Abstract

Cellular homeostasis requires adaption to environmental stress. In response to various environmental and genotoxic stresses, all cells produce dinucleoside polyphosphates (NpnNs), the best studied of which is diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A). Despite intensive investigation, the precise biological roles of these molecules have remained elusive. However, recent studies have elucidated distinct and specific signaling mechanisms for these nucleotides in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. This review summarizes these key discoveries and describes the mechanisms of Ap4A and Ap4N synthesis, the mediators of the cellular responses to increased intracellular levels of these molecules and the hydrolytic mechanisms required to maintain low levels in the absence of stress. The intracellular responses to dinucleotide accumulation are evaluated in the context of the “friend” and “foe” scenarios. The “friend (or alarmone) hypothesis” suggests that ApnN act as bona fide secondary messengers mediating responses to stress. In contrast, the “foe” hypothesis proposes that ApnN and other NpnN are produced by non-canonical enzymatic synthesis as a result of physiological and environmental stress in critically damaged cells but do not actively regulate mitigating signaling pathways. In addition, we will discuss potential target proteins, and critically assess new evidence supporting roles for ApnN in the regulation of gene expression, immune responses, DNA replication and DNA repair. The recent advances in the field have generated great interest as they have for the first time revealed some of the molecular mechanisms that mediate cellular responses to ApnN. Finally, areas for future research are discussed with possible but unproven roles for intracellular ApnN to encourage further research into the signaling networks that are regulated by these nucleotides.

Keywords: Ap4A, diadenosine, nucleotide signaling, DNA replication and genotoxic stress, mRNA caps, cGAS/STING, MITF

Introduction

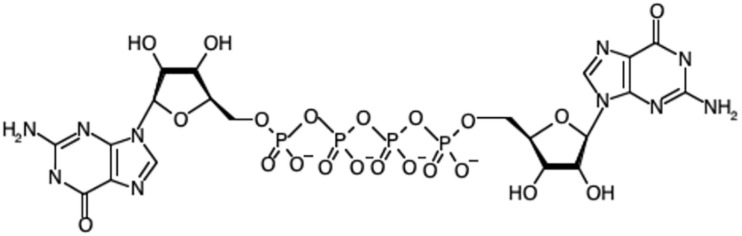

Diadenosine polyphosphates (ApnAs) are a class of nucleotide found in prokaryotes and eukaryotes (Kisselev et al., 1998; McLennan, 2000). They consist of two adenosine moieties linked by a polyphosphate chain containing typically 3–6 phosphates attached via phosphoester bonds to the respective 5′-OH groups (Figure 1). Since their initial discovery, roles for diadenosine polyphosphates (ApnA) and other dinucleoside polyphosphate species (NpnN, where N is uridine, cytosine, guanine or adenine and n is 3–6), have remained elusive in all Kingdoms of life. There has been debate surrounding the roles of these molecules for decades. However, their functional characterization has been limited due to the complexity of identifying specific interaction partners and this has led to the alternative proposal that Ap4A and other NpnN may simply be damage metabolites rather than intracellular signaling molecules. Dinucleoside polyphosphates are generated in response to stress, consistent with a stress-related function. Consequently, interest has mainly focused on trying to establish NpnN, particularly Ap4A and Ap4N, as signaling molecules, and in particular stress alarmones. The extracellular roles of Ap4N that includes their roles as extracellular messengers in the nervous, ocular and cardiovascular systems through activation of purinoceptors has been covered in detail elsewhere and will not be considered here (Jankowski et al., 2009).

FIGURE 1.

The chemical structure of diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A).

ApnNs Are Synthesized in Response to Physiological, Environmental, and Genotoxic Stress

Bacteria, protists, yeasts, invertebrates and mammals have mechanisms for the synthesis and hydrolysis of ApnN. The balance between synthesis and hydrolysis is required to maintain ApnN at a low level under normal conditions. However, ApnN levels increase in response to certain types of stress throughout all these domains of life. For example, in Salmonella typhimurium Ap4N levels increase in response to certain specific oxidative stresses, with Ap4A reaching a maximal concentration of 365 μM after 30 min of CdCl2 treatment compared to concentrations of <3 μM in cells undergoing non-oxidative stress (Bochner et al., 1984). Additionally, hyperthermic treatment is associated with membrane damage (Lepock, 1982) and this kind of treatment also increases dinucleoside polyphosphate levels. Increasing the temperature of S. typhimurium cells from 28 to 50°C resulted in an approximately 10-fold increase in Ap4A and Ap4G after 5 min, which then continued to increase (Lee et al., 1983). These early results were instrumental in the formulation of the alarmone hypothesis that Ap4A was an intracellular signal of molecular stress that orchestrated subsequent recovery mechanisms (Varshavsky, 1983). An increase in Ap4A and Ap4G levels was also identified in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 6301 exposed to 50°C, however, this increase was lower than that of Ap3A and Ap3G (Palfi et al., 1991). In both S. typhimurium and Synechococcus, the increase in nucleotides was dependent on the severity of the temperature change (Lee et al., 1983; Palfi et al., 1991). Treatment of S. typhimurium with 10% ethanol also resulted in an increase in Ap4A with levels rising from <5 μM to >50 μM over 50 min, but with less of an effect on Ap4G (Lee et al., 1983). In contrast, treatment of Synechococcus with 10% ethanol produced no effect, while treatment with heavy metal ions induced Ap4A accumulation to different extents dependent on the metal (Palfi et al., 1991). Ap4N levels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae also increased after treatment with cadmium acetate (Baltzinger et al., 1986). In Drosophila cells concentrations of 1 mM CdCl2 and above increased these nucleotides by over 100-fold, to 30 μM Ap4A and 39 μM Ap4G after 6 h of treatment (Brevet et al., 1985).

Similarly, oxidative stress induced by 0.1 mM dinitrophenol increased levels of Ap4A and Ap4G in the slime mold Physarum polycephalum by 3- to 7-fold (Garrison et al., 1986). Hypoxia also increased Ap4A and Ap4G levels by 6- to 7-fold within 40 min in P. polycephalum, an increase that rapidly declined in normoxic conditions (Garrison et al., 1989). Importantly, Ap4A levels in Escherichia coli increase 20-fold after kanamycin treatment, which generates hydroxyl radicals leading to oxidative stress (Ji et al., 2019). Aminoglycosides cause bacterial cell death by binding prokaryotic ribosomes and causing mistranslation of proteins that accumulate at the bacterial membrane, which promotes membrane permeabilization (Busse et al., 1992; Mingeot-Leclercq et al., 1999). The rise in Ap4A levels upon kanamycin treatment increases the effectiveness of aminoglycoside-induced bacterial cell death. As the use of aminoglycosides can be limited by their toxicity, combined therapy with an agent that increases intracellular Ap4A may offer a means to improve the potency of aminoglycosides at lower doses (Ji et al., 2019).

Thermal shock also promotes accumulation of Ap4A in yeast, plants and mammalian cells. Single cell eukaryotes such as S. cerevisiae demonstrated a response to heat shock at 46°C with basal Ap4N levels of approximately 0.08 μM increasing 50-fold (Baltzinger et al., 1986). However, the authors concluded that such increases were always associated with irreversible processes leading to cell death, thus giving early support to the damage metabolite hypothesis. Heat-shock from 19 to 37°C also induced a 2.2 to 3.3-fold increase in Ap4A and other ApnN in Drosophila cells (Brevet et al., 1985). Thermal stress also increases Ap4A levels in mammalian cells. Simian virus 40-transformed mouse 3T3 mammalian cells exposed to hyperthermic treatment for 30 min produced elevated ApnN levels 1 h after treatment, >90% of which were shown to be Ap4A (Baker and Jacobson, 1986). Ethanol, cadmium and arsenite treatment also increased ApnN (Baker and Jacobson, 1986). Again, however, evidence was also presented that significant heat-induced Ap4N increases in Xenopus oocytes and HTC hepatoma cells are associated with cell death (Guédon et al., 1986).

There is also considerable evidence that Ap4N are produced is response to genotoxic stress, including to agents causing DNA single-stranded breaks, although not necessarily at physiologically relevant doses. For example, N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG), bleomycin, nitroquinoline-1-oxide (4NQO) and UV irradiation all increased Ap4N several-fold in human fibroblasts. Co-administration of cytosine arabinoside with 4NQO and UV irradiation significantly increased their otherwise modest effect by inhibiting nucleotide excision repair and causing subsequent replication stress (Baker and Ames, 1988). Similar observations were made with MNNG in HTC hepatoma cells with the increase in Ap4N being greater and more prolonged in the presence of the PARP inhibitor 3-aminobenzamide (Gilson et al., 1988). Inter-strand crosslinking agents are highly effective and unlike many other types of genotoxic agents, induce Ap4A at physiologically relevant doses. Mitomycin C at a level that caused no growth inhibition (100 nM) increased Ap4A levels 7 to 8-fold in HeLa and Chinese hamster AA8 cells, and 9-fold in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) while 10 μM 1,2,3,4-diepoxybutane caused a 3-fold increase in AA8 cells (Marriott et al., 2015). Cells depleted of certain DNA repair proteins including XRCC1, aprataxin, PARP1 and FANCG also showed increases in Ap4N up to 14-fold with mitomycin C treatment enhancing these increases several-fold more. All these observations are indicative of the increases in Ap4N being mediated by DNA damage that prevents replication fork progression, such as that efficiently induced by ICL agents. Intriguingly, inactivation of the NUDT2 Ap4A hydrolase in KBM-7 CML cells, that leads to a 175-fold increase in intracellular Ap4A (Marriott et al., 2016). Interestingly, a significant portion of the damage-induced Ap4A in AA8 cells and its XRCC1-deficient EM9 derivative by mitomycin C was mono- and di-ADP-ribosylated. No increase in diadenosine triphosphate (Ap3A) was found. Cells treated in this way showed near full viability, indicating that the increases in Ap4N were not due to irreversible cell death, but could be a functional response to genotoxic damage (Marriott et al., 2015). Regardless of the severity of stress required to elicit increased levels of Ap4N, stress-induced increases do not by themselves indicate a true alarmone or secondary messenger function. Ideally, signaling molecules should have specific and regulated mechanisms of synthesis and degradation. The synthesis of the signal molecule should increase in response to stimuli, leading to interactions with specific downstream targets such as transcription factors or allosteric binding proteins that mediate a cellular response to the stress. Importantly, the effect of the signaling molecules should be reversible once the stimulus ceases. Each of these criteria are met for Ap4N and Ap4A in specific contexts and will be explored further below.

Mechanisms of Ap4N Synthesis

Ap4Ns are synthesized by non-canonical activities of certain enzymes that often involve an acyl-adenylate and/or enzyme-adenylate intermediate, and this non-canonical activity is often enhanced during stress responses (Table 1). Ap4A was first discovered in the 1960s as a product of the reaction between ATP and lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LysRS) in the presence of L-lysine (Zamecnik et al., 1966). Ap4A and other ApnNs were later found to be synthesized by several members of the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase family in a reversible process involving synthesis of an aminoacyladenylate intermediate followed by reaction with an acceptor such as ATP or NTP/NDP (Goerlich et al., 1982; Brevet et al., 1989). Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase-mediated production of Ap4A occurs both during normal cell growth and at times of stress, and for certain synthetases is stimulated by Zn2+ ions (Plateau and Blanquet, 1982; Brevet et al., 1989). Later an additional amino acid-independent mechanism of Ap4A synthesis involving the direct condensation of two ATPs by glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GlyRS) was identified. In this mechanism the first ATP binds to a site conserved in all class II tRNA synthetases while the second ATP binding pocket is specific to the GlyRS (Guo et al., 2009).

TABLE 1.

Enzymes synthesizing dinucleoside polyphosphates.

| Enzyme | Sourcea | Productsb | References |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases | Eukaryotes, prokaryotes | Ap3–5N, dAp4dA, Ap3Gp2 | Goerlich et al., 1982; Brevet et al., 1989; Guo et al., 2009 |

| Firefly luciferase | Photinus pyralis | Ap3–5N, Ap3–5dN, Gp4G | Guranowski et al., 1990; Sillero and Sillero, 2000 |

| DNA ligase | T4 phage, Homo sapiens (Lig3) | Ap3A, Ap4A, Ap4G, Ap4dA | Madrid et al., 1998; McLennan, 2000; Sillero and Sillero, 2000 |

| RNA ligase | T4 phage | Ap4A, Ap4G, Ap4dG, Ap4C, Ap4dC, Ap3A | Atencia et al., 1999; Sillero and Sillero, 2000 |

| Acyl-coenzyme A synthetase | P. fragi | Ap4–6A, Ap4N | Fontes et al., 1998 |

| 4-coumarate: coenzyme A ligase | A. thaliana | Ap4A, Ap5A, dAp4dA | Pietrowska-Borek et al., 2003 |

| UTP:glucose-1-phosphate uridylyl transferase | S. cerevisiae | Up4N, Up5A, Up5G | Guranowski et al., 2004 |

| Ap4A phosphorylase | S. cerevisiae | Ap4N, Ap4dA | Brevet et al., 1987; Guranowski et al., 1988 |

| GTP:GTP guanylyltransferase | A. franciscana | Gp4G, Gp4A, Gp3G, Gp3A | Liu and McLennan, 1994 |

| GTP:mRNA guanylyltransferase | S. cerevisiae | Gp4N, Gp3N | Wang and Shatkin, 1984 |

| Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase | B. brevis, E. coli | Ap4A, Ap5A, Ap6A | Dieckmann et al., 2001; Sikora et al., 2009 |

| Ubiquitin, SUMO and NEDD8-activating enzymes | H. sapiens | Ap4A, Ap3A | Götz et al., 2019 |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 | H. sapiens | Ap2A, Ap4A, Ap6A, Ap3G, Ap4U, Gp2G, Up4U | Jankowski et al., 2013 |

| Reverse transcriptase | HIV type 1 | Ap3ddA, Ap4ddA, Gp4ddAc | Smith et al., 2005 |

aOrthologous activities may also be present in related organisms. bExamples of products that have been detected; the list is not exhaustive and may vary with source of enzyme; only products likely to occur naturally are shown. cAlthough dideoxynucleotides are not natural, their formation indicates the potential for natural dinucleotide synthesis by reverse transcriptases.

Firefly luciferase and several other ligases including acyl-coenzyme A synthetase, T4 DNA ligase, DNA ligase III and T4 RNA ligase are also capable of synthesizing Ap4A and other Ap4Ns (McLennan, 2000; Sillero and Sillero, 2000; Fraga and Fontes, 2011). The mechanism behind firefly luciferase-mediated synthesis of Ap4N involves initial production of an enzyme-luciferyl-AMP intermediate (Guranowski et al., 1990). Similarly, acyl-CoA synthetase from Pseudomonas fragi can synthesize Ap4N possibly via an acyl-CoA-AMP intermediate (Fontes et al., 1998) and 4-coumarate:CoA ligase via a cinnamoyl-CoA intermediate (Pietrowska-Borek et al., 2003). An acyl-AMP intermediate is not essential as T4 RNA ligase can catalyze Ap4N synthesis through formation of a T4 RNA ligase-AMP complex, where ATP donates the AMP, followed by an NTP acting as an acceptor for the AMP directly from the ligase-AMP (Atencia et al., 1999). Different rates of synthesis can be seen for the different Ap4Ns, decreasing in the order Ap4dG > Ap4G > Ap4dC > Ap4C (Atencia et al., 1999). Similarly, T4 DNA ligase is able to synthesize Ap4A and Ap4G among other NpnN by formation of the ligase-AMP intermediate followed by reaction of NTP with the AMP (Madrid et al., 1998). In the context of genotoxic stress in mammalian cells, Ap4A synthesis may be mediated by the repair enzyme DNA ligase III (McLennan, 2000; Marriott et al., 2015).

There are also Ap4N synthetases that may operate specifically under stress conditions. For example, the heat-inducible E. coli LysU is a particularly efficient synthesizer of ApnN (Chen et al., 2013). The Bacillus brevis non-ribosomal peptide synthetase that responds to nutritional stress can also synthesize Ap4A (Dieckmann et al., 2001) as can the EntE subunit of the analogous complex from E. coli during iron starvation via an adenylated aryl-acid intermediate (Sikora et al., 2009). More recently, ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like E1 activating enzymes have also been shown to synthesize Ap4A as a side reaction in the ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like activation pathway (Götz et al., 2019). The ubiquitin activating enzyme UBA1 can initiate synthesis of Ap4A in a mechanism involving an adenylate-UBA1 intermediate in a process that is inhibited by increased concentrations of the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (Götz et al., 2019). In addition, ubiquitin-like enzymes NEDD8- and SUMO-activating enzymes are also able to synthesize Ap4A, but with lower activity (Götz et al., 2019). Thus, the cellular responses to stress promote the synthesis and accumulation of Ap4A and other ApnN species by degenerate mechanisms. While the wide range of enzymes able to synthesize ApnN in vitro may be seen as an argument against specific signaling roles for ApnN, the degenerate mechanisms ensure the timely and rapid accumulation of Ap4N in response to stress.

Regulation of Intracellular Ap4N Levels by Regulated Synthesis and Hydrolysis

To effectively function as a signaling molecule, Ap4N levels must be precisely controlled to prevent inappropriate activity in the absence of physiological, environmental, oxidative or genotoxic stress. Since Ap4N are synthesized continuously even in unstressed cells, Ap4N are efficiently degraded within cells preventing their accumulation to toxic levels. Any Ap4N-mediated signaling function would also require such regulation and several families of Ap4N hydrolyzing enzymes have been found in prokaryotes and eukaryotes (Table 2). Hydrolysis of Ap4N can occur either symmetrically or asymmetrically. In E. coli, the major hydrolytic activity, bis(5′-nucleosyl)-tetraphosphatase (ApaH), cleaves Ap4A symmetrically yielding ADP and this activity is also present in other β- and γ- proteobacteria (Guranowski et al., 1983). Significantly, Ap4A levels increase by up to 100-fold in ApaH– E. coli cells while a ∼10-fold decrease results from overexpression of the hydrolase, demonstrating the importance of ApaH for the regulation of Ap4A levels (Mechulam et al., 1985; Plateau et al., 1987; Farr et al., 1989). In Gram positive bacteria which lack the ApaH family enzyme, such as Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus, the YqeK protein family of Ap4A hydrolases has recently been found. The YqeK family has a similar Ap4A cleavage specificity to the ApaH hydrolases and deletion of the YqeK gene from B. subtilis leads to increases in Ap4N content (Minazzato et al., 2020).

TABLE 2.

Enzymes degrading dinucleoside polyphosphates.

| Enzyme | Source/gene | Reactiona | References |

| “Symmetrical” Ap4A hydrolase | β- and γ-proteo bacteria (ApaH) | Ap4A → ADP + ADP | Guranowski et al., 1983; Guranowski, 2000 |

| Gram-positive bacteria (YqeK) | Ap4A → ADP + ADP | Minazzato et al., 2020 | |

| Physarum polycephalum | Ap4A → ADP + ADP | Garrison et al., 1982 | |

| “Asymmetrical” Nudix Ap4A hydrolase | Animals (e.g., Nudt2), plants (e.g., AtNUDT25), proteobacteria (RppH/NudH/IalA/YgdP), mycobacteria (MutT1) | Ap4A → AMP + ATP | Guranowski, 2000; McLennan, 2006; Kraszewska, 2008; Arif et al., 2017 |

| Ap4A phosphorylase | S. cerevisiae (Apa1, Apa2), protists, cyanobacteria, mycobacteria (MtApa) | Ap4A + Pi ↔ ADP + ATP | Guranowski and Blanquet, 1985; McLennan et al., 1994, 1996; Hou et al., 2013; Honda et al., 2015 |

| HIT family hydrolases | S. cerevisiae (Aph), H. sapiens (FHIT) | Ap3A → AMP + ADP | Barnes et al., 1996 |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Aph1) | Ap4A → AMP + ATP | Ingram and Barnes, 2000 | |

| Non-specific phosphodi esterases | H. sapiens (e.g., NPP1, NPP3, NPP4) | Ap4A → AMP + ATP | Guranowski, 2000 |

aThe reaction with the best characterized or favored substrate is shown; other substrates may also be effective.

Asymmetrically cleaving Ap4N hydrolases, that yield ATP and AMP as products of Ap4A hydrolysis, fall into two families: the NUDIX family and the HIT family of dinucleotide hydrolases. The NUDIX superfamily is conserved from bacteria to man. NUDIX family ApnN hydrolases are found in Gram-negative bacteria including Bartonella bacilliformis (IaIA) (Cartwright et al., 1999; Conyers and Bessman, 1999), E. coli (variously known as NudH, YgdP, IalA and RppH) (Bessman et al., 2001) and the nudix family paralog MutT1 in Mycobacteria (Arif et al., 2017). Quantitatively, YgdP is less important in controlling the intracellular levels of Ap4A than ApaH in S. typhimurium (Ismail et al., 2003). However, both RppH and ApaH have the additional function of degrading both capped and uncapped 5′ ends of bacterial mRNAs. The major Ap4N hydrolase is encoded in humans by the NUDT2 gene (Thorne et al., 1995; McLennan, 2006) and deletion of NUDT2 results in a 175-fold increase in intracellular Ap4A (Marriott et al., 2015, 2016) confirming its significance as a major Ap4A hydrolase.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe lacks a nudix Ap4N hydrolase, and utilizes a HIT family enzyme Aph1 to cleave Ap4N asymmetrically (Huang et al., 1995). Aph1 contains the catalytic HIT motif (HφHφHφφ) and is a homolog of the human tumor suppressor FHIT protein, which prefers Ap3N substrates (Barnes et al., 1996). Saccharomyces cerevisiae also lacks an appropriate Nudix hydrolase but instead has two Ap4A phosphorylases, Apa1 and Apa2, that share 60% identity and which display phosphorolytic activity toward Ap4A and other NpnNs, yielding NTP and NDP (Guranowski and Blanquet, 1985; Plateau et al., 1990; Hou et al., 2013). These phosphorylases are found in many protists (McLennan et al., 1994), and can both hydrolyze and synthesize NpnNs including the non-adenylated dinucleotides. They are similar to the GalT proteins of the HIT family, which have a typical HXHXQφφ motif. Cyanobacteria and mycobacteria also have Ap4A phosphorylases (McLennan et al., 1996; Mori et al., 2010; Honda et al., 2015). The enzyme from M. tuberculosis is unusual in that it has a proper HIT motif (HφHφHφφ) more similar to the HIT family hydrolases than other Ap4A phosphorylases, but other amino acid changes in the active site may account for its phosphorylase activity (Mori et al., 2011). Members of the relatively non-specific nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (NPP) family can also hydrolyze NpnN but their relevance to the regulation of intracellular dinucleotide levels is not clear (Guranowski, 2000).

Ap4N-Mediated Regulation of mRNA Stability and Gene Expression in Bacteria

The long-held notion that all bacterial mRNAs retain the 5′-triphosphate of the initiating nucleotide has now been displaced by the discovery of various 5′ cap structures that alter mRNA stability and contribute to regulation of gene expression. In E. coli 10–15% of mRNAs are capped by derivatives of NAD and CoA (Chen et al., 2009; Kowtoniuk et al., 2009). Importantly, ApnNs (where N can be A, C, G, or U and n = 3 to 5) are also used in E. coli as 5′-mRNA caps in response to oxidative stress. Increases in disulfide stress following CdCl2 treatment promotes inactivation of the ApaH hydrolase leading to an increase in intracellular ApnN levels and accumulation of Npn caps on the majority of mRNA transcripts. The novel Npn caps extend mRNA half-life and potentially regulate gene expression (Luciano et al., 2019). The Npn caps can arise either by direct addition of AMP from an aminoacyladenylate to an mRNA 5′-ppp terminus catalyzed by LysU or by utilization of preformed ApnN as the initiating nucleotide by RNA polymerase. The strong influence on capping efficiency of changes to the untranscribed regions upstream of the promoter, particularly at position -1, suggests that the latter mechanism predominates (Luciano and Belasco, 2020). Ap4Ns can be incorporated at transcription initiation much more efficiently than ATP or ApnNs with other phosphate chain lengths, which demonstrates specificity in the interaction between Ap4N and the RNA polymerase/DNA template. Furthermore, the nature of the nucleotide at the +1 position differentially affects which Ap4N is incorporated with all four used when +1 is T but only Ap4G, Ap4C and Ap4U when +1 is C, G or A, respectively (Luciano and Belasco, 2020). Subsequently it was demonstrated that both bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase and E. coli RNA polymerase are capable of capping mRNA transcripts in vitro (Hudeček et al., 2020). In addition, ApnN-caps can be formed using other dinucleoside polyphosphates including Ap3A, Ap3G, and Ap5A. An additional layer of regulation is mediated by methylation of Ap4N molecules by an unknown methyltransferase. Methylation of Ap4N is associated with growth phase. Their abundance is low during exponential growth and increased during stationary phase when m6Ap3A, m7Gp4Gm, mAp5G, mAp4G, mAp5A, and 2mAp5G could be detected (Hudeček et al., 2020). The additional regulation of mRNA stability by methylation of the dinucleoside caps has important implications for mRNA stability and gene expression during stationary phase (Figure 2).

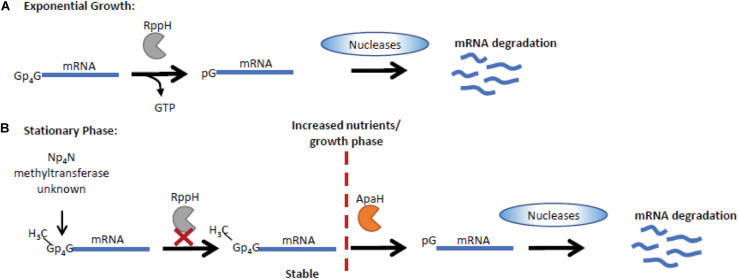

FIGURE 2.

Np4N regulates transcript stability in stationary phase in E. coli. (A) Np4N caps can be incorporated into mRNA during transcription initiation. During exponential growth, Np4N caps can be removed by RppH, generating an NTP and a 5′ p-terminus on the mRNA, which is then degraded by the RNase E endonuclease (Luciano et al., 2019). (B) In stationary phase, methylation of the Np4N caps increases their stability as RppH is unable to process methyl-Np4N-caps. The processing of methyl-Np4N-caps is mediated by ApaH that is downregulated during stationary phase, increasing methyl-Np4N-mRNA stability (Hudeček et al., 2020). Under conditions where growth can resume, ApaH is activated, promoting cleavage of methylated caps, resulting in mRNA with a 5′ p-terminus that is efficiently degraded by RNase E nucleases.

Both ApaH and RppH are capable of catalyzing Ap4N cap removal from mRNA in vitro. ApaH hydrolyzes the Np4 cap yielding an NDP and a 5′-pp terminus while, with lower efficiency, RppH generates a 5′-p terminus and NTP. However, in vivo in it seems likely that they act in concert with RppH, already established as acting upon 5′-ppp and 5′-pp termini (Luciano et al., 2018), generating a 5′-p terminus from the 5′-pp product of ApaH action, thus allowing further rapid 5′-degradation by the RNase E endonuclease (Farr et al., 1989; Deana et al., 2008; Monds et al., 2010; Luciano et al., 2019). The 5′ cap can also influence the rate of decapping, with RppH and ApaH showing distinct activities on methylated caps. ApaH can remove all Ap4N caps, while RppH cannot cleave methylated caps (Figure 2; Hudeček et al., 2020).

In unstressed E. coli cells, deletion of ApaH (but not RppH) also promotes increased Npn capping (Luciano et al., 2019). Thus, differences in the relative concentrations of Ap4Ns, the promoter sequence-dependent use of different caps and differences in the efficiencies of ApnN cap removal all combine to suggest that regulation of ApaH activity, whether by thiol inactivation or by other means, could provide a powerful means of controlling mRNA stability and differential gene expression. Npn capping may explain the phenotypic changes previously associated with increased intracellular Ap4N levels in bacteria including reduced motility, altered biofilm formation, reduced ability to invade mammalian cells, and uncoupling of DNA replication and cell division (Farr et al., 1989; Nishimura et al., 1997; Ismail et al., 2003; Deana et al., 2008; Monds et al., 2010). Each phenotype is associated with ApaH deletion or disruption although loss of cellular invasion is also commonly seen in bacteria lacking the nudix hydrolase RppH/NudH/YgdP/IalA. This suggests that precise regulation of intracellular Ap4N levels is required to prevent aberrant signaling. Such control is revealed in stressed cells where ApaH hydrolase acts as both sensor and effector through regulation of 5′ methyl-Np4 capped mRNA stability.

Ap4A-Mediated Regulation of Gene Expression in Eukaryotes

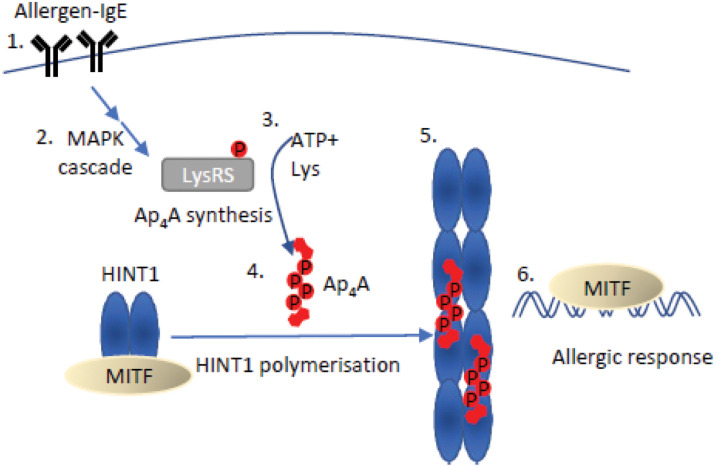

An early indication of a direct signaling role for Ap4A in eukaryotic cells was the regulation of MITF-mediated transcription in mast cells in response to allergen activation. HINT1 is an Ap4A-binding member of the HIT protein family. HINT1 interacts with microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) in the absence of any stimulus and represses its activity. When mast cells are activated by IgE-allergen binding to its cognate receptor, this enhances ERK1/2 activity promoting phosphorylation of LysRS on S207 (Yannay-Cohen et al., 2009). LysRS is an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase capable of efficient Ap4A synthesis (Zamecnik et al., 1966). Importantly, LysRS binds MITF to form a multiprotein complex with HINT1 which causes Ap4A to be produced in close proximity to HINT1, facilitating Ap4A-HINT1 binding (Lee et al., 2004). Activation of a mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascade promotes phosphorylation of LysRS (pS-207) resulting in its translocation to the nucleus. LysRS aminoacylation activity is inhibited by phosphorylation of S207 that concomitantly increases its Ap4A synthetic activity 3-fold. The increase in Ap4A levels promotes oligomerization of HINT and release of MITF (Figure 3; Razin et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2004; Yannay-Cohen et al., 2009).

FIGURE 3.

Mechanism of Ap4A mediated regulation of HINT1-MITF. An allergen bound to IgE (1) stimulates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade (2), resulting in the phosphorylation of LysRS on serine 207. Phosphorylation of LysRS increases Ap4A synthesis 3-fold (3) (Yannay-Cohen et al., 2009). The increase in Ap4A concentration causes dissociation of the MITF-HINT1 complex as Ap4A and MITF compete for the same binding site on HINT1. Ap4A binding to HINT1 promotes its polymerization (5). Ap4A bridges the HINT1 dimer–dimer interface promoting association with the adjacent dimer facilitating their polymerization (Yu et al., 2019). Following HINT1 polymer formation, MITF translocates to the nucleus to promote transcription of target genes and initiate an allergic response (6) (Yu et al., 2019).

The dissociation of the HINT1-MITF complex can also be induced in melanoma cells through post-translational modification of HINT1 residues surrounding the MITF-HINT1 interface, which may allow prolongation of MITF-controlled processes (Motzik et al., 2017). Importantly, these residues are proximal to the Ap4A binding site in HINT1, suggesting a competitive mechanism between Ap4A and MITF for HINT1 binding (Figure 3; Yu et al., 2019). The specificity of this transcriptional response for a dinucleoside tetraphosphate arises from the specific requirements for oligophosphate chain length for the oligomerization of HINT1. Despite Ap3A showing reduced inhibition of MITF activity (though less than Ap4A), neither Ap3A nor Ap5A could initiate HINT1 polymerization (Yu et al., 2019). The HINT1-Ap4A crystal structure revealed the structural basis for the specific chain length for optimal Ap4A-HINT interactions, as Ap3A chain length was insufficient to interact at nucleotide binding pockets and Ap5A binding required a contortion of the phosphodiester linkages (Yu et al., 2019). Recently some doubt has been expressed regarding the ability of HINT1 to bind Ap4A, but this could reflect differences in analytical techniques and a lack of post-translational modifications in the HINT1 used (Strom et al., 2020).

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor is involved in signaling in a wide variety of processes including DNA repair and cell survival, as well as cell proliferation and invasion (Goding and Arnheiter, 2019). After Ap4A-mediated dissociation from HINT1, MITF is free to bind E box enhancer elements in the promoter region of specific genes, resulting in stimulation of their transcription (Lee et al., 2004). To prevent deregulation of MITF-target genes, levels of Ap4A are subsequently down-regulated by hydrolysis, demonstrated by the changes in expression of rat MITF- (and USF2-) target genes when Nudt2, the major Ap4A hydrolase, is knocked down (Carmi-Levy et al., 2008). Similarly, MITF localization to the nucleus and increased transcription of MITF-target gene TRACP5 has also been demonstrated in murine dendritic cells that have a floxed Nudt2 gene and therefore a 30-fold increase in Ap4A levels (La Shu et al., 2019). Further evidence for the importance of precise control of Ap4A levels was demonstrated in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) with floxed NUDT2. This leads to greater motility and increased proliferation of CD8+ T cells that require cross-antigen presentation, however, this only correlates with increased MITF target gene expression and is not necessarily directly caused by it (La Shu et al., 2019). The structural, biochemical and cellular analysis of the role of Ap4A in the regulation of HINT1-MITF demonstrate that Ap4A does indeed perform a bona fide signaling role that can precisely regulate transcriptional programs in specific cellular lineages.

Ap4A Mediated Regulation of the cGAS-STING Pathway

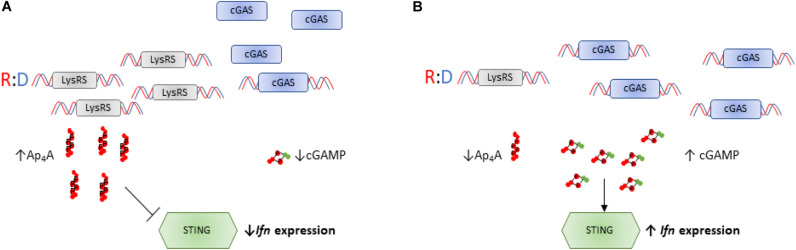

A second transcriptional program influenced by LysRS-mediated Ap4A accumulation is the STING-dependent inflammatory response. The cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon (IFN) genes (STING) pathway is a component of the innate immune response that contributes to recognition of viral nucleic acid within cells (Almine et al., 2017). In response to viral nucleic acid, cGAS generates cGAMP that activates STING and downstream transcription factors such as STAT6 and IRF3 via TANK-binding kinase 1 leading to expression of type 1 interferons. Evidence has been presented that LysRS plays a role in suppressing cGAS activation via two complementary mechanisms, one of which involves the synthesis of Ap4A (Guerra et al., 2020). First, LysRS competes with cGAS for binding to RNA-DNA hybrids thus reducing the synthesis of cGAMP, and secondly LysRS synthesizes Ap4A which binds to the cGAMP binding pocket of STING preventing its activation (Figure 4; Guerra et al., 2020).

FIGURE 4.

Ap4A regulates activity of the cGAS-STING pathway. (A) LysRS suppresses activation of cGAS through two distinct mechanisms: (i) LysRS competes with cGAS for binding DNA hybrids, reducing cGAS:hybrid interactions and therefore reducing synthesis of cGAMP (ii) LysRS synthesizes Ap4A which binds to STING in the cGAMP binding pocket, delaying interactions between cGAMP and STING (Guerra et al., 2020). This therefore inhibits STING activation and reduces interferon expression. (B) When LysRS levels are low, it cannot successfully compete with cGAS for R:D hybrid binding. This results in efficient cGAS/R:D hybrid interactions and increased cGAMP production (Guerra et al., 2020). High intracellular cGAMP and low intracellular Ap4A concentrations results in efficient activation of STING and increased interferon expression.

The modeling of cGAS-Ap4A interactions revealed contortions of the phosphate linker suggesting that chain length may affect function, although no analysis was performed using other NpnNs. There was also an effect of extracellular Ap4A and a non-hydrolyzable analog in reducing IFNβ mRNA production. Interestingly, in the context of innate host defense to viral nucleic acids, ApnA, and in particular Ap5A, are sub-micromolar inhibitors of the pancreatic ribonuclease superfamily including eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, an important antiviral protein (Kumar et al., 2003; Baker et al., 2006). Also, the NUDT2 Ap4A hydrolase has been reported to interact with the SARS coronavirus 7a protein (Vasilenko et al., 2010). The effect of this interaction is unknown but if it led to NUDT2 inhibition and a rise in Ap4A, this could provide a means for the virus to prevent STING activation and add to the repertoire of mechanisms used by coronaviruses to evade the innate host immune response (Maringer and Fernandez-Sesma, 2014).

The regulation of cGAS-STING by Ap4A and the observed reduction in IFN signaling by high Ap4A levels is entirely consistent with the effect of NUDT2 disruption on the transcriptome of KBM-7 CML cells (Marriott et al., 2016). Inactivation of the NUDT2 Ap4A hydrolase led to a 175-fold increase in intracellular Ap4A and major changes in the transcriptome involving over 6,000 differentially expressed genes. Among the down-regulated gene sets were those associated with interferon responses, pattern recognition receptors and inflammation while functions associated with MHC class II antigens featured among the up-regulated genes. For example, in agreement with the study above, IFNβ was down-regulated 15-fold. Tryptophan catabolism was also strongly down-regulated as were genes involved in tumor promotion, particularly in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition, proliferation, invasion and metastasis. No single cause was identified for these changes but possibilities discussed included LysRS-mediated HINT1 activation, inhibition of protein kinases and other enzymes/proteins, autocrine activation of purinoceptors and chromatin remodeling. However, given the recently discovered role of dinucleotide caps in regulating mRNA stability in prokaryotes, a similar alternative function for increased Ap4N in regulating specific mRNA turnover in mammalian cells cannot be ruled out. Four different classes of enzyme possess decapping ability in eukaryotes (Kramer and McLennan, 2019). The “classical” decapping enzyme is DCP2 (NUDT20), a nudix family hydrolase. However, both NUDT3 and NUDT16 appear to decap specific subsets of mRNAs while several other nudix hydrolases, including NUDT2, can hydrolyze a variety of canonical and non-canonical caps in vitro and also bind RNA (Grudzien-Nogalska and Kiledjian, 2017; Ray and Frick, 2020; Sharma et al., 2020). DXO enzymes can remove caps from incompletely capped mRNAs as part of the cap quality control pathway and also NAD, FAD and dephospho-CoA caps (Doamekpor et al., 2020), while HIT family enzymes degrade capped RNA fragments that are remnants of the 3′ to 5′ decay pathway. Finally, the major enzyme involved in decapping of mRNA transcripts in Trypanosoma brucei, ALPH1, is an ApaH-like phosphatase that cleaves the unusual caps found in this organism (Perry et al., 1987; Kramer, 2017). Thus, there are several candidates that could perform Np4-cap removal in eukaryotes, if Ap4N are capable of initiating synthesis of mRNA. This modification has not yet been identified in eukaryotes, but this remains an intriguing possibility for the regulation of mRNA stability in stressed cells. Such a mechanism could go a long way to explain the dramatic changes observed in the transcriptome of NUDT2 knockout cells (Marriott et al., 2016).

There has also been a suggestion that Ap4A could regulate the 3′ end processing of pre-mRNA. Cleavage factor Im (CF Im) defines the site of 3′ poly(A) addition by inducing both poly(A) addition and cleavage (Brown and Gilmartin, 2003). The 25 kDa subunit of CF Im (CF Im25, F5, NUDT21) is a catalytically inactive nudix protein that binds Ap4A as a homodimer in a manner that excludes RNA suggesting that Ap4A binding may somehow control CF Im activity (Yang et al., 2010). CF Im is regulated by ATP binding that both inhibits and activates 3′ cleavage of pre-mRNAs in a concentration dependent manner. Ap4A has a higher affinity for CF Im relative to ATP (Coseno et al., 2008). However, unlike ATP, Ap4A does not affect ATP-stimulated cleavage (Khleborodova et al., 2016). Thus, the evidence that Ap4A contributes to regulation of the 3′ end of mRNA remains questionable.

Ap4A as a DNA Damage-Associated Regulator of Eukaryotic DNA Replication

The synthesis of Ap4A in response to genotoxic stress suggests possible roles in the DNA damage response, DNA replication and cell cycle progression. However, there are conflicting reports regarding the role of Ap4A in the regulation of DNA replication. Initially, Ap4A was found to initiate DNA replication when added to permeabilized G1-arrested BHK cells and was later reported to increase up to 1000-fold prior to S-phase entry (Grummt, 1978, 1979; Weinmann-Dorsch et al., 1984; Zourgui et al., 1984). It also stimulated DNA replication in microinjected Xenopus laevis oocytes (Zourgui et al., 1984). However, other reports failed to confirm these findings (Garrison et al., 1986; Moris et al., 1987; Orfanoudakis et al., 1987; Perret et al., 1990). In support of a role in initiation, Ap4A was found to associate with a DNA polymerase α complex that synthesizes the RNA primers required for DNA replication (Grummt et al., 1979; Rapaport et al., 1981) and an Ap4A-binding protein was identified in this complex in calf thymus and HeLa cells (Grummt et al., 1979; Rapaport et al., 1981). This protein was later resolved into 45 kDa (A1) and 22 kDa (A2) polypeptides, with Ap4A binding to the larger polypeptide (Baxi et al., 1994) but it still remains unidentified. In the context of DNA repair, another nuclear Ap4A-binding protein is uracil DNA-glycosylase/glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (UDG/GAPDH), which interacts with several DNA repair factors (Baxi and Vishwanatha, 1995; Azam et al., 2008; Kosova et al., 2017). Ap4A was also able to act as a preformed primer for DNA polymerase α in vitro (Zamecnik et al., 1982). This draws an interesting parallel with the use of ApnN as primers for RNA polymerase in the production of 5′ Np4 mRNA caps in E. coli as discussed earlier. The use of non-canonical initiating nucleotides is shared by the E. coli DnaG primase, which can initiate primer synthesis with NADH and FAD (Julius et al., 2020). The use of novel nucleotides for the initiation of RNA primer synthesis has important implications for the potential role of Ap4A and other Ap4N in the regulation of the initiation phase of DNA replication. However, the reconstitution of origin firing in vitro using 16 recombinant proteins (Yeeles et al., 2015; Aria and Yeeles, 2019) provides no opportunity for the addition or production of Ap4A. Hence, at least for the minimal DNA replication machinery from S. cerevisiae, Ap4A is not essential for the initiation phase of DNA replication; however, this does not exclude a function as an initiator in some specific contexts.

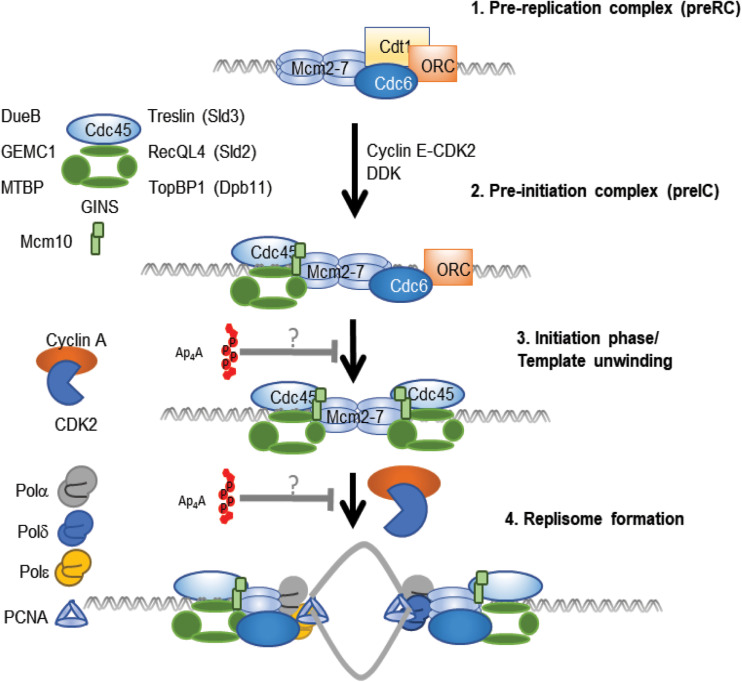

In contrast to results supporting the promotion of DNA replication by Ap4A, recent evidence suggests that Ap4A inhibits the initiation phase of DNA replication. An early indication of an inhibitory effect of Ap4A during initiation was the abrupt fall in Ap4A before the onset of each S-phase in sea urchin embryos (Morioka and Shimada, 1985). More recently, Ap4A was found to directly inhibit the initiation phase, but not the elongation phase of DNA replication in a cell-free replication system comprising mouse cell nuclei and cytoplasmic factors. Initiation was inhibited maximally by about 70–80% in nuclei treated with >20 μM Ap4A, a level consistent with that found after treatment with sub-lethal doses of cross-linking agents (Marriott et al., 2015). Ap3A, Ap5A, Gp4G, and ADP-ribosylated Ap4A were without significant effect, demonstrating a high degree of specificity in this response. As Ap4A concentration increases under a number of different stresses, this suggests that Ap4A may be involved in inhibiting DNA replication initiation when the cell is under stress in order to preserve genome integrity during recovery (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Ap4A-mediated inhibition of DNA replication model. The first step of DNA replication involves the formation of the Pre-replication complex (1), where Cdc6 and the origin recognition complex (ORC) promote formation of the Mcm2-7 double hexamer through the recruitment of Cdt1 molecules (Takara and Bell, 2011). This is followed by activation of the complex through further recruitment of several proteins to form the Pre-initiation complex (pre-IC) (2) (Pacek et al., 2006). With Ap4A at low levels, Cyclin A and Cdk2 would initiate DNA replication and template unwinding (3), resulting in the recruitment of several polymerases and PCNA to form the replisome (4) (Yao and O’Donnell, 2010). Ap4A inhibits the initiation phase of DNA replication (Marriott et al., 2015). There is potential for Ap4A to inhibit either the 3rd or 4th step in this process. However, the precise mechanism and the protein(s) that Ap4A associates with to inhibit DNA replication remains to be determined. This is highlighted with “?” in figure to highlight that Ap4A may act to inhibit the pre-IC to template unwinding step or prevent activation of the replisome.

Of the dinucleotides tested only Ap4A has so far been found to inhibit DNA replication. The effect of Ap4A in the HINT1-MITF (Yu et al., 2019) and cGAS-STING (Guerra et al., 2020) pathways involves competitive inhibition, where Ap4A competes for ATP binding pockets. Such a mechanism offers several opportunities for the regulation of DNA replication where ATP is required for origin specification, kinase activity, clamp loading, helicase activity, primer synthesis and elongation of the DNA template. Thus, Ap4A could act by inhibition of an ATP-dependent step during the initiation phase of DNA replication. The model presented above highlights that there are only two phases that could be affected by Ap4A in in vitro cell free DNA replication assays that utilize replication licensed nuclei. The CDK dependent initiation of DNA replication involves recruitment and activation of the replicative helicase and replisome formation indicating several factors that could be affected during this process (Figure 5). Identification and analysis of the proteins with which Ap4A associates could reveal relevant targets for Ap4A-mediated competitive inhibition.

The observed role for Ap4A in the initiation phase of DNA replication may also be supported by the finding that direct exposure of T47D and MCF7 breast cancer cells to 100 μM Ap4A slows their proliferation rate while increased NUDT2 expression (with a resulting reduction in Ap4A) increases their proliferation (Oka et al., 2011). However, other studies suggest that cells can tolerate greatly increased intracellular Ap4A without a noticeable effect on proliferation (Murphy and McLennan, 2004; Marriott et al., 2016). Thus, the cell-free system that identified the inhibition of replication initiation by Ap4A may reflect a response to acute changes to Ap4A levels that is overcome under chronic stress conditions such as in the NUDT2 knockout KBM7 cell lines.

Interestingly, various dNpndN can act as elongation substrates for some DNA polymerases, including E. coli Pol I, human pol α and β, and HIV reverse transcriptase with the elimination of an NTP rather than the usual PPi (Victorova et al., 1999). The reverse reaction analogous to pyrophosphorolysis can remove 3′ chain terminating dideoxynucleotides such as those incorporated from anti-HIV drugs to generate dinucleoside polyphosphates (Table 1; Smith et al., 2005; Dharmasena et al., 2007). How these findings relate to the inhibition of DNA replication initiation by Ap4A is currently unclear but they do illustrate that ApnN and other NpnN are not excluded from the replication apparatus and may be generated as signals and/or primers by DNA polymerases at stalled replication forks (Figure 5) Therefore, a more detailed understanding of the potential roles of other Ap4N molecules in the DNA replication process in vivo is required.

Additional Ap4A Binding Partners and Downstream Signaling

The association of Ap4A with HINT1 and STING and the subsequent downstream events would appear to satisfy sufficient criteria to classify Ap4A as a bona fide signaling molecule in eukaryotes. Is there any evidence for other binding proteins and pathways? Despite much interest and research, Ap4A binding partners with clear roles in signaling pathways remained elusive for many years. Initially, several stress proteins in E. coli were found to interact with Ap4A, including DnaK, GroEL, ClpB, C45 and C40 (Johnstone and Farr, 1991; Fuge and Farr, 1993). Binding of Ap4A to the GroEL chaperone was later found to involve sites distinct from the known ATP/ADP binding sites and a novel role in promoting substrate release from the substrate-GroEL complex was suggested (Tanner et al., 2006). The hsp70 family are homologs of the DnaK protein and several Ap4A-binding hsp70 proteins have also been found in murine brain lysates by magnetic biopanning using biotin-conjugated Ap4A, which demonstrates that Ap4A-stress protein binding occurs across different kingdoms (Guo et al., 2011). However, it is unclear whether Ap4A is acting as anything other than an ATP analog in binding to these proteins (Despotović et al., 2017). Several other Ap4A-binding proteins have been consistently found using these methods (Guo et al., 2011; Azhar et al., 2014) but with no obvious clue as to function of the interaction. One of these is inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH), which contains a cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) domain. These domains are often found in pairs forming a cleft to which nucleotides can bind, known as the Bateman domain (Baykov et al., 2011). Several enzymes contain CBS domains including CBS, IMPDH and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (Anashkin et al., 2017). Of these, Ap4A was found to bind bacterial IMPDH, an important control enzyme in the biosynthesis of guanine nucleotides with three allosteric nucleotide binding sites, and a potential role for Ap4A in regulating cell proliferation via IMPDH was suggested (Guo et al., 2011; Anashkin et al., 2017). However, the binding affinity of Ap4A is not much greater than that of ATP, probably because it can only bind to a single site, and its physiological role has been questioned (Despotović et al., 2017; Fernández-Justel et al., 2019). On the other hand, because of their increased polyphosphate chain length, Ap5A and Ap6A can span canonical sites 1 and 2 in Ashbya gossypii IMPDH (AgIMPDH) and submicromolar levels of these nucleotides can reverse inhibition of AgIMPDH induced by millimolar GDP. Due to a slight structural difference, a similar effect was only found for Ap5A with human IMPDH (Fernández-Justel et al., 2019). In contrast, Ap5G potentiates GTP/GDP-mediated allosteric inhibition of both IMPDH enzymes by binding to sites 1 and 2 with the G in site 2, which enhances GDP/GTP binding to site 3. These effects suggest a role for Ap5N in IMPDH regulation.

The suggested lack of relevance of Ap4A as a protein ligand highlights a particular problem with this nucleotide in that it may often simply bind to proteins via a single adenosine moiety as an ATP analog. Binding specificity or at least a favorable comparison of binding constants is necessary before biological relevance can be proposed. For example, some family II pyrophosphatases, such as a pyrophosphatase from Clostridium perfringens, contain two CBS domains (CBS-PPases) unusually linked by a DRTGG domain (Tuominen et al., 2010). These pyrophosphatases are inhibited by AMP binding to each CBS monomer and can be activated through Ap4A binding to Met114 and Tyr278 of CBS domains 1 and 2, respectively, residues that are present in pairs at the subunit interface (Tuominen et al., 2010). ApnA, where n = 4–6, can bind the CBS domains of pyrophosphatases from C. perfringens, Desulfitobacterium hafniense and Clostridium novyi non-cooperatively with nanomolar affinities, increasing their activity between 5- and 30-fold dependent on species (Anashkin et al., 2015). The DRTGG domain is likely to be important in this interaction, as CBS-PPase activities in Eggerthella lenta and Moorella thermoacetica, which do not possess a DRTGG domain, were not affected by the diadenosine polyphosphates (Anashkin et al., 2015). This high affinity binding suggests that ApnAs can control CBS-PPase activity and hence regulate pyrophosphate levels in bacteria.

Other intracellular signaling pathways can be affected by changes in ApnA levels. When pancreatic islets were incubated with glucose to induce insulin release, the intracellular concentrations of Ap4A and Ap3A were found to rise 70- and 30-fold to 14 and 11 μM, respectively. Such concentrations are sufficient to close KATP channels in β-cell membrane patches resulting in membrane depolarization and insulin release, suggesting that these dinucleotides act as second messengers to mediate glucose-induced blockade of β-cell KATP channels (Ripoll et al., 1996; Martín et al., 1998). This may occur through ApnA-mediated inhibition of adenylate kinase, a determinant of KATP channel activity (Stanojevic et al., 2008). A similar role for Ap5A in regulating KATP channel activity in cardiac myocytes has also been proposed (Jovanovic et al., 1998). Micromolar levels of ApnA are also able to activate ryanodine receptors in brain and heart endoplasmic reticulum and have been proposed as physiological regulators of these calcium release channels (Shepel et al., 2003; Song et al., 2009).

ApnN Signaling Through Internalization of Extracellular Pools

In addition to the intracellular signaling mechanisms discussed here ApnN are involved in a number of extracellular signaling networks (Jankowski et al., 2009). These nucleotides are mostly released from stores such as adrenal chromaffin granules and platelet dense granules into the extracellular space where generally they operate via cell-surface purinergic receptors. Endothelial cells may also release ApnN, and in particular Ap4U, synthesized by an unusual activity of the cytoplasmic domain of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (Jankowski et al., 2013). However, some extracellular ApnN may become internalized and operate intracellularly. The first indication of this was the internalization of radiolabeled Ap4A by bovine aortic endothelial cells via a two-step mechanism (Hilderman and Fairbank, 1999). Some studies that show an intracellular response to added Ap4A, e.g., STING inhibition (Guerra et al., 2020), must presumably rely on such a mechanism but it remains unidentified. Similarly, internalization may be behind changes in gene expression induced by external NpnN in plants. When Ap4A was added to Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings there was an increase in the expression of several genes and activity of proteins involved in early steps of the phenylpropanoid pathway (Pietrowska-Borek et al., 2011). The phenylpropanoid pathway is triggered in response to stress and results in the production of stilbenes such as resveratrol, as well as flavonols and lignins (Dixon and Paiva, 1995). Importantly, 4-Coumarate:CoA ligase, known to synthesize Ap4A, is one of the enzymes in the phenylpropanoid pathway whose activity was increased by the addition of Ap4A (Pietrowska-Borek et al., 2003, 2011). More recently it was also shown that a variety of other NpnNs can modulate the phenylpropanoid pathway in Vitis vinifera cv. Monastrell suspension cultured cells, meaning that induction of the response is not specific to Ap4A (Pietrowska-Borek et al., 2020b). Interestingly, certain variations in nucleotide have opposing effects. Ap3A induced accumulation of the stilbene trans-resveratrol, a response that was also induced by Up3U, Ap3U, Up4U as well as others; however, Cp3C, Cp4C, Ap3C, and Ap4C all inhibited stilbene synthesis, causing stilbene levels to be 300–400-fold lower than controls (Pietrowska-Borek et al., 2020b). Despite this evidence suggesting a role for NpnNs in regulation of the phenylpropanoid pathway, no receptors or signaling pathways have been identified. It has been suggested that pathogens may synthesize the NpnNs, which could be transported into the cell by some unknown mechanism involving plasma membrane transporters (Pietrowska-Borek et al., 2020a).

Roles for Dinucleoside Polyphosphates Other Than Ap4A

While most attention over the years has focused on Ap4A, it is clearly not the only NpnN with biological activity. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases can adenylate a wide variety of nucleotide acceptors both in vitro and in vivo with varying efficiencies to yield products such as Ap3A, Ap3G, Ap4C, Ap5U, and Ap3Gp2 (from ppGpp). Non-nucleotide acceptors such as tri- and tetrapolyphosphate, thiamine pyrophosphate and isoprenyl polyphosphates can also be adenylated, the former pair yielding p4A and p5A which can be further adenylated to give Ap5A and Ap6A (Plateau and Blanquet, 1982; Brevet et al., 1989; McLennan, 1992; Sillero et al., 2009). Ap5A is a potent “multisubstrate” inhibitor of adenylate kinases (Lienhard and Secemski, 1973) and is frequently used in vitro to inhibit this enzyme although whether it can do so in vivo has not been properly investigated. Non-adenylated NpnN such as Cp4C, Gp4G, Cp4U etc., have also been found in E. coli and S. cerevisiae and increase in concentration after oxidative and thermal stress (Coste et al., 1987). These could be generated by a number of enzymes including Ap4A phosphorylases, UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase and capping guanylyltransferases and could also conceivably arise non-enzymically (Wang and Shatkin, 1984; McLennan, 2000; Guranowski et al., 2004; Table 1). Many of the more unusual derivatives probably are damage metabolites. However, functions have been assigned to some of the homodinucleotides. The potential for Ap5A to regulate IMPDH activity and the ability of Ap3A, Up3U, Up4U, and Cp4C to differentially regulate stilbene synthesis in V. vinifera have already been described (Pietrowska-Borek et al., 2020b). In mammals, Ap3A is a ligand of the FHIT tumor suppressor protein. It has hydrolase activity and this controls the intracellular level of Ap3A (Barnes et al., 1996; Murphy et al., 2000). Ap3A binding but not hydrolysis is required for its tumor suppressive function (Pace et al., 1998). FHIT has been implicated in several pro-apoptotic pathways but the precise role of Ap3A binding remain elusive (Okumura et al., 2009). Gp4G and Gp3G have unique roles as a source of purines and energy in encysted embryos of the brine shrimp Artemia franciscana and closely related crustacea and are synthesized by a unique Gp4G synthetase (Liu and McLennan, 1994).

What about the various heterodinucleotides and molecules containing a non-nucleotide moiety? Do they have specific roles beyond those recently revealed in mRNA capping? Some of the common Ap4A assays, such as those based on bioluminescence, will also record and include other adenylated dinucleotides in the “Ap4A pool” and they are often ignored as being “minor” or of lesser importance as they are usually present at lower concentrations. Where they have been measured separately they tend to behave in a manner similar to ApnA, e.g., the lack of cell cycle fluctuation and increase in response to dinitrophenol treatment displayed by both Ap4A and Ap4G in Physarum polycephalum (Garrison et al., 1986). Nevertheless, as regulation or deletion of hydrolases such as NUDT2, FHIT, ApaH and RppH will alter their levels alongside Ap4A, Ap3A etc., possible differential or even unique activities should not be discounted. The spanning of two nucleotide-binding sites in IMPDH by Ap5G (Fernández-Justel et al., 2019) is a good example of the potential regulation of enzyme activities by ApnN. Ap4dT and Ap5dT can inhibit thymidine kinase, the higher potency of the latter showing the importance of polyphosphate chain length (Bone et al., 1986). Additionally, the uridine kinase of Ehrlich ascites tumor cells is inhibited by Ap4U and various deoxynucleotide kinases of Lactobacillus acidophilus by micromolar concentrations of Ap4dC, Ap4dT and Ap4dG as appropriate (Cheng et al., 1986; Ikeda et al., 1986). An adenylated derivative of isopentenyl pyrophosphate, unfortunately called ApppI (Ap3I) where I is not inosine, accumulates in cells where the mevalonate pathway has been inhibited by nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates and inhibits the mitochondrial adenine nucleotide translocase resulting in apoptosis, providing a mechanism for the action of these drugs (Mönkkönen et al., 2006). Thiaminylated ATP (AThTP, Ap3Th) accumulates in E. coli specifically in response to carbon starvation and may signal starvation stress. It has also been detected in plant and animal tissues and can inhibit the enzyme PARP-1 (Bettendorff et al., 2007; Tanaka et al., 2011). The potency of enzyme inhibition caused by many of these dinucleotides does show the problems they could cause as unregulated damage metabolites but the harnessing of this ability for more beneficial purposes has yet to be ruled out. Bacterial cGAS-like enzymes have recently been found to synthesize a wide range of purine- and pyrimidine-containing cyclic di- and trinucleotides with apparent signaling ability (Whiteley et al., 2019) and perhaps the same could yet be true for many NpnN species.

Discussion and Future Perspectives

Compared to other signaling molecules such as cyclic dinucleotides, “magic spot” guanine nucleotides and inositol polyphosphates, dinucleoside polyphosphates have consistently confounded attempts to define their biological roles, leading to the suggestion that they are functionless damage metabolites. However, recent evidence from studies in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes has finally established intracellular roles for the adenosine-containing members of this family, generally as part of the cellular response to molecular stress. The number of enzymes potentially able to regulate these Ap4N through synthesis and degradation has also been expanded.

Whether one can apply the labels “signal” or “messenger” to the stress-promoted use of Ap4N as RNA polymerase initiators in prokaryotes depends on how far one should be bound by the commonly used qualifying definitions of these terms, but they can at least be viewed as active participants in the regulation of mRNA stability under conditions of oxidative stress. Moreover, as these conditions lead directly to a rise in Ap4N levels via ApaH inactivation, the epithet “signal” seems reasonable in this context. Active participation of Ap4N as primers for DNA replication leading either to activation, inhibition or rescue of replication depending on other factors or experimental conditions may be an analogous mechanism and requires further investigation. In addition to any participatory roles in mammalian cells, however, the activation of MITF-mediated transcription and modulation of STING-mediated interferon responses by binding of Ap4A to a specific target protein clearly satisfy sufficient of the standard signaling criteria to allow the inclusion of diadenosine polyphosphates within the superfamily of highly phosphorylated small signaling molecules.

Thus, the functions of dinucleoside polyphosphates may be classified into two distinct modes of action: first, as primers for nucleic acid synthesis, and secondly as competitive ligands of ATP-binding sites on target proteins. The distinct modes of action for different members of the ApnN family may introduce considerable flexibility into the responses. For example, the use of various ApnN species for initiation at different bacterial promoters can affect the stability of specific mRNAs depending on the relative concentrations of available ApnN and their rates of removal from the 5′ ends. The regulation of MITF activity may be exclusive to Ap4A as the mechanism requires binding to two adjacent ATP-specific binding pockets in HINT1 dimers. On the other hand, the competition between cGAMP and Ap4A for binding to STING involves a nucleotide binding pocket that can accommodate both guanosine and adenosine, raising the question as to whether other Ap4N and in particular Ap4G could also mediate this function. Thus, there is now a clear need to discriminate between the activities of Ap4A and other ApnN and even NpnN in vivo. Several of the recently described pathways, such as mRNA capping and the regulation of gene expression by the internalization of plant dinucleotides, have highlighted the possibility that other ApnN and NpnN may have roles in the signaling of stress across different species. By analogy, there is potential for ApnN to perform a stress-related non-canonical mRNA cap function in eukaryotes, but this has not yet been demonstrated.

The importance of Ap3A to the tumor suppressor function of the FHIT protein is already well established, although its precise role is still unclear. The possible relevance in vivo of other Ap3N and Np3N, all substrates for the FHIT hydrolase activity, is also unknown. Despite their observed functions in prokaryotic transcriptional control, individual ApnN have yet to be reliably detected and quantified in mammalian cells. This will require improved detection technologies. The use of coupled enzyme assays (typically luciferase-based) to determine “Ap4A” levels is suboptimal as they do not discriminate between Ap4A and other Ap4N as ATP can be produced from either by the coupled Ap4A hydrolase. This has potentially limited our understanding and appreciation of individual Ap4N in mammalian cells. Advances in detection via liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectroscopy have aided the quantitation of different ApnN and have led to the identification of Ap4U in extracellular environments (Schulz et al., 2014; Götz et al., 2019; Ji et al., 2019; Fung et al., 2020). Establishing new LC-MS/MS methods for the analysis of individual intracellular ApnN and other NpnN will clarify the biological relevance of these dinucleotides in stress responses in mammalian systems.

Furthermore, it has not yet been determined which enzyme(s) in addition to LysRS may be responsible for the synthesis of individual ApnN under different circumstances in vivo. The production of ApnN in vitro usually involves either an acyl-adenylate or enzyme-adenylate intermediate, with the adenylate being subsequently transferred to an acceptor nucleotide. All of the enzymes previously described can do this in vitro to some extent and are therefore candidates. Moreover, the cytoplasmic domain of VEGFR2 appears able to generate various dinucleotides by direct condensation of two mononucleotides without an intermediate and could be a paradigm for the intracellular production of ApnN and NpnN by other receptor proteins. It is therefore important that any future study of dinucleotide-mediated signaling includes a determination of both the synthetic and degradative pathways. A more critical evaluation of ApnN-binding proteins as potentially relevant targets is also required. Because ApnN bind to many ATP-binding proteins, a functional and specific consequence of ApnN binding needs to be demonstrated in addition to binding itself.

The role of Ap4A and other ApnN in DNA replication and the DNA damage response also requires clarification. The synthesis of Ap4A in response to DNA damage with a resulting inhibition of the initiation of DNA replication may contribute to mechanisms that pause the cell cycle whilst the damage is repaired. Inhibition rather than promotion of replication by Ap4A as previously suggested appears to be more plausible. However, there are still many questions. Is the observed inhibition of initiation by Ap4A specific for this nucleotide or can other Ap4Ns mediate this response and is it due to a priming or competitive inhibition mode of action? Evaluation of inhibition with Ap3A, Ap4A, Ap5A, polyADP-ribosylated-Ap4A and Gp4G demonstrated that only Ap4A could inhibit initiation, but other ApnN have yet to be tested. Given that Ap4A can act as a primer for DNA polymerase-α in vitro, is it integrated into RNA primers during the initiation phase of DNA replication? If so, would this affect DNA replication kinetics or potentially inhibit this step through primer instability analogous to mRNA decapping? This could perhaps explain the apparent lack of inhibition of the elongation phase of replication by Ap4A as leading strand synthesis is possible with fork restart in contrast to initiation and lagging strand synthesis, which require an RNA primer. Finally, recent evidence supporting separate roles for cGAS and STING in the response to endogenous DNA damage raises the possibility that Ap4A could be involved in integrating different aspects of the DNA damage response through both the inhibition of DNA replication and endogenous DNA damage sensing. For example, by binding STING, Ap4A may promote the assembly of nuclear cGAS-independent STING signaling complexes that lead to NF-κB activation (Unterholzner and Dunphy, 2019). Ap4A may therefore be an important player in the mechanisms through which DNA damage activates immune responses to target and eliminate cancer cells.

In conclusion, we suggest that there is now sufficient evidence from both prokaryotes and eukaryotes to demonstrate that dinucleoside polyphosphates have multifaceted signaling activities. We anticipate that there will be significant advances in this area as the Ap4N and the NpnN family are further characterized, adding to recent observations that have demonstrated their capacity to regulate cellular responses to stress.

Author Contributions

NC and FF produced the figures. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by NWCR through the award of a Ph.D. scholarship through the NWCRC at Liverpool University (NC, AM, NJ, MU, and FF).

References

- Almine J. F., O’Hare C. A. J., Dunphy G., Haga I. R., Naik R. J., Atrih A., et al. (2017). IFI16 and cGAS cooperate in the activation of STING during DNA sensing in human keratinocytes. Nat. Commun. 8:14392. 10.1038/ncomms14392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anashkin V. A., Baykov A. A., Lahti R. (2017). Enzymes regulated via cystathionine β-synthase domains. Biochemisty 110 E3790–E3799. 10.1134/S0006297917100017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anashkin V. A., Salminen A., Tuominen H. K., Orlov V. N., Lahti R., Baykov A. A. (2015). Cystathionine β-Synthase (CBS) domain-containing pyrophosphatase as a target for diadenosine polyphosphates in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 290 27594–27603. 10.1074/jbc.M115.680272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aria V., Yeeles J. T. P. (2019). Mechanism of bidirectional leading-strand synthesis establishment at eukaryotic DNA replication origins. Mol. Cell. 73 199–211.e10. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif S. M., Varshney U., Vijayan M. (2017). Hydrolysis of diadenosine polyphosphates. Exploration of an additional role of Mycobacterium smegmatis MutT1. J. Struct. Biol. 199 165–176. 10.1016/j.jsb.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atencia E. A., Madrid O., Günther Sillero M. A., Sillero A. (1999). T4 RNA ligase catalyzes the synthesis of dinucleoside polyphosphates. Eur. J. Biochem. 261 802–811. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00338.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam S., Jouvet N., Jilani A., Vongsamphanh R., Yang X., Yang S., et al. (2008). Human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase plays a direct role in reactivating oxidized forms of the DNA repair enzyme APE1. J. Biol. Chem. 283 30632–30641. 10.1074/jbc.M801401200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhar M. A., Wright M., Kamal A., Nagy J., Miller A. D. (2014). Biotin-c10-AppCH2ppA is an effective new chemical proteomics probe for diadenosine polyphosphate binding proteins. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24 2928–2933. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.04.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J. C., Ames B. N. (1988). Alterations in levels of 5′-adenyl dinucleotides following DNA damage in normal human fibroblasts and fibroblasts derived from patients with Xeroderma pigmentosum. Mutat. Res. Mutat. Res. Lett. 208 87–93. 10.1016/S0165-7992(98)90005-90007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J. C., Jacobson M. K. (1986). Alteration of adenyl dinucleotide metabolism by environmental stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 83 2350–2352. 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. D., Holloway D. E., Swaminathan G. J., Acharya K. R. (2006). Crystal structures of eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN) in complex with the inhibitors 5′-ATP. Ap3A, Ap4A, and Ap5A. Biochemistry 45 416–426. 10.1021/bi0518592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltzinger M., Ebel J. P., Remy P. (1986). Accumulation of dinucleoside polyphosphates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under stress conditions. High levels are associated with cell death. Biochimie 68 1231–1236. 10.1016/S0300-9084(86)80069-80064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes L. D., Garrison P. N., Siprashvili Z., Guranowski A., Robinson A. K., Ingram S. W., et al. (1996). Fhit, a putative tumor suppressor in humans, is a dinucleoside 5′,5″′-P1P3-triphosphate hydrolase. Biochemistry 35 11529–11535. 10.1021/bi961415t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxi M. D., McLennan A. G., Vishwanatha J. K. (1994). Characterization of the HeLa Cell DNA polymerase α-associated Ap4A binding protein by photoaffinity labeling. Biochemistry 33 14601–14607. 10.1021/bi00252a028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxi M. D., Vishwanatha J. K. (1995). Uracil DNA-Glycosylase/glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate dehydrogenase is an Ap4A binding protein. Biochemistry 34 9700–9707. 10.1021/bi00030a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baykov A. A., Tuominen H. K., Lahti R. (2011). The CBS domain: a protein module with an emerging prominent role in regulation. ACS Chem. Biol. 6 1156–1163. 10.1021/cb200231c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessman M. J., Walsh J. D., Dunn C. A., Swaminathan J., Weldon J. E., Shen J. (2001). The Gene ygdP, Associated with the Invasiveness of Escherichia coli K1, Designates a Nudix Hydrolase, Orf176, Active on Adenosine (5′)-Pentaphospho-(5′)-adenosine (Ap5A). J. Biol. Chem. 276 37834–37838. 10.1074/jbc.M107032200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettendorff L., Wirtzfeld B., Makarchikov A. F., Mazzucchelli G., Frédérich M., Gigliobianco T., et al. (2007). Discovery of a natural thiamine adenine nucleotide. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3 211–212. 10.1038/nchembio867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochner B. R., Lee P. C., Wilson S. W., Cutler C. W., Ames B. N. (1984). AppppA and related adenylylated nucleotides are synthesized as a consequence of oxidation stress. Cell 37 225–232. 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90318-90310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone R., Cheng Y. C., Wolfenden R. (1986). Inhibition of thymidine kinase by P1-(adenosine-5′)-P5-(thymidine-5′)-pentaphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 261 5731–5735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brevet A., Chen J., Leveque F., Plateau P., Blanquet S. (1989). In vivo synthesis of adenylylated bis(5′-nucleosidyl) tetraphosphates (Ap4N) by Escherichia coli aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 86 8275–8279. 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brevet A., Coste H., Fromant M., Plateau P., Blanquet S. (1987). Yeast diadenosine 5′,5″′-P, P4-tetraphosphate alpha, beta-phosphorylase behaves as a dinucleoside tetraphosphate synthetase. Biochemistry 26 4763–4768. 10.1021/bi00389a025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brevet A., Plateau P., Best-Belpomme M., Blanquet S. (1985). Variation of Ap4A and other dinucleoside polyphosphates in stressed Drosophila cells. J. Biol. Chem. 260 15566–15570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. M., Gilmartin G. M. (2003). A mechanism for the regulation of Pre-mRNA 3′ processing by human cleavage factor Im. Mol. Cell. 12 1467–1467. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00453-452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse H. J., Wostmann C., Bakker E. P. (1992). The bactericidal action of streptomycin: membrane permeabilization caused by the insertion of mistranslated proteins into the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli and subsequent caging of the antibiotic inside the cells due to degradation of these pro. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138 551–561. 10.1099/00221287-138-3-551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmi-Levy I., Yannay-Cohen N., Kay G., Razin E., Nechushtan H. (2008). Diadenosine tetraphosphate hydrolase is part of the transcriptional regulation network in immunologically activated mast cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28 5777–5784. 10.1128/mcb.00106-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright J. L., Britton P., Minnick M. F., McLennan A. G. (1999). The IalA invasion gene of Bartonella bacilliformis encodes a (di)nucleoside polyphosphate hydrolase of the MutT motif family and has homologs in other invasive bacteria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 256 474–479. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Boonyalai N., Lau C., Thipayang S., Xu Y., Wright M., et al. (2013). Multiple catalytic activities of Escherichia coli lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LysU) are dissected by site-directed mutagenesis. FEBS J. 280 102–114. 10.1111/febs.12053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. G., Kowtoniuk W. E., Agarwal I., Shen Y., Liu D. R. (2009). LC/MS analysis of cellular RNA reveals NAD-linked RNA. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5 879–881. 10.1038/nchembio.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng N., Payne R. C., Evans Kemp W., Traut T. W. (1986). Homogeneous uridine kinase from Ehrlich ascites tumor: substrate specificity and inhibition by bisubstrate analogs. Mol. Pharmacol. 30 159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conyers G. B., Bessman M. J. (1999). The gene, ialA, associated with the invasion of human erythrocytes by Bartonella bacilliformis, designates a Nudix hydrolase active on dinucleoside 5′-polyphosphates. J. Biol. Chem. 274 1203–1206. 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coseno M., Martin G., Berger C., Gilmartin G., Keller W., Doublié S. (2008). Crystal structure of the 25 kDa subunit of human cleavage factor Im. Nucleic Acids Res. 36 3474–3483. 10.1093/nar/gkn079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coste H., Brevet A., Plateau P., Blanquet S. (1987). Non-adenylylated bis(5′-nucleosidyl) tetraphosphates occur in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and in Escherichia coli and accumulate upon temperature shift or exposure to cadmium. J. Biol. Chem. 262 12096–12103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deana A., Celesnik H., Belasco J. G. (2008). The bacterial enzyme RppH triggers messenger RNA degradation by 5′ pyrophosphate removal. Nature 451 355–358. 10.1038/nature06475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Despotović D., Brandis A., Savidor A., Levin Y., Fumagalli L., Tawfik D. S. (2017). Diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) - an E. coli alarmone or a damage metabolite? FEBS J. 284 2194–2215. 10.1111/febs.14113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]