Abstract

Breast cancer, like many other cancers, is believed to be driven by a population of cells that display stem cell properties. Recent studies suggest that cancer stem cells (CSCs) are essential for tumor progression, and tumor relapse is thought to be caused by the presence of these cells. CSC-targeted therapies have also been proposed to overcome therapeutic resistance in breast cancer after the traditional therapies. Additionally, the metabolic properties of cancer cells differ markedly from those of normal cells. The efficacy of metabolic targeted therapy has been shown to enhance anti-cancer treatment or overcome therapeutic resistance of breast cancer cells. Metabolic targeting of breast CSCs (BCSCs) may be a very effective strategy for anti-cancer treatment of breast cancer cells. Thus, in this review, we focus on discussing the studies involving metabolism and targeted therapy in BCSCs.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Cancer stem cells, Metabolism, Oxidative phosphorylation, Tumor relapse, Target therapy

Core Tip: Breast cancer is thought to be driven by breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs). Recent studies suggest that BCSCs are essential for tumor progression and relapse, thus triggering therapeutic resistance in breast cancer after the traditional therapies. Moreover, the metabolic features of breast cancer cells are different from those of normal cells. BCSCs alter their metabolic profiles to fulfil bioenergetic and biosynthetic demands to maintain cancer cell survival. Here, we review the research regarding metabolism and targeted therapy in BCSCs.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women globally and also causes the greatest number of cancer-related deaths among women worldwide[1,2]. As a highly heterogeneous disease, breast cancer shows different morphological and physiological characteristics[3,4]. Therefore, it shows different clinical outcomes for different therapeutic strategies. Currently, assessment of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) status of the breast cancer specimens from the patients is considered a standard due to their predictive and prognostic implications[5-7]. Unfortunately, not all patients with ER or HER2 positive tumors respond to endocrine or anti-HER2 therapy[8,9]. Moreover, triple-negative breast cancer, negative for ER, PR, and excess HER2, is considered to be more aggressive and have a poorer prognosis than other types of breast cancer[10,11]. Therefore, we need to further understand the mechanism of breast cancer to develop more effective therapeutic strategies.

Cancer stems cells (CSCs), also known as tumor-initiating cells, are a subset of cancer cell groups that have the ability to renew themselves and promote tumor progression, recurrence, metastasis, and resistance to therapy[12,13]. CSCs have also been proposed as one of the determining factors contributing to tumor heterogeneity[14]. Therefore, the theory of CSCs provides a reasonable explanation for tumor heterogeneity. These subpopulations of cells are believed to be responsible for therapeutic resistance and tumor relapse[15,16].

With the deepening of research on breast CSCs (BCSCs), they are initially characterized by the expression of specific cell markers, such as high levels of cluster of differentiation 44 (CD44+) and low levels of cluster of differentiation 24 (CD24-)[17]. Similar to CD44+/CD24- cancer cells, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) is also one of the hallmarks of BCSCs[18]. Moreover, the prognosis of breast cancer patients with ALDH+ tumors was poorer than that of the ALDH- patients[19]. Interestingly, 500 ALDH+ BCSCs can form tumors in NOD/SCID mice[20]. The other markers mainly used to isolate and identify BCSCs in all types of breast cancer are CD133, EpCAM, CD166, LGR5, CD47, and ABCG2[21-23].

Emerging evidence shows that the metabolic properties of cancer cells are significantly different from those of normal cells[24,25]. Cancer cell metabolism is characterized by dysregulated glucose metabolism, fatty acid (FA) synthesis, and glutaminolysis, which lead to therapeutic resistance in cancer treatment[23,26,27]. Furthermore, a number of metabolic enzymes that are often upregulated in cancer cells may become novel targets for anticancer drug development[28,29]. Given the critical role of CSCs in tumors, targeting of the CSCs metabolism may provide new therapies to reduce therapeutic resistance and tumor relapse. Despite the importance of CSCs, there are few review articles summarizing therapeutic targeting of CSC metabolism, especially targeting of BCSCs metabolism. In this review, we summarize the important findings about therapeutic targeting of BCSC metabolism. First, we will describe the specific markers for identification and isolation of BCSCs. Then, the metabolic characteristics of BCSCs will be summarized. Finally, we will summarize the targeted therapies based on the metabolic characteristics of BCSCs.

BCSC MARKERS

CSCs were first identified by John Dick’s team in human acute myeloid leukemia in the late 1990s[30,31]. They provided the first evidence that human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a hierarchy of leukemic stem cell classes harboring the potential of self-renewal, propagation, and differentiation. A subpopulation of leukemia cells that expressed surface marker CD34 but not CD38 (CD34+/CD38-) is capable of initiating tumors in non-obese diabetic, severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice that were histologically similar to the donor. In solid tumors, CSCs were first demonstrated in breast cancer. A small subpopulation of CD44+/CD24- cells (100 cells) enriched from human breast cancer tissue were able to generate tumors in NOD/SCID mice. Differently, CD44-/CD24+ cells do not exhibit tumor growth, even at a very high cell number[32]. Since then, the existence of CSCs has been confirmed in various cancers.

To better understand the functions of BCSCs, most of the studies in BCSCs have been focused on the identification of biomarkers on BCSCs. As a receptor for hyaluronic acid, CD44 can interact with other ligands, such as osteopontin, collagen, and matrix metalloproteinase[33]. Although CD44+/CD24- cells have been proved to have the characteristics of BCSCs, CD44+/CD24- cells are not present in all types of breast cancer cells[34-37]. Therefore, more BCSCs markers are required to be found in breast cancer cells.

Several other proteins have been then identified as important markers for BCSCs, including ALDH, CD326 (EpCAM), and CD133[13]. Alternatively, increased activity of ALDH detected by the Aldefluor assay in breast cancer cells was identified as another marker of BCSCs. ALDH is able to detoxify a variety of endogenous and exogenous aldehydes and is required for the biosynthesis of retinoic acid (RA) and other regulators of cell functional molecules[38]. Downregulation of ALDH expression is accompanied by a decline in BCSC characteristics[39]. Upregulation of ALDH expression is usually found in malignant BCSCs and positively correlated with poor prognosis[38,40]. Importantly, the subpopulation of breast cancer cells with a CD44+/CD24- phenotype and high ALDH enzymatic activity has become the “gold standard” signature for BCSCs, because only 20 positive cells can be tumorigenic[41-43].

Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), a transmembrane glycoprotein, has been implicated in multiple cellular functions including cell adhesion[44]. Knockdown of EpCAM was found to reduce the proliferation, migration, and invasion of breast cancer cells[45,46]. Moreover, clinical studies also showed that EpCAM is upregulated in breast cancer cells and is associated with a poor prognosis[45,47]. Recently, EpCAM has been identified as a marker of BCSCs and participates in promoting bone metastasis by enhancing tumorigenicity. BALB/c mice inoculated with EpCAM positive cells had a high bone metastasis potential, implying a possible target for the treatment of bone metastases with EpCAM in BCSCs[48,49].

CD133, transmembrane single-chain glycoprotein, is also identified as an important surface marker of BCSCs[35]. Importantly, CD133 is the most commonly used marker for isolation of CSC population from different tumors including breast cancer[50]. In normal breast tissue, CD133 is not a stem cell marker and plays an important role in morphogenesis. Upregulation of CD133 is accompanied by the increased malignancy and multidrug resistance by enhancing phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt signaling in breast cancer cells[51]. CD133 positive cells isolated from breast cancer cells display increased capability of tumorigenicity, self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation into different types of cells[52]. Meanwhile, CD133 positivity means higher mortalities and poor prognosis among the breast cancer patients. CD133 expression was the highest in triple-negative breast cancer specimens[53]. Together, CD133 can be regarded as a useful surface marker for identifying BCSCs and a useful indicator for predicting prognosis in clinical practice.

In addition to the above mentioned markers of BCSCs, various potential markers for BCSCs were also identified from breast cancer cell lines. For example, activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM/CD166) predicts response to adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer[54]. Meanwhile, CD166+ cells are enriched for ERα and possess a BCSC phenotype[55]. ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 2 (ABCG2), which plays a key role in multi-drug resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs, also has been identified as an effective BCSC marker[56]. Leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) has been identified as a BCSC marker by maintaining the stemness through activating Wnt-regulated target genes in breast cancer[57]. CD47, also known as integrin associated protein (IAP), was found upregulated in BCSCs[58]. A function-blocking CD47 antibody was proved to suppress the stemness in triple-negative breast cancer cells[59]. MUC1, a tumor antigen of breast cancer known as CA153, is also expressed on BCSCs. MUC1 positive cancer cells have multiple characteristics of BCSCs[60]. Although many BCSC markers have been found by flow cytometry (summarized in Table 1), more differentiated BCSC markers usually change according to different subtypes of breast cancer cells, histological stage, and internal heterogeneity[60]. Moreover, there is no universal marker that is specific for identification of BCSCs. These BCSC markers mentioned above are also used to isolate other types of CSCs. In patients with breast cancer accompanied by other primary tumors, the use of BCSC markers is limited. Therefore, further studies are still needed to determine the function and mechanism of BCSC markers in breast cancer cells.

Table 1.

Breast cancer stem cell markers

|

Marker

|

Expression

|

Function

|

Ref.

|

| CD44 | High | Adhesion, intracellular signaling, cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, differentiation, migration, and invasion | Senbanjo et al[123], 2017 |

| CD24 | Low | Cell metastasis and proliferation | Jaggupilli et al[124], 2012 |

| ALDH1 | High | Cellular proliferation, differentiation, stemness, and self-protection | Tomita et al[40], 2016 |

| CD133 | High | Cellular differentiation | Glumac et al[52], 2018 |

| CD49f | High | Tumor initiation, metastasis, and chemoresistance | Meyer et al[125], 2010 |

| CD61 | High | Tumor initiation and metastasis | Zhu et al[126], 2019 |

| CD90 | High | Cell metastasis | Sauzay et al[127], 2019 |

| EpCAM | High | Cellular proliferation, migration, and invasion | Sauzay et al[128], 2018 |

CD44: Cluster of differentiation 44; CD24: Cluster of differentiation 24; ALDH1: Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1; CD133: Cluster of differentiation 133; CD49f: Cluster of differentiation 49f; CD61: Cluster of differentiation 61; CD90: Cluster of differentiation 90; EpCAM: Epithelial cell adhesion molecule.

METABOLIC FEATURES OF BCSCS

Metabolic adaptation is one of the hallmarks of cancer cells. Cancer cell metabolism is characterized by dysregulated glucose metabolism, FA synthesis, and glutaminolysis to provide constant support for the increased division rate[61-63]. The unique metabolic characteristics of cancer cells provide an effective strategy to treat cancer with metabolic targeted therapy. Cancer is a highly heterogeneous disease with different kinds of morphological and physiological characteristics[64]. Due to this characteristic of cancer cells, different clinical results are associated with different treatment strategies. Unfortunately, most studies do not consider the cellular heterogeneity present in cancer cells. CSCs are considered one of the determinants of cellular heterogeneity in cancer cells. Therefore, the strategy of switching cancer cell metabolism to CSC metabolism may solve the problem of heterogeneity of cancer cells during metabolic targeted therapy. Here, we summarize the studies about therapeutic targeting of BCSC metabolism. First, it is necessary to summarize the metabolic characteristics of BCSCs.

Due to the small number of studies on the metabolism of CSCs, especially BCSCs, the metabolic features of CSCs remain largely unknown[65]. Nonetheless, limited studies show that the metabolic characteristics of CSCs are different from those of normal cells and cancer cells. Glucose is an essential nutrient for CSCs like that of cancer cells. More specifically, CSCs (including BCSCs) were more glycolytic than other differentiated cancer cells[66]. CSCs show increased glucose uptake, lactate production, and ATP content compared with other differentiated cancer cells[67]. Several studies have supported that BCSCs showed enrichment of glycolytic proteins (such as PKM2 and LDHA), as well as increased pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase activities[68,69]. Meanwhile, the levels of glycolysis intermediates, such as fructose 1,6-diphospate, pyruvate, lactic acid, and ribose 5-phosphate were found to be significantly higher in BCSCs[70]. Thus, the inhibitors of glycolysis are expected to be used to treat cancer with metabolic targeted therapy. Reports have demonstrated that inhibitors of glycolysis reduce the proliferation of BCSCs[21,69].

Although studies have shown that BCSCs are dependent on glycolysis, other studies have shown that BCSCs may also depend on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) metabolism[71-73]. Compared to their differentiated progeny, BCSCs are more dependent on OXPHOS[73,74]. BCSCs produces less lactate and lower levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by OXPHOS[69]. Meanwhile, BCSCs have more functional mitochondria, and have higher ATP content by OXPHOS[75]. Interestingly, emerging evidence shows that BCSCs have a preference for OXPHOS metabolism in the proliferative state[69,72,76]. In the quiescent state, BCSCs exhibit a higher glycolytic rate[10,75]. Moreover, metabolism of BCSCs is plastic. The different metabolic patterns of BCSCs might be due to their distinctive molecular characteristics[72,77,78]. It was demonstrated that the metabolic switch from OXPHOS to aerobic glycolysis was essential for the maintenance of CD44+/CD24-/ EpCAM+ BCSCs in response to the decreased ROS levels[79]. It has been observed that BCSCs display two interchangeable states: Quiescent mesenchymal-like (M) state and proliferative epithelial-like (E) state[80,81]. M-BCSCs are characterized by elevated ALDH activity and proliferative capacity. Differently, E-BCSCs exhibit CD44+/CD24- cell surface marker expression and quiescent state[78,82].

FA is the metabolic intermediates of various nutrients in cells, which are essential for maintaining the structure and function of cell membranes, energy storage, and signal transduction[83]. In addition to glucose metabolism, cells also generate energy by breaking down FA by FA oxidation (FAO)[84]. FAO is also important for cancer cell survival and chemotherapy resistance[26]. CSCs needs to metabolize FA through FAO to generate energy to maintain survival[85]. It was reported that CD44+/CD24- BCSCs contain high levels of lipid droplets and the number of lipid droplets correlates with the stemness of breast cancer cells. Small molecule chemical inhibitors targeting lipid metabolism directly impact the mammosphere formation of BCSCs. It was demonstrated that JAK/STAT3 signaling regulates lipid metabolism, which promotes BCSC stemness and breast cancer cell chemoresistance. Inhibiting JAK/STAT3 signaling or blocking FAO can prevent BCSC maintenance and breast cancer cell chemoresistance. Drug-induced inhibition of mitochondrial FAO with etomoxir impairs NADPH production and increases the levels of ROS. Importantly, etomoxir significantly inhibits tumorsphere formation of radiation-derived BCSCs. Promyelocytic leukemia (PML) gene was enriched in triple-negative breast cancers. It was reported that PML acted as a potent activator of PPAR signaling and fatty acid oxidation. Recent studies have demonstrated the critical role of PML in CSCs. Therefore, BCSCs from triple-negative breast cancers may depend on FA oxidation. Until now, there are few studies on the metabolic characteristics of BCSCs. Thus, well-defined features of BCSC metabolism still need to be depicted.

METABOLIC TARGETED THERAPY OF BCSCS

In view of the metabolic features of BCSCs, we summarize the current alternative therapeutics that target BCSC metabolism. BCSCs have more efficient mitochondria, and thus they are more efficient in performing OXPHOS[74]. Therefore, targeting OXPHOS may be an effective strategy to eliminate BCSCs. Transcription co-activator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1 alpha (PGC1α) is a key transcriptional regulator of several metabolic pathways including oxidative metabolism and lipogenesis[86]. PGC1α was found to mediate mitochondrial biogenesis and OXPHOS in cancer cells to enhance metastasis[87,88]. Upregulated PGC1α expression was found in breast cancer metastases both in breast cancer xenografts and patients[89]. Some studies showed that the plasma concentration of PGC1α is higher than that of the healthy control group[86]. Meanwhile, there is a positive correlation between high expression of PGC1α and poor prognosis in breast cancer[89]. Estrogen-related receptor α (ERRα) is a cofactor of PGC1α, which is also required for the transcription of nuclear mitochondrial genes and mitochondrial biogenesis[90]. XCT790, an ERRα-specific inverse antagonist, functions as a specific inhibitor of the ERRα-PGC1α signaling pathway that is involved in the control of mitochondrial biogenesis[91]. XCT790 has been found to reduce the stemness of BCSCs with a CD44+/CD24- phenotype and is accompanied by the inhibition of several signal pathways related to the maintenance of BCSCs[18].

Given that XCT790 significantly reduces OXPHOS and stemness of BCSCs, other mitochondrial inhibitors should also be considered, especially some drugs that have been proven safe through clinical trials[92]. For instance, the antibiotic doxycycline is widely used to treat infections such as chest infections, skin infections, rosacea, dental infections, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), as well as many other rare infections[93]. Doxycycline, as a non-toxic inhibitor of mitochondrial OXPHOS, was reported to effectively reduce bone metastasis in an in vivo pre-clinical murine model of human breast cancer[94]. Importantly, a phase II clinical trial for the use of oral doxycycline in early breast cancer patients shows that doxycycline can selectively eradicate BCSCs in breast cancer patients, which is consistent with a decrease in CD44 and ALDH expression[94].

Niclosamide, a clinically approved drug used to treat tapeworm infestations, is known to uncouple mitochondrial OXPHOS during tapeworm eradicating by diminishing the potential of the inner mitochondrial membrane to inhibit OXPHOS[95]. Niclosamide has been found to inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells with little toxicity to nonmalignant tissues[96]. Moreover, niclosamide can effectively inhibit the proliferation, migration, and invasion of human breast cancer cells at low concentrations, and induce significant apoptosis at high concentrations[97]. Importantly, it was showed that niclosamide treatment resulted in decreased self-renewal signaling pathway activity of BCSCs and increased cytotoxicity against BCSCs with a CD44+/CD24- or ALDH+ phenotype[98].

Another FDA-approved drug tri-phenyl-phosphonium (TPP), a non-toxic and biologically active molecule, can be delivered to and accumulated within the mitochondria of living cells by inhibiting OXPHOS metabolism and activating glycolysis[99]. Interestingly, TPP, applied in combination with vitamin C and berberine, was proved to inhibit the propagation of BCSCs[99,100]. Both vitamin C and berberine are natural compounds. Vitamin C enables the inhibition of glycolysis, while berberine can inhibit the OXPHOS metabolism.

Disulfiram (DSF), an FDA-approved small molecule used in the treatment of chronic alcoholism, can prevent the re-expression of stemness genes and the appearance of BCSC properties in breast cancer cells after radiation[101]. DSF was also demonstrated to disturb the function of mitochondria and inhibit the OXPHOS metabolism[102,103]. Due to the characteristics of targeting BCSCs, DSF has also been shown to successfully reverse the resistance and cross-resistance of acquired paclitaxel-resistant triple-negative breast cancer cells[104,105]. As a drug that has been clinically applied, we should comprehensively evaluate whether DSF can be re-used as a BCSC inhibitor to reverse acquired pan-chemical resistance.

In summary, BCSCs mainly depend on OXPHOS metabolism to provide energy, which results in increased mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm)[106]. Disruption of mitochondrial metabolic function is one of the effective ways to eliminate BCSCs. This can be also used to increase the delivery of drugs to the mitochondria of BCSCs.

CD44 is the most typical BCSC marker. CD44 can be cleaved by proteolytic cleavage and releases the intracellular domain (CD44ICD). Subsequently, CD44ICD interacts with various stemness factors, including SOX2, NANOG, and OCT4, in breast cancer cells. Meanwhile, CD44ICD promotes the glycolysis pathway of BCSCs via enhancing PFKFB4-mediated glycolysis by binding and activating the promoter region of PFKFB4[107]. Therefore, inhibition of CD44 may provide potential therapeutic target against CD44+ BCSCs. It was reported that ablation of CD44 can induce glycolysis-to-OXPHOS transition through modulation of the c-Src-Akt-LKB1-AMPKα pathway in breast cancer cells[108]. Thus, the small molecule chemical inhibitor of CD44 may be more effective than CD44 monoclonal antibody in targeting BCSCs.

ALDH is one of the effective hallmarks of BCSCs and is an independent prognostic marker to predict metastasis and poor patient outcome in breast cancer[35,108]. As a mitochondrial methylmalonate semialdehyde dehydrogenase, ALDH is also one of the functional regulators of BCSCs and therapeutic resistance[19,21]. It has been shown that the HER2+/CD44+/CD24- subpopulation of breast cancer cells display enriched ALDH activity, tumorigenic potential, and radio-resistance[109]. Suppressing ALDH activity can prevent the expression of BCSC related genes and the BCSC properties in breast cancer cells after radiation[110]. In addition, ALDH can metabolize chemotherapeutic drugs into non-toxic compounds[111]. The characteristics of ALDH are responsible for the drug resistance of cancer cells, thus providing a potential target for the targeted therapy of BCSCs.

The progressive growth of solid tumors results in abnormal blood vessels to supply defective oxygen to tumor cells[112,113]. Recent reports show that BCSCs are stimulated in a hypoxic tumor microenvironment[114,115]. The undifferentiated phenotype of breast cancer cells strongly correlates with tumor hypoxia[116]. Under normoxic condition, stem cells lose their stemness characteristics[117]. Although the mechanism by which hypoxia promotes the generation of CSCs is unknown, doxycycline mentioned above as an OXPHOS inhibitor was reported to inhibit hypoxia-induced BCSCs[82]. Therefore, hypoxia-induced BCSC generation may be achieved by altering cell metabolism.

In addition to glucose metabolism, FA and cholesterol metabolism plays an important role in maintaining the stemness of CSCSs[118]. FA is metabolic intermediates of various nutrients in cells, which are essential for maintaining the functions of the cells[83]. FAO is also important for cancer cell survival and promotes chemotherapy resistance[85]. CSCs metabolize FA through the FAO catabolic pathway to generate energy to maintain survival[119]. Besides, increased cholesterol biosynthesis was proved as a key feature of BCSCs that affects patient outcomes[118,120]. It was demonstrated that simvastatin, an inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl–coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, specifically inhibits endogenous cholesterol synthesis in all of the animal cells[121]. Simvastatin has been shown to inhibit mammosphere formation and growth of BCSCs from patient-derived xenograft (PDX) tumors derived from triple-negative breast cancer[120]. Bisphosphonate, a drug widely used to reduce the incidence of breast cancer bone metastases, has been shown to significantly eliminate the formation of BCSCs[122]. Until now, there are few studies on the metabolic characteristics of BCSCs. Thus, well-defined features of BCSC metabolism still need to be depicted.

CONCLUSION

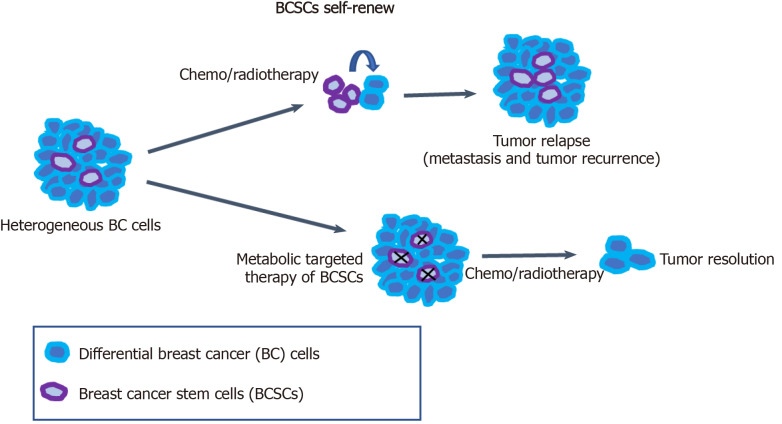

Breast cancer is a highly heterogeneous disease, and this high heterogeneity is a challenge to targeted treatment for breast cancer and other cancers. BCSCs have been considered to be an important cause of tumor heterogeneity and responsible for therapeutic resistance and tumor relapse. Therefore, the selective elimination of BCSCs at the root of breast cancer cells provides an effective therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment. Targeting the specific metabolic characteristics of BCSCs can promote the differentiation of BCSCs to reverse drug resistance and tumor metastasis in tumor therapy (Figure 1). BCSCs have been demonstrated to rely on OXPHOS metabolism for energy supply. Meanwhile, FA and cholesterol syntheses also contribute to BCSC maintenance. Thus, dual inhibition of metabolic pathways may be a better way to eliminate heterogeneous BCSCs.

Figure 1.

Metabolic targeted therapy of breast cancer stem cells. Breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) have been demonstrated to contribute to tumor heterogeneity and relapse (metastasis and tumor recurrence). The metabolic features of BCSCs significantly differ from those of non-BCSC differentiated tumor cells. Conventional chemotherapy or radiotherapy can effectively kill breast cancer cells, thereby dramatically reducing tumor size. The remaining BCSCs can survive and enhance tumor relapse due to their ability to establish higher invasiveness and resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. A combination treatment with metabolic targeted therapy of BCSCs and conventional therapy could be a more effective strategy to treat breast cancer. BCSCs: Breast cancer stem cells; BC: Breast cancer.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: July 1, 2020

First decision: July 30, 2020

Article in press: September 27, 2020

Specialty type: Biochemistry and molecular biology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ortiz-Sanchez E, Wang G S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

Contributor Information

Xu Gao, Department of Breast Surgery, Yiwu Maternity and Children Hospital, Yiwu 322000, Zhejiang Province, China. gao.xu.199@gmail.com.

Qiong-Zhu Dong, Department of General Surgery, Cancer Metastasis Institute, Institutes of Biomedical Sciences, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

References

- 1.McMillan EM, McKenna WB, Milne CM. Guidelines on preparing a medical report for compensation purposes. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:489–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb04547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harbeck N, Penault-Llorca F, Cortes J, Gnant M, Houssami N, Poortmans P, Ruddy K, Tsang J, Cardoso F. Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:66. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gambert P, Lallemant C, Andre JL, Athias A, Bourquard R, Pierson M, Padieu P. Cholesterol content of serum lipoprotein fractions in children maintained on chronic hemodialysis. Clin Chim Acta. 1981;110:295–300. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(81)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mangos JA, Boyd RL, Loughlin GM, Cockrell A, Fucci R. Transductal fluxes of water and monovalent ions in ferret salivary glands. J Dent Res. 1981;60:86–90. doi: 10.1177/00220345810600011701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allison KH, Hammond MEH, Dowsett M, McKernin SE, Carey LA, Fitzgibbons PL, Hayes DF, Lakhani SR, Chavez-MacGregor M, Perlmutter J, Perou CM, Regan MM, Rimm DL, Symmans WF, Torlakovic EE, Varella L, Viale G, Weisberg TF, McShane LM, Wolff AC. Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Testing in Breast Cancer: ASCO/CAP Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1346–1366. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unger S, Medici TC. [Does the manner of smoking affect chronic obstructive airway diseases and bronchial cancer? Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1983;113:104–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boaz NT, Ninkovich D, Rossignol-Strick M. Paleoclimatic setting for Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. Naturwissenschaften. 1982;69:29–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00441096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maj S, Mendek E, Snigurowicz J, Kraj M, Michalak T, Słomkowski M, Apel D. Acute myeloblastic leukemia in patients with multiple myeloma. Mater Med Pol. 1982;14:21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyle RA, Shampo MA. Eduard Buchner. JAMA. 1981;245:2096. doi: 10.1001/jama.245.20.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohman DE, Cryz SJ, Iglewski BH. Isolation and characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO mutant that produces altered elastase. J Bacteriol. 1980;142:836–842. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.3.836-842.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen JG, Galloway DB, Ehsanullah RS, Ruane RJ, Bird HA. The effect of bromazepam (Lexotan) administration on antipyrine pharmacokinetics in humans. Xenobiotica. 1984;14:321–326. doi: 10.3109/00498258409151418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin JR. Historical summary of visual fields methods. J Am Optom Assoc. 1980;51:833–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clauss LC. General information on dimethylpolysiloxane. Minerva Chir. 1983;38:863–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hozaki H. [Anal neurosis] Nihon Daicho Komonbyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1971;23:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danis A, Simons M, Dozinel R. [Surgical treatment of coxarthrosis. Current results] Acta Orthop Belg. 1965;31:719–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rich RR, Rogers DK, Leaders FE. Mesenchymal metaplasia of the chick chorioallantoic membrane; a non-specific response to selected stimuli. Exp Cell Res. 1965;40:96–103. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kochetkova VA. [Modification of a micromethod for determining leukocyte migration inhibition and its significance in oncological patients] Lab Delo. 1980:744–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta JN. Forty-third All-India Medical Conference Jabalpur: December 1967: Inaugural address. J Indian Med Assoc. 1968;50:238–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshinoya S, Cox RA, Pope RM. Circulating immune complexes in coccidioidomycosis. Detection and characterization. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:655–663. doi: 10.1172/JCI109901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson JD, Flynn EP, Kirkpatrick JB. Protein-losing enteropathy and intestinal bleeding. The role of lymphatic-venous connections. Ann Intern Med. 1966;64:628–635. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-64-3-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green RA. Activated coagulation time in monitoring heparinized dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1980;41:1793–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akbar Samadani A, Keymoradzdeh A, Shams S, Soleymanpour A, Elham Norollahi S, Vahidi S, Rashidy-Pour A, Ashraf A, Mirzajani E, Khanaki K, Rahbar Taramsari M, Samimian S, Najafzadeh A. Mechanisms of cancer stem cell therapy. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;510:581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook MK, Madden M. Iron granules in plasma cells. J Clin Pathol. 1982;35:172–181. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei Q, Qian Y, Yu J, Wong CC. Metabolic rewiring in the promotion of cancer metastasis: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Oncogene. 2020;39:6139–6156. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01432-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narro JR, Vandale S, Ruiz de Chávez M. [Morbidity in primary medical services in the jurisdiction of Huamantla, Tlaxcala] Salud Publica Mex. 1981;23:183–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kersh CR, Hazra TA. Mediastinal germinoma: two cases. Va Med. 1985;112:42–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campos Jde S, Delgado JA. [Use of a new thioxanthene in psychiatry] Hospital (Rio J) 1968;73:1619–1625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammond JE. Anaesthesia for laparoscopy: alfentanil and fentanyl compared. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1984;66:148–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans B, Iwayama T, Burnstock G. Long-lasting supersensitivity of the rat vas deferens to norepinephrine after chronic guanethidine administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973;185:60–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, Minden M, Paterson B, Caligiuri MA, Dick JE. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kayser K, Burkhardt HU, Jacob W. The regional registry of gastro-intestinal cancer North Baden (2.2 million inhabitants) Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1978;380:155–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00430622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer C, Turnbull AD. Diffuse interstitial pneumonia in immunocompromised hosts. Curr Probl Cancer. 1979;4:58–65. doi: 10.1016/s0147-0272(79)80047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abraham BK, Fritz P, McClellan M, Hauptvogel P, Athelogou M, Brauch H. Prevalence of CD44+/CD24-/low cells in breast cancer may not be associated with clinical outcome but may favor distant metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1154–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DA Cruz Paula A, Lopes C. Implications of Different Cancer Stem Cell Phenotypes in Breast Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:2173–2183. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holm S. Private hospitals in public health systems. Hastings Cent Rep. 1989;19:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bai X, Ni J, Beretov J, Graham P, Li Y. Cancer stem cell in breast cancer therapeutic resistance. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;69:152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flaherty CF, McCurdy ML, Becker HC, D'Alessio J. Incentive relativity effects reduced by exogenous insulin. Physiol Behav. 1983;30:639–642. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(83)90234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nielsen C. [Relaxing of unity and membership democracy in the Danish Nursing Council] Sygeplejersken. 1980;80:9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weber G. [Practical orthocryl technic] Quintessenz. 1969;20:93–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reylon V, Siddiqui HH. Anti-spasmogenic effect of cyproheptadine on guinea-pig ileum. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1983;27:342–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amatuni VG, Pirumian MS. [Role of the hereditary factor in the genesis of chronic bronchitis] Ter Arkh. 1984;56:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosendorff C. Indoramin in the hypertensive patient with concomitant disease: clinical experience. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1986;8 Suppl 2:S93–S97. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198600082-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madsen IM. [From the health administration. Not simply a question about self-determination] Sygeplejersken. 1983;83:22–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slater G, Papatestas AE, Tartter PI, Mulvihill M, Aufses AH Jr. Age distribution of right- and left-sided colorectal cancers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77:63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang D, Yang L, Liu X, Gao J, Liu T, Yan Q, Yang X. Hypoxia modulates stem cell properties and induces EMT through N-glycosylation of EpCAM in breast cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:3626–3633. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen P, Connetta B, Dix D, Flannery J. The incidence of hematologic tumours: a cellular model for the age dependence. J Theor Biol. 1981;90:427–436. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(81)90322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janssens L, Eycken M, Vanderschueren D, Van Baarle A, Beelaerts W, Denekens J, De Baere H. Collagenous colitis. Report of three cases and review of the literature. Acta Clin Belg. 1988;43:27–33. doi: 10.1080/17843286.1988.11717904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hiraga T, Ito S, Nakamura H. EpCAM expression in breast cancer cells is associated with enhanced bone metastasis formation. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:1698–1708. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quigley HA, Addicks EM. Chronic experimental glaucoma in primates. I. Production of elevated intraocular pressure by anterior chamber injection of autologous ghost red blood cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1980;19:126–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pearce-McCall D, Newman JP. Expectation of success following noncontingent punishment in introverts and extraverts. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50:439–446. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.2.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Filson DP, Bloomfield VA. Shell model calculations of rotational diffusion coefficients. Biochemistry. 1967;6:1650–1658. doi: 10.1021/bi00858a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parnell RW, Cross KW, Wall M. Changing use of hospital beds by the elderly. Br Med J. 1968;4:763–765. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5633.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ihnen M, Müller V, Wirtz RM, Schröder C, Krenkel S, Witzel I, Lisboa BW, Jänicke F, Milde-Langosch K. Predictive impact of activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM/CD166) in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:419–427. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9879-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pashkov BM. [Peculiarities of the clinical picture of some dermatoses localized in the buccal mucosa] Sov Med. 1969;32:114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ji X, Lu Y, Tian H, Meng X, Wei M, Cho WC. Chemoresistance mechanisms of breast cancer and their countermeasures. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;114:108800. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jatkar PR, Kreier JP. Pathogenesis of anaemia in anaplasma infection II--Auto-antibody and anaemia. Indian Vet J. 1969;46:560–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goodman MG. Mechanism of synergy between T cell signals and C8-substituted guanine nucleosides in humoral immunity: B lymphotropic cytokines induce responsiveness to 8-mercaptoguanosine. J Immunol. 1986;136:3335–3340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roth EM, Chambers AN. Compendium of human responses to the aerospace environment. 8. Vibration. NASA CR-1205 (2) NASA Contract Rep NASA CR. 1968:8–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mee AS, Bornman PC, Marks IN. Conservative surgery in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Br J Surg. 1984;71:423–424. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800710606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Merialdi A, Padovani E, Spreafichi F. [On the mechanism of the colpocytological changes during gonado-stimulating therapy with clomiphene] Quad Clin Ostet Ginecol. 1968;23:709–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bizzozero OA, Soto EF, Pasquini JM. Mechanisms of transport and assembly of myelin proteins. Acta Physiol Pharmacol Latinoam. 1984;34:111–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shampo MA, Kyle RA. Emily Perkins Bissell. JAMA. 1981;245:163. doi: 10.1001/jama.245.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seller MJ. Ethical aspects of genetic counselling. J Med Ethics. 1982;8:185–188. doi: 10.1136/jme.8.4.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bruyère R. [Gynecologic examinations] Union Med Can. 1965;94:799–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sasaki Y, Takahashi H, Aso H, Hikosaka K, Hagino A, Oda S. Insulin response to glucose and glucose tolerance following feeding in sheep. Br J Nutr. 1984;52:351–358. doi: 10.1079/bjn19840101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Copley AL. [On the physiological roles of fibrinogen and fibrin] Postepy Biochem. 1968;14:343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mathewson JW. Shock in infants and children. J Fam Pract. 1980;10:695–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wittmann HG. Structure and evolution of ribosomes. Mol Biol Biochem Biophys. 1980;32:376–397. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-81503-4_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ghanbari Movahed Z, Rastegari-Pouyani M, Mohammadi MH, Mansouri K. Cancer cells change their glucose metabolism to overcome increased ROS: One step from cancer cell to cancer stem cell? Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;112:108690. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Norvell JE, Lower RR. Degeneration and regeneration of the nerves of the heart after transplantation. Transplantation. 1973;15:337–344. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197303000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bubnova MM, Martynova MI, Kartelishev AV, Kniazev IuA, Rybina LN, Sapelkina LV, Skripkina VM, Tsyvil'skaia LO. [Experience in the management of children with diabetes mellitus] Vopr Okhr Materin Det. 1965;10:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boyle K. Power in nursing: a collaborative approach. Nurs Outlook. 1984;32:164–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Decroix G. [Attitude of the physician to inoperable cancer of the lung] Rev Prat. 1973;23:1245–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cripps J, Rudd A, Ebers GC. Birth order and multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1982;66:342–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1982.tb06854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Silva D, GuimarãesC [Current aspect of syphilis in Belém o Pará] An Bras Dermatol. 1966;41:213–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Votteler TP. Surgical separation of conjoined twins. AORN J. 1982;35:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(07)62019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smith WD, Bacon HE. Experience with a new antibiotic agent as an adjunct to colon surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 1967;10:322–324. doi: 10.1007/BF02617147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Joven JC, Mabilangan LM, Santos-Jesalva PM. Clinical trials with bephenium hydroxy naphthoate in intestinal parasitism. J Philipp Med Assoc. 1965;41:667–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bershteĭn LM, Pozharisskiĭ KM, Dil'man VM. [Effect of miskleron (clofibrate) on dimethylhydrazine induction of intestinal tumors in rats] Biull Eksp Biol Med. 1980;90:350–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gooding AJ, Schiemann WP. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Programs and Cancer Stem Cell Phenotypes: Mediators of Breast Cancer Therapy Resistance. Mol Cancer Res. 2020;18:1257–1270. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-20-0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lake AP, Bramwell RG. Male midwives. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;284:1952. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6333.1952-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ciznár I, Hostacká A. [Toxic properties of Proteus morganii] Cesk Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 1983;32:126–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Alsina M. [What is your diagnosis? (Cutaneous leishmaniasis)] Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1982;10:353–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fregly MJ. Effect of hydrochlorothiazide on preference threshold of rats for NaCl solutions. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1967;125:1079–1084. doi: 10.3181/00379727-125-32281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Glasgow JE, Bagdasarian A, Colman RW. Functional alpha 1 protease inhibitor produced by a human hepatoma cell line. J Lab Clin Med. 1982;99:108–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ahmed SS, Nussbaum M. Development of pulmonary edema related to heparin administration. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:126–128. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tolor A, Barbieri RJ. Different facets of sex anxiety. Percept Mot Skills. 1981;52:546. doi: 10.2466/pms.1981.52.2.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goulston SJ, McGovern VJ. The nature of benign strictures in ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 1969;281:290–295. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196908072810603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oscai LB, Caruso RA, Wergeles AC. Lipoprotein lipase hydrolyzes endogenous triacylglycerols in muscle of exercised rats. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1982;52:1059–1063. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.4.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ashbell TS. The storage of split-skin grafts on their donor sites. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;50:178–179. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197208000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Argenziano Cutolo A, Skoff G. [I. Migration of elements from pesticides into plants] Boll Chim Farm. 1988;127:176–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Siguier M, Molina JM. Doxycycline Prophylaxis for Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infections: Promises and Perils. ACS Infect Dis. 2018;4:660–663. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Katrukha SP, Shitov NN, Kukes VG. [Determination of plasma concentrations of acetoacetic and pyruvic acids by high pressure liquid chromatography] Lab Delo. 1983:33–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Miura K. [Histopathologic studies on epithelial proliferation in the peripheral region of the lung with special consideration of tumorlets] Gan No Rinsho. 1967;13:1104–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Carpenter RL, Mulroy MF. Edrophonium antagonizes combined lidocaine-pancuronium and verapamil-pancuronium neuromuscular blockade in cats. Anesthesiology. 1986;65:506–510. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bahadur P, Aurora AL, Sibbal RN, Prabhu SS. Tuberculosis of mammary gland. J Indian Med Assoc. 1983;80:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Platts MM, Anastassiades E. Dialysis encephalopathy: precipitating factors and improvement in prognosis. Clin Nephrol. 1981;15:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Poradovský K, Rosíval L, Balázová G, Fric D, Truska P, Rippel A. [Pollution of the environment with lead] Cesk Gynekol. 1984;49:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Romanelli R. [Congenital abnormalities of the atrioventricular ostia and the annexed valves: report of a case of an extra hole in the posterolateral cuspis of the mitral valve] Pathologica. 1967;59:281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gay T, Pankey GA, Beckman EN, Washington P, Bell KA. Fatal CNS trichinosis. JAMA. 1982;247:1024–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hiraide F, Sawada M, Inouye T, Miyakogawa N, Tsubaki Y. The fiber arrangement of the pathological human tympanic membrane. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1980;226:93–99. doi: 10.1007/BF00455407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Facer P, Bishop AE, Polak JM. Immunocytochemistry: its applications and drawbacks for the study of gut neuroendocrinology. Invest Cell Pathol. 1980;3:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Johnston PG, Zucker I. Lability and diversity of circadian rhythms of cotton rats Sigmodon hispidus. Am J Physiol. 1983;244:R338–R346. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1983.244.3.R338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li Y, Shen J, Fang M, Huang X, Yan H, Jin Y, Li J, Li X. The promising antitumour drug disulfiram inhibits viability and induces apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:1062–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yadav RV, Dhawan IK, Rao BN. Obstructive jaundice and carcinoma of the gallbladder. Int Surg. 1969;52:240–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rizzoli RE, Murray TM, Marx SJ, Aurbach GD. Binding of radioiodinated bovine parathyroid hormone-(1-84) to canine renal cortical membranes. Endocrinology. 1983;112:1303–1312. doi: 10.1210/endo-112-4-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nam K, Oh S, Shin I. Ablation of CD44 induces glycolysis-to-oxidative phosphorylation transition via modulation of the c-Src-Akt-LKB1-AMPKα pathway. Biochem J. 2016;473:3013–3030. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.van der Drift JF, Brocaar MP, van Zanten GA. The relation between the pure-tone audiogram and the click auditory brainstem response threshold in cochlear hearing loss. Audiology. 1987;26:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gabe M, Pompidou A, Schramm B. [Staining of polysaccharides with sudan black B after esterification] Histochemie. 1972;30:297–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00279778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gaito J, Gaito ST. The effect of several intertrial intervals on the 1 Hz interference effect. Can J Neurol Sci. 1981;8:61–65. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100042864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Odita JC, Ugbodaga CI. The metacarpal index of normal Nigerian children. Pediatr Radiol. 1983;13:33–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00975663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kon OL. An antiestrogen-binding protein in human tissues. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:3173–3177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mueller SM. Neurologic complications of phenylpropanolamine use. Neurology. 1983;33:650–652. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hajizadeh F, Okoye I, Esmaily M, Ghasemi Chaleshtari M, Masjedi A, Azizi G, Irandoust M, Ghalamfarsa G, Jadidi-Niaragh F. Hypoxia inducible factors in the tumor microenvironment as therapeutic targets of cancer stem cells. Life Sci. 2019;237:116952. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cross AH, McCarron R, McFarlin DE, Raine CS. Adoptively transferred acute and chronic relapsing autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the PL/J mouse and observations on altered pathology by intercurrent virus infection. Lab Invest. 1987;57:499–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hennings H, Devor D, Wenk ML, Slaga TJ, Former B, Colburn NH, Bowden GT, Elgjo K, Yuspa SH. Comparison of two-stage epidermal carcinogenesis initiated by 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene or N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine in newborn and adult SENCAR and BALB/c mice. Cancer Res. 1981;41:773–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Petersen P. [Psychic disturbances in women during oral contraception (author's transl)] MMW Munch Med Wochenschr. 1981;123:1109–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Overbosch D, Stuiver PC, van der Kaay HJ, de Geus A. The treatment of malaria. A Dutch consensus. Acta Leiden. 1984;52:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ehmsen S, Pedersen MH, Wang G, Terp MG, Arslanagic A, Hood BL, Conrads TP, Leth-Larsen R, Ditzel HJ. Increased Cholesterol Biosynthesis Is a Key Characteristic of Breast Cancer Stem Cells Influencing Patient Outcome. Cell Rep 2019; 27: 3927-3938. :e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.McGregor GH, Campbell AD, Fey SK, Tumanov S, Sumpton D, Blanco GR, Mackay G, Nixon C, Vazquez A, Sansom OJ, Kamphorst JJ. Targeting the Metabolic Response to Statin-Mediated Oxidative Stress Produces a Synergistic Antitumor Response. Cancer Res. 2020;80:175–188. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Janetschek G, Weitzel D, Stein W, Müntefering H, Alken P. Prenatal diagnosis of neuroblastoma by sonography. Urology. 1984;24:397–402. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(84)90224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Titlbach M. [Cell ultrastructure of the islands of Langerhans in Cyprinus carpio L] Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch. 1966;75:184–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pearce CJ, Conrad ME, Nolan PE, Fishbein DB, Dawson JE. Ehrlichiosis: a cause of bone marrow hypoplasia in humans. Am J Hematol. 1988;28:53–55. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830280111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Manusadzhian VG, Bolshakova TD, Menshikov VV, Dubobes GK. [Mass-spectrometry in combination with paper chromatography for determination of homovanillic acid] Lab Delo. 1973;10:595–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Koopman-Boyden PG. Community care of the elderly. N Z Med J. 1981;93:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Roberts TA, Jenkyn LR, Reeves AG. On the notion of doll's eyes. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:1242–1243. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04050230024011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kubo M, Umebayashi M, Kurata K, Mori H, Kai M, Onishi H, Katano M, Nakamura M, Morisaki T. Catumaxomab with Activated T-cells Efficiently Lyses Chemoresistant EpCAM-positive Triple-negative Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:4273–4279. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]