Abstract

We present an 84-year-old man with erosion of the chemotherapy port on his chest wall. He had a history of colorectal cancer with liver metastases more than 20 years ago, when he underwent right hemicolectomy and liver resection. A hepatic artery infusion catheter was placed for targeted administration of chemotherapy for the liver metastases. Imaging showed the catheter had migrated into the small bowel lumen. We considered the best approach for removing the migrated catheter – either remove the catheter and accept the likelihood of a low-volume enterocutaneous fistula that may self-resolve, or explore the enterocutaneous tract with a view to small bowel resection. We discuss the advantages and disadvantages here.

Keywords: Enterocutaneous, Fistula, Chemotherapy, Port, Erosion

Case history

An 84-year-old man presented with erosion of the chemotherapy port on his mid-chest wall. He had a history of right colonic cancer with liver metastases 23 years ago. He underwent a right hemicolectomy followed by hepatic resection (segment 5/6) and placement of a hepatic artery infusion (HAI) catheter 6 months later through a laparotomy for administration of chemotherapy. He last received chemotherapy via the catheter 20 years ago and was lost to follow-up from the tertiary centre. He had had no episodes of abdominal pain or evidence of bleeding from migration of the catheter over the past 20 years.

The patient presented to our hospital eight months ago with cellulitis. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed a small underlying collection around the port site, with no sternal inflammation or erosion. There was evidence of the tip of the HAI catheter in the small bowel. He declined surgical intervention for removal of the port and was managed successfully with intravenous antibiotics.

On arrival, he was systemically well and his vital signs were stable. The port was on view at his mid-chest wall, with some purulent discharge (Fig 1). Abdominal examination was unremarkable. Biochemistry tests showed normal inflammatory markers. A CT scan of the abdomen confirmed the presence of a migrated HAI catheter in the small bowel (Fig 2). The common hepatic artery remained patent on the arterial phase of the scan.

Figure 1.

The port has eroded through the skin at the mid-chest wall (circled)

Figure 2.

(a) Computed tomography scout view of the abdomen showing the migrated hepatic artery infusion catheter located intraluminal of the small bowel (arrow). (b, c) Axial and sagittal views demonstrating the location of the catheter in the small bowel.

He was commenced on broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5g). He was taken to theatre for removal of the port. Intraoperatively, the port site wound was extended, and the port was disconnected from the catheter. Intraoperative fluoroscopy confirmed the distal part of the catheter was intraluminal of the small bowel (Fig 3a). Contrast was flushed through the catheter with intraoperative fluoroscopy to confirm the enterocutaneous tract (Fig 3b). The catheter was pulled out easily (Fig 3d). A repeat contrast fluoroscopy was performed through the existing enterocutaneous tract to ensure there was no extravasation of the contrast intraperitoneally (Fig 3c). The wound was debrided and packed with dressings.

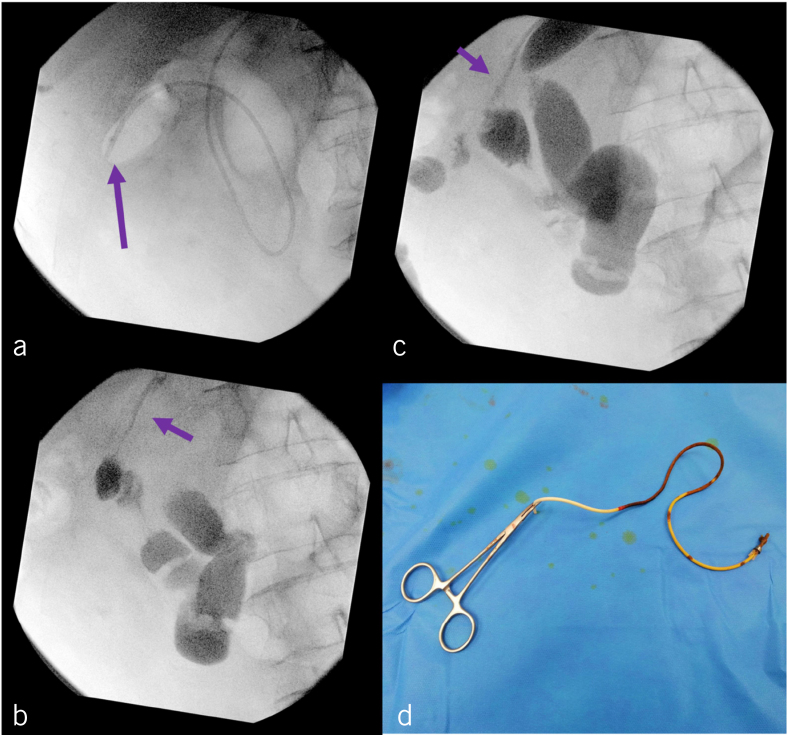

Figure 3.

(a) Intraoperative fluoroscopy showing the location of catheter in the small bowel (arrow). (b) Contrast placed through the catheter (arrow) to confirm the migrated catheter was in the small bowel rather than the hepatic artery. (c) Contrast placed through the fistula tract (arrow) to ensure no contract extravasation intraperitoneally after removal of the catheter. (d) The removed catheter in entirety.

He was discharged home on day 2 with daily dressing changes. There was no enteric content discharge during the dressing changes. At his last clinic review, the wound had healed completely.

Discussion

The management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer has evolved significantly over the past few decades, ranging from hepatic resections, to administration of systemic chemotherapy agents, to local radiofrequency ablations. Hepatic artery infusion of chemotherapy agents has been described since the 1960s as a potential alternative route for administration of variable targeted doses of chemotherapy into the liver for management of liver metastases and primary liver cancers.1 This approach is invasive, however, and requires a laparotomy for insertion of the catheter into the junction of the gastroduodenal artery and the common hepatic artery.1

The main complications associated with HAI catheters usually occur early; they include arterial and catheter thrombosis.2 There was no evidence of thrombosis in the common hepatic artery in our case. Other complications are related to the port and catheter itself, where erosions and infections can occur. We postulate that the metal tip at the distal end of the HAI catheter caused local inflammation and led to progressive erosion through the arterial wall and adjacent small bowel.

In a series of 544 cases, Allen and colleagues reported their experience with HAI catheters.3 Pump-related complications were reported in up to 22% of cases. Catheter displacement and erosion were reported in 18 and 4 patients, respectively.3

A review by Barnett and colleagues that compared the complications of HAI catheters over three decades showed that port- and catheter-related complications became relatively uncommon after 1990; they included catheter displacement (3%), broken catheter (3%), port infection (2%), wound infection (<1%) and skin necrosis (<1%).2

In our case, we considered two approaches – removal of the port with debridement of the wound and acceptance of a potential low-volume controlled enterocutaneous fistula tract, or exploration of the fistula tract with small bowel resection. We decided to proceed with the former, less invasive approach, as it carries a lower risk.

We followed the rationale that there was a high possibility that the catheter had created a well-formed enterocutaneous fistula. If the enterocutaneous tract does not completely heal, a further elective procedure can be planned to manage it definitively. Nonetheless, the patient should still be informed and consented about the possibility of a laparotomy if the catheter can not be removed with the former approach.

In summary, a less invasive approach should always be undertaken in this rare scenario before embarking on major surgical intervention.

References

- 1.Lewis HL, Bloomston M. Hepatic artery infusional chemotherapy. Surg Clin North Am 2016; : 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett KT, Malafa MP. Complications of hepatic artery infusion: a review of 4580 reported cases. Int J Gastrointest Cancer 2001; : 147–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen PJ, Nissan A, Picon AI et al. Technical complications and durability of hepatic artery infusion pumps for unresectable colorectal liver metastases: an institutional experience of 544 consecutive cases. J Am Coll Surg 2005; : 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]