Dear Editor,

As reported in this journal, SARS-CoV-2 has a prolonged detection rate in stool samples, although the clinical significance of this remains unclear.1 Other studies have shown that the virus is detected longer in stool, but its infectivity or replication status is not yet well-established. However, some association between the detection of SARS-CoV-2 subgenomic RNA (sgRNA) and virus isolation in cell culture has been observed.2, 3, 4, 5 On the other hand, virus detection in upper respiratory tract (URT) samples lasts, in general, up to the eighth day after symptom onset, with a decrease in detection beyond the fifth day.6 Many hospitalized patients suspected of having COVID-19 arrive late or when it is no longer possible to detect viral RNA in URT samples, thus imposing a problem on their clinical management given the pandemic. In order to better understand whether virus detection in stool could improve the diagnosis of COVID-19, we evaluated the detection of viral genomic RNA (gRNA) in 74 hospitalized patients admitted to the São Paulo university hospital with negative results in samples obtained from naso- or oropharyngeal swabs, including 3 patients with SARS-CoV-2-positive nasopharyngeal and stool samples as a control group. We also attempted to detect at least two different sgRNAs as possible markers of viral replication.

For RNA preparation from stool samples, ∼2.0 ng of stool was homogenized in 2.0 mL of sterile lactated Ringer's solution and centrifuged at 9,300 x g for one minute. 150 uL of supernatant was used for RNA extraction with the Quick-RNA Virus kit (Zymo Research, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

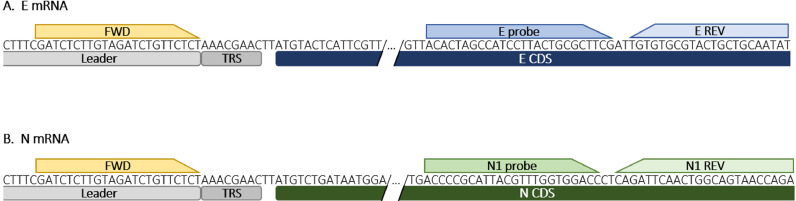

Molecular detection was performed by real-time RT-PCR. SARS-CoV-2 gRNA amplification was aimed at the Envelope (E) gene,6 and positive stool samples were used for sgRNAs aimed at the E6 and Nucleocapsid (N) messenger RNAs (mRNA). N mRNA was detected using the same forward primer as E sgRNA, with reverse primer and probe from the CDC USA N1 target protocol (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-panel-primer-probes.html), as shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Real-time RT-PCR oligonucleotide binding sites for amplification of E and N mRNAs. A) E mRNA. B) N mRNA. The leader sequence and transcription-regulating sequence (TRS) are shown in grey. The common forward primer is shown in yellow. The coding sequence (CDS), probe, and reverse primers for E and N are shown in blue and green, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The reactions were carried out as described elsewhere.7 The cycle threshold (Ct) values were used as a semi-quantitative parameter, meaning that the higher the RNA sample concentration, the lower the Ct value. The variation in Ct values for each sample between gRNA, their sgRNA counterparts, and between sgRNAs, were calculated as ΔCt.

Viral RNA was detected in 23.0% (17/74) of the stool samples, with a mean Ct value of 27.4 ± 6.0 (mean ± SD). In those positive samples, the N and E sgRNAs were detected in 94.11% (16/17) and 58.82% (10/17), respectively.

The ΔCt values were on average 7.22 ± 1.42 and 2.93 ± 1.83 higher for E and N sgRNAs, respectively (Table 1 ), corresponding to a lower sensibility in the order of 2 and 1 Log10, in relation to gRNA detection. The mean ΔCt value between E and N sgRNAs was 4.43 ± 0,61.

Table 1.

Ct values of gRNA and sgRNA in stool samples, and ΔCt.

| Patient | Threshold cycle values |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gRNA | sgRNA (E) | sgRNA (N) | ΔCt (sgE-gE) | ΔCt (sgN-gE) | ΔCt (sgE-sgN) | |

| 2920 | 15.93 | 21.10 | 16.93 | 5.17 | 1.00 | 4.17 |

| 2089* | 19.56 | 26.75 | 21.89 | 7.19 | 2.33 | 4.86 |

| 3201 | 21.95 | 30.93 | 26.22 | 8.98 | 4.27 | 4.71 |

| 2615 | 23.81 | 31.68 | 26.86 | 7.87 | 3.05 | 4.82 |

| 2449 | 23.92 | 32.47 | 27.00 | 8.55 | 3.08 | 5.47 |

| 3859 | 24.14 | 29.41 | 26.00 | 5.27 | 1.86 | 3.41 |

| 2555 | 26.59 | 33.07 | 29.00 | 6.48 | 2.41 | 4.07 |

| 4604 | 26.97 | 35.95 | 31.95 | 8.98 | 4.98 | 4.00 |

| 1724* | 27.16 | 33.32 | 29.00 | 6.16 | 1.84 | 4.32 |

| 3973 | 29.78 | 37.34 | 38.00 | 7.56 | 8.22 | −0.66† |

| 4478 | 30.04 | N.D. | 33.88 | – | 3.84 | – |

| 1450* | 33.68 | N.D. | 37.00 | – | 3.32 | – |

| 5153 | 33.84 | N.D. | 36.51 | – | 2.67 | – |

| 4485 | 34.10 | N.D. | N.D. | – | – | – |

| 4914 | 34.37 | N.D. | 36.38 | – | 2.01 | – |

| 2980 | 34.44 | N.D. | 36.00 | – | 1.56 | – |

| 4598 | 35.51 | N.D. | 36.02 | – | 0.51 | – |

| Mean ± SD | 27.99 ± 5.89 | 31.20 ± 4.66 | 30.54 ± 6.17 | 7.22 ± 1.42 | 2.93 ± 1.83 | 4.43 ± 0.61 |

*Positive controls. † non-computed value. Ct, threshold cycle. gRNA, genomic RNA. sgRNA, subgenomic RNA. E, envelope protein. N, nucleocapsid protein. ΔCt, the difference between Ct values of sgRNAs and gRNA. N.D., not detected.

The number of days after the onset of symptoms in patients with SARS-CoV-2 detected in stool varied from 2 to 37 days (mean of 13.3 ± 11), with a mean hospitalization time of 24.7 ± 16.7 days.

The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in stool samples could be related to the swallowing of respiratory secretions from the URT or residues of infected antigen-presenting immune cells,8 or, more likely, due to virus replication in gastrointestinal epithelial cells.4 However, the detection of viral RNA in stool was not related to gastrointestinal symptoms or COVID-19 severity.5 , 9

We were able to detect the SARS-CoV-2 sgRNA of the E and N genes in positive stool samples. Interestingly, the authors who developed the protocol for the detection of E sgRNA did not report any detection in the stool of hospitalized patients.6

When comparing the ΔCt between gRNA and their corresponding sgRNAs in each sample, we observed a difference of 1 to 2 log10 of sensitivity for mRNAs of N and E, respectively. Those differences could be explained by the fact that N sgRNA is the most abundantly expressed transcript during viral replication, followed by E sgRNA, in an amount of approximately 1.5 Log10 lower transcripts.10 We also roughly observed this difference between N and E sgRNA detection with a ΔCt = 4.43 ± 0.61. In spite of these findings, the detection of sgRNAs in clinical samples per se does not necessarily imply infectivity, which is more related to days post symptoms and viral load.2 , 3 , 6 However, the detection of more than one sgRNA could be used as a marker of viral replication, although further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

In conclusion, viral detection in stool improves the diagnosis of COVID-19, especially in patients who are suspected of being infected but with negative results in URT samples.

Declaration of Competing Interests

None.

Acknowledgements

L.V.L.M, L.K.S.L, G.R.B., A.P.C.C., and J.M.A.C. are fellows of the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil. D.D.C. is a fellow of the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil.

References

- 1.Walsh K.A., Jordan K., Clyne B., Rohde D., Drummond L., Byrne P., et al. SARS-CoV-2 detection, viral load and infectivity over the course of an infection. J Infect. 2020;81(3):357–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kampen J.J.Av., Vijver D.A.M.Cvd., Fraaij P.L.A., Haagmans B.L., Lamers M.M., Okba N., et al. Shedding of infectious virus in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): duration and key determinants. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.08.20125310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perera R., Tso E., Tsang O.T.Y., Tsang D.N.C., Fung K., Leung Y.W.Y., et al. SARS-CoV-2 virus culture and subgenomic RNA for respiratory specimens from patients with mild coronavirus disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(11):2701–2704. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.203219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiao F., Tang M., Zheng X., Liu Y., Li X., Shan H. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020 May;158(6):1831–1833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y., Chen L., Deng Q., Zhang G., Wu K., Ni L., et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):833–840. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Muller M.A., et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faico-Filho K.S., Conte D.D., de Souza Luna L.K., Carvalho J.M.A., Perosa A.H.S., Bellei N. No benefit of hydroxychloroquine on SARS-CoV-2 viral load reduction in non-critical hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Braz J Microbiol. 2020 Oct 27 doi: 10.1007/s42770-020-00395-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foladori P., Cutrupi F., Segata N., Manara S., Pinto F., Malpei F., et al. SARS-CoV-2 from faeces to wastewater treatment: what do we know? A review. Sci Total Environ. 2020 Nov 15;743 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J., Wang S., Xue Y. Fecal specimen diagnosis 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):680–682. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim D., Lee J.Y., Yang J.S., Kim J.W., Kim V.N., Chang H. The architecture of SARS-CoV-2 transcriptome. Cell. 2020;181(4):914–921. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.011. e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]