Abstract

Background

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common primary ocular malignancy of adults. A small group of patients was found to express familial predisposition. Moreover, it may be preceded or followed by other malignancies elsewhere in the body. We aim to compare the incidence of UM and other associated cancers and study the factors that may influence each condition.

Patients and methods

We have collected the data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database of nine US cancer registries for UM patients between 1973 and 2015. We calculated the standardised incidence ratios for single primary UM, first primary and second primary UM, and compared the groups for multiple factors.

Results

A total of 4946 patients were included in the study; 3863 with single primary UM, 646 developed a second primary malignancy following UM, and 437 patients developed second primary UM following a previous primary malignancy. The risk of developing UM increased after leukaemia, melanoma of the skin and prostate. On the other side, the risk of developing melanoma of the skin, thyroid, renal and other eye and orbit malignancies has increased significantly after initial UM. This risk was more evident in the age group between 50 and 70 years old. Cancer-specific survival was significantly higher in UM associated with other malignancies group compared with single primary UM.

Conclusion

Our study showed a different behaviour of the UM when associated with other tumours that exceed the known spectrum of hereditary UM. Further studies are required to dissect the genetic background of this behaviour.

Keywords: uveal melanoma, second primary cancers, eye, survival, hereditary eye cancers

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Uveal melanoma is a malignancy with bad prognosis on the long-term and can be followed by other malignancies in a form of hereditary disease.

What does this study add?

Malignancies can precede uveal melanoma or follow it in higher rates than what were reported before. Prostate cancer and leukaemia showed a significant ratio to be followed by uveal melanoma.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Patients with uveal melanoma should be informed that they may develop further malignancies in the future. Fundus examination should be integrated in the follow-up plans of all patients with malignancies elsewhere in the body, especially prostate and leukaemia.

Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common primary ocular malignancy of the adult white population, with an incidence of 5.1 cases per million per year in the USA. It mainly arises from melanocytes originated from the neural crest and inhabited the choroid, ciliary body, and iris. It mainly affects the choroid unilaterally. Many factors were associated with increased incidence, including gender, race, exposure to ultraviolet rays/sunlight and in a few circumstances, it runs in families as a familial hereditary syndrome.1 The most frequent genetic mutations were BRCA1-associated protein-1 (BAP1), EIF1AX, GNA11 and GNAQ.2 Some genetic mutations linked to worse prognosis, including BAP1 itself.

Moreover, UM familial predisposition syndrome is marked by BAP1 germline mutations, which in turn is associated with other cancers, including cutaneous melanoma, malignant mesothelioma and renal cell carcinoma.3 4 Few studies discussed the incidence of other associated neoplasms with UM.5–8 These studies were mainly unidirectional or non-epidemiologic. Compared with each other, these studies showed different patterns of incidence and survival between UM in different milestones. We believe that studying the incidence from multiple directions can give an insight into understanding tumour development by correlating UM to other better-understood tumours.

Our aim is to compare the incidence and survival of UM as single, first, or second primary malignancy. Moreover, we aimed at comparing the association between UM and other cancers on its occurrence as the first or second primary malignancy.

Methods

Study design and data source

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Programme of the National Cancer Institute’s first nine cancer registries representing 10% of the US population between 1973 and 2015.

Study population

We included patients who were diagnosed between 1973 and 2015 with UM using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Site ‘C69.3-Choroid’, and ‘C69.4-Ciliary body’ and ICD Histology recode for broad groupings ‘8720–8799 (nevi and melanomas)’ to identify eligible patients. Only records with malignant behaviour and known age were included. We excluded records reported by autopsy and death certificate only. We also excluded patients who developed two distinct primary UM, or patients who developed a UM within less than 6 months before or after another primary malignancy to include only patients with clear temporal relations between malignancies.

Included patients were grouped into three groups: (1) Single primary melanoma (SiPUM): this group included patients who only developed a SiPUM and did not develop any other primary malignancy; (2) Second primary UM (SePUM): this group included patients who developed a primary UM following the development of another previous primary malignancy; (3) First Primary UM followed by another primary malignancy (FiPUM): this group included patients who developed a primary UM and then developed another primary malignancy.

In included patients, we examined the following characteristics: age at diagnosis of each malignancy, sex, race, site of each malignancy, histology of each malignancy, stage of UM, grade of UM, size of UM and the latency period between UM and the other primary malignancy.

Study outcomes

We calculated standardised incidence ratios (SIRs) for the development of SePUM following another a previous primary malignancy and the development of a second primary malignancy following a UM. SIRs were defined as the increased risk of developing the second malignancy after developing the first malignancy when compared with a demographically similar US population. We also calculated the overall survival of patients in the previously mentioned groups and assessed predictors of survival.

Statistical analysis

We used SEER*STAT V.8.3.5 to query the SEER database and calculate SIRs. All other statistical tests were conducted using IBM SPSS V.24. The χ2 test was used to compare patients’ and tumour characteristics between groups. Log-rank test was used for comparing groups in survival analysis, which was conducted using the Kaplan-Meyer test. A multivariable covariate-adjusted Cox model was conducted on the overall survival of the patients with adjustment for various confounders. All statistical tests were two sided, and a p<0.005 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

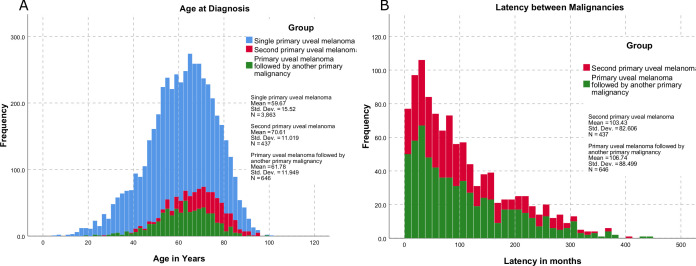

We included a total of 4946 patients, of which 78% were in the SiPUM group, 9% were in the SePUM group, and 13% were in the FiPUM group. The mean age of presentation of SiPUM was 59.67 years old, 2 years less than FiPUM and 11 years less than the SePUM (figure 1). The three groups showed similar distribution among the states and races, and most patients in all groups were white and married. Table 1 summarises patients’ characteristics in the three groups.

Figure 1.

The distribution of the age in years at um diagnosis (A) and latency between UM and the other malignancy in months (B) in the three groups. UM, uveal melanoma.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Study group | P value | ||||||

| Single primary uveal melanoma (n=3863) | Second primary uveal melanoma (n=437) | Primary uveal melanoma followed by another primary malignancy (n=646) | |||||

| N | Col. N % | N | Col. N % | N | Col. N % | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 2008 | 52.0 | 240 | 54.9 | 385 | 59.6 | <0.001 |

| Female | 1855 | 48.0 | 197 | 45.1 | 261 | 40.4 | |

| Registry | |||||||

| San Francisco-Oakland SMSA—1973+, California | 547 | 14.2 | 91 | 20.8 | 96 | 14.9 | 0.136 |

| Connecticut—1973+ | 549 | 14.2 | 74 | 16.9 | 70 | 10.8 | |

| Detroit (Metropolitan)—1973+, Michigan | 479 | 12.4 | 49 | 11.2 | 103 | 15.9 | |

| Hawaii—1973+ | 43 | 1.1 | 4 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.9 | |

| Iowa—1973+ | 792 | 20.5 | 71 | 16.2 | 135 | 20.9 | |

| New Mexico—1973+ | 159 | 4.1 | 15 | 3.4 | 26 | 4.0 | |

| Seattle (Puget Sound) - 1974+, Washington | 691 | 17.9 | 77 | 17.6 | 127 | 19.7 | |

| Utah—1973+ | 323 | 8.4 | 27 | 6.2 | 49 | 7.6 | |

| Atlanta (Metropolitan)—1975+, Georgia | 280 | 7.2 | 29 | 6.6 | 34 | 5.3 | |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 3766 | 98.5 | 431 | 98.9 | 640 | 99.1 | 0.164 |

| Black | 25 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.8 | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 27 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 2392 | 66.5 | 287 | 70.3 | 456 | 75.4% | 0.001 |

| Single | 446 | 12.4 | 35 | 8.6 | 50 | 8.3% | |

| Separated | 30 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.7 | 8 | 1.3% | |

| Divorced | 239 | 6.6% | 19 | 4.7 | 36 | 6.0% | |

| Widowed | 490 | 13.6 | 64 | 15.7 | 55 | 9.1% | |

| Unmarried or domestic partner | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0% | |

The choroid was the most common site for UM in all the groups, and most UM cases were diagnosed when still localised, with SePUM having the highest rate of distant metastases at diagnosis of disease (2.8%). Among patients with reported pathological subtype, Mixed epithelioid—spindle cell melanoma was the most common pathological subtype, followed by Spindle cell melanoma, type B. Epithelioid cell melanoma was more common in the SiPUM (4.9%) than SePUM (3.2%) and FiPUM (2.5%). Table 2 summarises tumour characteristics in the three groups.

Table 2.

Tumourcharacteristics—treatment

| Study group | P value | ||||||

| Single primary uveal mel. (n=3863) | Second primary uveal mel. (n=437) | Primary uveal mel. followed by another primary malignancy (n=646) | |||||

| N | Col. N % | N | Col. N % | N | Col. N % | ||

| Site | |||||||

| C69.3-Choroid | 3235 | 83.7 | 361 | 82.6 | 516 | 79.9 | 0.016 |

| C69.4-Ciliary body | 628 | 16.3 | 76 | 17.4 | 130 | 20.1 | |

| Histology | |||||||

| 8720/3: Malignant, NOS | 2511 | 65.0 | 309 | 70.7 | 397 | 61.5 | 0.288 |

| 8726/3: Malignant in magnocellular nevus | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 8730/3: Amelanotic | 30 | 0.8 | 5 | 1.1 | 4 | 0.6 | |

| 8742/3: Lentigo maligna | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 8743/3: Superficial spreading | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| 8770/3: Mixed epithelioid and spindle cell | 454 | 11.8 | 53 | 12.1 | 85 | 13.2 | |

| 8771/3: Epithelioid cell | 190 | 4.9 | 14 | 3.2 | 16 | 2.5 | |

| 8772/3: Spindle cell, NOS | 253 | 6.5 | 25 | 5.7 | 55 | 8.5 | |

| 8773/3: Spindle cell, type A | 35 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 1.2 | |

| 8774/3: Spindle cell, type B | 388 | 10.0 | 31 | 7.1 | 80 | 12.4 | |

| Stage | |||||||

| Localised | 3176 | 91.8 | 348 | 90.2 | 551 | 94.8 | 0.023 |

| Regional | 222 | 6.4 | 27 | 7.0 | 28 | 4.8 | |

| Distant | 63 | 1.8 | 11 | 2.8 | 2 | 0.3 | |

| Size | |||||||

| 5 mm or less | 109 | 7.2 | 11 | 6.5 | 34 | 11.5 | 0.097 |

| 6–10 mm | 432 | 28.6 | 49 | 29.0 | 89 | 30.1 | |

| 11–15 mm | 547 | 36.3 | 56 | 33.1 | 95 | 32.1 | |

| More than 15 mm | 420 | 27.9 | 53 | 31.4 | 78 | 26.4 | |

| Grade | |||||||

| Well differentiated; Grade I | 37 | 35.9 | 5 | 38.5 | 3 | 37.5 | 0.653 |

| Moderately differentiated; Grade II | 47 | 45.6 | 5 | 38.5 | 5 | 62.5 | |

| Poorly differentiated; Grade III | 18 | 17.5 | 2 | 15.4 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Undifferentiated; anaplastic; grade IV | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 7.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Confirmation | |||||||

| Positive histology | 2420 | 63.2 | 248 | 57.4 | 456 | 71.4 | 0.003 |

| Positive exfoliative cytology, no positive histology | 122 | 3.2 | 22 | 5.1 | 10 | 1.6 | |

| Positive microscopic confirm, method not specified | 9 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.7 | 4 | 0.6 | |

| Positive laboratory test/marker study | 3 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.5 | |

| Direct visualisation without microscopic confirmation | 443 | 11.6 | 70 | 16.2 | 64 | 10.0 | |

| Radiography without microscopic confirm | 625 | 16.3 | 73 | 16.9 | 70 | 11.0 | |

| Clinical diagnosis only | 205 | 5.4 | 14 | 3.2 | 32 | 5.0 | |

Among our FiPUM cohort, the most common sites for following primary cancers were prostate (17%), lung and bronchus (12.7%) and breast (10.1%), while in the SePUM group, the most common sites for the previous primary cancers were prostate (26%), breast (21.5%), and colon and rectum (12.1%) (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparing relationships between first and second primary uveal melanomas (UM) and the other malignancies

| Characteristics | First primary UM | Second primary UM |

| Age at diagnosis of the other malignancy (mean age in years, SD) | 70.6 (11) | 61.8 (11.9) |

| Independent-samples Mann-Whitney U test p<0.0001 |

||

| Latency period between UM and the other malignancy (mean latency in months, SD) | 106.7 (88.5) | 103.4 (82.6) |

| Independent-samples Mann-Whitney U test p=0.95 |

||

| Site of the other malignancy | ||

| Breast* | 65 (24.9) | 94 (47.7) |

| Prostate* | 110 (28.6) | 116 (48.3) |

| Colon and rectum | 61 (9.4) | 53 (12.1) |

| Lung and bronchus | 82 (12.7) | 12 (2.7) |

| Urinary bladder | 36 (5.6) | 26 (5.9) |

| Melanoma of the skin | 61 (9.4) | 38 (8.7) |

| Corpus uteri* | 17 (6.5) | 16 (8.1) |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 19 (2.9) | 11 (2.5) |

| Oral cavity and pharynx | 7 (1.1) | 10 (2.3) |

| Thyroid | 11 (1.7) | 12 (4.6) |

| Ovary* | 10 (3.8) | 9 (2.1) |

| Leukaemia | 18 (2.8) | 9 (2.1) |

| Kidney and renal pelvis | 27 (4.2) | 7 (1.6) |

| Eye and orbit | 9 (1.4) | 2 (0.5) |

| Other sites | 113 (17.5) | 22 (5) |

*Percentages for these cancer were calculated as gender based (the denominator was males/females instead of the overall population).

The risk of second malignancy after FiPUM

A total of 646 patients developed a second primary malignancy following UM, with an overall SIR of 1.09 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.18). The highest increase in the risk of developing a second primary malignancy following UM was withing the first 5 years of UM diagnosis (SIR 1.2, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.35), with this risk being specifically apparent among male patients and white patients (SIR 1.19, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.39 and SIR 1.21, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.36, respectively). Besides, patients who were younger than 65 years old at the diagnosis of UM also showed an increase in cancer risk within 5 years of diagnosis (SIR 1.39, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.68) and 5–10 years of diagnosis (SIR 1.29, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.56). Interestingly, the risk of developing a primary malignancy increased within 5 years of choroid UM (SIR 1.2, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.37), but within 5–10 years of ciliary body UM (SIR 1.42, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.93). Mixed epithelioid and spindle cell UM showed the highest increase in primary cancer risk within 5 years (SIR 1.66, 95% CI 1.20 to 2.24), whereas the increase in risk following spindle cell UM was highest within 5–10 years (SIR 1.15, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.79). When the site of second cancer following UM was studied, patients with UM were shown to have an increased risk of developing melanoma of the skin, thyroid cancer and kidney cancers (table 4). Further subgroup analysis was provided in online supplemental tables 1–4.

Table 4.

Standardised incidence ratios (SIR) for developing a second malignancy after first primary uveal melanoma according to latency; SIR (95% CIs)

| Characteristics | <5 years | 5–10 years | >10 years | Total* | ||||

| Obs. | SIR (95% CI) | Obs. | SIR (95% CI) | Obs. | SIR (95% CI) | Obs. | SIR (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 258 | 1.20† (1.06 to 1.35) | 181 | 1.09 (0.94 to 1.27) | 287 | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.14) | 726 | 1.09† (1.02 to 1.18) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 153 | 1.19† (1.01 to 1.39) | 116 | 1.15 (0.95 to 1.38) | 169 | 0.97 (0.83 to 1.13) | 438 | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.19) |

| Female | 105 | 1.21 (0.99 to 1.47) | 65 | 1.00 (0.77 to 1.28) | 118 | 1.08 (0.90 to 1.30) | 288 | 1.11 (0.98 to 1.24) |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 256 | 1.21† (1.06 to 1.36) | 180 | 1.11 (0.95 to 1.28) | 283 | 1.02 (0.90 to 1.14) | 719 | 1.10† (1.02 to 1.18) |

| Black | 1 | 0.78 (0.02 to 4.32) | 1 | 1.08 (0.03 to 6.04) | 4 | 1.55 (0.42 to 3.97) | 6 | 1.25 (0.46 to 2.73) |

| Other races | 1 | 1.23 (0.03 to 6.87) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.57 (0.01 to 3.19) |

| Age at diagnosis of uveal melanoma | ||||||||

| <50 years | 15 | 1.36 (0.76 to 2.24) | 20 | 1.41 (0.86 to 2.17) | 69 | 0.97 (0.75 to 1.23) | 104 | 1.08 (0.88 to 1.31) |

| 50–70 years | 133 | 1.24† (1.04 to 1.47) | 113 | 1.15 (0.94 to 1.38) | 182 | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.17) | 428 | 1.11† (1.01 to 1.22) |

| >70 years | 110 | 1.13 (0.93 to 1.37) | 48 | 0.91 (0.67 to 1.21) | 36 | 1.10 (0.77 to 1.52) | 194 | 1.06 (0.92 to 1.22) |

| Primary site of uveal melanoma‡ | ||||||||

| Choroid | 217 | 1.20† (1.04 to 1.37) | 140 | 1.03 (0.9 to 1.2) | 220 | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.15) | 577 | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.17) |

| Ciliary body | 41 | 1.21 (0.87 to 1.64) | 41 | 1.42† (1.02 to 1.93) | 67 | 1.03 (0.80 to 1.31) | 149 | 1.17 (0.99 to 1.37) |

| Site of the next malignsancy§ | ||||||||

| Breast | 21 | 0.83 (0.51 to 1.27) | 17 | 0.91 (0.53 to 1.46) | 29 | 0.97 (0.65 to 1.39) | 67 | 0.91 (0.70 to 1.15) |

| Prostate | 45 | 1.20 (0.87 to 1.60) | 28 | 0.93 (0.62 to 1.35) | 47 | 0.91 (0.67 to 1.21) | 120 | 1.01 (0.83 to 1.20) |

| Colon and rectum | 26 | 1.02 (0.66 to 1.49) | 15 | 0.77 (0.43 to 1.27) | 28 | 0.86 (0.57 to 1.25) | 69 | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.13) |

| Lung and bronchus | 23 | 0.71 (0.45 to 1.06) | 31 | 1.25 (0.85 to 1.77) | 44 | 1.04 (0.75 to 1.39) | 98 | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.20) |

| Urinary bladder | 11 | 0.90 (0.45 to 1.61) | 11 | 1.13 (0.57 to 2.03) | 19 | 1.05 (0.63 to 1.64) | 41 | 1.03 (0.74 to 1.39) |

| Melanoma of the skin | 30 | 3.76† (2.54 to 5.37) | 12 | 1.92 (0.99 to 3.36) | 23 | 1.96† (1.24 to 2.94) | 65 | 2.51† (1.93 to 3.19) |

| Corpus uteri | 3 | 0.52 (0.11 to 1.53) | 6 | 1.48 (0.54 to 3.23) | 10 | 1.66 (0.80 to 3.05) | 19 | 1.20 (0.72 to 1.88) |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 12 | 1.42 (0.73 to 2.48) | 4 | 0.60 (0.17 to 1.55) | 9 | 0.74 (0.34 to 1.40) | 25 | 0.92 (0.60 to 1.35) |

| Oral cavity and pharynx | 6 | 1.08 (0.40 to 2.36) | 4 | 0.99 (0.27 to 2.53) | 3 | 0.47 (0.10 to 1.37) | 13 | 0.81 (0.43 to 1.39) |

| Thyroid | 7 | 3.16† (1.27 to 6.51) | 1 | 0.62 (0.02 to 3.47) | 3 | 1.16 (0.24 to 3.40) | 11 | 1.72 (0.86 to 3.07) |

| Ovary | 3 | 1.03 (0.21 to 3.00) | 1 | 0.47 (0.01 to 2.63) | 6 | 1.80 (0.66 to 3.91) | 10 | 1.19 (0.57 to 2.19) |

| Leukaemia | 5 | 0.82 (0.27 to 1.90) | 7 | 1.46 (0.59 to 3.01) | 11 | 1.25 (0.53 to 2.24) | 23 | 1.17 (0.74 to 1.75) |

| Kidney and renal pelvis | 15 | 2.62† (1.47 to 4.32) | 5 | 1.13 (0.37 to 2.63) | 11 | 1.41 (0.70 to 2.51) | 31 | 1.72† (1.17 to 2.45) |

| Eye and orbit | 3 | 8.01† (1.65 to 23.41) | 2 | 7.25 (0.88 to 26.20) | 5 | 10.84† (3.52 to 25.30) | 10 | 9.00† (4.31 to 16.55) |

Bold values are statistically significant (p<.001)

*Single patient may have multiple tumours. Further details are available in (online supplemental table 9).

†Significant with p<0.05.

‡Using primary site variable.

§Using ICD-O-3 site recode.

ICD, International Classification of Diseases; Obs., observed.

esmoopen-2020-000990supp001.pdf (228.3KB, pdf)

The risk of SePUM after other primary malignancies

A total of 437 patients developed SePUM following a previous primary malignancy. Overall, the risk of UM among patients with another primary malignancy increased only within 5–10 years of the first malignancy diagnosis with an SIR of 1.2 (95% CI 1.01 to 0.43), and was explicitly high among whites (SIR 1.2, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.43) and patients who were diagnosed with the first malignancy at an age younger than 65 years (SIR=1.37, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.73). Interestingly, the overall risk of developing ciliary body UM following a previous malignancy showed a significant increase with an SIR of 1.37 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.71). When the site of the first cancer was studied, patients with prostate cancer, melanoma of the skin and leukaemia were shown to increase the risk of developing SePUM, while exposure for radiotherapy did not change UM risk (table 5). Further subgroup analysis was provided in online supplemental tables 5–8.

Table 5.

Standardised incidence ratios (SIR) for developing a primary uveal melanoma following another primary malignancy according to the latency; SIR (95% CIs)

| Characteristics | <5 years | 5–10 years | >10 years | Total* | ||||

| Obs. | SIR (95% CI) | Obs. | SIR (95% CI) | Obs. | SIR (95% CI) | Obs. | SIR (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 166 | 1.08 (0.92 to 1.25) | 132 | 1.20† (1.01 to 1.43) | 143 | 0.99 (0.84 to 1.17) | 441 | 1.08 (0.98 to 1.19) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 96 | 1.04 (0.84 to 1.27) | 77 | 1.21 (0.95 to 1.51) | 69 | 0.99 (0.77 to 1.25) | 242 | 1.07 (0.94 to 1.21) |

| Female | 70 | 1.13 (0.88 to 1.43) | 55 | 1.20 (0.91 to 1.57) | 74 | 0.99 (0.78 to 1.25) | 199 | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.26) |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 164 | 1.08 (0.92 to 1.26) | 130 | 1.20† (1.01 to 1.43) | 141 | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.17) | 435 | 1.08 (0.98 to 1.19) |

| Black | 1 | 1.21 (0.03 to 6.75) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.59 (0.04 to 8.87) | 2 | 1.00 (0.12 to 3.62) |

| Other races | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4.36 (0.53 to 15.76) | 1 | 1.73 (0.04 to 9.61) | 3 | 1.75 (0.361 to 5.12) |

| Age at diagnosis of the first cancer | ||||||||

| <50 years | 7 | 0.80 (0.32 to 1.65) | 18 | 1.78† (1.06 to 2.82) | 40 | 1.06 (0.76 to 1.45) | 65 | 1.15 (0.89 to 1.47) |

| 50–70 years | 79 | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.26) | 74 | 1.15 (0.91 to 1.45) | 89 | 1 (0.80 to 1.23) | 242 | 1.05 (0.92 to 1.19) |

| >70 years | 80 | 1.18 (0.94 to 1.47) | 40 | 1.13 (0.81 to 1.54) | 14 | 0.78 (0.43 to 1.31) | 134 | 1.11 (0.93 to 1.31) |

| Primary site of uveal melanoma‡ | ||||||||

| Choroid | 137 | 1.04 (0.87 to 1.23) | 111 | 1.17 (0.96 to 1.409) | 117 | 0.93 (0.77 to 1.11) | 365 | 1.04 (0.93 to 1.15) |

| Ciliary body | 29 | 1.28 (0.86 to 1.84) | 21 | 1.43 (0.88 to 2.18) | 26 | 1.43 (0.93 to 2.09) | 76 | 1.37† (1.08 to 1.71) |

| Site of the first malignancy§ | ||||||||

| Breast | 32 | 1.26 (0.86 to 1.776) | 24 | 1.16 (0.75 to 1.73) | 41 | 1.24 (0.89 to 1.69) | 97 | 1.23 (0.995 to 1.5) |

| Prostate | 49 | 1.15 (0.85 to 1.51) | 45 | 1.40† (1.02 to 1.88) | 22 | 0.82 (0.52 to 1.25) | 116 | 1.14 (0.94 to 1.37) |

| Colon and rectum | 18 | 0.96 (0.57 to 1.52) | 15 | 1.19 (0.67 to 1.96) | 21 | 1.29 (0.80 to 1.98) | 54 | 1.14 (0.85 to 1.48) |

| Lung and bronchus | 5 | 0.61 (0.2 to 1.42) | 3 | 0.89 (0.18 to 2.61) | 4 | 1.29 (0.35 to 3.3) | 12 | 0.82 (0.42 to 1.43) |

| Urinary bladder | 12 | 1.18 (0.61 to 2.07) | 6 | 0.84 (0.31 to 1.83) | 9 | 1.00 (0.46 to 1.89) | 27 | 1.03 (0.68 to 1.49) |

| Melanoma of the skin | 11 | 1.56 (0.78 to 2.8) | 10 | 1.75 (0.84 to 3.23) | 17 | 1.59 (0.92 to 2.54) | 38 | 1.62† (1.15 to 2.22) |

| Corpus uteri | 8 | 1.3 (0.56 to 2.55) | 2 | 0.38 (0.05 to 1.37) | 6 | 0.58 (0.21 to 1.27) | 16 | 0.74 (0.42 to 1.2) |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 5 | 0.85 (0.28 to 1.98) | 3 | 0.78 (0.16 to 2.27) | 3 | 0.68 (0.14 to 1.99) | 11 | 0.78 (0.39 to 1.39) |

| Oral cavity and pharynx | 5 | 1.25 (0.41 to 2.29) | 3 | 1.12 (0.23 to 3.27) | 2 | 0.55 (0.07 to 2.00) | 10 | 0.97 (0.47 to 1.79) |

| Thyroid | 1 | 2.23 (0.72 to 5.19) | 0 | 2.57 (0.84 to 6.00) | 1 | 0.44 (0.05 to 1.59) | 2 | 1.38 (0.71 to 2.40) |

| Ovary | 5 | 2.92 (0.95 to 6.83) | 1 | 1.00 (0.03 to 5.56) | 3 | 1.43 (0.30 to 4.24) | 9 | 1.88 (0.86 to 3.58) |

| Leukaemia | 2 | 0.57 (0.07 to 2.05) | 6 | 2.92† (1.07 to 6.35) | 1 | 0.5 (0.01 to 2.78) | 9 | 1.19 (0.54 to 2.25) |

| Kidney and renal pelvis | 3 | 0.77 (0.16 to 2.25) | 3 | 1.14 (0.23 to 3.32) | 1 | 0.32 (0.01 to 1.81) | 7 | 0.73 (0.29 to 1.5) |

| Eye and orbit | 1 | 9.96 (0.25 to 55.43) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9.63 (0.24 to 53.66) | 2 | 7.36 (0.89 to 26.60) |

*Single patient may have multiple tumours. Further details are available in (online supplemental table 10).

†Significant with p<0.05.

‡Using primary site variable.

§Using ICD-O-3 site recode.

ICD, International Classification of Diseases; Obs., observed.

Survival of UM

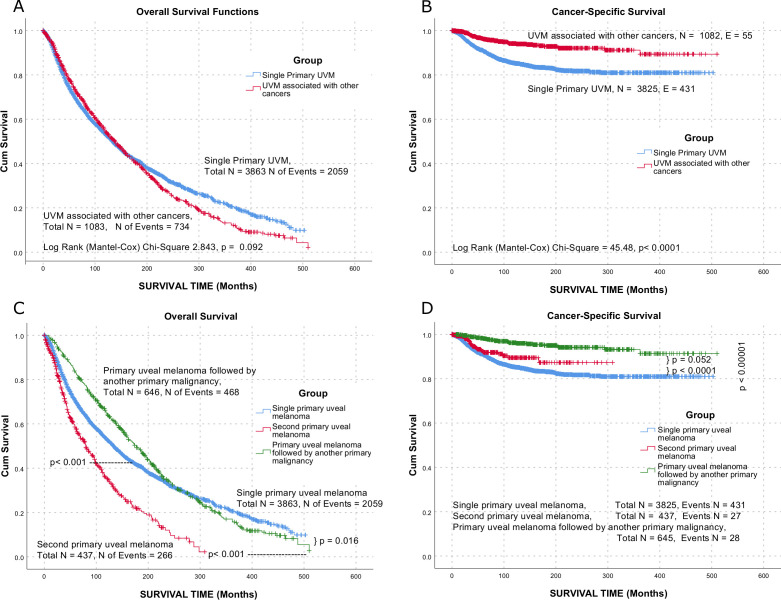

Patients in the SiPUM group showed an overall median survival of 195.7 months (95% CI 189.59 to 201.8) following the diagnosis of UM, while patients in the SePUM group showed a median survival of 139 months (95% CI 132.04 to 145.9). On the other hand, the median overall survival in the FiPUM group was 177 months (95% CI 160.9 to 193.1) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overall (A, C) and UM cancer-specific (B, D) survival. UM, uveal melanoma; UVM, uveal tract melanoma.

After adjusting for sex, race, age at diagnosis of UM, site of UM, stage at diagnosis of UM, size at diagnosis of UM, and undergoing cancer-directed surgery for UM, multivariate Cox models showed a better overall survival for females, but worse outcomes for black patients, ciliary body UM, larger or more advanced UM (table 6). Further Analysis was provided in online supplemental figure 1). The other causes of cancers in the study groups were uploaded to the online repository (10.5281/zenodo.4058248).

Table 6.

Multivariable covariate-adjusted Cox models for overall survival of patients with adjustment for the following factors: sex, race, age at diagnosis of uveal melanoma (UM), site of UM, stage of UM, size of UM and surgery as a treatment option for UM

| Patient characteristics | Single primary UM | First primary UM | Second primary UM | |||

| All-cause HR* (95% CI) † |

All-cause P value‡ |

All-cause HR* (95% CI) † |

All-cause P value‡ |

All-cause HR* (95% CI)† |

All-cause P value‡ |

|

| Sex (vs no male) | ||||||

| Female | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.93) | 0.001 | 0.83 (0.75 to 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.66 (0.45 to 0.86) | 0.042 |

| Race (vs white) | ||||||

| Black | 1.57 (0.79 to 2.96) | 0.211 | 1.55 (0.83 to 2.91) | 0.17 | 1.74 (0.23 to 13.18) | 0.59 |

| Asian or pacific islander | 0.74 (0.41 to 1.34) | 0.317 | 0.74 (0.41 to 1.35) | 0.325 | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0.5 (0.16 to 1.57) | 0.234 | 0.62 (0.23 to 1.68) | 0.351 | 1.75 (0.21 to 14.24) | 0.603 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 1.05 (1.05 to 1.05) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.05 to 1.05) | <001 | 1.05 (1.02 to 1.07) | <0.001 |

| Site (vs choroid) | ||||||

| Ciliary body | 1.21 (1.04 to 1.4) | 0.012 | 1.23 (1.07 to 1.42) | 0.004 | 1.33 (0.75 to 2.35) | 0.327 |

| Stage (vs localised) | ||||||

| Regional | 1.39 (1.17 to 1.65) | <0.001 | 1.36 (1.16 to 1.61) | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.54 to 2.11) | 0.86 |

| Distant | 14.22 (9.59 to 21.09) | <0.001 | 14.41 (9.79 to 21.22) | <0.001 | 37.91 (4.05 to 354.74) | 0.001 |

| Size (vs 5 mm or less) | ||||||

| 6–10 mm | 0.86 (0.68 to 1.10) | 0.237 | 0.87 (0.69 to 1.1) | 0.245 | 1.02 (0.45 to 2.35) | 0.958 |

| 11–15 mm | 1.53 (1.22 to 1.94) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.19 to 1.87) | <0.001 | 1.18 (0.51 to 2.68) | 0.703 |

| More than 15 mm | 1.83 (1.45 to 2.31) | <0.001 | 1.79 (1.43 to 2.23) | <0.001 | 1.49 (0.65 to 3.43) | 0.344 |

| Surgery (vs no) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.94 (1.74 to 2.16) | <0.001 | 1.88 (1.7 to 2.09) | <0.001 | 1.39 (0.95 to 2.03) | 0.088 |

| Latitude | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) | 0.12 | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) | 0.101 | 0.995 (0.95 to 1.05) | 0.855 |

| Sequence of UM (vs single UM) | ||||||

| Second UM | 1 (0.82 to 1.21) | 1 | ||||

*This number represents the HR for all-cause and cancer-specific death for the above covariables. All statistical tests were two sided.

†This represents CI.

‡Two-sided p value was calculated from multivariable covariate-adjusted Cox models.

Patients in the exclusion period

In the exclusion period (first 6 months after diagnosis), 25 patients (SIR=1.0) were diagnosed in the SePUM group, while 43 patients (SIR=1.47, p<0.05) were diagnosed in the FiPUM group. Those patients were excluded from further analysis in the paper.

Discussion

Our study of 4946 melanoma patients in the SEER database included 3863 Single primary, 646 Primary UM followed by another primary malignancy and 437 s primary UM. It showed a 9% increased risk of developing a second malignancy after UM, which reaches 20% in the first 5 years after the diagnosis of UM. This was led by an increased incidence of cutaneous melanoma, thyroid cancers, renal tumours and other ocular and orbital tumours. On the other side, UM showed 8% increase after other tumours. This has increased to 20% in 5–10 years after the diagnosis of the first tumour.

UM is the most common primary ocular malignant neoplasm. It mainly affects the choroid in the population over 40 years with a median age of around 60 years and later mode. Males and white populations show increasing incidence with increasing latitudes. It is hypothesised that ultraviolet rays increase the risk of developing UM. However, this hypothesis was not consistent in all epidemiological publications. Recently, it was assumed that multiple sunlight exposure and mutational profiles can act independently to represent multiple subtypes of the disease; genetic predisposition profiles that are affected by ultraviolet rays and others that are not affected by such exposure.9 10

Germline pathogenic variants in several cancer genes have been reported in patients with UM.11 12 BAP1 is the only gene with a definitive association with a predisposition to UM. It shows a frequency of about 22% in familial UM but as low as 1%–2% in sporadic UM.13–15 The evidence for the association of other genes ranges from limited to moderate.16

BAP1 has marked its own tumour predisposition syndrome and is associated with developing UM, cutaneous melanoma, mesothelioma, renal cell carcinoma and other malignancies. Other cancer genes reported in patients with UM include BRCA2, BRCA1, CHEK2, PALB2, SMARCE1, MBD4, MSH6 and MLH1.12 17 CHEK2 mutations predispose to papillary thyroid, prostate and breast cancers.18 PALB2 mutations show an association with breast, ovarian and pancreatic cancers.19 Mutations of SMARCE1 results in spinal meningiomas and its high expression associate with poor prognosis of breast cancer.20 21 MLH1 and MSH6 are associated with colorectal and endometrial cancers, ovarian and other gastrointestinal system tumours as part of Lynch syndrome.22 23 A more plausible explanation is that a genetic risk factor yet not identified predisposes to both.

A previous analysis of the SEER Database revealed that UM has an 11% excess risk to develop skin melanomas and renal tumours independently from radiation.5 A multicentre study that included registries from Canada, Iceland, UK, Europe, Singapore and Australia showed that UM followed other cancers with 24% increased risk and variable SIR per tumours. SIR was highest for cutaneous melanoma (2.38), followed by multiple myeloma (2.00), hepatic (3.89), renal (1.70), pancreatic (1.58), prostate (1.31) and stomach (1.33) cancers.24

A Swedish UM cohort showed 25% more odds of developing UM after other cancers.7 None of the cancers showed a statistically significant SIR. However, it was high in Endocrine glands tumours (1.88), cutaneous melanoma (1.74), cutaneous non-melanoma (1.62), prostate (1.52), lip-oesophagus(1.52), then in lymphoma-leukaemia (1.46), urinary system (1.32) and female genital organs (1.24) groups. On the contrary, it showed SIR of 1.13 of developing other cancers after primary UM. The SIR was high for Thyroid/endocrine glands cancers (1.76), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (1.77), cutaneous melanoma (1.75), nervous system (1.49), uterus (1.41), followed by leukaemia (1.31).

Multiple mechanisms may explain the incidence of multiple primary tumours, including the persistence of multiple pathogenic mechanisms.25 Melanocytes share the same embryologic origin with the nervous system arising from the neural crest, and a common genetic may lead to such multiple tumours. Moreover, an escape from the immune system after primary lymphomas and leukaemias can lead to numerous tumours in different organs. Furthermore, the existence of autoimmune diseases, as mentioned previously, can justify the coincidence of UM with thyroid diseases as described before. The effect of radiation therapy (especially brachytherapy) of UM on the development of second primary tumours should be limited to orbital tumours and that of treatment of remote body sites on the development of UM. Besides, a single or multiple genetic mutations, from the previously mentioned, maybe involved occurring together or as a part of a genetic instability condition that happens in a Snowball effect.

Tables 4 and 5 show that the burden of participating factors, either genetic or environmental, has significantly influenced the early development of second malignancies of melanoma o the skin, thyroid and renal tumours within 5 years after UM. On the contrary, the development of UM after prostate and leukaemias necessitated longer periods. The incidence of skin melanoma was consistent over time before and after the UM. This observation may indicate shared pathogenic mechanisms or miscoding of metastasis.

Interestingly, the overall survival of primary UM followed by other cancers exceeded other UM in the first 20 years following diagnosis then followed a similar survival of SiPUM. However, both kept a better pattern than the SePUM. From cancer-specific survival perspectives, the SePUM showed better survival, followed by the FiPUM, then SiPUM (figure 2). This discrepancy can be explained by better care of patients presented with previous tumours, the false registration of cause of death as other cancer or other diseases, or actual death flail patients by other cancer. The worse survival for large tumours and those requiring enucleation (table 6) are consistent among the three groups and the previous publications.1 In our study, women showed better survival, an observation that is inconsistent with other publications.26 27 Others showed consistent results.28

The high SIR of diagnosing patients in FiPUM group can be an indicator of the physicians’ concern about the metastasis of UM to other sites and their meticulous examination of patients thereafter. While examining the fundus of is not indicated in most of the guidelines of the malignancies elsewhere in the body resulting in failure to find early UM.

As a retrospective registry-based study, this study carries limitations of limited clinical data about the patients and biological data about the tumours. Moreover, although the increasing efforts put on quality control of the SEER’s incomplete data is still an issue for improvement.29 Moreover, the database does not provide information about detailed histology, tumour recurrence, or the aim of therapy (palliative vs curative), and we have to assume the aim according to the stage. Furthermore, data were limited due to access restrictions to records inside the SEER registry, no access to outside regions. It was hard to estimate the effect of treatment on the development of second primary cancers due to limited reporting and follow-up in the SEER registry. Besides, due to that fact that surgery has a limited value in the initial management of UM and limitations provided in the SEER data about the treatment details, the comparison between histological subtypes should be also read with caution.

This publication is paving the road for further studying of UM as a part of multiple systemic diseases and the need for the follow-up of the patients for more prolonged periods. Further modelling of the factors and relations found in this study besides molecular and genetic mechanisms can give a better understanding of the mechanisms involved in tumour development. Particular attention should be given to a careful examination of the orbit, thyroid, kidney and skin in the first 5 years after the diagnosis of UM.

Footnotes

ASA and AS contributed equally.

OS and MR contributed equally.

Presented at: Part of the data was presented in the European Society of Medical Oncology Conference, Barcelona, September 2019.

Contributors: All authors participated in designing the concept of the paper. All authors have contributed to data interpretation and writing the paper. All authors have revised and agreed to the content of the paper. ASA and AS have conducted data mining and analysis and had full access to the dataset. ASA and AS have written the initial manuscript and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. SE, MHA-R, OS and MR shared in the data interpretation and writing the manuscript. OS and MR have supervised the work.

Funding: ASA was supported by grant 57147166 from The German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) between October 2016 and September 2019. The fees for OpenAccess were provided by the library of the University of Leipzig.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. It is mandatory to report cancer under the laws of all 50 states in the USA and informed consent is not required. The public data files are de-identified before release and do not contain any personally identifying information. Analysis of the public data does not require IRB or adherence to any guidelines other than those in the data-use agreement.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The data can be made available by USA NCI SEER Programme on agreement.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1. Kaliki S, Shields CL. Uveal melanoma: relatively rare but deadly cancer. Eye 2017;31:241–57. 10.1038/eye.2016.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Helgadottir H, Höiom V. The genetics of uveal melanoma: current insights. Appl Clin Genet 2016;9:147–55. 10.2147/TACG.S69210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carbone M, Ferris LK, Baumann F, et al. Bap1 cancer syndrome: malignant mesothelioma, uveal and cutaneous melanoma, and MBAITs. J Transl Med 2012;10:179. 10.1186/1479-5876-10-179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. BAP1 Cancer genetics web. Available: http://www.cancerindex.org/geneweb/BAP1.htm

- 5. Laíns I, Bartosch C, Mondim V, et al. Second primary neoplasms in patients with uveal melanoma: a seer database analysis. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;165:54–64. 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rose AM, Cowen S, Jayasena CN, et al. Presentation, treatment, and prognosis of secondary melanoma within the orbit. Front Oncol 2017;7:125. 10.3389/fonc.2017.00125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bergman L, Nilsson B, Ragnarsson-Olding B, et al. Uveal melanoma: a study on incidence of additional cancers in the Swedish population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:72. 10.1167/iovs.05-0884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swerdlow AJ, Storm HH, Sasieni PD. Risks of second primary malignancy in patients with cutaneous and ocular melanoma in Denmark, 1943-1989. Int J Cancer 1995;61:773–9. 10.1002/ijc.2910610606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moan J, Cicarma E, Setlow R, et al. Time trends and latitude dependence of uveal and cutaneous malignant melanoma induced by solar radiation. Dermatoendocrinol 2010;2:3–8. 10.4161/derm.2.1.11745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guénel P, Laforest L, Cyr D, et al. Occupational risk factors, ultraviolet radiation, and ocular melanoma: a case-control study in France. Cancer Causes Control 2001;12:451–9. 10.1023/A:1011271420974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Uveal melanoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6:25. 10.1038/s41572-020-0170-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abdel-Rahman MH, Sample KM, Pilarski R, et al. Whole exome sequencing identifies candidate genes associated with hereditary predisposition to uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology 2020;127:668–78. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koopmans AE, Verdijk RM, Brouwer RWW, et al. Clinical significance of immunohistochemistry for detection of BAP1 mutations in uveal melanoma. Mod Pathol 2014;27:1321–30. 10.1038/modpathol.2014.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gupta MP, Lane AM, DeAngelis MM, et al. Clinical characteristics of uveal melanoma in patients with germline BAP1 mutations. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015;133:881–7. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rai K, Pilarski R, Boru G, et al. Germline BAP1 alterations in familial uveal melanoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2017;56:168–74. 10.1002/gcc.22424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Strande NT, Riggs ER, Buchanan AH, et al. Evaluating the clinical validity of Gene-Disease associations: an evidence-based framework developed by the clinical genome resource. Am J Hum Genet 2017;100:895–906. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Derrien A-C, Rodrigues M, Eeckhoutte A, et al. Germline MBD4 mutations and predisposition to uveal melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2020. 10.1093/jnci/djaa047. [Epub ahead of print: 01 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Siołek M, Cybulski C, Gąsior-Perczak D, et al. Chek2 mutations and the risk of papillary thyroid cancer. Int J Cancer 2015;137:548–52. 10.1002/ijc.29426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang X, Leslie G, Doroszuk A, et al. Cancer Risks Associated With Germline PALB2 Pathogenic Variants: An International Study of 524 Families. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:674–85. 10.1200/JCO.19.01907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sethuraman A, Brown M, Seagroves TN, et al. Smarce1 regulates metastatic potential of breast cancer cells through the HIF1A/PTK2 pathway. Breast Cancer Res 2016;18:81. 10.1186/s13058-016-0738-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith MJ, O'Sullivan J, Bhaskar SS, et al. Loss-Of-Function mutations in SMARCE1 cause an inherited disorder of multiple spinal meningiomas. Nat Genet 2013;45:295–8. 10.1038/ng.2552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dowty JG, Win AK, Buchanan DD, et al. Cancer risks for MLH1 and MSH2 mutation carriers. Hum Mutat 2013;34:490–7. 10.1002/humu.22262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andersen SD, Liberti SE, Lützen A, et al. Functional characterization of MLH1 missense variants identified in Lynch syndrome patients. Hum Mutat 2012;33:1647–55. 10.1002/humu.22153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scélo G, Boffetta P, Autier P, et al. Associations between ocular melanoma and other primary cancers: an international population-based study. Int J Cancer 2007;120:152–9. 10.1002/ijc.22159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA, a WR. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011;144:646–74. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shields CL, Kaliki S, Furuta M, et al. Clinical spectrum and prognosis of uveal melanoma based on age at presentation in 8,033 cases. Retina 2012;32:1363–72. 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31824d09a8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bergman L, Seregard S, Nilsson B, et al. Uveal melanoma survival in Sweden from 1960 to 1998. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44:3282–7. 10.1167/iovs.03-0081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Park SJ, Oh C-M, Yeon B, et al. Sex disparity in survival of patients with uveal melanoma: better survival rates in women than in men in South Korea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017;58:1909–15. 10.1167/iovs.16-20077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Duggan MA, Anderson WF, Altekruse S, et al. The surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (seer) program and pathology: toward strengthening the critical relationship. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:e94–102. 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

esmoopen-2020-000990supp001.pdf (228.3KB, pdf)