Abstract

A 59-year-old man presented to the urology department with increased urinary urgency, frequency, poor urinary flow and unintentional weight loss. He had a 25-year history of idiopathic urticaria episodes which had increased in frequency over the previous 2 months. On investigation, he was found to have a raised prostate-specific antigen level. He was investigated further with a multiparametric MRI, a local anaesthetic transperineal prostate biopsy, a CT scan of chest/abdomen/pelvis with contrast and a nuclear medicine bone scan. He was diagnosed with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate and commenced on a luteinising hormone-releasing hormone antagonist and referred to oncology for further treatment. Since starting treatment, he has experienced no further episodes of urticaria.

Keywords: prostate, dermatology, prostate cancer, urological cancer

Background

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy in men within the UK. It accounts for 26% of all new cancer diagnosed in men with 48 500 new cases every year. The incidence is projected to rise by 12% by 2035, largely due to an increasing elderly population.1

Commonly, prostate cancer presents as an incidental raised prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level. It may also present with lower urinary tract storage symptoms (LUTS), weight loss, haematuria or bone pain. This report describes a rare dermatological paraneoplastic syndrome presentation of prostate cancer with the patient presenting with urticaria.

Case presentation

A normally fit and well 59-year-old man with a performance status of 0 presented to the urology department with new-onset LUTS and 3 kg of unintentional weight loss over 2 months. He denied any haematuria. As a result of these symptoms, his General Practioner (GP) performed a PSA test and he was subsequently referred to urology.

His medical history was only significant for idiopathic urticaria for the last 25 years. Despite extensive previous investigation, no trigger was identified. During the preceding 2 months prior to presentation, the urticarial episodes had increased in frequency (figures 1–3) from one or two times per year to eight such episodes in the space of 2 months.

Figure 1.

Urticarial lesion on the right arm.

Figure 2.

Urticarial lesion on the left shoulder.

Figure 3.

Angioedema right cheek.

Investigations

Owing to the patient’s symptoms of urgency, frequency and poor flow, a PSA was requested with the result raised at 10.6 µg/L. An abnormal feeling prostate warranted further investigation with an urgent MRI scan. This demonstrated a 5.8 cm×6.1 cm×7.4 cm T4 prostate cancer with extracapsular extension, invading into the bladder base and seminal vesicles (figures 4–6). The MRI scan also identified extensive pelvic lymphadenopathy with a large 5.5 cm left external iliac node. A staging CT scan of chest/bbdomen/pelvis confirmed lymphadenopathy (figures 7–9) and a L3 bone metastasis with canal narrowing. He had no focal neurology and an urgent MRI of the spine showed no evidence of spinal cord compression. A bone scan revealed a solitary metastasis at L3 (figure 10). He had a local anaesthetic transperineal template biopsy of his prostate which demonstrated Gleason 5+5 prostate cancer.

Figure 4.

MRI T1 sequence demonstrating T4 prostate cancer.

Figure 5.

Axial MRI T2 sequence demonstrating T4 prostate cancer.

Figure 6.

Coronal MRI T2 sequence displaying T4 prostate cancer.

Figure 7.

Coronal CT with arrow pointing to a large pathological left iliac lymph node.

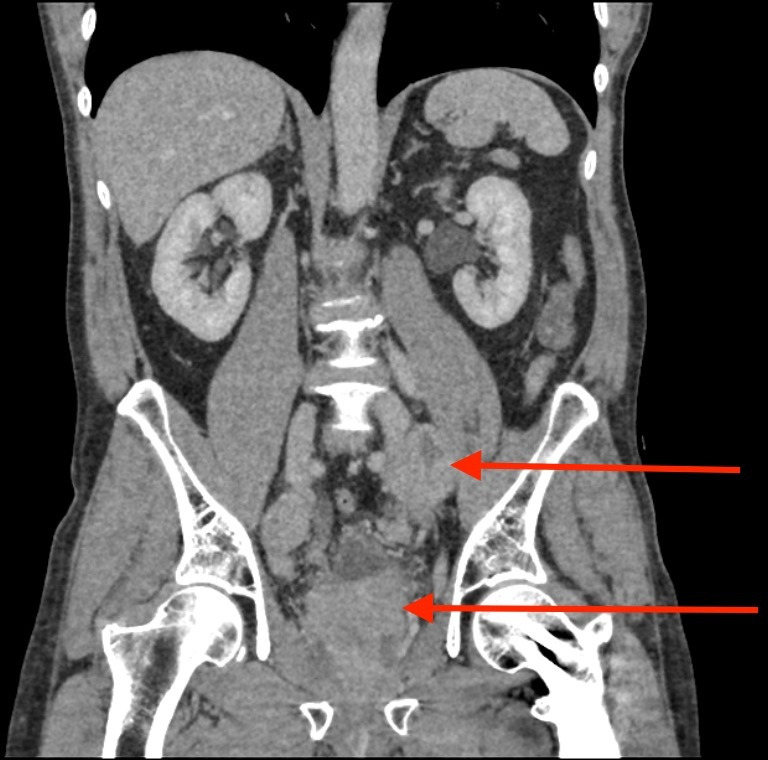

Figure 8.

A further coronal CT with the arrows pointing to a large pathological left iliac lymph node and a malignant prostate.

Figure 9.

Sagittal CT with red arrow pointing to a large pathological left iliac lymph node.

Figure 10.

Bone scan displaying a solitary metastasis in the L3 vertebra.

Treatment

Following his prostate biopsy, he was commenced on androgen deprivation therapy with a luteinising hormone-releasing hormone antagonist degarelix. His case was discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting and was referred to oncology for further chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Since initiation of treatment, the patient has not reported any further episodes of urticaria.

Outcome and follow-up

Referred to oncology for further treatment.

Discussion

Although exceedingly rare, prostate cancer may present with a paraneoplastic syndrome and it is the second most common urological malignancy to do so after renal cell carcinoma.2 These often present in the setting of advanced prostate cancer, as seen in our patient. In 70% of paraneoplastic syndromes, the first symptom is that of the syndrome itself.3 Therefore, early recognition and association are vital for prompt identification and treatment. Treatment typically focuses on the underlying malignancy, in addition to specialist management of other symptomatic manifestations.4 Paraneoplastic syndromes in prostate cancer can be broadly divided into six categories: endocrine, haematological, dermatological, neurological, inflammatory and others.

Recommendations for prostate cancer treatment are outlined in the European Association of Urologists (EAU) guidelines.5 A patient with prostate cancer with metastatic disease should immediately be offered androgen deprivation therapy as was our indexed patient. Surgery and/or local radiotherapy should be used in patients who show evidence of impending complications. In our case, radiotherapy was chosen as his CT showed evidence of canal narrowing. Radiotherapy is found to improve overall survival and decrease metastatic disease burden in those with low volume metastatic disease as categorised by the CHAARTED (chemohormonal therapy versus androgen ablation randomized trial for extensive disease in prostate cancer) criteria. Targeting the metastatic site is still seen to be experimental with very little data on the subject but currently, there is no evidence that it increases overall survival.5 The use of radical prostatectomy (RP) in those with metastatic disease remains controversial and is not recommended in the EAU guidelines. A meta-analysis by Wang et al suggested RP can benefit overall survival in patients with a low-grade tumour and good general health, but admitted more randomised controlled trials were needed.6 The Testing Radical prostatectomy in men with prostate cancer and oligometastases to the bone trial is investigating the success of performing RP on patients with prostate cancer and oligometastases to bones.7 We eagerly await the result of this trial.

Currently, the EAU recommends a multiparametric MRI, bone scan and cross-sectional abdominal pelvic imaging to stage prostate cancer. The combination is altered by stratifying patients into risk groups.5 Positron emmision tomography (PET) CT is a growing field in urology with data showing it provides superior accuracy in identifying lymph nodes and metastatic disease than the current recommendations.8 The decision of which type of PET CT scan to use is still under debate, although papers currently suggest Gallium-68 prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) PET has shown the greatest potential.8 9 For patients with a PSA lower than 1.5 ng/mL, PSMA PET has been shown to be better than standard PET (using C-choline as the tracer) at estimating tumour burden.9

A paraneoplastic syndrome is defined as ‘a group of rare disorders that are triggered by an abnormal immune system response to a cancerous tumour’.10 Up to 8% of patients with cancer have symptoms of a paraneoplastic syndrome; the most common associations being with small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, gynaecological tumours and haematological malignancies.4 The pathophysiology behind the syndrome is not fully understood with two proposed mechanisms. Either the tumour secretes functional peptides and hormones or it modulates the immune system resulting in systemic effects occurring remotely from the tumour.2 4

Urticaria is an extremely rare presentation of prostate cancer, while dermatomyositis is the most common dermatological paraneoplastic syndrome.3 Only one other case report exists to our knowledge where a patient’s first diagnosis of prostate cancer was made after they presented with an urticarial rash. Baroni et al described a patient presenting with a new-onset continuous urticarial rash. The patient had no metastatic spread and underwent a prostatectomy with no further episodes of urticaria following this.11 Marsaudon et al described the only other case with urticaria in association with prostatic malignancy. In the report, a patient’s recurrence of prostate cancer presented with chronic urticaria.12 This highlights that once a patient’s paraneoplastic urticaria disappears, if recurrence occurs, it should cause suspicion and the primary malignancy should be reinvestigated. Other paraneoplastic dermatological signs have been reported. Phan et al described a case of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematous.13 As in our case, the patient had significant metastatic disease. Cadmus et al reported a patient presenting with a 2-week history of psoriasis who was found to have underlying prostate cancer. Investigation, in this case, was prompted by the failure of initial psoriasis treatment.14 Momm et al reported a patient who presented with a 4-week history of erythroderma. Investigations found a high PSA and he was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the prostate.15

There are several reports in the literature of urticaria being linked with cancer, including breast and colon.16 17 Chronic urticaria is defined as urticaria experienced daily or episodic weals or angioedema that is present for more than 6 weeks.18 The association between urticaria and malignancy is still under discussion. In a study by Lindelöf et al of over 1000 reported cases, chronic urticaria was not statistically associated with malignancy.19 A cohort study by Chen found chronic urticaria to be associated with an increased risk of cancer. This was strongest for haematological malignancy.20 Both studies found the majority of cancers were diagnosed in the same year as urticaria onset making our case an exception to the rule.

In conclusion urticaria in association with prostate cancer is extremely rare. Clinicians should be aware that prostate cancer may manifest in this way or with other symptoms of paraneoplastic syndromes.

Learning points.

Urticaria can be associated with prostate cancer in rare cases.

When managing urticaria or other dermatological manifestations associated with paraneoplastic syndromes, failure of response to initial treatment or changes in character should warrant further investigation for underlying malignancy.

If a patient has a change in the pattern of their urticaria this should be viewed with suspicion and investigated if unusual pattern persists.

Paraneoplastic syndromes tend to be associated with advanced disease.

Paraneoplastic syndrome symptoms resolve following treatment of the underlying malignancy.

Footnotes

Contributors: JG wrote and compiled the report. OB was responsible for editing. YCP was responsible for planning. OK was responsible for the overall content.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Prostate cancer statistics [Internet] Cancer research UK, 2020. Available: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/prostate-cancer#heading-Zero [Accessed 11 April 2020].

- 2.Sacco E, Pinto F, Sasso F, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with urological malignancies. Urol Int 2009;83:1–11. 10.1159/000224860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong MK, Kong J, Namdarian B, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2010;7:681–92. 10.1038/nrurol.2010.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelosof LC, Gerber DE. Paraneoplastic syndromes: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:838–54. 10.4065/mcp.2010.0099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prostate Cancer [Internet] European association of urology, 2020. Available: https://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/ [Accessed 11 October 2020].

- 6.Wang Y, Qin Z, Wang Y, et al. The role of radical prostatectomy for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biosci Rep 2018;38. 10.1042/BSR20171379. [Epub ahead of print: 28 02 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sooriakumaran P. Testing radical prostatectomy in men with prostate cancer and oligometastases to the bone: a randomized controlled feasibility trial. BJU Int 2017;120:E8–20. 10.1111/bju.13925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofman MS, Lawrentschuk N, Francis RJ, et al. Prostate-Specific membrane antigen PET-CT in patients with high-risk prostate cancer before curative-intent surgery or radiotherapy (proPSMA): a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. The Lancet 2020;395:1208–16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30314-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fossati N, Scarcella S, Gandaglia G, et al. Underestimation of Positron Emission Tomography/Computerized Tomography in Assessing Tumor Burden in Prostate Cancer Nodal Recurrence: Head-to-Head Comparison of 68Ga-PSMA and 11C-Choline in a Large, Multi-Institutional Series of Extended Salvage Lymph Node Dissections. J Urol 2020;204:296–302. 10.1097/JU.0000000000000800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Internet] Paraneoplastic syndromes information page. Ninds.nih.gov, 2020. Available: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/all-disorders/paraneoplastic-syndromes-information-page [Accessed 13 April 2020].

- 11.Baroni A, Faccenda F, Russo T, et al. Figurate paraneoplastic urticaria and prostate cancer. Ann Dermatol 2012;24:366–7. 10.5021/ad.2012.24.3.366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marsaudon E, Ksiyer S, Louarn A, et al. Paraneoplastic urticarial vasculitis and recurrence of prostatic adenocarcinoma. J Case Rep Stud 2018;6:409. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phan YC, Shammout S, Cobley J, et al. Metastatic prostate cancer presenting as subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Australas J Dermatol 2020;61:e113–4. d 10.1111/ajd.13133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cadmus SD, Pearlstein MV, Pearlstein KA, et al. Paraneoplastic psoriasis in a patient with prostate cancer. JAAD Case Rep 2018;4:220–1. 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Momm F, Pflieger D, Lutterbach J. Paraneoplastic erythroderma in a prostate cancer patient. Strahlenther Onkol 2002;178:393–5. 10.1007/s00066-002-0967-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasi PM, Hieken TJ, Haddad TC. Unilateral arm urticaria presenting as a paraneoplastic manifestation of metachronous bilateral breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol 2016;9:33–8. 10.1159/000443661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santiago-Vázquez M, Barrera-Llaurador J, Carrasquillo OY, et al. Chronic spontaneous urticaria associated with colon adenocarcinoma: a paraneoplastic manifestation? A case report and review of literature. JAAD Case Rep 2019;5:101–3. 10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DermNet NZ [Internet] Chronic urticaria Dermnetnz.org, 2020. Available: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/chronic-urticaria/ [Accessed 11 April 2020].

- 19.Lindelöf B, Sigurgeirsson B, Wahlgren CF, et al. Chronic urticaria and cancer: an epidemiological study of 1155 patients. Br J Dermatol 1990;123:453–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb01449.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y-J. Cancer risk in patients with chronic urticaria. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:103 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]