using a broad range of bone processing and imaging techniques. SNPs are a tool with potential to increase understanding of mineral contributions to bone metastasis.

1. Introduction

Despite advances in the treatment of primary breast cancer, metastasis remains the leading cause of death in breast cancer patients. Specifically, bone is the most frequent site of metastasis, where incurable secondary tumors affect over 80% of patients with advanced disease[1,2] and cause significant morbidity (e.g., osteolysis) and mortality. During metastasis, small numbers of tumor cells originating from the primary site disseminate to bone, where they may assume different fates, including death, dormancy, or growth.[3] However, the factors that drive tumor cell dissemination and metastatic progression in bone must be fully understood in order to interfere with this process therapeutically.

While it is well-recognized that bone-resident cells and marrow including blood vessels are critical regulators of metastatic dissemination and progression,[4–8] the mineralized bone matrix may also play an important role.[9,10] For example, epidemiological studies suggest that changes in mineralization status (e.g., due to osteoporosis and treatment with bone-modifying drugs such as bisphosphonates) correlate with breast cancer progression and metastasis,[11,12] and clinical trials are testing the benefits of bisphosphonates as an adjuvant therapy to prevent bone metastasis.[13] In vitro experimental evidence further indicates that the presence of bone mineral regulates breast cancer cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration by altering tumor cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions.[14–16] Importantly, bone mineral properties such as mineral particle size, arrangement, and crystallinity are not static, but vary spatiotemporally, for example, as a function of anatomical location (e.g., cortical vs. trabecular bone), age, diet, and the presence of a primary tumor.[10,17,18] As breast cancer cells are influenced by changes in bone mineral properties,[19] many questions arise. For example, do tumor cells preferentially disseminate to regions of bone with specific (but still undefined) mineral properties? Does a change in mineralization status or mineral properties initiate a change in cell fate, potentially awakening tumor cells from dormancy? Do mineral- and bone marrow-targeting tumor cells differ in their molecular makeup? In order to answer such questions, tumor cells and bone matrix must be studied simultaneously, which is challenging because at the very early stages of metastasis, cancer cells in bone are rare, appearing as single cells or small clusters of cells that are difficult to detect within the three-dimensional (3D) volume of bone.[20]

Typical in vivo studies of bone metastasis involve systemic (e.g., intracardiac) injection of tumor cells labeled with a bioluminescence-generating enzyme and/or fluorescent protein into mice allowing their location to be tracked over time via whole-body imaging.[21] However, because this is a low-resolution (millimeter-scale) approach, early seeding events cannot be detected. To circumvent these limitations and visualize disseminated cancer cells localized to the skeleton, histological detection of fluorescently labeled cells can be used. While this methodology has revealed that breast cancer cells initially seed the tibial metaphysis,[7,9] it involves processing steps that either depend on prior demineralization of bone and/or damage the fluorescent labels. More specifically, paraffin-embedded sections depend on prior decalcification of the tissue to allow sectioning but enable imaging at cellular-resolution with the option to detect tumor cells by immunostaining. On the other hand, conventional poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)-embedded sections retain mineral, but harsh processing conditions lead to loss of fluorescent protein signal and incompatibility with immunostaining.[22] Moreover, the 2D nature of tissue sections makes rare events difficult to detect. Consequently, there exists an unmet need for robust labeling techniques that are compatible with sample processing steps that (i) maintain the mineralization status of the tissue of interest and (ii) can be used in conjunction with 3D advanced imaging approaches to visualize larger tissue volumes, all the while preserving the fluorescence signal after processing.

Here, our goal was to develop a non-protein-based labeling method using highly fluorescent inorganic nanoparticles to identify cancer cells in mineralized bone without further immunostaining. In contrast to fluorescent proteins, synthetic fluorescent dyes feature more reliable fluorescence because they do not depend on secondary/tertiary structure to produce fluorescent signal.[23] When synthetic dyes are covalently bound inside the silica core of PEGylated core-shell silica nanoparticles (SNPs), photon yield and fluorophore stability can be further improved while preventing dyes from leaching out of the SNPs.[24–29] Such SNPs are bright, biocompatible, stable over long periods of time after manufacture[30] and circulation in vivo,[31,32] and can be synthesized to match the needs of specific applications (targeting moieties, excitation wavelength, etc.).[25,32] In this study, we synthesized SNPs containing positively charged cyanine dyes (i.e., Cy3(+), Cy5(+)) with a size of 20–30 nm to maximize cellular uptake and retention.[33] Using positively charged rather than negatively charged fluorescent dyes previously published for this size range of particles[28] maximizes the number of dyes fully covalently encapsulated in the silica matrix,[34] leading to optimal fluorescence brightness per dye. In this study, we first established a reliable labeling protocol for MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, then verified that SNP-labeled cells can be detected alongside mineral and autofluorescent bone marrow within a 3D in vitro model of bone metastasis. Subsequently, we demonstrated the feasibility of this approach for in vivo studies. Detection of SNP-labeled cancer cells was performed with a combination of 2D and 3D imaging approaches including light sheet microscopy of cleared bones to visualize large tissue volumes. Collectively, this work validates the use of fluorescent SNPs to label tumor cells for early-stage bone metastasis studies focused on simultaneous analysis of tumor cells and bone material.

2. Results

2.1. SNPs label breast cancer cells with greater fluorescence intensity than proteins

In order to facilitate imaging-based detection of SNP-labeled tumor cells, we first optimized the design of SNPs and subsequently tested their uptake by breast cancer cells. More specifically, we synthesized SNPs with covalently bound positively charged cyanine 3 (Cy3(+)) dye (Figure 1A), using a seeded and amino-acid catalyzed growth mechanism leading to high brightness levels and low size dispersity below 40 nm, as reported recently.[34] We chose a size range of 25–30 nm, which has been shown to maximize cellular uptake via endocytosis.[33] Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS, Figure S1), gel permeation chromatography (GPC, Figure S2), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed that SNPs were narrowly dispersed around 25 nm in size, and FCS validated that SNPs exhibited high brightness levels with around 50 dyes per particle (Figure 1B). Additionally, steady-state absorbance and fluorescence measurements demonstrated that the superior brightness of these SNPs is not only attributed to the multiplicity of dyes per particle, but also the enhanced brightness per dye. The latter is a result of the rigid silica matrix, which is known to enhance the radiative rate and lower the non-radiative rate of encapsulated dyes that do not significantly transfer energy amongst each other (Figure S3).[27,29] To test uptake of the SNPs by cancer cells, MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of SNPs (0.01, 0.1, 1 μM) and for increasing periods of time (4, 24, and 48 hours). Results were compared to unlabeled control cells, as well as cells transduced to constitutively express red fluorescent protein (RFP). RFP-labeled cells were included as an example of a typical fluorescent protein-based labeling strategy to track tumor cells in metastasis studies that is not compatible with many bone processing techniques.[22] Flow cytometry suggested that cellular labeling efficiency was greatest with higher SNP concentrations and increased incubation times. Lower SNP concentrations required prolonged incubation times in order to yield cell labeling efficacy similar to that achieved with higher SNP concentrations (Figure 1C). By 24–48 hours, 1 μm SNP-labeled cells were two orders of magnitude brighter than control cells (Figure 1C, D). Compared to RFP cells, the SNP-labeled cell population had a similar mean fluorescence intensity but a narrower fluorescence distribution, suggesting that SNPs may achieve more uniform labeling of heterogeneous cell populations than fluorescent proteins (Figure 1D). To be able to directly compare RFP and SNP-based labeling in subsequent experiments, we moved forward by labeling cells with 1 μm SNPs for 24–48 hours, a protocol that yielded similar brightness as RFP cells (Figure 1C, D).

Figure 1. Silica nanoparticle (SNP) characteristics and cellular uptake.

A) Schematic of cyanine 3 (Cy3(+))-SNPs, showing the chemical structure of the silica matrix with covalently bound Cy3(+). Not shown is the PEG surface layer (only about 1 nm thick). B) Top: Size, brightness, and number of dyes per particle derived from fluorescence correlation spectroscopy data for three individual batches of Cy3(+)-SNPs made. Bottom: Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of SNPs. C) Effect of SNP concentration (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1 μm) on labeling of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells as measured by flow cytometry. Range of mean fluorescence for RFP-expressing cells is represented by the grey area between dotted lines. D) Effect of incubation time (4, 24, 48 hours) on SNP-labeling (1 μm) of cells as quantified by flow cytometry. The 24 hour histogram cannot be seen due to overlap with 48 hour histogram. Unlabeled (Blank) cells and red fluorescent protein (RFP)-expressing cells included as negative and positive controls, respectively. E) Widefield fluorescence (red) and corresponding phase microscopy images of Blank and SNP-labeled cells.

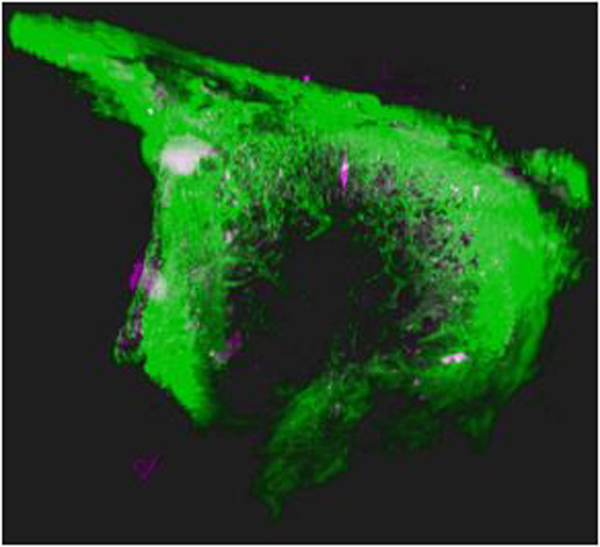

First, we used widefield fluorescence microscopy to confirm that SNP-labeled cells were bright and clearly detectable (Figure 1E). Confocal laser scanning microscopy further verified that SNPs were internalized by the cells rather than adsorbed onto the cell surface (Figure 2A, B and S4A). Interestingly, the SNP signal appeared to be compartmentalized within regions of the cells that were consistent in size with vesicular compartments. In order to compare the intensity of the compartmentalized signals in SNP-labeled cells to those achievable with RFP-labeled cells, we analyzed subcellular regions of interest using confocal microscopy. Both the mean and maximum fluorescence signal-to-noise ratio was substantially increased in SNP-relative to RFP-labeled cells, suggesting that SNP-labeled cells may be more readily detected in complex tissue samples than their RFP-labeled counterparts (Figure 2B and S4B, C). To more accurately determine the localization of SNPs within cells, we imaged high-pressure frozen and freeze-fractured SNP-labeled cells using cryo-scanning electron microscopy (cryo-SEM) and found that SNPs were indeed contained within vesicular structures (~1 μm in diameter) (Figure 2C). The SNPs were enclosed in membrane-delineated compartments and identified as particles consistent in size with synthesized SNPs (Figure S5). The SNPs could also be identified by backscattered electron imaging (Figure 2C), confirming that the particles imaged are indeed SNPs. Taken together, we have designed and synthesized fluorescent SNPs that are taken up by cells and are localized to sub-cellular regions, resulting in a very bright signal that exceeds the signal-to-noise ratio measured for RFP-labeled cells. Moreover, these particles can be identified by imaging techniques that use electrons rather than light, opening up future research directions involving high-resolution imaging techniques.

Figure 2. Analysis of SNP internalization within labeled cancer cells.

A) Orthogonal view of a labeled MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell imaged via confocal microscopy. B) Confocal microscopy images in brightfield and fluorescence (561 laser) of SNP-labeled and RFP-expressing cells acquired using the same imaging parameters. Signal-to-noise ratios were calculated for each label by dividing either mean or maximum intensity of signal within 2 μm square regions of interest (ROIs) by background noise. Boxplots display minimum-to-maximum values. Welch’s unequal variances t-test was used for statistical analysis (n = 110–160 ROIs per label). C) Top: Schematic of sample preparation for cryo-scanning electron microscopy (cryo-SEM) of high pressure frozen and freeze-fractured, SNP-labeled cells. Bottom: Left: Cryo-SEM secondary electron (SE) micrograph of a cell containing an SNP-loaded vesicle. Middle, right: Higher magnification of the SNP-loaded vesicle in white box of left image, imaged with SE (middle) and with backscattered electrons (BSE) (right). The BSE image identifies the SNPs by virtue of the silica being more electron-dense than the other components of the cell. In C), V = vesicle, VM = vesicle membrane, N = nucleus, NM = nuclear membrane, PM = plasma membrane.

2.2. SNP labeling does not affect cell growth, but decreases with cell proliferation

As proliferation of disseminated tumor cells is critical to the development of bone metastasis, we next sought to assess whether SNPs alter the growth kinetics of labeled cells. We confirmed that labeling cells with SNPs did not affect MDA-MB-231 growth over a 7-day period (Figure 3A). Similar to other non-genetic labeling techniques, however, the percentage of positively labeled cells decreased over time, reaching a half-maximum number of labeled cells within 4 days (Figure 3B, C), as measured by vertical gating of flow cytometry data. More detailed flow cytometry analysis suggested that the SNP-labeled cells exhibited a leftward shift and broadening of the fluorescence distribution over time, suggesting that the SNP-labeled cell population became more heterogeneous in fluorescence intensity over time (Figure 3D). By day 4, these changes led to a bimodal distribution consisting of unlabeled cells and cells with residual SNP-based fluorescence (Figure 3D and S6). Hypothesizing that cell division and growth might explain these changes, we fit the SNP signal in cells over time to an exponential decay function and used the resulting time constant to model a cell growth curve (Figure 3E). Indeed, this curve matched the experimentally determined cell growth kinetics, suggesting that loss of SNP signal may be largely due to cell proliferation whereby each mitotic event dilutes the SNPs present in a cell. To further confirm this hypothesis, we treated SNP-labeled cells with mitomycin C (MMC) to block proliferation and measured their fluorescence over time using flow cytometry. The SNP signal was maintained for 4 days following labeling and MMC treatment, with ~90% of cells remaining positively labeled by this time point (Figure 3F). Cells proliferate considerably more slowly in 3D in vivo-like contexts compared to 2D in vitro conditions.[35] Moreover, experiments aimed at localizing disseminated tumor cells in the skeleton involve harvesting bones at early time points following cell injection to keep cell proliferation at a minimum,[7,20] or longer periods (i.e., weeks) for the study of dormant, non-proliferative cancer cells.[36] Therefore, SNP labeling may provide a valuable strategy to detect breast cancer cells in studies focused on early-stage metastasis and/or cancer cell dormancy.

Figure 3. Effect of SNPs on tumor cell growth and labeling efficiency over time.

A) Growth curves of Blank and SNP-labeled cells over time as determined by manual cell counts. Day 0 denotes the endpoint of incubation with SNPs. B) Merged widefield fluorescence (red) and phase microscopy images of SNP-labeled cells at days 1 and 7 acquired using constant imaging parameters. C) Percentage of SNP-labeled cells over a 7-day duration as calculated by vertical gating of flow cytometry data. Dotted line marks the time at which 50% of cells remain positively labeled. D) Flow cytometry histograms collected daily from SNP-labeled cells over 7 days. E) Relative Cy3(+) fluorescence data (experimental, measured by flow cytometry and represented as percentage of day 0 value) fit with an exponential decay curve (theoretical), and an exponential growth curve overlaid with the fold change of cell number (experimental, Figure 3A). F) Percentage of positive Blank and SNP-labeled cells over a 4-day duration in the presence and absence of mitomycin C (MMC) as calculated by vertical gating of flow cytometry data.

2.3. SNP labeling of breast cancer cells is maintained following formalin-fixation

Fixing tissues for subsequent processing often involves harsh chemicals that interfere with the performance of many fluorophores.[37] To ensure that the SNP signal would be retained following fixation, we first measured the effect of common fixatives on the fluorescence of SNPs in solution. The following fixation conditions were tested: (i) 10% formalin, a standard fixative for paraffin embedding; (ii) 10% formalin overnight followed by 70% ethanol, to mimic standard storage conditions for samples prior to paraffin embedding, and (iii) 70% ethanol, which is often used to fix bones for subsequent analysis of bone mineral,[22] as formalin can interfere with measurement of mineral properties.[38] None of these conditions affected the absorbance of SNPs in isolation, and SNPs had increased fluorescence emission when incubated in these various fixatives relative to unfixed control samples (Figure 4A). This suggests that the SNPs themselves are not negatively impacted by fixation. Next, we analyzed whether the different fixation conditions affected the SNP labeling of MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 4B, C). Flow cytometry revealed that fixation with formalin alone, or formalin followed by storage in ethanol, did not affect the number of SNP-labeled cells relative to unfixed conditions. Interestingly, however, ethanol fixation alone significantly reduced the SNP labeling of cells (Figure 4C). Because ethanol did not impact SNPs in solution (Figure 4A), the loss in fluorescence signal was likely related to cell-associated effects of fixation. For example, ethanol can permeabilize cells by dissolving membrane lipids,[39] which could result in loss of SNPs due to diffusion, an effect that may be prevented by prior crosslinking with formalin. Interestingly, an opposite effect was noted for RFP-labeled cells, where ethanol alone maintained or even increased fluorescence, while formalin led to a reduction of fluorescence likely mediated by protein denaturation.[37] The more pronounced decrease in fluorescence for formalin, compared to formalin followed by ethanol, may be due to partial recovery of RFP fluorescence during exposure to ethanol. Based on these results, SNP labeling can be used reliably in tissue samples that undergo formaldehyde-based fixation.

Figure 4. Effects of common bone fixatives on SNP labeling efficiency.

A) Normalized absorbance and fluorescence spectra of SNPs incubated in DI water (Control), 10% neutral buffered formalin (Formalin), 10% neutral buffered formalin followed by 70% ethanol (Formalin → Ethanol), and 70% ethanol (Ethanol). All fixatives are plotted for both absorbance and fluorescence, but some spectra cannot be seen due to overlap with others. B) Flow cytometry histograms of labeled cells before and after fixation with formalin, formalin followed by storage in ethanol (Form/Eth), and ethanol. Some histograms cannot be seen due to overlap with others. Dotted line indicates vertical gating cut-off used to measure fraction of positive cells (cells falling within gray area). C) Percentage of positive SNP-labeled and RFP-expressing cells following fixation relative to unfixed cells, as calculated by vertical gating of flow cytometry data.

2.4. SNP-labeled breast cancer cells can be detected in marrow-containing bone samples in vitro

Further processing of fixed bone samples for metastasis studies frequently involves paraffin embedding of demineralized bone and PMMA embedding of mineralized bone.[21,40] Most of these techniques have limited ability to maintain protein-based fluorescence, and subsequent immunofluorescence-based detection is challenging due to antigen denaturation caused by the harsh processing conditions. Furthermore, bone samples inherently include marrow, which is notorious for autofluorescence.[41] For these reasons, we next tested our ability to detect SNP-labeled cells in marrow-containing bone samples (i) following paraffin and PMMA embedding and (ii) after optical clearing in vitro (Figure 5A). To mimic the complexity of bone for these studies, SNP- or RFP-labeled MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were seeded into bovine trabecular bone scaffolds containing marrow. These scaffolds were prepared by extracting bone biopsies from bovine distal femurs as previously described,[42] resulting in uniformly sized trabecular bone disks (6 mm in diameter and 2 mm in thickness) that contained marrow. To better distinguish mineralized matrix from bone marrow, samples to be subjected to PMMA embedding and optical clearing were additionally labeled with calcein; unfixed samples not subjected to any further processing served as controls.

Figure 5. Imaging of labeled cells within a 3D in vitro bone model following different processing conditions.

A) Schematic of experimental design. Bone scaffolds were prepared by punching out cylinders from bovine femurs and sectioning them to yield disks of uniform thickness containing trabecular bone and marrow. Scaffolds were seeded with MDA-MB-231 cells and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin prior to further processing into paraffin and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) sections or subjecting them to optical clearing using ethyl cinnamate (ECi). B) Representative images of bone scaffolds seeded with either SNP-labeled or RFP-expressing cells when (i, ii) unfixed, or after (iii, iv) paraffin embedding and sectioning, (v, vi) PMMA embedding and sectioning, and (vii, viii) ECi-based optical clearing. Red represents SNP and RFP channels, blue indicates either bone autofluorescence under UV excitation or DAPI (nuclear) staining (as indicated), and green represents bone mineral stained by calcein. Images were acquired using constant parameters within processing condition using confocal microscopy, except for ECi-cleared samples, which were imaged via light sheet microscopy. C) Intensity of line traces (30 μm) taken across SNP-labeled or RFP-expressing cells under each processing condition, normalized to the maximum intensity of SNP-labeled cells. Mean with 95% confidence interval is represented (n = 3–10 cells per processing condition).

Confocal microscopy suggested that SNP-labeled tumor cells in unfixed bone scaffolds were brighter and more easily distinguishable from bone marrow than RFP-labeled cells (Figure 5B, C). Following paraffin embedding and sectioning, both SNP- and RFP-labeled cells were detectable, but similar to unfixed samples, SNP-labeled cells were brighter (Figure 5B, C). In contrast, only SNP-labeled cells were detected in bone scaffolds that had undergone PMMA embedding while RFP-labeled cells, as expected, were not (Figure 5B, C). Bone scaffolds were also optically cleared using ethyl cinnamate, after which they were imaged by light sheet microscopy. This enabled acquisition of larger volumetric data and demonstrated that SNP-labeled cells can also be imaged following optical clearing, whereas RFP-labeled cells are more likely to lose their signal under these conditions (Figure 5B, C). Collectively, our results suggest that SNP-labeled cells can be detected in marrow-containing trabecular bone scaffolds more reliably than RFP-labeled cells.

2.5. SNP-labeled breast cancer cells can be detected in marrow-containing, mineralized bone samples harvested from in vivo experiments

After establishing our ability to detect SNP-labeled tumor cells at relatively high seeding densities in vitro, our next goals were (i) to validate these results with samples collected from in vivo experiments and (ii) to confirm that SNP labeling permits detection of small numbers of disseminated cells. Because Cy5 has reduced spectral overlap with bone marrow autofluorescence compared to Cy3[43] and enables deeper imaging into tissue samples, we synthesized SNPs containing Cy5(+) (Cy5(+)-SNP) for in vivo experiments (Figure S1, S2, S3, and S7). We then labeled MDA-MB-231 cells with Cy5(+)-SNPs and injected them into the left cardiac ventricle of female nude mice, a typical model for studying bone metastasis in mice (Figure 6A and S8).[21] To label mineralizing bone surfaces, mice were injected with calcein 1 day prior to cell injection. After 2 days following cell injection, we harvested the tibiae of these mice and processed the bones similar to the trabecular bone scaffolds, i.e., by paraffin and PMMA embedding as well as optical clearing. Confocal microscopy confirmed that Cy5(+)-SNP-labeled cells could be readily detected in histological sections obtained from both paraffin- and PMMA-embedded tibiae (Figure 6B, C). Furthermore, Cy5(+)-SNP-labeled cells were also detectable by light sheet microscopy of optically cleared non-sectioned bones (Figure 6D, S9, and Supplemental Video 1). Indeed, light sheet microscopy of tibiae from a control mouse not injected with Cy5(+)-SNP labeled cells confirmed that the detected focal signals were derived from labeled tumor cells rather than due to bone marrow autofluorescence (Figure S10). Together, these results confirm that Cy5(+)-SNPs are suitable for labeling breast cancer cells for in vivo early-stage bone metastasis experiments. Moreover, this approach can be used in both demineralized and mineral-containing samples, enabling correlative studies of breast cancer cells as a function of bone microenvironmental conditions including bone marrow and mineralized matrix.

Figure 6. Imaging of labeled cells within bone samples harvested from in vivo experiments and subjected to different processing conditions.

A) Schematic of in vivo experiment in which Cy5(+)-SNP-labeled cancer cells were delivered via intracardiac injection into female nude mice, a typical model of generating intratibial bone metastasis. Mice were injected with calcein one day prior to cell injection, and sacrificed to harvest tibiae two days following cell injection. The proximal tibia was the region of interest for imaging. B) Paraffin-embedded sections of bone imaged via confocal microscopy. C) PMMA-embedded section of bone imaged via confocal microscopy. In B) and C), lower images show higher magnification of areas in white boxes of upper images. D) Ethyl cinnamate (ECi)-cleared bone imaged via light sheet microscopy. 3D rendering of light sheet data with a larger number of labeled cells can be seen in Figure S9 and Supplemental Video 1. For all panels, white arrows indicate presence of labeled cells.

3. Discussion

Interactions between cancer cells, bone marrow, and the mineralized bone matrix may be critical to the initiation and progression of bone metastasis; however, their individual and combined contributions remain elusive due in part to technical challenges associated with imaging disseminated tumor cells within the complex bone microenvironment. Using an in vitro model of marrow-containing bone and in vivo experiments to validate results, we show that SNPs can be used to fluorescently label tumor cells in a manner that is compatible with common bone tissue preparation approaches. Our method of labeling tumor cells enables robust imaging of small numbers of tumor cells under conditions of high autofluorescence from bone marrow and in the presence of mineral. The combination of SNP labeling with in vitro models of bone will enable future advanced studies of bone metastasis while reducing the number of animal experiments.

Current approaches to label cell types of interest often involve the transfection of cells to induce expression of fluorescent proteins. This method provides control over labeling cell types of interest, offers a wide selection of fluorescent protein options, and can be used in both in vitro and in vivo contexts.[23] However, the selection process following transfection can take weeks, and varied transcription/translation efficiency means that fluorescence activated cell-sorting (FACS) may be required to identify the brightest cells within a heterogeneously labeled cell population. It is possible that FACS could unintentionally select for specific cell phenotypes that could skew results. Additionally, as shown in this and earlier studies, these proteins may not remain fluorescent through the harsh processing involved in embedding mineralized bone in PMMA.[22,37] Our results indicate that SNPs represent a robust alternative, as they perform similarly or better than fluorescent proteins, and are more readily compatible with a broader range of imaging and processing approaches, including paraffin and PMMA embedding. Unlike protein-based labels, SNPs are larger and have an electron-dense core enabling detection via electron-based imaging techniques, which may extend their use to high-resolution, multi-modal imaging that does not depend on fluorescence. Indeed, our results also suggest that SNPs have potential as markers for cryo-electron microscopy and cryo-fluorescence microscopy, but may also be visualized in conventional cryo-sectioned samples. A potential limitation of the SNP labeling method is dilution of signal with cell proliferation. Therefore, the SNP labeling method is best suited to the study of slowly proliferating (dormant) cells or very early stages of metastasis when cells have had limited opportunity to divide, rather than longitudinal observation of tumor growth over extended periods of time. Furthermore, SNP-labeling results in a compartmentalized albeit bright signal that does not label the entire cell body and thus, may be limited to analytical techniques for which identification of the boundaries of the cell type(s) of interest is not essential. Nevertheless, future high-resolution imaging of SNP fate in subcellular structures may offer unprecedented opportunities to better understand how cell proliferation and cell trafficking may be linked to breast cancer cell malignancy and metastasis.

Compared to other non-protein-based labeling strategies, such as fluorescent lipophilic Vybrant dyes (e.g. DiI, DiO, DiD), or semiconductor quantum dots, SNP-labeling of tumor cells enables a broader range of analysis techniques relevant to studies of bone metastasis. For example, lipophilic dyes are similarly limited to usage within short time frames but may not have the capability to resist harsh processing conditions.[9,44] Quantum dots are associated with toxicity concerns that may limit their in vitro and in vivo usage,[45] whereas SNPs have been shown to have low cytotoxicity in vitro in the presence of serum[46] and to be safe for use in rodents, miniswines, and humans.[31,32,47,48] Finally, the compatibility of SNPs with various types of processing enables the use of advanced 3D imaging strategies that preclude the need for physically sectioning bone samples.

Increasing experimental evidence suggests that bone mineral can regulate breast cancer cell behavior,[15,16,49] and that bone mineral may be altered in the context of breast cancer,[10] which has motivated the development of 2D and 2.5D in vitro model systems to study cell-mineral interactions with greater physiological relevance.[16,50] At the same time, 3D in vitro systems incorporating more of the hierarchical structure and composition of the bone microenvironment have been developed.[19,51–54] For example, 3D bone-mimicking microenvironments have been designed using bottom-up[55,56] and top-down approaches[52,57], allowing the study of crosstalk between bone material, stromal cells, and tumor cells in a controlled manner. However, the increased size and dimensionality of such engineered tissues compared to conventional 2D cell culture approaches also introduces greater challenges for 3D imaging and spatial analysis. Here we used bovine bone scaffolds, a top-down in vitro mineralized bone tissue model containing bone marrow, to demonstrate that labeled mineral can be visualized alongside SNP-labeled cells using tissue processing techniques such as PMMA embedding and optical clearing. When combined with optical sectioning techniques including confocal microscopy and light sheet microscopy, this approach will enable experiments focused on elucidating the spatial relationships between disseminated tumor cells, specific marrow components such as blood vessels, and mineralized bone matrix.

In the future, this SNP-based labeling strategy could be combined with immunostaining to better identify other cell types and matrix components of interest and multi-modal electron microscopy-based high-resolution imaging studies as outlined above. The use of these SNPs could also be extended to label other features of interest in the bone microenvironment, by functionalizing the SNPs with peptides to target specific cell types and/or synthesizing them with different dyes.[58,59] We have synthesized these SNPs with the dyes Cy3(+) and Cy5(+), and have recently also synthesized similar SNPs using Cy7 or CW800,[48] which are infrared dyes that would enable even deeper tissue penetration for 3D imaging and potentially longitudinal in vivo tracking of tumor cell trafficking.

Furthermore, SNP compatibility with cryogenic preparation techniques may facilitate correlative imaging approaches, which could enable higher resolution analysis of the bone material in proximity to tumor cells. Here we have used cryo-SEM to observe SNPs at high resolution in near-physiological conditions, and identified them as electron-dense material using backscattered imaging mode. The images are, however, 2D cross-sections taken over limited areas. Alternatively, cryo-planing or cryo-FIB-SEM (focused ion beam-SEM) can produce 3D nanoscale structural data under close to in vivo hydrated conditions.[60,61] The samples are cryo-fixed in vitreous ice before identifying small volumes of interest for imaging. In the future, probes that could be visualized through vitreous ice would expedite selection of such volumes for cryo-FIB-SEM. With increasing usage of optical sectioning and cryo-EM techniques to study complex 3D tissue environments such as bone,[62] as well as methods to track tumor cells longitudinally in vivo, adapting these SNPs for deep tissue imaging applications using infrared dyes such as Cy7 will open up new avenues for bone metastasis research.

4. Conclusion

We describe the development of a cell labeling technique based on fluorescent silica nanoparticles that allows for simultaneous imaging of cells, bone marrow, and mineralized matrix in vitro and for in vivo studies. These SNPs are suitable for short-term in vitro and in vivo studies in which the labeled cells of interest are not expected to rapidly proliferate (e.g., dormancy studies), for samples that undergo formaldehyde-based fixation and traditional bone embedding and sectioning, and for fluorescence imaging techniques including widefield, confocal, and light sheet microscopy. We believe SNPs will enable wider usage of 3D optical sectioning techniques to study tumor-mineral spatial relationships in thick in vitro and in vivo samples. By incorporating further functionalization of the SNPs, this technique will advance future studies focused on the role of cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions in bone metastasis.

5. Experimental Section

Synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles (SNPs):

Nanoparticle Synthesis:

Fluorescent SNPs were synthesized by reacting Cy3(+) or Cy5(+) NHS ester (Lumiprobe) with a 10-fold excess of N-(2-aminoethyl)-3-aminopropyl-trimethoxysilane (APTMS, 95%, Gelest Inc.) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma) overnight under an inert nitrogen environment. To synthesize seed particles, l-arginine (0.012 g, Sigma) was dissolved in deionized (DI) water (9.32 mL, Milli-Q, 18.2 MΩ·cm), stirring slowly (150 rpm) in a 20 mL scintillation vial at 60°C. Use of l-arginine resulted in an initial pH of 9.2. Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, 135 μL) was added slowly in a thin layer to the top surface of the aqueous reaction medium. The resulting mixture was stirred for 8 hrs. An additional 3 TEOS (2×135 μL and 1×143.5 μL) additions were made to the top surface in 8 hr increments. The reaction was left stirring (150 rpm) for 24 hrs after the final TEOS addition. Then, 2 mL of seed particles was added to 8 mL of DI water stirring slowly (~150 rpm) in a 20 mL scintillation vial at 60°C. Cy3(+) conjugate was added dropwise into the stirring solution. The resulting mixture was stirred (150 rpm) for 24 hrs. Co-condensing the dye conjugate with TEOS allows the formation of covalent links of the dye to the silica network, effectively encapsulating the dyes within the SNPs. Native solutions of SNPs were diluted 5 times in DI water. The pH of the solution was increased to 10 using NH4OH (~1 M NH3 in water, Sigma). Methoxy-terminated poly(ethylene glycol) (100 μL, molar mass of ~500 g mol−1, Gelest Inc.) was added dropwise to the stirring solution (600 rpm), which was left stirring overnight. In the next step, the temperature was increased to 80°C and the stirring was stopped. PEGylation was completed after 12 hrs at 80°C. Chemical composition and surface PEGylation of SNPs synthesized as such have been previously well-characterized.[63,64] Cy5(+)-SNPs were prepared in the same way exchanging Cy3(+) for the same molar concentration of Cy5(+).

Nanoparticle purification:

To increase SNP purity, we performed gel permeation chromatography (GPC) using a BioLogic LP system alongside a 275-nm UV detector with Sephacryl S-500 HR (GE Healthcare). Particle solutions were syringe filtered (EZFlow Syringe Filter hydrophilic PVDF membrane), up-concentrated by centrifuge spin-filters (Spin-XR UF 20 MWCO 30K PES), sent through the column with a 0.9-wt% NaCl solution, and collected by a BioFrac fraction collector. The corresponding GPC fractions were transferred back into DI water by washing the particles at least 5 times in a spin-filter using sterile DI water to prevent contamination.

Nanoparticle characterization:

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy:

A 543-nm continuous wave HeNe laser (Cy3(+)) or a 633-nm (Cy5(+)) continuous wave solid state laser was reflected by a dichroic mirror and focused onto the object plane of a water immersion microscope objective (Zeiss Plan-Neofluar 63x NA 1.2). The fluorescence was collected by the same objective and spatially filtered by a 50-μm pinhole located at the image plane of an avalanche photodiode detector (SPCM-AQR-14, PerkinElmer). Time traces were correlated by a hardware correlator card (Flex03LQ, Correlator.com). Tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) was used as a dye standard for the green laser line and Alexa Fluor 647 was used for the red line for system alignment and focal volume size determination due to its known diffusion coefficient.

Correlation data were collected in three sets of five 30-second runs. Correlation curves were then fit to a correlation function accounting for photoinduced cis-trans isomerization or triplet formation, as shown in Equation (1):

| (1) |

Here, N is the mean number of particles within the detection volume, κ is the structure factor determined by the ratio of the axial and radial radii (ωz and ωxy, respectively) of the observation volume, and τD is the characteristic diffusion time of an object through the observation volume. τD is defined as , where D is the respective diffusion coefficient. T is the time- and space-averaged fraction of fluorophores in fast forming dark state, and τF is the characteristic relaxation time of the dark state forming process. The Stokes-Einstein relation, Equation (2), was applied to determine particle diameters:

| (2) |

Here, kb is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, and η is the dynamic viscosity. The average number of dyes per particle, n, was calculated according to Equation (3):

| (3) |

Here, Cdye is the measured dye concentration derived from the dye extinction coefficient using the relative absorbance, and Cparticle is the particle concentration determined by FCS.

Steady-state absorption and emission spectroscopy:

Absorbance spectra were recorded in DI water on a Varian Cary 5000 spectrophotometer in a 3 mL quartz cuvette against a reference quartz cuvette with DI water. Emission spectra of the same samples were recorded on a Photon Technologies International Quantamaster spectrofluorometer. Due to spectral red shifts after dye encapsulation, fluorescence excitations were adjusted accordingly. Cy3(+) free dye was excited at 543 nm and recorded from 543 to 700 nm, while Cy3(+)-SNPs were excited at 550 nm and recorded from 550 to 700 nm. Cy5(+) free dye was excited at 640 nm and recorded from 640 to 800 nm, while Cy5(+)-SNPs were excited at 647 nm and recorded from 647 to 800 nm.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM):

TEM images were taken using a FEI Tecnai T12 Spirit microscope operated at an acceleration voltage of 120 kV. TEM grids were prepared by drop casting from the purified nanoparticle solutions.

Cell culture:

Parental MDA-MB-231 (ATCC) or RFP-expressing MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in growth media consisting of DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37ºC, 5% CO2, with media changed every 2 days.

Labeling with SNPs:

Unless otherwise specified, cells were incubated with 1 μm SNPs in fresh growth media for 24–48 hours. Unlabeled cells (Blank) were given fresh growth media with a matched volume of DI water to control for media dilution effects. After this incubation time, cells were washed three times with PBS (HyClone), then trypsinized (considered day 0), counted, and seeded into new well plates for time-course experiments, subjected to flow cytometry, resuspended in fixative, or resuspended in ice-cold PBS for mouse injections. For all in vitro studies, Cy3(+)-SNPs were used. For in vivo mouse studies, Cy5(+)-SNPs were used. For mitomycin C (MMC) treated cells, cells were washed three times with PBS following initial labeling with SNPs, then incubated with MMC (Abcam ab120797, 10 μg ml−1 in DMSO) for 1 hour. Following MMC treatment, cells were used for flow cytometry or seeded into new well plates for subsequent flow cytometry measurements.

Flow cytometry:

Cells were prepared for flow cytometry by trypsinization (0.25% Trypsin-EDTA, Gibco) and resuspension in PBS with 2.5% FBS and 2 mm EDTA (FACS buffer). Cells were kept in FACS buffer on ice until immediately prior to analysis using a flow cytometer (BD Accuri C6). After gating based on forward and side scatter, and doublet exclusion, data were exported. A custom Matlab script was used to generate histograms of fluorescence intensity and to calculate percentage of positive cells (0.1% of unlabeled control cells was used for the vertical gating cutoff).

Cryo-scanning electron microscopy (cryo-SEM):

MDA-MB-231 cells were grown in tissue culture flasks and incubated with SNPs for 48 hours. At the end of incubation, cells were washed three times with PBS, trypsinized, and centrifuged (200 g, 5 min). The cell pellet was chemically fixed (10% neutral buffered formalin) and suspended in PBS. High pressure freezing was performed as follows: the cell suspension was centrifuged (290g, 4 min) until a dense cell pellet was achieved. 4 μl drop of the pellet was sandwiched between two metal discs (3-mm diameter, 0.1-mm cavities) and cryoimmobilized in a high-pressure freezing device (EM ICE; Leica). Frozen samples were mounted on a holder under liquid N2 and transferred to a Freeze Fracture BAF 60 device (Bal-Tec) using a Vacuum Cryo Transfer unit VCT 100 (Bal-Tec). Samples were fractured at a vacuum of <5 ·10−7 mbar and a temperature of −120°C, and observed using an Ultra 55 SEM (Zeiss, Germany). Throughout the imaging session, samples were kept in a frozen-hydrated state by use of a cryo-stage operating at a temperature of −120°C.

Fluorescence imaging and image analysis:

For imaging of labeled cells on plastic, samples were imaged on a widefield fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1). To improve visualization of SNPs, Enhance Local Contrast (CLAHE) was used in ImageJ. Confocal laser scanning microscopes (Zeiss LSM 710 or 880) were used to collect z-stack images of SNPs within cells and bone scaffolds. Image analysis was conducted in Zen lite and ImageJ. Line intensity data was acquired using Zen lite, plotted using local polynomial regression fitting in R, and normalized relative to the maximum intensity for the SNP samples in each processing condition. For all comparisons of SNP-labeled cells to RFP-labeled cells within each processing condition, imaging acquisition and analysis parameters were kept constant.

Signal-to-noise experiment:

For signal-to-noise ratio comparisons, Cy3(+)-SNP-labeled cells and RFP-labeled cells were stained with Vybrant DiD to visualize the cell membrane (Invitrogen), then imaged on a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss 710). Imaging parameters were optimized for Cy3(+)-SNP signal and applied for both Cy3(+)-SNP and RFP samples. To analyze these images, whole cell regions of interest (ROIs) were identified using DiD signal in Image J. Whole cell ROIs and 2 μm square ROIs were used to measure mean and maximum intensity of the signal, which was divided by background (noise) intensity in a 20 μm square ROI not containing cells.

Cell growth calculations:

We normalized SNP signal to day 0, then fitted SNP signal in cells over time to the following exponential decay Equation (4):

| (4) |

Here, S0 is the initial normalized SNP signal, t is the time in days, and τ is the time constant which corresponds to half-life of the signal or population doubling time for the cells. A theoretical cell growth curve was then calculated representing cell count fold change relative to day 0 using the following exponential growth Equation (5):

| (5) |

Fixation experiments:

Cells were fixed overnight at 4ºC in 10% neutral-buffered formalin or 70% ethanol. For formalin-to-ethanol conditions, cells were moved to ethanol following overnight fixation. At the same time, cells fixed in formalin or ethanol only were moved to PBS. Formalin-to-ethanol cells were moved to PBS the next day, after which all cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Preparation of bone scaffolds and cultures:

Subchondral bone biopsies were extracted from 1–3 day old neonatal bovine distal femurs using a 6 mm diameter coring bit as previously described,[42] then cut to 2 mm thick cylinders. Before seeding with cells, scaffolds were incubated in 70% ethanol for 15 minutes, followed by PBS washes. Unfixed scaffolds were seeded at 1.5 million cells per scaffold and imaged after 2 hours of cell adhesion. For fixed scaffolds, 200,000 cells were seeded per scaffold and allowed to adhere overnight before fixation and processing. Prior to cell seeding, bone scaffolds were incubated in calcein (0.15 mg mL−1 in PBS, Sigma) for 10 minutes to label the surface of mineralized bone matrix. Cells were identified by DAPI staining (Invitrogen).

Embedding and sectioning:

Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) embedding was carried out by dehydrating fixed bone samples in a graded ethanol series, followed by infiltration and embedding in MMA.[65] Samples were sectioned using low speed cutting machine (Buehler IsoMet). Prior to paraffin embedding, bone scaffolds or tibiae were decalcified in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (10% EDTA, pH 7.4) for 2 weeks. Following paraffin embedding, samples were sectioned (5 μm sections for scaffolds, 10 μm sections for tibiae), then stained with DAPI (5 min at 1:1000) prior to mounting.

Optical clearing and light sheet microscopy:

Optical clearing of bone samples was carried out as previously described.[66] Briefly, fixed samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, followed by incubation in ethyl cinnamate (Sigma). Optically cleared samples were immersed in ethyl cinnamate and imaged on a light sheet microscope (LaVision BioTec). Bone scaffolds were imaged using the 488 nm laser to detect calcein and the 561 laser to detect Cy3(+)-SNPs. Tibiae were imaged using the 488 nm laser to detect calcein and the 640 laser to detect Cy5(+)-SNPs. Arivis Vision4D and ImageJ were used to process light sheet microscopy images.

Mouse experiment:

This mouse study was performed in accordance with Cornell University animal care guidelines and was approved by Cornell University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Female athymic nude-Foxn1nu (Envigo) mice (n = 6) were housed 4 animals per cage with ad libitum access to food and water. At 5–6 weeks of age, mice were injected intraperitoneally with calcein (15 mg kg−1, pH 7.4 in PBS) 1 day prior to cell injection. To model bone metastasis, luciferase-expressing cells (100,000 cells in 100 μL PBS) were injected into the left cardiac ventricle using ultrasound guidance (Vevo VisualSonics 2100). Injection into the systemic circulation was verified by bioluminescence imaging (Xenogen) (Figure S8). Mice were anesthetized during cardiac injection and bioluminescence imaging using isoflurane (2.5%–3.5%). Buprenorphine was injected intraperitoneally as an analgesic before cardiac injection, and administered twice more within 24 hours of cardiac injection. Tibiae were harvested after 2 days. Immediately following harvest, tibiae were fixed in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4 in PBS) for 16 hours before further processing (n = 3 tibiae from different mice per processing condition).

Data analysis:

GraphPad Prism was used to plot data and run statistical tests. Unless otherwise indicated, plots represent mean ± standard deviation. In vitro experiments were repeated at least in duplicate with sample numbers of n = 3 unless otherwise indicated. Statistical tests are indicated in the respective figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Josue Santana for assistance with PMMA embedding and sectioning, Adrian Shimpi for help with ImageJ cell analysis and flow cytometry analysis, Matthew Tan for help with confocal microscopy, Matthew Whitman for providing bone scaffolds, the Cornell Histology Core for paraffin embedding and sectioning, and the Cornell Center for Animal Resources and Education (CARE) staff for animal care. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Human Frontier Science Program (HFSP RGP0016/2017 to C.F., L.A., and L.A.E.) and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under the following award numbers: F31CA228448 (to A.E.C.), U54CA199081 (to U.B.W.), U54CA210184 (Center on the Physics of Cancer Metabolism, to C.F.). This work made use of the following instruments in the Cornell University Biotechnology Resource Center (BRC) Imaging Facility: Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope (NIH S10RR025502), Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope (NYSTEM C029155, NIH S10OD018516), light sheet microscope (NIH S10OD023466), VisualSonics Vevo-2100 ultrasound (NIH S10OD016191), and IVIS-Spectrum optical imager (NIH S10OD025049). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

U.B.W. sits on the board of Elucida Technologies, Inc., a company commercializing silica nanoparticle technology coming out of the Wiesner labs for applications in oncology.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Aaron E. Chiou, Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA

Joshua A. Hinckley, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

Rupal Khaitan, Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

Neta Varsano, Department of Structural Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, 7610001, Israel.

Jonathan Wang, Division of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

Henry F. Malarkey V, Department of Applied and Engineering Physics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA

Christopher J. Hernandez, Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

Rebecca M. Williams, Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA

Lara A. Estroff, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA Kavli Institute at Cornell for Nanoscale Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

Steve Weiner, Department of Structural Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, 7610001, Israel.

Lia Addadi, Department of Structural Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, 7610001, Israel.

Ulrich B. Wiesner, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA

Claudia Fischbach, Meinig School of Biomedical Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA; Kavli Institute at Cornell for Nanoscale Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

References

- [1].Coleman RE, Cancer Treat. Rev 2001, 27, 165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mundy GR, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chambers AF, Groom AC, MacDonald IC, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Guise TA, J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact 2002, 2, 570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Goldstein RH, Reagan MR, Anderson K, Kaplan DL, Rosenblatt M, Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 10044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ghajar CM, Peinado H, Mori H, Matei IR, Evason KJ, Brazier H, Almeida D, Koller A, Hajjar KA, Stainier DYR, Chen EI, Lyden D, Bissell MJ, Nat. Cell Biol 2013, DOI 10.1038/ncb2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wang H, Yu C, Gao X, Welte T, Muscarella AM, Tian L, Zhao H, Zhao Z, Du S, Tao J, Lee B, Westbrook TF, Wong STC, Jin X, Rosen J, Osborne CK, Zhang XHF, Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Luo X, Fu Y, Loza AJ, Murali B, Leahy KM, Ruhland MK, Gang M, Su X, Zamani A, Shi Y, Lavine KJ, Ornitz DM, Weilbaecher KN, Long F, Novack DV, Faccio R, Longmore GD, Stewart SA, Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang N, Docherty FE, Brown HK, Reeves KJ, Fowles ACM, Ottewell PD, Dear TN, Holen I, Croucher PI, Eaton CL, J. Bone Miner. Res 2014, 29, 2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].He F, Chiou AE, Loh HC, Lynch M, Seo BR, Song YH, Lee MJ, Hoerth R, Bortel EL, Willie BM, Duda GN, Estroff LA, Masic A, Wagermaier W, Fratzl P, Fischbach C, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2017, 114, 10542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Coleman R, Cameron D, Dodwell D, Bell R, Wilson C, Rathbone E, Keane M, Gil M, Burkinshaw R, Grieve R, Barrett-Lee P, Ritchie D, Liversedge V, Hinsley S, Marshall H, Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Korde LA, Doody DR, Hsu L, Porter PL, Malone KE, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 2018, 27, 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ottewell P, Wilson C, Breast Cancer Basic Clin. Res 2019, 13, 117822341984350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pathi SP, Kowalczewski C, Tadipatri R, Fischbach C, PLoS One 2010, 5, DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0008849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].He F, Springer NL, Whitman MA, Pathi SP, Lee Y, Mohanan S, Marcott S, Chiou AE, Blank BS, Iyengar N, Morris PG, Jochelson M, Hudis CA, Shah P, Kunitake JAMR, Estroff LA, Lammerding J, Fischbach C, Biomaterials 2019, 224, 119489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Choi S, Friedrichs J, Song YH, Werner C, Estroff LA, Fischbach C, Biomaterials 2019, 198, 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kuhn LT, Grynpas MD, Rey CC, Wu Y, Ackerman JL, Glimcher MJ, Calcif. Tissue Int 2008, DOI 10.1007/s00223-008-9164-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Boskey A, Mendelsohn R, J. Biomed. Opt 2005, 10, 031102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pathi SP, Lin DDW, Dorvee JR, Estroff LA, Fischbach C, Biomaterials 2011, 32, 5112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Phadke PA, Mercer RR, Harms JF, Jia Y, Clin. Cancer … 2006, 12, 1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wright LE, Ottewell PD, Rucci N, Peyruchaud O, Pagnotti GM, Chiechi A, Buijs JT, Sterling JA, Bonekey Rep. 2016, 5, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kimura-Suda H, Takahata M, Ito T, Shimizu T, Kanazawa K, Ota M, Iwasaki N, PLoS One 2018, 13, e0189650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Giepmans BNG, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY, Science (80-. ). 2006, DOI 10.1126/science.1124618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ow H, Larson DR, Srivastava M, Baird BA, Webb WW, Wiesnert U, Nano Lett. 2005, DOI 10.1021/nl0482478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Choi J, a Burns A, Williams RM, Zhou Z, Flesken-Nikitin A, Zipfel WR, Wiesner U, Nikitin AY, J. Biomed. Opt 2007, 12, 064007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fuller JE, Zugates GT, Ferreira LS, Ow HS, Nguyen NN, Wiesner UB, Langer RS, Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Larson DR, Ow H, Vishwasrao HD, Heikal AA, Wiesner U, Webb WW, Chem. Mater 2008, 20, 2677. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kao T, Kohle F, Ma K, Aubert T, Andrievsky A, Wiesner U, Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kohle FFE, Hinckley JA, Wiesner UB, J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 9813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chen F, Ma K, Benezra M, Zhang L, Cheal SM, Phillips E, Yoo B, Pauliah M, Overholtzer M, Zanzonico P, Sequeira S, Gonen M, Quinn T, Wiesner U, Bradbury MS, Chem. Mater 2017, 29, 8766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Benezra M, Penate-Medina O, Zanzonico PB, Schaer D, Ow H, Burns A, DeStanchina E, Longo V, Herz E, Iyer S, Wolchok J, Larson SM, Wiesner U, Bradbury MS, J. Clin. Invest 2011, 121, 2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Phillips E, Penate-Medina O, Zanzonico PB, Carvajal RD, Mohan P, Ye Y, Humm J, Gonen M, Kalaigian H, Schoder H, Strauss HW, Larson SM, Wiesner U, Bradbury MS, Sci. Transl. Med 2014, 6, 260ra149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhang S, Li J, Lykotrafitis G, Bao G, Suresh S, Adv. Mater 2009, 21, 419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gardinier TC, Kohle FFE, Peerless JS, Ma K, Turker MZ, Hinckley JA, Yingling YG, Wiesner U, ACS Nano 2019, acsnano.8b07876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fischbach C, Chen R, Matsumoto T, Schmelzle T, Brugge JS, Polverini PJ, Mooney DJ, Nat. Methods 2007, 4, 855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Carlson P, Dasgupta A, Grzelak CA, Kim J, Barrett A, Coleman IM, Shor RE, Goddard ET, Dai J, Schweitzer EM, Lim AR, Crist SB, Cheresh DA, Nelson PS, Hansen KC, Ghajar CM, Nat. Cell Biol 2019, 21, 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nakagawa A, Von Alt K, Lillemoe KD, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Warshaw AL, Liss AS, Biotechniques 2015, 59, 153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Pascart T, Cortet B, Olejnik C, Paccou J, Migaud H, Cotten A, Delannoy Y, During A, Hardouin P, Penel G, Falgayrac G, Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Goldstein DB, Chin JH, Fed. Proc 1981, 40, 2073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kang Y, Siegel PM, Shu W, Drobnjak M, Kakonen SM, Cordón-Cardo C, Guise TA, Massagué J, Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Greenbaum A, Chan KY, Dobreva T, Brown D, Balani DH, Boyce R, Kronenberg HM, McBride HJ, Gradinaru V, Sci. Transl. Med 2017, 9, eaah6518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Boys AJ, Zhou H, Harrod JB, McCorry MC, Estroff LA, Bonassar LJ, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2019, DOI 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b00176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Su W, Yang L, Luo X, Chen M, Liu J, Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med 2019, 143, 362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Allocca G, Hughes R, Wang N, Brown HK, Ottewell PD, Brown NJ, Holen I, J. Bone Oncol 2019, 17, 100244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Derfus AM, Chan WCW, Bhatia SN, Nano Lett. 2004, DOI 10.1021/nl0347334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Saikia J, Yazdimamaghani M, Hadipour Moghaddam SP, Ghandehari H, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 34820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bradbury MS, Phillips E, Montero PH, Cheal SM, Stambuk H, Durack JC, Sofocleous CT, Meester RJC, Wiesner U, Patel S, Integr. Biol 2013, 5, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Chen F, Madajewski B, Ma K, Karassawa Zanoni D, Stambuk H, Turker MZ, Monette S, Zhang L, Yoo B, Chen P, Meester RJC, de Jonge S, Montero P, Phillips E, Quinn TP, Gönen M, Sequeira S, de Stanchina E, Zanzonico P, Wiesner U, Patel SG, Bradbury MS, Sci. Adv 2019, 5, eaax5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Choi S, Coonrod S, Estroff L, Fischbach C, Acta Biomater. 2015, 24, 333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].V Taubenberger A, Quent VM, Thibaudeau L, Clements JA, Hutmacher DW, J. Bone Miner. Res 2013, 28, 1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bersini S, Jeon JS, Dubini G, Arrigoni C, Chung S, Charest JL, Moretti M, Kamm RD, Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Holen I, Nutter F, Wilkinson JM, Evans CA, Avgoustou P, Ottewell P, Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2015, 32, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Weisgerber DW, Erning K, Flanagan CL, Hollister SJ, Harley BAC, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 2016, 61, 318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Bittner KR, Jiménez JM, Peyton SR, Adv. Healthc. Mater 2020, 1901459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bray L, Secker C, Murekatete B, Sievers J, Binner M, Welzel P, Werner C, Cancers (Basel). 2018, 10, 292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Thrivikraman G, Athirasala A, Gordon R, Zhang L, Bergan R, Keene DR, Jones JM, Xie H, Chen Z, Tao J, Wingender B, Gower L, Ferracane JL, Bertassoni LE, Nat. Commun 2019, 10, DOI 10.1038/s41467-019-11455-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sakolish C, House JS, Chramiec A, Liu Y, Chen Z, Halligan SP, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Rusyn I, Toxicol. Sci 2019, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Riley RS, Day ES, Small 2017, 13, 1700544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Chen F, Ma K, Madajewski B, Zhuang L, Zhang L, Rickert K, Marelli M, Yoo B, Turker MZ, Overholtzer M, Quinn TP, Gonen M, Zanzonico P, Tuesca A, Bowen MA, Norton L, Subramony JA, Wiesner U, Bradbury MS, Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Chang IYT, Joester D, J. Struct. Biol 2015, 192, 569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Vidavsky N, Akiva A, Kaplan-Ashiri I, Rechav K, Addadi L, Weiner S, Schertel A, J. Struct. Biol 2016, 196, 487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Haimov H, Shimoni E, Brumfeld V, Shemesh M, Varsano N, Addadi L, Weiner S, Bone 2020, 130, 115086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ma K, Zhang D, Cong Y, Wiesner U, Chem. Mater 2016, DOI 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b00030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ma K, Mendoza C, Hanson M, Werner-Zwanziger U, Zwanziger J, Wiesner U, Chem. Mater 2015, 27, 4119. [Google Scholar]

- [65].An YH, Martin KL, An YH, Moreira PL, Kang QK, Gruber HE, in Handb. Histol. Methods Bone Cartil, Humana Press, New Jersey, 2003, pp. 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- [66].Grüneboom A, Hawwari I, Weidner D, Culemann S, Müller S, Henneberg S, Brenzel A, Merz S, Bornemann L, Zec K, Wuelling M, Kling L, Hasenberg M, Voortmann S, Lang S, Baum W, Ohs A, Kraff O, Quick HH, Jäger M, Landgraeber S, Dudda M, Danuser R, Stein JV, Rohde M, Gelse K, Garbe AI, Adamczyk A, Westendorf AM, Hoffmann D, Christiansen S, Engel DR, Vortkamp A, Krönke G, Herrmann M, Kamradt T, Schett G, Hasenberg A, Gunzer M, Nat. Metab 2019, 1, 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.