Abstract

Granulocyte recruitment to the pulmonary compartment is a hallmark of progressive tuberculosis (TB). This process is well-documented to promote immunopathology, but can also enhance the replication of the pathogen. Both the specific granulocytes responsible for increasing mycobacterial burden and the underlying mechanisms remain obscure. We report that the known immunomodulatory effects of these cells, such as suppression of protective T-cell responses, play a limited role in altering host control of mycobacterial replication in susceptible mice. Instead, we find that the adaptive immune response preferentially restricts the burden of bacteria within monocytes and macrophages compared to granulocytes. Specifically, mycobacteria within inflammatory lesions are preferentially found within long-lived granulocytes that express intermediate levels of the Ly6G marker and low levels of antimicrobial genes. These cells progressively accumulate in the lung and correlate with bacterial load and disease severity, and the ablation of Ly6G-expressing cells lowers mycobacterial burden. These observations suggest a model in which dysregulated granulocytic influx promotes disease by creating a permissive intracellular niche for mycobacterial growth and persistence.

Introduction

Infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) can result in a diverse range of clinical outcomes. At one end of the spectrum, some individuals contain the infection through effective immune control, restricting Mtb growth and possibly even eradicating the bacteria. Conversely, individuals who fail to control Mtb replication or the subsequent tissue-damaging inflammation develop tuberculosis (TB), a disease defined by progressive bacterial replication, pulmonary necrosis, and cavitary lesions that promote the transmission of bacteria1.

The factors determining TB disease progression remain incompletely defined, but genetic evidence from both the human and mouse systems have converged on the importance of an immune network consisting of type I and type II interferons (IFN) and interleukin-1 (IL1). Mendelian defects in IFNγ production or signaling cause susceptibility to mycobacterial infection in humans2. Similarly, mice lacking any component of the IFNγ pathway are profoundly susceptible to Mtb3,4. T-cell-derived IFNγ mediates its protective effect in at least two distinct ways. When activating macrophages, this cytokine can induce still uncharacterized antimicrobial pathways that control the intracellular replication of the pathogen, and it can induce nitric oxide synthase 2 (Nos2)5. While the resulting nitric oxide (NO) is often considered an antimicrobial mediator, in the context of Mtb infection the major protective effect of NO is due to its ability to inhibit production of mature IL1 and prevent granulocyte infiltration6. This inhibition of IL1 during persistent infection is critical for protective immunity, as the susceptibility of NO-deficient mice to Mtb infection is largely dependent on IL1 driven inflammation6, and human genetic variants that increase IL1β expression are associated with more severe disease7. Finally, the type I IFN response is a marker of disease progression, and counter-regulates both IFNγ and IL18,9. Mutations of the type I IFN receptor are associated with protection from disease in both mouse models10–12 and humans13. While the diversity of human immune responses described above is not reproduced in wild-type C57BL6 (Bl6 WT) mice, recent work indicates that susceptibility due to dysregulation of the IFN/IL1 axis can be modeled in other well-characterized mouse strains. For example, susceptibility in 129SvPas mice can be reversed by inhibition of type 1 IFN signaling10. Similarly, susceptibility in C3HebFeJ mice is largely due to a mutation in the Ipr1 isoform of the Ifi75 gene, which produces type I IFN-driven disease14. The effects of persistent IL1 can be modeled in Nos2-deficient mice as well, since susceptibility in these animals depends on IL1-dependent inflammation6.

A common feature of severe TB in both patients and these diverse susceptible mice is the infiltration of granulocytic cells, mostly neutrophils, into the lung. While neutrophil recruitment is critical for protective immunity to many pulmonary pathogens15,16, and certain animal models suggest neutrophils can provide some protection at early stages of mycobacterial infection17,18, multiple lines of evidence in humans and susceptible mice indicate that these cells are pathologic during TB. In humans, neutrophils represent a significant fraction of infected cells observed in sputum19, and biomarkers related to neutrophil function are a strong predictor of disease progression20,21. In mice, depletion of neutrophils from a variety of susceptible lines reduces disease and restores host control of bacterial replication6,22,23. These observations suggest that neutrophil infiltration is a common feature of TB progression promoting both tissue damage and bacterial replication, regardless of underlying causes of susceptibility. While mechanisms behind neutrophil-mediated tissue damage have been described24, it remains unclear why infiltration of these generally antimicrobial cells promotes Mtb replication.

Neutrophil infiltration could promote bacterial replication in two fundamentally different ways. First, these cells have known immunoregulatory functions and have been shown to secrete IL1025, a cytokine which inhibits protective T-cell responses in Mycobacterium avium infected mice26. More generally, granulocytes can act as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) capable of inhibiting a protective adaptive immune response via suppression of T-cell function27–29. Alternatively, neutrophils are also phagocytes capable of providing a permissive niche for intracellular Mtb replication30,31. Here, we used multiple mouse models of susceptibility to investigate how neutrophil infiltration promotes Mtb growth, discovering a subset of lung granulocytic cells that are permissive to Mtb infection, express low levels of antimicrobial genes, and exacerbate disease.

Results

Influx of Ly6GPos cells into the pulmonary compartment correlates with Mtb burden, inflammatory cytokines, and disease severity.

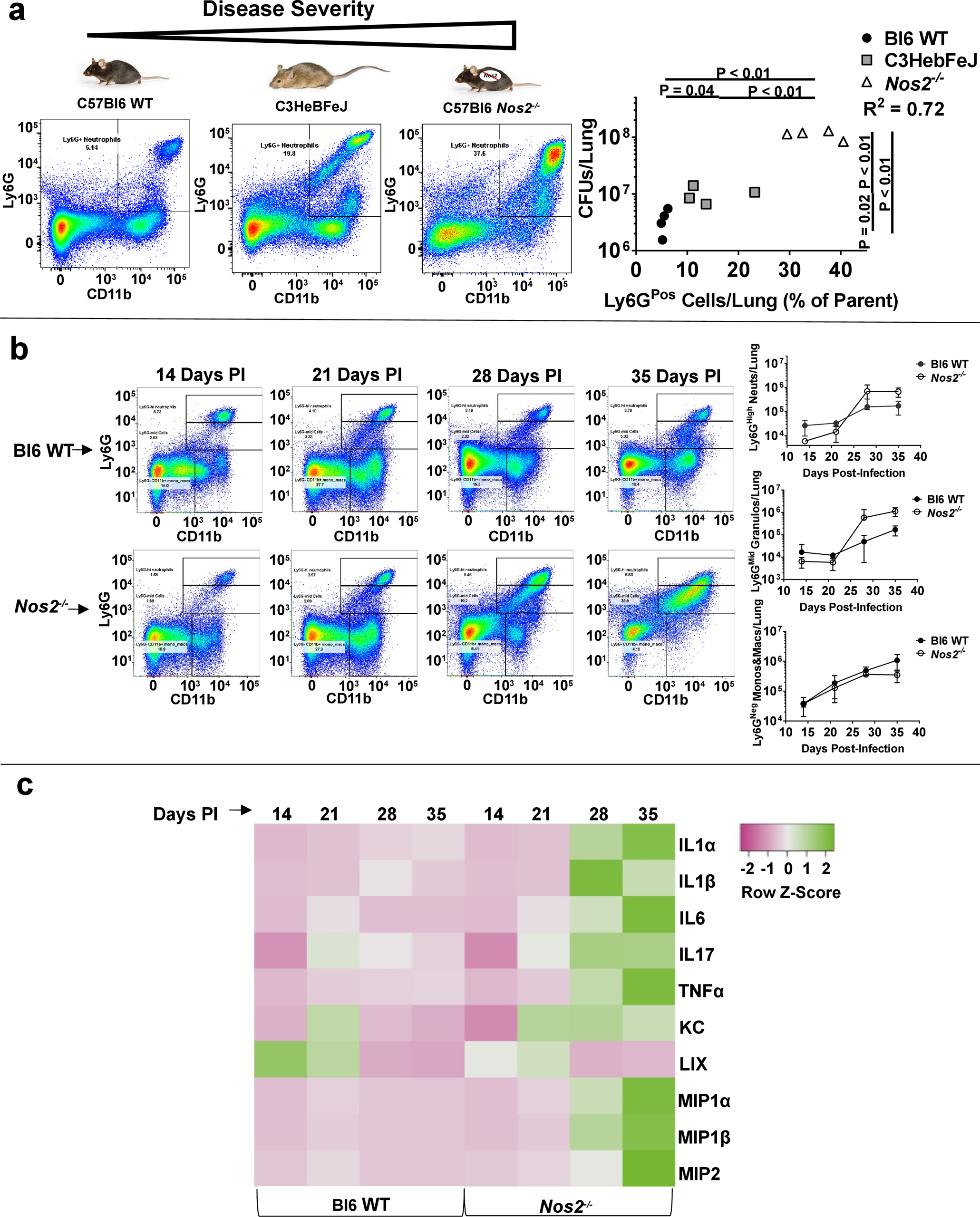

To determine the connection between neutrophils and Mtb growth, we compared three genetically distinct murine models of disease severity. Wild-type C57BL6 (Bl6 WT) mice are the most resistant to disease, C3HeBFeJ mice have an intermediate susceptibility associated with type I IFN production, and Nos2−/− C57Bl6 mice suffer severe IL1-dependent disease. We characterized myeloid cells within these models by cell-surface phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 1), finding that disease severity was reflected by the influx of CD19Neg CD11bHigh Ly6GPos GR1High Ly6CHigh neutrophils into the lung at 28 days post-infection (PI) (Fig. 1a). As reported in other settings6,3, the number of pulmonary neutrophils across the three disease models remained proportional to the number of colony forming units (CFUs) in the lung (Fig. 1a-graph). Further characterization of myeloid cells revealed that during more severe disease, a subset of Ly6GMid granulocytes (CD19Neg CD11bHigh Ly6GMid GR1Mid Ly6CHigh) became apparent (Fig. 1b). The abundance of these cells increased over time, becoming the prominent Ly6G-expressing cell population in Nos2−/− mice at 35 days PI (Fig. 1b). This change in cellular phenotype coincided with an increase in proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 1c). Collectively, these data suggested a causative link between neutrophil influx, bacterial burden, and hyperinflammatory disease.

Figure 1. Influx of Ly6GPos cells into the pulmonary compartment correlates with Mtb burden, inflammatory cytokines, and disease severity.

a Mouse models of increasingly severe disease (left to right), with representative scatterplots of CD11bHigh Ly6GPos pulmonary cells at 28 days PI, and quantified (far right) as percent Ly6Gpos cells by recovered CFUs in the lung of each individual mouse. b Representative scatterplots (left) and quantification (right) of CD11bHigh Ly6GHigh neutrophils (top right), CD11bHigh Ly6GMid granulocytes (middle right), and CD11bHigh Ly6GNeg monocytes/macrophages (bottom right) in Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− mice at the indicated time points PI. N = 4 mice per group and error bars represent standard deviation between biological replicates within each group. c Multiplex analysis of the indicated cytokines and chemokines in the lungs of Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− mice at the indicated time points PI. Heatmap represents the average pg/mL of detected cytokine/chemokine from 4 mice per group scaled by row.

Genetic or antibody-mediated depletion of Ly6GPos cells decreases Mtb burden without affecting other immune cells.

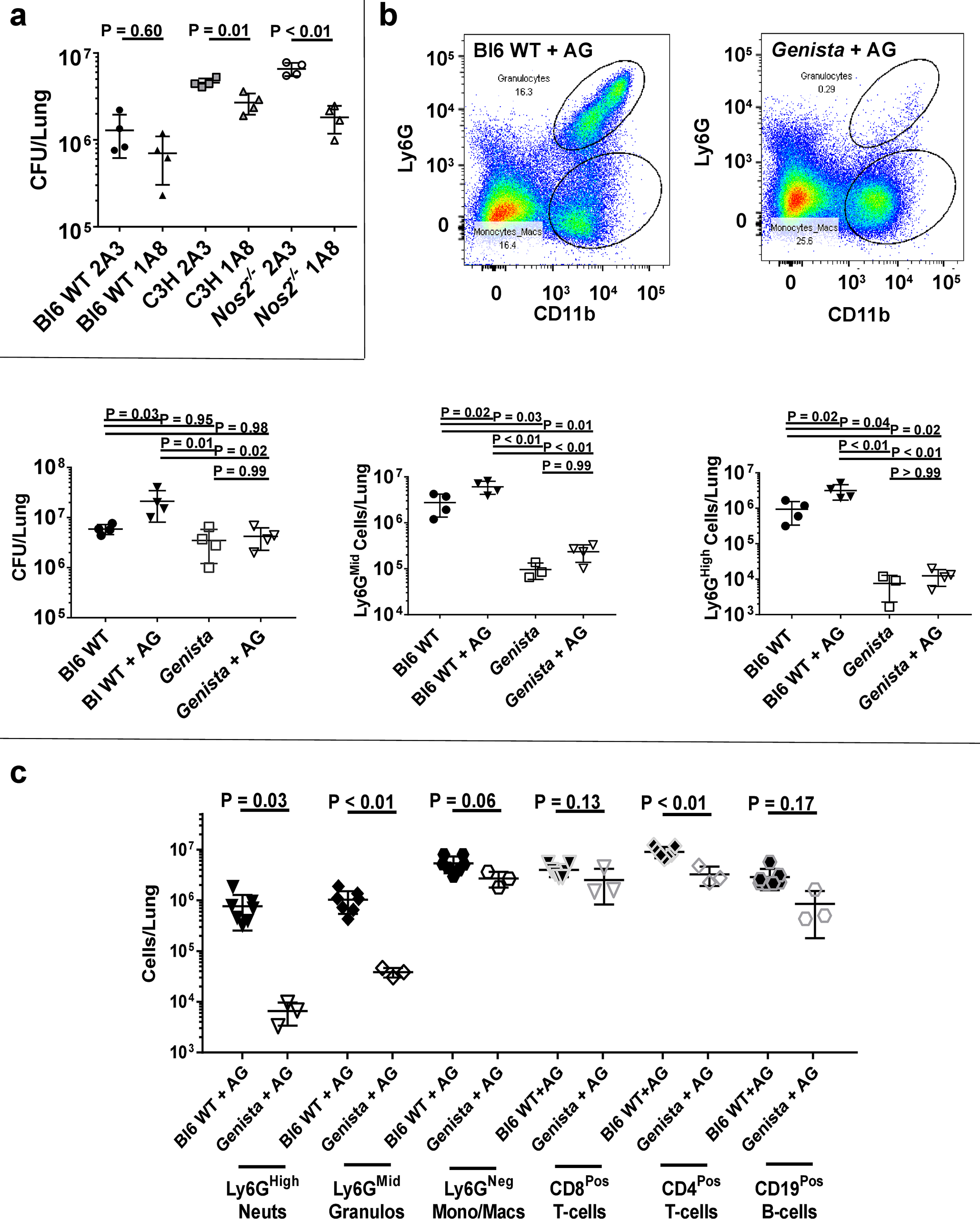

To quantify the contribution of Ly6GPos cell influx to bacterial replication within each setting, we first used antibody-mediated cell depletion to remove Ly6GPos cells from infected hosts. Anti-Ly6G (1A8) treatment depleted both GR1High and GR1Mid populations from the lungs (Supplementary Fig. 2a). As reported previously6, removal of these cells between days 11 and 23 PI decreased the pulmonary bacterial load (Fig. 2a). The effect of depletion on CFUs correlated with the number of Ly6GPos cells, as this treatment had a minimal effect in Bl6 WT mice, but a progressively larger effect in C3HeBFeJ and Nos2−/− backgrounds. Depletion of Ly6GPos cells did not alter the number or phenotype of lymphocytes within the lungs, as we found no difference in the number of total T-cells, total B-cells, FoxP3Pos regulatory T-cells (Tregs), or T-betPos Th1-cells between depleted and non-depleted animals (Supplementary Fig. 2b–d). Additionally, depletion did not obviously affect lymphocyte function, as neither the number of IFNγ-expressing T-cells nor IL10-expressing Tregs changed, nor did the amount of IFNγ in lung homogenate (Supplementary Fig. 2c–d).

Figure 2. Genetic or antibody-mediated depletion of Ly6GPos cells decreases Mtb burden without affecting other immune cells.

a CFUs per lung at 25 days PI within Bl6 WT, C3HebFeJ, or Nos2−/− mice treated with anti-Ly6g depleting antibody (1A8) or isotype control (2A3). b Representative scatterplots of lung cells from infected Bl6 WT (top mid) or Genista (top right) mice treated with aminoguanidine (AG), with quantified CFUs (bottom left), Ly6GMid cells (bottom mid), or Ly6GHigh cells (bottom right) per lung at 56 days PI with or without AG treatment. c Quantification of the indicated immune cells in the lungs of AG-treated Bl6 WT mice or AG-treated Genista mice at 56 days PI. N = 3–7 mice per group and error bars represent standard deviation between biological replicates within each group. Statistical values based on unpaired Student’s T-test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison analysis.

To control for non-specific effects of antibody-mediated depletion and timing-dependent phenotypes, we used a complementary genetic model of neutropenia. C57Bl6 Genista mice specifically lack Ly6GPos neutrophils due to a hypomorphic mutation in the gfi1 transcription factor33. We confirmed that these animals do not recruit Ly6GPos cells to their lungs upon Mtb infection, even upon Nos2 inhibition with aminoguanidine (AG) (Fig. 2b), which otherwise mimics the Nos2−/− mutation and increases pulmonary infiltration of Ly6GPos cells and CFU load in Bl6 WT animals (Supplementary Fig. 3c). As observed during antibody-mediated depletion, genetic abrogation of these cells correlated with reduced bacterial burden, as AG had no effect on bacterial load in Genista mice (Fig. 2b). The lack of Ly6GPos cells in Genista mice also had a minimal impact on the total numbers of macrophages, CD8Pos T-cells, CD4Pos T-cells, and CD19Pos B-cells, even upon AG-treatment to accentuate granulocyte recruitment (Fig. 2c). The modest reduction of other cell types in Genista mice likely reflects the relative reduction in CFUs and concomitant decrease in inflammation, which is consistent with the observed reduced cytokine production (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Thus, we conclude that the disease-attenuating phenotype observed upon Ly6GPos cell depletion is directly attributable to loss of Ly6GPos granulocytic cells.

Neither granulocyte-derived IL10 nor MDSC activity contribute to disease in C3HeBFeJ or Nos2−/− mice.

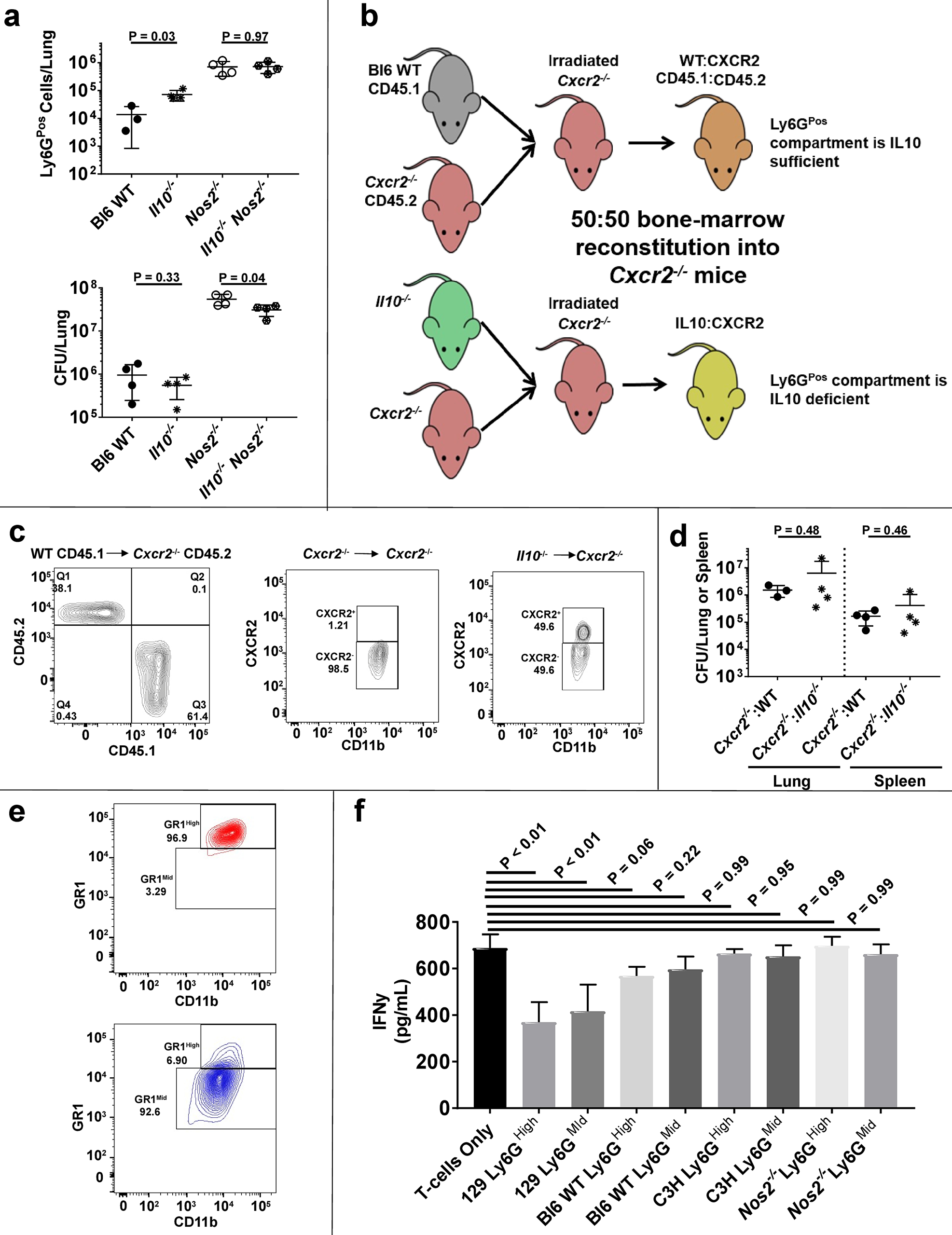

We next investigated whether IL10 secretion or MDSC activity played a role in promoting disease. Neutrophils from Mtb infected cynomolgus macaques can produce detectable levels of IL1025, suggesting a possible role for granulocyte-derived IL10 in TB, and Ly6GPos cell depletion within our murine models decreased the concentration of IL10 in the lungs of susceptible mouse strains (Supplementary Fig. 3b). However, deletion of the Il10 gene did not alter the number of pulmonary Ly6GPos cells in susceptible Nos2−/− animals, and caused only a minimal decrease in bacterial burden (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. Neither granulocyte-derived IL10 nor MDSC activity contribute to disease in C3HeBFeJ or Nos2−/− mice.

a Number of Ly6GPos cells (top) or CFUs (bottom) in the lungs of the indicated mouse strains at 28 days PI. b Schematic diagram of mouse chimerism to produce 50:50 WT:Cxcr2−/− mice (where the Ly6GPos compartment is IL10 sufficient) or 50:50 Il10−/−:Cxcr2−/− mice (where the Ly6GPos compartment is IL10 deficient). c Representative plots of CD11bHigh cells from peripheral blood verifying ~50:50 chimerism of WT (CD45.1Pos):Cxcr2−/− (CD45.2Pos) or Il10−/− (CXCR2Pos):Cxcr2−/− (CXCR2Neg). d CFUs recovered from the lungs or spleen of AG-treated chimeric or control mice at 28 days PI. e Representative plots of CD11bHigh Ly6GPos cells recovered from infected Nos2−/− mice, using the Miltenyi MDSC isolation kit, verifying the isolation of subpopulations via GR1 expression. f Total IFNγ production by activated T-cells co-cultured at a 1:1 ratio over 24 hours with Ly6GHigh or Ly6GMid cells of the indicated genotype recovered at 28 days PI. N = 4 mice per group and error bars represent standard deviation between these biological replicates. Statistical values based on one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison analysis.

To specifically probe the antimicrobial impact of granulocyte-derived IL10 in the lungs, we took advantage of the requirement for C-X-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 2 (CXCR2) in neutrophil recruitment to the pulmonary compartment6,10,22. Even upon AG treatment, we found that, like Genista mice, Cxcr2−/− mice were defective in Ly6GPos cell recruitment to the lungs and harbored fewer bacteria than WT controls (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Using this model, we constructed 50:50 Il10−/−:Cxcr2−/− bone-marrow chimeric mice where CXCR2 expression within the granulocyte compartment was restricted to IL10-deficient cells, and thus only those IL10-deficient Ly6GPos granulocytes could traffic to the lungs (Fig. 3b–c). Upon Mtb infection, we observed no difference in CFU load between animals with IL10-deficient or IL10-sufficent Ly6GPos cells (Fig. 3d), even when granulocyte recruitment was augmented by AG treatment. Together, these data indicated that Ly6GPos cells may contribute to total IL10 levels in the lungs, but their IL10 production does not play a significant role in controlling antimicrobial immunity in this model.

We next isolated myeloid cell subsets from Mtb-infected mouse lungs to assess their MDSC functionality. These experiments specifically tested the hypothesis that Ly6GMid granulocytes, which resemble cells associated with MDSC activity in 129SvPas mice27, exacerbate disease by suppressing T-cell function in our models. We observed that Ly6GMid granulocytes from susceptible C3HebFeJ and Nos2−/− mice express inconsistent levels of MDSC markers, with overall lower expression of CD47, CXCR4, CD49d, c-kit, and CD115, yet increased levels of CD124 compared to Ly6GHigh neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 3d–e). To determine if these cells express relevant regulatory activity, we performed T-cell suppression assays using isolated Ly6GHigh neutrophils or Ly6GMid granulocytes (Fig. 3e) from Bl6 WT, 129SvPas, C3HebFeJ, or Nos2−/− mice. Consistent with previous findings27, we observed significant suppression of IFNγ production from activated T-cells co-cultured with either Ly6GHigh or Ly6GMid cells from 129SvPas mice (Fig. 3f). In contrast, we observed no suppression from Bl6 WT, C3HebFeJ, or Nos2−/− cells (Fig. 3f). Thus, while functionally different subsets of granulocytes may infiltrate the lungs based on the root cause of susceptibility, MDSC-based T-cell suppression does not explain the disease promoting effect of Ly6GPos cells in C3HebFeJ and Nos2−/− mice.

Mtb preferentially associates with Ly6GPos cells during loss of immune containment.

Data to this point indicated that Ly6GPos cells promote bacterial replication without altering common markers of protective adaptive immunity. As a result, we hypothesized that the increased number of granulocytes in the lungs of susceptible animals instead confers a more favorable niche for Mtb replication. Consistent with this model, we previously found that the number of infected CD11bHigh Ly6GPos granulocytic cells exceeded infected monocytes/macrophages in Nos2−/− animals6. To further test this hypothesis, we quantified the number of bacteria in various niches, including myeloid cell subsets and extracellular sites, representing significant replicative sites in necrotic lesions.

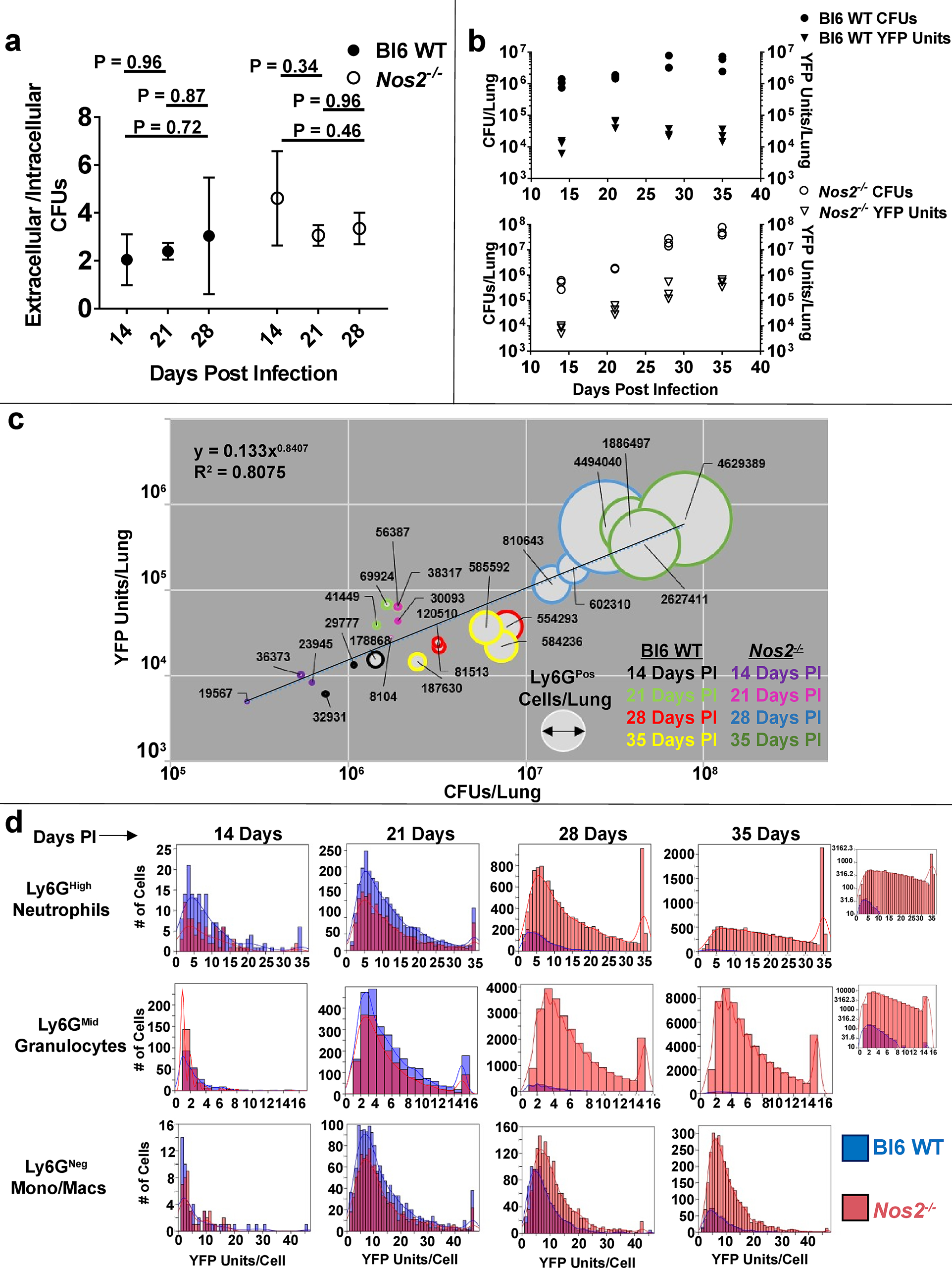

To estimate relative bacterial burden within intra- and extracellular niches, we developed an assay utilizing differential centrifugation and a cell-impermeable antibiotic to calculate extracellular, cell-associated, or intracellular Mtb fractions within the lungs (Supplementary Fig. 4a), concentrating on the extremes of susceptibility: Bl6 WT and Nos2-/−. We observed no difference in the number of intracellular bacteria compared to total cell-associated bacteria at 14, 21, or 28 days PI, indicating that the vast majority of cell-associated Mtb were internalized (Supplementary Fig. 4b). While we did observe a measurable population of extracellular bacteria, the proportion recovered from intra- and extracellular sites remained relatively constant over time (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4c). Thus, increased extracellular replication is unlikely to explain the excessive bacterial burden observed in Nos2−/− mice.

Figure 4. Mtb preferentially associates with Ly6GPos cells during loss of immune containment.

a Ratio of extracellular/intracellular CFUs recovered from the lungs of msfYFP-Mtb infected Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− mice at the indicated time points. Error bars represent standard deviation between mice within each group. Statistical values based on one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison analysis. b CFUs (circles, left Y-axis) or normalized YFP Units (triangles, right Y-axis) in the lungs of msfYFP-Mtb infected Bl6 WT (top) or Nos2−/− (bottom) mice at the indicated time points. Each data point represents 1 mouse. c YFP units (Y-Axis) as a function of CFUs (X-axis) and Ly6GPos cell number (width of circles with numerical label) in the lungs of infected Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− mice. Time points are indicated by coloring. “R2” indicates the correlation coefficient for the fitted line. d Number of YFP Units per cell in msfYFP-Mtb associated CD11bHigh Ly6GHigh, CD11bHigh Ly6GMid, or CD11bHigh Ly6GNeg cells from Bl6 WT (blue bars) or Nos2−/− (pink bars) mice at the indicated timepoints. Inset: YFP Units per cell within Ly6GHigh or Ly6GMid compartments at 35 days PI, graphed on a log Y-axis for ease of visualization. N = 3 mice per group per time point, or 3 mice per group per bar graph.

To assess bacterial load within distinct myeloid subsets, we developed a flow cytometry assay to quantify the number of bacteria per cell using a fluorescent msfYFP-expressing strain of Mtb6. The calculated YFP signal per cell (YFP Units) correlated with recovered CFUs from lungs over time (Fig. 4b), and thus served as a proxy for measuring bacterial load within individual cells. Using this assay, we found a strong correlation between total bacterial numbers, duration of infection, and abundance of Ly6GPos cells in the lungs of B6 WT and Nos2−/− mice (Fig. 4c).

When we individually assessed the distribution of bacteria per cell within different myeloid classes, we found a clear difference between Ly6GPos and Ly6GNeg populations as disease progressed (Fig. 4d). During the first 21 days of infection, Nos2 had little effect on the cellular composition of the lung (Fig. 1b), and we observed only modest differences in the distribution of bacteria among the three cell classes (Ly6GHigh neutrophils, Ly6GMid granulocytes, and Ly6GNeg monocytes/macrophages) between Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− mice (Fig. 4d). However, the impact of Nos2 became apparent after 28 days. At this point, the total bacterial burden in Bl6 WT mice had stabilized as a result of the adaptive response (Fig. 4b), and this control was reflected in monocytes/macrophages where both the number of infected cells and bacteria per cell remained relatively consistent across both genotypes (Fig. 4d and Table 1). While the number of infected granulocytes, as well as the number of bacteria per granulocyte, decreased between 21 and 28 days PI in Bl6 WT mice, the opposite effect occurred in granulocytes within Nos2−/− mice. In the Nos2−/− background, the number of infected Ly6GHigh and Ly6GMid cells increased by 4.7- or 12.3-fold, respectively. The average number of bacteria per Ly6GPos granulocyte remained relatively constant, increasing by approximately 20% (Table 1-highlighted). These trends continued as disease progressed in Nos2−/− mice. By 35 days PI, the number of infected Ly6GNeg monocytes/macrophages had increased in Nos2−/− mice, but we observed the vast majority of the bacterial burden within Ly6GPos cells, most of which displayed the Ly6GMid phenotype (Fig. 4d). These data are consistent with a model in which the protective adaptive response preferentially restricts bacterial growth in Ly6GNeg monocytes/macrophages verses Ly6GPos granulocytic cells, and recruitment of these more permissive granulocytes promotes infection.

Table 1. Bacterial Burden within Myeloid Cell Populations from Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− Mice.

The average number of infected cells per lung, with the mean, median, range, and mode of the distribution YFP Units per cell represented for the indicated cell types and genotypes at 21 days or 28 days PI. % change represents the percent difference from 21 to 28 days PI of the indicated metric. N = 3 mice per genotype per time point.

| 21 Days PI | 28 Days PI | % Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bl6 WT Ly6G High Neutrophils | |||

| Average Bacteria per Cell | 12 | 7 | −42 |

| Median of the Distribution | 9 | 5 | −44 |

| Mode of the Distribution | 5 | 2 | −60 |

| Range of the Distribution | 1–36 | 1–36 | ~ |

| Average # infected Cells per Lung | 1100 | 520 | −53 |

| Bl6 WT Ly6G Mid Granulocytes | |||

| Average Bacteria per Cell | 5 | 4 | −20 |

| Median of the Distribution | 4 | 3 | −25 |

| Mode of the Distribution | 3 | 2 | −33 |

| Range of the Distribution | 1–15 | 1–15 | ~ |

| Average # infected Cells per Lung | 900 | 350 | −61 |

| Bl6 WT Ly6G Neg Mono/Macs | |||

| Average Bacteria per Cell | 13 | 9 | −31 |

| Median of the Distribution | 10 | 7 | −30 |

| Mode of the Distribution | 4 | 3 | −25 |

| Range of the Distribution | 1–47 | 1–46 | ~ |

| Average # infected Cells per Lung | 490 | 330 | −33 |

| Nos2−/− Ly6G High Neutrophils | |||

| Average Bacteria per Cell | 12 | 14 | 17 |

| Median of the Distribution | 9 | 11 | 22 |

| Mode of the Distribution | 4 | 35 | 775 |

| Range of the Distribution | 1–35 | 1–35 | ~ |

| Average # infected Cells per Lung | 700 | 4000 | 471 |

| Nos2−/− Ly6G Mid Granulocytes | |||

| Average Bacteria per Cell | 5 | 6 | 20 |

| Median of the Distribution | 4 | 5 | 25 |

| Mode of the Distribution | 2 | 3 | 50 |

| Range of the Distribution | 1–15 | 1–15 | 0 |

| Average # infected Cells per Lung | 660 | 8800 | 1233 |

| Nos2−/− Ly6G Neg Mono/Macs | |||

| Average Bacteria per Cell | 13 | 12 | −8 |

| Median of the Distribution | 10 | 9 | −10 |

| Mode of the Distribution | 8 | 6 | −25 |

| Range of the Distribution | 1–47 | 1–43 | ~ |

| Average # infected Cells per Lung | 345 | 560 | 62 |

Ly6GMid granulocytes are retained in the lungs at least as long as monocytes and macrophages.

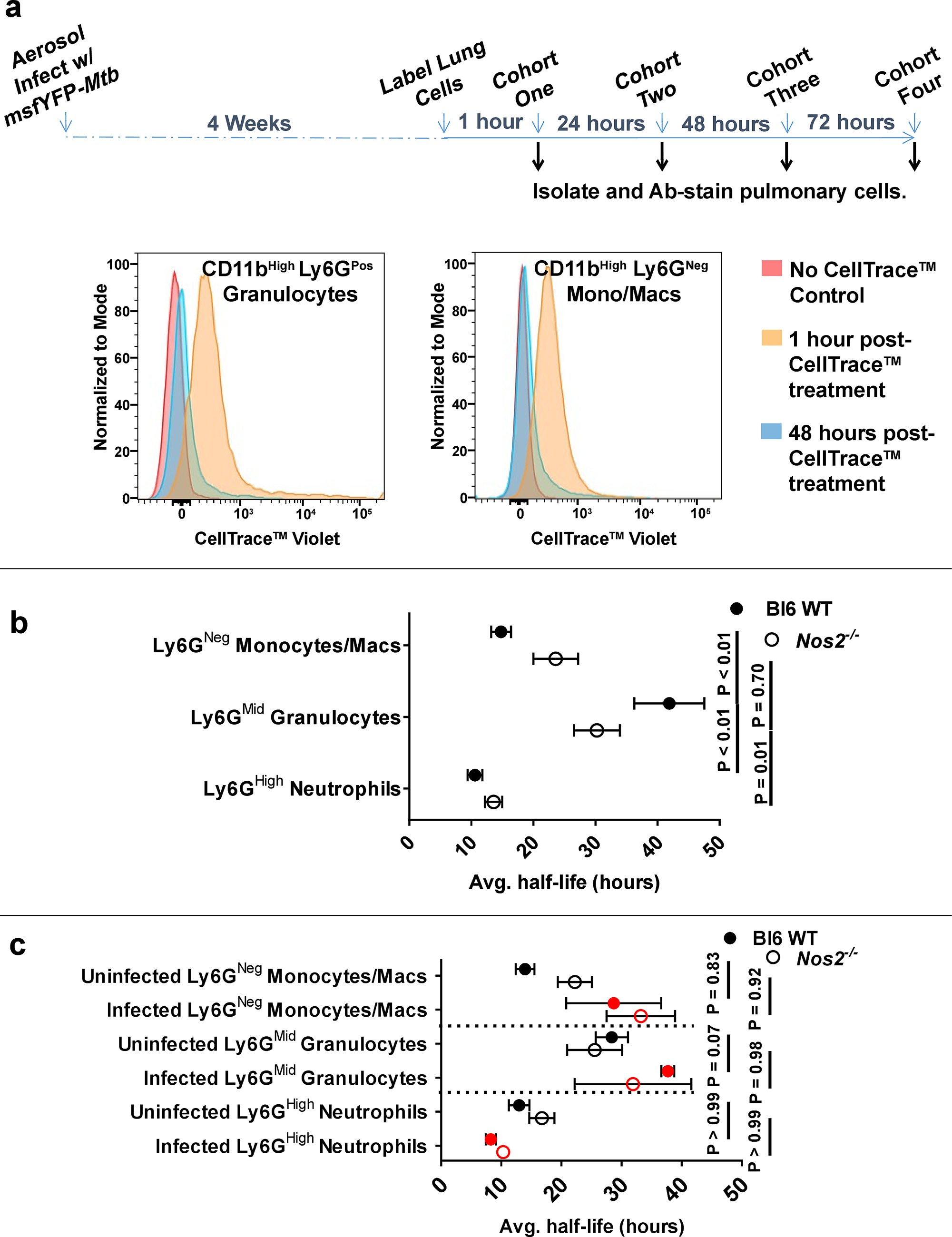

Mtb is canonically thought to replicate in relatively long-lived myeloid cells. The lifespan of myeloid cell populations can be highly variable, dependent on activation status, sub-lineage, tissue residence, and disease-specific regulation34. Within Mtb-infected lungs, the lifespan of monocytic phagocytes, which are canonically considered a niche for Mtb, relative to granulocytic cells has never been assessed. To address this, we developed an assay to calculate the half-life of pulmonary myeloid cells in vivo (Fig. 5a). One hour after instillation of a nonspecific fluorescent cell stain via intratracheal aspiration, approximately 60% of all viable lung cells stained positive by flow cytometry (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 5a). Analysis of spleens verified that the dye does not escape the pulmonary compartment (Supplementary Fig. 5b), and analysis of long-lived pulmonary CD19Pos B-cells indicated stain retention up to at least 48 hours post-treatment (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Based on the average number of stain-positive cells at 1-hour post-treatment versus 48-hours post-treatment, the calculated half-life of pulmonary bulk Ly6GNeg monocytes/macrophages, Ly6GMid granulocytes, and Ly6GHigh neutrophils from either Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− mice at 28 days PI was 22±8 hours, 40±10 hours, and 12±2 hours, respectively (Fig. 5b). Using the msfYFP-Mtb strain, we found the half-life of infected and uninfected cells was similar within cell types, and host genotype had a relatively modest effect (Fig. 5c), suggesting that differences between cellular life spans are intrinsic to the cell type and not strongly influenced by inflammatory state of the organ or direct effects of the bacterium. These collective data indicate that certain Ly6GPos populations, specifically Ly6GMid cells, have a lifespan exceeding that of canonical monocyte/macrophage compartments for intracellular Mtb replication. These findings are thus consistent with a model in which Mtb utilizes Ly6GPos cells as a replicative niche for intracellular growth.

Figure 5. Ly6GMid granulocytes are retained in the lungs at least as long as monocytes/macrophages.

a Schematic of in vivo pulmonary cell half-life assay (top) and representative histogram overlays (bottom) of Bl6 WT pulmonary CD11bHigh Ly6GPos cells or CD11bHigh Ly6GNeg monocytes/macs left untreated (red) or stained with CellTrace™ Violet via tracheal aspiration and measured at 1 hour (gold) or 48 hours (blue) post-labeling. b Mean half-life of total or c infected YFPPos (red) vs uninfected YFPNeg (black) Ly6GNeg monocytes/macrophages, Ly6GMid granulocytes, or Ly6GHigh neutrophils in the lungs of Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− mice. Error bars represent standard deviation between half-life values calculated from at least 3 separate pairs of biological replicates (mice). N = 3 mice per genotype per time-point post-treatment. Statistical values based on two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison analysis.

Gene expression profiling of Ly6GMid granulocytes indicates decreased antimicrobial function and proinflammatory effects.

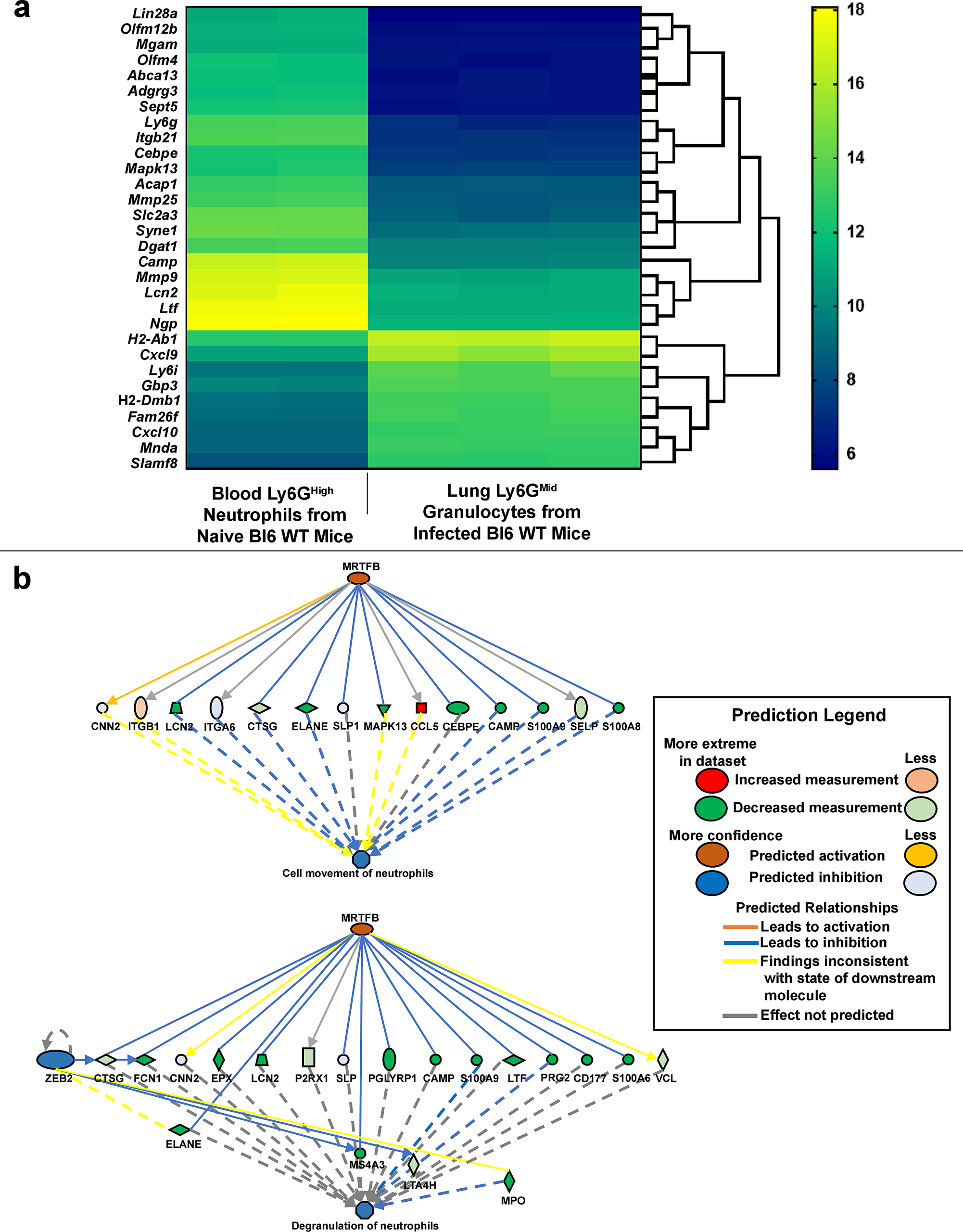

To further characterize the long-lived Ly6GMid cell subset, we performed RNAseq analysis. In steady-state, neutrophils fully differentiate in the bone-marrow before circulating in the blood35, and much of our understanding of neutrophil function comes from studying this mature cell type. Due to the well-documented heterogeneity within granulocyte populations35,36, we first contrasted gene expression differences between pulmonary Ly6GMid granulocytes from infected Bl6 WT mice and canonical Ly6GHigh peripheral blood neutrophils recovered from naïve Bl6 WT mice. Gene ontology analysis revealed significant differential expression of immune process genes between the two data sets. Of the top 30 most differentially expressed genes, Ly6GMid granulocytes expressed lower levels of genes with antimicrobial functions such as those regulating phagosome activity (Neutrophil Granule Protein (Ngp)37), sequestering iron (Lipocalin (Lcn2)38 and Lactoferrin (Ltf)39), direct killing of the bacterium (Cathelicidin Antimicrobial Protein (Camp)40), or regulating anti-mycobacterial properties (CCAAT Enhancer Binding Protein Epsilon (CEBP)7,41) (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Table 1). To better understand the physiological basis of these differences, we searched for potential upstream regulators that control these genes. This analysis predicted altered activity of Mrtfb, which encodes the MRTF-SRF transcriptional coactivator of serum response factor (Fig. 6b). MRTF-SRF has been identified as a regulator of hematopoiesis and neutrophil migration42, and our data suggest that Mrtfb may also coordinate granulocyte responses during Mtb infection.

Figure 6. Gene expression profile of Ly6GMid granulocytes indicates decreased antimicrobial function.

a Bi-clustering heatmap visualizing the expression profile of the top 30 most differentially expressed genes, as sorted by adjusted p-value via plotting the log2 transformed expression values in each sample. b Pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes predicting activation or inhibition of upstream regulators in relation to functional neutrophil migration (top) or degranulation (bottom). P value cutoff ≤ 0.01. Ly6GHigh peripheral blood neutrophils were recovered from uninfected Bl6 WT mice (N = 2). Ly6GMid granulocytes were recovered from Bl6 WT mouse lungs at 32 days post infection (N = 3).

To further define this granulocyte subpopulation relative to activated Ly6GHigh pulmonary neutrophils present during Mtb infection, we performed analyses as described above comparing Ly6GMid granulocytes to Ly6GHigh neutrophils recovered from the lungs of Mtb-infected Nos2−/− mice, where both subsets are prevalent. Many of the top 30 most differentially expressed genes were chemotactic factors such as Ccr2 and Ccl4, which encode C-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 2 and C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 4, respectively, and inflammatory regulators such as Ltb, Csf1, and Igf1r, which encode Lymphotoxin Beta, Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor 1, and Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Receptor, respectively (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 2). Consistent with our experimental evidence demonstrating that lung granulocytes contribute to inflammatory cytokine production (Supplementary Fig. 3a), pathway analysis elucidating potential regulatory networks revealed that Ly6GMid granulocytes exhibit an expression pattern predicted to promote inflammation (Fig. 7b). Taken together, our data suggest that Ly6GMid granulocytes represent a granulocyte subclass that is less antimicrobial and more inflammatory than Ly6GHigh neutrophils.

Figure 7. Gene expression of Nos2−/− Ly6GMid granulocytes compared to Nos2−/− Ly6GHigh neutrophils indicates differential inflammatory signaling.

a Bi-clustering heatmap visualizing the expression profile of the top 30 most differentially expressed genes, as sorted by adjusted p-value via plotting the log2 transformed expression values in each sample between of Nos2−/− Ly6GMid vs to Nos2−/− Ly6GHigh lung cells. b Differentially expressed genes were significantly enriched in the depicted inflammatory signaling pathway. P value cutoff ≤ 0.01. Cells were collected from mouse lungs at 32 days PI. N = 3 mice per group.

Discussion

While granulocyte influx is a hallmark of pulmonary TB1, the disease-impacting roles of these cells are still being elucidated. Ly6GPos granulocytic cells are now recognized as a heterogeneous population capable of differential signaling, regulatory, and antimicrobial functions27,35,36. In this work, we investigated the phenotype and role of these cells in Mtb-susceptible mouse strains. Our data indicate that Ly6GPos cells directly promote bacterial replication and can serve as a primary niche for Mtb in susceptible hosts. Several lines of evidence, summarized below, support a model in which the recruitment of granulocytes, a Ly6GMid subpopulation in particular, provides a favorable site for Mtb replication.

Granulocyte depletion ameliorates disease in multiple models of TB susceptibility without perturbing other aspects of the immune response. While the anti-Ly6G cell-depleting antibody 1A8 is a common tool for the study of these cells in mice6,2, the mechanism(s) by which depletion occurs remain(s) obscure43, and potential off-target effects can cloud experimental conclusions. The Genista mouse model offers a genetic alternative to antibody-mediated depletion that is maintained throughout infection yet still specific to Ly6GPos cells33. We utilized both models to verify that removal of Ly6GPos cells from susceptible mice reduced Mtb growth without altering adaptive immunity. These data indicate that Ly6GPos cells directly promote Mtb growth.

Known immunomodulatory functions of neutrophils did not influence TB progression in the models used in this study. Previous reports have found granulocytic MDSCs can contribute to disease through suppression of T-cell antimicrobial activity in 129SvPas mice27,28. While we also detected suppressive activity in 129SvPas granulocytes, this effect was not generalizable to Bl6 WT, C3HeBFeJ, or Nos2−/− mice. This difference was particularly surprising for 129SvPas and C3HeBFeJ mice, as susceptibility in both settings is due to a type I IFN response. We conclude that suppressive functionality depends on genetic background, but is not required for granulocytes to promote mycobacterial replication.

The apparently direct effect of granulocytes on bacterial burden and lack of obvious immunoregulatory activity suggested that granulocyte recruitment instead produced a more favorable replicative niche. Consistent with this hypothesis, the adaptive immune response in the Nos2−/− background was capable of at least transiently controlling bacterial burden in monocytes/macrophages, but not in Ly6GPos cells (Fig 4d). As disease progressed, the Ly6GMid subpopulation became the most abundant infected granulocyte, suggesting a particularly important role for these cells once immune containment is lost. In other contexts, Ly6GMid granulocytes have been described as immature neutrophils44. Using known markers of maturation, such as CD49d, c-kit, CD35, CD64, and IFNγR (Supplementary Fig. 3e and data not shown)45–47, we were unable to define these cells as specific neutrophil precursors. Similarly, we previously observed a heterogeneous cytological appearance of these cells, and only a fraction had a clear polymorphonuclear morphology6. This heterogeneity is mimicked in human disease, where conflicting reports of neutrophil function obscure a singular defined role for these cells during Mtb infection36. Of note, our observations in mice correlate with the reported accumulation of low-density granulocytes (LDGs) in patients with active TB48. This as-of-yet poorly characterized granulocyte subpopulation increases in frequency with TB disease severity48, and could represent a human analog to the Ly6GMid cells described in our models. While heterogeneity complicates precise characterization of granulocyte subsets, our data indicate that Ly6GMid cells are abundant in susceptible mice, possess a lifespan at least as long as macrophages, poorly express MRTF-SRF-dependent antimicrobial genes, and become a major bacterial reservoir even in the context of an immune response capable of controlling Mtb in macrophages.

These data contribute to growing evidence of dysregulated granulocyte recruitment directly contributing to mycobacterial replication and TB6,23,41,50,5. The accumulation of granulocytes within multiple distinct murine models of susceptibility, along with neutrophil-associated transcriptional signatures predicting TB progression in humans19–21, suggest a process representing a common pathway of disease progression downstream of distinct initiation events. As such, interrupting this process may represent a more promising interventional strategy than those targeting upstream mediators.

Materials and Methods

Mice and infections

Wild-type, Nos2−/−, IL10−/−, Cxcr2−/−, and CD45.1+/+ (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ) mice on the C57Bl6 background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), as were C3HeBFeJ mice. C57Bl6 Genista mice were a gift from Bernard Malissen at Aix-Marseille Université. 129SvPas mice were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions, in accordance with UMMS IACUC guidelines. Infections were carried out using PDIM-positive Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv cultured in 7H9 medium containing 0.05% Tween 80 and OADC enrichment (Becton Dickinson/BD-Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Yellow fluorescent protein (msfYFP) expressing H37Rv were generated by transformation with plasmid PMV261, which constitutively expresses msfYFP under control of the hsp60 promoter. Murine aerosol infections of ~200 CFUs were carried out as described by Mishra et al6. All mice were at least 6 weeks of age, and were sex and age matched within individual experiments.

Flow Cytometry

Single cell suspensions were prepared as described previously6. Briefly, whole lungs were homogenized via Miltenyi (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) GentleMACs dissociator in 5 mL RPMI plus Collagenase type IV/DNaseI, then strained through a 40 uM cell strainer. Analyses were performed on cells after 30 minutes staining at 4° C, using antibodies purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, California), and 20 minutes fixation using 4% paraformaldehyde or Cytoperm/Cytofix buffer (BD-Biosciences). For intracellular staining (ICS), fixed cells were further stained with the indicated fluorophore-conjugated ICS antibody or isotype control overnight at 4°C, then washed and analyzed. For infections with fluorescent H37Rv, lung tissue was prepared as above6, and compared against lung tissue from mice infected with non-fluorescent H37Rv.

Antibody-based cell depletion

Anti-Ly6G depleting antibody clone 1A8 or isotype control 2A3 (BioXcell, West Lebanon, NH) was administered as described by Nandi et al50. Ly6GPos cell depletion was verified by FACS analysis of CD11bHigh GR1Pos Ly6CNeg cell populations (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

MDSC suppression assay

Ly6GHigh or Ly6GMid cells were isolated from the lungs of WT C57BL6, Nos2−/−, C3HeBFeJ, or 129SvPas mice at 28 days PI using the Miltenyi MDSC Isolation Kit. P25 CD4Pos T-cells were pre-activated for 6 hours in complete media containing interleukin-2 and CD3/CD28 Dynabeads™ (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) following the manufacturer’s protocol, then incubated alone or in 1:1 co-culture with isolated granulocytes in 96-well plates (105 total cells/well) at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 hours. Culture supernatants were then removed, filter sterilized, and tested for total IFNγ by ELISA.

in vivo half-life assay

At 28 days PI, C57Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− mice were treated via tracheal aspiration with 40uL of 1mM CellTrace™ Violet dye (ThermoFisher Scientific) resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide. 1 hour post-treatment, a cohort from each genotype was euthanized, lungs harvested, and pulmonary tissue homogenized for Ab-staining. Subsequent cohorts were euthanized at 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours post-treatment (Fig. 5a). Spleens were harvested, homogenized, and Ab-stained to verify dye restriction to the pulmonary compartment. Half-life values for individual cell populations were calculated by quantifying the number of dyePos cells within mice of each cohort (relative to untreated controls) using a flow cytometer, then calculating the linear regression of dyePos cell ablation over time using the formula: ((Ln(2)*Z hours post-treatment)/(Ln(mean # of dyePos cells at 1 hour post-treatment/mean # of dyePos cells at Z hours post-treatment))). The calculated cell half-lives were averaged within each genotype and cohort (biological replicates for each time point = 3 mice per cohort per genotype, technical replicates for each time point = 9). Any mouse with < 10% of total cells dyePos was discarded. All calculations were determined using 1-, 24-, and 48-hour cohorts. No dye signal was observed at 72 hours post-treatment.

Analysis of YFP Unit distribution

Pulmonary cells from msfYFP-Mtb infected mice were recovered, stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above6. The YFP fluorescence value of each individual event (relative to background) within specified populations was exported into CSV format. For each YFPPos population within each mouse, the lowest recorded YFP fluorescence value above background was set equal to 1 YFP Unit. All subsequent YFPPos events within the population were divided by this lowest positive value to generate bins. Histograms were generated with FlowPy graphing software, plotting the number of YFPPos cells falling within each respective bin.

Sequencing and pathway analysis

~1.25 million Ly6GHigh or Ly6GMid cells were isolated from naïve mouse blood or Mtb infected mouse lungs using the Miltenyi MDSC Isolation Kit. RNA from cells in each test group was extracted, enriched for mRNA, fragmented, and randomly primed. First and second strand cDNA was synthesized and end-repaired by 5’ phosphorylation and 3’ dA-tailing. Adapters were ligated onto the cDNA fragments, which were then PCR enriched and sequenced via Illumina (San Diego, California) HiSeq, PE 2×150. Resulting reads were trimmed to remove possible adaptor sequence contamination and nucleotides with poor quality were discarded using Trimmomatic v.036. Trimmed reads were mapped to the Mus musculus GRCm28 reference genome using STAR aligner v.205.2b. Unique gene hit counts were calculated using featureCounts from the Subread package v.1.5.2, counting only those unique reads that fell within exon regions. Gene hit counts between test groups were compared using DESeq2. The Wald test generated p-values and log2 fold changes, with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change > 1 defining differentially expressed genes between comparisons. Predictive pathway analysis was performed using Quigen (Hilden, Germany) Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software, which compared significantly different –log2 gene expression values between test groups.

Isolation of intracellular and extracellular Mtb

Lungs from C57Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− mice were harvested at 14, 21, or 28 days post Mtb infection and mechanically homogenized with a Miltenyi GentleMACs dissociator. An aliquot of homogenate was plated in serial dilutions to determine total bacterial load, while the remainder was resuspended in PBS-T plus 70mM sucrose and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min to pellet mammalian cells. An aliquot of supernatant was plated to quantify extracellular bacteria unassociated with mammalian cells. The remaining supernatant was treated with 50 ug/mL gentamicin for 20 min, then plated as a control for antibiotic killing of non-cell associated bacteria and the potential for non-pelleted mammalian cell contaminants. The cell pellet was resuspended in serum-free media and an aliquot was plated to quantify total cell-associated bacteria. The remaining cell pellet was halved. One-half was treated with gentamicin, as above, then washed 2X with cold PBS and lysed in 0.1% Triton-X 100. Lysate was plated to quantify intracellular bacteria. The other half of the cell pellet was lysed as above, then treated with gentamicin and plated as a control for antibiotic killing of cell-associated bacteria. The sum of recovered extracellular CFUs plus total cell associated CFUs was compared against the total CFUs recovered from homogenate (prior to centrifugation) to verify that both intracellular and extracellular fractions were accounted for within each mouse (Supplementary Fig. 4a).

Generation of mixed bone marrow chimera mice.

B6.129S2(C)-Cxcr2tm1Mwm/J (CD45.2+/+) mice were lethally irradiated with two doses of 600 rads. The following day, bone marrow from CD45.1+/+ WT mice, CD45.2+/+ Cxcr2−/− mice, or CD45.2+/+ IL10−/− mice was isolated, red blood cells were lysed using Tris-buffered Ammonium Chloride (ACT), and remaining cells were quantified using a hemocytometer. CD45.1+/+ WT cells and CD45.2+/+ Cxcr2−/− cells, or, Il10−/− cells and Cxcr2−/− cells, were mixed equally at a 1:1 ratio. 107 cells from each respective mixture were then injected intravenously into separate lethally irradiated hosts (Fig. 3b). Reconstitution of host mice lasted 6–8 weeks with preventative sulfatrim treatment for the first 4 weeks. 50:50 chimerism was confirmed by bleeding reconstituted hosts, lysing red blood cells with ACT, and staining for CD11bHigh blood myelocytes for expression of CD45.1, CD45.2, or CXCR2 (Fig. 3c).

Cytokine measurements

Murine cytokine concentrations in filter sterilized lung tissue lysate were quantified using commercial BD OptEIA ELISA kits or Eve Technologies (Calgary, AB Canada) 32-Plex Discovery Assay. All samples were normalized for total protein content.

Isolation of Ly6GPos cells from mouse lungs

Ly6GHigh cells or Ly6GMid were isolated from WT C57BL6J, Nos2−/−, C3H3bFeJ, or 129SvPas mouse lung homogenates using the MDSC Isolation Kit from Miltenyi Biotec. Purity of Ly6GPos cell populations was tested by counterstaining with fluorophore-conjugated anti-GR1 (Clone RB6–8C5, Biolegend) and analyzing with a flow cytometer.

Aminoguanidine treatment of animals

Mice were treated ad libitum with 2.5% aminoguanidine over the course of infection as described previously6, with an additional biweekly intraperitoneal injection of 500uL sterile water containing 2.5% aminoguanidine.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Identification of differential myeloid cell populations in the lungs during Mtb infection. Representative gating strategy using Nos2−/− mouse whole lung homogenate at 28 days PI. Gates identify live CD19Neg CD11bHigh Ly6GHigh GR1High Ly6CHigh neutrophils, live CD19Neg CD11bHigh Ly6GMid GR1Mid Ly6CHigh granulocytes, and live CD19Neg CD11bHigh Ly6GNeg GR1Mid Ly6C Mid/High monocytes/macrophages.

Supplementary Figure 2. Depletion of Ly6GPos cells does not impact the adaptive immune response to Mtb. a Representative scatterplot overlay of lung cells recovered from C3HebFeJ mice at 23 days PI, treated with 2A3 isotype control Ab (red) or 1A8 anti-Ly6G depleting Ab (blue). b Number of CD4Pos T-cells (top left), CD8Pos T-cells (top right), CD19Pos B-cells ( bottom) or, c number of IFNγPos CD4Pos T-cells (left), amount of intracellular IFNγ in CD4Pos T-cells (middle), total IFNγ secretion (right) or, d number of FoxP3Pos CD4Pos T-regs (top left), amount of intracellular IL10 in FoxP3Pos CD4Pos T-regs (top right), number of T-betPos CD4Pos T-cells (bottom left), or expression of T-bet in CD4Pos T-cells (bottom right) in the lungs of Bl6 WT or Nos2-/- mice at 25 days PI when treated with anti-Ly6G (1A8) or isotype (2A3). N = 4 mice per group and error bars represent standard deviation between biological replicates within each group. Statistical values based on unpaired Student’s T-test.

Supplementary Figure 3. Ly6GPos cell ablation impacts cytokine production during Mtb infection. a Multiplex analysis of the indicated cytokines and chemokines in the lungs of Bl6 WT, C3HebFeJ, or Nos2−/− mice at 25 days PI after treatment with anti-ly6G cell depleting antibody (1A8) or isogenic control (2A3). Heatmap represents average pg/mL of detected cytokine from 3–4 mice per group scaled by row. Hierarchical clustering of treatment groups based on average linkage with Pearson correlation. b IL10 production as determined by ELISA in the lungs of Bl6 WT, C3HebFeJ, or Nos2−/− mice at 25 days PI after treatment with 1A8 or 2A3. N = 4 mice per group. Statistical values based on unpaired Student’s T-test. c Number of CFUs (left) or Ly6GPos cells (right) recovered from the lungs of Bl6 WT, Cxcr2−/−, or Genista mice at 28 days PI, treated with or without aminoguanidine (AG) as indicated. d Expression of CD115 (top) or CD124 (bottom) on lung CD11bHigh Ly6GHigh neutrophils or CD11bHigh Ly6GMid granulocytes of the indicated genotype at 28 days PI. e Expression the indicated MDSC markers on lung CD11bHigh Ly6GHigh neutrophils or CD11bHigh Ly6GMid granulocytes recovered from Bl6 WT (top) or Nos2−/− (bottom) mice at 28 days PI. N = 4 mice per group. Statistical values based on unpaired Student’s T-test for single comparisons or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison analysis for multiple comparisons. All error bars represent standard deviation between mouse replicates within the indicated group.

Supplementary Figure 4. CFU quantification of Mtb growth compartments within the lungs of infected mice. a Schematic of lung fractionation protocol (left) with corresponding CFU quantification (right) from Nos2−/− mice at 28 days PI. Protocol steps and the corresponding CFUs recovered at each step are numerically labeled. b Number of total cell-associated bacteria compared to intracellular bacteria or, c number of non-cell-associated, cell-associated, or total bacteria recovered from the lungs of Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− mice at the indicated time points. N = 3 mice per time-point per genotype and error bars represent standard deviation between biological replicates within each group.

Supplementary Figure 5. CellTraceTM dye instilled into the lungs of infected mice remains in the pulmonary compartment. a Representative scatter plots of Bl6 WT pulmonary CD11bHigh Ly6GPos cells or CD11bHigh Ly6GNeg monocytes/macs left untreated or stained with CellTrace™ Violet via tracheal aspiration at 1 hour post-labeling. b Overlaid histograms of live splenocytes from unlabeled control mice (red), CellTrace™ Violet-labeled Bl6 WT mice (gold), or CellTrace™ Violet-labeled Nos2−/− mice (blue) 1 hour post-treatment. c Overlaid histograms of total live CD19Pos B-cells (top) and number of CellTrace™ VioletPos CD19Pos B-cells (bottom) in the lungs of Bl6 WT mice at 1 hour post-staining (red) or 48 hours post-staining (blue). N = 4 mice per group and error bars represent standard deviation between biological replicates within each group. Statistical value calculated by Student’s T-test. CellTrace™ treatment began at 28 days PI.

Supplementary Table 1. Gene Expression of Peripheral Blood Ly6GHigh Neutrophils recovered from Naïve Bl6 WT Mice or Lung Ly6GMid Granulocytes recovered from Infected Bl6 WT Mice. Normalized read counts from cells recovered from each mouse are listed for every gene that was significantly differentially expressed (p value < 0.05) between the two conditions, as well as the log2-fold change in expression and the adjusted p value. Cells harvested from infected mice were isolated at 27 days PI.

Supplementary Table 2. Gene Expression of Lung Ly6GHigh Neutrophils recovered from Infected Nos2−/− Mice or Lung Ly6GMid Granulocytes recovered from Infected Nos2−/− Mice. Normalized read counts from cells recovered from each mouse are listed for every gene that was significantly differentially expressed (p value < 0.05) between the two conditions, as well as the log2-fold change in expression and the adjusted p value. Cells were isolated at 27 days PI.

Acknowledgments.

Genista mice were a kind gift from Bernard Malissen at Aix-Marseille Université. We thank Dr. Hardy Kornfeld, Dr. Nuria Martinez, and Dr. Samuel Behar for conceptual discussions; Charlotte Reames, Michael Kiritsy, Michelle Bellerose, Caitlin Moss, Dr. Jason Yang, Dr. Lisa Lojek, Dr. Andrew Olive, and Kadamba Papavinasasundaram for technical assistance; and the biosafety level 3 and the flow cytometry core facilities at UMMS.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants to C.M.S. (AI32130) and to R.R.L. (F32AI120556).

Footnotes

Disclosure.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Pre-publication Disclosure of Data: Portions of this manuscript were publically presented at the Feb. 2015 Keystone Symposia on Tuberculosis in Santa Fe, New Mexico, at the Jul. 2016 Gordon Research Conference on Microbial Toxins and Pathogenicity in Waterville Valley, NH, and at the Jan. 2017 Keystone Symposia on Tuberculosis in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canetti G The Tubercle Bacillus in the Pulmonary Lesion of Man: Histobacteriology and Its Bearing on the Therapy of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. (Springer Publishing Company, 1955). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bustamante J, Boisson-Dupuis S, Abel L & Casanova JL Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease: Genetic, immunological, and clinical features of inborn errors of IFN-γ immunity. Semin. Immunol (2014).doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flynn JAL et al. An essential role for interferon γ in resistance to mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med 178, 2249–2254 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper AM et al. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon γ Gene-disrupted mice. J. Exp. Med 178, 2243–2247 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacMicking JD, Taylor GA & McKinney JD Immune Control of Tuberculosis by IFN-γ-inducible LRG-47. Science (80-. ). 302, 654–659 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mishra BB et al. Nitric oxide prevents a pathogen-permissive granulocytic inflammation during tuberculosis. Nat. Microbiol 2, 17072 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang G et al. Allele-Specific Induction of IL-1β Expression by C/EBPβ and PU.1 Contributes to Increased Tuberculosis Susceptibility. PLoS Pathog. 10, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayer-Barber KD & Yan B Clash of the Cytokine Titans: Counter-regulation of interleukin-1 and type i interferon-mediated inflammatory responses. Cell. Mol. Immunol 14, 22–35 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teles RMB et al. NIH Public Access. 339, 1448–1453 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorhoi A et al. Type I IFN signaling triggers immunopathology in tuberculosis-susceptible mice by modulating lung phagocyte dynamics. Eur. J. Immunol 44, 2380–2393 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manzanillo PS, Shiloh MU, Portnoy DA & Cox JS Mycobacterium tuberculosis activates the DNA-dependent cytosolic surveillance pathway within macrophages. Cell Host Microbe 11, 469–480 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manca C et al. Hypervirulent M. tuberculosis W/Beijing strains upregulate type I IFNs and increase expression of negative regulators of the Jak-Stat pathway. J. Interferon Cytokine Res 25, 694–701 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang G et al. A proline deletion in IFNAR1 impairs IFN-signaling and underlies increased resistance to tuberculosis in humans. Nat. Commun 9, 1–9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji DX et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist mediates type I interferon-driven susceptibility to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Micobiology (2019).doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0578-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong H et al. Distinct contributions of neutrophils and CCR2+ monocytes to pulmonary clearance of different Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Infect. Immun 83, 3418–3427 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garvy BA & Harmsen AG The importance of neutrophils in resistance to pneumococcal pneumonia in adult and neonatal mice. Inflammation 20, 499–512 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chao-Tsung LY et al. Neutrophils Exert Protection in the Early Tuberculosis Granuloma by Oxidative Killing of Mycobacteria Phagocytosed from Infected Macrophages. Cell Host Microbe 112, 301–312 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dallenga T & Schaible UE Neutrophils in tuberculosis--first line of defence or booster of disease and targets for host-directed therapy? Pathog. Dis 74, ftw012 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eum SY et al. Neutrophils are the predominant infected phagocytic cells in the airways of patients with active pulmonary TB. Chest 137, 122–128 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berry MPR et al. An interferon-inducible neutrophil-driven blood transcriptional signature in human tuberculosis. Nature 466, 973–977 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Q et al. Proteomic profiling for plasma biomarkers of tuberculosis progression. Mol. Med. Rep 18, 1551–1559 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nouailles G et al. CXCL5-secreting pulmonary epithelial cells drive destructive neutrophilic inflammation in tuberculosis. J. Clin. Invest 124, 1268–1282 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimmey JM et al. Unique role for ATG5 in neutrophil-mediated immunopathology during M. tuberculosis infection. Nature 528, 565–569 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruger P et al. Neutrophils: Between Host Defence, Immune Modulation, and Tissue Injury. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004651 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gideon HP, Phuah J, Junecko BA & Mattila JT Neutrophils express pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in granulomas from Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected cynomolgus macaques. Mucosal Immunol. 12, 1370–1381 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denis M & Ghadirian E IL-10 neutralization augments mouse resistance to systemic Mycobacterium avium infections. J. Immunol 151, 5425–5430 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knaul JK et al. Lung-residing myeloid-derived suppressors display dual functionality in murine pulmonary tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 190, 1053–1066 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsiganov EN et al. Gr-1 dim CD11b + Immature Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells but Not Neutrophils Are Markers of Lethal Tuberculosis Infection in Mice . J. Immunol (2014).doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magcwebeba T, Dorhoi A & Plessis N Du The emerging role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tuberculosis. Front. Immunol 10, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowe DM, Redford PS, Wilkinson RJ, O’Garra A & Martineau AR Neutrophils in tuberculosis: Friend or foe? Trends Immunol. 33, 14–25 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eruslanov EB et al. Neutrophil Responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection in Genetically Susceptible and Resistant Mice. Infect. Immun 73, 1744–1753 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marzo E et al. Damaging role of neutrophilic infiltration in a mouse model of progressive tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 94, 55–64 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ordoñez-Rueda D et al. A hypomorphic mutation in the Gfi1 transcriptional repressor results in a novel form of neutropenia. Eur. J. Immunol 42, 2395–2408 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janssen WJ, Bratton DL, Jakubzick CV & Henson PM Myeloid Cell Turnover and Clearance. Microbiol. Spectr 4, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garley M & Jabłońska E Heterogeneity Among Neutrophils. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz) 66, 21–30 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyadova IV Neutrophils in Tuberculosis: Heterogeneity Shapes the Way? Mediators Inflamm. 2017, 8619307 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jena P et al. Azurophil Granule Proteins Constitute the Major Mycobactericidal Proteins in Human Neutrophils and Enhance the Killing of Mycobacteria in Macrophages. PLoS One 7, 1–13 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saiga H et al. Lipocalin 2-Dependent Inhibition of Mycobacterial Growth in Alveolar Epithelium. J. Immunol 181, 8521–8527 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Actor JK Lactoferrin: A modulator for immunity against tuberculosis related granulomatous pathology. Mediators Inflamm 2015, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sonawane A et al. Cathelicidin is involved in the intracellular killing of mycobacteria in macrophages. Cell. Microbiol 13, 1601–1617 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, Nonnemacher MR & Wigdahl B CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins and the pathogenesis of retrovirus infection. Future Microbiol. 4, 299–321 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor A et al. SRF is required for neutrophil migration in response to inflammation. Blood 123, 3027–3036 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruhn KW, Dekitani K, Nielsen TB, Pantapalangkoor P & Spellberg B Ly6G-mediated depletion of neutrophils is dependent on macrophages. Results Immunol. 6, 5–7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deniset JF, Surewaard BG, Lee WY & Kubes P Splenic Ly6Ghigh mature and Ly6Gint immature neutrophils contribute to eradication of S. pneumoniae. J. Exp. Med 214, 1333 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elghetany MT Surface antigen changes during normal neutrophilic development: A critical review. Blood Cells, Mol. Dis 28, 260–274 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evrard M et al. Developmental Analysis of Bone Marrow Neutrophils Reveals Populations Specialized in Expansion, Trafficking, and Effector Functions. Immunity 48, 364–379 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacNamara KC et al. Infection-Induced Myelopoiesis during Intracellular Bacterial Infection Is Critically Dependent upon IFN-γ Signaling. J. Immunol 186, 1032–1043 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deng Y et al. Low-density granulocytes are elevated in mycobacterial infection and associated with the severity of tuberculosis. PLoS One 11, e0153567 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warren E, Teskey G & Venketaraman V Effector Mechanisms of Neutrophils within the Innate Immune System in Response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. J. Clin. Med 6, 1–9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nandi B & Behar SM Regulation of neutrophils by interferon-γ limits lung inflammation during tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med 208, 2251–2262 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Identification of differential myeloid cell populations in the lungs during Mtb infection. Representative gating strategy using Nos2−/− mouse whole lung homogenate at 28 days PI. Gates identify live CD19Neg CD11bHigh Ly6GHigh GR1High Ly6CHigh neutrophils, live CD19Neg CD11bHigh Ly6GMid GR1Mid Ly6CHigh granulocytes, and live CD19Neg CD11bHigh Ly6GNeg GR1Mid Ly6C Mid/High monocytes/macrophages.

Supplementary Figure 2. Depletion of Ly6GPos cells does not impact the adaptive immune response to Mtb. a Representative scatterplot overlay of lung cells recovered from C3HebFeJ mice at 23 days PI, treated with 2A3 isotype control Ab (red) or 1A8 anti-Ly6G depleting Ab (blue). b Number of CD4Pos T-cells (top left), CD8Pos T-cells (top right), CD19Pos B-cells ( bottom) or, c number of IFNγPos CD4Pos T-cells (left), amount of intracellular IFNγ in CD4Pos T-cells (middle), total IFNγ secretion (right) or, d number of FoxP3Pos CD4Pos T-regs (top left), amount of intracellular IL10 in FoxP3Pos CD4Pos T-regs (top right), number of T-betPos CD4Pos T-cells (bottom left), or expression of T-bet in CD4Pos T-cells (bottom right) in the lungs of Bl6 WT or Nos2-/- mice at 25 days PI when treated with anti-Ly6G (1A8) or isotype (2A3). N = 4 mice per group and error bars represent standard deviation between biological replicates within each group. Statistical values based on unpaired Student’s T-test.

Supplementary Figure 3. Ly6GPos cell ablation impacts cytokine production during Mtb infection. a Multiplex analysis of the indicated cytokines and chemokines in the lungs of Bl6 WT, C3HebFeJ, or Nos2−/− mice at 25 days PI after treatment with anti-ly6G cell depleting antibody (1A8) or isogenic control (2A3). Heatmap represents average pg/mL of detected cytokine from 3–4 mice per group scaled by row. Hierarchical clustering of treatment groups based on average linkage with Pearson correlation. b IL10 production as determined by ELISA in the lungs of Bl6 WT, C3HebFeJ, or Nos2−/− mice at 25 days PI after treatment with 1A8 or 2A3. N = 4 mice per group. Statistical values based on unpaired Student’s T-test. c Number of CFUs (left) or Ly6GPos cells (right) recovered from the lungs of Bl6 WT, Cxcr2−/−, or Genista mice at 28 days PI, treated with or without aminoguanidine (AG) as indicated. d Expression of CD115 (top) or CD124 (bottom) on lung CD11bHigh Ly6GHigh neutrophils or CD11bHigh Ly6GMid granulocytes of the indicated genotype at 28 days PI. e Expression the indicated MDSC markers on lung CD11bHigh Ly6GHigh neutrophils or CD11bHigh Ly6GMid granulocytes recovered from Bl6 WT (top) or Nos2−/− (bottom) mice at 28 days PI. N = 4 mice per group. Statistical values based on unpaired Student’s T-test for single comparisons or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison analysis for multiple comparisons. All error bars represent standard deviation between mouse replicates within the indicated group.

Supplementary Figure 4. CFU quantification of Mtb growth compartments within the lungs of infected mice. a Schematic of lung fractionation protocol (left) with corresponding CFU quantification (right) from Nos2−/− mice at 28 days PI. Protocol steps and the corresponding CFUs recovered at each step are numerically labeled. b Number of total cell-associated bacteria compared to intracellular bacteria or, c number of non-cell-associated, cell-associated, or total bacteria recovered from the lungs of Bl6 WT or Nos2−/− mice at the indicated time points. N = 3 mice per time-point per genotype and error bars represent standard deviation between biological replicates within each group.

Supplementary Figure 5. CellTraceTM dye instilled into the lungs of infected mice remains in the pulmonary compartment. a Representative scatter plots of Bl6 WT pulmonary CD11bHigh Ly6GPos cells or CD11bHigh Ly6GNeg monocytes/macs left untreated or stained with CellTrace™ Violet via tracheal aspiration at 1 hour post-labeling. b Overlaid histograms of live splenocytes from unlabeled control mice (red), CellTrace™ Violet-labeled Bl6 WT mice (gold), or CellTrace™ Violet-labeled Nos2−/− mice (blue) 1 hour post-treatment. c Overlaid histograms of total live CD19Pos B-cells (top) and number of CellTrace™ VioletPos CD19Pos B-cells (bottom) in the lungs of Bl6 WT mice at 1 hour post-staining (red) or 48 hours post-staining (blue). N = 4 mice per group and error bars represent standard deviation between biological replicates within each group. Statistical value calculated by Student’s T-test. CellTrace™ treatment began at 28 days PI.

Supplementary Table 1. Gene Expression of Peripheral Blood Ly6GHigh Neutrophils recovered from Naïve Bl6 WT Mice or Lung Ly6GMid Granulocytes recovered from Infected Bl6 WT Mice. Normalized read counts from cells recovered from each mouse are listed for every gene that was significantly differentially expressed (p value < 0.05) between the two conditions, as well as the log2-fold change in expression and the adjusted p value. Cells harvested from infected mice were isolated at 27 days PI.

Supplementary Table 2. Gene Expression of Lung Ly6GHigh Neutrophils recovered from Infected Nos2−/− Mice or Lung Ly6GMid Granulocytes recovered from Infected Nos2−/− Mice. Normalized read counts from cells recovered from each mouse are listed for every gene that was significantly differentially expressed (p value < 0.05) between the two conditions, as well as the log2-fold change in expression and the adjusted p value. Cells were isolated at 27 days PI.